Characterizing the Thermal Effects of Urban Morphology Through Unsupervised Clustering and Explainable AI

Highlights

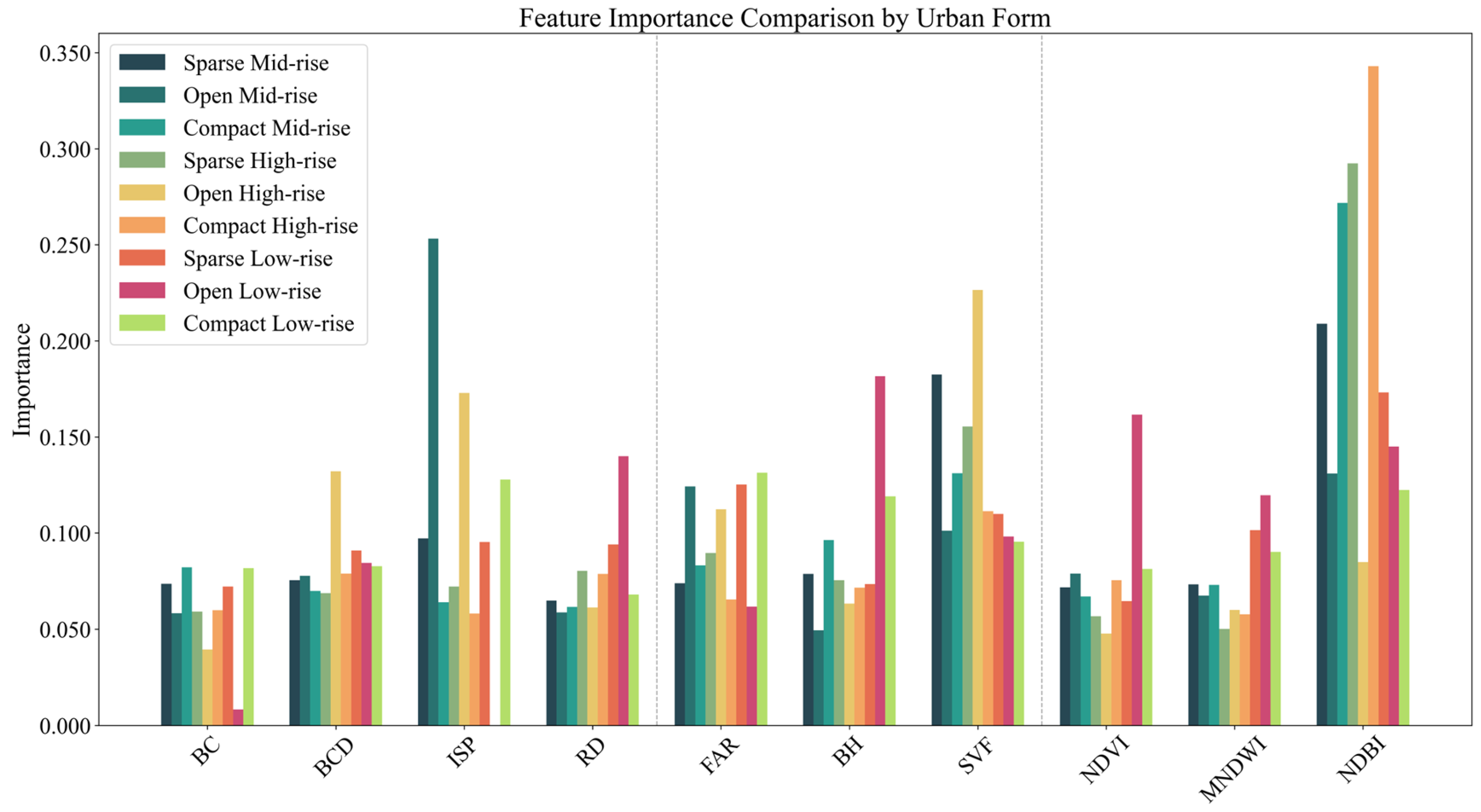

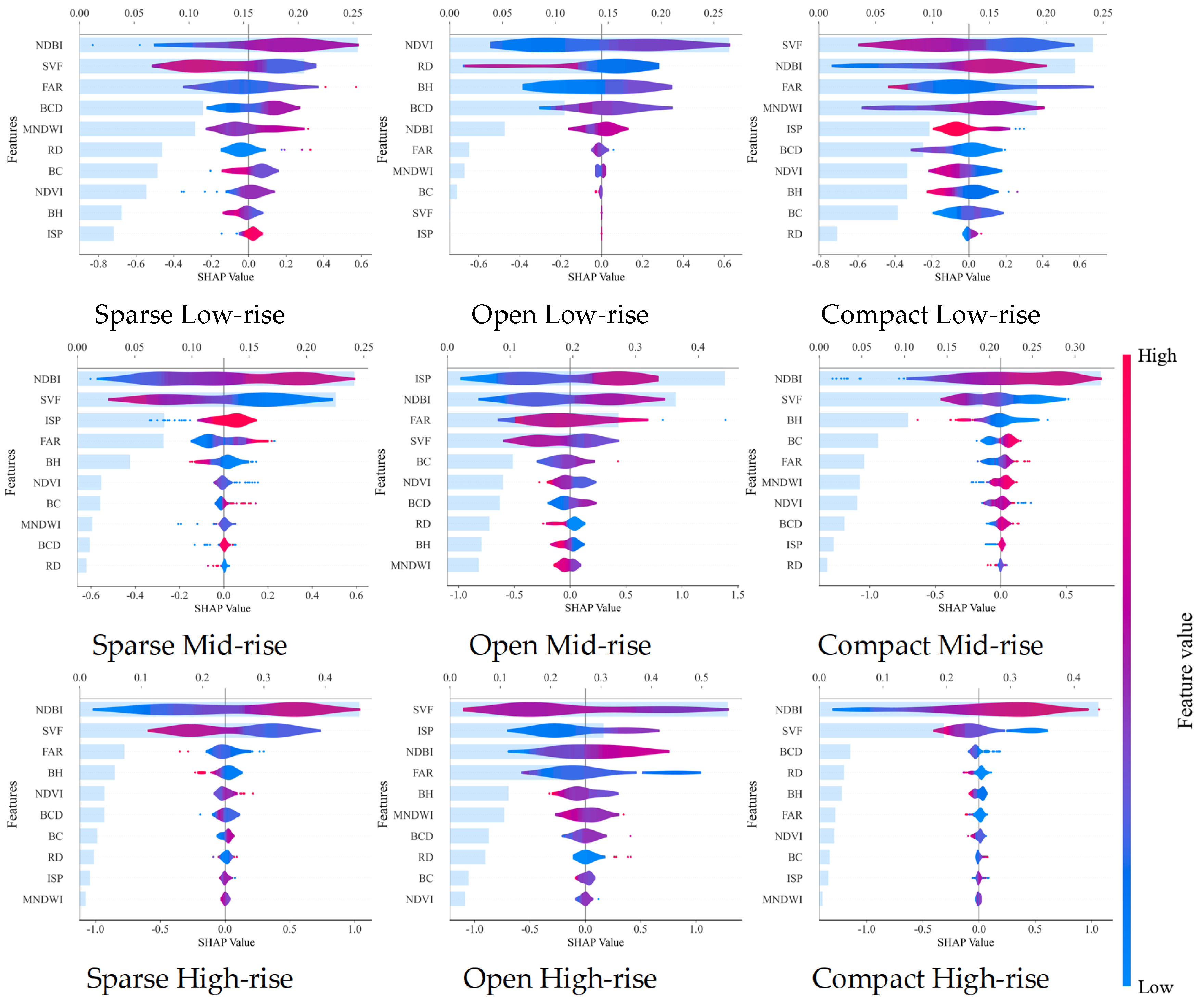

- A data-driven classification using the K-Means unsupervised clustering algorithm reveals that urban morphology is a primary determinant of the thermal environment. Among the classified types, ‘Compact Mid-rise’ exhibits the highest temperatures, whereas ‘Open High-rise’ is the coolest. The Normalized Difference Built-up Index (NDBI) is identified as the most significant warming factor, while the Sky View Factor (SVF) emerges as the most crucial cooling factor. However, the precise influence of these factors is highly contingent upon the specific urban morphology type.

- The influence of three-dimensional (3D) urban morphology on Land Surface Temperature (LST) is both nonlinear and dichotomous. For instance, within compact built-up areas, increasing Building Height (BH) and density presents a double-edged effect. On one hand, it can impede heat dissipation, leading to higher temperatures through a ‘heat trapping’ effect. On the other hand, it can provide a cooling benefit by blocking solar radiation via a ‘shading’ effect.

- These findings advocate for a shift in urban cooling strategies, moving away from a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach towards precisely targeted policies tailored to different local urban morphologies. For instance, urban planning should prioritize the optimization of spatial building layouts in compact zones, whereas in open, low-density areas, the strategic deployment of green infrastructure should be the primary focus.

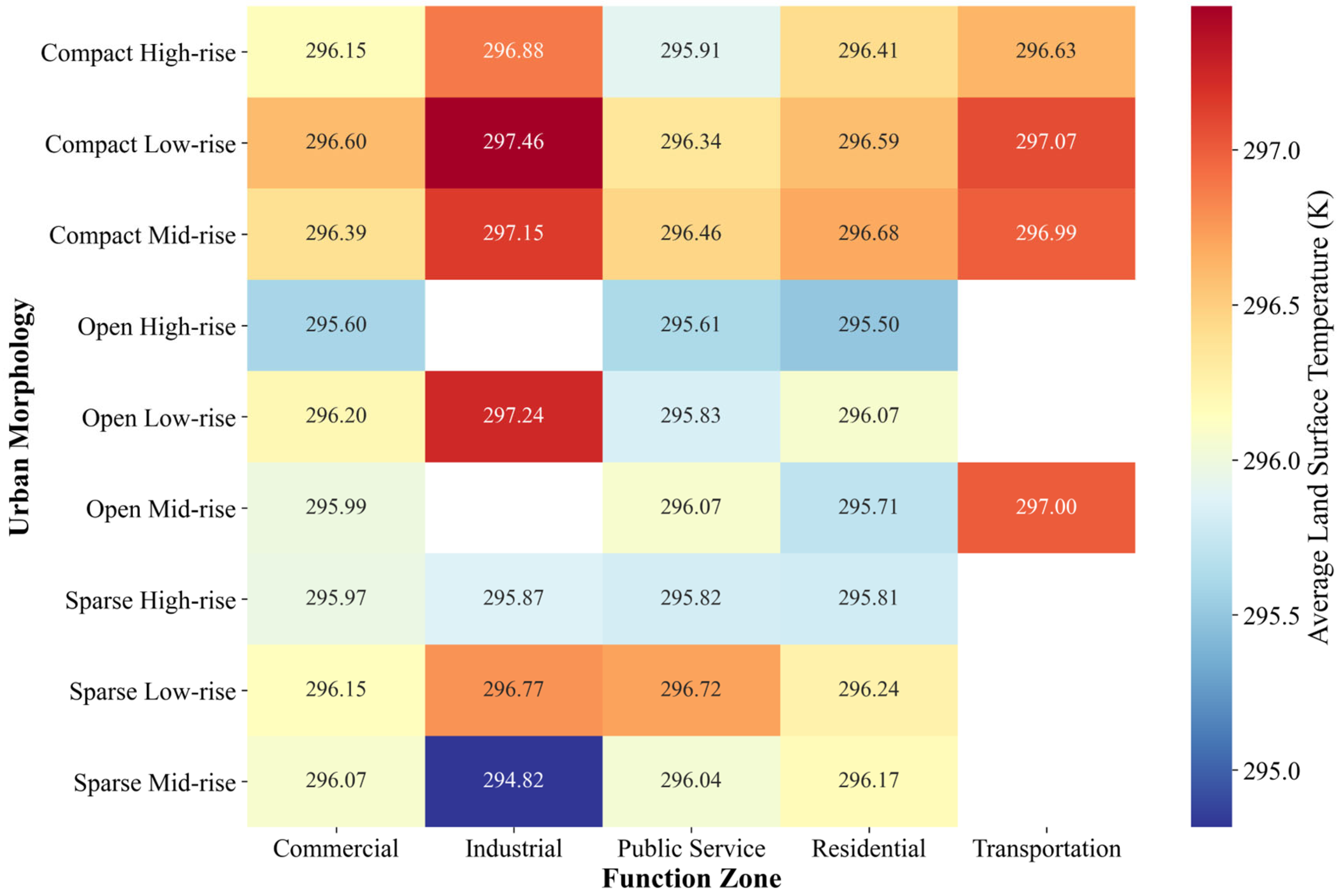

- Urban morphology significantly mediates the thermal effects of different land use functional zones. For functional zones with high anthropogenic heat emissions, such as industrial districts, planning interventions should favor sparse or open layouts to mitigate thermal stress on adjacent areas.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Study Area

3.2. Data Sources and Pre-Processing

3.3. Methodological Framework

- (1)

- Constructing a Data-Driven Classification System for Urban Blocks. This initial step involves delineating irregular urban blocks based on authentic road networks. Subsequently, a K-Means clustering algorithm is applied to classify these blocks into distinct urban structure types based on their internal BCD and average BH. This process establishes a classification system that reflects varying levels of building utilization intensity.

- (2)

- Calculating Multi-dimensional Drivers and Retrieving LST. A suite of 10 driving factors is computed from multi-source data, encompassing metrics of 2D planar patterns, 3D spatial structure, and land cover composition. Concurrently, block-scale LST is retrieved from Landsat 8 imagery using established radiometric correction and mono-window algorithms.

- (3)

- Statistical Modeling and Interpretability Analysis. A preliminary exploratory analysis is first conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation. Following this, nine distinct XGBoost regression models are constructed and trained, one for each urban structure type, to model the LST. Finally, the SHAP method is employed for an in-depth interpretation of the trained models. This allows for the quantitative dissection of the non-linear influence and context-dependent importance of each driver on LST.

3.4. Key Methodological Steps

3.4.1. LST Retrieval and Validation

3.4.2. Classification of Urban Morphology Types

3.4.3. Selection of Driving Factors

3.4.4. Statistical Analysis and Explainable Modeling

- (1)

- A preliminary exploratory analysis was conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient to probe the monotonic relationships between each driving factor and LST. This non-parametric method was chosen for its robustness, as it does not require the data to conform to a normal distribution [67].

- (2)

- To capture the complex non-linear relationships and interaction effects among the driving factors, this study employed XGBoost algorithm [68]. XGBoost is an ensemble learning framework based on decision trees, renowned for its high prediction accuracy and strong robustness against overfitting. The algorithm builds the model sequentially by iteratively adding new decision trees to correct the prediction errors from the previous iteration. As an optimized gradient boosting tree model, XGBoost excels at handling complex non-linear relationships and has been proven to outperform other tree-based machine learning models, such as Random Forest and Support Vector Machines, in terms of both prediction accuracy and computational efficiency [69]. It finds wide application in urban studies, for tasks such as urban heat island effect analysis [70], electricity consumption forecasting [71], and carbon emission research [72]. For each of the nine distinct urban block types, we trained an independent XGBoost regression model with LST as the dependent variable and the 10 driving factors as independent variables. This tailored approach allows us to reveal the differential and context-dependent nature of the driving mechanisms across various urban environmental settings.

- (3)

- Although the XGBoost model possesses powerful predictive capabilities, it is often considered a “black box,” making it difficult to interpret the logic behind its predictions [74]. To address this issue, the SHAP method was introduced to provide post hoc model explanation [75]. SHAP is a game theory-based approach that quantifies the impact of each feature by calculating its marginal contribution to the prediction for each individual sample. Unlike traditional metrics that only provide a global ranking of feature importance, SHAP values can precisely reflect both the magnitude and direction of each feature’s influence [76]. In recent years, the SHAP method has been widely applied in the environmental sciences to reveal the complex internal mechanisms of machine learning models [77,78], thereby helping us to understand the driving factors of the urban thermal environment and their modes of action in a more in-depth and transparent manner.

4. Results

4.1. Spatial Patterns of the Urban Thermal Environment and Morphology Types

4.2. Analysis of LST Driving Mechanisms

4.2.1. Correlation Between Driving Factors and LST

4.2.2. Non-Linearity and Context-Dependency of LST Driving Mechanisms

4.2.3. SHAP-Based Feature Importance Analysis Using the XGBoost Model

4.2.4. Impact of Urban Functional Zones on the Thermal Environment

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparative Analysis with LCZ Classification

5.2. Duality and Non-Linearity of Urban Morphology’s Impact on LST

5.3. Interaction Between Urban Morphology and Functional Zones

5.4. Implications for Urban Planning and Management

5.5. Limitations of the Study

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- A significant quantitative relationship between the urban thermal environment and the urban morphology classification was identified. Compact Mid-rise blocks exhibited the highest annual mean LST at 296.59 K, with a substantial difference of 11.29 K observed between the hottest and coolest block types. The XGBoost model demonstrated robust fitting performance across all nine morphology types, with R2 ranging from 0.62 to 0.93. Through SHAP analysis, the research revealed the significant context-dependency of driver importance. NDBI was the most critical warming factor across all block types. SVF played a key cooling role in high-rise areas by facilitating radiative cooling, whereas NDVI was the dominant cooling factor only in Open Low-rise blocks. This discovery challenges the conventional notion of vegetation’s universally dominant role in urban thermal mitigation, indicating that the influence of driving factors is strongly modulated by block-scale morphological features.

- (2)

- The research identifies a dual mechanism through which urban morphology impacts LST: the coexistence of a “trapping” warming effect and a “shading” cooling effect. In high-density areas, an increase in BH and density reduces SVF, which traps longwave radiation and results in a warming effect. Simultaneously, however, the enhanced shading from taller and denser buildings can provide a significant cooling benefit by blocking direct solar radiation. This discovery transcends the conventional understanding of a simple linear relationship between building density and LST, offering a novel theoretical perspective on the complexity of the urban thermal environment.

- (3)

- The influence of functional zoning on LST exhibits a pronounced morphological modulation effect. Within Compact-type blocks, the high-temperature effects of industrial and transportation zones—often linked to anthropogenic heat emissions —are significantly amplified, with LST differences between functional areas reaching up to 2 K. In contrast, within Open-type blocks, temperatures across different functional zones tend to homogenize, with differentials narrowing to less than 0.4 K. This indicates that under certain conditions, the thermal environment-shaping role of urban morphology itself can override the influence of land use function.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Bai, X.; Dawson, R.J.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D.; Delgado, G.C.; Salisu Barau, A.; Dhakal, S.; Dodman, D.; Leonardsen, L.; Masson-Delmotte, V.; Roberts, D.C.; et al. Six Research Priorities for Cities and Climate Change. Nature 2018, 555, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, P.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y.; Liu, S. Urbanization-Induced Earth’s Surface Energy Alteration and Warming: A Global Spatiotemporal Analysis. Remote Sens. Environ. 2023, 284, 113361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Cao, Q.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Wang, S.; Wang, S.; Wang, L. Characterizing Urban Densification and Quantifying Its Effects on Urban Thermal Environments and Human Thermal Comfort. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2023, 237, 104803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Schlink, U.; Wu, W.; Hu, D.; Sun, J. A New Framework Quantifying the Effect of Morphological Features on Urban Temperatures. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 99, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C.; Li, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Biljecki, F.; Herthogs, P. Bi-Directional Mapping of Morphology Metrics and 3D City Blocks for Enhanced Characterisation and Generation of Urban Form. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 129, 106441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Du, X.; Wang, S. Impact Mechanisms of 2D and 3D Spatial Morphologies on Urban Thermal Environment in High-Density Urban Blocks: A Case Study of Beijing’s Core Area. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 123, 106285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Luo, Y. Assessing Heat Inequalities through the Integration of Building Morphologies and Socioeconomic Conditions. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 387, 125967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kikon, N.; Verma, P. Impact of Land Use Change and Urbanization on Urban Heat Island in Lucknow City, Central India. A Remote Sensing Based Estimate. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Yu, W.; Shi, J.; Huang, Y.; Li, D.; He, X.; Zhou, W.; Xie, Z. Characteristics of Surface Urban Heat Islands in Global Cities of Different Scales: Trends and Drivers. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 107, 105483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-L.; Zhao, H.-M.; Li, P.-X.; Yin, Z.-Y. Remote Sensing Image-Based Analysis of the Relationship between Urban Heat Island and Land Use/Cover Changes. Remote Sens. Environ. 2006, 104, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Weng, Q.; Ouyang, Z.; Li, W.; Schienke, E.W.; Zhang, Z. Land Surface Temperature Variation and Major Factors in Beijing, China. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2008, 74, 451–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Liu, W.; Tan, Z.; Hu, S.; Ao, Z.; Li, J.; Xing, H. Exploring the Seasonal Effects of Urban Morphology on Land Surface Temperature in Urban Functional Zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Wu, G.; Ge, S.; Feng, F.; Li, P. Identification of Key Drivers of Land Surface Temperature within the Local Climate Zone Framework. Land 2025, 14, 771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buyantuyev, A.; Wu, J. Urban Heat Islands and Landscape Heterogeneity: Linking Spatiotemporal Variations in Surface Temperatures to Land-Cover and Socioeconomic Patterns. Landsc. Ecol. 2010, 25, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogashawara, I.; Bastos, V. A Quantitative Approach for Analyzing the Relationship between Urban Heat Islands and Land Cover. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 3596–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, R.; Weng, Q.; Alimohammadi, A.; Alavipanah, S.K. Spatial–Temporal Dynamics of Land Surface Temperature in Relation to Fractional Vegetation Cover and Land Use/Cover in the Tabriz Urban Area, Iran. Remote Sens. Environ. 2009, 113, 2606–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ren, J.; Sun, D.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.; Jin, C.; Li, X. Understanding Land Surface Temperature Impact Factors Based on Local Climate Zones. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 69, 102818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.X.; Pla, F.; Latorre-Carmona, P.; Myint, S.W.; Caetano, M.; Kieu, H.V. Characterizing the Relationship between Land Use Land Cover Change and Land Surface Temperature. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2017, 124, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wu, Y.; Guo, L.; Fan, D.; Sun, W. How Does the 2D/3D Urban Morphology Affect the Urban Heat Island across Urban Functional Zones? A Case Study of Beijing, China. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Luan, W.; Yang, J.; Guo, A.; Su, M.; Tian, C. The Influences of 2D/3D Urban Morphology on Land Surface Temperature at the Block Scale in Chinese Megacities. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ren, C.; Ma, P.; Ho, J.; Wang, W.; Lau, K.K.-L.; Lin, H.; Ng, E. Urban Morphology Detection and Computation for Urban Climate Research. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2017, 167, 212–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.; Luan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, R. The Effects of 2D and 3D Building Morphology on Urban Environments: A Multi-Scale Analysis in the Beijing Metropolitan Region. Build. Environ. 2021, 192, 107635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Dai, Z.; Guldmann, J.-M. Modeling the Impact of 2D/3D Urban Indicators on the Urban Heat Island over Different Seasons: A Boosted Regression Tree Approach. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 266, 110424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R. Local Climate Zones for Urban Temperature Studies. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2012, 93, 1879–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, I.D.; Oke, T.R.; Krayenhoff, E.S. Evaluation of the ‘Local Climate Zone’ Scheme Using Temperature Observations and Model Simulations. Int. J. Climatol. 2014, 34, 1062–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yuan, B.; Hu, F.; Wei, C.; Dang, X.; Sun, D. Understanding the Effects of 2D/3D Urban Morphology on Land Surface Temperature Based on Local Climate Zones. Build. Environ. 2022, 208, 108578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, R.; Ouyang, W.; Tan, Z. A Multi-Scale Mapping Approach of Local Climate Zones: A Case Study in Hong Kong. Urban Clim. 2025, 61, 102446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Yang, Y.; Pan, X.; Zhu, Q.; Zhan, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W.; Su, W. Analysis of the Spatial and Temporal Variations of Land Surface Temperature Based on Local Climate Zones: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 4213–4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Bai, J.; Zhao, J.; Guo, F.; Zhu, P.; Dong, J.; Cai, J. Application and Future of Local Climate Zone System in Urban Climate Assessment and Planning—Bibliometrics and Meta-Analysis. Cities 2024, 150, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W.; Liu, J. A Literature Survey of Local Climate Zone Classification: Status, Application, and Prospect. Buildings 2022, 12, 1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechtel, B.; Alexander, P.J.; Beck, C.; Böhner, J.; Brousse, O.; Ching, J.; Demuzere, M.; Fonte, C.; Gál, T.; Hidalgo, J.; et al. Generating WUDAPT Level 0 Data–Current Status of Production and Evaluation. Urban Clim. 2019, 27, 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, F.; Xie, C.; Vogel, J.; Afshari, A. Inference of Local Climate Zones from GIS Data, and Comparison to WUDAPT Classification and Custom-Fit Clusters. Land 2022, 11, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rogora, A. Local Climate Zone in Xi’an City: A Novel Classification Approach Employing Spatial Indicators and Supervised Classification. Buildings 2023, 13, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Song, H.; Shreevastava, A.; Albrecht, C.M. AutoLCZ: Towards Automatized Local Climate Zone Mapping from Rule-Based Remote Sensing. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2024-2024 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Athens, Greece, 7 July 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2023–2027. [Google Scholar]

- Biljecki, F.; Chow, Y.S.; Lee, K. Quality of Crowdsourced Geospatial Building Information: A Global Assessment of OpenStreetMap Attributes. Build. Environ. 2023, 237, 110295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Long, Y. CMAB-The World’s First National-Scale Multi-Attribute Building Dataset; 16973214343 Bytes; Figshare: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, P.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, B.; Hu, T.; Liu, X.; Xu, B.; Yang, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Annual Maps of Global Artificial Impervious Area (GAIA) between 1985 and 2018. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 236, 111510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, P.; Chen, B.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, J.; Bai, Y.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Fang, L.; Feng, S.; et al. Mapping Essential Urban Land Use Categories in China (EULUC-China): Preliminary Results for 2018. Sci. Bull. 2020, 65, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.S.; Singh, N.; Thapa, S.; Sharma, D.; Kumar, D. Retrieval of Land Surface Temperature (LST) from Landsat TM6 and TIRS Data by Single Channel Radiative Transfer Algorithm Using Satellite and Ground-Based Inputs. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2017, 58, 264–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Muñoz, J.C.; Sobrino, J.A. A Generalized Single-channel Method for Retrieving Land Surface Temperature from Remote Sensing Data. J. Geophys. Res. 2003, 108, 2003JD003480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhengming, W.; Dozier, J. A Generalized Split-Window Algorithm for Retrieving Land-Surface Temperature from Space. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1996, 34, 892–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, A.J. Land Surface Temperatures Derived from the Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer and the Along-track Scanning Radiometer: 1. Theory. J. Geophys. Res. 1993, 98, 16689–16702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsi, J.; Schott, J.; Hook, S.; Raqueno, N.; Markham, B.; Radocinski, R. Landsat-8 Thermal Infrared Sensor (TIRS) Vicarious Radiometric Calibration. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 11607–11626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.H.; Zhang, M.H.; Karnieli, A.; Berliner, P. Mono-Window Algorithm for Retrieving Land Surface Temperature from Landsat TM6 Data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2001, 56, 456–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Qin, Z.; Song, C.; Tu, L.; Karnieli, A.; Zhao, S. An Improved Mono-Window Algorithm for Land Surface Temperature Retrieval from Landsat 8 Thermal Infrared Sensor Data. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 4268–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Zhu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Shen, Y.; Shen, X.; Xu, Z. Investigating the Effects of Urban Morphological Factors on Seasonal Land Surface Temperature in a “Furnace City” from a Block Perspective. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 86, 104165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiullari, D.; Pijpers-van Esch, M.; Timmeren, A.V. A Quantitative Morphological Method for Mapping Local Climate Types. Urban Plan. 2021, 6, 240–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, M.Y.; Rodler, A.; Musy, M.; Guernouti, S.; Cools, M.; Teller, J. Identifying Urban Morphological Archetypes for Microclimate Studies Using a Clustering Approach. Build. Environ. 2022, 224, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sützl, B.S.; Strebel, D.A.; Rubin, A.; Wen, J.; Carmeliet, J. Urban Morphology Clustering Analysis to Identify Heat-Prone Neighbourhoods in Cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 107, 105360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Shi, S.; Liu, B. Quantifying the Nonlinear Effects of Urban-Rural Blue-Green Landscape Combination Patterns on the Trade-off between Carbon Sinks and Surface Temperature: An Approach Based on Self-Organizing Mapping and Interpretable Machine Learning. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Sun, J.; Hu, D. Surface Energy Balance-Based Surface Urban Heat Island Decomposition at High Resolution. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 315, 114447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, L.; Pai, L.; Hou, J. Three-Dimensional Urban Form at the Street Block Level for Major Cities in China. Shanghai Urban Plan. Rev. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Huang, K.; Hou, B.; Prishchepov, A.V. Effects of Building Density on Land Surface Temperature in China: Spatial Patterns and Determinants. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, B.; Zhu, W.; Jia, S.; Lv, A. Spatio-Temporal Changes in Vegetation Activity and Its Driving Factors during the Growing Season in China from 1982 to 2011. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13729–13752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Shen, Y.; Fu, W.; Zheng, D.; Huang, P.; Li, J.; Lan, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Q.; Xu, X.; et al. How Does 2D and 3D of Urban Morphology Affect the Seasonal Land Surface Temperature in Island City? A Block-Scale Perspective. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Song, L.; Xu, S. Community-Level Urban Vitality Intensity and Diversity Analysis Supported by Multisource Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Zhang, R.; Wu, J.; Zhou, W.; Liang, Z. Heterogeneous Dominant Factors of Heat Resilience across Diverse Urban Patterns. Land Use Policy 2025, 157, 107676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhdari, A.; Soltani, A.; Alidadi, M. Urban Morphology and Landscape Structure Effect on Land Surface Temperature: Evidence from Shiraz, a Semi-Arid City. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-J.; Kim, D.-Y. Effects of a Building’s Density on Flow in Urban Areas. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 2009, 26, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Su, J.; Xia, J.; Jin, C.; Li, X.; Ge, Q. The Impact of Spatial Form of Urban Architecture on the Urban Thermal Environment: A Case Study of the Zhongshan District, Dalian, China. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 2709–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghauser Pont, M.; Haupt, P. Spacematrix: Space, Density and Urban Form Revised; Chalmers University of Technology: Gothenburg, Sweden; Delft University of Technology: Delft, The Netherlands; TU Delft OPEN Publishing: Delft, The Netherlands, 2023; ISBN 978-94-6208-539-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pont, M.B.; van der Hoeven, F.; Rosemann, J. Urbanism Laboratory for Cities and Regions: Progress of Research Issues in Urbanism 2007; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-1-58603-799-4. [Google Scholar]

- Scarano, M.; Mancini, F. Assessing the Relationship between Sky View Factor and Land Surface Temperature to the Spatial Resolution. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 6910–6929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Song, C.; Cao, L.; Zhu, F.; Meng, X.; Wu, J. Impacts of Landscape Structure on Surface Urban Heat Islands: A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Remote Sens. Environ. 2011, 115, 3249–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yang, J.; Sun, W.; Xiao, X.; Xia Cecilia, J.; Jin, C.; Li, X. Impact of Urban Morphology and Landscape Characteristics on Spatiotemporal Heterogeneity of Land Surface Temperature. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 63, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Huang, X.; Li, J. Assessing the Relationship between Surface Urban Heat Islands and Landscape Patterns across Climatic Zones in China. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanoori, G.; Soltani, A.; Modiri, A. Machine Learning for Urban Heat Island (UHI) Analysis: Predicting Land Surface Temperature (LST) in Urban Environments. Urban Clim. 2024, 55, 101962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Ren, Y.; Xu, C.; Jia, B.; Wu, S.; Lafortezza, R. Exploring the Non-Linear Impacts of Urban Features on Land Surface Temperature Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Urban Clim. 2024, 56, 102045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, A.; Yue, W.; Yang, J.; He, T.; Zhang, M.; Li, M. Divergent Impact of Urban 2D/3D Morphology on Thermal Environment along Urban Gradients. Urban Clim. 2022, 45, 101278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Shi, Y.; Xu, L.; Lu, Z.; Feng, M. An Investigation on the Impact of Blue and Green Spatial Pattern Alterations on the Urban Thermal Environment: A Case Study of Shanghai. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, X.; Liu, Z.; Meng, X.; Yang, X. Multi-Scale Electricity Consumption Prediction Model Based on Land Use and Interpretable Machine Learning: A Case Study of China. Adv. Appl. Energy 2024, 16, 100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H.; Wang, C.; Li, C.; Meng, X.; Yang, X.; Tan, Q. Multi-Scale Carbon Emission Characterization and Prediction Based on Land Use and Interpretable Machine Learning Model: A Case Study of the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Appl. Energy 2024, 360, 122819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Niu, J.; Zhang, C.; Chen, L.; Su, B.; Zhou, S. Interpretable Machine Learning Reveals Transport of Aged Microplastics in Porous Media: Multiple Factors Co-Effect. Water Res. 2025, 274, 123129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Ning, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhao, X.; Huang, X. How Do Driving Factors Affect the Diurnal Variation of Land Surface Temperature across Different Urban Functional Blocks? A Case Study of Xi’an, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 114, 105738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, NT, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Shi, L.; Shi, Y.; Tang, J.; Zhao, P.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J. Exploring Interactive and Nonlinear Effects of Key Factors on Intercity Travel Mode Choice Using XGBoost. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 166, 103264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Chen, C.; Gao, S.; Zhang, X.; Majok Chol, D.; Yang, Z.; Meng, L. Understanding of the Predictability and Uncertainty in Population Distributions Empowered by Visual Analytics. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2024, 39, 675–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Song, Y. Unraveling Nonlinear and Spatial Non-Stationary Effects of Urban Form on Surface Urban Heat Islands Using Explainable Spatial Machine Learning. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2024, 114, 102200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Xiao, X.; Wang, H. Temporal and Spatial Variations of Urban Surface Temperature and Correlation Study of Influencing Factors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, J.; Yin, C.; An, Z.; Mu, B.; Wen, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Song, Y. The Influence of Urban Form on Land Surface Temperature: A Comprehensive Investigation from 2D Urban Land Use and 3D Buildings. Land 2023, 12, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokaie, M.; Zarkesh, M.K.; Arasteh, P.D.; Hosseini, A. Assessment of Urban Heat Island Based on the Relationship between Land Surface Temperature and Land Use/Land Cover in Tehran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2016, 23, 94–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, B.; Wang, B.; Wei, W. Multifactorial Influences on Land Surface Temperature within Local Climate Zones of Typical Global Cities. Urban Clim. 2024, 57, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Wu, H.; Luo, W.; Fan, K.; Liu, H. How Does Urban Heat Island Differ across Urban Functional Zones? Insights from 2D/3D Urban Morphology Using Geospatial Big Data. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Du, S.; Myint, S.W.; Shu, M. Do Urban Functional Zones Affect Land Surface Temperature Differently? A Case Study of Beijing, China. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Category | Data Source | Spatial Resolution | Description and Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Road Network Data | OpenStreetMap (OSM) [35] | Vector | Calculation of RD and delineation of irregular urban blocks |

| Building Vector Data | The World’s First National-Scale Multi-Attribute Building Dataset (CMAB) [36] | Vector | Calculation of morphology indicators, including BC, BCD, BH, and FAR |

| Remote Sensing Imagery | United States Geological Survey (USGS) | 30 m | Retrieval of LST and calculation of land cover indices, namely NDVI, NDBI, and MNDWI |

| Impervious Surface Data | Global Artificial Impervious Area (GALA) Dataset [37] | 30 m | Calculation of ISP |

| Urban Functional Zones | Essential Urban Land Use Categories of China (EULUC-China) [38] | 30 m | Used for the classification of urban functional zones. |

| Dimension | Factor | Abbreviation | Formula | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Morphology | Building Count [58] | BC | Total number of buildings within a block. | |

| Building Coverage Ratio [59] | BCD | The ratio of the total building footprint area to the total block area. | ||

| Impervious Surface Percentage [23] | ISP | The ratio of impervious surface area to the total area of a given region. | ||

| Road Density [60] | RD | The ratio of the total road network area to the total block area. | ||

| 3D Morphology | Floor Area Ratio [61] | FAR | The ratio of the total floor area of all buildings to the total block area. | |

| Building Height [62] | BH | The average building height within a block. | ||

| Sky View Factor [63] | SVF | The ratio of the radiation received from the sky to the total radiation emitted by the entire hemispheric environment. | ||

| Land Cover | Normalized Difference Vegetation Index [64] | NDVI | Quantifies vegetation by measuring the difference between near-infrared and red light. | |

| Modified Normalized Difference Water Index [65] | MNDWI | Enhances the detection of open water features while suppressing noise from built-up land and vegetation. | ||

| Normalized Difference Built-up Index [66] | NDBI | Used to extract and map built-up areas. |

| Functional Zone | Transportation | Industrial | Residential | Commercial | Public Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 21 | 99 | 1938 | 461 | 1355 |

| Average Temperature (K) | 296.93 | 296.60 | 296.14 | 296.13 | 296.09 |

| K-Means Classification (This Study) | Block Proportion (%) | Corresponding LCZ Category | LCZ Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compact High-rise | 20.83% | LCZ 1 (Compact high-rise) | 8.30% |

| Compact Mid-rise | 31.26% | LCZ 2 (Compact mid-rise) | 34.37% |

| Compact Low-rise | 7.48% | LCZ 3 (Compact low-rise) | 18.68% |

| Sparse/Open High-rise | 11.35% | LCZ 4 (Open high-rise) | 5.52% |

| Sparse/Open Mid-rise | 23.35% | LCZ 5 (Open mid-rise) | 2.68% |

| Sparse/Open Low-rise | 5.71% | LCZ 6, 8, 9 (Sparse/open low-rise types) | 16.11% |

| LCZ 7 (Lightweight low-rise) | 6.72% | ||

| LCZ A-G (Natural land cover types) | 7.62% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, F.; Shen, Y.; Zheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Zuo, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M. Characterizing the Thermal Effects of Urban Morphology Through Unsupervised Clustering and Explainable AI. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183211

Xu F, Shen Y, Zheng M, Zhang X, Zuo Y, Wang X, Zhang M. Characterizing the Thermal Effects of Urban Morphology Through Unsupervised Clustering and Explainable AI. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(18):3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183211

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Feng, Ye Shen, Minrui Zheng, Xiaoyuan Zhang, Yuqiang Zuo, Xiaoli Wang, and Mengdi Zhang. 2025. "Characterizing the Thermal Effects of Urban Morphology Through Unsupervised Clustering and Explainable AI" Remote Sensing 17, no. 18: 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183211

APA StyleXu, F., Shen, Y., Zheng, M., Zhang, X., Zuo, Y., Wang, X., & Zhang, M. (2025). Characterizing the Thermal Effects of Urban Morphology Through Unsupervised Clustering and Explainable AI. Remote Sensing, 17(18), 3211. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17183211