Determinants of Digital Museum Users’ Continuance Intention—An Integrated Model Combining an Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Model

2.1. Development of Digital Museums and the Status of User Participation

- (1)

- Technology remains the gateway—interface ease of use, interaction fluency, device thresholds, and cross-platform compatibility directly shape whether users are willing to engage;

- (2)

- Culture–content is repeatedly shown to sustain interest—authenticity, source transparency, cultural contextualization, and perceived knowledge gain strengthen perceived value and trust;

- (3)

- Affect and social participation are gaining prominence—gamification, task design, social sharing, co-creation, and accessibility-by-design can amplify engagement within limits, with effects moderated by user motivation, device conditions, and narrative quality.

2.2. Integrated Model of the Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT

2.3. Research Hypotheses

2.3.1. Cultural Identity

2.3.2. Technological Innovation

2.3.3. Relationships Among Perceived Ease of Use, Perceived Usefulness, and Behavioral Intention

2.3.4. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT)

2.3.5. Effects of Perceived Usefulness on Behavioral Intention and Continuance Intention

2.3.6. Effect of Behavioral Intention on Continuance Usage Behavior

2.4. Research Model

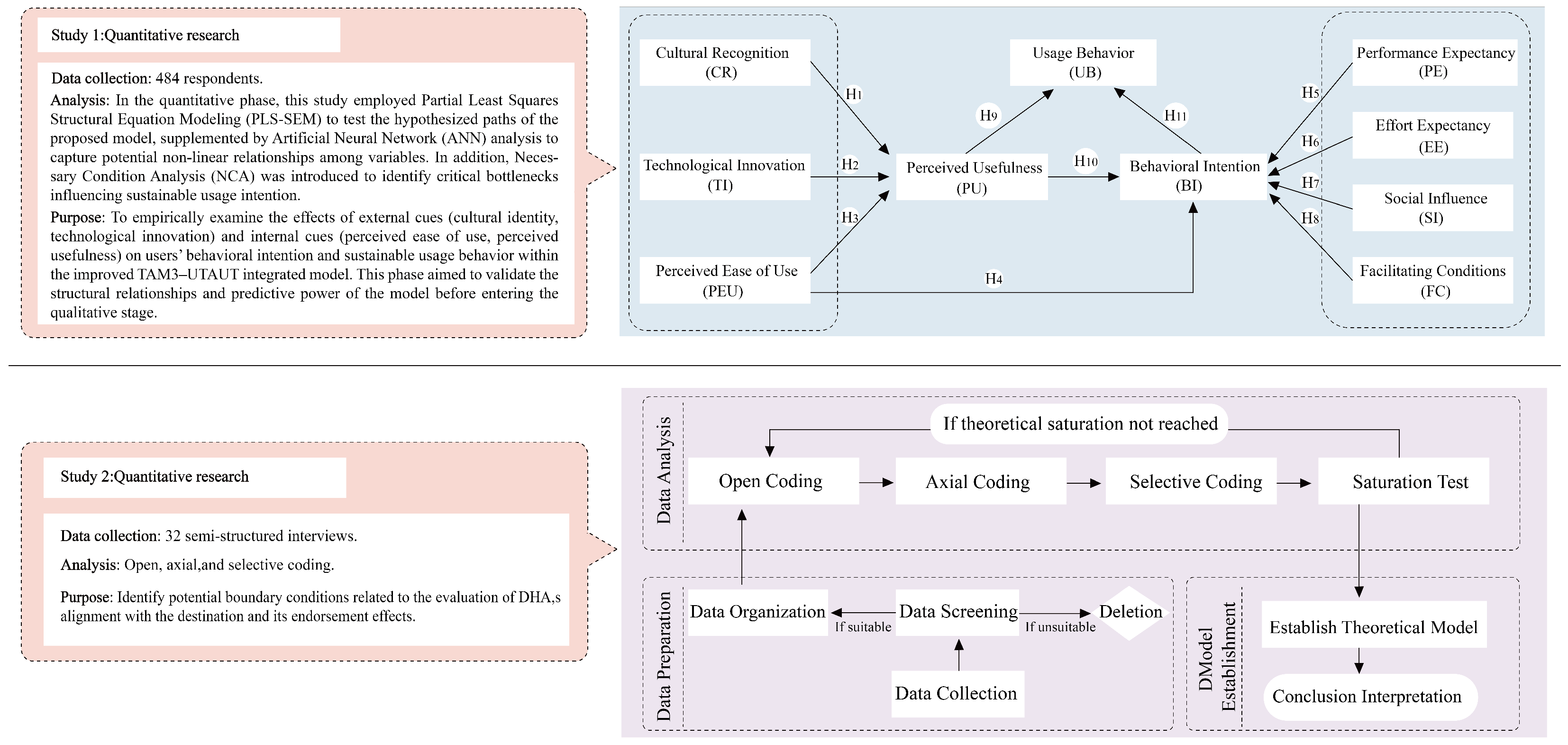

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Research Context and Site: The Cloud Tour Dunhuang Digital Museum

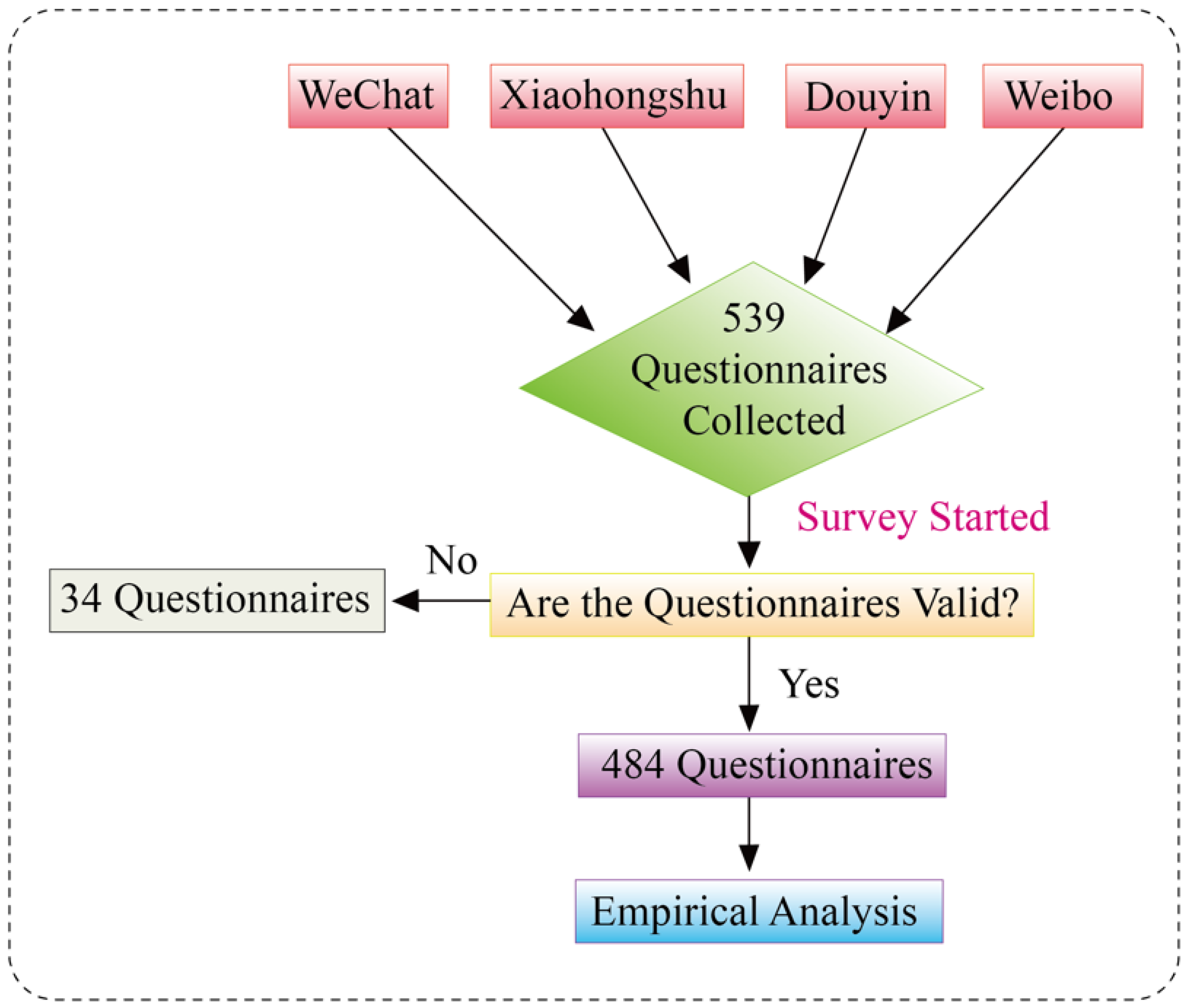

3.3. Study 1: Quantitative Phase

3.3.1. Instrumentation

3.3.2. Data Collection Procedure

3.3.3. Respondent Profile

3.3.4. Data Analysis Tools (SEM/ANN/NCA)

3.4. Study 2: Qualitative Phase

3.4.1. Sample

3.4.2. Procedure

- (1)

- Interview guide and structure.

- -

- Technological–cognitive dimension: perceptions of technological innovation, perceived usefulness, and perceived ease of use; how these attributes inform trust and evaluative judgments.

- -

- Cultural–affective dimension: cultural identity, emotional resonance, and immersion during virtual visits; mechanisms of affect formation in a digital-heritage context.

- -

- Motivational–behavioral dimension: drivers of continuance, trust formation, and revisit intention.

- (2)

- Data collection and recording.

- (3)

- Coding and analysis.

- (4)

- Integration with quantitative results.

4. Study 1: Quantitative Results

4.1. Common Method Bias

4.2. SEM Results

4.2.1. Descriptive Statistical Analysis

4.2.2. Assessment of the Measurement Model

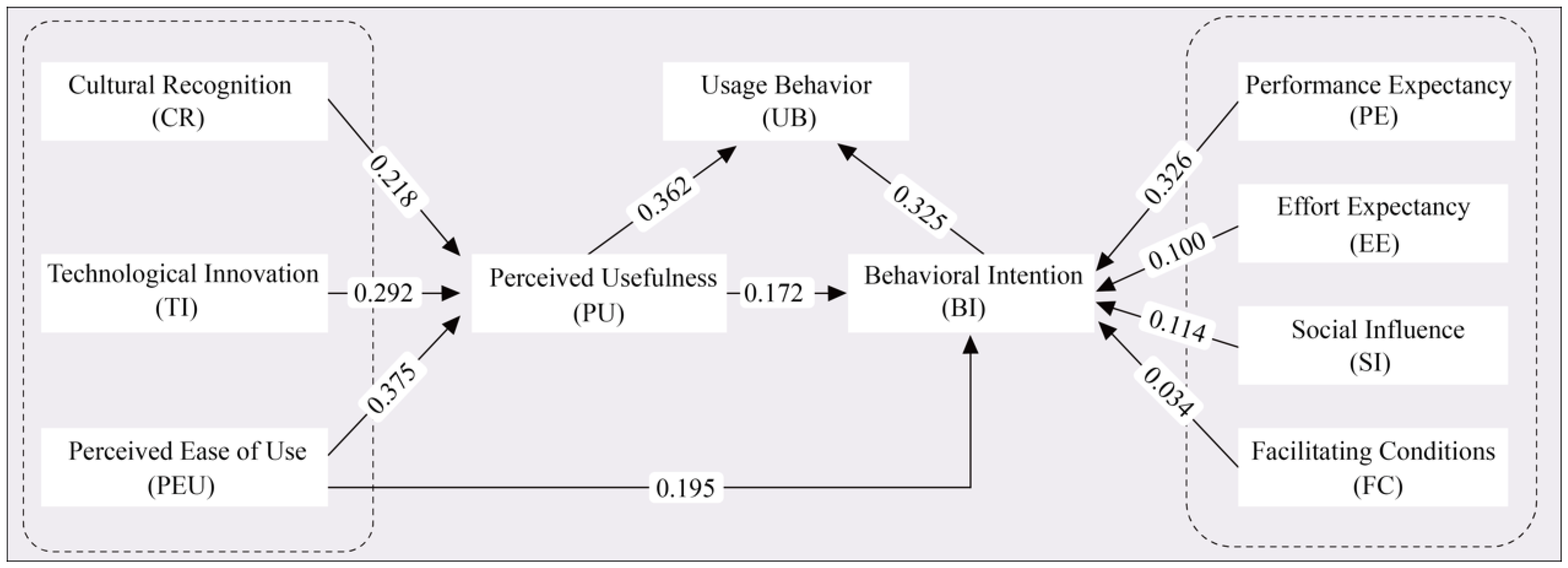

4.2.3. Assessment of the Structural Model

- (1)

- Model fit.

- (2)

- Path analysis.

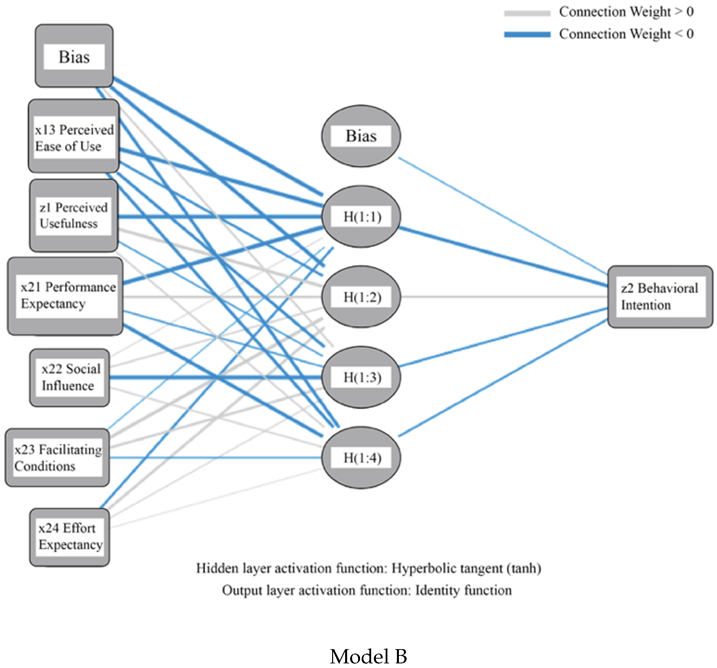

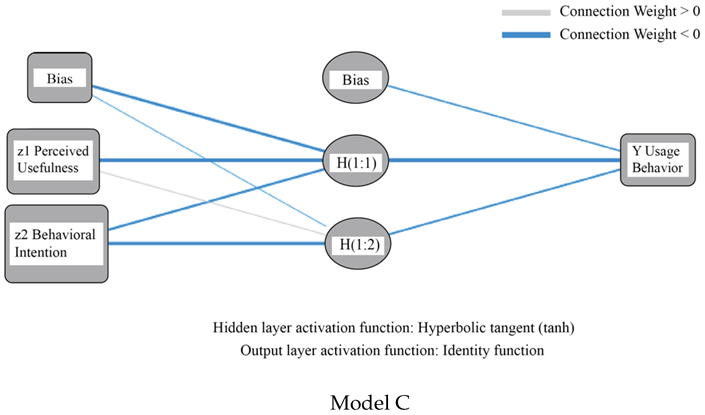

4.3. ANN Results

4.3.1. Model Construction

4.3.2. Validation of the ANN

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis

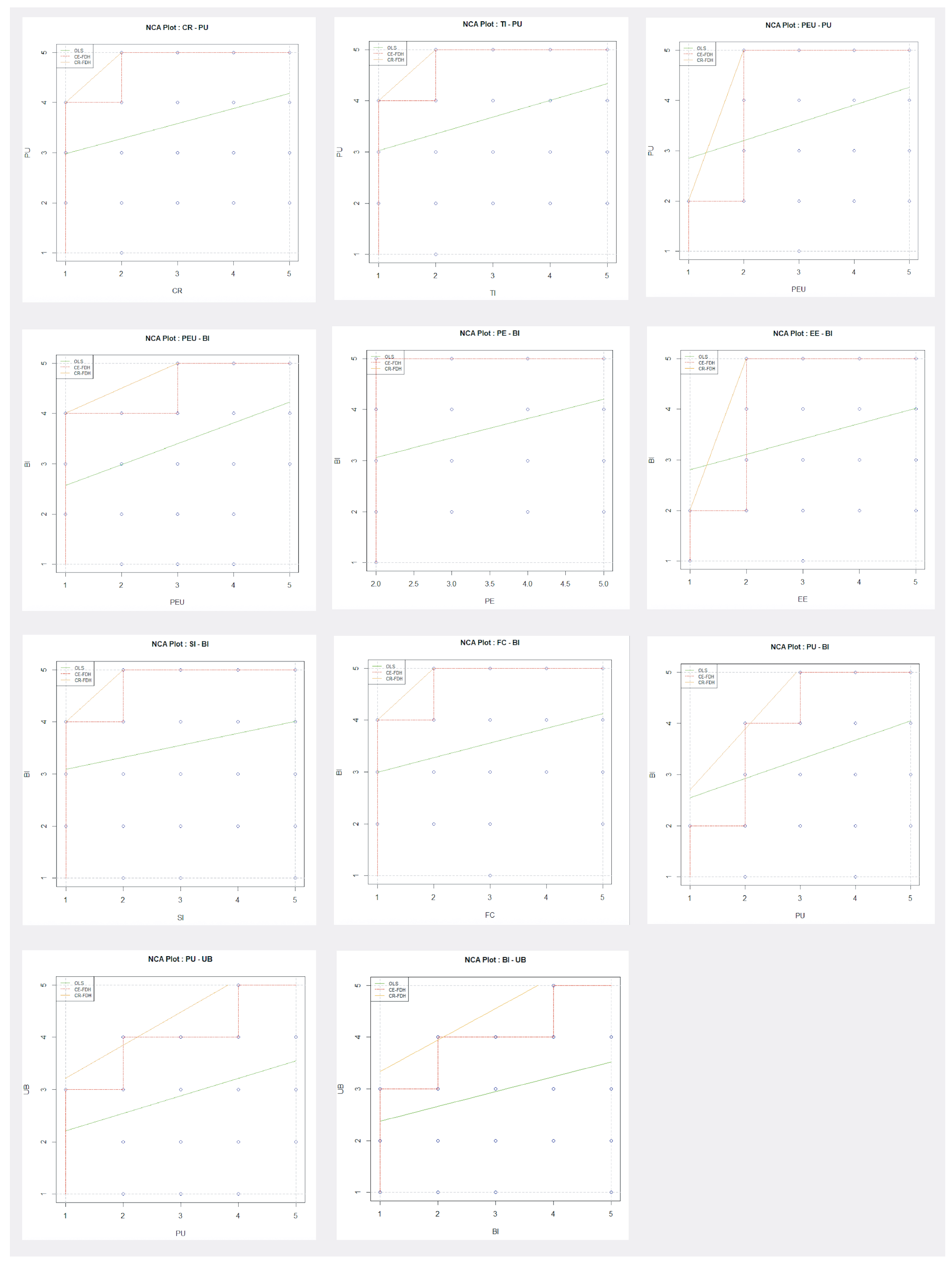

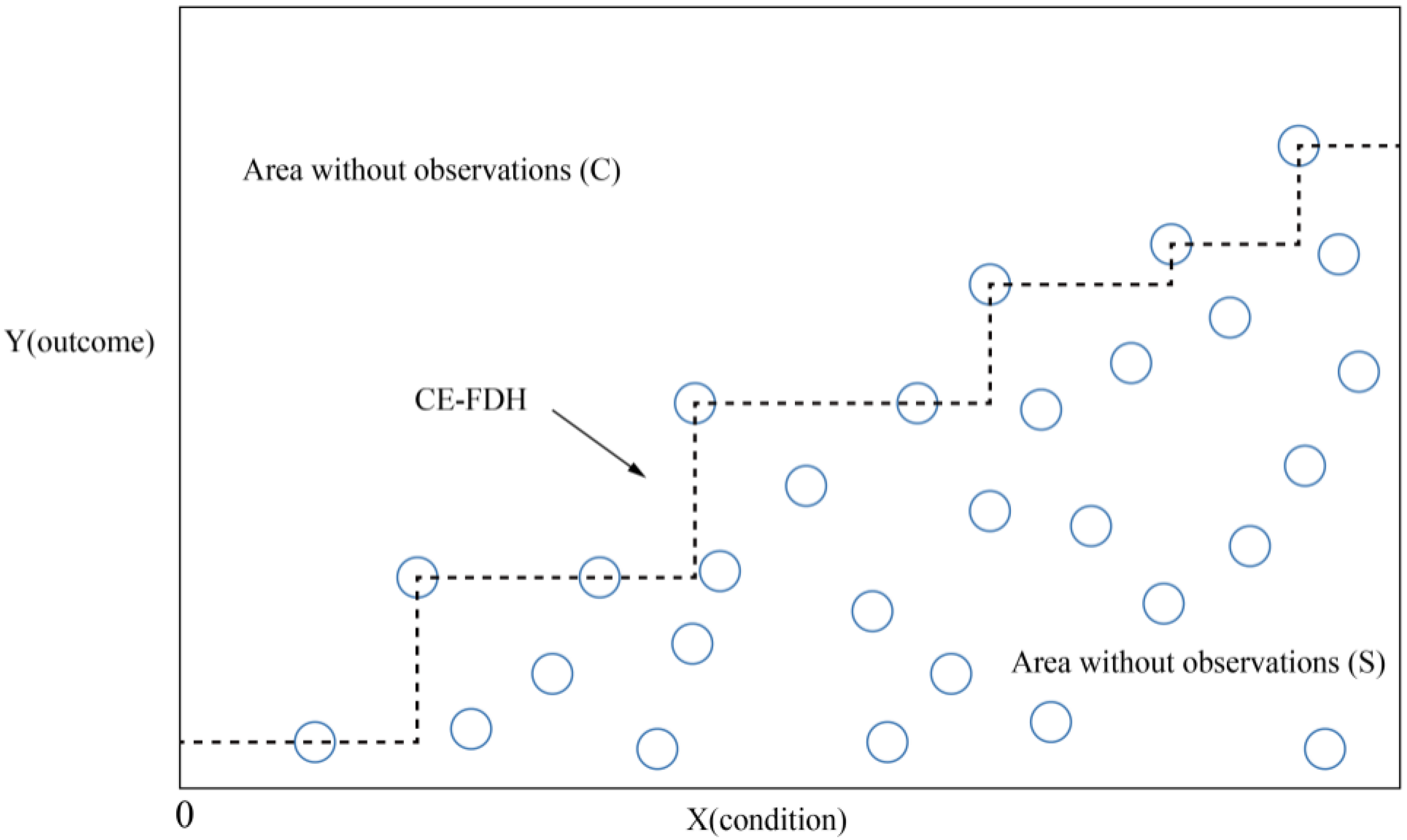

4.5. Findings of NCA

4.5.1. Effect Size and Significance Testing

4.5.2. Bottleneck Analysis

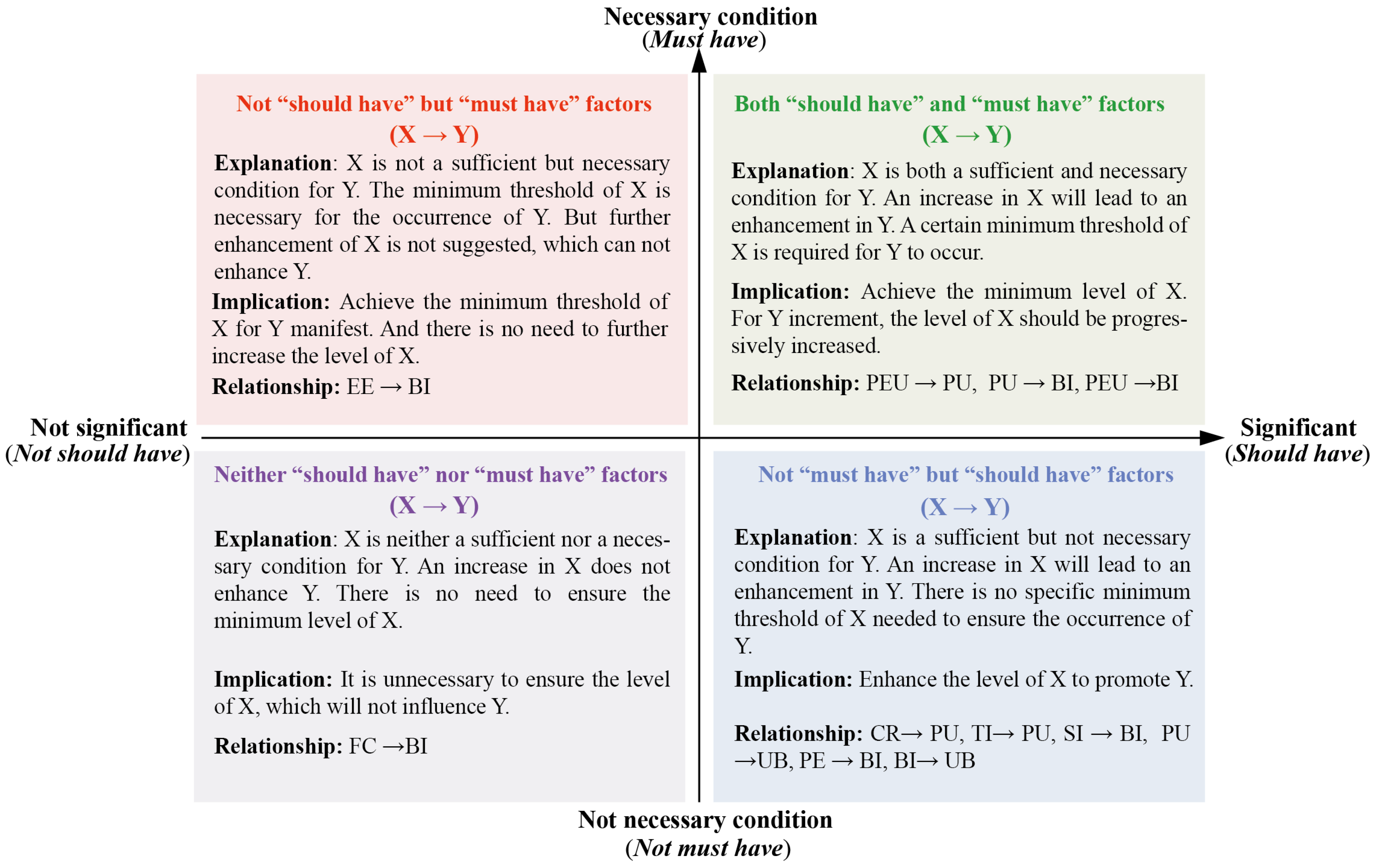

4.6. Integrating SEM and NCA: Quadrant Typology of Influencing Factors

- (1)

- “Should-have” and “must-have” factors (upper-right quadrant).

- (2)

- “Should-have” but not “must-have” factors (lower-right quadrant).

5. Study 2: Qualitative Results

5.1. Grounded Theory Approach

5.1.1. Three-Level Coding

5.1.2. Theoretical Saturation Test

5.2. Research Findings

6. Discussion

6.1. Methodological Advancement and Practical Implications

6.1.1. Comparative Analysis and Triangulation of SEM, ANN, and NCA Findings

6.1.2. Bottleneck-Threshold Analysis Based on ANN and NCA: Actionable Design and Management Implications for Digital Heritage Platforms

6.2. Discussion of Research Results

6.2.1. External Cues as a Value Channel

6.2.2. From Ease of Use to Behavior: Sufficiency Effects and Necessary Thresholds

6.2.3. Validation and Implications of the Usefulness–Intention–Continuance Chain

6.3. Contributions

6.3.1. Theoretical, Practical, and Methodological Contributions

- (1)

- Theoretical Contributions

- (2)

- Practical Contributions

- (3)

- Methodological Contributions

6.3.2. Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

- Povroznik, N. Museums’ digital identity: Key components. In Internet Hist; Routledge: London, UK, 2025; pp. 169–184. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, Y.; Xiao, H.; Yang, Y. Constructing identity in space and place: Semiotic and discourse analyses of museum tourism. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, M. Iconological Reconstruction and Complementarity in Chinese and Korean Museums in the Digital Age: A Comparative Study of the National Museum of Korea and the Palace Museum. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhill, E.H. Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge; Routledge: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Chu, M.Y.; Chiu, D.K. The impact of COVID-19 on museums in the digital era: Practices and challenges in Hong Kong. Library Hi Tech 2022, 41, 130–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Liao, J. Antecedents of viewers’ live streaming watching: A perspective of social presence theory. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 9629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, W. From digital museums to on-site visiting: The mediation of cultural identity and perceived value. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Xiao, B.; Qi, Q.; Cheng, J.; Ji, P. Digital twin modeling. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 372–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Xu, S.; Wu, G. Earth Science Digital Museum (ESDM): Toward a new paradigm for museums. Comput. Geosci. 2006, 32, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M.C.; Riviezzo, A.; Zamparo, G.; Napolitano, M.R. It is worth a visit! Website quality and visitors’ intentions in the context of corporate museums: A multimethod approach. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 3027–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.; Kim, J. Changes and challenges in museum management after the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bernardi, P.; Bertello, A.; Shams, S.M.R. Logics hindering digital transformation in cultural heritage strategic management: An exploratory case study. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Liu, Y. A systematic review of digital transformation technologies in museum exhibition. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 161, 108407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, K.; Narayanan, S. Culture and social identity in preserving cultural heritage: An experimental study. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2017, 44, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B.; Howard, P. Heritage and identity. In The Routledge Research Companion to Heritage and Identity; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zahidi, Z.; Lim, Y.P.; Woods, P.C. User Experience for Digitization and Preservation of Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the 2013 International Conference on Informatics and Creative Multimedia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 4–6 September 2013; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Cucchiara, R.; Grana, C.; Borghesani, D.; Agosti, M.; Bagdanov, A. Multimedia for Cultural Heritage: Key Issues. In Multimedia for Cultural Heritage; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 206–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pisani, S.; Miller, A.; Cassidy, C.; Clarke, L.; Oliver, I.; Gomes, G. Introducing sociodata in virtual museums: A holistic approach for sustainable development in cultural landscapes. In Proceedings of the Digital Heritage International Congress, Siena, Italy, 8–13 September 2025; The Eurographics Association: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- China Daily. The “Cloud Tour Dunhuang” Mini-Program Has Exceeded 1 Million Users in Ten Days, with Those Born in the 1980s and 1990s Accounting for More Than 60%. Available online: https://tech.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202003/05/WS5e60b541a3107bb6b57a47e4.html (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Wang, S.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H. ‘Smart Museum’ in China: From technology labs to sustainable knowledgescapes. Digit. Scholarsh. Humanit. 2023, 38, 1340–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, A.; Li, M.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, H.; Zhao, Y. A study on the mechanisms influencing older adults’ willingness to use digital displays in museums from a cognitive age perspective. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Digital design of smart museum based on artificial intelligence. Mob. Inf. Syst. 2021, 1, 4894131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Li, Y.; Wei, X.; Xie, L.; Yu, L.; Liang, H.N. CubeMuseum AR: A tangible augmented reality interface for cultural heritage learning and museum gifting. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2024, 40, 1409–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M.; Caridakis, G. Adding culture to UX: UX research methodologies and applications in cultural heritage. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2020, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C. How generous interface affects user experience and behavior: Evaluating the information display interface for museum cultural heritage. Comput. Animat. Virtual Worlds 2024, 35, e2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, L. What influences user continuous intention of digital museum: Integrating task-technology fit (TTF) and unified theory of acceptance and usage of technology (UTAUT) models. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ni, S.; Liang, H.E. Critical factors for predicting users’ acceptance of digital museums for experience-influenced environments. Information 2021, 12, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding information systems continuance: An expectation-confirmation model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaihani, F.M.F.; Islam, M.A.; Saatchi, S.G.; Haque, M.A. Harnessing Green purchase intention of generation z consumers through Green marketing strategies. Bus. Strat. Dev. 2024, 7, e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathak, K.; Prakash, G.; Samadhiya, A.; Kumar, A.; Luthra, S. Impact of Gen-AI chatbots on consumer services experiences and behaviors: Focusing on the sensation of awe and usage intentions through a cybernetic lens. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2025, 82, 104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidan, A.A.; Alnoor, A.; Albahri, O.S.; Mohammed, R.T.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Albahri, A.S.; Malik, R.Q. Review of artificial neural networks contribution methods integrated with structural equation modeling and multicriteria decision analysis for selection customization. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 124, 106643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, X.M.; Lee, V.H.; Leong, L.Y. Mobile-lizing continuance intention with the mobile expectation-confirmation model: An SEM-ANN-NCA approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursic, E.; Golja, T.; Benassi, H.M. Analysis of Croatian Public Museums’ Digital Initiatives Amid COVID-19 and Recommendations for Museum Management and Governance. Manag.-J. Contemp. Manag. Issues 2023, 28, 211–226. [Google Scholar]

- Banfi, F.; Oreni, D. Unlocking the interactive potential of digital models with game engines and visual programming for inclusive VR and web-based museums. Virtual Archaeol. Rev. 2025, 16, 44–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illsley, W.R.; Almevik, G.; Westin, J.; Aavaranta; Hansén, J.B.; Fornander, E.; Hallgren, E.; Lagercrantz, W.; Vasileiou, P. The edutainment scan: Immersive media and its deployment in museums. Mus. Manag. Curatorsh. 2025, 40, 18–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apollonio, F.I.; Zannoni, M.; Fantini, F.; Garagnani, S.; Barbieri, L. Accurate Visualization and Interaction of 3D Models Belonging to Museums’ Collection: From the Acquisition to the Digital Kiosk. ACM J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2025, 18, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Lim, C.K.; Halim, S.A.; Ahmed, M.F.; Tan, K.L.; Li, L. Digital Sustainability of Heritage: Exploring Indicators Affecting the Effectiveness of Digital Dissemination of Intangible Cultural Heritage Through Qualitative Interviews. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzanti, P.; Ferracani, A.; Bertini, M.; Principi, F. Reshaping Museum Experiences with AI: The RelnHerit Toolkit. Heritage 2025, 8, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Liang, J.; Shuai, K.; Li, Y.; Yan, J. HeritageSite AR: An Exploration Game for Quality Education and Sustainable Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.; Nam, D.; Choi, S. Augmenting outdated museum exhibits with embodied and tangible interactions for prolonged use and learning enhancement. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2025, 198, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatto, C.; Barba, M.C.; Chiarello, S.; Corchia, L.; Faggiano, F.; Nuzzo, B.L.; De Paolis, L.T. Breaking the barriers: Extended reality and innovative technologies for enhanced accessibility of the Ceramics Museum of Cutrofiano. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2025, 36, e00400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louho, R.; Kallioja, M.; Oittinen, P. Factors affecting the use of hybrid media applications. Graph. Arts Finl. 2006, 35, 11–21. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Sloan School of Management, MIT, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Othman, M.K. Investigating the behavioural intentions of museum visitors towards VR: A systematic literature review. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2024, 155, 108167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Bala, H. Technology acceptance model 3 and a research agenda on interventions. Decis. Sci. 2008, 39, 273–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Wamba, S.F.; Dwivedi, R. The extended Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2): A systematic literature review and theory evaluation. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2021, 57, 102269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.L.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, Y.K.; Rana, N.P.; Jeyaraj, A.; Clement, M.; Williams, M.D. Re-examining the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Inf. Syst. Front. 2019, 21, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.A.; Natarajan, S.; Hamsa, A.; Sharma, A. Behavioral intention to use mobile learning: Evaluating the role of self-efficacy, subjective norm, and WhatsApp use habit. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 208058–208074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Hao, A.; Guan, C.; Hsieh, T.J. Affective and cognitive dimensions in cultural identity: Scale development and validation. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2019, 32, 1362–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.H.; Wang, R.X.; Sun, Z.F. Ethnic contact weakens ethnic essentialism: The mediating role of cultural identity and cultural similarity. J. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 2, 445–451. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Ai, S. Study on impact of Daming Palace National Heritage Park tourist experience on tourists’ cultural identity. Areal Res. Dev. 2021, 40, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Keillor, B.D.; Hult, G.T.M.; Erffmeyer, R.C.; Babakus, E. NATID: The development and application of a national identity measure for use in international marketing. J. Int. Mark. 1996, 4, 57–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altugan, A.S. The relationship between cultural identity and learning. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, M. The elements of visitor experience in post-digital museum design. Des. Princ. Pract. 2020, 14, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, A.; Gonçalves, R.; Oliveira, T.; Lorga, A. Aram: A technology acceptance model to ascertain the behavioural intention to use augmented reality. J. Imaging 2023, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, P.K.; Liang, R.H.; Ma, S.Y.; Kong, B.W. Exploring the experience of traveling to familiar places in VR: An empirical study using Google Earth VR. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. 2022, 40, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalving, M.; Paananen, S.; Seppälä, J.; Colley, A.; Häkkilä, J. Comparing VR and desktop 360 video museum tours. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Multimedia, Lisbon, Portugal, 27–30 November 2022; pp. 282–284. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.; Bagozzi, R.; Warshaw, P. User acceptance of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical models. Manag. Sci. 1989, 35, 982–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, L.; Li, Y.; Xue, Y. Will the interest triggered by virtual reality (VR) turn into intention to travel (VR vs. Corporeal)? The moderating effects of customer segmentation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.S. Perceived fit and satisfaction on web learning performance: IS continuance intention and task-technology fit perspectives. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Stud. 2012, 70, 498–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briz-Ponce, L.; Pereira, A.; Carvalho, L.; Juanes-Méndez, J.A.; García-Peñalvo, F.J. Learning with mobile technologies—Students’ behavior. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 612–620. [Google Scholar]

- Isaias, P.; Reis, F.; Coutinho, C.; Lencastre, J.A. Empathic technologies for distance/mobile learning: An empirical research based on the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2017, 14, 159–180. [Google Scholar]

- Phang, C.W.; Sutanto, J.; Kankanhalli, A.; Li, Y.; Tan, B.C.Y.; Teo, H.H. Senior citizens’ acceptance of information systems: A study in the context of e-government services. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2006, 53, 555–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selmanović, E.; Gaeta, A.; Mangina, E.; Martinez, S. Improving accessibility to intangible cultural heritage preservation using virtual reality. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. (JOCCH) 2020, 13, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Chung, T.L.; Fiore, A.M. Factors affecting current users’ attitude towards e-auctions in China: An extended TAM study. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 34, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, V.; Fagan, M.; Kilmon, C. Exploring the adoption of a virtual reality simulation: The role of perceived ease of use, perceived usefulness and personal innovativeness. Campus-Wide Inf. Syst. 2012, 29, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hung, S.Y.; Chen, C.C.; Hung, H.M.; Ho, W.W. Critical factors predicting the acceptance of digital museums: User and system perspectives. J. Electron. Commer. Res. 2013, 14, 231. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, S.G.; Zayed, S. Exploring critical determinants in deploying mobile commerce technology. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2010, 7, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Louzi, B.; Iss, B. Factors influencing customer acceptance of m-commerce services in Jordan. J. Commun. Comput. 2011, 9, 1424–1436. [Google Scholar]

- Fong, L.H.N.; Lam, L.W.; Law, R. How locus of control shapes intention to reuse mobile apps for making hotel reservations: Evidence from Chinese consumers. Tour. Manag. 2017, 61, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Lu, Y.; Wang, B. Integrating TTF and UTAUT to explain mobile banking user adoption. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2010, 26, 760–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Shouk, M.; Soliman, M. The impact of gamification adoption intention on brand awareness and loyalty in tourism: The mediating effect of customer engagement. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 20, 100559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Xing, G.; Xin, J. Impacting elements of metaverse platforms’ intentional use in cultural education: Empirical data drawn from UTAUT, TTF, and flow theory. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Milon, A.; Olarte-Pascual, C.; Juaneda-Ayensa, E. Assessing the moderating effect of COVID-19 on intention to use smartphones on the tourist shopping journey. Tour. Manag. 2021, 87, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Persist or abandon? Exploring Chinese users’ continuance intentions toward AI painting tools. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 135469–135488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, D.A.; Nelson, R.R.; Todd, P.A. Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information technology: A replication. MIS Q. 1992, 16, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Wang, Q.; Long, Y. Exploring the key drivers of user continuance intention to use digital museums: Evidence from China’s Sanxingdui Museum. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 81511–81526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M. Diffusion of Innovations, 5th ed.; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Sabherwal, R.; Jeyaraj, A.; Chowa, C. Information system success: Individual and organizational determinants. Manag. Sci. 2006, 52, 1849–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limayem, M.; Hirt, S.G.; Cheung, C.M.K. How habit limits the predictive power of intention: The case of information systems continuance. MIS Q. 2007, 31, 705–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J.W.; Shope, R.; Plano Clark, V.L.; Green, D.O. How interpretive qualitative research extends mixed methods research. Res. Sch. 2006, 13, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, W.M. Philosophy of science and research paradigm for business research in the transformative age of automation, digitalization, hyperconnectivity, obligations, globalization and sustainability. J. Trade Sci. 2023, 11, 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Q.E. Dunhuang on the Silk Road: A hub of Eurasian cultural exchange—Introduction. Chin. Stud. Hist. 2020, 53, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, X. Artificial intelligence for Dunhuang cultural heritage protection: The project and the dataset. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2646–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X. Dunhuang Culture along the “Belt and Road” and Its Contemporary Connotation. Renmin Luntan 2024, 4, 106–109. [Google Scholar]

- World Internet Conference. Available online: https://subsites.chinadaily.com.cn/wic/2022-12/07/c_942989.htm (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- National Cultural Heritage Administration. Available online: http://www.ncha.gov.cn/art/2023/8/17/art_722_183524.html (accessed on 19 February 2025).

- Dunhuang Academy. Available online: https://www.dha.ac.cn (accessed on 24 February 2025).

- Hung, W. Spatial Dunhuang: Experiencing the Mogao Caves; University of Washington Press: Seattle, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Guo, Y. A new destination on the palm? The moderating effect of travel anxiety on digital tourism behavior in extended UTAUT2 and TTF models. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 965655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grace, J.B.; Bollen, K.A. Representing general theoretical concepts in structural equation models: The role of composite variables. Environ. Ecol. Stat. 2008, 15, 191–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Will PLS have to become factor-based to survive and thrive? An information systems action research outlook. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2024. in print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent partial least squares path modeling. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Tan, G.W.; Yuan, Y.; Ooi, K.; Dwivedi, Y.K. Revisiting TAM2 in behavioral targeting advertising: A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 175, 121345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, A.; Tan, G.W.; Ooi, K.; Hew, T.; Yew, K. The effects of convenience and speed in m-payment. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2015, 115, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taneja, A.; Arora, A. Modeling user preferences using neural networks and tensor factorization model. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2019, 45, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, N.F.; Schubring, S.; Hauff, S.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. When predictors of outcomes are necessary: Guidelines for the combined use of PLS-SEM and NCA. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 2243–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategy of Qualitative Research; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967; pp. 377–380. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S.J.; Van Witteloostuijn, A.; Eden, L. Common method variance in international business research. In Research Methods in International Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 385–398. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, Z. Digitalization of Art Exhibitions in Times of COVID-19: Three Case Studies in China. In Practicing Sovereignty: Digital Involvement in Times of Crises; Transcript Verlag: Bielefeld, Germany, 2022; pp. 339–355. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, J.; Yan, R.; Gao, Q.; Zhen, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, L. WeChat mini program in laboratory biosafety education among medical students at Guangzhou Medical University: A mixed method study of feasibility and usability. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, P.S.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Tan, G.W.H.; Ooi, K.B.; Aw, E.C.X.; Metri, B. Why do consumers buy impulsively during live streaming? A deep learning-based dual-stage SEM-ANN analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 147, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.K.; Singh, G.; Sadeque, S.; Harrigan, P.; Coussement, K. Customer engagement with digitalized interactive platforms in retailing. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 164, 114001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, B.; Dul, J. Analyzing relationships of necessity not just in kind but also in degree: Complementing fsQCA with NCA. Sociol. Methods Res. 2018, 47, 872–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dul, J.; Van der Laan, E.; Kuik, R. A statistical significance test for necessary condition analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 2020, 23, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dul, J.; Vis, B.; Goertz, G. Necessary Condition Analysis (NCA) does exactly what it should do when applied properly: A reply to a comment on NCA. Sociol. Methods Res. 2021, 50, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Si, H.; Xia, X. Understanding the non-users’ acceptability of autonomous vehicle hailing services using SEM-ANN-NCA approach. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2025, 110, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.Y.; Hew, T.S.; Ooi, K.B.; Chau, P.Y. “To share or not to share?”—A hybrid SEM-ANN-NCA study of the enablers and enhancers for mobile sharing economy. Decis. Support Syst. 2024, 180, 114185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, M.; Ferr e, M.; Martin-Ortega, J.; Blanche, R.; Lawford-Rolfe, R.; Dallimer, M.; Holden, J. Evaluating impact from research: A methodological framework. Res. Policy 2021, 50, 104147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Le, B.; Wang, L. Why people use augmented reality in heritage museums: A socio-technical perspective. Herit. Sci. 2024, 12, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evrard, Y.; Krebs, A. The authenticity of the museum experience in the digital age: The case of the Louvre. J. Cult. Econ. 2018, 42, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Research Topic | Method | Influencing Factors | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [34] | Transforming HBIM/3D heritage assets into interactive, cross-platform VR/Web museums through game engines and visual scripting | Technical prototyping; importing existing 3D/HBIM assets into Unity/ Unreal Engine; multi-platform testing (desktop, headset, and web) | Interactivity, real-time rendering, cross-device accessibility, cost of digital asset reuse | The study indicated that digital museums have evolved from static visualization to interactive/immersive and inclusive access. However, user engagement remains constrained by hardware performance and production costs, resulting in technically accessible yet uneven participation depth. |

| [35] | Immersive media deployment and educational assessment in museums | Literature review, multi-case comparison, and critical analysis | Level of immersion, pedagogical integration, transparency of source/reconstruction, maintenance cost | The findings revealed that immersion does not necessarily equate to learning effectiveness. Many museums were “digitally ready” but not “technologically prepared.” The absence of systematic evaluation frameworks hindered sustained user engagement, highlighting the need for integrating educational and interactive design. |

| [36] | High-precision 3D artifact visualization and interaction design for diverse audiences | Engineering workflow: 3D scanning, modeling, decimation, and multi-platform deployment | Model accuracy, interface usability, interaction cost for different audiences | Results demonstrated that improved interaction significantly enhanced instant engagement; however, audience heterogeneity and platform compatibility issues led to stratified participation—visibility does not ensure repeated engagement. |

| [37] | Indicators and sustainability factors influencing the effectiveness of intangible cultural heritage digital dissemination | Semi-structured interviews and three-stage grounded theory coding | Authenticity, completeness, stakeholder participation, cultural contextualization | The study emphasized that without the inclusion of cultural and emotional dimensions, digital accessibility alone cannot sustain engagement. Cultural identity should therefore be integrated into subsequent behavioral models. |

| [38] | Enhancing interactivity and inclusivity in European small and medium-sized museums through AI, gamification, and mobile tools | Toolkit design and stakeholder (staff/visitor) needs assessment | Mobile accessibility, gamification, emotional engagement, institutional technological capacity | The research found that visitors preferred playable, no-download, and shareable interactive experiences. However, technological and human resource gaps within museums resulted in limited deployment and unstable participation. |

| [39] | AR-based exploratory heritage games for enhancing education and sustainable cultural engagement | Expert interviews, online survey, and AR prototype user testing | Contextual storytelling, route guidance, task/reward mechanisms, social sharing, device constraints | Findings showed that gamification substantially improved on-site participation and learning outcomes. Nonetheless, its sustainability relied on content design quality and user motivation, limiting long-term online engagement. |

| [40] | Augmenting existing exhibits with embodied and tactile interactions to extend usage and learning | Controlled experiments and interaction log analysis | Embodiment, real-time feedback, playfulness, pre-exhibit guidance | Grasp rate and dwell time increased significantly, demonstrating that “engagement is designable.” However, the effects were mostly short-term, indicating the need for platform-based mechanisms to sustain engagement. |

| [41] | Application of XR and innovative technologies for accessibility and inclusion in small and specialized museums | Case study and experiential evaluation | Accessibility design, cost, audience capability differences | The study suggested that emerging technologies expanded the range of accessible users. Nevertheless, sustained engagement depended on lowering operational barriers and providing adaptive content, indicating that user participation remained context-dependent. |

| Variables | Code | Content | Original Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Innovation | TI1 | I believe the technology currently in use is innovative compared to similar products. | [59] |

| TI2 | I believe that new technologies can enhance the user experience. | ||

| TI3 | I believe that systems adopting innovative technologies can provide a competitive advantage. | ||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | I believe that using this system requires little effort, with simple functions and convenient operation. | [71] |

| PEU2 | I find it easy to learn how to use this system and am very satisfied with its interactivity. | ||

| PEU3 | I believe that the system has a user-friendly interface and is easy to operate. | ||

| Cultural Recognition | CR1 | I believe that the design of this system reflects local cultural characteristics. | [7] |

| CR2 | People who are important to me support my use of generative AI for creative purposes. | ||

| CR3 | I feel that the user experience of this system aligns with my cultural practices. | ||

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | I believe that this system can improve my work efficiency. | [71] |

| PU2 | I feel that this system helps me accomplish tasks more effectively. | ||

| PU3 | I believe that using this system is beneficial to my work or daily life. | ||

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | I am willing to use this system in the future. | [59] |

| BI2 | If possible, I would prefer to choose this system. | ||

| BI3 | I would recommend this system to others. | ||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | I intend to use this system as a long-term part of my daily work. | [81] |

| UB2 | I will regularly update and maintain the use of this system. | ||

| UB3 | I plan to rely on this system for task completion over the long term. | ||

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | I believe that this system contributes to improved job performance. | [94] |

| PE2 | I feel that using this system enables me to achieve better outcomes. | ||

| PE3 | I believe that this system can help me accomplish more complex tasks. | ||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | I believe that using this system requires considerable effort. | [94] |

| EE2 | I feel that operating this system requires a significant amount of time and effort. | ||

| EE3 | I believe that learning how to use this system is difficult. | ||

| Social Influence | SI1 | I feel that using this system can enhance my social status. | [94] |

| SI2 | I believe that people around me have a positive attitude toward the use of this system. | ||

| SI3 | I feel that people around me would encourage me to use this system. | ||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | I believe that there are sufficient resources available to support my use of this system. | [59] |

| FC2 | I feel that technical support and assistance for using this system are adequate. | ||

| FC3 | I believe that my surrounding environment is conducive to using this system. |

| Attribute | Items | Numbers | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 265 | 54.75% |

| Female | 219 | 45.25% | |

| Age | 20–30 | 175 | 36.16% |

| 31–40 | 94 | 19.42% | |

| 41–50 | 104 | 21.49% | |

| 51–60 | 84 | 17.36% | |

| 61–65 | 27 | 5.57% | |

| Occupation | Student | 178 | 36.78% |

| Cultural and Educational Professionals | 117 | 24.18% | |

| Information Technology and New Media Professionals | 76 | 15.70% | |

| Freelancers and Creative Industry Professionals | 57 | 11.78% | |

| Business Management and Administrative Professionals | 56 | 11.56% | |

| All | – | 484 | 100% |

| Variables | Code | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Skewness | Kurtosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural Recognition | CR1 | 484 | 3.364 | 0.882 | −0.271 | 0.051 |

| CR1 | 484 | 3.411 | 0.843 | −0.146 | 0.220 | |

| CR1 | 484 | 3.331 | 0.975 | −0.486 | 0.183 | |

| Technological Innovation | TI1 | 484 | 3.050 | 0.947 | 0.445 | 0.040 |

| TI1 | 484 | 3.120 | 0.938 | 0.772 | 0.155 | |

| TI1 | 484 | 3.041 | 0.895 | 0.857 | 0.658 | |

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | 484 | 3.424 | 0.832 | −0.211 | 0.085 |

| PEU1 | 484 | 3.362 | 0.923 | −0.429 | 0.013 | |

| PEU1 | 484 | 3.432 | 0.904 | −0.370 | −0.152 | |

| Perceived Usefulness | PU2 | 484 | 3.678 | 0.921 | −0.340 | −0.190 |

| PU2 | 484 | 3.682 | 0.865 | −0.437 | 0.227 | |

| PU2 | 484 | 3.717 | 0.908 | −0.477 | 0.237 | |

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | 484 | 3.494 | 0.994 | −0.275 | −0.429 |

| BI1 | 484 | 3.514 | 1.024 | −0.497 | −0.275 | |

| BI1 | 484 | 3.517 | 1.000 | −0.364 | −0.279 | |

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | 484 | 3.293 | 0.953 | 0.048 | −0.609 |

| PE1 | 484 | 3.289 | 0.903 | 0.110 | −0.378 | |

| PE1 | 484 | 3.300 | 1.021 | −0.005 | −0.799 | |

| Social Influence | SI2 | 484 | 3.432 | 0.985 | −0.142 | −0.806 |

| SI2 | 484 | 3.459 | 0.944 | −0.333 | −0.010 | |

| SI2 | 484 | 3.428 | 0.859 | −0.020 | −0.478 | |

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | 484 | 2.975 | 0.836 | 0.303 | 0.623 |

| FC1 | 484 | 3.025 | 0.887 | 0.148 | −0.001 | |

| FC1 | 484 | 2.897 | 0.860 | 0.475 | 0.357 | |

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | 484 | 3.039 | 1.040 | 0.487 | −0.292 |

| EE1 | 484 | 3.037 | 0.965 | 0.301 | 0.137 | |

| EE1 | 484 | 2.919 | 0.937 | 0.465 | 0.154 | |

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | 484 | 2.862 | 0.819 | −0.399 | −0.287 |

| UB1 | 484 | 3.680 | 0.996 | −0.788 | 0.329 | |

| UB1 | 484 | 2.845 | 0.787 | −0.435 | 0.061 |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Unstandardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | S.E | t-Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness | <—Cultural Recognition | 0.204 | 0.218 | 0.055 | 3.739 | *** |

| Perceived Usefulness | <— Technological Innovation | 0.249 | 0.292 | 0.045 | 5.538 | *** |

| Perceived Usefulness | <— Perceived Ease of Use | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.065 | 5.781 | *** |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Performance Expectancy | 0.312 | 0.326 | 0.053 | 5.91 | *** |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Effort Expectancy | 0.094 | 0.1 | 0.051 | 1.847 | 0.065 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Social Influence | 0.09 | 0.114 | 0.042 | 2.119 | * |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Facilitating Conditions | 0.037 | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.617 | 0.537 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Perceived Ease of Use | 0.225 | 0.195 | 0.082 | 2.751 | ** |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Perceived Usefulness | 0.199 | 0.172 | 0.08 | 2.474 | * |

| Usage Behavior | <— Behavioral Intention | 0.274 | 0.325 | 0.052 | 5.285 | *** |

| Usage Behavior | <— Perceived Usefulness | 0.355 | 0.362 | 0.065 | 5.485 | *** |

| Variables | Code | Unstandardized Factor Loading | Std. Error | Std. Estimate | Z(CR) | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Technological Innovation | TI1 | 1.000 | – | 0.794 | – | 0.611 | 0.825 |

| TI2 | 0.944 | 0.058 | 0.785 | 16.139 | |||

| TI3 | 1.066 | 0.067 | 0.766 | 15.881 | |||

| Perceived Ease of Use | PEU1 | 1.000 | – | 0.807 | – | 0.773 | 0.910 |

| PEU2 | 1.110 | 0.047 | 0.905 | 23.534 | |||

| PEU3 | 1.079 | 0.045 | 0.921 | 23.933 | |||

| Cultural Recognition | CR1 | 1.000 | – | 0.798 | – | 0.590 | 0.812 |

| CR2 | 1.040 | 0.067 | 0.747 | 15.573 | |||

| CR3 | 1.033 | 0.066 | 0.759 | 15.765 | |||

| Perceived Usefulness | PU1 | 1.000 | – | 0.721 | – | 0.513 | 0.759 |

| PU2 | 0.953 | 0.073 | 0.732 | 13.060 | |||

| PU3 | 0.950 | 0.075 | 0.695 | 12.649 | |||

| Behavioral Intention | BI1 | 1.000 | – | 0.803 | – | 0.631 | 0.837 |

| BI2 | 1.043 | 0.058 | 0.812 | 17.932 | |||

| BI3 | 0.964 | 0.057 | 0.769 | 17.046 | |||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | 1.000 | – | 0.827 | – | 0.696 | 0.873 |

| UB2 | 0.963 | 0.048 | 0.841 | 20.197 | |||

| UB3 | 1.082 | 0.054 | 0.835 | 20.076 | |||

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | 1.000 | – | 0.817 | – | 0.600 | 0.817 |

| PE2 | 0.793 | 0.055 | 0.676 | 14.412 | |||

| PE3 | 0.877 | 0.053 | 0.822 | 16.645 | |||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | 1.000 | – | 0.845 | – | 0.732 | 0.891 |

| EE2 | 1.071 | 0.048 | 0.853 | 22.144 | |||

| EE3 | 1.057 | 0.047 | 0.869 | 22.581 | |||

| Social Influence | SI1 | 1.000 | – | 0.924 | – | 0.785 | 0.891 |

| SI2 | 0.902 | 0.031 | 0.899 | 29.562 | |||

| SI3 | 0.812 | 0.032 | 0.833 | 25.616 | |||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | 1.000 | – | 0.784 | – | 0.664 | 0.857 |

| FC2 | 1.262 | 0.070 | 0.813 | 18.069 | |||

| FC3 | 1.039 | 0.056 | 0.847 | 18.663 |

| Model Fit Indices | Statistical Value | Threshold Value | Statistical Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMIN | 647.591 | – | – |

| DF | 373 | – | – |

| CMIN/DF | 1.74 | 1–3 | The statistical value is greater than 1 and less than 3. |

| RMR | 0.044 | 0.05 | The statistical value is below the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| GFI | 0.922 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| AGFI | 0.903 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| NFI | 0.923 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| IFI | 0.966 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| TLI | 0.960 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| CFI | 0.966 | ≥0.9 | The statistical value is above the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| RMSEA | 0.039 | ≤0.08 | The statistical value is below the minimum threshold, indicating a good fit. |

| Latent Variable | Observed Variable | Unstandardized Coefficient | Standardized Coefficient | S.E | t-Value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness | <— Cultural Identity | 0.204 | 0.218 | 0.055 | 3.739 | ** |

| Perceived Usefulness | <— Technological Innovation | 0.249 | 0.292 | 0.045 | 5.538 | ** |

| Perceived Usefulness | <— Perceived Ease of Use | 0.375 | 0.375 | 0.065 | 5.781 | ** |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Performance Expectancy | 0.312 | 0.326 | 0.053 | 5.91 | ** |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Effort Expectancy | 0.094 | 0.1 | 0.051 | 1.847 | 0.065 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Social Influence | 0.09 | 0.114 | 0.042 | 2.119 | 0.034 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Facilitating Conditions | 0.037 | 0.034 | 0.059 | 0.617 | 0.537 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Perceived Ease of Use | 0.225 | 0.195 | 0.082 | 2.751 | 0.006 |

| Behavioral Intention | <— Perceived Usefulness | 0.199 | 0.172 | 0.08 | 2.474 | 0.013 |

| Usage Behavior | <— Behavioral Intention | 0.274 | 0.325 | 0.052 | 5.285 | ** |

| Usage Behavior | <— Perceived Usefulness | 0.355 | 0.362 | 0.065 | 5.485 | *** |

| Neural Network | Model A (PV) | Model B (PV) | Model C (PV) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Input: PEU, TI, CR | Output: PU | Input: PEU, PU, PE, SI, FC, EE | Output: BI | Input: PU, BI | Output: UB | |

| Train | Test | Train | Test | Train | Test | |

| ANN1 | 0.3425 | 0.3473 | 0.3268 | 0.2320 | 0.3783 | 0.2598 |

| ANN2 | 0.3403 | 0.3376 | 0.3230 | 0.2107 | 0.3829 | 0.3832 |

| ANN3 | 0.3335 | 0.3505 | 0.3409 | 0.2837 | 0.3910 | 0.6025 |

| ANN4 | 0.3678 | 0.3588 | 0.3517 | 0.2587 | 0.3921 | 0.3102 |

| ANN5 | 0.3495 | 0.4120 | 0.3406 | 0.2706 | 0.3955 | 0.3099 |

| ANN6 | 0.3527 | 0.3052 | 0.3525 | 0.2465 | 0.3893 | 0.2955 |

| ANN7 | 0.3674 | 0.3677 | 0.3265 | 0.2271 | 0.3788 | 0.5250 |

| ANN8 | 0.3581 | 0.4494 | 0.3393 | 0.3453 | 0.3809 | 0.3729 |

| ANN9 | 0.3338 | 0.4347 | 0.3428 | 0.2369 | 0.3858 | 0.3937 |

| ANN10 | 0.3723 | 0.4064 | 0.3237 | 0.3395 | 0.3809 | 0.3766 |

| Mean | 0.3518 | 0.3770 | 0.3368 | 0.2651 | 0.3856 | 0.3829 |

| SD | 0.0143 | 0.0464 | 0.0111 | 0.0460 | 0.0061 | 0.1065 |

| ANN | Model A | Model B | Model C | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | TI | PEU | PEU | PU | PE | SI | FC | EE | PU | BI | |

| ANN1 | 0.257 | 0.315 | 0.427 | 0.252 | 0.169 | 0.246 | 0.117 | 0.100 | 0.104 | 0.527 | 0.473 |

| ANN2 | 0.165 | 0.453 | 0.381 | 0.217 | 0.165 | 0.242 | 0.142 | 0.116 | 0.118 | 0.435 | 0.565 |

| ANN3 | 0.194 | 0.433 | 0.373 | 0.215 | 0.185 | 0.258 | 0.090 | 0.128 | 0.123 | 0.499 | 0.501 |

| ANN4 | 0.362 | 0.318 | 0.321 | 0.247 | 0.161 | 0.181 | 0.032 | 0.130 | 0.250 | 0.646 | 0.354 |

| ANN5 | 0.298 | 0.279 | 0.423 | 0.176 | 0.191 | 0.260 | 0.097 | 0.114 | 0.162 | 0.514 | 0.486 |

| ANN6 | 0.293 | 0.282 | 0.425 | 0.276 | 0.187 | 0.211 | 0.049 | 0.102 | 0.175 | 0.482 | 0.518 |

| ANN7 | 0.271 | 0.322 | 0.407 | 0.175 | 0.168 | 0.283 | 0.141 | 0.109 | 0.124 | 0.513 | 0.487 |

| ANN8 | 0.236 | 0.318 | 0.446 | 0.239 | 0.219 | 0.279 | 0.093 | 0.074 | 0.096 | 0.536 | 0.464 |

| ANN9 | 0.196 | 0.421 | 0.384 | 0.253 | 0.141 | 0.276 | 0.122 | 0.123 | 0.086 | 0.535 | 0.465 |

| ANN10 | 0.378 | 0.394 | 0.228 | 0.213 | 0.196 | 0.272 | 0.104 | 0.093 | 0.122 | 0.484 | 0.516 |

| RI | 0.265 | 0.354 | 0.382 | 0.226 | 0.178 | 0.251 | 0.099 | 0.109 | 0.136 | 0.517 | 0.483 |

| NI (%) | 69.372 | 92.670 | 100.000 | 90.040 | 70.916 | 100.000 | 39.442 | 43.426 | 54.183 | 100.000 | 93.424 |

| SEM Path | SEM Path Coefficient | ANN Normalized Relative Importance (%) | Ranking (SEM) | Ranking (ANN) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model A (Output: PU) | |||||

| PEU→PU | 0.375 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| TI→PU | 0.292 | 92.670 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| CR→PU | 0.218 | 69.372 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| Model B (Output: BI) | |||||

| PU→BI | 0.172 | 70.916 | 3 | 3 | Match |

| PEU→BI | 0.195 | 90.040 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| PE→BI | 0.326 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| FC→BI | 0.034 | 43.426 | 6 | 5 | |

| SI→BI | 0.114 | 39.442 | 4 | 6 | |

| EE→BI | 0.100 | 54.183 | 5 | 4 | |

| Model C (Output: UB) | |||||

| PU→UB | 0.362 | 100.000 | 1 | 1 | Match |

| BI→UB | 0.325 | 83.924 | 2 | 2 | Match |

| Hypotheses | Relations | Scope | CE-FDH | p-Value | CR-FDH | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | CR→PU | 16 | 0.062 | 0.35 | 0.031 | 0.215 |

| H2 | TI→PU | 16 | 0.062 | 0.292 | 0.031 | 0.006 |

| H3 | PEU→PU | 16 | 0.188 | 0 | 0.094 | 0 |

| H4 | PEU→BI | 16 | 0.125 | 0.01 | 0.140 | 0 |

| H5 | PE→BI | 16 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| H6 | EE→BI | 16 | 0.188 | 0.019 | 0.094 | 0.018 |

| H7 | SI→BI | 16 | 0.062 | 0.362 | 0.031 | 0.217 |

| H8 | FC→BI | 16 | 0.062 | 0.133 | 0.031 | 0.112 |

| H9 | PU→UB | 16 | 0.25 | 0.531 | 0.158 | 0.120 |

| H10 | PU→BI | 16 | 0.25 | 0.1 | 0.14 | 0 |

| H11 | BI→UB | 16 | 0.250 | 0.226 | 0.142 | 0.028 |

| CR | TI | PEU | PE | EE | SI | FC | PU | BI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Usefulness | |||||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | ||||||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | ||||||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | ||||||

| 30 | NN | NN | 1.7 | ||||||

| 40 | NN | NN | 5.0 | ||||||

| 50 | NN | NN | 8.3 | ||||||

| 60 | NN | NN | 11.7 | ||||||

| 70 | NN | NN | 15.0 | ||||||

| 80 | 5.0 | 5.0 | 18.3 | ||||||

| 90 | 15.0 | 15.0 | 21.7 | ||||||

| 100 | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | ||||||

| Behavioral Intention | |||||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 10 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 20 | NN | NN | NN | NN | NN | ||||

| 30 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 1.7 | ||||

| 40 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 5.0 | ||||

| 50 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 8.3 | ||||

| 60 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 11.7 | ||||

| 70 | NN | NN | NN | NN | 15.0 | ||||

| 80 | 10.0 | NN | 5.0 | 5.0 | 18.3 | ||||

| 90 | 30.0 | NN | 15.0 | 15.0 | 21.7 | ||||

| 100 | 50.0 | NN | 25.0 | 25.0 | 25.0 | ||||

| Usage Behavior | |||||||||

| 0 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 10 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 20 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 30 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 40 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 50 | NN | NN | |||||||

| 60 | 7.5 | 2.7 | |||||||

| 70 | 23.3 | 19.1 | |||||||

| 80 | 39.2 | 35.5 | |||||||

| 90 | 55.0 | 51.8 | |||||||

| 100 | 70.8 | 68.2 | |||||||

| No. | Open | Axial | Selective |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “I was able to use it the first time I entered; the interface is very intuitive and doesn’t require a tutorial.” | System ease of use; Platform familiarity; intuitive interaction | Technological Trust & Reliability |

| 2 | “The AI explanations are very vivid, and it talks to me like a tour guide.” | AI-guided narration; interactive clarity; intelligent feedback | |

| 3 | “The content is updated promptly, the information is very accurate, and it’s clear that it’s from an official source.” | Content authenticity; perceived credibility; system stability | |

| 4 | “The combination of light and shadow and music is excellent, giving you the feeling of stepping into a grotto.” | Visual immersion; spatial presence; sensory flow | Affective & Aesthetic Engagement |

| 5 | “This experience brought me peace of mind, as if I had returned to the scene of history.” | Spiritual tranquility; sacred emotion; immersive atmosphere | |

| 6 | “I often recommend it to my friends, and they are all amazed by it.” | Social sharing; emotional contagion; user recommendation | |

| 7 | “Seeing the murals in Dunhuang makes me especially proud; this is our culture.” | Cultural pride; identity belonging; historical connection | Cultural Identity Integration |

| 8 | “I want students to learn about Chinese art through this platform.” | Cultural transmission; educational promotion; sense of mission | |

| 9 | “This platform has helped me to better understand the value of traditional Chinese culture.” | Cultural empathy; cognitive internalization; value realization | |

| 10 | “I learned a lot about the details of the murals that I had never seen before.” | Knowledge acquisition; curiosity; information enrichment | Perceived Educational & Cognitive Value |

| 11 | “The explanations are more interesting and easier to understand than the textbooks.” | Learning motivation; pedagogical enhancement; knowledge utility | |

| 12 | “Every time I enter, I discover something new, and the more I use it, the more addictive it becomes.” | Novelty; user engagement; expectation of discovery | Sustained & Co-creative Motivation |

| 13 | “I’ve used it many times and I’ll continue to use it.” | Habitual return; behavioral intention; satisfaction | |

| 14 | “I hope to see more interactive content in the future.” | Anticipated innovation; user feedback; improvement desire | |

| 15 | “The experience degrades when loading is slow, but overall I still like it.” | Technical barriers; effort expectancy; perceived limitation | Effort Expectancy Constraint |

| 16 | “This platform is a combination of history and technology.” | Fusion of culture and technology; cognitive-affective linkage | Cognitive-Emotional Mechanism of Sustainable Use |

| 17 | “It is not only a learning tool, but also a cultural experience.” | Cultural-aesthetic synergy; meaningful engagement | |

| 18 | “I trust this platform because it is both professional and inspiring.” | Perceived professionalism; reliability; emotional trust |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liang, N.; Wang, X. Determinants of Digital Museum Users’ Continuance Intention—An Integrated Model Combining an Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT. Sustainability 2026, 18, 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010492

Liang N, Wang X. Determinants of Digital Museum Users’ Continuance Intention—An Integrated Model Combining an Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010492

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiang, Na, and Xiaoqian Wang. 2026. "Determinants of Digital Museum Users’ Continuance Intention—An Integrated Model Combining an Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010492

APA StyleLiang, N., & Wang, X. (2026). Determinants of Digital Museum Users’ Continuance Intention—An Integrated Model Combining an Enhanced TAM3 and UTAUT. Sustainability, 18(1), 492. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010492