“I Am Less Stressed, More Productive”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stress-Management Interventions and Their Impact on Employee Well-Being and Performance at Saudi Universities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Hypothesis Development

2.2.1. Mindfulness and Perceived Stress (H1)

2.2.2. Time Management and Job Performance (H2)

2.2.3. Time Management and Coworker Support (H3)

2.2.4. Coworker Support and Job Performance (H4)

2.2.5. Time Management and Schedule Control (H5)

2.2.6. Job Performance and Work–Life Balance (H6)

2.2.7. The Mediating Role of Job Performance (H7)

2.3. Conceptual Framework

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants and Sampling

3.2. Tools and Measurements

3.3. Collecting Qualitative Data

3.4. Quantitative Assessment

- Mindfulness → stress (H1);

- Time management → job performance (H2);

- Time management → coworker support (H3);

- Coworker support → job performance (H4);

- Time management → control of the schedule (H5);

- Job performance → balance between work and life (H6);

- Time management → work–life balance (indirectly through job performance; H7).

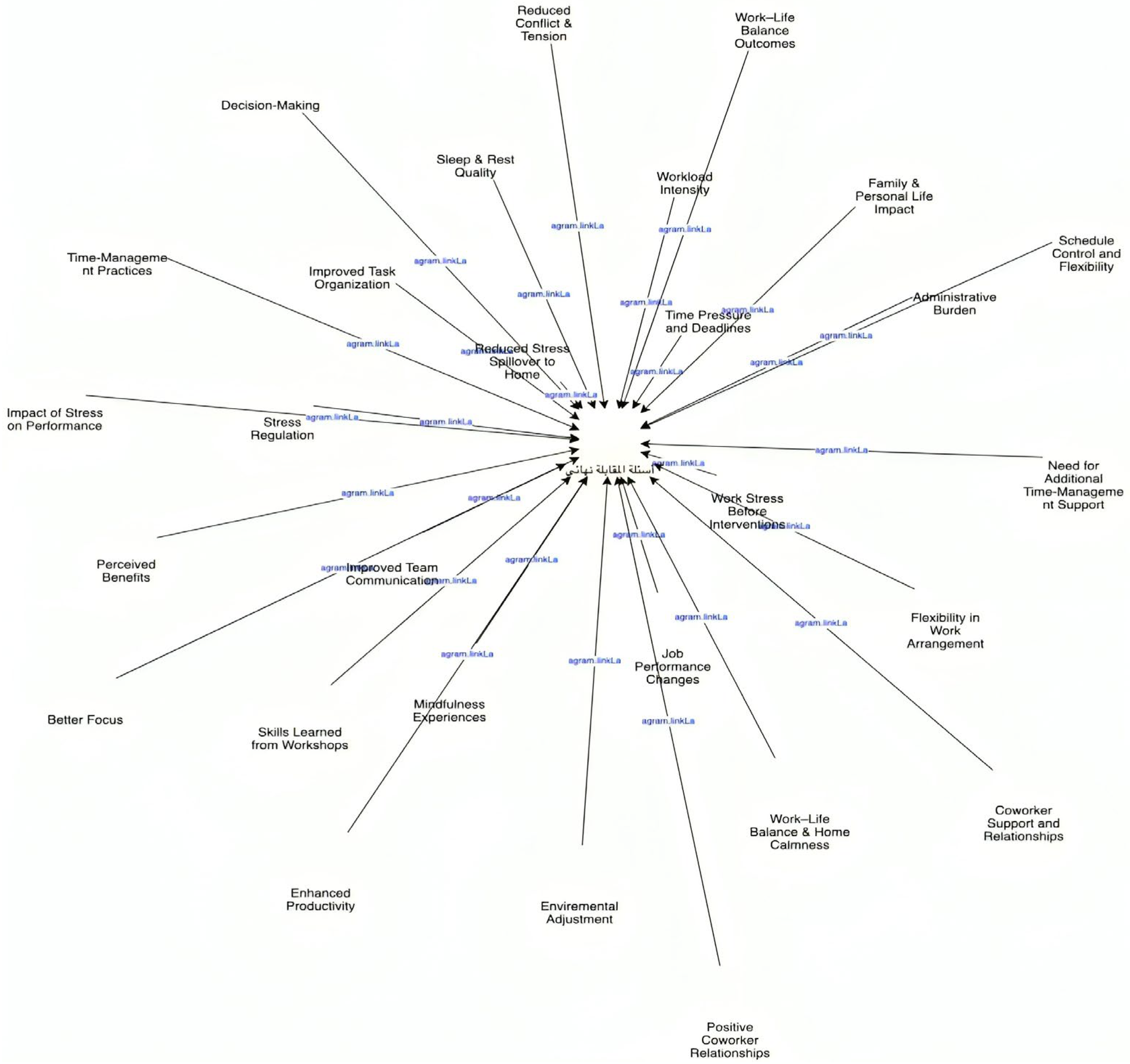

3.5. Qualitative Study

3.6. Ethical Considerations

3.7. Methodological Rigor

4. Results

4.1. Quantitative Results

4.1.1. Reliability and Descriptive Analysis

4.1.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

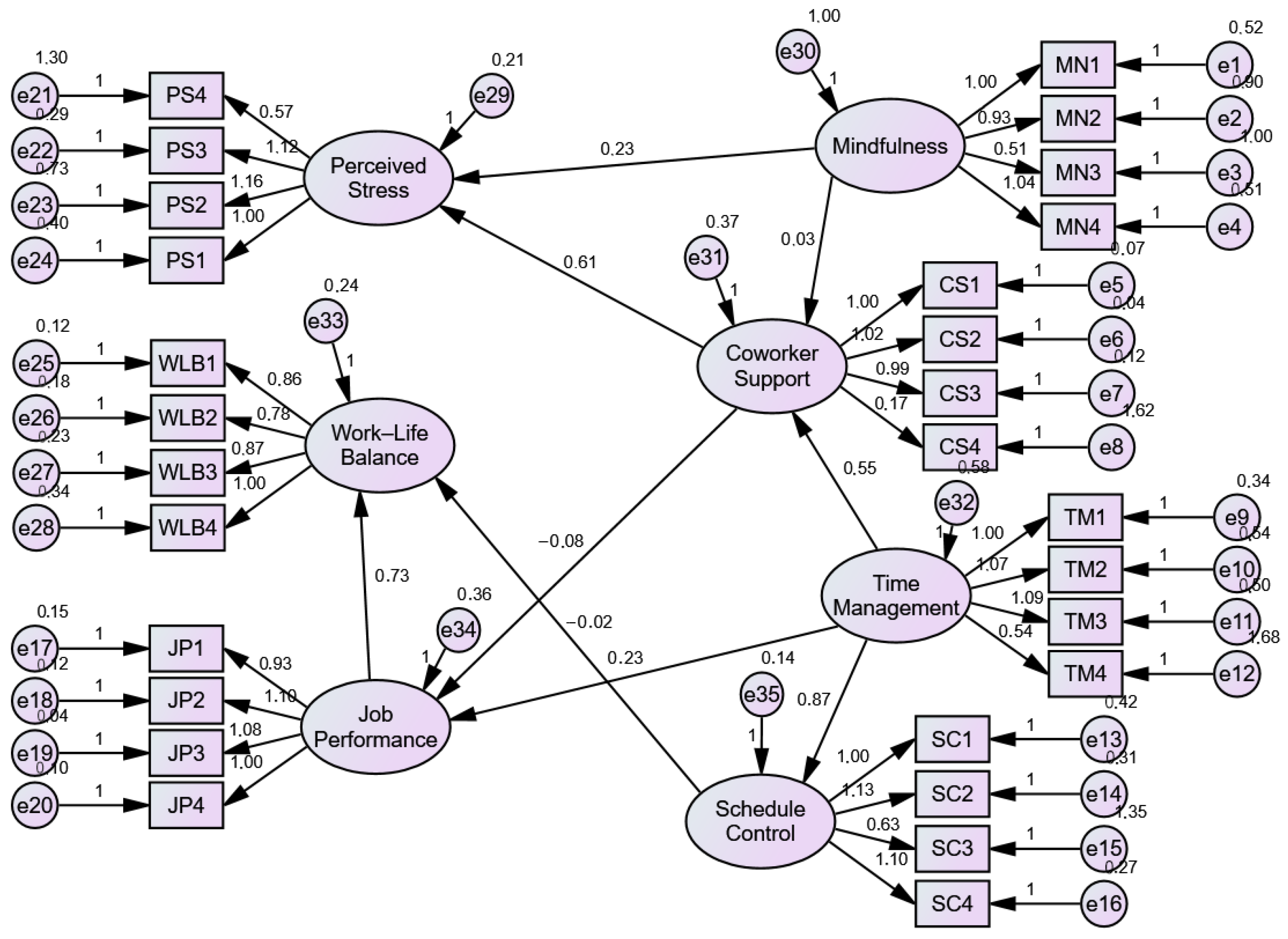

4.1.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

- First CFA Model

- Respecifying the Model

- Changes at the item level: Indicators that showed low or unstable factor loadings were taken out. In particular, TM4 (time management), CS4 (coworker support), and PS4 (perceived stress) were not included since their loadings were low in the EFA and first CFA. This stage adhered to psychometric best practices, which advocate for the elimination of items demonstrating cross-loading tendencies or inadequate communality (Marsh, 1996; Byrne, 2016) [40,45].

- Model simplification and correlated residuals: The measurement structure was simplified by keeping only the most representative indicators for each construct (two to three for each latent factor). Limited within-construct residual covariances were liberated due to theoretical and linguistic similarities among items; for instance, semantically overlapping statements within the same scale were utilized to accommodate modest method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003) [39]. No cross-construct residual correlations were established, ensuring rigorous discriminant validity.

- Mindfulness (MN1, MN2);

- Time management (TM2, TM3);

- Control of the schedule (SC1, SC2, SC4);

- Perceived stress (PS1, PS2);

- Coworker support (CS1, CS2, CS3);

- Job performance (JP3, JP4);

- Work–life balance (WLB1, WLB2, WLB3).

- Last Measurement Model

- Control of the schedule (β = 0.885, p < 0.001);

- Coworker support (β = 0.556, p < 0.001);

- Job performance (β = 0.239, p = 0.041).

4.2. Qualitative Results

4.2.1. Mindfulness and Stress Perception (H1)

4.2.2. Time Management and Job Performance (H2)

4.2.3. Time Management and Coworker Support (H3)

4.2.4. Coworker Support and Job Performance (H4)

4.2.5. Time Management and Schedule Control (H5)

4.2.6. Job Performance and Work–Life Balance (H6)

4.2.7. Time Management, Job Performance, and Work–Life Balance (H7)

5. Discussion

5.1. Mindfulness and Stress Reduction (H1)

5.2. Time Management as a Primary Factor (H2, H3, H5, H7)

5.3. Coworker Support and Job Performance (H4)

5.4. Job Performance and Work–Life Balance (H6)

5.5. Model Refinement and Exclusion of Non-Significant Paths

5.6. Synthesis and Theoretical Contributions

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Contributions

6.2. Contributions to Practice

6.3. Limitations

6.4. Directions for Future Research

6.5. Overall Consequences

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization; International Labour Organization. Mental Health at Work: Policy Brief. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240053052 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Yousef, A.H. The impact of workplace social support on job performance: The mediating role of organizational identification–A field study on employees at Beni Suef University. Alex. Univ. J. Adm. Sci. 2024, 61, 257–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, T.J.; Tayeh, B.K.A. The Impact of Job Design on Work-Life Balance in the Arab Islamic International Bank. Hussein Bin Talal Univ. J. Res. 2024. Available online: https://journal.ahu.edu.jo/Admin_Site/Articles/Images/24e77194-efe3-494a-ba07-94870868802f.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Nachreiner, F.; Schaufeli, W. The JD–R model. J. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 86, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R.S.; Folkman, S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping; Springer Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; Available online: https://books.google.com.sa/books?id=i-ySQQuUpr8C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources model: State of the art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karasek, R.; Brisson, C.; Kawakami, N.; Houtman, I.; Bongers, P.; Amick, B. The Job Content Questionnaire. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 1998, 3, 322–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, K.W.; Ryan, R.M. The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003, 84, 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. A global measure of perceived stress (PSS). J. Health Soc. Behav. 1983, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macan, T.H.; Shahani, C.; Dipboye, R.L.; Phillips, A.P. College students’ time management (TMBS). J. Educ. Psychol. 1990, 82, 760–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macan, T.H. Time management: A test of a process model. J. Appl. Psychol. 1994, 79, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of family-supportive supervisor behaviors and schedule control. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.J.; Anderson, S.E. Job satisfaction/organizational commitment and in-role/extra-role behaviors. J. Appl. Psychol. 1991, 76, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, P.; Timms, C.; O’Driscoll, M.; Kalliath, T.; Siu, O.-L.; Sit, C.; Lo, D. Work–Life Balance: A Longitudinal Evaluation of a New Measure. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 2724–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, G. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.J. Scaling an Islamic work ethic. J. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 128, 575–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoury, B.; Sharma, M.; Rush, S.E.; Fournier, C. MBSR for healthy individuals: Meta-analysis. J. Psychosom. Res. 2015, 78, 519–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonderlin, R.; Biermann, M.; Bohus, M.; Lyssenko, L. Mindfulness-based programs in the workplace: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness 2020, 11, 1579–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülsheger, U.R.; Alberts, H.J.E.M.; Feinholdt, A.; Lang, J.W.B. Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J. Appl. Psychol. 2013, 98, 310–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, A.M.; Hakami, A.; AlHadi, A.; Al-Maflehi, N.; Aljawadi, M.H.; Alotaibi, R.M.; Alzahrani, M.M.; Alammari, S.A.; Batais, M.A.; Almigbal, T.H. The effectiveness of mindfulness training in improving medical students’ stress, depression, and anxiety. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeon, B.; Faber, A.; Panaccio, A. Does time management work? A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0245066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, W.E. Time use efficiency and the five-factor model of personality. Education 2002, 122, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Peeters, M.C.W.; Rutte, C.G. Time management behavior as a moderator for the job demand–control interaction. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2005, 10, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaburu, D.S.; Harrison, D.A. Do peers make the place? Conceptual synthesis and meta-analysis of coworker influence on perceptions, attitudes, OCBs, and performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2008, 93, 1082–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, A.; Stock, A.; Oberst, V. Time management training and perceived control of time at work. J. Psychol. 2010, 144, 429–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aeon, B.; Aguinis, H. It’s about time: New perspectives and insights on time management. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2017, 31, 309–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claessens, B.J.; van Eerde, W.; Rutte, C.G.; Roe, R.A. A review of the time management literature. Pers. Rev. 2007, 36, 255–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018; Available online: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/designing-and-conducting-mixed-methods-research/book241842 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2015-56948-000 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, G.; Bunce, A.; Johnson, L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 2006, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fetters, M.D.; Curry, L.A.; Creswell, J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013, 48, 2134–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 10th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- West, S.G.; Finch, J.F.; Curran, P.J. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications; Hoyle, R.H., Ed.; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1995; pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, C.L.; Quick, J.C. The Handbook of Stress and Health: A Guide to Research and Practice; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W. Positive and negative global self-esteem: A substantively meaningful distinction or artifactors? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 810–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.; Rindfleisch, A.; Burroughs, J.E. Do reverse-worded items confound measures in cross-cultural consumer research? The case of the material values scale. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Bearden, W.O.; Sharma, S. Scaling Procedures: Issues and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.M. Psychometric analysis of the Ten-Item Perceived Stress Scale. Psychol. Assess. 2015, 27, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B.M. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 3rd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, H.G. Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry 2012, 2012, 278730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, P.; Lim, H.J. Mindfulness at work: Effects of brief mindfulness interventions on well-being and performance. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2015, 20, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donald, J.N.; Sahdra, B.K.; Van Zanden, B.; Duineveld, J.J.; Atkins, P.W.B.; Marshall, S.L.; Ciarrochi, J. Does your mindfulness benefit others? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the link between mindfulness and prosocial behaviour. Br. J. Psychol. 2019, 110, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, N.Y.; Teo, F.J.J.; Ee, J.Z.Y.; Yau, C.E.; Thumboo, J.; Tan, H.K.; Ng, Q.X. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on the well-being of healthcare workers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gen. Psychiatry 2024, 37, e101115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, J. Effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions on burnout, resilience and sleep quality among nurses: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedi, A.; Sass, M. A meta-analytic review of the consequences of employee time management behaviors. J. Soc. Psychol. 2023, 163, 676–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of Resource Theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience. In The Oxford Handbook of Stress, Health, and Coping; Folkman, S., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 127–147. [Google Scholar]

- Demerouti, E.; Bakker, A.B.; Geurts, S.A.E. Towards a typology of work–home interaction. Community Work. Fam. 2004, 12, 285–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Russo, M.; Sune, A.; Ollier-Malaterre, A. Outcomes of work–life balance on job satisfaction, life satisfaction and mental health: A study across seven cultures. J. Vocat. Behav. 2014, 85, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, G.C.N.; Yip, T.; Zárate, M.A. On becoming multicultural in a monocultural research world. Am. Psychol. 2016, 71, 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, M.; Abbott, R.; Dunn, B.; Dickens, C.; Keil, T.; Henley, W.; Kuyken, W. Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2017, 55, 74–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padela, A.I.; Curlin, F.A. Religion and disparities: Considering the influences of Islam on the health of American Muslims. J. Relig. Health 2013, 52, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Construct | Items | Mean (Range) | SD (Range) | Skewness (Range) | Kurtosis (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness (MN1–MN4) | 4 | 3.04–3.75 | 1.13–1.34 | −0.849 to −0.012 | −1.014 to 0.248 |

| Time Management (TM1–TM4) | 4 | 3.20–3.96 | 0.97–1.37 | −1.113 to −0.234 | −1.166 to 1.565 |

| Schedule Control (SC1–SC4) | 4 | 2.97–3.88 | 1.00–1.27 | −0.964 to −0.121 | −0.997 to 0.885 |

| Stress Perception (PS1–PS4) | 4 | 3.33–3.91 | 0.97–1.21 | −1.205 to −0.425 | −0.687 to 1.941 |

| Coworker Support (CS1–CS4) | 4 | 2.94–4.18 | 0.79–1.28 | −1.279 to −0.059 | −1.103 to 3.208 |

| Job Performance (JP1–JP4) | 4 | 4.45–4.46 | 0.69–0.76 | −1.783 to −1.063 | 0.565 to 4.351 |

| Work–Life Balance (WLB1–WLB4) | 4 | 4.39–4.53 | 0.67–0.89 | −1.893 to −0.925 | −0.285 to 3.981 |

| Construct | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness | 4 | 0.785 |

| Time Management | 4 | 0.719 |

| Schedule Control | 4 | 0.776 |

| Stress Perception | 4 | 0.720 |

| Coworker Support | 4 | 0.701 |

| Job Performance | 4 | 0.938 |

| Work–Life Balance | 4 | 0.858 |

| Measure | N | Mean | SD | Min | Max | r | t(103) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSSB (Before) | 104 | 2.99 | 1.36 | 1 | 5 | |||

| PSSA (After) | 104 | 3.41 | 1.03 | 1 | 5 | 0.469 | –3.426 | 0.001 |

| Construct | KMO | Bartlett’s Test (p) | Variance Explained (%) | Strongest Loading | Weakest Loading |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness (MN1–MN4) | 0.743 | <0.001 | 61.4 | MN4 = 0.871 | MN3 = 0.587 |

| Time Management (TM1–TM4) | 0.707 | <0.001 | 58.0 | TM2 = 0.847 | TM4 = 0.472 |

| Schedule Control (SC1–SC4) | 0.760 | <0.001 | 63.2 | SC2 = 0.885 | SC3 = 0.530 |

| Perceived Stress (PS1–PS4) | 0.741 | <0.001 | 57.9 | PS3 = 0.849 | PS4 = 0.425 |

| Coworker Support (CS1–CS4) | 0.752 | <0.001 | 69.2 | CS2 = 0.965 | CS4 = 0.151 |

| Job Performance (JP1–JP4) | 0.851 | <0.001 | 84.4 | JP3 = 0.953 | JP1 = 0.881 |

| Work–Life Balance (WLB1–WLB4) | 0.823 | <0.001 | 71.3 | WLB1 = 0.866 | WLB4 = 0.822 |

| Fit Index | Recommended Threshold | Obtained Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (Chi-square) | Non-significant (sample-size-sensitive) | 812.599, df = 341, p < 0.001 | Significant |

| χ2/df | ≤3.0, acceptable | 2.383 | Acceptable |

| CFI | ≥0.90 (good); ≥0.95 (excellent) | 0.774 | Poor fit |

| TLI | ≥0.90 | 0.749 | Poor fit |

| IFI | ≥0.90 | 0.778 | Poor fit |

| GFI | ≥0.90 | 0.633 | Weak fit |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | ≤0.08, acceptable; ≤0.05, excellent | 0.116 (0.106–0.126) | Poor fit |

| PCLOSE | >0.05 | 0.000 | Poor fit |

| Fit Index | Recommended Threshold | Obtained Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 (Chi-square) | Non-significant (sample-size-sensitive) | 131.866, df = 100, p = 0.018 | Significant (common with N ≈ 100) |

| χ2/df | ≤3.00, acceptable | 1.319 | Acceptable |

| CFI | ≥0.95, good (≥0.90, adequate) | 0.972 | Good fit |

| TLI | ≥0.95, good (≥0.90, adequate) | 0.962 | Good fit |

| IFI | ≥0.95, good (≥0.90, adequate) | 0.973 | Good fit |

| NFI | ≥0.90 | 0.896 | Borderline/adequate |

| GFI | ≥0.90 (size-sensitive) | 0.883 | Slightly below |

| RMSEA (90% CI) | ≤0.06, good (≤0.08, acceptable) | 0.056 (0.024–0.080) | Good/near-close fit |

| PCLOSE | >0.05 supports close fit | 0.348 | Supports near-close fit |

| RMR | ≤0.08, acceptable | 0.054 | Acceptable |

| PNFI | Higher is better (parsimony) | 0.658 | Parsimonious |

| PCFI | Higher is better (parsimony) | 0.714 | Parsimonious |

| AIC | Lower (comparative) | 237.866 | For model comparison |

| ECVI | Lower (comparative) | 2.309 | For model comparison |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Abbes, I.; Amari, F. “I Am Less Stressed, More Productive”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stress-Management Interventions and Their Impact on Employee Well-Being and Performance at Saudi Universities. Sustainability 2026, 18, 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010518

Abbes I, Amari F. “I Am Less Stressed, More Productive”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stress-Management Interventions and Their Impact on Employee Well-Being and Performance at Saudi Universities. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010518

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbbes, Ikram, and Farouk Amari. 2026. "“I Am Less Stressed, More Productive”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stress-Management Interventions and Their Impact on Employee Well-Being and Performance at Saudi Universities" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010518

APA StyleAbbes, I., & Amari, F. (2026). “I Am Less Stressed, More Productive”: A Mixed-Methods Analysis of Stress-Management Interventions and Their Impact on Employee Well-Being and Performance at Saudi Universities. Sustainability, 18(1), 518. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010518