Remote Sensing of Human–Environment Interactions in Global Change Research: A Review of Advances, Challenges and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

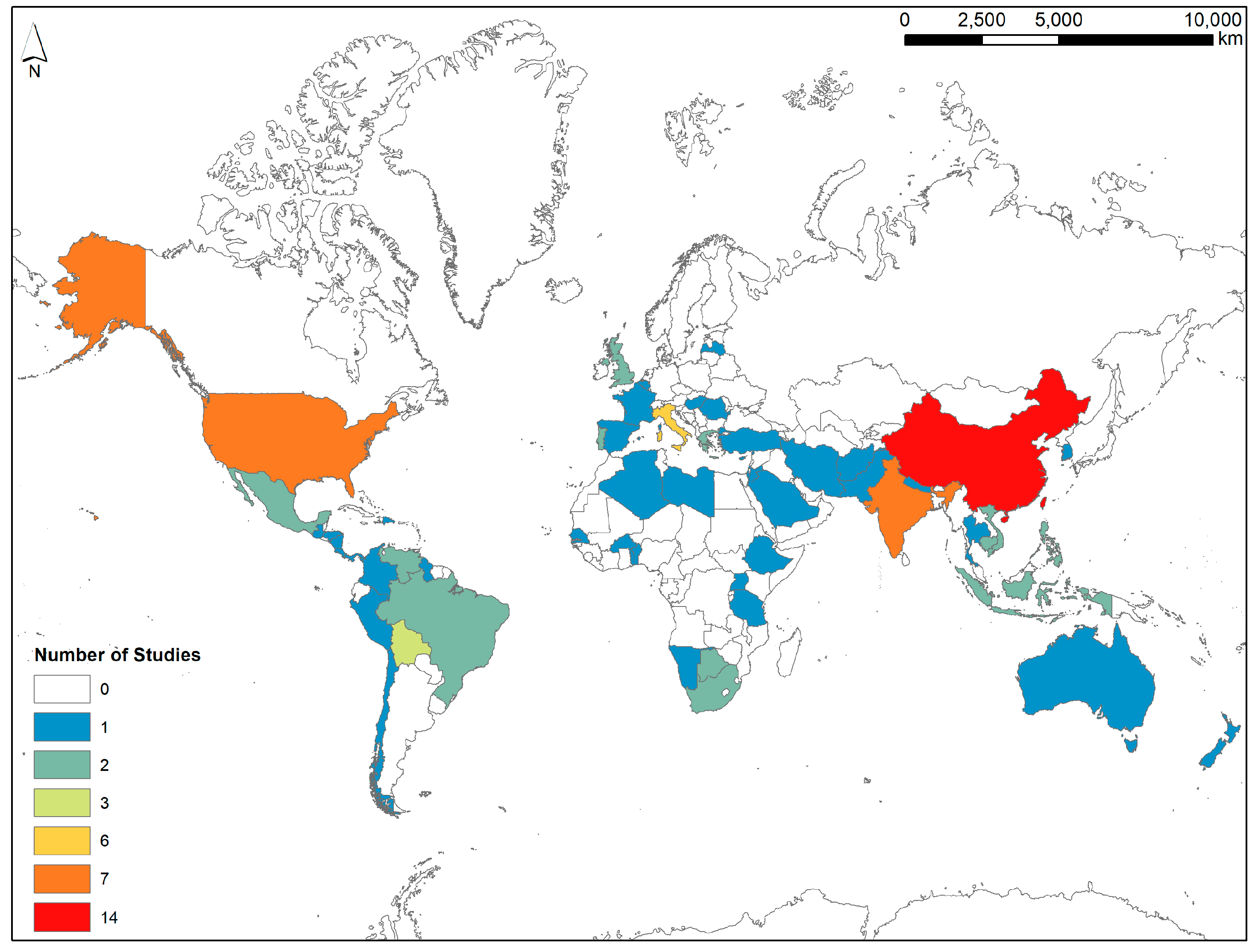

2. Literature Search Strategy

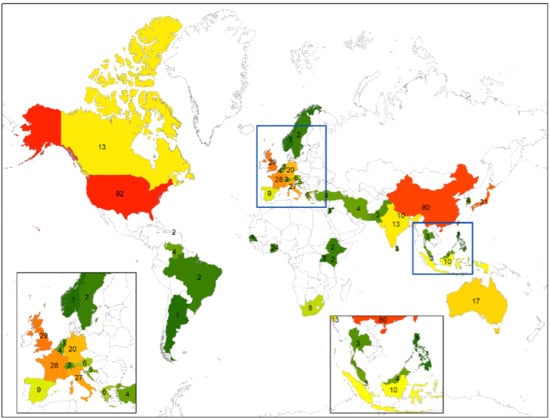

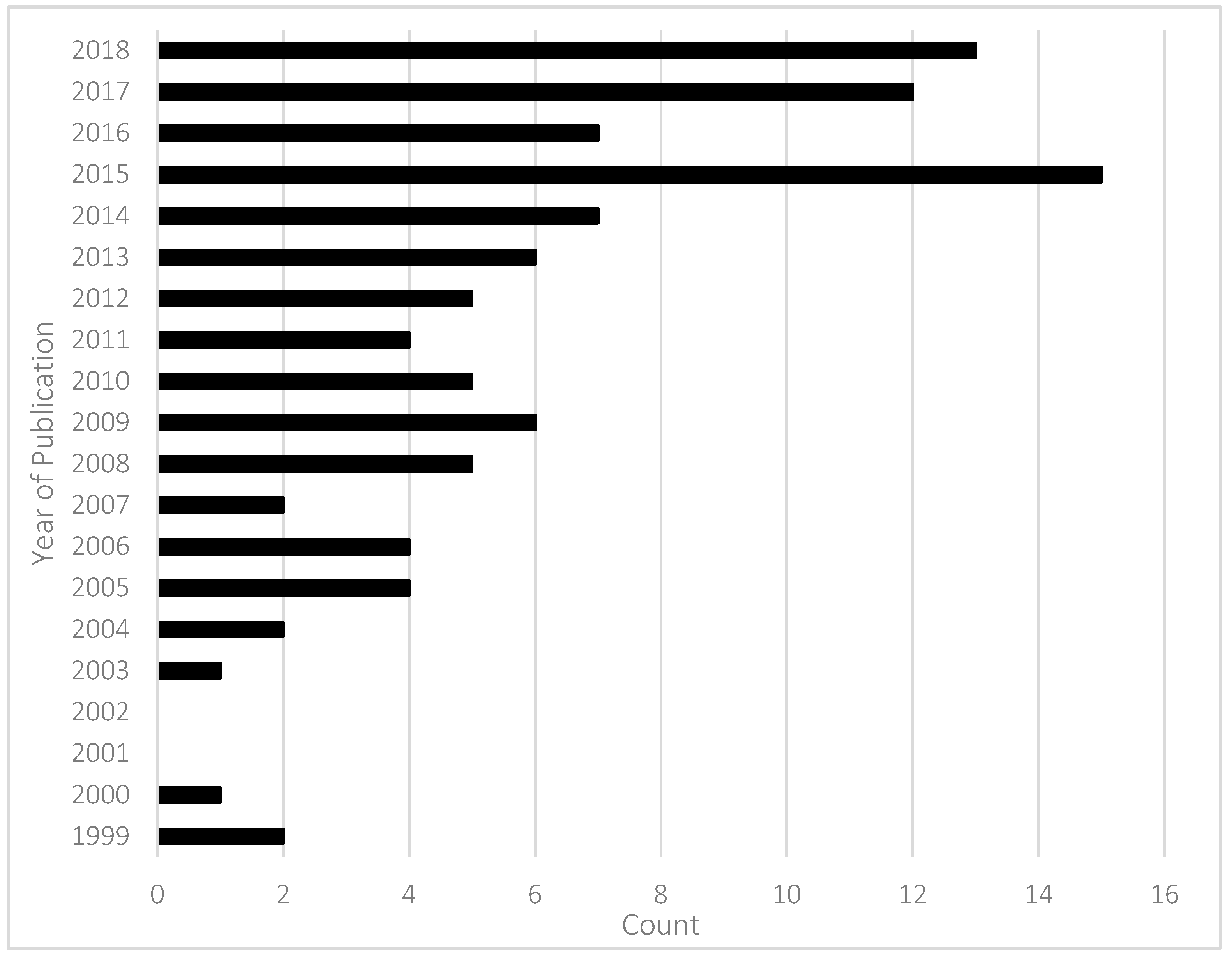

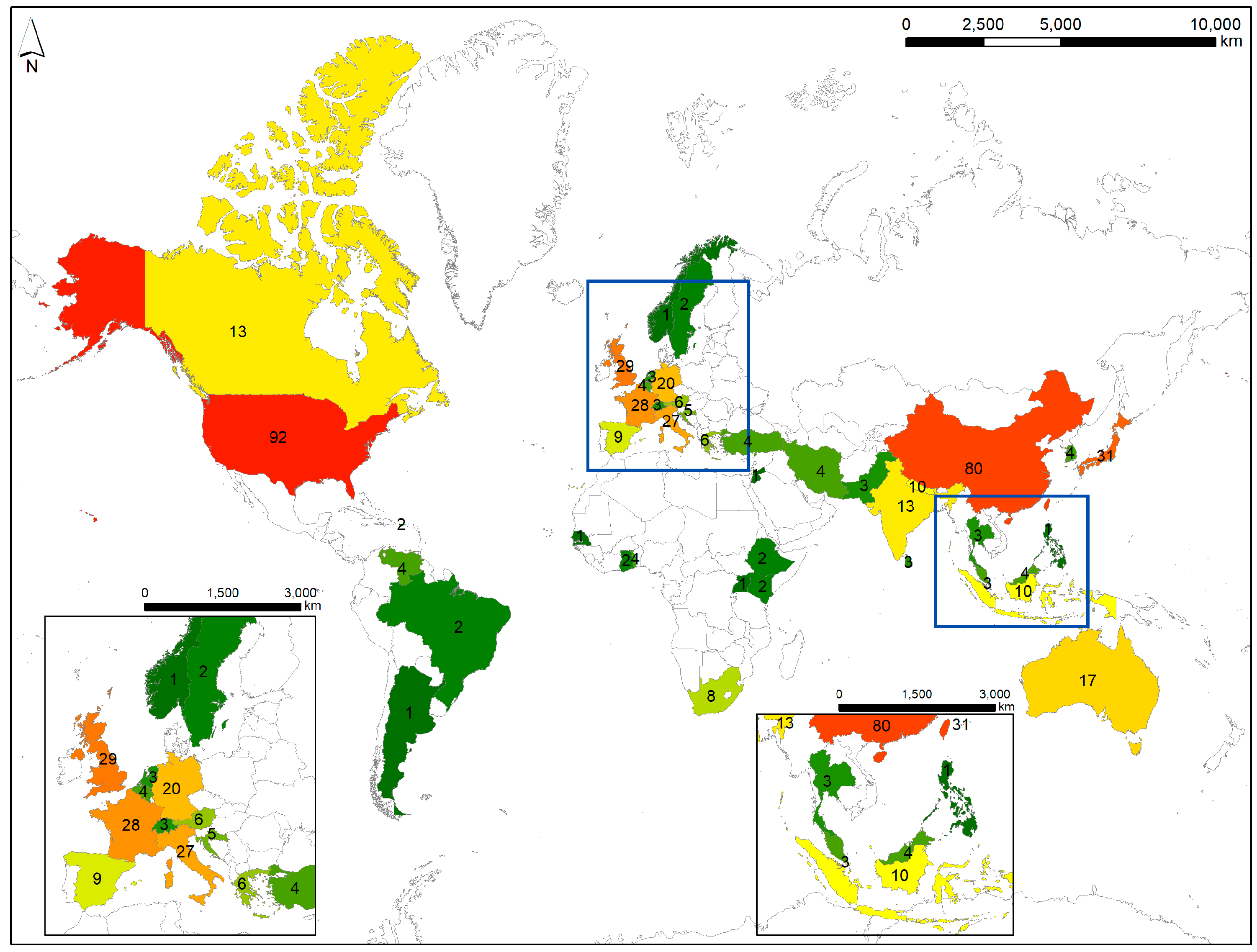

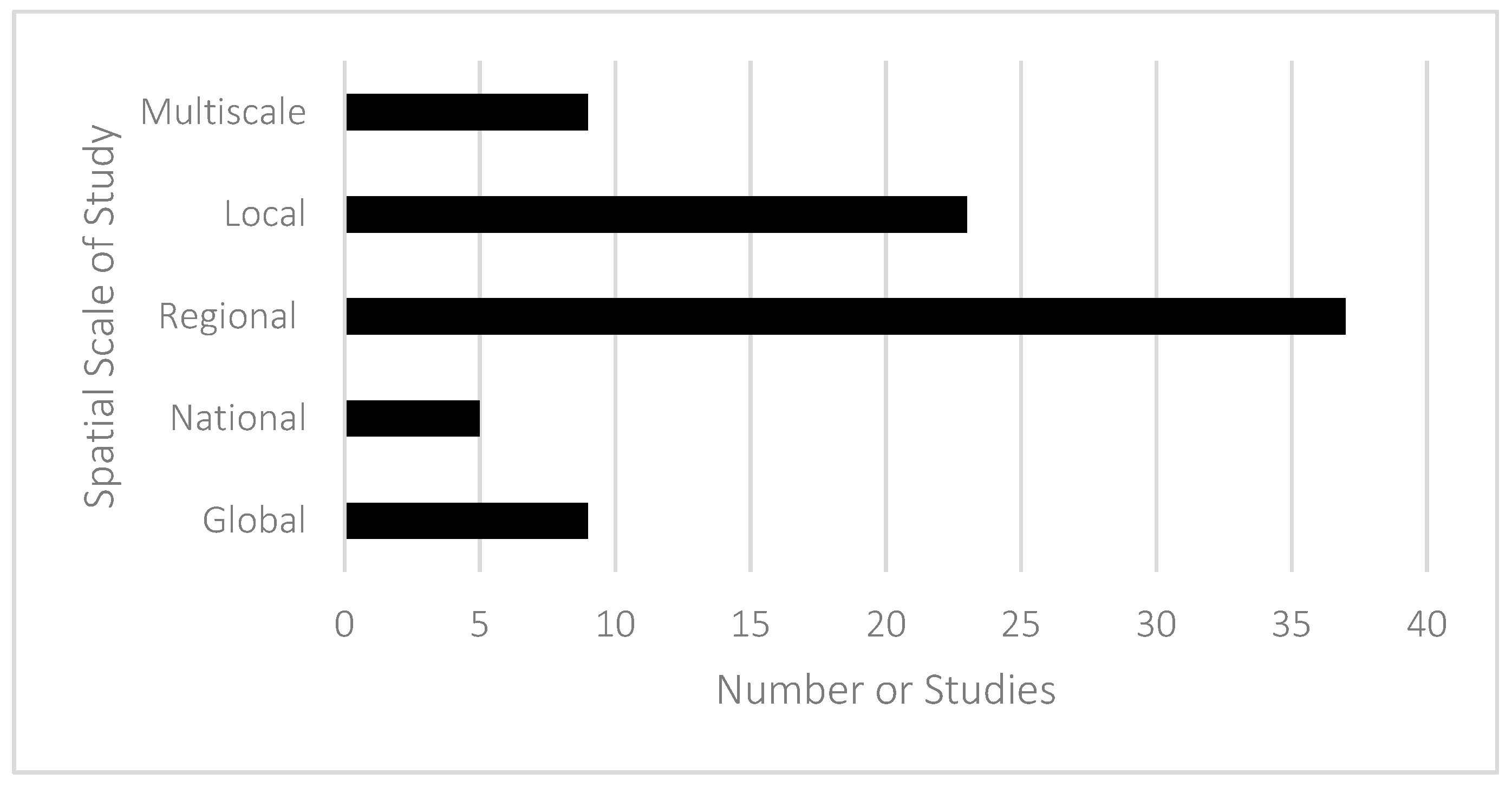

3. Bibliometric Analysis

4. Current Directions and Emerging Trends in the Remote Sensing of HEI Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Research Council. Human Dimensions of Global Environmental Change: Research Pathways for the Next Decade; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council. People and Pixels: Linking Remote Sensing and Social Science; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liverman, D.M.; Cuesta, R.M.R. Human interactions with the Earth system: People and pixels revisited. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2008, 33, 1458–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, G.; Crane, M. Assessment of urban growth in the Tampa Bay watershed using remote sensing data. Remote Sens. Environ. 2005, 97, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torgersen, C.E.; Faux, R.N.; McIntosh, B.A.; Poage, N.J.; Norton, D.J. Airborne thermal remote sensing for water temperature assessment of streams and rivers. Remote Sens. Environ. 2001, 76, 368–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.A.; de Beurs, K.M.; Didan, K.; Inouyes, D.W.; Richardson, A.D.; Jensen, O.P.; O’Keefe, J.O.; Zhang, G.; Nemani, R.R.; van Leeuwen, W.J.D.; et al. Intercomparison, interpolation, and assessment of spring phenology in North America estimated from remote sensing for 1982–2006. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2009, 15, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H. Using remote sensing to assess biodiversity. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2001, 22, 2377–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Vik, J.O.; Mysterud, A.; Gaillard, J.; Tucker, C.J.; Stenseth, N.C. Using the satellite-derived NDVI to assess ecological responses to environmental change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2005, 20, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wulder, M. Optical remote-sensing techniques for the assessment of forest inventory and biophysical parameters. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 1998, 22, 449–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, J.; Vogler, J.B. Land-use and land-cover change in montane mainland southeast Asia. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricope, N.G.; Cassidy, L.; Gaughan, A.; Salerno, J.; Stevens, F.; Hartter, J.; Drake, M.; Mupeta-Muywama, P. Addressing integration challenges of interdisciplinary research in social-ecological systems. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2019, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, A.; Stevens, F.; Pricope, N.G.; Hartter, J.; Cassidy, L.; Salerno, J. Operationalizing vulnerability: Land systems dynamics in a transfrontier conservation area. Land 2019, 8, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakie, T.T.; Laituri, M.; Evangelista, P.H. Assessing the distribution and impacts of Prosopis juliflora through participatory approaches. Appl. Geogr. 2016, 66, 132–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesschen, J.P.; Verburg, P.H.; Staal, S.J. Statistical Methods for Analyzing the Spatial Dimensions of Changes in Land Use and Farming Systems; LUCC Report Series No. 7; The International Livestock Research Institute: Nairobi, Kenya; LUCC Focus 3 Office, Wageningen University: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005; ISBN 9291461784-80. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, I.M.S.; Gergel, S.E.; Coops, N.C.; Henebry, G.M.; Levine, J.; Zerriffi, H.; Shibkoz, E. Integrating remote sensing and ecological knowledge to monitor rangeland dynamics. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 82, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.L.; Teich, I.; Gonzalez-Roglich, M.; Kindgard, A.F.; Ravelo, A.C.; Liniger, H. Land degradation assessment in the Angentinean Puna: Comparing expert knowledge with satellite-derived information. Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 91, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mareya, H.T.; Tagwireyi, P.; Ndaimani, H.; Gara, T.W.; Gwenzi, D. Estimating tree crown area and aboveground biomass in miombo woodlands from high-resolution RGB-only imagery. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2018, 11, 868–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suyanto, S.; Applegate, G.; Permana, R.P.; Khusuiyah, N.; Kurniawan, I. The role of fire changing land use and livelihoods in Riau-Sumatra. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haag, F.; Hajdu, F. Perspectives on local environmental security exemplified by a rural South African Village. Environ. Manag. 2005, 36, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robiglio, V.; Mala, W.A. Integrating local and expert knowledge using participatory mapping and GIS to implement integrated forest management options in Akok, Cameroon. For. Chron. 2005, 81, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valbuena, D.; Verburg, P.H.; Bregt, A.K. A method to define a typology for agent-based analysis in regional land-use research. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2008, 128, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Karaki, N.; Fiaschi, S.; Closson, D. Sustainable development and anthropogenic induced geomorphic hazards in subsiding areas. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 2016, 41, 2282–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bini, M.; Rossi, V.; Amorosi, A.; Pappalardo, M.; Sarti, G.; Noti, V.; Capitani, M.; Fabiani, F.; Gualandi, M.L. Palaeoenvironments and palaeotopography of a multilayered city during the Etruscan and Roman periods: Early interaction of fluvial processes and urban growth at Pisa (Tuscany, Italy). J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 59, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, P.S.; Groucutt, H.S.; Drake, N.A.; Louys, J.; Scerri, E.M.L.; Armitage, S.J.; Zalmout, I.S.A.; Memesh, A.M.; Haptari, M.A.; Soubhi, S.A.; et al. Prehistory and palaeoenvironments of the western Nefud Desert, Saudi Arabia. Archaeol. Res. Asia 2017, 10, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castella, J.C.; Boissau, S.; Trung, T.N.; Quang, D.D. Agrarian transition and lowland-upland interactions in mountain areas in northern Vietnam: Application of a multi-agent simulation model. Agric. Syst. 2005, 86, 312–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, R.A.; Mayer, J.; Applegate, G.; Chokkalingam, U.; Colfer, C.J.P.; Kurniawan, I.; Lachowski, H.; Maus, P.; Permana, R.P.; Ruchiat, Y.; et al. Fire, people and pixels: Linking social science and remote sensing to understand underlying causes and impacts of fires in Indonesia. Hum. Ecol. 2005, 33, 465–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitao, P.J.; Schwieder, M.; Suess, S.; Okujeni, A.; Galvao, L.S.; van der Linden, S.; Hostert, P. Monitoring Natural Ecosystem and Ecological Gradients: Perspectives with EnMAP. Remote Sens. 2015, 7, 13098–13119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, U.; Denier, S.; May, J.H.; Rodrigues, L.; Veit, H. Human-environment interactions in pre-Columbian Amazonia: The case of the Llanos de Moxos, Bolivia. Quat. Int. 2013, 312, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLachlan, A.; Roberts, G.; Biggs, E.; Boruff, B. Subpixel land-cover classification for improved urban area estimates using Landsat. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 5763–5792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purkis, S.J.; Gardiner, R.; Johnston, M.W.; Sheppard, C.R.C. A half-century of coastline change in Diego Garcia: The largest atoll island in the Chagos. Geomorphology 2016, 261, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.; Meredith, T.C.; Johns, T. Exploring methods for rapid assessment of woody vegetation in the Batemi Valley, North-central Tanzania. Biodivers. Conserv. 1999, 8, 447–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimberly, M.C.; Ohmann, J.L. A multi-scale assessment of human and environmental constraints on forest land cover change on the Oregon (USA) coast range. Landsc. Ecol. 2004, 19, 631–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ossola, A.; Hopton, M.E. Measuring urban tree loss dynamics across residential landscapes. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 940–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermeulen, F.; Pince, P.; Weekers, L.; De Dapper, M. Geoarchaeological study of abandoned Roman urban and suburban contexts from central Adriatic Italy. Geoarchaeology 2018, 33, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, J.; Liu, J.Y.; Kuang, W.H.; Xu, X.L.; Zhang, S.W.; Yan, C.Z.; Li, R.D.; Wu, S.X.; Hu, Y.F.; Du, G.M.; et al. Spatiotemporal patterns and characteristics of land-use change in China during 2010–2015. J. Geogr. Sci. 2018, 28, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.D. The race to document archaeological sites ahead of rising sea levels: Recent applications of geospatial technologies in the archaeology of Polynesia. Sustainability 2018, 10, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramitsoglou, I.; Daglis, I.A.; Amiridis, V.; Chrysoulakis, N.; Ceriola, G.; Manunta, P.; Maiheu, B.; De Ridder, K.; Lauwaet, D.; Paganini, M. Evaluation of satellite-derived products for the characterization of the urban thermal environment. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2012, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calver, M.C.; Goldman, B.; Hutchings, P.A.; Kingsford, R.T. Why discrepancies in searching the conservation biology literature matter. Biol. Conserv. 2013, 231, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pautasso, M. The jump in network ecology research between 1990 and 1991 is aweb of science artefact. Ecol. Model. 2014, 286, 11–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagendra, H.; Paul, S.; Pareeth, S.; Dutt, S. Landscapes of Protection: Forest Change and Fragmentation in Northern West Bengal, India. Environ. Manag. 2009, 44, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.C. Land use and cover changes in the critical areas in Northwestern China. In Remote Sensing for Agriculture, Ecosystems, and Hydrology; Owe, V.M., Durso, G., Moreno, J.F., Calera, A., Eds.; Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2004; Volume 5232, pp. 245–256. [Google Scholar]

- Dessie, G.; Kinlund, P. Khat expansion and forest decline in Wondo Genet, Ethiopia. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B-Hum. Geogr. 2008, 90, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonji, S.F.; Taff, G.N. Using satellite data to monitor land-use land-cover change in North-eastern Latvia. Springerplus 2014, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furumo, P.R.; Aide, T.M. Characterizing commercial oil palm expansion in Latin America: Land use change and trade. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Chen, D.W.; Huang, R.H.; Ai, T.H. A dynamic analysis of regional land use and cover changing (LUCC) by remote sensing and GIS: Taking Fuzhou Area as example. In Advanced Environmental, Chemical, and Biological Sensing Technologies Vii; VoDinh, T., Lieberman, R.A., Gauglitz, G., Eds.; Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2010; Volume 7673. [Google Scholar]

- Southworth, J.; Hartter, J.; Binford, M.W.; Goldman, A.; Chapman, C.A.; Chapman, L.J.; Omeja, P.; Binford, E. Parks, people and pixels: Evaluating landscape effects of an East African national park on its surroundings. Trop. Conserv. Sci. 2010, 3, 122–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, R.; Mearns, K.F.; Jordaan, M. Modelling informal Sand Forest harvesting using a Disturbance Index from Landsat, in Maputaland (South Africa). Ecol. Inform. 2017, 39, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.M.; Liu, Z.M.; Song, K.S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, S.M.; Liu, D.W.; Ren, C.Y.; Yang, F. Land use changes in Northeast China driven by human activities and climatic variation. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2009, 19, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Hansen, M.C.; Stehman, S.V.; Patapov, P.V.; Tyulavina, A.; Vermote, E.F.; Townshend, J.R. Global land change from 1982 to 2016. Nature 2018, 560, 639–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaughan, A.E.; Binford, M.W.; Southworth, J. Tourism, forest conversion, and land transformations in the Angkor basin, Cambodia. Appl. Geogr. 2009, 29, 212–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlini, G.; Riitters, K.; Zaccarelli, N.; Petrosillo, I.; Jones, K.B.; Rossi, L. Disturbance patterns in a socio-ecological system at multiple scales. Ecol. Complex. 2006, 3, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurlini, G.; Riitters, K.H.; Zaccarelli, N.; Petrosillo, I. Patterns of disturbance at multiple scales in real and simulated landscapes. Landsc. Ecol. 2007, 22, 705–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahel, C.; Vall, E.; Rodriguez, Z.; Begue, A.; Baron, C.; Augusseau, X.; Lo Seen, D. Analysing plausible futures from past patterns of land change in West Burkina Faso. Land Use Policy 2018, 71, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Y.H.; Shen, H.; Han, Y.; Pan, Y.J. Vegetation coverage change and associated driving forces in mountain areas of Northwestern Yunnan, China using RS and GIS. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2012, 184, 4787–4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.Y.; Dong, Z.B.; Lu, J.F.; Yan, C.Z. The developmental trend and influencing factors of aeolian desertification in the Zoige Basin, eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Aeolian Res. 2015, 19, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Z.K.; Farmer, F.L. Deforestation near public lands: An empirical examination of associated processes. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2013, 26, 605–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricope, N.G.; Gaughan, A.E.; All, J.D.; Binford, M.W.; Rutina, L.P. Spatio-temporal analysis of vegetation dynamics in relation to shifting inundation and fire regimes: Disentangling environmental variability from land management decisions in a southern African transboundary watershed. Land 2015, 4, 627–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.R.; Dearing, J.A.; Yu, L.Z.; Zhang, W.G.; Shi, Y.X.; Zhang, F.R.; Gu, C.J.; Boyle, J.F.; Coulthard, T.J.; Foster, G.C. The recent history of hydro-geomorphological processes in the upper Hangbu river system, Anhui Province, China. Geomorphology 2009, 106, 363–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Chauvenet, A.L.M.; Duffy, J.P.; Cornforth, W.A.; Meillere, A.; Baillie, J.E.M. Tracking the effect of climate change on ecosystem functioning using protected areas: Africa as a case study. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 20, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, G.Z.; Liu, X.P.; Liang, X.; Wang, S.J.; Chen, Y.M.; Pei, F.S.; Xu, X.C. A New Global Land-Use and Land-Cover Change Product at a 1-km Resolution for 2010 to 2100 Based on Human-Environment Interactions. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2017, 107, 1040–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verburg, P.H.; Ellis, E.C.; Letourneau, A. A global assessment of market accessibility and market influence for global environmental change studies. Environ. Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Hori, M.; Murakami, M.; Ono, A.; Kajiwara, K. Possibility of Gcom-C1/SGLI for climate change impacts analyzing. In Networking the World with Remote Sensing; Kajiwara, K., Muramatsu, K., Soyama, N., Endo, T., Ono, A., Akatsuka, S., Eds.; Copernicus Gesellschaft Mbh: Gottingen, Germany, 2010; Volume 38, pp. 542–546. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Ono, A.; Kajiwara, K. A study on possibility of land vegetaflon obseirvation with SGLI/GCOM-C. In Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites XI; Meynart, R., Neeck, S.P., Shimoda, H., Habib, S., Eds.; Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2007; Volume 6744. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Ono, Y.; Kajiwara, K.; Tanigawa, S. The Examination of Land products from GCOM-C1/SGLI. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Milan, Italy, 26–31 July 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 5099–5102. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Hori, M.; Murakami, H.; Kikuchi, N. The possibility of SGLI/GCOM-C for Global environment change monitoring. In Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites X; Meynart, R., Neeck, S.P., Shimoda, H., Eds.; Spie-Int Soc Optical Engineering: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2006; Volume 6361. [Google Scholar]

- Honda, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Hori, M.; Murakami, H.; Kikuchi, N. Global environment monitoring using the next generation satellite sensor, SGLI/GCOM-C. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, 2005. IGARSS ’05, Seoul, Korea, 29–29 July 2005; IEEE: New York, NY, USA; pp. 4205–4207. [Google Scholar]

- Herrmann, S.M.; Sall, I.; Sy, O. People and pixels in the Sahel: A study linking coarse-resolution remote sensing observations to land users’ perceptions of their changing environment in Senegal. Ecol. Soc. 2014, 19, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judex, M.; Rohrig, J.; Linsoussi, C.; Thamm, H.P.; Menz, G. Vegetation Cover and Land Use Change in Benin; Springer-Verlag Berlin: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Kant, Y.; Bharath, B.D.; Mallick, J.; Atzberger, C.; Kerle, N. Satellite-based analysis of the role of land use/land cover and vegetation density on surface temperature regime of Delhi, India. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2009, 37, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, I.P.J.; Landman, M.; Cowling, R.M.; Gaylard, A. Expert-derived monitoring thresholds for impacts of megaherbivores on vegetation cover in a protected area. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 177, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaccarelli, N.; Petrosillo, I.; Zurlini, G.; Riitters, K.H. Source/Sink Patterns of Disturbance and Cross-Scale Mismatches in a Panarchy of Social-Ecological Landscapes. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nursamsi, I.; Komala, W.R. Assessment of the successfulness of mangrove plantation program through the use of open source software and freely available satellite images. Nusant. Biosci. 2017, 9, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, P.; Hostert, P. Forest Cover Dynamics during Massive Ownership Changes-Annual Disturbance Mapping Using Annual LANDSAT Time-Series; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 22, pp. 307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P.Y.; Feng, Y.Q.; Hwang, Y.H. Deforestation in a tropical compact city (Part A) Understanding its socio-ecological impacts. Smart Sustain. Built Environ. 2016, 5, 47–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, T.; Everard, M.; Horswell, M. Community-based groundwater and ecosystem restoration in semi-arid north Rajasthan (3): Evidence from remote sensing. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 21, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galletti, C.S.; Ridder, E.; Falconer, S.E.; Fall, P.L. Maxent modeling of ancient and modern agricultural terraces in the Troodos foothills, Cyprus. Appl. Geogr. 2013, 39, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.M.; Liu, F.; Liu, J.Y.; Xiao, X.M.; Qin, Y.W. Status of land use intensity in China and its impacts on land carrying capacity. J. Geogr. Sci. 2017, 27, 387–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.N.; Li, S.C.; Yang, F.; Li, M.J. Evaluating the accuracy of Chinese pasture data in global historical land use datasets. Sci. China-Earth Sci. 2018, 61, 1685–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koglo, Y.S.; Agyare, W.A.; Diwediga, B.; Sogbedji, J.M.; Adden, A.K.; Gaiser, T. Remote sensing-based and participatory analysis of forests, agricultural land dynamics, and potential land conservation measures in Kloto District (Togo, West Africa). Soil Syst. 2018, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acevedo, M.F.; Callicott, J.B.; Monticino, M.; Lyons, D.; Palomino, J.; Rosales, J.; Delgado, L.; Ablan, M.; Davila, J.; Tonella, G.; et al. Models of natural and human dynamics in forest landscapes: Cross-site and cross-cultural synthesis. Geoforum 2008, 39, 846–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwamura, T.; Lambin, E.F.; Silvius, K.M.; Luzar, J.B.; Fragoso, J.M.V. Agent-based modeling of hunting and subsistence agriculture on indigenous lands: Understanding interactions between social and ecological systems. Environ. Model. Softw. 2014, 58, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.H. Remote sensing of impervious surfaces in the urban areas: Requirements, methods, and trends. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 117, 34–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgopoulou, I.A.; Kalivas, D.P.; Petropoulos, G.P. Urban vegetation cover extraction from hyperspectral remote sensing imagery and GIS-based spatial analysis techniques: The case of Athens, Greece. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Athens, Greece, 5–7 September 2013; Lekkas, T.D., Ed.; Global NEST Secretariat: Athens, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, W.D.; Yang, J. Sub-pixel vs. super-pixel-based greenspace mapping along the urban-rural gradient using high spatial resolution Gaofen-2 satellite imagery: A case study of Haidian District, Beijing, China. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2017, 38, 6386–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishtiaque, A.; Shrestha, M.; Chhetri, N. Rapid urban growth in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal: Monitoring land use land cover dynamics of a Himalayan city with Landsat imageries. Environments 2017, 4, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, M.; Kandya, A. Impact of urbanization and land-use/land-cover change on diurnal temperature range: A case study of tropical urban airshed of India using remote sensing data. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 506, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tagil, S.; Gormus, S.; Cengiz, S. The relationship of urban expansion, landscape patterns and ecological processes in Denizli, Turkey. J. Indian Soc. Remote Sens. 2018, 46, 1285–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y. Landscape pattern and ecosystem service value changes: Implications for environmental sustainability planning for the rapidly urbanizing summer capital of the Philippines. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 116, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y. Intensity and spatial pattern of urban land changes in the megacities of Southeast Asia. Land Use Policy 2015, 48, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, S.; Soffianian, A.R.; Koupaei, S.S.; Pourmanafi, S.; Saatchi, S. Wetland restoration prioritizing, a tool to reduce negative effects of drought; An application of multicriteria-spatial decision support system (MC-SDSS). Ecol. Eng. 2018, 112, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Yurco, K.; Young, K.R.; Crews, K.A.; Shinn, J.E.; Eisenhart, A.C. Livelihood dynamics across a variable flooding regime. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, A.M.C.; Yang, Y.R.; McManus, D.P.; Gray, D.J.; Giraudoux, P.; Barnes, T.S.; Williams, G.M.; Magalhaes, R.J.S.; Hamm, N.A.S.; Clements, A.C.A. The landscape epidemiology of echinococcoses. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2016, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, U.; Canal-Beeby, E.; Fehr, S.; Veit, H. Raised fields in the Bolivian Amazonia: A prehistoric green revolution or a flood risk mitigation strategy? J. Archaeol. Sci. 2011, 38, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardo, U.; May, J.H.; Veit, H. Mid- to late-Holocene fluvial activity behind pre-Columbian social complexity in the southwestern Amazon basin. Holocene 2012, 22, 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, F.C.; Devanthery, N.; Balbo, A.L.; Madella, M.; Monserrat, O. Use of satellite SAR for understanding long-term human occupation dynamics in the monsoonal semi-arid plains of North Gujarat, India. Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 11420–11443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conesa, F.C.; Madella, M.; Galiatsatos, N.; Balbo, A.L.; Rajesh, S.V.; Ajithprasad, P. CORONA photographs in monsoonal semi-arid environments: Addressing archaeological surveys and historic landscape dynamics over North Gujarat, India. Archaeol. Prospect. 2015, 22, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biagetti, S.; Merlo, S.; Adam, E.; Lobo, A.; Conesa, F.C.; Knight, J.; Bekrani, H.; Crema, E.R.; Alcaina-Mateos, J.; Madella, M. High and medium resolution satellite imagery to evaluate late Holocene human-environment interactions in arid lands: A case study from the Central Sahara. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dearing, J.A.; Acma, B.; Bub, S.; Chambers, F.M.; Chen, X.; Cooper, J.; Crook, D.; Dong, X.H.; Dotterweich, M.; Edwards, M.E.; et al. Social-ecological systems in the Anthropocene: The need for integrating social and biophysical records at regional scales. Anthr. Rev. 2015, 2, 220–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Laurance, W.F.; O’Brien, T.G.; Wegmann, M.; Nagendra, H.; Turner, W. Satellite remote sensing for applied ecologists: Opportunities and challenges. J. Appl. Ecol. 2014, 51, 839–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, M.M. Seeing the forest and the trees: Human-environment interactions in forest ecosystems. Prof. Geogr. 2006, 58, 359–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perring, M.P.; Standish, R.J.; Price, J.N.; Craig, M.D.; Erickson, T.E.; Ruthrof, K.X.; Whiteley, A.S.; Valentine, L.E.; Hobbs, R.J. Advances in restoration ecology: Rising to the challenges of the coming decades. Ecosphere 2015, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettorelli, N.; Safi, K.; Turner, W. Satellite remote sensing, biodiversity research and conservation of the future. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, H.G.; Alganci, U.; Usta, G. The role of remote sensing and GIS for security. In Integration of Information for Environmental Security; Coskun, H.G., Cigizoglu, H.K., Maktav, M.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Gatrell, J.D.; Jensen, R.R. Geotechnologies in Place and the Environment; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2009; Volume 1, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.S.; Han, D. Multisensor fusion of Landsat images for high-resolution thermal infrared images using sparse representations. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 10, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguz, H. A software tool for retrieving land surface temperature from ASTER imagery. Tarim Bilimleri Derg. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 21, 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Grunwald, S.; Thompson, J.A.; Boettinger, J.L. Digital soil mapping and modeling at continental scales: Finding solutions for global issues. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2011, 75, 1201–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, M.S.R.; Bajracharya, B.; Pradhan, S.; Shrestha, B.; Bajracharya, R.; Shakya, K.; Wesselman, S.; Ali, M.; Bajracharya, S. Adoption of geospatial systems towards evolving sustainable Himalyan Mountain development. In Isprs Technical Commission VIII Symposium; Dadhwal, V.K., Diwakar, P.G., Seshasai, M.V.R., Raju, P.L.N., Hakeem, A., Eds.; Copernicus Gesellschaft Mbh: Gottingen, Germany, 2014; Volume 40–48, pp. 1319–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke, T.; Hay, G.J.; Weng, Q.H.; Resch, B. Collective sensing: Integrating geospatial technologies to understand urban systems—An overview. Remote Sens. 2011, 3, 1743–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagl, G.; Resch, B.; Blaschke, T. Contextual sensing: Integrating contextual information with human and technical geo-sensor information for smart cities. Sensors 2015, 15, 17013–17035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Journal Title | Number of Publications |

|---|---|

| Remote Sensing | 4 |

| Applied Geography | 2 |

| Earth Surface Processes and Landforms | 2 |

| Ecological Indicators | 2 |

| Ecology and Society | 2 |

| Environmental Management | 2 |

| Environmental Research Letters | 2 |

| Geoforum | 2 |

| Geomorphology | 2 |

| Human Ecology | 2 |

| International Journal of Remote Sensing | 2 |

| Journal of Archeological Science | 2 |

| Journal of Geographic Science | 2 |

| Journal of the Indian Society of Remote Sensing | 2 |

| Land Use Policy | 2 |

| Landscape Ecology | 2 |

| Science of the Total Environment | 2 |

| Sensors, Systems, and Next-Generation Satellites X | 2 |

| Research Area | Count |

|---|---|

| Environmental Sciences & Ecology | 47 |

| Remote Sensing | 26 |

| Geology | 25 |

| Physical Geography | 17 |

| Engineering | 10 |

| Geography | 10 |

| Imaging Science & Photographic Technology | 10 |

| Sociology | 6 |

| Agriculture | 5 |

| Archaeology | 5 |

| Biodiversity & Conservation | 5 |

| Anthropology | 4 |

| Public Administration | 4 |

| Science & Technology—Other | 4 |

| Urban Studies | 4 |

| Computer Science | 3 |

| Instruments & Instrumentation | 3 |

| Water Resources | 3 |

| Information Science & Library Science | 2 |

| Life Sciences & Biomedicine—Other | 2 |

| Meteorology & Atmospheric Sciences | 2 |

| Optics | 2 |

| Telecommunications | 2 |

| Business & Economics | 1 |

| Chemistry | 1 |

| Construction & Building Technology | 1 |

| Demography | 1 |

| Development Studies | 1 |

| Electrochemistry | 1 |

| Energy & Fuels | 1 |

| Geochemistry & Geophysics | 1 |

| Infectious Diseases | 1 |

| Social Issues | 1 |

| Remote Sensing Platform | No. Studies | No. Platforms Used | No. Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satellite | 83 | One | 67 |

| Aerial (plane) | 15 | Two | 14 |

| UAV | 2 | Three | 1 |

| Helikite | 1 | Four | 1 |

| Not Specified | 1 | ||

| Terrestrial | 1 | ||

| N/A | 17 |

| No. Satellite Sources | No. Studies |

|---|---|

| Ten | 1 |

| Eight | 1 |

| Six | 1 |

| Five | 2 |

| Four | 4 |

| Three | 13 |

| Two | 28 |

| One | 33 |

| Total | 83 |

| Satellite & Sensor Name | Sensor Type | No. Times Utilized | Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALOS AVNIR-2 | Multispectral | 3 | Bini et al., 2015; Estoque & Murayama, 2015; Griffiths & Hostert, 2015 |

| ALOS PALSAR | Radar | 1 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| ASTER | Multispectral | 8 | Biagetti et al., 2017; Bini et al., 2015; Conesa et al., 2015; Galletti et al., 2013; Judex et al., 2010; Kant et al., 2009 *; Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 *; Oguz, 2015 * |

| AVHRR | Multispectral | 6 | Bartlett et al., 2000; Dennis et al., 2005; Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 *; Pricope et al., 2015; Song, 2018; Wei et al., 2018 |

| CORONA | Greyscale | 4 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016; Conesa et al., 2015; McCoy, 2018; Wu, 2004 |

| COSMO_SkyMed | Radar | 1 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| Envisat ASAR | Radar | 2 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016; Conesa et al., 2014 |

| Envisat AATSR | Multispectral | 1 | Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 * |

| EO-1 Hyperion | Hyperspectral | 2 | Georgopoulou et al., 2013; Leitao et al., 2015 |

| EO-1 ALI | Multispectral | 1 | Leitao et al., 2015 |

| ESR-1 ATSR | Radar, Infrared | 2 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016; Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 * |

| ESR-2 ATSR | Radar | 1 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| Gaofen-2 | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 2 | Ning et al., 2018; Yin & Yan, 2017 |

| ICESAT | LiDAR | 1 | Lombardo et al., 2011 |

| IKONOS | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 1 | Galletti et al., 2013 |

| Landsat MSS | Multispectral | 6 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| Landsat TM | Multispectral | 29 | Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 * |

| Landsat ETM+ | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 25 | Jin & Han, 2017*, Nursamsi & Komala, 2017 *** |

| Landsat OLI | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 11 | Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 *, Nursamsi & Komala, 2017 *** |

| LISS-111 | Multispectral | 11 | |

| MODIS Aqua & Terra | Multispectral | 7 | Furumo & Aide, 2017; Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 *; Li et al., 2017; Mohan & Kandya, 2015 *; Pricope et al., 2015; Song, 2018; Wei et al., 2018 |

| MSG-SEVIRI | Multispectral | 1 | Keramitsoglou et al., 2012 * |

| Quickbird | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 2 | Galletti et al., 2013; Yin et al., 2015 |

| SAR | Radar | 1 | Dennis et al., 2005 |

| Sentinel-1A | Radar | 1 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| SGLI/GCOM-C | Near UV to TIR | 5 | Honda *, 2005; 2006; 2007; 2010; 2015 |

| SPOT (not specified) | Multispectral | 1 | Bini et al., 2015 |

| SPOT 1 | Panchromatic | 1 | Abou Karaki et al., 2016 |

| SPOT 5 | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 4 | Jahel et al.; 2018; Ming et al., 2010; Smit et al., 1999; Tan et al., 2016 |

| SPOT XS | Multispectral | 1 | Dennis et al., 2005 |

| SRTM | Radar | 8 | Biagetti et al., 2017; Breeze et al., 2017; Conesa et al., 2015; Conesa et al., 2014; Lombardo et al., 2011; 2012; Verburg et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2015 |

| TRMM PR | Radar | 1 | Pricope et al., 2015 |

| WorldView 1 | Panchromatic | 1 | Biagetti et al., 2017 |

| WorldView 2 | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 3 | Biagetti et al., 2017 ***; McCoy, 2018; Purkis et al.; 2016 |

| WorldView 3 | Multispectral, Panchromatic | 1 | Biagetti et al., 2017 |

| Not specified | 8 | Acevedo et al., 2008; Castella et al., 2005; He, 2018; Herrmann et al., 2014; Liverman & Cuesta, 2008; Moon & Farmer, 2013; Pettorelli et al., 2012; Tanaka & Nishii, 2013 | |

| Google Earth | 9 | Conesa et al., 2015; Furumo & Aide, 2017; Georgopoulou et al., 2013; Lombardo 2011; 2012; 2013; Nursamsi & Komala, 2017; Ossola & Hopton, 2018; Vermeulen et al., 2018 | |

| ESRI | 2 | Breeze et al., 2017; Conesa et al., 2015; | |

| Bing | 2 | Breeze et al., 2017; Vermeulen et al., 2018 |

| Socio-Economic Data Type | No. Times Utilized | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Agricultural census | 1 | Liverman & Cuesta, 2008 |

| Archival data | 1 | Dessie & Kinlund, 2008 |

| Commodity trade data | 1 | Furumo & Aide, 2017 |

| Economic data | 3 | Li et al., 2017; Verburg et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2017 |

| Employment & labor data | 2 | Moon & Farmer, 2013; Wu, 2004 |

| Field survey | 1 | Dennis et al., 2005 |

| Focus group | 1 | Herrman et al., 2014 |

| Group discussion/interview | 2 | Dennis et al., 2005; Dessie & Kinlund, 2008 |

| Houshold survey/interview | 7 | Castella et al., 2005; Dessie & Kinlund, 2008; Dennis et al., 2005; Iwamura et al., 2014; King et al., 2018; Liverman & Cuesta, 2008; Fox & Vogler, 2005 |

| Housing trend data | 2 | Moon & Farmer, 2013; Tanaka & Nishii, 2013 |

| Individual interview | 6 | Dennis et al., 2005; Estoque & Murayama, 2013; Fox & Vogler, 2005; Iwamura et al., 2014; Jahel et al., 2018; Koglo et al., 2018 |

| Key informant survey/interview | 5 | Dessie & Kinlund, 2008; Smit et al., 2016; Jahel et al., 2018; Castella et al., 2005; Fox & Vogler, 2005 |

| Land use & production | 2 | Ossola & Hopton, 2018; Wu, 2004 |

| Listing exercise | 1 | Dessie & Kinlund, 2008 |

| Matrix scoring | 1 | Herrmann et al., 2014 |

| Other population data | 6 | Li et al., 2017; Verburg et al., 2011; Yan et al., 2017; Moon & Farmer, 2013; Yin et al., 2015; Wu, 2004 |

| Participatory mapping/livelihood mapping | 3 | Herrmann et al., 2014, Dennis et al., 2005; King et al., 2018 |

| Population Census | 6 | Bartlett et al., 2000; Dai et al., 2009; Fonji & Taff, 2014; Ossola & Hopton, 2018; Tanaka & Nishii, 2013; Jahel et al., 2018 |

| Ranking exercise | 1 | Dessie & Kinlund, 2008 |

| Rural appraisal | 1 | Dennis et al., 2005 |

| Socio-economic data (unspecified) | 1 | Iwamura et al., 2014 |

| Transect walks | 1 | Dessie & Kinlund, 2008 |

| Total studies using socio-economic data | 27 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

G. Pricope, N.; L. Mapes, K.; D. Woodward, K. Remote Sensing of Human–Environment Interactions in Global Change Research: A Review of Advances, Challenges and Future Directions. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11232783

G. Pricope N, L. Mapes K, D. Woodward K. Remote Sensing of Human–Environment Interactions in Global Change Research: A Review of Advances, Challenges and Future Directions. Remote Sensing. 2019; 11(23):2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11232783

Chicago/Turabian StyleG. Pricope, Narcisa, Kerry L. Mapes, and Kyle D. Woodward. 2019. "Remote Sensing of Human–Environment Interactions in Global Change Research: A Review of Advances, Challenges and Future Directions" Remote Sensing 11, no. 23: 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11232783

APA StyleG. Pricope, N., L. Mapes, K., & D. Woodward, K. (2019). Remote Sensing of Human–Environment Interactions in Global Change Research: A Review of Advances, Challenges and Future Directions. Remote Sensing, 11(23), 2783. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs11232783