Peri-Urban Food Production and Its Relation to Urban Resilience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- What land use changes are occurring on agricultural land in peri-urban areas?

- (2)

- What is the state-of-the-art regarding peri-urban food production?

- (3)

- To what extent is multifunctional peri-urban food production occurring?

- (4)

- What kinds of governance mechanisms are being used to support peri-urban food production as a part of multifunctionality?

- (5)

- How can peri-urban agriculture link urban and rural regions and increase their resilience?

2. Resilience and Food Security in an Urban Context

2.1. Urban Resilience

“Urban resilience refers to the ability of an urban system and all its constituent socio-ecological and socio-technical networks across temporal and spatial scales—to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change, and to quickly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity”.[17]

2.2. Food Security

2.3. Multifunctional Food Production and Resilience

3. Material and Methods

3.1. Study Sites

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis and Presentation of Results

4. Peri-Urban Agricultural Development in Three European Regions

4.1. The Swedish Case—Gothenburg

4.1.1. Development of Agriculture in Hisingen

4.1.2. Strategies for Preserving Peri-Urban Agricultural Land and Aspirations towards Urban Food Policy

4.2. The Danish Case: Farming in Greater Copenhagen

4.2.1. Development of Agriculture in Greater Copenhagen

4.2.2. Farmland Conservation Strategies

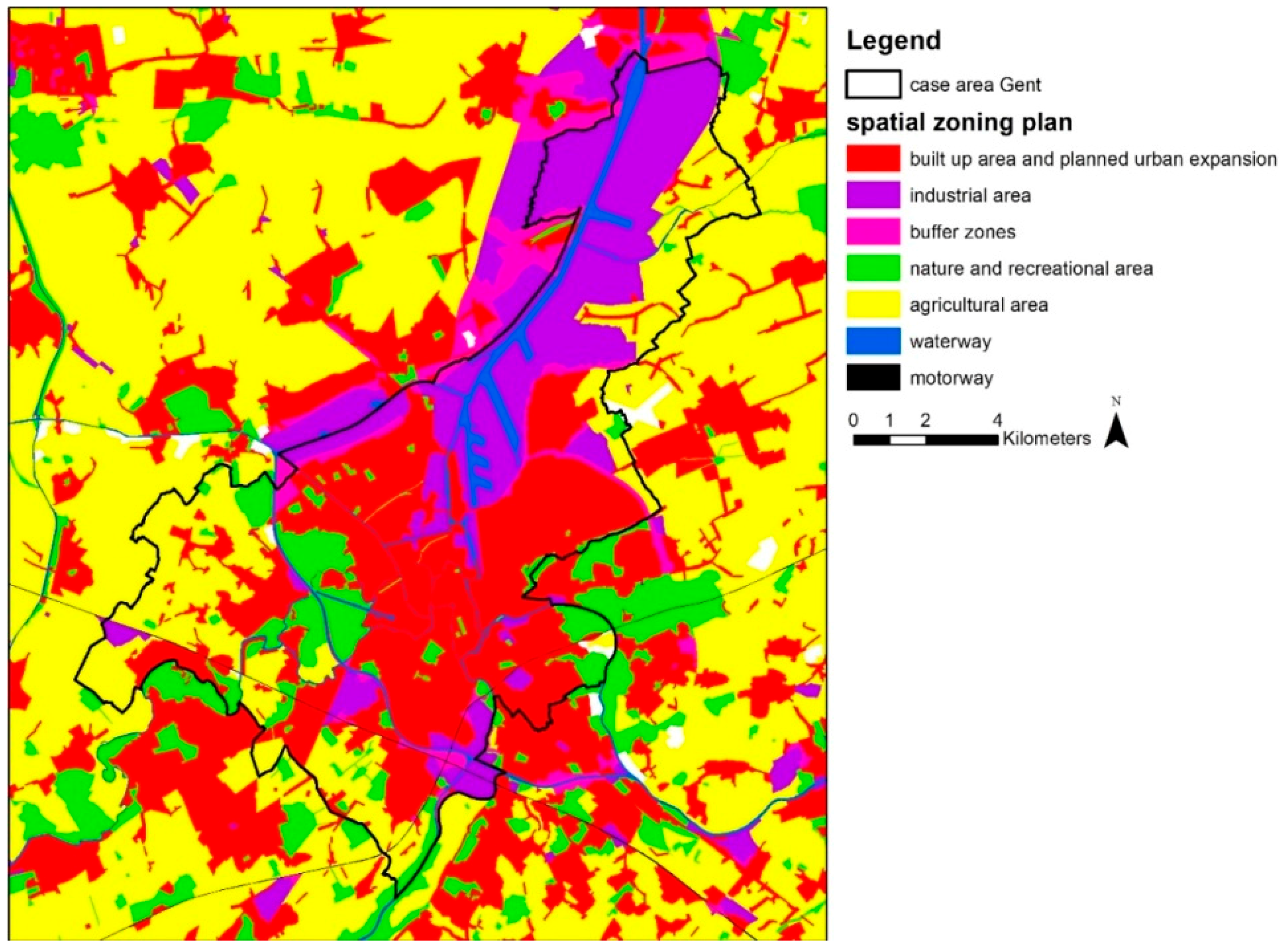

4.3. The Belgian Case—Gent

4.3.1. Development of Agriculture Since 2000

4.3.2. Farmland Preservation Strategy

4.4. Comparative Analysis of the Cases

- First of all, although at different rates, agricultural land decreased in all three cases (Table 2). The first obvious reason is urban expansion including infrastructure. Farmland decreased considerably in all three regions, with a maximum in the Gent region with a decrease of 10% in a timespan of only five years (2005–2010).

- On the remaining agricultural land, there have also been significant changes in agricultural production in all three regions. Generally, there was a decrease in food production and an increase in animal feed production, mainly for horses. In Gothenburg, the case with the strongest horsification trend, horse farms account for 50% of the farmland. In fact, this transformation may be even greater since much of the cereals grown are used for livestock feed. A similar horsification trend is seen in both the Copenhagen and Gent regions, although here exact figures are difficult to obtain, since the horse farms are considered non-agricultural activities and, thus, data are not available from agricultural statistics. The horsification trend can be interpreted as an expression of the strong interest in recreation, which also includes other activities, such as golfing, sports, etc., close to the urban periphery.

- Parallel to the above described horsification trend in all three cases we also see increase in scale. There was a re-structuring of peri-urban farmland with the amalgamation of smaller farm units into fewer larger units producing mainly for an external market. These farms reflect the general development in agriculture in Western Europe during recent decades [37].

- A fourth visible trend among the studied regions is the increase in protected areas and green spaces (Figure 3 and Figure 5, Table 2). In both the Copenhagen and Gothenburg regions, the maintenance of these protected areas requires agricultural activities such as livestock grazing. As such these protected areas directly invite multifunctional agricultural activities. In addition, in the Gent region, nature areas are actively being developed. Thus far, however, they are not dependent on agricultural activities for their maintenance. In all three cases these green areas attract a lot of recreational activities.

5. The Prospects for Peri-Urban Food Production and Urban Resilience

5.1. Governance Mechanisms for the Preservation of Farmland

- The purchase of agricultural land in Hisingen by the Gothenburg municipality in 1967 was accompanied by a double strategy so that farmland for agriculture was given lower rent than the horse farms. At the same time, investments in land and buildings were low, which indirectly favoured the horse farms as they use farmland less intensively, often combined with other economic activities. This can be interpreted as a strategy for maintaining land in a waiting stage prior to conversion to other land uses [40] and/or giving priority to recreation over local food production. Since 2014, there has been a political will in the city to promote local food production on the city’s own agricultural land. This has led to an intensive discussion in Gothenburg about how this can be achieved, renewed interest in agricultural land and a number of collaborative activities, also including the horse farms. There is a direct link to the on-going efforts to formulate a local food strategy for Gothenburg. In spite of the on-going and very promising developments in local food production in Gothenburg, it should be noted that there is an impending threat as a proportion of the agricultural land in Hisingen, the yellow areas in Figure 3, is only reserved for agricultural use until 2020. Thereafter, the fate of this land is unknown and open to different interpretations regarding which land use should be promoted to achieve sustainable development in urban planning.

- In Greater Copenhagen, it is obligatory for all municipalities to plan for and protect agricultural land. However, this planning has not prevented a kind of sub-urbanisation of the peri-urban areas, which implies that a large proportion of the farm properties are inhabited by people with only a minor interest in food production. Although these municipal plans are made and in several of these plans agriculture is highlighted as being important for the municipality, the main motivations are nature conservation, energy production and maintaining an open landscape. This indicates that little attention is given to food production or food security within the existing governance mechanism.

- In the Gent region farmland preservation is organized through spatial planning and the land allocation plan. However, as only 77% of the land allocated for agriculture is affectively in agricultural use the effectiveness of the plan to preserve land for agricultural use may be questioned. The last decade however interest in food production has risen in the Gent region. In recent years the city has taken a lot of policy initiatives in this direction and has established a “food council”, initiated the development of a “local food strategy”. These initiatives might indirectly benefit the farmland preservation policy. However, for this to be effective, there needs to be a real policy integration of spatial and food policy.

5.2. The Current Peri-Urban Food Production for Local Consumption

- First, increased competition for land among farmers, incoming hobby farmers and horse farms has increased land prices (compared to the rural hinterland) and has reduced the land available for full time farmers and thus land used for production. In Gent, farmers indicate that the (low) availability of land is one of the main obstacles to peri-urban food production

- Second, productive peri-urban agricultural land is converted into urban land use (despite farmland preservation policies are in place in all three case areas (Table 2)), nature conservation and recreational areas.

- Third, the growth and centralization of food retailing chains has changed the overall urban food shopping and consumption patterns and has undermined the traditional pattern of food provisioning from peri-urban producers. New consumption patterns linked to direct purchase at the farm gate are evolving in all three case studies but these new trends have (so far) had limited overall effects.

- Fourth, farmers need specific skills and competences to exploit the proximity of the city. Besides agronomic knowledge, they also need good marketing and management skills to set up a business models that fully exploits the vicinity of the city. Contradictions in legislation are complicating the development of such multifunctional farming activities (see [24]).

- Fifth, a lack of institutional infrastructure to link peri-urban food production more directly with local consumption is without doubt also playing a role. Although food policies are present within all three urban regions studied no specific initiatives to promote local production and to bring peri-urban farmers in closer contact with nearby urban consumers have been found. On the contrary, increased restrictions imposed on farmers in relation to food safety and CAP payments have supported centralized networks.

5.3. Peri-Urban Multifunctionality and Food Production

5.4. What Is Needed to Support Peri-Urban Food Production in Terms of Governance?

5.5. How Can Peri-Urban Agriculture Link Urban and Rural Regions and Increase Their Resilience?

6. Conclusions

- Secure incentives/regulations for access to farmland for food production at a reasonable level of land rent decoupled from the huge peri-urban land prices.

- Facilitate the establishment of local markets for locally produced food.

- Encourage and promote the production of Food Charters that link consumers, authorities, entrepreneurs and producers in urban–rural regions.

- Facilitate the creation of networks of farmers and other rural entrepreneurs who have an interest in food production and establish new partnerships around multifunctional agriculture and local food production.

- The linking and integration of spatial planning and urban–rural development agencies.

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations. World Urbanisation Prospects. The 2014 Revision; Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: http://www.esa.un.org (accessed on 23 September 2016).

- Malano, H.; Maheshwari, B.; Singh, V.P.; Purohit, R.; Amerasinghe, P. Challenges and opportunities for peri-urban futures. In The Security of Water, Food, Energy and Liveability of Cities; Maheshwari, B., Purohit, R., Malano, H., Singh, V.P., Amerasinghe, P., Eds.; Water Science and Technology Library; Springer Science & Business Media: Dortrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 71, pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- Loibl, W.; Piorr, A.; Revetz, J. Concepts and methods. In Peri-Urbanisation in Europe: Towards a European Policy to Sustain Urban-Rural Futures; Piorr, A., Ravetz, J., Tosics, I., Eds.; University of Copenhagen, Academic Books Life Sciences: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2011; pp. 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, K. Nourishing the city: The rise of the urban food question in the Global North. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1379–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMichael, P. Food system sustainability: Questions of environmental governance in the new world (dis)order. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2011, 21, 804–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galt, R.E. Placing food systems in first world political ecology: A review and research agenda. Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 637–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, J.R.; Dyball, R.; Dumaresq, D.; Deutsch, L.; Matsuda, H. Feeding capitals: Urban food security and self-provisioning in Canberra, Copenhagen and Tokyo. Glob. Food Secur. 2014, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordell, D.; White, S. Tracking phosphorus security. Indicators of phosphorus vulnerability in the global food system. Food Secur. 2015, 7, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L.A., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Steffen, W.; Persson, Å.; Deutsch, L.; Zalasiewicz, J.; Williams, M.; Richardson, K.; Crumley, C.; Crutzen, P.; Folke, C.; Gordon, L.; et al. The Anthropocene: From global change to planetary stewardship. Ambio 2011, 40, 739–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, B. What kind of thing is Resilience? Politics 2015, 35, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C. Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallopin, G.C. Linkages between vulnerability, resilience, and adaptive capacity. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2006, 16, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M. Resilience: A conceptual lens or rural studies? Geogr. Compass 2013, 7, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, B.; Holling, C.S.; Carpenter, S.R.; Kinzig, A. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social-ecological systems. Ecol. Soc. 2004, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; de Los Rios, I.; Knickel, K.; Koopmans, M.; Lamine, C.; Olsson, G.A.; de Roest, K.; Rogge, E.; Sumane, S.; Tisenkops, T. Analytical Framework for RETHINK Project; RURAGRI, ERA-NET, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitzinger, S.P.; Svedin, U.; Crumbley, C.L.; Steffen, W.; Abdullah, S.A.; Alfsen, C.; Broadgate, W.; Biermann, F.; Bondre, N.R.; Dearing, J.A.; et al. Planetary stewardship in an urbanising world: Beyond city limits. Ambio 2012, 41, 787–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Sasu-Boakye, Y.; Cederberg, C.; Wirsenius, S. Localising livestock protein feed production and the impact on land use and greenhouse gas emissions. Animal 2014, 8, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirwan, J.; Maye, D. Food security framings within the UK and the integration of local food systems. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 29, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opitz, I.; Berges, R.; Piorr, A.; Krikser, T. Contributing to food security in urban areas: Differences between urban agriculture and peri-urban agriculture in the Global North. Agric. Hum. Values 2016, 33, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I. Multifunctional peri-urban agriculture—A review of societal demands and the provision of goods and services by farming. Land Use Policy 2011, 28, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogge, E.; Kerselaers, E.; Prové, C. Envisioning Opportunities for Agriculture in Peri-Urban Areas. In Metropolitan Ruralities (Research in Rural Sociology and Development); Andersson, K., Sjöblom, S., Granberg, L., Ehrström, P., Marsden, T., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2016; Volume 23, pp. 161–189. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.A. From ‘weak’ to ‘strong’ multifunctionality: Conceptulizing farm-level multifunctional transitional pathways. J. Rural Stud. 2008, 24, 367–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, C.; von Haaren, C.; Albert, C. Optimizing environmental measures for landscape multifunctionality: Effectiveness, efficiency and recommendations for agri-environmental programs. J. Environ. Manag. 2015, 151, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappell, M.J.; La Valle, L.A. Food security and biodiversity: Can we have both? Agric. Hum. Values 2011, 28, 3–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björklund, J.; Araya, H.; Edwards, S.; Goncalves, A.; Höök, K.; Lundberg, J.; Medina, C. Ecosystem-Based Agriculture Combining Production and Conservation—A Viable Way to Feed the World in the Long Term? J. Sustain. Agric. 2012, 36, 824–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization. Agroforestry Definition. Available online: http://www.fao.org/forestry/agroforestry/80338/en/ (accessed on 20 February 2016).

- Rundlof, M.; Nilsson, H.; Smith, H.G. Interacting effects of farming practice and landscape context on bumble bees. Biol. Conserv. 2008, 141, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colasanti, K.J.A.; Hamm, M.W. Assessing the local food supply capacity of Detroit, Michigan. J. Agric. Food Syst. Community Dev. 2010, 1, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, N.; Cooper, J.; Khandeshi, S. Assessing the potential contribution of vacant land to urban vegetable production and consumption in Oakland, California. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 111, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques-Perez, I.; Segura, B.; Maroto, C. Evaluating the functionality of agricultural systems: Social preferences for multifunctional peri-urban agriculture. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2014, 12, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, N.E.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W.; Higgins, S.L.; Depledge, M.H.; Norris, K. Biodiversity, cultural pathways, and human health: A framework. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2014, 29, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrus, G.; Scopelliti, M.; Laforezza, R.; Colangelo, G.; Ferrini, F.; Salbitano, F.; Agrimini, M.; Portoghesi, L.; Semenzato, P.; Sanesi, G. Go greener, feel better? The positive effects of biodiversity on the well-being of individuals visiting urban and peri-urban green areas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 134, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Fertner, C.; Piorr, A.; Sick Nielsen, T. Peri-urbanisation and multifunctional adaption of agriculture around Copenhagen. Geogr. Tidskr. 2011, 111, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, E.G.A.; Bruckmeier, K.; Wästfelt, A. RETHINK Case Study: Peri-Urban Agricultural Transformations in Gothenburg, Sweden; RURAGRI, ERA-NET, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Koopmans, M.; Rogge, E.; Mettepenningen, E.; Kerselaers, E.; van Huylenbroeck, G.; de Krom, M. RETHINK Case Study: “New Form of Governance in Landscape Development”, Belgium; RURAGRI, ERA-NET, European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Grandgirard, D.; Zielinski, R. Land Parcel Identification System (LPIS) Anomalies’ Sampling and Spatial Pattern; JRC Scientific and Technical Reports; European Communities: Luxembourg, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wästfelt, A.; Zhang, Q. Reclaiming localisation for revitalising agriculture: A case study of peri-urban agricultural change in Gothenburg, Sweden. J. Rural Stud. 2016, 47, 172–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogstrup, S.; Primdahl, J. Urban Agricultural Areas in the Metropolitan Region 1994; Forskningsserien Forskningscentret for Skov and Landskab 14; Forest & Landscape: Hørsholm, Denmark, 1996; p. 127. [Google Scholar]

- Busck, A.G.; Kristensen, S.P.; Præstholm, S.; Reenberg, A.; Primdahl, J. Land system change in the context of urbanisation: Examples from the peri-urban area of greater Copenhagen. Geogr. Tidsskr. 2006, 106, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primdahl, J.; Busck, A.G.; Lindemann, C. Bynære Landbrugsområder I Hovedstadsregionen 2004. Udvikling I Landbrug, Landskab og Bebyggelse 1984–2004; Forest & Landscape: Hørsholm, Denmark, 2006; p. 93. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Board of Statistics. Statistics Sweden—Population Development. Statistiska Centralbyrån, Stockholm. Available online: www.scb.se (accessed on 7 July 2016).

- Kroon, A. Närodlad Mat Till Staden—En Framtidspotential? Bachelor’s Thesis, Human Ecology at School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, E.G.A.; Olsson, M. Matproduktion och Urban Hållbarhet—Fallstudie Från Hisingen och Göteborgs Framtida Möjligheter; Report 2016, 3; Mistra Urban Futures: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Swedish Board of Agriculture. Åkermarkens Användning efter Län/Riket och Gröda 1981–2015. Available online: www.jordbruksverket.se (accessed on 19 August 2016).

- Ahlm, E. Natura 2000 Areas as Sustainability Resources. (Natura 2000-Områden Som Hållbarhetsresurser). Master’s Thesis, Human Ecology at School of Global Studies, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Berg, M.; Andersson, J. Peri-Urban Food Production. How to Shape Preconditions for Local Food Production? Report 2015, 4; Mistra Urban Futures: Gothenburg, Sweden, 2015. (In Swedish) [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, K.A. Stadsodling Eller 3D-Skrivare? 2015. Available online: https://odlastadenbloggen.org/tag/karin-svensson/ (accessed on 15 April 2016).

- Den Store Danske (Gyldendal). Hovedstadsområdet. Available online: http://denstoredanske.dk/Danmarks_geografi_og_historie/Danmarks_geografi/K%C3%B8benhavn/Hovedstadsomr%C3%A5det (accessed on 16 April 2016).

- Danmarks Statistik. Statistikbank. Available online: http://www.statistikbanken.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1680 (accessed on 16 April 2016).

- Kyndesen, M.; Vesterager, J.P.; Busck, A.G.; Primdahl, J.; Vejre, H.; Kristensen, L.; Kristensen, S.B.P.; Richardt, A.-S.; Præstholm, S.; Fertner, C.; et al. Bynære Landbrugsområder I Hovedstadsregionen 2014—Udvikling I Landbrug, Landskab og Bebyggelse 1984–2014; IGN Rapport; Institut for Geovidenskab og Naturforvaltning: Frederiksberg, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Primdahl, J.; Kristensen, L. Danske erfaringer med det åbne landsplanlægning. Kungl. Skogs-Och Lantbruksakademiens Tidskr. 2003, 142, 11–24. [Google Scholar]

- European Environment Agency. Urban Sprawl in Europe. The Ignored Challenge; Report 2006, 10; EEA: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Algemene Directie Statistiek. Census data of the National institute for statistics (Algemene Directie Statistiek), 2012; National Institute for Statistics: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Agentschap Geografische Informatie Vlaanderen. Digital Layer of Municipal Borders Flanders 2014 (Agentschap Geografische Informatie Vlaanderen); Flemish Institute for Geographical Information: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Eenmalige Perceelsregistratie. Flemish Land Parcel Identification System (Eenmalige Perceelsregistratie), 2013; Department of Agriculture and Fisheries: Ostende, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vuylsteke, A.; Bergen, D.; Demuynck, E. Schaalgrootte en Schaalvergroting in de Vlaamse Land-en Tuinbouw (Scale and Scale Enlargement in the Flemish Agriculture and Horticulture); Departement Landbouw en Visserij, afdeling Monitoring en Studie: Brussel, Belgium, 2014. (In Dutch) [Google Scholar]

- Kerselaers, E. Participatory Development of a Land Value Assessment Tool for Agriculture to Support Rural Planning in Flanders. Ph.D. Thesis, Gent University, Gent, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoeve, A.; Dewaelheyns, V.; Kerselaers, E.; Rogge, E.; Gulinck, H. Virtual farmland: Grasping the occupation of agricultural land by non-agricultural land uses. Land Use Policy 2015, 42, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bomans, K. Revisiting Dynamics and Values of Open Space. The Case of Flanders. Ph.D. Thesis, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Leuven, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kerselaers, E.; van den Haute, F.; Verhoeve, A.; Rogge, E. Analysis of spatial patterns and driving factors of farmland loss. In Presented at the Second International Conference on Agriculture in an Urbanising Society: Reconnecting Agriculture and Food Chains to Societal Needs, Rome, Italy, 14–17 September 2015.

- Agentschap Geografische Informatie Vlaanderen. Digital Layer of Land Allocation Plan 2013 (Agentschap Geografische Informatie Vlaanderen); Flemish Institute for Geographical Information: Brussels, Belgium, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, J.; de Groot, H.L.F.; Verburg, P.H. Manifestations and underlying drivers of agricultural land use change in Europe. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2015, 133, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasada, I.; Berges, R.; Hilgendorf, J.; Piorr, A. Horsekeeping and the peri-urban development in the Berlin Metropolitan Region. J. Land Use Sci. 2013, 8, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primdahl, J.; Vejre, H.; Busck, A.; Kristensen, L. Planning and development of the fringe landscapes: On the outer side of the Copenhagen ‘fingers’. In Regional Planning for Open Space; van der Valk, A., van Dijk, T., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2009; pp. 21–60. [Google Scholar]

- Plieninger, T.; Bieling, C. (Eds.) Resilience and the Cultural Landscape. Understanding and Managing Change in Human-Shaped Environments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012.

- Pinto-Correia, T.; Kristensen, L. Linking research to practice: The landscape as the basis for integrating social and ecological perspectives of the rural. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2013, 120, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selman, P. Planning for landscape multifunctionality. Sustain. Sci. Pract. Policy 2009, 5, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Paül, V.; McKenzie, F. Peri-urban farmland conservation and development of alternative food networks: Insights from a case-study area in metropolitan Barcelona (Catalonia, Spain). Land Use Policy 2013, 30, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, C. Regulation of Farmland Conversion on the Urban Fringe: From Land-Use Planning to Food Strategies. Insight into Two Case Studies in Provence and Tuscany. Int. Plan. Stud. 2013, 18, 21–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardman, M.; Larkham, P.J. The rise of a ‘food charter’: A mechanism to increase urban agriculture. Land Use Policy 2014, 39, 400–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of Small Farms and Innovative Food Supply Chains: The Role of Food Hubs in Creating Sustainable Regional and Local Food Systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, H.; Habersetzer, A.; Meili, R. Rural–Urban Linkages and Sustainable Regional Development: The Role of Entrepreneurs in Linking Peripheries and Centers. Sustainability 2016, 8, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-SDG 2015. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals for 2030. Available online: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 1 August 2016).

- Beauchesne, A.; Bryant, C. Agriculture and innovation in the urban fringe: The case of organic farming in Quebec, Canada. Tijdschr. Econ. Soc. Geogr. 1999, 90, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsden, T. Sustainable place-making for sustainability science: The contested case of agri-food and urban-rural relations. Sustain. Sci. 2013, 8, 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Land Use | 1984 | 1994 | 2004 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arable land (short term rotation) | 84% | 78% | 74% | 67% |

| Permanent grassland | 6% | 9% | 12% | 13% |

| Horticulture | 3% | 2% | 0% | 0% |

| Christmas trees/greenery | 0% | 1% | 2% | 2% |

| Forest | 2% | 1% | 3% | 4% |

| Other areas incl. buildings, roads, nature etc. | 6% | 8% | 8% | 14% |

| Gothenburg, S | Gent, Be | Copenhagen, Dk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of Agricultural land (% change 2000–2014, Trends) | Loss of agricultural land: −5% (G-g: On total cultivated area irrespective of crop. Contains permanent leys for horse feed, etc. Calculated on the basis of land parcel data 2001–2013); Decline in arable land; increase in feed production for animals (permanent grasslands); 50% of agricultural land used for recreation, horse riding | Loss of agricultural land: −10%; Decline in arable land; 24% of agricultural land used for recreation, nature protection, etc. | Loss of agricultural land 1982–2014: decrease 6.5% (Copenhagen—see Table 1); Decline in arable land; increase in feed production for animals (permanent grasslands); increase in green spaces for recreation and nature and wood lots |

| Land use changes on remaining agricultural land | (G-g: calculated on land parcel data 2001–2013.) Cereals: −18% Permanent pasture: +14% | No data | Arable: −20% Permanent pastures: +117% Uncultivated land: +133% |

| Peri-urban horse farms (Horse farm: horse activities are the main activities; fodder production for the horses is sometimes included. Horse farms use arable land for feed production and horse grazing.) | Hisingen: 45 of total 62 farms are horse farms using approximately 50% of agricultural land Ley/Sown pasture (mainly for horses) increased 14% in 2001–2013 | Flanders: An average of 7% of the agricultural land | In the GC case areas, 35 of total 157 farms have horses on the farm (22%) Permanent pasture has increased 8% in 2004–2014 |

| Protected areas (PA) and other green spaces; Trend | 5 protected areas (All protected areas in G-g belong to agricultural landscape and include semi-natural grasslands and arable fields), approximately 15% of the Hisingen area; Trend: PAs increasing since 2000 | Trend: 4 large protected areas since 2000 for nature conservation and for recreation | Trend GC case study 1984–2014: more land for recreation |

| Farm land preservation strategy | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gothenburg, S | Gent, Be | Copenhagen, Dk | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-urban food production for local sale today | Vegetables, 1 farm, 1% of arable Meat production, 2 farms, 14% of arable | Local sale of potatoes, vegetables, fruit, milk, ice cream, cheese, meat (on farm, farmers’ markets, vegetable box schemes), 2 CSA farms | No official data on this issue although increasing interest from urban citizens. The current local sale is estimated to a very small part of the total food production in the PU region |

| Multifunctional food production for local consumption today | Livestock grazing in protected areas: Meat; Landscape values; Biodiversity; Cultural heritage; Recreation | Sheep grazing on banks of watercourses in the city: Meat; Landscape values; Biodiversity; Cultural heritage Parks with fruit trees and vegetable production: Fruit; Vegetables; Recreation; Social cohesion of neighbourhoods | Some farmers combine food production with other land use activities: e.g., social farming, farm tourism |

| Governance supporting multifunctional and local food production | No specific governance instrument | Local food strategy and food council initiated by local stakeholders and the city; several bottom-up initiatives such as citizens’ groups who start/support local food production initiatives | No specific governance mechanism that supports multifunctional food production—on the farm However, land use planning legislation allows multi-functionality at the farm level |

| Local food strategy | Yes—in progress to be issued 2017 | Yes | No |

| Peri-Urban Agriculture linking urban—rural regions | CSA enterprises supported by GR-region and G-g municipality | CSA farms | No |

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Olsson, E.G.A.; Kerselaers, E.; Søderkvist Kristensen, L.; Primdahl, J.; Rogge, E.; Wästfelt, A. Peri-Urban Food Production and Its Relation to Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121340

Olsson EGA, Kerselaers E, Søderkvist Kristensen L, Primdahl J, Rogge E, Wästfelt A. Peri-Urban Food Production and Its Relation to Urban Resilience. Sustainability. 2016; 8(12):1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121340

Chicago/Turabian StyleOlsson, E. Gunilla A., Eva Kerselaers, Lone Søderkvist Kristensen, Jørgen Primdahl, Elke Rogge, and Anders Wästfelt. 2016. "Peri-Urban Food Production and Its Relation to Urban Resilience" Sustainability 8, no. 12: 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121340

APA StyleOlsson, E. G. A., Kerselaers, E., Søderkvist Kristensen, L., Primdahl, J., Rogge, E., & Wästfelt, A. (2016). Peri-Urban Food Production and Its Relation to Urban Resilience. Sustainability, 8(12), 1340. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8121340