The Role of Online Banking Service Clues in Enhancing Individual and Corporate Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience as a Corporate Social Responsibility

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- To investigate how digital service design (functional, mechanic, humanic clues) influences customer satisfaction across diverse banking sectors, with a focus on post-crisis economies.

- (2)

- To explore the mediating role of customer experience in technology-driven service interactions, emphasizing corporate social responsibility (CSR) as a driver of sustainable financial ecosystems.

- (3)

- To analyze demographic and contextual moderators (e.g., trust post-crisis, cybersecurity concerns) to develop inclusive strategies for digital banking adoption aligned with global sustainability goals.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Customer Experience

2.2. Service Clues

2.3. Customer Satisfaction

2.4. Expectancy Disconfirmation Theory

2.5. Hypothesis Development and Research Framework

2.5.1. Online Service Clues and Customer Satisfaction

2.5.2. Online Service Clues and Customer Experience

2.5.3. Customer Experience and Customer Satisfaction

2.5.4. Mediating Effect of Customer Experience

2.5.5. Demographics, Service Clues, and Customer Satisfaction

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Population and Sample

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Questionnaire Construct

3.3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.3.2. Measurement

3.4. PLS-SEM Methodology and Software

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model Results

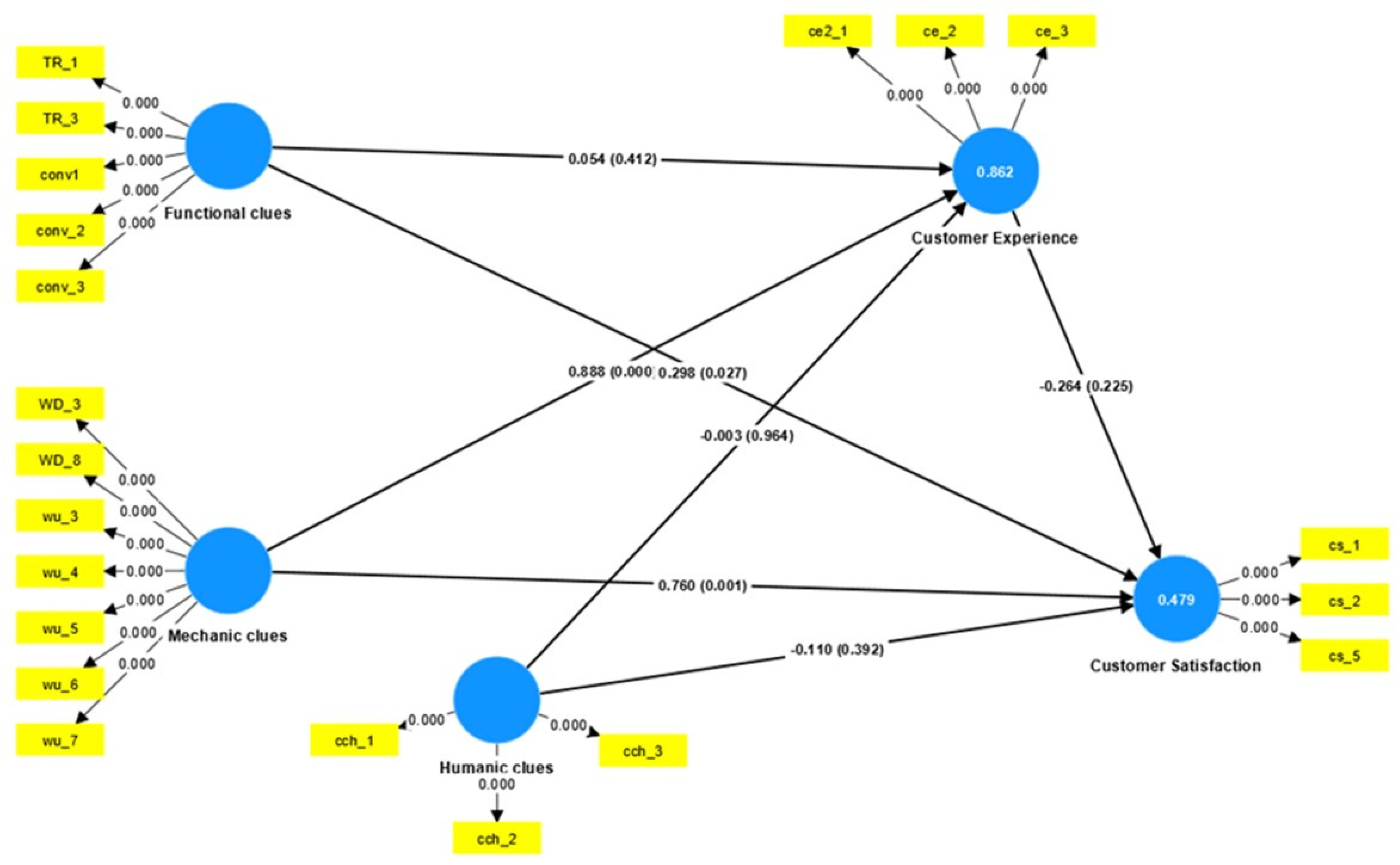

4.2. Structural Model Results

4.3. Test of the Mediating Effects

4.4. Test of the Moderating Effects

4.5. Summary of Individual and Corporate Customer Satisfaction

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings of the Study

- Age: Younger, tech-oriented users (<40) exhibit stronger satisfaction with mechanic clues, while older demographics (40+) prioritize functional assurances [103].

- Education and income: Highly educated and high-income users demand advanced functionalities (e.g., AI-driven tax dashboards), while less educated and low-income groups prioritize accessibility (e.g., voice-command interfaces) [124].

- Occupation: Business owners and self-employed individuals accustomed to risk-taking report higher satisfaction with online banking than public sector employees [125].

5.2. Managerial Implications

5.3. Theoretical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research Suggestions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zeebaree, M.; Ismael, G.Y.; Nakshabandi, O.A.; Saleh, S.S.; Aqel, M. Impact of innovation technology in enhancing organizational management. Impact Innov. Technol. Enhancing Organ. Manag. 2020, 38, 3970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banu, A.M.; Mohamed, N.S.; Parayitam, S. Online banking and customer satisfaction: Evidence from India. Asia-Pac. J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2019, 15, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleimi, M.; Musleh, M. E-Banking services quality and customer loyalty: The moderating effect of customer service satisfaction: Empirical evidence from the UAE banking sector. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 3663–3674. [Google Scholar]

- Almaiah, M.A.; Al-Rahmi, A.M.; Alturise, F.; Alrawad, M.; Alkhalaf, S.; Lutfi, A.; Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Awad, A.B. Factors influencing the adoption of internet banking: An integration of ISSM and UTAUT with price value and perceived risk. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 919198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiryawan, D.; Suhartono, J.; Hiererra, S.E.; Gui, A. Factors affecting digital banking customer satisfaction in Indonesia using D&M model. In Proceedings of the 2022 10th International Conference on Cyber and IT Service Management (CITSM), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 20–21 September 2022; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kesa, D.D. Consumer Perception Toward Online Banking Services to Build Brand Loyalty: Evidence from Indonesia. KnE Soc. Sci. 2018, 3, 1183–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Suchánek, P.; Králová, M. Customer satisfaction, loyalty, knowledge and competitiveness in the food industry. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraz. 2019, 32, 1237–1255. [Google Scholar]

- Manyanga, W.; Makanyeza, C.; Muranda, Z. The effect of customer experience, customer satisfaction and word of mouth intention on customer loyalty: The moderating role of consumer demographics. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2082015. [Google Scholar]

- Haeckel, S.H.; Carbone, L.P.; Berry, L.L. How to lead the customer experience. Mark. Manag. 2003, 12, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.D. Technology acceptance model: TAM. In Information Seeking Behavior and Technology Adoption; Al-Suqri, M.N., Al-Aufi, A.S., Eds.; IGI Global: New York, NY, USA, 1989; Volume 219, pp. 205–219. [Google Scholar]

- Prentice-Dunn, S.; Rogers, R.W. Protection motivation theory and preventive health: Beyond the health belief model. Health Educ. Res. 1986, 3, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rita, P.; Oliveira, T.; Farisa, A. The impact of e-service quality and customer satisfaction on customer behavior in online shopping. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02690. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, R.R.; Romeika, G.; Kauliene, R.; Streimikis, J.; Dapkus, R. ES-QUAL model and customer satisfaction in online banking: Evidence from multivariate analysis techniques. Oeconomia Copernic. 2020, 11, 59–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassany, H.; Faisal, F. Factors influencing the internet banking adoption decision in North Cyprus: An evidence from the partial least square approach of the structural equation modeling. Financ. Innov. 2018, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozatac, N.; Saner, T.; Sen, Z.S. Customer satisfaction in the banking sector: The case of North Cyprus. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2016, 39, 870–878. [Google Scholar]

- Altay, O.; Olkan, L.A. 2009–2013 Döneminde KKTC’deki Ticari Bankaların Performans Analizi. EUL J. Soc. Sci. 2015, 6, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Kutlay, K. Kuzey Kıbrıs’ ta Banka Karlığını Etkileyen Faktörler: Ampirik bir Çalışma. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Scientific Cooperation for the Future in the Economics and Administrative Sciences, Thessaloniki, Greece, 6–8 September 2017; Volume 231. [Google Scholar]

- Yeşilada, T.; Yalyalı, P. KKTC’de Bankacılık Sektöründe Şube ve Personel Sayısındaki Gelişmeler ile Veri Zarflama Analizi Yöntemi Kullanılarak Yapılan Etkinlik Analizi Çalışması, Lefke Avrupa Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. EUL J. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 27–49. [Google Scholar]

- Şafakli, O.V. Perceptions of academicians towards the reasons of using internet banking: Case of Northern Cyprus. Int. J. Acad. Res. Account. Financ. Manag. Sci. 2017, 7, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serener, B. Internet bankıng adoptıon ın Northern Cyprus: Adopters versus non-adopters. Ponte Int. J. Sci. Res. 2017, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serener, B. Barriers to the use of internet banking among Nigerian and Zimbabwean students in Northern Cyprus. J. Manag. Econ. Res. 2018, 16, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Jenkins, H.; Hesami, S.; Yesiltepe, F. Factors Affecting Internet Banking Adoption: An Application of Adaptive LASSO. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2022, 72, 6167–6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Akhtar, A.; Gupta, A. Customer experience in digital banking: A review and future research directions. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2022, 14, 311–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasan, P. Predicting customer experience and discretionary behaviors of bank customers in India. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 701–725. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone, L.P.; Haeckel, S.H. Engineering Customer Experiences. J. Mark. Manag. 1994, 3, 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Hussadintorn Na Ayutthaya, D.; Koomsap, P. Improving Experience Clues on a Journey for Better Customer Perceived Value. In Transdisciplinary Engineering for Complex Socio-Technical Systems; Hiekata, K., Moser, B., Inoue, M., Stouffs, R., Šćekić, S.I., Eds.; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemon, K.N.; Verhoef, P.C. Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. J. Mark. 2016, 80, 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Godovykh, M.; Tasci, A.D.A. Customer experience in tourism: A review of definitions, components, and measurements. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 35, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chepur, J.; Bellamkonda, R. Examining the conceptualizations of customer experience as a construct. Acad. Mark. Stud. J. 2019, 23, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen, K.; Lipkin, M. Ordinary customer experience: Conceptualization, characterization, and implications. Psycol. Market. 2023, 40, 1720–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Wang, S.; Li, F.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, W.; Gai, F.; Yu, B.; Feng, L.; Gao, Q.; Li, Y. Ubiquitous verification in centralized ledger database. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 38th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 9–12 May 2022; pp. 1808–1821. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, S.; Yu, B.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Yan, W. LedgerDB: A centralized ledger database for universal audit and verification. Procedia VLDB End. 2020, 13, 3138–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, R.; Yue, C.; Liu, Y.; Ooi, B.C.; Gao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H. VeDB: A software and hardware enabled trusted relational database. Procedia ACM Manag. Data 2023, 2, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinbarger, M.; Gilly, M.C. eTailQ: Dimensionalizing, measuring and predicting retail quality. J. Retail. 2003, 79, 183–198. [Google Scholar]

- Djulianto, M.V.; Wardhanie, A.P.; Candraningrat, C. The Role of Perceived Usability, Satisfaction, and Customer Trust in Design and Developing User Loyalty Edutech Website. Bus. Financ. J. 2022, 7, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- Kirakowski, J.; Cierlik, B. Measuring the usability of web sites. Proc. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 1998, 42, 424–428. [Google Scholar]

- Mazhar, M.; Hooi Ting, D.; Zaib Abbasi, A.; Nadeem, M.A.; Abbasi, H.A. Gauging Customers’ Negative Disconfirmation in Online Post-Purchase Behaviour: The Moderating Effect of Service Recovery. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2072186. [Google Scholar]

- Rais, N.M.; Musa, R.; Muda, M. Reconceptualisation of customer experience quality (CXQ) measurement scale. Procedia Econ. Fin. 2016, 37, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagr, P.; Rajesh, A.; Misra, R. A study on driving factors for enhancing financial performance and customer-centricity through digital banking. Int. J. Qual. Serv. Sci. 2024, 16, 218–250. [Google Scholar]

- Amenuvor, F.E.; Owusu-Antwi, K.; Basilisco, R.; Bae, S.C. Customer Experience and Behavioral Intentions: The Mediation Role of Customer Perceived Value. Int. J. Sci. Res. Manag. 2019, 7, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Gahler, M.; Klein, J.F.; Paul, M. Customer Experience: Conceptualization, Measurement, and Application in Omnichannel Environments. J. Serv. Res. 2023, 26, 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.R.; Wang, Y.H.; Hung, Y.M. Analyzing the factors influencing adoption intention of internet banking: Applying DEMATEL-ANP-SEM approach. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0227852. [Google Scholar]

- De Keyser, A.; Verleye, K.; Lemon, K.N.; Keiningham, T.L.; Klaus, P. Moving the Customer Experience Field Forward: Introducing the Touchpoints, Context, Qualities (TCQ) Nomenclature. J. Serv. Res. 2020, 23, 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flacandji, M.; Krey, N. Remembering shopping experiences: The shopping experience memory scale. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 107, 279–289. [Google Scholar]

- Arici, H.E.; Köseoglu, M.A.; Sökmen, A. The intellectual structure of customer experience research in service scholarship: A bibliometric analysis. Serv. Ind. J. 2022, 42, 514–550. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, H.J.; Jun, J.K. A study on the semantic network analysis of luxury hotel and business hotel through the big data. Culin. Sci. Hosp. Res. 2019, 25, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Almansour, B.; Elkrghli, S. Factors influencing customer satisfaction on e-banking services: A study of Libyan banks. Int. J. Tech. Innov. Manag. 2020, 3, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gronroos, C. A service quality model and its marketing implications. Eur. J. Mark. 1984, 18, 36–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nkwede, M.F.C.; Ogba, I.E.; Nkwede, F.E. Determinants of customer satisfaction in a high-contact service environment: A study of selected hotels in Abakaliki metropolis, Nigeria. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 12, 183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Yue, C.; Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Ooi, B.C.; Chen, J. SecuDB: An In-enclave Privacy-Preserving and Tamper-resistant Relational Database. Procedia VLDB Endow. 2024, 17, 3906–3919. [Google Scholar]

- Taherdoost, H. A review of technology acceptance and adoption models and theories. Procedia Manuf. 2018, 22, 960–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathar, M.B.A.; Rajagopalan, M.; Naina, S.M.; Parayitam, S. A moderated-mediation model of perceived enjoyment, security and trust on customer satisfaction: Evidence from banking industry in India. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2020, 17, 656–679. [Google Scholar]

- Bleier, A.; Harmeling, C.M.; Palmatier, R.W. Creating effective online customer experiences. J. Mark. 2020, 83, 98–119. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y. Elucidating determinants of customer satisfaction with live-stream shopping: An extension of the information systems success model. Telemat. Inform. 2021, 65, 101707. [Google Scholar]

- Cele, N.N.; Kwenda, S. Do cybersecurity threats and risks have an impact on the adoption of digital banking? A systematic literature review. J. Financ. Crime 2020, 32, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, I.M.; Amin, H. Influence of innovation diffusion factors on non-users’ adoption of digital banking services in the banking 4.0 era. Inf. Discov. Deliv. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Yoo, J.W.; Cho, Y.; Park, H. Understanding switching intentions between traditional banks and Internet-only banks among Generation X and Generation Z. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 42, 1114–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.A.; Umer, A.; Qureshi, M.A.; Dahri, A.S. Internet banking service quality, e-customer satisfaction and loyalty: The modified e-SERVQUAL model. TQM J. 2020, 32, 1443–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zia, A. Discovering the linear relationship of service quality, satisfaction, attitude and loyalty for banks in Albaha, Saudi Arabia. PSU Res. Rev. 2022, 6, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supriyanto, A.; Wiyono, B.B.; Burhanuddin, B.; Olan, F. Effects of service quality and customer satisfaction on loyalty of bank customers. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1937847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Duan, H.; Zhang, L.; Ergu, D.; Liu, F. The main influencing factors of customer satisfaction and loyalty in city express delivery. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1044032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awa, H.O.; Ikwor, N.K.; Ademe, D.G. Customer satisfaction with complaint responses under the moderation of involvement. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2021, 8, 1905217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, J.; Shamim, A.; Nawaz, M.; Faye, I.; Rehman, M. Co-creation or co-destruction: A perspective of online customer engagement valence. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 591753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, R.; Ahmed, S.; Rahman, M.; Al Asheq, A. Determinants of service quality and its effect on customer satisfaction and loyalty: An empirical study of private banking sector. TQM J. 2020, 33, 1163–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yüksel, A.; Yüksel, F. Consumer satisfaction theories: A critical review. In Tourist Satisfaction and Complaining Behavior: Measurement and Management Issues in the Tourism and Hospitality Industry; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 65–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rust, R.T.; Oliver, R.L. Service Quality: Insights and Managerial Implications from the Frontier; Service Quality: New Directions in Theory and Practice; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; Volume 7, pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, W.; Petrovsky, N.; Walker, R.M. The expectancy--disconfirmation model and citizen satisfaction with public services: A meta–analysis and an agenda for best practice. Public Adm. Rev. 2022, 82, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamani, E.D.; Pouloudi, N. Generative mechanisms of workarounds, discontinuance and reframing: A study of negative disconfirmation with consumerised IT. Inf. Syst. J. 2021, 31, 384–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreelakshmi, C.C.; Prathap, S.K. Continuance adoption of mobile-based payments in COVID-19 context: An integrated framework of health belief model and expectation confirmation model. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2020, 16, 351–369. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, D.K.; Sah, G.K. Online Banking Service Practices and Its Impact on E-Customer Satisfaction and E-Customer Loyalty in Developing Country of South Asia-Nepal. Sage Open 2023, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayinaddis, S.G.; Taye, B.A.; Yirsaw, B.G. Examining the effect of electronic banking service quality on customer satisfaction and loyalty: An implication for technological innovation. J. Innov. Entrep. 2023, 12, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, F.N.; Arshad, M.U.; Munir, M. Impact of e-service quality on e-loyalty of online banking customers in Pakistan during the Covid-19 pandemic: Mediating role of e-satisfaction. Future Bus. J. 2023, 9, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Anouze, A.L.M.; Alamro, A.S. Factors affecting intention to use e-banking in Jordan. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2020, 38, 86–112. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Han, J.J. The Effects of Service Clues on Likelihoods of Additional Purchase. J. Stud. Res. 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiber, N. Impact of online banking in customer’s behavior in San Pablo City, Laguna. J. Third World Econ. 2023, 1, 14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Berry, L.L.; Wall, E.A.; Carbone, L.P. Service clues and customer assessment of the service experience: Lessons from marketing. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2006, 20, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borishade, T.T. Customer Experience Management and Loyalty in Healthcare Sector: A Study of Selected Private Hospitals in Lagos State, Nigeria. Ph.D. Dissertation, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Lai, K.H.; Wu, J.; Duan, W. Listening to online reviews: A mixed-methods investigation of customer experience in the sharing economy. Decis. Support Syst. 2021, 149, 113609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prentice, C.; Nguyen, M. Engaging and retaining customers with AI and employee service. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 56, 102186. [Google Scholar]

- Zaid, S.; Patwayati, P. Impact of customer experience and customer engagement on satisfaction and loyalty: A case study in Indonesia. J. Asian Financ. Econ. Bus. 2021, 8, 983–992. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, M.T. The impact of customer experience on customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. Turk. J. Comput. Math. Educ. 2020, 12, 1027–1038. [Google Scholar]

- Tjahjaningsih, E.; Widyasari, S.; Maskur, A.; Kusuma, L. The Effect of Customer Experience and Service Quality on Satisfaction in Increasing Loyalty. In Icobame, 3rd ed.; Atlantis Press: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Lemon, K.N.; Parasuraman, A.; Roggeveen, A.; Tsiros, M.; Schlesinger, L.A. Customer experience creation: Determinants, dynamics and management strategies. J. Retail. 2020, 85, 31–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kamath, P.R.; Pai, Y.P.; Prabhu, N.K.P. Building customer loyalty in retail banking: A serial-mediation approach. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 38, 456–484. [Google Scholar]

- Kamboj, N.; Singh, G. Customer satisfaction with digital banking in India: Exploring the mediating role of demographic factors. Indian J. Comput. Sci. 2018, 3, 9–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, A.; Bhatt, S. Factors affecting customer adoption of mobile banking services. J. Internet Bank. Commer. 2020, 21, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Sambaombe, J.K.; Phiri, J. An analysis of the impact of online banking on customer satisfaction in commercial banks based on the TRA model (a case study of Stanbic bank Lusaka main branch). Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 10, 369–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.H.; Pang, Y.L. Demographics and customer satisfaction. EPRA Int. J. Environ. Econ. Commer. Edu. Manag. 2021, 8, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; Pearson: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rahi, S. Research design and methods: A systematic review of research paradigms, sampling issues and instruments development. J. Econ. Mark. Sci. 2017, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Turner, D.P. Sampling Methods in Research Design. Headache J. Head Face Pain 2020, 60, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bouafi, S. The Effects of Digital Banking on Customer Experience, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty in Morocco. Master’s Thesis, Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimağusa, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Altobishi, T.; Erboz, G.; Podruzsik, S.J.I. E-Banking effects on customer satisfaction: The survey on clients in Jordan Banking Sector. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2018, 10, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, C.; Guinalíu, M.; Gurrea, R. The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Inf. Manag. 2006, 43, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christine Roy, M.; Dewit, O.; Aubert, B.A. The impact of interface usability on trust in web retailers. Internet Res. 2001, 11, 388–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, H.; Dutta, K. Measurement and impact of customer experience in banking sector. Decision 2015, 42, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, R.; Rahman, Z.; Kumar, I. Evaluating a model for analyzing methods used for measuring customer experience. J. Database Mark. Cust. Strategy Manag. 2010, 17, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaus, P.P.; Maklan, S. Towards a better measure of customer experience. Int. J. Mark. Res. 2013, 55, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.J.; Wang, W.H.; Farquhar, J.D. The influence of customer perceptions on financial performance in financial services. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2009, 27, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbama, C.I.; Ezepue, P.; Alboul, L.; Beer, M. Digital banking, customer experience and financial performance. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2018, 12, 230–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th ed.; Allyn and Bacon: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McQuitty, S. Statistical power and structural equation models in business research. J. Bus. Res. 2004, 57, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, J.; Shevlin, M. Effects of sample size, model specification and factor loadings on the GFI in confirmatory factor analysis. Pers. Individ. Differ. 1998, 25, 85–90. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler, P.M.; Bonnet, D.C. Significance Tests and Goodness of Fit in the Analysis of Covariance Structures. Psychol. Bull. 1980, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria Versus New Alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Sinkovics, N.; Sinkovics, R.R. A perspective on using partial least squares structural equation modelling in data articles. Data Brief. 2023, 48, 109074. [Google Scholar]

- Marcoulides, K.M.; Raykov, T. Evaluation of Variance Inflation Factors in Regression Models Using Latent Variable Modeling Methods. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2019, 79, 874–882. [Google Scholar]

- Nunnally, J.C.; Bernstein, I. Psychometric Theory; MacGrow-Hill Higher: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, J.M.; Altman, D.G. Statistics notes: Cronbach’s alpha. BMJ 1997, 314, 572. [Google Scholar]

- Taber, K.S. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res. Sci. Educ. 2018, 48, 1273–1296. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Evaluation of reflective measurement models. In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Hair, J.F. Partial least squares structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 587–632. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, W.A.; Glowik, M.; Arslan, A. Knowledge sharing motives and value co-creation behavior of the consumers in physiotherapy services: A cross-cultural study. J. Knowl. Manag. 2021, 25, 1128–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Borishade, T.T.; Worlu, R.; Ogunnaike, O.O.; Aka, D.O.; Dirisu, J.I. Customer experience management: A study of mechanic versus humanic clues and student loyalty in Nigerian higher education institution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quach, S.; Barari, M.; Moudry, D.V.; Quach, K. Service integration in omnichannel retailing and its impact on customer experience. J. Retail. Cons. Serv. 2020, 65, 102267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franky, F.; Syah, T.Y.R. The Effect of Customer Experience, Customer Satisfaction, and Customer Loyalty on Brand Power and Willingness to Pay a Price Premium. Quant. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 4, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharto, S.; Hoti, A. Relationship Marketing, Customer Experience and Customer Satisfaction: Testing Their Theoretical and Empirical Underpinning. J. Manag. Bus. 2023, 14, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shandilya, G.; Dubey, A.; Srivastava, P. Analysing moderating effects of demographic variables on customer satisfaction: A study of quick service restaurant. Atna J. Tour. Stud. 2023, 18, 51–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. Cognitive load theory. In Psychology of Learning and Motivation; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; Volume 55, pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Teeroovengadum, V. Service quality dimensions as predictors of customer satisfaction and loyalty in the banking industry: Moderating effects of gender. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2022, 34, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Xie, Q. Something social, something entertaining? How digital content marketing augments consumer experience and brand loyalty. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 376–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, X.L.; Guo, J.N.; Wu, T.J.; Zhou, W.X.; Yeh, S.P. Does the effect of customer experience on customer satisfaction create a sustainable competitive advantage? A comparative study of different shopping situations. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubeyinje, G.T.; Omigie, S.O. The Influence of Service Quality Dimensions On Customer Satisfaction in The Nigerian Banking Industry. Oradea J. Bus. Econ. 2022, 7, 67–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J.S.; Stanovich, K.E. Dual-process theories of higher cognition: Advancing the debate. Pers. Psy. Sci. 2013, 8, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, R.W. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J. Psychol. 1975, 91, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamari, J.; Koivisto, J.; Sarsa, H. Does gamification work? A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In Proceedings of the 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 6–9 January 2014; pp. 3025–3034. [Google Scholar]

- Speier, C.; Venkatesh, V. The hidden minefields in the adoption of sales force automation technologies. J. Mark. 2002, 66, 98–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R.C.; Davis, J.H.; Schoorman, F.D. An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, R.N.; Grønhaug, K. Perceived risk: Further considerations for the marketing discipline. Eur. J. Mark. 1993, 27, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Description | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 250 | 62.50 |

| Male | 150 | 37.50 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 | |

| Age | 20 years and below | 2 | 0.50 |

| 21–30 years | 81 | 20.25 | |

| 31–40 years | 193 | 48.25 | |

| 41–50 years | 82 | 20.50 | |

| 51–60 years | 28 | 7.00 | |

| 61 years and above | 14 | 3.50 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 | |

| Type of customer | Individual bank customers | 200 | 50.00 |

| Corporate bank customers | 200 | 50.00 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 | |

| Academic qualification | Primary school | 3 | 0.75 |

| Secondary school | 6 | 1.50 | |

| High school | 54 | 13.5 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 175 | 43.75 | |

| Two-year associate degree | 27 | 6.75 | |

| Master’s degree and above | 135 | 33.75 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 | |

| Occupation | Private sector employee | 58 | 14.50 |

| Public sector employee | 17 | 4.25 | |

| Retired | 18 | 4.50 | |

| Self-employed | 47 | 11.75 | |

| Business owner | 200 | 50.00 | |

| Others | 60 | 15.00 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 | |

| Monthly income (TRY) | 15,750 and less | 52 | 13.00 |

| 15,750 to 20,000 | 85 | 21.25 | |

| 20,000 to 25,000 | 56 | 14.00 | |

| 25,000 to 30,000 | 80 | 20.00 | |

| 30,000 to 35,000 | 36 | 9.00 | |

| 35,000 to 40,000 | 24 | 6.00 | |

| 45,000 and more | 67 | 16.75 | |

| Total | 400 | 100 |

| Construct | Clue Type | Measurement Statements | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Quality | Functional clues | 1. Internet and mobile devices facilitate banking services. | [92] |

| 2. The Internet has improved the quality of banking services. | |||

| 3. It is easy to use the Internet for banking services. | |||

| 4. I am able to get on the website/mobile application quickly. | |||

| 5. It is easy for me to find what I need on my bank’s website/mobile application. | |||

| Trust | 1. I can trust my bank when using the Internet for any service. | [92] | |

| 2. My bank’s services have a good reputation. | |||

| 3. I feel very comfortable doing online banking with my bank. | |||

| 4. My bank quickly resolves the problems I encounter with my online operations. | |||

| Convenience | 1. Online banking services fit my needs and will. | [93] | |

| 2. Online banking services afford great facilities. | |||

| 3. You can carry out online banking services anywhere. | |||

| Website Design | Mechanic clues | 1. The online banking website provides in-depth information. | [34] |

| 2. The online banking website does not confuse me about what I want to do with the website pages. | |||

| 3. The online banking’s webpage does not freeze after I input information. | |||

| 4. The site map of the online banking website is clear, and the content and picture of the site are user-friendly. | |||

| 5. I can log in to the online banking website easily. | |||

| 6. The online banking’s website loads quickly. | |||

| 7. The online banking website’s information is always updated in time. | |||

| 8. The online banking website offers my preferred service. | |||

| 9. The transaction outcome is informed clearly. | |||

| 10. It is quick and easy to complete a transaction on the online banking website. | |||

| 11. The level of personalization on the online banking’s website is about right, not too much or too little. | |||

| 12. The online banking website does not waste my time. | |||

| Website Usability | 1. On this website, everything is easy to understand. | [36,94,95] | |

| 2. This website is simple to use, even when using it for the first time. | |||

| 3. It is easy to find the information I need from this website. | |||

| 4. The structure and contents of this website are easy to understand. | |||

| 5. It is easy to navigate within this website. | |||

| 6. The organization of the contents of this site makes it easy for me to know where I am when navigating it. | |||

| 7. When I am navigating this site, I feel that I am in control of what I can do. | |||

| Customer Complaint Handling | Humanic clues | 1. The online banking service is willing to respond to customer needs. | [34] |

| 2. When you have a problem, the online banking website shows a sincere interest in solving it. | |||

| 3. Inquiries are answered promptly through online customer service representatives. | |||

| 4. Customer service representatives are qualified and have a good service attitude. | |||

| Customer Satisfaction | 1. I am satisfied with the online banking service. | [92] | |

| 2. My bank’s online services meet my needs and expectations. | |||

| 3. I am satisfied with the electronic accessibility. | |||

| 4. I am satisfied with the staff in helping accessing online. | |||

| 5. I made a good decision when I choose my bank for online services. | |||

| Customer Experience | 1. My bank handles customer problems well. | [83,96,97,98,99,100] | |

| 2. My bank offers prompt customer service. | |||

| 3. My bank’s products are ease to use. | |||

| 4. My bank always meets my service needs and requirements. | |||

| 5. My bank provides me error free services. | |||

| 6. My overall experience with my bank is pleasing. |

| Fit Index | Acceptable Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| (χ2/df) | ≤2 | [102] |

| RMSEA (Root mean square error of approximation) | ≤0.08 | [103] |

| GFI (Goodness-of-fit statistic) | ≥0.9 | [104] |

| AGFI (Adjusted goodness-of-fit statistic) | ≥0.9 | [102] |

| NFI (Normed fit index) | ≥0.9 | [105] |

| CFI (Comparative fit index) | ≥0.9 | [106] |

| SRMR (Standardized root mean square residual) | ≤0.08 | [106] |

| Construct | Factor Loadings | Outer Weight (p-Values) | VIF | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Customer | Corporate Customer | Individual Customer | Corporate Customer | |||

| Trust (TR) | TR1 | 0.761 | 0.812 | 0.000 | 2.945 | - |

| TR2 | - | 0.798 | 0.000 | 2.820 | - | |

| TR3 | 0.733 | 0.800 | 0.000 | - | - | |

| Functional Quality (FQ) | FQ5 | - | 0.804 | 0.000 | - | 1.708 |

| Web Design (WD) | WD3 | 0.735 | 0.786 | 0.000 | - | 1.761 |

| WD4 | - | 0.793 | 0.000 | 1.748 | - | |

| WD5 | - | 0.764 | 0.000 | - | 1.940 | |

| WD6 | - | 0.805 | 0.000 | - | - | |

| WD8 | 0.729 | 0.719 | 0.000 | - | 2.006 | |

| Customer Complaint Handling (CCH) | CCH1 | 0.856 | 0.833 | 0.000 | - | 1.775 |

| CCH2 | 0.864 | 0.817 | 0.000 | 1.912 | 1.831 | |

| CCH3 | 0.846 | 0.823 | 0.000 | 1.649 | - | |

| Customer Experience (CE) | CE1 | 0.811 | - | 0.000 | 2.048 | 1.415 |

| CE2 | 0.781 | 0.733 | 0.000 | 1.897 | 1.415 | |

| CE3 | 0.826 | 0.716 | 0.000 | 1.420 | 1.584 | |

| CE4 | - | 0.745 | 0.000 | 1.405 | - | |

| CE5 | - | 0.779 | 0.000 | 1.524 | 1.369 | |

| Convenience (CNV) | CNV1 | 0.791 | 0.818 | 0.000 | - | 1.725 |

| CNV2 | 0.792 | 0.810 | 0.000 | - | 1.387 | |

| CNV3 | 0.767 | 0.806 | 0.000 | 1.711 | 1.900 | |

| Website Usability (WU) | WU2 | - | 0.769 | 0.000 | 1.906 | 2.120 |

| WU3 | 0.750 | 0.777 | 0.000 | 1.827 | 2.122 | |

| WU4 | 0.701 | 0.794 | 0.000 | 1.374 | 1.403 | |

| WU5 | 0.775 | 0.782 | 0.000 | 1.519 | 1.516 | |

| WU6 | 0.780 | 0.795 | 0.000 | 1.564 | - | |

| WU7 | 0.756 | 0.803 | 0.000 | - | 1.406 | |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Rho_A | Rho_C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual customer model | Customer experience | 0.731 | 0.733 | 0.848 |

| Customer satisfaction | 0.740 | 0.747 | 0.851 | |

| Functional clues | 0.829 | 0.834 | 0.879 | |

| Humanic clues | 0.818 | 0.827 | 0.891 | |

| Mechanic clues | 0.868 | 0.874 | 0.898 | |

| Corporate customer model | Customer experience | 0.761 | 0.767 | 0.848 |

| Customer satisfaction | 0.728 | 0.730 | 0.846 | |

| Functional clues | 0.830 | 0.835 | 0.887 | |

| Humanic clues | 0.703 | 0.705 | 0.870 | |

| Mechanic clues | 0.871 | 0.874 | 0.901 |

| CE | CS | FC | HC | MC | AVE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual customer model | CE | 0.650 | |||||

| CS | 0.782 | 0.655 | |||||

| FC | 0.669 | 0.754 | 0.592 | ||||

| HC | 0.872 | 0.599 | 0.891 | 0.732 | |||

| MC | 0.767 | 0.809 | 0.899 | 0.848 | 0.558 | ||

| Corporate customer model | CE | 0.582 | |||||

| CS | 0.812 | 0.648 | |||||

| FC | 0.782 | 0.793 | 0.663 | ||||

| HC | 0.605 | 0.613 | 0.648 | 0.771 | |||

| MC | 0.545 | 0.566 | 0.581 | 0.593 | 0.564 |

| Individual Customer | Decision | |||||

| β | p-Value | f-Square | ||||

| H1(a) | FC → CS | 0.054 | 0.412 | 1.254 | Supported | |

| H1(b) | MC → CS | 0.760 | 0.001 * | 1.814 | Supported | |

| H1(c) | HC → CS | −0.110 | 0.392 | 1.215 | Not Supported | |

| Corporate Customer | ||||||

| β | p-Value | f-Square | ||||

| H1(d) | FC → CS | −0.100 | 0.381 | 1.203 | Not Supported | |

| H1(e) | MC → CS | 1.028 | 0.000 * | 1.728 | Supported | |

| H1(f) | HC → CS | −0.015 | 0.832 | 1.016 | Not Supported | |

| Combined Model | ||||||

| Β | t-Sta. | p-Value | ||||

| H2 | FC → CE | 0.298 | 4.096 | 0.000 * | ||

| H3 | MC → CE | 0.888 | 3.627 | 0.000 * | ||

| H4 | HC → CE | 0.003 | 7.491 | 0.000 * | ||

| H5 | CE → CS | 0.109 | 5.010 | 0.000 * | ||

| Hypothesis | Indirect Effects | β | t-Stat | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H6 | HC → CE → CS | 0.019 | 0.107 | 0.821 |

| H7 | MC → CE → CS | 0.274 | 0.526 | 0.558 |

| H8 | FC → CE → CS | 0.029 | 0.452 | 0.446 |

| Variable | Description | Unconstrained | Structured Weight | Model Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | p | β | p | χ (p) | |||

| H9 | Gender | Male | 0.647 | 0.000 | 0.926 | 0.000 | 12.819 (0.000) * |

| Female | 0.410 | 0.015 | 0.788 | 0.000 | |||

| H10 | Age | 20 years and below | 0.556 | 0.000 | 0.066 | 0.000 | 17.514 (0.000) * |

| 21–30 years | 0.977 | 0.002 | 0.082 | 0.002 | |||

| 31–40 years | 1.148 | 0.042 | 1.156 | 0.042 | |||

| 41–50 years | 0.633 | 0.000 | 1.192 | 0.000 | |||

| 51–60 years | 0.252 | 0.001 | 0.044 | 0.001 | |||

| 61 years and above | 0.041 | 0.004 | 0.070 | 0.004 | |||

| H11 | Education | Primary school | 0.025 | 0.000 | 0.05 | 0.000 | 10.686 (0.000) * |

| Secondary school | 0.189 | 0.000 | 0.39 | 0.002 | |||

| High school | 0.368 | 0.000 | 0.44 | 0.042 | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 0.743 | 0.000 | 1.03 | 0.000 | |||

| Two-year degree | 1.981 | 0.000 | 1.64 | 0.000 | |||

| Master’s degree and above | 1.452 | 0.000 | 1.65 | 0.000 | |||

| H12 | Occupation | Private sector employee | 0.113 | 0.000 | 0.551 | 0.000 | 8.193 (0.000) * |

| Public sector employee | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.890 | 0.000 | |||

| Retired | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.140 | 0.001 | |||

| Self-employed | 0.630 | 0.000 | 1.03 | 0.000 | |||

| Business owner | 1.400 | 0.000 | 0.015 | 0.001 | |||

| Others | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.044 | 0.001 | |||

| H13 | Income (TRY) | 15,750 and less | 0.172 | 0.000 | 0.263 | 0.028 | 11.714 (0.000) * |

| 15,750 to 20,000 | 0.272 | 0.000 | 0.287 | 0.016 | |||

| 20,000 to 25,000 | 0.593 | 0.000 | 0.196 | 0.039 | |||

| 25,000 to 30,000 | 0.622 | 0.000 | 1.032 | 0.000 | |||

| 30,000 to 35,000 | 0.548 | 0.000 | 1.150 | 0.000 | |||

| 35,000 to 40,000 | 0.716 | 0.000 | 1.770 | 0.000 | |||

| 45,000 and more | 0.945 | 0.000 | 1.100 | 0.000 | |||

| No. | Hypothesis | Decision |

|---|---|---|

| H1 | Online banking service clues (mechanic clues) have a direct positive relationship with individual and corporate online banking customers’ satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H2 | Online banking service clues (functional clues) have a direct positive relationship with customer experience. | Accepted |

| H3 | Online banking service clues (mechanic clues) have a direct positive relationship with customer experience. | Accepted |

| H4 | Online banking service clues (humanic clues) have a direct positive relationship with customer experience. | Accepted |

| H5 | Customer experience has a direct positive relationship with customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H6 | Customer experience mediates the effects of online banking service clues (functional clues) on customer satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H7 | Customer experience mediates the effects of online banking service clues (mechanic clues) on customer satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H8 | Customer experience mediates the effects of online banking service clues (humanic clues) on customer satisfaction. | Rejected |

| H9 | Gender has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between online banking service clues and customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H10 | Age has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between online banking service clues and customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H10a | Risk aversion (linked to cybersecurity concerns in Northern Cyprus’s fragmented digital infrastructure) weakens the positive impact of mechanic clues on customer experience, particularly among older demographics. | Accepted |

| H11 | Education level has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between online banking service clues and customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H12 | Occupation has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between online banking service clues and customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

| H12a | Trust in online banking (rooted in post-2013 financial crisis skepticism) moderates the relationship between functional clues and satisfaction, with stronger effects for corporate customers. | Accepted |

| H13 | Income level has a significant moderating effect on the relationship between online banking service clues and customer satisfaction. | Accepted |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dağaşaner, S.; Karaatmaca, A.G. The Role of Online Banking Service Clues in Enhancing Individual and Corporate Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience as a Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083457

Dağaşaner S, Karaatmaca AG. The Role of Online Banking Service Clues in Enhancing Individual and Corporate Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience as a Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083457

Chicago/Turabian StyleDağaşaner, Suzan, and Ayşe Gözde Karaatmaca. 2025. "The Role of Online Banking Service Clues in Enhancing Individual and Corporate Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience as a Corporate Social Responsibility" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083457

APA StyleDağaşaner, S., & Karaatmaca, A. G. (2025). The Role of Online Banking Service Clues in Enhancing Individual and Corporate Customers’ Satisfaction: The Mediating Role of Customer Experience as a Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability, 17(8), 3457. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083457