Advancing Gender Equality in Executive Leadership: The Role of Cultural Norms and Organizational Practices in Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Taiwan and Guatemala

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Current Situations

1.3. Research Needs

1.4. Objectives of Study

2. Literature Review

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. Hofstede’s Cultural Dimensions Theory

3.2. Glass Ceiling Effect

4. Research Methodology

5. Findings

5.1. Demographic Characteristics

5.2. Perception Regarding Equality Factors

5.3. Impact Study

6. Discussion

6.1. Contribution Regarding Relevant Theories

6.2. Main Findings

6.3. Barriers

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ammerman, C.; Groysberg, B. Glass Half-Broken: Shattering the Barriers that Still Hold Women Back at Work; Harvard Business Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Furtado, J.V.; Moreira, A.C.; Mota, J. Gender affirmative action and management: A systematic literature review on how diversity and inclusion management affect gender equity in organizations. Behav. Sci. 2021, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belingheri, P.; Chiarello, F.; Fronzetti Colladon, A.; Rovelli, P. Twenty years of gender equality research: A scoping review based on a new semantic indicator. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0256474. [Google Scholar]

- Fine, C.; Sojo, V.; Lawford-Smith, H. Why does workplace gender diversity matter? Justice, organizational benefits, and policy. Soc. Issues Policy Rev. 2020, 14, 36–72. [Google Scholar]

- Homan, A.C.; Gündemir, S.; Buengeler, C.; van Kleef, G.A. Leading diversity: Towards a theory of functional leadership in diverse teams. J. Appl. Psychol. 2020, 105, 1101. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Richard, O.C.; Triana MD, C.; Zhang, X. The performance impact of gender diversity in the top management team and board of directors: A multiteam systems approach. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2022, 61, 157–180. [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- World Economic Forum. 2023. Available online: https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2021.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Obodo, C.A. Gender-related discrimination. In Reduced Inequalities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 289–299. [Google Scholar]

- Cortis, N.; Foley, M.; Williamson, S. Change agents or defending the status quo? How senior leaders frame workplace gender equality. Gend. Work. Organ. 2022, 29, 205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Kim-Martin, K.; Molfetto, K.; Castillo, K.; Elliott, J.L.; Rodriguez, Y.; Thompson, C.M. Bicultural Asian American women’s experience of gender roles across cultural contexts: A narrative inquiry. Qual. Psychol. 2022, 9, 62. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M. Women leaders in the workplace: Perceptions of career barriers, facilitators and change. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2020, 39, 233–253. [Google Scholar]

- Mahdi Abaker MO, S.; Patterson, H.L.; Cho, B.Y. Gender managerial obstacles in private organizations: The UAE case. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2023, 38, 454–470. [Google Scholar]

- Kaftandzieva, T.; Nakov, L. Glass Ceiling Factors Hindering Women’s Advancement in Management Hierarchy. J. Econ. Manag. Trade 2021, 27, 16–29. [Google Scholar]

- Lewellyn, K.B.; Muller-Kahle, M.I. The corporate board glass ceiling: The role of empowerment and culture in shaping board gender diversity. J. Bus. Ethics 2020, 165, 329–346. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, C.S.; Paustian-Underdahl, S.C.; Fainshmidt, S. Women on boards of directors: A meta-analytic examination of the roles of organizational leadership and national context for gender equality. J. Bus. Psychol. 2021, 36, 173–191. [Google Scholar]

- Attah-Boakye, R.; Adams, K.; Kimani, D.; Ullah, S. The impact of board gender diversity and national culture on corporate innovation: A multi-country analysis of multinational corporations operating in emerging economies. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2020, 161, 120247. [Google Scholar]

- Bonet, R.; Cappelli, P.; Hamori, M. Gender differences in speed of advancement: An empirical examination of top executives in the Fortune 100 firms. Strateg. Manag. J. 2020, 41, 708–737. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, W.; Luo, L. Gender, education, and attitudes toward women’s Leadership in Three East Asian countries: An intersectional and multilevel approach. Societies 2021, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, Á.; Khalil, N.; Tench, R. Enemy at the (house) gates: Permanence of gender discrimination in public relations career promotion in Latin America. Commun. Soc. 2021, 34, 169–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, J. Gender and politics in Northeast Asia: Legislative patterns and substantive representation in Korea and Taiwan. J. Women Politics Policy 2021, 42, 138–155. [Google Scholar]

- Żemojtel-Piotrowska, M.; Piotrowski, J. Hofstede’s cultural dimensions theory. In Encyclopedia of Sexual Psychology and Behavior; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Taparia, M.; Lenka, U. An integrated conceptual framework of the glass ceiling effect. J. Organ. Eff. People Perform. 2022, 9, 372–400. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, M.W.; Hong, Y.Y.; Chiu, C.Y.; Liu, Z. Normology: Integrating insights about social norms to understand cultural dynamics. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2015, 129, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, N.; Pahlevan Sharif, S.; Iqbal Hussain, H.B. The role of national culture in the impact of board gender diversity on firm performance: Evidence from a multi-country study. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2021, 40, 631–650. [Google Scholar]

- Stets, J.E.; Burke, P.J. Femininity/masculinity. Encycl. Sociol. 2000, 2, 997–1005. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman, P.W.; Howell, J.P.; Hibino, S.; Lee, J.K.; Tate, U.; Bautista, A. Leadership in Western and Asian countries: Commonalities and differences in effective leadership processes across cultures. Leadersh. Q. 1997, 8, 233–274. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, M.A.; Greguras, G.J. Exploring the nature of power distance: Implications for micro-and macro-level theories, processes, and outcomes. J. Manag. 2014, 40, 1202–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, D. Gendered Spaces; The University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, R.; Rupp, D.E.; Skarlicki, D.P.; Jones, K.S. Employee justice across cultures: A meta-analytic review. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 263–301. [Google Scholar]

- Fombrun, C.J. Structural dynamics within and between organizations. Adm. Sci. Q. 1986, 31, 403–421. [Google Scholar]

- Purcell, D.; MacArthur, K.R.; Samblanet, S. Gender and the glass ceiling at work. Sociol. Compass 2010, 4, 705–717. [Google Scholar]

- Acker, J. Gender and organizations. In Handbook of the Sociology of Gender; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, T.E. Job Segregation, Gender Blindness, and Employee Agency. Me. L. Rev. 2002, 55, 241. [Google Scholar]

- Lantz-Deaton, C.; Tabassum, N.; McIntosh, B. Through the glass ceiling: Is mentoring the way forward? Int. J. Hum. Resour. Dev. Manag. 2018, 18, 167–197. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, F.M.; Halpern, D.F. Women at the top: Powerful leaders define success as work + family in a culture of gender. Am. Psychol. 2010, 65, 182. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.M. Gender and the Political Economy of Development: From Nationalism to Globalization; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kuteesa, K.N.; Dagunduro, A.O.; Ediae, A.A.; Favour, C. Redefining leadership: The role of gender in shaping organizational culture. Compr. Res. Rev. Multidiscip. Stud. 2024, 02, 009–018. [Google Scholar]

- Secret, V. Gender Equality in the Workplace: The Role of Policy and Organizational Culture in Promoting Inclusivity. Int. J. Soc. Hum. Stud. 2022, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, A.H.; Mills, M.J.; Howes, S.S.; Albritton, M.D. Workplace support and affirming behaviors: Moving toward a transgender, gender diverse, and non-binary friendly workplace. Int. J. Transgender Health 2021, 22, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Alsereidi, R.H.; Ben Romdhane, S. Gender roles, gender bias, and cultural influences: Perceptions of male and female UAE public relations professionals. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Gómez, J.; Lafuente, E.; Vaillant, Y. Gender diversity in the board, women’s leadership and business performance. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2018, 33, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macarie, F.C.; Hinţea, C.; MORA, C.M. Gender and Leadership. The impact of organizational culture of public institutions. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2011, 7, 146–156. [Google Scholar]

| Demographic Factors | Frequency % | Variance | Skewness | Kurtosis | t | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 18–24 years | 29.5 | 1.010 | 0.440 | −0.431 | 51.514 |

| 25–34 years | 31.3 | |||||

| 35–44 years | 30.2 | |||||

| 45–54 years | 7.3 | |||||

| 55 years and above | 1.8 | |||||

| Industry | Technology | 22.2 | 2.158 | −0.009 | −1.391 | 47.976 |

| Finance | 18.7 | |||||

| Manufacturing | 17.6 | |||||

| Healthcare | 19.3 | |||||

| Education | 22.2 | |||||

| Years of work experience | Less than 1 year | 3.1 | 0.358 | 0.059 | −0.380 | 96.351 |

| 1–5 years | 50.4 | |||||

| 6–12 years | 44.2 | |||||

| Above 12 years | 2.4 | |||||

| Workplace diversity policies awareness | Fully aware | 40.2 | 0.557 | 0.353 | −1.138 | 56.392 |

| Somewhat aware | 40.2 | |||||

| Not aware | 19.6 | |||||

| Cultural background | Indigenous | 43.8 | 0.400 | 0.452 | −0.671 | 61.087 |

| Mixed Heritage | 47.6 | |||||

| Predominantly Western Influence | 8.5 | |||||

| Factors | Mean ± SD | t | Cronbach’s Alpha | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Gender Equality in Organizational Leadership | 4.05 ± 0.74 | 128.651 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.65 |

| Cultural Norms and Gender Roles | 4.03 ± 0.73 | 129.488 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.63 |

| Organizational Policies on Diversity and Inclusion | 3.99 ± 0.72 | 130.628 | 0.85 | 0.88 | 0.62 |

| Workplace Practices and Flexibility | 3.99 ± 0.71 | 132.197 | 0.87 | 0.89 | 0.67 |

| Leadership Development Opportunities | 3.99 ± 0.73 | 127.175 | 0.86 | 0.88 | 0.60 |

| Male-dominated Networks and Sponsorship | 3.87 ± 0.74 | 121.920 | 0.79 | 0.82 | 0.58 |

| Organizational Culture and Support | 3.97 ± 0.74 | 125.007 | 0.85 | 0.87 | 0.61 |

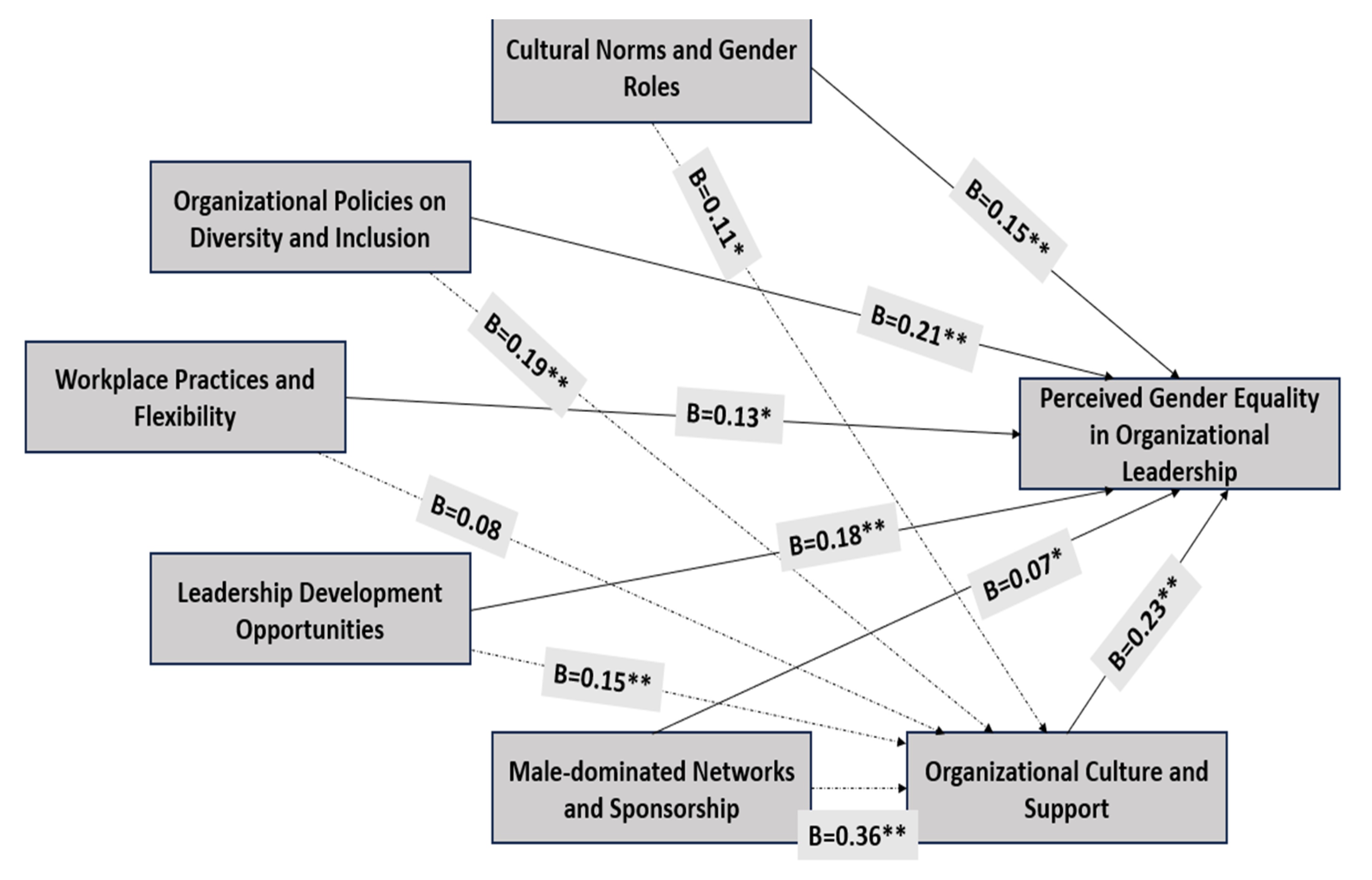

| Pathway | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p | Hypothesis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Culture and Support | <--- | Cultural Norms and Gender Roles | 0.113 | 0.051 | 2.201 | 0.028 | H6 supported (Partial mediation effect) |

| <--- | Organizational Policies on Diversity and Inclusion | 0.195 | 0.054 | 3.639 | *** | ||

| <--- | Male-dominated Networks and Sponsorship | 0.365 | 0.036 | 10.171 | *** | ||

| <--- | Leadership Development Opportunities | 0.181 | 0.049 | 3.708 | *** | ||

| <--- | Workplace Practices and Flexibility | 0.08 | 0.05 | 1.619 | 0.105 | ||

| Perceived Gender Equality in Organizational Leadership | <--- | Cultural Norms and Gender Roles | 0.153 | 0.043 | 3.516 | *** | H1 supported |

| <--- | Organizational Culture and Support | 0.227 | 0.036 | 6.306 | *** | H6 supported | |

| <--- | Organizational Policies on Diversity and Inclusion | 0.206 | 0.046 | 4.5 | *** | H2 supported | |

| <--- | Workplace Practices and Flexibility | 0.133 | 0.042 | 3.191 | 0.001 | H3 supported | |

| <--- | Leadership Development Opportunities | 0.198 | 0.042 | 4.773 | *** | H4 supported | |

| <--- | Male-dominated Networks and Sponsorship | 0.074 | 0.033 | 2.257 | 0.024 | H5 supported | |

| Fit Index | Value | Acceptable Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Chi-Square (χ2) | 345.62 | p > 0.05 (desired, but sensitive to sample size) |

| Degrees of Freedom (df) | 156 | - |

| χ2/df (Normed Chi-Square) | 2.21 | <3 (acceptable), <2 (good) |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.951 | ≥0.90 (acceptable), ≥0.95 (good) |

| Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.942 | ≥0.90 (acceptable), ≥0.95 (good) |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.051 | ≤0.08 (acceptable), ≤0.05 (good) |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.042 | ≤0.08 (acceptable), ≤0.05 (good) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saenz, C.; Wu, S.-W.; Uddaraju, V.; Nafei, A.; Liu, Y.-L. Advancing Gender Equality in Executive Leadership: The Role of Cultural Norms and Organizational Practices in Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Taiwan and Guatemala. Sustainability 2025, 17, 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073183

Saenz C, Wu S-W, Uddaraju V, Nafei A, Liu Y-L. Advancing Gender Equality in Executive Leadership: The Role of Cultural Norms and Organizational Practices in Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Taiwan and Guatemala. Sustainability. 2025; 17(7):3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073183

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaenz, Camila, Shih-Wei Wu, Venkata Uddaraju, Amirhossein Nafei, and Yu-Lun Liu. 2025. "Advancing Gender Equality in Executive Leadership: The Role of Cultural Norms and Organizational Practices in Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Taiwan and Guatemala" Sustainability 17, no. 7: 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073183

APA StyleSaenz, C., Wu, S.-W., Uddaraju, V., Nafei, A., & Liu, Y.-L. (2025). Advancing Gender Equality in Executive Leadership: The Role of Cultural Norms and Organizational Practices in Sustainable Development—A Case Study of Taiwan and Guatemala. Sustainability, 17(7), 3183. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17073183