Social Relations and Place Identity of Development-Induced Migrants: A Case Study of Rural Migrants Relocated from the Three Gorges Dam, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Conceptual Foundations: Place Identity and Forced Migration

2.2. Special Features in Rural China and Evaluation Dimensions

2.3. Influencing Factors for Place Identity

2.4. The Bridging Role of Social Relations

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Region and Data

3.2. Methods

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Exogenous Latent Variables

3.3.2. Mediating Variable

3.3.3. Endogenous Latent Variable

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Overview of Migrants’ Basic Characteristics and Place Identity

4.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing Place Identity Among Migrants

4.2.1. SEM Validation

4.2.2. Measurement Model Path Analysis

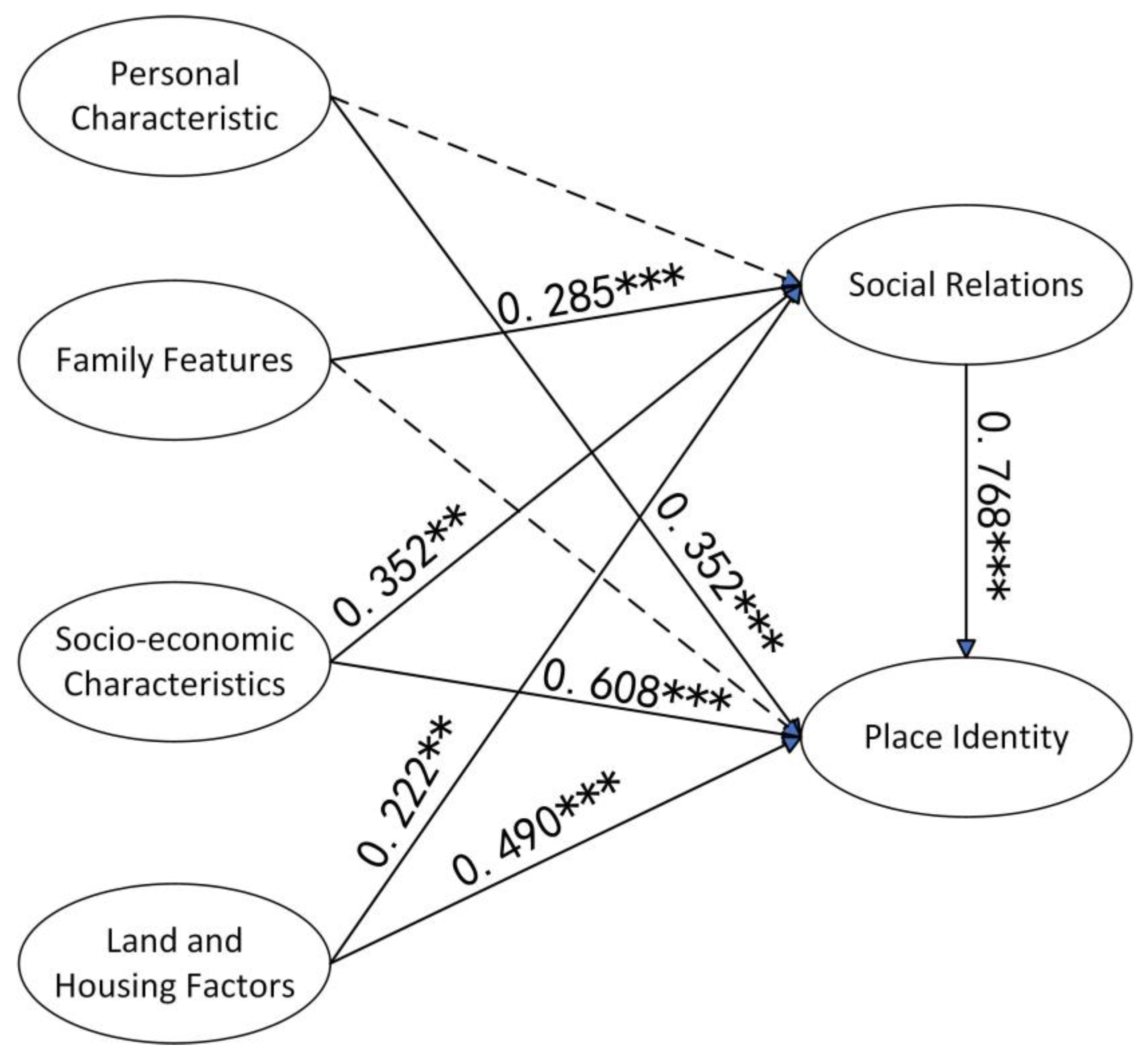

4.2.3. Paths Affecting Place Identity

4.2.4. The Mediating Role of Social Relations

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sheng, J.; Michael, W.; Han, X. Authoritarian neoliberalization of water governance: The case of China’s South–North Water Transfer Project. Territ. Politics Gov. 2021, 9, 691–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandishekwa, R. Rethinking mining as a development panacea: An analytical review. Miner. Econ. 2021, 34, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satiroglu, I.; Choi, N. Development-Induced Displacement and Resettlement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cernea, M. The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. World Devlopment 1997, 25, 1569–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessey, F.O.; Tay, P.O. Resettlement induced secondary poverty in developing countries. Dev. Ctry. Stud. 2015, 5, 170–179. [Google Scholar]

- Wilmsen, B. Is Land-based Resettlement Still Appropriate for Rural People in China? A Longitudinal Study of Displacement at the Three Gorges Dam. Dev. Chang. 2018, 49, 170–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; de Sherbinin, A.; Liu, Y. China’s poverty alleviation resettlement: Progress, problems and solutions. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullet, P.; Koonan, S. Research Handbook on Law, Environment and the Global South; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- UKEssays. Case Study of the Akosombo Hydroelectric Dam Environmental Sciences Essay. Available online: https://www.ukessays.com/essays/environmental-sciences/case-study-of-the-akosombo-hydroelectric-dam-environmental-sciences-essay.php?vref=1 (accessed on 1 May 2025).

- Jackson, I.; Ola, U.; Irene, A.A.; Assasie Opong, R. The Volta River Project: Planning, housing and resettlement in Ghana, 1950–1965. J. Archit. 2019, 24, 512–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Huang, Q.; Ding, L. The influence of regional cultural differences on the backmigration of remote reservoir migrants. Popul. Econ. 1999, 1, 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Alhassan, H.S. Viewpoint–Butterflies vs. hydropower: Reflections on large dams in contemporary Africa. Water Altern. 2009, 2, 148–160. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, H.E.; Ludwig, B.; Braslow, L. Forced Migration. In International Handbook of Migration and Population Distribution; White, M.J., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 605–625. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S.; Castada, C.; Fortier, A.-M.; Sheller, M. Uprootings/Regroundings: Questions of Home and Migration; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Malmberg, G. Time and space in international migration. In International Migration, Immobility and Development; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 21–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment, place identity, and place memory: Restoring the forgotten city past. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 209–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Soopramanien, D. Types of place attachment and pro-environmental behaviors of urban residents in Beijing. Cities 2019, 84, 112–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Strijker, D.; Wu, Q. Place identity: How far have we come in exploring its meanings? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, B.; Carmen Hidalgo, M.; Salazar-Laplace, M.E.; Hess, S. Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. J. Environ. Psychol. 2007, 27, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratnam, C. Creating home: Intersections of memory and identity. Geogr. Compass 2018, 12, e12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpas, J. Place and Experience: A Philosophical Topography, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Stepputat, F.; Sørensen, N.N. Sociology and forced migration. In The Oxford Handbook of Refugee and Forced Migration Studies; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; pp. 86–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz, I.; Siegel, M.; Vargas-Silva, C. Forced Up or Down? The Impact of Forced Migration on Social Status. J. Refug. Stud. 2015, 28, 183–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dromgold-Sermen, M.S. Forced migrants and secure belonging: A case study of Syrian refugees resettled in the United States. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundvall, M.; Titelman, D.; DeMarinis, V.; Borisova, L.; Çetrez, Ö. Safe but isolated—An interview study with Iraqi refugees in Sweden about social networks, social support, and mental health. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2020, 67, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunwoodie, K.; Webb, S.; Wilkinson, J.; Newman, A. Social Capital and the Career Adaptability of Refugees. Int. Migr. 2025, 63, e12787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, X. From the Soil: The Foundations of Chinese Society; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y. The culture of guanxi in a North China village. In People’s Republic of China, Volumes I and II; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 221–245. [Google Scholar]

- Murad, S.; Versey, H.S. Barriers to leisure-time social participation and community integration among Syrian and Iraqi refugees. Leis. Stud. 2021, 40, 378–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudder, T.T. The Future of Large Dams: Dealing with Social, Environmental, Institutional and Political Costs; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tilt, B.; Gerkey, D. Dams and population displacement on China’s Upper Mekong River: Implications for social capital and social–ecological resilience. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 36, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzo, L.C.; Kleit, R.G.; Couch, D. “Moving Three Times Is Like Having Your House on Fire Once”: The Experience of Place and Impending Displacement among Public Housing Residents. Urban Stud. 2008, 45, 1855–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stedman, R.C. Toward a social psychology of place: Predicting behavior from place-based cognitions, attitude, and identity. Environ. Behav. 2002, 34, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupat, E. A place for place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 1983, 3, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, Y.-F. Space and place: Humanistic perspective. In Philosophy in Geography; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; pp. 387–427. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.S. Introduction: Putting place back in place attachment research. In Explorations in Place Attachment; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lewicka, M. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? J. Environ. Psychol. 2011, 31, 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, E.; Moreno, R.; Tarjuelo, B. Identity and Immigration. From Ulysses’ Syndrome to the Identity Construct and their Cultural Development. Eur. Psychiatry 2017, 41 (Suppl. S1), S622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianucci, R.; Charlier, P.; Perciaccante, A.; Lippi, D.; Appenzeller, O. The “Ulysses syndrome”: An eponym identifies a psychosomatic disorder in modern migrants. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 41, 30–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhugra, D.; Becker, M.A. Migration, cultural bereavement and cultural identity. World Psychiatry 2005, 4, 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, M.S.; Zhang, N.; Feyissa, I.F. Cultural Bereavement and Mental Distress: Examination of the Cultural Bereavement Framework through the Case of Ethiopian Refugees Living in South Korea. Healthcare 2022, 10, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alirhayim, R. Place attachment in the context of loss and displacement: The case of Syrian immigrants in Esenyurt, Istanbul. J. Urban Aff. 2025, 47, 381–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadipour, M.S.; Sordé-Martí, T. From Exile to Belonging: The [re] construction of Identity in the Context of Forced Migration. Int. Multidiscip. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 193–210. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Chen, G. Can ‘relationship’ bring happiness?–empirical evidence from rural China. Chin. Rural. Econ. 2012, 8, 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, A. The Differential Mode of Association in Contemporary China. China Rev. 2024, 24, 233–250. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Xie, Y.; Yan, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, C. The Reshaping of Neighboring Social Networks after Poverty Alleviation Relocation in Rural China: A Two-Year Observation. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, G.; Yang, D.; Li, J. Does Migration Distance Affect Happiness? Evidence From Internal Migrants in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 913553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.O. Forced displacement in history: Some recent research. Aust. Econ. Hist. Rev. 2022, 62, 2–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y. Social trust, social capital, and subjective well-being of rural residents: Micro-empirical evidence based on the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS). Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotevant, H.D. Toward a Process Model of Identity Formation. J. Adolesc. Res. 1987, 2, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, A.; Rapport, N. Migrants of Identity: Perceptions of ‘Home’ in a World of Movement; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Guo, X.; Li, C.; Qian, W. Social ties and urban settlement intention of rural-to-urban migrants in China: The mediating role of place attachment and the moderating role of spatial pattern. Cities 2024, 145, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcia, J.E. Development and validation of ego-identity status. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1966, 3, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunarska, Z.; Ivlevs, A. Forced displacement and subsequent generations’ migration intentions: Intergenerational transmission of family migration capital. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 2423–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokol, J.T. Identity development throughout the lifetime: An examination of Eriksonian theory. Grad. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 1, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, M.C.; HernÁNdez, B. Place Attachment: Conceptual and Empirical Questions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2001, 21, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ujang, N. Place Attachment and Continuity of Urban Place Identity. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 156–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummon, D.M. Community attachment: Local sentiment and sense of place. In Place Attachment; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 253–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bonaiuto, M.; Mao, Y.; Roberts, S.; Psalti, A.; Ariccio, S.; Ganucci Cancellieri, U.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. Optimal Experience and Personal Growth: Flow and the Consolidation of Place Identity. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.; Wu, F.; Li, Z. Beyond neighbouring: Migrants’ place attachment to their host cities in China. Popul. Space Place 2021, 27, e2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J.; Mahmoudian, H.; Sadeghi, R. Family Dynamics in the Context of Forced Migration. In Demography of Refugee and Forced Migration; Hugo, G., Abbasi-Shavazi, M.J., Kraly, E.P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, A.; Garcia-Ramon, M.D.; Prats, M. Women’s use of public space and sense of place in the Raval (Barcelona). GeoJournal 2004, 61, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, Q. Neighbourhood planning and the impact of place identity on housing development in England. Plan. Theory Pract. 2017, 18, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knez, I.; Butler, A.; Ode Sang, Å.; Ångman, E.; Sarlöv-Herlin, I.; Åkerskog, A. Before and after a natural disaster: Disruption in emotion component of place-identity and wellbeing. J. Environ. Psychol. 2018, 55, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Rubio, M.Á. Local place identity: A comparison between residents of rural and urban communities. J. Rural. Stud. 2021, 82, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J. Return or relocate? An inductive analysis of decision-making in a disaster. Disasters 2013, 37, 293–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasci, A.D.A.; Uslu, A.; Stylidis, D.; Woosnam, K.M. Place-Oriented or People-Oriented Concepts for Destination Loyalty: Destination Image and Place Attachment versus Perceived Distances and Emotional Solidarity. J. Travel Res. 2021, 61, 430–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; de Jong, M.; Song, Y.; Zhao, M. The multi-level governance of formulating regional brand identities: Evidence from three Mega City Regions in China. Cities 2020, 100, 102668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, R.A.; Andrews, G. Geographies of wellbeing. In The SAGE Handbook of Social Geographies; Sage: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 309–328. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, M.; Wu, W.; Zhong, W.; Zeng, G.; Wang, S. The reshaping of social relations: Resettled rural residents in Zhenjiang, China. Cities 2017, 60, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wu, F. The effect of neighbourhood social ties on migrants’ subjective wellbeing in Chinese cities. Habitat Int. 2017, 66, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. Internal Migration as a Life-Course Trajectory: Concepts, Methods and Empirical Applications; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Lestari, W.M.; Sumabrata, J. The influencing factors on place attachment in neighborhood of Kampung Melayu. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2018, 126, 012190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gliemann, K.; Szypulski, A. Integration von Flüchtlingen—Auch eine Frage der Wohnunterbringung. In Soziale Sicherung im Umbruch: Transdisziplinäre Ansätze für Soziale Herausforderungen Unserer Zeit; Kaiser, L.C., Ed.; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2018; pp. 105–123. [Google Scholar]

- Osman, F.; Mohamed, A.; Warner, G.; Sarkadi, A. Longing for a sense of belonging—Somali immigrant adolescents’ experiences of their acculturation efforts in Sweden. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2020, 15 (Suppl. S2), 1784532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Working Together for Local Integration of Migrants and Refugees; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Hu, J.; Yang, G.; Wang, Y. How Destination City and Source Landholding Factors Influence Migrant Socio-Economic Integration in the Pearl River Delta Metropolitan Region. Land 2023, 12, 1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-Q.; Antonides, G.; Christian, H.K.; Nie, F.-Y. Mental accounting and consumption of self-produced food. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 2569–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Ma, Y.; Qin, G.; Xu, C.; Zhu, Y. Why Chinese farmers are reluctant to transfer their land in the context of non-agricultural employment: Insights from agricultural mechanization. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muringani, J.; Fitjar, R.D.; Rodríguez-Pose, A. Social capital and economic growth in the regions of Europe. Environ. Plan. A 2021, 53, 1412–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lu, X.; Huang, C.; Liu, W.; Wang, G. The Impact of Social Capital on Migrants’ Social Integration: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilt, B.; Braun, Y.; He, D. Social impacts of large dam projects: A comparison of international case studies and implications for best practice. J. Environ. Manag. 2009, 90, S249–S257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koranteng, R.T.B.; Shi, G. Using informal institutions to address resettlement issues–the case of Ghana dams dialogue. J. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 11, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Xue, D.; Li, Z.; Shi, Z. The effects of social ties on rural-urban migrants’ intention to settle in cities in China. Cities 2018, 83, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sunikka-Blank, M. Urban densification and social capital: Neighbourhood restructuring in Jinan, China. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 244–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | Category | Number | Proportion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 268 | 75.92% |

| Female | 85 | 24.08% | |

| Age | 0–14 | 0 * | 0.00% |

| 15–64 | 306 | 86.69% | |

| 65 and above | 47 | 13.31% | |

| Education | Primary school or below | 152 | 43.06% |

| Junior high school | 160 | 45.33% | |

| High school | 28 | 7.93% | |

| College or above | 13 | 3.68% | |

| Occupation | Worker | 257 | 72.80% |

| Business owner | 17 | 4.81% | |

| Other | 10 | 2.83% | |

| Self-employed farmer | 69 | 19.54% | |

| Resettlement Year | 1999 | 17 | 4.82% |

| 2000 | 101 | 28.61% | |

| 2001 | 104 | 29.46% | |

| 2002 | 75 | 21.25% | |

| 2003 | 5 | 1.42% | |

| Land Status | No land | 54 | 15.30% |

| Possessing 0–4 mu | 185 | 52.41% | |

| Possessing 4–10 mu | 91 | 25.78% | |

| Possessing over 10 mu | 23 | 6.51% |

| Latent Variable | Measurement Variable | Coding Scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Personal Characteristics | Gender | Female: 1; Male: 2 |

| Age/year | Below 40: 1; 40–49: 2; 50–59: 3; 60–69: 4; sbove 70: 5 | |

| Relation to migrants | Migrant: 1; descendant of migrant: 2 | |

| Education | primary school or below: 1; junior high school: 2; high school: 3; college or above: 4 | |

| Occupation | self-employed farmer: 1; worker: 2; business owner: 3; other: 4 | |

| Family Features | Household size/person | 3 or fewer: 1; 4–5: 2; 6–7: 3; 8 or more: 4 |

| Residential continuity | Refer to Table 3 | |

| Proportion of employed family members | Below 25%: 1; 26–50%: 2; 51–75%: 3; 76–100%: 4 | |

| Socio-Economic Characteristics | Urban economic gap (based on GDP of affiliated prefecture—level cities in 2022)/RMB trillion | Below 2.5: 1; 2.6–5.9: 2; 6.0–14.9: 3; above 15.0: 4 |

| per capita disposable income of migrant household/RMB | Below 10,000: 1; 10,001–19,999: 2; 20,000–29,999: 3; 30,000–49,999: 4; above 50,000: 5 | |

| Land and Housing Factors | Housing status | Allocated as the only housing: 1; with extra self-built or purchased housing: 2 |

| Per capita housing area/m2 | Below 40: 1; 40–60: 2; 60–80: 3; above 80: 4 | |

| Land dependence | Landless: 1; owned but uncultivated: 2; cultivating less than 30% of allocated land: 3; cultivating 31–99% of allocated land: 4; cultivating all allocated land: 5; renting additional land for agricultural activities: 6 |

| Absence Time | No Out-Migration | Short-Term Out (Less than 3 Months per Year) | Intermediate Out (3–6 Months per Year) | Long-Term Out (6–12 Months per Year) | Permanent Out | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | ||||||

| Village/Community | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | |

| County | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | |

| Province | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0 | |

| Across Provinces | 0.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | |

| Measured Indicator | Coding Specification |

|---|---|

| Number of Contacts (s) | 1: 1–2 persons; 2: 3–5 persons; 3: 6–10 persons; 4: 11–20 persons; 5: >20 persons |

| Interaction Frequency (q) | 1/1: Nearly every day; 1/2: approximately once per week; 1/3: approximately once per month; 1/4: once every several months; 0: none |

| Interaction Depth (d) | 0: None; 1: daily-life exchange, leisure, work-related contact; 2: consultation, emotional support; 3: borrowing money, handling affairs |

| Score | Share (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group Identity | Permanent Settlement Intention | Expectations for Children | |

| 1 | 4.53% | 1.42% | 1.42% |

| 2 | 11.90% | 2.27% | 3.68% |

| 3 | 22.38% | 30.88% | 29.46% |

| 4 | 40.79% | 46.46% | 42.49% |

| 5 | 20.40% | 18.98% | 22.95% |

| Mean | 3.61 | 3.79 | 3.82 |

| Factor | Variable | Unstandardized Loading | Standardized Loading | z | S.E. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Place Identity | Group identity | 1.000 | 0.528 | - | - | - |

| Permanent settlement intention | 0.456 | 0.330 | 2.667 | 0.171 | 0.008 *** | |

| Expectations for children | 1.211 | 0.777 | 4.531 | 0.267 | 0.000 *** | |

| Personal Characteristics | Gender | 1 | 0.129 | - | - | - |

| Age | −0.772 | −0.114 | −0.825 | 0.937 | 0.41 | |

| Education | 16.503 | 0.932 | 1.102 | 14.977 | 0.271 | |

| Occupation | −7.859 | −0.556 | −1.192 | 6.593 | 0.233 | |

| Relation to migrants | 2.233 | 0.468 | 2.143 | 1.042 | 0.032 ** | |

| Family Features | Household size | 1.000 | 0.723 | - | - | - |

| Residential continuity | 0.049 | 0.471 | 4.084 | 0.012 | 0.000 *** | |

| Proportion of employed family Members | 0.874 | 0.689 | 5.693 | 0.153 | 0.000 *** | |

| Socio-Economic Characteristics | Urban economic gap | 1.000 | 0.909 | - | - | - |

| Per capita disposable income | 0.100 | 0.766 | 0.530 | 0.188 | 0.006 *** | |

| Land and Housing Factors | Housing status | 1.000 | 1.000 | - | - | - |

| Per capita housing area | 2.816 | 0.874 | 7.076 | 0.398 | 0.000 *** | |

| Land dependence | 0.368 | 0.277 | 2.297 | 0.16 | 0.022 ** | |

| Social Relations | Number of total contacts | 1.000 | 0.735 | - | - | - |

| Home-tied social relations | −0.060 | −0.181 | −1.678 | 0.036 | 0.093 * | |

| Geographical social relations | 1.215 | 0.747 | 5.958 | 0.204 | 0.000 *** | |

| Carried-over social relations | 0.115 | 0.463 | 4.297 | 0.027 | 0.000 *** |

| Mediating Path | Effect Value | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal characteristic → social relations → place identity | −0.384 | (−0.019, 0.031) | 0.037 |

| family features → social relations → place identity | 0.024 | (0.015, 0.073) | 0.004 *** |

| socioeconomic characteristics → social relations → place identity | 0.019 | (0.027, 0.043) | 0.017 ** |

| land and housing factors → social relations → place identity | 0.032 | (0.003, 0.065) | 0.006 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gao, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhao, Y. Social Relations and Place Identity of Development-Induced Migrants: A Case Study of Rural Migrants Relocated from the Three Gorges Dam, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104690

Gao Y, Gao X, Zhao Y. Social Relations and Place Identity of Development-Induced Migrants: A Case Study of Rural Migrants Relocated from the Three Gorges Dam, China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(10):4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104690

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Yiran, Xiaolu Gao, and Yunning Zhao. 2025. "Social Relations and Place Identity of Development-Induced Migrants: A Case Study of Rural Migrants Relocated from the Three Gorges Dam, China" Sustainability 17, no. 10: 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104690

APA StyleGao, Y., Gao, X., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Social Relations and Place Identity of Development-Induced Migrants: A Case Study of Rural Migrants Relocated from the Three Gorges Dam, China. Sustainability, 17(10), 4690. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17104690