Enhanced Sustainability of Projects Based on Dynamic Time Management Using Petri Nets

Abstract

1. Introduction

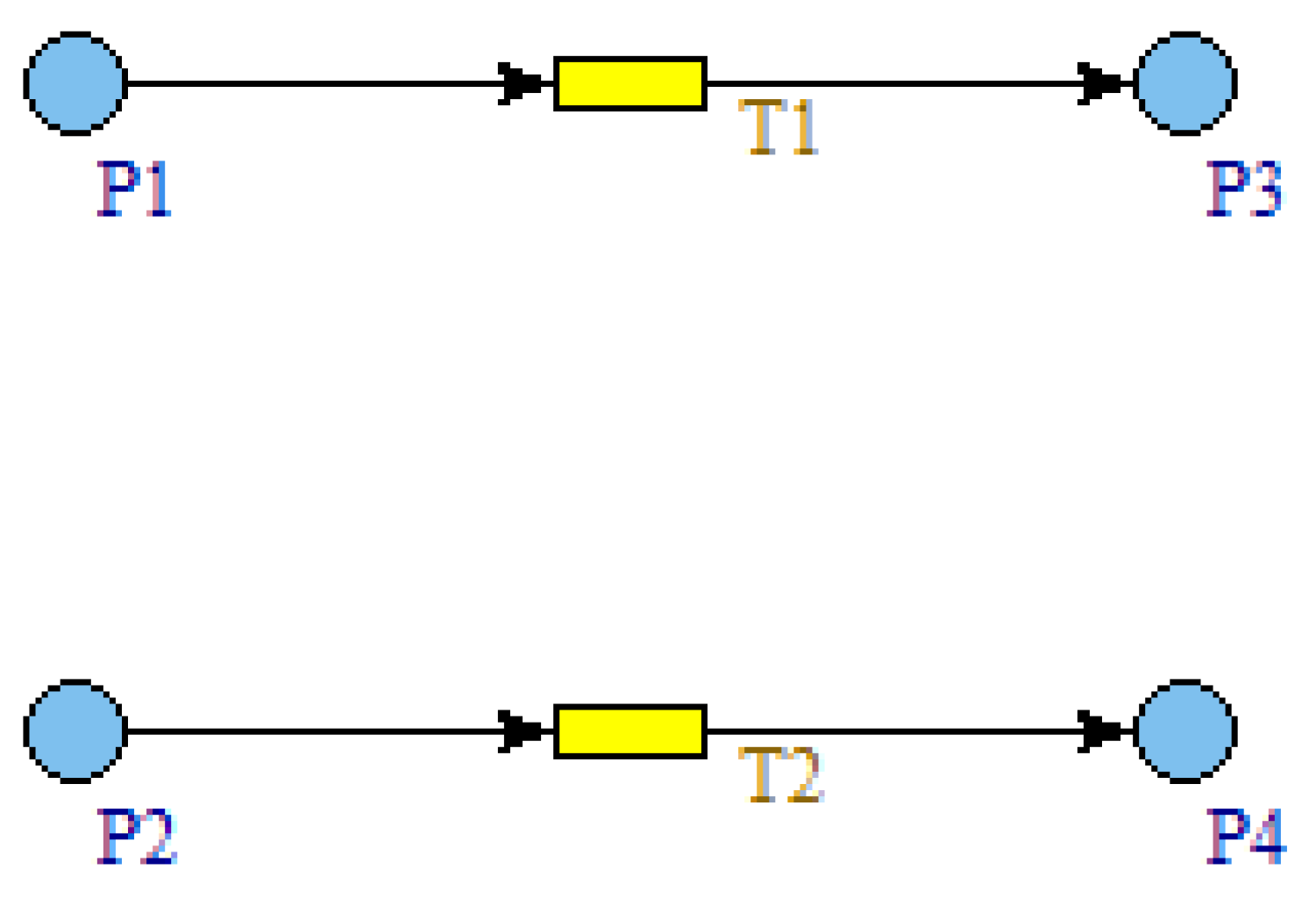

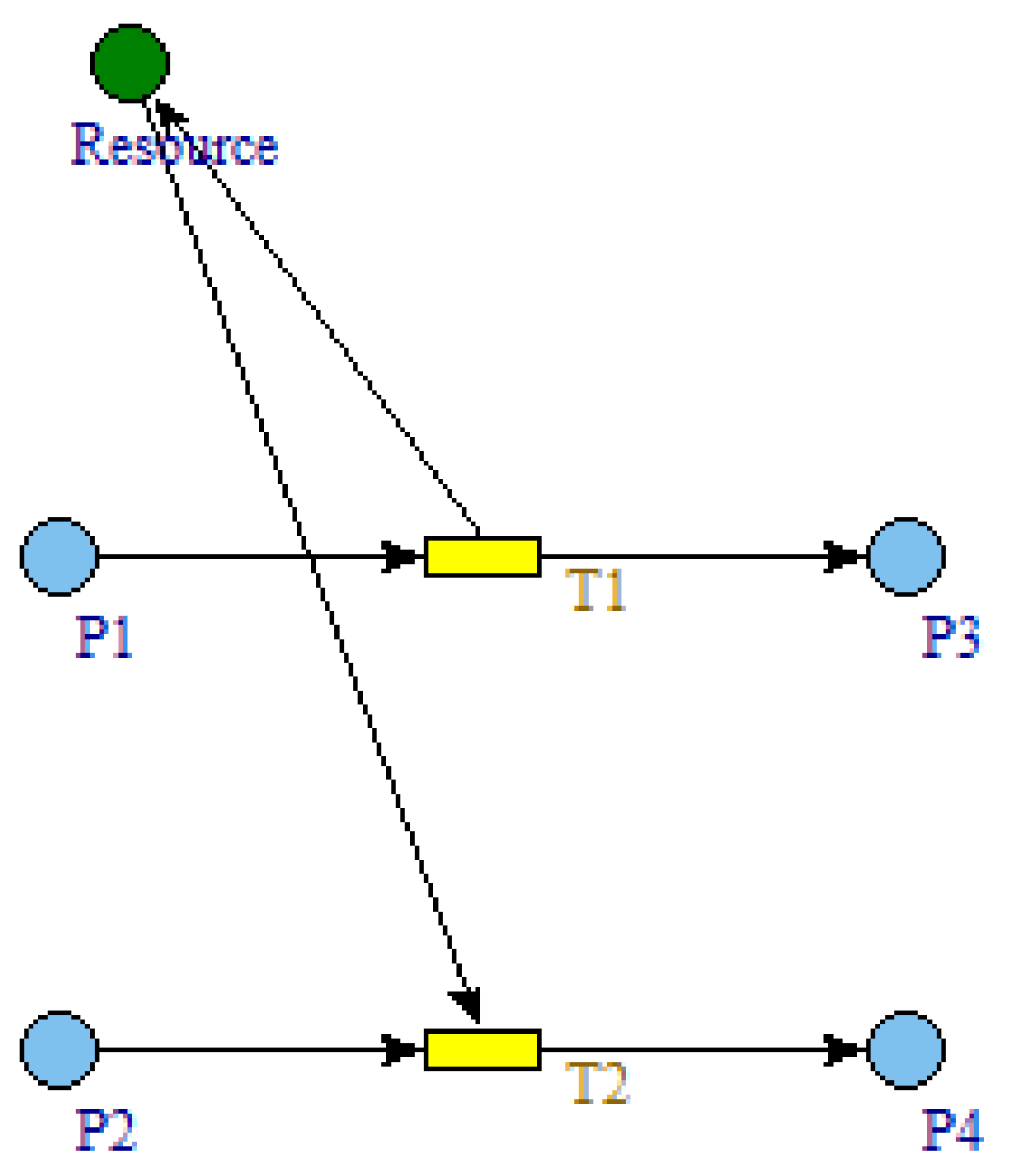

2. Petri Nets

2.1. Definition of Petri Nets

2.2. Firing Rule

2.3. Timed Petri Nets

3. Literature Review on Petri Net-Based Project Management

| Authors (Year) | Title | Research Focus and Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Kumar & Kumar (2024) [25] | A hybrid soft computing technique by using fuzzy Petri nets to optimize the critical path in management problem | Proposes a hybrid fuzzy Petri net approach to optimize the critical path under uncertainty, improving decision support in project management. |

| Huang et al. (2023) [26] | Scheduling of resource allocation systems with timed Petri nets: A survey | Provides a comprehensive survey of timed Petri net approaches for scheduling and resource allocation, highlighting trends and limitations. |

| Azarnova et al. (2021) [27] | Application of Bayesian networks and Petri nets apparatus for the study of projects implementation calendar plans | Combines Bayesian networks and Petri nets to assess schedule risks and temporal uncertainty in project implementation plans. |

| Salimifard et al. (2019) [22] | Managing time and resources of construction projects using colored Petri nets and a genetic algorithm | Combines colored Petri nets with a genetic algorithm to optimize time and resource allocation in construction projects, demonstrating improved scheduling performance under complex constraints. |

| Mazzuto & Bevilacqua (2018) [28] | A decision-making application for project management through timed coloured Petri nets | Develops a decision-support application using timed colored Petri nets to evaluate alternative project execution scenarios. |

| Bevilacqua et al. (2018) [24] | Timed coloured Petri nets and project management applications | Demonstrates applications of timed colored Petri nets for modeling temporal constraints in complex project environments. |

| Liu et al. (2016) [29] | Time performance optimization and resource conflicts resolution for multiple project management | Addresses time optimization and resource conflict resolution in multi-project environments using Petri-net-based models. |

| Boushaala (2014) [4] | An approach for project scheduling using PERT/CPM and Petri nets (PNs) tools | Proposes an integrated PERT/CPM and Petri-net-based approach for project scheduling, using Petri net theory to verify project feasibility, identify the critical path, estimate total project duration, and ensure deadlock-free execution through algebraic analysis. |

| Li & Liu (2014) [30] | Resource management modelling and simulating of a construction project based on Petri net | Presents a Petri-net-based model for simulating and analyzing construction resource allocation strategies. |

| Lin & Dai (2014) [5] | Applying Petri nets on project management | Presents a Petri-net-based modeling approach for project management in which CPM diagrams are transformed into Petri nets with timed transitions and resource places to analyze project duration and resource constraints. |

| Chen & Shan (2012) [31] | The application of Petri nets to construction project management | Shows that Petri nets effectively capture workflow logic and improve visualization and coordination in construction projects. |

| Zhang et al. (2012) [32] | Risk management for construction projects with colored Petri nets | Introduces an agent-based risk management framework using colored Petri nets for construction projects. |

| Samkari et al. (2012) [33] | Colored Petri-net and multi-agents: A combination for a time-efficient evaluation of a simulation study in construction management | Combines colored Petri nets and multi-agent systems to enhance computational efficiency in construction simulation studies. |

| Chung (2011) [34] | Modeling of construction scheduling with coloured Petri nets | Develops a colored Petri net model integrating sequencing and resource attributes for construction scheduling analysis. |

| Cheng et al. (2011) [35] | A Petri net simulation model for virtual construction of earthmoving operations | Proposes a Petri-net-based simulation model to analyze productivity and process interactions in earthmoving operations. |

| Subulan et al. (2011) [36] | Modeling and analyzing of a construction project considering resource allocation through a hybrid methodology | Applies a hybrid Petri net and fuzzy rule-based approach to improve modeling of resource allocation decisions. |

| Wu et al. (2009) [37] | Solving resource-constrained multiple project scheduling problem using timed colored Petri nets | Uses timed colored Petri nets to explicitly model time and resource conflicts in multi-project scheduling. |

| Adida & Joshi (2009) [38] | A robust optimisation approach to project scheduling and resource allocation | Presents a robust optimization framework supported by formal modeling techniques for project scheduling under uncertainty. |

| Biruk & Jaśkowski (2008) [39] | Simulation modelling construction project with repetitive tasks using Petri nets theory | Demonstrates the effectiveness of Petri nets in modeling repetitive construction tasks and evaluating time performance. |

| Chen et al. (2008) [3] | A Petri net approach to support resource assignment in project management | Introduces a Petri-net-based framework for resource assignment in project management, modeling resource availability and allocation through dedicated places and transitions to support conflict resolution and improved coordination. |

| Cohen & Zwikael (2008) [21] | Modelling and scheduling projects using Petri nets | Shows that Petri nets support representation of parallelism and dependencies beyond traditional CPM techniques. |

| Kumanan & Raja (2008) [2] | Modeling and simulation of projects with Petri nets | Proposes a Petri-net-based framework for modeling and simulating project schedules, transforming activity-on-arrow networks into Petri nets and demonstrating how precedence relations and execution logic can be analyzed through simulation and Petri net properties. |

| Nassar & Casavant (2008) [40] | Analysis of timed Petri nets for reachability in construction applications | Applies reachability analysis to verify feasible execution sequences in construction project models. |

| Salum (2008) [41] | Petri nets and time modelling | Discusses time modeling concepts in Petri nets and their relevance for dynamic project systems. |

| Haji & Darabi (2007) [42] | Petri net based supervisory control reconfiguration of project management systems | Introduces a Petri-net-based supervisory control framework enabling dynamic reconfiguration of project execution. |

| Kao et al. (2006) [43] | A Petri-net based approach for scheduling and rescheduling resource-constrained multiple projects | Addresses dynamic scheduling and rescheduling of resource-constrained multiple projects using Petri nets. |

| Chahrour & Franz (2006) [44] | Seamless data model for a CAD-based simulation system | Presents a Petri-net-compatible data model enabling integration of CAD data with construction simulation systems. |

| Sawhney & Mund (2003) [45] | Petri net-based scheduling of construction projects | Introduces a Petri-net-based scheduling framework that explicitly models concurrency, sequencing, and resource interactions. |

| Reddy & Kumanan (2001) [46] | Application of Petri nets and a genetic algorithm to multi-mode multi-resource constrained project scheduling | Integrates Petri nets with genetic algorithms to improve search for near-optimal schedules under complex constraints. |

| Sawhney & Vamadevan (2000) [47] | Petri Net-Based Scheduling of a Bridge Project | Applies Petri-net-based scheduling to a real bridge construction project, demonstrating improved modeling of activity interactions. |

| Jaworski & Biruk (2000) [48] | A model of construction project based on Petri nets theory | Proposes a conceptual Petri-net-based model providing a formal foundation for construction project representation. |

| Sawhney & Mund (1999) [20] | Hierarchical and modular modeling of structural steel erection process using Petri nets | Develops a hierarchical and modular Petri net framework improving scalability for modeling steel erection processes. |

| Sawhney et al. (1999) [20] | Simulation of the structural steel erection process | Uses Petri-net-based simulation to analyze sequencing, resource interactions, and productivity in steel erection. |

| Sawhney (1997) [19] | Petri Net based simulation of construction schedules | Demonstrates that Petri-net-based simulation supports more realistic evaluation of construction schedules than deterministic methods. |

| Wakefield & Sears (1997) [18] | Petri nets for simulation and modeling of construction systems | Shows that Petri nets effectively capture system dynamics and interactions in construction process modeling. |

| Kim & Desrochers (1995) [17] | Task planning and project management using Petri nets | Investigates early applications of Petri nets for representing task dependencies, concurrency, and control logic. |

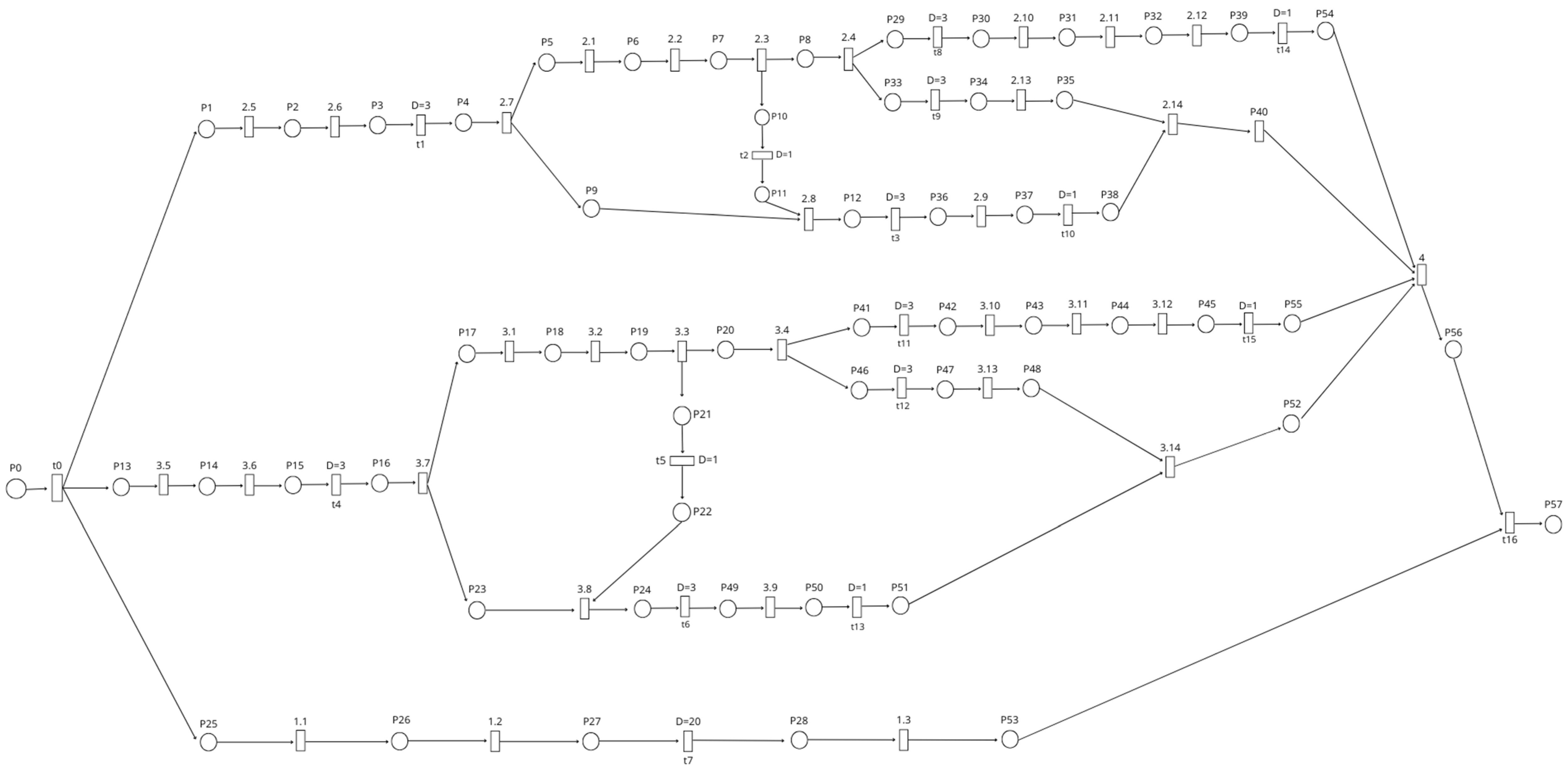

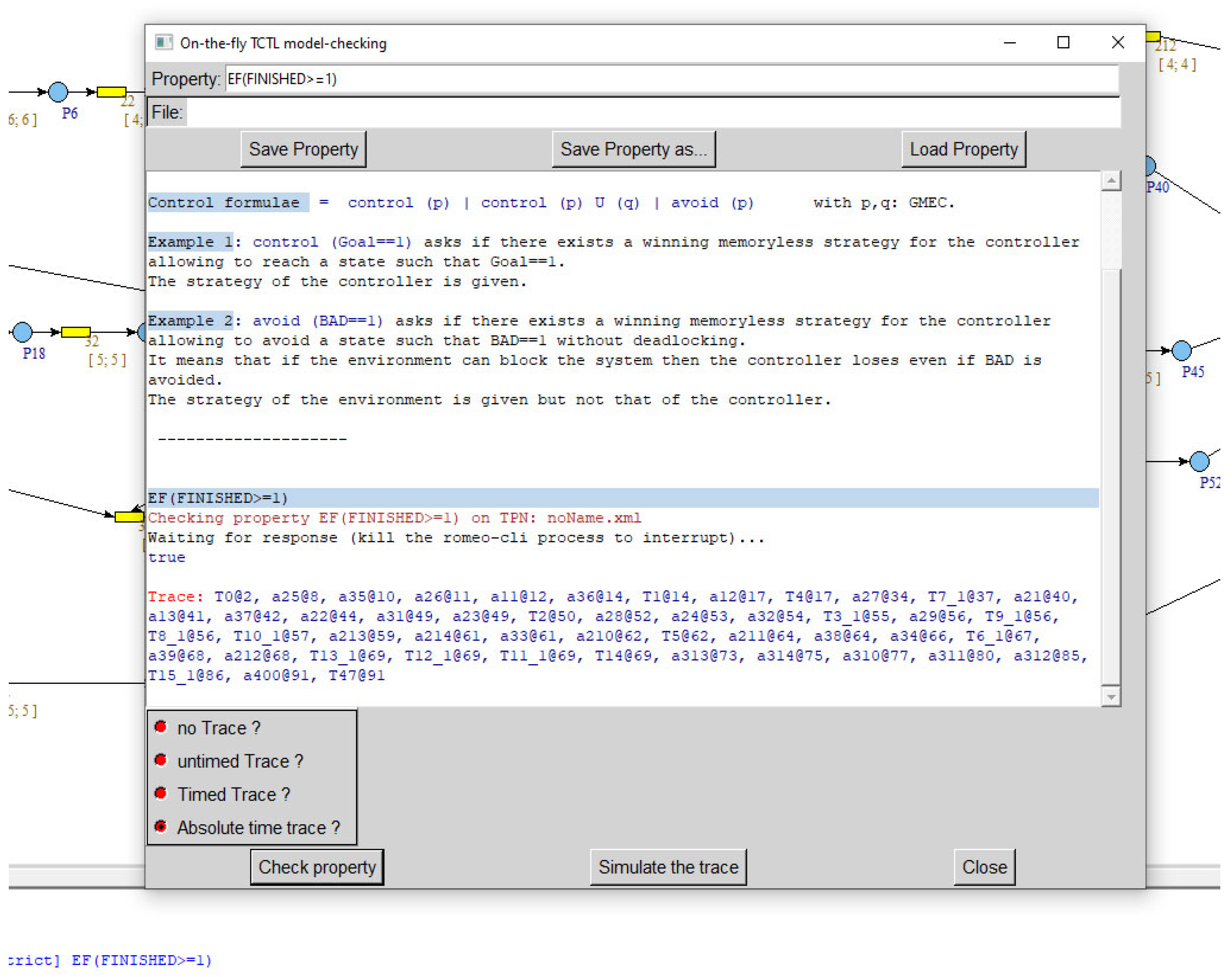

4. Case Study

4.1. Project

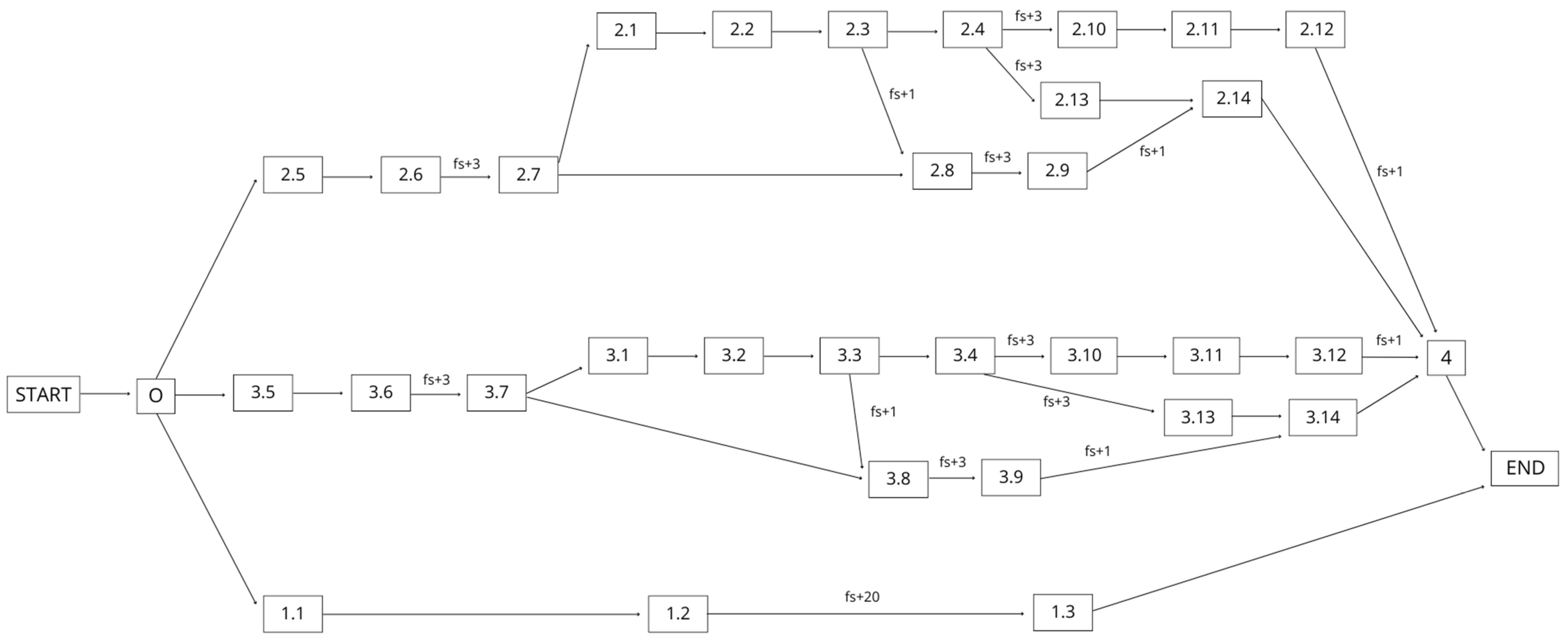

4.2. CPM

- Earliest Start (ES);

- Latest Start (LS);

- Earliest Finish (EF);

- Latest Finish (LF);

- Total Float (TF).

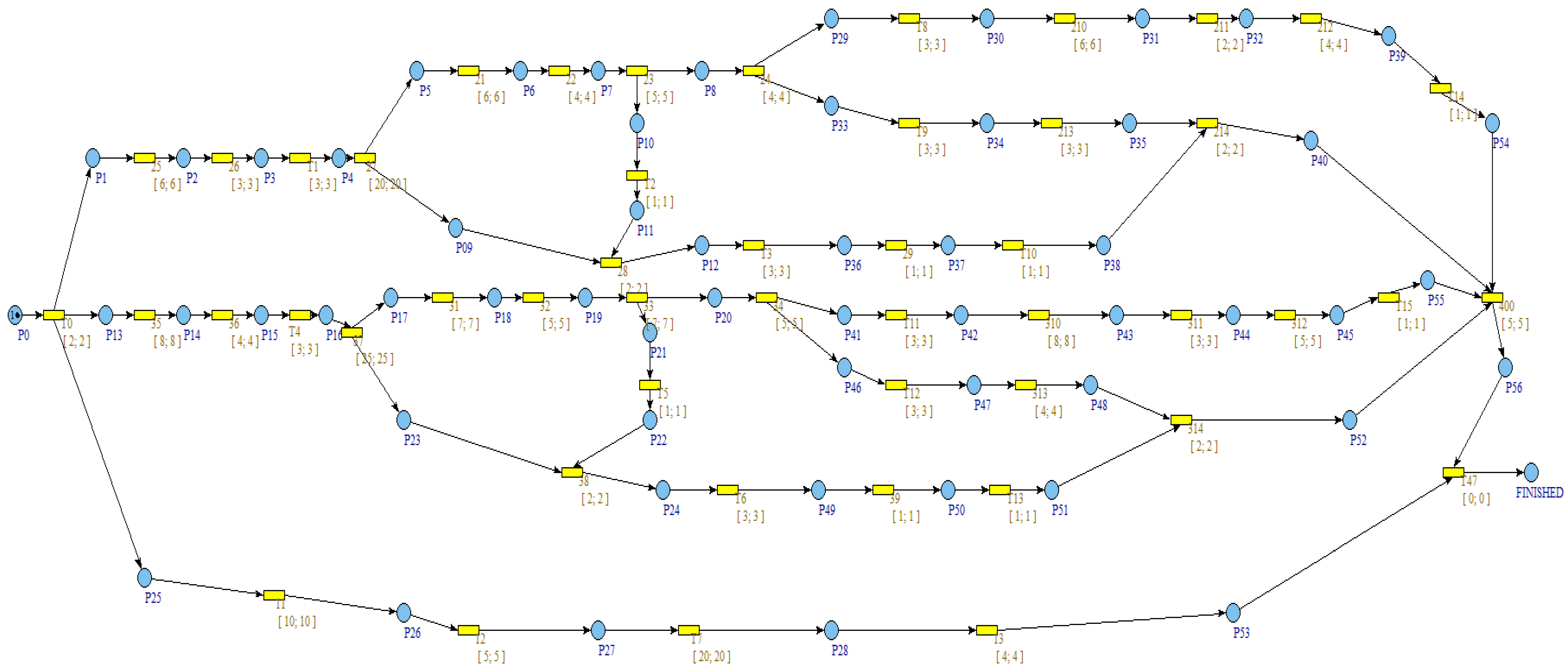

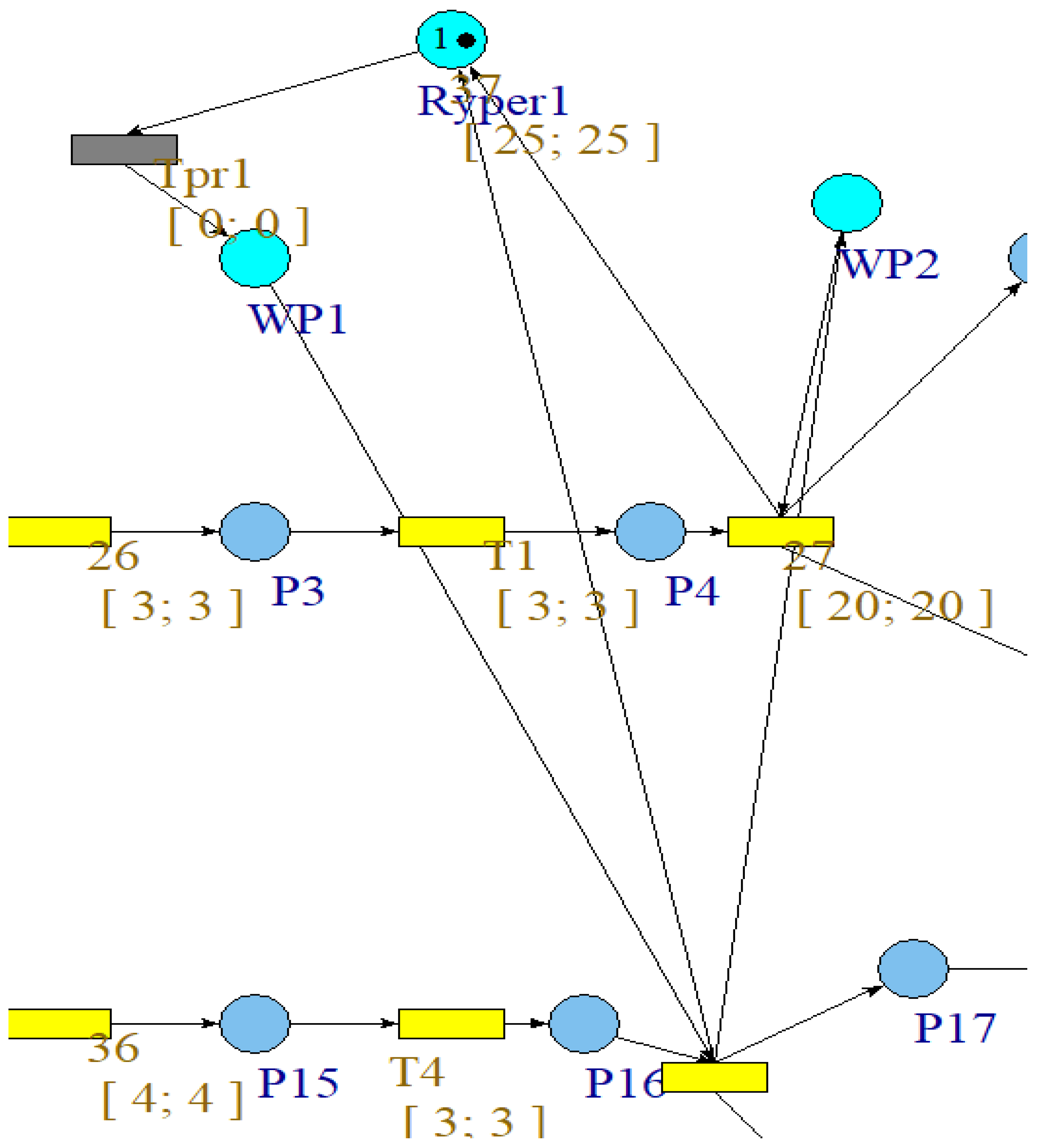

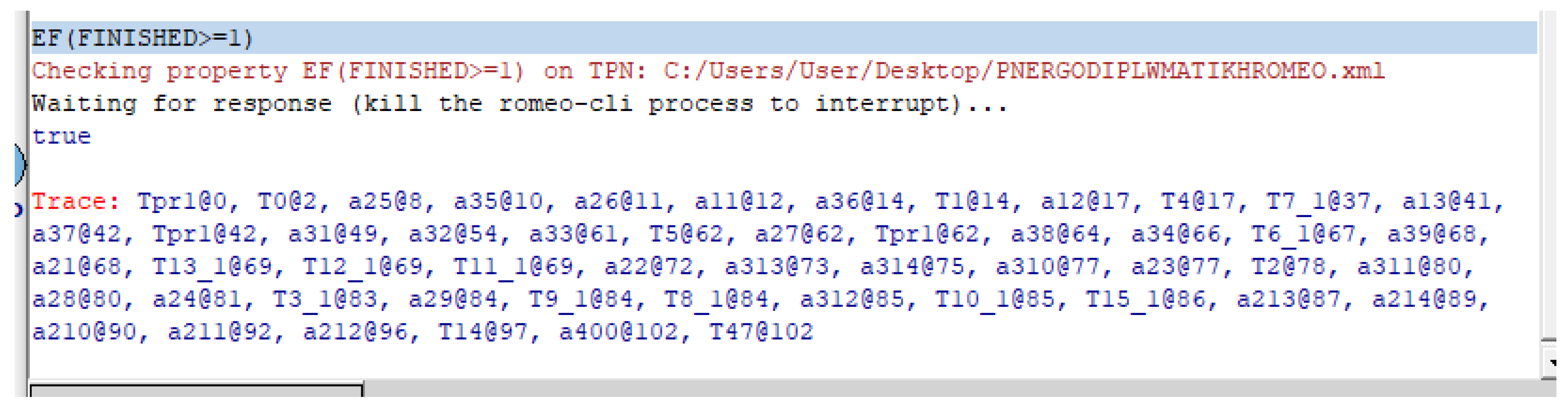

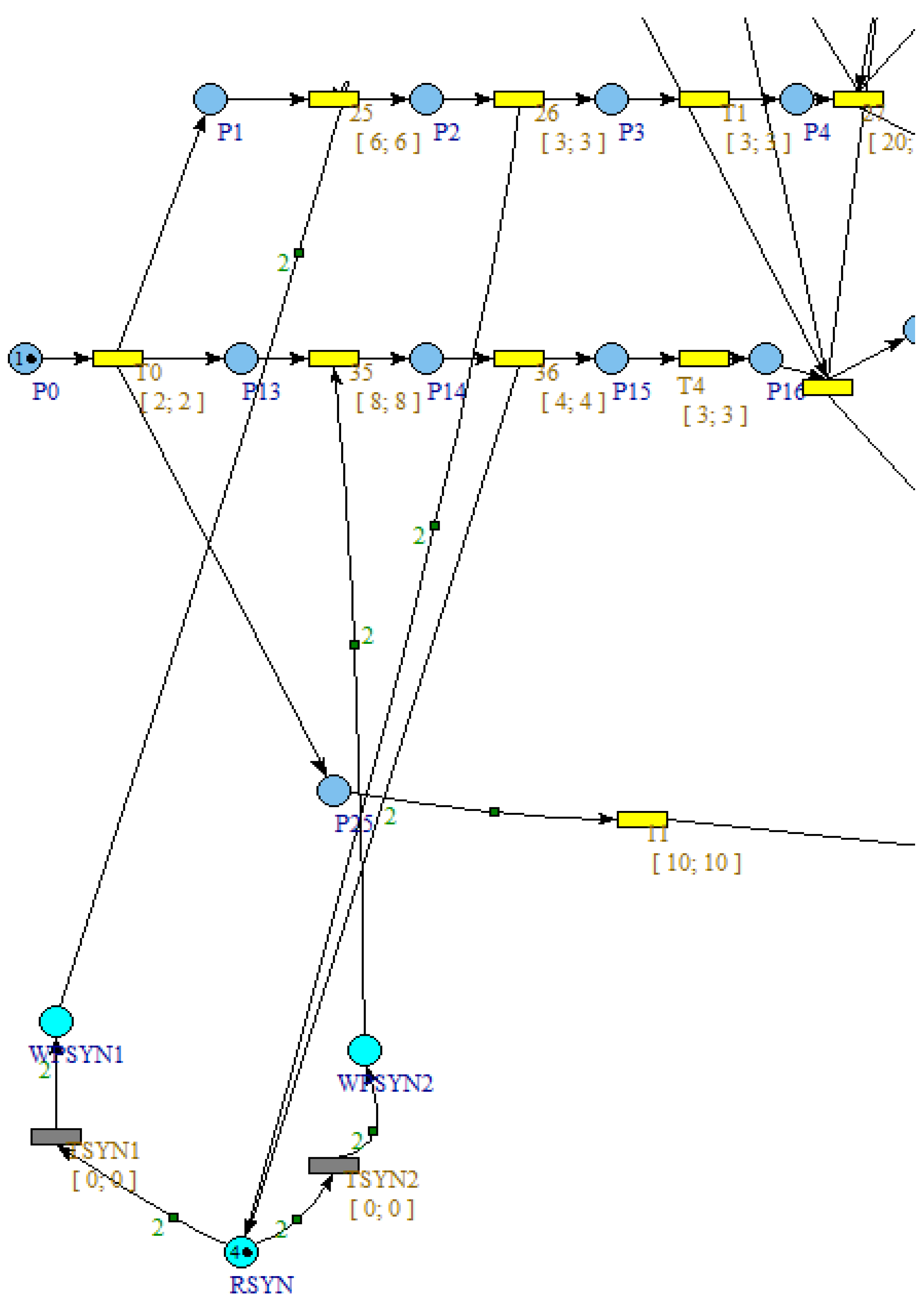

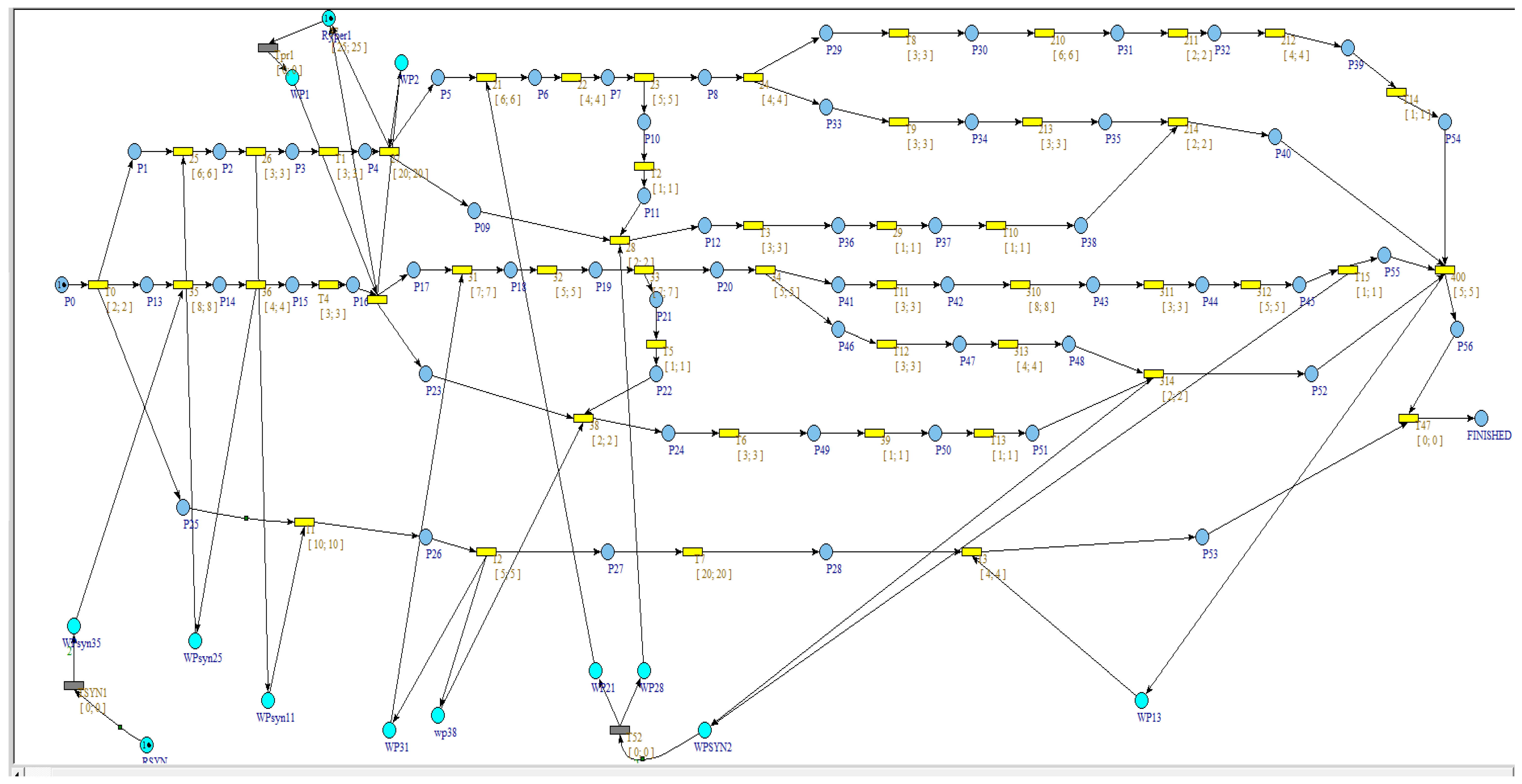

4.3. Project Management Using Petri Nets

4.4. Simulation Using ROMEO Software

5. Resource Constraints

5.1. Resource Constraint on Subcontractor

5.2. Resource Constraint on Coating Crew

5.3. Resource Constraint on the Availability of One Coating Crew

6. Determination of the Optimal Solution

- The project owner has set a completion deadline of 100 working days. Each additional day beyond this deadline incurs a penalty of €1200 per day;

- The cost of one crew amounts to €1000 per day, which includes crew wages, operational expenses such as fuel and consumables, as well as project insurance, administrative costs, and the remuneration of engineers and the safety technician;

- The cost of the second crew is €600 per day, covering both crew wages and work execution expenses (fuel and oil);

- The cost of deploying a third crew for four days is €550 per day;

- The rental cost of an air compressor for the duration of the works is €50 per day;

- The agreement with a single subcontractor for the installation of both tank roofs amounts to a lump sum cost of €30,000;

- The agreement with two subcontractors, one for each roof, results in a total cost of €35,000.

7. Conclusions

Research Limitations and Future Developments

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Resource Capacities

- Maximum number of coating crews available simultaneously: two.

- An additional third crew could be deployed for a maximum duration of four working days.

- One subcontractor is responsible for the installation of both tank roofs.

- Two subcontractors, each responsible for one tank roof.

- One air compressor is available for rental during the execution of the works.

Appendix A.2. Financial Parameters

- Contractual project deadline: 100 working days.

- Penalty for delayed completion: €1200 per working day beyond the contractual deadline.

- Daily cost of one coating crew: €1000, including wages, consumables, insurance, administrative fees, and engineering supervision.

- Daily cost of the second coating crew: €600, including wages and execution-related expenses.

- Daily cost of deploying a third crew (maximum four days): €550.

- Air compressor rental cost: €50 per day.

- Single subcontractor for both tank roofs: lump-sum cost of €30,000.

- Two subcontractors (one per roof): total lump-sum cost of €35,000.

Appendix A.3. Cost Calculation Methodology

- Crew costs = Crew costs = (daily rate1 × crew1 × days) + (daily rate2 × crew2 × days) + (daily rate3 × crew3 × days);

- Subcontractor cost = lump sum per scenario;

- Rental equipment = daily rate × number of days;

- Penalty cost = max(0, project duration − contractual deadline) × daily penalty rate.

References

- Key Differences. Difference Between PERT and CPM (with Comparison Chart). Available online: https://keydifferences.com/difference-between-pert-and-cpm.html (accessed on 5 March 2025).

- Kumanan, S.; Raja, K. Modeling and simulation of projects with Petri nets. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2008, 5, 1742–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, N.Y.; Hsu, N.P.; Chang, N.Y. A Petri net approach to support resource assignment in project management. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. A Syst. Hum. 2008, 38, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boushaala, A. An approach for project scheduling using PERT/CPM and Petri nets (PNs) tools. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Operations Management, Bali, Indonesia, 7–9 January 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Dai, H. Applying Petri nets on project management. Univ. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 2, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.L. Petri Net Theory and the Modeling of Systems; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, V.R.; Chung, Y.F.; Chen, S.; Guo, J. A novel reduction approach for Petri net systems based on matching theory. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 4562–4576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T. Petri nets: Properties, analysis and applications. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 541–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, G.; Niño, K.; Montoya, C.; Sánchez, M.A.; Palacios, J.; Amodeo, L. A Petri net-based framework for realistic project management and scheduling: An application in animation and videogames. Comput. Oper. Res. 2015, 66, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Τσιναράκης, Γ. Modeling and Study of Random-Topology Production Systems Using Petri Nets: A Hierarchical Control Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, Technical University of Crete, Chania, Greece, 2007. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- Bergenthum, R. Firing Partial Orders in a Petri Net. In Proceedings of the PETRI NETS 2021 Application and Theory of Petri Nets and Concurrency, Online, 23–25, June 2021; Buchs, D., Carmona, J., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 12734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsinarakis, G.J. Modeling task dependencies in project management using Petri nets with arc extensions. In Proceedings of the 26th Mediterranean Conference on Control and Automation (MED), Zadar, Croatia, 19–22 June 2018; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. Timed Petri Nets: Theory and Application; Springer Science+Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramchandani, C. Analysis of Asynchronous Concurrent Systems by Timed Petri Nets. Master’s Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/13739 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Bowden, F.D.J. A brief survey and synthesis of the roles of time in Petri nets. Math. Comput. Model. 2000, 31, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinaldo, J.; Del Foyo, P.M.G. Timed Petri nets. In Petri Nets—Manufacturing and Computer Science; InTech: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Desrochers, A.A. Task planning and project management using Petri nets. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Assembly and Task Planning, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 10–11 August 1995; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 265–271. [Google Scholar]

- Wakefield, R.R.; Sears, G.A. Petri nets for simulation and modeling of construction systems. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 1997, 123, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, A. Petri Net based simulation of construction schedules. In Proceedings of the 1997 Winter Simulation Conference, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–10 December 1997; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1997; pp. 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, A.; Mund, A.; Marble, J. Simulation of the structural steel erection process. In Proceedings of the 1999 Winter Simulation Conference, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 5–8 December 1999; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 1999; Volume 2, pp. 942–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Y.; Zwikael, O. Modelling and scheduling projects using Petri nets. Int. J. Proj. Organ. Manag. 2008, 1, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salimifard, K.; Jamali, G.; Behbahaninezhad, S. Managing time and resources of construction projects using colored Petri nets and a genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Automation, Computational and Technology Management (ICACTM), Chennai, India, 26–28 April 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. Coloured Petri Nets: Basic Concepts, Analysis Methods and Practical Use; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; Volume 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Ciarapica, F.E.; Giovanni, M. Timed coloured Petri nets for modelling and managing processes and projects. Procedia CIRP 2018, 67, 58–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, H. A hybrid soft computing technique by using fuzzy Petri nets to optimise the critical path in management problem. Int. J. Appl. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Zhou, M.; Lu, X.S.; Abusorrah, A. Scheduling of resource allocation systems with timed Petri nets: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarnova, T.V.; Beloshitskiy, A.A.; Kashirina, I.L. Application of Bayesian networks and Petri nets apparatus for the study of projects implementation calendar plans. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1902, 012095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzuto, G.; Bevilacqua, M. A decision-making application for project management through timed coloured Petri nets. Int. J. Manag. Decis. Mak. 2018, 17, 447–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Cheng, J.; Wang, Y.; Gao, S. Time performance optimization and resource conflicts resolution for multiple project management. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 2016, E99-D, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, K. Resource management modelling and simulating of construction project based on Petri net. Comput. Model. New Technol. 2014, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Shan, B. (Eds.) The application of Petri nets to construction project management. In Advances in Intelligent and Soft Computing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.B.; Chen, Y.Q.; Zhu, X.Y. Risk management for construction projects with colored Petri nets: An agent-based modeling framework. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Hong Kong, China, 10–13 December 2012; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 2008–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samkari, K.; Kugler, M.; Kordi, B.; Franz, V. Colored Petri-net and multi-agents: A combination for a time-efficient evaluation of a simulation study in construction management. In Proceedings of the 2012 ASCE International Conference on Computing in Civil Engineering, Clearwater Beach, FL, USA, 17–20 June 2012; Issa, R.R., Flood, I., Eds.; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA, USA, 2012; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, T.-H. Modeling of Construction Scheduling with Coloured Petri Nets. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Process Automation, Control and Computing, Coimbatore, India, 20–22 July 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.F.; Wang, Y.W.; Ling, X.Z.; Bai, Y. A Petri net simulation model for virtual construction of earthmoving operations. Autom. Constr. 2011, 20, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subulan, K.; Saltabas, A.; Taşan, A.S.; Girgin, S.C. Modeling and analyzing of a construction project considering resource allocation through a hybrid methodology: Petri Nets and fuzzy rule-based systems. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Computers and Industrial Engineering (CIE41), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 23–25 October 2011; Curran Associates: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 317–322. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhuang, X.-C.; Song, G.-H.; Xu, X.-D.; Li, C.-X. Solving resource-constrained multiple project scheduling problem using timed colored Petri nets. J. Shanghai Jiaotong Univ. (Sci.) 2009, 14, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adida, E.; Joshi, P. A robust optimisation approach to project scheduling and resource allocation. Int. J. Serv. Oper. Informatics 2009, 4, 169–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biruk, S.; Jaśkowski, P. Simulation modelling construction project with repetitive tasks using Petri nets theory. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2008, 9, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, K.; Casavant, A. Analysis of timed Petri nets for reachability in construction applications. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2008, 14, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salum, L. Petri nets and time modelling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2008, 38, 377–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haji, M.; Darabi, H. Petri net based supervisory control reconfiguration of project management systems. In Proceedings of the 2007 IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 22–25 September 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; pp. 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, H.-P.; Hsieh, B.; Yeh, Y. A Petri-net based approach for scheduling and rescheduling resource-constrained multiple projects. J. Chin. Inst. Ind. Eng. 2006, 23, 468–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahrour, R.; Franz, V. Seamless Data Model for a CAD-Based Simulation System. In Proceedings of the Joint International Conference on Computing and Decision Making in Civil and Building Engineering, Montréal, QC, Canada, 14–16 June 2006; pp. 3958–3967. [Google Scholar]

- Sawhney, A.; Mund, A.; Chaitavatputtiporn, T. Petri net-based scheduling of construction projects. Civ. Eng. Environ. Syst. 2003, 20, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, J.P.; Kumanan, S.; Krishnaiah Chetty, O.V. Application of Petri nets and a genetic algorithm to multi-mode multi-resource constrained project scheduling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2001, 17, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawhney, A.; Vamadevan, A. Petri Net-Based Scheduling of a Bridge Project. In Proceedings of Construction Congress VI: Building Together for a Better Tomorrow in an Increasingly Complex World, Orlando, FL, USA, 20–22 February 2000; American Society of Civil Engineers: Orlando, FL, USA, 2000; Volume 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, K.M.; Biruk, S. A model of construction project based on Petri nets theory. Arch. Civ. Eng. 2000, 46, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ukamaka, C.O. Implementation of project evaluation and review technique (PERT) and critical path method (CPM): A comparative study. Int. J. Ind. Oper. Res. 2020, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ROMEO—Formal Verification and Synthesis for Parametric Timed Systems. Available online: https://romeo.ls2n.fr/ (accessed on 14 November 2025).

| Criterion | CPM | PERT | Timed Petri Nets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modeling Time | Relatively low modeling effort due to simple activity–precedence representation and deterministic durations. | Moderate modeling effort, as probabilistic duration estimates require additional assumptions and data. | Higher initial modeling effort, as activities, resources, timing, and concurrency must be explicitly defined within a formal structure. |

| Ease of Updating | Limited flexibility; changes in activity durations or logic often require partial or full network reconstruction. | Updates are possible but recalculation of probabilistic estimates may be required, reducing responsiveness to dynamic changes. | High flexibility; model updates can be incorporated locally, and dynamic behavior can be re-simulated without redesigning the entire structure. |

| Ability to Handle Constraints | Primarily precedence-based; resource constraints are not inherently supported and require external heuristics. | Similar limitations to CPM, with no native mechanism for modeling resource interactions or complex constraints. | Strong capability to explicitly represent resource constraints, synchronization, mutual exclusion, and concurrency within the modeling formalism. |

| Computational Efficiency | High computational efficiency for large-scale projects due to simple longest-path calculations. | Moderate efficiency: probabilistic calculations increase computational complexity. | Potentially lower efficiency for large models due to state-space growth, though suitable abstractions and tools can mitigate this issue. |

| Activity | Code | Duration | Predecessor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site installation | 0 | 2 | |

| Sandblasting of pipelines in pipe rack | 1.1 | 10 | 0 |

| Painting of pipelines in pipe rack | 1.2 | 5 | 1.1 |

| Touch-up painting on weld joints | 1.3 | 4 | 1.2 (fs* + 20) |

| Erection of scaffolding for tank T1 | 2.1 | 6 | 2.7 |

| Erection of scaffolding for tank T2 | 3.1 | 7 | 3.7 |

| Covering of scaffolding with material to prevent dust dispersion T1 | 2.2 | 4 | 2.1 |

| Covering of scaffolding with material to prevent dust dispersion T2 | 3.2 | 5 | 3.1 |

| Sandblasting of external shell T1 | 2.3 | 5 | 2.2 |

| Painting of external shell T1 | 2.4 | 4 | 2.3 |

| Sandblasting of roof sheets T1 | 2.5 | 6 | 0 |

| Painting of roof sheets T1 | 2.6 | 3 | 2.5 |

| Installation of roof sheets T1 | 2.7 | 20 | 2.6 (fs + 3) |

| Touch-up painting on weld joints T1 | 2.8 | 2 | 2.7, 2.3 (fs + 1) |

| Application of anti-slip material on the roof T1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.8 (fs + 3) |

| Sandblasting of bottom plates T1 | 2.10 | 6 | 2.4 (fs + 3) |

| Cleaning of the bottom from sandblasting material T1 | 2.11 | 2 | 2.10 |

| Painting of the bottom T1 | 2.12 | 4 | 2.11 |

| Dismantling of scaffolding T1 | 2.13 | 3 | 2.4 (fs + 3) |

| Painting of fire-fighting pipelines, marking and painting of handrails T1 | 2.14 | 2 | 2.13, 2.9 (fs + 1) |

| Sandblasting of external shell T2 | 3.3 | 7 | 3.2 |

| Painting of the external shell T2 | 3.4 | 5 | 3.3 |

| Sandblasting of roof sheets T2 | 3.5 | 8 | 0 |

| Painting of roof sheets T2 | 3.6 | 4 | 3.5 |

| Installation of tank roof T2 | 3.7 | 25 | 3.6 (fs + 3) |

| Repair/touch-up painting of weld joints on the roof T2 | 3.8 | 2 | 3.7, 3.3 (fs + 1) |

| Application of anti-slip material on the roof T2 | 3.9 | 1 | 3.8 (fs + 3) |

| Sandblasting of bottom plates T2 | 3.10 | 8 | 3.4 (fs + 3) |

| Cleaning of the bottom from sandblasting material T2 | 3.11 | 3 | 3.10 |

| Painting of the bottom T2 | 3.12 | 5 | 3.11 |

| Dismantling of scaffolding T2 | 3.13 | 4 | 3.4 (fs + 3) |

| Painting of fire-fighting pipelines, marking and painting of handrails T2 | 3.14 | 2 | 3.13, 3.9 (fs + 1) |

| Cleaning of site from sandblasting material | 4 | 5 | 3.12 (fs + 1), 2.12 (fs + 1), 3.13, 2.13 |

| Project Completion | 0 | 4 |

| Code | Duration | Previous Activity | ES | EF | LS | LF | TF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1.1 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 12 | 52 | 62 | 50 |

| 1.2 | 5 | 1.1 | 12 | 17 | 62 | 67 | 50 |

| 1.3 | 4 | 1.2 (fs + 20) | 37 | 41 | 87 | 91 | 50 |

| 2.1 | 6 | 2.7 | 34 | 40 | 51 | 57 | 17 |

| 3.1 | 7 | 3.7 | 42 | 49 | 42 | 49 | 0 |

| 2.2 | 4 | 2.1 | 40 | 44 | 57 | 61 | 17 |

| 3.2 | 5 | 3.1 | 49 | 54 | 49 | 54 | 0 |

| 2.3 | 5 | 2.2 | 44 | 49 | 61 | 66 | 17 |

| 2.4 | 4 | 2.3 | 49 | 53 | 66 | 70 | 17 |

| 2.5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 19 | 25 | 17 |

| 2.6 | 3 | 2.5 | 8 | 11 | 25 | 28 | 17 |

| 2.7 | 20 | 2.6 (fs + 3) | 14 | 34 | 31 | 51 | 17 |

| 2.8 | 2 | 2.7, 2.3 (fs + 1) | 50 | 52 | 77 | 79 | 27 |

| 2.9 | 1 | 2.8 (fs + 3) | 55 | 56 | 82 | 83 | 27 |

| 2.10 | 6 | 2.4 (fs + 3) | 56 | 62 | 73 | 79 | 17 |

| 2.11 | 2 | 2.10 | 62 | 64 | 79 | 81 | 17 |

| 2.12 | 4 | 2.11 | 64 | 68 | 81 | 85 | 17 |

| 2.13 | 3 | 2.4 (fs + 3) | 56 | 59 | 81 | 84 | 25 |

| 2.14 | 2 | 2.13, 2.9 (fs + 1) | 59 | 61 | 84 | 86 | 25 |

| 3.3 | 7 | 3.2 | 54 | 61 | 54 | 61 | 0 |

| 3.4 | 5 | 3.3 | 61 | 66 | 61 | 66 | 0 |

| 3.5 | 8 | 0 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| 3.6 | 4 | 3.5 | 10 | 14 | 10 | 14 | 0 |

| 3.7 | 25 | 3.6 (fs + 3) | 17 | 42 | 17 | 42 | 0 |

| 3.8 | 2 | 3.7, 3.3 (fs + 1) | 62 | 64 | 77 | 79 | 15 |

| 3.9 | 1 | 3.8 (fs + 3) | 67 | 68 | 82 | 83 | 15 |

| 3.10 | 8 | 3.4 (fs + 3) | 69 | 77 | 69 | 77 | 0 |

| 3.11 | 3 | 3.10 | 77 | 80 | 77 | 80 | 0 |

| 3.12 | 5 | 3.11 | 80 | 85 | 80 | 85 | 0 |

| 3.13 | 4 | 3.4 (fs + 3) | 69 | 73 | 80 | 84 | 11 |

| 3.14 | 2 | 3.13, 3.9 (fs + 1) | 73 | 75 | 84 | 86 | 11 |

| 4 | 5 | 3.12 (fs + 1), 2.12 (fs + 1), 3.13, 2.13 | 86 | 91 | 86 | 91 | 0 |

| Scenario | Coating Crew (Qty) | Subcontractor Crew (Qty) | Air Compressor Rental (Qty) | Deploying of 3rd Crew (Days) | Duration of Project (Days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 130 |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 106 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 102 |

| 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 95 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 91 |

| Scenario | Coating Crew Cost | Subcontractor Crew Cost | Air Compressor Rental Cost | Deploying the 3rd Crew Cost | Penalty Cost | Total Project Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | €130.000 | €30.000 | €0 | €0 | €36.000 | €196.000 |

| 2 | €169.600 | €30.000 | €5.300 | €0 | €7.200 | €212.100 |

| 3 | €163.200 | €30.000 | €5.100 | €2.200 | €2.400 | €202.900 |

| 4 | €152.000 | €35.000 | €4.750 | €0 | €0 | €191.750 |

| 5 | €145.600 | €35.000 | €4.550 | €2.200 | €0 | €187.350 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Katsangelos, D.; Petroutsatou, K. Enhanced Sustainability of Projects Based on Dynamic Time Management Using Petri Nets. Sustainability 2026, 18, 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031644

Katsangelos D, Petroutsatou K. Enhanced Sustainability of Projects Based on Dynamic Time Management Using Petri Nets. Sustainability. 2026; 18(3):1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031644

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatsangelos, Dimitrios, and Kleopatra Petroutsatou. 2026. "Enhanced Sustainability of Projects Based on Dynamic Time Management Using Petri Nets" Sustainability 18, no. 3: 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031644

APA StyleKatsangelos, D., & Petroutsatou, K. (2026). Enhanced Sustainability of Projects Based on Dynamic Time Management Using Petri Nets. Sustainability, 18(3), 1644. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18031644