1. Introduction

The changing land use/land cover (LULC) exerts impacts on terrestrial environment, climate conditions and biosphere, and more dramatically, human social environment [

1]. Land use change is an essential factor for different natural and social elements such as ecological service [

2], hydrological characteristic [

3], and urban expansion [

4,

5]. Detecting and analyzing accurate, historical, and continual land use change are essential for land resource management, which is recognized as a measure to better understand and solve socioeconomic and environmental problems [

6,

7].

Applications of detecting historical LULC change have developed with the advances in Earth observation technologies. Preceding data were interpreted artificially from images taken by satellite and complementary field-based observations [

8]. In general, to save time and material cost, remote sensing technologies are commonly applied in monitoring LULC changes [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. This has promoted the development of diverse LULC data products. Nowadays, open global aerospace databases like MODIS and GLOBALLAND 30 product are also in common use for the analysis of LULC dynamics and climate change [

15].

The land use situation in Japan is special. Japan is a country with a relatively small land area, a high population density, and general lack of land resources (

www.mlit.go.jp (accessed on: 24 April 2020)) [

16]. With the gradual intensification of the economy and a large population base, the contradiction between the land demand requirement and the limited space in the country has become increasingly prominent. However, this is different from some developing countries only experiencing a remarkably big urban expansion because Japan is also experiencing a decreasing population trend. The impact of this trend on human activities is relatively larger in rural areas because of the scant population base and less foreign population in rural areas, and this difference will deepen the imbalance of land use development between rural and urban areas in Japan [

17]. These facts have caused a series of socioeconomical problems, such as the rising land and house prices in metropolis and abandoned farmland in remote areas [

16,

18]. Therefore, an analysis of the LULC dynamics in Japan is a basic step for understanding and solving these problems caused by land scarcity.

Japan also made considerable efforts on LULC change detection. The Geospatial Information Authority (GSI) of Japan has released a 1000 m resolution dataset of land cover across Japan on a year interval basis, which was synthesized from survey-based topographic maps and satellite images. The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) has produced 30 m (in 2006–2011) and 10 m (in 2014–2016) resolution land cover maps of Japan with 10 land cover types by using its multi-temporal optical data and survey results from GSI [

19]. In addition, the Biodiversity Center of Japan (BCJ) has monitored surface vegetation cover with an extremely high resolution (5 m) and thorough surface distribution of plant species [

20]. These data sets also provide valid land use references in Hokkaido on a specific time or period, which can act as the basis for general land use analysis, but their medium spatial and temporal resolutions and fixed classified LULC types are insufficient for long-term LULC monitoring and accurate land use dynamic analysis [

10,

12,

21,

22].

Classification is an indispensable LULC mapping procedure, which associates pixel values to LULC categories present on the ground [

12]. Pixel-based classification methods can be grouped into supervised classification and unsupervised classification. The former defines special land cover types by using training samples drawn from images, which delegate a cluster of spectral value. Unsupervised methods do not need training data, but classify pixels based on different spectral classes [

11]. During those processes, spectral index such as normalized vegetation index (NDVI), normalized difference built-up index (NDBI), and digital elevation model (DEM) are effectively used in characterize typical land cover categories [

23].

Meanwhile, researchers and policymakers recently have paid more attention to assessing land use change and project future landscape patterns [

24,

25]. Land use change simulation is an indispensable aspect in LULC studies, due to its important role in analyzing the causes, changes, and environmental effects of land use changes and guiding future scientific and feasible land use planning [

25,

26]. Previous studies on land use change simulation varies from application level to technology advancement level. Liang, et al. used a CA-based model to simulate the urban expansion in the southern cities of China. Dynamic of land system model has been applied in exploring future land use distribution in Punjab province (Pakistan) in an Environmental Sustainability Scenario [

27]. Also, Feng et al. have compared the different land use simulation effects of three metaheuristic methods on a case study of Yangtze River Delta [

28]. Ralha et al. developed a multi-agent model system to represent land use change dynamics, which is important for policymakers to analyze different scenarios when making decisions [

29].

Land use change simulation models are useful tools to analyze the causes and results of land use changes, which can explore in depth the mechanisms of land use systems [

30]. They are mainly divided into two categories. One is the models used to simulate the changes in land use type area over time, such as regression analysis models, Markov models, and system dynamics models [

31,

32,

33]. Another is to simulate the spatial distribution of land use, including the land change modeler (LCM) model, The conversion of land use and its effects (CLUE) model, cellular automata (CA) model and future land use simulation (FLUS) model, etc. [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Based on the causal relationship between past land use change and related driving force factors, they compute the land use demand and distribution probability, for the aim of simulating future spatiotemporal land use under targeted scenarios [

38,

39,

40].

The FLUS is a model for simulating land use changes and future land use scenarios under the influence of human activities and nature. It has strong temporal and spatial dynamic simulation capabilities [

34]. Compared with the traditional CA-based models which need to sample from the changes between the two periods of land use data, this model samples from only the most recent period, which can handle non-linear relationships more effectively by avoiding error transmission. In addition, the FLUS model proposes an adaptive inertial competition mechanism based on roulette selection, which can advantage the demonstration of uncertainty and complexity of the mutual transformation of multiple land use types under the joint influence of natural and human activities.

Hokkaido is the 21st biggest island in the world and second largest in Japan, accounting for 22.4% of the national territory. Unlike other relatively “central” places in Japan which are famous for their manufacturing industry, Hokkaido shows an agriculture industry predominance. The arable land area of Hokkaido accounts for 26.0% of the total arable land in Japan, and its per capita area is 2.17 ha, still ranking at the top in Japan. Besides, the agricultural economic output of Hokkaido was 13.8% of the national total and its calorie-based food self-sufficiency rate is 206%, which means Hokkaido is the veritable food base of Japan [

41]. The status of agriculture in Hokkaido will probably affect land use dynamics, and the improvement of agricultural techniques and less population would make this change more complicated.

On the other hand, Hokkaido is significant for its protected areas. There are 11 national parks, 12 prefectural parks, two UNESCO global geo-parks, five national geoparks, and 13 wetlands listed in Ramsar Convention and one World Natural Heritage site in Hokkaido (uu-hokkaido.com (accessed on: 12 March 2021)). These protected areas have considerable ecological and sightseeing value, but simultaneously, might have an impact on future Hokkaido land use patterns. Therefore, it is necessary to figure out the past-to-future land use dynamics of Hokkaido for better understand the land use situation and make optimal governmental decisions about future land use patterns.

Recently less research has been conducted on the entire island of Hokkaido’s land use analysis and simulation, possibly due to the large extent of study area and the shortage of data. By using remote sensing tools and a land use simulation model, this study can give fundamental insights into the land use dynamics of Hokkaido. Therefore, the objectives of this study are: (1) to understand the recent spatiotemporal dynamics of land use in Hokkaido by mapping the land use classification in 2000, 2010, 2019, respectively, and (2) to simulate the scenario-based future land use maps in 2040 using an auto-improved FLUS model.

2. Study Area and Data

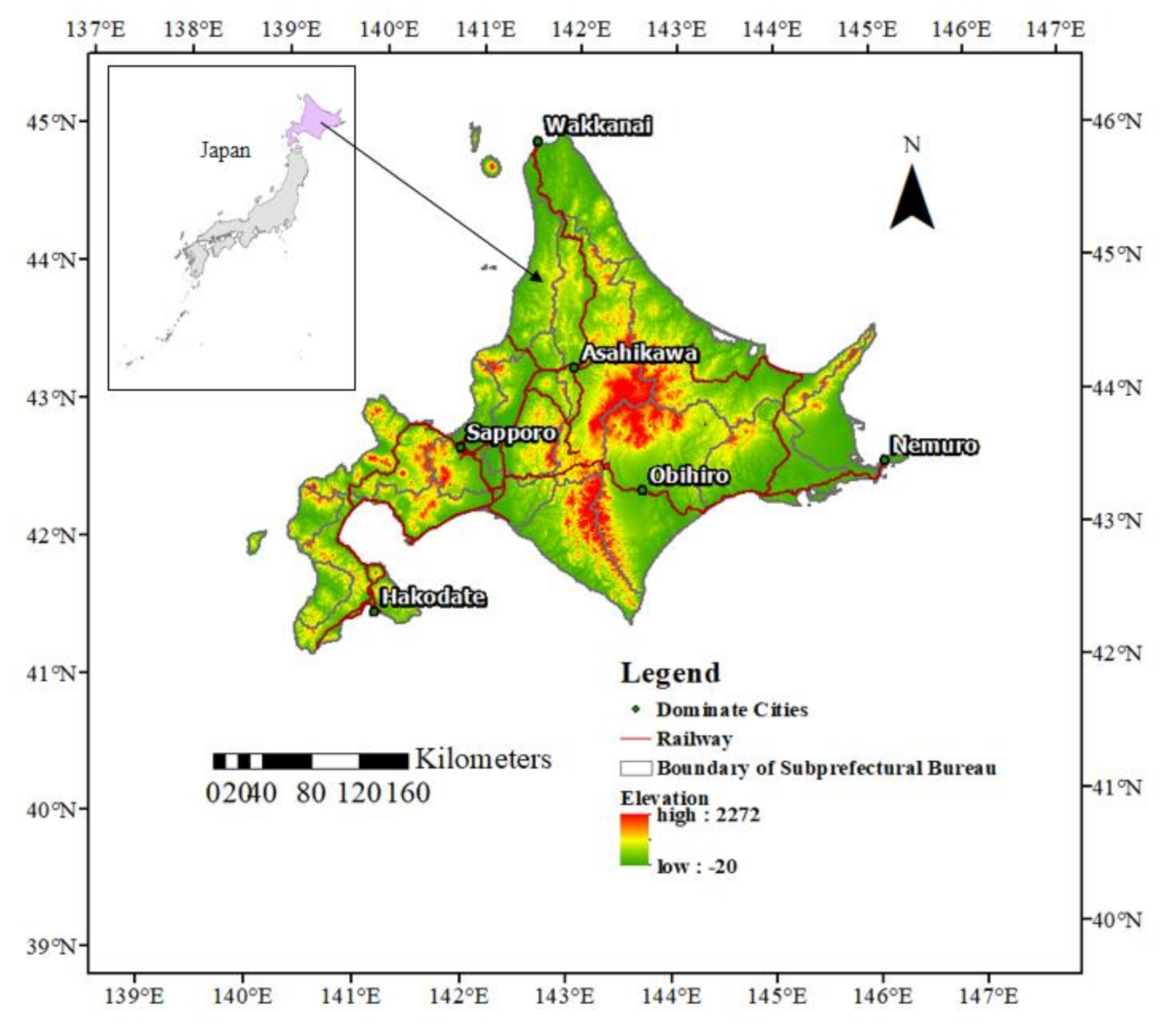

Hokkaido is located at the north of Japan (

Figure 1), covering the area of about 8.3×10

4 km

2 (excluding controversial territory). Geographically it lies in 40°33′N to 45°33′N and 139°20′E to 148°53′E. The elevation ranges from −20 m to 2272 m. Hokkaido is the only one administrative unit called “do” among 47 prefectures in Japan. In subunits, there are 14 subprefectural bureaus, which consist of 64 counties, 35 cities, 129 towns, and 15 villages. The terrain of Hokkaido is high in altitude in its center and relatively low in altitude at all sides near the coast. Mountainous areas account for 60% of the total land, and 40% of this area is occupied by volcanos.

On January 1st in 2019, the population of Hokkaido was 5,268,352 and nearly half of is was living in Sapporo, the capital city of Hokkaido. The rest are mostly distributed in other central cities of subprefectural bureaus such as Hakodate, Obihiro and Asahikawa. The age structure of Hokkaido’s population is characterized by a serious old-aging trend. People over 65 years old account for nearly 40% of Hokkaido’s population.

Meanwhile, the negative natural growth rate of Hokkaido has led to a decreasing total population trend in recent years and future predictions (Hokkaido Population Vision, 2020). The National Institute of Population and Social Security Research (NIPSSR) conducted a population prediction showing the Hokkaido population is expected to drop by nearly 1/5 by 2040 (

Figure 2).

Hokkaido is also one of Japan’s main forest lands, and its forests account for about 22% of Japan’s total forested area. The national forests of Hokkaido account for more than 50% of the total forest area of Hokkaido, including Mt. Daisetsu, the Hidaka Mountain and other major mountain ranges, creating one of the richest ecosystems in Hokkaido. The national forest of Hokkaido consists of conifers (Sakhalin fir and Sakhalin spruce) and broadleaf trees (Japanese oak, birch, and painted maple), whose views change with the seasons. The Hokkaido Regional Forest Office classifies national forests into four of five types depending on their main functions to conduct appropriate managements: water resource conservation type; landslide prevention type; recreational use type and nature conservation type [

42].

Satellite images are downloaded from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) website at a resolution of 30 m, including Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM) data, Landsat Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) data and Landsat Operational Land Imager (OLI) data. To reduce the missing information caused by snow cover, for each year, images in warm seasons (from 1 May to 31 October) were integrated at each pixel position over time by taking the median. Detailed information is shown in

Table 1.

Considering the territory dispute between Japan and Russia regarding the boundaries of Hokkaido (the four northern islands), the administrative shape file in the disputed areas was excluded to fit the subsequent driving force analysis. Therefore, the Hokkaido vector files were not obtained from the Japanese government GSI but rather from the DIVA-GIS website (

www.diva-gis.org (accessed on: 12 September 2020)) which removes the above disputed islands from Hokkaido domain.

The change of land use is the result of the combined effect of natural factors and socio-economic factors, static and dynamic. Therefore, the selected factors should adhere to both natural factors and socio-economic factors to achieve a more accurate simulation of land use change. The selection of driving factors for land use change mainly conforms to the following four principles: (1) accessibility of factor data, which is a key issue for driving factor research and a guarantee for the accurate operation of related models; (2) consistency of factor data: The data should be consistent in time and space; (3) factor quantification, which can be input into the model, and simulation prediction can be realized; and (4) comprehensiveness of factor selection [

43]. Based on this, seven land use change factors were selected, including digital elevation model (DEM), slope, distance to road (DTROAD), distance to railway (DTRAIL), organic carbon in topsoil (TOC), and bulk density in topsoil (TBD), population density (PD). In addition, a protected area of national parks from GSI are displayed as a policy refrain on land use change. The detailed descriptions of each factor are illustrated in

Table 2:

The administration-based masked raster files of land use driving factors were processed at unified resolution at 150 m due to the model calculator ability, as shown in

Figure 3.

5. Discussion

5.1. Past-to-Future Land Use Pattern (2000–2040)

Figure 9 indicates area changes of 6 land use classes in Hokkaido from 2000 to 2040. The period between 2000 and 2019 is based on the classification results, and the amounts in 2040 are derived from simulation results in ND scenario.

The results of this study show that Hokkaido has had a significant decline in cultivated land in the past and will the decline will continue in the next 20 years, while the area of grassland will have a clear upward trend. This shows that during the period, the abandonment of cultivated land will become more serious. According to the simulation analysis based on the driving factor, the abandoned farmland will be converted into grassland (in this case, abandoned area) to a large extent, and part of it will be occupied by construction, which is consistent with the trend reflected in both

Table 6 and

Table 7 and

Figure 9.

The abandonment of farmland in Hokkaido has become an issue affecting the sustainability of land use since the last 1980s [

50], which is a direct reflection of the future reduction of cultivated land in Hokkaido. Previous studies have shown that the main factors for the abandonment of farmland in Hokkaido include natural and social factors: natural factors consist of geographic location, slope and elevation, soil quality, while social factors mainly include policy and demographic changes. It is worth mentioning that the impact of policies on farmland abandonment can be two contrast ways. For instance, the “Hokkaido Comprehensive Development Plan (HCDP)” aims to promote the relocation, concentration, and intensification of farmland, and to increase agricultural productivity and farmers’ income [

49], which encourages to abandoned barren and hard-to-use farmland. However, the “Direct Payment (DP) system” in Hokkaido slowed down the growth rate of abandoned farmland through financial subsidies to farmers [

51]. Therefore, to maximize the sustainability of cultivated land use in Hokkaido, this study did not simulate the impact of certain policies. Instead, it directs the effects that policy can make, that is, to minimize the abandonment of cultivated land to construct CP scenario.

The demographic changes in Hokkaido will also have an impact on the abandonment of farmland. The results of logistic regression analysis in this study show that population density and the distribution of cultivated land are negatively correlated, which means that the more concentrated the population is in urban areas, the lower the probability of cultivated land. According to the government’s employment statistics (

www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp (accessed on: 15 December 2020)) from 2000 to 2019, the proportion of people engaged in farming in Hokkaido has decreased and the number of farmers over 65 years old has consistently risen, while the urbanized population is increasing, and it can be claimed that the increase of urban population will promote the expansion of the urban construction [

52,

53,

54]. This is consistent with the results of the decrease of cultivated land in

Figure 8a and the increase of construction in

Figure 8e.

Compared with the area changes of other land use types, waterbody and others did not change significantly from 2000 to 2019 and are not estimated to change much in the future. For waterbody, the changes in this stage are likely to be caused by the classification error of the cultivated land, especially in areas with paddy fields, which occurs frequently in the Ishikari Plain. As far as others, the main reason for its low accuracy is the uncertainty of snow distribution on the surface. Except for some high-altitude mountains, most of the snow-covered areas have a great relationship with the climatic conditions of the target year.

5.2. Comparison of Scenario-Based Land Use Situations

As the area of cultivated land in Hokkaido has a clear downward trend in the context of natural development (ND), This study achieves the sustainable use of cultivated land by restricting the transfer of cultivated land to other land (

Table 12). The area of cultivated land obtained in ND scenario is compared with the CP scenario and the FP scenario, respectively. An increase of about 25% in cultivated land in CP scenario indicates that the policy of protecting cultivated land can effectively improve the sustainable use of cultivated land. In addition, the amount and spatial distribution of cultivated land use in 2019 are almost the same as in the CP scenario, which shows that the demand for cultivated land in Hokkaido has been basically saturated, and it may only remain unchanged or decrease in the future.

By comparing the ND scenario and the CP scenario, we can summarize the spatial change trends of the cultivated land in the two scenarios in the future, mainly showing the following three points. Firstly, in the ND scenario, the cultivated land is more likely to be converted into forest, grassland, or construction due to the concentration of agriculture. This includes the expansion of forest land from the center to the surrounding area and the increase of scattered buildings (

Table 13 and

Figure 10a,e and

Figure 10b,f). Secondly in CP scenario, the cultivated land at the edge location has been effectively protected, resulting in a slowdown in the rate of cultivated land abandonment (

Figure 10c,g). (3) Grassland tends to be transformed into forest land under the ND scenario and be transformed into cultivated land or maintained under the CP scenario (

Figure 10d,h).

Due to the important position of forest land on Hokkaido, this study explored the possible changes of forest land in the future by constructing FP protection scenarios. In CP scenario, a reduction of 1310 km

2 was found in the forest compared to the ND scenario (

Figure 11), while in FP scenario, the forest has increased by 509.7 km

2 compared to the ND scenario (

Figure 12). The increase in forest land is mainly due to the conversion from abandoned farmland and the slowing down of grassland expansion, especially in mass graze-based grassland in east of Hokkaido (

Figure 13a,c and

Figure 13b,d).

5.3. Recommendations and Suggestions

Based on the comparative analysis of the characteristics of land use evolution, existing problems, and multi-scenario simulation results in this study, the following suggestions are put forward for the optimization and adjustment of future land use in Hokkaido: (1) Our results show that restricting land use areas can effectively enhance the sustainable use of cultivated land. Therefore, it is advisable to strengthen the protection of cultivated land, by regulating a basic cultivated land protection system and compensation system (such as Direct Payment) should be established to ensure the balance of cultivated land occupation and its quality. (2) Promote the transformation of government functions by strengthening land regulation and supervision, meanwhile restrict the trading of private cultivated land in Hokkaido. Public funds should be used to restore the use of abandoned arable land, and at the same time, through agricultural technology, to ensure that Hokkaido’s food production continues to meet the minimum standards of national food security. (3) The results show a mass area of grassland replacing cultivated land in the future. Hence, by centralizing grazing activities, the expansion of Hokkaido’s grassland into cultivated land and forest can be effectively restrained, especially at the boundaries between grassland and these lands. Simultaneously, the unused grassland converted from abandoned farmland should be conserved to ensure that its fertility is capable of being converted back into cultivated land in the future. (4) From the regression results, this study concludes intensive population in urban area is not beneficial to the development of cultivated land. Consequently, controlling the concentration of population in Hokkaido cities and encouraging people to relocate to the non-central areas is necessary for cultivated land protection. By improving transportation, medical care, education and other functions, the population distribution of Hokkaido can be dispersed.

The fifth basic land use plan (

www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp (accessed on: 22 May 2021)) of Hokkaido stipulates that the cultivated land in the basic farming area cannot be used for other purposes, which fits well with recommendations 1 and 2. The existing farmland will be protected to the maximum extent, and the fertile but abandoned cultivated land will be protected and appropriately improved. For cultivated land in non-agricultural areas, where adjustments are expected to conduct non-agricultural land use planning (such as urban planning), stakeholders will follow the adjusted planning older which is used to define the “Good Cultivated Land” or not, and this “Good Cultivated Land” will be properly preserved. However, the criteria for formulating this order are multifaceted, not only related to the land itself, but also to its geographic location and the attitude of the owner, which complicates the protection of cultivated land outside of agricultural areas. Policymakers are supposed to clearly define what is “Good Cultivated Land” but not depend on an obscure consultation with landlord.

5.4. Limitations and Future Works

In general, some shortcomings of the study can be concluded based on the following four points:

(1) The remote sensing data for making land use classification are at a resolution of 30 m and the simulation process is at a resolution of 150 m, which indicates there are still some details requiring more accurate interpretation. (2) The classifications of cultivated and waterbody, cultivated land and grassland without considering the phenological law, are more likely to be confused. Moreover, due to the large area of Hokkaido, it is difficult to collect training sample sets based on field surveys, resulting in certain classification errors. (3) Driving factors have relatively limited impact on land use, and different types of driving factor weights cannot be assigned, that is, the influence weights of factors on land use cannot be grasped well. (4) Moreover, scenarios differ from absolute restricted area, but the actual situation is hard to develop towards these directions.

Accordingly, further studies are supposed to include the below solutions: (1) use of relatively high resolution satellite data to optimize land use classification process if it is technically and economically feasible; (2) to investigate the phenological laws of various vegetation types, especially paddy rice in cultivated land, for improving the classification accuracy; (3) to use appropriate weight analysis methods to rank the influence of land use driving factors; (4) to collect policy documents to support the establishment of target future land use scenarios.

6. Conclusions

This research used remote sensing classification methods based on a random forest algorithm to monitor the spatiotemporal changes in six land classes (cultivated land, forest, waterbody, construction, grassland, and others) on Hokkaido from 2000 to 2019, with an overall accuracy of classification over 88%. Based on the analysis of land use changes and driving factors including DEM, slope, PD, DTRAIL, DTROAD, TOC, TBD and autocorrelation factors added to improve simulation accuracy, the coupled Markov-FLUS model is applied by changing the restricted area to simulate spatial distributions of land use in natural development scenario, cultivated land protection scenario, and forest protection situation of Hokkaido in 2040. The land use classification results show from the period of 2000 to 2019, the area of cultivated land in Hokkaido shows a downward trend with a reduction of 642.1 km2, while construction has increased by 111.0 km2 and grassland expanded by 2179.4 km2, while the forest and waterbody areas have not changed significantly. The simulation results of future land use changes show that under the natural development scenario, the cultivated land in Hokkaido will be reduced by about 25% by 2040, and the reduced cultivated land is more likely to be converted into grassland and forest land. In the cultivated land protection scenario, the area of cultivated land remains basically unchanged, which shows that the use of cultivated land in Hokkaido has reached saturation, and about 239.0 km2 forest land will be invaded by other land types. In forest protection scenario, the area of forest in Hokkaido will increased by around 1580.8 km2, but the change trend of cultivated land is following natural development scenario. Grassland, especially in mass intensive graze-based area of eastern Hokkaido, will have an obvious expansion trend. This study provides a reference for future land use planning and management in Hokkaido, and it is expected to support the sustainable land use development with different targets.