Abstract

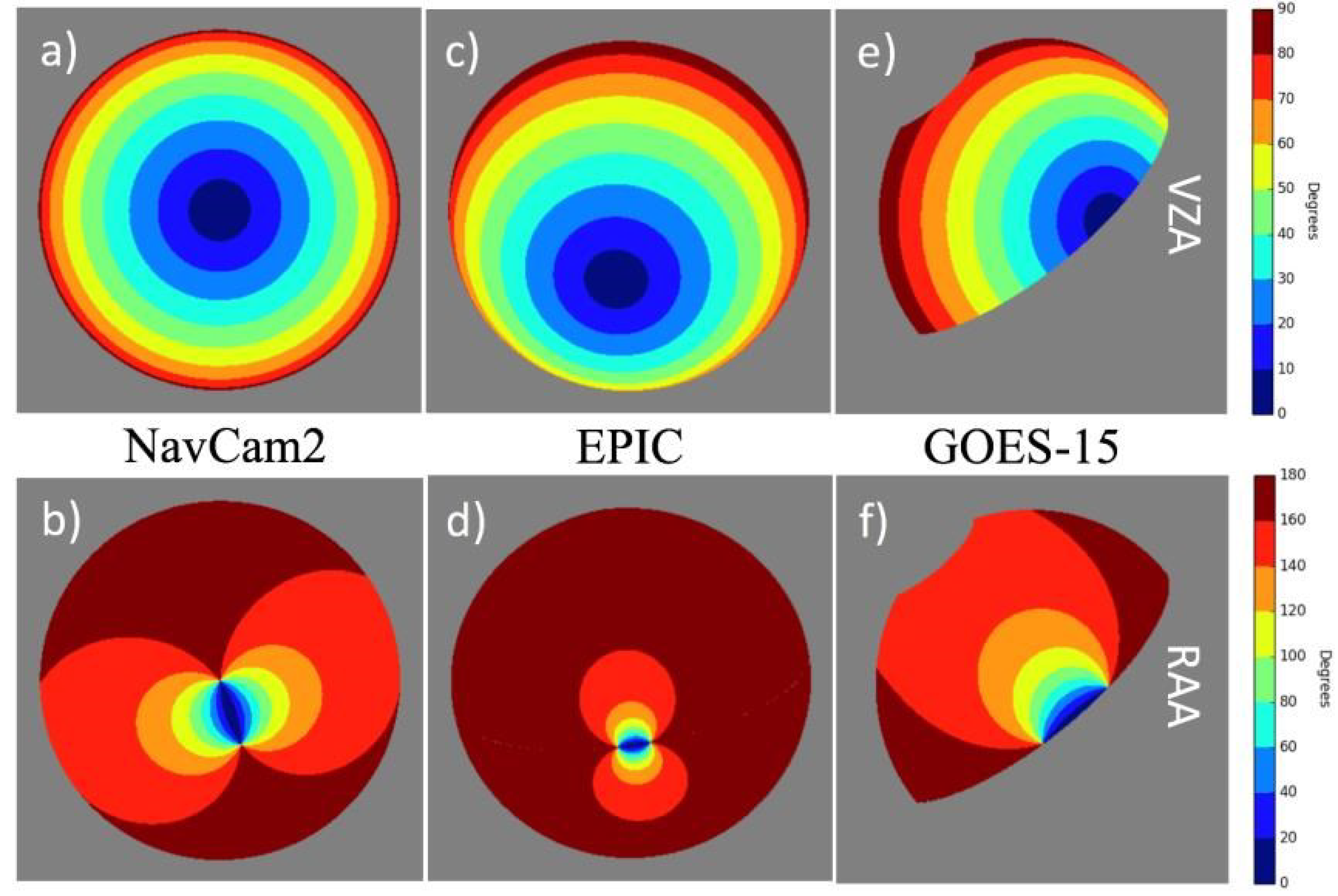

The Earth-viewed images acquired by the space probe OSIRIS-REx during its Earth gravity assist flyby maneuver on 22 September 2017 provided an opportunity to radiometrically calibrate the onboard NavCam imagers. Spatially-, temporally-, and angularly-matched radiances from the Earth viewing GOES-15 and DSCOVR-EPIC imagers were used as references for deriving the calibration gain of the NavCam sensors. An optimized all-sky tropical ocean ray-matching (ATO-RM) calibration approach that accounts for the spectral band differences, navigation errors, and angular geometry differences between NavCam and the reference imagers is formulated in this paper. Prior to ray-matching, the GOES-15 and EPIC pixel level radiances were mapped into the NavCam field of view. The NavCam 1 ATO-RM gain is found to be 9.874 × 10−2 Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1 with an uncertainty of 3.7%. The ATO-RM approach predicted an offset of 164, which is close to the true space DN of 170. The pre-launch NavCam 1 and 2 gains were compared with the ATO-RM gain and were found to be within 2.1% and 2.8%, respectively, suggesting that sensor performance is stable in space. The ATO-RM calibration was found to be consistent within 3.9% over a factor of ±2 NavCam 2 exposure times. This approach can easily be adapted to inter-calibrate other space probe cameras given the current constellation of geostationary imagers.

1. Introduction

OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, and Security–Regolith Explorer) is a NASA mission designed to characterize the geology, texture, morphology, geochemistry, and spectral properties of the near-Earth asteroid (101955) Bennu [1]. Bennu is a carbonaceous asteroid thought to contain remnants of the building blocks of the solar system. Bennu has a mean radius of 246 m and orbits the sun with a semi-major axis of 1.13 astronomical unit (AU), which is situated between Earth (1.0 AU) and Mars (1.52 AU). The probe is designed to map the asteroid surface at a distance between 5 km and 0.7 km above the surface. Once the remote sensing of the asteroid is complete, the probe will return a minimum 60-g sample of pristine carbonaceous asteroid regolith for later lab analysis on Earth. The probe was launched on 8 September 2016 and reached Bennu on 3 December 2018 [2]. The probe will depart Bennu in 2021 and return to Earth to land at the Utah Test and Training Range on 24 September 2023. A more detailed overview of the mission is contained in Lauretta et al. 2017 [3].

The Touch and Go Camera System (TAGCAMS) was included in the spacecraft suite of instruments to support optical navigation during asteroid proximity operations, provide images for on-board natural feature tracking during sample acquisition, and document the asteroid sample stow operations [4]. TAGCAMS contains 3 cameras: NavCam 1, NavCam 2, and StowCam. NavCam 1 is the primary optical navigation camera during most mission phases, acquiring images of star fields and the target asteroid to determine spacecraft ephemerides. NavCam 2 is identical to NavCam 1, except that its boresight is optimized for Natural Feature Tracking (NFT) imaging. It serves as a back-up to NavCam 1 and is the primary natural feature tracking camera. StowCam is identical to NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 except that it is pointed at the Sample Return Capsule (SRC) and includes an integrated Bayer color filter on its detector and its lens is focused to provide optimal imaging of the interior of the OSIRIS-REx sample return capsule. Since there is no auto exposure capability on the cameras, the camera calibration is critical for setting exposure times when observing Bennu or other celestial bodies that are in the camera field of view. Accurately calibrated NavCam images also allow for more exact measurements of Bennu’s albedo. After arrival at Bennu, NavCam 1 imaged a series of point-source objects off the limb of the asteroid [5]. Analysis of these calibrated images suggest that the objects are particles that are accelerated and ejected from the surface. To verify the camera pre-launch radiometric calibration, the spacecraft operations captured 23 NavCam 1 and three NavCam 2 images of Earth during an Earth gravity assist (EGA) flyby maneuver on 22 September 2017. These images contain the nearly-fully illuminated Earth disk centered over the East Pacific Ocean (Figure 1).

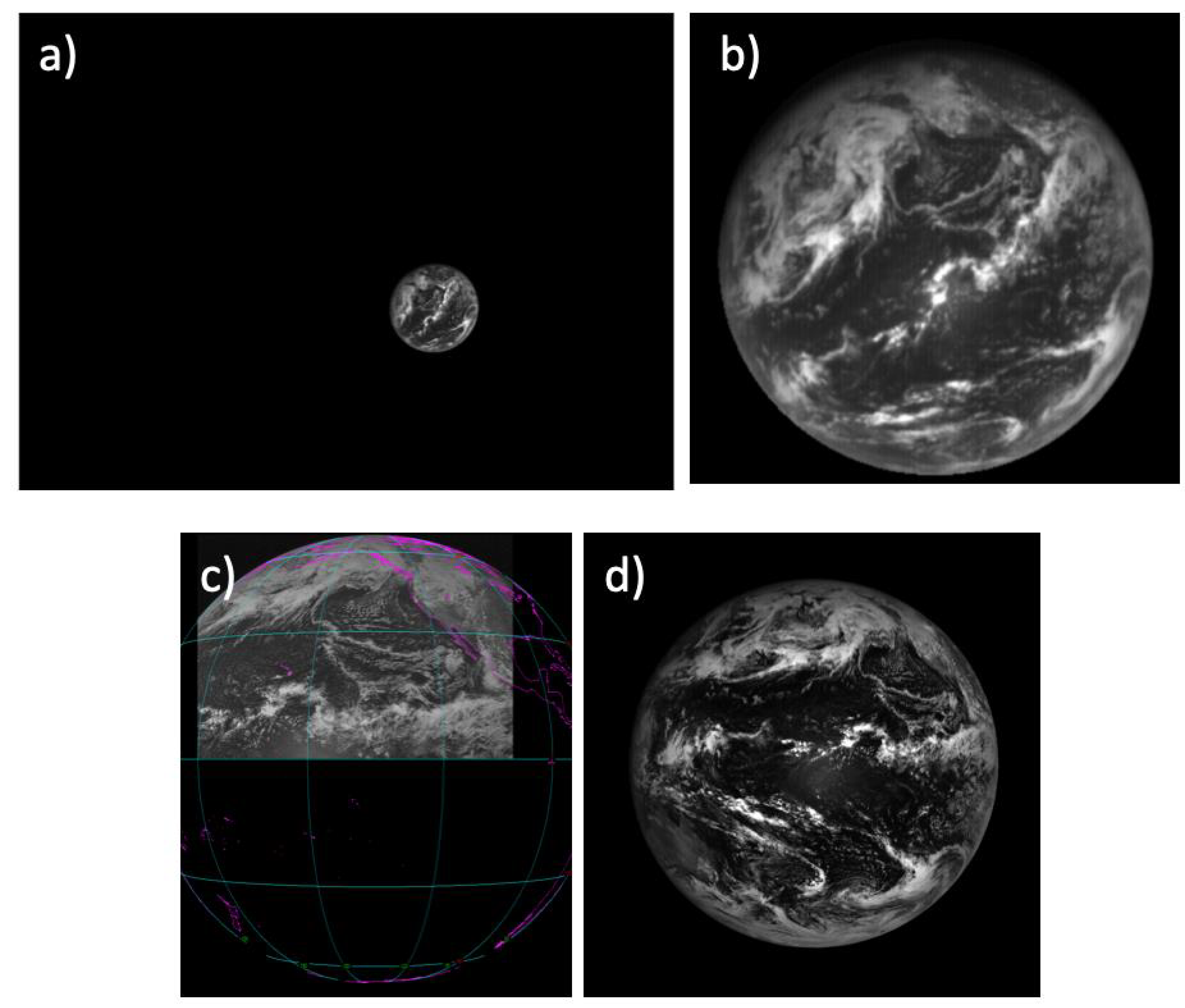

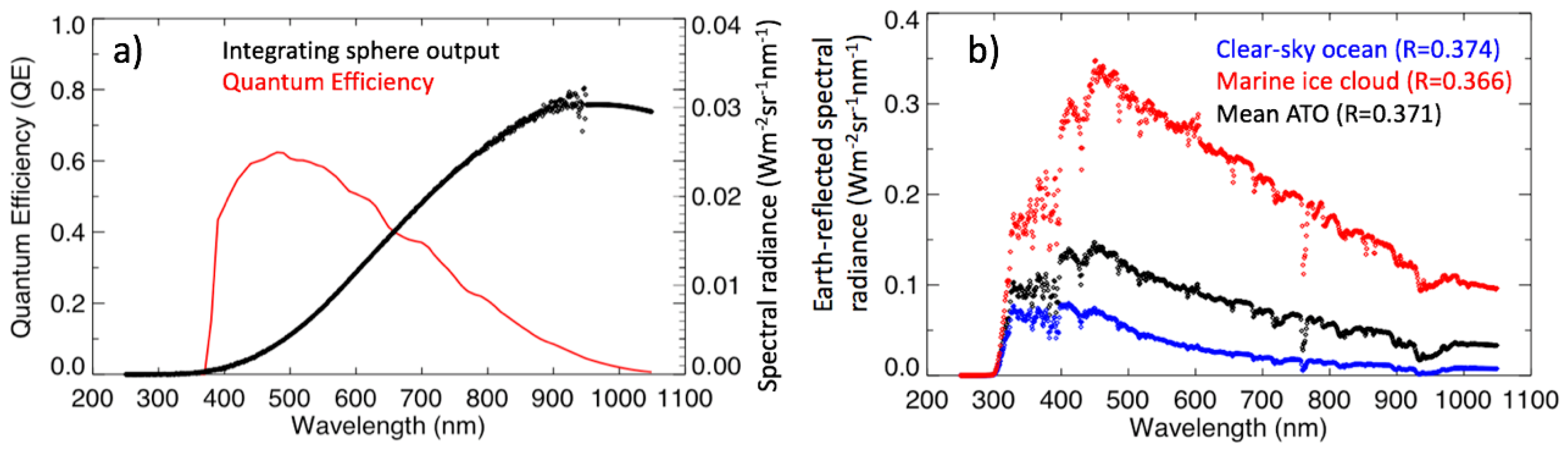

Figure 1.

(a) The OSIRIS-REx NavCam 2 22 September 2017 22:38:27 GMT image. (b) The same as (a) except with Earth centered and zoomed at 425 × 425 pixels. The NavCam-relative Earth North and South Poles are located along the upper left and lower right corner diagonal. (c) The 22:30 GMT GOES-15 NH imager visible channel. (d) The 22:41:14 GMT DSCOVR-EPIC band 7 (0.68 µm) image.

The constellation of well-calibrated Earth-viewing satellite imagers provide a calibration reference to radiometrically scale the NavCam response. The most direct inter-satellite calibration approach compares simultaneous nadir overpass (SNO) radiance pairs from two sensors [6,7]. It has now become routine to inter-calibrate operational sensor visible channels with well-calibrated sensors, such as Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) and Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS). For example, the Advanced Very-High-Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) sensor series [8,9,10,11,12] and the geostationary (GEO) imager [13,14,15] constellation were inter-calibrated with MODIS. Under ideal circumstances, the well-calibrated MODIS or VIIRS sensors could possibly be used to directly inter-calibrate the NavCam images. However, all of the NavCam images were sampled during a period of 1.5 h period, during which only one MODIS or VIIRS swath was available for inter-calibration.

Given the circumstances, the best NavCam inter-calibration opportunity would be with a well-calibrated GEO imager. GEO imagers are located at the equatorial latitude in an Earth-relative stationary orbit, and continuously observe the same spatial extent of Earth below. This setup allows the GEO imager to capture multiple images during the OSIRIS-REx EGA maneuver. This study calibrates the sequence of NavCam images by utilizing coincident ray-matched NavCam and GEO imager radiance pairs. The NavCam images are mostly centered over the Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES)-15 geostationary domain, which has a subsatellite longitude of 135° West at 0° latitude. The other neighboring Himwari-8 and GOES-16 GEO imagers, which are located at 140° East and 90° West, respectively, are too far away to provide any near-nadir views of the NavCam geographic domain. Another NavCam inter-calibration prospect used in this study is the Deep Space Climate Observatory Earth Polychromatic Camera (DSCOVR-EPIC) imager [16]. The DSCOVR satellite obit is located at an Earth and sun gravitational minima or Lagrangian point (L1) and has the same sun-relative orbital period as Earth. This configuration enables the EPIC imager to continuously observe the sunlit side of Earth.

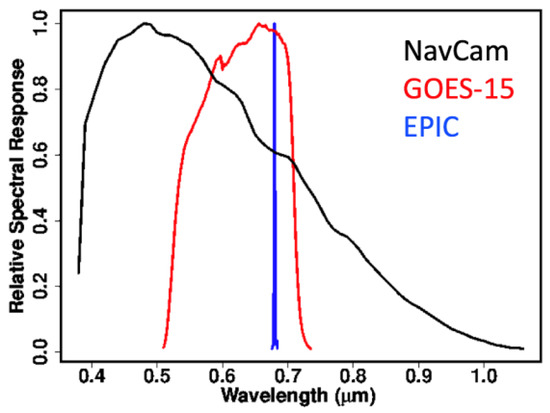

This study first radiometrically scales both the GOES-15 and DSCOVR-EPIC imager visible bands to the same Aqua-MODIS C6.1 band 1 (0.65µm) reference calibration using the NASA Clouds and the Earth’s Radiant Energy System (CERES) project GEO/MODIS all-sky tropical ocean ray-matching (ATO-RM) calibration approach [13]. The CERES ATO-RM algorithm was validated using multiple well-characterized desert targets and a deep convective cloud ray-matching (DCC-RM) algorithm, and it was found that the multiple independent calibration approaches were consistent within 1% [13]. This study modifies the ATO-RM algorithm to inter-calibrate the NavCam image response with both the GOES-15 and EPIC sensors. The greatest challenge is finding a balance between the degree of angular matching and sufficient radiance pair sampling across the dynamic range to perform a meaningful linear regression. Another challenge is the NavCam spectral band response, which is very broad compared with the GOES-15 and EPIC spectral response functions. Inadequate angle matching and spectral adjustments may bias the NavCam calibration results.

Section 2 of this paper describes the NavCam, GOES-15 and EPIC datasets. The mapping of the GOES-15 and EPIC pixel-level radiances into the NavCam field of view is discussed in Section 3. Section 4 outlines the modified NavCam ATO-RM approach that optimizes the angle matching and spectral adjustments. The ATO-RM calibration results for the two NavCam imagers are described in Section 5. Section 6 provides the best estimate of the NavCam 1 gain and uncertainty. Section 7 compares the NavCam gain with the pre-launch gain. Conclusions are provided in Section 8.

2. Data

2.1. OSIRIS-REx NavCam Data

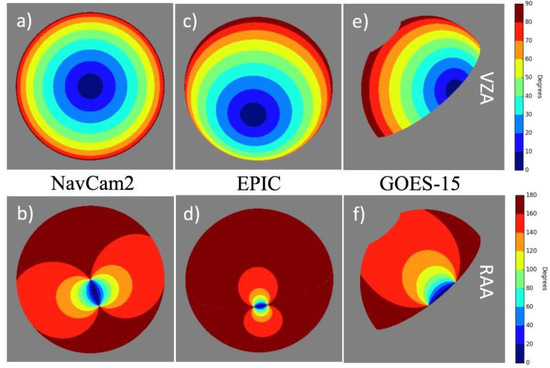

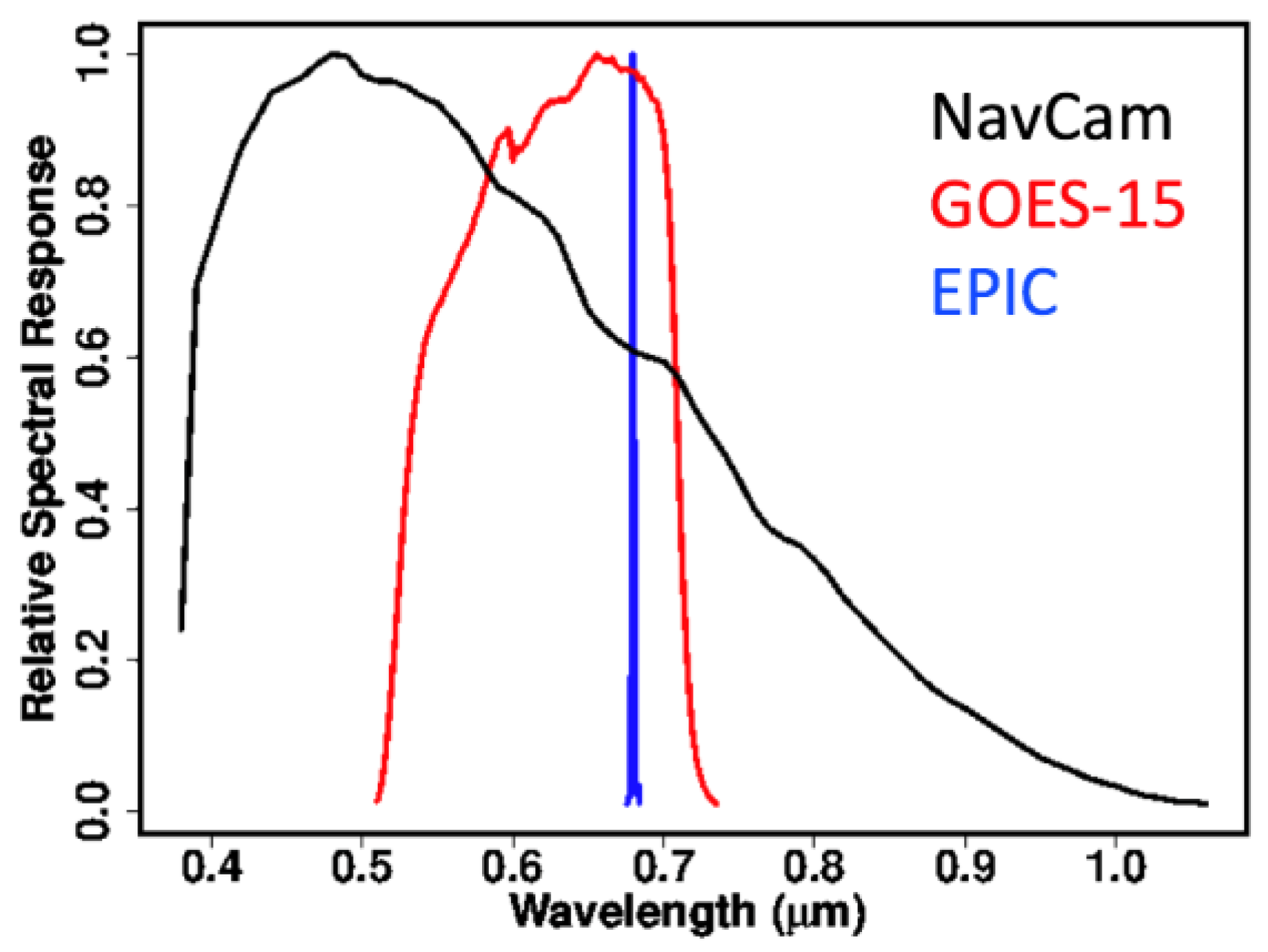

A total of 23 NavCam 1 and three NavCam 2 Earth-view images were obtained from the OSIRIS-REx EGA data set [17]. These images were acquired for calibration purposes during the OSIRIS-REx probe EGA maneuver on 22 September 2017. The NavCam images were taken between 21:08:30 and 22:16:35 GMT, during which the probe trajectory was located between 110,500 and 137,200 km away from the surface of the Earth. Both NavCam 1 and 2 have a medium field of view of 44° by 32° and a 2592 × 1944 pixel complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) detector array [4]. The on-axis pixel scale is 0.28 mrad/pixel. This translates into a 31 km nadir pixel spatial resolution for the NavCam 1 21:08:30 GMT image and a 37 km pixel resolution for the NavCam 2 22:16:38 GMT image. Earth was not centered but, instead, was positioned over many locations across the NavCam field of view (Figure 1a). The Earth disk encompasses ~390 × 390 and ~300 × 300 pixels for the first and last NavCam images taken, respectively. The silicon detector response is limited by a piece of coated fused silica, which provides a band spectral response function having a full width at half maximum between 0.4 µm and 0.7 µm. The detector array has a digitization rate of 12 bits. The flat-fielding of the CMOS array is very good, where the edge of the image has a relative radiance decrease of 1.1% compared to the center. The camera lens introduces barrel distortion at the corners of the field of view, which was measured during in-flight star-field calibrations to be 13.9%. The NavCam on-chip gain amplifier has a commandable gain setting between 1 and 7.75. The exposure time of all the NavCam 1 images and the first NavCam 2 image is 0.1528 milliseconds, and the exposures times of the second and third NavCam 2 images are 0.0764 and 0.3228 milliseconds, respectively.

2.2. GOES-15 Data

Four GOES-15 images acquired on 22 September 2017 were downloaded from the Man computer Interactive Data Access System (McIDAS) servers [18]. This data set includes the 21:00 (identified by the start time) GMT full disk (FD) scan, which ends at 21:22 GMT at the South Pole, and three Northern Hemisphere (NH) scans that start at 21:30, 22:00, and 22:30 GMT and terminate at the Equator 12 min later (Figure 1c). The GOES-15 imager has one visible channel (centered at 0.65 µm with a bandwidth of 0.2 µm) with a nominal pixel resolution of 1 km. The visible image is constructed by an eight-pixel detector array, which scans in the east–west direction and steps north-to-south [19]. The GOES-15 data are sub-sampled at a 4 km resolution by capturing only every fourth line and element. The GOES-15 FD and NH 4 km nominal images are 2705 × 5196 and 1355 × 3312 pixels, respectively.

The CERES ATO-RM calibration approach [13,20] references the GEO imagers to the radiometric scale of the Aqua-MODIS Collection 6.1 band 1 calibration. During OSIRIS-REx’s EGA maneuver, the calibration slope of the GOES-15 imager was computed to be 0.9041 Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1 with a 1-σ uncertainty of 1.1% based on ATO-RM. The space offset for GOES-15 imager was 29 DN [21]. The McIDAS software also provides the pixel-level navigation and GMT time for each scan line from which the viewing and solar geometry are computed.

2.3. DSCOVR EPIC Data

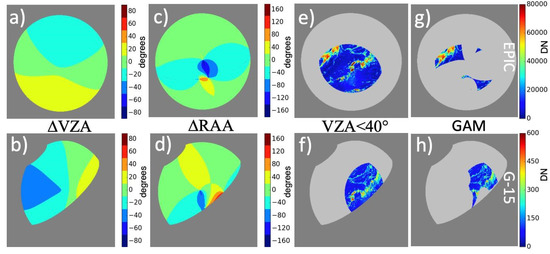

The DSCOVR EPIC version 2 L1b data were obtained from the NASA-Langley Atmospheric Science Data Center Distributed Active Archive Center (ASDC DAAC) [22]. Launched on 11 February 2015, the DSCOVR satellite reached its orbit at 1.5 million km away from Earth in the solar direction on 8 June 2015. The DSCOVR satellite orbits at the sun-Earth L1 Lagrangian position, allowing the EPIC imager to view the nearly complete sunlit disk of Earth [16]. The EPIC sensor views Earth between the backscattering angles of 168.5° and 175.5°. The EPIC image is constructed from a 2048 × 2048 charge-coupled device (CCD) array of detectors having a nominal pixel resolution of 18 km (Figure 1d) [23]. The EPIC sensor uses a filter wheel to observe the sunlit side of Earth in 10 visible bands. Band 7 (center wavelength of 680 nm with a 2-nm bandwidth) is used in this study. The EPIC pixel quantization rate is 12 bits, with a per-second photon measuring frequency. Two EPIC images acquired on 22 September 2017 at 20:53 GMT and 22:41 GMT were downloaded. The EPIC version 2 L1B images are not well navigated. The true and observed pixel center latitude and longitude typically differ by an average of 50 km [24]. The EPIC navigation was accounted for in Section 3, where the EPIC image is mapped into the NavCam image.

The EPIC calibration was based on the ATO calibration approach of Doelling et al. 2019 [24], which is very similar to the CERES GOES-15/MODIS ATO-RM approach. For 22 September 2017, the EPIC pixel level DN gain, gain uncertainty, and space offset DN were estimated to be 4.769 × 10−3 Wm−2sr−1µm−1(DN/sec)−1, 0.6%, and 0, respectively. The EPIC dataset provides the pixel-level navigation and angular geometry.

5. Results

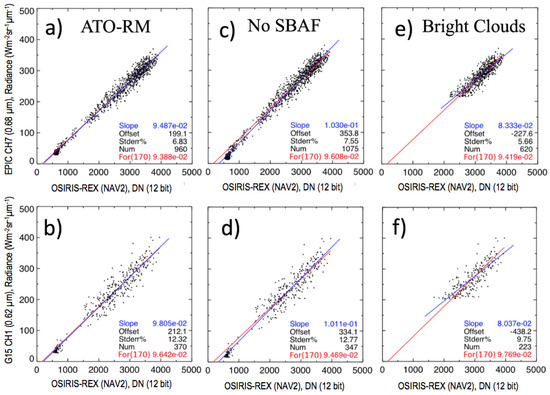

5.1. NavCam Calibration Table

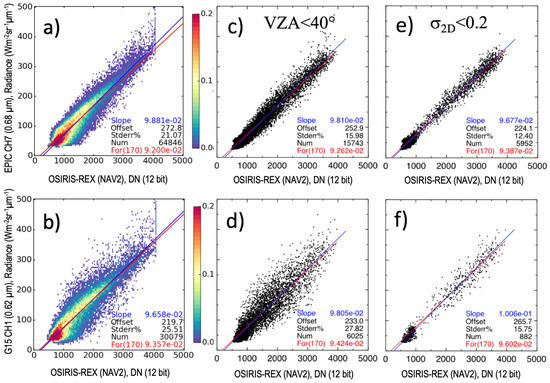

Table 1 contains the NavCam ATO-RM statistics. The first column lists times for the twelve out of twenty-three NavCam 1 images and all three NavCam 2 images that were calibrated. Not all NavCam 1 images could be matched with GEO images in both space and time. The second column contains the EPIC and GOES-15 image times that were matched with the NavCam images. The two NavCam 1 and EPIC matched images were 15 (row 1) and 25 (row 12) minutes apart. Ten NavCam 1 images (rows 2–11) were matched with three GOES-15 images and all matches were within 7 min. The first NavCam 2 image is listed twice (rows 13–14), because it was inter-calibrated with both EPIC and GOES-15 images. The last two NavCam 2 images (rows 15–16) were taken at different exposure times and were matched with the same GOES-15 NH image. The 3rd and 4th columns list the GAM thresholds. The next 3 columns list the force fit gains for ATO-RM, for ATO-RM for radiances >200, and for ATO-RM without SBAF. The next four columns contain the orthogonal regression standard error and x offset for ATO-RM and for ATO-RM without SBAF.

Table 1.

lists the individual NavCam image calibration gains. From left to right: The times in GMT in which the NavCam images calibrated in this study were taken on 22 September 2017. The NavCam 2 times are bold. The matched EPIC (E) or GOES-15 (FD, NH) image time is given in GMT. For GOES-15, the time is expressed at the equator. The GAM (VZA, RAA, SCAT) thresholds in degrees are given for the top half and 1st quartile radiances. Shown next are the NavCam gains (Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1) based on the ATO-RM (ATO), ATO-RM for radiances <200 Wm−2sr−1µm−1 (<200), and ATO-RM without SBAF applied (noSB). The ATO-RM and ATO-RM without SBAF (no SBAF) orthogonal regression standard errors (σ) are shown in percent and x-offsets (Off) in DN.

To assess the impact of angle matching tolerance on the NavCam 1 gains, the three GOES-15 images were matched with a sequence of NavCam 1 images, which were coincident within seven (rows 2–5), two (rows 6–8), and three (rows 9–11) minutes. The GAM angular thresholds were consistent for each sequence of NavCam 1 images. The top half angular thresholds were nearly the same; however, the 1st quartile angular thresholds were the most restrictive for the 22:05 GMT NH image (rows 9–11), less restrictive for the 21:13 GMT FD image (rows 2–5), and the least restrictive for the 21:35 GMT NH image (rows 6–8). The NavCam 1 gain standard deviations for each GOES-15 NH image are 0.2% (22:05 GMT, most restrictive), 0.5% (21:13 GMT, less restrictive), and 1.3% (21:35 GMT, least restrictive). As expected, increasing the angular threshold tolerance increases the uncertainty in the gain. The fact that the NavCam gains are consistent across a sequence of images and that the Earth was centered across various locations in the NavCam field of view suggests that the NavCam 1 CMOS flatfielding is very good.

To determine whether the angular thresholds were effective, the ATO-RM gains are compared to the top half radiance gains (>200), which have a more Lambertian reflection than ATO, for the ten GOES-15/NavCam 1 images (rows 2–11). The ATO-RM minus the ATO-RM top half (>200) gain was –0.4%, thus confirming adequate angle matching across the dynamic range. To evaluate the SBAF gain impact, the ATO-RM minus the ATO-RM no SBAF (noSB) gain was +1.5%. The NavCam 1 10-image average ATO-RM and ATO-RM no SBAF offsets were 164 and 278, respectively. The ATO-RM offset nearly equals the space DN of 170, which suggests that the application of SBAF when performing ATO-RM mitigated the spectral band differences. The NavCam 1 10-image average standard errors for ATO-RM and ATO-RM no SBAF are 12.0% and 12.7%, respectively. The consistency between the ATO and >200 gain, a regression offset that nearly equals the space DN, and the reduction of the standard error all indicate that both the SBAF and angular matching criteria were sufficient.

5.2. NavCam 2 Calibration Gains

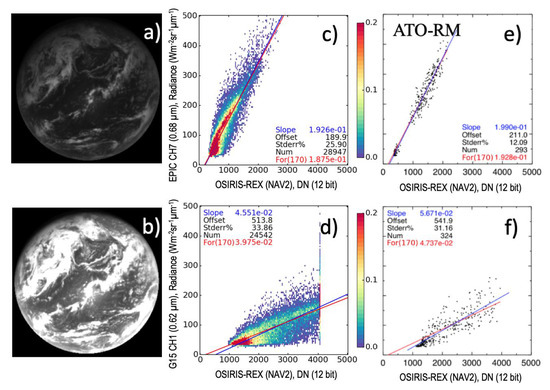

The last two NavCam 2 images provide an opportunity to assess the impact of the NavCam exposure time settings on the ATO-RM algorithm. Figure 7a,b display the last two NavCam 2 images and can be compared to the first NavCam 2 image shown in Figure 1b. The 3 NavCam 2 images were inter-calibrated with the same GOES-15 NH image. The pixel pair density plots reveal similar features as Figure 5b but are compressed (Figure 7c) or expanded (Figure 7d) across the NavCam DN axis. A total of 75% of the Figure 7b NavCam 2 image pixels are saturated.

Figure 7.

The (a) 22:43:33 GMT and (b) 22:43:41 GMT NavCam 2 images. The sensor exposure time of (a) is half that of Figure 1b and the exposure time of (b) is approximately twice that of Figure 1b. The NavCam 2 DN at 4095 are considered saturated. The (c) 22:43:33 GMT and (d) 22:43:41 GMT NavCam 2 DN and 22:30 GMT GOES-15 pixel radiance collocated pairs displayed as a relative density plot. The color bar units are in relative frequency. (e,f) Same as (c) and (d) except for the ATO-RM pairs. See Figure 5 for explanation of the upper left statistics.

The NavCam 2 pixel DN and GOES-15 radiance ATO-RM pairs are displayed in Figure 6b and Figure 7e,f. Figure 6b and Figure 7e have the GAM and σ2D thresholds applied, whereas Figure 7f simply splits the radiance range at 75 Wm−2sr−1µm−1 and applies a σ2D < 0.3. Figure 7e is very consistent with Figure 6b where the standard error and offset are nearly identical. The exposure time ratio for these two NavCam 2 images is 2 = 0.1528 × 10−3/0.0764 × 10−3 s. The Figure 7e and Figure 6b NavCam 2 force fit gain ratio is 1.9996, which is nearly identical to the exposure time ratio. The NavCam 2 saturated image lacks the bright cloud pairs and must exclusively rely on the 1st and 2nd quartile radiances, which require stricter angular matching but only broad angular matching is geometrically possible with this NavCam 2 and GOES-15 image configuration. The 1st quartile radiances are not sufficiently matched in angle and therefore do not intersect the force fit line, and the regression standard error was not significantly reduced with the ATO-RM thresholds. The force fit gain is a much better estimate than the slope gain, since it only solves for the gain rather than the gain and offset simultaneously, which may introduce bias in the gain [38]. For this case, the NavCam exposure time ratio is 0.473 = 0.3228 × 10−3/0.1528 × 10−3 and the ATO-RM force fit gain ratio is 0.491, which is within 3.9%. The NavCam ATO-RM force fit gains are able to provide consistent gains within 3.9% across exposure times of a factor of ± 2.

7. Comparison with Pre-Launch Calibration

Prior to launch, the radiance responsivities of the two NavCams were characterized at Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS) using an integrating sphere illuminated with a quartz-tungsten-halogen (QTH)–based broadband light source [4]. Due to the broad SRF of the NavCam imager, the pre-launch calibration was derived in terms of in-band radiance by integrating the sensor response over the pass band of the NavCam SRF. In addition, the pre-launch calibration coefficients are normalized by the mean exposure time to facilitate the radiometric comparison of NavCam images acquired at different exposure times. The pre-launch radiometric gains for NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 were estimated to be 100,965 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1) and 102,685 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1), respectively.

The in-flight calibration results based on the ATO method are compared with the pre-launch values to identify any temporal drift in the radiometric responsivity of NavCams after launch. The ATO-based radiometric gains of NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 are derived in the units of spectral radiance and are found to be 9.874 × 10−2 Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1 (Section 6) and 9.642 × 10−2 Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1 (Table row 14), respectively. These gains are multiplied by the equivalent width (343 nm) of the NavCam SRF to adjust to the units of in-band radiance [41]. By further normalizing these gain values by the imaging exposure time (0.1528 × 10−3 s), the ATO gains for NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 turn out to be 193,237 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1) and 197,886 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1), respectively. These numbers are significantly higher than the ground-based calibration.

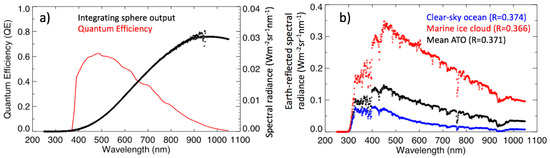

The integrated in-band response of an imaging sensor is dependent upon the illuminating spectra. Figure 8a shows the reference spectral radiance coming out of the exit port of the integrating sphere that was used for the pre-launch calibration. The reference spectra maximize at near-infrared wavelengths where the quantum efficiency (QE), plotted in red, of the NavCam imaging sensor is very small. On the other hand, the ATO-RM method utilizes the Earth-reflected solar spectra that have a peak in the visible part of the spectrum, where the QE also maximizes. To facilitate a direct comparison between the ground-based and in-flight calibration results, the difference in the two reference spectra must be taken into account. A correction factor is derived using the relative ratio (R) of the in-band sensor response to the total over pass band input radiance for each reference spectrum, as defined by the following equations:

where LSphere and LATO are the spectral radiance spectra at the integrating sphere output and the Earth-reflected ATO spectra, respectively, and QE is the quantum efficiency of the sensor. The integration is performed over the spectral range of the filter pass band. The value of RSphere is computed to be 0.198. The Earth-reflected ATO spectra are a combination of the clear-sky ocean and bright cloud targets. Figure 8b shows the top-of-atmosphere spectral radiance spectra of clear-sky ocean, marine ice cloud, and ATO scene conditions derived from SCIAMACHY footprints. It is interesting that the value of R is nearly the same (within 2%) for the clear-sky, marine ice cloud, and the combined ATO spectra. This is because the relative spectral distribution of the reflected solar energy is nearly the same for these scene types. So, the mean ATO spectrum is used for correction. The value of RATO is found to be 0.371. The NavCam 1 ATO gain after correcting for the difference in input spectra is, therefore, computed as:

RSphere = [∫LSphere(λ) × QE(λ) dλ]/[∫LSphere(λ) dλ]

RATO = [∫LATO(λ) × QE(λ) dλ]/[∫LATO(λ) dλ]

GainATO(NavCam 1) = 193,237 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1) × (RSphere/RATO) = 103,129 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1)

Figure 8.

(a) The spectral radiance output (black) from the integrating sphere and the QE plot (red). (b) Comparison of the clear-sky ocean, marine ice cloud, and ATO spectra.

The adjusted NavCam 1 and pre-launch gain differ by only 2.1%. Similarly, the NavCam 2 ATO calibration of 197,886 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1) is adjusted and found to be 105,610 (DN/s)/(Wm−2sr−1), which is consistent with the pre-launch gain within 2.8%. As a final check on the ground calibration, the ratio of the pre-launch NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 gains (0.9833) was compared with the ATO-RM gain ratio (0.9765) and was found to be within 0.7%. The consistent pre-launch and on-orbit NavCam gains denote a stable performing sensor, while in space.

8. Conclusions

The Earth-viewed OSIRIS-REx NavCam images captured during an EGA maneuver provided an opportunity to validate the NavCam pre-launch ground-based calibration. GOES-15 and DSCOVR-EPIC imager radiances were found most suitable to inter-calibrate the NavCam images. First the GOES-15 and EPIC pixel-level radiances were mapped to the EPIC field of view. An optimized ATO-RM inter-calibration algorithm accounted for spectral band differences, navigation errors, radiance field changes due to the time matching difference, and angular geometry differences by incorporating SBAFs, spatial homogeneity tests, and radiance stratified angle matching thresholds.

Twelve NavCam 1 images were inter-calibrated with two EPIC and three GOES-15 images, which were first radiometrically scaled to the Aqua-MODIS reference calibration. The GOES-15 reference radiances were considered more accurate than the EPIC reference radiances, owing to the large EPIC navigation error, exceptionally narrow SRF, and greater matching time difference. After radiometrically scaling the EPIC radiances to GOES-15, the NavCam 1 mean gain is 9.874 × 10−2 Wm−2sr−1µm−1DN−1 ± 1.8%. After accounting for known uncertainties in the NavCam ATO-RM algorithm, the total gain uncertainty is estimated at 3.7%. The ATO-RM orthogonal regression offset of 164 is close to the true space DN of 170. When strict angular matching thresholds are possible between multiple NavCam 1 and two matched GOES-15 images, the standard deviation of the ATO-RM NavCam gains were within 0.2%–0.5%, suggesting that the NavCam 1 CMOS detector flatfielding is very good. The ATO-RM calibration was able to provide gains that are consistent within 3.9% across a factor of ±2 exposure times. The ATO-RM calibration method can be verified by using both GOES-15 and EPIC to independently transfer the Aqua-MODIS reference calibration to NavCam 2 and the resulting gains were consistent within 2.6%.

The ATO-RM NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 gains were compared with the pre-launch gains. The pre-launch gains were based on using an integrating sphere and a QTH lamp. After accounting for the difference of the solar and lamp spectra, the pre-launch and ATO-RM NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 gains were within 2.1%–2.8%. The estimated ATO-RM gain uncertainty was 3.7%, indicates that the pre-launch and the ATO-RM gain difference is less than what can be significantly resolved using the ATO-RM calibration method. Finally, the NavCam 1 and NavCam 2 calibration gain ratios based on ATO-RM and pre-launch were within 0.7% of each other, indicating consistent NavCam 1 and 2 optical performance while in space. The ATO-RM calibration results verify that the on-orbit NavCam calibration gain is very similar to the pre-launch gain, indicating that no significant NavCam performance changes have occurred during space flight.

This work provides an independent, in-flight absolute radiometric calibration of NavCam 1 and 2. This aided the NavCam exposure time planning for Bennu observations. The small 3% radiometric uncertainty we found also benefits asteroid analyses that rely on absolute radiometric information in NavCam imagery. For example, NavCam images of Bennu provide an independent measurement of the body’s albedo, in concert with the other imagers onboard the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft. It also informs how accurately we can estimate from NavCam images the sizes of unresolved particles ejected from Bennu’s surface. Size measurements of these objects has become important to the OSIRIS-REx mission since their first detection in January 2019 [5].

This study has demonstrated that images of the sunlit Earth disk taken during an EGA maneuver by a solar-system probe, such as OSIRIS-REx, can be inter-calibrated using Earth-orbiting imagers. Due to the limited number of NavCam images and coarse pixel resolution, geostationary imagers are the most suited sensors for this task. The GEO imagers operationally scan at least every half hour and the most current sensors scan a full disk every 15 min. The current constellation of GEO satellites provides contiguous imagery across Earth, which offers inter-calibration opportunities no matter where the probe observes, except over the poles, where GEO satellite views are not possible.

Author Contributions

D.D. formulated and directed the methodology, validation, results analysis, and prepared the manuscript. K.K. referenced the NavCam 1 images with respect to Earth coordinates, mapped and aligned the EPIC and GOES-15 images into the NavCam 1 field of view. C.H. processed, plotted, and analyzed all of the NavCam, GOES-15, and EPIC images. R.B. scaled the NavCam pre-launch and satellite inter-calibration gains. B.B. processed the NavCam images and provided and interpreted the pre-launch NavCam results. B.S. and A.G. determined the SBAF. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by NASA under Contract NNM10AA11C issued through the New Frontiers Program.

Acknowledgments

TAGCAMS images are available via the Planetary Data System (PDS) (https://sbn.psi.edu/pds/resource/orex/) [17]. This study was supported by NASA ROSES proposal NNH14ZDA001N-DSCOVR.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- “OSIRIS-REx Factsheet” (PDF). NASA/Explorers and Heliophysics Projects Division. Available online: https://ehpd.gsfc.nasa.gov/documents/552572main_OSIRIS_REx_Factsheet.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- “OSIRIS-REx The Mission”. Available online: https://www.asteroidmission.org/mission/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Lauretta, D.S.; Balram-Knutson, S.S.; Beshore, E.; Boynton, W.V.; Drouet D’Aubigny, C.; DellaGiustina, D.N.; Enos, H.L.; Golish, D.R.; Hergenrother, C.W.; Howell, E.S.; et al. OSIRIS-REx: Sample return from asteroid (101955) Bennu. Space Sci. Rev. 2017, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, B.J.; Ravine, M.A.; Caplinger, M.; Schaffner, J.A.; Ladewig, J.V.; Olds, R.D.; Norman, C.D.; Huish, D.; Hughes, M.; Anderson, S.K.; et al. Touch and Go Camera System (TAGCAMS) for the OSIRIS-REx Asteroid Sample Return Mission Space. Sci. Rev. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauretta, D.S.; Hergenrother, C.W. Episodes of particle ejection from the surface of the active asteroid (101955) Bennu. Science. in press. [CrossRef]

- Heidinger, A.K.; Cao, C.; Sullivan, J. Using Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (MODIS) to calibrate Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) reflectance channels. J. Geophys. Res. 2002, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Weinreb, M.; Xu, H. Predicting Simultaneous Nadir Overpasses among Polar-Orbiting Meteorological Satellites for the Intersatellite Calibration of Radiometers. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2004, 21, 537–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Doelling, D.R.; Scarino, B.R.; Gopalan, A.; Haney, C.O.; Minnis, P.; Bedka, K.M. A consistent AVHRR visible calibration record based on multiple methods applicable for the NOAA degrading orbits, Part I: Methodology. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33, 2499–2515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelling, D.R.; Bhatt, R.; Scarino, B.R.; Gopalan, A.; Haney, C.O.; Minnis, P.; Bedka, K.M. A consistent AVHRR visible calibration record based on multiple methods applicable for the NOAA degrading orbits, Part II: Validation. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33, 2517–2534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidinger, A.K.; Straka, W.C., III; Molling, C.C.; Sullivan, J.T. Deriving an inter-sensor consistent calibration for the AVHRR solar reflectance data record. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2010, 31, 6493–6517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Xue, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guang, J.; He, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, T.; Liu, X. Post calibration of channels 1 and 2 of long-term AVHRR data record based on SeaWiFS data and pseudo invariant targets. Remote Sens. Environ. 2014, 150, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, A.; Xiong, X.; Angal, A. Deriving a MODIS-based calibration for the AVHRR reflective solar channels of the NOAA KLM operational satellites. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 1405–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelling, D.; Haney, C.; Bhatt, R.; Scarino, B.; Gopalan, A. Geostationary Visible Imager Calibration for the CERES SYN1deg Edition 4 Product. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, A.K.; Knapp, K.R. Intercomparison of Independent Calibration Techniques Applied to the Visible Channel of the ISCCP B1 Data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2015, 32, 1225–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meirink, J.F.; Roebeling, R.A.; Stammes, P. Inter-calibration of polar imager solar channels using SEVIRI. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2013, 6, 2495–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshak, A.J.; Herman, S.; Adam, B.; Karin, S.; Carn, A.; Cede, I.; Geogdzhayev, D.; Huang, L.; Huang, Y.; Knyazikhin, M. Earth Observations from DSCOVR EPIC Instrument. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2018, 99, 1829–1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, B.; Jackman, C.; Lauretta, D.S. Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer (OSIRIS-REx): Touch-and-Go Camera Suite (TAGCAMS) Bundle, urn:nasa:pds:orex.tagcams, NASA Planetary Data System. 2019. Available online: https://pds.nasa.gov/datasearch/subscription-service/SS-20190630.shtml (accessed on 12 November 2019).

- Lazzara, M.A.; Benson, J.M.; Fox, R.J.; Laitsch, D.J.; Rueden, J.P.; Santek, D.A.; Wade, D.M.; Whittaker, T.M.; Young, J.T. The Man computer Interactive Data Access System: 25 years of interactive processing. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 1999, 80, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinreb, M.; Jamieson, M.; Fulton, N.; Chen, Y.; Johnson, J.-X.; Bremer, J.; Smith, C.; Baucom, J. Operational calibrationof Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-8 and -9 imagers and sounders. Appl. Opt. 1997, 36, 6895–6904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CERES Edition 4 Calibration Coefficients. Available online: https://satcorps.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/site/showdoc?mnemonic=CALIB-ED4 (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- CERES Updated Realtime GEO Calibration. Available online: https://satcorps.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/site/showdoc?mnemonic=CALIB-UPRT# (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- DSCOVR Earth Sensors Science Team: DSCOVR EPIC Level 1B Dataset. Available online: https://eosweb.larc.nasa.gov/project/dscovr/dscovr_epic_l1b_2 (accessed on 21 November 2018).

- Geogdzhayev, I.V.; Marshak, A. Calibration of the DSCOVR EPIC visible and NIR channels using MODIS Terra and Aqua data and EPIC lunar observations. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2018, 11, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelling, D.; Haney, C.; Bhatt, R.; Scarino, B.; Gopalan, A. The Inter-Calibration of the DSCOVR EPIC Imager with Aqua-MODIS and NPP-VIIRS. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2014: NOAA KLM User’s Guide, Appendix I. Available online: https://www1.ncdc.noaa.gov/pub/data/satellite/publications/podguides/N-15 thru N-19/pdf/ (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Khlopenkov, K.V.; Trishchenko, A.P. Implementation and Evaluation of Concurrent Gradient Search Method for Reprojection of MODIS Level 1B Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 2016–2027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopenkov, K.V.; Trishchenko, A.P. Achieving Subpixel Georeferencing Accuracy in the Canadian AVHRR Processing System. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2010, 48, 2150–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khlopenkov, K.; Doelling, D.; Okuyama, A. MTSAT-1R visible imager point spread function correction, Part II: Theory. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chander, G.N.; Mishra, N.; Helder, D.L.; Doelling, D.R.; Aaron, D.B.; Angal, A.; Choi, T.; Xiong, X. Applications of spectral band adjustment factors (SBAF) for cross-calibration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2013, 51, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spectral Response Function Database. Available online: https://satcorps.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/site/showdoc?docid=194&c=home2 (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Bovensmann, H.; Burrows, J.P.; Buchwitz, M.; Frerick, J.; Noël, S.; Rozanov, V.V.; Chance, K.V.; Goede, A.P.H. SCIAMACHY: Mission objectives and measurement modes. J. Atmos. Sci. 1999, 56, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarino, B.D.; Doelling, R.; Gopalan, A.; Chee, T.; Bhatt, R.; Haney, C. Enhancements to the open access spectral band adjustment factor online calculation tool for visible channels. Proc. SPIE 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarino, B.R.; Doelling, D.R.; Minnis, P.; Gopalan, A.; Chee, T.; Bhatt, R.; Lukashin, C.; Haney, C.O. A Web-Based Tool for Calculating Spectral Band Difference Adjustment Factors Derived From SCIAMACHY Hyperspectral Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GOES-8 through GOES-15 Imager Spectral Response Functions. Available online: https://www.ospo.noaa.gov/Operations/GOES/goes-imager-srfs.html (accessed on 6 November 2019).

- Herman, J.; Huang, L.; McPeters, R.; Ziemke, J.; Cede, A.; Blank, K. Synoptic ozone, cloud reflectivity, and erythemal irradiance from sunrise to sunset for the whole earth as viewed by the DSCOVR spacecraft from the earth–sun Lagrange 1 orbit. Atmos. Meas. Technol. 2018, 11, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wielicki, B.A.; Doelling, D.R.; Young, D.F.; Loeb, N.G.; Garber, D.P.; MacDonnell, D.G. Climate quality broadband and narrowband solar reflected radiance calibration between sensors in orbit. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2008 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Boston, MA, USA, 7–11 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Doelling, D.R.; Haney, C.O.; Scarino, B.R.; Gopalan, A.; Bhatt, R. Improvements to the geostationary visible imager ray-matching calibration algorithm for CERES Edition 4. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2016, 33, 2679–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, A.; Cao, C.; Sullivan, J.; Levin, R.; Wu, X.; Galvin, R. The usefulness of in-flight measurements of space count to improve calibration of the AVHRR solar reflectance bands. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2005, 22, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X. MODIS Reflective Solar Calibration and Uncertainty Assessment. Available online: http://gsics.atmos.umd.edu/pub/Development/20110322/Day2pm_GRWG_Xiong_MODIS.pdf (accessed on 26 August 2019).

- Doelling, D.R.; Wu, A.; Xiong, X.; Scarino, B.R.; Bhatt, R.; Haney, C.O.; Morstad, D.; Gopalan, A. The radiometric stability and scaling of collection 6 Terra- and Aqua-MODIS VIS, NIR, and SWIR spectral bands. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2015, 53, 4520–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solar Constants Comparison. Available online: https://satcorps.larc.nasa.gov/cgi-bin/site/showdoc?mnemonic=SOLAR-CONSTANT-COMPARISONS (accessed on 26 August 2019).

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).