1. Introduction

According to the China Statistical Yearbook 2023, the mortality rate from respiratory diseases among urban residents in 2022 was 0.54‰, accounting for 8.45% of total deaths; the mortality rate from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases was 1.40‰, accounting for 21.71%. These two categories constitute major threats to public health, with mortality rates second only to those of malignant tumors and heart disease. While the traditional energy sector has long served as a driving force of industrialization, it is also the primary source of carbon emissions. The use of fossil fuels, including coal, oil, and natural gas, directly results in large-scale emissions of carbon dioxide and fine particulate matter. Long-term exposure to such pollutants substantially increases the risks of respiratory illnesses, cardiovascular diseases, and other health problems [

1]. In contrast, transitioning to new energy helps reduce regional air pollution, thereby lowering the incidence and mortality of related diseases and improving public health.

Ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being is essential for achieving Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, and the importance of environmental health has gained increasing public recognition. Scholars have suggested optimizing the energy structure by reducing reliance on fossil fuels and increasing the share of renewable and clean energy to keep environmental health [

2]. However, the high cost of new energy and its limited public acceptance, together with the slow progress of technological development, hinder large-scale adoption [

3]. For developing countries, improving the efficiency of traditional energy use while advancing the energy transition has become a realistic strategy to simultaneously achieve economic development and carbon neutrality [

4]. A substantial body of research has examined environmental regulation in heavily polluting industries, covering topics such as technological innovation [

5], industrial restructuring [

6], and social equity [

7]. In line with the “Porter Hypothesis,” moderate environmental regulation has been shown to spur firms to eliminate outdated technologies, encourage green innovation, and reduce pollution through deterrence effects, thereby improving environmental quality. However, excessive regulation may suppress economic growth, particularly in resource-based cities facing structural constraints [

8]. Thus, during the energy transition, on the one hand, traditional energy must be steered toward low-carbon development with attention to social equity; on the other hand, the diffusion of new energy technologies must be accelerated by encouraging firms to increase investment in renewable energy R&D and by improving conversion and storage efficiency to reduce costs.

In theory, the energy transition contributes to improved health outcomes. On one hand, the combustion of fossil fuels generates substantial greenhouse gases and air pollutants, and exposure to these pollutants can adversely affect human health [

9]. On the other hand, the use of cleaner fuels helps improve physical health, which in turn enhances labor productivity and income, thereby also supporting better mental well-being [

10]. However, implementing an energy transition is far from straightforward. Liu and Chao [

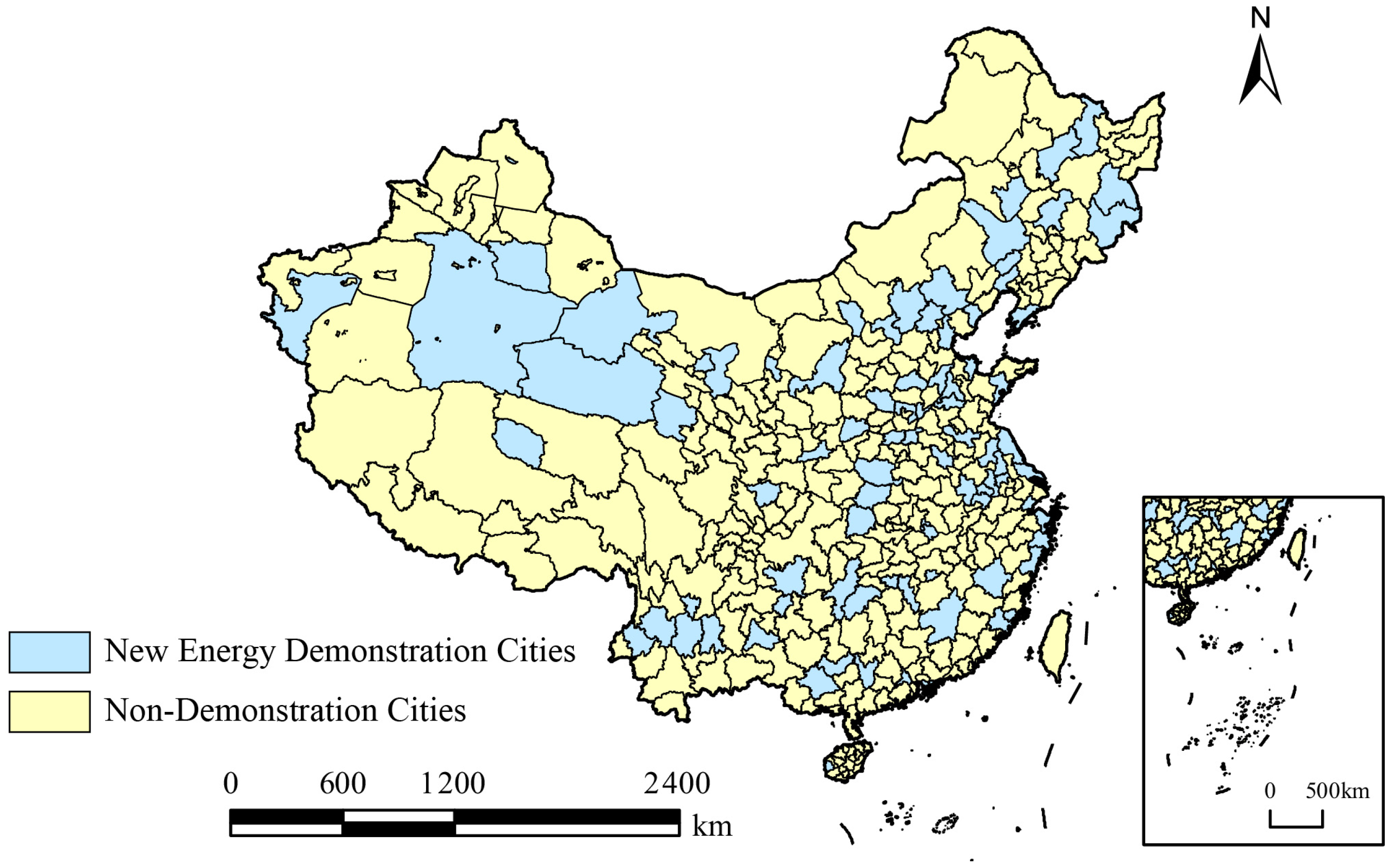

11] analyze energy legislation in 129 countries and find that such policies tend to be more effective in developed countries, whereas developing countries often face high costs of clean energy, immature technologies, and low public acceptance, all of which constrain the effective implementation of ambitious energy policies. China launched the New Energy Demonstration City program (NEDCP) in 2014, designating 81 cities to pilot the development of clean energy sources such as solar, wind, and biomass. Although existing studies have examined the program’s effects on emission reductions [

12] and clean energy consumption [

13], it remains unclear whether the policy has effectively advanced the energy transition and, in turn, generated health benefits for residents.

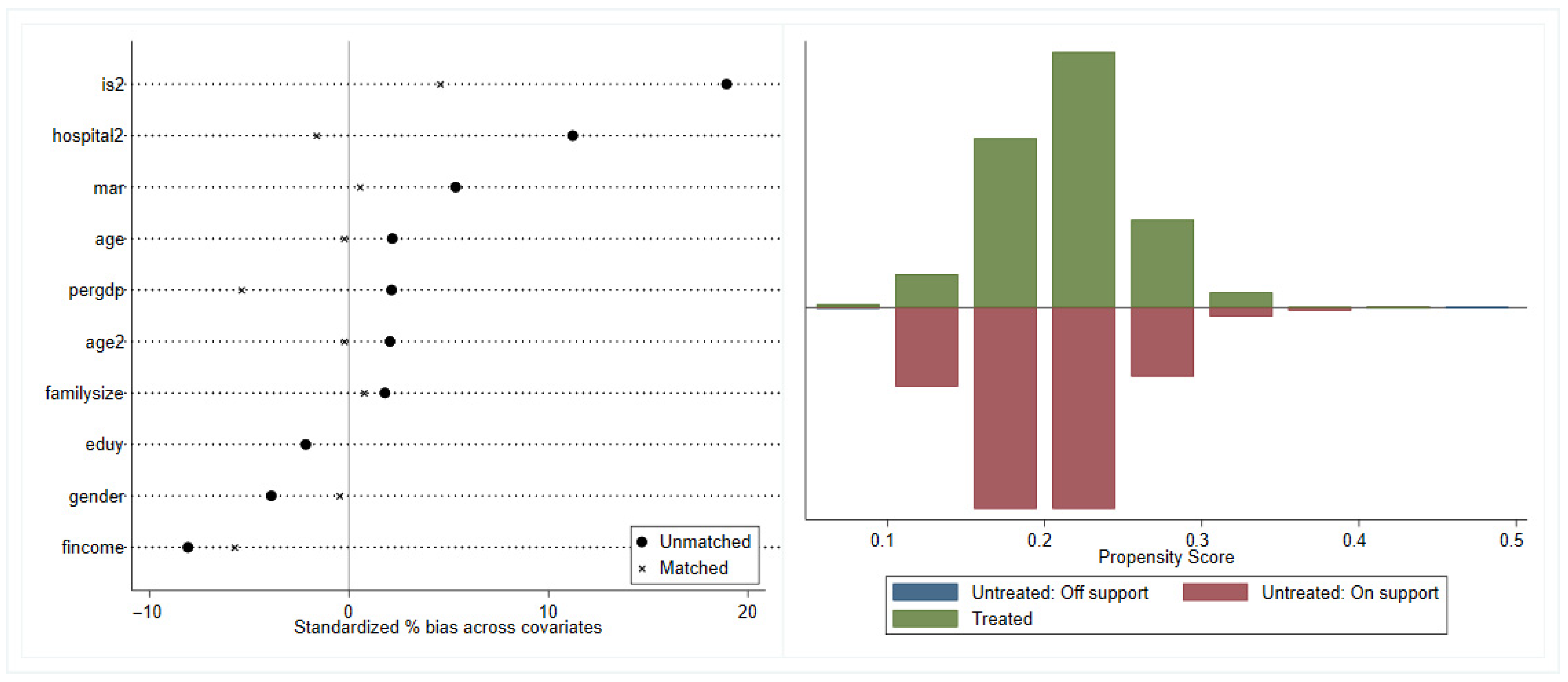

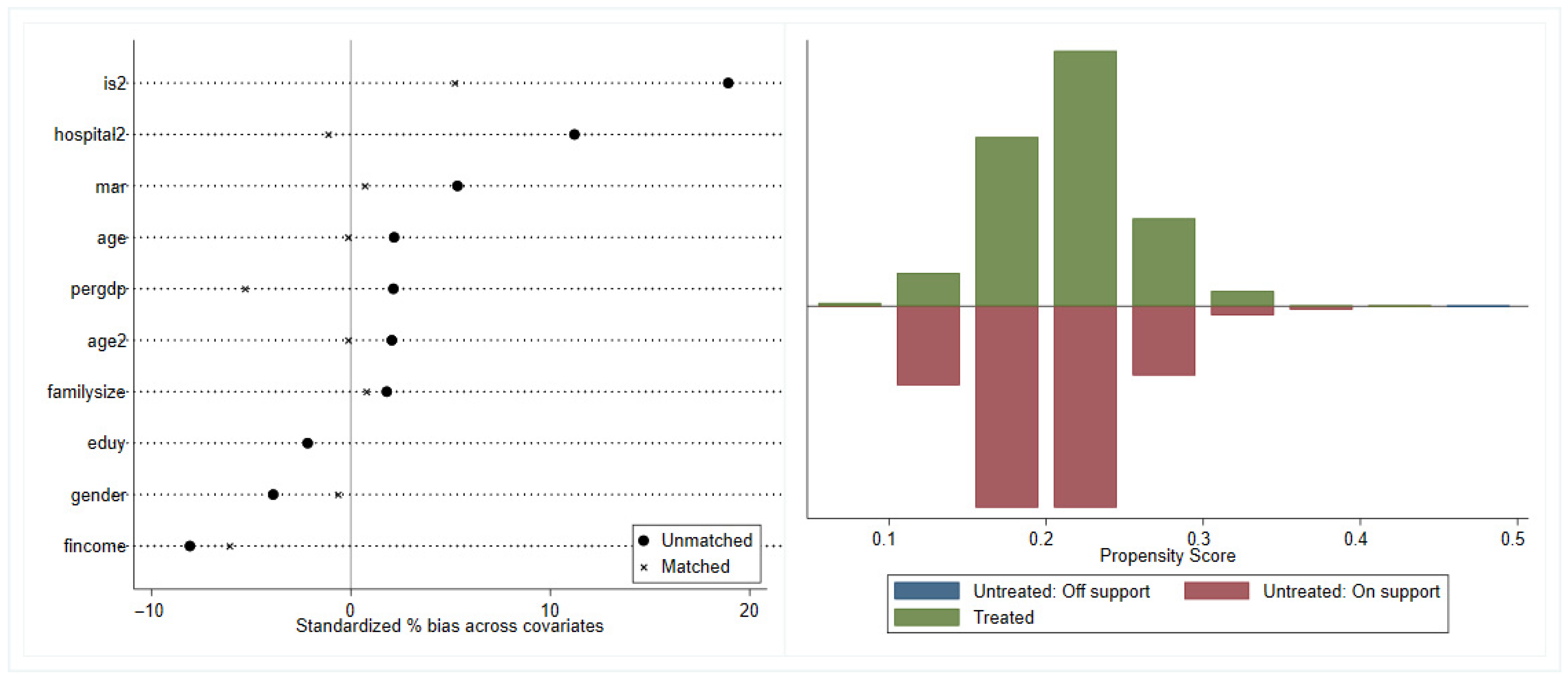

Using NEDCP program as a quasi-natural experiment, this study employs panel data from the 2010–2022 China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) to examine the impact of the energy transition on residents’ health. We further investigate the mediating role of environmental quality improvements and the moderating effects of carbon prices and environmental regulation. In addition, we reveal the heterogeneity of health benefits across population groups and regions.

The contributions of this paper are threefold. First, we provide an exogenous proxy of the energy transition. Existing studies typically measure the energy transition using indicators such as renewable energy consumption [

14] or the share of renewable energy in total primary energy supply [

15], but these measures are strongly correlated with production scale and therefore subject to substantial endogeneity. By exploiting China’s NEDCP program as a quasi-natural experiment, we overcome the endogeneity concerns associated with conventional measures of the energy transition. Second, we examine the effects of the energy transition on health outcomes and underlying mechanisms, which has received limited attention in the literature. Prior studies have primarily focused on macro-level outcomes such as energy efficiency and industrial upgrading, while the micro-level responses of firms and households, including changes in energy adoption behaviors and the resulting health consequences, remain underexplored. Leveraging detailed energy consumption data and panel datasets at the city, firm, and individual levels, we document that the energy transition promotes cleaner energy use, improves environmental quality, and enhances residents’ health. Finally, we extend our analyses to a health equity perspective and uncover broader distributional benefits. Heterogeneity analyses show that the health gains from the energy transition are more pronounced for vulnerable groups and in resource-constrained and economically disadvantaged regions. Given that these populations generally exhibit poorer baseline health, our findings suggest that the energy transition not only generates aggregate health benefits but also contributes to greater health equity.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

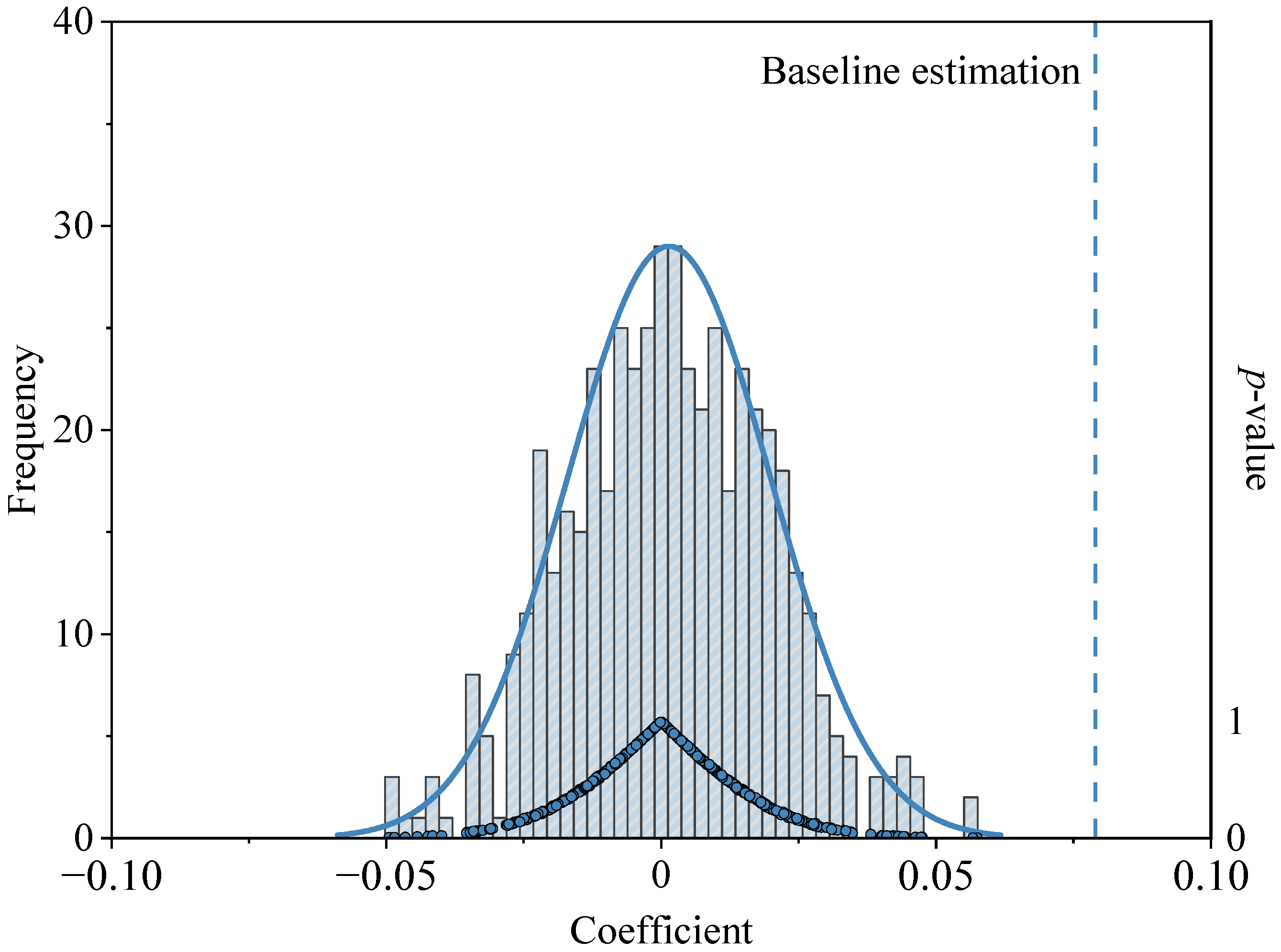

Promoting the energy transition has become a crucial strategy for mitigating air pollution and improving public health. Understanding how the energy transition reshapes market dynamics is therefore essential for clarifying the mechanisms of new energy development, accelerating the low-carbon transition, and enhancing health outcomes. This study exploits the NEDCP program as a quasi-natural experiment and applies a difference-in-differences approach calibrated with data from the CFPS to examine the impact of the energy transition on household health and its underlying mechanisms. The results show that the NEDCP program significantly improves residents’ self-rated health, primarily through optimizing the energy structure and enhancing environmental quality. These findings remain robust after accounting for potential endogeneity and conducting multiple sensitivity checks. We further investigate how market costs and governmental regulation shape the effectiveness of energy transition. Increases in carbon prices and stricter environmental regulation are found to amplify the positive health effects of the NEDCP program. Finally, heterogeneity analyses across populations and regions reveal that the health benefits are most pronounced among vulnerable groups including smokers, individuals without regular exercise, and older adults, who face inherent health disadvantages. Similarly, cities with higher resource dependence, weaker economic foundations, and insufficient environmental protection exhibit lower baseline health levels but gain greater benefits from the NEDCP program. Overall, these findings indicate that promoting clean energy transition is an effective pathway to fostering coordinated regional development and reducing inequalities in environmental public health services. These results also offer meaningful insights for other developing countries seeking to advance energy transition and improve public health outcomes.

Based on these findings, several policy implications emerge. First, implement region-specific support to maximize health returns. NEDCP program resources should be strategically allocated toward resource-based and economically underdeveloped cities with higher potential health gains. Dedicated funding and technical assistance should be provided to accelerate their energy structure transformation, thereby realizing the greatest possible improvements in public health. Second, strengthen market-based mechanisms to ensure a sustainable transition. Policies should promote competition within the new energy market and enhance coordination with carbon trading and other market-oriented environmental instruments. Building such policy synergy can reduce long-term dependence on administrative subsidies and help establish market-driven, endogenous momentum for clean energy substitution. Third, incorporate public health benefits into the evaluation system of energy policies. When designing and assessing new energy and related environmental policies, health improvements—such as reduced medical burdens and enhanced well-being—should be treated as core evaluation metrics. Recognizing the substantial social value of energy transition will help strengthen public support and reinforce the legitimacy of clean energy policies.