Abstract

Crop condition mapping and yield loss detection are highly relevant scientific fields due to their economic importance. Here, we report a new, robust six-category crop condition mapping methodology based on five vegetation indices (VIs) using Sentinel-2 imagery at a 10 m spatial resolution. We focused on maize, the most drought-affected crop in the Carpathian Basin, using three selected years of data (2017, 2022, and 2023). Our methodology was validated at two different spatial scales against independent reference data. At the parcel level, we used harvester-derived precision yield data from six maize parcels. The agreement between the yield category maps and those predicted from the crop condition time series by our Random Forest model was 84.56%, while the F1 score was 0.74 with a two-category yield map. Using a six-category yield map, the accuracy decreased to 48.57%, while the F1 score was 0.42. The parcel-level analysis corroborates the applicability of the method on large scales. Country-level validation was conducted for the six-category crop condition map against official county-scale census data. The proportion of areas with the best and worst crop condition categories in July explained 64% and 77% of the crop yield variability at the county level, respectively. We found that the inclusion of the year 2022 (associated with a severe drought event) was important, as it represented a strong baseline for the scaling. The study’s novelty is also supported by the inclusion of damage claims from the Hungarian Agricultural Risk Management System (ARMS). The crop condition map was compared with these claims, with further quantitative analysis confirming the method’s applicability. This method offers a cost-effective solution for assessing damage claims and can provide early yield loss estimates using only remote sensing data.

1. Introduction

Maize (Zea mays L.) is one of the most important staple crops worldwide. It plays a fundamental role in the production of food, animal feed, and biofuels, and its economic significance is well recognised [1]. Maize is known to be sensitive to weather conditions during the growing season. Among others, heat stress, soil water content deficit, and atmospheric drought can affect its growth in various ways depending on the growth stage [2,3,4,5,6]. High temperatures during anthesis can affect the final yield because of its negative impact on pollination.

Maize yield loss is common in the drought-prone Central European region [7]. In Hungary, where more than 60% of the land is cultivated and most of the agricultural fields are rainfed, the risk is particularly high and the economic consequences can be severe [8]. The exceptional summer drought of 2022 was, by far, the most damaging that has occurred in Hungary so far and highlighted the need for a comprehensive, robust, and high-resolution crop monitoring and early warning system. However, the quantification of yield loss is complicated because of the general lack of spatially explicit and accurate reference data.

Remote sensing provides a spatially explicit, observation-based tool for vegetation characterisation including maize condition mapping [9]. However, remote sensing is sensitive to green biomass and not the grain mass itself; hence, yield estimation is indirect and can be challenging, especially if heat stress affects anthesis and the yield is decoupled from the green biomass [3,4]. Several studies showed that remote sensing can still provide valuable timely estimates for the final yield, approximately two months prior to the harvest [10,11,12,13].

Most studies dealing with the quantification of crop conditions utilise a single remote sensing index [14,15,16,17,18]. Because of technological advancements and progress in relevant research, a large number of vegetation indices are available nowadays, permitting the testing and exploitation of ensemble techniques based thereon. At present, the applicability of ensemble methods for crop condition mapping is not well discovered, and requires additional research. A further complication is that data provided by medium-resolution sensors with frequent revisit times are not sufficient to map inhomogeneities within the parcel because of the generally small parcel sizes. From this point of view, Sentinel-2 offers a convenient solution among the freely available satellite imagery.

Validation of the remote sensing-based maize condition mapping is typically limited to large areas, e.g., NUTS2- or NUTS3-level (NUTS: Nomenclature of Territorial Units). Alternative datasets with better spatial resolution are highly needed to validate the remote sensing-based yield loss estimations. In Hungary, the yield loss compensation scheme and the underlying system offer a unique possibility for the intercomparison of remote sensing results and compensation claims. This so-called Agricultural Risk Management System (ARMS) became operational in 2012 [19,20]. Its first pillar is constituted by the so-called Agricultural Compensation Scheme, under which farmers can claim compensation for yield losses caused by weather events. Currently, damage claims can be made for the following nine types of damage: drought, inland excess water, floods, winter frost damage, storms, downpours, hail, and autumn and spring frost damage. The drought event that occurred in 2022 hit farmers so hard that during the peak of the summer claiming period, more drought damage claims were received each week than in all previous years during the entire claiming period. That year, approximately EUR 123.3 million was paid out to mitigate the damage [20]. The large number of drought claims has placed a significant burden on organisations assessing damage claims in the field and has increased the need for greater use of remote sensing. On-the-spot control of such a high number of damage claims is impossible with the existing capacities, stressing the need for the development of a validated, robust remote sensing-based system.

The aim of the present study is to describe a complex workflow that is being implemented in Hungary for maize condition mapping to support agricultural damage claim validation. The applicability of the method is first demonstrated at the parcel level using high-resolution, harvester-derived precision yield maps. The damage claim dataset and the census-based yield dataset are used to further validate the approach. The statistical analysis is presented to document the performance of the workflow.

The novelty of this study is the development of a fast, robust, ensemble-based, and generalised methodology adaptable to crop rotation and based on the use of high-resolution remote sensing data to provide accurate estimates of maize biomass and yield predictions over large areas (i.e., county scale). We propose a mapping method and spatialisation that is as independent as possible from in situ measurements of the mapping year, as well as reliable over large areas and under different meteorological conditions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

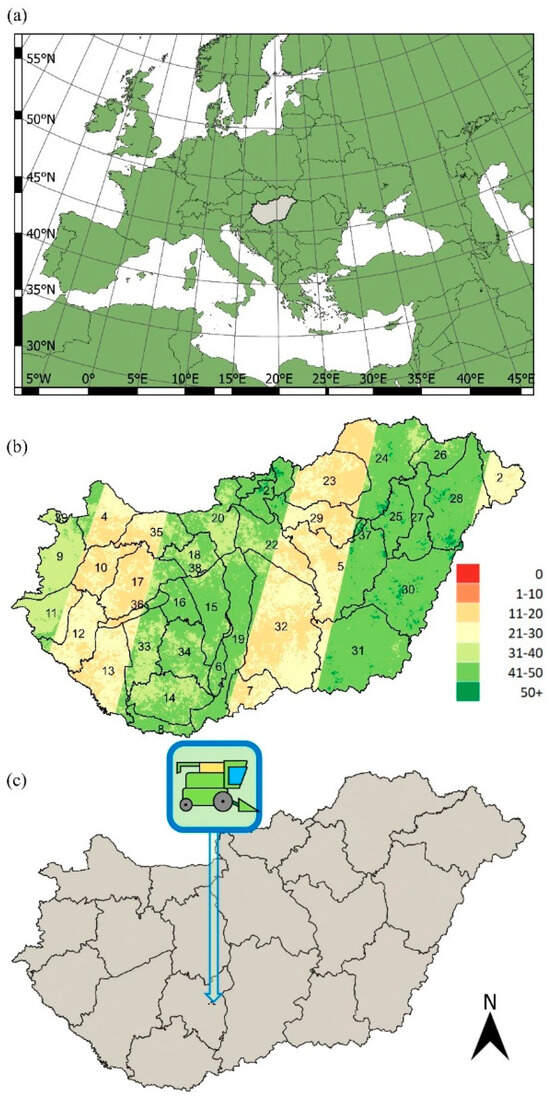

The study focuses on Hungary, located in the Carpathian Basin in Central Europe (Figure 1a). The climate of the country is continental with oceanic and Mediterranean influences. Most of the area is lowland, broken in the north and west of the country by drumlins and highlands. The country’s territory was divided into 34 separate agroecological (AE) zones [21], which can be considered homogeneous internally but differ from each other in terms of soil, meteorology, and topography (Figure 1b). The number of agricultural parcels within each of these zones varies considerably depending on the size and typical cultivation of the zone, ranging from 4500 to 107,000 [22].

Figure 1.

Spatial characteristics of the study area and visual representation of the applied datasets: (a) location of Hungary in Central Europe; (b) number of cloud-free Sentinel-2 observations available between May and October, with the contours of agroecological zones; (c) location of study parcels with harvester-derived precision yield data and county borders within the country.

2.2. Remote Sensing-Based Vegetation Indices

To quantify crop conditions on large scales we used vegetation indices derived from the data of the Sentinel-2A/2B Multispectral Imager (MSI) instrument. The Sentinel-2A and 2B satellites provide surface reflectance measurements with a high spatial resolution of 10 and 20 m. The revisit period of the Sentinel-2 constellation is currently 5 days over about half of the country’s territory. Because of the orbital characteristics, the total spatial coverage is not uniform within the country (see Figure 1b). This typically results in 10 to 50 cloud-free overpasses during the growing season (May–October) [23].

To ensure the robustness of our ensemble methodology, we used five vegetation indices based on Sentinel-2 imagery that are sensitive to vegetation characteristics and, therefore, used as a proxy to describe crop conditions. For calculating the VIs, atmospherically corrected surface reflectance data (ρ; processing level: L2A) were used for bands B2 (blue, with a 10 m resolution), B4 (red, with a 10 m resolution), B6 (red-edge, at 740 nm, with a 20 m resolution), B8 (near-infrared at 842 nm, with a 10 m resolution), and B11 (short-wave infrared at 1610 nm, with a 20 m resolution). Note that we did not quantify the effect of the VI selection, as this was beyond the scope of the present study. Instead, following the logic of the ensemble model’s construction, we used all five indices without further refinement and selection.

The Normalised Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is the most frequently used VI in remote sensing [24,25]. The NDVI is defined as (ρNIR − ρRED)/(ρNIR + ρRED) [26].

Since the NDVI is known to have saturation issues [27,28,29,30], the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) was designed to improve the sensitivity in cases of high biomass and to reduce the canopy background effects, as well as atmospheric influences [31]. The EVI is defined as G × (ρNIR − ρRED)/(ρNIR + C1 × ρRED − C2 × ρBLUE + L), and we used the coefficients with values C1 = 6 and C2 = 7.5 (accounting for the aerosol resistance), L = 1 (canopy background adjustment factor), and G = 2.5 (gain factor) [32].

Another enhanced index, the newly introduced the kNDVI, proposed by Camps-Valls et al. [33], also aims to overcome the issue of NDVI saturation. It was calculated as kNDVI = tanh(((ρNIR − ρRED)/2 × σ)2), using the suggested simplifications in the cited reference. Based on the study by Wang et al. [34], σ was set to 0.2, as proposed, to provide optimal results with respect to canopy photosynthesis for maize.

The Normalised Difference Moisture Index (NDMI) aims to detect vegetation moisture levels using a combination of near-infrared and short-wave infrared spectral bands [35]. The NDMI is defined as (ρNIR − ρSWIR)/(ρNIR + ρSWIR). It is claimed to be a reliable indicator of water stress in crops and is often used to assess the need for irrigation [30,35].

The Plant Senescence Reflectance Index (PSRI) can be used to estimate the onset, stage, relative rates, and kinetics of senescence/ripening processes. It is defined as (ρRED − ρBLUE)/ρREDEDGE [36]. Unlike the other indices, the PSRI has a high value if the plant leaves are senesced to some extent.

All vegetation indices were derived with a spatial resolution of 10 metres, where B6 and B11, required for the PSRI and NDMI, were resampled with nearest neighbour resampling to 10 m from the original 20 m. This decision is also justified by the consistency of the information content of the other bands and the average parcel sizes.

To facilitate analysis and comparison, we normalised and categorised the aforementioned indices separately using the Vegetation Condition Index (VCI) approach [37]. Normalisation was conducted according to the formula (VIi,j − VImin)/(VImax − VImin) × 100, resulting in values expressed in percentage. Although the normalisation of a given VI is usually performed either on a pixel basis or over the entire dataset, we chose a different approach specific to the acquisition time and agroecological zone (see details in Section 2.4). The VCI approach is beneficial for making relative assessments, such as detecting pixel-specific changes in the VI signal, as it reduces the effect of local geographic and environmental factors on the spatial variability of a VI. In the literature, the VCI is, in most cases, calculated from the NDVI; hence, previous findings on the reliability of the approach apply to this index. The NDVI-based VCI allows for more accurate comparisons across various ecological zones and vegetation types, and it serves as a more effective indicator of vegetation stress conditions than the NDVI alone. The VCI is considered more reliable than other indices for monitoring drought in arid and semi-arid regions [38]. According to the proposed approach, a VCI value above 50% reflects relatively good vegetation conditions (under ideal conditions, the VCI approaches 100%). The study of Belal et al. [39] also shows that the VCI values have stronger correlations with precipitation than that of the NDVI, as local factors, such as soil characteristics, previous year’s stress, and land cover, also influence the vegetation state.

2.3. Maize Area Classification

The added value of the study is the application of an advanced method for the spatially explicit, high-resolution mapping of maize parcels in Hungary. For the identification of maize parcels, we used annual country-wide crop maps based on Random Forest classification, provided by the Lechner Knowledge Center. The method [40] uses Sentinel-2 optical bands, vegetation indices, and Sentinel-1 polarimetric descriptors (alpha, second eigenvalue, and Shannon entropy from the H/A/alpha decomposition [41]). The in situ reference data used for the classification were taken from the parcel-level farmers’ claim data indicating crop type, submitted to the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) subsidy system in Hungary. For main crops including maize, the classification accuracy per agroecological zone is typically well over 90% [42]. During statistical validation, parcels with an area under 1 ha were excluded to remove small fields with too many mixed pixels. Categorisation of the crop conditions was conducted for all maize varieties (sweet maize, popcorn, silage maize, and hybrid maize), but only grain maize was included in the study. In general, irrigation is uncommon for grain maize, while other varieties are more likely to be irrigated, so this decision was made to reduce noise. We also aimed to ensure a more uniform growing season during the study by focusing on grain maize only. Moreover, this is the crop with the most claims submitted in Hungary (see Figure S1).

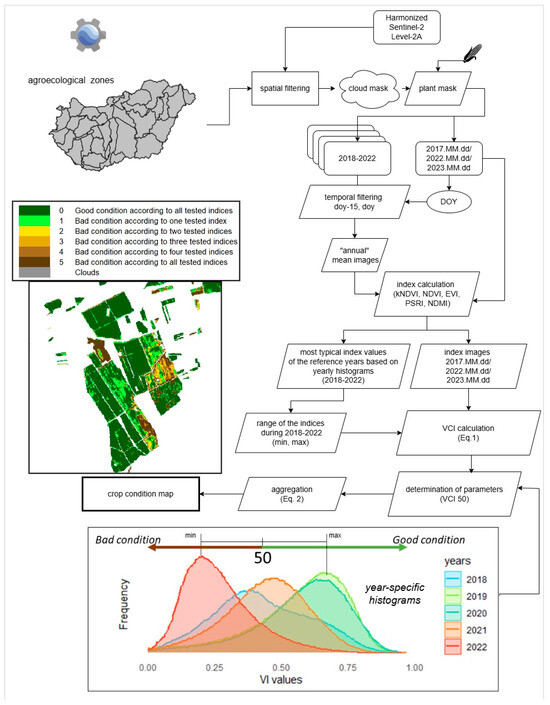

2.4. Crop Condition Mapping Workflow

The crop condition mapping process was implemented in Google Earth Engine [43] and based on Harmonized Sentinel-2 Level-2A images. Mapping was carried out for each individual agroecological zone separately, at 10-metre spatial resolutions (see detailed flowchart and illustrations in Figure 2). The first step was the selection of cloud-free, clear imagery (“master images”) for the period of interest for each agroecological zone using visual interpretation. Wherever needed, cloud masking was conducted on the master images automatically and revised manually as well to avoid miscategorisation. Then, imagery from the reference years (2018–2022) was collected for each AE zone by selecting imagery from the corresponding 15-day period, ending with the same day of the year (DOY) as the master image. Then, images from the past were clipped to the given AE zone, after the automatic cloud masking, as well as applying a maize mask. In the next phase, pixel-based temporal compositing was carried out by calculating mean values from all available masked images per year to represent the past as a reference for the given AE zone and 15-day period.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the crop condition mapping process.

These 15-day mean composite images also served as the basis for calculating the mean image of the five VIs involved in the study (kNDVI, NDVI, EVI, NDMI, and PSRI; see Section 2.2). In the next step, the modes of the zones (i.e., the peaks of the histograms of each VI dataset determined as the most significant value for the given AE zone and 15-day interval during the study period) individually for all reference years. These mode values represent the given zone’s typical VI values for maize for each time period. Next, we determined the minimum (VImin(2018–2022)) and maximum (VImax(2018–2022)) VI mode (histogram peak) values during the reference period (2018–2022) at the AE zone level for each VI and each 15-day period. This approach is different from the “usual” VCI calculation method but is necessary because of crop rotation and differences in climatic and agro-technical conditions. By setting the VImin(2018–2022) and VImax(2018–2022) values based on the modes, the actual scale of the VCI exceeds the range of 0–100%, as we used the most typical values for the given area in order to reduce the noise in parameterisation. The minimum and maximum values represent the relevant range of the VIs for the given period. From these parameters and the five VI images derived from the master image, the percentage values of the master image for a given index were calculated using the VCI approach (Equation (1)), as follows:

where VCIVIi,j is the VCI value of a given VI at pixel (i,j) calculated by the VCI approach, VImin(2018–2022) is the AE zone minimum mode value for the given 15-day period from the reference years of the given VI, and VImax(2018–2022) is the AE zone maximum mode value for the given 15-day period from the reference years of the given VI. Based on the minimum and maximum VCI values, VCI50 is defined as the arithmetic mean of VImin(2018–2022) and VImax(2018–2022). The individual VI-based VCI values were then categorised into “good” (>VCI50) and “bad” (<VCI50) condition classes according to Equation (2), except for the PSRI, where a reverse condition had to be used because of the inverse nature of the index, as follows:

The crop conditions of pixel i,j were then characterised by a value in the range (0–5), representing the number of VIs exhibiting a “bad” condition (0: best condition; 5: worst condition). This process results in a six-category crop condition map, as also illustrated in Figure 2.

The vegetation condition evolves over time, so its quantification is obviously sensitive to the acquisition time of the observations involved.

For validation at the parcel level, the crop condition maps were produced typically two or three times per month for the relevant part of the growing season (May to August) for the six reference parcels from the year 2023, depending on cloud cover (Figure S2).

To assess the reliability of our methodology on a larger scale, we also conducted investigations at the level of AE zones, counties, and entire country for three selected years with various meteorological characteristics (2017, 2022, and 2023), based on the same reference years (2018–2022). We focused on the period of July as the one most relevant for comparisons with the yield data, as suggested in the literature [6,11,12] and corroborated by our experience (see Section 3 (Results)). For each AE zone, we identified 1-3 dates with clear acquisitions over the period of July and applied automated cloud masking complemented visually and manually whenever needed. The number of images needed to cover the month of July depends on the cloudiness of the period and hence the meteorological conditions of a given year (Figure S2). In 2022, during the drought episode, we produced two full complete coverages for Hungary with 3-3 essentially cloudless data takes, whereas in 2023 cloud cover and haze fragmented the mosaic considerably. In 2017, in addition to cloud cover, the amount of available imagery was also influenced by the fact that Sentinel-2B became operational in the second half of July that year. Crop condition mapping was carried out for each of the clear acquisitions per AE zone, as described above. Crop condition maps were then aggregated for statistical evaluation at different levels. This was conducted annually, using stacks of 10-metre resolution crop condition maps including all available dates for July (Figure S2). Wherever a pixel was mapped multiple times, the worst mapped condition was taken into account.

2.5. Crop Yield Data

High-resolution yield data from 2023 were also acquired and used for validation over six maize parcels (Table 1). It was derived from harvester-based (John Deere S770) precision yield maps based on the grain yield monitor. The parcels, located in Tolna county, Western Hungary (Figure 1c), were typically exposed neither to drought nor inland excess water in that year. The size of the parcels ranged from 2.51 to 70.97 ha. The yield data were cleaned to remove erroneous records at the end of the harvesting rows due to turnings by the vehicle. We used percentile-based filtering for each parcel individually, resulting in realistic values for maize (maximum yield of 13–16 t/ha). After filtering, all points were aggregated to the Sentinel-2 grid with a spatial resolution of 10 m using the mean of the yield points over each grid cell. The yield raster combined for the six parcels was characterised by the following statistical values: minimum: 0 t/ha; median: 8.44 t/ha; maximum: 15 t/ha.

Table 1.

Metadata of the maize parcels with harvester-derived yield data.

Census data were used as another fundamental data source for the study. Annual county-level (NUTS3) yield data were acquired from the database of the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (HCSO) [44]. Relying on data retrieved from farmers, it reports the amount of harvested grain, mean crop yield, and size of the harvested area for the main crops per county for each year. In the case of maize, data on grain and hybrid maize were reported together. In 2020, there was a change in the methodology used by the HCSO that might have affected the results to some extent (including some territorial inconsistencies among counties), but because of the lack of further information, this effect was not investigated in detail in this study.

2.6. Damage Claim Data from the Hungarian Agricultural Risk Management System (ARMS)

Since 2012, farmers in Hungary have been able to submit damage claims for the compensation of 9 types of weather-induced crop yield losses under the ARMS [19,20]. The majority of damage claims were clearly related to drought in each studied year, but they also include smaller amounts caused by other extremes and local effects such as inland excess water, agricultural floods, storms, cloudbursts, and hail. These claims were also included in the study. Drought claims can be submitted from the 1st of April to the 30th of September. According to the current legislation, a drought event is considered realistic when the total rainfall is less than 10 mm for 30 consecutive days during the growing season of the claimed crop, or the total rainfall is less than 25 mm for 30 consecutive days and the daily maximum temperature exceeds 31 °C for at least 15 days. In the case of notification, irrespective of the actual time of occurrence of the weather phenomenon and natural event, the time stamp to be taken into account is the time when the damage was first noticed on the crops grown in the area affected by the damage.

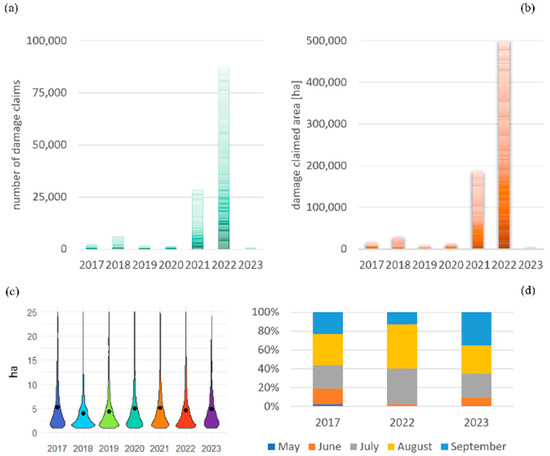

Damage claims were handled anonymously in this study for data protection reasons. Claims submitted to the ARMS from 2017 onwards were used to fit the era of combined availability of Sentinel-2A/2B satellite imagery. During these years, the quantity of maize-related claims submitted to the ARMS was an order of magnitude higher than those related to other crops (Figure S1), and the farmers faced maize damage every year. Figure 3a shows the number of damaged maize parcels between 2017 and 2023. In 2021 and 2022, these numbers were record high, and in 2022, the capacity of the underlying claim control mechanism was clearly overwhelmed. Figure 3b shows the total area of maize claims per year. The absolute record was in 2022 when a total area of approximately 500,000 ha was claimed. The area of maize claims before 2021 never exceeded 34,000 ha. In general, the average size of the claimed parcels is approximately 5 ha, but most of the parcels are smaller (Figure 3c), which emphasises the necessity of using high-spatial-resolution data for monitoring. In the case of maize, farmers usually submit their claims between May and September, if this is justified (Figure 3d). The relative frequency of claims was higher in the eastern half of the country, with most claims made in the easternmost county of Hungary [23].

Figure 3.

Damage claim statistics in Hungary by year during the study period of 2017–2023: (a) number of damage claims for maize; (b) total area of maize damage claims by year in the relevant years of the research; (c) distribution of the areas of claimed parcels in different years (larger than 1 ha); (d) percentage of claims per month of submission for the studied years.

2.7. Post-Processing of Remote Sensing Data and Statistical Analysis

2.7.1. Phenology Reconstruction

For the crop condition calculation, the estimation of VImax(2018–2022) and VImin(2018–2022) (Equation (1)) is a fundamental step (see Section 2 (Methods)). Given the fact that differences are expected to occur among AE zones, first, we performed a visual reconstruction of maize phenology profiles using all available VIs in order to study the spatial variability of the maize growth for each day of the vegetation season. Smoothing was used during the reconstruction but this was omitted during mapping. The reconstructed profiles demonstrate the applied VImax(2018–2022), VImin(2018–2022), and VCI50 values visually.

2.7.2. Parcel-Level Analysis

Once the VCI50 values were available for crop condition mapping (Equation (2)), a parcel-level study was conducted. As the parcels are located in the 15th AE zone, the corresponding HCSO yield values were used. The main aim was the quantification of the relationship between the county-level and parcel-level crop yield and the crop condition categories to justify the applicability of the VCI approach in Hungary. An additional aim was the selection of the most appropriate time period (prior to harvest) that can be used to support yield mapping. For this purpose, a machine learning method (Random Forest (RF) [45]) was applied.

In order to support large-scale decision making, yield predictions are more effectively represented on an ordinal (i.e., discrete and ordered) scale. This is because continuous variables can be difficult to interpret without sufficient contextual knowledge of the region. There are two potential approaches for deriving meaningful ordinal information from yield predictions. First, models that produce continuous yield outputs can be applied, followed by a clustering of the yield into categories (y1–y6). Alternatively, models that generate categorical outputs can be used directly. Given that the crop condition map (which will serve as a predictor) is a thematic map with six categories, the classification task becomes simpler and is, therefore, the preferred approach. Additionally, simpler models reduce the risk of overfitting, and when well-defined categorical boundaries are used, the impact of measurement errors can be minimised.

Since the categorical boundaries had not yet been defined before the classification task, two to six categories were created based on the yield measurements in a way that ensured that the resulting dataset was as balanced as possible. To achieve such categorisation, the empirical quantile function was used. This means, for example, that for two categories we used the median, since by definition the number of samples below and above the median is equal; for four categories, the quartiles were used. In general, the breakpoints can be defined as follows: b(x,n) = {qx(k/n) | k = 0,1,2,…,(n − 1)}, where x is the set of yield values, n is the number of categories, and q is the empirical quantile function. Category breakpoints can be determined by the observed yield values at the NUTS3 level or at the parcel level. Both versions were tested in this study.

In our approach, the gridded yield data for the six parcels were transformed into discrete yield maps, which were categorised along the different, pixel-based breakpoints (given in Table 2; top) into 2–6 categories. Values from all the six parcels were used jointly to determine the breakpoints. We also used the time series (2000–2024) of the NUTS3-level maize yield data from Tolna County to create an alternative categorised yield map with different breakpoints (Table 2; bottom).

Table 2.

Breakpoints used for the categorisation of the high-resolution, harvester-derived yield using the empirical quantile function (top) and the county-level yields (bottom). Row names are the category numbers, while column names represent the breakpoints of the yield categories. For example, in the upper table, in the case of 3 categories, the yield falls into the 2nd category if it is between 7.7 t/ha and 9 t/ha.

In order to match yield categories to the derived crop condition maps, we restricted the beginning and the end of the time period to be suitable for the detection of the crop condition associated with the final yield. According to this logic, the time period from May to August was defined.

Once the categorised, parcel-based yield maps (2–6 categories from y1–y6) and the crop condition category maps (6 categories from 0 to 5) were available, a Random Forest-based classification was applied with cross-validation. This well-established machine learning method is capable of achieving high accuracy while remaining interpretable using importance scores. Importance scores are particularly valuable for this kind of analysis, because the ranking of variables can be examined and justified using previous studies and expectations. In this study, only the variables contributing to a cumulative relative importance of 90% after ordering were considered important. This was an arbitrary selection that was justified by our experience that the omitted variables did not contribute significantly to the prediction (see Figure S3). In this way, if the model achieves good quantifiable performance while the order of importances is realistic, this is a good indication that it is structurally correct and generalizable. However, Random Forests can easily be overfitted. This makes it particularly important to separate a well-established test dataset along with the training data and measure the performance on that. Therefore, the training data consisted of 70% of the available pixels. The model’s performance was quantified with accuracy and F1 score metrics. The latter was particularly important when NUTS3-level data were used for categorisation because it produced unbalanced datasets.

2.7.3. Country-Level Analysis

Based on the experiences from the parcel-level study encouraging further applications, the crop condition mapping methodology was also applied at the country level. The original high-resolution crop condition maps are available at a 10 m resolution. These data were aggregated to NUTS3 and AE zone levels in order to be comparable with the available census data. A 2 km aggregation was also used for visual representation.

Based on the derived data, first the NUTS3-level maize yield data were used and a relationship was sought between the categories and the census-based yield data. Simple linear models were constructed, and the best model was selected to predict crop yield and yield loss using crop condition maps from July. For models constructed from one or two years of data, independent validation of the excluded years was possible and, hence, performed and analysed.

As an added value of the study, the informational content of the ARMS damage claims was studied by quantifying their relationship with the crop condition mapping. For this purpose, the geolocated damage claim data were associated with the NUTS3-level regions and statistics were provided to demonstrate the relationship between the claimed damage and the observed crop conditions.

We used both opensource and commercial software, as follows: GEE [43] for processing satellite data and deriving crop condition maps; QGIS Desktop 3.28.15 [46] to pre-process non-satellite data and to create illustrations; R [47] with packages (doParallel [48], dplyr [49], e1071 [50], ggplot2 [51], gridExtra [52], raster [53], randomForest [54], readxl [55], sf [56], sp [57], tidyverse [58]); and IDL [59] and Excel [60] for the statistical tests, as well as for visualisation.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristic Maize Profiles Based on the Different Vis

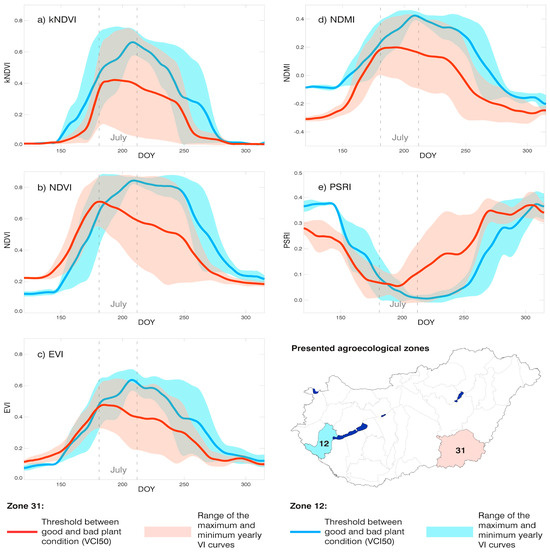

Figure 4 shows the maize-specific VI profiles from two selected agroecological zones during the growing season in Hungary, as follows: one from the most drought-affected lowland area in the east and one from a productive and well-performing area in the west. The NDVI profiles show that in years with optimal weather conditions, the profiles can be similar (considering the maximum values). Considering the kNDVI and EVI profiles based on the reference years (2018–2022), the best productivity was in the western region during the peak of the vegetation season. All indices show a shorter growing season in the eastern part, and it seems that the season usually starts earlier in these regions, likely related to earlier planting and/or faster development. The greatest differences between the VCI50 profiles (i.e., those curves that define whether the individual VCI will be good or poor; see Equation (2)) of the two zones can be observed typically around DOY 180–190, indicating that the period of July is a good selection for crop condition mapping. The VCI50 profiles also show that in areas with more favourable climatic conditions, the threshold is more permissive in terms of damage severity (note that damage claims are typically rare in these areas). Figure 4 also shows that VI profiles can vary throughout the growing season among different AE zones.

Figure 4.

Characteristic maize-specific VI profiles from two contrasting agroecological zones in Hungary (zones 12 and 31; see Figure 1b for zone definitions) based on the selected vegetation indices for the time period of 2018–2022: (a) kNDVI; (b) NDVI; (c) EVI; (d) NDMI; (e) PSRI. Red colours represent one of the most drought-affected, while blue indicates one of the least drought-affected regions in the country. The range of vegetation indices from the reference years’ maximum and minimum mode (peak values of the year-specific histograms) time series are shown on the graphs, and the thick lines (termed here as VCI50) represent the boundaries of the good (VCI above 50) and bad (VCI below 50) conditions during the growing season of maize, except for the PSRI, for which the thresholds are opposite (see Figure S4 in the Supplement). The dashed vertical lines indicate July. Smoothing was applied to the figure to facilitate easy interpretation of the profiles.

Figure S4 shows the frequency distribution of the studied VIs in one AE zone (zone 28) on the mean July Sentinel-2 VI composite. The figure is representative of the other AE zones. Obviously, the different vegetation indices did not respond to the stress effects in the same order and with the same sensitivity, which justifies their use as an ensemble. While most of the indices are similar in their overall pattern, the PSRI exhibited different behaviour caused by the fact that it is tailored to the quantification of the yellowing processes (i.e., leaf senescence), unlike the others, and is sensitive to soil water content deficits, moisture, or greenness.

As the VI time series indicates in Figure 4, it is expected that the characteristic VImax(2018–2022) and VImin(2018–2022) values of the AE zones will be markedly different within the country. Indeed, as shown in Figure S4, the zone-specific, individual vegetation indices show remarkably different distributions in the studied years, mostly due to the varying environmental conditions and, probably, other factors like cultivar selection as well, which is not discussed here in detail. As a result, the most frequent VI values detected in the various years of the given period are significantly different (those that define VImax(2018–2022) and VImin(2018–2022); Figure S4).

Using the VI histogram peaks (mode values), the VImax(2018–2022) and VImin(2018–2022) values were calculated for each individual AE zone, making it possible to derive pixel-based maize condition maps at different levels, as follows: agricultural parcels, AE zones, and counties. Note that the AE zones were used to define the VCI50 values for the individual pixels for crop condition mapping, but for further steps in the analysis, another aggregation level was used (NUTS3), given that the census data are available at the county level.

3.2. Parcel-Level Crop Condition Mapping and Yield Prediction

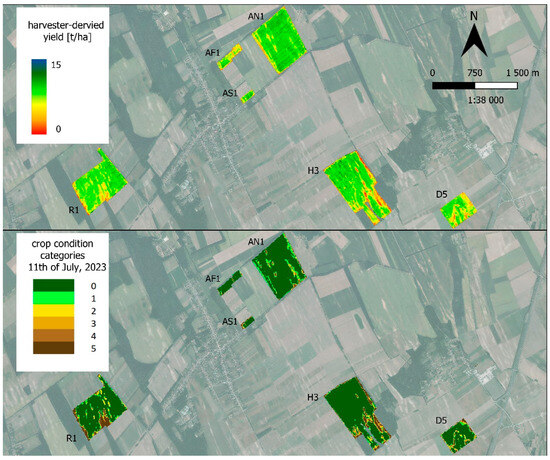

Figure 5 shows a comparison of the high-resolution maize yield map aggregated to the Sentinel-2 grid and the crop condition maps derived thereof, for the six parcels used in the study. The figure clearly demonstrates the covariation of the yield and the crop condition. Interestingly, low yield is not entirely associated with the edge of the parcels but is likely linked with topography and soil condition variability. Though the study year was not drought-affected, there is a remarkable within-parcel variability in the yield, which means that all the six categories are present in the calculated crop condition map. This feature corroborates the usefulness of the parcel-level study for the selected fields.

Figure 5.

High-resolution, harvester-derived maize yield data for the six reference parcels on the Sentinel-2 grid (above) and the calculated six-category crop condition map (below) for the six reference parcels located in Tolna County. The colours represent the crop condition according to the legend (0 is the best; 5 is the worst category).

A machine learning method was aimed at studying the predictability of the observed yield data at the parcel level using the crop condition mapping categories. Table 3 shows the confusion matrix of the prediction based on the six-category yield map and crop condition time series when we chose the breakpoint from harvester-derived yield values (Table 2). According to the results, the prediction accuracy was high, and most of the misclassifications were in the adjacent categories. Misclassification was particularly rare for categories y1 and y6 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Confusion matrix of the crop condition map time series yield prediction based on the breakpoints from the harvester-delivered data. The colour scale, from white to red, was used to indicate the number of pixels in each class, from smallest to largest.

Table 4 shows the prediction accuracy based on two yield categorization approaches for yield maps and crop condition time series. In all cases, the accuracy of the yield maps based on NUTS3-level means was better than the harvester-derived yield approach, but these were similar in both cases. The confusion matrices in the harvest-derived yield approach were more stable (the datasets were less unbalanced). The results indicate that the four-category approach is not suitable for either method. In order to use RF methods to validate the crop conditional mapping method, it is important to include measures that indicate the structural correctness of the given RF model. In Table 4, it can be clearly seen that the most important features for the model are the condition maps from July. When predicting with the two-category yield maps and the worst-condition composite based on the July period, the accuracy was 82.7% and the F1 score was 0.75 based on the NUTS3-level yield breakpoint, while the accuracy was 74.06% and the F1 score was 0.66 for the breakpoint based on the harvester-derived precision yield data.

Table 4.

Accuracy values of the yield predictions at the parcel level according to (a) breakpoints based on harvester-derived yield and (b) breakpoints based on NUTS3-level mean yields (2000–2024). For 4 of the categories, the results were not interpretable.

These results indicate that the six-category crop condition mapping is useful and provides an effective method for the characterisation of final maize yield. This suggests that the county-based generalisation is possible and meaningful, and the most relevant images for crop condition mapping based on Sentinel-2 data are those acquired in July.

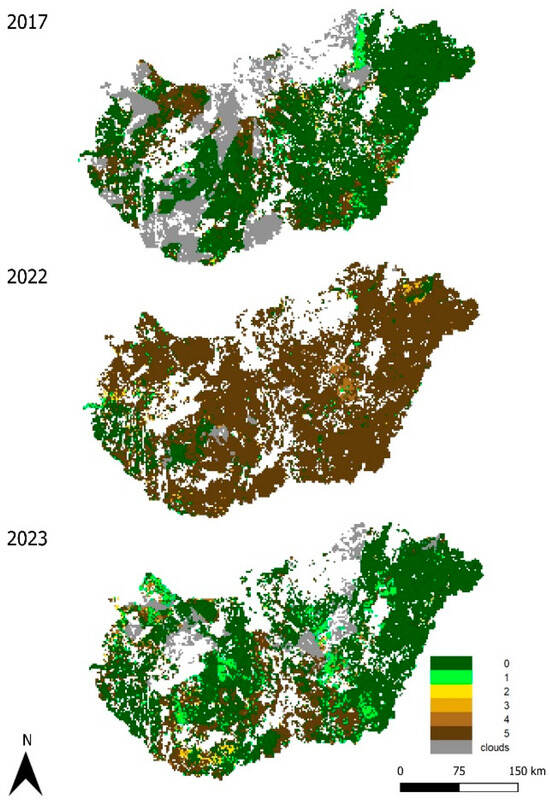

3.3. Country-Level Crop Condition Mapping

Figure 6 shows the aggregated, pixel-level crop condition map for July for the three study years (2017, 2022, and 2023). The raw, pixel-based data were aggregated to 2 km for better visualisation. For the aggregation, the data content was defined as the majority category value of the crop condition within the 2 km grid cell.

Figure 6.

Aggregated crop condition categories for July for the 3 study years (2017, 2022, and 2023). The spatial resolution of the aggregation is 2 km. The colours of the maps represent the crop condition according to the legend (0 is the best; 5 is the worst category). The grey colour represents missing data, while the white colour indicates the areas where maize was not present in the given year.

The three maps clearly show the remarkably different maize conditions in July for the different years. Interestingly, the maps mostly represent the two extreme categories. The underrepresentation of the intermediate categories (1–4) is due to the fact that these values are often on the borders between damaged or low-yielding parts of the parcels and the best-condition parts (see Figure 5). In 2017 and 2023, clouds caused more data gaps than during the extremely dry summer in 2022. At the country level, year 2023 showed the largest inhomogeneity. This is likely associated with the presence of cloud cover and the heterogeneity of weather conditions (Figure S2). The number of 2 km grid cells in which maize was cultivated decreased continuously over the three study years, with 18,122 pixels mapped in this way in 2017, 17,688 in 2022, and 16,836 in 2023. This may partly be due to crop rotation, but in addition to this, the extreme drought of 2022 probably also played a role in the crop selection of the farmers in 2023. In 2017, maize condition category 0 (i.e., the best) was the most frequent, with 57.41% of the mapped 2 km pixels, followed by cloud-affected areas (19.8%), and the worst-condition category (5) represented 17.13%, while the other categories did not exceed 3% each. In 2022, 87.05% of the grid cells were associated with the worst category (5), 7.46% received the best category (0), while the other categories were present in less than 2% each. In 2023, the highest percentage of the grid cells were associated with a value of 0 (59.75%), followed by category 6 with 21.28%. A total of 7.91% of the grid cells were affected by cloud cover, category 1 was present in 6.56%, while the other categories were present in less than 2% separately.

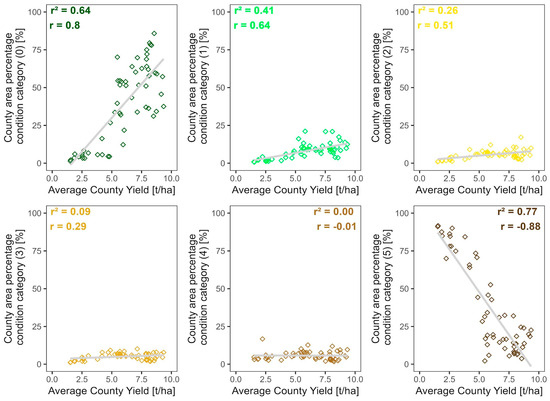

The category values were used to quantify the relationship between the NUTS3-level maize yield and the estimated crop condition. The lowest average county yield of the three years studied was 1.52 t/ha in 2022 and the highest of 9.35 t/ha in 2023. The average county yields were 6.51 t/ha in 2017, 3.45 t/ha in 2022, and 8.1 t/ha in 2023. The percentage of the best crop condition category varied between 21.80% and 75.02% in different counties, with the average being 53.3%. By comparison, in 2022, the minimum of category 0 was 1.36%, the maximum was 33.81% and the average was 8.63%. In 2023, the minimum of the best condition was 31.1%, the maximum was 85.82%, and the average was 55.49%. The average July area ratio of the intermediate categories (1–4) was 6.89% in 2017, 4.34% in 2022, and 7.3% in 2023. The worst crop condition category reached a minimum of 2.15%, an average of 19.19%, and a maximum of 44.29% at the county level in July 2017. In 2022, the proportion of counties in the worst category (5) varied between 32.42% and 91.67%, with an average of 74%.

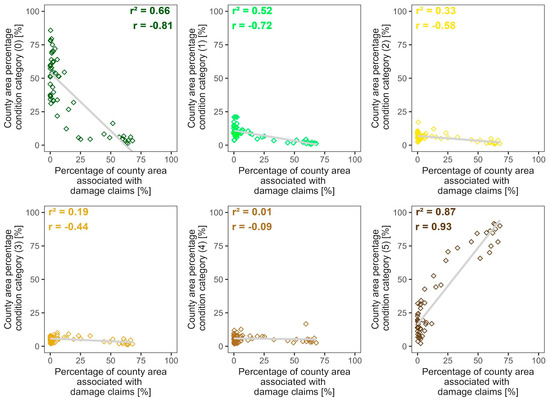

Some of the area percentages of the maize condition categories aggregated to the county level show good correlations with the county average yield values of the given areas and years in the three years examined (Figure 7). For the best crop condition, the explained variance was 64% when all years and counties were considered together. In the case of the worst crop category (5), the explained variance was 77%. As expected, the direction of the positive correlation of the best category with respect to yield gradually turned in a negative direction towards the worse categories. The covariance between the yield and the county area share of the category was low for the intermediate categories. To assess the potential effects of cloud cover on the mapping process, we correlated the error of the category 5 linear model with the county cloud cover values and found no correlation (Figure S5), implying no significant distorting effects.

Figure 7.

Correlation of the percentage of county area of a given crop condition in July with county yields based on 3 years (2017, 2022, and 2023) of data for the whole country based on NUTS3-level maize yield data. The six panels represent the six crop condition categories (from best to worst).

Given the importance of the NUTS3-level early yield forecast, two approaches were tested. The first method aimed to estimate NUTS3-level yield data (Figure 7), while the second used yield loss as the target variable. Yield loss was calculated based on the maximum yield per NUTS3-region during 2010–2023 and the actual yield in a given year. We constructed linear models using all possible combinations of the years, where the predictor was the area share of the crop condition categories. The maximum explained variance was associated with the estimation of the yield loss, so only those results are presented here.

Table 5 shows the explained variance of the different models for yield loss. Clearly, some models are characterised by relatively high r2 values. The most striking feature of the table is the importance of year 2022 regarding the strength of the correlation, which means that r2 can reach high values (e.g., 0.6) only if 2022 is included. This points to the importance of the inclusion of this extreme year in the analysis.

Table 5.

r2 values for the fitted linear models using data from single years or from the combination of different years for the crop condition categories (0–5). The fitted models used the area share of the crop condition category as the independent variable and the NUTS3-level yield loss as the target variable.

The best model was associated with category 5 data, and it used data from 2022 and 2023. In this case, the fitted model equation was y = 0.076x − 0.290, where x represents the county area share of category 5, and y represents the NUTS3-level maize yield loss in t/ha. The model explained ~89% of the observed temporal and spatial variability of the census-based yield loss.

The predictive power of the fitted models was tested on independent data, which in our case meant that data from one or a maximum of two years was used for validation (i.e., those years that were not used for fitting, see Table 5, considering that for the last model in Table 5, validation is clearly impossible). We only validated models with r2 > 0.6 (Table 5). The results indicate that explained variance varied between 0% and 24% in the independent data, which means a low predictive power. Three models can be mentioned here. In the case of the model fitted using data from 2017 and 2022 and using the category 1 area share, the explained variance was 23% (bias = 1.5 t/ha, which means an overestimation). Using data from 2022 and 2023 with the 0 category, the r2 was 0.24 (best value), with an underestimation of the mean yield loss (bias = −0.95 t/ha). Using category 1 from the same time period and using 2017 as validation year, the explained variance was 23% (bias = −1.2 t/ha). The results highlight that more data are needed to construct more robust models for yield loss prediction.

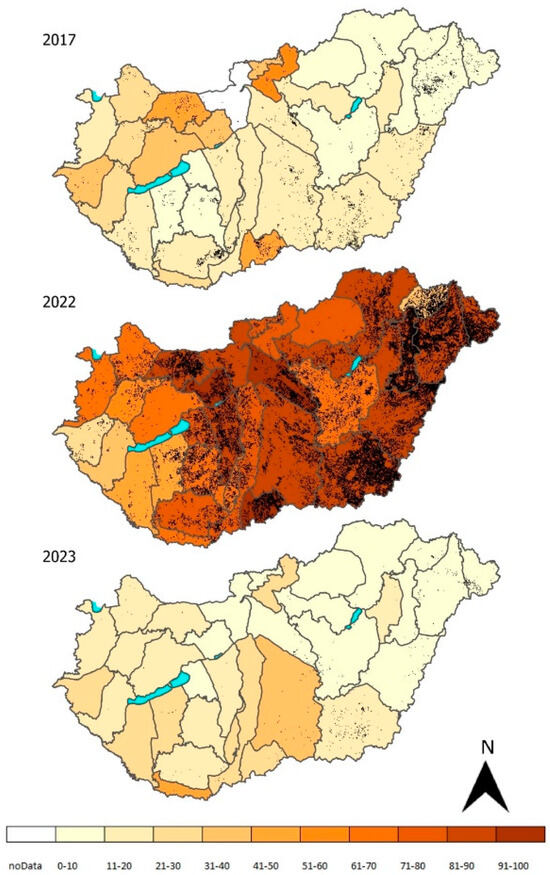

3.4. Relationship Between the Claim Data and the Crop Condition Mapping

Figure 8 shows the percentage of maize in the worst condition (category 5) in July in the different AE zones in the study years and also the number of claims in the given years. The drought severity in the study years, based on the crop condition maps, represents the same order as the number of damage claims. It is important to note that the colours in the maps do not represent the area of maize parcels. According to Figure 8 (also supported by Figure 7), the drought severity was spatially variable within the country and not all regions were affected equally, even during 2022. This is in accordance with the spatially variable VCI50, as shown in Figure 4. In other words, mostly in Western Hungary, the crop condition result can be similar to that observed in eastern Hungary, even for less severe damage. However, this does not significantly affect the applicability of the methodology, as in these regions, farmers usually submit fewer claims. If a more severe drought occurs in the western part of the country, the system can be tightened by increasing the number of the reference years, and its efficiency can be improved for this area as well.

Figure 8.

The distribution of the worst crop conditions category (5) according to agroecological zones in the studied years and the centroid points of the damage-claimed grain maize parcels.

In 2017, the percentage of claimed maize area in the county compared to the total sown grain maize was 4.29% on a national level. There were counties where the claim was only 0.14% of the sown maize fields, while the maximum claimed area was 15.14%. In 2022, in the county least affected by the extreme drought, the claim was 5.89%, while the maximum was 68.02%, and the average was 46.88%. In 2023, the country average was only 0.58%.

For some of the categories, the percentage of maize condition categories aggregated to the county level shows a good correlation with the percentage of the county area associated with the damage claims of the given areas and years in the three years examined (Figure 9). In the years studied, there was no real intermediate state, either the best or the worst categories predominated, which is why these categories showed the highest correlation with the damaged areas. In case of the best crop condition, we observed a relationship of r2 = 0.66, while for the worst crop category, we observed r2 = 0.87. As expected, the negative correlation of the best category with the area subject to damage claims gradually turns into a positive direction towards the worse categories. The less represented categories approached zero in their dependence rate.

Figure 9.

Correlation of the area percentage of the given crop condition category in July with an area of associated damage claims based on 3 years (2017, 2022, and 2023) of data for the whole country based on the NUTS3-level aggregation. The six panels represent the six crop condition categories (from best to worst).

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Maize Profiles/Remote Sensing of Crop Production/Growth

Phenology reconstruction is a critical process for understanding the environmental factors that influence maize production and final yield [61,62]. Remote sensing observations are widely used for this purpose due to the wide temporal and spatial coverage of satellite imagery. The objective of establishing a phenological profile varies; it can identify phenological phases to support crop protection management decisions [63,64,65,66], serve as a basis for land cover classification [67], help to distinguish between irrigated and non-irrigated areas [68,69], and assist in mapping development anomalies and damage [70,71,72,73]. In addition to time-series-based approaches, methods for comparing a single time-point observation with a healthy histogram as a basis also exist, such as the one applied by Cvetković et al. [74] using UAV imagery.

Our approach integrates and develops further these two methods by establishing ideal profiles for specific AE zones in time series while comparing the current state with the expected VI values at a given moment in time for mapping purposes. By combining the indices, we have adopted an approach more robust than those using a single VI [75]. Saturation of the NDVI index is a well-known problem [27,28,29,30], which we also observed in our study (Figure 4). To mitigate this, we included two additional enhanced indices (kNDVI and EVI) sensitive to biomass. The application of the Sentinel-2 red-edge band in the PSRI index further increased the sensitivity of our method. Complemented with NDMI, our method also takes into account the moisture conditions. From our results it became clear that the individual indices show different responses to current conditions or damage (Figure 4, Figure S4).

The VI profiles generated in different AE zones highlight the month of July as the period with the most significant differences. Furthermore, the histograms constructed for specific time points emphasised the importance of a severely drought-affected year, such as 2022, to set the scale for the development of a highly sensitive methodology based on the VCI principle.

4.2. Fine-Scale Crop Condition Mapping and Yield Prediction

Thanks to the increasing number of Earth-observing satellites, combined with the advent of free and open data policy, there is a major increase in the number of crop condition detection and extreme weather (e.g., drought) related studies. The significant enhancements in data accessibility as well as in temporal and spatial resolution open up the possibility for the proliferation of fine-resolution studies, also closely linked to the needs of precision agriculture and the necessity of resource use efficiency in the context of climate change.

Traditionally, high-resolution, VCI-based mapping is primarily based on Landsat, which provides a long reference time series and extended analysis, e.g., using the Temperature Condition Index (TCI) and Vegetation Health Index (VHI) [76,77]. Significantly fewer drought-related studies have been conducted using Sentinel-2 imagery compared to other freely available optical satellite data sources [78]. This is probably due to the shorter time series and the lack of land surface temperature measurements. However, among others, the red-edge bands of Sentinel-2 provide a valuable addition for assessing the state of the vegetation [78,79]. The higher spatial resolution is advantageous for detecting smaller, more localised damage events such as wind [80], hail [81], or insect damage [71,82]. In addition, with the expansion of precision agriculture, the relatively frequent and freely available time series are becoming increasingly important.

Several studies have shown a strong correlation between VIs and crop yield [12,14,15,18]. The inclusion of multiple indices has helped to refine these relationships [75,83,84,85] and to detect within-field heterogeneity [13,14,83,86]. Our crop condition maps similarly reflect within-field variability (Figure 5).

In high-resolution cases, Random Forest models are frequently used for prediction, and it was shown in different studies that they provide the best possible results [13]. In our case, the two-category yield mapping approach, either with harvester-derived or NUTS3-level yield breakpoints, gave the best results. Based on the results obtained on the study parcels, data representing the month of July, converted into a crop condition map, show the strongest relationship with the expected yield (Table 4). This is in line with other studies that have shown the strongest correlation with yield in the periods 105–135 days after sowing [13] and two months [6,11,87,88] before harvest. In our study, we found the best fit for the periods of 96–110 days after sowing and 70–85 days before harvest. The accuracy of our yield prediction based on the July crop condition composite was 82.7%. The derived composite can be used to optimise the planning of on-the-spot control, as the map provides an opportunity to compare it with the county’s 24-year median yield and to determine the situation of the most affected areas. VCI-based approaches using Sentinel-2 data are rare, as most published studies focus on vegetation with constant cropping conditions [89,90]. We have demonstrated the possibility of using the VCI approach over arable lands with active crop rotation. A few Hungarian studies predicted yield dependence using UAV-based VIs [18,91]; however, while the higher resolution sometimes leads to better correlations [92], it does not allow high-resolution country-level mapping.

4.3. Country-Level Crop Condition Mapping and Yield Prediction

Most studies focusing on drought monitoring and yield forecasting of maize at the country level rely on medium-resolution satellite data. This is mainly due to the good temporal resolution and the availability of long time series. Studies on crop conditions at this resolution tend to focus on drought due to the spatial scale of the phenomenon [70,93,94,95]. Some works deal with the assessment of post-flood conditions as well [96]. Given the long time series, studies using the VCI, TCI, and VHI approaches are common [87,93,94,95,96]. However, ignoring crop rotation significantly affects the temporal sensitivity of VCI values [94].

Here we compared the aggregated maps derived from Sentinel-2 data with county-level census-based yield data and existing literature to assess their predictive capabilities. The 2 km aggregation proved an effective way in delineating the most affected regions, similar to large-scale, coarse-resolution studies conducted in other study areas. The work of Wu et al. [93] highlighted the significant differences in the NDVI histograms during the growing season in certain years, which were also illustrated and extended to other VIs sensitive to crop vulnerability. Several studies also suggested that late July to early August is the most appropriate period for yield prediction; we have corroborated this finding by observing acceptable correlation between July crop condition maps and ancillary yield data. The best condition category provided a correlation coefficient of r = 0.80, while the worst condition yielded r = −0.88, with the results comparable to those of Kogan et al. [87] (r = 0.78–0.88 Pearson correlation for maize in the USA) and Moussa Kourouma et al. [95] (r = 0.64 for Ethiopia). In a Hungarian context, Bognár et al. [11] published a study on county-level correlations with AVHRR data from late July with 90% of explained variance, although in these studies the precise vegetation cover type was not yet assigned to clear pixels.

4.4. Assessment of Damage Claims

The use of remote sensing in the claim adjustment process appears to be driven primarily by government initiatives rather than by the insurance industry itself. The increasing availability of satellite data with higher spatial, temporal and spectral resolution has the potential to improve such processes. However, the limitations of these methods need to be understood [97].

It has been shown that the accuracy of yield loss prediction can be improved by integrating additional data sources beyond remote sensing [98]. However, the inherent subjectivity of field data collection is well recognised [81]. Furthermore, while there is a strong correlation between the distribution of damage and the spatial patterns shown on maps (Figure 8), these maps do not always accurately reflect the actual spatial distribution of damage. For example, in the western regions of Hungary, typically less affected by drought, damage detection thresholds are lower compared to those observed in the eastern part of the country and hence the crop condition maps are more sensitive (Figure 4). This is an intrinsic characteristic of the methodology as the scaling is conducted at the level of each AE zone over time; nevertheless, from a practical perspective, this is not a major hindrance as farmers in these areas tend to make fewer claims anyway. In contrast, in the eastern regions, farmers are more likely to submit claims, even if the biomass conditions do not appear to warrant them according to the maps. These areas are often characterised by sandy soils and ribbon farms, with noticeable economic and social differences between the eastern and western regions of Hungary.

4.5. Limitations of the Study

As most of the claimed parcels in Hungary are less than 5 hectares in size [23], high-resolution RS data are required to validate these claims. While Landsat satellites provide a long time series, the 16-day revisit time, combined with potential data gaps caused by cloud cover, significantly complicates the mapping. In addition, their 30-m multispectral spatial resolution limits the mapping of inhomogeneities within parcels. Amongst satellites with free and open data policy, Sentinel-2 offers a better alternative. Although the data of Sentinel-1 also meets the finer resolution criteria and is not affected by clouds, radar data have traditionally been combined with optical data for studying vegetation [99]. However, more and more research is based on radar data alone [100,101]. In the current study, we focussed solely on Sentinel-2 data due to our requirements in terms of temporal and spatial resolution.

Acquiring countrywide reference data is also challenging. Agricultural parcels on Long Term Field Experiments (LTFEs) are usually too small for the resolution of Sentinel-2. At the same time, the accessibility and quality of field data for model training, calibration and validation can strongly influence performance [98]. As the applied method is sensitive to green biomass and photosynthetic activity, yield losses due to heat or UV stress during flowering cannot be effectively monitored [98], and weed infestations can lead to misleading results. In addition, farmers are often reluctant to share yield data for a variety of reasons. Moreover, while the crop yield dataset of the HCSO has a long archive, a methodological change occurred in 2020 to improve data reliability. However, the dataset published in 2017 still reflects the older methodology, which can lead to a decrease in the correlation in our county-level studies. Finally, human factors also need to be taken into account when processing and verifying claims. Farmers’ claims of damage and their likelihood of claiming via ARMS are likely to be influenced not only by weather but also by social and economic factors. Similarly, the field inspectors’ sensitivity to damage during assessing claims may vary among regions [13]. From a research perspective, it would be highly beneficial to develop a standardised field assessment system that could aid future methodological developments.

Another limitation of the study is the short time period that was addressed (only three years). However, we believe that the available additional years (2018–2021) were not significantly different from the conditions in 2017 and 2023. The July cloud cover of the omitted years was also significant, so in this study, we did not carry out country-wide processing of the remaining four years. An additional strong message of the paper is the necessity of the inclusion of severe drought years like 2022 in Hungary. However, as the drought severity was spatially variable, there are large differences among the worst crop conditions detected, as demonstrated by the crop profiles. An alternative approach might be to harmonise VCI50 values and hence category thresholds among different regions, e.g., to transfer them from the eastern to the western part of Hungary, but in this case, planting date reconstruction would also be worth using [73], as it might affect the categorisation and the relationship with yield or yield loss.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

There is a vast amount of literature on crop condition mapping. However, most of the studies focus on a single vegetation index, and validation is typically restricted and problematic. Here, we presented a crop condition mapping workflow that is scalable and relies on a set of VIs that ensure robustness. Maize phenology mapping, parcel-level analysis, and country-wise generalisation together demonstrate the usefulness and applicability of the approach. The added value of the study is the presentation of data from the anonymous damage claim system that corroborated the results.

The inclusion of additional years is highly recommended to further refine the methodology. More parcel-level yield data would also be of great importance and can further contribute to the improvement of the approach.

Further research is needed to study the scaling of the anomalies that define VCI, especially for determining the worst crop condition. Also, the weighting of individual indices, now set evenly, is also planned to be optimised in follow-up studies by taking into account their respective importance scores to enhance the predictive power of our models. These enhancements, combined with the expected availability of a substantial set of precision yield data, should enable the development of quantitative models predicting not only categories but also actual yield and potential yield loss.

In addition, we plan to extend our investigations to include Sentinel-1 data in crop condition mapping.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/rs16244672/s1, Figure S1: The most claimed crops in the studied years; Figure S2: Dates of the crop condition maps used in the validation process. The July maps were used for the county-level validation and the full 2023 map series was used for parcel-level validation; Figure S3: Order of importance scores of the crop condition map time series yield prediction based on breakpoints from the harvester-delivered data with six categories; Figure S4: Spatial distribution of the indices for maize in the 28 agroecological zones during the study period; Figure S5: Relationship between the county average yield and pixels with missing data due to clouds.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.B., D.K. and A.K.; methodology, E.B., R.H. and Z.B.; software, E.B. and R.H.; validation, E.B., R.H., D.K. and Z.B.; formal analysis, E.B.; investigation, E.B.; resources, E.B.; data curation, E.B.; writing—original draft preparation, E.B. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, E.B., A.K., Z.B., D.K. and R.H.; visualization, E.B., A.K. and Z.B.; supervision, A.K. and D.K.; project administration, E.B. and A.K.; funding acquisition, E.B. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Project no. 993788 was implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the KDP-2020 funding scheme. This research was supported by the Hungarian National Scientific Research Fund (NKFIH FK-146600), the National Multidisciplinary Laboratory for Climate Change, RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00014 project, and the TKP2021-NVA-29 project of the Hungarian National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, with support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary.

Data Availability Statement

Data beyond satellite imagery are not generally available to the public. However, it is possible to obtain data for research purposes on individual basis. In case of interest please send your inquiry to fok@lechnerkozpont.hu.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dóra Neidert for providing the harvest-derived precision yield data and for her valuable advice throughout our work. We are particularly grateful to the Ministry of Agriculture for operating the AMSR and supporting our research. We are also grateful to the National Food Chain Safety Authority for providing us with anonymous damage claim data, as well as to the Space Remote Sensing Department of the Lechner Knowledge Centre for their collaboration in producing the background material used in this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ranum, P.; Peña-Rosas, J.P.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Global Maize Production, Utilization, and Consumption. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1312, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakir, R. Effect of Water Stress at Different Development Stages on Vegetative and Reproductive Growth of Corn. Field Crops Res. 2004, 89, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobell, D.B.; Gourdji, S.M. The Influence of Climate Change on Global Crop Productivity. Plant Physiol. 2012, 160, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, A.; Barcza, Z.; Marjanović, H.; Árendás, T.; Fodor, N.; Bónis, P.; Bognár, P.; Lichtenberger, J. Statistical Modelling of Crop Yield in Central Europe Using Climate Data and Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2018, 260–261, 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Azzari, G.; You, C.; Di Tommaso, S.; Aston, S.; Burke, M.; Lobell, D.B. Smallholder Maize Area and Yield Mapping at National Scales with Google Earth Engine. Remote Sens. Environ. 2019, 228, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueechi, E.; Fischer, M.; Crocetti, L.; Trnka, M.; Grlj, A.; Zappa, L.; Dorigo, W. Crop Yield Anomaly Forecasting in the Pannonian Basin Using Gradient Boosting and Its Performance in Years of Severe Drought. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2023, 340, 109596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žalud, Z.; Hlavinka, P.; Prokeš, K.; Semerádová, D.; Jan, B.; Trnka, M. Impacts of Water Availability and Drought on Maize Yield—A Comparison of 16 Indicators. Agric. Water Manag. 2017, 188, 126–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinke, Z.; Lövei, G.L. Increasing Temperature Cuts Back Crop Yields in Hungary over the Last 90 Years. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2017, 23, 5426–5435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viña, A.; Gitelson, A.A.; Rundquist, D.C.; Keydan, G.; Leavitt, B.; Schepers, J. Monitoring Maize (Zea mays L.) Phenology with Remote Sensing. Agron. J. 2004, 96, 1139–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, J.F.; Schepers, J.S.; Francis, D.D.; Varvel, G.E.; Wilhelm, W.W.; Tringe, J.M.; Schlemmer, M.R.; Major, D.J. Use of Remote-Sensing Imagery to Estimate Corn Grain Yield. Agron. J. 2001, 93, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, P.; Ferencz, C.; Pásztor, S.; Molnár, G.; Timár, G.; Hamar, D.; Lichtenberger, J.; Székely, B.; Steinbach, P.; Ferencz, O.E. Yield Forecasting for Wheat and Corn in Hungary by Satellite Remote Sensing. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2011, 32, 4759–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maestrini, B.; Basso, B. Predicting Spatial Patterns of Within-Field Crop Yield Variability. Field Crops Res. 2018, 219, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayad, A.; Sozzi, M.; Gatto, S.; Marinello, F.; Pirotti, F. Monitoring Within-Field Variability of Corn Yield Using Sentinel-2 and Machine Learning Techniques. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Řezník, T.; Pavelka, T.; Herman, L.; Lukas, V.; Širůček, P.; Leitgeb, Š.; Leitner, F. Prediction of Yield Productivity Zones from Landsat 8 and Sentinel-2A/B and Their Evaluation Using Farm Machinery Measurements. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, A.; Adeniyi, O.D.; Tamás, J.; Nagy, A. Assessment of a Yield Prediction Method Based on Time Series Landsat 8 Data. Acta Hortic. Regiotect. 2021, 24, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radočaj, D.; Šiljeg, A.; Marinović, R.; Jurišić, M. State of Major Vegetation Indices in Precision Agriculture Studies Indexed in Web of Science: A Review. Agriculture 2023, 13, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soccolini, A.; Vizzari, M. Predictive Modelling of Maize Yield Using Sentinel 2 NDVI. In Computational Science and Its Applications—ICCSA 2023 Workshops; Gervasi, O., Murgante, B., Rocha, A.M.A.C., Garau, C., Scorza, F., Karaca, Y., Torre, C.M., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; Volume 14107, pp. 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamás, A.; Kovács, E.; Horváth, É.; Juhász, C.; Radócz, L.; Rátonyi, T.; Ragán, P. Assessment of NDVI Dynamics of Maize (Zea mays L.) and Its Relation to Grain Yield in a Polyfactorial Experiment Based on Remote Sensing. Agriculture 2023, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, L.; Kemény, G. Complex Agricultural Risk Management System: A New Information System Supporting the Claim Adjustment Process in the Hungarian Agriculture. J. Agric. Inform. 2014, 5, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Áldorfai, G.; Hámori, J.; Keszthelyi, S.; Kovaĉ, A.R.; Péter, K.; Szili, V. A Mezőgazdasági Kockázatkezelési Rendszer Működésének Értékelése 2022, 2023rd ed.; AKI Agrárközgazdasági Intézet Nonprofit Kft.: Budapest, Hungary, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Várallyay, G.; Szűcs, L.; Murányi, A.; Rajkai, K.; Zilahy, P. Map of Soil Factors Determining the Agro-Ecological Potential of Hungary (1:100,000) II. Agrokem. Talajt. 1980, 29, 35–76. [Google Scholar]

- Henits, L.; Szerletics, Á.; Szokol, D.; Szlovák, G.; Gojdár, E.; Zlinszky, A. Sentinel-2 Enables Nationwide Monitoring of Single Area Payment Scheme and Greening Agricultural Subsidies in Hungary. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinyi, E.; Kristóf, D.; Kern, A.; Rotterné Kulcsár, A.; Barcza, Z. A Mezőgazdasági Kockázatkezelési Rendszerbe benyújtott aszály kárigények nagyfelbontású műholdfelvételekkel történő igazolhatóságának vizsgálata—Kezdeti lépések. In Tavaszi Szél 2022/Spring Wind 2022 Tanulmánykötet I; Doktoranduszok Országsi Szövetsége: Budapest, Hungary, 2022; pp. 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, J.; Su, B. Significant Remote Sensing Vegetation Indices: A Review of Developments and Applications. J. Sens. 2017, 2017, 1353691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Wardlow, B.D.; Xiang, D.; Hu, S.; Li, D. A Review of Vegetation Phenological Metrics Extraction Using Time-Series, Multispectral Satellite Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2020, 237, 111511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouse, J.W., Jr.; Haas, R.H.; Schell, J.A.; Deering, D.W. Monitoring Vegetation Systems in the Great Plains with Erts. NASA Spec. Publ. 1974, 351, 309. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Huang, J.; Jackson, T.J. Vegetation Water Content Estimation for Corn and Soybeans Using Spectral Indices Derived from MODIS Near- and Short-Wave Infrared Bands. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 98, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.; Wylie, B.K.; Howard, D.M.; Phuyal, K.P.; Ji, L. NDVI Saturation Adjustment: A New Approach for Improving Cropland Performance Estimates in the Greater Platte River Basin, USA. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Gitelson, A.A.; Sakamoto, T. Remote Estimation of Gross Primary Productivity in Crops Using MODIS 250 m Data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2013, 128, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, N.T.; Chen, C.F.; Chen, C.R.; Minh, V.Q.; Trung, N.H. A Comparative Analysis of Multitemporal MODIS EVI and NDVI Data for Large-Scale Rice Yield Estimation. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2014, 197, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Didan, K.; Miura, T.; Rodriguez, E.P.; Gao, X.; Ferreira, L.G. Overview of the Radiometric and Biophysical Performance of the MODIS Vegetation Indices. Remote Sens. Environ. 2002, 83, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huete, A.; Justice, C.; Liu, H. Development of Vegetation and Soil Indices for MODIS-EOS. Remote Sens. Environ. 1994, 49, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camps-Valls, G.; Campos-Taberner, M.; Moreno-Martínez, Á.; Walther, S.; Duveiller, G.; Cescatti, A.; Mahecha, M.D.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; García-Haro, F.J.; Guanter, L.; et al. A Unified Vegetation Index for Quantifying the Terrestrial Biosphere. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabc7447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Moreno-Martínez, Á.; Muñoz-Marí, J.; Campos-Taberner, M.; Camps-Valls, G. Estimation of Vegetation Traits with Kernel NDVI. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 195, 408–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B. NDWI—A Normalized Difference Water Index for Remote Sensing of Vegetation Liquid Water from Space. Remote Sens. Environ. 1996, 58, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merzlyak, M.N.; Gitelson, A.A.; Chivkunova, O.B.; Rakitin, V.Y. Non-destructive Optical Detection of Pigment Changes during Leaf Senescence and Fruit Ripening. Physiol. Plant. 1999, 106, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogan, F.N. Remote Sensing of Weather Impacts on Vegetation in Non-Homogeneous Areas. Int. J. Remote Sens. 1990, 11, 1405–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, L.; Xie, B.; Zhou, J.; Li, C. Comparative Evaluation of Drought Indices for Monitoring Drought Based on Remote Sensing Data. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 20408–20425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belal, A.-A.; El-Ramady, H.R.; Mohamed, E.S.; Saleh, A.M. Drought Risk Assessment Using Remote Sensing and GIS Techniques. Arab. J. Geosci. 2014, 7, 35–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nádor, G.; Birinyi, E.; Pacskó, V.; Friedl, Z.; Kulcsár, A.R.; Hubik, I.; Gera, D.; Surek, G. Country Wide Grassland Mapping by Fusion of Optical and Radar Time Series Data [Poster Presentation]; Chania: Crete, Greece, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Cloude, S.R.; Pottier, E. An Entropy Based Classification Scheme for Land Applications of Polarimetric SAR. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 1997, 35, 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacskó, V.; Belényesi, M.; Barcza, Z. Vetésszerkezeti térképek idősorának kategóriánkénti pontosságvizsgálata. In Az Elmélet És Gyakorlat Találkozása a Térinformatikában XIV; Debreceni Egyetemi Kiadó: Debrecen, Hungary, 2023; pp. 191–198. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick, N.; Hancher, M.; Dixon, M.; Ilyushchenko, S.; Thau, D.; Moore, R. Google Earth Engine: Planetary-Scale Geospatial Analysis for Everyone. Remote Sens. Environ. 2017, 202, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HCSO. Hungarian Central Statistical Office: A Kukorica Termelése Vármegye és Régió Szerint. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/stadat_files/mez/hu/mez0072.html (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Breiman, L. Random Forest. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]