Antifungal Activity of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles Co-Loaded in Zinc–Alginate Microparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Preparation of ALG/Zn Microparticles and Formulations with AgNPs, ZnONPs, or a Mixture of AgNPs + ZnONPs

2.1.2. Isolation and Identification of Fusarium solani

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Attenuated Total Reflectance Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (ATR-FTIR)

2.2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Formulations

2.2.3. Microscopic Observations

2.2.4. Testing the Antifungal Effect of Novel Formulations on Fusarium solani

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Identification of Molecular Interactions Between Formulations Constituents

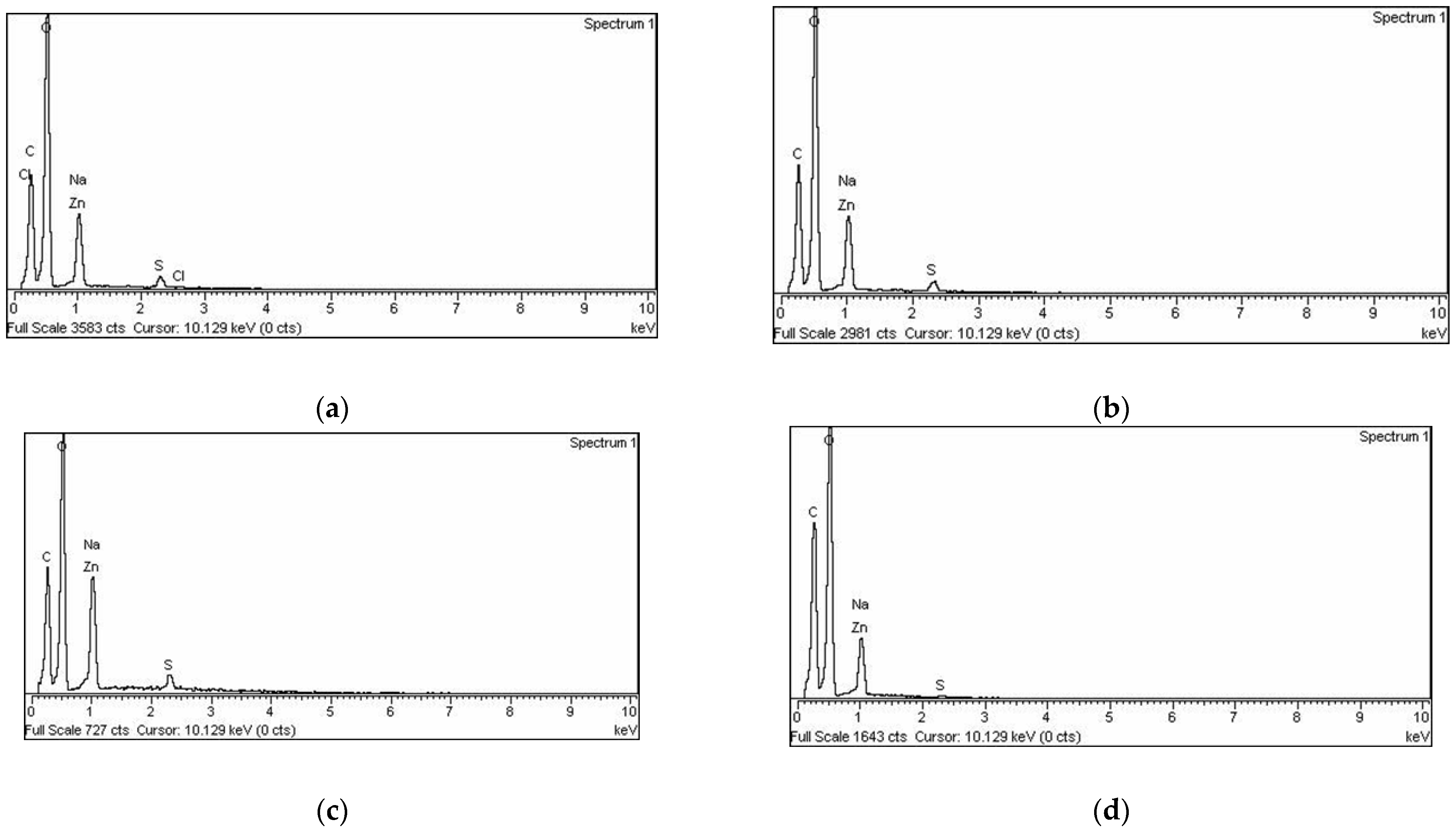

3.2. Microscopic Analyses

3.2.1. Size, Shape, and Morphology of AgNPs and ZnONPs

3.2.2. Morphological Properties of Microparticles

3.3. In Vitro AgNP and ZnONP Release from Formulations

4. Influence of Novel Formulations on Pythopatogenic Fungus Fusarium solani

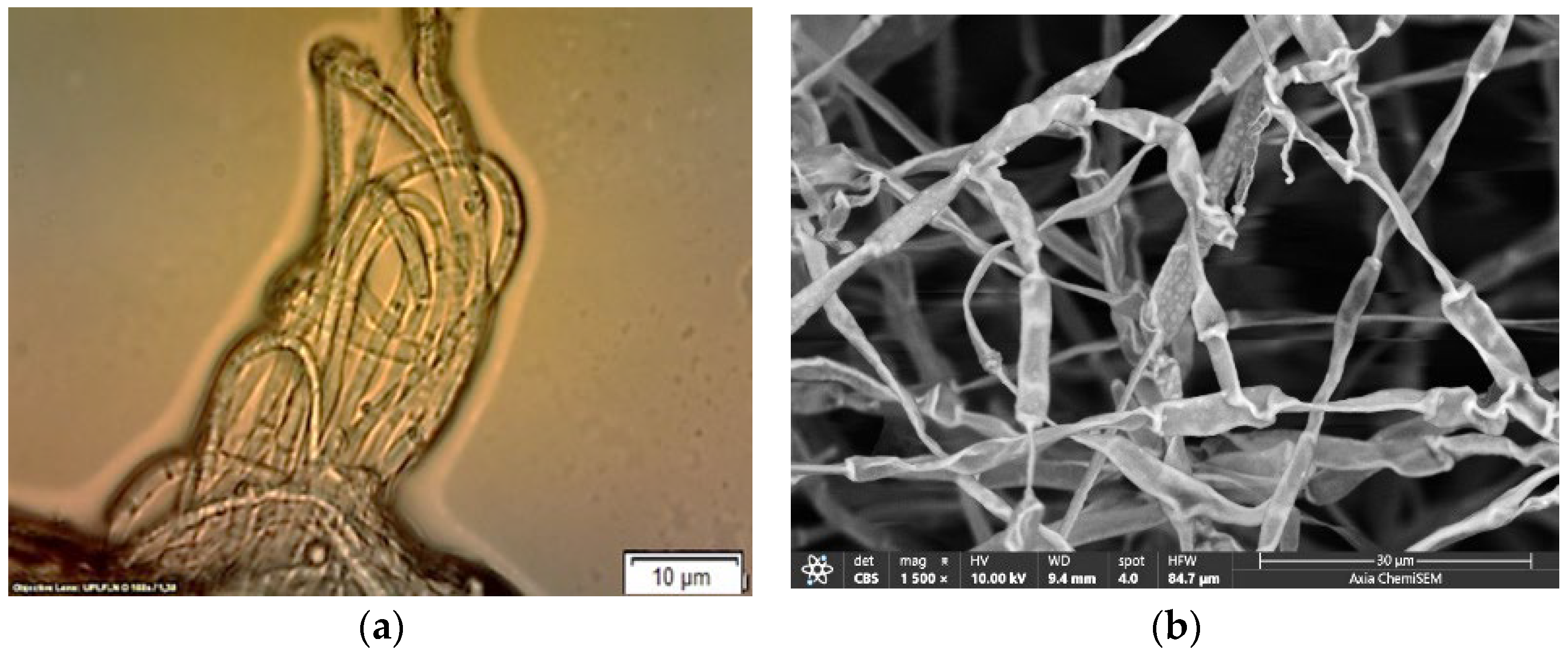

4.1. Morphological Characterization of Fusarium solani

4.2. Influence of Formulations on the Fusarium solani Hyphae

4.3. FTIR Spectrum of Fusarium solani After the Application of Formulations

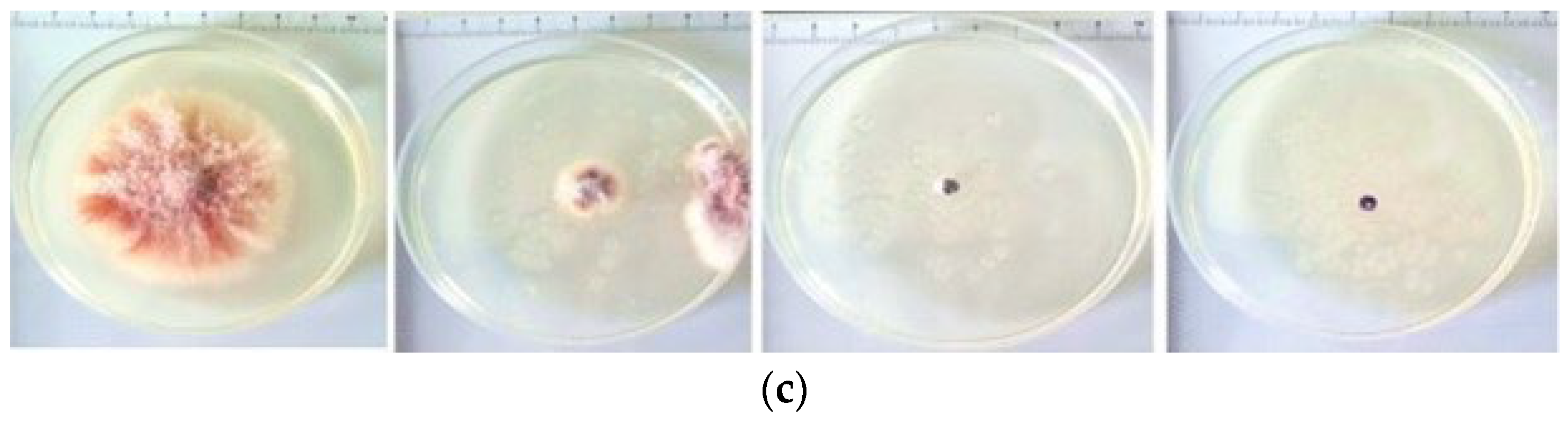

4.4. Antifungal Effect of Formulations on Fusarium solani

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Islam, T.; Danishuddin; Tamanna, N.T.; Matin, M.N.; Barai, H.R.; Haque, M.A. Resistance Mechanisms of Plant Pathogenic Fungi to Fungicide, Environmental Impacts of Fungicides, and Sustainable Solutions. Plants 2024, 13, 2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.C.; Gurr, S.J.; Cuomo, C.A.; Blehert, D.S.; Jin, H.; Stukenbrock, E.H.; Stajich, J.E.; Kahmann, R.; Boone, C.; Denning, D.W.; et al. Threats Posed by the Fungal Kingdom to Humans, Wildlife, and Agriculture. mBio 2020, 11, e00449-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dakal, T.C.; Kumar, A.M.; Majumdar, R.S.; Yadav, V. Mechanistic Basis of Antimicrobial Actions of Silver Nanoparticles. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagoub, A.E.A.; Al-Shammari, G.M.; Al-Harbi, L.N.; Subash-Babu, P.; Elsayim, R.; Mohammed, M.A.; Yahya, M.A.; Fattiny, S.Z.A. Antimicrobial Properties of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles Synthesized from Lavandula pubescens Shoot Methanol Extract. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canaparo, R.; Foglietta, F.; Limongi, T.; Serpe, L. Biomedical Applications of Reactive Oxygen Species Generation by Metal Nanoparticles. Materials 2021, 14, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Oves, M.; Khan, M.S.; Habib, S.S.; Memic, A. Antimicrobial activity of metal oxide nanoparticles against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria: A comparative study. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 6003–6009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelgrift, R.Y.; Friedman, A.J. Nanotechnology as a therapeutic tool to combat microbial resistance. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2013, 65, 1803–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harun-Ur-Rashid, M.; Foyez, T.; Krishna, S.B.N.; Podal, S.; Imran, A.B. Recent advances of silver nanoparticle—Based polymer nanocomposites for biomedical applications. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 8480–8505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzammil, S.; Ashraf, A.; Siddique, M.H.; Aslam, B.; Rasul, I.; Abbas, R.; Afzal, M.; Faisal, M.; Hayat, S. A review on toxicity of nanomaterials in agriculture: Current scenario and future prospects. Sci. Prog. 2023, 106, 368504231221672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate: Properties and biomedical applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 106–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augst, A.D.; Kong, H.J.; Mooney, D.J. Alginate hydrogels as biomaterials. Macromol. Biosci. 2006, 6, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malektaj, H.; Drozdov, A.D.; deClaville Christiansen, J. Mechanical Properties of Alginate Hydrogels Cross-Linked with Multivalent Cations. Polymers 2023, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, L.; Zheng, D.; Xu, J.; Gao, X.; Fu, X.; Zhang, Q. Effects of ionic crosslinking on physical and mechanical properties of alginate mulching films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 259–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleten, K.G.; Hyldbakk, A.; Einen, C.; Benjakul, S.; Strand, B.L.; Davies, C.D.L.; Mørch, Ý.; Flatmark, K. Alginate Microsphere Encapsulation of Drug-Loaded Nanoparticles: A Novel Strategy for Intraperitoneal Drug Delivery. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakr, N.; Lin, S.X.; Chen, X.D. Effects of Drying Methods on the Release Kinetics of Vitamin B12 in Calcium Alginate Beads. Dry. Technol. 2009, 27, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natori, N.; Shibano, Y.; Hiroki, A.; Taguchi, M.; Miyajima, A.; Yoshizawa, K.; Kawano, Y.; Hanawa, T. Preparation and Evaluation of Hydrogel Film Containing Tramadol for Reduction of Peripheral Neuropathic Pain. J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 112, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, S.P.; Chaudhary, M.; Pasricha, R.; Ahmad, A.; Sastry, M. Synthesis of gold nanotriangles and silver nanoparticles using Aloevera plant extract. Biotechnol. Prog. 2006, 22, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elumalai, E.K.; Prasad, T.N.V.K.V.; Hemachandran, J.; Therasa, S.V.; Thirumalai, T.; David, E.J. Extracellular synthesis of silver nanoparticles using leaves of Euphorbia hirta and their antibacterial activities. J. Pharm. Sci. Res. 2010, 2, 549–554. Available online: https://europub.co.uk/articles/-A-85195 (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Vanaja, M.; Annadurai, G. Coleus aromaticus leaf extract mediated synthesis of silver nanoparticles and its bactericidal activity. Appl. Nanosci. 2013, 3, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojnarowicz, J.; Opalinska, A.; Chudoba, T.; Gierlotka, S.; Mukhovskyi, R.; Pietrzykowska, E.; Sobczak, K.; Lojkowski, W. Effect of Water Content in Ethylene Glycol Solvent on the Size of ZnO Nanoparticles Prepared Using Microwave Solvothermal Synthesis. J. Nanomater. 2016, 2016, 2789871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Jiang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Daskalakis, N.; Jeuken, L.; Povey, M.; O’Neill, A.J.; York, D.W. Mechanistic investigation into antibacterial behaviour of suspensions of ZnO nanoparticles against E. coli. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2010, 12, 1625–1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, R.; Xia, Q. Release mechanism of lipid nanoparticles immobilized within alginate beads influenced by nanoparticle size and alginate concentration. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2019, 297, 1183–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jurić, S.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Martinko, K.; Šegota, S.; Marijan, M.; Krčelić, A.; Svečnjak, L.; Majdak, M.; Nemet, I.; et al. Novel Zinc/Silver Ions-Loaded Alginate/Chitosan Microparticles Antifungal Activity against Botrytis cinerea. Polymers 2023, 15, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jay, S.M.; Saltzman, W.M. Controlled delivery of VEGF via modulation of alginate microparticle ionic crosslinking. J. Control. Release 2009, 134, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Modeling of diffusion controlled drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2012, 161, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khvorostina, M.A.; Algebraistova, P.Y.; Nedorubova, I.A.; Bukharova, T.B.; Goldshtein, D.V.; Teterina, A.Y.; Komlev, V.S.; Popov, V.K. The Influence of Crosslinking Agents on the Matrix Properties of Hydrogel Structures Based on Sodium Alginate. Inorg. Mater. Appl. Res. 2024, 15, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peretiatko, C.D.S.; Hupalo, E.A.; da Rocha Campos, J.R.; Budziak Parabocz, C.R. Efficiency of Zinc and Calcium Ion Crosslinking in Alginate-coated Nitrogen Fertilizer. Orbital Electron. J. Chem. 2018, 10, 218–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boughbina-Portolés, A.; Sanjuan-Navarro, L.; Moliner-Martínez, Y.; Campíns-Falcó, P. Study of the Stability of Citrate Capped AgNPs in Several Environmental Water Matrices by Asymmetrical Flow Field Flow Fractionation. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokstad, A.M.A.; Lacik, I.; de Vos, P.; Strand, B.L. Advances in biocompatibility and physico-chemical characterization of microspheres for cell encapsulation. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2014, 67–68, 111–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleetus, C.M.; Alvarez Primo, F.; Fregoso, G.; Lalitha Raveendran, N.; Noveron, J.C.; Spencer, C.T.; Ramana, C.V.; Joddar, B. Alginate Hydrogels with Embedded ZnO Nanoparticles for Wound Healing Therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 5097–5111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingar Draget, K.; Østgaard, K.; Smidsrød, O. Homogeneous alginate gels: A technical approach. Carbohydr. Polym. 1990, 14, 159–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruschi, M.L. Mathematical models of drug release. In Strategies to Modify the Drug Release from Pharmaceutical Systems; Bruschi, M.L., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 63–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lao, L.L.; Peppas, N.A.; Boey, F.Y.-C.; Venkatraman, S.S. Modeling of Drug Release from Bulk-Degrading Polymers. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 418, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azadi, S.; Ashrafi, H.; Azadi, A. Mathematical modeling of drug release from swellable polymeric nanoparticles. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 7, 125–133. Available online: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/ (accessed on 17 August 2025).

- Laracuente, M.L.; Yu, M.H.; McHugh, K.J. Zero-order drug delivery: State of the art and future prospects. J. Control. Release 2020, 327, 834–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parvin, N.; Joo, S.W.; Mandal, T.K. Nanomaterial-Based Strategies to Combat Antibiotic Resistance: Mechanisms and Applications. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gaashani, R.; Pasha, M.; Jabbar, K.A.; Shetty, A.R.; Bagiah, H.; Mansour, S.; Kochkodan, V.; Lawler, J. Antimicrobial activity of ZnO-Ag-MWCNTs nanocomposites prepared by a simple impregnation–calcination method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQurashi, D.M.; AlQurashi, T.F.; Alam, R.I.; Shaikh, S.; Tarkistani, M.A.M. Advanced Nanoparticles in Combating Antibiotic Resistance: Current Innovations and Future Directions. J. Nanotheranostics 2025, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dube, E.; Okuthe, G.E. Silver Nanoparticle-Based Antimicrobial Coatings: Sustainable Strategies for Microbial Contamination Control. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, S.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.C.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles: Antibacterial Activity and Toxicity Mechanism. Nano-Micro Lett. 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, S.; Das, D.K.; Kaur, J.; Kumar, A.; Ubaidullah, M.; Hasan, M.; Yadav, K.K.; Gupta, R.K. Transition metal-based nanoparticles as potential antimicrobial agents: Recent advancements, mechanistic, challenges, and future prospects. Discov. Nano 2023, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Patel, J.; Lee, S.-H.; McCallum, M.; Tyagi, A.; Yan, M.; Shea, K.J. Synthetic polymer nanoparticle–polysaccharide interactions: A systematic study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 2681–2690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholtz, L.; Tavernaro, I.; Eckert, J.G.; Lutowski, M.; Geiβler, D.; Hertwig, A.; Hidde, G.; Bigall, N.C.; Resch-Genger, U. Influence of nanoparticle encapsulation and encoding on the surface chemistry of polymer carrier beads. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, X.; Xie, Q.; Sun, Y. Advances in nanomaterial-based targeted drug delivery systems. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1177151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singireddy, A.R.; Pedireddi, S.R. Advances in lopinavir formulations: Strategies to overcome solubility, bioavailability, and stability challenges. Prospect. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 22, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coates, J. Interpretation of Infrared Spectra: A Practical Approach. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry; Meyers, R.A., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2000; pp. 10881–10882. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, J.I.; Newbury, D.E.; Echlin, P.; Joy, D.C.; Romig, A.D.; Lyman, C.E.; Fiori, C.; Lifshin, E. Scanning Electron Microscopy and X-Ray Microanalysis: A Text for Biologists, Materials Scientists, and Geologists, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H. Preparation, Characterization and Application of Polysaccharide-Based Metallic Nanoparticles: A Review. Polymers 2017, 9, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; O’Donnell, K.; Sutton, D.A.; Nalim, F.A.; Summerbell, R.C.; Padhye, A.A.; Geiser, D.M. Members of the Fusarium solani Species Complex That Cause Infections in Both Humans and Plants Are Common in the Environment. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 2186–2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, J.F.; Summerell, B.A. The Fusarium Laboratory Manual; Blackwell Publishing: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jalšenjak, N.; Topolovec-Pintarić, S.; Đermić, E.; Bujan, M.; Jurić, S. Encapsulation of Biological and Chemical Agents for Plant Nutrition and Protection: Chitosan/Alginate Microcapsules Loaded with Copper Cations and Trichoderma viride. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8073–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokale, V.; Jitendra, N.; Yogesh, S.; Gokul, K. Chitosan reinforced alginate controlled release beads of losartan potassium: Design, formulation and in vitro evaluation. J. Pharm. Investig. 2014, 44, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouda, S.M. Antifungal Activity of Silver and Copper Nanoparticles on Two Plant Pathogens, Alternaria alternata and Botrytis cinerea. Res. J. Microbiol. 2014, 9, 34–42. Available online: https://scialert.net/abstract/?doi=jm.2014.34.42 (accessed on 10 July 2025). [CrossRef]

- Martinko, K.; Ivanković, S.; Đermić, E.; Đermić, D. In vitro antifungal effect of phenylboronic and boric acid on Alternaria alternata. Arch. Ind. Hyg. Toxicol. 2022, 73, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.M.; Yu, W.T.; Liu, X.D.; He, X.; Wang, W.X.; Ma, J. Chemical method of breaking the cell-loaded sodium alginate/chitosan microcapsules. Chem. J. Chin. Univ.-Chin. 2004, 25, 1342–1346. Available online: http://www.cjcu.jlu.edu.cn/EN/Y2004/V25/I7/1342 (accessed on 5 July 2025).

- Zhang, X.F.; Liu, Z.G.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murthy, K.R.S.; Raghu, G.K.; Binnal, P. Zinc Oxide Nanostructured Material for Sensor Application. J. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021, 5, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, S.; Awan, M.S.; Farrukh, M.A.; Naidu, R.; Khan, S.A.; Rafique, N.; Ali, S.; Hayat, I.; Hussain, I.; Khan, M.Z. In-vivo (Albino Mice) and in-vitro Assimilation and Toxicity of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles in Food Materials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2022, 17, 4073–4085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussain, M.; Ansari, M.A.; Mir, F.A. Preparation, characterization and cooling performance of ZnO based Nanofluids. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, M.; Mishra, D.; Sahoo, G. A review on green synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raut, N.S.; Deshmukh, P.R.; Umekar, M.J.; Kotagale, N.R. Zinc cross-linked hydroxamated alginates for pulsed drug release. Int. J. Pharm. Investig. 2013, 3, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reig-Vano, B.; Huck-Iriart, C.; de la Flor, S.; Trojanowska, A.; Tylkowski, B.; Giamberini, M. Structural and mechanical analysis on mannuronate-rich alginate gels and xerogels beads based on Calcium, Copper and Zinc as crosslinkers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzoubi, F.Y.; Al-zou’by, J.; Theban, S.K.; Alqadi, M.K.; Al-Khateeb, H.M.; AlSharo, E.S. Size, stability, and aggregation of citrates-coated silver nanoparticles: Contribution of background electrolytes. Nanotechnol. Environ. Eng. 2021, 6, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizi, S.; Shahri, M.M.; Mohamad, R. Green Synthesis of Zinc Oxide Nanoparticles for Enhanced Adsorption of Lead Ions from Aqueous Solutions: Equilibrium, Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies. Molecules 2017, 22, 831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, I.; Constantin, M.; Solcan, G.; Ichim, D.L.; Rata, D.M.; Horodincu, L.; Solcan, C. Composite Hydrogels with Embedded Silver Nanoparticles and Ibuprofen as Wound Dressing. Gels 2023, 9, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizwan, M.; Yahya, R.; Hassan, A.; Yar, M.; Azzahari, A.D.; Selvanathan, V.; Sonsudin, F.; Abouloula, C.N. pH Sensitive Hy-drogels in Drug Delivery: Brief History, Properties, Swelling, and Release Mechanism, Material Selection and Applica-tions. Polymers 2017, 9, 137, Erratum in Polymers 2017, 9, E225. https://Doi.Org/10.3390/Polym9060225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, L.H.; Panyukov, S.; Rubinstein, M. Hopping Diffusion of Nanoparticles in Polymer Matrices. Macromolecules 2015, 48, 847–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo e Silva, S.H.; Bierhalz, A.C.K.; Moraes, Â.M. Influence of Nanoparticle Content and Cross-Linking Degree on Functional Attributes of Calcium Alginate-ZnO Nanocomposite Wound Dressings. Membranes 2025, 15, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Kao, W.J. Drug release kinetics and transport mechanisms of non-degradable and degradable polymeric deliv-ery systems. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2010, 7, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, W.; Czinkota, I.; Gulyás, M.; Aziz, T.; Hameed, M.K. Development and characterization of slow re-lease N and Zn fertilizer by coating urea with Zn fortified nano-bentonite and ZnO NPs using various binders. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 26, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehri, K.; Salleh, B.; Zakaria, L. Morphological and phylogenetic analysis of Fusarium solani species complex in Malaysia. Microb. Ecol. 2015, 69, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Rodriguez, J.A.; Reyes-Perez, J.J.; Carranza-Patino, M.S.; Herrera-Feijoo, R.J.; Preciado- Rangel, P.; Hernandez-Montiel, L.G. Biocontrol of Fusarium solani: Antifungal Activity of Chitosan and Induction of Defence Enzymes. Plants 2025, 14, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Latge, J.P.; Munro, C.A. The Fungal Cell Wall: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Microbiol Spectr. 2017, 5, 28513415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Yan, F.; Liang, W.; Yang, Q. Zinc exerts antifungal activity against Fusarium pseudograminearum by interfering with ROS accumulation regulated by transcription factor FpYap1. Pest Manag. Sci. 2025, 81, 8179–8190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpinar, I.; Unal, M.; Sar, T. Potential antifungal effects of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) of different sizes against phytopathogenic Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. radicis-lycopersici (FORL) strains. SN Appl. Sci. 2021, 3, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pielesz, A.; Biniaś, D.; Waksmańska, W.; Bobiński, R. Lipid bands of approx. 1740 cm−1 as spectral biomarkers and image of tissue oxidative stress. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 286, 121926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Vargas, J.M.; Echeverry-Cardona, L.M.; Moreno-Montoya, L.E.; Restrepo-Parra, E. Evaluation of Antifungal Activity of Ag Nanoparticles Synthetized by Green Chemistry against Fusarium solani and Rhizopus stolonifera. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterley, A.S.; Laity, P.; Holland, C.; Weidner, T.; Woutersen, S.; Giubertoni, G. Broadband Multidimensional Spectroscopy Identifies the Amide II Vibrations in Silkworm Films. Molecules 2022, 27, 6275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kacuráková, M.; Capek, P.; Sasinková, V.; Wellner, N.; Ebringerová, A. FT-IR study of plant cell wall model compounds: Pectic polysaccharides and hemicelluloses. Carbohydr. Polym. 2000, 43, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, Y.N.; Bach, H. Mechanisms of Antifungal Properties of Metal Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekwomadu, T.I.; Mwanza, M. Fusarium Fungi Pathogens, Identification, Adverse Effects, Disease Management, and Global Food Security: A Review of the Latest Research. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovsky, A.; Nitzan, Y.; Gedanken, A.; Lubart, R. Antifungal activity of ZnO nanoparticles—the role of ROS mediated cell injury. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 105101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subba, B.; Rai, G.B.; Bhandary, R.; Parajuli, P.; Thapa, N.; Kandel, D.R.; Mulmi, S.; Shrestha, S.; Malla, S. Antifungal activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) on Fusarium equiseti phytopathogen isolated from tomato plant in Nepal. Heliyon 2024, 10, e40198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreuter, J. Influence of the surface properties on nanoparticle-mediated transport of drugs to the brain. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2004, 4, 484–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Nanoparticles | Number of Analyzed Particles | Average Particle Height/nm | Standard Deviation/nm |

|---|---|---|---|

| AgNPs | 373 | 3.5 | 5.9 |

| ZnONPs | 140 | 3.5 | 2.0 |

| Formulations | Mean (Wet)/µm | Variance (Wet))/µm | Mean (Dry)/)/µm | Variance (Dry))/µm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formulation 2 | 1816.67 | 449.07 | 871.67 | 169.75 |

| Formulation 3 | 1831.43 | 448.23 | 950.00 | 352.37 |

| Formulation 1 | 2258.33 | 502.41 | 983.33 | 331.16 |

| ALG/Zn | 1710.00 | 411.58 | 535.00 | 224.54 |

| Source of Variation | Sum of Squares (SS) | Degrees of Freedom (DF) | Mean Square (MS) | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between Groups | 996,497.10 | 3 | 332,165.70 | 7.91 | <0.00001 |

| Within Groups | 1,007,658.09 | 24 | 41,986.59 | ||

| Total | 2,004,155.19 | 27 |

| Microparticles | EE/% | LC/mg g−1 | Sw/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALG/Zn | 52.1 ± 0.7 | ||

| Formulation 1 | a 77.9 ± 1.37 | a 1.9 × 10−3 ± 3.2× 10−5 | 63.8 ± 4.5 |

| Formulation 2 | b 98.6 ± 0.76 | b 3.7 × 10−5 ± 7.6 × 10−7 | 42.6 ± 2.9 |

| Formulation 3 | a 64.0 ± 2.51 | a 1.5 × 10−3 ± 2.0 × 10−5 | 42.5 ± 2.7 |

| Formulation 3 | b 98.9 ± 0.95 | b 2.9 × 10−5 ± 0.5 × 10−6 | 42.5 ± 2.7 |

| Formulation | I | II | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k/hn | n | R2 | Ko/t | R2 | ||

| Formulation 1 | fAg | 2.26 | 0.65 | 0.98 | ||

| Formulation 3 | fAg | 5.01 | 0.45 | 0.99 | ||

| Formulation 2 (I) | fZn | 2.39 | 0.36 | 0.99 | ||

| Formulation 2 (II) | fZn | 1.00 | 0.99 | |||

| Formulation 3 (I) | fZn | 2.54 | 0.38 | 0.98 | ||

| Formulation 3 (II) | fZn | 0.80 | 0.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinceković, M.; Živković Genzić, L.; Jalšenjak, N.; Kaliterna, J.; Rezić Meštrović, I.; Majdak, M.; Šegota, S.; Marciuš, M.; Svečnjak, L.; Kos, I.; et al. Antifungal Activity of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles Co-Loaded in Zinc–Alginate Microparticles. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411374

Vinceković M, Živković Genzić L, Jalšenjak N, Kaliterna J, Rezić Meštrović I, Majdak M, Šegota S, Marciuš M, Svečnjak L, Kos I, et al. Antifungal Activity of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles Co-Loaded in Zinc–Alginate Microparticles. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411374

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinceković, Marko, Lana Živković Genzić, Nenad Jalšenjak, Joško Kaliterna, Iva Rezić Meštrović, Mislav Majdak, Suzana Šegota, Marijan Marciuš, Lidija Svečnjak, Ivica Kos, and et al. 2025. "Antifungal Activity of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles Co-Loaded in Zinc–Alginate Microparticles" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411374

APA StyleVinceković, M., Živković Genzić, L., Jalšenjak, N., Kaliterna, J., Rezić Meštrović, I., Majdak, M., Šegota, S., Marciuš, M., Svečnjak, L., Kos, I., Švenda, I., & Martinko, K. (2025). Antifungal Activity of Ag and ZnO Nanoparticles Co-Loaded in Zinc–Alginate Microparticles. Sustainability, 17(24), 11374. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411374