3.1. Design of WPCSMH Fire-Retardant Hydrophobic Coating

Figure 1 illustrates the preparation process of the flame-retardant coating, which is composed of bio-based components including sodium phytate, chitosan, sodium alginate, and gelatin. This study employs a layer-by-layer self-assembly technique, utilizing electrostatic interactions between negatively charged sodium phytate (PA-Na), positively charged chitosan (CS), and negatively charged sodium alginate (SA) to achieve controllable deposition of a flame-retardant and hydrophobic multilayer film on the wood surface. This surface-confined deposition mode enables the efficient enrichment of flame-retardant components at the material-environment interface, providing effective surface protection for the wood.

As the sodium salt of phytic acid, PA-Na contains abundant phosphate groups in its molecular structure, which decompose at elevated temperatures to generate phosphoric acid and polyphosphoric acids. These compounds effectively catalyze wood dehydration and promote the formation of a dense char layer, thereby exerting a dual flame-retardant mechanism in both the gas and condensed phases. Compared to phytic acid, PA-Na exhibits higher water solubility and milder acidity, facilitating uniform dispersion within the coating. This not only enhances flame-retardant performance but also avoids acid-induced corrosion of the wood substrate, achieving an optimal balance between flame retardancy and material compatibility.

The coating system achieves highly efficient flame retardation through a nitrogen-phosphorus (N-P) synergistic effect: CS serves as a nitrogen source, while PA-Na acts as a phosphorus source. During pyrolysis, these components interact to form an intumescent char layer, resulting in a significant N-P synergistic flame-retardant effect. To further enhance the flame-retardant performance, gelatin was introduced to increase the nitrogen content of the coating, while SA extracted from brown algae was incorporated as a natural non-combustible component, collectively improving the fire barrier properties of the coating.

All coating components are derived from renewable and environmentally friendly natural materials: PA-Na is extracted from plant seeds, CS is obtained from crustacean waste such as shrimp and crab shells, gelatin is derived from natural sources such as pigskin or sea cucumber, and SA is sourced from algae. The overall composition aligns with the design concept of green and sustainable materials. Furthermore, the introduction of sodium methyl silicate confers excellent hydrophobic properties to the coating, which not only improves the water resistance and weather durability of the wood but also expands its potential for application in humid or harsh environments.

3.2. Morphology, Physical and Chemical Structure Characteristics

This study employs X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis to elucidate the elemental chemical states and composition of the samples.

Figure 2a presents the full spectrum analysis results of the WPC-SMH composite material. Distinct characteristic peaks are observed at binding energies of approximately 532 eV, 400 eV, 26 eV, 102 eV, and 134 eV, corresponding to the O 1s, N 1s, C 1s, Si 2p, and P 2p orbitals, respectively. The peaks at 284.8 eV, 286.6 eV, 288.3 eV, and 289.4 eV are attributed to C=C, C-C, C-O, and C=O bonds, respectively [

27]. Additionally, the peaks at 400.3 eV and 399.0 eV correspond to NH

3+ and N-H configurations, respectively [

28]. The O1s peaks correspond to different oxygen functionalities: O=P (535.5 eV), O-P (533.9 eV), O-C (532.6 eV), and O-H (530.7 eV) [

29].

Spectral analysis reveals that oxygen (O) constitutes the predominant element in the sample, attributable to multiple sources: hydroxyl (-OH) groups within wood cellulose, ether bonds (C-O-C) present in chitosan (CS) molecular chains, carboxylate groups (-COO-) in sodium alginate (SA), and phosphate groups (-PO4) in phytic acid (PA). The XPS results confirm the successful incorporation of key components: a Si 2p peak (102 eV) indicates sodium methyl silicate for hydrophobicity; an N 1s peak (400 eV) comes from gelatin and chitosan; and a P 2p peak (134 eV) verifies sodium phytate. The phosphorus-nitrogen synergy endows flame retardancy, while the low carbon signal reflects its singular sources. This distribution pattern aligns with the material design, wherein intermolecular interactions foster a stable multiphase system.

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) analysis of the chemical structures of WPC, WPCS, WPCSM, and WPCSMH samples is depicted in

Figure 2e. All samples exhibit an O-H stretching vibration peak for H

2O near 3333 cm

−1, while the characteristic -C-H stretching vibration peak of chitosan is observed at 2916 cm

−1. The WPC sample displays characteristic vibration peaks at 1505 cm

−1 and 1030 cm

−1, associated with P=O and O-P-C bonds, respectively, confirming the successful formation of a composite coating between phytate and chitosan. Furthermore, no significant shifts in characteristic peak positions were observed across all samples, indicating that the interactions between components were predominantly physical in nature and did not disrupt the original chemical structures.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to characterize the surface morphology and coating coverage on the wood substrates. As shown in

Figure 3a, the cross-section of untreated poplar wood exhibits its inherent porous anatomical structure, featuring parallel-aligned tracheids and well-defined cell walls, with a smooth surface free of foreign deposits. This highly porous and ordered microstructure provides an ideal substrate for the penetration and anchoring of subsequent functional molecules.

After treatment with the bio-based composite coating (

Figure 3b–e), the surface morphology of the wood underwent significant changes. A continuous and dense coating layer, composed of chitosan (CS), sodium phytate (PA-Na), and sodium methyl silicate, was observed to uniformly cover the wood surface. The coating effectively penetrated and filled the micro-scale grooves between tracheids and lumens, markedly reducing the surface roughness and porosity of the substrate. Higher-magnification images revealed a tightly bonded interface between the coating and the wood matrix with no visible defects, indicating that the self-assembly process promoted strong adhesion to the wood cell walls.

Notably, the composite coating exhibited good transparency at the macroscopic level, preserving the natural wood grain, as visually confirmed in samples subjected to cone calorimetry tests. At the micro-scale, the coating displayed a uniform micro-nano roughness, which is considered a key structural feature for constructing a highly hydrophobic surface. Moreover, the continuity and integrity of the coating are critical to its flame-retardant performance, as it acts as an effective physical barrier during the initial stages of combustion, inhibiting the transfer of heat and flammable gases, thereby significantly enhancing the fire resistance of the wood.

The integration of FTIR, SEM, and XPS analytical results confirms the formation of a stable interfacial bond between the coating materials and the wood substrate. This bonding mechanism not only guarantees the robust adhesion of the coating but also elucidates why the ultra-thin coating can still achieve remarkable surface modification effects, thereby indicating the successful preparation of the WPCSMH sample.

3.3. Flame Retardancy Performance

The flame-retardant properties of the samples can be systematically evaluated through various testing methods, among which the Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI) test, open flame tests, and cone calorimetry experiments are the most representative characterization techniques.

The Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI) test is a critical metric for assessing the flame-retardant performance of materials. It is defined as the minimum volume fraction of oxygen required to sustain the continuous combustion of a material in a nitrogen-oxygen mixed gas environment. A higher LOI value indicates superior flame-retardant properties of the material. In this study, the LOI values of different composite materials were systematically evaluated, revealing that the LOI of untreated poplar wood was 22.0%, demonstrating typical flammability characteristics (

Figure 4a). The LOI of wood composites modified with sodium phytate and chitosan (WPC) significantly increased to 29.7%, reflecting an improvement of 7.7 percentage points over pure wood. This notable flame-retardant effect can be primarily attributed to the phosphoric substances generated from the thermal decomposition of sodium phytate, which facilitate the formation of a char layer, while the nitrogen-containing groups within chitosan contribute to a phosphorus-nitrogen synergistic flame-retardant effect.

The further incorporation of sodium alginate in the WPCS samples resulted in an LOI value of 31.6%, marking a 9.6 percentage point increase compared to pure wood. This improvement may be due to the sodium carboxylate groups in sodium alginate promoting the formation of a denser char layer. When gelatin-modified chitosan was used to prepare the WPCSM samples, the LOI value was further enhanced to 32.1%, an increase of 10.1 percentage points relative to pure wood. The LOI value was further improved to 32.1% for the WPCSM sample (with gelatin-modified chitosan), which is 10.1 percentage points higher than that of pure wood. This enhancement stems from the amino groups (-NH

2) in gelatin, which promote the formation of a more stable expanded char layer at high temperatures and strengthen the phosphorus-nitrogen synergistic effect. The best performance was achieved by the WPCSMH sample (with sodium methyl silicate), reaching an LOI of 34.0%, a 12 percentage point increase over pure wood. This finding confirms that the inclusion of sodium methyl silicate not only does not diminish the material’s flame-retardant properties but further enhances flame retardancy by forming a silicon-oxygen network barrier and a stable silicon-carbon composite char layer. These results systematically demonstrate the synergistic enhancement of wood flame-retardant properties through bio-based self-assembly and hydrophobic treatment (

Figure 5).

This study conducted detailed observations and analyses of the combustion behavior of materials using open flame tests. The experimental results indicate that untreated pure wood samples ignited by a spirit lamp flame (approximately 500–600 °C) exhibited immediate combustion upon removal of the ignition source after 10 s, accompanied by significant flame propagation. During an extended observation period of 80 s, the combustion did not exhibit any tendency to self-extinguish; instead, the fire rapidly intensified alongside the accumulation of thermal release, ultimately resulting in complete carbonization of the sample. This typical combustion behavior underscores the inherent flammability of wood as a natural polymer material, with its rapid thermal decomposition and sustained gas-phase combustion posing significant fire hazards in practical applications.

In this study, a series of bio-based flame-retardant wood composites were designed and prepared, with experimental data demonstrating markedly different combustion characteristics for these flame-retardant treated materials. Under identical ignition conditions, the WPC samples exhibited a minimal flame within 1 s of removing the ignition source, with only small flickers visible, and the flame extinguished completely within 3 s, with no re-ignition occurring during the subsequent 20 s of observation. When 2 wt% sodium alginate was further introduced to produce the WPCS samples, the extinguishing time remained approximately 3 s. The WPCSM and WPCSMH samples exhibited even superior flame-retardant performance, with extinguishing times reduced to 2 s, indicating that the incorporation of sodium methyl silicate did not diminish flame retardancy or promote combustion.

The Cone Calorimeter Test serves as an effective means to realistically simulate the combustion behavior of materials in actual fire scenarios. This test evaluates the combustion characteristics of materials by measuring key parameters such as the Heat Release Rate (HRR). As illustrated in

Figure 4b, upon ignition of the samples, the HRR values rose sharply, reaching the first peak value (PHRR1) in a short period, primarily due to rapid surface combustion. Subsequently, a char layer began to form on the material’s surface, which acted as an effective thermal barrier, significantly inhibiting the transfer of external oxygen and heat, leading to a gradual decline in HRR values. As combustion continued, the char layer fractured under high temperatures, allowing unburned material to contact oxygen and ignite further, resulting in a second heat release peak (PHRR2) until the sample was completely consumed.

Experimental results demonstrated that both pure wood and WPCSM exhibited a bimodal HRR curve. However, the two heat release peaks for WPCSM (PHRR1 and PHRR2 measured at 149 kW/m2 and 162 kW/m2, respectively) were significantly lower than those of pure wood. This phenomenon can be attributed to the presence of the flame-retardant coating on the WPCSM surface, which not only slowed the combustion process but also facilitated the formation of a dense char layer, effectively reducing the material’s heat release rate. Additionally, the occurrence of PHRR1 for WPCSM was earlier than that of pure wood, potentially due to the catalytic effect of the flame-retardant coating accelerating the initial char formation process. Conversely, the timing of PHRR2 was delayed relative to pure wood, likely due to the protective nature of the flame-retardant layer, which allowed the treated samples to undergo dehydration and char formation more rapidly under the influence of sodium phytate, resulting in an earlier peak. The robust protective action of the char layer effectively resisted the penetration of heat from the flame.

The aforementioned results provide compelling evidence that the WPCSM exhibits superior flame-retardant performance compared to pure wood, as indicated by its lower heat release rate, which significantly reduces the risk of flame propagation during a fire. Experimental data demonstrate that this bio-based flame-retardant system manifests remarkable effectiveness through multi-component synergistic interactions: sodium phytate facilitates the formation of a dense char layer that acts in both gas and condensed phases to confer flame retardancy, while simultaneously forming a phosphorus-nitrogen synergistic system with chitosan. Sodium alginate enhances the stability of the char layer, and sodium methyl silicate imparts hydrophobic properties, effectively suppressing combustion while avoiding environmental toxicity issues.

Total Heat Release (THR) is a critical parameter for quantifying the total thermal energy released during the combustion process of materials, with its value accumulating as combustion time progresses. As depicted in

Figure 4c, the trend in the THR curve reflects the combustion behavior of the materials: a gentler slope on the curve indicates less heat released per unit time, thereby suggesting better flame-retardant performance. The experimental results indicate that the combustion process of WPCSM commenced earlier than that of pure wood, resulting in a slightly higher THR value during the initial phase (0–150 s). However, after 150 s, the rate of THR increase for WPCSM markedly declined, and the gap between it and pure wood gradually widened. Ultimately, the THR for pure wood reached 72.0 MJ/m

2, while the THR for WPCSM was only 53.8 MJ/m

2, representing a reduction of 25.3% (18.2 MJ/m

2). This difference can be primarily attributed to the presence of the flame-retardant coating on WPCSM, which not only promotes the formation of a dense char layer to effectively inhibit further combustion of the fuel but also reduces the release of pyrolysis products, thereby significantly lowering the total heat release. This clearly demonstrates that WPCSM possesses superior flame-retardant properties compared to pure wood, as evidenced by its lower THR value, indicating its capacity to effectively mitigate heat release and reduce fire hazards.

Total Smoke Production (TSP) is a crucial parameter for assessing the total volume of smoke released during combustion, which has significant implications for fire safety and evacuation. Smoke can obstruct visibility during a fire, thereby hindering escape, and inhalation can lead to incapacitation, resulting in missed opportunities for safe evacuation. Therefore, reducing smoke production during combustion is of paramount importance. As shown in

Figure 4d, during cone calorimetry testing, the combustion initiation time of WPCSM was earlier than that of pure wood, leading to a slightly higher TSP accumulation in the first 200 s. However, after 200 s, the rate of TSP increase for WPCSM significantly diminished and consistently remained below that of pure wood. This phenomenon can be attributed to the multifaceted action mechanisms of the flame-retardant coating on WPCSM: firstly, the coating facilitates the rapid formation of a dense char layer when subjected to heat, effectively blocking the contact between the fuel and oxygen; secondly, the flame-retardant components within the coating mitigate incomplete combustion reactions, reducing the generation of smoke particulates; finally, the resultant char layer structure can adsorb some smoke particles, further diminishing smoke release. Experimental data indicate that the total smoke production from WPCSM throughout the entire combustion process was reduced by 25% compared to pure wood, providing solid evidence of its excellent smoke suppression performance.

As illustrated in

Figure 6a, the release of CO

2 showed a significant positive correlation with the heat release rate of the materials, consistent with fundamental theoretical expectations of combustion chemistry. During the initial phase of the combustion test, the CO

2 release from the pure wood samples exhibited a sharp increase, peaking at 0.114 g/s at 59 s, primarily due to the rapid oxidation combustion reactions occurring on the material’s surface. Subsequently, as a continuous dense char layer began to form during combustion, this char layer acted as an effective physical barrier, significantly obstructing the diffusion of external oxygen and heat, leading to a notable decline in CO

2 release. After combustion, the unburned core material of the pure wood samples re-contacted oxygen and underwent secondary combustion, resulting in a second CO

2 release peak of 0.21 g/s until the samples were completely consumed. Notably, the two CO

2 release peaks for WPCSM (0.106 g/s and 0.134 g/s, respectively) were significantly lower than those of the pure wood control group. This reduction may be due to the acidic catalysts within the flame-retardant system accelerating the dehydration and carbonization of cellulose during the initial stages, resulting in a complete and dense char layer that effectively diminishes CO

2 release. These findings provide important experimental insights for understanding the combustion behavior of flame-retardant wood composites.

In fire scenarios, the release of carbon monoxide (CO) during material combustion is a primary factor contributing to poisoning, loss of consciousness, and even death among individuals. Therefore, assessing the amount of CO released during the combustion process is of paramount importance for fire safety research. As illustrated in

Figure 6b, a comparative analysis of the carbon monoxide production rate (COP) between wood-polymer composites (WPCSM) and pure wood was conducted using cone calorimetry. The experimental results indicate that throughout the combustion process, the COP of WPCSM remained significantly lower than that of pure wood for the majority of the time, with the disparity increasing as combustion time extended. Pure wood reached its peak CO release (0.0045 g/s) at 548 s, while WPCSM achieved its peak CO release (0.0033 g/s) at 575 s, representing a 27% reduction in intensity. This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the multiple protective mechanisms of the flame-retardant coating on the surface of WPCSM: first, the coating facilitates the formation of a dense char layer, effectively suppressing the pyrolysis process of the material; second, the coating significantly enhances the structural integrity of the char layer at elevated temperatures, thereby reducing the release of flammable volatile compounds. Consequently, less wood is involved in the combustion process, leading to a reduced CO yield. This result corroborates the finding that wood is effectively protected by the flame-retardant coating. The research indicates that WPCSM possesses superior combustion safety compared to pure wood; its lower COP signifies a substantial reduction in the hazards posed by toxic smoke in real fire scenarios, thus allowing for valuable additional time for safe evacuation.

As shown by the mass loss curves in

Figure 6c, the combustion test results demonstrate that the mass of the pure wood samples decreased significantly from an initial weight of 53.9 g to 7.5 g over the course of 670 s of combustion, resulting in a total mass loss of 46.4 g (an 86.1% loss rate). In contrast, the mass of the WPCSM samples diminished from 48.8 g to 9.9 g, with a total mass loss of 38.9 g (a loss rate of 79.7%). Comparative analysis revealed that the mass loss rate for WPCSM (0.058 g/s) was significantly lower than that of pure wood (0.069 g/s). This difference can be primarily attributed to the synergistic protective effects of the composite flame-retardant coating on the surface of WPCSM, which promotes the formation of a dense, expanded char layer under high temperatures.

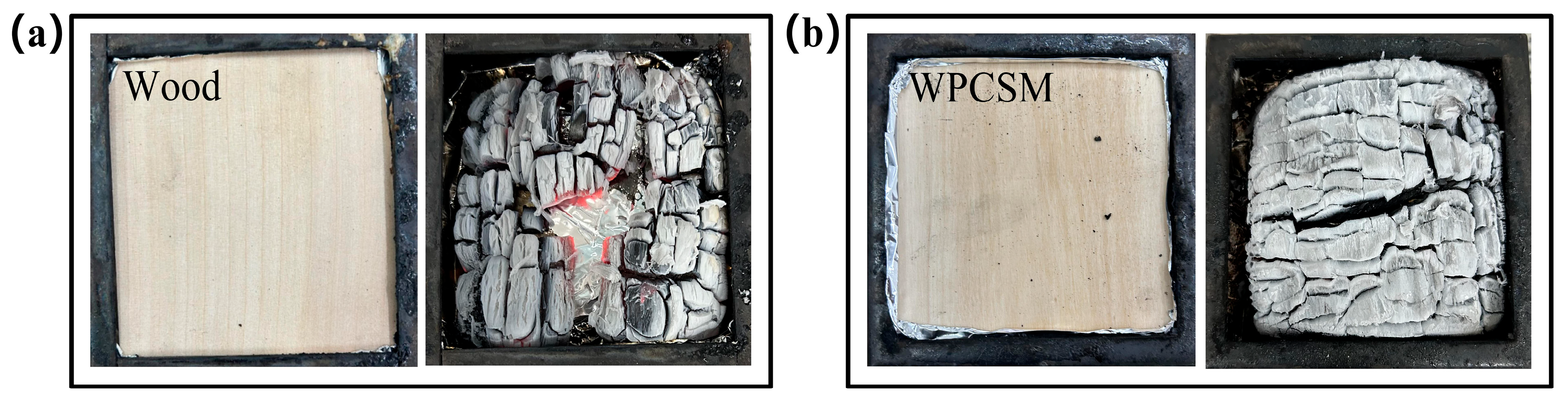

A comparison of digital photographs taken before and after combustion (

Figure 7a,b) reveals that although the surface of the WPCSM samples was covered by a flame-retardant coating comprising sodium phytate, chitosan-gelatin composite, sodium alginate, and sodium methyl silicate, the wood grain remained distinctly visible prior to combustion, showing no significant visual difference from the pure wood samples. However, the residual char morphology after combustion exhibited marked differences between the two. Pure wood surfaces exhibited numerous macroscopic cracks, a loose structure, and severe central cavitation. This morphology is consistent with its high mass loss rate of 86.1%. In contrast, the WPCSM samples showed only minor cracks and maintained considerable structural integrity, aligning with their lower mass loss (79.7%) and superior flame retardancy. This difference is attributed to the dense char layer formed by the composite coating, which effectively inhibited crack propagation and protected the internal substrate. The addition of sodium methyl silicate further enhanced the char’s thermal stability, enabling it to withstand prolonged combustion for 670 s. The synergistic effects of these factors result in WPCSM exhibiting a lower mass loss rate and a higher char yield, thereby providing robust evidence for the effectiveness of this composite flame-retardant system.

3.6. Flame Retardant Mechanism

Based on the results of cone calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis, and char characterization, the bio-based flame-retardant system developed in this study significantly enhances the fire resistance of wood through a multi-phase synergistic mechanism (

Figure 9). In terms of gas-phase flame retardancy, TG-FTIR analysis revealed notable release peaks for NH

3 (966 cm

−1) and H

2O (3500–3800 cm

−1) in the WPCSMH samples within the 300–400 °C range, corresponding to the decomposition processes of chitosan and gelatin. Additionally, the emergence of the characteristic peak of the PO· radical (1260 cm

−1) confirmed the quenching effect of phosphorus-containing radicals generated from the decomposition of sodium phytate on the combustion chain reaction. Collectively, these gas-phase products led to a reduction in the concentration of combustible gases, resulting in an increase in the Limiting Oxygen Index (LOI) from 22.0% to 34.0%.

Regarding condensed-phase flame retardancy, the char images indicate that the char produced after flame retardant treatment is denser, which is favorable for flame suppression. The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectrum reveals a characteristic peak for the P 2p orbital at 134.2 eV, confirming the formation of a C-O-P crosslinked structure. This phosphorus-carbon composite layer resulted in an increase in the char yield from 0.37% for pure wood to 3.54% for WPCSMH.

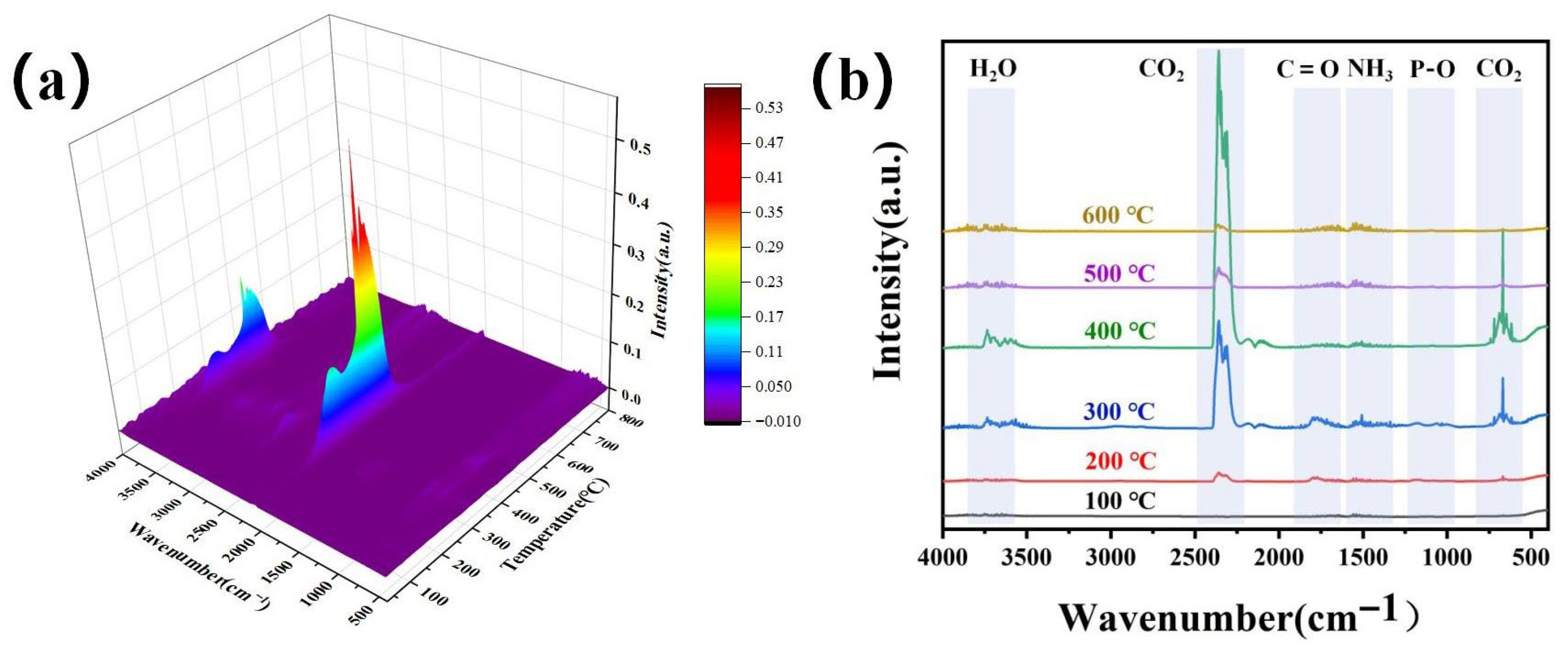

This study employs thermogravimetric analysis under air atmosphere to simulate the aerobic thermal oxidative degradation behavior of materials in actual fire conditions, which provides more valuable reference for assessing their real-world fire hazards. As illustrated in

Figure 10a,b, WPCSM begins to pyrolyze around 200 °C, primarily releasing CO

2 during this stage. The gas release significantly increases at 300 °C, with the maximum release observed at 400 °C. By approximately 600 °C, CO

2 release is complete. The peaks around 2358 cm

−1 and 669 cm

−1 correspond mainly to CO

2, while the peak at 3502 cm

−1 is attributed to H

2O, originating from both the flame-retardant coating and inherent moisture in the wood. The peak at 1170 cm

−1 corresponds to P-O bonds, resulting from the cleavage of phosphate groups during the pyrolysis of sodium phytate, while the peak at around 1496 cm

−1 is associated with NH

3. This non-combustible gas effectively dilutes the oxygen concentration in the combustion zone, achieving flame suppression. In terms of gas-phase flame retardancy, the TG-IR data indicate that the P-O peak, primarily from the cleavage of phosphate groups in phytate, appears predominantly between 200–300 °C. The coating decomposes to release P-O, which intercepts reactive radicals (·H, ·OH), thereby inhibiting the chain reaction of combustion [

30].

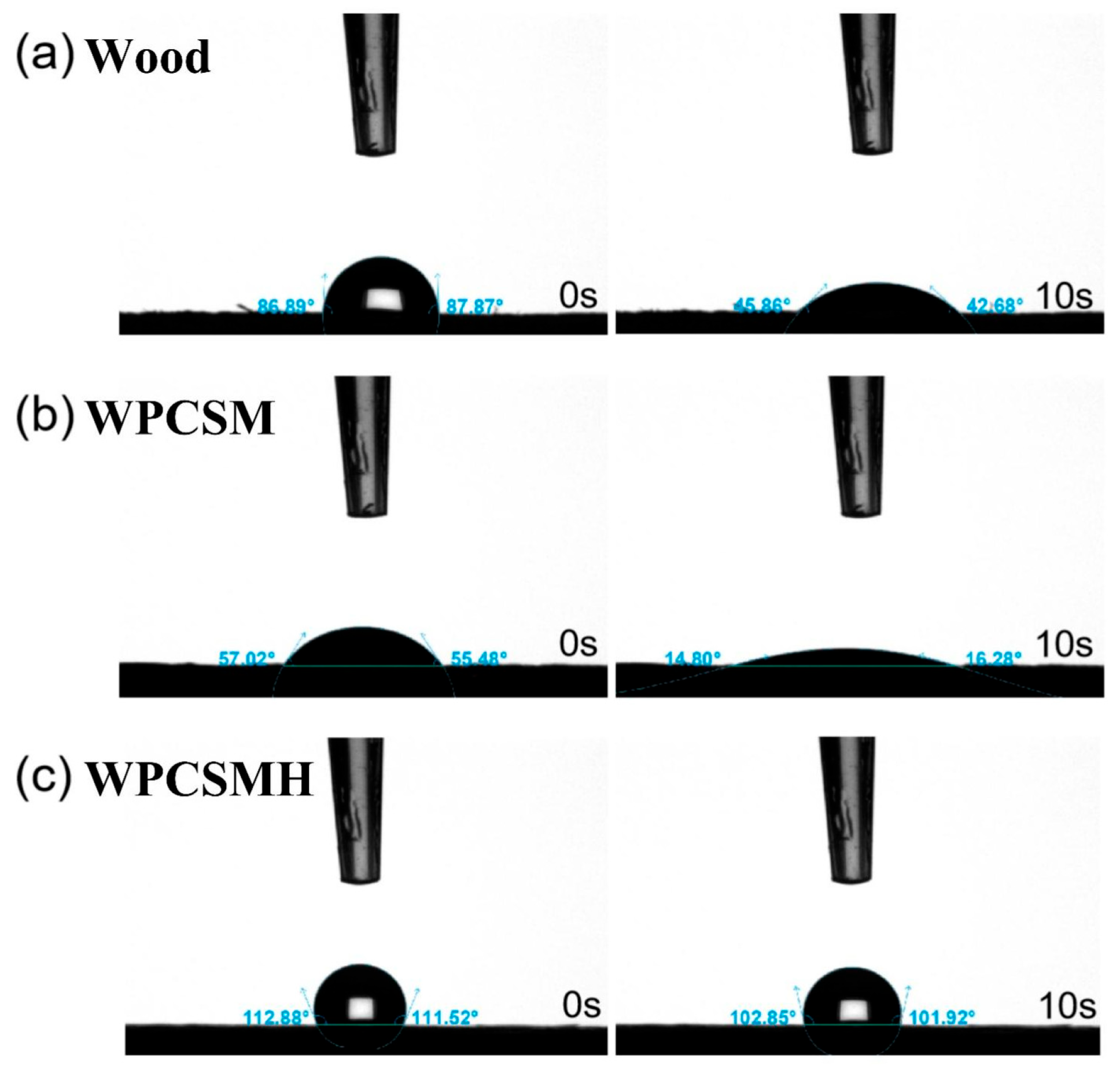

Despite the increased initial contact angle (111°) of WPCSMH after sodium methyl silicate treatment, its flame retardancy (LOI: 34.0%) was comparable to that of WPCSM (LOI: 32.1%). This result demonstrated that hydrophobicity is a surface property, whereas flame retardancy is governed by the intrinsic sodium phytate-chitosan-gelatin system. This strategy of functional separation provides a novel perspective for the development of multifunctional wood composites.