1. Introduction

Landslide dams are a type of natural dam that form under specific geological and geomorphological conditions, typically associated with steep and unstable valley slopes, high topographic relief, and slope materials composed of weak, weathered, or highly fractured rock and soil. They occur when large volumes of earth and rock—produced by landslides, rockfalls, or debris flows triggered by earthquakes, intense rainfall, or volcanic eruptions—accumulate and obstruct mountain valleys or river channels [

1,

2,

3]. This obstruction leads to the formation of upstream impoundments known as barrier lakes, which often store substantial volumes of water behind loosely compacted and structurally weak dam bodies. As a result, such lakes are highly susceptible to sudden failure shortly after formation, potentially generating catastrophic downstream flooding and severe impacts on public safety and infrastructure [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. The severity of this threat is underscored by the fact that the majority of landslide dams eventually fail [

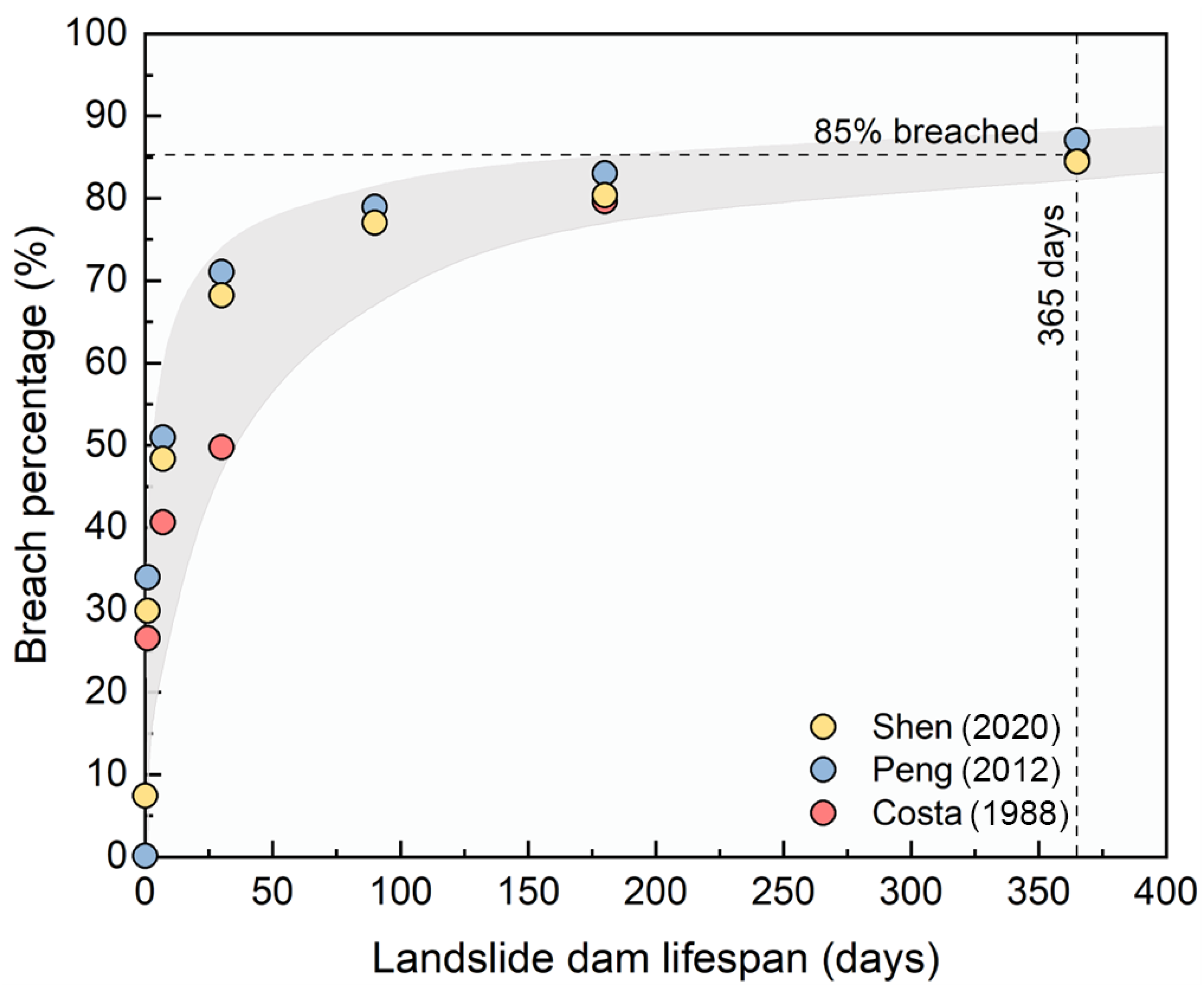

3,

9,

10], as illustrated in

Figure 1. The high failure rate is closely related to the intrinsic structural weaknesses of landslide dams. These dams often contain distinct voids and natural slip surfaces within their bodies, making them loosely consolidated and poorly cemented. As a result, they are highly susceptible to external triggers. Previous studies have shown that under the influence of aftershocks, intense rainfall, and rising upstream water levels, localized instability and concentrated seepage may develop within landslide dams, thereby significantly increasing the likelihood of dam breaching [

11,

12,

13]. Landslide dam breaches pose a dual threat to hydrological safety and downstream socio-environmental stability [

14,

15].

Due to the serious damage that landslide dam failures can cause, it is very important to develop mathematical models to simulate the breaching process [

16,

17]. These models offer a useful way to analyze and predict how a dam might fail, which helps in making emergency response plans and reducing damage downstream. Predicting the potential failure of landslide dams has long been prioritized in disaster risk management and mitigation strategies. In particular, numerous models have been developed to simulate overtopping, which is the primary failure mechanism of landslide dams, accounting for approximately 94% of all documented dam breaches [

11]. These models have significantly enhanced our comprehension of the temporal evolution of the breach process. However, they typically rely on simplified assumptions regarding dam material properties, internal erosion processes, or breach geometry, which may limit their applicability to complex natural dams.

At present, dam breach models for earth-rock dams are typically categorized into three primary classes. The first type consists of empirical models, which are derived from historical dam failure data and use statistical relationships to estimate key breach parameters [

18,

19,

20]. Due to their simplicity and computational efficiency, these models are widely used for rapid assessments of potential dam breach consequences. The second type is simplified mechanistic models. These models are based on certain assumptions, such as keeping the breach shape fixed during the failure. They simulate the breach process by comparing the flow’s shear stress with the critical shear stress of dam materials, or by using erosion formulas. Usually, the breach growth and the resulting outflow are calculated in separate steps. These models are the most used tools for simulating earth-rock dam failures [

21,

22,

23]. The third type is refined mechanistic models. These models are more detailed and are based on mathematical equations that explicitly describe the physical processes of water flow and soil erosion. Depending on the level of complexity, they can be one-dimensional, two-dimensional (depth-averaged), or fully three-dimensional, representing the spatial variation in flow and erosion processes. Such advanced models provide a more realistic description of breach formation and development in earth-rock dams [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Previous research has built a strong foundation for understanding the failure mechanisms of landslide dams. Statistical analyses indicate that overtopping is the dominant failure mode, accounting for approximately 94% of reported cases, while seepage erosion contributes about 5%. Together, these two mechanisms are responsible for nearly 99% of landslide dam failures [

11,

13,

14,

28]. Building on this understanding, numerous numerical studies have been developed to simulate dam-breaching processes.

Extensive research has significantly advanced our comprehension of dam breach mechanisms [

29,

30,

31,

32] and the associated simulation methodologies [

7,

33,

34,

35]. However, existing physically based models generally focus on single-inducing factors—either pure overtopping [

34,

36,

37] or pure seepage/piping [

32,

38,

39]. Consequently, these models often struggle to accurately represent the complex scenarios where both mechanisms occur simultaneously or transition from one to the other. In reality, under extreme weather or geological conditions, landslide dam failures often result from the combined action of both factors, making the breach process highly complex [

40,

41,

42]. Although this combined failure is common and important, to the best of our knowledge, mathematical models specifically designed to simulate the breach process under the simultaneous coupled action of overtopping and seepage remain limited in the literature. Consequently, the limitations of current models necessitate additional research efforts in this domain.

This paper presents a unified numerical framework designed to simulate the combined effects of surface scouring and internal piping within landslide dams. Unlike previous works that treat these mechanisms in isolation, the primary innovation of this study lies in the establishment of a unified, time-stepped, dual-mechanism erosion framework with coupled breach geometry updates. This approach allows for the continuous simulation of the interaction between overtopping flow and seepage channels, providing a more comprehensive tool for hazard assessment under multi-hazard conditions.

To demonstrate the applicability of the proposed methodology, the model is applied to representative landslide dam breach cases using both field observations and experimental data. The paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 details the development of the mathematical model considering the combined effects;

Section 3 presents the numerical solution procedure;

Section 4 validates the model’s accuracy and applicability using field data and experimental cases; and finally,

Section 5 discusses limitations and potential directions for future research.

2. Model Development

Landslide dam failure represents an intricate dynamic phenomenon characterized by the strong coupling between hydraulic forces and sediment transport [

43,

44,

45]. The synergistic interaction between seepage and overtopping significantly exacerbates the failure process through complex non-linear coupling. Specifically, seepage forces reduce the effective stress and soil stability, thereby accelerating the erosion rate caused by overtopping flow. Studies [

42] have shown that before combined erosion begins, initial penetrating seepage channels often form inside the dam. However, since the seepage discharge is usually limited, the reservoir water level continues to rise provided that the inflow exceeds the seepage outflow. Once the impounded water level surpasses the minimum elevation of the dam crest, overtopping occurs. The overtopping flow scours the dam body, leading to the simultaneous vertical incision and lateral widening of the breach channel. At the same time, some reservoir water seeps through internal channels toward the downstream side, carrying fine soil particles along the way. This particle movement leads to the gradual enlargement of the seepage channels.

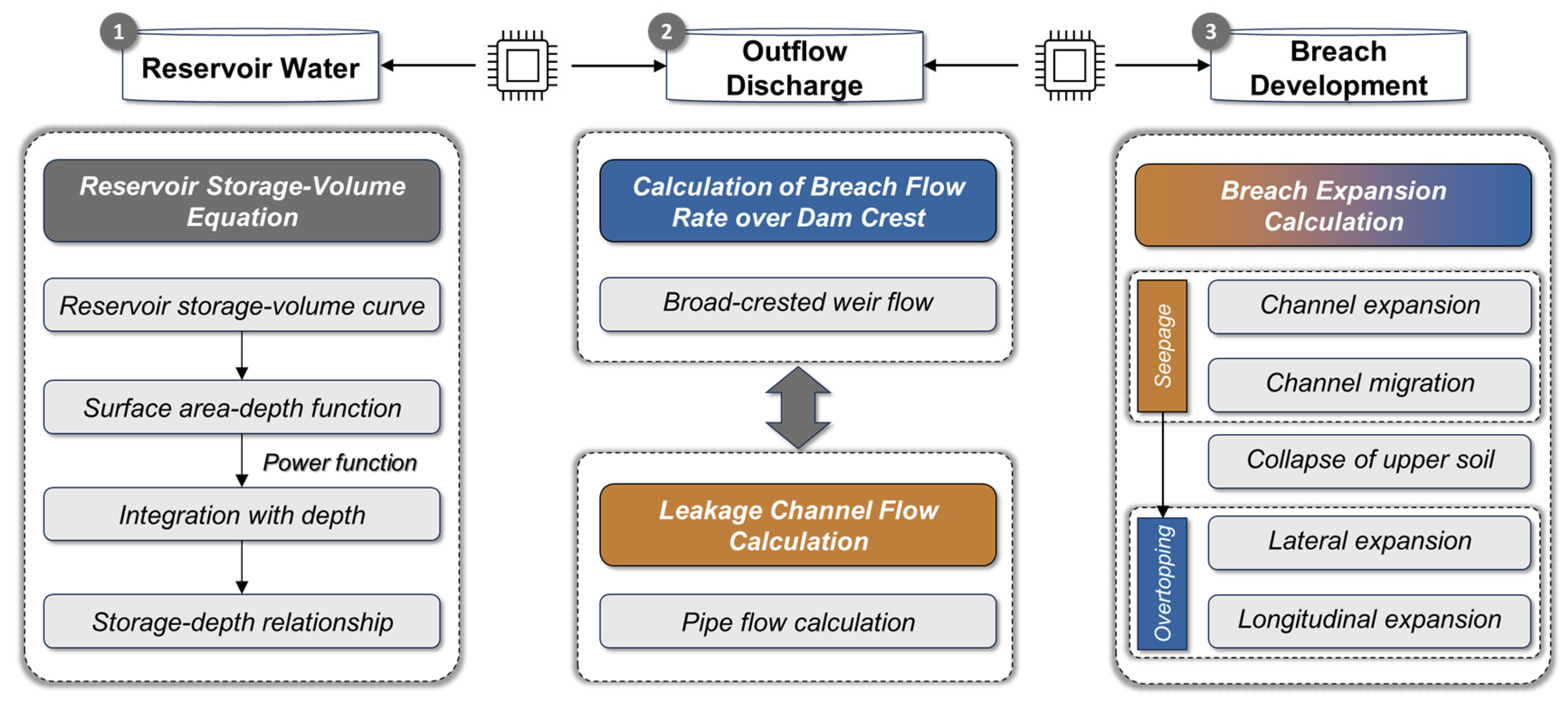

The combined action of channel widening and breach incision undermines the stability of the overburden material. This weakening is governed by the reduction in effective stress due to increased pore water pressure, which leads to a functional decrease in soil shear strength (dependent on cohesion and the angle of internal friction). The extent of this effect depends on the spatial relationship between the breach and the seepage channels. If the soil above a seepage channel collapses due to stress imbalance, the failure mode may shift from a combined seepage-overtopping mechanism to one dominated by overtopping alone. Specifically, this collapse is triggered when the gravitational and seepage forces exceed the resisting shear strength of the soil arch (i.e., when the factor of safety drops below a critical threshold). This mechanism elucidates that breaching is a complex dynamic process driven by the interaction of surface flow, seepage, sediment transport, and slope instability, phenomena that are fully integrated into the proposed modeling approach. Based on this, this study establishes a comprehensive multi-module coupled numerical framework designed to simulate the dam failure process. The core framework consists of three main computational modules, as illustrated in

Figure 2.

2.1. Module 1—Reservoir Water

The upstream reservoir stage constitutes a dynamic state variable that evolves continuously during the dam breaching operation. This variable is driven by the dynamic interplay between the upstream riverine influx and the discharge released via both surface breaching and internal piping pathways. Calculating the rate of change in the upstream water level requires a rigorous accounting of both the riverine inflow and the total outflow discharge through the landslide dam section. The entire process follows the mass conservation equation:

In the equation, V represents the volume of the upstream reservoir, t is time, As denotes the surface area of the reservoir, zs denotes the reservoir water elevation, Qin denotes the inflow from the upstream river, and Qout denotes the outflow through the breach.

Complementing the inflow and outflow dynamics, the variation in reservoir water level is significantly constrained by the upstream basin geometry, specifically defined by the elevation-surface area relationship curve. This relationship is typically represented by the surface area and the water depth of the reservoir. In field-measured case studies, the relationship between the reservoir volume and surface area is often available. Therefore, a conversion is needed here. It is common practice to approximate the relationship between the reservoir surface area and water depth using a power-law function [

46,

47,

48,

49], as follows:

In the equation,

H denotes the water depth, and

αr and

mr are empirical coefficients. By integrating the above expression with respect to the water depth

H, the volume-depth relationship of the reservoir can be obtained as:

Substituting Equation (2) into Equation (3) yields:

With the known values of reservoir water depth, surface area, and storage volume, the coefficient mr can be derived using the aforementioned equation. Once mr is known, it can be substituted into Equation (2) or Equation (3) to solve for the other coefficient αr in Equation (2). This step-wise approach ensures internal consistency among the empirical parameters used in the reservoir geometry modeling.

2.2. Module 2—Outflow Discharge

The outflow hydrograph plays a paramount role in defining the kinetics of the dam breaching process. Subjected to the combined action of seepage and overtopping, the downstream discharge through the landslide dam section consists of two components: one is the seepage flow through internal channels within the dam, and the other is the surface flow through the breach at the dam crest, expressed as:

In the equation, Qo denotes the overtopping discharge flowing across the dam crest, and Ql represents the seepage discharge through internal channels within the dam.

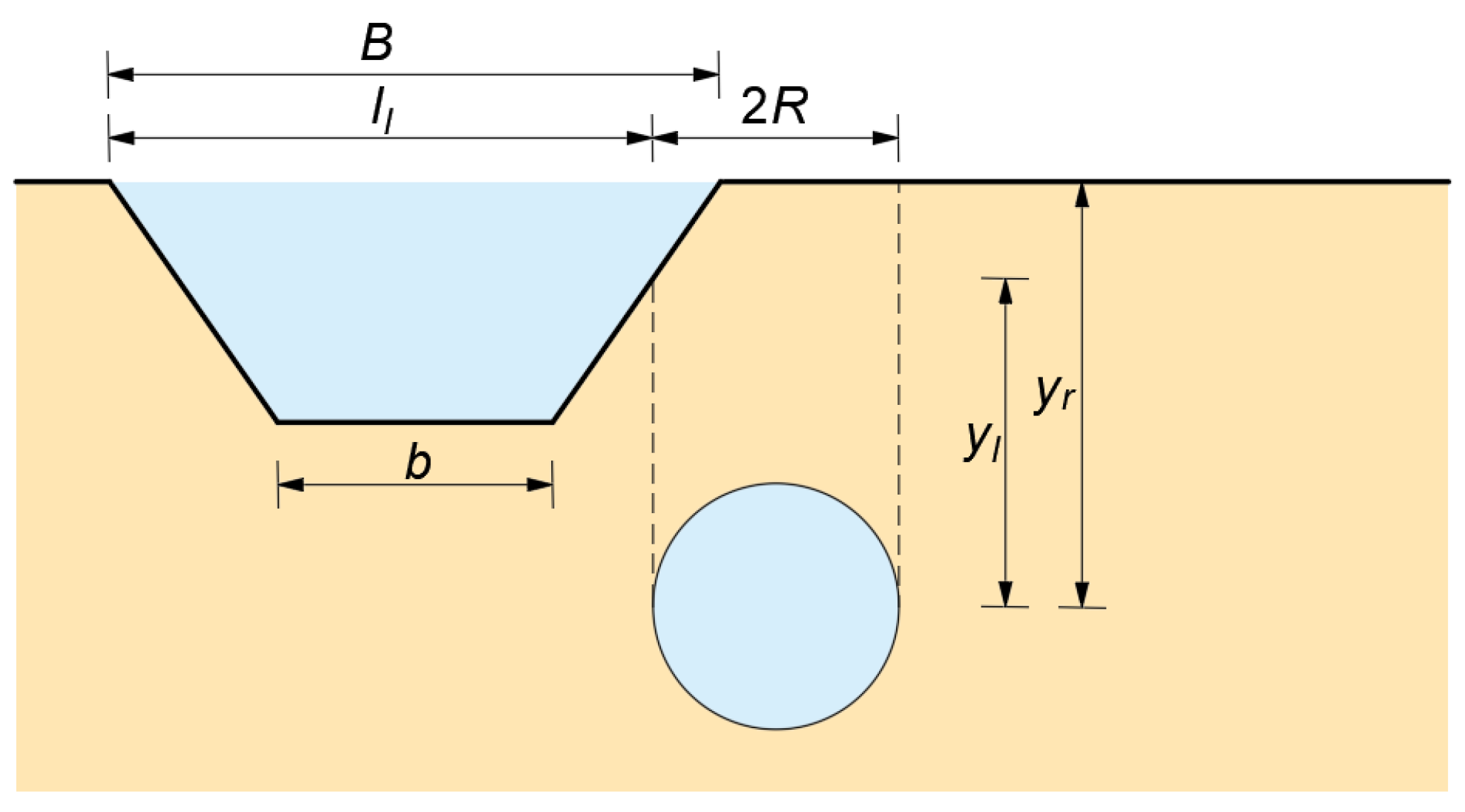

2.2.1. Discharge Through the Breach

To facilitate the computation of the overtopping discharge

Qo, the evolving breach cross-section is typically idealized as a trapezoidal or rectangular profile. As substantiated by findings from large-scale flume experiments [

42,

50,

51], the breach cross-section at the crest typically evolves into an inverted trapezoidal profile driven by continuous overtopping erosion. Therefore, this study adopts an inverted trapezoidal cross-section as the basic assumption for the initial breach geometry. Based on the broad-crested weir discharge formula [

52], a breach discharge calculation model is established as follows:

In the equation,

ks is a correction factor accounting for the effect of submerged flow downstream of the breach;

cd is the discharge coefficient;

b is the bottom width of the breach; Δ

h is the flow depth within the breach;

c1 and

c2 are the discharge coefficients corresponding to the rectangular and triangular portions of the cross-section, respectively; and

m denotes the side slope coefficient of the trapezoidal breach cross-section [

53]. The flow depth within the breach, Δ

h is determined by the following equation:

In the equation, zb denotes the elevation of the breach bed.

2.2.2. Discharge Through Internal Channels

In landslide dams, internal seepage initially develops as diffuse flow through the pore space of the dam material. However, both field observations and physical model experiments have shown that under sustained hydraulic gradients, seepage tends to progressively concentrate along preferential flow paths, forming localized seepage channels or piping structures. Once such channels are established, the flow regime transitions from distributed porous-media seepage to conduit-dominated flow, in which inertia and local energy losses become significant.

In this study, internal seepage is therefore simplified as pressurized pipe flow to represent the dominant hydraulic behavior after the formation of concentrated seepage channels. This assumption is particularly applicable to landslide dams composed of loose or heterogeneous materials, where internal erosion and particle migration promote rapid channelization. Compared with Darcy-based seepage models, the pipe-flow representation provides a more suitable physical description of high-discharge seepage and internal erosion under advanced failure stages.

It should be noted that the pipe-flow assumption is primarily intended for conditions where seepage channels are sufficiently developed and hydraulically connected to the upstream reservoir. For early-stage diffuse seepage without evident channelization, a porous-media seepage model would be more appropriate. In the present model, the transition from diffuse seepage to channelized flow is implicitly accounted for by focusing on the critical stage governing breach enlargement and failure escalation.

Before calculating the flow in the seepage channel

Ql, it is essential to determine whether the seepage water flow is under pressurized pipe flow conditions or free surface flow conditions. Since seepage channels are typically lower than the upstream water level, they can be considered submerged in the reservoir, making pipe flow a more realistic representation. To facilitate the mathematical derivation, it is assumed that the water flow fills the seepage channel before the upper wedge-shaped soil block collapses [

11,

12,

38,

54]. While early collapse may occur in reality due to local instability, this assumption allows for the calculation of discharge capacity under critical flow conditions. The volumetric flow rate within the internal seepage conduit is calculated using the expression:

In the equation, the discharge coefficient

μc is empirically set to 0.5 [

55],

A denotes the cross-sectional flow area of the seepage conduit,

g denotes the gravitational acceleration,

h denotes the hydraulic head difference between the upstream reservoir level and the outlet of the seepage conduit,

R denotes the radius of the seepage conduit.

2.3. Module 3—Breach Development

Breach development is a primary indicator of structural failure in dams. During the failure process driven by combined erosion mechanisms, breach development is characterized by the simultaneous vertical incision and lateral widening of the surface breach, alongside the continuous enlargement of the internal seepage conduit. These two types of generalized breach expansion are governed by distinct physical processes and differ significantly in their underlying mechanisms. The flow at the dam crest breach typically behaves as open-channel weir flow, where breach expansion is primarily driven by the erosion and transport of soil and rock particles from the breach sidewalls and bottom, resulting in both lateral and vertical growth [

56,

57]. In contrast, the internal flow within the dam body is characterized as pressurized pipe flow, wherein breach expansion is manifested as the progressive radial enlargement of the seepage conduit driven by internal erosion [

38,

58,

59]. Given the significant differences in these two failure mechanisms, separate computational approaches are required for their analysis.

2.3.1. Overtopping-Induced Breach Expansion

The failure of a landslide dam constitutes a highly complex hydro-mechanical coupling process. At the microscopic level, the enlargement of the breach is driven by the detachment and subsequent entrainment of soil particles by the high-velocity overtopping flow. Therefore, the erosion process of soil particles around the breach directly influences the breach expansion. As a result, a fundamental prerequisite for simulating breach evolution is to accurately quantify the sediment transport rate of the dam material under the scouring action of the overtopping flow.

According to Einstein [

60] sediment transport theory, the total sediment transport rate is defined as the summation of the bedload and suspended load transport rates. Although Einstein’s sediment transport theory was originally developed for relatively uniform sediment beds, it is adopted here as a physically based approximation for intense erosion conditions, with grading effects incorporated through a correction factor. Considering the high flow velocity and intense scour characteristics during the failure of the landslide dam, a correction factor

ζ is introduced into the total sediment transport rate, as follows:

In the equation,

gT denotes the unit-width total sediment transport rate;

γs denotes the unit weight of dam material;

γ denotes the unit weight of water;

τ0 denotes the bed shear stress;

U denotes the depth-averaged flow velocity;

eb denotes the bedload sediment transport efficiency;

α denotes the angle of friction with a value of 32.2° [

61]; and

ω denotes the sediment settling velocity. The unit-width total sediment transport rate

QT is then given by:

Once the total sediment transport rate is obtained, it needs to be distributed between the breach bottom and side slopes to determine the incremental expansion of the breach in different directions. For the case of continuous erosion, empirical observations from previous experimental studies [

62,

63] demonstrate that the vertical incision rate is approximately equivalent to the lateral expansion rate. Consequently, this study adopts this experimentally validated relationship to distribute the sediment transport rate. Additionally, the position of the dam toe is assumed to remain unchanged, implying that the downstream slope angle decreases progressively as erosion develops. A schematic representation of the breach expansion process driven by continuous erosion at the dam crest is presented in

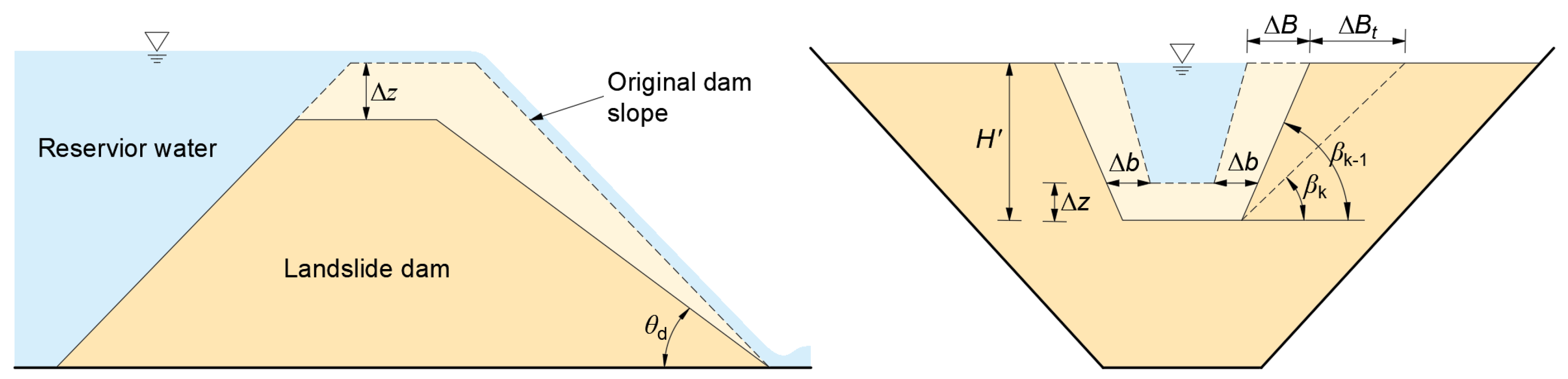

Figure 3.

Based on this evolution pattern, the incremental vertical erosion depth of the breach within a unit time can be expressed as:

In the equation, Δz denotes the incremental vertical erosion depth of the breach bed; ρs denotes the density of the dam material; Lb denotes the longitudinal dimension of the breach; and n0 denotes the porosity of the dam material.

Multiple factors dictate the lateral breach enlargement, most notably the flow hydraulics, sediment properties, and the breach side slope morphology. To enhance the computational efficiency of the model, a simplifying assumption is adopted wherein the lateral widening rate at the breach bed is considered equivalent to the vertical incision rate. Therefore, the sidewall expansion process can be represented by the vertical erosion rate, as follows:

In the equation, ΔB is the incremental increase in the breach top width, Δb is the incremental increase in the breach bottom width, and β is the breach slope angle.

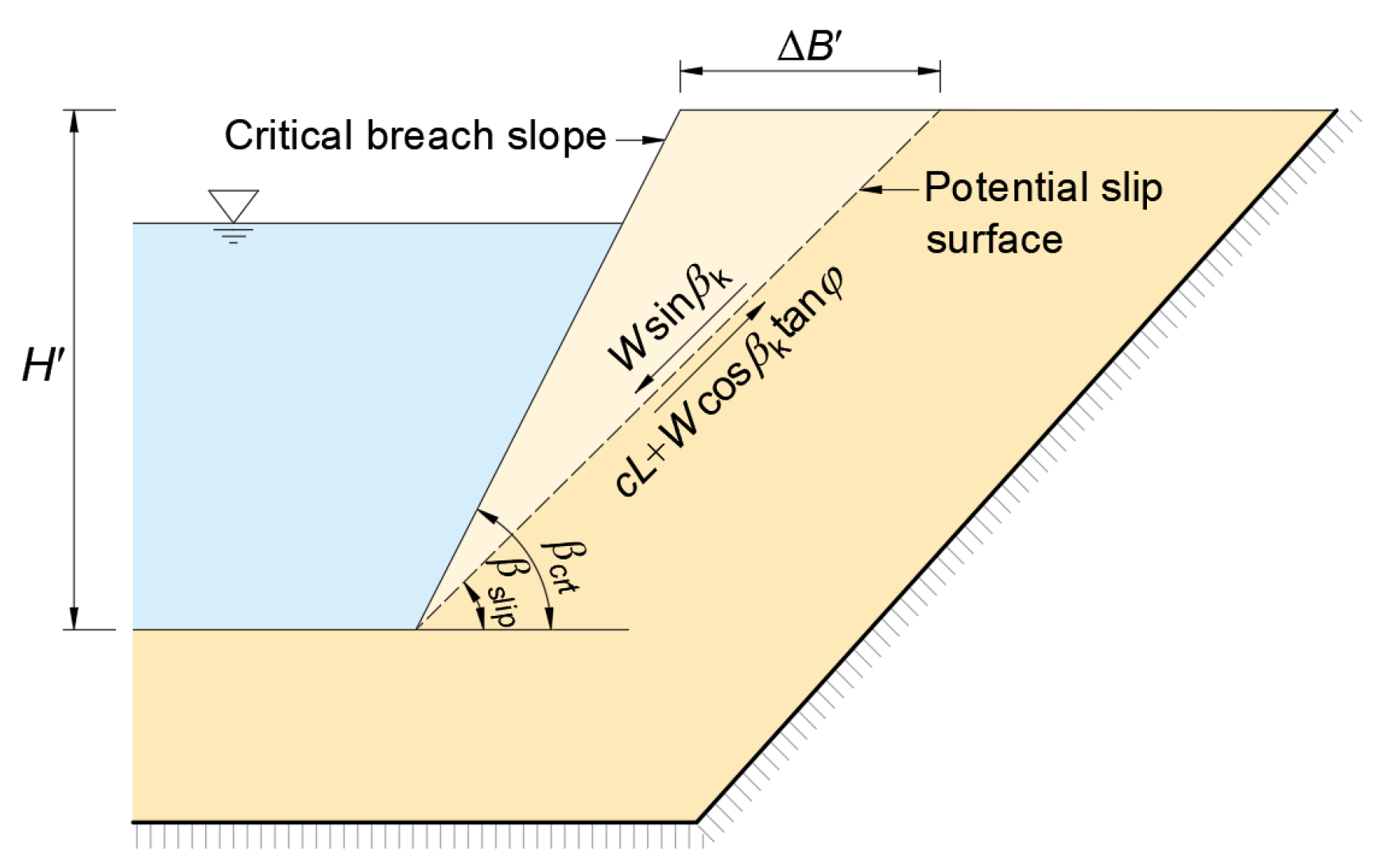

As previously assumed, the expansion rates of the breach top and bottom widths are equal within the same time step. However, as the breach depth continues to increase, the side slope angle of the breach gradually steepens. Upon the lateral slope angle attaining its critical failure value, slope instability is triggered, leading to failure of the sidewall and the formation of a new breach boundary. This process results in a sudden increase in the breach top width, as illustrated in

Figure 4.

It is assumed that the potential slip surface of the breach side slope is planar and passes through the slope toe, the slope will fail when the breach slope reaches its critical value. At this point, the stress conditions on the slip surface are defined by:

In the equation,

Ws is the weight of the sliding body,

c is the cohesion of soil mass,

L is the length of the sliding surface,

φ is the internal friction angle of soil,

βslip is the dip angle of the sliding surface. The weight of the sliding body can be expressed as:

In the equation,

βcrt is the critical dip angle of breach slope,

H’ is the breach depth. Combining Equations (13) and (14), it can be obtained:

According to Mohr–Coulomb Strength Theory, when the soil is destroyed in the limit equilibrium state, it meets

. Combined with Equation (15), the following equation can be obtained.

Whether the slope will collapse can be judged by the dip angle of the breach slope. According to Equation (16), the critical dip angle of breach slope can be expressed as:

When the breach slope collapses, the breach bed dimensions (width and depth) exhibit no incremental change according to

Figure 4, In contrast, the increment of the breach top width is computed via the following equation:

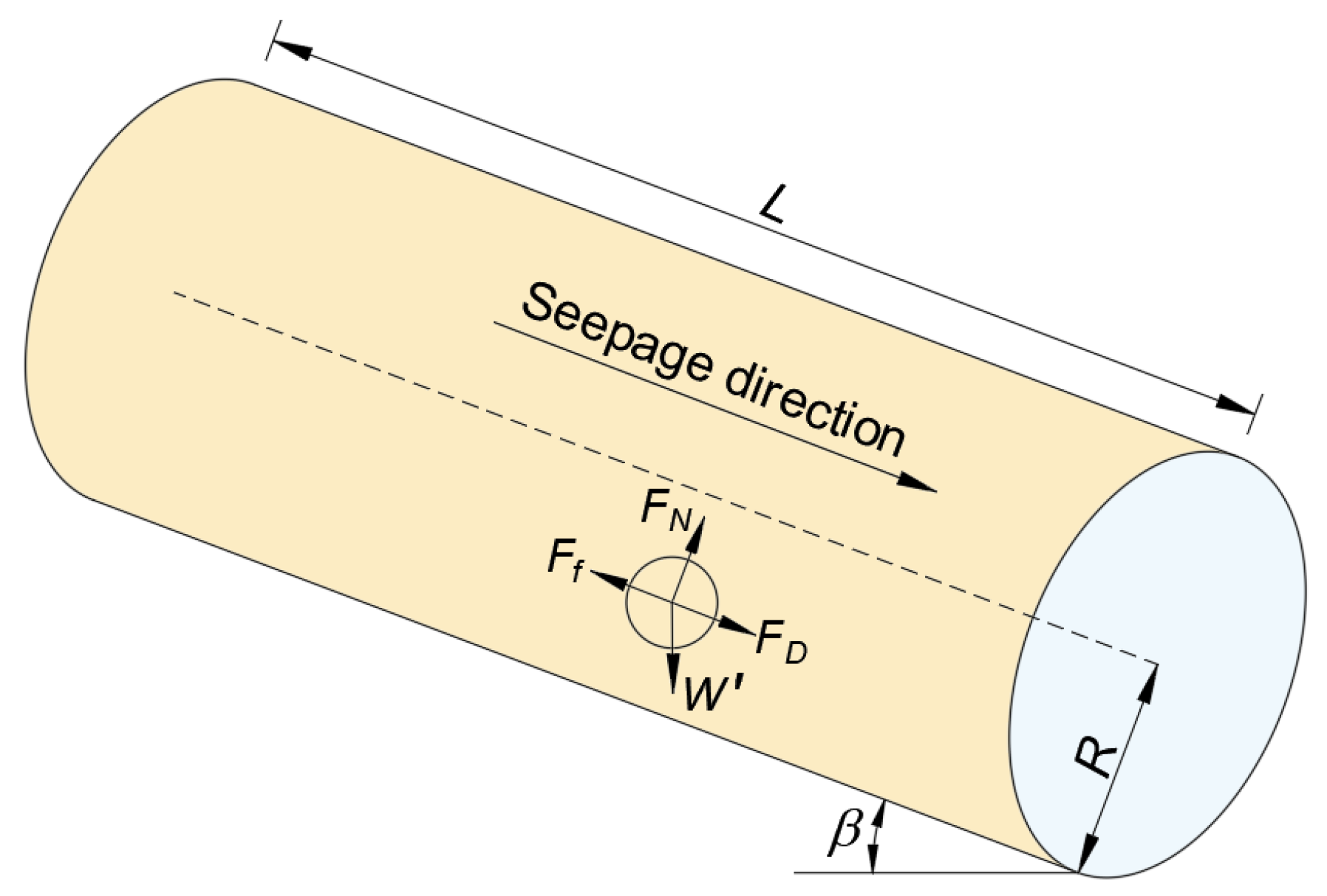

2.3.2. Seepage-Induced Channel Expansion

Figure 5 illustrates the forces exerted on the soil and rock particles within the seepage channel subjected to internal flow. Under typical hydraulic conditions, the buoyant force exerted on the sediment particles is significant and strictly non-negligible [

64]. Therefore, the gravitational force acting on the particles within the seepage channel is represented by their submerged weight. The primary forces acting on the soil particles are as follows:

In the equation,

FD denotes the hydrodynamic drag force exerted by the seepage flow on the sediment particle,

CD denotes the drag coefficient (taken as 0.7),

ρ denotes the density of water,

ν denotes the flow velocity,

d50 denotes the mean particle diameter of the soil,

Ff denotes the maximum frictional resistance from the inner wall of the seepage channel,

FN denotes the normal force provided by the channel wall that supports the particle,

W′ denotes the submerged unit weight of the sediment particle,

φ denotes the angle of internal friction of the sediment particles, and

β denotes the slope angle of the seepage channel. Although the actual breaching process is a dynamic phenomenon characterized by non-equilibrium states, a static equilibrium assumption is adopted in this model as a necessary quasi-static approximation. This approach simplifies the identification of the critical threshold for soil initiation. Accordingly, the critical condition for the collapse of the seepage channel is derived as follows:

The critical velocity for particle initiation in the seepage channel can be calculated by solving Equations (19) and (20) as follows:

In the equation, νo is the critical initiation velocity of sediment particles. When ν > νo, sediment particles in the seepage channel begin to move. As the upstream inflow continues to increase, leading to a rise in hydraulic head within the channel, the flow persistently erodes the channel, resulting in the progressive enlargement of the leakage pathway.

Incorporating the influence of channel slope on hydraulic energy distribution, the governing role of friction velocity on incipient motion, and the modulating effect of soil gradation and strength on erosion rate, the formula for calculating the unit-width sediment transport rate in the seepage channel of a landslide dam [

12] is given as follows:

In the equation,

ν* is the shear (friction) velocity,

gs denotes the unit-width sediment transport rate within the seepage channel,

J represents the hydraulic gradient,

R’ is the hydraulic radius, and

Ls is the length of the seepage channel. The soil transport rate within the seepage channel is given by:

In the equation,

Gs denotes the sediment transport rate of the dam material, and

R denotes the radius of the seepage channel. Throughout the breaching process, the piping tunnel continuously dilates. Within a given time step Δ

t, the change in channel radius can be described by the following equation:

In the equation, ΔR denotes the increment in the radius of the seepage channel, χ denotes the wetted perimeter.

2.3.3. Evolution of Breach Failure Mechanisms

As the seepage channel expands, the stability of the channel roof decreases over time. Eventually, the extensive erosion creates a significant cavity, forming a vulnerable zone within the dam structure. The concomitant increase in the void span and reduction in shear resistance collectively weaken the vertical support offered by the underlying soil matrix. Insufficient to resist the overburden stress and hydraulic pressure due to strength degradation, the soil mass eventually undergoes gravity-driven collapse. The criterion for soil collapse is as follows:

In the equation, W represents the weight of the soil mass that collapses within the seepage channel; τf denotes the total shear resistance acting on both sides of the collapsing body; w is the width at the dam crest; yl and yr are the vertical heights of the soil above the left and right sides of the seepage channel, respectively.

The stability of the soil overlying the seepage channel relies heavily on the vertical shear resistance mobilized at the side interfaces. The area subjected to shear stress varies depending on the relative position between the dam crest breach and the seepage channel, as illustrated in

Figure 6. Under such conditions, the criterion for collapse of the soil-rock mass must be evaluated case by case. Specifically, the values of

yl and

yr differ according to the spatial relationship between the dam crest breach and the seepage channel. Based on geometric relationships, the expression for

yl can be derived as follows:

In the equation,

Hs represents the initial vertical distance from the center of the seepage channel to the dam crest. Based on geometric relationships, the expression for

yr can be derived as follows:

In the equation, Ls is the horizontal distance from the left dam shoulder to the vertical line passing through the center of the seepage channel; Lo represents the horizontal distance measured along the dam crest from the left abutment to the centerline of the initial breach.

The collapse of the seepage channel roof triggers an abrupt lowering of the breach invert elevation at the dam crest, thereby marking the transition from piping to overtopping failure. Consequently, the flow regime undergoes a transition from pressurized pipe flow to open-channel weir flow, the sediment transport equation must be converted from Equation (22) to Equation (9), and the outflow discharge equation must be converted from Equation (8) to Equation (6).

The proposed model incorporates several simplifying assumptions to ensure computational tractability of the coupled overtopping–seepage breaching process. These include an inverted trapezoidal initial breach geometry, equal vertical and lateral erosion rates during continuous erosion, and the assumption that seepage channels remain fully submerged prior to roof collapse. Such assumptions primarily affect the early-stage breach geometry and erosion initiation, whereas the later-stage breach evolution is predominantly governed by discharge magnitude and sediment transport capacity. Similar assumptions have been widely adopted in previous physically based breach models and have been shown to provide reasonable approximations for large-scale landslide dam failures.

Several empirical parameters are involved in the erosion and discharge formulations, including the discharge coefficient cd, seepage flow coefficient μc, breach side slope angle β, and sediment correction factor ξ. Variations in cd and μc, directly influence the magnitude of overtopping and seepage discharge, respectively, thereby affecting the timing of peak flow and the rate of breach enlargement. The breach slope angle β, primarily controls the stability of breach sidewalls and governs the occurrence of episodic slope collapse, while the sediment correction factor ξ. regulates erosion intensity under high-energy flow conditions.

In the present study, these parameters are selected based on values commonly reported in the literature and experimental studies, ensuring physically realistic and conservative predictions, as shown in

Table 1. While a systematic quantitative sensitivity and uncertainty analysis is beyond the scope of this work, the qualitative influences of these parameters are explicitly clarified to enhance model transparency and interpretability.

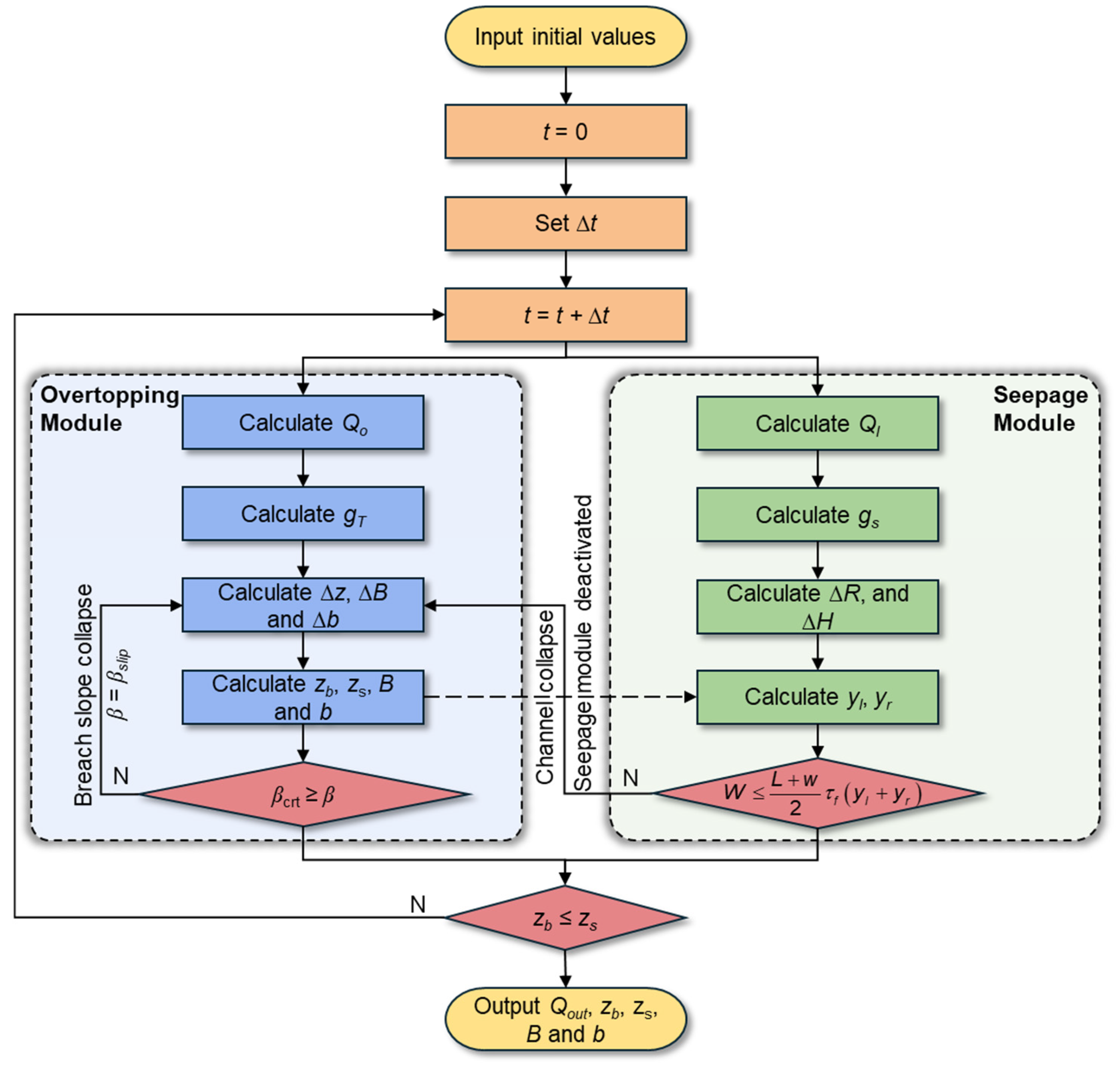

3. Numerical Calculation Process

The numerical model developed in this study employs an iterative computation approach to simulate the hydraulic evolution during the development of the seepage channel and the overtopping failure process. Specifically, the continuous simulation period is discretized into a sequence of small time steps Δt. In each time step, the hydraulic and geometric parameters are updated based on the state of the previous step. The specific numerical methods and computational procedures of the model are as follows:

Step 1: Input the initial conditions based on actual engineering project data. These parameters specifically include reservoir characteristics (e.g., water level, storage capacity), dam geometry (e.g., dam height, crest width, slope angle), and material properties (e.g., soil particle size, shear strength parameters).

Step 2: Specify the computational time step Δt.

Step 3: Initialize the calculation time, and make .

Step 4: Compute the overtopping breach outflow

Qo, and update the reservoir water level

zs by solving the mass conservation equation coupled with the nonlinear reservoir storage–elevation relationship established in

Section 2.1 (Equations (1)–(4)).

Step 5: Calculate the unit-width sediment transport rate at the breach gT.

Step 6: Compute the vertical incision increment Δz, and the lateral expansion increments of the breach top width ΔB and bottom width Δb.

Step 7: Update the breach bottom elevation zb, reservoir water level zs, breach top width B, and bottom width b based on the calculated analytical increments, ensuring that the updated geometric parameters remain within physically valid ranges.

Step 8: Check whether the breach side slope satisfies the stability criterion βcrt ≥ β; if not, return to Step 6. If the condition is met, proceed to the next step.

Step 9: Calculate the seepage flow rate through the internal erosion (piping) channel, denoted Ql.

Step 10: Determine the unit-width sediment transport rate gs within the seepage channel.

Step 11: Compute the radius increment of the seepage channel ΔR and the reservoir water level increment ΔH.

Step 12: Calculate the soil thicknesses yl and yr above the seepage channel on both sides, based on the longitudinal trapezoidal profile of the dam (as defined in Equation (26)). This accounts for the variation in soil depth along the flow direction.

Step 13: Quantitatively calculate the stability of the soil body above the seepage channel based on the limit equilibrium method using representative soil parameters. If the calculated factor of safety indicates instability, return to Step 6; otherwise, continue.

Step 14: Check whether the breach bottom elevation satisfies zb ≤ zs; if not, the breaching process continues. Return to Step 3 to increment the time step and perform the next iteration.

Step 15: Output the final results, including breach outflow Qout, bottom elevation zb, reservoir level zs, breach dimensions B and b.

The proposed model was implemented in Python (v3.12), and all numerical simulations were developed and executed using the PyCharm (v2025.3.1) integrated development environment (IDE). The codes were developed specifically for this study. The calculation process is shown in

Figure 7.

4. Case Study and Data

This study establishes a comprehensive model that reproduces breach progression under individual hydraulic loads as well as the synergistic effects of seepage and overtopping. Therefore, the model validation is conducted under three different scenarios, including overtopping breach, seepage breach, and coupled overtopping-seepage breach of the landslide dam. Considering the scarcity of real-time field data for internal erosion, the validation utilizes a combination of well-recorded field case histories (for overtopping) and high-resolution laboratory experimental data (for seepage and coupled mechanisms). This comprehensive approach allows for a thorough assessment of the model’s applicability and reliability under different breach mechanisms.

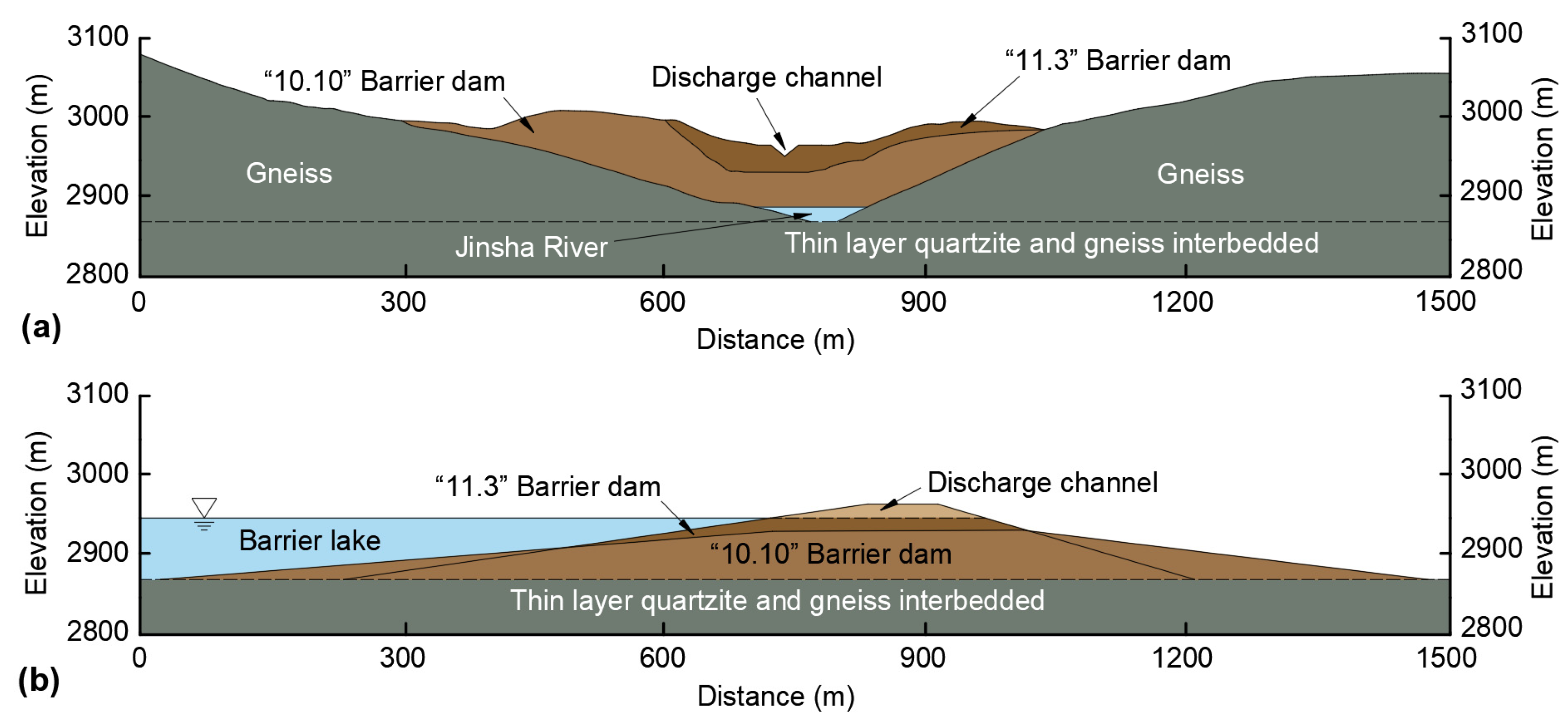

4.1. “11 3” Baige Landslide Dam

In October 2018, successive landslide events occurred in the Tibet Autonomous Region and Sichuan Province. On 10 and 17 October, massive slope failures blocked the Jinsha River (at the Changdu-Baiyu border) and the Yarlung Tsangpo River (in Milin County), respectively. Subsequently, on 29 October and 3 November, recurring landslides at the same locations resulted in the re-damming of these rivers. Among these four cases, the ‘11.3’ Baige landslide dam on the Jinsha River is the most representative and possesses the most comprehensive dataset due to the extensive emergency monitoring. Consequently, it is selected as the case study for the numerical calculations. This case illustrates an overtopping-dominant collapse, where the collapse is primarily driven by water pressure from overtopping floods.

The actual crest elevation of the ‘11.3’ Baige landslide dam is adopted as the initial top elevation of the dam in the simulation, with the original riverbed elevation of 2870 m considered as the bottom elevation. Based on the data obtained from geological field surveys, the dam height is determined to be 96 m, with the corresponding elevation of the dam crest at 2966 m. The longitudinal width and transverse length of the dam are 200 m and 700 m, respectively, as shown in

Figure 8. Although the landslide dam exhibits spatial irregularities, the breaching process is hydraulically controlled by the geometry of the overflow path. Therefore, the cross-sectional profile at the specific location of the initial breach is selected as the representative model for the simulation. Therefore, the cross-sectional profile at the specific location of the initial breach is selected as the representative model for the simulation. Based on the survey, the upstream and downstream slope ratios are set to 1:2.7 and 1:5.5, respectively. The specific calculation parameters adopted in the model are detailed in

Table 2.

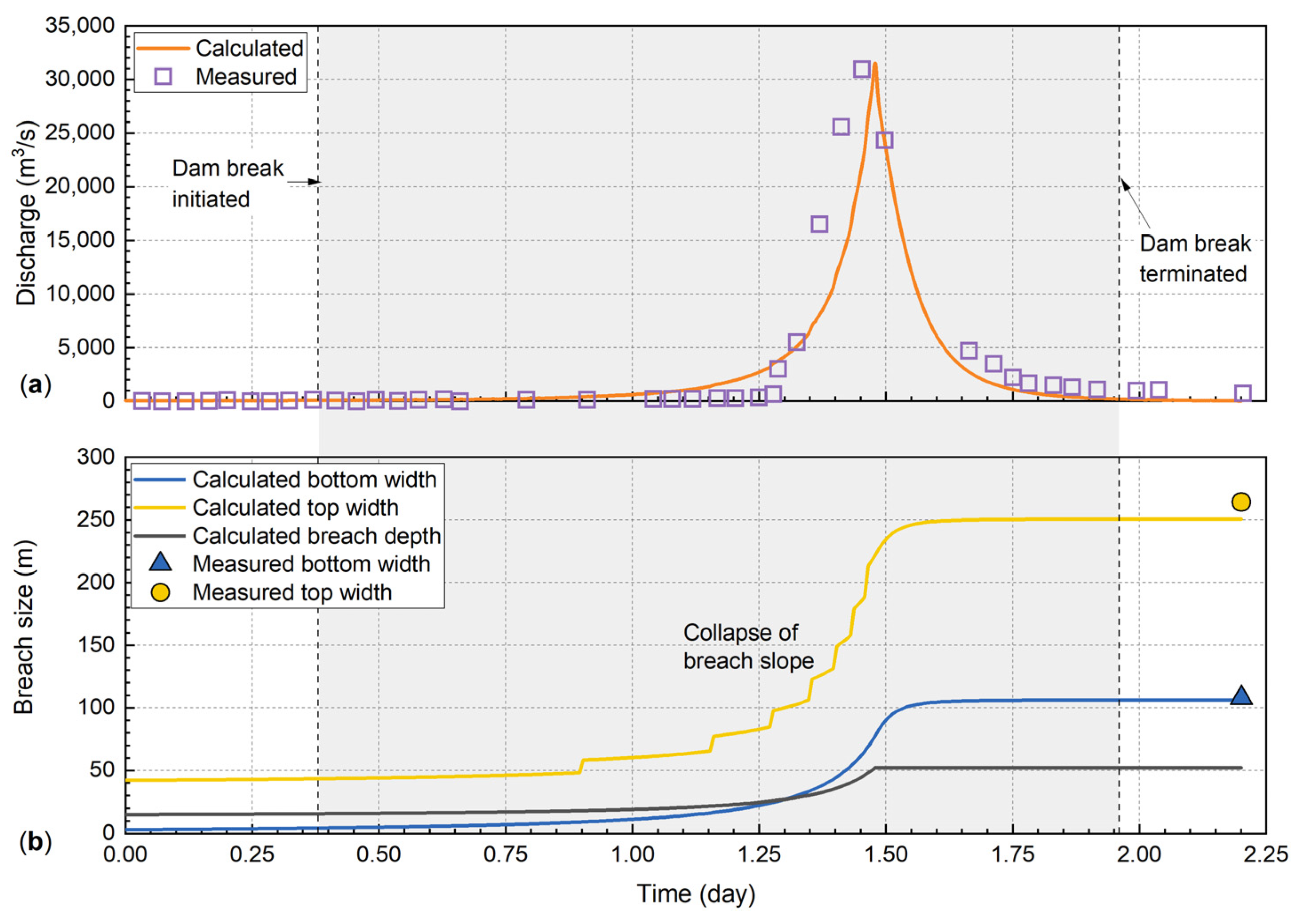

Figure 9 presents the simulation results for the ‘11.3’ Baige landslide dam, specifically depicting the discharge hydrograph and the geometric progression of the breach. When seepage channels were omitted (i.e., the initial channel radius was set to zero, representing overtopping breach only), the modeled breach hydrograph matches the measured data. However, the model underestimates the early-stage increase in discharge compared to observations, which is attributed to uncertainties in the reservoir volume–elevation relationship derived from rapid emergency surveys. Despite this initial deviation, the model accurately captures the peak discharge and the overall flood propagation process. The computed breach development curve is consistent with the discharge evolution, exhibiting a positive correlation between breach widening rate and discharge. Although continuous real-time monitoring of the breach morphology was challenging during the emergency, intermittent field observations and the recorded discharge hydrograph provide sufficient constraints for validation. The calculated residual bottom width is consistent with field observations, but the crest width exhibits a slight under-prediction.

A quantitative analysis was carried out on several key parameters of the landslide dam breach process. The simulated and measured values of the key breach parameters, i.e., peak breach flow (

Qp), time to peak discharge (

Tp), final breach top width (

Bf), final breach bottom width (

bf), final breach depth (

Hf′), and measured data, are shown in

Table 3. The comparative analysis indicates that the simulated peak discharge aligns closely with the field measurements, whereas the time to peak exhibits a slight temporal lag relative to the observed data. The greatest discrepancy occurs in the residual breach crest width, which the model underestimates by 5.07%. These minor discrepancies are primarily attributed to the model assumptions: the delay in peak timing is likely associated with the uncertainties in the reservoir storage curve described earlier, while the underestimation of the crest width stems from the simplification of the side slope failure mechanism. The model assumes a continuous evolution based on limit equilibrium, whereas actual breaches often involve stochastic, intermittent block collapses driven by local material heterogeneity, which can lead to rapid widening. Nevertheless, the model reliably reproduces the overtopping-induced breach process under a single-factor scenario and, to a considerable extent, simulates the real-world overtopping failure behavior of landslide dams.

The reservoir storage–area relationship plays a fundamental role in governing the temporal evolution of water level and, consequently, the breach hydrograph. In the Baige case, the early-stage discharge is slightly underestimated, which can be partially attributed to the irregular reservoir geometry that deviates from the idealized power-law relationship assumed in Equations (2)–(4). Errors in the fitted parameters

αr and

mr directly affect the rate of water-level rise, thereby propagating into uncertainties in both peak discharge and peak arrival time. Specifically, underestimation of reservoir surface area at lower water levels may lead to a slower simulated water-level increase and delayed breach initiation, while overestimation may result in an earlier and more abrupt hydrograph response. Although a systematic sensitivity analysis of

αr and

mr is beyond the scope of this study, the present formulation is flexible and allows direct incorporation of observed volume–elevation or area–elevation data when such measurements are available, which would further improve predictive accuracy for reservoirs with complex geometries. Similar observations regarding the influence of storage geometry on water-level dynamics have been reported in related hydraulic studies [

65].

4.2. Rio Toro Landslide Dam

This study validates the proposed breach mathematical model using a real-world landslide dam failure induced by seepage. It should be noted that, owing to the scarcity of fully documented seepage-failure cases [

12], the breach of the Rio Toro landslide dam [

66] in Costa Rica was chosen as the validation case, as it provides relatively complete parameter and process records. The Rio Toro landslide dam formed on 13–14 June 1992 in Costa Rica, when intense tropical rainfall triggered a massive rockslide that deposited about 3 × 10

6 m

3 of debris into the narrow river canyon. The slide consisted of fragmented andesitic rock (with blocks up to 8 m in diameter) and soil, which completely blocked the channel, as shown in

Figure 10.

The landslide dam on the Rio Toro was about 75 m long (cross-canyon dimension) and 600 m wide (parallel to the axis of the canyon); its height was nearly 100 m on the right side of the canyon and tapered to 70 m where the toe of the slide abutted the left canyon wall. The lake impounded by the blockage attained a maximum length of 1200 m. The maximum elevation of lake level (after 3 days of filling) was estimated to be 936 m, giving a maximum lake depth of 52 m. Based on these dimensions, maximum lake volume was estimated at nearly 500,000 m3. One month later, on 13 July, heavy rainfall generated floodwater that passed through the dam, initiating extensive internal piping and ultimately triggering collapse of the dam body. This case represents a seepage-dominant collapse, where the primary mechanism driving the collapse is the infiltration of water into the soil, weakening its shear strength.

Utilizing the mathematical model developed in this work, the seepage-induced breaching process of the Rio Toro landslide dam was simulated to further validate the model’s performance. The specific parameter values employed in these calculations are summarized in

Table 4.

The simulation results for the seepage-induced breaching of the Rio Toro landslide dam are presented in

Figure 11. Based on the simulation results, key breach parameters were first validated against field measurements. For the breach discharge process, while the peak timing is documented in the literature, the calculated discharge peak occurs slightly earlier than observed. Additionally, in the present case, the timing of the peak discharge is perfectly synchronized with the collapse of the overlying soil layer within the seepage channel. This indicates that the breach discharge peaks at the moment the upper soil layer collapses, after which both the breach head and discharge gradually decrease. Regarding the final breach dimensions, the breach formed after the dam failure is irregular, and the literature provides a general range for the breach width. The calculated values for both the top and bottom widths of the breach fall within this observed range, and the computed breach depth also aligns with the measured results.

A quantitative analysis of the calculation errors for key breach parameters is provided in

Table 5. As shown in the table, the largest error occurs in the time to peak discharge, where the calculated value is slightly smaller, making the results more conservative. The calculated residual breach dimensions remain consistent with the range of measured values reported following the dam failure. Comparing the simulated breach processes with key parameters demonstrates that the proposed model satisfactorily captures seepage-driven failure in landslide dams, particularly regarding the structural collapse of the seepage channel.

4.3. Large-Scale Experiment by Zhou [42]

The overtopping-seepage failure mechanism typically begins with seepage along the downstream slope, which then triggers erosion caused by overtopping. In high-altitude regions, the narrow valley geometry and limited reservoir volume often lead to rapid upstream flooding once a landslide dam forms. These conditions tend to mask visible signs of seepage, leading to the common assumption that breaching is solely caused by overtopping [

67]. However, landslide dams are often made of poorly graded, unconsolidated, and structurally heterogeneous materials, which inherently promote seepage development [

39]. As a result, combined overtopping-seepage failure is common in natural settings. To better understand this process, Zhou [

42] conducted experimental simulations to replicate the landslide overtopping-seepage breaching (

Figure 12). This experiment was therefore employed to verify the predictive capability and robustness of the mathematical model proposed in this study. This case involves a coupling effect collapse, where multiple factors, including hydrological and geological influences, contribute to the failure.

The geometric configuration of the model dam was normalized to ensure scale-independent analysis. To promote seepage through the dam body, the height-to-length ratio was intentionally increased to 0.36, effectively making the dam thinner and thereby reducing the seepage path. The dam height was 2.0 m, with a crest length of 8.0 m and a base length (in the flow direction) of 10.0 m. To ensure the numerical simulation accurately corresponds to the physical experiment used for validation, the material properties were strictly set according to the experimental conditions reported by Zhou et al. [

42]. Regarding dam materials, to replicate the gradation characteristics of a typical landslide dam, sediment from the Jiangjiagou debris flow fan was used. This material had a moisture content of 6 ± 0.5% and a broad particle size distribution, ensuring that the model dam closely resembled field conditions. Additional parameters used for breach calculations in the model dam are listed in

Table 6.

Using the mathematical model proposed in this study, calculations were carried out for the combined erosion dam breach experiment. The simulated outcomes were then compared with the experimental records, as shown in

Figure 13. In the model experiments, most of the recorded results were presented using dimensionless parameters, and the relationships between key variables were analyzed, for example, the relationship between

Q/(

gd505)

0.5 and

wb/

d50, where

wb represents the water surface width at the breach. It should be noted that the initial value of

wb/

B~

t is expected to be 1, but Zhou [

42] used 0, which contradicts the actual initial condition of the breach channel. Suspecting this to be a data error in the cited source, this comparison is excluded from the present validation. Instead, the focus here is on validating the simulation results for breach outflow, reservoir water level, and breach side slope angle.

As shown in

Figure 13a, the model can reasonably reproduce the breach outflow during both the rising and falling stages. It is noted that the simulated rising limb of the outflow hydrograph is slightly steeper than the measured values. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the model’s assumption of instantaneous erosion response once the hydraulic threshold is exceeded, whereas in the physical experiment, the initial erosion process may involve a time lag due to soil softening or temporary blockage by collapsed blocks. Despite this, the computed reservoir water levels generally match the observed data, and the model accurately captures the peak discharge magnitude, demonstrating its capability in simulating the overall hydraulic process.

Regarding the breach side slope angle (

Figure 13b), the model captures the general trend of initial steepening followed by gradual stabilization. However, the model-predicted final slope angle is slightly lower. This underestimation is likely because the limit equilibrium method used in the model does not fully account for the apparent cohesion provided by matric suction in the unsaturated soil or the transient stability of steep slopes during rapid drawdown, which allows the experimental breach slopes to remain steeper than the theoretically calculated stable angle. Additionally, the temporal evolution of the breach top and bottom widths is depicted. The slope of these curves is positively correlated with the breach discharge. Overall, the mathematical model is capable of simulating the overtopping-seepage breaching process with reasonable accuracy.

From a quantitative standpoint, as summarized in

Table 7, the mathematical model exhibits high fidelity in predicting the key breach discharge parameters, including the peak flow and the time to peak, both with errors within approximately 5%. The final breach top width

Bf and bottom width

bf could not be validated due to the lack of corresponding measured data. This geometric underestimation reflects the conservative nature of the stability parameters used in the model (ignoring matric suction), which leads to a flatter predicted slope. However, this discrepancy has a minimal impact on the overall discharge simulation, as evidenced by the high accuracy of the peak flow and timing predictions, confirming the model’s reliability for flood hazard analysis. The largest deviation was observed in the final breach side slope angle

βf, which was 15.3% smaller than the measured value. This discrepancy is primarily attributed to the fact that the model simulates the breaching process of a landslide dam under combined erosion (overtopping and seepage). The presence of seepage channels or zones within the dam leads to internal saturation, creating significant differences in soil properties between saturated and unsaturated regions. In particular, both cohesion and the internal friction angle, which are critical for erosion resistance and shear strength, vary considerably. To account for this, the model used conservatively low estimates of these parameters as input, resulting in a faster erosion rate, earlier peak discharge time, quicker reservoir drawdown, and ultimately a gentler final breach slope angle. This limitation underscores the complexity of the coupled failure mechanism and highlights a critical direction for future model refinement: specifically, incorporating the dynamic evolution of soil mechanical properties in response to the transient seepage field to better capture the progressive weakening process. This also highlights an area where the model requires further refinement.

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Geometric Approximations in Seepage Channel Collapse

Equation (25) through Equation (29) determine the critical conditions for the soil roof collapse based on idealized geometric assumptions. However, in natural landslide dams, the internal structure and the relative position of the seepage channel often exhibit irregularities that deviate from these simplified geometries. To quantify the potential errors introduced by these approximations, a sensitivity analysis was conducted. The Rio Toro case was specifically selected for this analysis because its failure mechanism was dominated by the expansion of the seepage channel and the subsequent roof collapse, making it highly sensitive to the collapse criterion (Equation (26)).

A geometric shape factor

η was introduced to perturb the calculated weight of the soil mass

W to account for uncertainties in both topographic morphologies. The modified collapse criterion is expressed as:

Simulations were performed with varying values of η to represent scenarios where the effective soil overburden is either underestimated or overestimated.

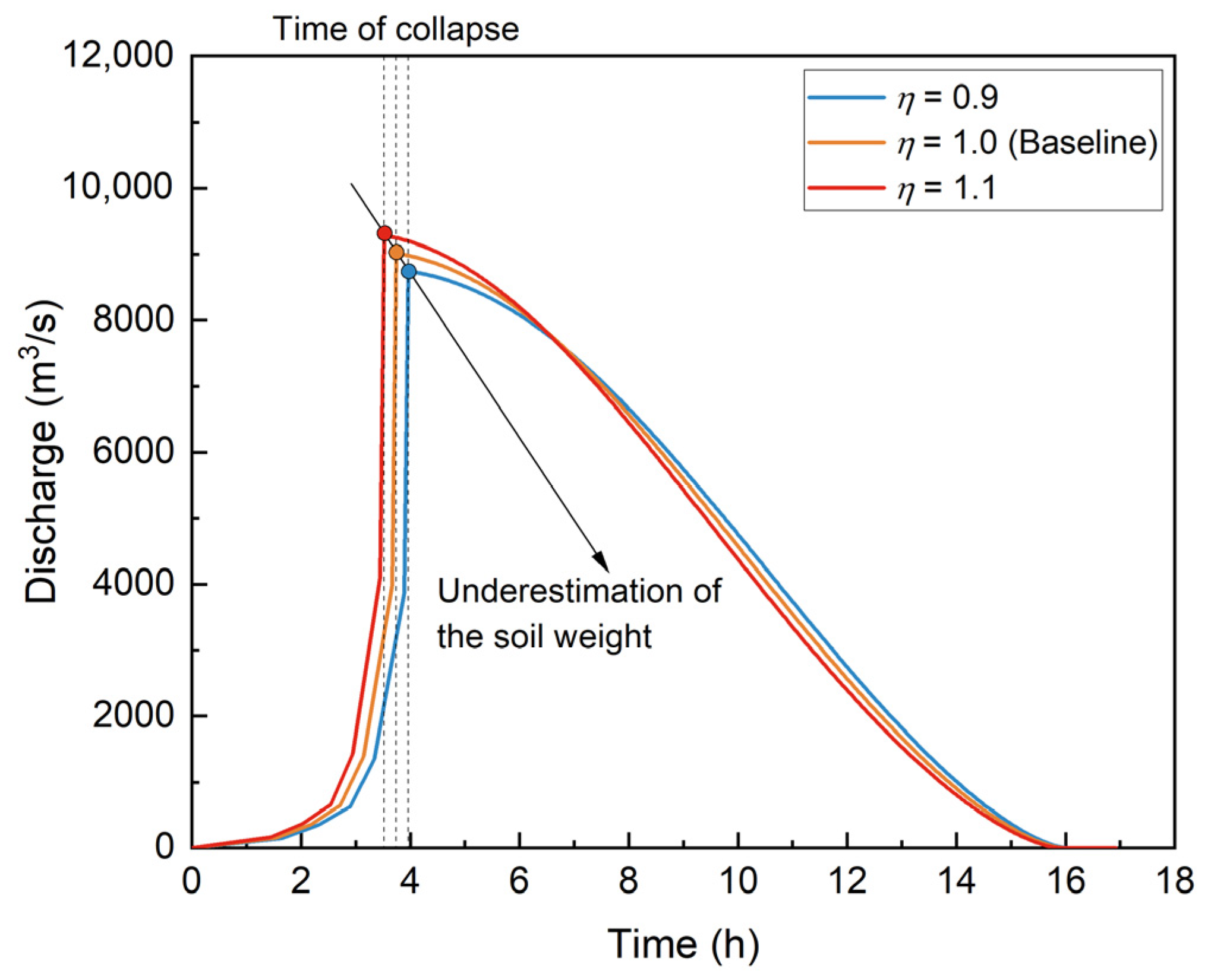

As illustrated in

Figure 14, the results indicate that geometric uncertainty primarily affects the temporal evolution of the breach. An increase in soil weight

η = 1.1 accelerates the satisfaction of the failure criterion, resulting in an earlier onset of the collapse and a leftward shift in the hydrograph. Conversely, a decrease in weight

η = 0.9 delays the breach process. Notably, a ±10% variation in

η resulted in a deviation of approximately ±6% in the time to peak discharge

tp and a minor fluctuation of ±3% in the peak discharge

Qp. These output variations are smaller than the input perturbation itself, indicating that the potential bias in soil weight arising from geometric simplifications has a limited impact on the breach outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study proposes a novel mathematical model to simulate the complex breaching process of landslide dams, specifically addressing the limitation of traditional models that typically consider only single failure modes. By integrating surface erosion and internal erosion modules, the new model captures the coupled mechanisms of overtopping and seepage-induced failure, as well as their complex interactions, which allows for a more comprehensive simulation of real-world landslide dam failures compared to existing single-factor approaches. It is capable of resolving three typical scenarios: overtopping-only breaching, seepage-only breaching, and coupled erosion breaching. This modeling approach extends the applicability of existing models and significantly enhances the ability to simulate complex breaching processes. Compared with previous breach models that consider overtopping or seepage mechanisms separately, the proposed framework explicitly resolves the interaction between surface and internal erosion within a unified time-stepping scheme, leading to a more physically consistent representation of breach evolution.

The proposed model consists of three main modules: (1) a reservoir volume calculation module based on water balance, which updates the reservoir water level in real time; (2) a generalized breach discharge module that separately computes flow rates from the dam crest breach and internal seepage channels, enabling real-time updates of discharge at different breach locations; (3) a generalized breach expansion module based on a non-equilibrium erosion formula, which simulates continuous headcutting at the dam crest, instability-induced slope failure, and seepage channel development, thereby updating breach geometry dynamically. Finally, a time-stepping numerical scheme is introduced to integrate and couple these three modules, enabling the full operation of the mathematical model.

The robustness of the proposed model was verified using three diverse case studies, each corresponding to a specific breaching mode. For overtopping-induced breaching, the model can effectively reconstruct the breaching hydrodynamics of the ‘11.3’ Baige landslide dam, with key breach outcomes showing errors within 5% of the observed data. For seepage-induced breaching, the model was subsequently employed to simulate the seepage-induced failure process of the Rio Toro landslide dam. Although limited case data are available for this breaching mode, the simulated results generally matched the available monitoring records. For coupled erosion breaching, the model predicted breach discharge with an error of approximately 5%. However, the accuracy of breach geometry simulation was affected by the selection of soil shear strength parameters. Nevertheless, while the current results demonstrate the model’s capability in predicting key hazard parameters, future validation against emerging high-quality field data or large-scale experiments remains necessary. Overall, the predictive accuracy achieved in the present case studies is comparable to, and in some cases improves upon, the performance reported in previous landslide dam breach simulations, particularly for scenarios involving coupled failure mechanisms.

Furthermore, the robustness of the model was validated through a sensitivity analysis regarding the geometric approximations of the soil roof. By introducing a ±10% perturbation to the soil weight, we observed that the resulting fluctuations in the breach hydrograph were relatively minor (approximately ±6% for tp and ±3% for Qp). These findings confirm that the errors introduced by geometric simplifications are dampened in the simulation process, and the model remains reliable for predicting the magnitude of breach hazards. Overall, distinct from existing dam breach models that typically focus on a single failure mode, the proposed model demonstrates a broader applicability by effectively simulating the complex evolution process under coupled overtopping-seepage conditions. This capability provides a comprehensive tool for assessing landslide dam risks where multi-hazard interactions are involved.

It is important to acknowledge the complexity introduced by the spatial variability of soil properties under coupled erosion. The current model generally assumes saturated conditions for critical erosion zones to ensure a conservative estimation of breach risks. However, in reality, the mechanical characteristics of the soil—specifically cohesion and internal friction angle—vary significantly between saturated and unsaturated zones due to matric suction. As pointed out in recent studies, estimating the transient soil saturation profile, particularly around internal seepage pathways, is essential for a more precise understanding of breach evolution. Therefore, future work will focus on incorporating unsaturated soil mechanics by establishing a quantitative relationship between soil saturation and mechanical properties, thereby enabling the model to dynamically update these critical parameters during the seepage-erosion process. This represents a challenging but critical direction to further improve prediction accuracy. To support this theoretical development, future research will also prioritize the execution of large-scale physical model tests equipped with high-precision sensor arrays (e.g., pore pressure and suction transducers). These experiments will provide the necessary benchmark data to validate the dynamic evolution of the saturation field and the corresponding soil property degradation.

From a practical standpoint, the coupled overtopping–seepage breaching model is most advantageous in situations where internal erosion processes are likely to play a significant role in dam failure. Such conditions commonly include landslide dams composed of loose or heterogeneous materials, cases where seepage or piping indicators are observed prior to overtopping, or scenarios involving rapid reservoir level rise under uncertain internal drainage conditions. In these circumstances, overtopping-only models may underestimate breach initiation timing or peak outflow by neglecting the contribution of internal erosion, whereas the proposed coupled framework allows a more realistic representation of the breaching mechanism and its evolution.

For real-time or near-real-time emergency simulations, the model can be implemented using a limited but essential set of input data, including dam geometry, inflow hydrograph, bulk soil density, and approximate soil strength parameters derived from regional empirical ranges or analogous case studies. The sensitivity analysis indicates that moderate uncertainties in these parameters have a relatively limited impact on key hazard indicators, supporting the robustness of the model for rapid hazard screening. In post-landslide emergency response, the model may therefore be used to quickly identify the dominant breaching mode, estimate critical indicators such as peak discharge and time to peak, and iteratively update hazard assessments as new monitoring information becomes available. This practical applicability enhances the value of the proposed model as a decision-support tool for landslide dam risk management under complex, multi-hazard conditions.