Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Chlorophyll-a in Shenzhen’s Nearshore Waters: Insights from High-Frequency Buoy Observations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Station Distribution and Data Acquisition

2.3. Season Division

2.4. The Method for Analyzing the Spatiotemporal Characteristics of Chlorophyll-a

3. Results

3.1. Spatiotemporal Distribution of Monitoring Parameters

3.1.1. Chlorophyll-a

3.1.2. Water Quality Parameters

3.1.3. Meteorological Parameters

3.2. Data Statistical Analysis Results

3.2.1. Correlation Analysis

3.2.2. Linear Mixed Model

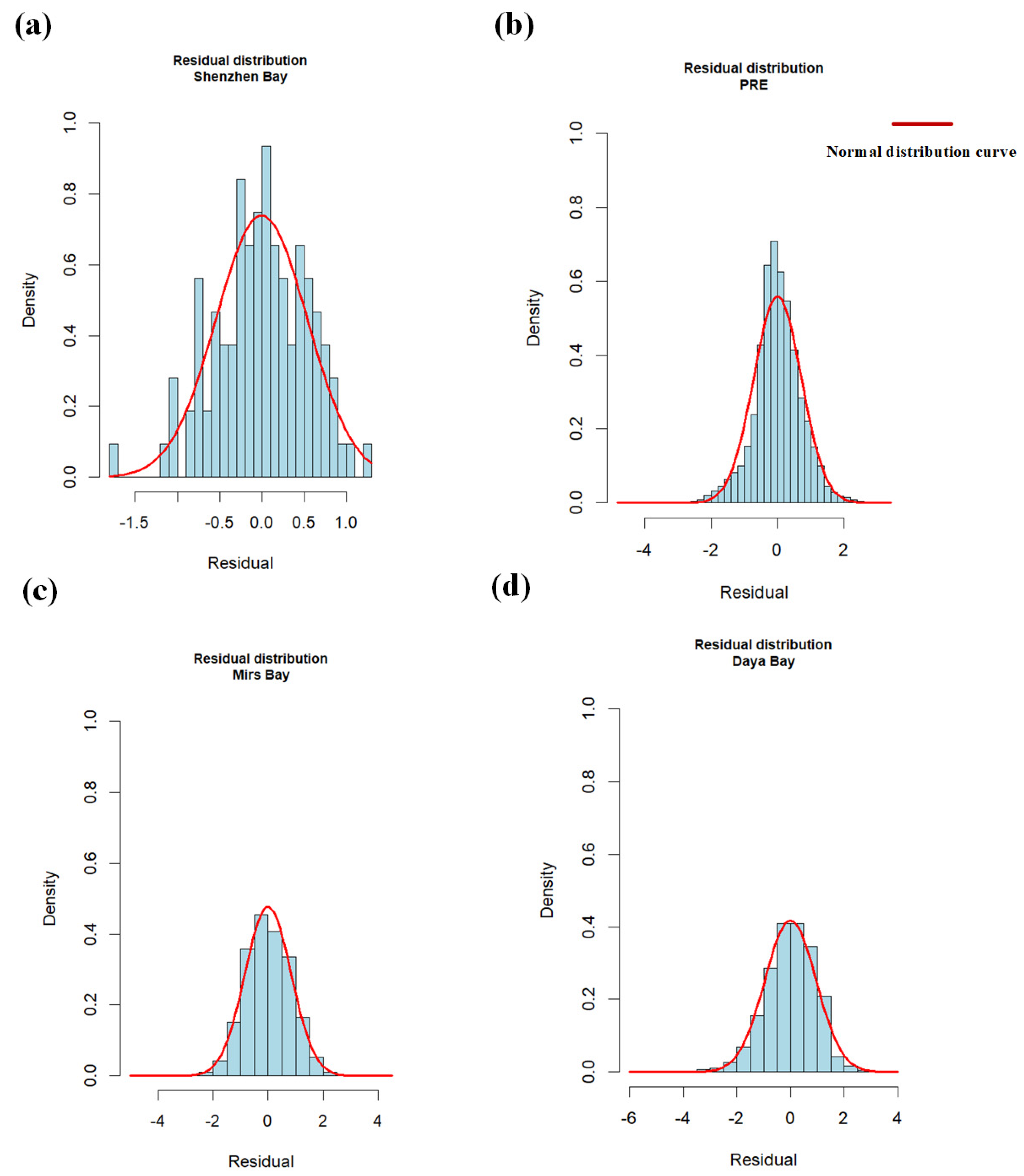

3.2.3. Stepwise Regression

4. Discussion

4.1. Mechanisms Influencing Chlorophyll-a Dynamics

4.2. Spatiotemporal Variations in Chl-a in Shenzhen Coastal Waters

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ma, C.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, G. Decoding the drivers of variability in chlorophyll-a concentrations in the Pearl River Estuary: Intra-annual and inter-annual analyses of environmental influences. Environ. Res. 2025, 268, 120783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Zhang, Y.; Han, T.; Zhang, M.; Cao, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Chen, X. Satellite mapping reveals phytoplankton biomass’s spatio-temporal dynamics and responses to environmental factors in a eutrophic inland lake. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, V.; Chávez-Casillas, J.; Inomura, K.; Mouw, C.B. Patterns in the temporal complexity of global chlorophyll concentration. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amorim, C.A.; Moura, A.D.N. Ecological impacts of freshwater algal blooms on water quality, plankton biodiversity, structure, and ecosystem functioning. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 758, 143605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mungenge, C.P.; Wasserman, R.J.; Dondofema, F.; Keates, C.; Masina, F.M.; Dalu, T. Assessing chlorophyll–a and water quality dynamics in arid–zone temporary pan systems along a disturbance gradient. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 873, 162272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sha, J.; Wang, Z.-L. Chlorophyll-A Prediction of Lakes with Different Water Quality Patterns in China Based on Hybrid Neural Networks. Water 2017, 9, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, J.; Liu, P.; Hu, X.; Zhu, S. Harmful Algal Blooms in Eutrophic Marine Environments: Causes, Monitoring, and Treatment. Water 2024, 16, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imai, I.; Inaba, N.; Yamamoto, K. Harmful algal blooms and environmentally friendly control strategies in Japan. Fish Sci. 2021, 87, 437–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiagarajan, C.; Devarajan, Y. The urgent challenge of ocean pollution: Impacts on marine biodiversity and human health. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 103995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, F.; Leng, K.; Zhou, Q.; Bi, Y.; Heng, Q. Analysis on the occurrences and evolution mechanism of HABs in Dapeng bay, Shenzhen in the last 40 years. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2021, 40, 263–271. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; Ma, F.; Zhai, X.; Yang, W.; Ye, P.; Liu, Y. Analysis on the key factors for the population evolution and early warning of harmful algal blooms based on an algal bloom in Shenzhen bay, the South China Sea. Ecol. Sci. 2022, 41, 82–89. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, K.; Sun, X. The spatial and temporal distribution of chlorophyll a and the influencing factors in Shenzhen Bay with frequent occurrence of red tide. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2009, 18, 1638. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, R.; Zhou, K.; Pang, N.; Heng, Q.; Zhuang, X.; Zhou, Q. The spatial and temporal distribution characteristics of Chlorophyll-a in the coastal waters of Mirs bay. Mar. Environ. Sci. 2017, 36, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gan, J. Controls of seasonal variability of phytoplankton blooms in the Pearl River Estuary. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2015, 117, 86–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, L.; Luo, X.; Hu, S.; Liu, F.; Cai, H.; Ren, L.; Ou, S.; Zeng, D.; Yang, Q. Impact of anthropogenic forcing on the environmental controls of phytoplankton dynamics between 1974 and 2017 in the Pearl River estuary, China. Ecol. Indic. 2020, 116, 106484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Yang, C.; Tang, S.; Chen, C. The phytoplankton variability in the Pearl River estuary based on VIIRS imagery. Cont. Shelf Res. 2020, 207, 104228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, D.; Li, J.; Xie, L.; Ye, X.; Zhou, D. Analysis of temporal characteristics of chlorophyll a in Lingding Bay during summer. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2022, 41, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Huang, L.; Tan, Y.; Ke, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhao, C.; Wang, J. Seasonal variations of chlorophyll a and primary production and their influencing factors in the Pearl River Estuary. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2017, 36, 81–91. [Google Scholar]

- Cereja, R.; Chainho, P.; Brotas, V.; Cruz, J.P.C.; Sent, G.; Rodrigues, M.; Carvalho, F.; Cabral, S.; Brito, A.C. Spatial Variability of Physicochemical Parameters and Phytoplankton at the Tagus Estuary (Portugal). Sustainability 2022, 14, 13324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, N.; Mao, X.-Z. Why do red tides occur frequently in some oligotrophic waters? Analysis of red tide evolution history in Mirs Bay, China and its implications. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 157112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Zhao, L. Coastal Water Clarity in Shenzhen: Assessment of Observations from Sentinel-2. Water 2023, 15, 4102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Xiu, B.; Cui, D.; Lu, D.; Yang, B.; Liang, S.; Zhou, J.; Huang, H.; Peng, S. Composition and distribution of nutrients and environmental capacity in Dapeng Bay, northern South China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 206, 116689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greater Bay Area. Overview. 2024. Available online: https://www.bayarea.gov.hk/sc/about/overview.html (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Liu, Y.; Feng, J.; Cheng, Q.; Tsou, J.Y.; Huang, B.; Ji, C.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Investigating spatiotemporal coastline changes and impacts on coastal zone management: A case study in Pearl River Estuary and Hong Kong’s coast. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2024, 257, 107354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, R.; Zhou, K.; Leng, K.; Guo, X.; Wu, J.; Zhong, W. The station design and data application of buoy monitoring Network in Shenzhen sea area. Ocean Dev. Manag. 2018, 35, 49–53. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 42074-2022; Climate and Climate Change. Division of Climatic Seasons. China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Lin, W.; Sun, X.; Ren, G.; Zhang, J. A review of seasonal division and change research. Prog. Geogr. 2024, 43, 826–840. [Google Scholar]

- Klein Tank, A.M.G.; Können, G.P. Trends in Indices of Daily Temperature and Precipitation Extremes in Europe 1946–1999. J. Clim. 2003, 16, 3665–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaagus, J.; Ahas, R. Space-time variations of climatic seasons and their correlation with the phenological development of nature in Estonia. Clim. Res. 2000, 15, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateorological Bureau of Shenzhen Municipality. Climate Profile and Seasonal Features of Shenzhen. 2024. Available online: https://weather.sz.gov.cn/qixiangfuwu/qihoufuwu/qihouguanceyupinggu/qihougaikuang/ (accessed on 12 August 2025).

- Bates, D.; Machler, M.; Bolker, B.; Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal-Rusiel, J.L.; Greve, D.N.; Reuter, M.; Fischl, B.; Sabuncu, M.R. Statistical analysis of longitudinal neuroimage data with Linear Mixed Effects models. NeuroImage 2013, 66, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, N.; William, W.; Michael, H.K. Stepwise Selection. In Applied Linear Regression Models; Irwin Professional Publishing: Burr Ridge, IL, USA, 1983; pp. 430–434. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, J. Precision Analysis and Parameter Inversion in the Stepwise Deployment of a Mixed Constellation. Open J. Stat. 2013, 3, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Han, Y.; Yi, L. Remote sensing inversion for net primary productivity and its spatial-temporal variability in Shenzhen coastal waters. J. Appl. Oceanogr. 2017, 36, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, K.; Rose, L.; Rohith, B.; Baliarsingh, S.K.; Samanta, A. Environmental controls on chlorophyll-a and dissolved oxygen variability in contrasting Basins of the Northern Indian ocean. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 210, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.; Liu, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, H.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Z. Assessing the distribution of nocturnal chlorophyll-a in the Northwest Pacific Ocean using ocean color and fishery echosounder acoustic data. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Christakos, G.; Cazelles, B.; Wu, J.; Leng, J. Spatiotemporal variation of the association between sea surface temperature and chlorophyll in global ocean during 2002–2019 based on a novel WCA-BME approach. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2021, 105, 102620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.C.; Jiménez, J.A.; Pereira, L.C.C. Natural and human controls of water quality of an Amazon estuary (Caeté-PA, Brazil). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 124, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkoni, A.; Sidorenko, V.; de Amorim, F.L.L.; Sarker, S.; Spence-Jones, H.C.; Rick, J.J.; van Beusekom, J.; Wiltshire, K.H. Long-Term Effects of Nutrient Shifts and Warming on Chlorophyll-a in a Temperate Coastal Environment. Estuaries Coasts 2025, 49, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Anselmo, T.P.; Barbosa, A.B.; Sommer, U.; Galvão, H.M. Light as a driver of phytoplankton growth and production in the freshwater tidal zone of a turbid estuary. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2011, 91, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Dai, M.; Zheng, N.; Wang, D.; Li, Q.; Zhai, W.; Meng, F.; Gan, J. Dynamics of the carbonate system in a large continental shelf system under the influence of both a river plume and coastal upwelling. J. Geophys. Res. 2011, 116, G02010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, K.M.A.; Jiang, W.; Liu, G.; Ahmed, M.K.; Akhter, S. Dominant physical-biogeochemical drivers for the seasonal variations in the surface chlorophyll-a and subsurface chlorophyll-a maximum in the Bay of Bengal. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 48, 102022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahwell, P.J.; Bejar, D.; Kim, D.; Solo-Gabriele, H.M. Non-traditional abiotic drivers explain variability of chlorophyll-a in a shallow estuarine embayment. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.; Caballero, I.; de la Calle, I.; Laiz, I. Chlorophyll-a and suspended matter variability in a data-scarce coastal-estuarine ecosystem. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2024, 309, 108973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, I.; De, A.; Nandi, S.; Thakur, S.; Raman, M.; Jose, F.; De, T.K. Estimation of Chlorophyll-a, TSM and salinity in mangrove dominated tropical estuarine areas of Hooghly River, North East Coast of Bay of Bengal, India using sentinel-3 data. Acta Geophys. 2024, 72, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Chakraborty, A. Simulating the Effects of Tidal Dynamics on the Biogeochemistry of the Hooghly Estuary. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2015, 8, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhao, H. Spatiotemporal distribution of chlorophyll-a concentration in the south China sea and its possible environmental regulation mechanisms. Mar. Environ. Res. 2025, 204, 106902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, L.; van Gelder, P.; Luo, X.; Cai, H.; Zhang, T.; Yang, Q. Implications of Nutrient Enrichment and Related Environmental Impacts in the Pearl River Estuary, China: Characterizing the Seasonal Influence of Riverine Input. Water 2020, 12, 3245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, R.; Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Bandara, G.; Atapaththu, K.; Wang, Y. Long-term alterations of nutrient dynamics and phytoplankton communities in Daya Bay, South China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 208, 116955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Wang, D.; Gong, F.; Bai, Y.; He, X. Changes in Nutrient Concentrations in Shenzhen Bay Detected Using Landsat Imagery between 1988 and 2020. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenzhen Municipal Planning and Natural Resources Bureau. Shenzhen Municipal Marine Environmental Quality Bulletin. 2019. Available online: http://meeb.sz.gov.cn/xxgk/tjsj/ndhjzkgb/content/post_7259599.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Huang, Y.; Cen, J.; Liang, Q.; Lu, S.; Wang, J. Study on the community structure of eukaryotic phytoplankton in the Shenzhen Bay based on high-throughput sequencing technology. J. Trop. Oceanogr. 2024, 43, 21–23. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Zhou, K.; Sun, X.; Xiao, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y. Seasonal changes of the phytoplankton in Shenzhen Bay. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2010, 10, 2445–2451. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, R.; Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Wai, T.; Shen, P.; Lam, P.K.S. Long-term variations of phytoplankton community in relations to environmental factors in Deep Bay, China, from 1994 to 2016. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 153, 111010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, T.; Chen, C.; Xie, L. Ecological Characteristics of Plankton in Shenzhen Bay. Meteorol. Environ. Res. 2019, 10, 43–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Swart, H. Impact of river discharge on phytoplankton bloom dynamics in eutrophic estuaries: A model study. J. Mar. Syst. 2015, 152, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H.; Tian, F.; Li, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Cai, W. Community structure of phytoplankton and its relationship to environmental factors in Shenzhen Bay. Ecol. Sci. 2021, 401, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, K.; Zhang, J.; Qian, P.; Jian, W.; Huang, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, M.C.S. Effect of wind events on phytoplankton blooms in the Pearl River estuary during summer. Cont. Shelf Res. 2004, 24, 1909–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Wu, J. Sediment trapping by haloclines of a river plume in the Pearl River Estuary. Cont. Shelf Res. 2014, 82, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Hu, S.; Chen, S.; Zeng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Liu, S. Vertical distribution of suspended particulate matter and its response to river discharge and seawater intrusion: A case study in the Pearl River Estuary during the 2020 dry season. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 2296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, S.; Cai, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. Effects of river input flux on spatiotemporal patterns of total nitrogen and phosphorus in the Pearl River Estuary, China. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 10, 1129712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Luo, W.; Dong, X.; Lei, S.; Mu, M.; Zeng, S. Landsat observations of total suspended solids concentrations in the Pearl River Estuary, China, over the past 36 years. Environ. Res. 2024, 249, 118461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.J.; Yin, K.; Lee, J.H.W.; Gan, J.; Liu, H. Physical-biological coupling in the Pearl River Estuary. Cont. Shelf Res. 2008, 28, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, J.E.; Palmer, M.R.; Poulton, A.J.; Hickman, A.E.; Sharples, J. Control of a phytoplankton bloom by wind-driven vertical mixing and light availability. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2021, 66, 1926–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Sun, F.; Cheng, H.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Wu, J. Monsoon-driven Dynamics of water quality by multivariate statistical methods in Daya Bay, South China Sea. Oceanol. Hydrobiol. Stud. 2012, 41, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenckman, C.M.; Parameswarappa Jayalakshmamma, M.; Pennock, W.H.; Ashraf, F.; Borgaonkar, A.D. A Review of Harmful Algal Blooms: Causes, Effects, Monitoring, and Prevention Methods. Water 2025, 17, 1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wang, X.; Xu, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhang, J. Distributions Characteristics of nutrients in sea water and its ecological environment effects in Daya Bay. Environ. Monit. China 2023, 39, 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhang, F. Seasonal Thermocline in the Daya Bay and its Influence on the Environmental Factors of Sea water. Mar. Sci. Bull. 2006, 25, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Das, B.K.; Sarkar, D.J.; Gogoi, P.; Nandy, S.K.; Kunui, A.; Bhor, M.; Sahoo, A.K. Variation in thermal trait and plankton assemblage pattern induced by coal power plant discharge in river Ganga. Aquat. Ecol. 2024, 58, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Ottmann, D.; Cao, P.; Yang, J.; Yu, J.; Lv, Z. Seasonal variability of phytoplankton community response to thermal discharge from nuclear power plant in temperate coastal area. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Li, B.; Sun, X. Effects of a coastal power plant thermal discharge on phytoplankton community structure in Zhanjiang Bay, China. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2014, 81, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhou, Q.; Xiang, P.; Huo, Y.; Lin, M. Impacts of Thermal Discharge on Phytoplankton in Daya Bay. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 83, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poornima, E.; Rajadurai, M.; Rao, V.; Narasimhan, S.; Venugopalan, V. Use of coastal waters as condenser coolant in electric power plants: Impact on phytoplankton and primary productivity. J. Therm. Biol. 2006, 31, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.; Yang, H.; Lin, H. Effects of a thermal discharge from a nuclear power plant on phytoplankton and periphyton in subtropical coastal waters. J. Sea Res. 2009, 61, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cao, H.; Liu, M.; Qi, F.; Zhang, S.; Xu, J. The influence of thermal discharge from power plants on the biogeochemical environment of Daya Bay during high primary productivity seasons. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2025, 211, 117408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Xu, Q.; Chen, Y.; Wang, B. Monitoring of Fine-Scale Warm Drain-Off Water from Nuclear Power Stations in the Daya Bay Based on Landsat 8 Data. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, B.; Lu, L.; Cao, Q.; Zhou, W.; Li, S.; Wen, D.; Hong, M. Three-dimensional numerical study of cooling water discharge of Daya Bay Nuclear Power Plant in southern coast of China during summer. Front. Mar. Sci. 2023, 9, 1012260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wang, Y. Modeling the ecosystem response of the semi-closed Daya Bay to the thermal discharge from two nearby nuclear power plants. Ecotoxicology 2020, 29, 736–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 3097-1997; Chinese Sea Water Quality Standard. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1998. Available online: http://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/fgbz/bz/bzwb/shjbh/shjzlbz/199807/t19980701_66499.shtml (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Lo, H.W.; Yu, X.; Chen, H.; Chu, W.C.; Chung, N.M.; Lau, S.W.; Li, J.; Liang, S.; Liao, K.; Thomas, H.C.J.; et al. Tidal currents and atmospheric inorganic nitrogen contribute to diurnal variation of dissolved nutrients and chlorophyll a concentrations in Mirs Bay, Hong Kong. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2025, 81, 103941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhou, F.; Wang, Q.; Xu, S.; Chen, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, Y. Colony sizes, cell abundances, carbon contents, and intra-colony nutrient concentrations of Phaeocystis globosa from Mirs Bay, China. J. Sea Res. 2023, 192, 102356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Cheng, W.; Chen, Y.; Yu, L.; Gong, W. Controls on the interannual variability of hypoxia in a subtropical embayment and its adjacent waters in the Guangdong coastal upwelling system, northern South China Sea. Ocean Dyn. 2018, 68, 923–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.E.; Giddings, S.N.; Pawlak, G.; Crooks, J.A. Hydrodynamic Variability of an Intermittently Closed Estuary over Interannual, Seasonal, Fortnightly, and Tidal Timescales. Estuaries Coasts 2023, 46, 84–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K. Overview of harmful algal blooms (red tides) in Hong Kong during 1975–2021. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2022, 40, 2094–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerhard, M.; Schlenker, A.; Hillebrand, H.; Striebel, M. Environmental stoichiometry mediates phytoplankton diversity effects on communities’ resource use efficiency and biomass. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 430–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yin, J.; Dong, J.; Jiang, Z.; Sun, F. Scenarios of nutrient alterations and responses of phytoplankton in a changing Daya Bay, South China Sea. J. Mar. Syst. 2017, 165, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhao, H. The satellite remotely-sensed analysis of temporal and spatial variation of surface Chlorophyll in the Daya Bay. J. Guangdong Ocean Univ. 2017, 37, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Qian, H.; Li, J. Preliminary studies on the relationships between Chlorophyll a and environmental factors in Dapeng Bay. Oceanol. Limnol. Sin. 1994, 25, 197–205. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Cai, W. Distribution of Chlorophyll-a and its affecting factors in the waters of Dapeng Bay. Mar. Sci. Bull. 1997, 15, 32–38. [Google Scholar]

| Date Type | Monitoring Parameters | Methods | Monitoring Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water quality parameters | Chl-a | Fluorescence method | Every 30 min |

| Water temperature | Thermal sensor method | ||

| Salinity | Conductometric analysis | ||

| DO | Fluorescence method | ||

| pH | Glass electrode method | ||

| Nutrients | Spectrophotometry | Every 4 h | |

| Meteorological parameters | Air temperature | Thermal sensor method | Every 15 min |

| Wind speed | Ultrasonic anemometer | ||

| Precipitation | Capacitive sensor method |

| Sea Area | Range/(μg·L−1) | Average/(μg·L−1) | Seasonal Average/(μg·L−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |||

| Pearl River Estuary | 0. 1~170.5 | 4.2 ± 5.8 | 3.4 ± 1.6 | 5.1 ± 6.4 | 3.6 ± 3.0 | 6.0 ± 3.4 |

| Shenzhen Bay | 0.1~101.6 | 5.2 ± 9.2 | 4.5 ± 6.9 | 6.3 ± 10.1 | 4.2 ± 8.9 | 4.7 ± 8.1 |

| Mirs Bay | 0.1~88.6 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 1.6 ± 1.4 | 2.1 ± 2.7 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 2.2 ± 1.7 |

| Daya Bay | 0.1~186.5 | 4.4 ± 5.7 | 3.0 ± 3.4 | 4.7 ± 7.0 | 5.7 ± 4.8 | 4.1 ± 2.9 |

| Entire area | 0.1~186.5 | 3.6 ± 5.5 | 2.6 ± 3.4 | 3.9 ± 6.5 | 3.7 ± 4.5 | 3.6 ± 3.6 |

| Fixed Effect | Random Effect and Fitting Degree | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | VIF | Estimate | Std. Error | p-Value | Intercept | Conditional R2 | Marginal R2 | ICC | |

| Model I | Intercept | - | −1.487 | 0.579 | 0.010 | 0.255 | 0.46 | 0.156 | 0.36 |

| water_tem | 3.825 | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |||||

| salinity | 1.512 | −0.039 | 0.003 | 0.000 | |||||

| pH | 2.633 | 0.102 | 0.084 | 0.226 | |||||

| DO | 2.721 | 0.259 | 0.014 | 0.000 | |||||

| windspeed | 1.053 | 0.039 | 0.008 | 0.000 | |||||

| Model II | Intercept | - | 3.350 | 0.782 | 0.000 | 0.177 | 0.44 | 0.293 | 0.22 |

| water_tem | 1.905 | 0.023 | 0.004 | 0.000 | |||||

| salinity | 1.816 | −0.083 | 0.005 | 0.000 | |||||

| PO4 | 1.527 | −6.802 | 0.671 | 0.000 | |||||

| DIN | 1.497 | 0.295 | 0.079 | 0.000 | |||||

| pH | 2.136 | −0.384 | 0.097 | 0.000 | |||||

| DO | 2.323 | 0.314 | 0.013 | 0.000 | |||||

| windspeed | 1.011 | 0.019 | 0.007 | 0.007 | |||||

| PRE | Shenzhen Bay | Mirs Bay | Daya Bay | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient | SD Coefficient | Coefficient | SD Coefficient | Coefficient | SD Coefficient | Coefficient | SD Coefficient | |

| Temperature | −0.018 | −0.093 | 0.194 | 0.304 | - | - | −0.038 | −0.174 |

| Salinity | −0.550 | −0.553 | −0.189 | −0.525 | −0.196 | −0.298 | −1.37 | −0.204 |

| pH | 0.776 | 0.229 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| DO | 0.089 | 0.128 | 0.380 | 0.781 | 0.196 | 0.196 | 0.258 | 0.232 |

| DIN | - | - | 1.237 | 0.204 | 0.925 | 0.051 | - | - |

| Phosphate | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Wind speed | 0.021 | 0.053 | 0.108 | 0.127 | - | - | −0.005 | −0.010 |

| Constant | −3.676 | - | 7.047 | - | 5.087 | - | 4.243 | - |

| R2 | 0.285 | 0.824 | 0.307 | 0.326 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.; Wu, S.; Xu, L.; Wang, K.; Li, Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Chlorophyll-a in Shenzhen’s Nearshore Waters: Insights from High-Frequency Buoy Observations. Sustainability 2026, 18, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010150

Chen Y, Wu S, Xu L, Wang K, Li Y. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Chlorophyll-a in Shenzhen’s Nearshore Waters: Insights from High-Frequency Buoy Observations. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010150

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yao, Shuilan Wu, Lijun Xu, Kaimin Wang, and Yu Li. 2026. "Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Chlorophyll-a in Shenzhen’s Nearshore Waters: Insights from High-Frequency Buoy Observations" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010150

APA StyleChen, Y., Wu, S., Xu, L., Wang, K., & Li, Y. (2026). Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Chlorophyll-a in Shenzhen’s Nearshore Waters: Insights from High-Frequency Buoy Observations. Sustainability, 18(1), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010150