Sustainable Event Tourism: Risk Perception and Preventive Measures in On-Site Attendance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

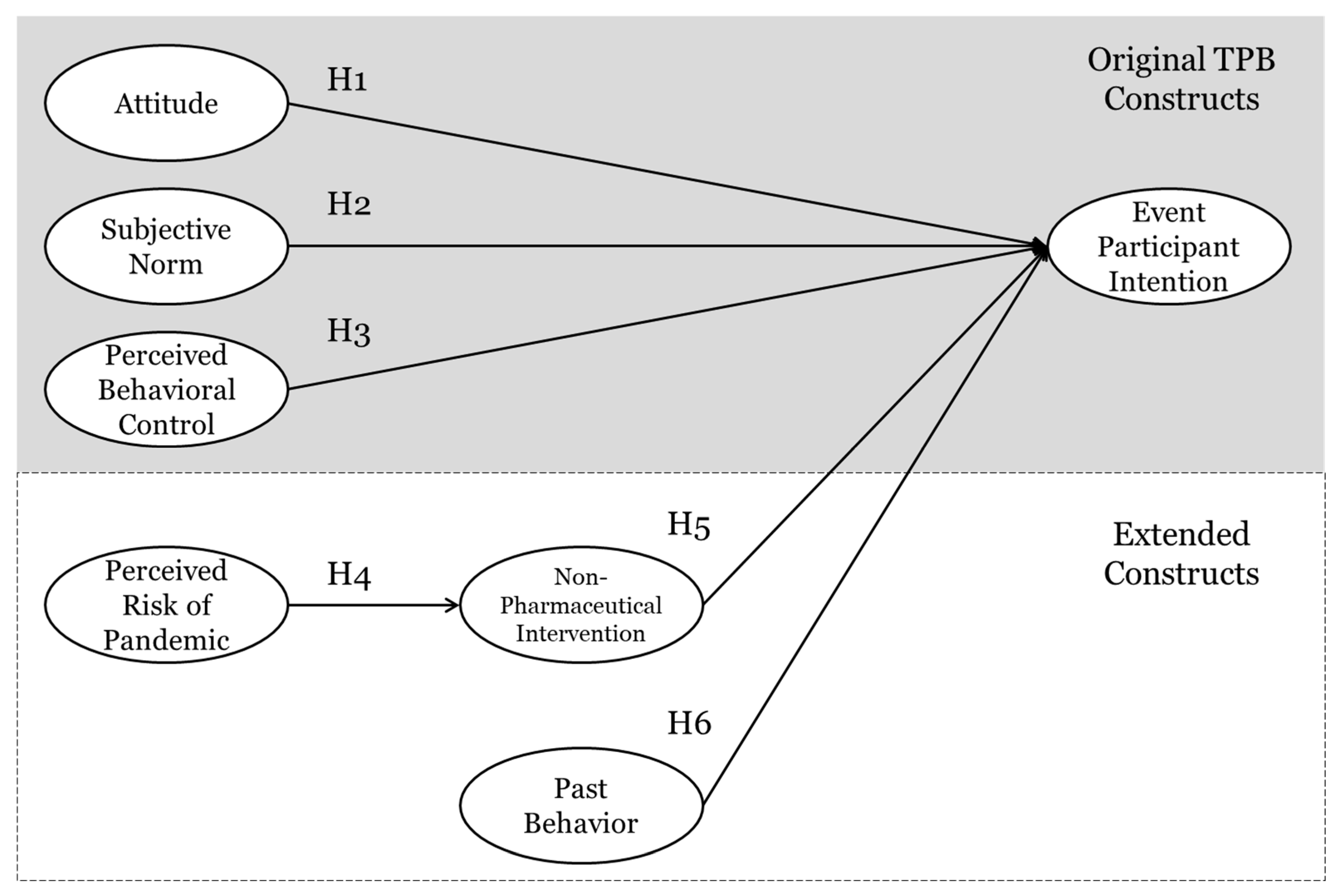

2.1. Theory of Planned Behavior

2.1.1. Attitude

2.1.2. Subjective Norms

2.1.3. Perceived Behavioral Control

2.1.4. Intention

2.1.5. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Tourism

2.2. Extension of the Theory of Planned Behavior

2.2.1. Perceived Risk for COVID-19

2.2.2. Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for COVID-19

2.2.3. Past Behavior

2.3. Hypotheses Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Measurements

3.2. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic Characteristics

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

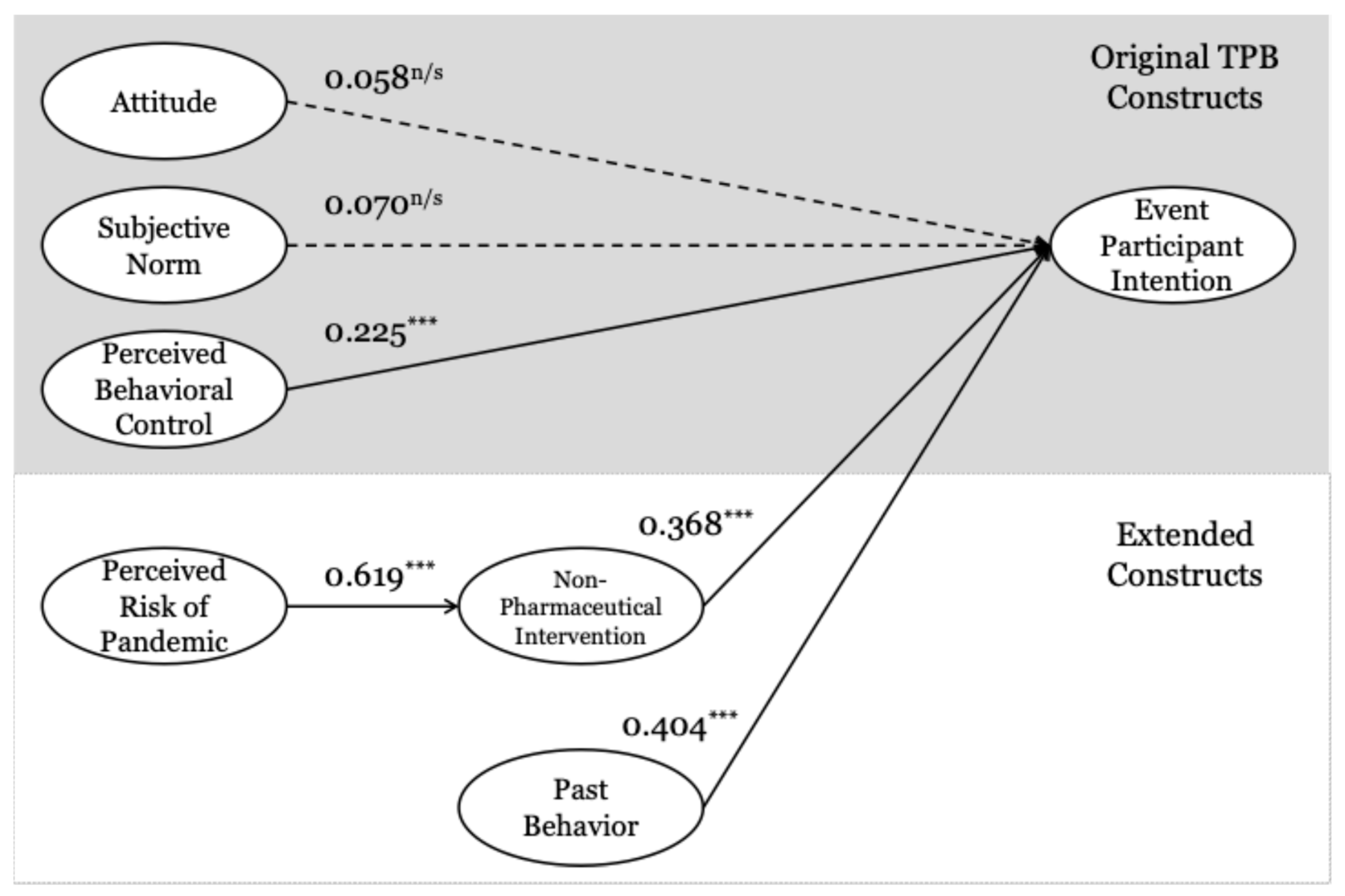

4.3. Hypothesis Testing

5. Conclusions

5.1. Conclusion

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, X.; Qing, Y.; Kang, S. Research on the Dynamic Mechanism and Path of the Integration of E-Sports Industry and Tourism Industry. Guangxi Qual. Superv. Her. 2019, 9, 200. [Google Scholar]

- Pu, H.; Xiao, S.; Kota, R.W. Virtual Games Meet Physical Playground: Exploring and Measuring Motivations for Live Esports Event Attendance. Sport Soc. 2022, 25, 1886–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharpal, A. China Remains the World’s Largest e-Sports Market despite Gaming Crackdown. Available online: https://www.cnbc.com/2022/07/15/china-is-worlds-largest-e-sports-market-despite-crackdown-study.html (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Wu, Y. More Than a Hobby: Understanding the Esports Market in China. Available online: https://www.china-briefing.com/news/esports-market-china-business-scope/ (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Zhao, L. 电竞旅游:问题及发展策略. Mod. Bus. Trade Ind. 2018, 24, 22–24. Available online: https://caod.oriprobe.com/order.htm?id=54016624&ftext=base (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Stewart, J. Traditional Chinese Tower Illuminated Red and Blue to Commemorate League of Legends World Championships. 2017. Available online: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/~/article-4970634/index.html (accessed on 12 April 2024).

- Lee, C.-K.; Song, H.-J.; Bendle, L.J.; Kim, M.-J.; Han, H. The Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for 2009 H1N1 Influenza on Travel Intentions: A Model of Goal-Directed Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reisinger, Y.; Mavondo, F. Travel Anxiety and Intentions to Travel Internationally: Implications of Travel Risk Perception. J. Travel Res. 2005, 43, 212–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyeiwaah, E.; Adam, I.; Dayour, F.; Badu Baiden, F. Perceived Impacts of COVID-19 on Risk Perceptions, Emotions, and Travel Intentions: Evidence from Macau Higher Educational Institutions. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2021, 46, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuster, V.; Turco, J.V. COVID-19: A Lesson in Humility and an Opportunity for Sagacity and Hope. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2625–2626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Deng, F. How to Influence Rural Tourism Intention by Risk Knowledge during COVID-19 Containment in China: Mediating Role of Risk Perception and Attitude. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins-Desbiolles, F. Socialising Tourism for Social and Ecological Justice after COVID-19. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juschten, M.; Jiricka-Pürrer, A.; Unbehaun, W.; Hössinger, R. The Mountains Are Calling! An Extended TPB Model for Understanding Metropolitan Residents’ Intentions to Visit Nearby Alpine Destinations in Summer. Tour. Manag. 2019, 75, 293–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuzhanin, S.; Fisher, D. The Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behavior for Predicting Intentions to Choose a Travel Destination: A Review. Tour. Rev. 2016, 71, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Predicting Behavioral Intention of Choosing a Travel Destination. Tour. Manag. 2006, 27, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulker-Demirel, E.; Ciftci, G. A Systematic Literature Review of the Theory of Planned Behavior in Tourism, Leisure and Hospitality Management Research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 43, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behavior. In Action Control: From Cognition to Behavior; Kuhl, J., Beckmann, J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 11–39. ISBN 978-3-642-69748-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior; Prentice Hall: Englewood-Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Rousan, R.A.; Khasawneh, N.; Sujood; Bano, N. Post-Pandemic Intention to Participate in the Tourism and Hospitality (T&H) Events: An Integrated Investigation through the Lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior and Perception of COVID-19. Int. J. Event Festiv. Manag. 2023, 14, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.Y.; Chang, P.-J. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19) Risk Perception on Behavioural Intention towards ‘Untact’ Tourism in South Korea during the First Wave of the Pandemic (March 2020). Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1017–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, V.G.; Lee, C.-K.; Kim, M.J.; Kim, Y.S. Impacts of Perception and Perceived Constraint on the Travel Decision-Making Process during the Hong Kong Protests. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 2093–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, Y. Unveiling the Impact of Consumer Animosity and Risk Perception on Tourists’ Decision-Making. J. Vacat. Mark. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: Orlando, FL, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-0-15-500097-1. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Lee, S.; Lee, C.-K. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior: Visa Exemptions and the Traveller Decision-Making Process. Tour. Geogr. 2011, 13, 45–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R.P.; Dholakia, U.M.; Basuroy, S. How Effortful Decisions Get Enacted: The Motivating Role of Decision Processes, Desires, and Anticipated Emotions. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 2003, 16, 273–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Predicting and Changing Behavior: The Reasoned Action Approach; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2011; ISBN 978-1-136-87473-4. [Google Scholar]

- Nimri, R.; Patiar, A.; Jin, X. The Determinants of Consumers’ Intention of Purchasing Green Hotel Accommodation: Extending the Theory of Planned Behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 45, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Frequently Asked Questions. Hum. Behav. Emerg. Tach. 2020, 2, 299–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B.; Pan, G.W. Chinese Outbound Tourists: Understanding Their Attitudes, Constraints and Use of Information Sources. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Huang, S. An Extension of Planned Behavior Model for Tourists. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 36, 390–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhao, D. Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior to Understand Consumers’ Intentions to Visit Green Hotels in the Chinese Context. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 30, 2810–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-F.; Tung, P.-J. Developing an Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model to Predict Consumers’ Intention to Visit Green Hotels. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 36, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, P.M. The Volitional Benefits of Planning. In The Psychology of Aciton: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behavior; Gollwitzer, P.M., Bargh, J.A., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 287–312. ISBN 1-57230-032-9. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.; Schüttemeyer, A.; Braun, B. Visitors’ Intention to Visit World Cultural Heritage Sites: An Empirical Study of Suzhou, China. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2009, 26, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.-J.; You, G.-J.; Reisinger, Y.; Lee, C.-K.; Lee, S.-K. Behavioral Intention of Visitors to an Oriental Medicine Festival: An Extended Model of Goal Directed Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2014, 42, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosnjak, M.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. The Theory of Planned Behavior: Selected Recent Advances and Applications. Eur. J. Psychol. 2020, 16, 352–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, D.G. An Investigation of Visitor Behaviour in Recreation and Tourism Settings: A Case Study of Natural Hazard Management at the Glaciers, Westland National Park, New Zealand. Master’s Thesis, Lincoln University, Lincoln, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Ham, S.H.; Hughes, M. Picking up Litter: An Application of Theory-Based Communication to Influence Tourist Behaviour in Protected Areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 2010, 18, 879–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepp, A. Residents’ Attitudes towards Tourism in Bigodi Village, Uganda. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.S.; Ramamonjiarivelo, Z.; Martin, W.S. MEDTOUR: A Scale for Measuring Medical Tourism Intentions. Tour. Rev. 2011, 66, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Han, H.; Lockyer, T. Medical Tourism: Attracting Japanese Tourists for Medical Tourism Experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2012, 29, 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sparks, B. Planning a Wine Tourism Vacation? Factors That Help to Predict Tourist Behavioural Intentions. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1180–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekadu, Z.; Kraft, P. Self-Identity in Planned Behavior Perspective: Past Behavior and Its Moderating Effects on Self-Identity-Intention Relations. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2001, 29, 671–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalot, F.; Quiamzade, A.; Falomir-Pichastor, J.M.; Gollwitzer, P.M. When Does Self-Identity Predict Intention to Act Green? A Self-Completion Account Relying on Past Behaviour and Majority-Minority Support for pro-Environmental Values. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 61, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hwang, J.; Kim, J.; Jung, H. Guests’ pro-Environmental Decision-Making Process: Broadening the Norm Activation Framework in a Lodging Context. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 47, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and Intention in Everyday Life: The Multiple Processes by Which Past Behavior Predicts Future Behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Polet, J.; Lintunen, T. The Reasoned Action Approach Applied to Health Behavior: Role of Past Behavior and Tests of Some Key Moderators Using Meta-Analytic Structural Equation Modeling. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018, 213, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarimoglu, E.; Gunay, T. The Extended Theory of Planned Behavior in Turkish Customers’ Intentions to Visit Green Hotels. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2020, 29, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.R. Cognitive Psychology and Its Implications, 9th ed.; Worth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2020; ISBN 978-1-319-10699-7. [Google Scholar]

- Chien, P.M.; Sharifpour, M.; Ritchie, B.W.; Watson, B. Travelers’ Health Risk Perceptions and Protective Behavior: A Psychological Approach. J. Travel Res. 2017, 56, 744–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V.-W. Consumer Perceived Risk: Conceptualisations and Models. Eur. J. Mark. 1999, 33, 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simcock, P.; Sudbury, L.; Wright, G. Age, Perceived Risk and Satisfaction in Consumer Decision Making: A Review and Extension. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Choi, K.H.; Leopkey, B. The Influence of Tourist Risk Perceptions on Travel Intention to Mega Sporting Event Destinations with Different Levels of Risk. Tour. Econ. 2021, 27, 419–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, A. Examining the Moderating Effect of Host Country Image on the Relationship between Tourists’ Motivation and Their Intention to Visit Mega Sporting Events in India. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2024, 25, 212–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, C. Event Tourism: A Strategic Methodology for Emergency Management. J. Bus. Contin. Emerg. Plan. 2009, 3, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, S.J. Current Issue in Tourism: The Evolution of Travel Medicine Research: A New Research Agenda for Tourism? Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, N.T.; Weinstein, N.D.; Cuite, C.L.; Herrington, J.E. Risk Perceptions and Their Relation to Risk Behavior. Ann. Behav. Med. 2004, 27, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Dai, S.; Xu, H. Predicting Tourists’ Health Risk Preventative Behaviour and Travelling Satisfaction in Tibet: Combining the Theory of Planned Behaviour and Health Belief Model. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2020, 33, 100589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menon, G.; Raghubir, P.; Agrawal, N. Health Risk Perceptions and Consumer Psychology. In Handbook of Consumer Psychology; Haugtvedt, C.P., Herr, P.M., Kardes, F.R., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2008; p. 39. ISBN 978-1-315-64836-1. [Google Scholar]

- Rittichainuwat, B.N.; Chakraborty, G. Perceived Travel Risks Regarding Terrorism and Disease: The Case of Thailand. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshitani, H. Potential Benefits and Limitations of Various Strategies to Mitigate the Impact of an Influenza Pandemic. J. Infect. Chemother. 2006, 12, 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, S.; Ruktanonchai, N.W.; Zhou, L.; Prosper, O.; Luo, W.; Floyd, J.R.; Wesolowski, A.; Santillana, M.; Zhang, C.; Du, X.; et al. Effect of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions to Contain COVID-19 in China. Nature 2020, 585, 410–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aledort, J.E.; Lurie, N.; Wasserman, J.; Bozzette, S.A. Non-Pharmaceutical Public Health Interventions for Pandemic Influenza: An Evaluation of the Evidence Base. BMC Public Health 2007, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The National Health Commission Held a Press Conference to Introduce the Prevention of Common Diseases in Winter and Spring and Health Tips during the Holidays. Available online: https://www.chinacdc.cn/yyrdgz/201912/t20191230_210922.html (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Imai, N.; Gaythorpe, K.A.M.; Abbott, S.; Bhatia, S.; van Elsland, S.; Prem, K.; Liu, Y.; Ferguson, N.M. Adoption and Impact of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions for COVID-19. Wellcome Open Res. 2020, 5, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, J.; Rogers, M.B.; Marteau, T.M.; Yardley, L.; Reicher, S.; Stott, C. Re-Opening Live Events and Large Venues after Covid-19 ‘Lockdown’: Behavioural Risks and Their Mitigations. Saf. Sci. 2021, 139, 105243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; Gao, W. Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions in Containing COVID-19 Pandemic after the Roll-out of Coronavirus Vaccines: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, L. The Theory of Planned Behaviour and the Impact of Past Behaviour. Int. Bus. Econ. Res. J. 2011, 10, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aarts, H. Health and Goal-Directed Behavior: The Nonconscious Regulation and Motivation of Goals and Their Pursuit. Health Psychol. Rev. 2007, 1, 53–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronis, D.L.; Yates, J.F.; Kirscht, J.P. Attitudes, Decisions and Habits as Determinants of Repeated Behaviour. In Attitude Structure and Function; Pratkanis, A.R., Breckler, S.J., Greenwald, A.G., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-1-315-80178-0. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Residual Effects of Past on Later Behavior: Habituation and Reasoned Action Perspectives. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 2002, 6, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schank, R.C.; Abelson, R.P. Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story. In Knowledge and Memory: The Real Story; Wyer, R.S., Ed.; Advances in Social Cognition; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume VIII, pp. 1–86. ISBN 978-1-317-78101-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Lam, T.; Hsu, C.H.C. Negative Word-of-Mouth Communication Intention: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2006, 30, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, E.W.; Al-Gahtani, S.S.; Hubona, G.S. The Effects of Gender and Age on New Technology Implementation in a Developing Country: Testing the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Inf. Technol. People 2007, 20, 352–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.; Ren, R. Do Chinese Viewers Watch E-Sports Games for a Different Reason? Motivations, Attitude, and Team Identification in Predicting e-Sports Online Spectatorship. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1234305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, S.; Manca, F.; Nielsen, T.A.S.; Prato, C.G. Intentions to Use Bike-Sharing for Holiday Cycling: An Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Tour. Manag. 2015, 47, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Hsu, L.-T.; Sheu, C. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Green Hotel Choice: Testing the Effect of Environmental Friendly Activities. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ziadat, M.T. Applications of Planned Behavior Theory (TPB) in Jordanian Tourism. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, M.-C. The Management of Sports Tourism: A Causal Modeling Test of the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Int. J. Manag. 2013, 30, 474–491. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Bruwer, J.; Song, H. Experiential and Involvement Effects on the Korean Wine Tourist’s Decision-Making Process. Curr. Issues Tour. 2017, 20, 1215–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.C.; Kang, S.K.; Lam, T. Reference Group Influences among Chinese Travelers. J. Travel Res. 2006, 44, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, N.D. The Precaution Adoption Process. Health Psychol. 1988, 7, 355–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catania, J.A.; Kegeles, S.M.; Coates, T.J. Towards an Understanding of Risk Behavior: An AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM). Health Educ. Q. 1990, 17, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mermelstein, R.J.; Riesenberg, L.A. Changing Knowledge and Attitudes about Skin Cancer Risk Factors in Adolescents. Health Psychol. 1992, 11, 371–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rippetoe, P.A.; Rogers, R.W. Effects of Components of Protection-Motivation Theory on Adaptive and Maladaptive Coping with a Health Threat. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1987, 52, 596–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raude, J.; Setbon, M. Lay Perceptions of the Pandemic Influenza Threat. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 24, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.-L.; Luo, W.; Li, H.-M.; Zhang, Q.-Q.; Liu, X.-G.; Li, W.-T.; Li, Y. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices towards COVID-19 among Chinese Residents during the Rapid Rise Period of the COVID-19 Outbreak: A Quick Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 16, 1745–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Bonn, M.; Hall, C.M. What Influences COVID-19 Biosecurity Behaviour for Tourism? Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 25, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Amin, A. Factors Influencing Chinese Residents’ Post-Pandemic Outbound Travel Intentions: An Extended Theory of Planned Behavior Model Based on the Perception of COVID-19. Tour. Rev. 2021, 76, 871–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forward, S.E. The Theory of Planned Behaviour: The Role of Descriptive Norms and Past Behaviour in the Prediction of Drivers’ Intentions to Violate. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2009, 12, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetvaroon, K. Application of the Theory of Planned Behavior to Select a Destination after a Crisis: A Case Study of Phuket, Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater, OK, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi, C.; Milberg, S.; Cúneo, A. Understanding Travelers’ Intentions to Visit a Short versus Long-Haul Emerging Vacation Destination: The Case of Chile. Tour. Manag. 2017, 59, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, Y. An Investigation of Green Hotel Customers’ Decision Formation: Developing an Extended Model of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 659–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kim, W.; Hyun, S.S. Overseas Travelers’ Decision Formation for Airport-Shopping Behavior. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2014, 31, 985–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M.; Bagozzi, R.P. The Role of Desires and Anticipated Emotions in Goal-Directed Behaviours: Broadening and Deepening the Theory of Planned Behaviour. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001, 40, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.-K.; Song, H.-J.; Bendle, L.J. The Impact of Visa-Free Entry on Outbound Tourism: A Case Study of South Korean Travellers Visiting Japan. Tour. Geogr. 2010, 12, 302–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagger, M.S.; Chatzisarantis, N.L.D.; Barkoukis, V.; Wang, J.C.K.; Hein, V.; Pihu, M.; Soós, I.; Karsai, I. Cross-Cultural Generalizability of the Theory of Planned Behavior among Young People in a Physical Activity Context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 2007, 29, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, N.; Chen, N. Young People’s Behavioral Intentions towards Low-Carbon Travel: Extending the Theory of Planned Behavior. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horng, J.-S.; Su, C.-S.; So, S.-I.A. Segmenting Food Festival Visitors: Applying the Theory of Planned Behavior and Lifestyle. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2013, 14, 193–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khaldy, D.A.W.; Hassan, T.H.; Abdou, A.H.; Abdelmoaty, M.A.; Salem, A.E. The Effects of Social Networking Services on Tourists’ Intention to Visit Mega-Events during the Riyadh Season: A Theory of Planned Behavior Model. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.J.; Ellen, P.S.; Ajzen, I. A Comparison of the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Theory of Reasoned Action. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 18, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintal, V.A.; Lee, J.A.; Soutar, G.N. Risk, Uncertainty and the Theory of Planned Behavior: A Tourism Example. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prayag, G. Symbiotic Relationship or Not? Understanding Resilience and Crisis Management in Tourism. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2018, 25, 133–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Hughey, K.F.D. Linking Tourism into Emergency Management Structures to Enhance Disaster Risk Reduction. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ai, J.; Bao, J.; Zhang, W. Lessons Learned from the COVID-19 Control Strategy of the XXXII Tokyo Summer Olympics and the XXIV Beijing Winter Olympics. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 1711–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplanidou, K.; Vogt, C. The Interrelationship between Sport Event and Destination Image and Sport Tourists’ Behaviour. J. Sport Tour. 2007, 12, 183–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKercher, B.; Tse, T.S. Is Intention to Return a Valid Proxy for Actual Repeat Visitation? J. Travel Res. 2012, 51, 671–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | n | % | Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Education | ||||

| Male | 339 | 81.7 | Elementary school | 1 | 0.2 |

| Female | 73 | 17.6 | (Junior) High school | 14 | 3.4 |

| Others | 3 | 0.7 | 2-year vocational/technical school | 90 | 21.7 |

| Marital status | 4-year university | 289 | 69.6 | ||

| Single | 281 | 67.7 | Postgraduate or above | 21 | 5.1 |

| Married | 131 | 31.6 | Personal monthly income (RMB) | ||

| Divorced/separated | 2 | 0.5 | 2499 or below | 51 | 12.3 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.2 | 2500–4999 | 47 | 11.3 |

| Occupation | 5000–9999 | 128 | 30.8 | ||

| Self-employed | 29 | 7 | 10,000–14,999 | 100 | 24.1 |

| Employed for wages | 235 | 56.6 | 15,000–19,999 | 48 | 11.6 |

| Public official | 49 | 11.8 | 20,000–24,999 | 22 | 5.3 |

| Student | 83 | 20 | 25,000–29,999 | 7 | 1.7 |

| Homemaker | 4 | 1 | 30,000 or above | 12 | 2.9 |

| Out of work and looking for work | 8 | 1.9 | Place of residence | ||

| Out of work but not currently looking for work | 2 | 0.5 | Shanghai and neighboring areas (Anhui Province, Jiangsu Province, and Zhejiang Province) | 80 | 19.3 |

| Other | 5 | 1.2 | Places far from Shanghai | 335 | 80.7 |

| Variables | Std. Coefficient ** | Mean |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude (AVE = 0.721; CR = 0.928) | ||

| I think that attending the Worlds 2020 final is wise. | 0.797 | 4.25 |

| I think that attending the Worlds 2020 final is pleasant. | 0.861 | 4.25 |

| I think that attending the Worlds 2020 final is exciting. | 0.865 | 4.35 |

| I think that attending the Worlds 2020 final is attractive. | 0.862 | 4.29 |

| I think that attending the Worlds 2020 final is valuable. | 0.858 | 4.30 |

| Subjective Norm (AVE = 0.744; CR = 0.936) | ||

| Most people who are important to me support my decision to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.855 | 4.05 |

| Most people who are important to me understand that I visit Worlds 2020 final. | 0.845 | 4.05 |

| Most people who are important to me agree with me about attending the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.878 | 4.00 |

| Most people who are important to me recommend my attending the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.879 | 3.94 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (AVE = 0.658; CR = 0.905) | ||

| Whether or not I attend the Worlds 2020 final is completely up to me. | 0.698 | 4.10 |

| I am confident that if I want to, I can attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.806 | 3.82 |

| I have enough money to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.871 | 3.71 |

| I have enough time to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.821 | 3.83 |

| I have an opportunity to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.850 | 3.65 |

| Perceived Risk of COVID-19 (AVE = 0.508; CR = 0.747) | ||

| It is dangerous to attend the Worlds 2020 final because of COVID-19. | 0.479 | 3.47 |

| COVID-19 is a very frightening disease. | 0.845 | 4.04 |

| I am afraid of COVID-19. | 0.762 | 3.84 |

| Non-Pharmaceutical Intervention for COVID-19 (AVE = 0.694; CR = 0.919) | ||

| I will check the information about the situation for Shanghai’s COVID-19 infection on the internet before attending the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.801 | 4.33 |

| I will read and check precautions about COVID-19 before attending the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.857 | 4.24 |

| I will disinfect my hands with alcohol frequently while visiting Worlds 2020 final. | 0.800 | 4.27 |

| I will wear a mask while visiting Worlds 2020 final. | 0.861 | 4.32 |

| I will carefully keep an eye on my health condition after returning from Worlds 2020 final trip. | 0.844 | 4.36 |

| Past Behavior (AVE = 0.759; CR = 0.863) | ||

| I have frequently attended the League of Legends World Championship in the past three years. | 0.919 | 3.80 |

| How often have you visited the League of Legends World Championship during the past three years? * | 0.821 | 2.79 |

| Event Participation Intention (AVE = 0.712; CR = 0.925) | ||

| I am willing to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.814 | 4.42 |

| I plan to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.866 | 4.26 |

| I will make an effort to attend Worlds 2020 final. | 0.883 | 4.08 |

| I intend to go to the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.856 | 4.28 |

| I will certainly invest time and money to attend the Worlds 2020 final. | 0.795 | 4.35 |

| ATT | SN | PBC | RISK | INT | PB | EPI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.849 | ||||||

| SN | 0.665 | 0.863 | |||||

| PBC | 0.495 | 0.670 | 0.811 | ||||

| Risk | 0.380 | 0.307 | 0.229 | 0.713 | |||

| INT | 0.673 | 0.463 | 0.389 | 0.546 | 0.833 | ||

| PB | 0.380 | 0.609 | 0.580 | 0.279 | 0.367 | 0.871 | |

| EPI | 0.575 | 0.634 | 0.638 | 0.353 | 0.644 | 0.695 | 0.844 |

| AVE | 0.721 | 0.744 | 0.658 | 0.508 | 0.694 | 0.759 | 0.712 |

| Hypotheses | Results |

|---|---|

| H1: Individuals’ attitudes toward attending on-site e-sports events are positively associated with their intentions to participate. | Failed to reject |

| H2: Individuals’ subjective norms toward attending e-sports events are positively associated with their intentions to attend. | Failed to reject |

| H3: Individuals’ perceived behavioral control over attending e-sports events is positively associated with their intentions to attend. | Reject |

| H4: Perceived risk of COVID-19 is positively associated with adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions during e-sports event attendance. | Reject |

| H5: Individuals’ adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) is positively associated with their intention to attend on-site e-sports events during COVID-19. | Reject |

| H6: Individuals’ past attendance behaviors are positively associated with their intentions to attend e-sports events. | Reject |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Choe, Y.; Kang, S.; Lee, J. Sustainable Event Tourism: Risk Perception and Preventive Measures in On-Site Attendance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083455

Li B, Choe Y, Kang S, Lee J. Sustainable Event Tourism: Risk Perception and Preventive Measures in On-Site Attendance. Sustainability. 2025; 17(8):3455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083455

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Bijun, Yeongbae Choe, Sangguk Kang, and Jaeseok Lee. 2025. "Sustainable Event Tourism: Risk Perception and Preventive Measures in On-Site Attendance" Sustainability 17, no. 8: 3455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083455

APA StyleLi, B., Choe, Y., Kang, S., & Lee, J. (2025). Sustainable Event Tourism: Risk Perception and Preventive Measures in On-Site Attendance. Sustainability, 17(8), 3455. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17083455