1. Introduction

The global shift toward sustainable development has placed environmental accountability at the forefront of corporate strategies and national economic planning. For Saudi Arabia, this transition holds particular significance, as the Kingdom pursues economic diversification through Vision 2030, its ambitious reform program aimed at reducing oil dependency and building a sustainable, investment-attractive economy [

1]. Recent evidence from Saudi regions demonstrates that sustainable development increasingly depends on knowledge economy factors and innovation capabilities [

2], suggesting that environmental accounting practices may constitute strategic knowledge-based resources for economic transformation. Accordingly, the integration of environmental disclosure and green accounting practices represents a critical institutional and managerial pathway to achieving these transformation goals while meeting international sustainability standards.

Saudi Vision 2030 explicitly recognizes environmental sustainability as a pillar of economic development, establishing targets for renewable energy adoption, carbon emission reduction, and ecological preservation [

3]. The Saudi Green Initiative, launched as part of this broader vision, commits the Kingdom to achieving net-zero emissions by 2060 and positions environmental stewardship as essential to economic competitiveness [

4]. This evolving policy framework creates both regulatory pressure and strategic opportunity for Saudi firms to adopt robust environmental reporting mechanisms, as international research demonstrates that green accounting practices significantly influence financial sustainability across diverse contexts [

5].

Environmental disclosure and green accounting serve distinct yet interrelated functions in corporate sustainability. Environmental disclosure involves communicating environmental impacts, risks, and management strategies to stakeholders through various reporting channels [

6]. Green accounting extends beyond disclosure to encompass the systematic measurement, valuation, and integration of environmental costs and benefits into financial decision-making processes [

7]. As Cho and Patten argue, green accounting reflects broader CSR and environmental disclosure perspectives, although a critical examination reveals tensions between symbolic reporting and substantive accountability [

8]. Recent advances further conceptualize green accounting as an integrated managerial system that links disclosure, performance measurement, and internal control mechanisms [

9]. Together, these practices enable organizations to quantify their ecological footprint, demonstrate accountability, and attract sustainability-oriented investment.

The relationship between environmental reporting and investment attractiveness has gained prominence as global capital markets increasingly incorporate environmental, social, and governance (ESG) criteria into investment decisions [

10]. Investors recognize that firms with strong environmental practices often demonstrate superior risk management, operational efficiency, and long-term value creation potential [

11]. Recent evidence indicates that green accounting management mediates the relationship between stakeholder pressure and financial performance, drawing on integrated explanatory perspectives from stakeholder theory and the natural resource-based view [

12]. Moreover, carbon emission disclosure and environmental performance collectively enhance corporate value, particularly in resource-intensive sectors [

13]. These theoretical foundations, which underpin the hypothesized relationships in this study, are discussed in detail in

Section 2.1 to enhance conceptual clarity and avoid ambiguity.

Despite the growing recognition of the importance of environmental reporting, empirical evidence on its economic impact in emerging markets remains limited. Previous studies have primarily focused on developed economies with established sustainability reporting traditions [

14], often emphasizing direct financial outcomes while overlooking underlying transmission mechanisms. However, emerging evidence from developing contexts provides valuable insights, with studies from Bangladesh demonstrating that social responsibility disclosure mediates the relationship between green accounting implementation and sustainable development [

15]. The Saudi context presents unique characteristics, including rapid regulatory evolution, cultural factors influencing corporate transparency, and the dual challenge of maintaining energy sector competitiveness while pursuing sustainability goals [

16]. Furthermore, the documented role of ICT and innovation as mediating factors in sustainable development relationships [

17] suggests that firm-level capabilities may critically shape how environmental practices translate into economic and investment-related outcomes.

Against this backdrop, three interrelated research gaps emerge. First, empirical evidence on the economic consequences of environmental disclosure and green accounting in emerging economies—particularly in Gulf countries undergoing rapid institutional transformation—remains scarce. Second, prior studies have largely focused on direct relationships, providing limited insight into the mediating role of sustainable economic outcomes in linking environmental practices to investment attractiveness. Third, despite the centrality of national development strategies, the moderating role of strategic alignment with Saudi Vision 2030 has not been empirically tested at the firm level.

This study addresses these gaps by investigating how environmental disclosure and green accounting practices influence sustainable economic outcomes and investment attractiveness among listed Saudi firms. We examine whether these environmental reporting mechanisms contribute to Vision 2030’s objective of creating a resilient, diversified economy that attracts international investment while maintaining ecological integrity. Specifically, this study offers three contributions. First, it provides empirical evidence on the economic implications of environmental reporting in an emerging market context. Second, it clarifies the mediating role of sustainable economic outcomes in translating environmental practices into investment attractiveness. Third, it empirically assesses whether alignment with Vision 2030 strengthens these relationships, thereby extending the literature on sustainability, environmental accounting, and strategic national development frameworks.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Preliminary Analysis

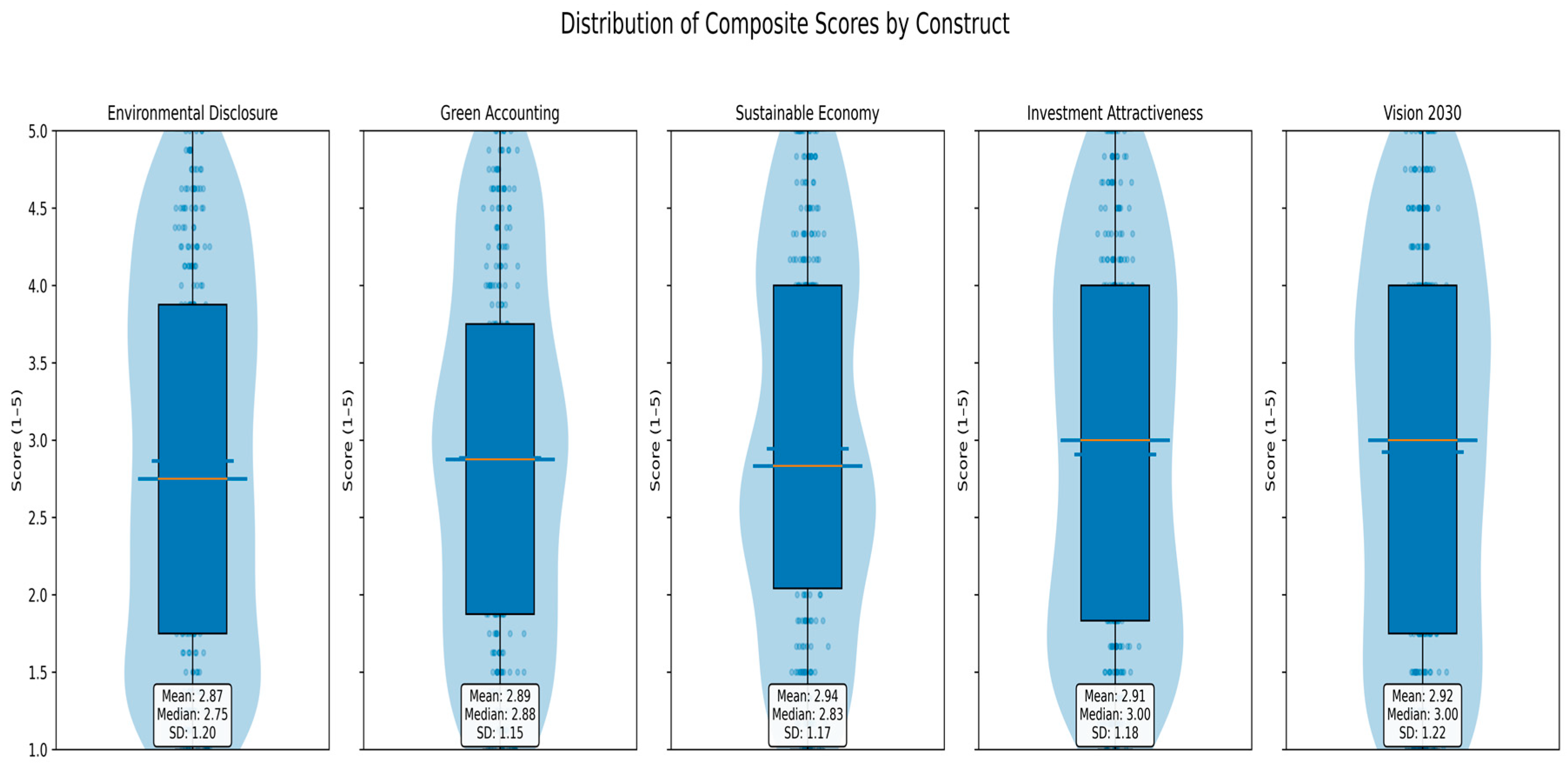

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics, reliability measures, and bivariate correlations of the study variables. The mean scores for all constructs ranged from 2.866 to 2.944 on a five-point scale, indicating that respondents generally reported moderate to relatively low levels of environmental disclosure, green accounting practices, and related outcomes. These central tendency measures, which fall below the scale midpoint of 3.0, suggest that Saudi firms have not yet fully institutionalized environmental reporting practices or their integration into investment-related decision-making processes.

The standard deviations (ranging from 1.152 to 1.221) indicate reasonable variability in the responses, with Vision 2030 showing the highest dispersion (SD = 1.221). This dispersion reflects substantial heterogeneity among firms in terms of both environmental practice adoption and strategic alignment with national sustainability objectives. All constructs demonstrated strong internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. Environmental disclosure exhibited the highest reliability (α = 0.925), followed by green accounting (α = 0.916). The AVE values, whose square roots appear on the diagonal of

Table 2, ranged from 0.630 to 0.656, confirming adequate convergent validity.

The correlation analysis revealed several noteworthy relationships. Environmental disclosure and green accounting showed the strongest association (r = 0.524, p < 0.001), indicating that firms implementing one type of environmental practice tend to adopt others concurrently. Sustainable economic outcomes correlated most strongly with investment attractiveness (r = 0.462, p < 0.001), providing preliminary support for its hypothesized mediating role in the model. Of particular interest is the non-significant correlation between Vision 2030 alignment and investment attractiveness (r = 0.080, ns), suggesting that strategic alignment with national sustainability initiatives, in isolation, may not directly translate into enhanced investment appeal.

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution patterns using violin plots combined with box plots. The distributions appeared relatively symmetric for most constructs, with median values closely aligned with the mean. The wider portions of the violin plots around the 2–3 range indicate a concentration of responses in the lower-to-moderate range of the scale. This distributional pattern is consistent with the descriptive statistics and reinforces the conclusion that environmental practices are unevenly adopted across firms.

Figure 2 presents detailed item-level response distributions across the five-point Likert scale. The stacked bar charts show that negative evaluations—comprising strongly disagree and disagree responses—consistently account for approximately 40–55% of responses across most items. Neutral responses represent around 13–23%, while positive responses (agree and strongly agree) generally range between 30–45%. The dashed horizontal reference line highlights that mean item scores remain below the scale midpoint of 3.0 across all constructs, indicating moderate-to-low perceived implementation levels. Overall, the distributions suggest that although elements of environmental disclosure, green accounting, and sustainability-oriented practices are present among some firms, their adoption remains uneven and insufficiently institutionalized across the sample.

Environmental disclosure items (ED1–ED8) show considerable variation, with ED1 and ED2 displaying the highest disagreement rates (approximately 55%), while ED7 and ED8 demonstrate more balanced distributions. This pattern suggests selective rather than comprehensive adoption of disclosure practices, with firms potentially prioritizing certain types of environmental reporting over others. Green accounting items (GA1–GA8) exhibit similar heterogeneity, with GA8 showing particularly low implementation levels, indicating that some accounting-based sustainability practices may face higher organizational or technical barriers. The sustainable economy items (SE1–SE6) display more uniform response patterns; however, SE1 shows notably higher disagreement, which may reflect early-stage challenges in translating environmental initiatives into measurable economic outcomes rather than a lack of sustainability intent.

4.2. Measurement Model Assessment

The measurement model was evaluated using PLS-SEM to confirm its reliability and validity before hypothesis testing.

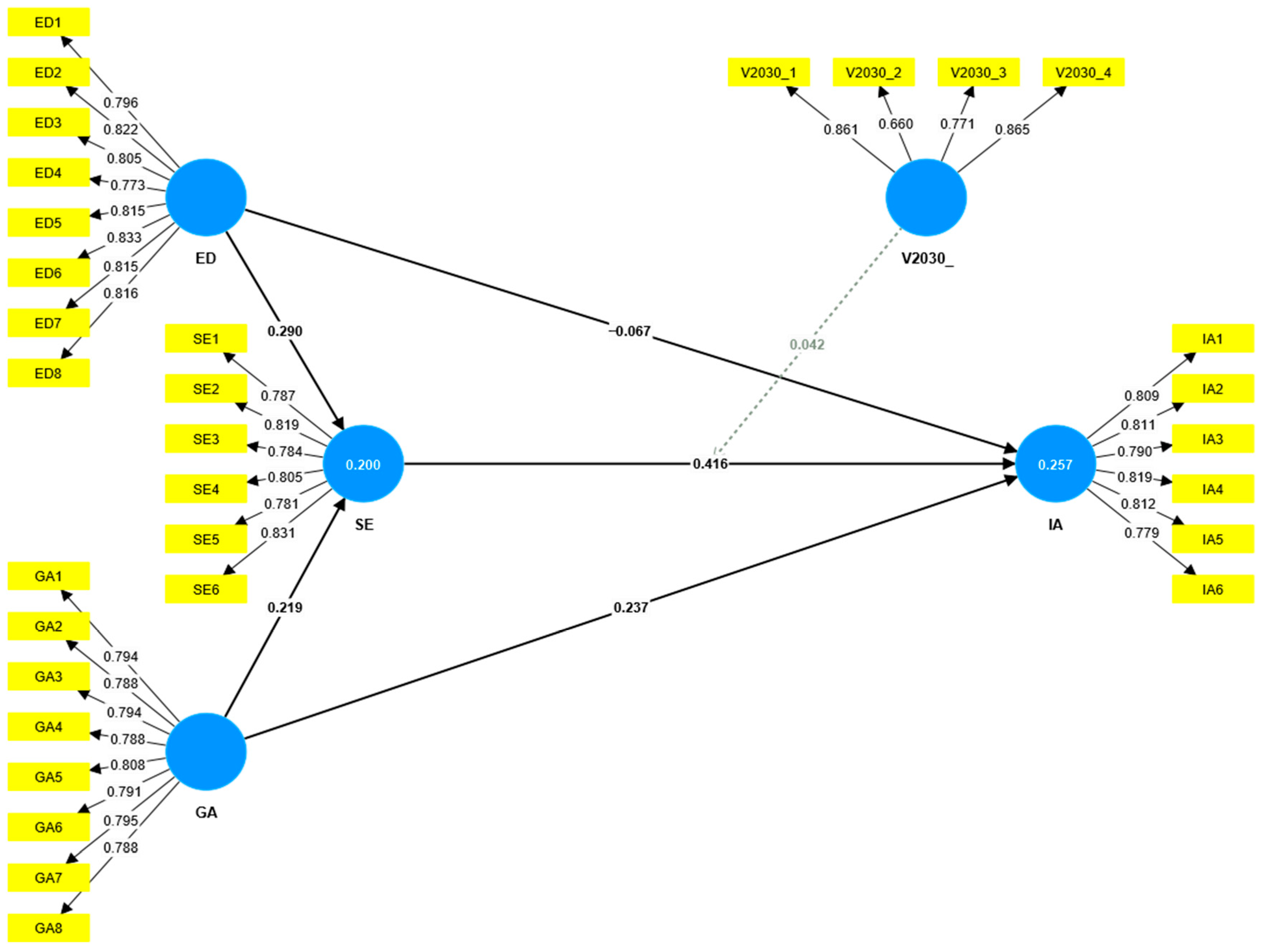

Figure 3 presents the structural model with standardized loadings and path coefficients. This assessment was conducted to ensure the adequacy of the measurement properties prior to interpreting the structural relationships.

All factor loadings exceeded the recommended threshold of 0.70, ranging from 0.773 to 0.833 for environmental disclosure, 0.788 to 0.808 for green accounting, 0.779 to 0.819 for investment attractiveness, and 0.781 to 0.831 for sustainable economic outcomes. Vision 2030 exhibited greater variability in item loadings (0.660–0.865) but remained within acceptable limits. These results support the appropriateness of the reflective measurement specification adopted for all constructs.

Table 3 confirms the strong reliability of all constructs. Cronbach’s alpha values ranged from 0.814 to 0.925, while composite reliability measures exceeded 0.87. The average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.630 to 0.655, surpassing the 0.50 threshold for convergent validity. Discriminant validity was established, as the square root of the AVE for each construct (0.794–0.810) exceeded all corresponding inter-construct correlations, indicating that the latent variables capture related but conceptually distinct dimensions.

The structural paths illustrated in

Figure 3 reveal differentiated effects across the model. Environmental disclosure positively affects sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.290) but exhibits a small and non-significant direct effect on investment attractiveness (β = −0.067). Green accounting influences both sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.219) and investment attractiveness (β = 0.237). The strongest relationship is observed between sustainable economic outcomes and investment attractiveness (β = 0.416). The moderating effect of Vision 2030 alignment appears minimal and statistically non-significant (β = 0.042). These coefficients indicate statistically meaningful but heterogeneous relationships across the proposed pathways.

The model explains 20.0% of the variance in sustainable economic outcomes (R2 = 0.200) and 25.7% of the variance in investment attractiveness (R2 = 0.257). While these values indicate moderate explanatory power consistent with cross-sectional organizational research, they also suggest that additional firm-specific and contextual factors beyond the scope of the model contribute to investment attractiveness.

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed using the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratio criterion.

Table 4 displays the HTMT values, all of which fall below the conservative threshold of 0.85, thus confirming that the constructs are empirically distinct. This result indicates that each latent variable captures a unique conceptual domain and that multicollinearity between constructs is unlikely to bias the estimated structural relationships.

4.4. Structural Model Results

The structural model analysis revealed significant relationships between the constructs.

Table 5 presents the path coefficients, t-statistics, and

p-values of the hypothesized relationships.

Environmental disclosure has a positive and statistically significant effect on sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.290, p < 0.001), supporting H1. Substantively, this coefficient suggests that higher levels of environmental disclosure are associated with moderately higher sustainable economic outcomes. However, the direct effect of environmental disclosure on investment attractiveness is negative and not statistically significant (β = −0.067, p = 0.291), leading to the rejection of H2. This finding indicates that environmental disclosure alone does not directly enhance firms’ investment attractiveness.

Green accounting practices significantly influence both sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.219, p < 0.001) and investment attractiveness (β = 0.237, p < 0.001), supporting H3 and H4. These coefficients reflect statistically significant but moderate effect sizes, indicating that green accounting contributes to investment attractiveness both directly and through sustainability-related improvements. Sustainable economic outcomes demonstrate a strong positive effect on investment attractiveness (β = 0.416, p < 0.001), supporting H5 and representing the largest direct effect observed in the structural model.

The moderating effect of Vision 2030 alignment on the relationship between sustainable economic outcomes and investment attractiveness is not statistically significant (β = 0.042, p = 0.498), leading to the rejection of H8. This result suggests that, within the present sample, alignment with the national sustainability strategy does not materially strengthen or weaken the sustainability–investment relationship.

4.5. Mediation and Total Effects Analysis

Table 6 presents the comprehensive mediation analysis, including indirect effects through sustainable economic outcomes and total effects that combine direct and indirect pathways.

Panel A of

Table 6 reveals significant indirect effects of both environmental disclosure and green accounting on investment attractiveness through sustainable economic outcomes. Environmental disclosure demonstrates a stronger indirect effect (β = 0.121,

p < 0.001) than green accounting (β = 0.091,

p < 0.01), with both confidence intervals excluding zero, thus confirming the statistical significance of these mediated relationships. These results indicate that both environmental practices exert their influence on investment attractiveness primarily through sustainability-related performance improvements, providing empirical support for H6 and H7.

Panel B presents the total effects, revealing distinct patterns between the two environmental practices. The total effect of environmental disclosure on investment attractiveness remains non-significant (β = 0.054, p = 0.422) despite its statistically significant indirect effect. This pattern arises from the opposing directions of the direct (β = −0.067) and indirect (β = 0.121) effects, which effectively offset each other in the total effect calculation. This configuration is indicative of full mediation, whereby environmental disclosure influences investment attractiveness exclusively through its impact on sustainable economic outcomes.

By contrast, green accounting exhibits a statistically significant total effect on investment attractiveness (β = 0.328, p < 0.001), representing the strongest total relationship observed in the model. This effect comprises both significant direct (β = 0.237) and indirect (β = 0.091) components, indicating partial mediation. The presence of both pathways suggests that green accounting contributes to investment attractiveness through multiple mechanisms, including direct signaling and managerial capability effects, as well as indirect effects operating through sustainability performance.

The relationships between environmental practices and sustainable economic outcomes show consistent positive effects, with environmental disclosure (β = 0.290, p < 0.001) demonstrating a stronger association than green accounting (β = 0.219, p < 0.001). The effect of sustainable economic outcomes on investment attractiveness (β = 0.416, p < 0.001) represents the strongest direct relationship in the model, underscoring its central role as a transmission channel between environmental practices and market perceptions.

Taken together, these findings highlight distinct mechanisms through which environmental practices influence investment attractiveness. Environmental disclosure operates indirectly and conditionally, relying on sustainability performance improvements to affect investment appeal. In contrast, green accounting functions through both direct and indirect channels, suggesting a more complex value creation process. The presence of full mediation for environmental disclosure implies that disclosure alone, in the absence of substantive sustainability outcomes, is insufficient to directly enhance investment attractiveness.

4.6. Model Explanatory Power and Effect Size Analysis

Table 7 presents the model’s explanatory power and effect sizes for the structural relationships.

As shown in Panel A of

Table 7, the model’s explanatory power indicates that the exogenous constructs collectively account for 25.7% of the variance in investment attractiveness (R

2 = 0.257) and 20.0% of the variance in sustainable economic outcomes (R

2 = 0.200). The adjusted R

2 values (0.244 and 0.194, respectively) suggest minimal overfitting, with the slight reductions reflecting appropriate penalization for model complexity. These R

2 values indicate moderate explanatory power, which is typical of cross-sectional organizational research examining complex managerial and institutional phenomena, where multiple contextual and firm-specific factors operate simultaneously beyond the scope of a single model.

Panel B of

Table 7 reveals differentiated effect sizes across the structural paths. The relationship between sustainable economic outcomes and investment attractiveness exhibits the strongest effect (f

2 = 0.185), approaching the threshold for a large effect and highlighting the relative importance of sustainability-related outcomes in shaping investment perceptions. The impact of environmental disclosure on sustainable economic outcomes demonstrates a small-to-medium effect (f

2 = 0.076), suggesting a meaningful but secondary contribution to sustainability performance. Green accounting shows consistently small effects on both sustainable economic outcomes (f

2 = 0.043) and investment attractiveness (f

2 = 0.051), indicating statistically significant but modest practical effects when considered in isolation.

The pattern of effect sizes provides important insights into the relative importance of different pathways. While the direct effects of green accounting are limited in magnitude, its dual pathways to both sustainable economic outcomes and investment attractiveness suggest a cumulative influence operating through multiple channels. The substantially larger effect of sustainable economic outcomes on investment attractiveness, relative to the direct effects of environmental practices, reinforces the mediating role of sustainability performance in translating environmental accountability into market valuation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Environmental Disclosure and Sustainable Economy Outcomes

The positive relationship between environmental disclosure and sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.290,

p < 0.001) represents a relatively stronger effect within the proposed model, exceeding that of green accounting (β = 0.219). This finding is consistent with stakeholder-oriented interpretations of environmental reporting [

18], while extending these insights to the Saudi context. The observed effect size (f

2 = 0.076) indicates a small-to-medium practical impact, suggesting that environmental disclosure contributes meaningfully—but not dominantly—to sustainability performance alongside other organizational and institutional factors.

These findings parallel evidence from Bangladesh, where environmental and social disclosure mechanisms were shown to mediate sustainable development outcomes [

15]. The comparatively weaker relationship observed in Saudi Arabia may reflect contextual differences, including regulatory maturity and sectoral composition. Indeed, the mean environmental disclosure score (M = 2.866) suggests that reporting practices remain uneven and not yet fully institutionalized across Saudi firms.

The mechanisms linking disclosure to sustainability outcomes appear multifaceted. Environmental reporting requires systematic data collection, performance monitoring, and internal accountability, which can expose inefficiencies and encourage operational improvements [

39]. However, the moderate explanatory power of the model (R

2 = 0.200 for sustainable economic outcomes) indicates that disclosure alone explains only part of sustainability performance. This contrasts with findings from resource-intensive sectors where disclosure explains a larger share of sustainability variance [

13], highlighting sectoral and institutional contingencies.

The relatively lower disclosure mean compared to green accounting suggests that external reporting may lag behind internal environmental management. This pattern likely reflects cautious disclosure behavior in a regulatory environment that is still evolving rather than an absence of environmental engagement.

5.2. Green Accounting’s Dual Impact

Green accounting demonstrates significant effects on both sustainable economic outcomes (β = 0.219,

p < 0.001) and investment attractiveness (β = 0.237,

p < 0.001), indicating a dual value-creation pathway not observed for environmental disclosure. This finding extends integrated stakeholder and resource-based interpretations by showing that green accounting simultaneously supports accountability and internal capability development [

12].

Compared with evidence from Indonesian firms, where stronger effects have been reported [

5], the slightly lower coefficients observed here may reflect the early stage of green accounting adoption in Saudi Arabia. The mean green accounting score (M = 2.886) indicates partial rather than comprehensive integration of environmental costs into decision-making systems. This contrasts with evidence from Nigeria, where more mature adoption was associated with stronger shareholder-value effects [

31], underscoring the importance of implementation depth.

These results challenge critiques that portray green accounting primarily as symbolic [

8]. Instead, the significant total effect (β = 0.328) suggests a substantive value-creation role, operating through both direct signaling effects and indirect sustainability performance improvements. Nevertheless, the magnitude of these effects remains modest compared with developed market studies, reinforcing the role of institutional context.

The relatively narrow range of green accounting factor loadings (0.788–0.808) indicates consistent implementation across accounting practices. This consistency contrasts with heterogeneity reported in public-sector contexts [

33] and may reflect harmonization through international accounting and reporting standards.

5.3. The Mediating Role of Sustainable Economy Outcomes

The full mediation of environmental disclosure’s effect on investment attractiveness (indirect β = 0.121; direct β = −0.067) is a key contribution of this study. While some prior research identifies direct positive disclosure effects on firm value [

26], the present findings suggest that disclosure without demonstrable sustainability outcomes does not enhance investment appeal. The negative, though non-significant, direct coefficient may reflect investor skepticism toward disclosure perceived as symbolic rather than performance-driven.

In contrast, green accounting exhibits partial mediation, consistent with prior evidence highlighting both signaling and performance-based mechanisms [

35]. Investors may interpret green accounting as an indicator of internal governance quality and strategic foresight rather than mere compliance.

The strong effect of sustainable economic outcomes on investment attractiveness (β = 0.416,

p < 0.001) exceeds estimates reported in some emerging market studies [

2], possibly due to the firm-level focus of this analysis. This finding underscores the central role of sustainability performance as a transmission channel between environmental practices and market valuation.

Overall, the differentiated mediation structures reveal functional distinctions between disclosure-based and accounting-based environmental practices that have received limited empirical attention in prior literature.

5.4. Vision 2030 Alignment: Unexpected Non-Significance

The non-significant moderating effect of Vision 2030 alignment (β = 0.042,

p = 0.498) diverges from theoretical expectations. While innovation and ICT capabilities have been shown to mediate sustainability relationships at regional levels [

17], firm-level alignment with Vision 2030 does not appear to amplify investment-related outcomes in this sample.

The moderate mean score and high variance for Vision 2030 alignment suggest heterogeneous firm engagement with national objectives, which may dilute moderation effects in cross-sectional analysis. Measurement challenges are also evident, as reflected in the lower loading of one indicator.

Unlike prescriptive policy regimes with enforceable benchmarks [

42], Vision 2030 functions as a broad strategic framework rather than a compliance-based instrument. The absence of firm-level enforcement mechanisms may explain why alignment alone does not strengthen the sustainability–investment relationship.

5.5. Implications for Corporate Strategy

The model’s explanatory power (R2 = 0.257 for investment attractiveness) indicates that environmental practices contribute meaningfully—but not exclusively—to investment appeal. Firms should therefore integrate environmental initiatives within broader capability-development strategies rather than treating them as standalone value drivers.

The stronger total effect of green accounting compared with environmental disclosure (0.328 vs. 0.054) suggests a clear strategic priority. Under resource constraints, investments in environmental accounting systems may yield higher returns than expanding disclosure alone, supporting capability-based value-creation arguments.

Item-level results further indicate that foundational practices—such as environmental cost integration—may generate more value than highly sophisticated reporting formats during early adoption stages.

5.6. Policy Implications

The divergent mediation patterns imply differentiated policy approaches. While disclosure mandates enhance transparency, they appear insufficient to stimulate investment without measurable sustainability performance improvements. Policymakers may therefore consider shifting toward performance-based environmental standards.

The weak moderating role of Vision 2030 alignment raises questions about the effectiveness of broad strategic frameworks. More targeted instruments with measurable benchmarks may be required, consistent with evidence from technology-specific policy initiatives [

48].

Given the relative consistency of green accounting practices, formal guidance and standardization of green accounting methodologies may yield greater marginal benefits than further expanding disclosure requirements.

5.7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

The cross-sectional design limits causal inference, particularly regarding the non-significant direct effect of environmental disclosure on investment attractiveness. Longitudinal studies could assess whether this reflects a transitional credibility-building phase or persistent investor skepticism.

The sample of 290 listed firms may not capture SME dynamics, where environmental practice adoption follows different trajectories [

36]. Future research should explicitly examine these segments.

Finally, Vision 2030 alignment was measured perceptually. Incorporating objective indicators—such as emissions intensity or renewable energy adoption—could strengthen future moderation analyses and enhance policy relevance.

6. Conclusions

This study provides empirical evidence of the relationships between environmental disclosure, green accounting practices, sustainable economic outcomes, and investment attractiveness in the context of Saudi Vision 2030. The findings indicate differentiated patterns rather than uniform effects as while both environmental practices contribute to sustainable economic development (jointly explaining 20% of the variance), their pathways to investment attractiveness differ in scope and strength. Environmental disclosure appears to operate primarily through sustainability performance improvements (full mediation) with no direct investment appeal, while green accounting demonstrates both direct and performance-mediated effects (partial mediation). These patterns suggest that investors may differentiate between transparency-oriented initiatives and internal management capabilities when evaluating environmental practices.

This study makes several theoretical contributions to the literature. First, it extends legitimacy and stakeholder theories by showing that environmental disclosure does not independently enhance investment attractiveness in the absence of observable performance outcomes, thereby qualifying rather than overturning assumptions about the value of transparency. Second, it provides empirical support for the resource-based view in the context of green accounting systems, which demonstrates a direct association with investment attractiveness beyond its sustainability impacts. Third, it provides empirical evidence from an emerging market context with moderate explanatory power, confirming that environmental practices represent important, but not dominant, factors in investment decisions.

Practically, this study offers measured and differentiated guidance for managers navigating sustainability transitions. The results suggest that greater strategic emphasis on green accounting capabilities may yield stronger investment-related outcomes than expanding disclosure programs alone, given the former’s stronger total effect. Firms should focus on translating environmental commitments into measurable outcomes, as the mediation analysis indicates that disclosure without performance improvement is unlikely to enhance investment attractiveness. The relatively low mean scores across environmental practices indicate that Saudi firms have considerable scope to strengthen their sustainability capabilities.

For policymakers, this research provides nuanced implications regarding current approaches. While the significant relationships between environmental practices and sustainable economic outcomes support the relevance of environmental regulation, the non-significant moderating effect of Vision 2030 alignment suggests that broad strategic frameworks alone may be insufficient to influence firm-level investment outcomes. The development of standardized green accounting frameworks may therefore warrant greater policy attention than additional disclosure mandates, given the dual value-creation pathways associated with green accounting. More targeted, sector-specific instruments with clear metrics and implementation mechanisms may be more effective than aspirational alignment with national strategies.

As Saudi Arabia pursues its Vision 2030 transformation, the distinction between environmental disclosure and green accounting becomes increasingly relevant. Our results suggest that companies that develop environmental accounting capabilities may be positioned more favorably than those that focus primarily on disclosure. At the same time, the moderate explanatory power of the model underscores that environmental practices operate alongside a broader set of strategic, financial, and institutional factors in shaping investment attractiveness. The journey toward sustainability therefore requires not only transparency but also management tools to measure, integrate, and improve environmental performance, with green accounting emerging as a potentially more influential driver of investment appeal. Future progress is likely to depend less on symbolic alignment with national strategies and more on gradual, substantive capability development that generates measurable sustainability and economic outcomes.