Can the Relationship Population Contribute to Sustainable Rural Development? A Comparative Study of Out-Migrated Family Support in Depopulated Areas of Japan

Abstract

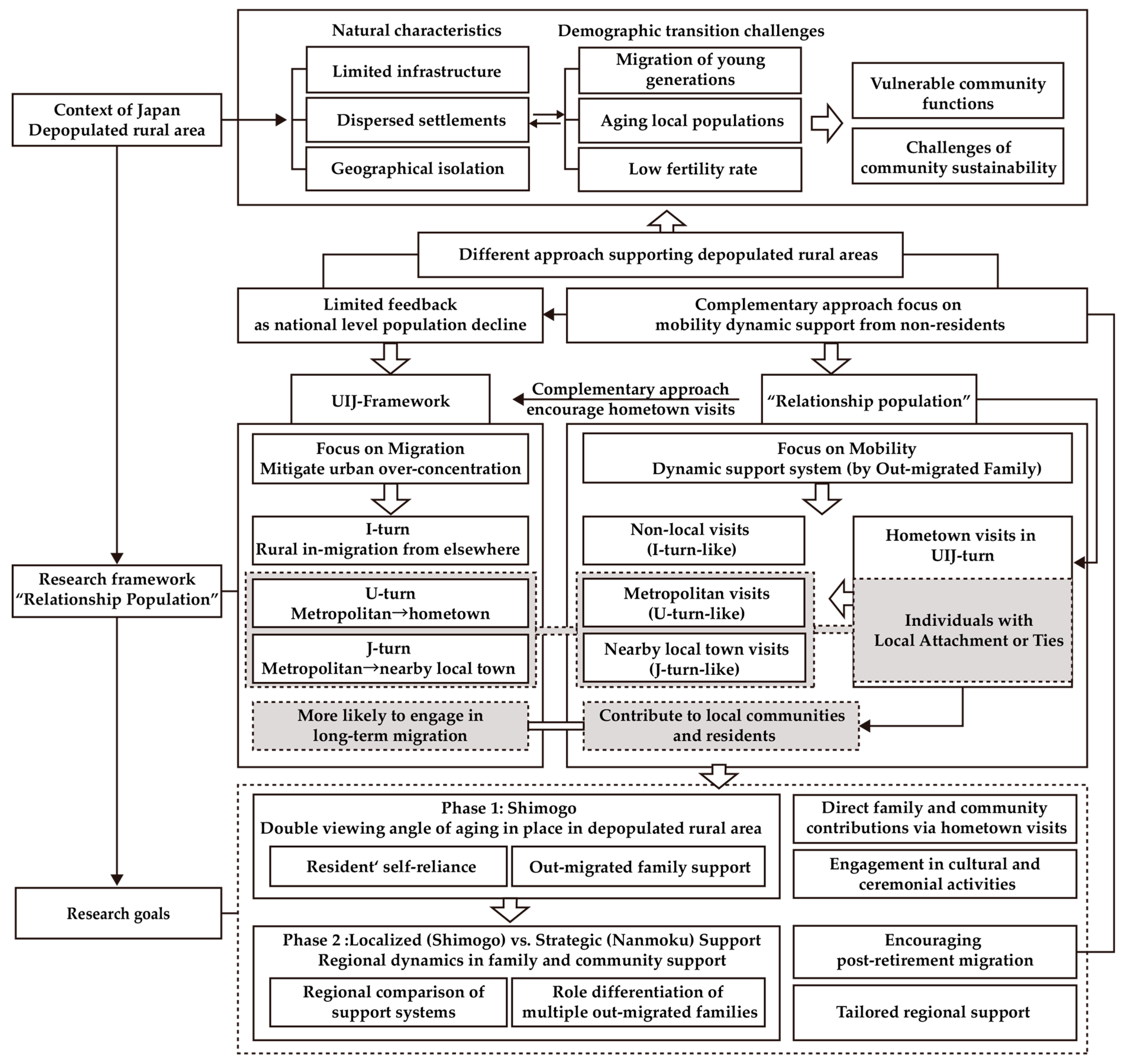

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Frameworks

2.1. Overview of the Conceptual Frameworks

2.2. Counter-Urbanization and “Denenkaiki”

2.3. The UIJ-Turn Migration

2.4. The “Relationship Population” Concept

3. Study Area

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Overview of Research Design

4.2. Questionnaire Design

4.3. Data Collection

4.4. Data Analysis

5. Results

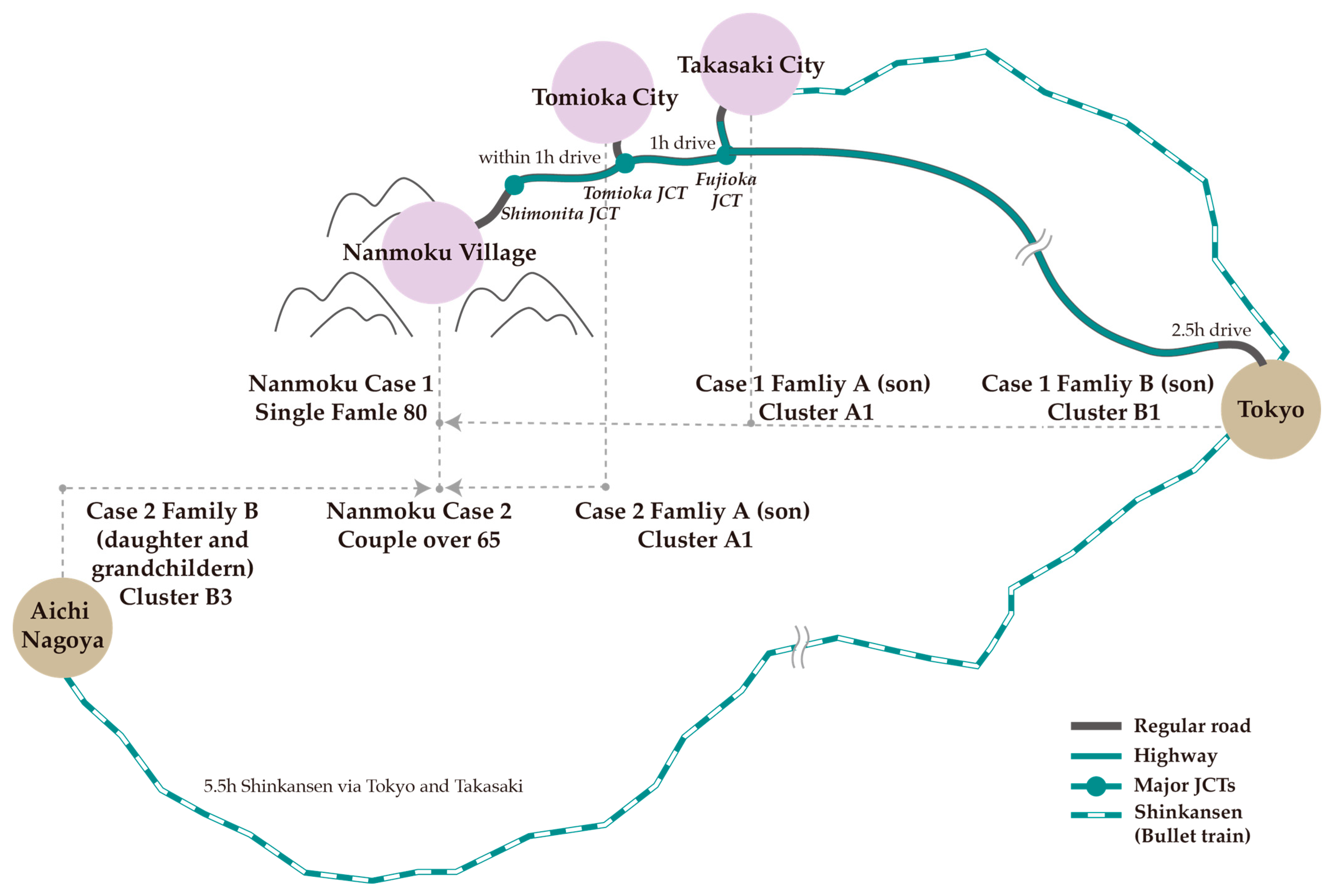

5.1. Geographic Context, Out-Migration, and Frequent Visitor Patterns

5.1.1. Resident Characteristics and Geographic Context

5.1.2. Out-Migration Patterns and the Geography of Frequent Visitors

5.2. Motivation Shapes Contribution: Analyzing Rural Support in Shimogo and Nanmoku

5.3. The Dynamic Interplay Between Isolation, Motivation, and Support Networks

5.4. Illustrative Case Studies: Lived Experiences in Nanmoku

6. Discussion

6.1. The Evolving Role of Local Towns in Depopulated Rural Areas

6.2. Beyond Obligation: Agency, the “Peasant Economy”, and the “Relationship Population”

6.3. Beyond In-Migration: Empowering the “Relationship Population” for Rural Revitalization

6.4. Strengths and Limitations

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Questionnaire Summary | Resident Households 1 | Most (Family A) and Second-Most (Family B) Frequent Hometown Visit Relatives 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Information 3 | 1. Residential area (name of settlement) | 5. Location of Visit Relatives |

| 2. Age and Gender of all family members | 6. Age | |

| 7. Frequency of Hometown Visit | ||

| 8. Relationship (kinship) to Resident Households | ||

| Healthcare And Shopping 4 | 3. Health conditions: | |

| Select the health conditions that apply to your family (multiple choice). | ||

| 3.1. All family members are in good health | ||

| 3.2. Need to go to the hospital regularly | ||

| 3.3. Uses a home visit helper | ||

| 3.4. Uses a day service (bathing, rehabilitation, etc.). | ||

| 3.5. Uses home visit medical services | ||

| 3.6. Need caregiving. | ||

| 4. Shopping (medical care) methods: | ||

| Select the shopping (medical care) conditions that apply to your family (multiple choice) | ||

| 4.1. Completed by family without others’ help | ||

| 4.2. Requires relatives to go shopping (go to hospital) with family members during their hometown visit | ||

| 4.3. Requires nearby neighbors to go shopping (go to hospital) with family members | ||

| 4.4. Relatives bring the items to our family | ||

| 4.5. Neighbors bring the items to our family | ||

| 4.6. Use mobile vending vehicles in communities | ||

| 4.7. Use online services from co-ops, Amazon, and others | ||

| Purpose of Hometown-Visiting | 9. Purpose of Hometown-Visiting | |

| Select the main purpose of hometown-visiting by relatives that apply to your family (multiple choice). | ||

| 9.1. Family/relative gatherings or reunions | ||

| 9.2. Supporting household chores | ||

| 9.3. Supporting farm work, yard work (gardening), | ||

| 9.4. Enjoying outdoor leisure activities (e.g., walking, fishing) | ||

| 9.5. Engaging in individual social activities/events | ||

| 9.6. Visiting gravesites | ||

| Frequency of Daily Shopping | 10. Providing Daily Essentials Shopping | |

| Frequency of Agricultural Work | 11. Providing Yard Work 12. Providing Farmland Cultivation, including Planting in Pots, Gardening, Home Vegetable Gardening | |

| Frequency of Outdoor Leisure Activities | 13. Outdoor Leisure Activities Frequency of engaging in Outdoor Leisure Activities during Hometown Visits, including: Barbecue (BBQ) Foraging for Wild Plants (Mountain Vegetables), Fishing, Hiking, Walking/Strolling, Carpentry Work, Agricultural Work | |

| Frequency of Personal Social Activities | 14. Social Interactions and Leisure Activities in the Community during hometown visits, Including: Spending Time with Friends (e.g., Teatime) Engaging in Hobbies Going Out | |

| Frequency of Community Activities | 15. Participating on Behalf of Residents with Community Activities, including: Community Lawn Mowing Community Clean-Up (Trash Collection) Local Festival |

| Survey Questions | Survey Items | Details and Proportion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Location of Resident Households by Settlements N = 155 | Settlement Name | Quantity | Proportion | ||

| Ōhinata | 39 | 25.2% | |||

| Iwado | 24 | 15.5% | |||

| Ozawa | 23 | 14.8% | |||

| Mukuruma | 18 | 11.6% | |||

| Ōshiozawa | 17 | 11.0% | |||

| Hisawa | 9 | 5.8% | |||

| Ōnita | 7 | 4.5% | |||

| Hazawa | 6 | 3.9% | |||

| Tozawa | 6 | 3.9% | |||

| Hoshio | 4 | 2.6% | |||

| Chihara | 1 | 0.6% | |||

| Not Provided | 1 | 0.6% | |||

| 2. Household Composition N = 150 | Categorizations of Household Composition | Details of Demographic Characteristics | Quantity | Proportion | |

| Single-Senior Household N = 49 (33.8%) | Gender | ||||

| Male | 12 | 75.5% | |||

| Female | 37 | 24.5% | |||

| Age | |||||

| Early Senior (65–79) | 13 | 26.5% | |||

| Later Senior (≥80) | 36 | 73.5% | |||

| Multi-Senior Households N = 66 (42.1%) | Same-Generation Senior Household | 50 | 82.0% | ||

| Intergeneration Senior Household | 11 | 18.0% | |||

| Intergenerational Households N = 35 (24.1%) | Two-Generation Household (Early Senior) | 20 | 57.1% | ||

| Two-Generation Household (Later Senior) | 12 | 34.3% | |||

| Two-Generation Household (Junior Only) | 3 | 8.6% | |||

| 3. Health Conditions 2 N = 146 | Categorizations of Health Conditions 2 | Options (Multiple-Choice Questions) 1 | Quantity | Selection Rate 1 | |

| Healthy Households N = 49 (33.6%) | 3.1. All Family Members are In Good Health | 49 | 33.6% | ||

| Self-Reliant Medical Care Households N = 78 (53.4%) | 3.2. Require Regular Medical Attention | 93 | 64.0% | ||

| Number of Support-Reliant Households N = 19 (13.0%) | Support-Needed Households N = 10 (6.2%) | 3.3. Utilize In-Home Care Services (for basic assistance) | 5 | 2.5% | |

| 3.4. Attend Adult Day Care | 11 | 7.5% | |||

| Care-Needed Households N = 9 (6.8%) | 3.5. Receive Home Visit Medical Services | 1 | 0.8% | ||

| 3.6. Require Long-Term Care Assistance | 8 | 5.4% | |||

| 4. Shopping Medical-care Methods 3 N = 147 | Categorizations of Shopping Medical-Care Methods 3 | Options (Multiple-Choice Questions) 1 | Quantity | Selection Rate 1 | |

| Self-help N = 77 (53.0%) | 4.1. Shop (Seek Medical Care) Independently with Cohabiting Family | 121 | 82.3% | ||

| Mutual aid N = 12 (8.2%) | 4.2. Shop (Seek Medical Care) with Hometown Visiting Relatives | 27 | 18.3% | ||

| 4.3. Shop (Seek Medical Care) with Community Residents | 15 | 10.2% | |||

| 4.4. Have Shopping Performed on Their Behalf by Hometown Visiting Relatives | 18 | 11.6% | |||

| 4.5. Have Shopping Performed on Their Behalf by Community Residents | 3 | 2.0% | |||

| Combined support N = 58 (38.8%) | 4.6. Utilize Community Mobile Vending for Shopping | 15 | 9.5% | ||

| 4.7. Utilize Home Delivery Services (e.g., Co-op) for Shopping | 36 | 24.5% | |||

| Survey Questions | Survey Items | Quantity (Proportion) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family A 3 | Family B 3 | |||||

| 5. Location of Visit Relatives | Wide range division | Prefecture/City/Town | N = 147 | N = 118 | ||

| Seimou area 1 | Total | N = 112 | 76.2% | N = 75 | 63.6% | |

| Tomioka City | 32 | 28.6% | 29 | 38.7% | ||

| Takasaki City | 32 | 28.6% | 22 | 29.3% | ||

| Nanmoku Village | 25 | 22.3% | 14 | 18.7% | ||

| Shimonita Town | 12 | 10.7% | 4 | 5.3% | ||

| Others | 11 | 9.8% | 6 | 8.0% | ||

| Other areas in Gunma Prefecture | Total | N = 17 | 11.6% | N = 13 | 11.0% | |

| Maebashi City | 7 | 41.2% | 6 | 46.2% | ||

| Others | 10 | 58.8% | 7 | 53.8% | ||

| Kanto Region 2 (Kanto Region exclude Gunma Prefecture) | Total | N = 15 | 10.2% | N = 27 | 22.9% | |

| Tokyo | 4 | 26.7% | 12 | 44.5% | ||

| Saitama | 4 | 26.7% | 9 | 33.3% | ||

| Chiba | 7 | 46.6% | 1 | 3.7% | ||

| Kanagawa | - | - | 5 | 18.5% | ||

| Other Regions | Others | N = 3 | 2.0% | N = 3 | 2.5% | |

| 6. Age | Total | N = 152 | N = 121 | |||

| Under 50 | 47 | 31.0% | 46 | 37.5% | ||

| 50~64 | 61 | 40.1% | 35 | 29.1% | ||

| 65~74 | 18 | 11.8% | 20 | 16.7% | ||

| Over 75 | 26 | 17.1% | 20 | 16.7% | ||

| 7. Frequency of Hometown Visit 5 | Total | N = 151 | N = 119 | |||

| More than once a week | 50 | 33.1% | 17 | 14.3% | ||

| More than once a month | 64 | 42.4% | 46 | 38.7% | ||

| More than once a year | 37 | 24.5% | 56 | 47.0% | ||

| Less than once a year (excluded from total) | 4 | - | 3 | - | ||

| 8. Relationship of Hometown-visiting Relatives to Residents | Total | N = 153 | N = 123 | |||

| Parent | 14 | 9.1% | 2 | 1.6% | ||

| Child | 110 | 71.9% | 84 | 68.3% | ||

| Sibling | 24 | 15.7% | 30 | 24.4% | ||

| Others | 5 | 3.3% | 7 | 5.7% | ||

| 9. Main Purpose of Hometown-Visiting | Multiple-choice Question | Selection Rate 4 | Selection Rate 4 | |||

| 9.1. Family/relative gatherings or reunions | 127 | 83.0% | 104 | 83.2% | ||

| 9.2. Supporting household chores | 27 | 17.6% | 20 | 16.0% | ||

| 9.3. Supporting farm work, yard work (gardening, planting in pots) | 14 | 9.2% | 11 | 8.8% | ||

| 9.4. Enjoying outdoor leisure activities (e.g., walking, fishing) | 25 | 16.3% | 22 | 17.6% | ||

| 9.5. Engaging in personal social activities/events (e.g., teatime with friends, engaging in hobbies) | 20 | 13.1% | 10 | 8.0% | ||

| 9.6. Visiting gravesites | 94 | 61.4% | 64 | 51.2% | ||

| Survey Questions On Questionnaire | Details | Family A Most Frequent | Family B Second-Most Frequent | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantity | Proportion | Quantity | Proportion | ||

| 10. Daily Essentials Shopping | Total | N = 147 | N = 118 | ||

| More than once a week | 21 | 14.3% | 8 | 6.8% | |

| More than once a month | 16 | 10.9% | 11 | 9.3% | |

| Several times a year | 21 | 14.3% | 22 | 18.6% | |

| Almost never | 89 | 60.5% | 77 | 65.3% | |

| 11. Yard Work around house | Total | 147 | N = 116 | ||

| More than once a month | 22 | 15.0% | 4 | 3.4% | |

| Several times a year | 11 | 7.5% | 11 | 9.5% | |

| Almost never | 114 | 77.5% | 101 | 87.1% | |

| 12. Farm Work | Total | N = 149 | N = 117 | ||

| More than once a month | 16 | 10.7% | 5 | 4.2% | |

| Several times a year | 19 | 12.8% | 12 | 10.3% | |

| Almost never | 114 | 76.5% | 100 | 85.5% | |

| 13. Outdoor Leisure Activities | Total | N = 145 | N = 115 | ||

| More than once a month | 19 | 13.1% | 7 | 6.1% | |

| Several times a year | 67 | 46.2% | 59 | 51.3% | |

| Almost never | 59 | 40.7% | 49 | 42.6% | |

| 14. Personal Social Activities | Total | N = 148 | N = 121 | ||

| More than once a week | 14 | 9.4% | 7 | 5.8% | |

| More than once a month | 7 | 4.7% | 8 | 6.6% | |

| Several times a year | 39 | 26.4% | 21 | 17.4% | |

| Almost never | 88 | 59.5% | 85 | 70.2% | |

| 15. Community Activities | Total | N = 148 | N = 119 | ||

| Participate All | 19 | 12.8% | 8 | 6.7% | |

| Participate Part | 30 | 20.3% | 21 | 17.6% | |

| Almost never | 99 | 66.9% | 90 | 75.6% | |

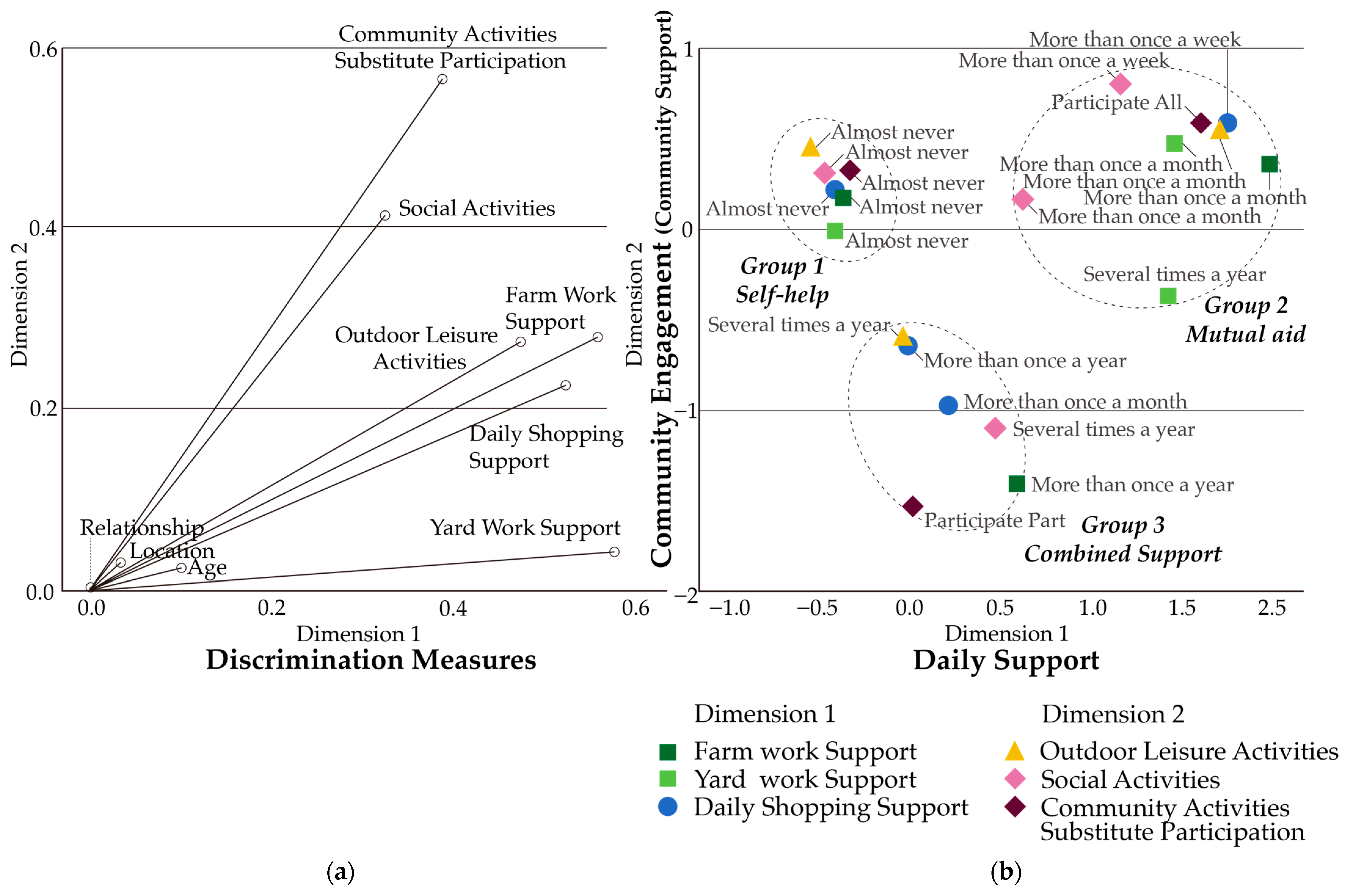

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Accounted For | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Eigenvalue) | Inertia | Variance Explained (%) | ||

| 1 | 0.778 | 2.845 | 0.474 | 61.27% |

| 2 | 0.532 | 1.797 | 0.300 | 38.73% |

| Total | 4.643 | 0.774 | 100.0% | |

| Mean | 0.683 | 2.321 | 0.387 | |

| Variables | Dimension 1 Daily Support | Dimension 2 Community Engagement | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10A. Daily Shopping Support | 0.523 | 0.225 | 0.473 |

| 11A. Yard Work Support | 0.577 | 0.042 | 0.309 |

| 12A. Farm Work Support | 0.559 | 0.279 | 0.419 |

| 13A. Outdoor Leisure Activities | 0.474 | 0.274 | 0.374 |

| 14A. Social Activities | 0.324 | 0.413 | 0.369 |

| 15A. Participation in Community Activities as a Substitute | 0.387 | 0.564 | 0.476 |

| Age (Supplementary) | 0.099 | 0.023 | 0.061 |

| Relationship (Supplementary) | 0.023 | 0.008 | 0.015 |

| Geographic Location (Supplementary) | 0.031 | 0.028 | 0.030 |

| Active Total | 2.845 | 1.797 | 2.321 |

| Hometown Visit Frequency | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than once a month | ||||||||

| Intercept | 0.366 | 0.247 | 2.189 | 1 | 0.139 | - | - | - |

| Dimension 1 | −1.001 | 0.328 | 23.843 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.202 | 0.106 | 0.384 |

| Dimension 2 | −0.909 | 0.271 | 11.241 | 1 | 0.001 | 0.403 | 0.237 | 0.686 |

| More than once a year | ||||||||

| Intercept | −1.546 | 0.753 | 4.222 | 1 | 0.040 | - | - | - |

| Dimension 1 | −4.133 | 1.167 | 12.548 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.158 |

| Dimension 2 | −0.838 | 0.455 | 3.395 | 1 | 0.065 | 0.433 | 0.177 | 1.055 |

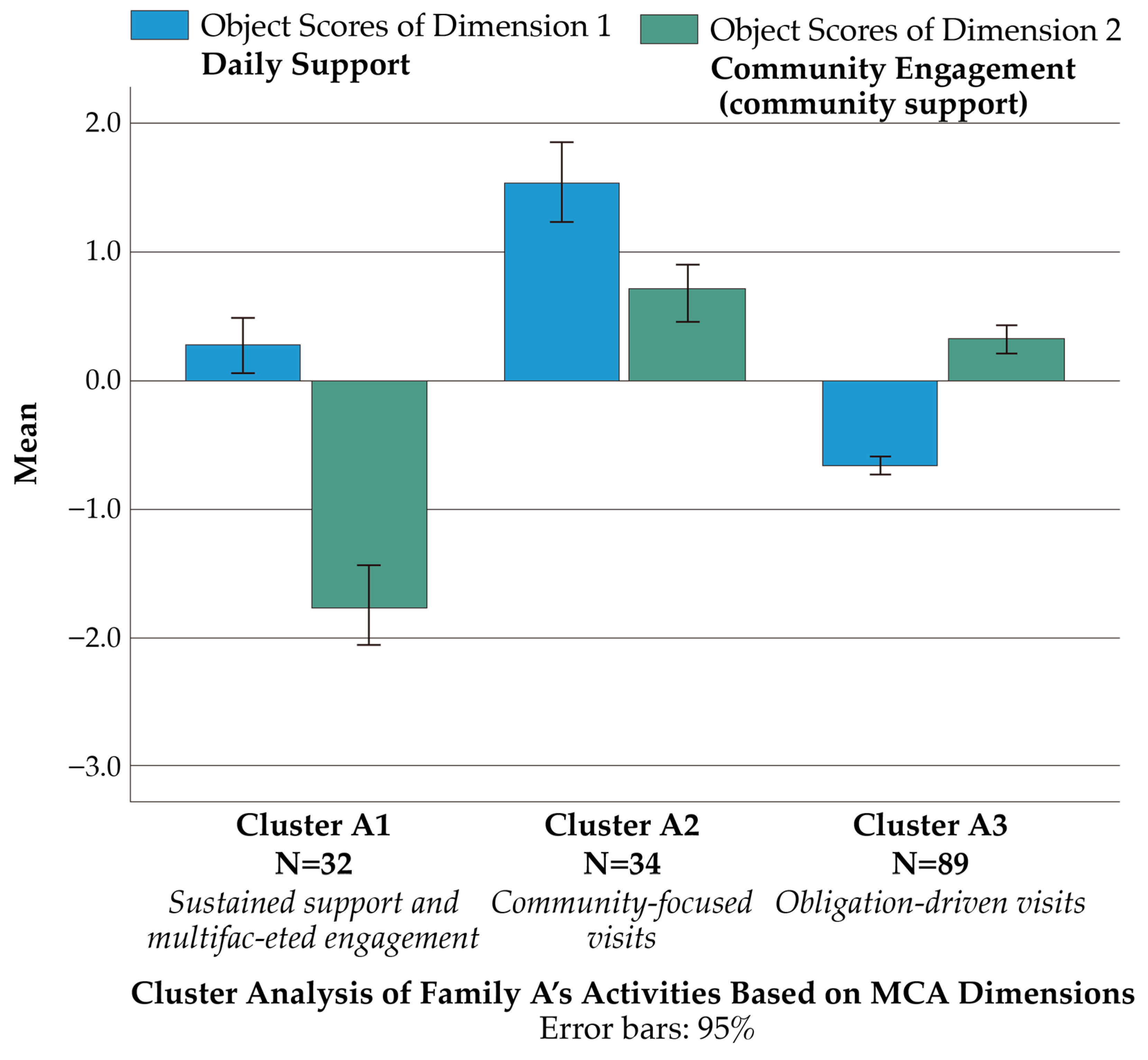

| Number of Clusters | Explained Variance of Dimension | Distribution of Cases | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | Cluster A1 | Cluster A2 | Cluster A3 | Cluster A4 | |||||

| 2 | 0.776 | 0.024 | 116 | 74.8% | 39 | 25.2% | ||||

| 3 | 0.622 | 0.498 | 32 | 20.6% | 34 | 21.9% | 89 | 57.4% | ||

| 4 | 0.780 | 0.776 | 27 | 17.4% | 12 | 7.7% | 30 | 19.4% | 86 | 55.5% |

| Variables | Percentages in Clusters 1 | Chi-Square Tests (p-Value) 2 | Characteristic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster A1 | Cluster A2 | Cluster A3 | |||||||

| Age | <50 years | 8 | 25.8% | 3 | 9.1% | 36 | 40.9% | <0.05 | Cluster A3: predominantly younger; Cluster A2: predominantly older; Cluster A1: mix |

| ≥50 years | 23 | 74.2% | 30 | 90.9% | 52 | 59.1% | |||

| Relationship | Parent | 5 | 16.1% | 3 | 9.1% | 6 | 6.7% | - | Predominantly children in all clusters, with higher sibling representation in Cluster A3 |

| Child | 22 | 71.0% | 26 | 78.8% | 62 | 69.7% | |||

| Sibling | 3 | 9.7% | 3 | 9.1% | 18 | 20.2% | |||

| Relatives from Seimou area | 24 | 77.4% | 25 | 86.2% | 63 | 72.4% | - | Seimou-based across all clusters | |

| Hometown visits (weekly) | 8 | 25.0% | 29 | 87.9% | 13 | 15.1% | <0.001 | Cluster A2: high frequent visits | |

| Hometown visits (>monthly) | 30 | 93.7% | 33 | 100% | 38 | 44.2% | Cluster A1: frequent visits | ||

| Hometown visits (yearly only) | 2 | 6.3% | - | - | 25 | 40.7% | Cluster A3: high rate of visits (both annual and less frequent) | ||

| Chore support 3 | 8 | 25.0% | 12 | 35.3% | 7 | 7.9% | <0.001 | Clusters A1 and A2: low levels of chore support; Cluster A3: lowest level of chore support | |

| Grave visit 3 | 20 | 62.5% | 21 | 61.8% | 53 | 59.6% | - | Common across all clusters | |

| Outdoor leisure activities (weekly) | 2 | 6.7% | 15 | 50.0% | 2 | 2.4% | <0.001 | Cluster A2: high level of weekly outdoor leisure activities | |

| Outdoor leisure activities 3 | 26 | 86.7% | 25 | 83.3% | 35 | 41.2% | Cluster A3: least amount of engagement | ||

| Shopping support (>monthly) | 11 | 37.9% | 20 | 58.8% | 6 | 7.2% | <0.001 | Cluster A2: frequent shopping support; Cluster 1: lower level | |

| Shopping support (yearly only) | 9 | 31.0% | 12 | 35.3% | 68 | 81.0% | Cluster A3: infrequent shopping support | ||

| Yard work support (weekly) | 3 | 11.1% | 18 | 54.5% | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster A2: high-level support; Cluster A1: low-level support | |

| Yard work support 3 | 8 | 29.6% | 24 | 72.7% | 1 | 1.2% | Cluster A3: infrequent yard work support | ||

| Farm work support (weekly) | 2 | 6.7% | 14 | 42.4% | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster A2: high-level support; Cluster A1: low-level support | |

| Farm work support 3 | 16 | 53.3% | 17 | 51.5% | 2 | 2.3% | Cluster A3: infrequent farm work support | ||

| High-frequency social activities (>monthly) | 3 | 10.0% | 14 | 43.8% | 4 | 4.7% | <0.001 | Cluster A2: high level of social activity | |

| Social activities 3 | 23 | 76.7% | 23 | 71.9% | 14 | 16.3% | Clusters A1 and A2 high social participation; Cluster A3: lower participation | ||

| Community activities 3 | 22 | 73.3% | 18 | 56.2% | 9 | 10.5% | <0.001 | Cluster A1: high engagement; Cluster A2: moderate engagement; Cluster A3: lower engagement | |

| Shopping and medical care support needed by residents 4 | 17 | 54.8% | 22 | 78.6% | 27 | 31.0% | <0.001 | Cluster A2: higher support needs; Cluster A3: high unmet support needs | |

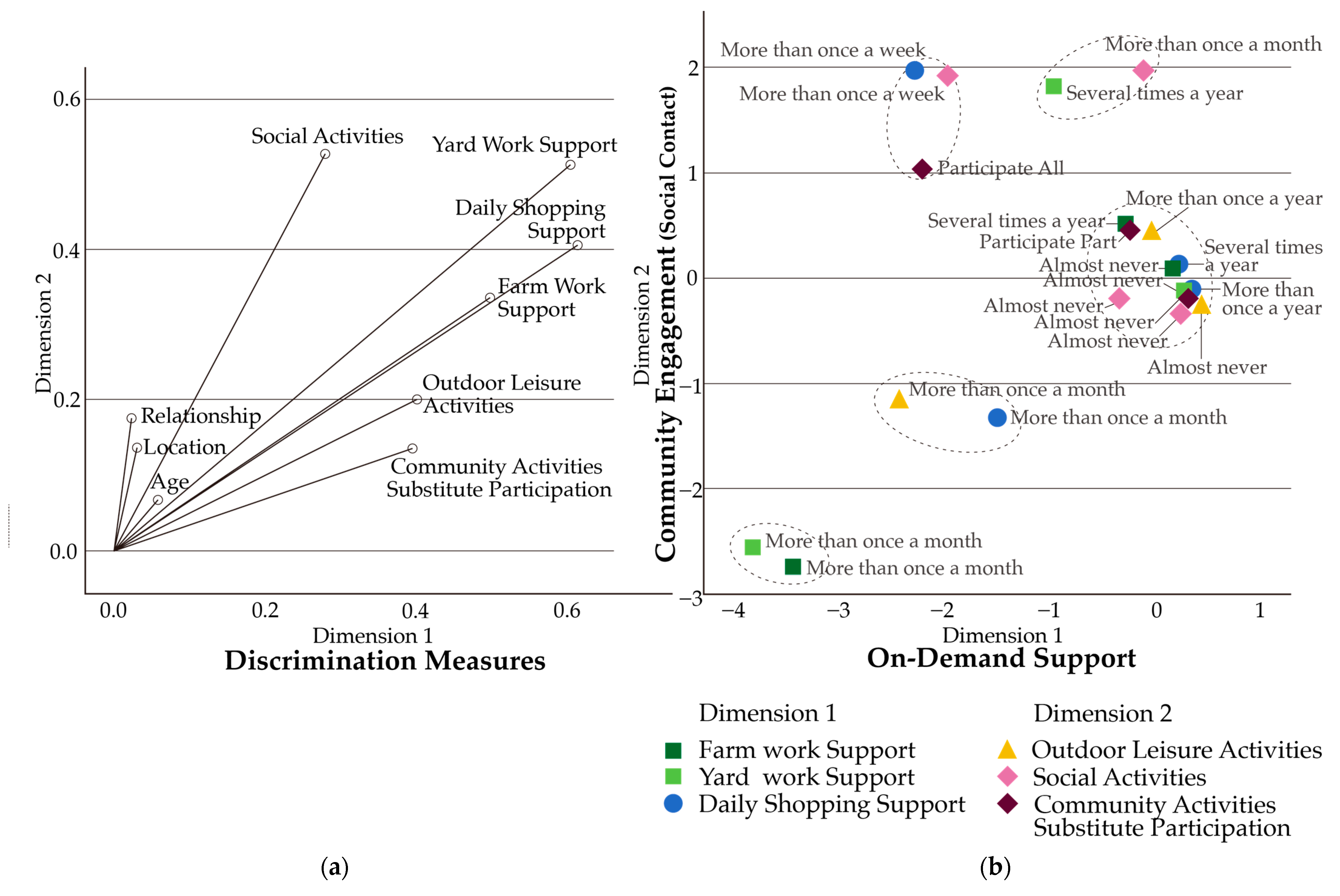

| Dimension | Cronbach’s Alpha | Variance Accounted For | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (Eigenvalue) | Inertia | Variance Explained (%) | ||

| 1 | 0.770 | 2.793 | 0.466 | 56.9% |

| 2 | 0.633 | 2.115 | 0.353 | 43.1% |

| Total | 4.909 | 0.818 | 100.0% | |

| Mean | 0.711 | 2.454 | 0.409 | |

| Variables | Dimension 1 On-Demand Support | Dimension 2 Social Contact | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10B. Daily Shopping Support | 0.614 | 0.405 | 0.510 |

| 11B. Yard Work Support | 0.605 | 0.513 | 0.559 |

| 12B. Farm Work Support | 0.499 | 0.334 | 0.417 |

| 13B. Outdoor Leisure Activities | 0.401 | 0.200 | 0.301 |

| 14B. Social Activities | 0.279 | 0.527 | 0.403 |

| 15B. Participation in Community Activities as a Substitute | 0.395 | 0.135 | 0.265 |

| Age (Supplementary) | 0.058 | 0.067 | 0.062 |

| Relationship (Supplementary) | 0.022 | 0.175 | 0.099 |

| Geographic Location (Supplementary) | 0.030 | 0.136 | 0.083 |

| Active Total | 2.793 | 2.115 | 2.454 |

| Hometown Visit Frequency | B | Std. Error | Wald | df | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI for Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than once a month | ||||||||

| Intercept | 1.619 | 0.391 | 17.13 | 1 | 0.000 | - | - | - |

| Dimension 1 | 1.066 | 0.303 | 12.424 | 1 | 0.000 | 2.905 | 1.605 | 5.255 |

| Dimension 2 | −0.287 | 0.21 | 1.866 | 1 | 0.172 | 0.75 | 0.497 | 1.133 |

| More than once a year | ||||||||

| Intercept | −1.546 | 0.753 | 4.222 | 1 | 0.040 | - | - | - |

| Dimension 1 | −4.133 | 1.167 | 12.548 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.002 | 0.158 |

| Dimension 2 | −0.838 | 0.455 | 3.395 | 1 | 0.065 | 0.433 | 0.177 | 1.055 |

| Number of Clusters | Schwarz’s Bayesian Criterion (BIC) | BIC Change | Ratio of BIC Changes | Ratio of Distance Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 430.669 | |||

| 2 | 267.024 | −163.645 | 1.000 | 2.094 |

| 3 | 203.842 | −63.183 | 0.386 | 3.526 |

| 4 | 206.468 | 2.627 | −0.016 | 1.092 |

| 5 | 211.296 | 4.827 | −0.029 | 1.750 |

| 6 | 226.340 | 15.044 | −0.092 | 1.623 |

| 7 | 246.615 | 20.275 | −0.124 | 1.205 |

| 8 | 268.318 | 21.703 | −0.133 | 1.214 |

| 9 | 291.251 | 22.933 | −0.140 | 1.286 |

| 10 | 315.461 | 24.210 | −0.148 | 1.253 |

| 11 | 340.574 | 25.113 | −0.153 | 1.163 |

| 12 | 366.185 | 25.612 | −0.157 | 1.298 |

| 13 | 392.500 | 26.315 | −0.161 | 1.363 |

| 14 | 419.443 | 26.943 | −0.165 | 1.053 |

| 15 | 446.473 | 27.030 | −0.165 | 1.025 |

| Cluster | N | Percentage of Combined | Object Score Dimension 1 (On-Demand Support) | Object Score Dimension 2 (Social Contact) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std. | Mean | Std. | |||

| Cluster B1 | 17 | 11.6% | −1.475 | 1.720 | 0.328 | 2.021 |

| Cluster B2 | 46 | 38.7% | 0.062 | 0.811 | 0.029 | 1.294 |

| Cluster B3 | 56 | 47.1% | 0.368 | 0.353 | −0.114 | 0.469 |

| Combined | 119 | 100% | −0.013 | 1.044 | 0.004 | 1.148 |

| Variables | Percentages in Clusters 1 | Chi-Square Tests (p-Value) 2 | Characteristic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cluster B1 | Cluster B2 | Cluster B3 | |||||||

| Age | <50 years | 10 | 58.8% | 27 | 65.9% | 40 | 71.4% | - | B3: predominantly younger; Cluster B1 and B2: mix |

| ≥50 years | 7 | 41.2% | 14 | 34.1% | 16 | 28.6% | |||

| Relationship | Parent | 1 | 5.9% | 1 | 2.2% | - | - | - | Predominantly children and a small proportion of siblings in all clusters |

| Child | 12 | 70.6% | 31 | 68.9% | 39 | 70.9% | |||

| Sibling | 3 | 17.6% | 10 | 22.0% | 14 | 25.5% | |||

| Relatives from Seimou area | 15 | 88.2% | 35 | 81.4% | 25 | 45.5% | <0.001 | Cluster B1 and B2: Seimou-based | |

| Relatives from Kanto region | 1 | 5.9% | 4 | 9.3% | 19 | 34.5% | Cluster B3: mix | ||

| Hometown visits (weekly) | 17 | 100% | - | - | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster B1: highly frequent visits Cluster B2: frequent visits; Cluster B3: infrequent visits | |

| Hometown visits (monthly) | - | - | 46 | 100% | - | - | |||

| Hometown visits (yearly) | - | - | - | - | 56 | 100% | |||

| Chore support 3 | 5 | 29.4% | 7 | 15.2% | 7 | 12.5% | - | Low-level chore support across all clusters | |

| Grave visit 3 | 6 | 35.3% | 24 | 52.2% | 30 | 53.6% | - | Low levels in Cluster B1 | |

| Outdoor leisure activities (weekly) | 4 | 25.0% | 2 | 4.8% | 1 | 1.9% | <0.05 | Cluster B1: high levels of engagement in outdoor leisure activities Cluster B2 and B3: moderate levels of engagement | |

| Outdoor leisure activities 3 | 12 | 75.0% | 21 | 50.0% | 31 | 59.6% | |||

| Shopping support (>monthly) | 9 | 52.9% | 9 | 22.0% | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster B1: frequent shopping support; Cluster B2: lower-level shopping support; Cluster B3: infrequent shopping support | |

| Shopping support (yearly only) | 2 | 11.8% | 8 | 19.5% | 11 | 20.4% | |||

| Yard work support (weekly) | 3 | 17.6% | 1 | 2.5% | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster B1: moderate-level support; Cluster B2 and B3: infrequent yard work support | |

| Yard work support 3 | 8 | 47.1% | 4 | 10.0% | 2 | 3.6% | |||

| Farm work support (weekly) | 3 | 17.6% | 1 | 2.4% | 1 | 1.9% | <0.05 | Cluster B1: moderate level support; Cluster B2 and B3: infrequent farm work support | |

| Farm work support 3 | 7 | 41.2% | 3 | 7.3% | 2 | 11.1% | |||

| High-frequency social activities (>monthly) | 4 | 23.5% | 3 | 6.7% | - | - | <0.001 | Cluster B1: high level of social activity engagement; | |

| Social activities 3 | 12 | 71.6% | 12 | 26.7% | 12 | 21.8% | Clusters B2 and B3: lower engagement | ||

| Community activities 3 | 8 | 53.7% | 10 | 23.8% | 10 | 17.9% | <0.001 | Cluster B1: moderate levels of engagement; Cluster B2 and B3: lower engagement | |

| Shopping and medical care support needed by residents 4 | 9 | 46.2% | 17 | 69.0% | 19 | 66.7% | - | Cluster B1: lower support needed; Cluster B2 and B3: higher support needed | |

References

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.M.; Lichter, D.T. Rural depopulation: Growth and decline processes over the past century. Rural Sociol. 2019, 84, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobao, L. A Sociology of the Periphery Versus a Peripheral Sociology: Rural Sociology and the Dimension of Space 1. Rural Sociol. 1996, 61, 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naumann, M.; Reichert-Schick, A. Infrastrukturelle Peripherisierung: Das Beispiel Uecker-Randow (Deutschland). Plan. Rev. 2012, 48, 27–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenza-Peral, A.; Pérez-Ibarra, I.; Breceda, A.; Martínez-Fernández, J.; Giménez, A. Can local policy options reverse the decline process of small and marginalized rural areas influenced by global change? Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 127, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Urban–rural transformation in relation to cultivated land conversion in China: Implications for optimizing land use and balanced regional development. Land Use Policy 2015, 47, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camarero, L.; Oliva, J. Thinking in rural gap: Mobility and social inequalities. Palgrave Commun. 2019, 5, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricardo Grau, H.; Mitchell Aide, T. Are Rural–Urban Migration and Sustainable Development Compatible in Mountain Systems? Mt. Res. Dev. 2007, 27, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizzi, F.T.; Antunes, I.M.H.R.; Reis, A.P.M.; Giano, S.I.; Masini, N.; Muceku, Y.; Pescatore, E.; Potenza, M.R.; Corbalán Andreu, C.; Sannazzaro, A.; et al. From Settlement Abandonment to Valorisation and Enjoyment Strategies: Insights through EU (Portuguese, Italian) and Non-EU (Albanian) ‘Ghost Towns’. Heritage 2024, 7, 3867–3901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Westlund, H.; Liu, Y. Why some rural areas decline while some others not: An overview of rural evolution in the world. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 68, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Chapter 2: International Trends in Aging, (2) Japan Has the Highest Aging Rate in the World. In Annual Report on the Aging Society; Reiwa 6 Edition; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2022; Available online: https://www8.cao.go.jp/kourei/whitepaper/w-2024/zenbun/06pdf_index.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Regional Revitalization Group, Deprived Areas Countermeasures Office. Current Status of Countermeasures for Deprived Areas. 2024. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/jichi_gyousei/c-gyousei/2001/kaso/kasomain8.htm (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Van Houtven, C.H.; Norton, E.C. Informal care and health care use of older adults. J. Health Econ. 2004, 23, 1159–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogawa, N. What Is Regional Revitalization? The Duality of Regional Revitalization (地域活性化とは何か: 地域活性化の二面性). J. Urban Manag. Local Gov. Res. 2013, 28, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, N. Regional Revitalization and Local Creation. Onomichi City Univ. Econ. Inf. Bull. 2016, 16, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Basic Policy for Town, People, and Job Creation 2021 (まち・ひと・しごと創生基本方針 2021). Available online: https://www.chisou.go.jp/sousei/info/index.html#an20 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Kameda, S. Issues in Hilly and Mountainous Areas: Focusing Mainly on the Direct Payment System (中山間地域の諸問題, 主に直接支払制度をめぐって). Ref. Jpn. Natl. Diet Libr. 2009, 59, 5–26. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Japan, Relationship Population. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/kankeijinkou/about/index.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ashida, T. One Case of How People Come to Their Rural Home Village and Assist Farming There: A Case Study of a Kitakanto Rural Village. J. Rural Plan. 2006, 25, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gieling, J.; Vermeij, L.; Haartsen, T. Beyond the Local-Newcomer Divide: Village Attachment in the Era of Mobilities. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 55, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, T.; Hugo, G. Introduction: Moving beyond the urban-rural dichotomy. In New Forms of Urbanization, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pallagst, K.; Wiechmann, T.; Martinez-Fernandez, C. (Eds.) Shrinking Cities: International Perspectives and Policy Implications, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, Y. Shrinkage of regional cities in Japan: Analysis of changes in densely inhabited districts. Cities 2021, 113, 103168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.J.A. Making sense of counterurbanization. J. Rural Stud. 2004, 20, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janc, K.; Dołzbłasz, S.; Raczyk, A.; Skrzypczyński, R. Winding Pathways to Rural Regeneration: Exploring Challenges and Success Factors for Three Types of Rural Changemakers in the Context of Knowledge Transfer and Networks. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, T. Urbanization, suburbanization, counterurbanization and reurbanization. In Handbook of Urban Studies; Paddison, R., Ed.; SAGE Publications Ltd.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2001; Volume 160, pp. 143–161. [Google Scholar]

- Klien, S. “The young, the stupid, and the outsiders”: Urban migrants as heterotopic selves in post-growth Japan. Asian Anthropol. 2022, 21, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halfacree, K. From dropping out to leading on? British counter-cultural back-to-the-land in a changing rurality. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2006, 30, 309–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.; O’Reilly, K. Migration and the Search for a Better Way of Life: A Critical Exploration of Lifestyle Migration. Sociol. Rev. 2009, 57, 608–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odagiri, T.; Tsutsui, K. Creating New Agricultural and Mountain Villages with Migrants: Series Rural Return Vol. 3–Past, Present, and Future of Rural Return (シリーズ田園回帰, 田園回帰の過去・現在・未来, 移住者と創る新しい農山村); Rural Culture Association Japan (Nōbunkyō): Tokyo, Japan, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hattori, K.; Kaido, K.; Matsuyuki, M. The development of urban shrinkage discourse and policy response in Japan. Cities 2017, 69, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan. 2020. Available online: https://www.mlit.go.jp/statistics/file000004.html (accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. Questionnaire Survey Results on Migrants to Depopulated Areas: The 2nd “Denenkaiki” Research Meeting, FY2017. 2017. Available online: https://www.soumu.go.jp/main_sosiki/jichi_gyousei/c-gyousei/2001/kaso/02gyosei10_04000047.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Luzi, C. The gap between administration and migrants: Terminologies and experiences of urban-rural migration in Japan. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 113, 103500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N.Y. Return to the countryside: An ethnographic study of young urbanites in Japan’s shrinking regions. J. Rural Stud. 2024, 107, 103254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollet, S.; Qu, M. Revitalising rural areas through counterurbanisation: Community-oriented policies for the settlement of urban newcomers. Habitat Int. 2024, 145, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, Y.; Kubota, H.; Shigeto, S.; Yoshida, T.; Yamagata, Y. Diverse values of urban-to-rural migration: A case study of Hokuto City, Japan. J. Rural Stud. 2021, 87, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics Division, Bureau of General Affairs, Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Estimated Population of Tokyo: Monthly Data. Available online: https://www.toukei.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/jsuikei/js-index.htm (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. The Shape of Municipalities Seen Through Statistics. Available online: https://www.stat.go.jp/data/s-sugata/naiyou.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Cyrek, M.; Cyrek, P. Living standards in rural areas of European Union countries. J. Rural Stud. 2025, 113, 103507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillman, D.A.; Tremblay, K.R. The Quality of Life in Rural America. ANNALS Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1977, 429, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilley, L.; Gkartzios, M.; Odagiri, T. Developing counterurbanisation: Making sense of rural mobility and governance in Japan. Habitat Int. 2022, 125, 102595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcus, H.R.; Brunn, S.D. Place elasticity: Exploring a new conceptualization of mobility and place attachment in rural America. Geogr. Ann. Ser. B Hum. Geogr. 2010, 92, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloke, P.; Milbourne, P.; Widdowfield, R. The complex mobilities of homeless people in rural England. Geoforum 2003, 34, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milbourne, P.; Kitchen, L. Rural mobilities: Connecting movement and fixity in rural places. J. Rural Stud. 2014, 34, 326–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, K.; Sakurai, Y. A study on the characteristic of Private Subdivision Dwellers in the suburb of Fukui city from the view of the connection to their hometown and the residence career A basic study on the continuity of habitation in the suburb of local city. J. City Plan. Inst. Jpn. 2005, 40, 529–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office, Government of Japan. Fiscal Year 2008 Edition: Regional Economy, Chapter 2, Section 1, 1. In Population Movements by Regional Block; Cabinet Office: Tokyo, Japan, 2008; Available online: https://www5.cao.go.jp/j-j/cr/cr08/chr08_2-1-1.html (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, Municipal Administration Division. National Overview of Municipalities: Reiwa 5 Edition; Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: Tokyo, Japan, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shimogo Town Office. Shimogo Town Official Website. Available online: https://www.town.shimogo.fukushima.jp/index.html (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Statistics Bureau, Government of Japan. Population Census: Main Results by Prefecture, Municipality, 2005–2020. Available online: https://www.e-stat.go.jp/stat-search/files?page=1&layout=datalist&toukei=00200521&tstat=000001049104&cycle=0&tclass1=000001049105&tclass2val=0 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Nanmoku Village Office. Nanmoku Village Official Website. Available online: https://nanmoku.ne.jp (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Wang, W.; Saito, Y. Aging in Place in a Depopulated, Mountainous Area: The Role of Hometown-Visiting Family Members in Shimogo, Japan. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rioux, L. The well-being of aging people living in their own homes. J. Environ. Psychol. 2005, 25, 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugiyama, M.; Ikuta, E.; Okazaki, K.; Takai, I.; Mori, K. Activity Environment Based on Lifestyle Types of New Town Residents: Activity Environment for Prevention of Locomotive Syndrome in the Elderly Part 1. J. Archit. Plan. 2015, 80, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, H.; Valentin, D. Multiple correspondence analysis. Encycl. Meas. Stat. 2007, 2, 651–657. Available online: https://personal.utdallas.edu/~Herve/Abdi-MCA2007-pretty.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Hoffman, D.L.; De Leeuw, J. Interpreting multiple correspondence analysis as a multidimensional scaling method. Mark. Lett. 1992, 3, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lolle, H. Multiple Classification Analysis (MCA): Unfortunately, a nearly forgotten method for doing linear regression with categorical variables. In Symposium I Anvendt Statistik; Copenhagen Business School & Statistics: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2008; pp. 103–122. [Google Scholar]

- Fithian, W.; Josse, J. Multiple correspondence analysis and the multilogit bilinear model. J. Multivar. Anal. 2017, 157, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audigier, V.; Husson, F.; Josse, J. MIMCA: Multiple imputation for categorical variables with multiple correspondence analysis. Stat. Comput. 2017, 27, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frades, I.; Matthiesen, R. Overview on Techniques in Cluster Analysis. In Bioinformatics Methods in Clinical Research; Methods in Molecular Biology (MIMB); Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009; Volume 593, pp. 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satish, S.M.; Bharadhwaj, S. Information search behaviour among new car buyers: A two-step cluster analysis. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2010, 22, 5–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zou, M.; Li, B.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, X.; Ma, L.; Feng, S.; Liu, W. Two-step cluster analysis based on three-dimensional CT measurements of craniofacial structures in severe craniofacial microsomia. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2024, 99, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupton, R.C.; Allwood, J.M. Hybrid Sankey diagrams: Visual analysis of multidimensional data for understanding resource use. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 124, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vining, D.R.; Pallone, R. Migration between core and peripheral regions: A description and tentative explanation of the patterns in 22 countries. Geoforum 1982, 13, 339–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, G.L.H.; Sørensen, J.F.L. There’s more to the picture than meets the eye: Measuring tangible and intangible capital in two marginal communities in rural Denmark. J. Rural Stud. 2007, 23, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, M. Measures for the sustainability of depopulated and aging mountain villages. Sociol. Stud. 2017, 100, 83–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, S.; Yamashita, Y. New relationships between regional cities and depopulated areas. Annu. Rep. Jpn. Assoc. Urban Sociol. 1999, 17, 109–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, Y. Youth Employment Mobility and Residential Choice: Urban Orientation and Local Settlement (若者の就职移动と居住地选択―都会志向と地元定着―); Kokon Shoin: Tokyo, Japan, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Odagiri, T. Rural Innovation Theory and Supporters for Rural Regeneration. J. Rural Plan. Assoc. 2013, 32, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Shanin, T. The Nature and Logic of the Peasant Economy I: A Generalisation. J. Peasant Stud. 1973, 1, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creed, G.W. “Family Values” and Domestic Economies. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2000, 29, 329–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, E. ‘People are willing to fight to the end’. Romanticising the ‘moral’ in moral economies of irrigation. Crit. Anthropol. 2020, 40, 194–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, N.; Taylor, J. The modernising of the indigenous domestic moral economy: Kinship, accumulation and household composition. Asia Pac. J. Anthropol. 2003, 4, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, I. Consideration about the heir to the system of mutual aid in the fishing community. J. Rural Plan. Assoc. 2014, 33, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kusumoto, Y. Changing Rural Communities and Research Trends in the Architectural Institute of Japan. J. Rural Plan. Assoc. 1983, 2, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Takeguchi, Y.; Suzuki, S. Approaches to Settlement Support in an Era of Extreme Population Decline and Aging Society. Stud. Reg. Sci. 2021, 51, 15–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, E.B.; Lockstone-Binney, L.; Ibsen, B. Can the participation of civil society in policy networks mitigate against societal challenges in rural areas? J. Rural Stud. 2025, 113, 103495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, K. Sociological Analysis of Living Spaces Among Residents in Depopulated Areas: Analysis based on the Results of a Survey in the Tamagawa Area, Yamaguchi Prefecture; Faculty of Human-Environment Studies, Kyushu University: Fukuoka, Japan, 2024; Volume 13, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klien, S. Post-pandemic developments in lifestyle migration in Japan: From back-to-the-land to urbanrural? J. Rural Stud. 2025, 114, 103505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature | Counter-Urbanization and “Denenkaiki” | UIJ-Turn Migration | “Relationship Population” |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | The movement of populations from urban to rural areas, driven by lifestyle preferences, environmental concerns, and a desire for community-based living [24,26]. | A Japanese model categorizing internal migration: U-turn (return to hometown), I-turn (regional in-migration), and J-turn (migration to a nearby hometown) [33,34]. | Defined as individuals maintaining active ties with rural areas despite residing elsewhere, particularly in regard to out-migrated families in this study, as well as those who previously resided in a given area or have prior residence or professional connections [18]. |

| Characteristic | Voluntary direction of rural in-migration. | Policy-driven initiatives intended to address the issue of excessive population concentration in Tokyo. | A complement to the migration approach, highlighting non-residents. |

| Advantages | It highlights the appeal of rural lifestyles, e.g., self-sufficiency, a slower pace of life, and natural surroundings [30,33]. | It provides actionable strategies for internal migration; U-turn migration emphasizes the role of “Chien” ties (place attachment) in fostering long-term settlement and integration [20,35]. | It focuses on dynamic mobility and contributions beyond residency, such as informal care, cultural participation, and community engagement [18]. |

| Understanding in Japan | It has been incorporated into early rural revitalization efforts (e.g., “Denenkaiki”), promoting the appeal of rural living to attract urban populations [36]. | It has been widely adopted in Japan’s “Chihousousei” policies to mitigate urban over-concentration and revitalize regional areas [15,16]. | It is emerging as a critical concept in addressing aging and depopulation in mountainous areas, emphasizing the importance of non-resident engagement [18]. |

| Implications in sustaining depopulated rural areas | It focuses on idyllic rural living but lacks alignment with the realities of aging, isolation, and limited infrastructure in Japan’s mountainous rural area [20,37]. | It is dependent on attracting migrants, which is increasingly challenging given the decline in the national population and zero-sum competition among municipalities [38,39]. | It requires further exploration to quantify long-term impacts and integrate them into policies targeting depopulated mountainous areas. |

| Feature | Shimogo Fukushima Prefecture | Nanmoku Gunma Prefecture |

|---|---|---|

| Geography Context 1 | Depopulated municipality; located in the easternmost part of Aizu Area; bordering Tochigi; dispersed settlements; reliance on local areas. | Depopulated municipality; located within the Tokyo metropolitan sphere; geographically isolated; mountainous terrain; limited transportation. Surrounded by other depopulated municipalities. |

| Transportation and Accessibility 2 | Private railway connections to Tokyo and Aizu-Wakamatsu; 37 km from Shirakawa IC; 35 km from Aizu-Wakamatsu by car. | Approximately 150 km from Tokyo; accessible via Kan-etsu and Joshin-etsu Expressways (over 2.5 h, 135 km toll roads); up to 5 h away when traveling via national highways. |

| Population Dynamics 3 | Latest data based on local office and 2020 National Census | |

| Population: 4818 Number of households: 2110 Aging rate: 45.5% (8th within Fukushima) | Population: 1427 Number of households: 844 Aging rate: 67.83% (1st within Japan) | |

| Population (2015): 5800; aging rate: 40.1% Population (2010): 6461; aging rate: 37.1% Population (2005): 7053; aging rate: 34.3% | Population (2015): 1979; aging rate: 60.5% Population (2010): 2423; aging rate: 61.9% Population (2005): 2929; aging rate: 53.4% | |

| Economic Characteristics 4 | Traditional agriculture (e.g., rice, buckwheat, flowers, and vegetables), forestry, tourism (e.g., “Ouchi-juku”, “Yunokami Onsen”, etc.), and cultural events | The economy involves small-scale farming, local produce (e.g., flowers and konjac), and links to urban markets; specific local products for urban sales. |

| Cultural and Social Ties 5 | Strong cultural heritage and festivals; external engagement; reliance on familial networks for community cohesion; out-migrant support for local events. | Cultural ties are influenced by urban proximity; mountainous terrain leads to social isolation; out-migration is influenced by regional and metropolitan connections. |

| Category | Questionary in Nanmoku |

|---|---|

| Demographic information of resident | 1. Location in Nanmoku 2. Household composition 3. Health conditions 4. Shopping and medical care methods |

| Demographic information of out-migrated family | 5. Age 6. Relationship with residents 7. Location 8. Hometown visit frequency 9. The main purpose of a hometown visit |

| Support during visit | 10. Shopping 11. Yard work 12. Farm work |

| Leisure during visit | 13. Personal hobbies 14. Outdoor leisure |

| Community activities | 15. Community meetings (e.g., clean-up, festivals, etc.) |

| Stage | Method and Analysis | Rationale for Using the Method | Implications for This Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Overview | Questionary design, primarily including categorical and factual frequency questions Table A1 | To objectively capture actions: It allowed the use of categorized variables based on behaviors while also minimizing subjective bias and cognitive burden [53]. | Provided a baseline understanding of demographics, support needs, and visiting patterns in Shimogo and Nanmoku. |

| Descriptive Statistics Table A2, Table A3 and Table A4 | |||

| 2. Dimensionality Reduction | Multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) | To Simplify complex data: MCA identifies underlying relationships between multiple categorical variables [55,56,57,58]. | Allowed the generation of numerical scores representing underlying dimensions of resident needs (Shimogo) and out-migrant motivations/behaviors (Nanmoku). |

| Table A5 and Table A10 Figure A1 and Figure A3 | It allowed us to create interpretable scores for further analysis and provided visual joint category plots of variables. | Enabled the use of these scores in subsequent regression and cluster analyses. | |

| 3. Dimension Interpretation | Qualitative labeling of dimensions Table A6 and Table A11 | To connect abstract dimensions to social context: Dimensions were interpreted based on variable loadings, the existing literature, and the specific context of the study [59]. | Provided a clear understanding of what each dimension represents in terms of resident needs, hometown visit motivations, and behaviors. Facilitated the interpretation of subsequent analyses. |

| 4. Causal Relationship | Multinomial logistic regression [55,58] Table A7 and Table A12 | To link latent structures with visit patterns: Multinomial logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between MCA dimension scores and visit frequency. | Identified significant associations between dimensions and the likelihood of more frequent visits in different subgroups based on how each support dimension or support pattern influences real behavioral patterns. |

| 5. Cluster Identification | Cluster analysis [60] K-means: Table A8 and Table A9, Figure 3 Two Step [61]: Table A13, Table A14 and Table A15, Figure 4 | To provide simplified profiles: Clustering transformed data from numeric-score-based latent dimensions into clear profiles that represent a specific type of social action. | Identified distinct groups of relatives with shared patterns of engagement and support provision. |

| 6. Qualitative Exploration | Thematic coding of interviews, case studies (Section 5.4) | Objective measurements in daily life: Thematic coding of interviews and case studies provided in-depth understanding of lived experiences and contextual factors influencing support patterns. | Provided in-depth understanding of the lived experiences and contextual factors influencing support patterns. Validated and illustrated the findings from the quantitative analyses. |

| Survey Items | Details and Proportion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimogo | Nanmoku | ||||

| Household composition | Total | N = 376 | N = 150 | ||

| Single senior | 146 | 38.8% | 49 | 33.8% | |

| Multi-senior | 201 | 53.5% | 66 | 42.1% | |

| Intergenerational | 29 | 7.7% | 35 | 24.1% | |

| Age of single-senior Household member | Total | N = 146 | N = 49 | ||

| 65–79 | 89 | 60.9% | 13 | 26.5% | |

| Over 80 | 55 | 37.7% | 36 | 73.5% | |

| Not provided | 2 | 1.4% | - | - | |

| Health conditions 1 | Total | N = 357 | N = 146 | ||

| Healthy | 102 | 28.6% | 49 | 33.6% | |

| Only outpatient care | 207 | 58.0% | 78 | 53.4% | |

| Support-reliant | 48 | 13.4% | 19 | 13.0% | |

| Support methods 2 (shopping and medical care) | Total | N = 364 | N = 147 | ||

| Self-help | 233 | 64.0% | 77 | 52.4% | |

| Mutual aid | 38 | 10.4% | 12 | 8.2% | |

| Combined support | 93 | 25.6% | 58 | 39.4% | |

| Survey Items | Details and Proportion | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimogo 1 | Nanmoku 1 | ||||||||

| Family A | Family B | ||||||||

| Location | Total | N = 342 | N = 147 | N = 118 | |||||

| Local Area | Aizu Area | 171 | 50.0% | Seimou Area | 112 | 76.2% | 75 | 63.6% | |

| Main local city | Aizuwakamatsu City | 89/171 | 52.1% | Tomioka City | 32/112 | 28.6% | 20/75 | 26.7% | |

| Takasaki City | 32/112 | 28.6% | 14/75 | 18.7% | |||||

| Others | 82/171 | 47.9% | Others | 28/112 | 42.8% | 41/75 | 54.6% | ||

| Nearby Region | Within Fukushima | 52 | 15.2% | Within Gunma | 17 | 11.6% | 66 | 11.0% | |

| Tokyo Metropolitan | Kanto Region 2 | 100 | 29.2% | Kanto Region 2 Exclude Gunma | 15 | 10.2% | 35 | 22.9% | |

| Other Region | 19 | 5.6% | 3 | 2.0% | 3 | 2.5% | |||

| Age | Total | N = 355 | N = 152 | N = 121 | |||||

| Under 50 | 163 | 48.7% | 47 | 31.0% | 46 | 37.5% | |||

| 50–64 | 109 | 32.5% | 61 | 40.1% | 35 | 29.1% | |||

| 65–74 | 48 | 14.3% | 18 | 11.8% | 20 | 16.7% | |||

| Over 75 | 15 | 4.5% | 26 | 17.1% | 20 | 16.7% | |||

| Hometown visit frequency | Total | N = 313 | N = 151 | N = 119 | |||||

| Weekly | 66 | 21.1% | 50 | 33.1% | 17 | 14.3% | |||

| Monthly | 101 | 32.3% | 64 | 42.4% | 46 | 38.7% | |||

| Yearly | 146 | 46.6% | 37 | 24.5% | 56 | 47.0% | |||

| Relationship 3 | This question was not present in the Shimogo survey | Total | N = 153 | N = 123 | |||||

| Parent | 14 | 9.1% | 2 | 1.6% | |||||

| Child | 110 | 71.9% | 84 | 68.3% | |||||

| Sibling | 24 | 15.7% | 30 | 24.4% | |||||

| Others | 5 | 3.3% | 7 | 5.7% | |||||

| Main purpose of hometown visit 3 (multiple choice) | This question was not present in the Shimogo survey | Total | N = 153 | N = 125 | |||||

| Family reunion | 127 | 83.0% | 104 | 83.2% | |||||

| Chore support | 27 | 17.6% | 20 | 16.0% | |||||

| Farm work | 14 | 9.2% | 11 | 8.8% | |||||

| Outdoor leisure | 25 | 16.3% | 22 | 17.6% | |||||

| Personal social activities | 20 | 13.1% | 10 | 8.0% | |||||

| Grave visits | 94 | 61.4% | 64 | 51.2% | |||||

| Out-Migrated Family | MCA Dimension 1 | Top Contributing Behaviors (Loadings) | Dimension Traits | Influence on Visit Frequency 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimogo Family | Resident Self-Reliance | Farm Work | 0.592 | This dimension reflects the residents’ independence and capacity for self-sufficiency. | Higher scores are associated with less frequent visits (p < 0.001) |

| Yard Work | 0.589 | ||||

| Shopping Support | 0.511 | ||||

| Resident Community Support Needs | Chore Support | 0.656 | This dimension reflects the residents’ need for community resources in the absence of family support. | Higher scores are associated with less frequent visits (p < 0.001) | |

| Outdoor Leisure | 0.664 | ||||

| Nanmoku Family A | Daily Support | Shopping Support | 0.523 | This dimension captures Family A’s motivation to provide routine, practical assistance for daily living and household maintenance. | Higher scores are associated with more frequent visits (p < 0.001) |

| Yard Work | 0.577 | ||||

| Farm Work | 0.559 | ||||

| Community Engagement (Community Support) | Community Activities | 0.564 | This dimension captures Family A’s motivation for active community integration and social participation with their family support activities. | Higher scores are associated with more frequent visits (p < 0.001) | |

| Social Activities | 0.413 | ||||

| Outdoor Leisure | 0.274 | ||||

| Nanmoku Family B | On-Demand Support | Shopping Support | 0.614 | This dimension captures Family B’s motivation to provide routine, practical assistance for daily living and household maintenance. | Higher scores are associated with more frequent visits (p < 0.001) |

| Yard Work | 0.605 | ||||

| Farm Work | 0.499 | ||||

| Community Engagement (Social Contact) | Social Activities | 0.527 | This dimension captures Family B’s motivation for active community integration and social participation with their family support activities. | - | |

| Outdoor Leisure | 0.200 | ||||

| Driving Motivation and Support Approach | Key Characteristics of the Clusters | Hometown Visit Frequency, Location, and Age | Support Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shimogo Family: Obligation-Driven and Localized Support | Cluster 1 N = 107 Obligation-driven Visits | ||

| Primarily younger, distant relatives, providing minimal support and community engagement. | Primarily annual visits; Kanto-based (35.6%); trips made by younger individuals (61.4% are under 50) | Limited practical or emotional support. | |

| Cluster 2 N = 47 High Support and Engagement | |||

| Older Aizu-based relatives with extensive practical engagement and community involvement. | High rate (>monthly) of visits; predominantly Aizu (71.7%); mostly older (65.2% are over 50) | High involvement in chores, shopping, yard work, farm work, and community activities. | |

| Cluster 3 N = 46 Community-Maintenance-focused visits | |||

| Mostly Aizu-based, with a focus on supporting farm work. | Moderate number (mostly annual) of visits; primarily Aizu (55.8%); primarily older individuals (over 50: 54.4%) | Strong focus on farm work. | |

| Cluster 4 (N = 113) Leisure-oriented visits | |||

| Mix of Aizu and Kantō relatives prioritizing social and recreational activities over direct support. | Moderate number (mostly annual, sometimes > monthly) of visits; Aizu and Kanto (50%/32.1%); mixed ages (47.7% are under 50) | Primarily social and outdoor leisure activities. | |

| Nanmoku Family A: Proactive Support and Engagement | Cluster 1 N = 32 Sustained support and multifaceted engagement | ||

| Older, Seimo-based relatives providing comprehensive and consistent support. | Mostly monthly visits (68.7%); parents (16.1%) and children (71.0%) in Seimo (77.4%); ages: 50–65 (45.2%) | High involvement in shopping support, yard work, and farm work. | |

| Cluster 2 N = 34 Community-focused visits | |||

| Oldest relatives with high visit frequencies, primarily focused on shopping, farm work, and community engagement. | Mostly weekly visits (87.9%); primarily children (78.8%) in Seimou (86.2%); oldest in the cohort, with most being over 50 (90.9%) | Focus is on shopping support and community activities. | |

| Cluster 3 N = 89 Obligation-driven visits | |||

| Primarily younger individuals with limited direct support, driven by a sense of obligation. | Annual visits (40.7%); Kanto-based (27.6%); younger individuals (40.9%) | Main purposes of hometown visits are family reunions and grave visits. | |

| Nanmoku Family B: On-Demand Support and Flexible Engagement | Cluster 1 N = 17 Farm work-driven Visits | ||

| Older relatives with high visit frequencies, primarily focused on farm work. | Weekly visits to see children (70.6%); Seimou (88.2%); over 50 (41.2%) | Primarily farm work and outdoor leisure. | |

| Cluster 2 N = 46 Leisure-driven flexible support | |||

| Varied relatives, with visits combining household assistance and leisure. | Monthly visits to see children (68.9%) and siblings (22.0%); Seimou (81.4%); mixed ages (all stages of life) | Balancing shopping support with outdoor leisure activities. | |

| Cluster 3 N = 56 Contact-driven visits | |||

| A mix of ages and locations, with infrequent visits and less direct forms of support. | Annual visits to see children (70.9%) and siblings (25.5%); Kanto-based (34.5%); more varied ages (71.4% under 50) | Primary focus is on social activities. |

| Feature | Shimogo Resident-Driven Support | Nanmoku Out-Migrant-Driven Support |

|---|---|---|

| Geographic Context | Localized isolation; self-contained support | Isolation within metro region; strategic support networks |

| Primary Driver of Support | Resident needs as perceived by out-migrants | Out-migrant motivations shape support delivery |

| Focus of Support | Primarily meeting immediate local needs | Balancing family care with community engagement, strategic support |

| Out-Migrant Role | Supplements local resources; responds to specific needs | Family A provides direct support; Family B provides flexible and symbolic support |

| Limitations | Limited by proximity and family availability with respect to acting as a support network | Limited by out-migrants’ individual choices regarding their engagement and patterns of visiting |

| Flow Pathways | Localized networks; nearby cities and towns are the focus | Strategic use of local towns and regional hubs; limited direct support from Tokyo |

| Resident Profile | Case 1: Isolated Elderly Single Resident | Case 2: Interconnected Couple |

|---|---|---|

| Resident Demographics | This individual is an 80-year-old woman with a strong desire to remain where she is. She lives alone in a geographically isolated area and has two out-migrated children. | This couple (over 65) is composed of a husband who is still working and a wife who manages household and farming activities, with the produce being primarily for family use. They have two out-migrated children (and grandchildren). |

| Support Network | This support network is multi-layered, with the local community (a mobile vendor, an on-demand car dealer, and a day service for bathing) and family (a son in Takasaki and a son in Tokyo) providing distinct forms of support. | Intergenerational support: their son in Tomioka provides regular practical assistance, and their daughter in Aichi will return during summer vacation, with this couple providing childcare during visits. |

| Out-Migrant Mobility | Son in Takasaki (Cluster A1, shopping support and community activities) and son in Tokyo (Cluster B1, farm work). | Son in Tomioka (Cluster A1, mainly shopping support), daughter in Aichi (Cluster B3), and son with variable locations and mixed support. |

| Community Context | Severely depopulated, limited infrastructure; reliant on community support. | An active, though aging, community with existing local infrastructure and where the husband remains engaged as a local organizer. |

| Resident Capacity | She is limited by her age and geographic isolation, but her desire for autonomy and resistance to moving is strong; her children respond with individually structured support. | This couple has a more active approach to daily living, with a focus on maintaining their home, their connections with their family, and their community through their own efforts. |

| Long-Term Prospects | Limited U-turn potential due to the remote location and the limited resources of the community. | Higher U-turn potential, with the son in Tomioka demonstrating ongoing engagement and a strong likelihood of maintaining multigenerational ties. |

| Limitations | Limited by proximity and the availability of this woman’s family to act as a support network. | Limited by out-migrants’ individual choices regarding their engagement and patterns of visiting. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Cheng, Y.; Saito, Y. Can the Relationship Population Contribute to Sustainable Rural Development? A Comparative Study of Out-Migrated Family Support in Depopulated Areas of Japan. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052142

Wang W, Cheng Y, Saito Y. Can the Relationship Population Contribute to Sustainable Rural Development? A Comparative Study of Out-Migrated Family Support in Depopulated Areas of Japan. Sustainability. 2025; 17(5):2142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052142

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wanqing, Yumeng Cheng, and Yukihiko Saito. 2025. "Can the Relationship Population Contribute to Sustainable Rural Development? A Comparative Study of Out-Migrated Family Support in Depopulated Areas of Japan" Sustainability 17, no. 5: 2142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052142

APA StyleWang, W., Cheng, Y., & Saito, Y. (2025). Can the Relationship Population Contribute to Sustainable Rural Development? A Comparative Study of Out-Migrated Family Support in Depopulated Areas of Japan. Sustainability, 17(5), 2142. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17052142