Comparing Driver Behaviour with Measured Speed—An Innovative Approach to Designing Transition Zones for Smart Cities

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ➀

- Is there a consistency in declared behaviours in the analysed transition zones in the respective age groups?

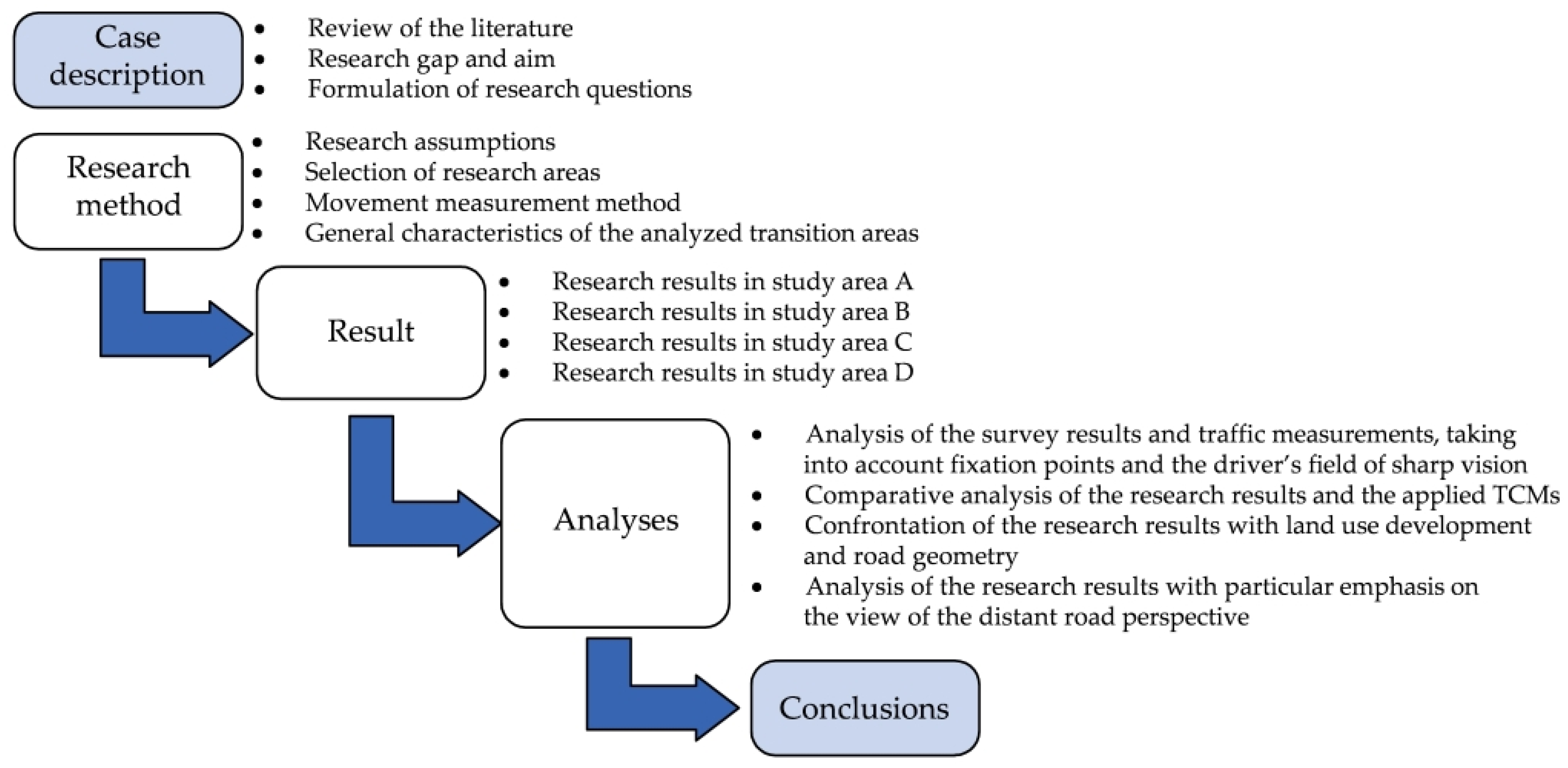

- ➁

- Were the applied TCMs effective in lowering the speeds to the transition-zone speed limit in the analysed transition zones?

- ➂

- Is there a consistency between the self-declared behaviours and the final speed past the TCM in the analysed transition zones?

- ➃

- Which surrounding features turned out to be useful and facilitated attaining the target speed past the TCM in the analysed transition zones?

2. Research Assumptions and Method

2.1. Research Assumptions

- -

- TCM type: chicane, central island, refuge island, or DSFS;

- -

- Surrounding features: forest, fields, footpath(s), road or street cross-section, culvert or roadside ditch guardrails, bridge with parapets, etc.;

- -

- View of the road far ahead, including a road junction, close or distant buildings, no buildings in sight, refuge island, etc.;

- -

- Road alignment, both vertical (convex or concave arc) and horizontal (straight line, right-hand or left-hand curve).

- -

- Chicanes on the entry lane (Figure 3a,b—2 m or 2.2 m wide), hereinafter referred to as chicane;

- -

- Chicanes with a central island separating the two traffic directions (Figure 3c,d—2 or 3 m wide), hereinafter referred to as central island;

- -

- Chicanes with a pedestrian crossing (Figure 3e—2.5 m wide), also hereinafter referred to as chicane;

- -

- Pedestrian refuge island (Figure 3f—2 m wide), hereinafter referred to as refuge island.

2.2. Transition-Zone Selection Process

- -

- The applied traffic calming measures (TCMs);

- -

- Road surroundings and cross-section;

- -

- The view of the road ahead beyond the respective TCM, which included features within the driver’s field of sharp vision, such as a pedestrian refuge, an intersection, a bridge with railings, a culvert with road barriers, forested areas, and agricultural land;

- -

- Road profile (convex or concave curves) and horizontal geometry (straight sections, left-hand curves, or right-hand curves).

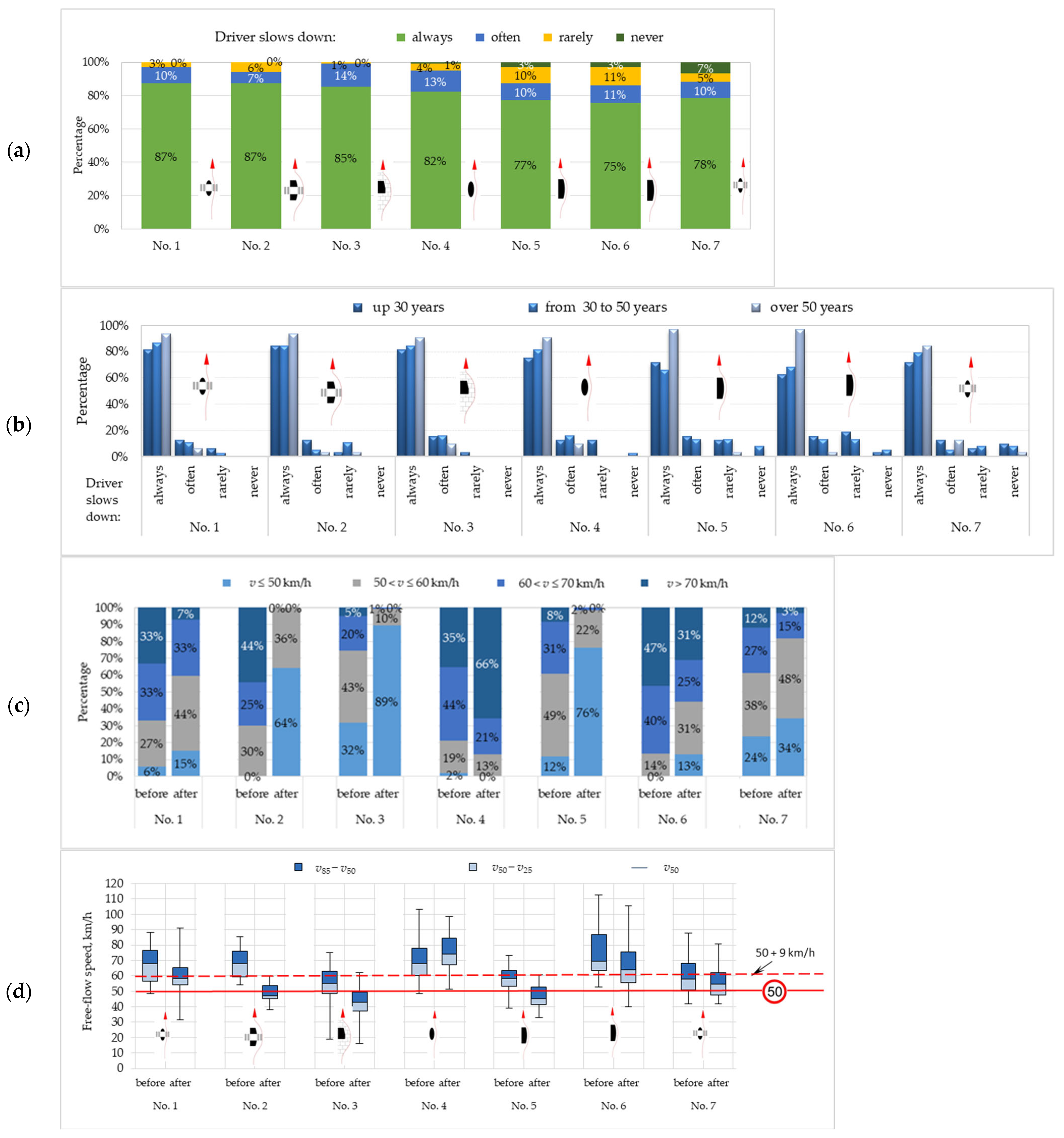

2.3. Self-Declaration Survey

- A—slow down almost always (seven transition zones—from No. 1 to No. 7);

- B—often slow down (five transition zones—from No. 8 to No. 12);

- C—rarely slow down (six transition zones—from No. 13 to 18);

- D—never slow down (eight transition zones—from No. 19 to No. 26).

2.4. Traffic Detection Method

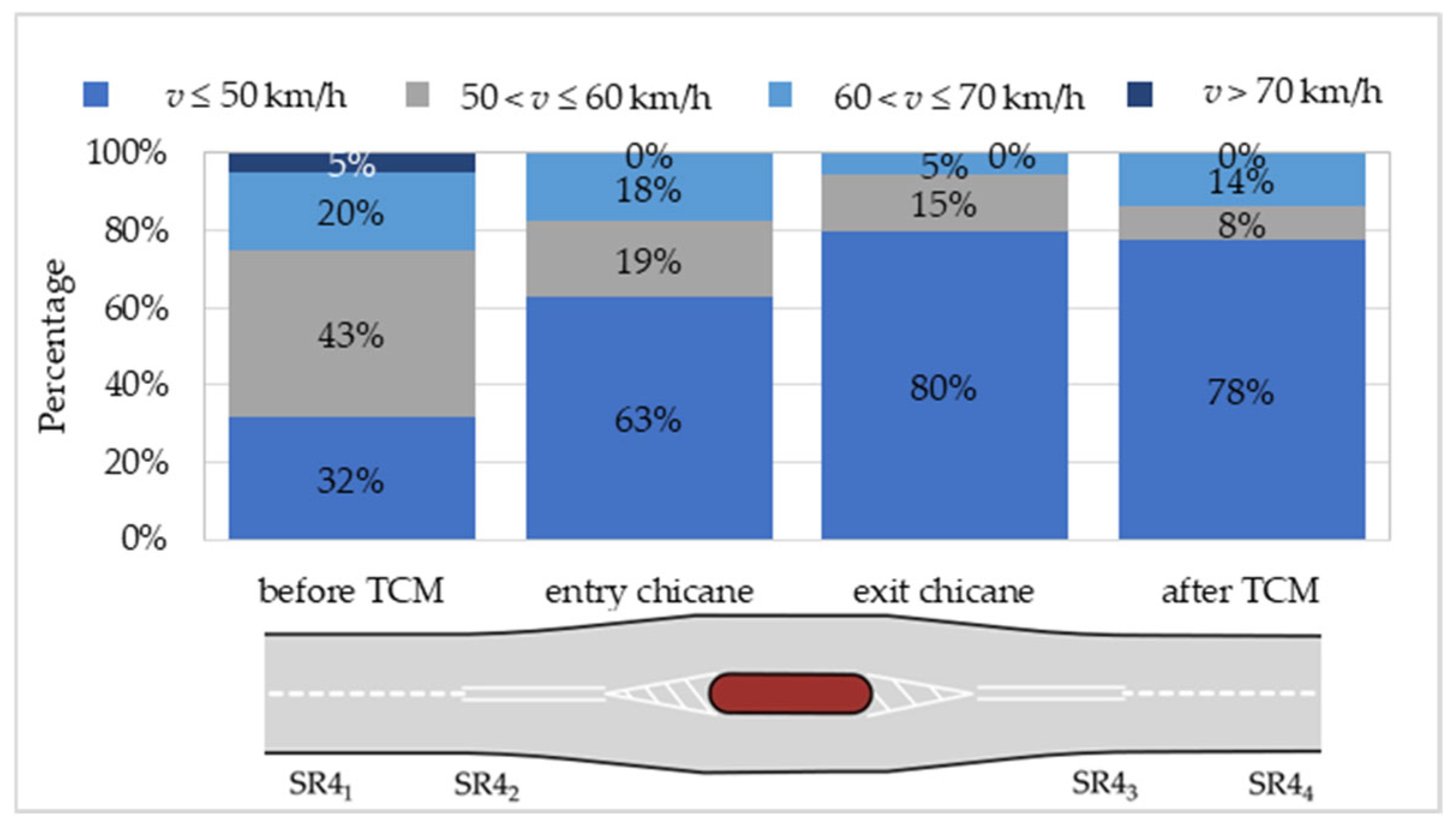

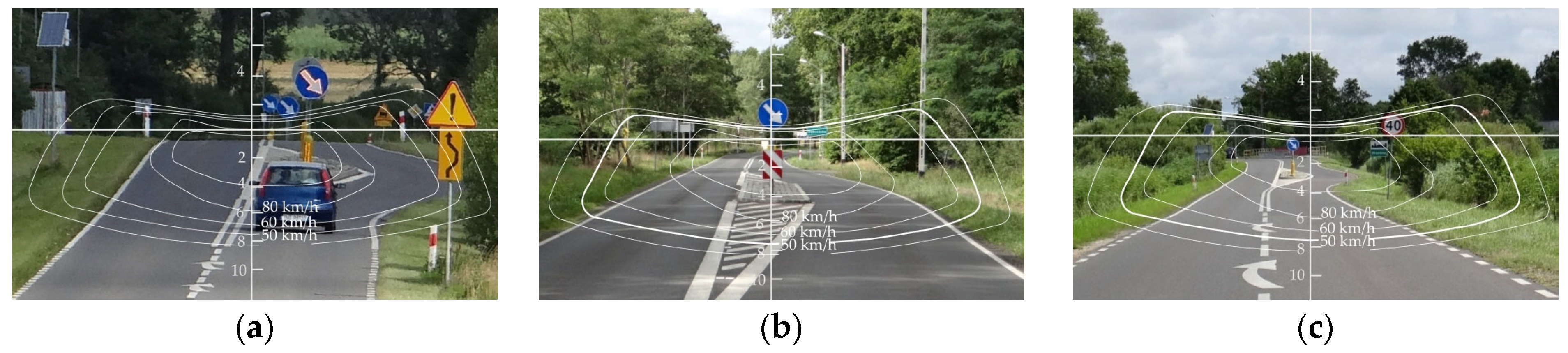

- -

- SR41—15–20 m upstream of the beginning of the double solid line, depending on local constraints;

- -

- SR42—at the beginning of the double solid line, immediately before the taper of the hatched road markings leading to the island;

- -

- SR43—downstream of the taper of the hatched road markings, behind the island, at the end of the double solid line;

- -

- SR44—15–20 m downstream of the end of the double solid line, depending on local constraints.

2.5. The ‘Before’ and ‘After’ Accident Rates

2.6. Method Applied to Compare the Questionnaire Responses and Vehicle Speeds Measured Before and After TCM

3. Study Areas

4. Results

4.1. Results in Study Area A

- -

- No. 2—chicane with a pedestrian crossing (2.5 m wide island) with buildings in close vicinity;

- -

- No. 3—chicane (2 m wide island) with a change in surface texture to stone block paving;

- -

- No. 5—chicane (2 m wide island), located before a very curvy street section, enhanced by culvert guardrails in the driver’s central vision area.

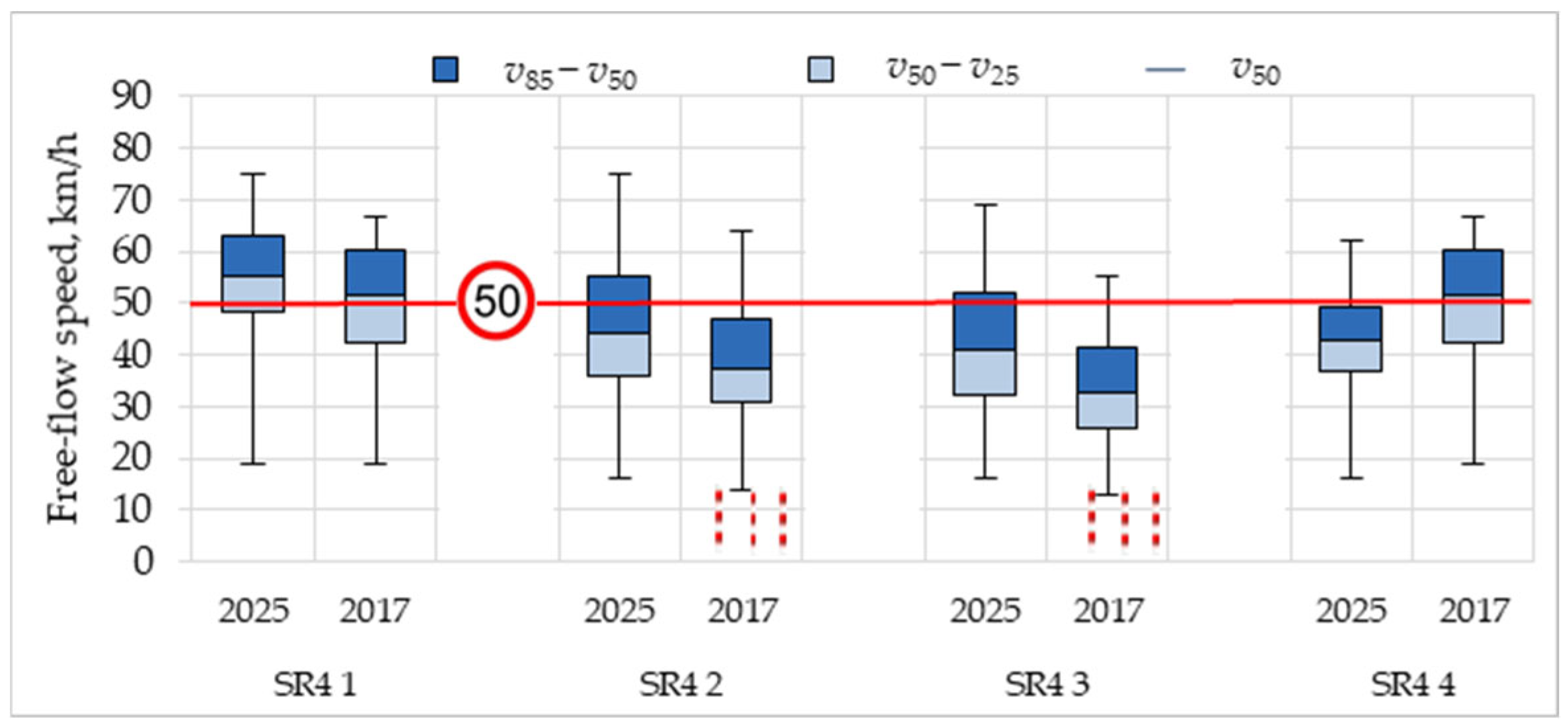

4.2. Results in Study Area B

4.3. Results in Study Area C

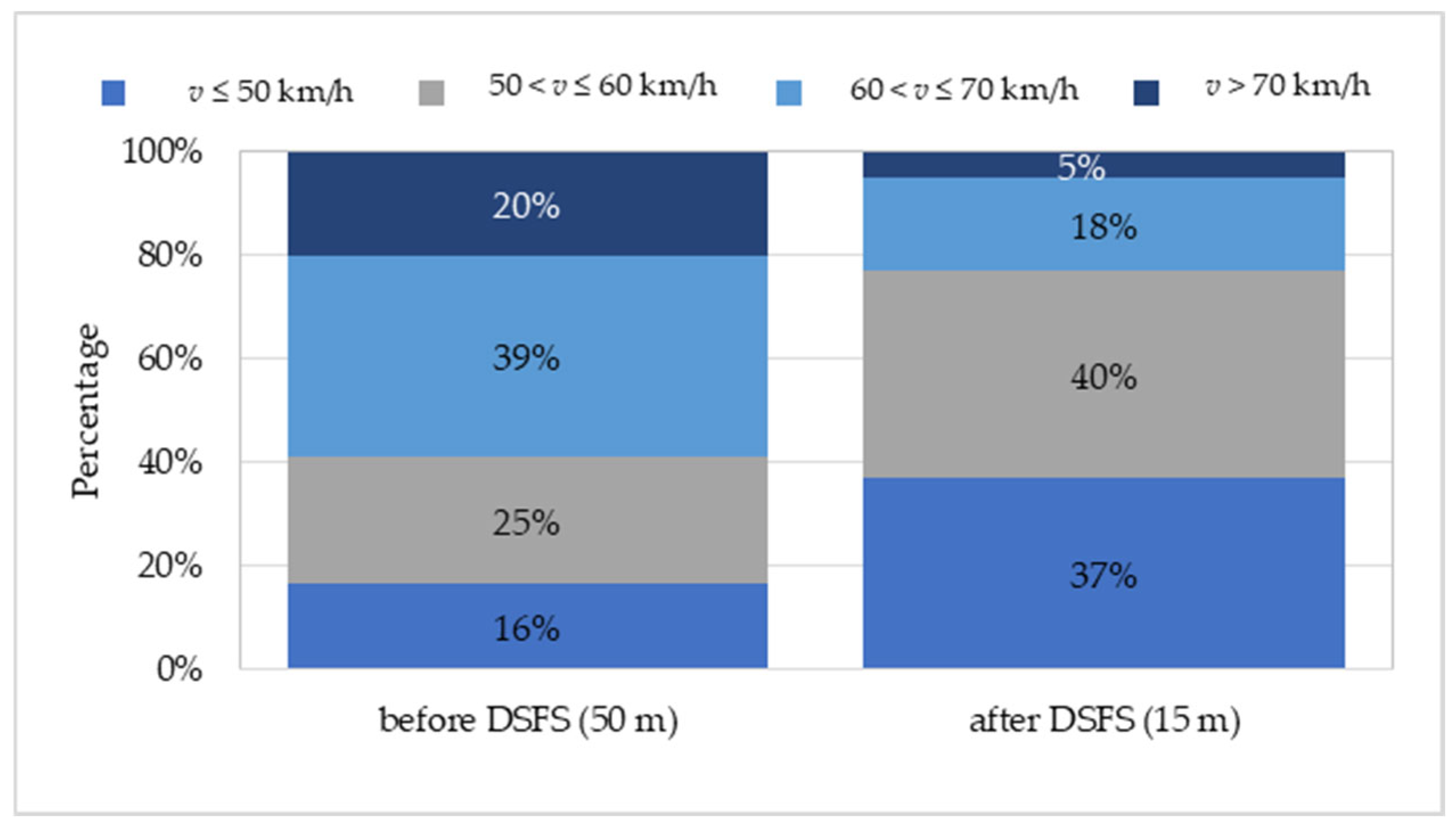

4.4. Results in Study Area D

5. Discussion

5.1. Correlation of the Survey Responses and the Traffic Survey Speed Data

5.2. Comparison of the Survey Responses with the Speed Survey Data, Taking into Account Driver Fixation Points and Visual Attention Areas

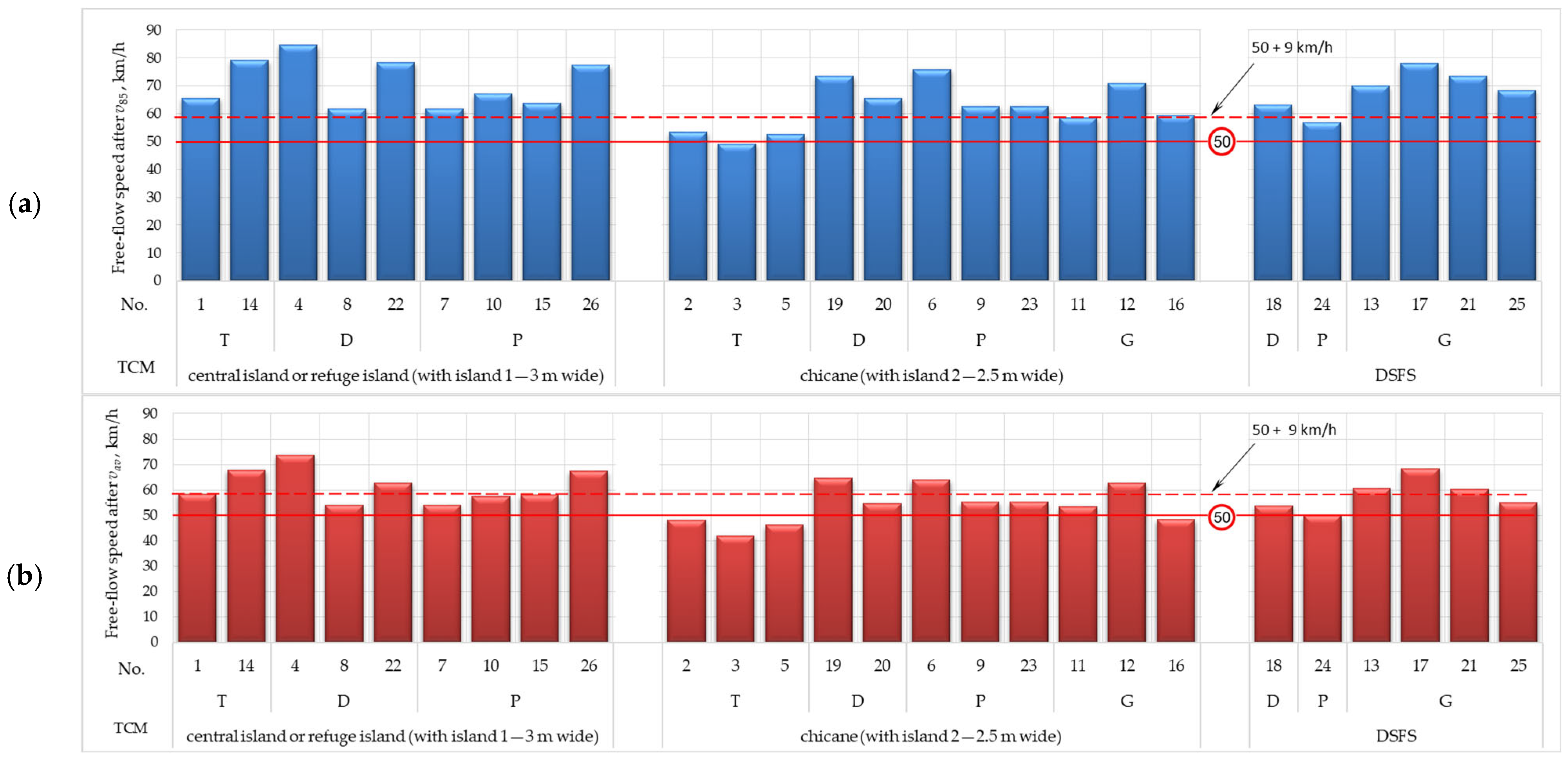

5.3. Analysis of Speed Data Depending on TCM Type

- -

- Transition zone No. 2, including a 2.5 m wide chicane with a pedestrian crossing before a bridge, and with buildings in close vicinity;

- -

- Transition zone No. 3—2 m wide chicane with pavement change from asphalt to cobblestone;

- -

- Transition zone No. 5, including a 2 m wide chicane before a culvert lined with visible guardrails and a very curvy road section past the chicane.

5.4. Proposed Sequence of Analyses in the Transition-Zone Design Process

6. Conclusions

6.1. Limitations

6.2. Summary

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| TCM | Traffic calming measure |

| DSFS | Dynamic speed feedback sign |

| B-33 | Speed limit sign of 30 km/h, in accordance with the Polish Highway Code |

| D-42 | Sign—built-up area limit sign, as per the Polish Highway Code |

| E-17 | Sign—town sign indicating the boundary of a town or village crossed by the road |

Appendix A

| Equation (A1) 1 | Equation (A2) 2 | Equation (A3) 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before TCM | After TCM | |||

| Transition zone No. 1 | λ = 0.66 | λ = 0.67 | λ = 2.20 | χ2 = 7.0 |

| Transition zone No. 2 | λ = 0.74 | λ = 0.59 | λ = 4.73 | χ2 = 77.2 |

| Transition zone No. 3 | λ = 1.13 | λ = 1.04 | λ = 4.62 | χ2 = 135.1 |

| Transition zone No. 4 | λ = 0.59 | λ = 0.35 | λ = 5.61 | χ2 = 12.7 |

| Transition zone No. 5 | λ = 0.52 | λ = 1.04 | λ = 3.41 | χ2 = 37.0 |

| Transition zone No. 6 | λ = 0.99 | λ = 0.71 | λ = 1.85 | χ2 = 6.3 |

| Transition zone No. 7 | λ = 0.58 | λ = 0.61 | λ = 5.96 | χ2 = 3.6 |

| Transition zone No. 8 | λ = 0.57 | λ = 0.61 | λ = 1.61 | χ2 = 3.8 |

| Transition zone No. 9 | λ = 0.54 | λ = 1.22 | λ = 6.07 | χ2 = 41.2 |

| Transition zone No. 10 | λ = 0.73 | λ = 0.51 | λ = 3.81 | χ2 = 57.6 |

| Transition zone No. 11 | λ = 0.56 | λ = 0.81 | λ = 5.82 | χ2 = 26.4 |

| Transition zone No. 12 | λ = 0.43 | λ = 0.33 | λ = 5.00 | χ2 = 4.4 |

| Transition zone No. 13 | λ = 0.32 | λ = 0.63 | λ = 2.83 | χ2 = 79.2 |

| Transition zone No. 14 | λ = 0.39 | λ = 0.99 | λ = 4.36 | χ2 = 9.2 |

| Transition zone No. 15 | λ = 0.33 | λ = 0.52 | λ = 5.23 | χ2 = 6.4 |

| Transition zone No. 16 | λ = 0.43 | λ = 0.51 | λ = 3.33 | χ2 = 25.7 |

| Transition zone No. 17 | λ = 1.34 | λ = 0.32 | λ = 3.50 | χ2 = 12.0 |

| Transition zone No. 18 | λ = 0.56 | λ = 0.74 | λ = 2.69 | χ2 = 79.5 |

| Transition zone No. 19 | λ = 0.57 | λ = 0.45 | λ = 4.85 | χ2 = 5.0 |

| Transition zone No. 20 | λ = 0.33 | λ = 0.52 | λ = 5.23 | χ2 = 6.4 |

| Transition zone No. 21 | λ = 0.40 | λ = 0.48 | λ = 5.36 | χ2 = 8.0 |

| Transition zone No. 22 | λ = 0.68 | λ = 1.03 | λ = 2.06 | χ2 = 16.1 |

| Transition zone No. 23 | λ = 0.54 | λ = 1.22 | λ = 3.57 | χ2 = 41.2 |

| Transition zone No. 24 | λ = 0.51 | λ = 0.86 | λ = 2.99 | χ2 = 336.1 |

| Transition zone No. 25 | λ = 0.54 | λ = 1.01 | λ = 1.41 | χ2 = 3.6 |

| Transition zone No. 26 | λ = 0.48 | λ = 0.82 | λ = 1.90 | χ2 = 15.4 |

Appendix B

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety, Raport WHO/EURO:2021-3162-42920-60721; Bloomberg Philanthropies: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, R.; Dumbaugh, E. The Built Environment and Traffic Safety. J. Plan. Lit. 2009, 23, 347–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dondi, G.; Simonea, A.; Lantieria, C.; Vignalia, V. Bike Lane design: The context sensitive approach. Procedia Eng. 2011, 21, 897–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucchi, A.; Sangiorgi, C.; Vignali, V. Traffic psychology and driver behavior. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 53, 973–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, L.M. Traffic calming definition. Inst. Transp. Eng. J. 1997, 67, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Roads Development Guide; South Ayrshire Council Strathclyde Roads: Ayrshire, UK, 1995.

- Urban Traffic Areas—Part 7—Speed Reducers; Vejdirektoratet-Vejregeludvalget: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1991.

- Forbes, G. NCHRP Synthesis 412: Speed Reduction Techniques for Rural High-to-Low Speed Transitions; Transportation Research Board of the National Academies: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, G.; Gardner, T.; McGee, H.; Srinivasan, R. Methods and Practices for Setting Speed Limits: An Informational Report. FHWA-SA-12-004; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Design Guidance for High-Speed to Low-Speed Transition Zones for Rural Highways NCHRP Report 737; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Transition Zone Design—Final Report, Research Report KTC-13-14/SPR431-12-1F; Kentucky Transportation Center: Lexington, KY, USA, 2013.

- WR-D-22-5 Wytyczne Projektowania Odcinków Dróg Zamiejskich. Część 5: Uspokajanie Ruchu na Drogach Zamiejskich i ich Powiązaniu z Ulicami; Minister Infrastruktury: Warszawa, Poland, 2023. (In Polish)

- Künzler, P.; Dietiker, J.; Steiner, R. Nachhaltige Gestaltung von Verkehrsräumen im Siedlungsbereich, Grundlagen für Planung, Bau und Reparatur von Verkehrsräumen; Bundesamt für Umwelt: Bern, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Deng, W.; Zhanh, H.; Wang, Z. Identification and analysis of transitional zone patterns along urban-rural-natural landscape gradients: An application to China’s southwest mountains. Land Use Policy 2023, 129, 106625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, D.K.; Bauer, K.M.; Torbic, D.J.; Kinzel, C.S.; Frazier, R.J. Treatment effects and design guidance for high- to low-speed transition zones for rural highways. Transp. Res. Rec. 2013, 2348, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wytyczne Zarządzania Prędkością na Drogach Samorządowych, pod Red; Stanisława Gacy, Politechnika Krakowska, Politechnika Gdańska, Fundacja Rozwoju Inżynierii Lądowej: Kraków/Gdańsk, Poland, 2016. (In Polish)

- Wirksamkeit Geschwindigkeitsdämpfender Maßnahmen Außerorts; Hessisches Landesamt für Straßen- und Verkehrswesen: Hessen, Germany, 1997.

- Balta, S.; Atik, M. Rural planning guidelines for urban-rural transition zones as a tool for the protection of rural landscape characters and retaining urban sprawl. Antalya Case Mediterr. Land Use Policy 2022, 119, 106144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliendo, C.; De Guglielmo, M.L. Road Transition Zones between the Rural and Urban Environment: Evaluation of Speed and Traffic Performance Using a Microsimulation Approach. J. Transp. Eng. 2013, 139, 295–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radarowe Wyświetlacze Prędkości. Available online: https://systemy-informacyjne.pl/oferta/kategoria/radarowe-wyswietlacze-predkosci/ (accessed on 5 September 2025). (In Polish).

- Sayer, I.A.; Parry, D.I.; Barker, J.K. Traffic Calming—An Assessment of Selected On-Road Chicane Schemes; TRL Report 313; Transport Research Laboratory: Crowthorne, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Inman, V.W.; Balk, S.A.; Perez, W.P. Traffic Control Device Conspicuity, Final Report. 10/1/2008–9/30/2011; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sayer, I.A.; Parry, D.I. Speed Control Using Chicanes—A Trial at TRL. TRL Project Report PR 102; Transport Research Laboratory: Crowthorne, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lantieri, C.; Lamperti, R.; Simone, A.; Costa, M.; Vignali, V.; Sangiorgi, C.; Dondi, G. Gateway design assessment in the transition from high to low speed areas. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 34, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirdavani, A.; Sadeqi Bajestani, M.; Mantels, M.; Spooren, T. A Driving Simulator-Based Assessment of Traffic Calming Measures at High-to-Low Speed Transition Zones. Smart Cities 2025, 8, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgol, K.; Gunay, B.; Aydin, M.M. Geometric optimisation of chicanes using driving simulator trajectory data. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Transp. 2022, 175, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, S.; Sołowczuk, A. Wpływ na prędkość zagospodarowania otoczenia strefy przejściowej dróg wojewódzkich przy wjeździe do małych miejscowości. In Perspektywy Rozwoju w Naukach Inżynieryjno-Technicznych—Trendy, Innowacje i Wyzwania; Wydawnictwo Naukowe TYGIEL sp. z o.o.: Lublin, Poland, 2024; Chapter 5; pp. 66–92. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Sołowczuk, A.; Kacprzak, D. Identification of the determinants of the effectiveness of on-road chicanes in the village transition zones subject to a 50 km/h Speed Limit. Energies 2021, 14, 4002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołowczuk, A.; Kacprzak, D. Synergy effect of factors characterising village transition zones on speed reduction. Energies 2021, 14, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, A.; Kluger, R.; Liu, C.; Wu, Y.J. Effects of speed feedback signs and law enforcement on driver speed. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2021, 77, 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimpour, A. Data-Driven Approaches for Assessing the Impact of Speed Management Strategies for Arterial Mobility and Safety. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA, January 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Chaparro, K.R.; Chitturi, M.; Bill, A.; Noyce, D.A. Spatial effectiveness of speed feedback signs. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2012, 2281, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Pauw, E.; Daniels, S.; Brijs, T.; Hermans, E.; Wets, G. Behavioural effects of fixed speed cameras on motorways: Overall improved speed compliance or kangaroo jumps? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 73, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afghari, A.P.; Haque, M.M.; Washington, S. Applying fractional split model to examine the effects of roadway geometric and traffic characteristics on speeding behawior. Bus. Med. Eng. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2018, 19, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biłozor, A.; Czyża, S.; Bajerowski, T. Identification and location of a transitional zone between an urban and a rural area. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, E.; Coffee, N.; Frankc, L.; Owend, N.; Baumane, A.; Hugob, G. Walkability of local communities: Using geographic information systems to objectively assess relevant environmental attributes. Health Place 2007, 13, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pauw, E.; Daniels, S.; Brijs, T.; Hermans, E.; Wets, G. Automated section speed control on motorways: An evaluation of the effect on driving speed. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 73, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balant, M.; Lep, M. Comprehensive traffic calming as a key element of sustainable urban mobility plans—Impacts of a neighbourhood redesign in Ljutomer. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołowczuk, A.; Kacprzak, D. Identification of determinants of the speed-reducing effect of pedestrian refuges in villages Located on a chosen regional road. Symmetry 2019, 11, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, A.; Bigdeli Rad, H.; Azimi, E. Simulation and analysis of traffic flow for traffic calming. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng. Munic. Eng. 2017, 170, 16–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bie, Y.; Qiu, T.Z.; Niu, L. Effect of speed limits at speed transition zones. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 44, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sołowczuk, A.; Kacprzak, D. Identification of the determinants of the effectiveness of on-road chicanes in transition zones to villages subject to a 70 km/h speed limit. Energies 2020, 13, 5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Wang, S.; Cheng, S.; Xu, J.; Liu, Y. Study on the Driver Visual Workload in High-Density Interchange-Merging Areas Based on a Field Driving Test. Sensors 2024, 24, 6247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Acebo, H.; Ziółkowski, R.; Gonzalo-Orden, H. Evaluation of the radar speed cameras and panels indicating the vehicles’ speed as traffic calming measures (TCM) in short length urban areas located along rural roads. Energies 2021, 14, 8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inman, V.W.; Balk, S.A.; Perez, W.A. Traffic Control Device Conspicuity, Publication No. FHWA-HRT-13-044; Federal Highway Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hallmark, S.; Peterson, E.; Fitzsimmons, E.; Hawkins, N.; Resler, J.; Welch, T. Evaluation of Gateway and Low-Cost Traffic-Calming Treatments for Major Routes in Rural Communities, Report No. CTRE Project 06-185 & Project TR-523; Iowa Highway Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lamberti, R.; Abate, D.; De Guglielmo, M.L.; Dell’Acqua, G.; Esposito, T.; Galante, F.; Mauriello, F.; Montella, A.; Pernetti, M. Perceptual measures and physical devices for traffic calming along a rural highway crossing a small urban community: Speed behavior evaluation in a driving simulator. In Proceedings of the Transportation Research Board 88th Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, USA, 11–15 January 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, Q.; Alhajyaseen, W.K.M.; Reinolsmann, N.; Wets, G.; Brijs, T. Optical pavement treatments and their impact on speed and lateral position at transition zones: A driving simulator study. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 150, 105916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montella, A.; Calvi, A.; D’Amico, F.; Ferrante, C.; Galante, F.; Mauriello, F. A methodology for setting credible speed limits based on numerical analyses and driving simulator experiments. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2024, 100, 289–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, J. Effect of in-vehicle audio warning system on driver’s speed control performance in transition zones from rural areas to urban areas. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galante, F.; Mauriello, F.; Montella, A.; Pernetti, M.; Aria, M.; D’ambrosio, A. Traffic calming along rural highways crossing small urban communities: Driving simulator experiment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2010, 42, 1585–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brijs, T.; Ceulemans, W.; Vanroelen, G.; Jongen, E.M.M.; Daniels, S.; Wets, G. Does the effect of traffic calming measures endure over time? A simulator study on the influence of gates. Geogr. Psychol. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2013, 22, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, S.; Han, J.; Shi, H.; Zhong, F. Driver’s visual attention characteristics and their emotional influencing mechanism under different cognitive tasks. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Qi, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lian, G.; Lu, W.; Chan, C.-Y. Drivers’ visual attention characteristics under different cognitive workloads: An on-road driving behavior study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ariën, C.; Jongen, E.M.M.; Brijs, K.; Brijs, T.; Daniels, S.; Wets, G. A simulator study on the impact of traffic calming measures in urban areas on driving behavior and workload. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2013, 61, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.T.; Figureueira, A.C.; Larocca, A.P.C. An eye-tracking study of the effects of dimensions of speed limit traffic signs on a mountain highway on driverś perception. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2022, 87, 42–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Duffy, V.G.; Tian, R. Geometric Constraints and Visual Field Related to Speed Management, Final Report FHWA/IN/JTRP-2024/10; Indiana Department of Transportation (SPR): Indianapolis, IN, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gehlert, T.; Schulze, C.; Schlag, B. Evaluation of different types of dynamic speed display signs. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2012, 15, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Simone, A.; Vignali, V.; Lantieri, C.; Bucchi, A.; Dondi, G. Looking behavior for vertical road signs. Transp. Res. Part F Psychol. Behav. 2014, 23, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, M. The information that drivers use: Is it indeed 90% visual? Perception 1996, 25, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Underwood, G. Visual attention and the transition from novice to advanced driver. Ergonomics 2007, 50, 1235–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anacta, V.; Schwering, A.; Li, R.; Münzer, S. Orientation information in wayfinding instructions: Evidences from human verbal and visual instructions. GeoJournal 2017, 82, 567–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, T.; Meng, F.; Li, Y.; Cao, S. Classification of driver distraction risk levels: Based on driver’s gaze and secondary driving tasks. Mathematics 2022, 10, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, G.; Zhan, Z.; Peng, X.; Xu, H.; Fu, Y.; Jiang, L. A study of driver’s driving concentration based on computer vision technology. SAE Tech. Pap. 2020, 1, 0572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highway Capacity Manual HCM; Transportation Research Board TRB: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- System Ewidencji Wypadków i Kolizji SEWIK. Available online: https://sewik.pl/ (accessed on 23 September 2025). (In Polish).

- Convention on Road Traffic, Vienna, 8 November 1968, Entry into Force: 21 May 1977, in Accordance with Article 47(1), Registration: 21 May 1977, No. 15705. Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/trans/conventn/crt1968e.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Li, Y.; Li, G.; Peng, K. Research on Obstacle avoidance trajectory planning for autonomous vehicles on structured roads. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P. Social interactions between automated vehicles and human drivers: A narrative review. Ergonomics 2024, 68, 1761–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolettano, E.T.; Kusano, K.; Victor, T. Potential safety benefits associated with speed limit compliance in San Francisco and Phoenix. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2025, 26, S21–S30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprenger, A.; Schneider, W.; Derkum, H. Traffic Signs, Visibility and Recognition; Gale, A.G., Brown, I.D., Haslegrave, C.M., Taylor, S.P., Eds.; Vision in vehicle; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1999; Chapter VII; pp. 421–425. [Google Scholar]

- Babkov, V.F. Road Design Parameters and the Safety of Traffic; WKŁ: Warszawa, Poland, 1975. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs, F.D.; Richardson, B.D. Traffic Engineering; Pergamon Press: Edinburgh, UK, 1967; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, Z.; Qi, C.; Zhu, S. Driver’s attention allocation and mental workload at different random hazard points on prairie highway. J. Adv. Transp. 2022, 2022, 3837509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Simone, A.; Vognali, V.; Lantieri, C. Fixation distance and fixation duration to vertical road signs. Appl. Ergon. 2018, 69, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angle Mort: Comment Bien le Maîtriser? Available online: https://www.envoituresimone.com/code-de-la-route/cours/conducteur/adapter-conduite/champ-visuel/angle-mort (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Hasanujjaman, M.; Chowdhury, M.Z.; Jang, Y.M. Sensor fusion in autonomous vehicle with traffic surveillance camera system: Detection, localization, and AI networking. Sensors 2023, 23, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Yu, Z. Mono-vision based lateral localization system of low-cost autonomous vehicles using deep learning curb detection. Actuators 2021, 10, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Land Transport Safety Authority. Guidelines for Urban-Rural Speed Thresholds RTS 15; Land Transport Safety Authority: Wellington, New Zealand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mok, J.H.; Landphair, H.C.; Naderi, J.R. Landscape improvement impacts on roadside safety in Texas. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2006, 78, 263–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondieki, K.; Njuguna, M.; Gariy, A. Aesthetic indicators for sustainable road development in Kenya. Curr. Urban Stud. 2024, 12, 243–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Jiang, J.; Duffy, V.; Zhou, J.; Chen, Y.; Tian, R.; McCoy, D.; Ruble, T. Impacts of roadside vegetation and lane width on speed management in rural roads. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. Annu. Meet. 2023, 67, 2267–2273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, C.D.; Harrington, C.P.; Knodler, M.A.; Romoser, M.R.E. The influence of clear zone size and roadside vegetation on driver behavior. J. Saf. Res. 2014, 49, 97.e1–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Age Group | Age | Gender | Years Holding a Driving License | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Average | Max | M | F | Min | Average | Max | |

| Up to 30 years | 20 | 23 | 28 | 22 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| From 30 to 50 years | 34 | 42 | 50 | 14 | 18 | 8 | 21 | 33 |

| Over 50 years | 52 | 67 | 78 | 23 | 15 | 25 | 36 | 44 |

| Study Area | R = f (Percentage of ‘Always Slow Down’ Respondents; v) | R = f (Percentage of ‘Never Slow Down’ Respondents; v) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| v85 before | v85 after | vav before | vav after | v85 before | v85 after | vav before | vav after | |

| Study area A | −0.11 | −0.28 | −0.07 | −0.21 | −0.13 | 0.08 | −0.20 | 0.06 |

| Study area B | −0.16 | 0.11 | −0.48 | 0.02 | 0.54 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.33 |

| Study area C | −0.47 | −0.54 | −0.30 | −0.55 | −0.35 | −0.34 | −0.65 | −0.36 |

| Study area D | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.69 | −0.01 | −0.73 | −0.15 | −077 | −0.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Majer, S.; Sołowczuk, A. Comparing Driver Behaviour with Measured Speed—An Innovative Approach to Designing Transition Zones for Smart Cities. Sustainability 2026, 18, 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010494

Majer S, Sołowczuk A. Comparing Driver Behaviour with Measured Speed—An Innovative Approach to Designing Transition Zones for Smart Cities. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010494

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajer, Stanisław, and Alicja Sołowczuk. 2026. "Comparing Driver Behaviour with Measured Speed—An Innovative Approach to Designing Transition Zones for Smart Cities" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010494

APA StyleMajer, S., & Sołowczuk, A. (2026). Comparing Driver Behaviour with Measured Speed—An Innovative Approach to Designing Transition Zones for Smart Cities. Sustainability, 18(1), 494. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010494