1. Introduction

Agricultural Heritage Systems (AHS) represent quintessential “socio-ecological” production landscapes that have remained functional for centuries or even millennia. This enduring resilience stems from their inherent stable and sustainable mechanisms, operating across multiple dimensions—primarily economic, ecological, and social [

1]. These multifaceted pillars enable AHS to perform not only sustainable production functions but also roles beyond production, such as ecological conservation, cultural inheritance, and social cohesion. This multifunctionality manifests externally as multiple values spanning economic, ecological, socio-cultural, and livelihood domains [

2,

3,

4]. AHS are thus of paramount importance in addressing major global challenges, including ensuring food security, protecting biodiversity, combating climate change, and safeguarding cultural diversity [

5,

6], thereby contributing to the implementation of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

7].

However, the ongoing advancement of urbanization and modernization has led to the gradual abandonment of traditional agriculture by farmers, driven by factors such as its relatively low comparative efficiency [

8]. This trend has resulted in labor resource depletion, changes in traditional farming practices, and the erosion of agricultural culture at numerous AHS sites [

9]. Consequently, reconciling the conservation of traditional agricultural production with the imperative of ensuring sustainable livelihoods for farmers has emerged as a core challenge in the sustainable development of AHS [

10,

11]. In response, dynamic conservation approaches, conceptualized based on the multifunctional value and living nature of traditional agriculture, are considered effective strategies for balancing these dual objectives. These approaches primarily encompass the development of eco-agricultural products, the promotion of sustainable tourism, and the fostering of industrial integration [

12]. Nevertheless, the certification of eco-agricultural products in AHS sites often encounters low farmer participation, attributable to the transition period from conventional to ecological practices during which farmer incomes cannot be guaranteed [

13]. The development of AHS tourism frequently compromises farmer interests due to inadequate participation mechanisms [

14]. Similarly, while the impact of integrated development in traditional agriculture on farmer participation and benefits has been extensively theorized, it remains under-explored empirically [

15]. Some studies and practical experiences even indicate that AHS conservation can negatively impact farmers’ livelihoods due to factors such as unreasonable development and utilization [

16]. Therefore, determining how to fully leverage the multifunctional value of AHS to enhance farmers’ sustainable livelihoods has become a critical and urgent issue.

Tea-AHS refers to agricultural heritage systems centered on tea-planting, integrating tea culture throughout the entire process of production, processing, and consumption [

17]. These systems are directly linked to tea cultivation and production, with tea leaves being their primary output. Tea-AHS has become a significant category within AHS, recognized for its outstanding economic and livelihood value. First, many tea culture systems embody the core values of AHS, leading to their designation as either China’s Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (NIAHS) or FAO’s Globally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (GIAHS). Specifically, China hosts 23 Tea-NIAHSs and 4 Tea-GIAHSs, while there are 6 Tea-GIAHSs worldwide [

18,

19]. These systems share similar and well-defined key elements, most notably a strong reliance on farmer participation [

20]. Second, as a cash crop, tea offers relatively higher returns compared to grain crops. In Tea-GIAHS sites, farmers typically manage tea plantations on a relatively large scale, which constitutes their primary livelihood source. Finally, the tea industry generally encompasses multiple segments—including cultivation, processing, sales, and consumption—forming a relatively long value chain. This allows farmers in Tea-GIAHS sites to engage simultaneously in multiple segments [

21].

Farmers’ sustainable livelihoods serve as a primary criterion for evaluating AHS conservation, with extensive research examining the impact of such conservation efforts on livelihoods. In existing literature, AHS conservation primarily refers to the nomination of sites, their official designation, and the implementation of dynamic conservation measures [

22]. The identification of AHS sites can promote county-level economic development by advancing grain processing industries, improving infrastructure, building AHS brand recognition, and fostering agricultural economic entities [

23,

24]. Furthermore, it enhances rural residents’ income levels through increased non-agricultural employment, industrial integration, agricultural technological advancement, the development of agricultural entities, and AHS brand building [

25,

26]. Additionally, AHS conservation strengthens agricultural resilience by leveraging rural financial support and attracting industrial and commercial capital to rural areas [

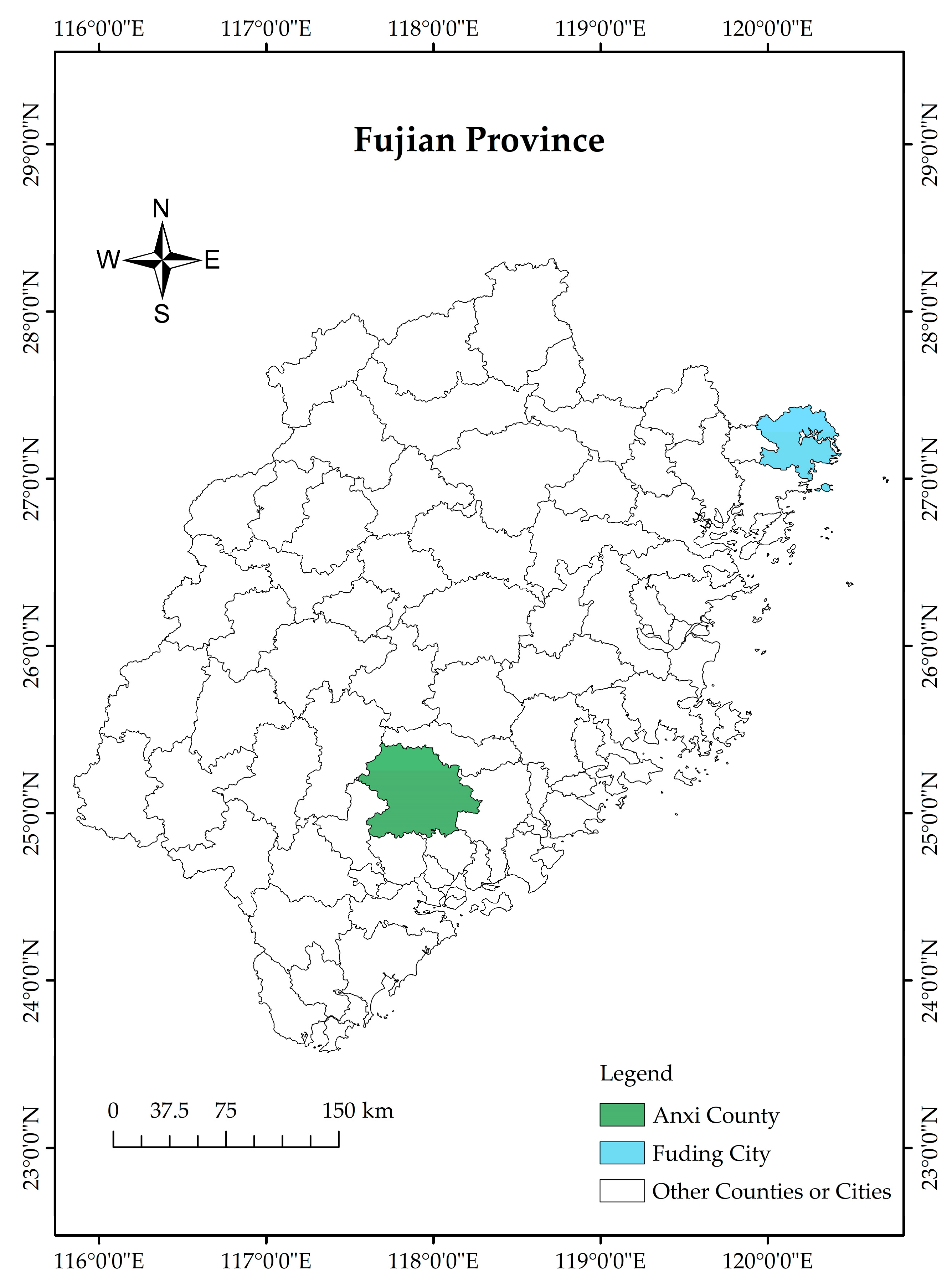

27]. However, most previous studies have focused on single dimensions or specific indicators—such as livelihood capitals, income, or well-being—rather than providing a holistic assessment of farmers’ sustainable livelihoods levels within AHS sites. Moreover, existing research has primarily investigated the influence mechanisms of AHS conservation on rural residents’ income from a macro perspective, with limited evidence from micro-level analyses. Therefore, this study focuses on farmers from two Tea-GIAHS sites—the Anxi Tieguanyin Tea Culture System (ATTCS) and the Fuding White Tea Culture System (FWTCS) in Fujian Province, China. Employing mediating effect models, it examines the mechanism through which AHS conservation influences farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, aiming to provide theoretical and practical support for formulating effective AHS conservation and development policies. Compared to existing research, the marginal contributions of this paper are twofold. First, it offers a multidimensional and systematic assessment of farmers’ sustainable livelihoods in AHS sites. Second, it investigates the specific pathway through which AHS conservation enhances farmers’ sustainable livelihoods.

4. Results

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 6 reports the impacts of participating in Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods and its three dimensions. The coefficient of determination (R

2) for each model ranges from 0.2 to 0.6, indicating that the selected independent variables adequately explain a substantial portion of the variation in the dependent variables.

Column (1) considers only the core variable of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation. The coefficient of 0.040 (significant at the 1% level) provides an initial, uncontrolled estimate of its positive impact. Column (2) incorporates control variables for individual, household, and village characteristics. The coefficient for participation decreases to 0.031 but remains significant at the 1% level. This refinement indicates that approximately 22.5% of the initial estimate was attributable to correlated observable factors, and failing to account for these characteristics would overestimate the effect of Tea-GIAHS participation. The results confirm that Tea-GIAHS conservation effectively promotes improvements in farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, thereby validating Hypothesis 1.

To interpret the practical significance, we consider the estimated coefficient of 0.031 for participation (FP) in the full model of Column (2). Given that the dependent variable (SL) is a standardized index with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1, a coefficient of 0.031 implies that participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation increases a household’s sustainable livelihoods index by 0.031 standard deviations, ceteris paribus.

Decomposing the overall sustainable livelihoods index into its three dimensions—livelihood capitals, strategies, and outcomes—columns (3)–(5) reveal that Tea-GIAHS conservation exerts a significant positive impact on all three aspects. The strongest association is with livelihood strategies, followed by livelihood outcomes and livelihood capitals, with coefficients of 0.107, 0.043, and 0.030, respectively. The impact on the sub-dimensions is particularly noteworthy for farmers’ livelihood strategies (Column 4), suggests that Tea-GIAHS participation is a major driver of shifts towards more sustainable and diversified livelihood strategies.

Regarding the control variables, households with older heads show a small but statistically significant reduction in sustainable livelihoods levels. The gender of the household head (where male = 1) shows a positive association with sustainable livelihoods. Households with members serving as village officials exhibit significantly higher sustainable livelihoods levels. The effects of the child-rearing and elderly support ratio (family dependency ratio) are generally insignificant, as many elderly individuals in the Tea-GIAHS sites remain economically active in tea production and childcare. Furthermore, larger household sizes contribute positively to sustainable livelihoods, likely due to enhanced labor availability and resilience to risks. In terms of village characteristics, both higher village economic development and closer proximity to towns are correlated with higher levels of household sustainable livelihoods, emphasizing the importance of external economic and market access.

4.2. Mechanism Tests

Building upon the baseline regression results, we employed Models 2 and 3 to examine the respective mechanisms through which the scaling and industrialization of agricultural operations influence the relationship between participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation and farmers’ sustainable livelihoods. The regression results are presented in

Table 7, where columns (1) and (3) display the results from Model 2, and columns (2) and (4) show the results from Model 3.

As shown in Column (1) of

Table 7, participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation exerts a significant positive effect on the scaling of agricultural operations, with a coefficient of 0.084 significant at the 1% level. This suggests that Tea-GIAHS conservation effectively facilitates the expansion of farmers’ agricultural activities. Column (2) reveals that participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation also has a statistically significant effect on sustainable livelihoods at the 1% level. Moreover, the scaling of agricultural operations is positively associated with farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, showing a coefficient of 0.060, which is also significant at the 1% level. These results indicate that the scaling of agricultural operations serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation and farmers’ sustainable livelihoods. Specifically, Tea-GIAHS conservation can enhance farmers’ sustainable livelihoods by promoting agricultural expansion, thereby providing empirical support for Hypothesis 2.

As presented in Column (3) of

Table 7, participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation has a significant positive impact on the industrialization of agricultural operations, with a coefficient of 0.063 significant at the 1% level. This implies that Tea-GIAHS conservation effectively facilitates the industrialization process of farmers’ agricultural activities. Furthermore, Column (4) indicates that participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation remains significantly associated with farmers’ sustainable livelihoods at the 1% level. Additionally, the industrialization of agricultural operations exhibits a positive effect on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, with a coefficient of 0.165, also significant at the 1% level. These results suggest that the industrialization of agricultural operations serves as a partial mediator in the relationship between participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation and farmers’ sustainable livelihoods. In other words, Tea-GIAHS conservation can enhance farmers’ sustainable livelihoods by promoting agricultural industrialization, thereby providing support for Hypothesis 3.

4.3. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.3.1. Heritage Sites

To further examine whether the impact of AHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods differs across AHS sites, this study conducted regression analyses separately for the ATTCS and the FWTCS sites. The results presented in

Table 8.

As shown in

Table 8, the estimated coefficient of the impact of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods is 0.034 in both heritage sites, significant at the 1% level. This indicates that the overall effect of Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods does not differ significantly between the two sites, supporting the robustness of treating them as comparable tea-related GIAHS in the main analysis. The ATTCS and the FWTCS in Fujian Province are typical representatives of oolong and white Tea-GIAHS, respectively. While there are similarities and differences in conservation models and policies between the two systems, the effects of heritage policies are generally comparable.

When examined by dimension, the influence of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers’ livelihood capitals and livelihood strategies shows little variation between the two sites. However, its impact on livelihood outcomes differs more noticeably, with coefficients of 0.046 for the ATTCS and 0.028 for the FWTCS. This disparity is primarily attributed to the fact that the Anxi Tieguanyin tea industry has a longer development history, larger scale and production volume, and a more complete industrial chain encompassing cultivation, processing, and sales. Consequently, farmers in the ATTCS are more likely to benefit from participating in heritage conservation, thereby achieving higher income and well-being.

4.3.2. Livelihood Levels

To investigate the impact of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers with varying levels of sustainable livelihoods, this study draws on the methodology employed in relevant research [

62], while accounting for sample size limitations. Households were classified into high-level and low-level sustainable livelihoods groups based on the median value of sustainable livelihoods, and separate regressions were performed for each group. The results are reported in

Table 9.

As farmers’ sustainable livelihoods level increases, the estimated coefficient for participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation also becomes larger. This suggests that farmers with higher sustainable livelihoods levels are more likely to benefit from engaging in Tea-GIAHS conservation, whereas those with lower levels find it difficult to gain similar advantages. Tea-GIAHS conservation exhibits a “Matthew effect” in enhancing sustainable livelihoods for farmers. The disparity arises because farmers with greater livelihood assets are better positioned to participate in and benefit from conservation activities, owing to more developed capabilities and favorable conditions. In contrast, farmers with lower sustainable livelihoods often face constraints such as traditional farming techniques and limited experience, which hinder their ability to achieve meaningful benefits from participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation.

4.3.3. Income Levels

The capacity of households at different income levels to access and utilize AHS resources may vary. Accordingly, we further examine how participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation affects the sustainable livelihoods of households across income brackets. Based on median annual household income, sample households are divided into high-income and low-income groups. The variable “income level” is defined as 1 for the high-income group and 0 for the low-income group. Model 1 incorporates an interaction term between participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation and income level, and the regression results are presented in

Table 10.

As shown in Column (1), the interaction coefficient between farmers’ participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation and income level is positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, indicating that Tea-GIAHS conservation has a stronger positive effect on the sustainable livelihoods of high-income farmers compared to their low-income counterparts. Similarly, the interaction term coefficients in columns (2) and (4) are also significantly positive at the 1% level, suggesting that Tea-GIAHS conservation enhances both livelihood capitals and livelihood outcomes more markedly for high-income farmers. This disparity may be attributed to the fact that higher-income households are more likely to participate in Tea-GIAHS conservation, possess higher educational attainment, engage more actively in conservation activities, and have access to more abundant heritage resources. As a result, Tea-GIAHS conservation exerts a more substantial impact on these households, leading to greater improvements in sustainable livelihoods.

In contrast, although the interaction term in Column (3) is positive, it is not statistically significant. This implies that the effect of Tea-GIAHS conservation on improving livelihood strategies does not differ significantly between high-income and low-income households. A possible explanation is that households within Tea-GIAHS sites tend to choose livelihood strategies based on a broader assessment of their individual conditions, policy support, and other contextual factors, where income level may not play a decisive role.

4.3.4. Livelihood Types

Households with different types of livelihoods are likely to engage in AHS conservation through distinct approaches. Accordingly, this paper assesses the impact of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation on the sustainable livelihoods of households classified by livelihood type. Building upon the methodology employed in prior research practices [

67], households are categorized as either agricultural or non-agricultural based on whether agricultural income accounts for at least 50% of total household income. Regression analyses were performed separately for each group, and the results are presented in

Table 11.

As shown in

Table 11, participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation exerts a significant positive impact on the sustainable livelihoods of both livelihood types. Notably, the estimated coefficient is larger for agricultural households and is statistically significant at the 1% level, suggesting that Tea-GIAHS conservation plays a more pronounced role in enhancing their sustainable livelihoods compared to non-agricultural households. This difference can be attributed to the fact that agricultural households typically possess richer traditional agricultural resources and knowledge, allowing them to derive greater benefits from participating in Tea-GIAHS conservation and thereby achieve more substantial improvements in sustainable livelihood outcomes.

4.4. Endogeneity Test

Participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation may enhance the sustainable livelihoods of farmers, while improved sustainable livelihoods could further encourage participation, creating a potential bidirectional relationship indicative of endogeneity. To address this, we employ an IV approach.

The instrument is “farmers’ self-assessed level of mastery regarding the professional knowledge and basic skills required for participating in heritage conservation.” Theoretically, this variable is closely related to actual participation, as involvement in conservation activities depends on relevant competency. Regarding exogeneity, we argue that as a perceptual measure specific to conservation capability, it aligns with the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) constructs of perceived behavioral control and attitude. Empirical studies grounded in TPB consistently show that such cognitive factors directly shape behavioral intention and subsequent action (e.g., participation in conservation practices), but their effect on final socio-economic outcomes (e.g., livelihood welfare) is channeled primarily through the enacted behavior itself, rather than through other direct pathways [

68]. For instance, knowledge influences technology adoption, which in turn affects productivity and income, with no significant direct effect of knowledge on income once adoption behavior is accounted for [

69]. Therefore, after controlling for observable covariates (e.g., basic household characteristics, village features), we contend that any potential correlation between our instrument and the error term—stemming from unobserved factors like innate ability—is minimal. This is because such latent traits are theorized to express themselves through, and thus be captured by, the participation behavior variable. Consequently, the instrument can be reasonably assumed to satisfy the exogeneity condition for identifying the causal effect of conservation participation on sustainable livelihoods.

As shown in columns (2) and (3) of

Table 12, the first-stage regression results using the instrumental variable indicate a statistically significant positive effect of the instrument on farmers’ participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation (

p < 0.01), confirming that the instrumental variable satisfies the relevance condition. Moreover, the first-stage F-statistic is 120.63, rejecting the null hypothesis of a weak instrument. The Cragg-Donald Wald F-statistic of 119.511 exceeds the 10% critical value of 16.38, and the Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistic of 10.910 is significant at the 1% level, further supporting the absence of a weak instrument problem. With only one instrumental variable, there is no need to examine the issue of over-identification. Compared with the baseline regression results in column (1) without instrumental variables, the IV estimates show that the coefficient of participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation on sustainable livelihoods increases from 0.031 to 0.049. After accounting for endogeneity, participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation continues to exhibit a statistically significant positive impact on sustainable livelihoods, reinforcing the conclusion that such involvement enhances farmers’ sustainable livelihood outcomes.

4.5. Robustness Tests

To ensure the reliability of the findings, we conducted robustness checks by modifying the measurement approaches of both the dependent and core independent variables, as well as by replacing the core independent variable. The results, presented in

Table 13, consistently support the main conclusions.

First, the measurement method of the dependent variable was altered. While the entropy method was initially used to quantify the sustainable livelihoods indicators, PCA was additionally employed as an alternative approach to re-quantify these indicators. As shown in column (1), participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation remains significantly and positively associated with farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, corroborating the initial results.

Second, the quantification method for the core independent variable was modified. Originally calculated using the arithmetic mean method, the variable “participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation” was re-quantified using the entropy method to maintain comparability and enhance validity. The results in column (2) confirm that the positive effect persists, further validating the robustness of the estimated relationship.

Finally, the core independent variable was replaced altogether. Instead of using individual household participation, the enthusiasm of the village committee toward Tea-GIAHS conservation was adopted as a proxy, considering the critical role of grassroots entities in conservation efforts and their broader impact on household livelihoods. As illustrated in column (3), this variable also exhibits a significant positive effect on sustainable livelihoods, confirming that the main findings are not sensitive to variable selection.

In summary, all three robustness tests reinforce the empirical conclusions of this study, affirming that participation in Tea-GIAHS conservation has a robust and positive influence on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods.

5. Discussion

Based on a comparative analysis of how AHS conservation affects farmers’ sustainable livelihoods in two distinct tea-related AHS sites—the ATTCS and the FWTCS [

53]—this study validates and elaborates the mechanisms through which Tea-GIAHS conservation influences livelihood sustainability. The findings not only confirm but also extend previous understandings in several key aspects, offering insights that invite comparison with other AHS types.

First, consistent with the broader literature on AHS livelihoods [

32], Tea-GIAHS conservation demonstrates a significant positive impact on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods. This study advances the discussion by operationalizing sustainable livelihoods through a comprehensive, three-dimensional framework—encompassing livelihood capitals, strategies, and outcomes—thereby enhancing the indicator’s scope and general applicability for future research.

Second, the analysis identifies the scaling-up and industrialization of traditional tea production as a core mechanism through which Tea-GIAHS conservation enhances livelihoods. This supports existing research highlighting scaling and industrialization as vital pathways for AHS sustainability [

15,

43]. A fruitful avenue for further discussion lies in comparing this mechanism with those observed in other AHS types. For instance, while tea culture systems may leverage product branding and vertical integration, paddy-field systems (e.g., rice-fish co-culture) might emphasize ecological synergies and landscape-based tourism [

70], and folk-custom-based systems could rely more on cultural performance and artisan craftsmanship. Such a cross-type comparison would help clarify whether the drivers of livelihood improvement are context-specific or share commonalities across different AHS categories. These comparative insights carry direct implications for international GIAHS policy, suggesting that policy support could be categorized and tailored—for instance, facilitating market access and Geographical Indication (GI) branding for product-based systems like tea, promoting agro-ecotourism partnerships for landscape-based systems, and safeguarding intellectual property for craft and performance-based systems [

71,

72]. This advocates for a more typology-sensitive approach within the global GIAHS support framework.

Finally, this study effectively addresses a common methodological limitation noted in prior AHS case studies—often constrained by small sample sizes that hinder robust heterogeneity analysis [

11]. By integrating survey data from two major Tea-GIAHS sites, we not only reveal significant differential impacts of conservation on distinct farmer subgroups but also provide a more reliable empirical basis for exploring the factors shaping livelihood sustainability. This approach offers a replicable model for future multi-site comparative research within and across different AHS typologies.

However, this study also has some limitations. First, research on other influence mechanisms and the heterogeneity of AHS conservation’s effects on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods remains insufficient. Beyond the scaling and industrialization of agricultural operations, conservation efforts may influence farmers’ sustainable livelihoods through other channels, such as agricultural production factor allocation [

73] and agricultural management models [

74]. Similarly, beyond livelihood status, income levels, and livelihood types, heterogeneity may also exist in other dimensions, such as labor force quality [

75].

Second, the cross-sectional design adopted in this study imposes inherent limitations on causal inference. While we employ an IV approach to mitigate potential endogeneity concerns—such as reverse causality or omitted variables—the findings should be interpreted as robust associations rather than conclusive causal evidence. In addition, our chosen IV—farmers’ assessment of their mastery of basic knowledge and professional skills for conservation participation—may itself correlate with other unobserved livelihood attributes (e.g., intrinsic ability, social capital, or entrepreneurial motivation) that could also influence livelihood outcomes, potentially introducing residual confounding [

76]. Therefore, future research using longitudinal data, panel surveys, or natural experimental designs would help to further validate the mechanisms and strengthen causal interpretation.

Third, research on the long-term influence mechanisms of AHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods remains limited. As in previous studies, this research uses cross-sectional data to examine short-term influence mechanisms. Since short-term and long-term mechanisms may differ, further exploration of the long-term impacts is warranted.

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

This study utilizes survey data collected from households in two Tea-GIAHS sites during the fifth year following their designation. By quantifying farmers’ sustainable livelihoods, it empirically assesses the impact of Tea-GIAHS conservation on their sustainable livelihoods, while further examining the roles of agricultural scale and industrialization in this process. The research also investigates the heterogeneous effects of Tea-GIAHS conservation on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods across four dimensions: heritage sites, livelihood status, income levels, and livelihood types. The main findings are as follows. First, Tea-GIAHS conservation has a significant positive impact on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods and its constituent dimensions, including livelihood capitals, strategies, and outcomes. Second, mechanism analysis reveals that Tea-GIAHS conservation enhances farmers’ sustainable livelihoods by facilitating the scaling and industrialization of traditional agricultural operations. Third, heterogeneity analysis shows that the positive effects of Tea-GIAHS conservation are more pronounced among households with higher livelihood levels, higher incomes, and those engaged in agricultural-based livelihoods, reflecting a “Matthew effect” in its influence on farmers’ sustainable livelihoods.

Based on the above quantitative findings, the following targeted policy recommendations are proposed. Given the currently insufficient subsidies for traditional tea cultivation at the farmer level and inadequate financial support for industrialized operations within Tea-GIAHS sites, it is essential to enhance support for large-scale traditional tea planting and continuously improve and extend the related industrial and value chains. At the same time, both the short-term effectiveness and long-term sustainable impact of policies must be taken into consideration.

First, increase investment to facilitate the scaling of traditional tea operations. The mechanism test identified a significant positive mediating effect of agricultural scaling. To activate this pathway, policy emphasis should be placed on scaled cultivation subsidies, processing support, and marketing assistance. These measures will directly encourage farmers to expand tea garden areas, thereby leveraging the verified mechanism to enhance sustainable livelihoods. Furthermore, to ensure the long-term sustainability of scaled operations, it is necessary both to develop rural infrastructure (such as irrigation and roads) to support larger-scale production and operation, and to foster tea farmer cooperatives or associations to reduce costs and enhance bargaining power.

Second, promote value chain development to advance the industrialization of traditional tea operations. The analysis identified an even stronger mediating effect through industrialization. In the short term, efforts should focus on advancing local eco-friendly tea brands and GIs, launching tea culture tourism projects through partnerships with local tourism operators, and facilitating basic vertical integration, such as connecting tea farms with local processing facilities. In the long term, the focus should shift to fostering deep-processing enterprises for high-value products (e.g., tea extracts and functional foods) and promoting cross-sectoral convergence with the tourism, cultural, and health industries. These strategies are directly supported by the quantitative evidence showing that industrialization is a powerful channel for improving livelihood outcomes.

Third, implement differentiated conservation and management policies tailored to various farmer types. The heterogeneity analyses provide clear guidance for targeting. For farmers with different livelihood levels, the significant “Matthew effect” indicates that farmers with higher initial livelihood levels benefit more. Therefore, complementary capacity-building and resource-access programs are crucial for low-level households to ensure equitable benefits and prevent widening disparities. For agricultural and non-agricultural households, given the larger coefficient for agricultural households compared to non-agricultural ones, support for the former should focus on improving quality and efficiency within existing tea production, while the latter may benefit from support for diversified operations within the tea sector. To build systematic resilience and equity safeguards, it is essential to strengthen community governance and benefit-sharing mechanisms, thereby ensuring that the long-term benefits of AHS conservation are distributed equitably among all farmer groups.