Culturally Sustainable Site Selection of Bazaars: A Spatial Analytics Approach in Ürümqi, Xinjiang

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Social Integration Value: Strategic positioning can enhance inter-ethnic interaction and community cohesion through improved accessibility and spatial arrangement [22].

- (2)

- Cultural Sustainability: Appropriate location selection strengthens the preservation and transmission of intangible cultural heritage within urban environments [23].

- (3)

- (4)

- Urban Planning Value: Integrated site selection contributes to improved urban functionality and governance efficiency [24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.1.1. Conceptual Definition: Bazaar Commercial District

2.1.2. Hierarchical Coupling Mechanisms

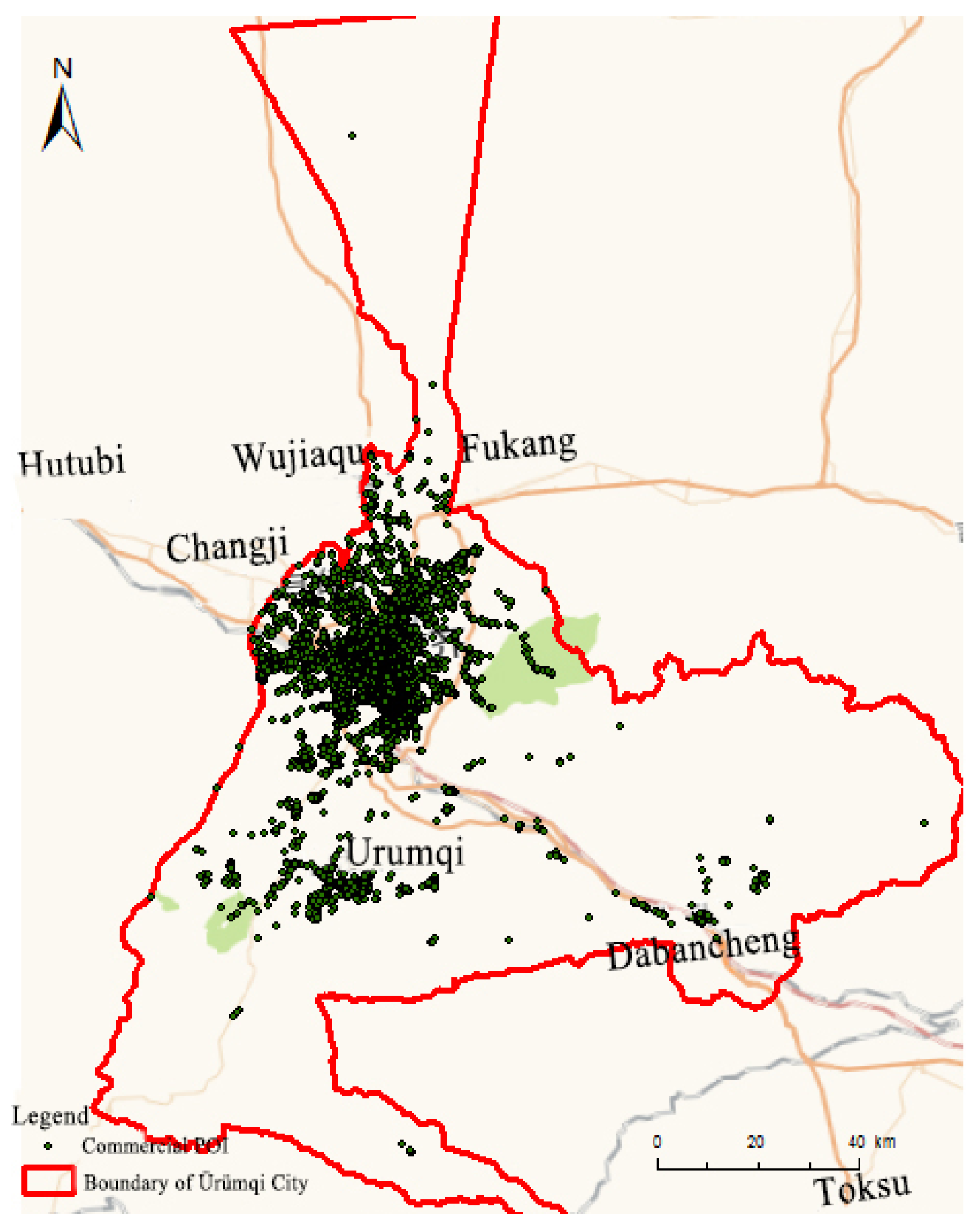

2.2. Data Sources and Preprocessing

2.2.1. Data Collection

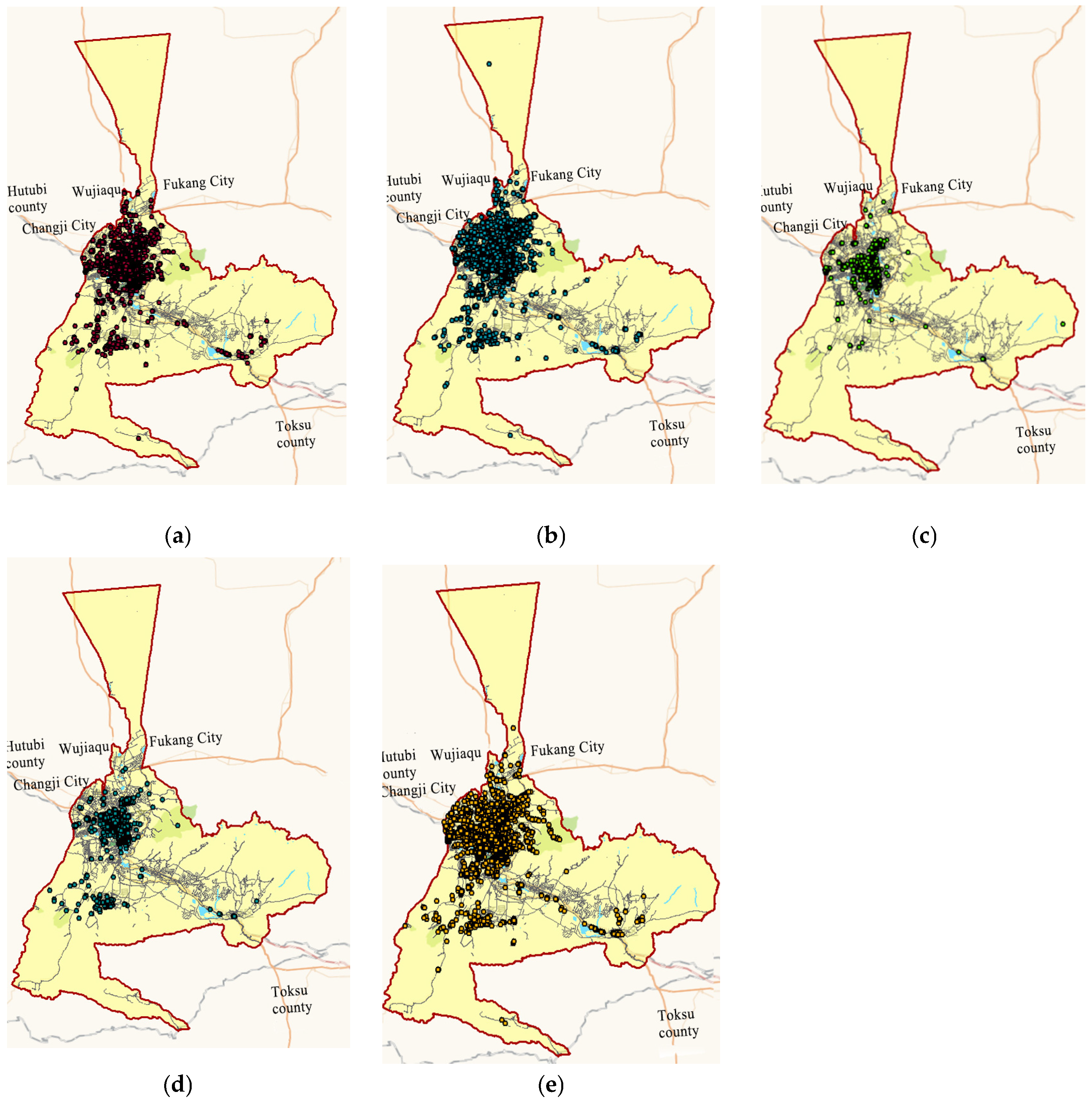

2.2.2. Data Categorization and Processing

2.2.3. Data Quality Assessment and Limitations

2.3. Analytical Framework and Modeling

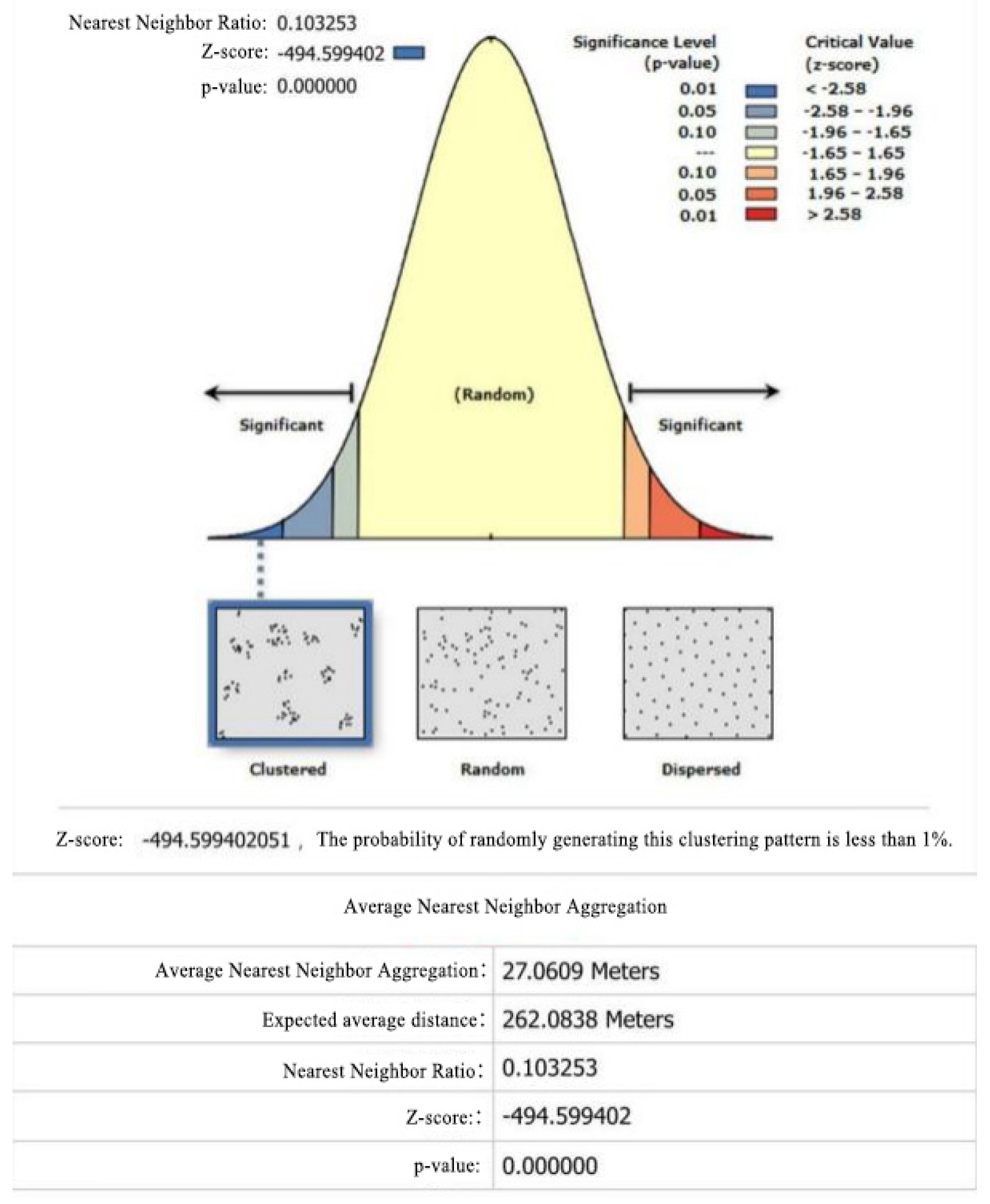

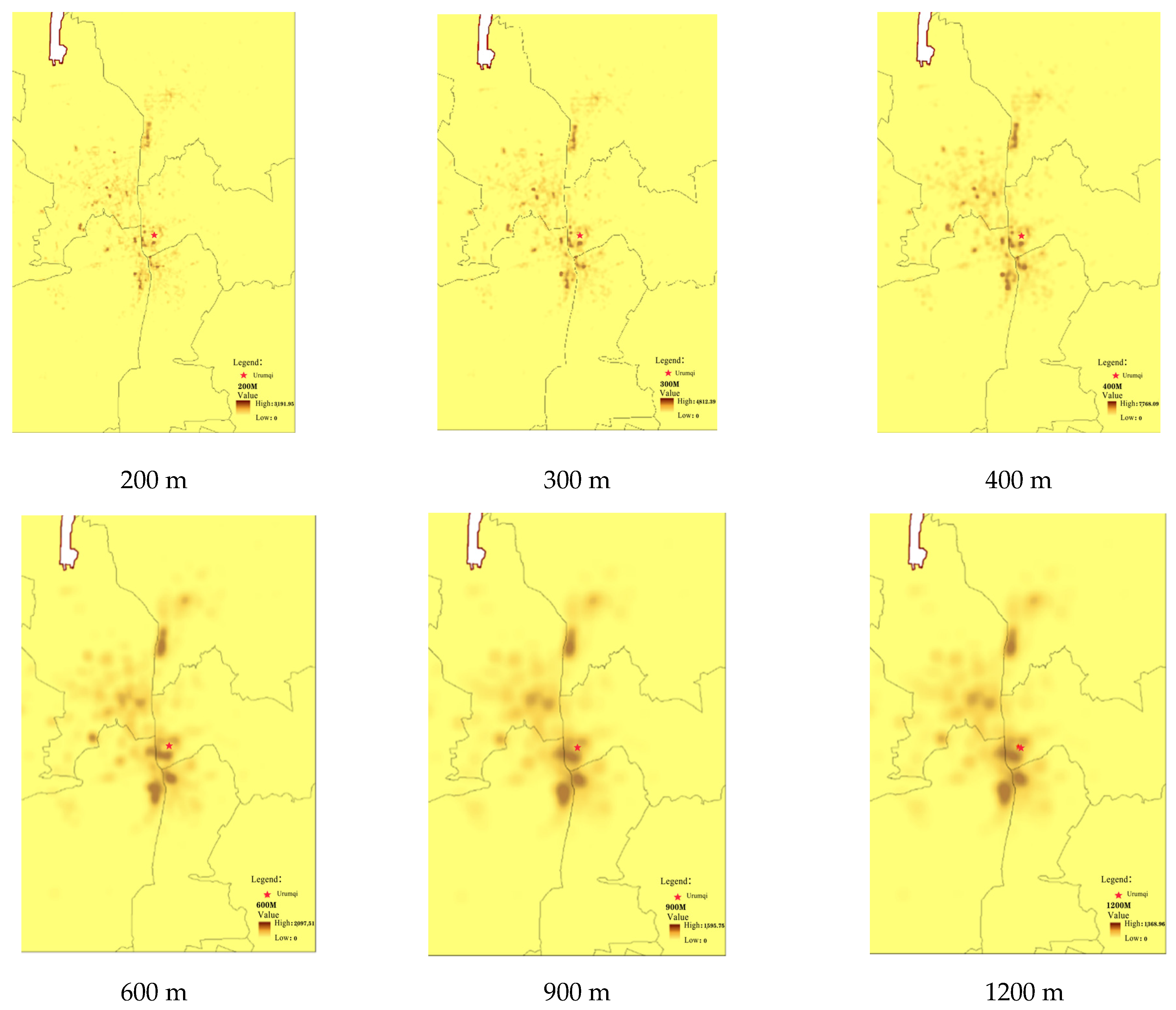

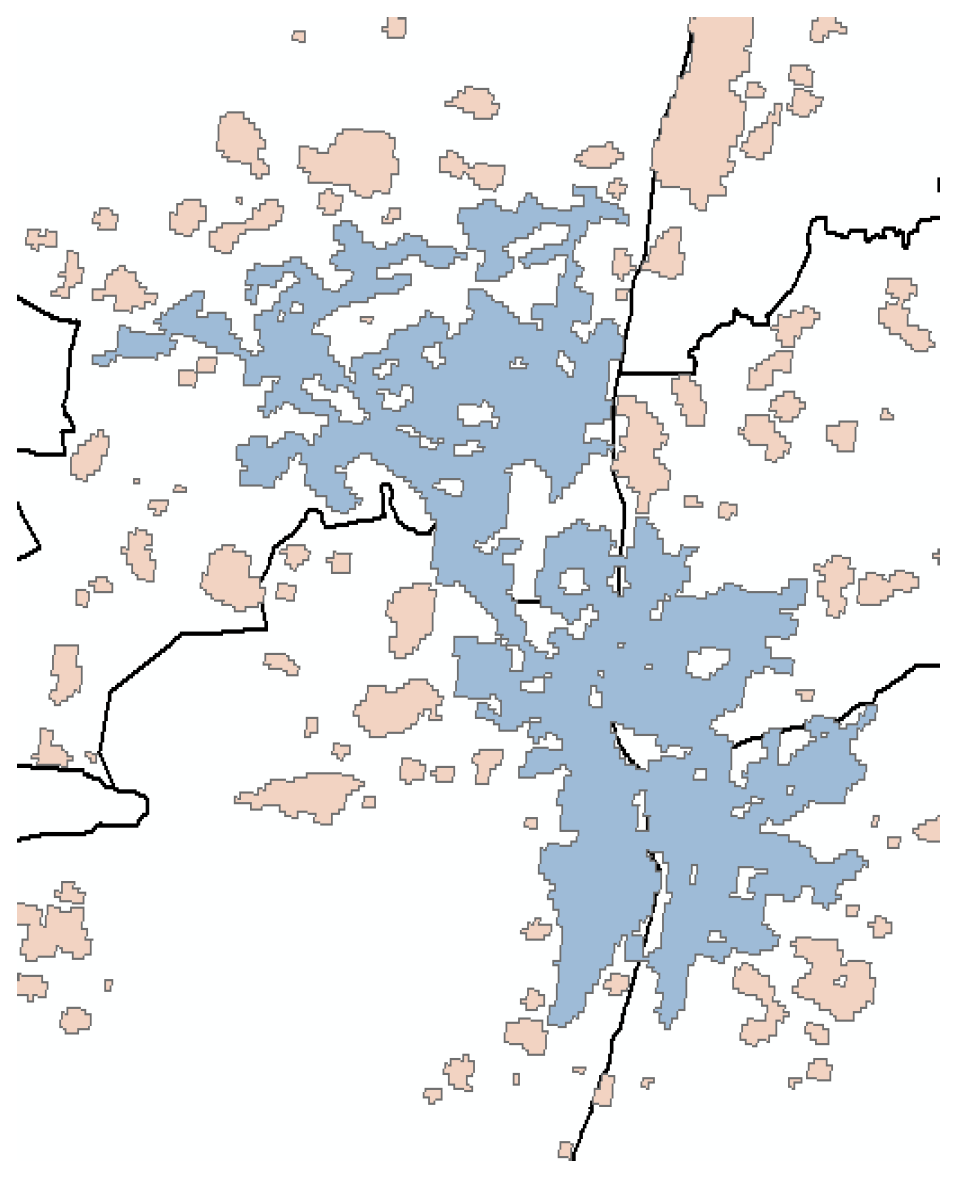

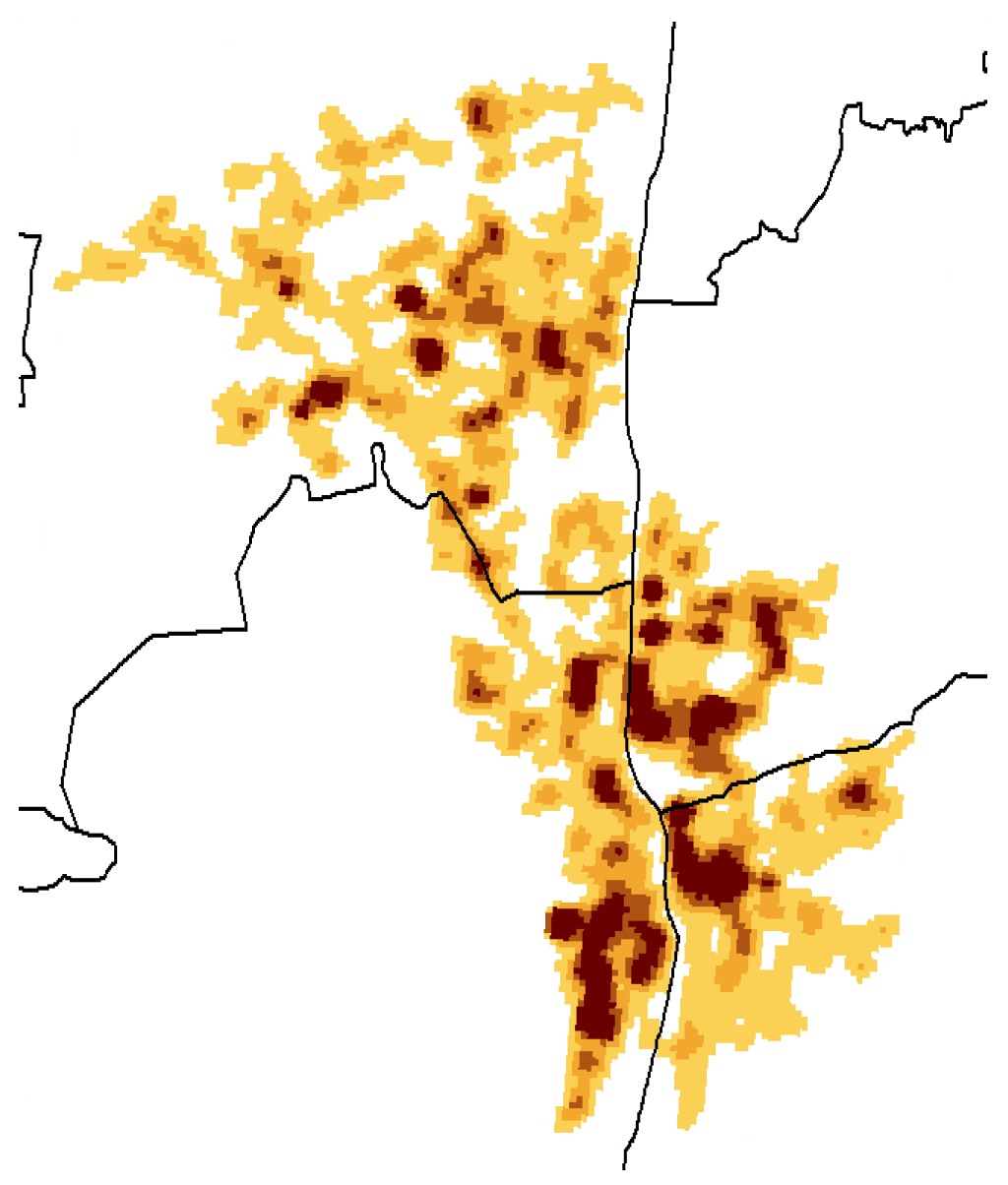

2.3.1. Spatial Agglomeration Analysis

- (1)

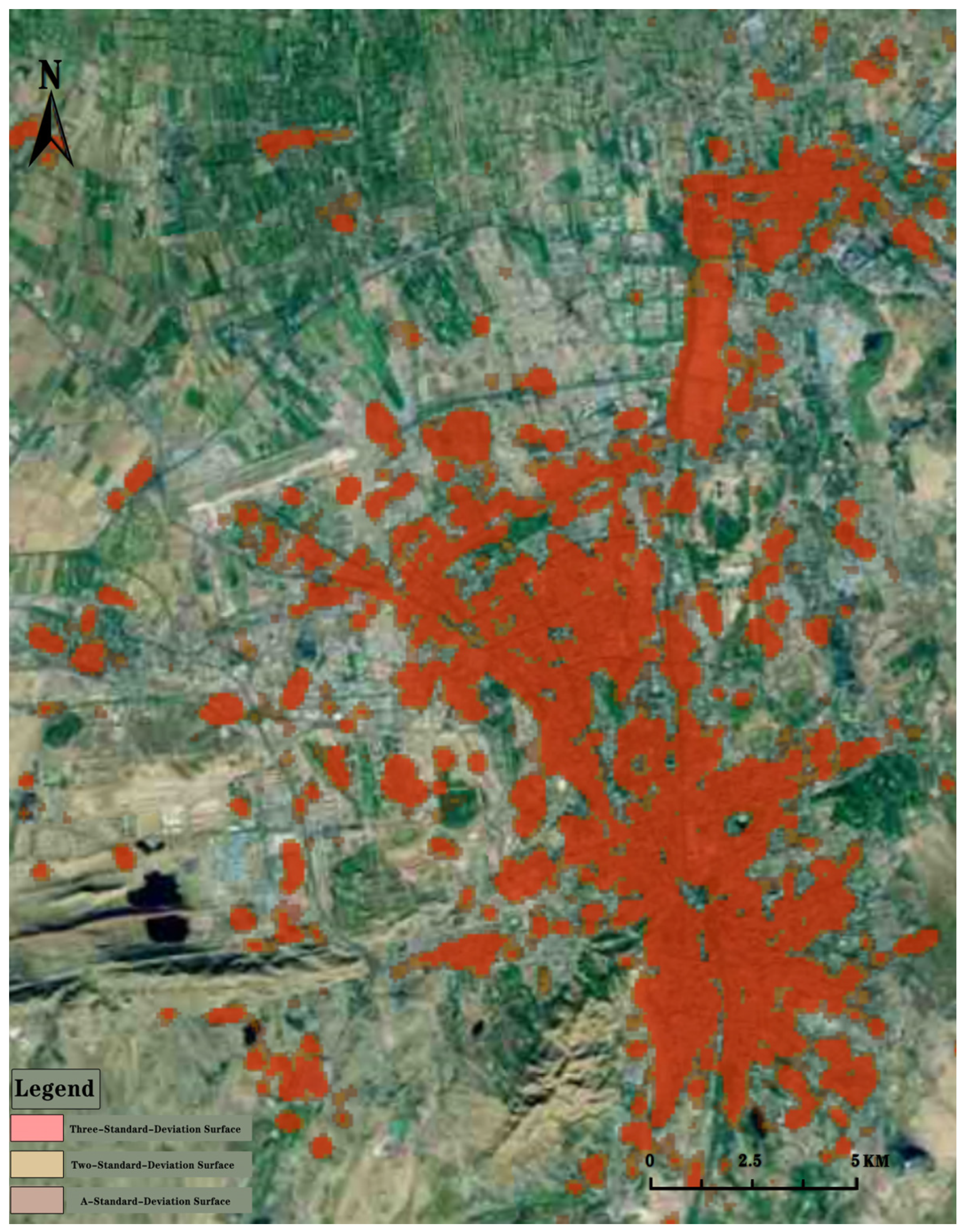

- Kernel Density Analysis Estimation:

- (2)

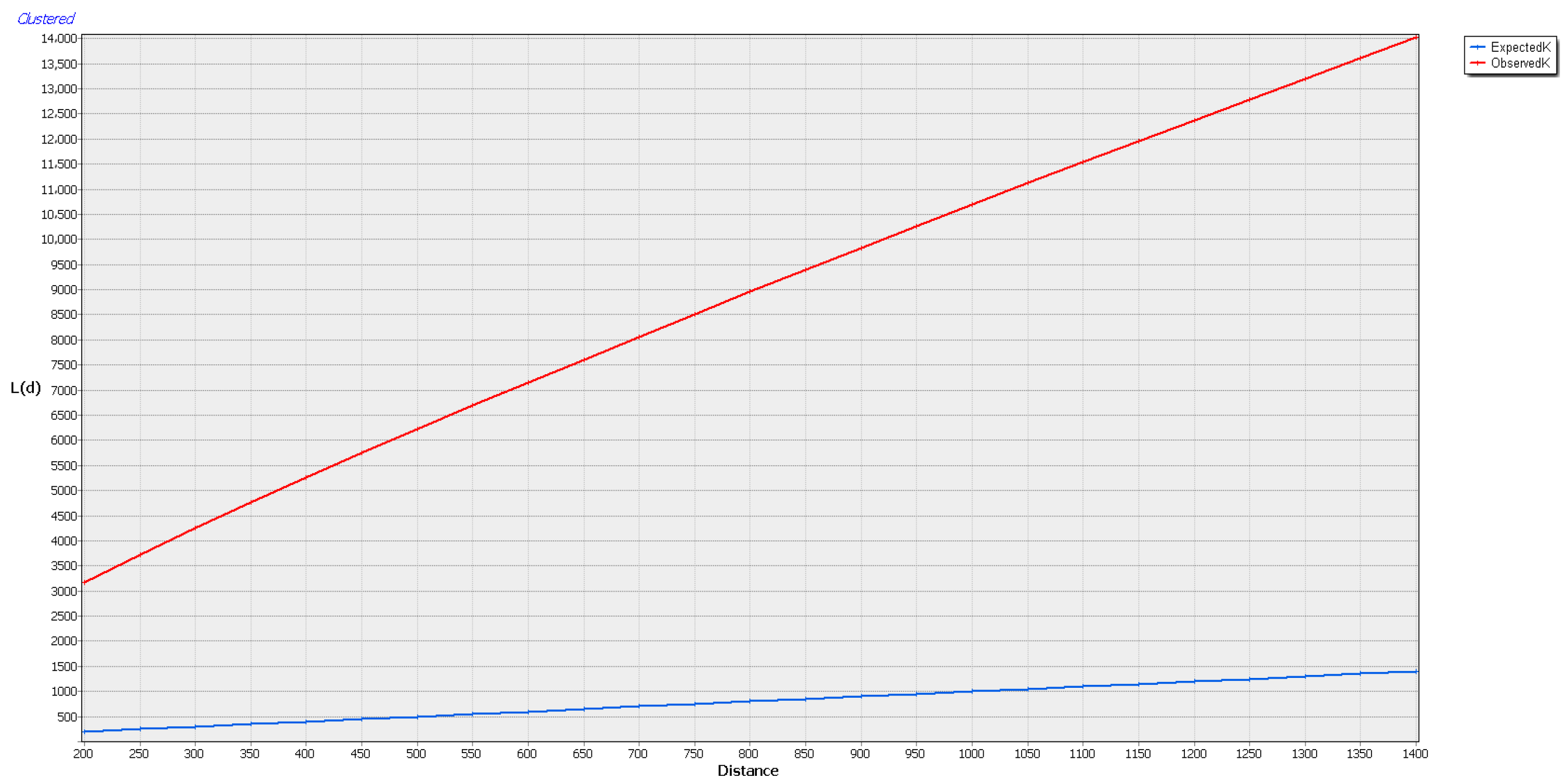

- Ripley’s K Function:

- (3)

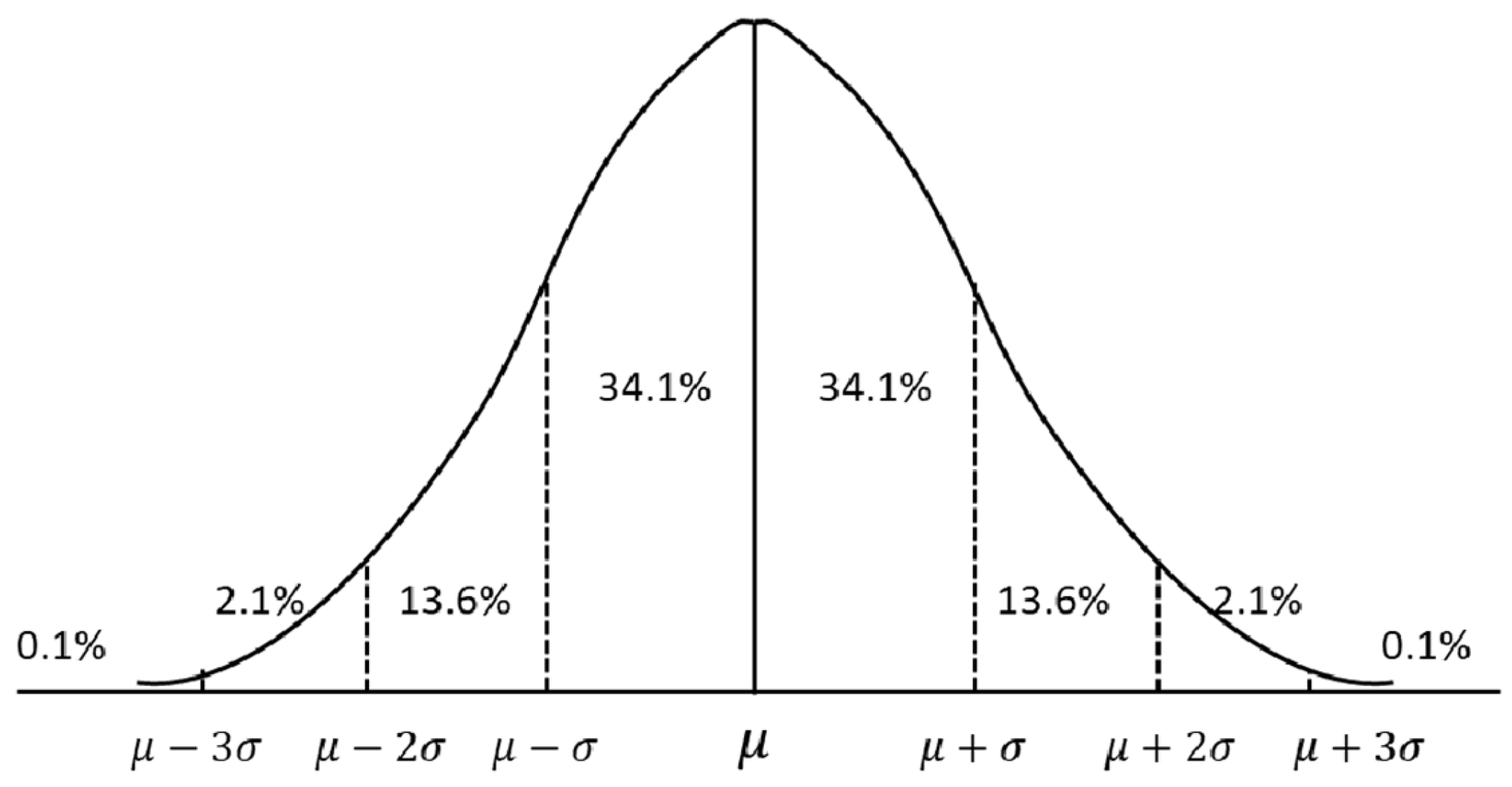

- Data Standardization Methods:

- (4)

- Weighted Integrated Scoring Method:

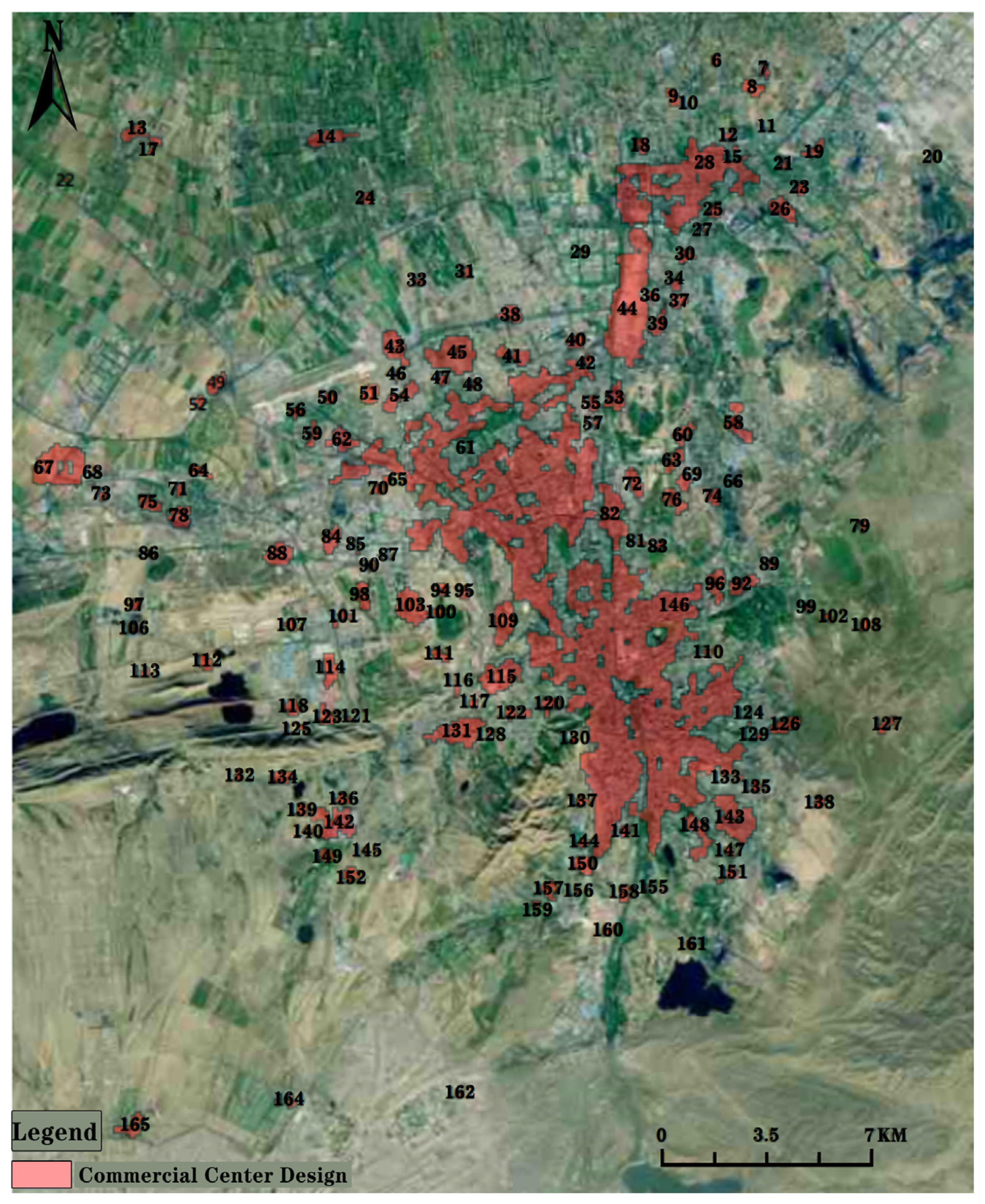

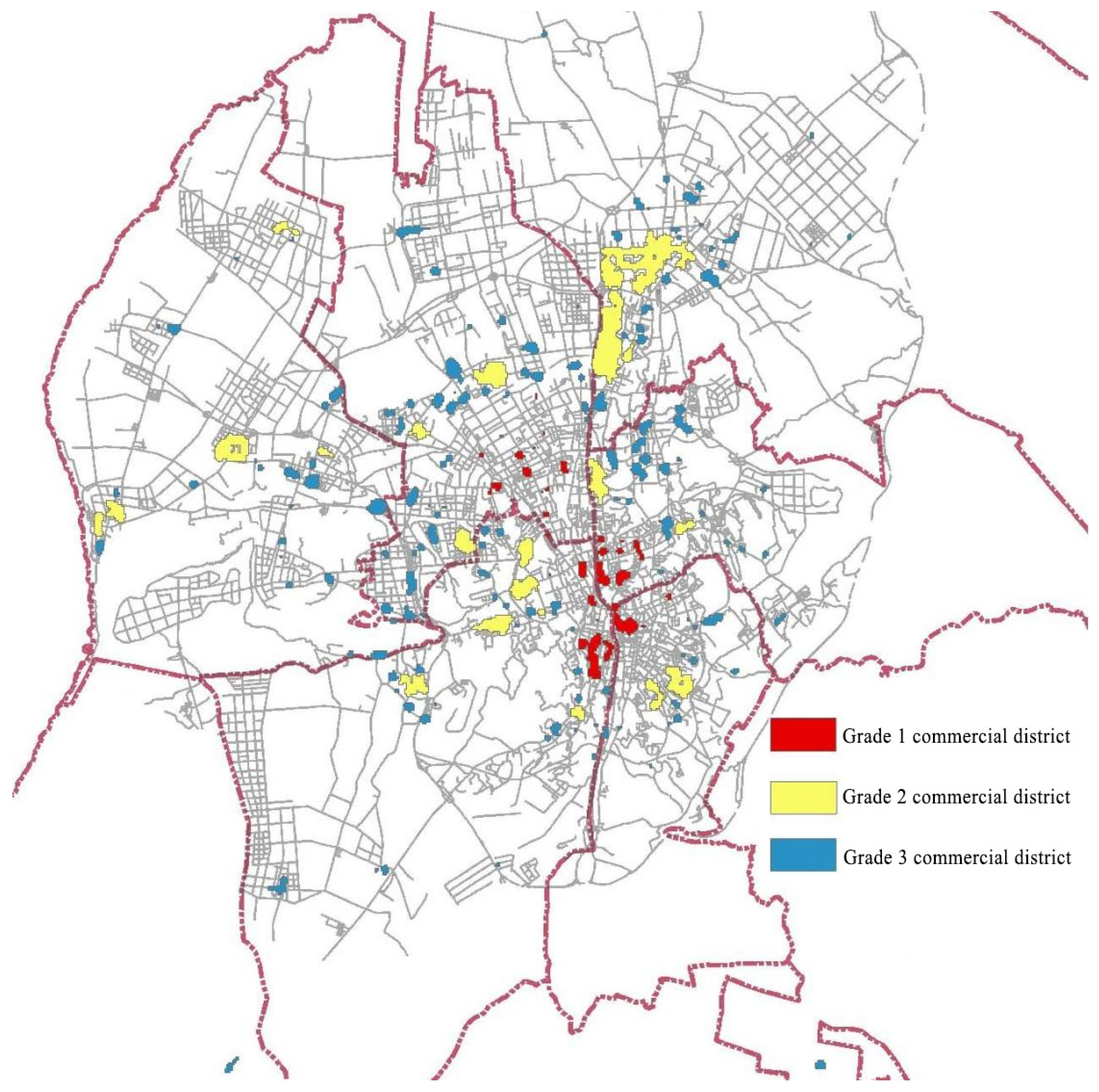

2.3.2. Delineation of Commercial District Boundaries

2.3.3. Bazaar Site Selection Model

- (1)

- Site Selection in Tier-1 Bazaar Business Districts When a bazaar is situated within a city’s primary business district, it is recommended to prioritize a “city-level” scale and positioning. In addition to their large scale, these bazaars typically integrate diverse cultural-commercial spaces and public service functions. They play a significant role in activating the nighttime economy and hold distinctive appeal for residents. The service orientation of their cultural-commercial spaces targets the entire urban population, often extending to surrounding cities [35].

- (2)

- Site Selection in Tier-2 Bazaar Business Districts For bazaars located in secondary business districts, a “regional- level” scale is recommended as the primary positioning, supplemented by a “city-level” orientation. Retail and entertainment formats occupy considerable space and primarily attract residents from the surrounding area. The diversity of integrated formats is generally more limited compared to city-level bazaars. The cultural-commercial services are consequently oriented toward serving residents of a specific urban region.

- (3)

- Site Selection in Tier-3 or Township Bazaar Business Districts Bazaars in tertiary business districts or town ship commercial areas should adopt a positioning that is primarily “regional-level” with a secondary “community-level” focus. They mainly serve residents from a specific urban region and surrounding communities. Food, beverage, and retail formats dominate the tenancy and attract patronage from local residents [36,37,38]. These bazaars incorporate a wider variety of formats than purely community-level ones, while their cultural-commercial services are tailored principally to the adjacent communities.

- (4)

- Site Selection Outside Formal Bazaar Business Districts For locations situated outside established business districts—characterized by a weaker commercial atmosphere and considerable distance from core commercial areas—a “community-level” scale is advised. These bazaars primarily serve immediate neighborhood residents and focus on essential commercial activities, offering a limited mix of formats or community services. The cultural-commercial function, consequently, is oriented almost exclusively toward the local community [39,40].

3. Results

3.1. Research on the Structural Characteristics of Commercial District Business Formats

Research on Structural Characteristics of Commercial Space Formats Across Different Types

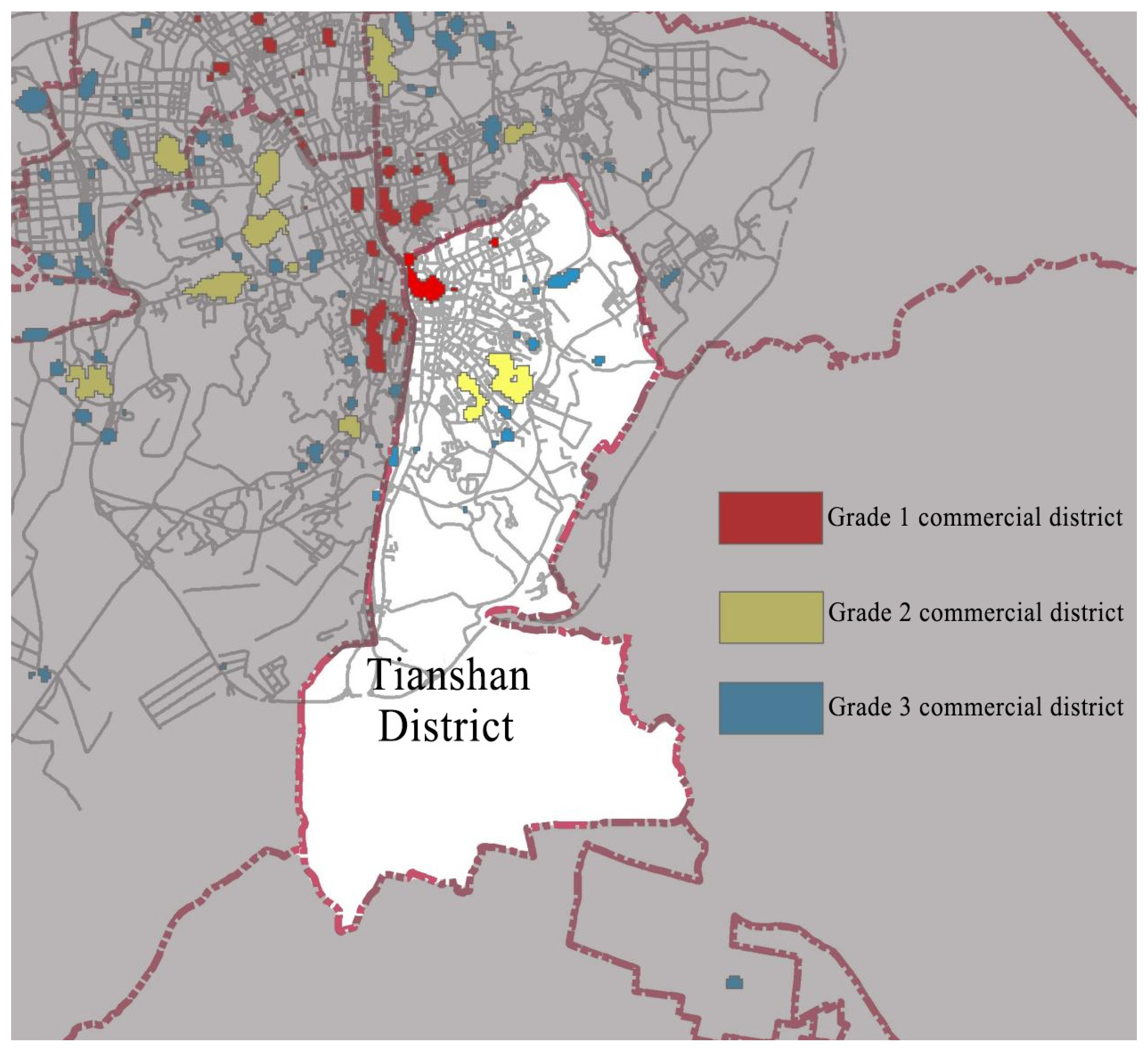

3.2. Identification and Demarcation of Bazaar Commercial Zone Boundaries

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Coupling Mechanisms Between Bazaar Location and Performance

- (1)

- Xiyu International Trade City. Although classified as a “city-level” bazaar, it is situated within a tertiary-level commercial district—a locational mismatch. Despite this, it maintains relatively successful operations. Field investigation revealed its customer base consists primarily of domestic and international merchants, with wholesale being the predominant sales model. Consequently, its location strategy prioritizes access for major commercial clients rather than local residents, emphasizing transportation access and parking availability. This unique operational focus makes it a special case where conventional proximity to urban commercial centers becomes less relevant.

- (2)

- Bianjiang International Trade City. This bazaar thrived two decades ago but has experienced operational decline in recent years due to space constraints, inadequate parking, poor spatial quality, and competition from the newer, larger Xiyu International Trade City. Its location within a tertiary commercial zone, combined with its substantial size, presents significant challenges for functional adaptation or revitalization.

- (3)

- Ürümqi County Ice-Snow Town Commercial Street. As established previously, Ürümqi County lacks conventional urban commercial districts, making it suitable only for community-level bazaar development. This project’s regional-scale capacity significantly exceeds local demand patterns. Consequently, it experiences seasonal viability dependent solely on winter skiing tourism, with markedly poor performance during other seasons.

- (4)

- Hongshan Dried Fruit Market. Although situated within a secondary urban commercial district, this case was excluded from our defined bazaar commercial zones due to the low ethnic minority population (23.30%) in its vicinity, falling below the threshold for culturally significant commercial clustering. The failure of this market stems from a fundamental product-market mismatch. Its core operational model focused exclusively on selling Xinjiang specialty dried fruits and local products—goods that are widely available throughout Ürümqi and lack a unique value proposition to differentiate this market as a distinctive destination for tourists. Simultaneously, this product offering did not align with the daily consumption needs of the local residential community, creating a disconnect with both potential customer bases. Compounding this issue, the market’s operational format—resembling a conventional wholesale-retail outlet—failed to provide the vibrant, experiential atmosphere characteristic of successful bazaars, where cultural interaction and sensory engagement are key attractions. Consequently, the market experienced overall operational failure, with only peripheral street-front food and beverage establishments currently maintaining viable operations due to their alignment with neighborhood service demands.

- (5)

- Xinjiang Minjie Shanxi Alley. This bazaar experienced initial success but subsequently declined due to a combination of locational disadvantages and strategic missteps. Its primary constraint is an unfavorable geographical position: situated away from principal urban thoroughfares with limited street frontage, significantly reducing its visibility and pedestrian accessibility. Compounding this issue was a pronounced strategic overreach. The project was ambitiously positioned as a “city-level” attraction intended to draw domestic and international tourists, an aspiration that proved misaligned with its actual location outside Ürümqi’s primary bazaar commercial zone. Development resources were disproportionately allocated to architectural esthetics and interior finishes, rather than cultivating a unique operational core competency. This led to a severe lack of differentiation from other commercial offerings and an absence of competitive vitality. Consequently, the bazaar suffers from extremely low tenancy and footfall; currently, only a fraction of the ground-floor units remain operational, while the upper levels are largely vacant and closed to the public.

4.2. Design Strategies and Planning Implications

- Implement hierarchical zoning regulations that match bazaar scale and function with appropriate commercial district tiers.

- Develop transitional development guidelines for areas between different commercial tiers to prevent strategic overreach.

- Establish accessibility-based site selection criteria that prioritize pedestrian connectivity and public transportation access.

- Create cultural vitality assessment tools incorporating ethnic population thresholds and intangible cultural heritage factors.

- Design experiential retail frameworks that emphasize cultural interaction, sensory engagement, and authentic atmosphere.

- Develop product-market matching mechanisms that align local specialties with both tourist and residential consumer needs.

- Formulate demand-based scaling guidelines that prevent oversized development in commercially underdeveloped areas.

- Implement seasonal adaptability strategies for tourism-dependent locations to ensure year-round viability.

- Establish functional conversion protocols for oversized or poorly located bazaars to facilitate adaptive reuse.

4.3. Validation and Theoretical Contribution

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Business Major | Commercial Subcategory | Quantity | Ratio | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Culinary Delights | Tea Lounge | 165 | 0.80% | 20,550 |

| Cake and Dessert Shop | 1195 | 5.82% | ||

| Coffee | 142 | 0.69% | ||

| Foreign Cuisine | 214 | 1.04% | ||

| Snacks and Fast Food | 2613 | 12.72% | ||

| Chinese Cuisine | 16,221 | 78.93% | ||

| Financial Institutions | ATM | 629 | 33.42% | 1882 |

| Insurance | 134 | 7.12% | ||

| Investment And Financial Management | 369 | 19.61% | ||

| Bank | 753 | 40.01% | ||

| Shopping And Consumption | Department Store | 104 | 0.29% | 35,407 |

| Convenience Store | 5739 | 16.21% | ||

| Supermarket | 922 | 2.60% | ||

| Shopping Center | 48 | 0.14% | ||

| Flowers, birds, fish, and insects | 438 | 1.24% | ||

| Home Appliances and Electronics | 1518 | 4.29% | ||

| Home Furnishings and Building Materials | 6949 | 19.63% | ||

| Duty-Free Shop | 13 | 0.04% | ||

| Commercial Street | 71 | 0.20% | ||

| Daily Necessities | 13,682 | 38.64% | ||

| Sports and stationery supplies | 696 | 1.97% | ||

| Market | 4218 | 11.91% | ||

| Exercise and Fitness | 1009 | 2.85% | ||

| Hotel Accommodations | Budget hotel chain | 81 | 4.29% | 1890 |

| Hotel | 1657 | 87.67% | ||

| Youth Hostel | 4 | 0.21% | ||

| Three-star hotel | 76 | 4.02% | ||

| Four-star hotel | 52 | 2.75% | ||

| Five-star/Luxury hotel | 20 | 1.06% | ||

| Lifestyle Services | KTV | 58 | 0.25% | 23,397 |

| Lottery Sales | 543 | 2.32% | ||

| Telecom Service Center | 479 | 2.05% | ||

| Cinema | 49 | 0.21% | ||

| Retirement Living | 111 | 0.47% | ||

| Public Utilities | 42 | 0.18% | ||

| Bar | 159 | 0.68% | ||

| Beauty Salon | 3659 | 15.64% | ||

| Farm Stay | 699 | 2.99% | ||

| Others | 3793 | 16.21% | ||

| Card and Board Game Room | 173 | 0.74% | ||

| Automotive-related | 6935 | 29.64% | ||

| Photo Printing | 679 | 2.90% | ||

| Internet Cafe | 119 | 0.51% | ||

| Logistics | 986 | 4.21% | ||

| Laundry | 364 | 1.56% | ||

| Bath and Massage | 824 | 3.52% | ||

| Information Consultation Center | 18 | 0.08% | ||

| Pharmaceutical Sales | 2285 | 9.77% | ||

| Post Office | 175 | 0.75% | ||

| Amusement Park | 55 | 0.24% | ||

| Agency | 1192 | 5.09% |

| Code Name | Number of Bus Stops | Large Shopping Mall | Number of Commercial Outlets | Types | Commercial Area (km2) | Road Network Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 3 | 0.01 | 10,002.81 |

| 2 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 3 | 0.1 | 7030.219 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 3 | 0.05 | 9378.248 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 31 | 3 | 0.07 | 6076.22 |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 4 | 0.06 | 0 |

| 6 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 3 | 0.1 | 4004.827 |

| 7 | 1 | 0 | 52 | 3 | 0.14 | 6699.731 |

| 8 | 3 | 0 | 153 | 3 | 0.32 | 4033.144 |

| 9 | 0 | 0 | 98 | 1 | 0.22 | 6635.766 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0.01 | 20,062.06 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 4 | 0.02 | 24,141.9 |

| 12 | 0 | 0 | 39 | 5 | 0.09 | 4435.902 |

| 13 | 3 | 1 | 197 | 5 | 0.46 | 7992.997 |

| 14 | 7 | 0 | 294 | 3 | 0.56 | 6167.645 |

| 15 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0.04 | 5013.364 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 2 | 0.05 | 3945.49 |

| 17 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0.03 | 5922.301 |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | 77 | 4 | 0.19 | 2639.236 |

| 19 | 2 | 0 | 94 | 3 | 0.24 | 11,464.2 |

| 20 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 0.01 | 6687.315 |

| 21 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 0.06 | 6646.724 |

| 22 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 3 | 0.03 | 12,497.29 |

| 23 | 3 | 0 | 62 | 4 | 0.14 | 7006.885 |

| 24 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 3 | 0.17 | 9633.737 |

| 25 | 2 | 0 | 87 | 3 | 0.19 | 8598.28 |

| 26 | 5 | 0 | 220 | 3 | 0.52 | 0 |

| 27 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0.01 | 213,176 |

| 28 | 48 | 7 | 3710 | 5 | 6.88 | 6615.145 |

| 29 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 4 | 0.02 | 5013.934 |

| 30 | 3 | 0 | 83 | 4 | 0.19 | 7837.607 |

| 31 | 0 | 1 | 68 | 3 | 0.13 | 4142.54 |

| 32 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 3 | 0.02 | 10,010.01 |

| 33 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 3 | 0.04 | 3508.338 |

| 34 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 3 | 0.14 | 12,075.84 |

| 35 | 0 | 0 | 120 | 4 | 0.29 | 5129.035 |

| 36 | 1 | 0 | 37 | 3 | 0.08 | 11,284.58 |

| 37 | 0 | 0 | 89 | 3 | 0.21 | 7629.972 |

| 38 | 5 | 0 | 159 | 4 | 0.35 | 7215.884 |

| 39 | 13 | 2 | 128 | 5 | 0.32 | 11,753.5 |

| 40 | 2 | 1 | 131 | 3 | 0.25 | 811.6033 |

| 41 | 10 | 1 | 353 | 4 | 0.43 | 7807.151 |

| 42 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 3 | 0.08 | 3236.85 |

| 43 | 2 | 0 | 585 | 4 | 0.7 | 3702.952 |

| 44 | 28 | 2 | 4830 | 5 | 4.64 | 5186.993 |

| 45 | 28 | 1 | 935 | 4 | 1.57 | 6030.729 |

| 46 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0.01 | 0 |

| 47 | 7 | 0 | 65 | 4 | 0.15 | 16,188.12 |

| 48 | 12 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 0.06 | 12,754.45 |

| 49 | 0 | 0 | 162 | 3 | 0.33 | 3540.737 |

| 50 | 2 | 0 | 54 | 3 | 0.13 | 4093.555 |

| 51 | 0 | 0 | 203 | 4 | 0.32 | 6157.512 |

| 52 | 0 | 0 | 46 | 3 | 0.11 | 2160.019 |

| 53 | 4 | 0 | 212 | 4 | 0.47 | 8984.155 |

| 54 | 3 | 0 | 221 | 4 | 0.51 | 10,659.65 |

| 55 | 2 | 0 | 57 | 3 | 0.16 | 2255.367 |

| 56 | 0 | 0 | 55 | 4 | 0.15 | 12,245.76 |

| 57 | 2 | 0 | 21 | 2 | 0.04 | 5133.852 |

| 58 | 9 | 0 | 283 | 4 | 0.62 | 9192.963 |

| 59 | 0 | 0 | 102 | 5 | 0.23 | 6133.657 |

| 60 | 2 | 2 | 124 | 3 | 0.33 | 9263.566 |

| 61 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 2 | 0.02 | 6338.113 |

| 62 | 16 | 1 | 281 | 5 | 0.51 | 10,736.45 |

| 63 | 5 | 0 | 115 | 4 | 0.33 | 9076.223 |

| 64 | 1 | 0 | 91 | 5 | 0.22 | 13,617.99 |

| 65 | 1 | 0 | 32 | 3 | 0.09 | 6205.643 |

| 66 | 2 | 0 | 17 | 3 | 0.03 | 3958.834 |

| 67 | 14 | 0 | 1066 | 5 | 1.85 | 6195.358 |

| 68 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 2 | 0.02 | 8744.065 |

| 69 | 0 | 0 | 124 | 3 | 0.23 | 9996.211 |

| 70 | 1 | 0 | 42 | 3 | 0.09 | 3978.691 |

| 71 | 3 | 0 | 54 | 4 | 0.13 | 4344.255 |

| 72 | 3 | 0 | 166 | 4 | 0.39 | 7930.483 |

| 73 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 2 | 0.07 | 0 |

| 74 | 11 | 0 | 100 | 5 | 0.25 | 8629.358 |

| 75 | 8 | 0 | 189 | 4 | 0.34 | 8941.877 |

| 76 | 3 | 0 | 281 | 4 | 0.44 | 9925.58 |

| 77 | 0 | 0 | 61 | 3 | 0.14 | 2508.618 |

| 78 | 9 | 0 | 271 | 4 | 0.46 | 10,916.79 |

| 79 | 0 | 0 | 42 | 3 | 0.08 | 7786.537 |

| 80 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 3 | 0.09 | 6682.585 |

| 81 | 1 | 0 | 25 | 2 | 0.05 | 4003.685 |

| 82 | 51 | 1 | 665 | 5 | 1.3 | 11,722.59 |

| 83 | 1 | 0 | 37 | 3 | 0.08 | 8209.109 |

| 84 | 6 | 0 | 261 | 5 | 0.39 | 6363.445 |

| 85 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0.01 | 1452.754 |

| 86 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 3 | 0.03 | 15,798.75 |

| 87 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 2 | 0.02 | 95.50135 |

| 88 | 4 | 1 | 459 | 3 | 0.61 | 6803.498 |

| 89 | 1 | 0 | 28 | 3 | 0.06 | 9621.84 |

| 90 | 0 | 0 | 30 | 2 | 0.07 | 2868.577 |

| 91 | 0 | 0 | 380 | 5 | 0.73 | 6273.33 |

| 92 | 9 | 0 | 226 | 5 | 0.45 | 14,732.17 |

| 93 | 4 | 2 | 263 | 5 | 0.5 | 6835.767 |

| 94 | 5 | 0 | 73 | 3 | 0.16 | 6870.481 |

| 95 | 2 | 1 | 67 | 3 | 0.13 | 17,117.09 |

| 96 | 10 | 0 | 203 | 4 | 0.5 | 12,225.49 |

| 97 | 4 | 0 | 55 | 3 | 0.11 | 12,135.89 |

| 98 | 10 | 0 | 182 | 4 | 0.38 | 8007.826 |

| 99 | 0 | 0 | 27 | 3 | 0.06 | 24,103.98 |

| 100 | 0 | 0 | 34 | 3 | 0.09 | 6157.684 |

| 101 | 4 | 0 | 43 | 4 | 0.09 | 7852.053 |

| 102 | 5 | 0 | 30 | 3 | 0.07 | 28,036.64 |

| 103 | 15 | 3 | 1309 | 5 | 0.93 | 11,849.29 |

| 104 | 1 | 1 | 119 | 4 | 0.25 | 9484.119 |

| 105 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 4 | 0.06 | 8352.634 |

| 106 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 0.01 | 10,179.83 |

| 107 | 1 | 0 | 54 | 3 | 0.11 | 8241.276 |

| 108 | 0 | 0 | 40 | 3 | 0.09 | 3931.09 |

| 109 | 14 | 0 | 460 | 5 | 0.87 | 8873.35 |

| 110 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 3 | 0.05 | 15,276.08 |

| 111 | 8 | 0 | 61 | 4 | 0.16 | 6181.829 |

| 112 | 0 | 1 | 104 | 4 | 0.18 | 4319.237 |

| 113 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 3 | 0.08 | 17,205.65 |

| 114 | 0 | 0 | 262 | 2 | 0.46 | 12,405.82 |

| 115 | 47 | 2 | 898 | 5 | 1.12 | 14,724.56 |

| 116 | 1 | 0 | 31 | 4 | 0.07 | 13,300.46 |

| 117 | 2 | 0 | 37 | 4 | 0.07 | 7798.386 |

| 118 | 2 | 0 | 142 | 3 | 0.24 | 4299.45 |

| 119 | 10 | 0 | 39 | 5 | 0.1 | 26,894.5 |

| 120 | 0 | 0 | 90 | 3 | 0.23 | 11,519.68 |

| 121 | 4 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 0.03 | 11,412.98 |

| 122 | 6 | 0 | 71 | 3 | 0.16 | 19,281 |

| 123 | 4 | 0 | 111 | 4 | 0.27 | 7186.834 |

| 124 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 0.02 | 5136.521 |

| 125 | 3 | 0 | 36 | 4 | 0.07 | 5728.426 |

| 126 | 2 | 0 | 259 | 3 | 0.42 | 6579.779 |

| 127 | 4 | 1 | 77 | 3 | 0.18 | 12,317.91 |

| 128 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 3 | 0.04 | 11,141.93 |

| 129 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 3 | 0.04 | 8673.574 |

| 130 | 2 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0.04 | 15,732.21 |

| 131 | 52 | 0 | 645 | 5 | 1.22 | 13,965.93 |

| 132 | 2 | 0 | 28 | 3 | 0.07 | 3893.127 |

| 133 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 4 | 0.04 | 12,660.85 |

| 134 | 4 | 0 | 161 | 5 | 0.31 | 2841.795 |

| 135 | 2 | 0 | 46 | 4 | 0.11 | 17,265.15 |

| 136 | 4 | 0 | 58 | 3 | 0.14 | 6463.699 |

| 137 | 3 | 0 | 65 | 4 | 0.13 | 13,569.26 |

| 138 | 1 | 0 | 46 | 3 | 0.09 | 0 |

| 139 | 2 | 0 | 94 | 3 | 0.18 | 2840.986 |

| 140 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 4 | 0.04 | 7546.298 |

| 141 | 0 | 0 | 56 | 3 | 0.13 | 10,628.52 |

| 142 | 8 | 0 | 457 | 5 | 1.08 | 5795.175 |

| 143 | 32 | 1 | 722 | 5 | 1.46 | 10,514.52 |

| 144 | 3 | 0 | 50 | 3 | 0.11 | 10,056.56 |

| 145 | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1 | 0.02 | 10,000.31 |

| 146 | 2127 | 97 | 41,732 | 5 | 60.25 | 11,645.4 |

| 147 | 4 | 0 | 59 | 3 | 0.12 | 19,658.42 |

| 148 | 25 | 6 | 334 | 5 | 0.71 | 9734.6 |

| 149 | 0 | 0 | 137 | 3 | 0.21 | 2302.422 |

| 150 | 17 | 0 | 194 | 5 | 0.38 | 14,705.68 |

| 151 | 2 | 0 | 57 | 4 | 0.14 | 14,108.75 |

| 152 | 1 | 0 | 118 | 3 | 0.2 | 6130.129 |

| 153 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 0.02 | 10,245.57 |

| 154 | 5 | 0 | 23 | 3 | 0.03 | 21,905.78 |

| 155 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 3 | 0.03 | 7506.487 |

| 156 | 0 | 0 | 16 | 3 | 0.02 | 9982.14 |

| 157 | 12 | 0 | 94 | 4 | 0.24 | 6368.833 |

| 158 | 2 | 0 | 61 | 3 | 0.15 | 4632.193 |

| 159 | 3 | 0 | 31 | 3 | 0.07 | 12,818.5 |

| 160 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 4 | 0.06 | 3080.419 |

| 161 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 3 | 0.02 | 5905.266 |

| 162 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 3 | 0.03 | 7348.327 |

| 163 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 1 | 0.03 | 0 |

| 164 | 0 | 0 | 47 | 4 | 0.13 | 2047.319 |

| 165 | 7 | 0 | 166 | 4 | 0.4 | 7539.799 |

| 166 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 5 | 0.18 | 12,324.54 |

| 167 | 10 | 0 | 86 | 4 | 0.21 | 10,205.93 |

| 168 | 0 | 0 | 52 | 4 | 0.1 | 6177.964 |

| 169 | 1 | 0 | 65 | 4 | 0.16 | 18,651.49 |

| 170 | 1 | 1 | 163 | 5 | 0.28 | 6577.65 |

| 171 | 4 | 0 | 107 | 5 | 0.26 | 8877.142 |

| 172 | 8 | 1 | 178 | 5 | 0.35 | 5250.789 |

| Code | NORMALIZED AREA | Bus Stop Density | Number of Large Shopping Malls | Commercial Outlets | Types | Road Network Density | Total Score | Total Score × 1000 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.5000 | 0.0469 | 0.0214 | 21.3910 |

| 2 | 0.0015 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.5000 | 0.0330 | 0.0203 | 20.2513 |

| 3 | 0.0007 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.5000 | 0.0440 | 0.0213 | 21.3256 |

| 4 | 0.0010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.5000 | 0.0285 | 0.0193 | 19.3308 |

| 5 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.7500 | 0.0000 | 0.0226 | 22.5877 |

| 6 | 0.0015 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0188 | 0.0182 | 18.2171 |

| 7 | 0.0022 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.5000 | 0.0314 | 0.0204 | 20.4319 |

| 8 | 0.0051 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0036 | 0.5000 | 0.0189 | 0.0205 | 20.5178 |

| 9 | 0.0035 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.0311 | 0.0063 | 6.3427 |

| 10 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.2500 | 0.0941 | 0.0206 | 20.6393 |

| 11 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.7500 | 0.1132 | 0.0382 | 38.2012 |

| 12 | 0.0013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0009 | 1.0000 | 0.0208 | 0.0332 | 33.1808 |

| 13 | 0.0075 | 0.0014 | 0.0103 | 0.0047 | 1.0000 | 0.0375 | 0.0401 | 40.1470 |

| 14 | 0.0091 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0070 | 0.5000 | 0.0289 | 0.0245 | 24.4944 |

| 15 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0235 | 0.0184 | 18.3553 |

| 16 | 0.0007 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.2500 | 0.0185 | 0.0104 | 10.3728 |

| 17 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0278 | 0.0189 | 18.8548 |

| 18 | 0.0030 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0018 | 0.7500 | 0.0124 | 0.0256 | 25.5936 |

| 19 | 0.0038 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0022 | 0.5000 | 0.0538 | 0.0246 | 24.5677 |

| 20 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.2500 | 0.0314 | 0.0118 | 11.8089 |

| 21 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.5000 | 0.0312 | 0.0196 | 19.6162 |

| 22 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0586 | 0.0232 | 23.2188 |

| 23 | 0.0022 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.7500 | 0.0329 | 0.0282 | 28.1620 |

| 24 | 0.0027 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0019 | 0.5000 | 0.0452 | 0.0226 | 22.6220 |

| 25 | 0.0030 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0020 | 0.5000 | 0.0403 | 0.0222 | 22.2458 |

| 26 | 0.0085 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0052 | 0.5000 | 0.0000 | 0.0198 | 19.7818 |

| 27 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.1409 | 140.9409 |

| 28 | 0.1140 | 0.0226 | 0.0722 | 0.0889 | 1.0000 | 0.0310 | 0.1093 | 109.3166 |

| 29 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.7500 | 0.0235 | 0.0256 | 25.5502 |

| 30 | 0.0030 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0019 | 0.7500 | 0.0368 | 0.0292 | 29.1723 |

| 31 | 0.0020 | 0.0000 | 0.0103 | 0.0016 | 0.5000 | 0.0194 | 0.0196 | 19.6393 |

| 32 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0470 | 0.0215 | 21.4680 |

| 33 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0165 | 0.0174 | 17.3579 |

| 34 | 0.0022 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.5000 | 0.0566 | 0.0239 | 23.9298 |

| 35 | 0.0046 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0028 | 0.7500 | 0.0241 | 0.0281 | 28.1007 |

| 36 | 0.0012 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0529 | 0.0229 | 22.9345 |

| 37 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0021 | 0.5000 | 0.0358 | 0.0216 | 21.6472 |

| 38 | 0.0056 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0038 | 0.7500 | 0.0338 | 0.0304 | 30.3855 |

| 39 | 0.0051 | 0.0061 | 0.0206 | 0.0030 | 1.0000 | 0.0551 | 0.0430 | 42.9590 |

| 40 | 0.0040 | 0.0009 | 0.0103 | 0.0031 | 0.5000 | 0.0038 | 0.0187 | 18.7016 |

| 41 | 0.0070 | 0.0047 | 0.0103 | 0.0084 | 0.7500 | 0.0366 | 0.0332 | 33.2265 |

| 42 | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0152 | 0.0175 | 17.5477 |

| 43 | 0.0115 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0140 | 0.7500 | 0.0174 | 0.0318 | 31.7764 |

| 44 | 0.0769 | 0.0132 | 0.0206 | 0.1157 | 1.0000 | 0.0243 | 0.0864 | 86.4153 |

| 45 | 0.0259 | 0.0132 | 0.0103 | 0.0224 | 0.7500 | 0.0283 | 0.0440 | 43.9614 |

| 46 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.2500 | 0.0000 | 0.0074 | 7.3828 |

| 47 | 0.0023 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0015 | 0.7500 | 0.0759 | 0.0346 | 34.5760 |

| 48 | 0.0008 | 0.0056 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.5000 | 0.0598 | 0.0244 | 24.4182 |

| 49 | 0.0053 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0038 | 0.5000 | 0.0166 | 0.0201 | 20.1051 |

| 50 | 0.0020 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.5000 | 0.0192 | 0.0187 | 18.6953 |

| 51 | 0.0051 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0048 | 0.7500 | 0.0289 | 0.0292 | 29.2281 |

| 52 | 0.0017 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.5000 | 0.0101 | 0.0171 | 17.1062 |

| 53 | 0.0076 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0050 | 0.7500 | 0.0421 | 0.0326 | 32.6038 |

| 54 | 0.0083 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0052 | 0.7500 | 0.0500 | 0.0340 | 33.9979 |

| 55 | 0.0025 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.5000 | 0.0106 | 0.0177 | 17.7334 |

| 56 | 0.0023 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.7500 | 0.0574 | 0.0315 | 31.4997 |

| 57 | 0.0005 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.2500 | 0.0241 | 0.0112 | 11.1892 |

| 58 | 0.0101 | 0.0042 | 0.0000 | 0.0067 | 0.7500 | 0.0431 | 0.0345 | 34.4629 |

| 59 | 0.0037 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0024 | 1.0000 | 0.0288 | 0.0356 | 35.6046 |

| 60 | 0.0053 | 0.0009 | 0.0206 | 0.0029 | 0.5000 | 0.0435 | 0.0259 | 25.9338 |

| 61 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.2500 | 0.0297 | 0.0117 | 11.6819 |

| 62 | 0.0083 | 0.0075 | 0.0103 | 0.0067 | 1.0000 | 0.0504 | 0.0434 | 43.4023 |

| 63 | 0.0053 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0027 | 0.7500 | 0.0426 | 0.0313 | 31.3446 |

| 64 | 0.0035 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0021 | 1.0000 | 0.0639 | 0.0405 | 40.5077 |

| 65 | 0.0013 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.5000 | 0.0291 | 0.0196 | 19.6465 |

| 66 | 0.0003 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0186 | 0.0177 | 17.6962 |

| 67 | 0.0305 | 0.0066 | 0.0000 | 0.0255 | 1.0000 | 0.0291 | 0.0522 | 52.1641 |

| 68 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.2500 | 0.0410 | 0.0133 | 13.2531 |

| 69 | 0.0037 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0029 | 0.5000 | 0.0469 | 0.0235 | 23.4605 |

| 70 | 0.0013 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0010 | 0.5000 | 0.0187 | 0.0182 | 18.1985 |

| 71 | 0.0020 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.7500 | 0.0204 | 0.0263 | 26.3002 |

| 72 | 0.0063 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0039 | 0.7500 | 0.0372 | 0.0311 | 31.0757 |

| 73 | 0.0010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.2500 | 0.0000 | 0.0079 | 7.9429 |

| 74 | 0.0040 | 0.0052 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 | 1.0000 | 0.0405 | 0.0381 | 38.1141 |

| 75 | 0.0055 | 0.0038 | 0.0000 | 0.0045 | 0.7500 | 0.0419 | 0.0317 | 31.7083 |

| 76 | 0.0071 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0067 | 0.7500 | 0.0466 | 0.0331 | 33.0838 |

| 77 | 0.0022 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.5000 | 0.0118 | 0.0176 | 17.6191 |

| 78 | 0.0075 | 0.0042 | 0.0000 | 0.0064 | 0.7500 | 0.0512 | 0.0343 | 34.2610 |

| 79 | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0010 | 0.5000 | 0.0365 | 0.0206 | 20.5703 |

| 80 | 0.0013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0313 | 0.0199 | 19.9079 |

| 81 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.2500 | 0.0188 | 0.0105 | 10.4701 |

| 82 | 0.0214 | 0.0240 | 0.0103 | 0.0159 | 1.0000 | 0.0550 | 0.0537 | 53.6945 |

| 83 | 0.0012 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0385 | 0.0209 | 20.9012 |

| 84 | 0.0063 | 0.0028 | 0.0000 | 0.0062 | 1.0000 | 0.0299 | 0.0378 | 37.8366 |

| 85 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0068 | 0.0157 | 15.7309 |

| 86 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.5000 | 0.0741 | 0.0254 | 25.4063 |

| 87 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.2500 | 0.0004 | 0.0075 | 7.5450 |

| 88 | 0.0100 | 0.0019 | 0.0103 | 0.0110 | 0.5000 | 0.0319 | 0.0265 | 26.5391 |

| 89 | 0.0008 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.5000 | 0.0451 | 0.0216 | 21.6493 |

| 90 | 0.0010 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.2500 | 0.0135 | 0.0098 | 9.8322 |

| 91 | 0.0120 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0091 | 1.0000 | 0.0294 | 0.0405 | 40.4728 |

| 92 | 0.0073 | 0.0042 | 0.0000 | 0.0054 | 1.0000 | 0.0691 | 0.0440 | 43.9678 |

| 93 | 0.0081 | 0.0019 | 0.0206 | 0.0063 | 1.0000 | 0.0321 | 0.0409 | 40.9388 |

| 94 | 0.0025 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0017 | 0.5000 | 0.0322 | 0.0210 | 21.0144 |

| 95 | 0.0020 | 0.0009 | 0.0103 | 0.0016 | 0.5000 | 0.0803 | 0.0283 | 28.3422 |

| 96 | 0.0081 | 0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.0048 | 0.7500 | 0.0573 | 0.0354 | 35.3531 |

| 97 | 0.0017 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.5000 | 0.0569 | 0.0240 | 23.9781 |

| 98 | 0.0061 | 0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.0043 | 0.7500 | 0.0376 | 0.0315 | 31.5293 |

| 99 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.5000 | 0.1131 | 0.0312 | 31.1579 |

| 100 | 0.0013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0289 | 0.0196 | 19.5560 |

| 101 | 0.0013 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0010 | 0.7500 | 0.0368 | 0.0283 | 28.3282 |

| 102 | 0.0010 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.5000 | 0.1315 | 0.0342 | 34.1655 |

| 103 | 0.0153 | 0.0071 | 0.0309 | 0.0313 | 1.0000 | 0.0556 | 0.0520 | 52.0232 |

| 104 | 0.0040 | 0.0005 | 0.0103 | 0.0028 | 0.7500 | 0.0445 | 0.0317 | 31.7181 |

| 105 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.7500 | 0.0392 | 0.0281 | 28.1220 |

| 106 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0478 | 0.0215 | 21.5007 |

| 107 | 0.0017 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.5000 | 0.0387 | 0.0212 | 21.2098 |

| 108 | 0.0013 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0009 | 0.5000 | 0.0184 | 0.0181 | 18.0985 |

| 109 | 0.0143 | 0.0066 | 0.0000 | 0.0110 | 1.0000 | 0.0416 | 0.0444 | 44.4256 |

| 110 | 0.0007 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.5000 | 0.0717 | 0.0253 | 25.3376 |

| 111 | 0.0025 | 0.0038 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.7500 | 0.0290 | 0.0281 | 28.0965 |

| 112 | 0.0028 | 0.0000 | 0.0103 | 0.0024 | 0.7500 | 0.0203 | 0.0276 | 27.6291 |

| 113 | 0.0012 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.5000 | 0.0807 | 0.0268 | 26.7855 |

| 114 | 0.0075 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0062 | 0.2500 | 0.0582 | 0.0199 | 19.8996 |

| 115 | 0.0184 | 0.0221 | 0.0206 | 0.0215 | 1.0000 | 0.0691 | 0.0555 | 55.5181 |

| 116 | 0.0010 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.7500 | 0.0624 | 0.0315 | 31.5462 |

| 117 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.7500 | 0.0366 | 0.0280 | 27.9868 |

| 118 | 0.0038 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0034 | 0.5000 | 0.0202 | 0.0199 | 19.9472 |

| 119 | 0.0015 | 0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.0009 | 1.0000 | 0.1262 | 0.0487 | 48.7477 |

| 120 | 0.0037 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0021 | 0.5000 | 0.0540 | 0.0244 | 24.3853 |

| 121 | 0.0003 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0535 | 0.0227 | 22.7371 |

| 122 | 0.0025 | 0.0028 | 0.0000 | 0.0017 | 0.5000 | 0.0904 | 0.0293 | 29.2783 |

| 123 | 0.0043 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0026 | 0.7500 | 0.0337 | 0.0295 | 29.5299 |

| 124 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.5000 | 0.0241 | 0.0183 | 18.2581 |

| 125 | 0.0010 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0008 | 0.7500 | 0.0269 | 0.0267 | 26.6795 |

| 126 | 0.0068 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0062 | 0.5000 | 0.0309 | 0.0232 | 23.2152 |

| 127 | 0.0028 | 0.0019 | 0.0103 | 0.0018 | 0.5000 | 0.0578 | 0.0257 | 25.7310 |

| 128 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.5000 | 0.0523 | 0.0224 | 22.4096 |

| 129 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.5000 | 0.0407 | 0.0208 | 20.7801 |

| 130 | 0.0005 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0738 | 0.0256 | 25.5693 |

| 131 | 0.0201 | 0.0244 | 0.0000 | 0.0154 | 1.0000 | 0.0655 | 0.0535 | 53.5315 |

| 132 | 0.0010 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 0.5000 | 0.0183 | 0.0180 | 18.0075 |

| 133 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.7500 | 0.0594 | 0.0308 | 30.7966 |

| 134 | 0.0050 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0038 | 1.0000 | 0.0133 | 0.0345 | 34.4822 |

| 135 | 0.0017 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.7500 | 0.0810 | 0.0346 | 34.5956 |

| 136 | 0.0022 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.5000 | 0.0303 | 0.0205 | 20.4813 |

| 137 | 0.0020 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0015 | 0.7500 | 0.0637 | 0.0324 | 32.4259 |

| 138 | 0.0013 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.5000 | 0.0000 | 0.0156 | 15.5777 |

| 139 | 0.0028 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0022 | 0.5000 | 0.0133 | 0.0184 | 18.3744 |

| 140 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.7500 | 0.0354 | 0.0274 | 27.4152 |

| 141 | 0.0020 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.5000 | 0.0499 | 0.0229 | 22.8933 |

| 142 | 0.0178 | 0.0038 | 0.0000 | 0.0109 | 1.0000 | 0.0272 | 0.0437 | 43.7239 |

| 143 | 0.0241 | 0.0150 | 0.0103 | 0.0173 | 1.0000 | 0.0493 | 0.0531 | 53.1369 |

| 144 | 0.0017 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.5000 | 0.0472 | 0.0225 | 22.5276 |

| 145 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0469 | 0.0067 | 6.7251 |

| 146 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.0546 | 0.8655 | 865.4780 |

| 147 | 0.0018 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.5000 | 0.0922 | 0.0290 | 29.0432 |

| 148 | 0.0116 | 0.0118 | 0.0619 | 0.0080 | 1.0000 | 0.0457 | 0.0501 | 50.1071 |

| 149 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0032 | 0.5000 | 0.0108 | 0.0182 | 18.2414 |

| 150 | 0.0061 | 0.0080 | 0.0000 | 0.0046 | 1.0000 | 0.0690 | 0.0438 | 43.8077 |

| 151 | 0.0022 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0013 | 0.7500 | 0.0662 | 0.0328 | 32.7815 |

| 152 | 0.0032 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0028 | 0.5000 | 0.0288 | 0.0207 | 20.7075 |

| 153 | 0.0002 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0481 | 0.0219 | 21.9470 |

| 154 | 0.0003 | 0.0024 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.5000 | 0.1028 | 0.0298 | 29.7671 |

| 155 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | 0.5000 | 0.0352 | 0.0199 | 19.9216 |

| 156 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.5000 | 0.0468 | 0.0215 | 21.4666 |

| 157 | 0.0038 | 0.0056 | 0.0000 | 0.0022 | 0.7500 | 0.0299 | 0.0292 | 29.2111 |

| 158 | 0.0023 | 0.0009 | 0.0000 | 0.0014 | 0.5000 | 0.0217 | 0.0192 | 19.2325 |

| 159 | 0.0010 | 0.0014 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.5000 | 0.0601 | 0.0240 | 23.9794 |

| 160 | 0.0008 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0.7500 | 0.0145 | 0.0246 | 24.6194 |

| 161 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 0.5000 | 0.0277 | 0.0188 | 18.7664 |

| 162 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.5000 | 0.0345 | 0.0198 | 19.7976 |

| 163 | 0.0003 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.1883 |

| 164 | 0.0020 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0011 | 0.7500 | 0.0096 | 0.0246 | 24.5737 |

| 165 | 0.0065 | 0.0033 | 0.0000 | 0.0039 | 0.7500 | 0.0354 | 0.0312 | 31.1541 |

| 166 | 0.0028 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0022 | 1.0000 | 0.0578 | 0.0393 | 39.2656 |

| 167 | 0.0033 | 0.0047 | 0.0000 | 0.0020 | 0.7500 | 0.0479 | 0.0314 | 31.3551 |

| 168 | 0.0015 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0012 | 0.7500 | 0.0290 | 0.0271 | 27.0706 |

| 169 | 0.0025 | 0.0005 | 0.0000 | 0.0015 | 0.7500 | 0.0875 | 0.0359 | 35.9047 |

| 170 | 0.0045 | 0.0005 | 0.0103 | 0.0039 | 1.0000 | 0.0309 | 0.0375 | 37.5249 |

| 171 | 0.0042 | 0.0019 | 0.0000 | 0.0025 | 1.0000 | 0.0416 | 0.0379 | 37.9312 |

| 172 | 0.0056 | 0.0038 | 0.0103 | 0.0042 | 1.0000 | 0.0246 | 0.0377 | 37.7039 |

| Number | Names of Bazaar in Xinjiang | Number of Retail Units | Scale Level | Commercial District Tier | Is the Site Selection Relationship Appropriate | Types of Cultural Commercial Spaces | Actual Operational Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Western Regions International Trade City | 953 | City-level | Level 3 | No | Less | Generally |

| 2 | Border International Trade City | 830 | City-level | Level 3 | No | Less | Poor |

| 3 | Erdaoqiao Grand Bazaar | 282 | Regional level | Level 1 | Yes | More | Better |

| 4 | Celestial Realm City | 550 | City-level | Level 1 | Yes | More | Better |

| 5 | Xinjiang Min Street, Shanxi Lane | 820 | City-level | Level 3 | No | More | v |

| 6 | International Bazaar | 350 | City-level | Level 1 | Yes | More | Well |

| 7 | Yongfeng Town Market | 150 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | Less | Better |

| 8 | Shuimogou Village Reemployment Market | 46 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | None | Better |

| 9 | Urumqi County Harmony Shopping Center | 50 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | None | Better |

| 10 | Urumqi County Snow Town Specialty Commercial Street | 100 | Regional level | Non-commercial district | No | Less | Poor |

| 11 | Dabancheng Farmers’ Market | 74 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | None | Better |

| 12 | Hualong Meite Commercial Street | 305 | Community-level | Level 3 | Yes | Less | Better |

| 13 | Hongshan Dried Fruit Market | 420 | Regional level | Level 2 | No | Less | Poor |

| 14 | Shuixigou Permanent Shop Street | 50 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | None | Better |

| 15 | Reed Village Job Fair | 57 | Community-level | Non-commercial district | Yes | None | Better |

References

- Kim, S.; Han, J. Characteristics of urban sustainability in the cases of multi commercial complexes from the perspective of the “ground”. Sustainability 2016, 8, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. Common Spaces of Multi-Commercial Complexes from Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puchkov, M. Complex construction: Urban design principles and the basis of sustainable development. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 962, 032047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veretennikov, D.B.; Kozlova, M.A. Design and construction of multifunctional high-rise complexes as a stage to creation of vertical cities. Urban Constr. Archit. 2022, 12, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JongYoon, K.; HyunSu, K. A Study on the Functional Characteristics of Large-scale Mixed-use Complex. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2010, 45, 149–163. [Google Scholar]

- Sahito, N.; Han, H.; Thi Nguyen, T.V.; Kim, I.; Hwang, J.; Jameel, A. Examining the quasi-public spaces in commercial complexes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. A study on the changing architectural properties of mixed-use commercial complexes in Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamošaitienė, J.; Khosravi, M.; Cristofaro, M.; Chan, D.W.; Sarvari, H. Identification and prioritization of critical risk factors of commercial and recreational complex building projects: A Delphi study using the TOPSIS method. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasimin, T.H.; Ali, H.M.; Razali, M.N.M.; Daud, S.M. Potential Opportunities of Blockchain Technology in Streamlining the Malaysian Commercial Office Building Operation Management Process. Plan. Malays. 2023, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.H.; To, W.M.; Lee, P.K. Smart building management system (SBMS) for commercial buildings—key attributes and usage intentions from building professionals’ perspective. Sustainability 2022, 15, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, P.J.; Hoyler, M.; Verbruggen, R. External urban relational process: Introducing central flow theory to complement central place theory. Urban Stud. 2010, 47, 2803–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.A.; Memon, M.A.; Prokop, M.; Kim, K.-S. An AHP/TOPSIS-based approach for an optimal site selection of a commercial opening utilizing geospatial data. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Big Data and Smart Computing (BigComp), Busan, Repbulic of Korea, 19–22 February 2020; pp. 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Hulse, K.; Reynolds, M. Investification: Financialisation of housing markets and persistence of suburban socio-economic disadvantage. Urban Stud. 2018, 55, 1655–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, S.; Gohari, H. Transition from Detached Plazas Close to Traditional Bazaars towards Reviving Lost Spaces Close to Contemporary Shopping Centres, Case Studies: Proma Shopping Center and Bazaar-E Reza in Mashhad. Arman. Archit. Urban Dev. 2013, 5, 175–190. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, B.; Messinger, P.R.; Habib, K. Post-Pandemic Retail Design: Human Relationships with Nature and Customer Loyalty—A Case of the Grand Bazaar Tehran. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Fan, T.; Wang, H.; Yang, Z. A comparative study of bazaar cultural spaces in Central Asia and China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalan, A.; Oliveira, E. A sustainable architecture approach to the economic and social aspects of the bazaar of Tabriz. MPRA 2014, 19, 53245. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, K.; Behzadfar, M.; Hamzenejad, M. Iranian bazaars and the social sustainability of modern commercial spaces in Iranian cities. J. Constr. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdinezhad, J.; Sedghpour, B.S.; Nabi, R.N. An evaluation of the influence of environmental, social and cultural factors on the socialization of traditional urban spaces (Case study: Iranian markets). Environ. Urban. ASIA 2020, 11, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Zhu, J. Informality and rural industry: Rethinking the impacts of E-Commerce on rural development in China. J. Rural. Stud. 2020, 75, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourzakarya, M.; Bahramjerdi, S.F.N. Towards developing a cultural and creative quarter: Culture-led regeneration of the historical district of Rasht Great Bazaar, Iran. Land Use Policy 2019, 89, 104218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourjafar, M.; Amini, M.; Varzaneh, E.H.; Mahdavinejad, M. Role of bazaars as a unifying factor in traditional cities of Iran: The Isfahan bazaar. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rukayah, R.S. Bazaar in Urban Open Space as Contain and Container Case study: Alun-alun Lama and Simpang Lima Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 50, 741–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, N.; Brown, C.; Bramley, G. The key to sustainable urban development in UK cities? The influence of density on social sustainability. Prog. Plan. 2012, 77, 89–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimzadeh, M. Survival of bazaars: Global spatial impact and local self-organising processes. Integration 2003, 2, 77.1–77.18. [Google Scholar]

- Khastou, M. Spatial Aspects Affecting the Vitality of An Iranian Traditional Bazaar: The Case of Qazvin Bazaar. METU JFA 2022, 39, 47–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, M.S. Bazaar and its role in the development of Iranian traditional cities. In Proceedings of the Conference Proceedings 2005 IRCICA International Conference of Islamic Archaeology, Istanbul, Turkey, 8–10 April 2005; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shokouhi Bidhendi, M.; Shadkam, S. The Birth of the Bazaar in the Iranian City: An Assessment of the Hypotheses on the Emergence of the First Bazaars in Iran. Soffeh 2023, 33, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitrakar, R.M. Meaning of public space and sense of community: The case of new neighbourhoods in the Kathmandu Valley. ArchNet-IJAR 2016, 10, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southworth, M. Reinventing main street: From mall to townscape mall. J. Urban Des. 2005, 10, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, S. Generating the Spirit of Space in the Expo Site, Building a Charming Urban Image an Analysis on the Public Space in the Shanghai Expo Site. Time Arch. 2009, 4, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Seaman, D.E.; Powell, R.A. An evaluation of the accuracy of kernel density estimators for home range analysis. Ecology 1996, 77, 2075–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Węglarczyk, S. Kernel density estimation and its application. ITM Web Conf. 2018, 23, 00037. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.J.; Mendis, G.P.; Triebe, M.J.; Sutherland, J.W. Monitoring of a machining process using kernel principal component analysis and kernel density estimation. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1175–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, A.; Nazir, H.; Memon, R.M. Shopping centers versus traditional open street bazaars: A comparative study of user’s preference in the city of Karachi, Pakistan. Front. Built Environ. 2022, 8, 1066093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, A.; Fallah, S.N. Role of social indicators on vitality parameter to enhance the quality of women׳ s communal life within an urban public space (case: Isfahan’s traditional bazaar, Iran). Front. Archit. Res. 2018, 7, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.; El Ouardighi, F.; Kim, B. Economic and environmental impacts of vertical and horizontal competition and integration. Nav. Res. Logist. 2019, 66, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.L.; Anderson, T.D.; Cruz, J.M. Consumer environmental awareness and competition in two-stage supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 218, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T. The Preference Study on Public Service of the Bazaar in Xinjiang. Adv. Educ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Res. 2023, 4, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleki, M.A.; Valibeigi, M.; Fanid, A.P.A.T.; Ranjbarnia, B.; Ghasemi, M. Public Parking Site Selection using GIS Case Study: Around Tabriz Traditional Bazaar. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/333175479_Public_Parking_Site_Selection_using_GIS_Case_study_around_Tabriz_traditional_bazaar (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Yue, Y.; Zhuang, Y.; Yeh, A.G.; Xie, J.-Y.; Ma, C.-L.; Li, Q.-Q. Measurements of POI-based mixed use and their relationships with neighbourhood vibrancy. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2017, 31, 658–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psyllidis, A.; Gao, S.; Hu, Y.; Kim, E.-K.; McKenzie, G.; Purves, R.; Yuan, M.; Andris, C. Points of Interest (POI): A commentary on the state of the art, challenges, and prospects for the future. Comput. Urban Sci. 2022, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14308-2023; Star-Rating Standard for Tourist Hotels. China National Standards: Beijing, China, 2010.

| Similarities | Differences | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bazaars of all sizes | The basic functions are the same | Partially incorporates religious functions | Cultural activities prefer outdoor open spaces | Regional style design as the main focus | Operators are predominantly ethnic minorities |

| Municipal Trade Market Commercial Complex | rarely incorporates religious functions | Cultural activities prefer indoor open spaces | Modernist style design as the main theme | The operators are predominantly Han Chinese. | |

| Business District Tier | Recommended Bazaar Scale and Positioning | Primary Service Orientation |

|---|---|---|

| Tier-1 | “City-level” | Serves the entire urban population and even surrounding cities; integrates diverse cultural-commercial functions and activates the nighttime economy. |

| Tier-2 | “Regional-level” (primary), with “City-level” as supplementary | Serves residents of a specific urban region; features sizable retail and entertainment formats. |

| Tier-3 | “Regional-level” (primary), with “Community-level” as supplementary | Serves a specific urban region and surrounding communities; dominated by food, beverage, and retail formats. |

| Non-Bazaar District | “Community-level” | Serves immediate neighborhood residents with essential commercial activities and a limited mix of formats or community services. |

| POI Category | Subclass | Number of POIs | Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| culinary delights | tea lounge, cake and dessert shop, coffee, international cuisine, snacks and fast food, Chinese cuisine | 20,550 | 24.72% |

| shopping and consumption | department stores, convenience stores, supermarkets, shopping malls, pet shops, electronics and appliances, home furnishings and building materials, duty-free shops, commercial streets, daily necessities, stationery and sports goods, markets, fitness and sports | 35,407 | 42.59% |

| financial institutions | ATM, insurance, investment and wealth management, banking | 1882 | 2.26% |

| hotel accommodations | budget chain hotels, inns, hostels, three-star, four-star, five-star hotels | 1890 | 2.27% |

| lifestyle services | KTV, lottery sales, telecom retail stores, cinemas, retirement resorts, public utilities, bars, beauty salons and hairdressers, farm stay tourism, card and board game rooms, automotive services, photo printing, internet cafes, logistics, laundry, bath and massage, information services, pharmaceutical sales, post offices, amusement parks, agencies, other | 23,397 | 28.15% |

| Total | 83,126 | 100.00% |

| OBJECTID | ExpectedK | ObservedK | DiffK |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200 | 3161.517189 | 2961.517189 |

| 2 | 250 | 3719.492922 | 3469.492922 |

| 3 | 300 | 4249.512465 | 3949.512465 |

| 4 | 350 | 4761.089132 | 4411.089132 |

| 5 | 400 | 5258.365377 | 4858.365377 |

| 6 | 450 | 5743.804796 | 5293.804796 |

| 7 | 500 | 6218.964006 | 5718.964006 |

| 8 | 550 | 6688.426251 | 6138.426251 |

| 9 | 600 | 7153.738643 | 6553.738643 |

| 10 | 650 | 7612.675103 | 6962.675103 |

| 11 | 700 | 8066.070798 | 7366.070798 |

| 12 | 750 | 8515.216424 | 7765.216424 |

| 13 | 800 | 8959.809914 | 8159.809914 |

| 14 | 850 | 9400.173351 | 8550.173351 |

| 15 | 900 | 9837.661634 | 8937.661634 |

| 16 | 950 | 10,272.16684 | 9322.166843 |

| 17 | 1000 | 10,702.86948 | 9702.869477 |

| 18 | 1050 | 11,128.38804 | 10,078.38804 |

| 19 | 1100 | 11,547.78695 | 10,447.78695 |

| 20 | 1150 | 11,963.7555 | 10,813.7555 |

| 21 | 1200 | 12,379.19353 | 11,179.19353 |

| 22 | 1250 | 12,793.24566 | 11,543.24566 |

| 23 | 1300 | 13,205.15475 | 11,905.15475 |

| 24 | 1350 | 13,615.9597 | 12,265.9597 |

| 25 | 1400 | 14,024.76547 | 12,624.76547 |

| Region | Area (km2) | POI Quantity | POI Density | Area Ratio | Ratio of Quantities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Standard-Deviation Area | 111.78 | 71,682 | 641.2775 | 0.78% | 86.24% |

| Area of two standard deviations | 141.86 | 75,461 | 531.9399 | 0.99% | 90.79% |

| One standard deviation area | 190.41 | 78,825 | 413.9751 | 1.33% | 94.83% |

| Urumqi City | 14,301.26 | 83,120 | 5.812075 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Major Factors | Level 1 Weight | Subcategory Factors | Secondary Weight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial scale | 59.538 | Commercial district land area | 0.837 |

| Number of commercial outlets | 0.173 | ||

| Commercial-grade quality | 12.827 | Number of large shopping malls | 0.862 |

| Business Categories | 0.148 | ||

| External business factors | 27.635 | Road network density | 0.516 |

| Bus frequency | 0.494 |

| Various Areas of Ürümqi | Han Chinese | Ethnic Minorities | Total Number of People | Percentage of Ethnic Minorities (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tianshan District | 274,064 | 186,430 | 460,494 | 40.48 |

| Shaibak District | 358,250 | 108,859 | 467,109 | 23.30 |

| High-Tech Zone | 412,617 | 92,696 | 505,313 | 18.34 |

| Shuimogou District | 180,740 | 51,804 | 232,544 | 22.28 |

| Tou Tunhe District | 147,477 | 48,700 | 196,177 | 24.82 |

| Dabancheng District | 10,515 | 22,003 | 32,518 | 67.66 |

| Midong District | 193,887 | 81,753 | 275,640 | 29.66 |

| Urumqi County | 18,206 | 34,557 | 52,763 | 65.49 |

| Business District Tier | Recommended Bazaar Scale and Positioning | Primary Service Orientation |

|---|---|---|

| Case Study | Primary Reason for Non-Conformance | Underlying Failure Factors |

| Xiyu International Trade City | Specialized Operational Model |

|

| Bianjiang International Trade City | Physical and Competitive Obsolescence |

|

| Xinjiang Minjie Shanxi Alley | Strategic Overreach and Locational Disadvantage |

|

| Ürümqi County Ice-Snow Town | Scale-to-Demand Mismatch |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, T.; Xu, H.; Cao, C.; Li, B. Culturally Sustainable Site Selection of Bazaars: A Spatial Analytics Approach in Ürümqi, Xinjiang. Sustainability 2026, 18, 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010151

Fan T, Xu H, Cao C, Li B. Culturally Sustainable Site Selection of Bazaars: A Spatial Analytics Approach in Ürümqi, Xinjiang. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010151

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Tao, Hao Xu, Chunbo Cao, and Bing Li. 2026. "Culturally Sustainable Site Selection of Bazaars: A Spatial Analytics Approach in Ürümqi, Xinjiang" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010151

APA StyleFan, T., Xu, H., Cao, C., & Li, B. (2026). Culturally Sustainable Site Selection of Bazaars: A Spatial Analytics Approach in Ürümqi, Xinjiang. Sustainability, 18(1), 151. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010151