Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation

Abstract

1. Introduction

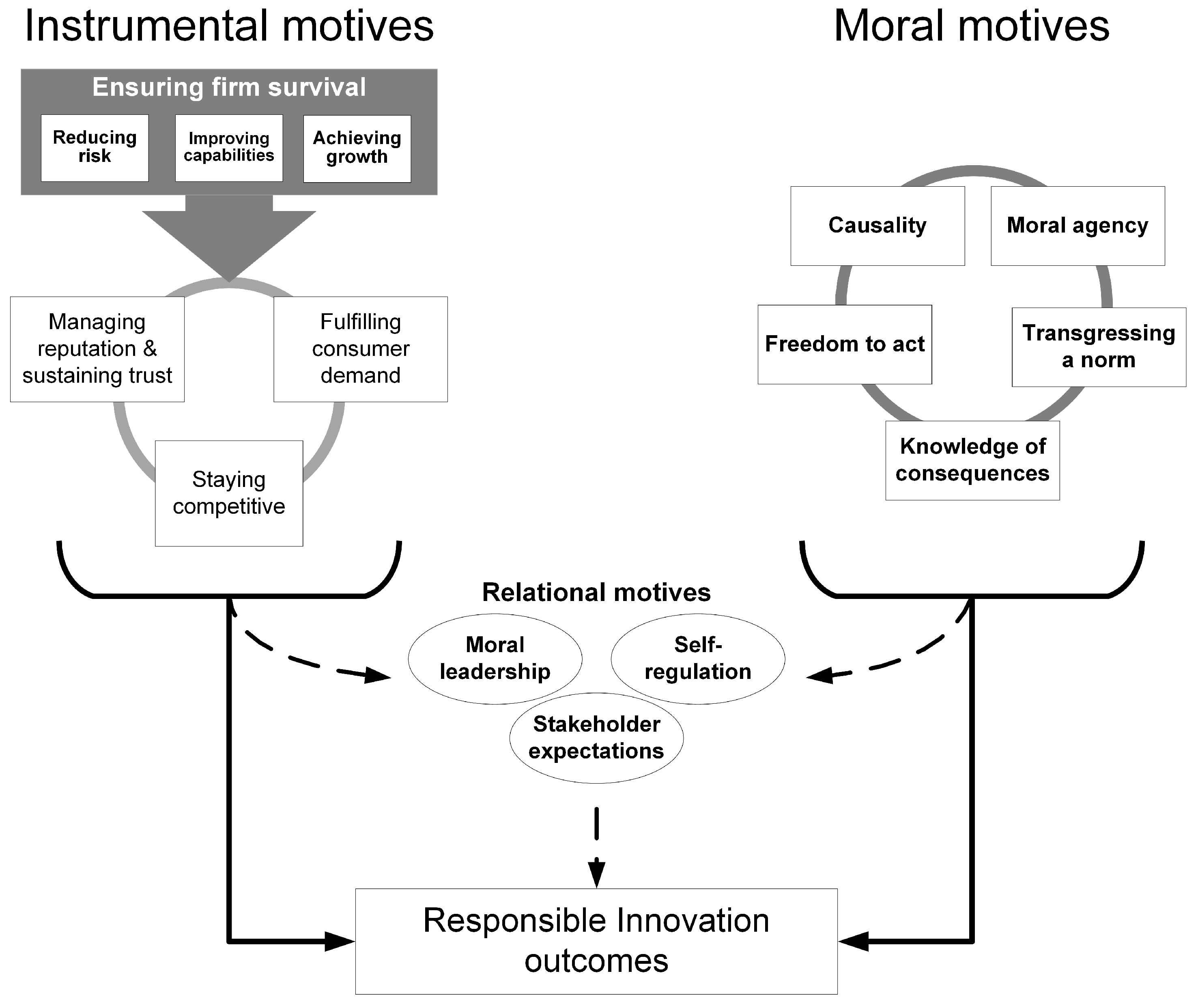

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Instrumental Motives

2.2. Moral Motives

2.3. Relational Motives

2.4. CSR Motives and Innovation Practices

3. Method and Materials

3.1. Context and Case Selection

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

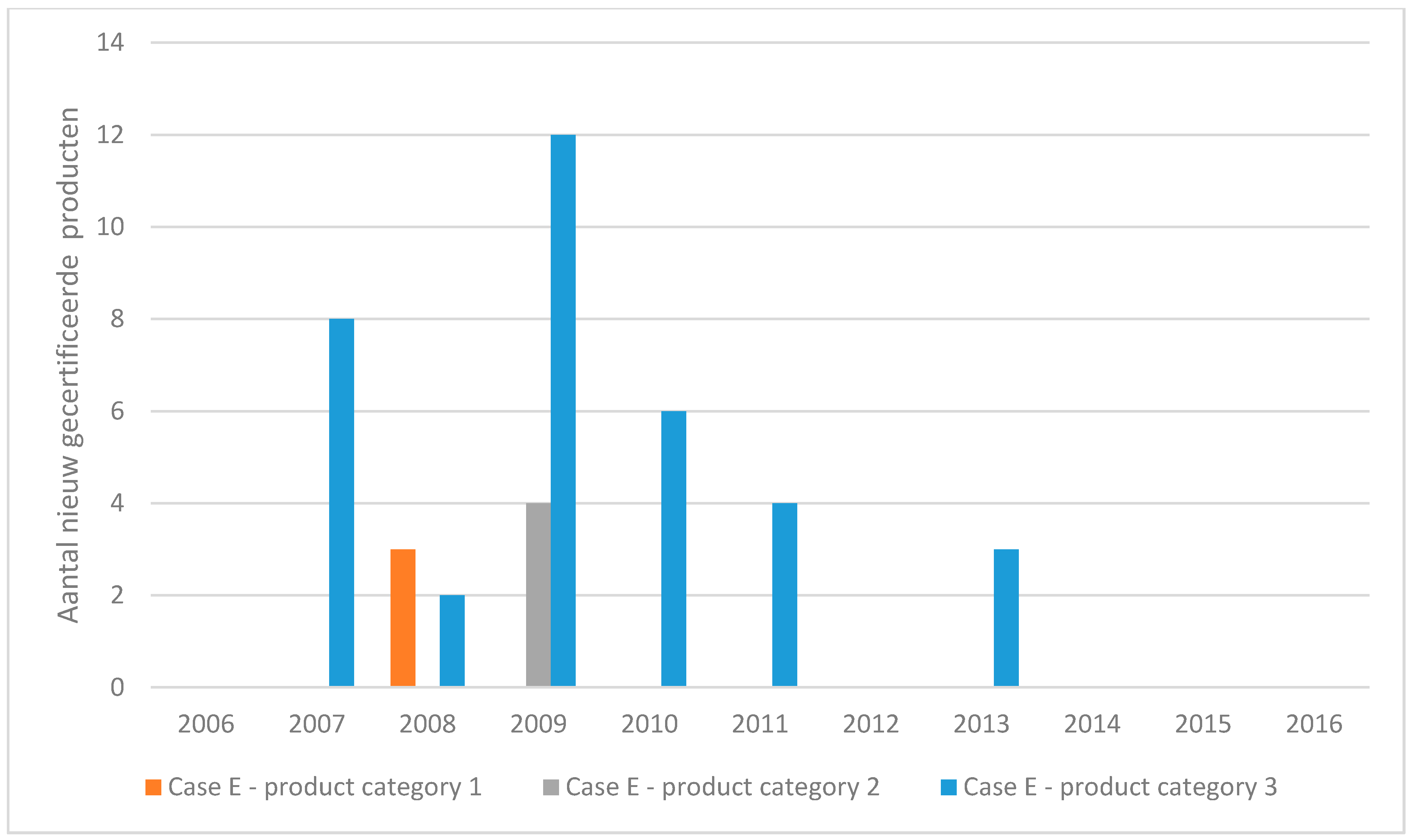

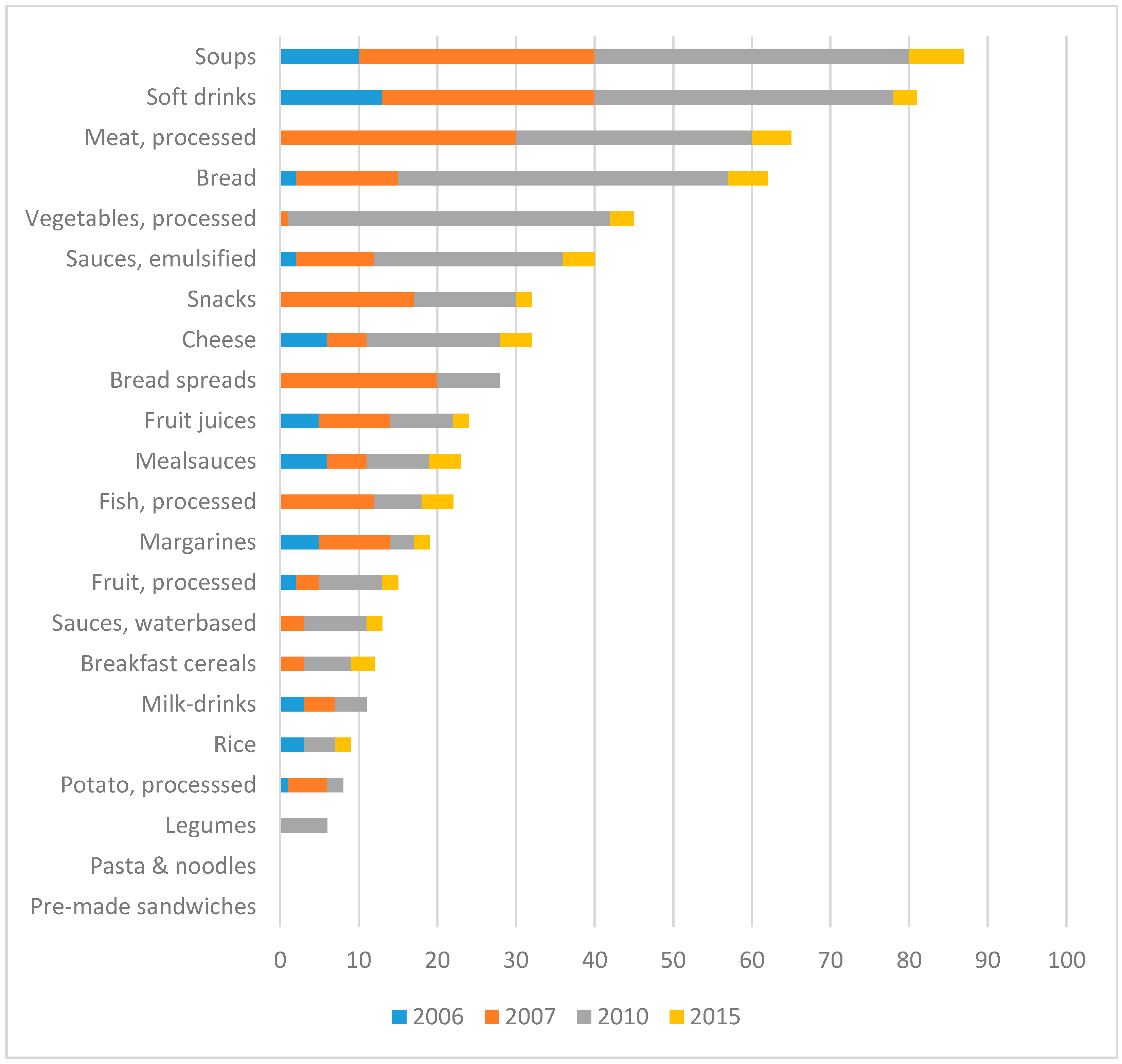

4.1. Results of Quantitative Data Analyses

4.2. Findings on Instrumental Motives

| “Innovation is one of the cornerstones of [firm name]’s strategy of sustained growth and added value.” (Case C) |

4.3. Findings on Moral Motives

| “... and the consumer just has a need. And we have a responsibility. So we look at what is going on among consumers and that [ed. health] is therefore also a topic.” (Case E) |

| “[About dialogue with health agency] but is more like the door half closed, saying ‘It is on our website and good luck with it’. So you [the firm] can really want it, and we do want it, only the question is about the other party, you know... You are still seen as a commercial party.” (Case D) |

4.4. Findings on Relational Motives

4.5. Motives during Product Innovation

| “And we lose our customers, which is not nice because we want to make money with our products. But you also lose your health gain, if your people [consumers] get back to a product with a higher sugar content.” (Case C) |

| “Because sometimes we do have some outliers. Those products we think are very good. [Product name] is a good example. That one is certainly not healthy, but it is our best sold item.” (Case H) |

| “As category or portfolio manager you know: ‘Yes, I will make negative margin on that product, but then I’ll just have to compensate this with another similar product.” (Case A) |

| “Two years ago in a meeting with a marketing director over there, she said: ‘Yes, but in Russia we will never work on sugar reduction, because it is not an issue here’. And now they are making steps in their recipes, they are reducing in steps. So that is a change.” (Case C) |

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Company | Interviewees | Secondary Sources | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case A | Quality Manager Policy Officer | 7 | (1 Corporate report; 6 CSR reports) |

| Case B | Quality manager | 11 | (2 Codes of conduct; 1 Corporate report; 8 CSR reports) |

| Case C | R&D manager Nutrition Communication manager | 11 | (3 Corporate reports; 3 CSR reports; 5 webpages) |

| Case D | Marketing manager | 9 | (2 Codes of conduct; 7 webpages) |

| Case E | Marketing manager | 1 | (1 webpage) |

| Case F | Two marketing managers | 9 | (2 Codes of conduct; 2 CSR reports; 5 webpages) |

| Case G | Marketing & Sales director Marketing Manager R&D manager | 5 | (3 Corporate reports; 2 webpages) |

| Case H | Marketing & sales manager | 4 | (2 CSR reports; 2 webpages) |

Appendix B

| Product Category | Potato, Processed | Sandwiches, Pre-Made | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | . | 0 | 0 | - | - | 13 | 13 | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 0 | 7 | - | - | 8 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2 | - | - | 2.2 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | 13 | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - | - | 0.15 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - | - | 0.8 | 0.8 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | 1 | - | - | 1.8 | - | - | - | 1.4 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 120 | 100 | 100 | - | - | - | 450 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | - |

| Product category | Bread | Bread spreads | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | . | . | 350 | 350 |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | 13 | 13 | - | - | 13 | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 4 | 7 | - | 30 | 30 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | - | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2 | - | - | 4 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | 2 | 13 | 13 | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | - | - | - | 0.3 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | 5 | - | - | 3.1 | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 500 | 500 | 450 | - | - | 400 | 400 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | 1.6 | 1.6 | - | - |

| Product category | Soft drinks | Fruits, processed | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | 32 | 30 | 27 | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | . | . | . |

| Added sugar (energy %) | . | - | - | - | . | 0 | . | . |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | - | 7 | . | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 120 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 120 | 200 | 200 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Product category | Vegetables, processed | Margarines | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | 0 | - | - | - | 0 | 0 | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | 2.5 | 2.5 | 7 | - | - | 0 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | - | - | - | 28 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | 33 | 30 | 30 | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2 | - | - | 1.2 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | 100 | 120 | 200 | 200 | - | - | 160 | 160 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | - | - | - | - | 1.6 | 1.6 | - | - |

| Product category | Cheese | Meal sauces | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | 0 | 0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 0 | 7 | 3.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 18 | 15 | 16 | 14 | 4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | - | - | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | 900 | 900 | 900 | 820 | 540 | 450 | 450 | 450 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Product category | Milk-based drinks | Breakfast cereals | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 3.25 | 20 | 20 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | - | 1.4 | 3 | 3 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | - | - | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | 5 | - | - | 6 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 120 | 100 | 100 | - | 120 | 500 | 400 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| Product category | Pasta & noodles | Legumes | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | 0 | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 0 | 7 | - | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - | - | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | 1 | - | - | 2.7 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 120 | 100 | 100 | - | 120 | 200 | 200 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| Product category | Rice | Sauces, emulsified | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | 350 | 350 | 330 |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | 0 | 0 | - | - | 13 | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 0 | 7 | - | 11 | 11 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | - | - | - | 3 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | 33 | 30 | 30 | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | - | - | - | 0.35 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | 1.3 | 0.7 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | 1 | - | - | 1.4 | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 120 | 100 | 100 | 1080 | 750 | 750 | 725 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Product category | Sauces, water-based | Snacks | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | 100 | 100 | 330 | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | - | - | 11 | 7 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 3 | 2 | - | - | 6 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | 33 | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | 13 | 13 | 13 | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.35 | 0.2 | - | - | 0.2 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | 2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | 1080 | 750 | 750 | 725 | 100 | 400 | 400 | 400 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | - | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| Product category | Soups | Fish, processed | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | - | - | - |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | 3.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 7 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 5 | - | - | 4 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 30 | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | 360 | 350 | 350 | 330 | - | 450 | 450 | 400 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | - | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

| Product category | Meat, processed | Fruit juices | ||||||

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | 2015 |

| Energy (kcal/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 50 | 50 |

| Total sugar (energy %) | 25 | - | - | - | 25 | - | - | - |

| Added sugar (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0 | - |

| Added sugar (g/100 g) | 7 | 3.25 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 7 | 0 | - | 0 |

| Saturated fat (g/100 g) | 5 | - | - | 5 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| Saturated fat (% total fat) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Saturated fat (energy %) | - | 13 | 13 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Trans fat (g/100 g) | 0.2 | - | - | - | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Trans fat (energy %) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Fibre (g/100 kcal) | - | - | - | - | - | 0.75 | 0.75 | . |

| Fibre (g/100 g) | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.3 |

| Sodium (mg/100 g) | - | 900 | 900 | 820 | - | 120 | 100 | 100 |

| Sodium (mg/kcal) | 1.6 | - | - | - | 1.6 | - | - | - |

Appendix C. Interview Guide

- 1.

- Could you explain what your role is within the product innovation process within your firm?

- a.

- Role in decision making?

- 2.

- What is, according to the vision of your firm, the role of your firm in the supply of a healthy daily diet?

- a.

- Why is this the role of your firm?

- b.

- Is this role particular for your firm?

- c.

- What main activities are part of this role?

- 3.

- To which health themes does your firm pay attention?

- a.

- Why these themes?

- b.

- How does your firm recognize and select these themes?

- c.

- Which knowledge is required to recognize these themes?

- d.

- Have these themes changed over the last 10 years? If so, why?

- 4.

- In which way do these health themes influence the product development in your firm?

- a.

- Are they translated to guidelines or procedures? How?

- b.

- Why are these themes important for product development?

- c.

- Which knowledge is required to implement these themes?

- d.

- Which factors or organizations influence this implementation?

- e.

- Has the impact of these themes changed over the years? If so, why?

- 5.

- Within your firm, how is decided if health guidelines are applicable to a new product?

- a.

- When is this decision made during the innovation process?

- b.

- What are the considerations during this decision?

- c.

- Which factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- d.

- Which knowledge is required for this decision?

- 6.

- Within your firm, how is decided if health guidelines are applicable to the reformulation of an existing product?

- a.

- When is this decision made during the innovation process?

- b.

- What are the considerations during this decision?

- c.

- Which factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- d.

- Which knowledge is required for this decision?

- 7.

- How are the health requirements incorporated in the development of new products?

- a.

- What is their role in the decision making process?

- b.

- What are the considerations for including them?

- c.

- Which factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- d.

- What factors hinder compliance with the health requirements?

- e.

- What knowledge is required to overcome these barriers?

- 8.

- How are health requirements included in the reformulation process?

- a.

- What is their role in the decision making process?

- b.

- What are the considerations for including them?

- c.

- Which factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- d.

- What factors hinder compliance with the health requirements?

- e.

- What knowledge is required to overcome these barriers?

- 9.

- Do the health requirements play a role in the launch of a new product?

- a.

- When are the health requirements communicated to the consumer?

- b.

- How is this decision made?

- c.

- What are the considerations for this decision?

- d.

- What factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- e.

- What knowledge is required for making this decision?

- 10.

- Do the health requirements play a role in the launch of a reformulated product?

- a.

- When are the health requirements communicated to the consumer?

- b.

- How is this decision made?

- c.

- What are the considerations for this decision?

- d.

- What factors or external organizations influence this decision?

- e.

- What knowledge is required for making this decision?

- 11.

- What is the role of the health requirements in the evaluation of the success of a product?

- a.

- What are the considerations for the decision to include them?

- b.

- How are health requirements of the product evaluated?

- c.

- What knowledge is required for this evaluation?

- d.

- What factors or external organizations are included in this evaluation?

- e.

- How is the result of this evaluation communicated and taken up within the firm?

- 12.

- What is the role of the health requirements in the evaluation of the success of a reformulation?

- a.

- What are the considerations for the decision to include them?

- b.

- How are health requirements of the reformulation evaluated?

- c.

- What knowledge is required for this evaluation?

- d.

- What factors or external organizations are included in this evaluation?

- e.

- How is the result of this evaluation communicated and taken up within the firm?

- 13.

- How does your firm respond to negative feedback from society on the nutritional value of its products?

- a.

- What are the considerations in deciding on a response?

- b.

- What factors or external organizations influence this decision?

References

- Maloni, M.J.; Brown, M.E. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Supply Chain: An Application in the Food Industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 68, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestle, M. Food Politics: How the Food Industry Influences Nutrition and Health, Revised and Expanded ed.; California Studies in Food and Culture; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0-520-25403-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stuckler, D.; Nestle, M. Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health. PLoS Med. 2012, 9, e1001242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckel, R.H.; Borra, S.; Lichtenstein, A.H.; Yin-Piazza, S.Y. Understanding the Complexity of Trans Fatty Acid Reduction in the American Diet: American Heart Association Trans Fat Conference 2006: Report of the Trans Fat Conference Planning Group. Circulation 2007, 115, 2231–2246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mensink, R.P.; Katan, M.B. Effect of Dietary Trans Fatty Acids on High-Density and Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Levels in Healthy Subjects. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323, 439–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council Regarding Trans Fats in Foods and in the Overall Diet of the Union Population; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. A Three-Dimensional Conceptual Model of Corporate Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1979, 4, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M.B.E. A Stakeholder Framework for Analyzing and Evaluating Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crane, A.; Matten, D. Framing Business Ethics. In Business Ethics: Managing Corporate Citizenship and Sustainability in the Age of Globalization; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 2007; Chapter 2; ISBN 978-0-19-928499-3. [Google Scholar]

- Scalet, S.; Kelly, T.F. CSR Rating Agencies: What is Their Global Impact? J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 94, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. OECD Overview of Selected Initiatives and Instruments Relevant to Corporate Social Responsibility. In Annual Report on the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2008; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2009; pp. 235–260. ISBN 978-92-64-01495-4. [Google Scholar]

- Global Reporting Initiative GRI Standards. 2016. Available online: https://www.globalreporting.org/standards/gri-standards-download-center/?g=ca465426-c98e-4b63-9d40-284e0454150e (accessed on 22 November 2017).

- Fortanier, F.; Kolk, A.; Pinkse, J. Harmonization in CSR Reporting. Manag. Int. Rev. 2011, 51, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, R.V.; Rupp, D.E.; Williams, C.A.; Ganapathi, J. Putting the S back in corporate social responsibility: A multilevel theory of social change in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2007, 32, 836–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. From Issues to Actions: The Importance of Individual Concerns and Organizational Values in Responding to Natural Environmental Issues. Organ. Sci. 2003, 14, 510–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemingway, C.A.; Maclagan, P.W. Managers’ personal values as drivers of corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Roth, K. Why Companies Go Green: A Model of Ecological Responsiveness. Acad. Manag. J. 2000, 43, 717–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Shabana, K.M. The Business Case for Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of Concepts, Research and Practice. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 85–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.J.; Primo, D.M.; Richter, B.K. Using item response theory to improve measurement in strategic management research: An application to corporate social responsibility: An Application to Corporate Social Responsibility. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Measuring Corporate Social Performance: A Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2010, 12, 50–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A.; Moon, J. Corporate Responsibility for Innovation—A Citizenship Framework. In Business Ethics of Innovation; Hanekamp, G., Wütscher, F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; pp. 63–87. ISBN 978-3-540-72310-3. [Google Scholar]

- Pujari, D. Eco-innovation and new product development: Understanding the influences on market performance. Technovation 2006, 26, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennings, K. Redefining innovation—Eco-innovation research and the contribution from ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2000, 32, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stilgoe, J.; Owen, R.; Macnaghten, P. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1568–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Schomberg, R. Towards Responsible Research and Innovation in the Information and Communication Technologies and Security Technologies Fields: [Presentations Made at a Workshop Hosted by the Scientific and Technological Assessment Unit of the European Parliament in November 2010]; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2011; ISBN 978-92-79-20404-3. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, R.; Stilgoe, J.; Macnaghten, P.; Gorman, M.; Fisher, E.; Guston, D. A Framework for Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J.R., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2013; Chapter 2; pp. 27–50. ISBN 978-1-119-96636-4. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes, K.; Macnaghten, P. Responsible Innovation—Opening Up Dialogue and Debate. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J.R., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2013; Chapter 5; pp. 85–107. ISBN 978-1-119-96636-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stirling, A. “Opening Up” and “Closing Down”: Power, Participation, and Pluralism in the Social Appraisal of Technology. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 2007, 33, 262–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Lemmens, P. The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation. Three Reasons Why It Is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation. In Responsible Innovation 2; Koops, B.-J., Oosterlaken, I., Romijn, H., Swierstra, T., Van den Hoven, J., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 19–35. ISBN 978-3-319-17307-8. [Google Scholar]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R.; Pavitt, K. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; ISBN 978-0-470-09326-9. [Google Scholar]

- Chatfield, K.; Iatridis, K.; Stahl, B.; Paspallis, N. Innovating Responsibly in ICT for Ageing: Drivers, Obstacles and Implementation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krefting, L. Rigor in qualitative research: The assessment of trustworthiness. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1991, 45, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windolph, S.E.; Harms, D.; Schaltegger, S. Motivations for Corporate Sustainability Management: Contrasting Survey Results and Implementation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2014, 21, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stichting Ik Kies Bewust—Het Vinkje. Available online: https://www.hetvinkje.nl/organisatie/stichting-ik-kies-bewust/ (accessed on 27 November 2017).

- Basu, K.; Palazzo, G. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Process Model of Sensemaking. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vidaver-Cohen, D. Corporate Motives for Social Initiative: Legitimacy, Sustainability, or the Bottom Line? J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 87, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardberg, N.A.; Fombrun, C.J. Corporate Citizenship: Creating Intangible Assets across Institutional Environments. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 329–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; Mazereeuw, C. Motives for Corporate Social Responsibility. Economist 2012, 160, 377–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits. The New York Times Magazine, 13 September 1970; 32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kurucz, E.C.; Colbert, B.A.; Wheeler, D. The business case for Corporate Social Responsibility. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility; Crane, A., McWilliams, A., Matten, D., Moon, J., Siegel, D.S., Eds.; Oxford Handbooks; Oxford University Press Inc.: Oxford, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-19-921159-3. [Google Scholar]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate Social Performance Revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margolis, J.D.; Walsh, J.P. People and Profits? The Search for a Link between a Company’s Social and Financial Performance; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 2001; ISBN 1-135-64227-3. [Google Scholar]

- Orlitzky, M.; Schmidt, F.L.; Rynes, S.L. Corporate Social and Financial Performance: A Meta-Analysis. Organ. Stud. 2003, 24, 403–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Murrell, A.J. Revisiting the corporate social performance-financial performance link: A replication of Waddock and Graves: Revisiting the Corporate Social Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2016, 37, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B.S.; Jegen, R. Motivation crowding theory. J. Econ. Surv. 2001, 15, 589–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, K. The Case for and against Business Assumption of Social Responsibilities. Acad. Manag. J. 1973, 16, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M.C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van de Poel, I.; Fahlquist, J.N. Risk and Responsibility. In Handbook of Risk Theory; Roeser, S., Hillerbrand, R., Sandin, P., Peterson, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 877–907. ISBN 978-94-007-1432-8. [Google Scholar]

- Doorn, N. Responsibility Ascriptions in Technology Development and Engineering: Three Perspectives. Sci. Eng. Ethics 2012, 18, 69–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matten, D.; Crane, A. Corporate Citizenship: Toward An Extended Theoretical Conceptualization. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2005, 30, 166–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnas, J. The Normative Theories of Business Ethics: A Guide for the Perplexed. Bus. Ethics Q. 1998, 8, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P. Evolving Sustainably: A Longitudinal Study of Corporate Sustainable Development. Strateg. Manag. J. 2005, 26, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, R.; Smith, J.; Tashman, P.; Marshall, R.S. Why Do SMEs Go Green? An Analysis of Wine Firms in South Africa. Bus. Soc. 2017, 56, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The process of creative destruction. In Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy; Taylor & Francis e-Library: London, UK, 1943; ISBN 0-203-26611-0. [Google Scholar]

- Von Schomberg, R. A Vision of Responsible Research and Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J.R., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2013; Chapter 3; pp. 51–74. ISBN 978-1-119-96636-4. [Google Scholar]

- Van den Hoven, J. Value Sensitive Design and Responsible Innovation. In Responsible Innovation: Managing the Responsible Emergence of Science and Innovation in Society; Owen, R., Bessant, J.R., Heintz, M., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons Inc.: Chichester, UK, 2013; Chapter 4; pp. 27–50. ISBN 978-1-119-96636-4. [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, R.; Kuhlmann, S.; Randles, S.; Bedsted, B.; Gorgoni, G.; Griessler, E.; Loconto, A.; Mejlgaard, N. (Eds.) Navigating Towards Shared Responsibility in Research and Innovation—Approach, Process and Results of the Res-AGorA Project; Fraunhofer Institute for Systems and Innovation Research ISI: Karlsruhe, Germany, 2016; ISBN 978-3-00-051709-9. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, B.; Obach, M.; Yaghmaei, E.; Ikonen, V.; Chatfield, K.; Brem, A. The Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Maturity Model: Linking Theory and Practice. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubberink, R.; Blok, V.; van Ophem, J.; Omta, O. Lessons for Responsible Innovation in the Business Context: A Systematic Literature Review of Responsible, Social and Sustainable Innovation Practices. Sustainability 2017, 9, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blok, V.; Tempels, T.; Pietersma, E.; Jansen, L. Exploring Ethical Decision Making in Responsible Innovation: The case of innovations for healthy food. In Responsible Innovation 3; Van den Hoven, J., Doorn, N., Swierstra, T., Koops, B.-J., Romijn, H., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, J. Mapping the RRI Landscape: An overview of Organisations, projects, persons, areas and topics. In Responsible Innovation 3: A European Agenda? Asveld, L., Van Dam-Mieras, R., Swierstra, T., Lavrijssen, S., Linse, K., Van den Hoven, J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 21–47. ISBN 978-3-319-64834-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gurzawska, A.; Mäkinen, M.; Brey, P. Implementation of Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) Practices in Industry: Providing the Right Incentives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatridis, K.; Schroeder, D. Responsible Research and Innovation in Industry: The Case for Corporate Responsibility Tools; SpringerBriefs in Research and Innovation Governance; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; ISBN 978-3-319-21692-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pavie, X.; Scholten, V.; Carthy, D. Responsible Innovation: From Concept to Practice; World Scientific: Hackensack, NJ, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-981-4525-07-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pandza, K.; Ellwood, P. Strategic and ethical foundations for responsible innovation. Res. Policy 2013, 42, 1112–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, A.B. Threat Interpretation and Innovation in the Context of Climate Change: An Ethical Perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 143, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, W.S. Social Accountability and Corporate Greenwashing. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 43, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.L. Toward an Integrative Theory of Business and Society: A Research Strategy for Corporate Social Performance. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1999, 24, 506–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Graebner, M.E.; Sonenshein, S. Grand Challenges and Inductive Methods: Rigor without Rigor Mortis. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 1113–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; ISBN 978-0-8039-4653-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, M.G. Fitting Oval Pegs into Round Holes: Tensions in Evaluating and Publishing Qualitative Research in Top-Tier North American Journals. Organ. Res. Methods 2008, 11, 481–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G. From the Editors: For the Lack of a Boilerplate: Tips on Writing up (And Reviewing) Qualitative Research. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 856–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omta, S.W.F.; Folstar, P. Integration of innovation in the corporate strategy of agri-food companies. In Innovation in Agri-Food Systems; Product Quality and Consumer Acceptance; Jongen, W.M.F., Meulenberg, M.T.G., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 221–243. ISBN 90-76998-65-5. [Google Scholar]

- OXFAM International Dutch Beat French and Swiss to Top Oxfam’s New Global Food Table. Available online: https://www.oxfam.org/en/pressroom/pressreleases/2014-01-15/dutch-beat-french-and-swiss-top-oxfams-new-global-food-table (accessed on 23 November 2017).

- Pinckaers, M. The Dutch Food Retail Market; Global Agriculture Information Network; USDA Foreign Agricultural Service: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2016.

- Boer, J.M.A.; Buurma-Rethans, E.J.M.; Hendriksen, M.; Van Kranen, H.J.; Milder, I.E.; Verkaik-Kloosterman, J.; Van Raaij, J. Health Aspects of the Dutch Diet; RIVM National Institute for Health and Environment: Bilthoven, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Roodenburg, A.J.C.; Popkin, B.M.; Seidell, J.C. Development of international criteria for a front of package food labelling system: The International Choices Programme. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011, 65, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-1-60623-977-3. [Google Scholar]

- Blok, V.; Hoffmans, L.; Wubben, E.F.M. Stakeholder engagement for responsible innovation in the private sector: Critical issues and management practices. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2015, 15, 147–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingenbleek, P.T.M.; Meulenberg, M.T.G.; Van Trijp, H.C.M. Buyer social responsibility: A general concept and its implications for marketing management. J. Mark. Manag. 2015, 31, 1428–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, D.; Zollo, M.; Hansen, M.T. Faking It or Muddling Through? Understanding Decoupling in Response to Stakeholder Pressures. Acad. Manag. J. 2012, 55, 1429–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.A.; Montes-Sancho, M.J. An Institutional Perspective on the Diffusion of International Management System Standards: The Case of the Environmental Management Standard ISO 14001. Bus. Ethics Q. 2011, 21, 103–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciliberti, F.; Pontrandolfo, P.; Scozzi, B. Logistics social responsibility: Standard adoption and practices in Italian companies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 113, 88–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reeve, B.; Magnusson, R. Food reformulation and the (neo)-liberal state: New strategies for strengthening voluntary salt reduction programs in the UK and USA. Public Health 2015, 129, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type | Focus of Interest | Motives | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental | Corporation, short-term | Reducing (production) costs | [17,33] |

| Increasing sales through cause-related marketing | [17,41] | ||

| Corporation, long-term | Postponement of legislation | [9,36] | |

| Creating a favorable business environment | [16,40,47] | ||

| Attracting and maintaining employees and investors | [18,39] | ||

| Relational | Direct stakeholders | Fulfilling stakeholder expectations | [33,36] |

| Responding to pressures of voluntary self-regulation | [14,33,35] | ||

| Being recognized for moral leadership | [36] | ||

| Moral | Society | Moral agency—the firm considers itself an intentional agent for the long-term health impact of its products | [50] |

| Causality—the firm considers its innovation activities as part of the cause of the long-term health impact of its products | [9,42,50] | ||

| Knowledge of the consequences—the firm has knowledge about the long-term health impact of its product innovations or makes efforts in collecting that knowledge | [50] | ||

| Transgressing the norm—the firm considers its product innovations and their long-term health impact to be crossing a societal norm | [50] | ||

| Freedom to act—the firm can act upon the long-term health impact of its product innovations without external constraints | [50] |

| Case | Supply Chain Position | Size Category (Revenue in The Netherlands) | Products with Label (Membership) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Case A | Retailer | Large (>3 billion) | 829 (2006–2016) |

| Case B | Retail | Large (>3 billion) | 634 (2006–2016) |

| Case C | Producer (own label) | Large (>150 million) | 332 (2006–2016) |

| Case D | Producer (own label) | Large (>150 million) | 74 (2007–2016) |

| Case E | Producer (own label & co-pack) | Medium (20–150 million) | 42 (2007–2016) |

| Case F | Producer (own label) | Medium (20–150 million) | 5 6(2007–2016) |

| Case G | Producer (own label & co-pack) | Medium (20–150 million) | 17 (2007–2016) |

| Case H | Producer (own label & co-pack) | Small (<20 million) | 100 (2007–2016) |

| Motive | Exemplary Quotes of Instrumental Motives |

|---|---|

| Fulfilling consumer demand | “Satisfied customers and consumers are a prerequisite for the continuity of [firm name] ...” (Case A) |

| “But we also think that our target audience buys it because it is healthy. So, we have to do it anyway, otherwise they don’t buy our products anymore.” (Case H) | |

| Staying competitive | Staying ahead of competition: “There you can differentiate yourself. So we would like to be ahead in everything and nobody can deny that this [sugar-free] movement is there for a few years.” (Case F) |

| Keeping up with the competition: “Like with the NVWA [Dutch food safety authority], they have their monitoring. And, yes, if they publish something, you will of course have a look and say ‘Oh, maybe we are a bit behind on this [sodium]’.” (Case B) | |

| Managing a firm’s reputation and sustaining trust | Proactive reputation management: “It [ed. sugar reduction] is something we really want, what we want to show. We are in touch with the Ministry of Health, for whom we showcase each year: ‘Look, this is what we have again achieved’.” |

| Reactive reputation management: “And if a consumer organization starts pointing like ‘You are bad’, so black-and-white... Yes, we don’t like that. So that’s when sometimes there is an impulse of ‘OK, then maybe we should take on this [product] category’ or ‘how come that our pizzas are that much saltier?’.” (Case B) | |

| Sustaining trust: “A brand is more than a logo or a clever strapline… it’s what people think of when they hear our name. It’s everything the public knows, trusts and loves about us. And for that very reason, brand reputation is hard won, but very easily lost.” (Case D) “[Firm name] values that customers can trust that the products of [firm name] are achieved with respect for people, animals and the environment.” (Case A) |

| Conditions of Responsibility | Exemplary Quotes of Moral Motives |

|---|---|

| Moral agency | “[Firm name] targets with its innovation the achievement of healthy, nourishing, responsible and tasty food...” (Case C) |

| Causality | “Our goals are clear: we want to make sure that the consumer is not misled, that we don’t undermine healthy eating and living habits, that we don’t abuse the trust of children, that we protect children (inside and outside the school environment) and stimulate healthy eating habits.” (Case C) |

| “That [CSR strategy] also includes the reduction of salt and fat: a desire of the whole society with regard to the battle against overweight.” (Case H) | |

| Knowledge of the consequences | “See, we want to make the [product] category healthier, but we have to do that together with our suppliers. And they have a lot of substantive knowledge in-house, so from them [suppliers] you can also learn and eventually together create in a smart way a product category that is tastier and healthier.” (Case A) |

| “But I think you always need external input of people who are really specialized in that discipline. So that is what we do by having such a conversation [with an academic scientist] and we go to a seminar or conference once in a while. That’s how you collect input on these matters”. (Case F) | |

| Transgressing a norm | “For a few years we have had a ready-to-eat meal which stated on the front, ‘This meal contains 150% of your daily salt intake’. That is a great tasting meal and nobody complains. But now you would say ‘That is too much, you shouldn’t want that [in your product portfolio]’. (Case B) |

| Freedom to act | “And fortunately, in our world there is always competition. So if you [the supplier] don’t do it, your neighbor might. See, and then you [as retailer] always look for the best product, for the best price.” (Case B) |

| “And we lose our customers, which is not nice because we want to make money with our products. But you also lose your health gain, if your people [consumers] get back to a product with a higher sugar content.” (Case C) |

| Relational Motive | Underlying Motive | Exemplary Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Fulfilling stakeholder expectations | Instrumental | “So, yes, it [response to negative feedback from a NGO] is more argued from an image point of view: ‘Should I respond immediately?’ [...] If it is big, we will act immediately. [...] (Interviewer: when is it big?) If on the front of the [name Dutch newspaper] it says ‘[Firm name] this and that’, then it is big.’ (Case B) |

| Moral | “At that moment we got a lot of criticism down on our heads. Well, then you just have to take it [...] then you let go of the business model and ask yourself: ‘What do we actually want?’ Then we actually want to make steps towards a healthy breakfast.” (Case A) | |

| Responding to voluntary self-regulation | Instrumental | “As a producer it [the Choices logo] is just a driver to differentiate yourself in the market by really showing that you are innovative [...] Look, behind the scenes, we are always working on this, but it is always nice if you can show it to the consumer.” (Case D) |

| Moral | “Look, if you are talking about innovation, the set of criteria [of the Choices logo] is just really great to have. You can show to the supplier ‘This is what you need to comply with’. And not because [interviewee’s name] or [firm name] really wants it. No, we have agreed to it with each other. There are a lot of people that have contributed to this [set of criteria].” (Case B) | |

| Being recognized for moral leadership | Instrumental | “[About health targets set by the industry] Yes, we are way ahead of target. [...] The nice thing is we see that because we really respond to this healthiness, that we are growing more at the moment than the category [market]. [...] And I think that the fact that we offer healthier products in the market contributes to this [growth] (Case D) |

| Moral | “And we want to stay ahead, that is what we want anyway, so that [the market] you continuously keep an eye on. [...] So I really want that they [competitors] also reduce [sugar], because you want... [...] You don’t reduce sugar to make more money, because then you can better make other choices, right? You want to contribute as a firm to healthier food and that is only possible if the whole market does the same.” (Case C) |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garst, J.; Blok, V.; Jansen, L.; Omta, O.S.W.F. Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122286

Garst J, Blok V, Jansen L, Omta OSWF. Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation. Sustainability. 2017; 9(12):2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122286

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarst, Jilde, Vincent Blok, Léon Jansen, and Onno S. W. F. Omta. 2017. "Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation" Sustainability 9, no. 12: 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122286

APA StyleGarst, J., Blok, V., Jansen, L., & Omta, O. S. W. F. (2017). Responsibility versus Profit: The Motives of Food Firms for Healthy Product Innovation. Sustainability, 9(12), 2286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9122286