One-Year Monitoring of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes in the M34 Mosaic

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Mosaic Deterioration Processes

1.2. Standards on Optimal Microclimatic Conditions for the Presentation of Ancient Mosaics

1.3. Features of the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microclimate Monitoring

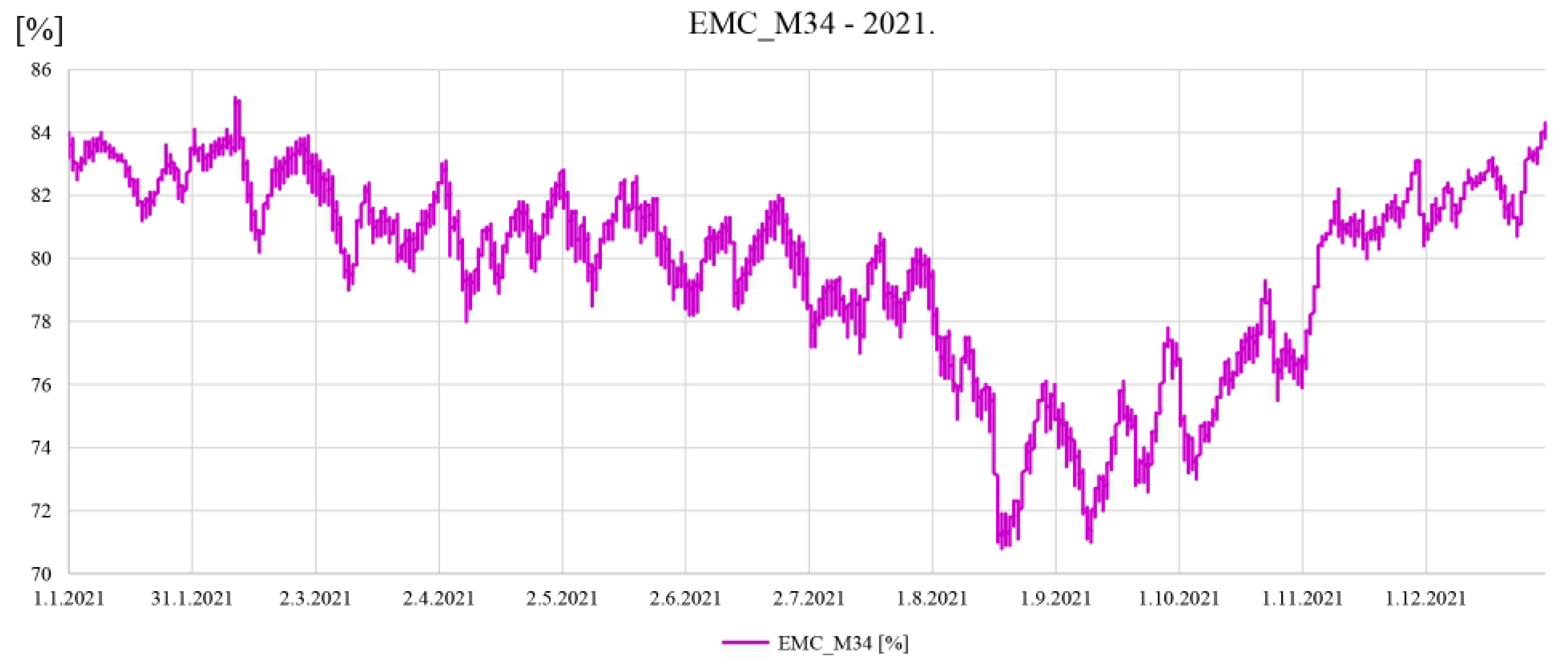

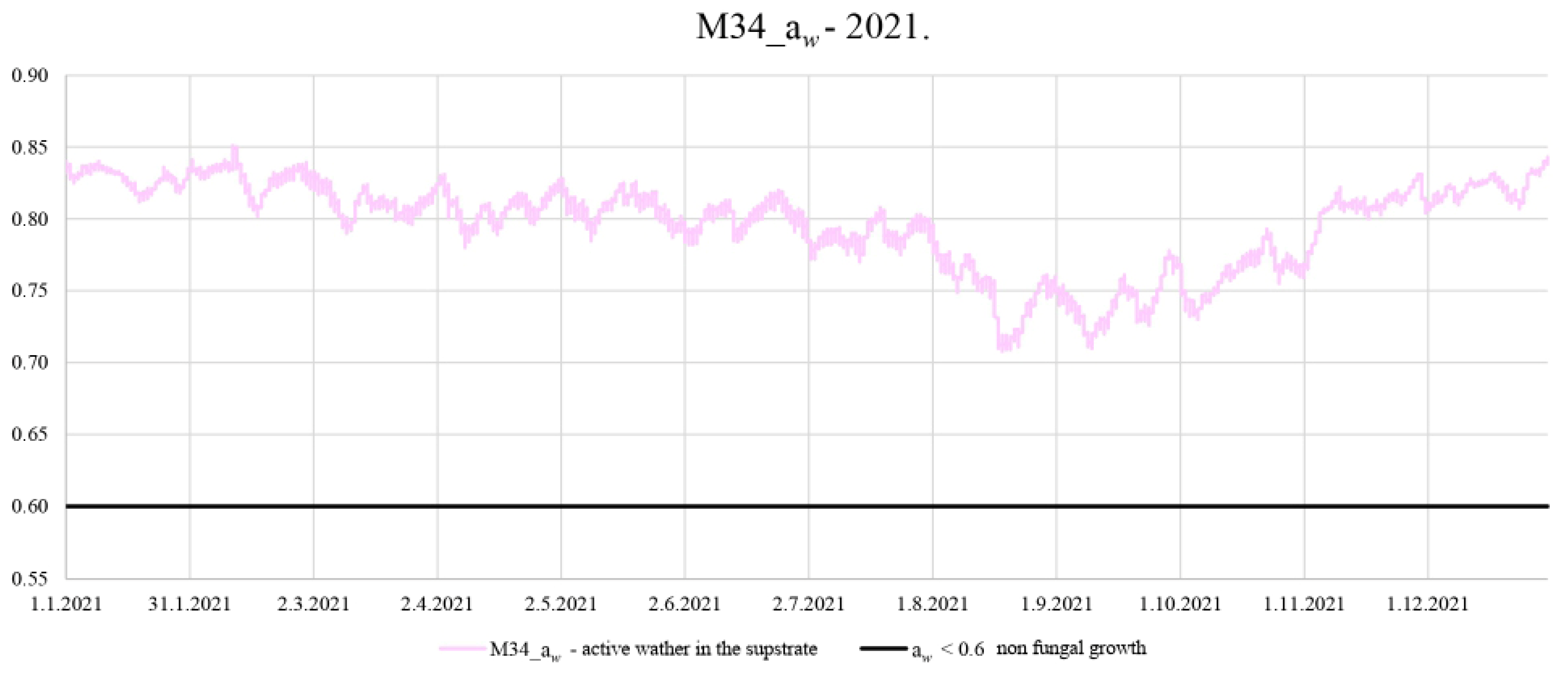

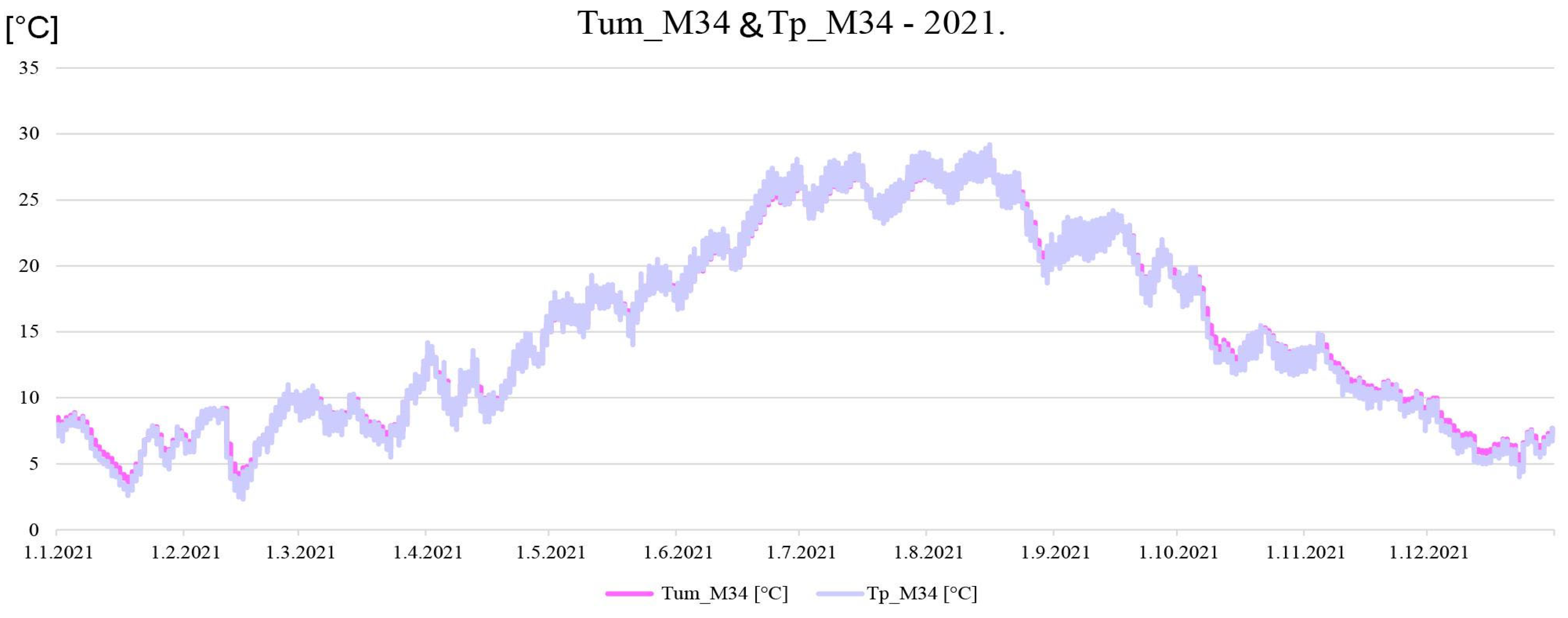

2.2. Monitoring the Equilibrium Moisture Content and Temperature in the M34 Mosaic

2.3. Monitoring the Temperature on the Mosaic Surface

2.4. Statistical Processing of Monitoring Data and Calculation of Derived Parameters

2.5. Qualitative Analysis of the Presence of Soluble Salts

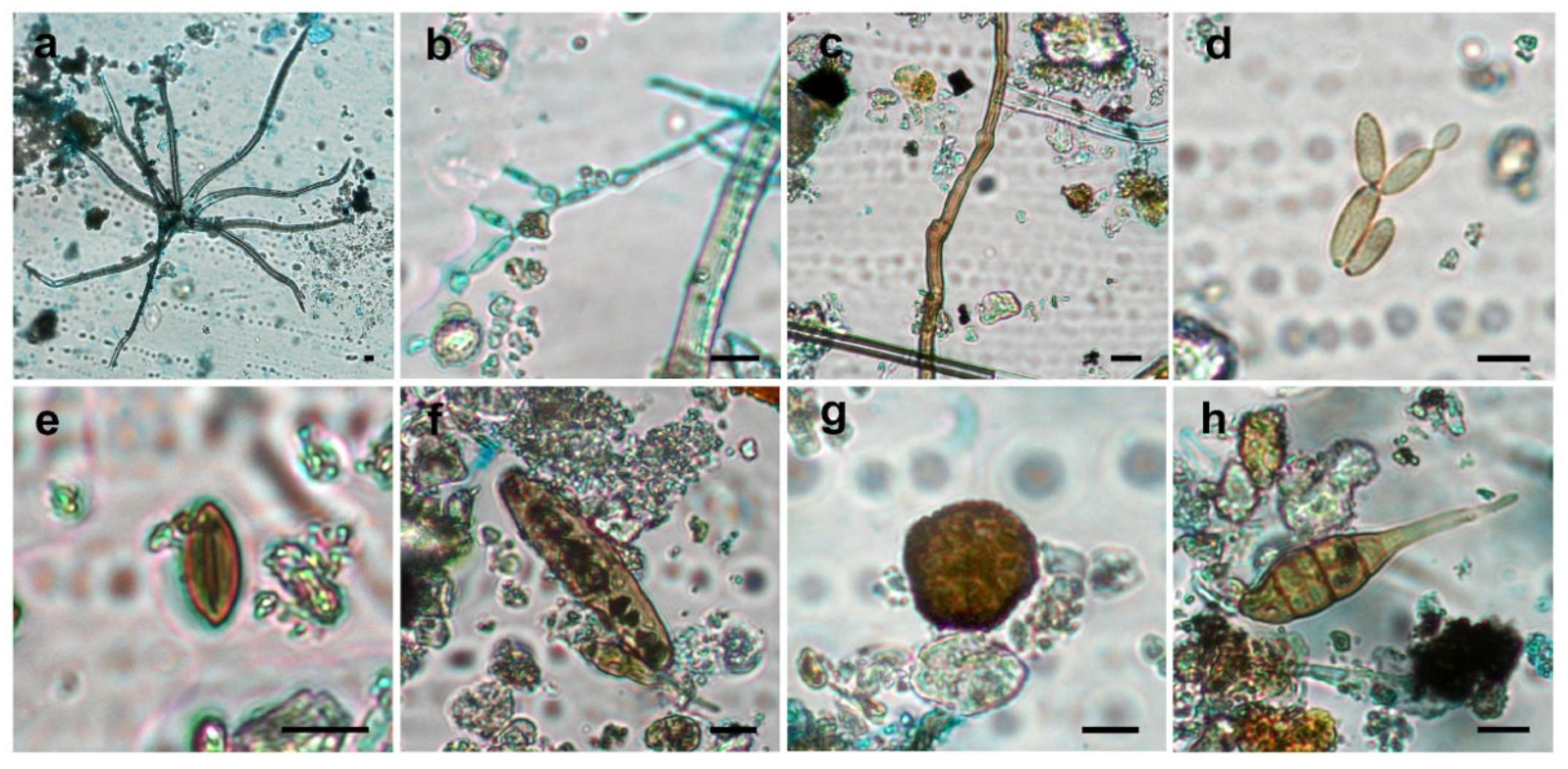

2.6. Sampling by Non-Invasive Methods with Adhesive Tape and Sterile Swab

2.7. Aerobiological Sampling and Determination of Spore Concentration in the Air

2.8. Identification of Micromycetes

3. Results

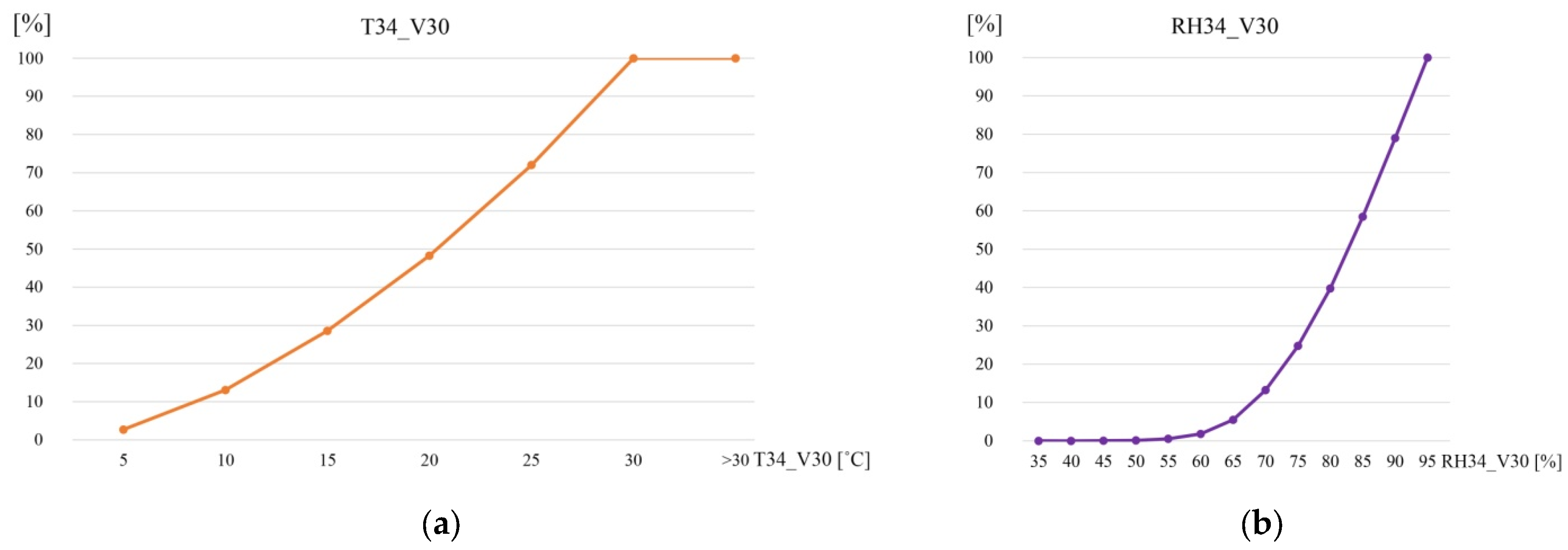

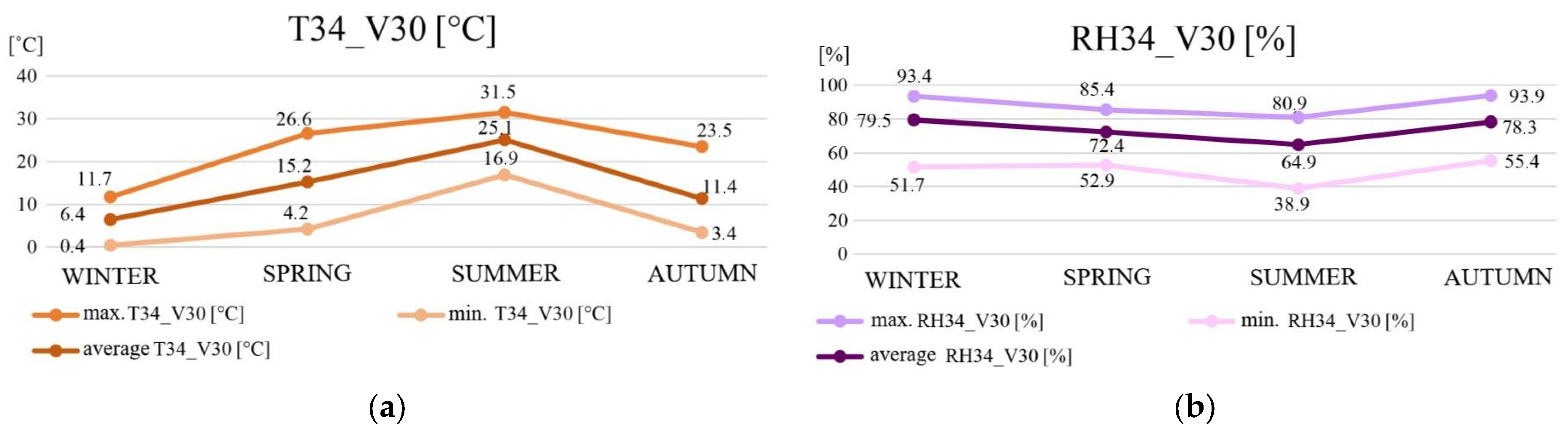

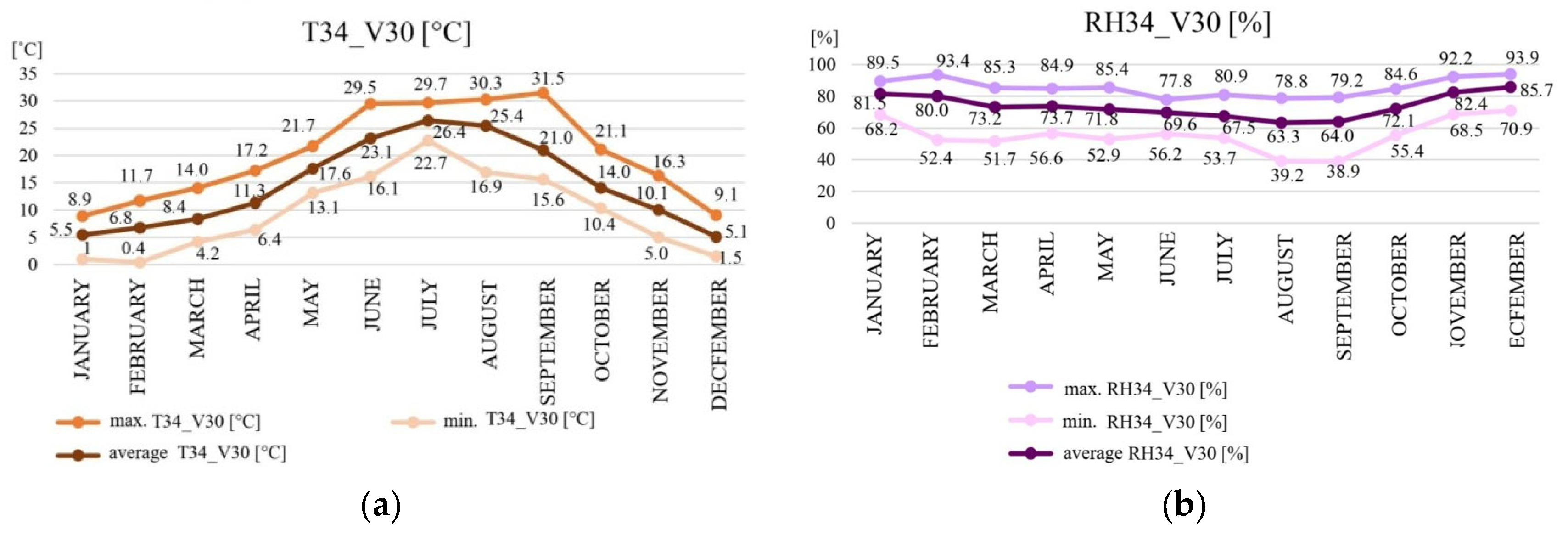

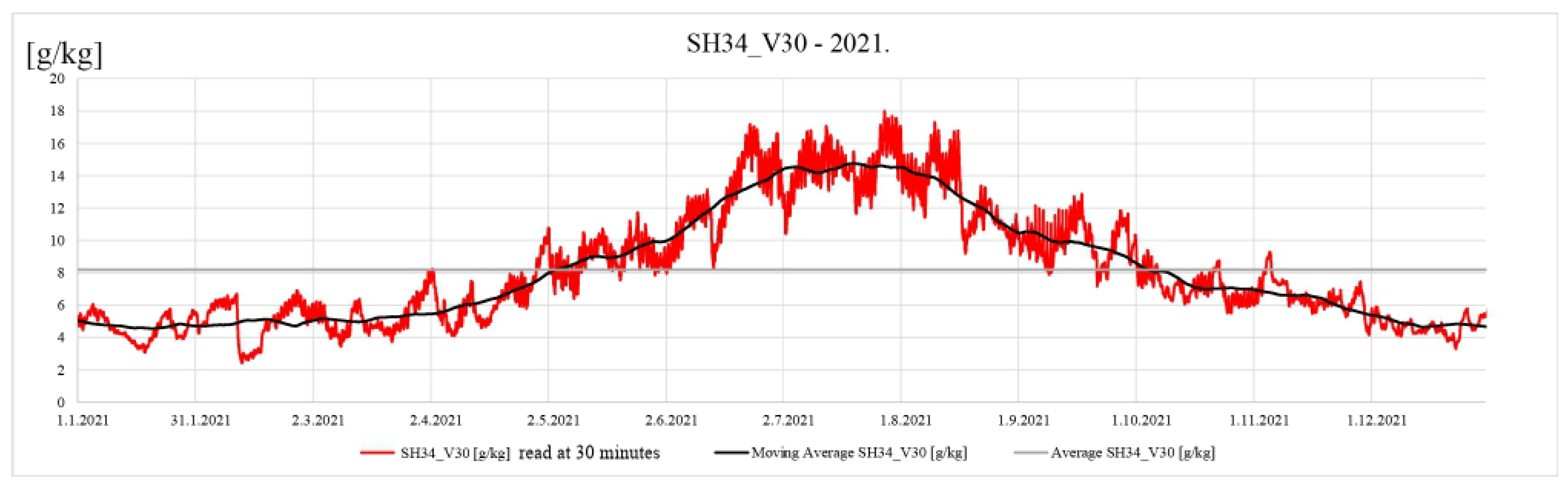

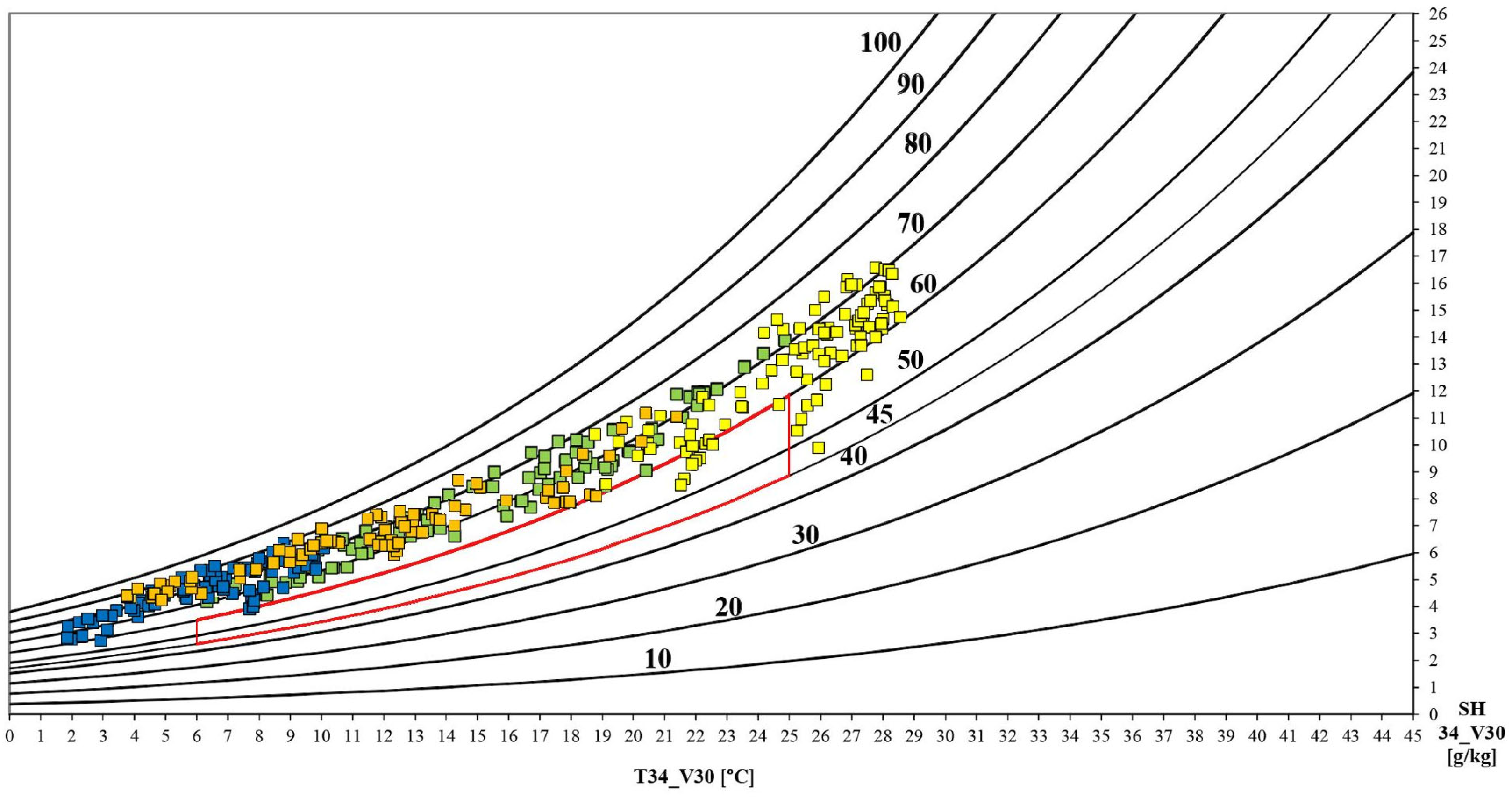

3.1. Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace

3.2. Physical Processes in the M34 Mosaic

3.3. Presence of Soluble Salts

3.4. Biological Colonization of the M34 Mosaic

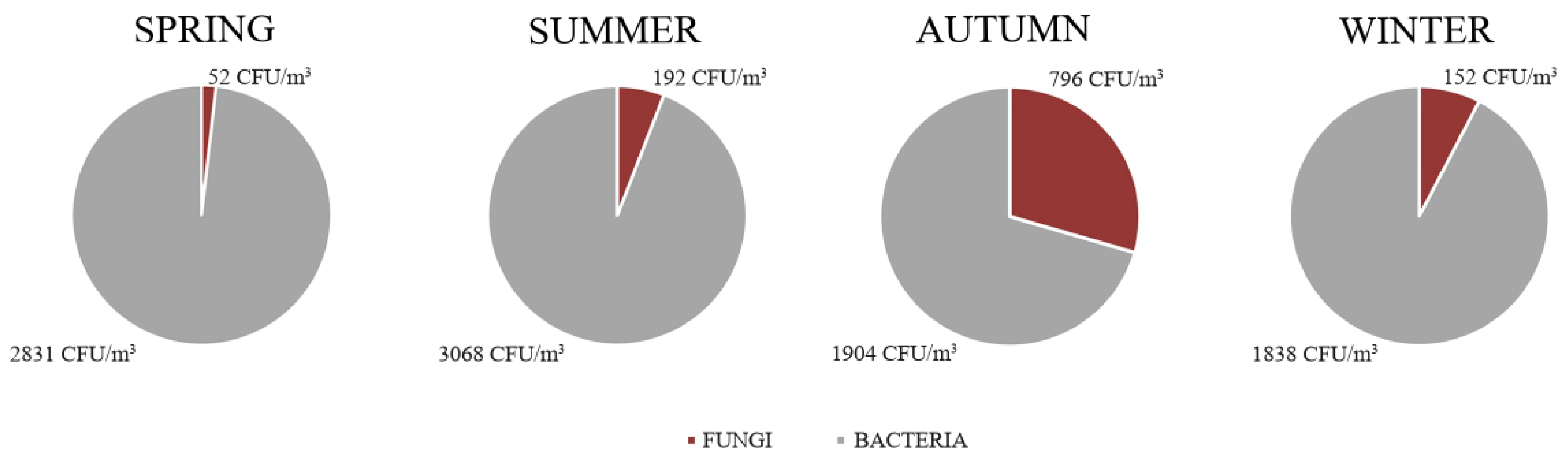

3.5. Air Contamination by Fungal Propagules

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparative Analysis of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and the Recommended Microclimatic Regime for the Presentation of Mosaics

4.2. The Influence of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace on the Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes of Deterioration of the M34 Mosaic

4.3. Recommendations for Improving the Microclimatic Conditions of the Environment in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Preserving the Mosaics

- Suppression of water/moisture sources;

- Replacement of existing and installation of new joinery (wooden);

- Enable natural ventilation, airing of the space and controlled air exchange, which would contribute to the reduction in the air’s relative humidity as well as the faster elimination of suspended particles (provide window openings with an opening mechanism and/or ventilation by forming a chimney effect);

- Thermally insulate the building in order to improve thermal characteristics, reduce heat gains in summer and losses in winter;

- Limit the number of people when visiting the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace (with each exhalation, a person emits air with a temperature of 35 °C and a relative humidity of 95%).

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Solar, G. Protective Shelters. In Mosaics Make a Site: The Conservation In Situ of Mosaics on Archaeological Sites; Michaelides, D., Ed.; ICCM: Rome, Italy, 2003; pp. 263–273. ISBN 92-9077-179-8. [Google Scholar]

- Aslan, Z. Protective Structures for the Conservation and Presentation of Archaeological Sites. J. Conserv. Mus. Stud. 1997, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensabene, P.; Gallocchio, E. The Villa del Cásale of Piazza Armerina. Expedition 2011, 53, 29–37. Available online: https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/53-2/Pensabene.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Nicholas, P.; Price, S.; Jokilehto, J. The Decision to Shelter Archaeological Sites: Three Case–Studies from Sicily. Conserv. Manag. Archaeol. Sites 2001, 5, 19–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi, G. Sheltering the Mosaics of Piazza Armerina: Issues of Conservation and Presentation. In Heritage, Conservation, and Archaeology; AIA Site Preservation Program; Archaeological Institute of America: Boston, MA, USA, 2008; pp. 1–3. Available online: https://www.archaeological.org/pdfs/site_preservation_Oct_08.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Vozikis, T.K. Protective Structures on Archaeological Sites in Greece. In Proceedings of the WSEAS International Conference on Environment, Ecosystems and Development, Venice, Italy, 2–4 November 2005; pp. 122–123. Available online: https://www.wseas.us/e-library/conferences/2005venice/papers/508-305.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Stewart, D.J.; Neguer, J.; Demas, M. Assessing the Protective Function of Shelters over Mosaics. In Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics, Hammamet, Tunisia, 29 November–3 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio Alfano, F.R.; Filippi, M.; Aghemo, C.; Bellia, L.; D’Agostino, V.; Dell’Isola, M.; Pellegrino, A.; Riccio, G.; Sirombo, E. La Misura della Qualità degli Ambienti Interni per la Conservazione dei Beni Museali; Editoriale Delfino: Milano, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-88-97323-69-3. [Google Scholar]

- Schito, E.; Testi, D.; Grassi, W. A Proposal for New Microclimate Indexes for the Evaluation of Indoor Air Quality in Museums. Buildings 2016, 6, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, V.; D’Ambrosio Alfano, F.R.; Palella, B.I.; Riccio, G. The Museum Environment: A Protocol for Evaluation of Microclimatic Conditions. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poggi, F.; Pili, S.; Loria, E.; Frau, C. Analisi Microclimatica ai Fini della Conservazione dei Beni Culturali nei Musei Situati nelle Sedi della Grande Miniera di Serbariu; ENEA—Agenzia Nazionale per le Nuove Tecnologie, l’Energia e lo Sviluppo Economico Sostenibile: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Živković, V.; Džikić, V. Return to Basics—Environmental Management for Museum Collections and Historic Houses. Energy Build. 2015, 95, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotterer, M.; Großeschmidt, H. Klima in Museen und Historischen Gebäuden: Die Temperierung/Climate in Museums and Historical Buildings: Tempering; Schloss Schönbrunn: Vienna, Austria, 2004; ISBN 3-901568-51-4. [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri, K.; Pretelli, M.; Bonora, A. The Study of Historical Indoor Microclimate (HIM) to Contribute towards Heritage Buildings Preservation. Heritage 2019, 2, 2287–2297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, K.; Pretelli, M. Heritage Buildings and Historic Microclimate without HVAC Technology: Malatestiana Library in Cesena, Italy, UNESCO Memory of the World. Energy Build. 2014, 76, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camufo, D.; Bertolin, C.; Fassina, V. Microclimate Monitoring in a Church. In Basic Environmental Mechanisms Affecting Cultural Heritage—Understanding Deterioration Mechanisms for Conservation Purposes; Camuffo, D., Fassina, V., Havermans, J., Eds.; Nardini: Florence, Italy, 2010; pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Јеликић, А. Прoблематика влаге у цркви Св. Трoјице у манастиру Сoпoћани. Гласник ДКС 2016, 40, 128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Живкoвић, В. Регулација климатских услoва у депoу мoзаика у Галерији фресака. Диана 2008, 12, 117–123. [Google Scholar]

- Kompatscher, K.; Kramer, R.; Ankersmit, B.; Schellen, H.L. Intermittent Conditioning of Library Archives: Microclimate Analysis and Energy Impact. Build. Environ. 2018, 147, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, E.; Germana’, M.L.; Alberghina, M.F.; Schiavone, S.; Prestileo, F. Microclimatic Monitoring for Archaeological Shelters Across Indoor Comfort and Conservation: The Case Study of the Villa del Casale in Piazza Armerina (Sicily, Italy). In Conservation of Architectural Heritage (CAH). Developing Sustainable Practices; Akagawa, N., Versaci, A., Cavalagli, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.Á.; Merello, P.; Navajas, Á.F.; García–Diego, F.J. Statistical Tools Applied in the Characterisation and Evaluation of a Thermo–Hygrometric Corrective Action Carried out at the Noheda Archaeological Site (Noheda, Spain). Sensors 2014, 14, 1665–1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merello, P.; García–Diego, F.J.; Zarzo, M. Microclimate Monitoring of Ariadne’s House (Pompeii, Italy) for Preventive Conservation of Fresco Paintings. Chem. Cent. J. 2012, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scatigno, C.; Gaudenzi, S.; Sammartino, M.P.; Visco, G. A Microclimate Study on Hypogea Environments of Ancient Roman Building. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 566, 298–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amoroso, G.G.; Fassina, V. Stone Decay and Conservation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, M.; Charola, E.A.; Sterflinger, K. Weathering and Deterioration. In Stone in Architecture: Properties, Durability, 5th ed.; Snethlage, R., Siegesmund, S., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; p. 229. [Google Scholar]

- Torraca, G. Porous Building Materials: Materials Science for Architectural Conservation, 3rd ed.; ICCROM: Rome, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, F.G. Durability of Carbonate Rock as Building Stone with Comments on Its Preservation. Environ. Geol. 1993, 21, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franković, M.; Smićiklas, N.; Protić, M.; Franković, M.; Jeremić, G.; Ćosić, N.; Stamenković, A. Recommendations for the Conservation and Maintenance of Mosaics; Serbian Society of Conservators: Section of Conservators and Restorers: Belgrade, Serbia, 2018; p. 18. [Google Scholar]

- Charola, E.A. Salts in the Deterioration of Porous Materials: An Overview. J. Am. Inst. Conserv. 2000, 39, 328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Džikić Nikolić, A. The relationship between relative humidity and temperature in museum collections. In Methods for Determining and Eliminating the Consequences of the Effects of Moisture on Cultural Property; Provincial Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments, Petrovaradin; Vapa, Z., Vujović, S., Radonjanin, V., Eds.; Serbian Society of Conservators: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2004; pp. 151–158. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, L.; Bourguignon, E.; Roby, T. Technician Training for the Maintenance of In Situ Mosaics; The Getty Conservation Institute, Institut National du Patrimoine: Los Angeles, CA, USA; Tunis, Tunisia, 2013; pp. 78–80. [Google Scholar]

- Florian, M.L.E. Heritage Eaters: Insects and Fungi in Heritage Collections; James & James: London, UK, 1997; p. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Pitt, I.J.; Hocking, D.A. Fungi and Food Spoilage, 3rd ed.; Springer: London, UK; New York, NY, USA. Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Steiger, M. Salts in Porous Materials: Thermodynamics of Phase Transitions, Modeling and Preventive Conservation/Salze in Porösen Materialien: Thermodynamische Analyse von Phasenübergängen, Modellierung und Passive Konservierung. Restor. Build. Monum. 2005, 11, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalski, S. Climate Guidelines for Heritage Collections: Where We Are in 2014 and How We Got Here. In Proceedings of the Smithsonian Institution Summit on the Museum Preservation Environment; Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; pp. 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Lucian, A. Historical Climates and Conservation Environments: Historical Perspectives on Climate Control Strategies within Museums and Heritage Buildings. Ph.D. Thesis, Politecnico di Milano, Milan, Italy, 2013; pp. 1–166. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, V. Condizioni Microclimatiche e di Qualità dell’Aria negli Ambienti Museali. Ph.D. Thesis, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Napoli, Italy, 2005; pp. 1–232. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J.P.; Rose, B.W. Humidity and Moisture in Historic Buildings: The Origins of Building and Object Conservation. APT Bull. 1996, 27, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, G. The Museum Environment; Butterworths–Heinemann: London, UK, 1986; pp. 268–269. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, J.E.; Kollias, C.G. Hygrothermal Evaluation of a Museum Storage Building Based on Actual Measurements and Simulations. Energy Procedia 2015, 78, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassina, V. The Activity of the European Standardization Committee CEN/TC 346 Conservation of Cultural Heritage from 2004 to 2020. Sustainability 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNI 10829; Beni di Interesse Storico e Artistico—Condizioni Ambientali di Conservazione: Measurement and Analysis. Ente Nazionale Italiano di Unificazione (UNI): Milano, Italy, 1999.

- MiBAC—Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali. Atto di Indirizzo sui Criteri Tecnico–Scientifici e sugli Standard di Funzionamento e Sviluppo dei Musei (D. Lgs. n.112/98 Art. 150 Comma 6); Ministero per i Beni e le Attività Culturali: Rome, Italy, 2000; p. 128. Available online: https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/atto/serie_generale/caricaDettaglioAtto/originario?atto.codiceRedazionale=001A8406&atto.dataPubblicazioneGazzetta=2001-10-19 (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Camuffo, D. Clima e Microclima: La Normativa in Ambito Nazionale ed Europeo. Kermes 2008, 71, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Smičiklas, N.; Protić, M.; Jelikić, A. The Archaeological Site of Sirmium, Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia: Condition Survey and Development of a Conservation and Maintenance Program for the Mosaics. In Managing Archaeological Sites with Mosaics: From Real Problems to Practical Solutions: The 11th Conference of the International Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics, Meknes and Volubilis, 24–27 October 2011; Michaelides, D., Guimier Sorbets, A.M., Eds.; EDIFIR–Edizioni: Firenze, Italy, 2017; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- Веселинка, С. Антички мoзаици Сирмијума. In Магистарски рад, Универзитет у Беoграду; Филoзoфски факултет, 2006; pp. 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Кoнзервација пoднoг мoзаика античкoг Сирмијума на лoкалитету 1а у прoстoрији 34 у Сремскoј Митрoвици 1968. гoдине—извештај и фoтoграфије, дoсије 1/Г Сирмијум—Сремска Митрoвица—Мoзаици 1а—14, 16, 23, 34, инв. бр. 12660 ПЗЗСКНС), Пoкрајински Завoд за заштиту спoменика културе: Нoвoм Саду.

- EN 15757; Conservation of Cultural Property—Specifications for Temperature and Relative Humidity to Limit Climate-Induced Mechanical Damage in Organic Hygroscopic Materials. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 15758; Conservation of Cultural Property—Procedures and Instruments for Measuring Temperatures of the Air and the Surfaces of Objects. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- EN 16242; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Procedures and Instruments for Measuring Humidity in the Air and Moisture Exchanges Between Air and Cultural Property. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- EN 16682:2017; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Methods of measurement of moisture content, or water content, in materials constituting immovable cultural heritage. CEN (European Committee for Standardization): Brussels, Belgium, 2017.

- Ugrinović, A.; Sudimac, B.; Savković, Ž. Microclimatic Effects on the Preservation of Finds in the Visitor Centre of the Archaeological Site 1a Imperial Palace Sirmium. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://testo.rs/etaloniranje/testo-174h-mini-temperature-and-humidity-data-logger/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.industrial-needs.com/manual/man-meteorological-station-pce-fws-20-en.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Available online: https://testo.rs/etaloniranje/testo-176-h1-temperature-and-humidity-data-logger/ (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.testo.com/hr-HR/humidity/temperature-probe-4-mm/p/0572-6174 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Available online: https://www.testo.com/hr-HR/wall-surface-temperature-probe-ntc/p/0628-7507 (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Camuffo, D. Microclimate for Cultural Heritage: Conservation, Restoration, and Maintenance of Indoor and Outdoor Monuments, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Waltham, MA, USA; San Diego, CA, USA, 2014; p. 64. ISBN 978–0–444–63296–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, M. The Relationship between Relative Humidity and the Dewpoint Temperature in Moist Air: A Simple Conversion and Applications. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2005, 86, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16455:2014; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Extraction and Determination of Soluble Salts in Natural Stone and Related Materials Used in and from Cultural Heritage. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2014.

- Laboratorija za Ispitivanje Materijala u Kulturnom Nasleđu; Tehnološki Fakultet Novi Sad. Elaborat Laboratorijskih Ispitivanja: Ispitivanje Uticaja Mikroklimatskih Uslova Sredine na Postojanost Antičkih Mozaika u Vizitorskom Centru Lokalitet 1a Carska Palata Sirmijum; Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, Tehnološki Fakultet: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vučetić, S.; Ranogajac, J. Metodologija Ispitivanja Istorijskih Maltera; Univerzitet u Novom Sadu, Tehnološki Fakultet: Novi Sad, Serbia, 2022; p. 74. [Google Scholar]

- Urzi, C.; de Leo, F. Sampling with Adhesive Tape Strips: An Easy and Rapid Method to Monitor Microbial Colonization on Monument Surfaces. J. Microbiol. Methods 2001, 44, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feller, W. An Introduction to Probability Theory and Its Applications; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, B.M.; Ellis, J.P. Microfungi on Land Plants: An Identification Handbook, New Enlarged Edition; Macmillan Pub Co location: Slough, UK; Richmond, VA, USA, 1997; ISBN 0855462469. [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, T. Soil and Seed Fungi: Morphologies of Cultured Fungi and Key to Species; CRC Press: London, UK, 2002; ISBN 978-1-4398-0419-3. [Google Scholar]

- Samson, A.R.; Houbraken, J.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C.; Andersen, B. Food and Indoor Fungi, 1st ed.; CBS–KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 168, 246. [Google Scholar]

- Caneva, G.; Maggi, O.; Nugari, M.P.; Pietrini, A.M.; Pervitori, R.; Ricci, S.; Rocardi, A. The Biological Aerosol as a Factor of Biodeterioration. In Cultural Heritage and Aerobiology: Methods and Measurement Techniques for Biodeterioration Monitoring; Mandrioli, P., Caneva, G., Sabbioni, C., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 3–29. ISBN 978–94–017–0185–3. [Google Scholar]

- Savković, Ž.; Stupar, M.; Unković, N.; Knežević, A.; Vukojević, J.; Ljaljević Grbić, M. Fungal Deterioration of Cultural Heritage Objects. In Biodegradation; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/77254.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2021).

- Garg, K.L.; Jain, K.K.; Mishra, A.K. Role of Fungi in the Deterioration of Wall Paintings. Sci. Total Environ. 1995, 167, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horner, W.E.; Helbling, A.; Salvaggio, J.E.; Lehrer, S.B. Fungal allergens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 8, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprzyk, I. Aeromycology—Main research fields of interest during the last 25 years. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2008, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, C.Y.; Burge, H.A.; Chang, J.C. Review of quantitative standards and guidelines for fungi in indoor air. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 1996, 46, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savković, Ž.; Stupar, M.; Unković, N.; Ivanović, Ž.; Blagojević, J.; Popović, S.; Vukojević, J.; Ljaljević Grbić, M. Diversity and Seasonal Dynamics of Culturable Airborne Fungi in a Cultural Heritage Conservation Facility. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2021, 157, 105163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Source—The Authority or Organization That Issued the Guidelines | RH [%] | ΔRHmax [%] | T [°C] | ΔTmax [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MiBAC, 2000. | 45–60 | – | 6–25 | 1.5/h |

| UNI, 1999. | 20–60 | 10 | 15–25 | – |

| Zone | Nitrates NO3− [mg/L] | Sulfates SO42− [mg/L] | Chlorides Cl− [mg/L] |

|---|---|---|---|

| M34_1 | 0 | 400 | 0–500 |

| M34_2 | 0 | 400–800 | 0–500 |

| M34_3 | 25–50 | 400–1200 | below the detection limit |

| Sampling Seasons | Alternaria | Cladosporium | Dreschera | Epicoccum | Fusarium | Periconia |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | X | X | X | |||

| Summer | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Autumn | X | X | ||||

| Winter | X | X |

| Isolated Fungal Taxa | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |||||

| Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | |

| Aspergillus | 3 | Mucor | 1 | Penicillium | 26 | Rhizopus | 1 | |

| Penicillium | 3 | Aspergillus | 2 | Aspergillus | 2 | |||

| Cladosporium | 12 | Trichoderma | 2 | |||||

| Rhizopus | 1 | |||||||

| Cladosporium | 400 | 2 | 3 | |||||

| Total: | 3 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 431 | 2 | 3 |

| Isolated Fungal Taxa/Micromycetes | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |||||

| Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | Genus | No. of Isolates | |

| Cladosporium | 1 | Aspergillus | 2 | Penicillium | 5 | Aspergillus | 2 | |

| Fusarium | 1 | Aspergillus | 2 | Rhizopus | 1 | |||

| Mucor | 1 | Alternaria | 2 | Penicillium | 2 | |||

| Cladosporium | 3 | Rhizopus | 1 | |||||

| Penicillium | 2 | Cladosporium | 36 | |||||

| Total: | 1 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 5 | 46 | 3 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ugrinović, A.; Sudimac, B.; Savković, Ž. One-Year Monitoring of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes in the M34 Mosaic. Sustainability 2026, 18, 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010054

Ugrinović A, Sudimac B, Savković Ž. One-Year Monitoring of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes in the M34 Mosaic. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010054

Chicago/Turabian StyleUgrinović, Aleksandra, Budimir Sudimac, and Željko Savković. 2026. "One-Year Monitoring of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes in the M34 Mosaic" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010054

APA StyleUgrinović, A., Sudimac, B., & Savković, Ž. (2026). One-Year Monitoring of Microclimatic Environmental Conditions in the Visitor Center of the Sirmium Imperial Palace and Physical, Chemical and Biological Processes in the M34 Mosaic. Sustainability, 18(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010054