Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Source Region of the Chishui River

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Determination of Indices of Landscape Patterns Indices

2.3.2. Land-Use Transfer Matrix

2.3.3. Land Use Dynamics

2.3.4. GeoDetector Model

2.3.5. PLUS Model

3. Results

3.1. Landscape Pattern Indices

3.2. Land Use Change

3.3. Driving Factors

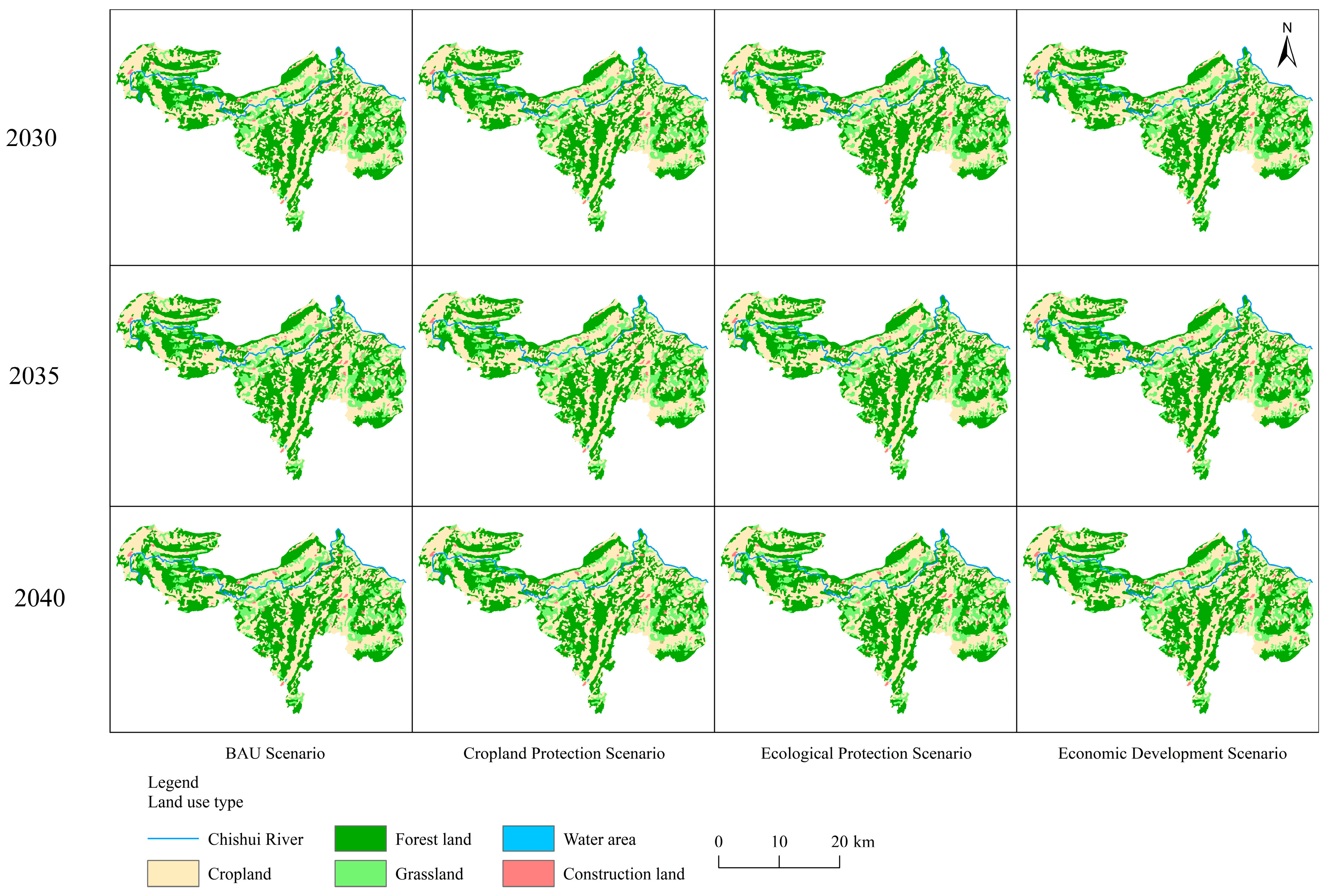

3.4. Future Multi-Scenario Prediction of Landscape Patterns

4. Discussion

4.1. Landscape Pattern Evolution

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dong, X.; Stokes, M.F.; Hendry, A.P.; Larsen, L.G.; Dolby, G.A. Geo-evolutionary feedbacks: Integrating rapid evolution and landscape change. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2024, 39, 863–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Deng, S.; Wu, D.; Liu, W.; Bai, Z. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution of land use landscape pattern in a county area based on CA-Markov model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 80, 103760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, J.S.; Whipple, K.X.; Heimsath, A.M. Isolating climatic, tectonic, and lithologic controls on mountain landscape evolution. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eadd8915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlstrom, L.; Klema, N.; Grant, G.E.; Finn, C.; Sullivan, P.L.; Cooley, S.; Simpson, A.; Fasth, B.; Cashman, K.; Ferrier, K.; et al. State shifts in the deep Critical Zone drive landscape evolution in volcanic terrains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2415155122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwang, J.S.; Thaler, E.A.; Quirk, B.J.; Quarrier, C.L.; Larsen, I.J. A Landscape Evolution Modeling Approach for Predicting Three-Dimensional Soil Organic Carbon Redistribution in Agricultural Landscapes. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 2022, 127, e2021JG006616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Zhao, F.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L. Indirect non-linear effects of landscape patterns on vegetation growth in Kunming City. npj Urban Sustain. 2024, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, X.; Li, X.; Wang, K.; Dang, D.; Gong, J.; Wang, H.; Lou, A. Optimizing landscape patterns to maximize ecological-production benefits of water-food relationship: Evidence from the West Liaohe River basin, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2023, 34, 3388–3405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Qiao, J.; Li, M.; Dun, Y.; Zhu, X.; Ji, X. Spatiotemporal evolution of ecological environmental quality and its dynamic relationships with landscape pattern in the Zhengzhou Metropolitan Area: A perspective based on nonlinear effects and spatiotemporal heterogeneity. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 480, 144102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, F.Q.; Dong, L.; Zhang, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamic Analysis and Simulation Prediction of Land Use and Landscape Patterns from the Perspective of Sustainable Development in Tourist Cities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 14450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, B.; Wei, C.; Liu, X.; Meng, Y.; Li, X. Assessing Forest Landscape Stability Through Automatic Identification of Landscape Pattern Evolution in Shanxi Province of China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beroho, M.; Briak, H.; Cherif, E.K.; Boulahfa, I.; Ouallali, A.; Mrabet, R.; Kebede, F.; Bernardino, A.; Aboumaria, K. Future Scenarios of Land Use/Land Cover (LULC) Based on a CA-Markov Simulation Model: Case of a Mediterranean Watershed in Morocco. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.H.; Huang, L.C.; Yang, L.X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.K. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Land-Use Landscape Patterns Under Park City Construction: A GIS-Based Case Study of Shenyang’s Main Urban Area (2000–2020). Sustainability 2025, 17, 7360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zhou, P.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Spatio-temporal evolution analysis of land use change and landscape ecological risks in rapidly urbanizing areas based on Multi-Situation simulation—A case study of Chengdu Plain. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 166, 112245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Q.; Zhuang, M.; Xiao, H.; Wu, H.; Ouyang, L.; Liu, Y.; Meng, C.; Song, C.; et al. Spatiotemporal Evolution of Urban Agglomeration and Its Impact on Landscape Patterns in the Pearl River Delta, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.P.; Jiao, R.; Dupont-Nivet, G.; Shen, X. Southeastern Tibetan Plateau Growth Revealed by Inverse Analysis of Landscape Evolution Model. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2022, 49, e2021GL097623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhong, X.; Deng, S.; Nie, S. Impact of LUCC on landscape pattern in the Yangtze River Basin during 2001–2019. Ecol. Inform. 2022, 69, 101631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xu, Q.L.; Yi, J.H.; Huang, X. Analysis of the heterogeneity of urban expansion landscape patterns and driving factors based on a combined Multi-Order Adjacency Index and Geodetector model. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 136, 108655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.T.; Fang, Y.; Zhao, H.Y.; Xu, X.M. Spatiotemporal evolution and driving forces of landscape structure and habitat quality in river corridors with ceased flow: A case study of the Yongding River corridor in Beijing, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 374, 123861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curry, M.E.; van der Beek, P. Exploring Controls on Post-Orogenic Topographic Stasis of the Pyrenees Mountains with Inverse Landscape Evolution Modeling. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2025, 130, e2024JF007759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Cao, W.D.; Cao, Y.H.; Wang, X.W.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Ma, J.J. Multi-scenario land use prediction and layout optimization in Nanjing Metropolitan Area based on the PLUS model. J. Geogr. Sci. 2024, 34, 1415–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagliyan, A.; Dagli, D. Monitoring Land Use Land Cover Changes and Modelling of Urban Growth Using a Future Land Use Simulation Model (FLUS) in Diyarbakir, Turkey. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.Z.; Zuo, Q.T.; Du, H.H. Simulating the impact of land use change on ecosystem services in agricultural production areas with multiple scenarios considering ecosystem service richness. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 136485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yu, H.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal evolution of urban landscapes in Chinese historic water towns (1918–2021). Landsc. Res. 2024, 49, 568–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, S.; Wang, Z.; Gao, H.; Feng, S.; Wei, B.; Hou, Z.; Xiao, F.; Jing, L.; Liao, X. The Impact of Land Use and Landscape Pattern on Ecosystem Services in the Dongting Lake Region, China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Geng, H.; Luo, G.; Wu, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, Q. Multiscale characteristics of ecosystem service value trade-offs/synergies and their response to landscape pattern evolution in a typical karst basin in southern China. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 81, 102584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, X.; Xiong, K.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z. Spatiotemporal evolution of landscape stability in World Heritage Karst Sites: A case study of Shibing Karst and Libo-Huanjiang Karst. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.X.; Wu, Z.X. Effects of liquor production wastewater discharge on water quality and health risks in the Chishui River Basin, Southwest China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ran, M.L.; Wang, Z.Y.; Li, M.; Wang, X.D.; Zhang, C.H.; Song, Z.B. Baseline biomonitoring of microplastic pollution in freshwater fish from the Chishui River, China: Insights into accumulation patterns and influencing factors. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 139055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi, S.Y.; Gong, Y.T.; Wang, H.J.; Zheng, J.X.; Hu, J.; Hu, J.X.; Dong, F.Y. A pilot macroinvertebrate-based multimetric index (MMI-CS) for assessing the ecological status of the Chishui River basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2017, 83, 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Feng, C.; Song, T.; Ji, W.; Yang, J.; Li, F. Study on the characteristics of land use change in Chishui River Basin from 1990 to 2018. J. Environ. Eng. Technol. 2021, 11, 428–436. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Wang, Z. Multi-scenario simulation and evaluation of the impacts of land use change on ecosystem service values in the Chishui River Basin of Guizhou Province, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 163, 112078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, G.; Weici, S.; Wenzhuo, D.; Liang, H. Topographic gradient analysis and application of machine learning models for trade-offs and synergies of ecosystem services in the Chishui River Basin. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 9980–9996. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.B.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Guan, T.Z.; Qin, C.X.; Chen, D.N.; Jia, H.F.; Zhang, X.Z.; Yu, Y.H. A novel method for hydrology and water quality simulation in karst regions using machine learning model. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 178, 113862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.Q.; Jia, Y.Y.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y.R. Overview of karst geo-environments and karst water resources in north and south China. Environ. Earth Sci. 2011, 64, 1865–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, R.; Yan, C.; Wu, S. China Multi-period Land Use Remote Sensing Monitoring Dataset. Resour. Environ. Sci. Data Platf. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhenxiong County People’s Government. Overview of Ecological and Environmental Protection Work During the 13th Five-Year Plan Period (5 Years) and 2020, Major Goals and Tasks for the 14th Five-Year Plan Period, and Key Work for 2021 in the City. 2021. Available online: http://www.zx.gov.cn/searchDetail.html?channelId=5538&id=19436 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Zhenxiong County People’s Government. Zhenxiong County Coordinates and Promotes the Work of Cultivated Land Protection. 2023. Available online: http://www.zx.gov.cn/searchDetail.html?channelId=5498&id=25446 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Zhenxiong County People’s Government. Public Notice Form of the 2024 County-Level Inspection and Acceptance Results for the 2020 Grain for Green Program in Zhenxiong County. 2024. Available online: http://www.zx.gov.cn/searchDetail.html?channelId=5501&id=32033 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Zhenxiong County People’s Government. Yang Xuchun Conducts an Investigation and Research Tour in Chishuiyuan Town. 2024. Available online: http://www.zx.gov.cn/searchDetail.html?channelId=5498&id=31974 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Zhenxiong County People’s Government. Draft for Public Comment on the Interim Measures for the Administration of Rural Homesteads in Zhenxiong County. 2024. Available online: http://www.zx.gov.cn/searchDetail.html?channelId=5468&id=31023 (accessed on 24 October 2025).

- Fox, M.; Clinger, A.; Smith, A.G.G.; Cuffey, K.; Shuster, D.; Herman, F. Antarctic Peninsula glaciation patterns set by landscape evolution and dynamic topography. Nat. Geosci. 2024, 17, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Z.; Jinrui, L.; Zongzhu, C.; Yiqing, C.; Peng, Z. Spatio-temporal Evolution Characteristics and Influencing Factors of Landscape Ecological Risks in the Three Major Basins of Hainan Island, China. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2025, 45, 1646–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Yijun, W.; Chao, S.; Shuwei, W.; Jinlong, Z.; Xiaofang, M. Landscape pattern evolution and its driving forces in the Shiyang River Basin from 1986 to 2020. Pratacultural Sci. 2023, 40, 303–317. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Y.; Ma, C.H.; Ma, L.Y.; Li, N. Ecological effects of land use and land cover change in the typical ecological functional zones of Egypt. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 168, 112747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Chen, X.W.; Yao, H.X.; Lin, F.Y. SWAT model-based quantification of the impact of land-use change on forest-regulated water flow. Catena 2022, 211, 105975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jinfeng, W.; Chengdong, X. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, L.L.; Wu, Z.W.; Li, S.; Xie, G. The relative impacts of vegetation, topography and weather on landscape patterns of burn severity in subtropical forests of southern China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, F. Spatial-temporal evolution and driving forces of landscape ecological risk in the Chishui River Basin (Guizhou section). Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2025, 33, 550–562. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, B.; Goswami, K.P. Evaluating the influence of biophysical factors in explaining spatial heterogeneity of LST: Insights from Brahmani-Dwarka interfluve leveraging Geodetector, GWR, and MGWR models. Phys. Chem. Earth 2025, 138, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.M.; Tan, S.K.; Chen, E.Q.; Li, J.X. Spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of land disputes in China: Do socio-economic factors matter? Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.P.; Xiong, N.N.; Liang, B.Y.; Wang, Z.; Cressey, E.L. Spatial and Temporal Variation, Simulation and Prediction of Land Use in Ecological Conservation Area of Western Beijing. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tongli, N.; Lihua, X.; Jie, C.; Yanlai, Z.; Jiabo, Y.; Dedi, L. Land use simulation and multi-scenario prediction of the Yangtze River Basin based on PLUS model. Eng. J. Wuhan Univ. 2024, 57, 129–141. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Xiang, S.Y.; Chen, X.T.; Yi, X.M.; Huang, X.T.; Huang, T. Multi-Scenario Simulation of Land Use Change in Chengyu Economic Zone and Its Influence on Carbon Reserves. Environ. Sci. 2025, 46, 5718–5728. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, L.A.; Tao, F.; Liu, R.R.; Wang, Z.L.; Leng, H.J.; Zhou, T. Multi-scenario simulation and ecological risk analysis of land use based on the PLUS model: A case study of Nanjing. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 85, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wang, K.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, X. Effects of human disturbance on the landscape pattern in the mountainous area of western Henan, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 380, 124959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wu, Q.; Qiao, J. Underlying the influencing factors behind the heterogeneous change of urban landscape patterns since 1990: A multiple dimension analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 140, 108967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, L.; Yan, J.; Li, Y.; Gong, Z. Spatial-temporal evolution and correlation analysis between habitat quality and landscape patterns based on land use change in Shaanxi Province, China. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 13, e10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberti, M.; Wang, T. Detecting patterns of vertebrate biodiversity across the multidimensional urban landscape. Ecol. Lett. 2022, 25, 1027–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Yuan, X.; Ni, G.; Liu, Y.; Qi, Y.; Miao, S. Utilizing deep transfer learning to discover changes in landscape patterns in urban wetland parks based on multispectral remote sensing. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 83, 102808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Spatial Resolution | Year | Data Source | Website |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land use | 30 m | 2000–2020 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS | https://www.resdc.cn |

| Elevation | 30 m | 2020 | Geospatial Data Cloud | https://www.gscloud.cn |

| Slope | - | 2020 | DEM | - |

| Precipitation | 30 m | 2000–2020 | Data Center of the Institute of Mountain Hazards and Environment, CAS | https://imde.cas.cn |

| Population | 1 km | 2000–2020 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS | https://www.resdc.cn |

| GDP | 1 km | 2000–2020 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS | https://www.resdc.cn |

| Soil type | 1 km | 1995 | Resource and Environmental Science Data Platform, Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS | https://www.resdc.cn |

| Road data | - | 2020 | OpenStreetMap | https://openmaptiles.org |

| River Data | - | 2020 | OpenStreetMap | https://openmaptiles.org |

| Settlement | 25 m | 2000 | National Center for Fundamental Geographic Information | https://www.webmap.cn |

| Seats of township governments | 25 m | 2000 | National Center for Fundamental Geographic Information | https://www.webmap.cn |

| Field survey data | - | - | Questionnaire surveys and interviews | - |

| Year | NP | PD | LSI | CONTAG | DIVISION | SHDI | SHEI | AI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 273 | 0.4323 | 19.6035 | 57.7353 | 0.9286 | 0.9798 | 0.7068 | 95.821 |

| 2020 | 366 | 0.5795 | 21.1495 | 60.6155 | 0.9401 | 1.0552 | 0.6557 | 95.4641 |

| Land Types | PD | LSI | PAFRAC | IJI | AI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 2020 | 2000 | 2020 | 2000 | 2020 | 2000 | 2020 | 2000 | 2020 | |

| Cropland | 0.171 | 0.190 | 23.197 | 24.623 | 1.318 | 1.342 | 52.273 | 56.461 | 95.998 | 95.671 |

| Grassland | 0.157 | 0.168 | 18.273 | 19.193 | 1.265 | 1.308 | 60.897 | 57.670 | 94.051 | 93.975 |

| Forest land | 0.103 | 0.108 | 22.392 | 23.141 | 1.360 | 1.359 | 42.628 | 43.290 | 96.132 | 95.954 |

| Water area | 0.002 | 0.002 | 1.391 | 1.391 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 96.035 | 96.170 |

| Construction land | 0.112 | 12.637 | 1.329 | 63.734 | 88.282 | |||||

| Year | Proportion of Land Use Types/% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cropland | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Area | Construction Land | |

| 2000 | 44.05 | 43.84 | 12.09 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 2005 | 44.06 | 43.81 | 12.11 | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| 2010 | 42.64 | 42.85 | 13.11 | 0.02 | 1.37 |

| 2015 | 42.60 | 42.87 | 13.08 | 0.02 | 1.43 |

| 2020 | 42.63 | 42.88 | 13.05 | 0.02 | 1.43 |

| Year | Cropland | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Area | Construction Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2005 | 0.08 | 0.56 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2005–2010 | −9.69 | −6.79 | 6.14 | 0.00 | 8.68 |

| 2010–2015 | −0.26 | 0.08 | −0.19 | 0.01 | 0.35 |

| 2015–2020 | 0.17 | 0.07 | −0.22 | −0.01 | −0.02 |

| 2000–2020 | −8.99 | −6.07 | 6.02 | 0.00 | 9.01 |

| Year | Cropland | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Area | Construction Land |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000–2005 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 2005–2010 | −0.69 | −0.49 | 1.60 | 0.00 | 173.59 |

| 2010–2015 | −0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 1.8 | 0.81 |

| 2015–2020 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.05 | −1.7 | −0.05 |

| 2000–2020 | −0.65 | −0.44 | 1.58 | 0.00 | 180.14 |

| Multi-Scenario Prediction of Land Use Area Changes/km2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Cropland | Forest Land | Grassland | Water Area | Construction Land | Scenario | |

| Year | |||||||

| 2020–2030 | −1.65 | −0.11 | 0.83 | 0.00 | 0.02 | Natural development | |

| 2030–2035 | −0.44 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.09 | ||

| 2035–2040 | −0.45 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.00 | 0.15 | ||

| 2020–2040 | −2.54 | 0.19 | 1.18 | 0.00 | 0.26 | ||

| 2020–2030 | 5.84 | −5.88 | −0.88 | 0.00 | 0.01 | Cropland protection | |

| 2030–2035 | 0.56 | −0.30 | −0.27 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 2035–2040 | 0.61 | −0.34 | −0.30 | 0.00 | 0.02 | ||

| 2020–2040 | 7.01 | −6.52 | −1.45 | 0.00 | 0.04 | ||

| 2020–2030 | −2.27 | 0.36 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | Ecological protection | |

| 2030–2035 | −0.36 | 0.16 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.01 | ||

| 2035–2040 | −0.45 | 0.14 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.15 | ||

| 2020–2040 | −3.08 | 0.66 | 1.35 | 0.01 | 0.16 | ||

| 2020–2030 | −2.39 | −0.22 | 0.72 | −0.01 | 0.99 | Economic development | |

| 2030–2035 | −0.62 | −0.10 | −0.09 | 0.00 | 0.81 | ||

| 2035–2040 | −0.29 | −0.22 | −0.20 | 0.00 | 0.72 | ||

| 2020–2040 | −3.30 | −0.54 | 0.43 | −0.01 | 2.52 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gong, Y.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Zhao, J.; Fu, D.; Luo, G. Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Source Region of the Chishui River. Sustainability 2026, 18, 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020914

Gong Y, Huang X, Li J, Zhao J, Fu D, Luo G. Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Source Region of the Chishui River. Sustainability. 2026; 18(2):914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020914

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Yanzhao, Xiaotao Huang, Jiaojiao Li, Ju Zhao, Dianji Fu, and Geping Luo. 2026. "Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Source Region of the Chishui River" Sustainability 18, no. 2: 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020914

APA StyleGong, Y., Huang, X., Li, J., Zhao, J., Fu, D., & Luo, G. (2026). Landscape Pattern Evolution in the Source Region of the Chishui River. Sustainability, 18(2), 914. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18020914