No One-Size-Fits-All: A Systematic Review of LCA Software and a Selection Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

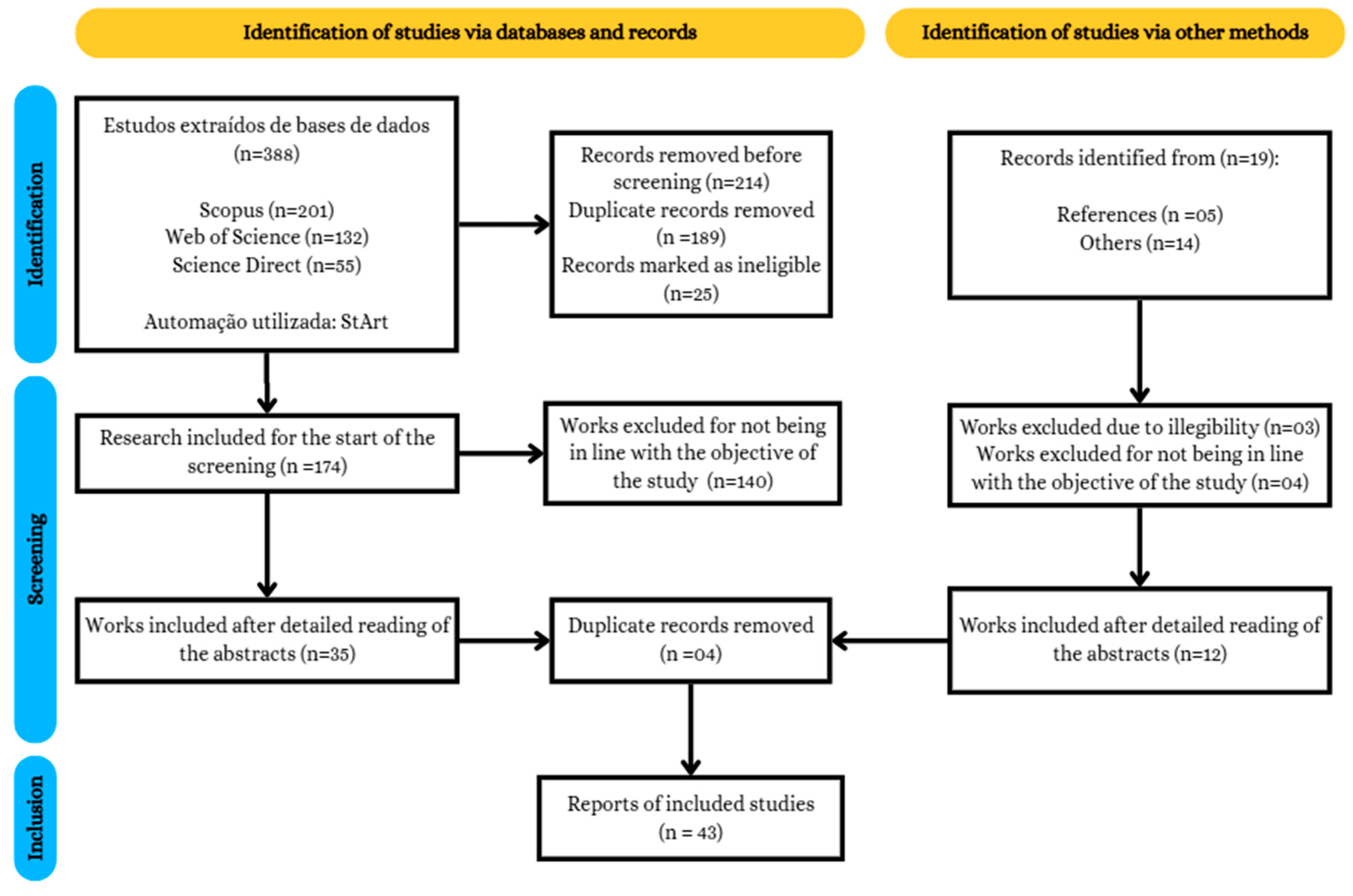

3. Materials and Methods

- (i)

- Use and presentation of only one LCA tool in the study (112 articles);

- (ii)

- Lack of explicit identification of the LCA tool used (10 articles);

- (iii)

- Development of an alternative tool rather than performing an LCA or analyzing LCA tools (2 articles);

- (iv)

- Conducting a comparative LCA but not comparing the results or usage of different LCA software tools (16 articles).

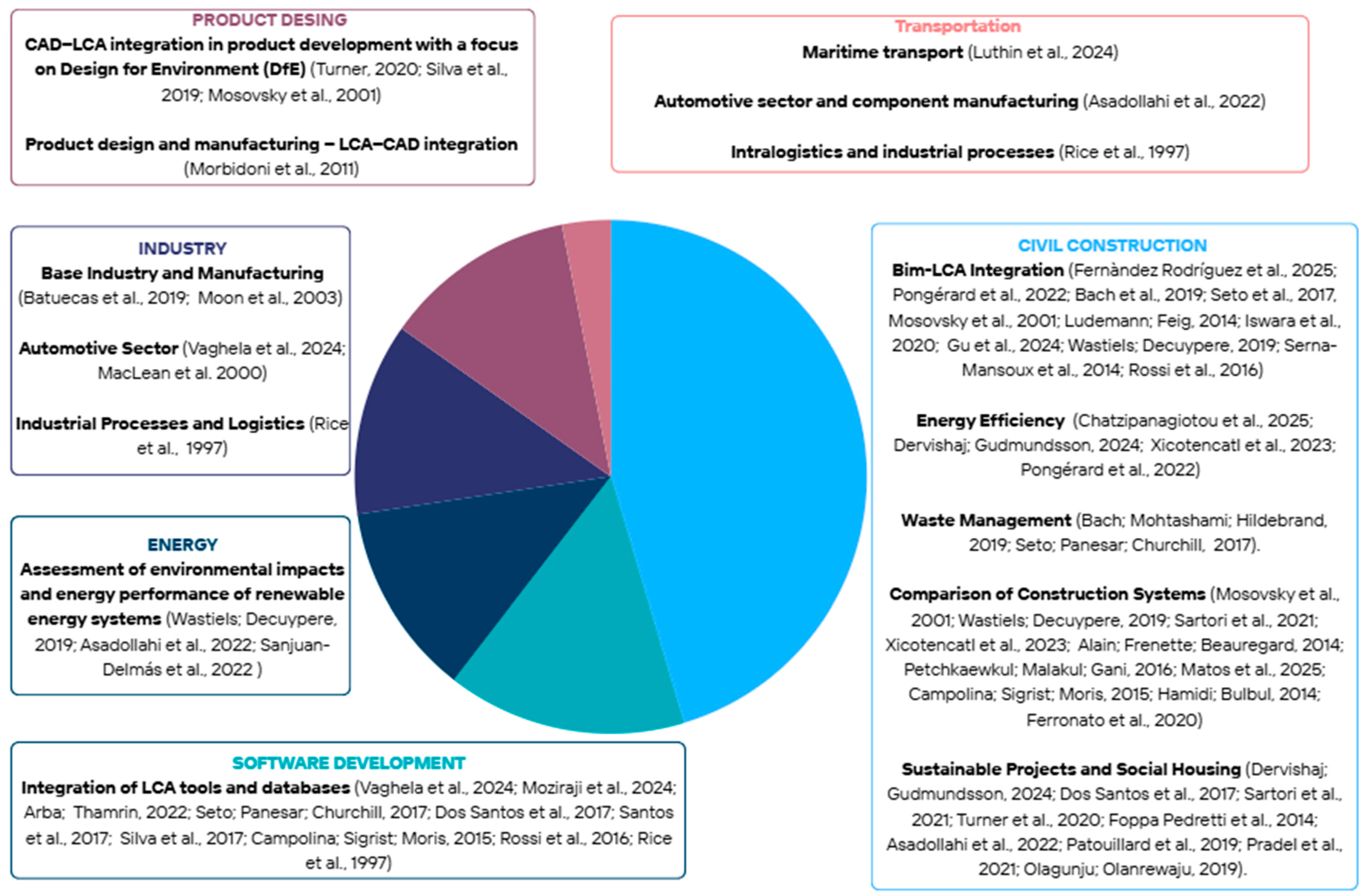

4. Results

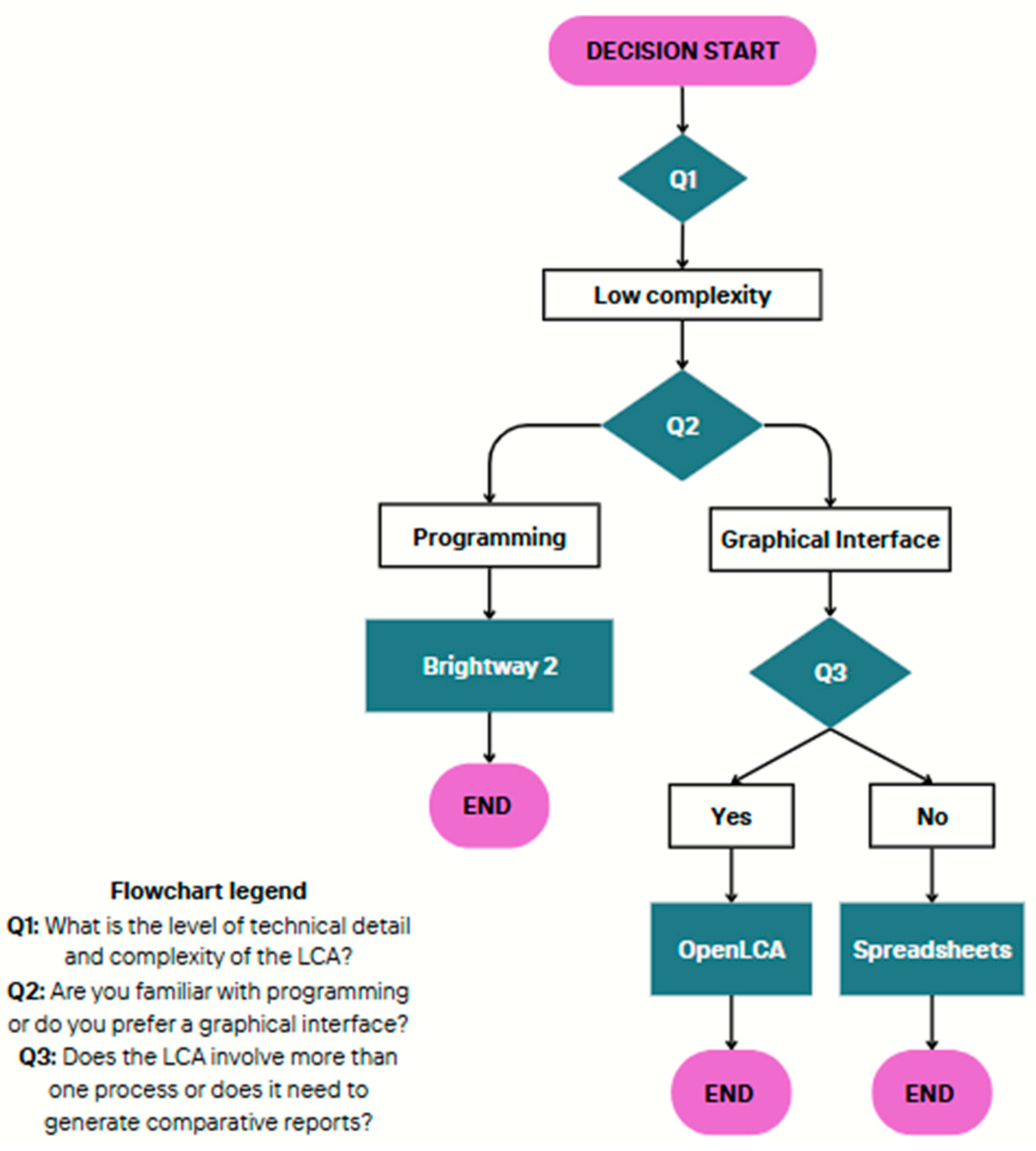

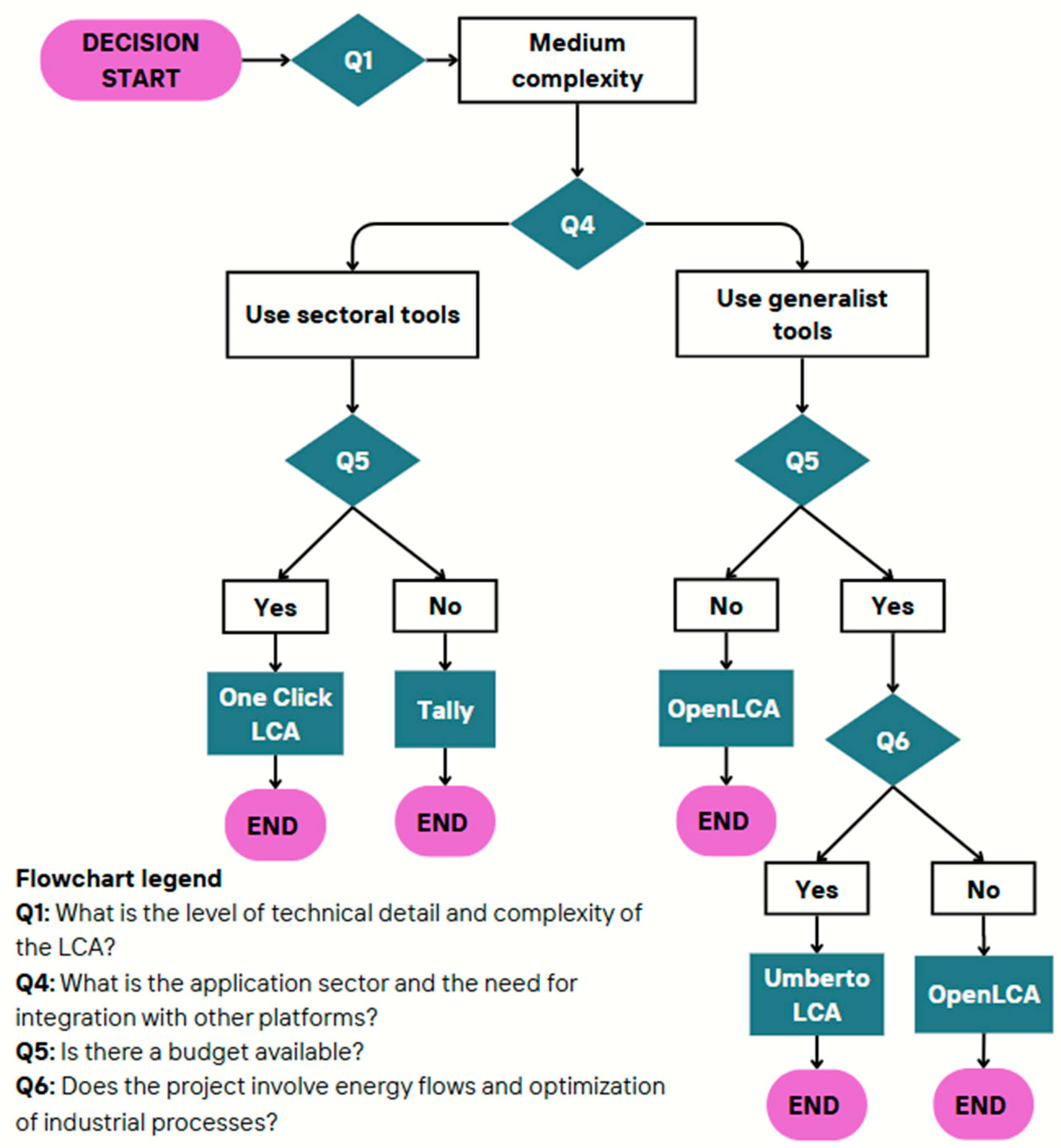

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| BIM | Building Information Modelling |

| CAD | Computer-Aided Design |

| EPA | Environmental Protection Agency |

| EPD | Environmental Product Declaration |

| ERP | Enterprise Resource Planning |

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| LCA | Life Cycle Assessment |

| LCI | Life Cycle Inventory |

| LCIA | Life Cycle Impact Assessment |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SLR | Systematic Literature Review |

| TOTEM | Tool to Optimize the Total Environmental Impact of Materials |

| DGNB | German Sustainable Building Council |

| BNB | Federal Assessment System for Sustainable Building |

| GREET | Greenhouse gases, Regulated Emissions, and Energy use in Technologies |

Appendix A

| Tool | Source | |

| Athena (Version 5.5 Build 0113) | Type of license: Free (non-commercial use) Developer: Athena Sustainable Materials Institute (Canada) Scope: Civil construction Standards compliance: ISO 1404 [21], Standart’s ISO 14044: 2006 of Environmental management of Life cycle assessment: Requirements and guidelines (2006) [21], aligned with Standard’s EN 15804: 2012 of Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products [92]. Link: https://www.athenasmi.org/our-software-data/overview (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [53,57,65,70,73,78,79,83] |

| BEES Online 2.1 | Type of license: Free Developer: National Institute of Standards and Technology (United States) Scope: Environmental and economic assessment of construction products Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21] and Standard Classification for Building Elements and Related Sitework—UNIFORMAT II [93] Link for download: https://www.nist.gov/services-resources/software/bees (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [21,54,59,81] |

| BioGrace Spreadsheet (Version 4d) | Type of license: Free (Excel-based) Developer: BioGrace Project (European Union) Scope: Calculation of greenhouse gas emissions for bioenergy Download link: https://biograce.net (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [57,71,83] |

| Brightway (Version 2.5 | Type of license: Free and open-source Developer: Chris Mutel/Paul Scherrer Institute (Switzerland) Scope: LCA with focus on research and advanced modelling Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21] Access link: https://brightway.dev/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [69,70,75] |

| CMLCA (Version 6.1) | Type of license: Free (academic software) Developer: University of Leiden (Netherlands) Scope: Life Cycle Assessment, input-output analysis, sustainability evaluation Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21] Download link: https://cmlca.software.informer.com/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [61,70] |

| Ecodesign studio * | Type of license: Commercial (with demo available upon request) Developer: Altermaker (France) Scope: Life Cycle Assessment and eco-design for industrial products Standards compliance: Aligned with ISO 14040 [21] Access link: https://altermaker.com/ecodesign-studio-2/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [53] |

| eLCA * | Type of license: Free (web-based tool for professional and academic use in Germany) Developer: Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung (BBSR), Germany Scope: LCAent in line with German certification systems (e.g., BNB) Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21] and aligned with EN 15804 [92]. Access link: https://www.bauteileditor.de (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [54] |

| Elodie * | Type of license: Commercial (license-based use) Developer: CSTB—Centre Scientifique et Technique du Bâtiment (France) Scope: Life Cycle Assessment of buildings; used for the environmental evaluation of construction projects based on French and European regulations Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21] and aligned with EN 15804 [92]. Access link: https://info.cype.com/fr/software/elodie-by-cype/ (accessed on 12 August 2025) | [62,66] |

| GaBi LCA * | Type of license: Commercial (paid license with free trial) Developer: Sphera (Germany) Scope: Industrial and corporate environmental assessment across various sectors (automotive, electronics, chemical, etc.) Standards compliance: ISO 14040 [21] and aligned with EN 15804 [92]. https://sphera.com/product-stewardship/life-cycle-assessment-software-and-data (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [20,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,63,69,77,78,79,81,83,85,86,87,88,89,90] |

| GREET (Version 45VH2-GREET) | Type of license: Free (publicly available for research and policy use) Developer: Argonne National Laboratory (United States Department of Energy) Scope: Life cycle modelling of energy systems and transportation fuels; evaluates greenhouse gas emissions, energy use, and air pollutants for a wide range of fuel pathways and vehicle technologies Standards compliance: Aligned with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] principles and widely used for policy analysis, including in LCAs for regulatory and academic purposes Access link: https://www.energy.gov/eere/greet (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [81,83] |

| IDEMAT (Version Idemat 2025RevA8) | Type of license: Free (for educational and non-commercial use) Developer: Delft University of Technology (Netherlands) Scope: Material selection based on environmental indicators; provides LCI data and eco-costs values to support sustainable design Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] Access link: https://idematapp.com (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [81] |

| Legep * | Type of license: Free (for non-commercial and educational use) Developer: Research Group for Environmental Controlling—Germany Scope: LCA of buildings, focusing on ecological optimization in early design phases Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] and aligned with DGNB and BNB Download link: https://legep.de/?lang=en (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [54] |

| One ClickLCA (Version 4.0.9) | Type of license: Commercial (with free trial version) Developer: Bionova Ltd. (Finland) Scope: Civil construction and manufacturing; generation of Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) Standards compliance: ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21], EN 15804 [92], LEED and BREEAM Access link: https://oneclicklca.com (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [62,66,67] |

| OpenLCA (Version 2.5.0) | Type of license: Free and open-source Developer: GreenDelta GmbH (Germany) Scope: Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), Carbon Footprint, Water Footprint, Social LCA, Sustainability Assessment Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21], ILCD, PEF, SLCA Download link: https://www.openlca.org/download/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [20,53,54,55,58,60,63,64,69,75,76,77,78,80,88] |

| PaLATE Spreadsheet (Version 2.0) | Type of license: Free (Excel-based) Developer: University of California, Berkeley (USA) Scope: Environmental and economic assessment of pavements and roads Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] Download link: https://rmrc.wisc.edu/palate/ (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [20,57,63,83] |

| Quantis Suite (Version 2.0) | Type of license: Commercial (with free tools available) Developer: Quantis (Switzerland) Scope: Corporate environmental assessment (Carbon Footprint and Water Footprint) Standards compliance: ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] Access link: https://quantis.com (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [59] |

| SimaPro (Version Craft 10.2) | Type of license: Commercial Developer: PRé Sustainability (Netherlands) Scope: Environmental assessment of products, processes, and services Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21]; supports ILCD and PEF. Link: https://simapro.com/plans (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [20,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,63,64,65,68,69,74,75,76,77,80,81,82,84,85,86,87,88] |

| Solid Works Sustainability * | Type of license: Commercial (Professional and Premium—SolidWorks) Developer: Dassault Systèmes (France) Scope: Environmental assessment integrated into mechanical product design Standards compliance: Compliant with ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21]. Access link: https://www.solidworks.com/product/solidworks-3d-cad (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [89] |

| Tally LCA (Version 1.0) | Type of license: Commercial (paid license with 10-day trial) Developer: KieranTimberlake, Partnership between Autodesk and Sphera Scope: Civil construction, integration with Autodesk Revit for building analysis Standards compliance:ISO 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21], Standart’s of Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works – Core Rules for Environmental Product Declarations of Construction Products and Services (ISO 21930:2017) [94], EN 15804 [92] Link: https://apps.autodesk.com/RVT/en/Detail/Index?id=3841858388457011756 (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [54,62,66,79] |

| TEAM (Version 4.0) | Type of license: Commercial (paid license) Developer: PRé Sustainability Scope: Detailed environmental assessment of products and processes Standards compliance: 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] Link: https://pre-sustainability.com (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [85] |

| TOTEM * | Type of license: Free Developer: Consortium led by VITO/EnergyVille, KU Leuven, BBRI, UC Louvain and ICEDD (Belgium) Scope: Assessment of the environmental impact of buildings over their entire life cycle. Standards compliance: Aligned with European LCA methodology best practices Access link: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/toolkits-guidelines/totem-online-tool-architects-calculates-environmental-footprint-buildings (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [62,66] |

| Umberto (Version 5.5.4) | Type of license: Commercial (paid license with evaluation version) Developer: ifu Hamburg/iPoint-systems (Germany) Scope: Process modelling, carbon footprint, energy and material flow diagrams. Standards compliance: 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21], Standart’s of Environmental Management—Material Flow Cost Accounting—General Framework (ISO 14051:2011) [95], Standart’s of Greenhouse Gases—Part 1: Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals (ISO 14064-1:2018) [93] and PEF Link: https://www.ipoint-systems.com/software/umberto (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [53,54,55,58,60,78,81] |

| VTTI/UC Asphalt Pavement LCA Model * | Type of license: Academic (for research use) Developer: Virginia Tech Transportation Institute (VTTI) and University of California Scope: Life Cycle Assessment of asphalt pavements Standards compliance: Compliant with 14040 [21], ISO 14044 [21] Access link: Not publicly available; restricted to the University of Coimbra–Virginia Tech partnership. | [20,63] |

| Warm * | Type of license: Free Developer: United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) Scope: Estimation of greenhouse gas emissions reductions from waste management strategies, including source reduction, recycling, composting, incineration, and landfilling Standards compliance: Greenhouse gas inventory methodologies Access link: https://www.epa.gov/warm (accessed on 10 August 2025) | [73] |

- * Several LCA tools used in this study (GaBi, Ecodesign Studio, eLCA, ELODIE, Legep, SolidWorks Sustainability, TOTEM, VTTI/UC Asphalt LCA Model and the US EPA WARM tool) operate without explicit software version numbering. These platforms follow a continuous-update model, where improvements and dataset revisions are incorporated directly into the online or integrated environment. In such cases, the access date is reported as the reference for the consulted release.

Appendix B

References

- Rodrigues, M. The circular economy as a pathway to a sustainable future. Trends Hub 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 59000:2024; Circular Economy—Fundamentals and Principles. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- ISO 59010; Circular Economy—Framework and Principles for Implementation. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024.

- Isérnia, R.; Passaro, R.; Quinto, I.; Thomas, A. The reverse supply chain of electronic waste management processes in a circular economy framework: Evidence from Italy. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Jha, P.C.; Garg, K. Product recovery optimization in closed-loop supply chain to improve sustainability in manufacturing. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 54, 1463–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Lu, B.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhai, G.; Zhou, G.; Jiang, B.; Schnoor, J.L. Extended producer responsibility system in China improves e-waste recycling: Government policies, enterprise, and public awareness. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 62, 882–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Ryu, K.; Jung, M. Reinforcement learning approach for goal regulation in a self-evolutionary manufacturing system. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 8736–8743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mälkki, H.; Alanne, K. An overview of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and research-based teaching in renewable and sustainable energy education. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 68, 218–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, R.; Fantke, P.; Bjørn, A.; Owsianiak, M.; Molin, C.; Hauschild, M.Z.; Laurent, A. Life cycle assessment in corporate sustainability reporting: Global, regional, sectoral and company-level trends. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2018, 27, 1602–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Tessitore, S.; Buttol, P.; Iraldo, F.; Cortesi, S. How to overcome barriers limiting the adoption of LCA? The role of a collaborative and multisectoral approach. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 944–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaniotto, R.A. The Integration of the Circular Economy into the Concept of Sustainable Development: The Role of the State and Industry in Promoting Circularity. Master’s Thesis, University of Caxias do Sul, Caxias do Sul, Brazil, 2020. Available online: https://repositorio.ucs.br/xmlui/handle/11338/6719 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Solid Waste Panorama in Brazil. Available online: https://cempre.org.br (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Barreto, A.A.; Santos, T.T.S. Ecodesign and Innovation in Cosmetic Product Packaging. Undergraduate Final Paper, Centro Paula Souza, São Paulo, Brazil, 2022. Available online: https://ric.cps.sp.gov.br/handle/123456789/19061 (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Ebrahimi, S.M.; Koh, L. Sustainability in manufacturing: Institutional theory and life cycle thinking. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellani, V.; Sanyé-Mengual, E.; Sala, S. Environmental impacts of consumer goods in Europe: A process-based life cycle assessment model to evaluate the consumption footprint. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26, 2040–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, T.E.H. Sustainable competitive advantage: A leap forward in sustainable strategy with blockchain-enabled LCA. In Life Cycle Assessment: New Developments and Multi-Disciplinary Applications; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 2022; p. 177. [Google Scholar]

- Pryshlakivsky, J.; Searcy, C. Life Cycle Assessment as a decision-making tool: Practitioner and managerial considerations. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 309, 127344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bläse, R.; Filser, M.; Weise, J.; Björck, A.; Puumalainen, K. Identifying institutional gaps: Implications for an early-stage support framework for impact entrepreneurs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 679–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimin, H.H.; Hishamuddin, H.; Maelah, R.; Abdul Hameed, M.A.S.A.K.; Ab Rahman, M.N.; Amir, A.M. Cleaner power generation: An in-depth review of life cycle assessment for solid oxide fuel cells. Jurnal Kejuruteraan 2023, si6, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, J.M.O.; Thyagarajan, S.; Keijzer, E.; Flores, R.F.; Flintsch, G. Comparison of life-cycle assessment tools for road pavement infrastructure. Transp. Res. Rec. 2017, 2646, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040:2006; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Di Vaio, A.; Varriale, L.; Di Gregorio, A.; Adomako, S. Corporate social performance and non-financial reporting in the cruise industry: Paving the way towards UN Agenda 2030. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2022, 29, 1545–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerchione, R.; Morelli, M.; Passaro, R.; Quinto, I. A critical analysis of the integration of life cycle methods and sustainability in business practice: Evidences from a systematic literature review. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 31, 1047–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, M.; Vinci, G.; Ruggieri, R.; Savastano, M. Facing the risk of greenwashing in the ESG report of global companies: The importance of life cycle thinking. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2025, 32, 4216–4234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinée, J.B.; Heijungs, R.; Huppes, G.; Zamagni, A.; Masoni, P.; Buonamici, R.; Ekvall, T.; Rydberg, T. Avaliação do Ciclo de Vida: Passado, Presente e Futuro. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 45, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabo, A.-A.A.; Hosseinian-Far, A. Uma Metodologia Integrada para Aprimorar Fluxos e Redes de Logística Reversa na Indústria 5.0. Logistics 2023, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, L.J.R. Reverse logistics as a catalyst for decarbonizing supply chains of forest products. Logistics 2025, 9, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbinati, A.; Shams Esfandabadi, Z.; Messeni Petruzzelli, A. Assessing the interplay between Open Innovation and Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A systematic literature review and a research agenda. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2023, 32, 610–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellweg, S.; Benetto, E.; Huijbregts, M.A.J.; Verones, F.; Wood, R. Life-cycle assessment to guide solutions for the triple planetary crisis. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2023, 4, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, M.A. A circular economy for consumer electronics. In Environmental Science and Technology Issues; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, UK, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 66–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaustad, G.; Krystofik, M.; Bustamante, M.; Badami, K. Circular economy strategies to mitigate critical material supply issues. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 135, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumée, L.F. Circular materials and circular design—A review of challenges for sustainable manufacturing and recycling. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2022, 2, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daub, C.-H. Assessing the quality of sustainability reporting: An alternative methodological approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2007, 15, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.; Andrews, D.; Ralph, B.; France, C. Applying organizational environmental tools and techniques. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2002, 9, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramteke, S.V.; Varadwaj, P.K.; Tiwari, V. Optimizing UAV spraying for sustainable agriculture: A life cycle and efficiency analysis in India. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.J.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y. A sustainability-oriented framework for environmental cost accounting and carbon financial optimization in prefabricated steel structures. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, B.; Silva, T.R.; Soares, N.; Monteiro, H. Eco-efficiency of concrete sandwich panels with different insulating core materials. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wastiels, L.; Decuypere, R. Identification and comparison of LCA-BIM integration strategies. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 323, 012101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, D.; Pacana, A. Sustainable prototyping: Linking quality and environmental impact via QFD and LCA. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stramarkou, M.; Boukouvalas, C.; Fragkouli, D.N.; Tsamis, C.; Krokida, M. Sustainability assessment of Tetra Pak smart packaging through economic and life cycle analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14001:2015; Environmental management systems—Requirements with guidance for use. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- Köck, B.; Friedl, A.; Serna Loaiza, S.; Wukovits, W.; Mihalyi-Schneider, B. Automation of Life Cycle Assessment: A critical review of developments in Life Cycle Inventory analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 5531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, J.; Gallagher, S. Challenges of open innovation: The paradox of corporate investment in open-source software. RD Manag. 2006, 36, 319–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretthauer, D. Open Source Software: A History; University of Connecticut: Storrs, CT, USA, 2001. Available online: https://digitalcommons.lib.uconn.edu/libr_pubs/7/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Soust-Verdaguer, B.; Llatas, C.; García-Martínez, A. Critical review of BIM-based LCA method to buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 136, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutel, C. Brightway: An open source framework for Life Cycle Assessment. J. Open Source Softw. 2017, 2, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Charters, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering; Technical Report EBSE 2007-001; Keele University: Newcastle, UK; Durham University: Durham, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Li, C. Circular economy practices in the waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) industry: A systematic review and future research agendas. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 365, 132671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, S.; Oza, P.; Kakkar, R.; Tanwar, S.; Jetani, V.; Undhdad, J.; Singh, A. PRISMA checklist-based analysis and recommendation system for writing a systematic review. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 150, 100866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, C. Sampling knowledge: The hermeneutics of snowball sampling in qualitative research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2008, 11, 327–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewes, J.O. Snowball Sampling and Respondent-Driven Sampling: A Description of the Methods. Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS): Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 2013; un published manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Vaghela, J.R.; Patel, H.; Panchal, H.; Parmar, M. Comparative Analysis on Sustainability Parameters of Traditional Tool Manufacturing Processes Using Life Cycle Analysis Tools. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2024, 17, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bach, R.; Mohtashami, N.; Hildebrand, L. Comparative overview of LCA software programs for application in the facade design process. J. Facade Des. Eng. 2019, 1, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, D.; Nunes, A.; Moris, V.; Piekarski, C.; Rodrigues, T. How important is the LCA software tool you choose? Comparative results from GaBi, openLCA, SimaPro and Umberto. In Proceedings of the VII International Conference on Life Cycle Assessment in Latin America (CILCA), Medellín, Colombia, 12–15 June 2017; pp. 10–15. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, G.; Clift, R.; Burns, R. Comparison of currently available European LCA software. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 1997, 2, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüdemann, L.; Feig, K. Comparison of software solutions for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—A software ergonomic analysis. Logist. J. Editor.-Rev. 2014. Available online: https://doi.org/10.2195/lj_NotRev_luedemann_de_201409_01 (accessed on 4 September 2025).

- Seto, K.E.; Panesar, D.K.; Churchill, C.J. Criteria for the evaluation of life cycle assessment software packages and life cycle inventory data with application to concrete. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2017, 22, 694–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosovsky, J.A.; Maxwell, D.; Hassan, M.M.; Smith, D.R. Assessing product design alternatives with respect to environmental performance and sustainability: A case study for circuit pack faceplates. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment (ISEE), Denver, CO, USA, 9 May 2001; pp. 252–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petchkaewkul, K.; Malakul, P.; Gani, R. Systematic, efficient and consistent LCA calculations for chemical and biochemical processes. In Proceedings of the 26th European Symposium on Computer Aided Process Engineering—ESCAPE 26; Kravanja, Z., Bogataj, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.A.L.; Nunes, A.; Piekarski, C.M.; Moris, V.A.S.; Souza, L.G.M.; Rodrigues, T.L. Why using different Life Cycle Assessment software tools can generate different results for the same product system? A cause–effect analysis of the problem. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2019, 20, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morbidoni, A.; Favi, C.; Germani, M. CAD-Integrated LCA Tool: Comparison with dedicated LCA Software and Guidelines for the improvement. In Glocalized Solutions for Sustainability in Manufacturing: Proceedings of the 18th CIRP International Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Technische Universität Braunschweig, Braunschweig, Germany, 2–4 May 2011; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 569–574. [Google Scholar]

- Batuecas, E.; Tommasi, T.; Battista, F.; Negro, V.; Sonetti, G.; Viotti, P.; Fino, D.; Mancini, G. Life Cycle Assessment of waste disposal from olive oil production: Anaerobic digestion and conventional disposal on soil. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 237, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Chung, K.; Eun, J.; Chung, J. Life cycle assessment through on-line database linked with various enterprise database systems. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2003, 8, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadollahi, A.; Tohidi, H.; Shoja, A. Sustainable waste management scenarios for food packaging materials using SimaPro and WARM. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 9479–9494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Thyagarajan, S.; Keijzer, E.; Flores, R.; Flintsch, G. Pavement life cycle assessment: A comparison of American and European tools. In Pavement Life-Cycle Assessment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moziraji, M.R.; Tehrani, A.A.; Reshadi, M.A.M.; Bazargan, A. Natural gas as a relatively clean substitute for coal in the MIDREX process for producing direct reduced iron. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2024, 78, 101356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campolina, J.M.; Sigrist, C.S.L.; Moris, V.A. A literature review on software used in Life Cycle Assessment studies. Rev. Electron. Manag. Educ. Environ. Technol. 2015, 19, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Germani, M.; Zamagni, A. Review of ecodesign methods and tools. Barriers and strategies for an effective implementation in industrial companies. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 129, 361–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthin, A.; Crawford, R.H.; Traverso, M. Assessing the circularity and sustainability of circular carpets—A demonstration of circular life cycle sustainability assessment. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2024, 29, 1945–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, B.; Bulbul, T. An Evaluation of Life Cycle Analysis (LCA) Tools for Environmental Impact Analysis of Building End-of-Life Cycle Operations. In Proceedings of the Computing in Civil and Building Engineering (2014), Orlando, FL, USA, 23–25 June 2014; pp. 1943–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongérard, M.; San Augustin, F.; Paredes, M. Comparison of tools for simplified life cycle assessment in mechanical engineering. In Advances in Design Engineering II: Proceedings of the XXX International Congress INGEGRAF, 24–25 June 2021, Valencia, Spain; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iswara, A.P.; Farahdiba, A.U.; Nadhifatin, E.; Pirade, F.; Andhikaputra, G.; Muflihah, I.; Boedisantoso, R. A Comparative Study of Life Cycle Impact Assessment using Different Software Programs. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 506, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, C.; Gu, H.; Gong, M.; Blackadar, J.; Zahabi, N. Comparison of using two LCA software programs to assess the environmental impacts of two institutional buildings. Sustain. Struct. 2024, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serna-Mansoux, L.; Domingo, L.; Millet, D.; Brissaud, D. A Tool for Detailed Analysis and Ecological Assessment of the Use Phase. Procedia CIRP 2014, 15, 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, R.; Rodrigues, H.; Costa, A.; Rodrigues, M.F.; Lavy, S.; Dixit, M. Life cycle assessment applied to facility management of exposed steel frames—Case study. Facilities 2025, 43, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dervishaj, A.; Gudmundsson, K. From LCA to circular design: A comparative study of digital tools for the built environment. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2024, 200, 107291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xicotencatl, B.; Kleijn, R.; van Nielen, S.; Donati, F.; Sprecher, B.; Tukker, A. Data implementation matters: Effect of software choice and LCI database evolution on a comparative LCA study of permanent magnets. J. Ind. Ecol. 2023, 27, 1252–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, T.; Drogemuller, R.; Omrani, S.; Lamari, F. A schematic framework for Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Green Building Rating System (GBRS). J. Build. Eng. 2021, 38, 102180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alain, S.; Frenette, C.; Beauregard, R. Environmental performance of innovative wood building systems using life-cycle assessment. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Timber Engineering (WCTE 2014), Quebec City, QC, Canada, 10–14 August 2014; pp. 3159–3168. [Google Scholar]

- Ferronato, N.; Gorritty, M.; Guisbert Lizarazu, E.; Torretta, V. Application of a life cycle assessment for assessing municipal solid waste management systems in Bolivia in an international cooperative framework. Waste Manag. Res. 2020, 38, 98–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, I.; Smart, A.; Adams, E.; Pelletier, N. Building an ILCD/EcoSPOLD2–compliant data-reporting template with application to Canadian agri-food LCI data. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 1402–1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, E.F.; Duca, D.; Toscano, G.; Riva, G.; Pizzi, A.; Rossini, G.; Saltari, M.; Mengarelli, C.; Gardiman, M.; Flamini, R. Sustainability of grape-ethanol energy chain. J. Agric. Eng. 2014, 45, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patouillard, L.; Collet, P.; Lesage, P.; Tirado Seco, P.; Bulle, C.; Margni, M. Prioritizing regionalization efforts in life cycle assessment through global sensitivity analysis: A sector meta-analysis based on ecoinvent v3. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2019, 24, 2238–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olagunju, B.D.; Olanrewaju, O.A. Comparison of life cycle assessment tools in cement production. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2020, 31, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradel, M.; Garcia, J.; Vaija, M.S. A framework for good practices to assess abiotic mineral resource depletion in Life Cycle Assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arba, Y.; Thamrin, S. Perbandingan Pemodelan Perangkat Lunak Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) untuk Teknologi Energi. Jurnal Energi Baru & Terbarukan 2022, 3(2), 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatzipanagiotou, K.-R.; Petrakli, F.; Steck, J.; Philippot, C.; Artous, S.; Koumoulos, E.P. Towards safe and sustainable by design nanomaterials: Risk and sustainability assessment on two nanomaterial case studies at early stages of development. Sustainable Futures. 2025, 9, 100511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjuan-Delmás, D.; Alvarenga, R.A.F.; Lindblom, M.; Kampmann, T.; Oers, L.; Guinée, J.; Dewulf, J. Environmental assessment of copper production in Europe: An LCA case study from Sweden conducted using two conventional software-database setups. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2022, 27, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Rodríguez, J.F.; Picardo, A.; Aguilar-Planet, T.; Martín-Mariscal, A.; Peralta, E. Data Transfer Reliability from Building Information Modeling (BIM) to Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)—A Comparative Case Study of an Industrial Warehouse. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclean, H.L.; Lave, L.B.; Lankey, R.; Joshi, S. A Life-Cycle Comparison of Alternative Automobile Fuels. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2000, 50, 1769–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 15804:2012; Sustainability of Construction Works—Environmental Product Declarations—Core Rules for the Product Category of Construction Products. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2012.

- ISO 14064-1:2018; Greenhouse Gases—Part 1: Specification with Guidance at the Organization Level for Quantification and Reporting of Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 21930:2017; Sustainability in Buildings and Civil Engineering Works—Core Rules for Environmental Product Declarations of Construction Products and Services. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 14051:2011; Environmental Management—Material Flow Cost Accounting—General Framework. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

| String | Scopus * | Web of Science * | Science Direct * |

|---|---|---|---|

| (“Life Cycle Assessment” OR “LCA”) AND comparison AND “LCA software” | 101 | 67 | 24 |

| (“LCA tools” OR “LCA software”) AND (“case study” OR application) AND (SimaPro OR OpenLCA OR GaBi OR Umberto) | 100 | 65 | 31 |

| Number of papers | 388 | ||

| Factors | Justification |

|---|---|

| Origin | The developer can be either a company or a research institution, which influences both the accessibility and the scope of the tool [52,53,54]. |

| Suitability for application (sector and specific objective) | The choice of tool depends on the intended application. Software originally developed for specific sectors (such as packaging) has often been adapted for broader uses. Selecting the appropriate tool requires aligning the software’s functionalities with the type of study (industrial, academic, environmental, etc.), the required level of detail, and the quality of available data [55]. |

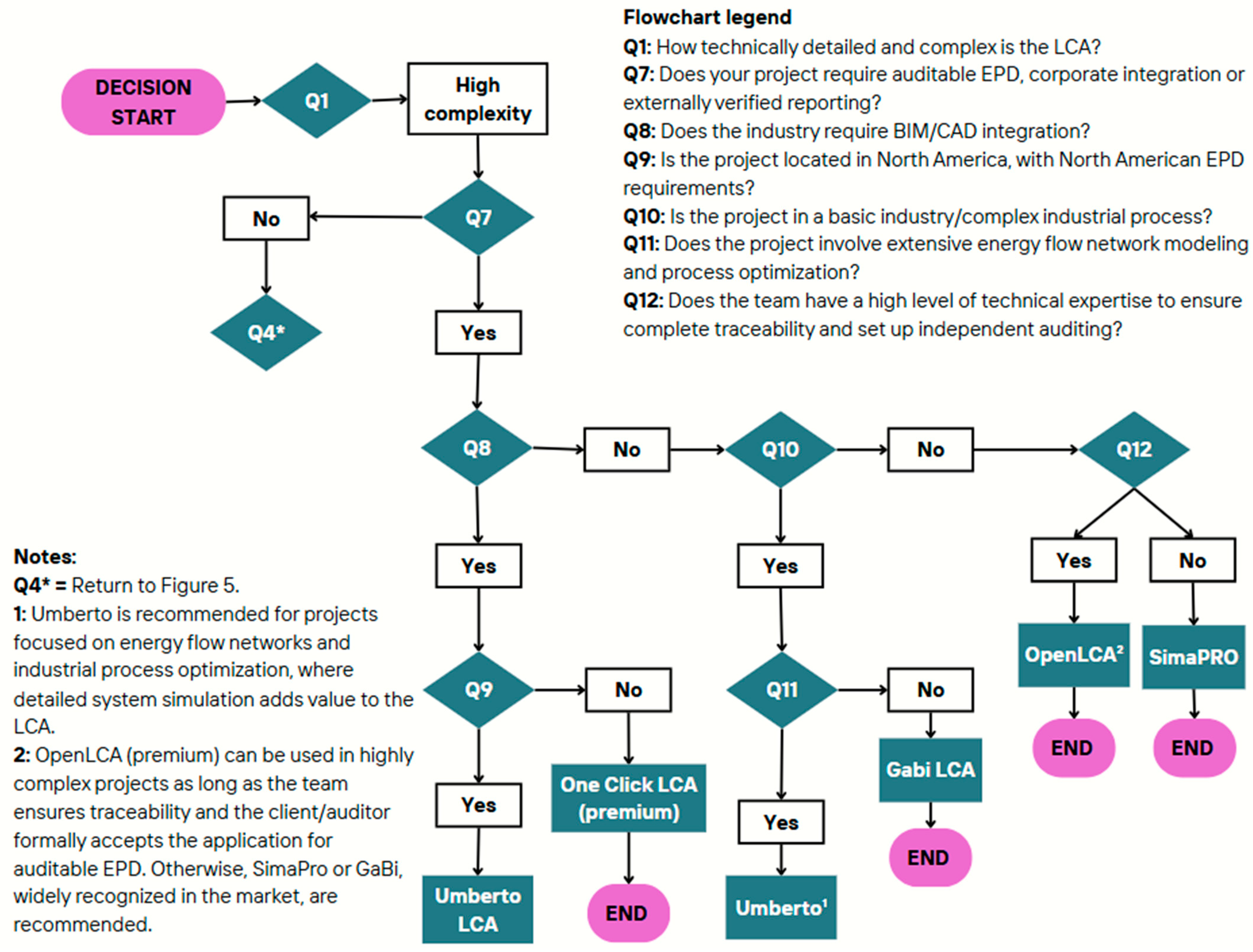

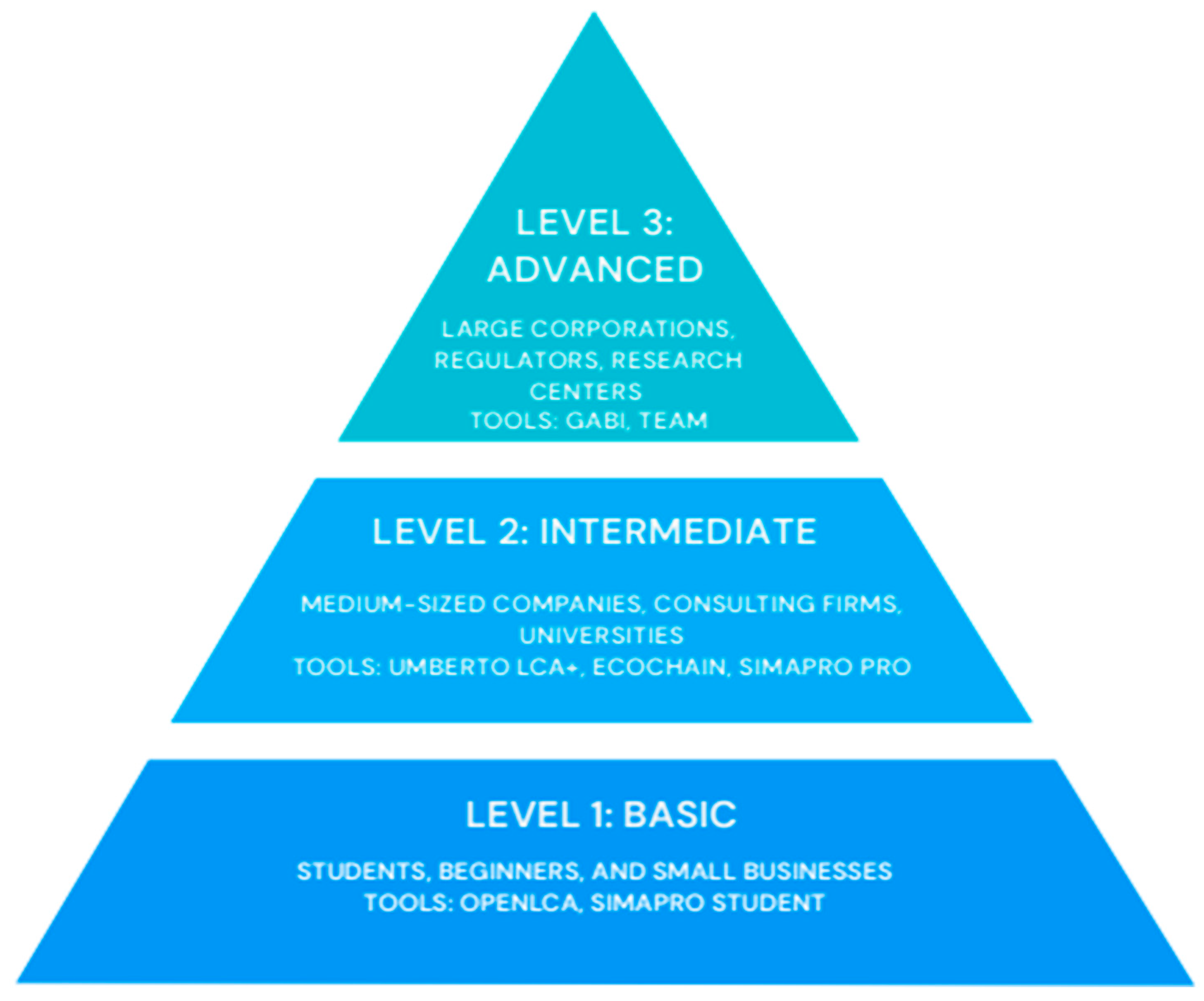

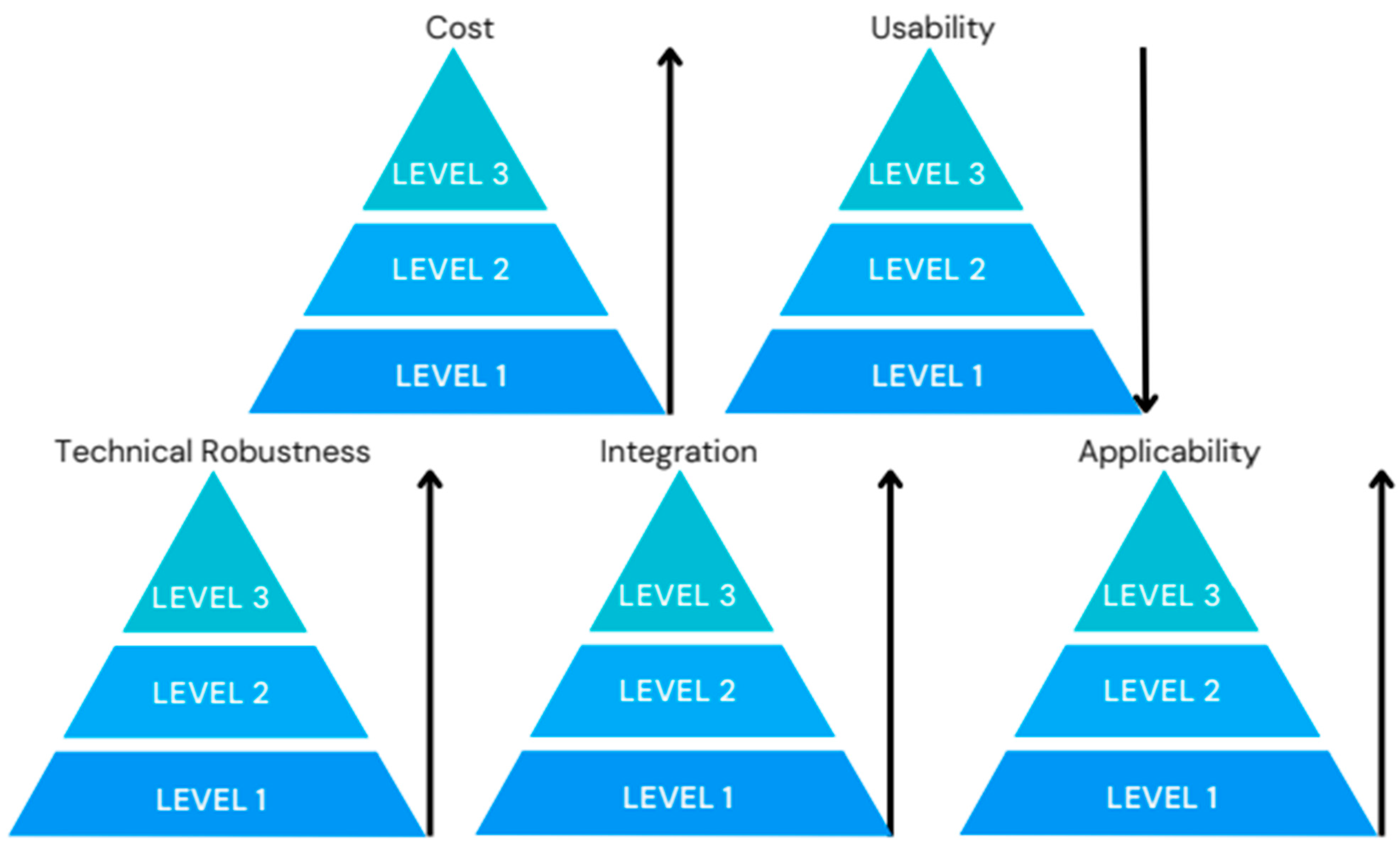

| Required user knowledge level | LCA tools cater to a range of users, from laypersons and beginners to specialists. Tools designed for experts offer advanced customization options and are commonly used in research and consultancy contexts, whereas more basic tools provide limited access to configurations [53,54]. |

| Integrated or compatible data sources | The software may include fixed databases or allow the integration of various data sources. Many databases are country-specific, which can influence results, for example, due to differences in renewable energy mixes across countries [54]. Additionally, the capability to import external databases is an important feature for enhancing flexibility and accuracy in assessments [56]. |

| Accepted data input formats | LCA calculations use mass or volume data as inputs, which can be entered manually via spreadsheets or derived from 3D geometric models. The use of spreadsheets typically requires prior calculations and data preparation [53,54]. |

| Optimization resources | An ideal LCA includes optimization, which can be performed manually through repeated analyses or computationally. While spreadsheets require manual adjustments, 3D software programs facilitate automatic optimization [53,54]. |

| General settings and customization options | Default settings facilitate the initial execution of LCA studies. The greater the number of predefined configurations, the easier it is to get started. For enhanced accuracy, specific adjustments can be made, such as modifications to the database, life cycle stages, and product lifespan [53]. |

| Life cycle stages covered | LCA typically encompasses production, use, and end-of-life phases; however, different standards are considered depending on the software tool employed [53]. |

| Result presentation formats | The results can be presented as graphs, tables, or automated reports, facilitating the analysis and communication of LCA data [54]. |

| User support | Some tools provide tutorials, user forums, or technical support, which facilitate learning and problem-solving [54,56]. |

| Additional functionalities | Differences in the ability to accurately model functional units and define system boundaries contribute significantly to the reliability of results [54,56]. |

| Compliance with recognized impact assessment methods | Support and the proper application of environmental impact assessment methods need to be consistently updated and reliable [57]. |

| Modelling capabilities | More advanced tools enable the evaluation of uncertainties and the sensitivity analysis of results in response to changes in data or model parameters [54]. |

| Tools | Total Articles per Tool |

|---|---|

| SimaPro | 24 |

| GaBi LCA | 21 |

| OpenLCA | 17 |

| Athena | 8 |

| Umberto | 7 |

| Tally | 4 |

| BEES | 3 |

| Brightway, CMLCA, Elodie, Greet, One Click LCA, PaLATE Spreadsheet, TEAM, Totem, VTTI/UC Asphalt Pavement LCA Model | 2 |

| BioGrace Spreadsheet, Ecodesign Studio, eLCA, IDEMAT, Legep, Quantis Suite, Solid Works Sustainability, Warm | 1 |

| Category | SimaPro | GaBi | OpenLCA | Athena | Umberto |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life Cycle Assessment Methodology | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI, Impact 2002+, etc. | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI, ILCD | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI, ILCD, EF | Customized—focused on construction | ReCiPe, CML, TRACI |

| Integrated Database | Ecoinvent, Agri-footprint, etc. | GaBi DB, Ecoinvent, US LCI | Ecoinvent, Agribalyse, ELCD | Own Athena database | Ecoinvent, GaBi DB, others |

| Modelling Capacity | High—advanced simulations and process networks | High—technical detail and customization | High—modular and transparent modelling | Low—limited to building structures | Medium—suitable for industrial flows |

| Sectors Served | Industry, research, consultancies | Industry, sustainability, energy | Academia, NGOs, light industry | Construction sector | Industry, manufacturing processes |

| Ease of Use | Requires technical knowledge | Moderate—requires training | High—intuitive interface | High—easy to operate | Moderate—learning curve |

| Interface Type | Graphical and flowchart-based | Graphical with interactive dashboards | Flowcharts and tables | Simplified interface by materials and assemblies | Flow- and diagram-based |

| Integration Capability | Excel, ERP, APIs | SAP, Excel | Excel, SQL databases, plug-ins | Limited external integration | ERP, Excel, specific interfaces |

| Licensing | Paid | Paid | Free (open-source) | Free with restrictions | Paid |

| Access Model | Local installation | Local installation and web | Local installation | Local installation | Local installation |

| License Cost type | Annual/lifetime plan | Annual plan | Open access | Open access | Annual plan |

| Update Frequency | Frequent updates | Regular updates | Constantly updated by the community | Sporadic updates | Scheduled updates |

| Technical Support | Yes | Yes (corporate support) | Limited to forums | Limited | Yes |

| Training Availability | Courses, tutorials, and manuals | Course and webinars | Guides, tutorials, and forums | Documentation on the website | Paid |

| Criterion | SimaPro | OpenLCA | GaBi LCA | Umberto | Athena |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interface and usability | Robust, good impact visualization [55,72] | Intuitive interface and table-based modelling [56]. | Beginner-friendly, modern interface [52]. | Graphical interface with Petri nets, less user-friendly [56,84]. | User-friendly interface and BIM integration [53,87]. |

| Modelling Flexibility | High flexibility and customization [82,84]. | High flexibility with customized models [52]. | Robust and flexible modelling [57,75]. | Highly flexible and detailed [71,84]. | Good for quick and simplified modelling [79]. |

| Compatibility with Databases | Broad compatibility [72]. | Compatible with multiple databases [66]. | Extensive data coverage—Ecoinvent, ELCD, US LCI [67]. | Ecoinvent versions 2 and 3 [71]. | Database specific to the construction sector [73]. |

| Impact Methods | Wide variety of methods—ReCiPe, CML, etc. [52]. | Good adaptation to multiple methods [85]. | Flows of ‘elements’ and ‘resources’ with proprietary characterization [85]. | Good adherence to ISO standards, detailed flow analysis [84]. | Presents impacts by life cycle phase [70]. |

| Visualization and Reporting | Colourful graphs, process network [72,79]. | Bar charts, top 5 indicators, Excel export [52]. | Fast results, advanced graphical interface [52]. | Clear visualizations and energy simulations [56]. | Automatic transport reports by city [73]. |

| Differentiators and Highlights | High reliability, strong adherence to ISO standards [60,84,85]. | Free, transparent, ideal for academic use [60,66] | Well-suited for EPDs and industrial applications [56,69]. | Recommended for material-based industries [67,78]. | Good for construction projects with minimal manual data input [65]. |

| Software | Negative |

|---|---|

| Athena | Limited to specific studies involving construction and building works [57]. Does not allow clear separation between life cycle stages [73]. Low flexibility in modelling and contains limitations regarding transparency of results [78,79]. Designed to cover information specific to North America [70,78]. Presents results as “Summary Measures” and “Absolute Value” [70]. |

| SimaPro | Greater complexity and less practicality in defining transportation [73]. Requires a higher technical level for modelling and interpreting results [53,64]. Considered time-consuming and complex [79]. To represent different usage conditions of certain products, it would be necessary to create entire alternative life cycles, which make modelling complex and artificial [74]. High dependency on obtaining primary data about operating equipment, requiring the search for reliable secondary data [62]. Mentioned as originally a stand-alone tool that evolved to client-server versions, but with low flexibility for integration with enterprise data systems [63]. Differences in structure and format between databases prevent direct integration with commercial software like SimaPro [63]. |

| Umberto | It is very robust and flexible; however, it requires a high learning effort and is recommended for experienced users [71]. The user needs to have a high level of knowledge to use the tool [53]. It does not offer significant innovations for some applications and is less friendly for beginners, with a steeper learning curve [52]. |

| Gabi LCA | The user needs to have a high level of knowledge to use the tool [53]. Has limitations in the number of available LCIA methods [52]. Its limitations may be linked to the use of a proprietary database connected to the software [60]. It has limited graphical impact but offers good cost–benefit for less complex applications [55]. Its complexity and limited focus on industrial sectors reduce its practicality (as seen in the automotive industry) [84,90]. Mentioned as a tool originally stand-alone that evolved to client-server versions, but with low flexibility for integration with enterprise data systems [63]. It is pointed out that it does not fully resolve data loss when converting between formats [81]. |

| OpenLCA | Does not allow subdivision of systems into sub-networks [56]. When there are many elements, the visualization can become cluttered and difficult to read [56]. The tool is focused on process impact assessment, and building product systems is more difficult. Additionally, the use phase has limited scope and little flexibility within the software’s modelling framework [74]. Doesnot meet with the Standard of Environmental management] requirements and requires impact assessment methods to be added manually, which limits its use [84]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Alves, V.S.d.S.; Bianchini, V.K.; Bezerra, B.S.; Razzino, C.d.A.; Andrade, F.N.d.S.; Neme, S.S. No One-Size-Fits-All: A Systematic Review of LCA Software and a Selection Framework. Sustainability 2026, 18, 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010197

Alves VSdS, Bianchini VK, Bezerra BS, Razzino CdA, Andrade FNdS, Neme SS. No One-Size-Fits-All: A Systematic Review of LCA Software and a Selection Framework. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010197

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlves, Veridiana Souza da Silva, Vivian Karina Bianchini, Barbara Stolte Bezerra, Carlos do Amaral Razzino, Fernanda Neves da Silva Andrade, and Sofia Seniciato Neme. 2026. "No One-Size-Fits-All: A Systematic Review of LCA Software and a Selection Framework" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010197

APA StyleAlves, V. S. d. S., Bianchini, V. K., Bezerra, B. S., Razzino, C. d. A., Andrade, F. N. d. S., & Neme, S. S. (2026). No One-Size-Fits-All: A Systematic Review of LCA Software and a Selection Framework. Sustainability, 18(1), 197. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010197