Intelligent and Sustainable Classification of Tunnel Water and Mud Inrush Hazards with Zero Misjudgment of Major Hazards: Integrating Large-Scale Models and Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement Method Based on SMOTE

2.1.1. Problem Description

2.1.2. Introduction of Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement Method

2.2. Construction of Hazard Classification Model Based on Large-Scale Models

2.2.1. Dataset Description

- (1)

- WH

- (2)

- RQD

- (3)

- WYP

- (4)

- Rock stratum occurrence (RSO)

- (5)

- Aquifer thickness (AT)

- (6)

- Unfavorable geology (UG)

2.2.2. The Construction of Intelligent Classification Model Based on RoBERTa

- (1)

- Introduction of RoBERTa model

- (2)

- Design of weighted cross entropy loss function

2.3. Evaluating Indicator

3. Engineering Application and Result Analysis

3.1. Engineering Background Introduction

3.1.1. Project Profile

3.1.2. Sample Set Construction and Analysis

3.2. Analysis of the Prediction Results of the Proposed Model

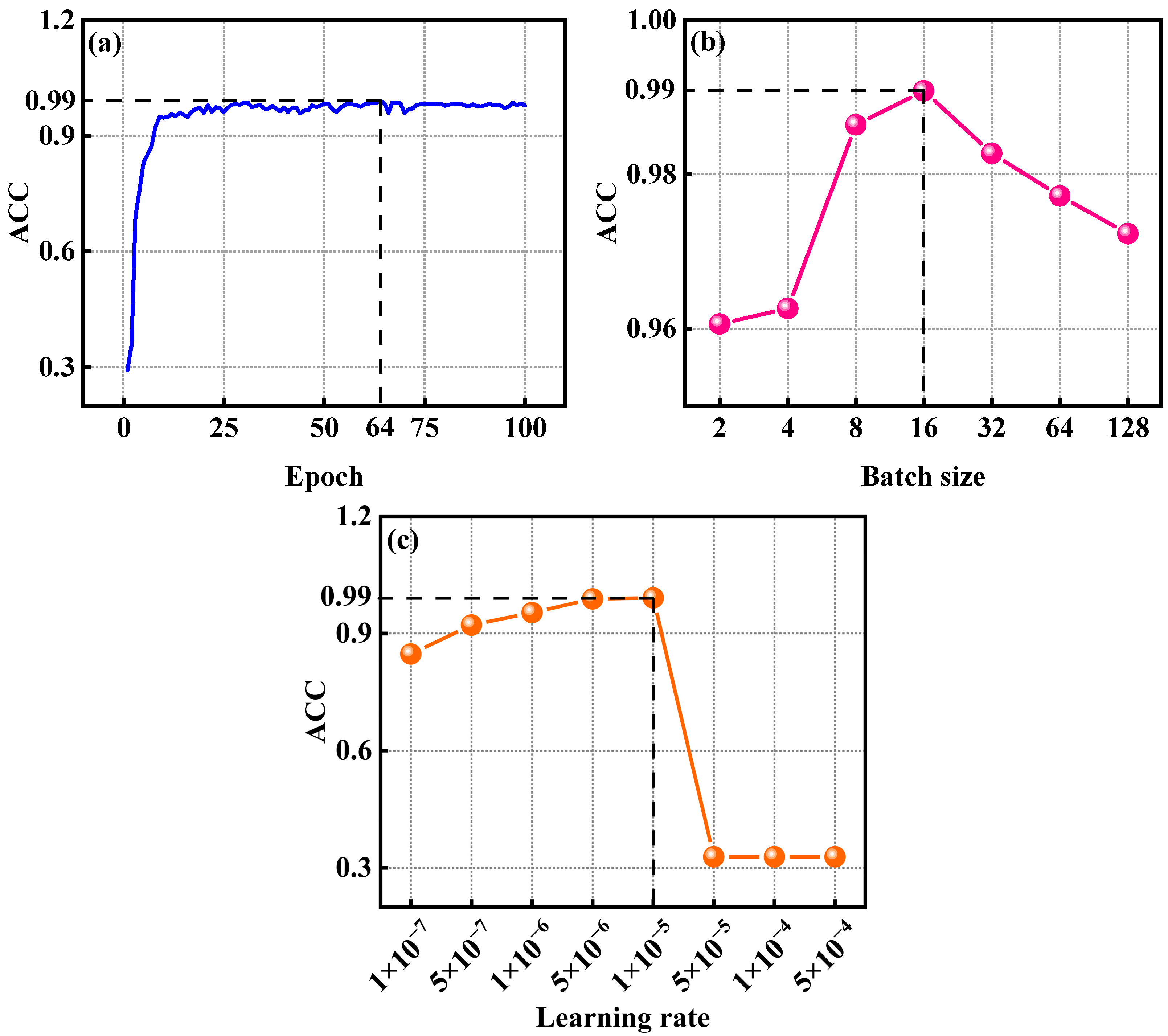

3.2.1. Model Training and Parameter Optimization

3.2.2. Model Comparatively Analysis

3.2.3. Effectiveness Analysis of Model Improvement

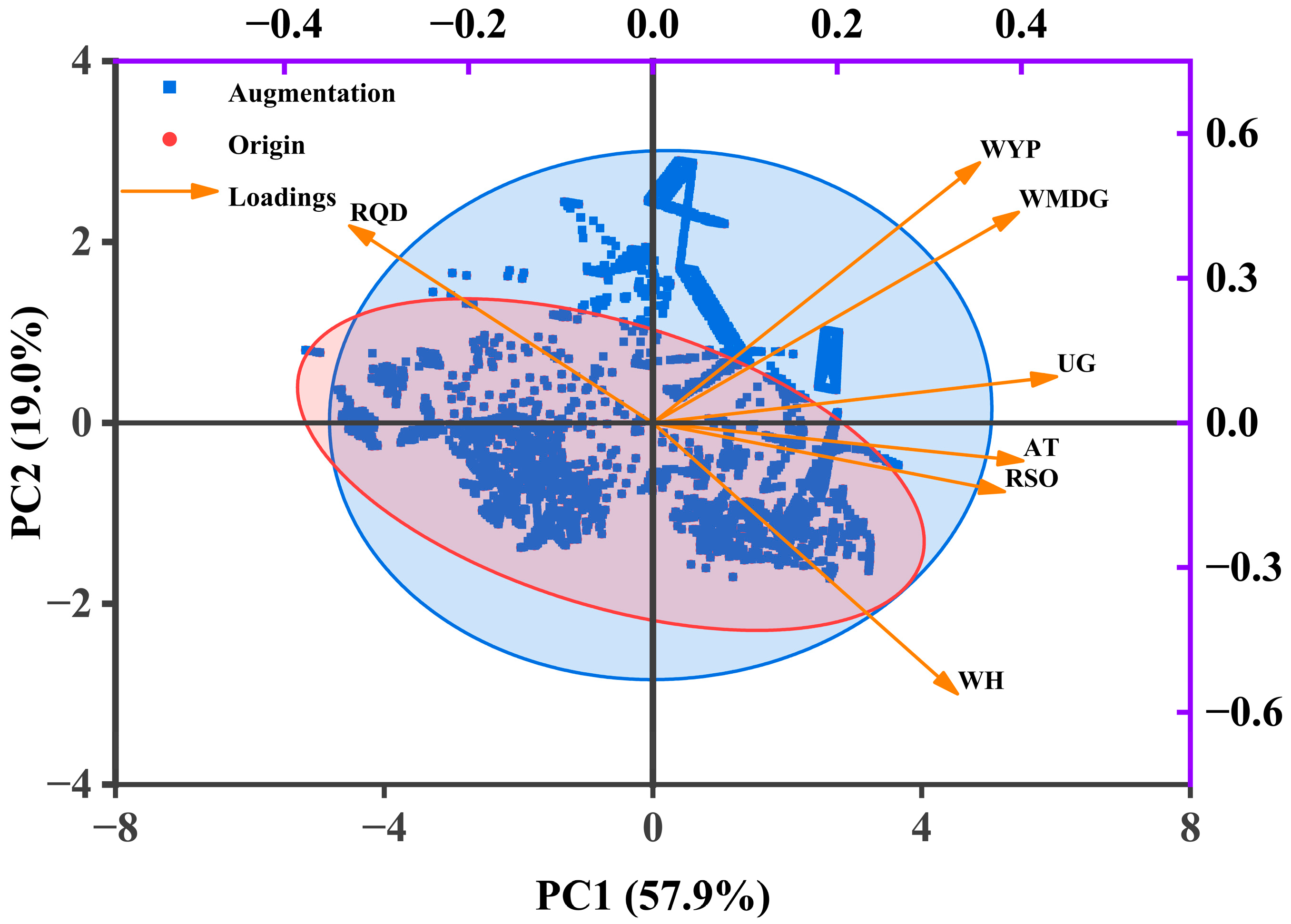

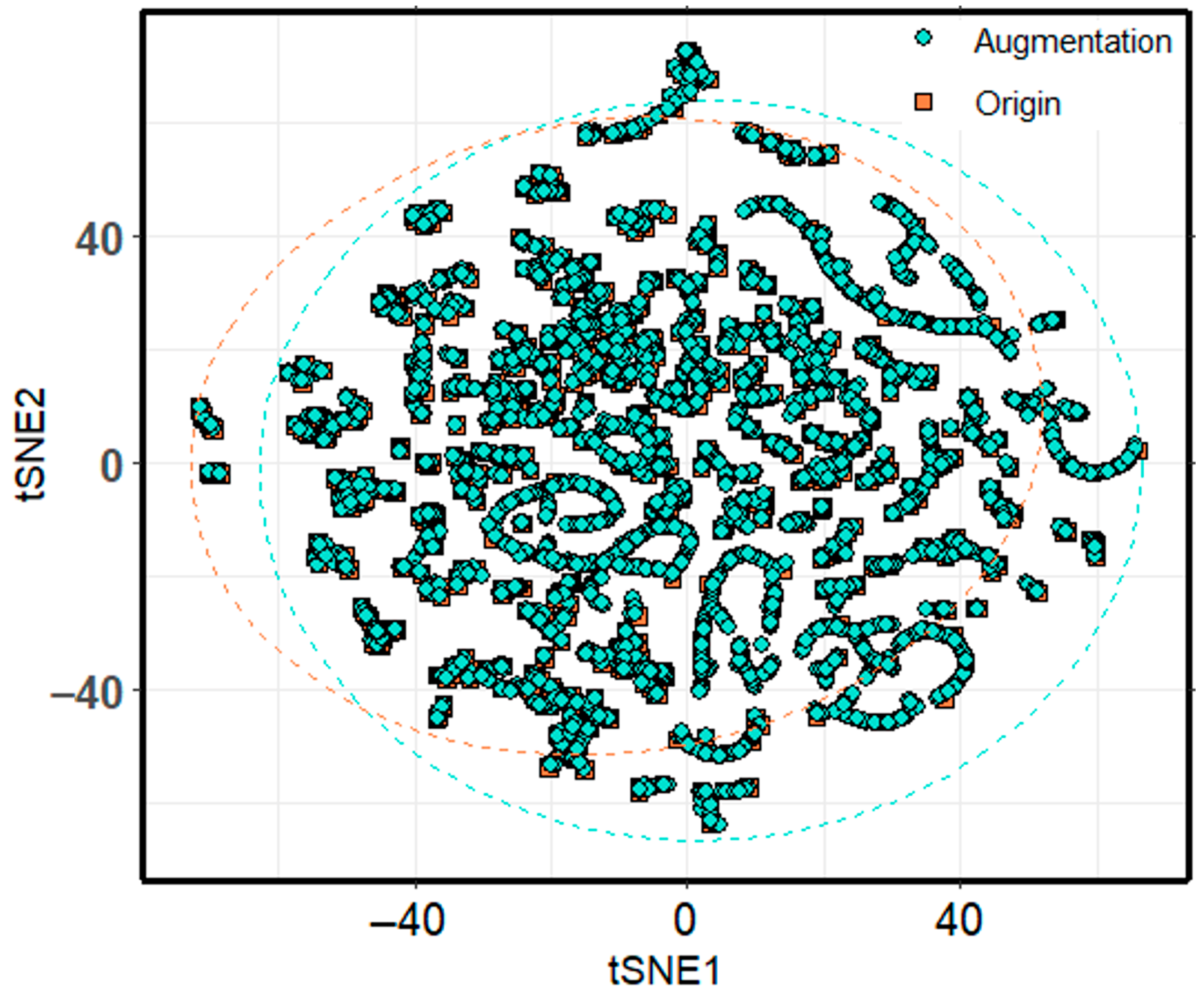

3.3. Analysis of Data Enhancement Effect

3.3.1. Analysis of Enhanced Data Distribution Characteristics

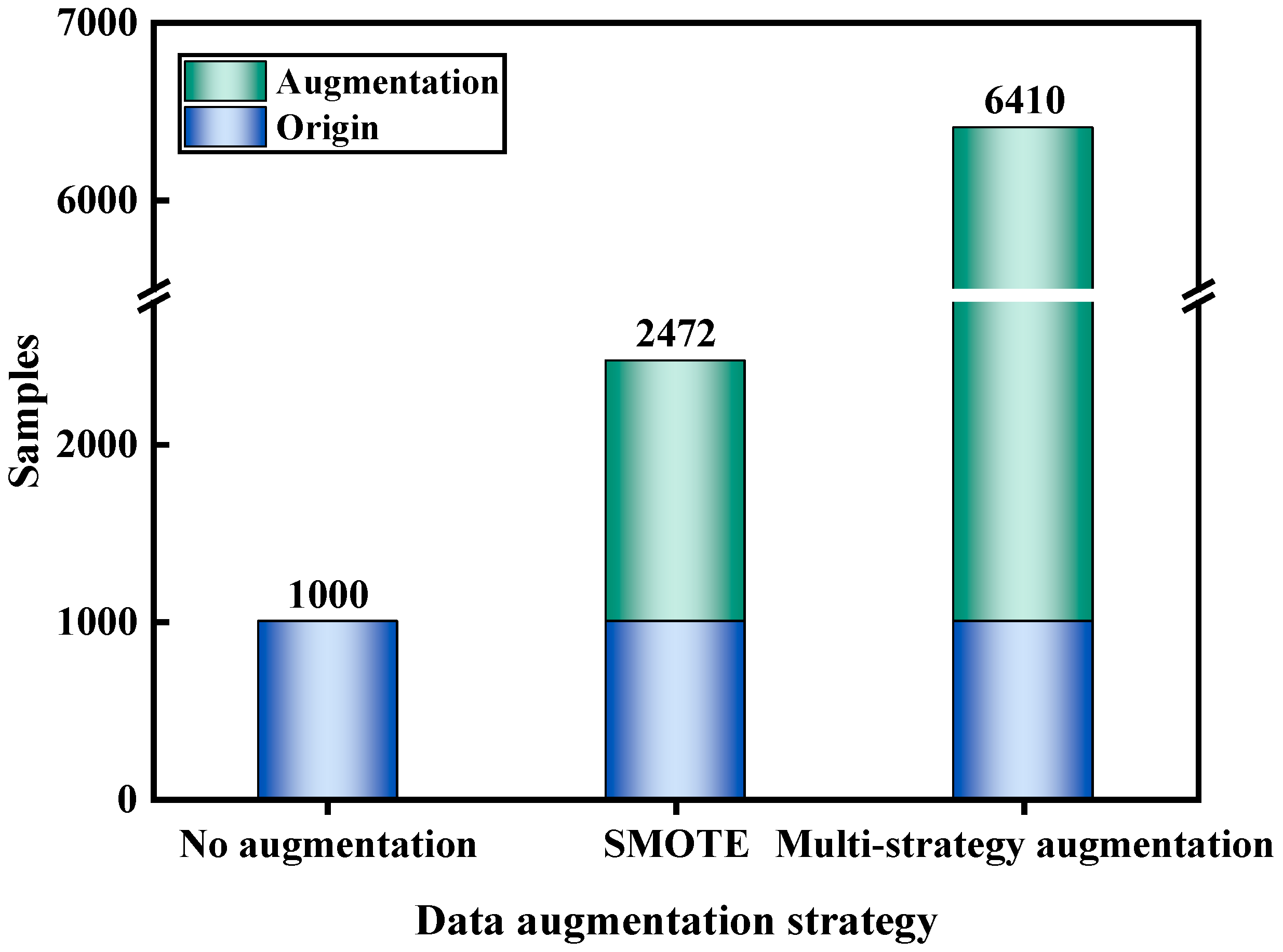

3.3.2. Effectiveness Analysis of Data Augmentation Strategy

3.3.3. Analysis of Model Performance Improvement Effect After Data Enhancement

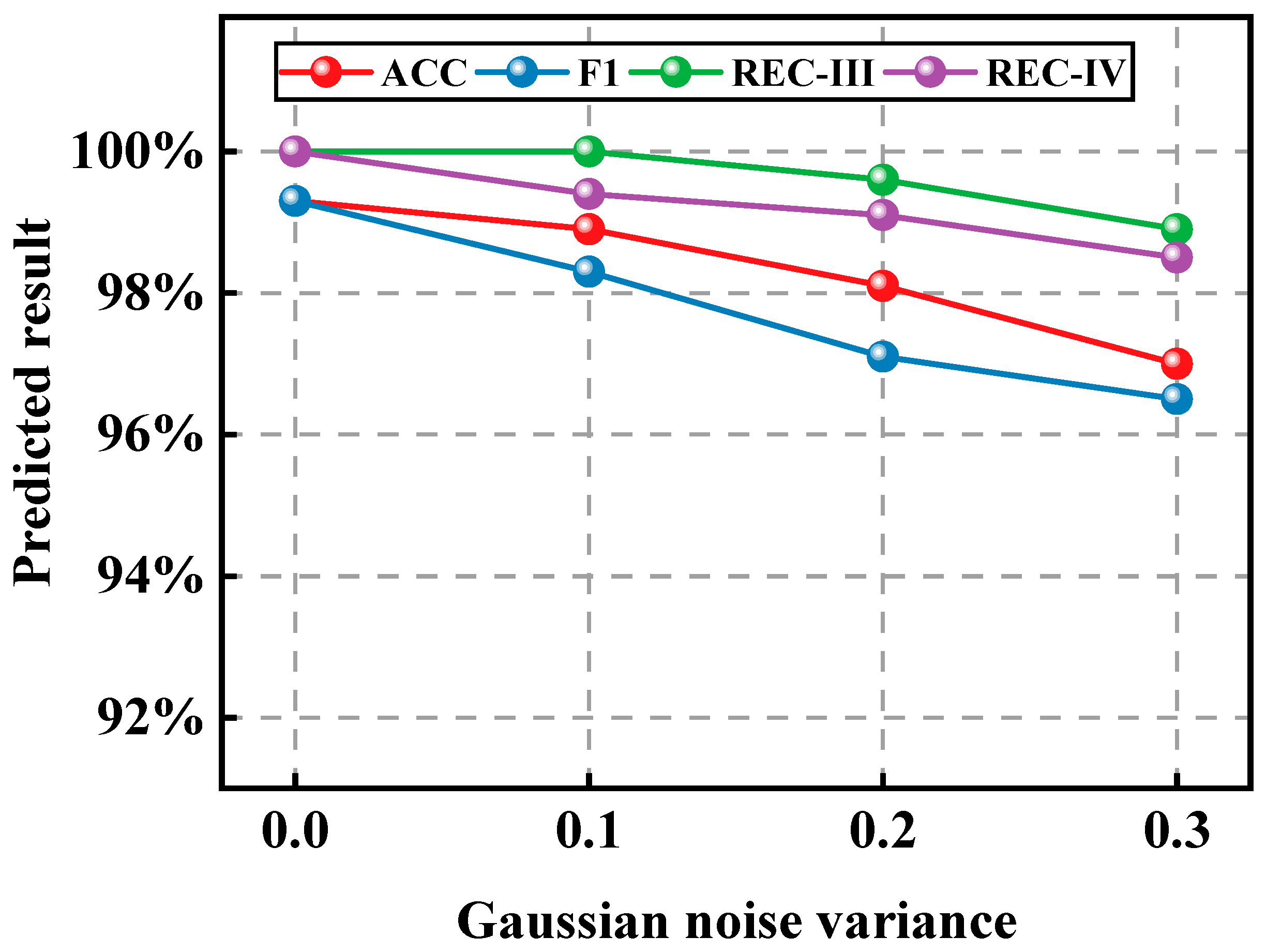

3.4. Model Robustness Analysis

4. Conclusions and Outlook

- (1)

- Expansion of sample space through multi-strategy data augmentation: By integrating SMOTE, ADASYN, and Borderline-SMOTE, the proposed multi-strategy data augmentation method expands the dataset by 6.4 times and improves model ACC by 22.26%. This approach achieves density balancing and local feature enhancement, effectively addressing the issue of low prediction accuracy in tunnel water and mud inrush hazard classification caused by insufficient samples. It provides a generalizable solution for small-sample challenges in engineering applications.

- (2)

- Specialized large-scale models for water and mud inrush prediction: This study fine-tunes the pre-trained language model RoBERTa using a tunnel water and mud inrush hazard classification dataset, transforming its “language understanding ability” into “numerical prediction capability” to enable intelligent hazard classification. Engineering application results show that, compared to nine other machine learning models, the proposed model achieves an ACC of 99.26% and an F1W of 99.25%, demonstrating superior prediction accuracy and strong robustness.

- (3)

- Zero-misclassification strategy for major hazard classification: The RoBERTa model is optimized using a weighted cross-entropy loss function, with a hierarchical weight allocation strategy designed to enhance the model’s learning capability for major hazards. Experimental results indicate that this method maintains classification accuracy for minor hazards while achieving zero misclassification for major hazards. Specifically, with PRE-I and PRE-II at 99.33% and 99.34%, REC-III and REC-IV both reach 100%, and HRMC remains at 0.00. This approach effectively balances classification accuracy with engineering safety requirements, significantly enhancing the model’s practicality and reliability in real-world hazard prevention and control.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, S.; Li, L.; Cheng, S.; Yang, J.; Jin, H.; Gao, S.; Wen, T. Study on an improved real-time monitoring and fusion prewarning method for water inrush in tunnels. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 112, 103884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Feng, Z.; Yang, S.; Qin, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, Y. Safety risk perception and control of water inrush during tunnel excavation in karst areas: An improved uncertain information fusion method. Autom. Constr. 2024, 163, 105421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Shen, Z.; Cao, L.; Mi, J.; Li, J.; Zhao, Y.; Mu, H.; Liu, L.; Dai, C. Water-sand inrush risk assessment method of sandy dolomite tunnel and its application in the Chenaju tunnel, southwest of China. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2023, 14, 2196369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, F.; Yin, X.; Geng, F. Study on the risk assessment of water inrush in karst tunnels based on intuitionistic fuzzy theory. Geomat. Nat. Hazards Risk 2019, 10, 1070–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Cao, Z.; Sun, W.; Fumagalli, A.; Fu, X.; Wu, Z.; Wu, K. Numerical simulation of the fluid-solid coupling mechanism of water and mud inrush in a water-rich fault tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 131, 104796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Pei, J.; Cao, C.; Liu, X.; Huang, Y.; Mei, G. Geological investigation and treatment measures against water inrush hazard in karst tunnels: A case study in Guiyang, southwest China. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2022, 124, 104491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, P. Research on disaster-causing characteristics of water and mud inrush and combined prevention-control measures in water-rich sandstone and slate interbedded strata tunnel. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2025, 156, 106250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Xu, G.; Yasufuku, N.; Yu, Z.; Liu, P.; Wang, J. Risk assessment of water inrush in karst tunnels based on two-class fuzzy comprehensive evaluation method. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jing, H.; Yu, L.; Su, H.; Luo, N. Set pair analysis for risk assessment of water inrush in karst tunnels. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2017, 76, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, S. Risk assessment model of tunnel water inrush based on improved attribute mathematical theory. J. Cent. South Univ. 2018, 25, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zheng, W.; Xu, C.; Chen, S. An improved extension system for assessing risk of water inrush in tunnels in carbonate karst terrain. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 2049–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wu, J. A multi-factor comprehensive risk assessment method of karst tunnels and its engineering application. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2019, 78, 1761–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, S.; Qiu, D.; Su, M.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, B.; Tao, Y. Water inrush risk assessment for an undersea tunnel crossing a fault: An analytical model. Mar. Georesour. Geotechnol. 2019, 37, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Chen, H.; Huang, W.; Meng, G. Dynamic evaluation method of the EW–AHP attribute identification model for the tunnel gushing water disaster under interval conditions and applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6661609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, H.; Zhang, N. Risk assessment of water inrush accident during tunnel construction based on FAHP–I–TOPSIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 449, 141744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, L.; Hu, A.; Kai, S.; Fan, C. Risk assessment of karst water inrush in tunnel engineering based on improved game theory and uncertainty measure theory. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Ding, H.; Huang, F.; Wei, Q.; Li, T.; Wen, T. Ideal point interval recognition model for dynamic risk assessment of water inrush in karst tunnel and its application. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 1875–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Yin, X.; Gao, F.; Pan, Y. Surrounding rock squeezing classification in underground engineering using a hybrid paradigm of generative artificial intelligence and deep ensemble learning. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Intelligent classification model of surrounding rock of tunnel using drilling and blasting method. Undergr. Space 2021, 6, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, G.; Hou, K.; Sun, H. Rock burst intensity-grade prediction based on comprehensive weighting method and Bayesian optimization algorithm–improved-support vector machine model. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Dong, Z.; Li, X. Physics-informed and data-driven machine learning of rock mass classification using prior geological knowledge and TBM operational data. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Wei, Y.; Yang, Y. A novel identification technology and real-time classification forecasting model based on hybrid machine learning methods in mixed weathered mudstone–sand–pebble formation. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 153, 106545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, K.; Qin, Q. A rockburst prediction model based on extreme learning machine with improved Harris Hawks optimization and its application. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 134, 104978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Ma, C.; Li, T.; Yan, W.; Shirani Faradonbeh, R. Real-time classification model for tunnel surrounding rocks based on high-resolution neural network and structure–optimizer hyperparameter optimization. Comput. Geotech. 2024, 168, 106155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; He, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhu, G. Classification of rock fragments produced by tunnel boring machine using convolutional neural networks. Autom. Constr. 2021, 125, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Fan, W.; Guo, H.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q. Surrounding rock classification from onsite images with deep transfer learning based on EfficientNet. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2024, 18, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Xue, Y.; Li, G.; Su, M.; Qiu, D.; Kong, F.; Zhou, B. Using Bayesian network and intuitionistic fuzzy analytic hierarchy process to assess the risk of water inrush from fault in subsea tunnel. Geomech. Eng. 2021, 27, 605–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Lu, Y.; He, J.; Lu, B.; Wang, K. Bayesian-network-based predictions of water inrush incidents in soft rock tunnels. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2024, 28, 5934–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Niu, M.; Wan, F.; Lu, J.; Wang, Y.; Yan, X.; Zhou, C. Hazard prediction of water inrush in water-rich tunnels based on random forest algorithm. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jibril, E.C.; Tantug, A.C. ANEC: An Amharic named entity corpus and transformer based recognizer. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 15799–15815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, A.; Naseem, U.; Rahimi Azghadi, M. Large language models vs human for classifying clinical documents. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2025, 195, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Lv, C.; Ding, Y.; Chang, H.; Xie, Q. An image enhancement algorithm to improve road tunnel crack transfer detection. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 348, 128583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B. Applying data augmentation technique on blast-induced overbreak prediction: Resolving the problem of data shortage and data imbalance. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Zhang, D.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Y. Automatic recognition of tunnel lining elements from GPR images using deep convolutional networks with data augmentation. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P. Generative adversarial network for optimization of operational parameters based on shield posture requirements. Autom. Constr. 2024, 165, 105553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gong, C.; Wu, W. Automatic tunnel lining crack detection via deep learning with generative adversarial network-based data augmentation. Undergr. Space 2023, 9, 140–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Song, Y.; Yang, A.; Lv, K.; Jiang, H.; Dong, C. Accurate classification of tunnel lining cracks using lightweight ShuffleNetV2-1.0-SE model with DCGAN-based data augmentation and transfer learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Sun, H.; Tao, J.; Qin, C.; Xiao, D.; Jin, Y.; Liu, C. A multi-stage data augmentation and AD-ResNet-based method for EPB utilization factor prediction. Autom. Constr. 2023, 147, 104734. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Huang, H.; Cohn, A.G.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, M. Machine learning-based classification of rock discontinuity trace: SMOTE oversampling integrated with GBT ensemble learning. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2022, 32, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wang, X.; Huang, X.; Yin, X. Prediction model of rock mass class using classification and regression tree integrated AdaBoost algorithm based on TBM driving data. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 106, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Luo, W.; Jia, F.; Li, S.; Pang, H. Serviceability evaluation of highway tunnels based on data mining and machine learning: A case study of continental United States. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 142, 105418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuwal, T.B.; Panthi, K.K.; Basnet, C.B. Machine learning approach for rock mass classification with imbalanced database of TBM tunnelling in Himalayan geology. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 58, 11293–11318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Li, H.; Chen, C.; Liu, X. Rapid stability assessment of barrier dams based on the extreme gradient boosting model. Nat. Hazards 2025, 121, 3047–3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Guo, S.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Qiu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X. A novel multi-scale standardized index analyzing monthly to sub-seasonal drought-flood abrupt alternation events in the Yangtze River basin. J. Hydrol. 2024, 633, 130999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, T.; Guan, C.; Liu, L.; Han, M. Prediction for rock conditions in a tunnel area using advanced geological drilling predictions based on multiwavelet analysis and modified evidence reasoning. Int. J. Geomech. 2024, 24, 04024027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, K.; Tan, X.; Liu, S.; Lu, Z.; Hou, X.; Wang, Q. Prediction of slope failure probability based on machine learning with genetic-ADASYN algorithm. Eng. Geol. 2025, 346, 107885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Fang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Huang, W. Towards automated lithology classification in NATM tunnel: A data-driven solution for multi-dimensional imbalanced data. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2024, 58, 2349–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Meng, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, H.; Guan, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Wu, Z. Prediction of flood risk levels of urban flooded points though using machine learning with unbalanced data. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ren, B.; Guan, T.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Wang, K.; Huang, J. A hybrid cluster-borderline SMOTE method for imbalanced data of rock groutability classification. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Q/CR 9217-2015; Technical Specification for Geology Forecast of Railway Tunnel. China Railway Publishing House Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Huang, S.; Wei, C. A BERT-based deontic logic learner. Inf. Process. Manag. 2023, 60, 103374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y. A BERT-based multi-semantic learning model with aspect-aware enhancement for aspect polarity classification. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 4609–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briskilal, J.; Subalalitha, C.N. An ensemble model for classifying idioms and literal texts using BERT and RoBERTa. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 102756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kang, S. Common sense-based reasoning using external knowledge for question answering. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 227185–227192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Jiang, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Huang, J. Research on automatic pilot repetition generation method based on deep reinforcement learning. Front. Neurorobot. 2023, 17, 1285831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín, A.; Huertas-Tato, J.; Huertas-García, Á.; Villar-Rodríguez, G.; Camacho, D. FacTeR-Check: Semi-automated fact-checking through semantic similarity and natural language inference. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2022, 251, 109265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ott, M.; Goyal, N.; Du, J.; Joshi, M.; Chen, D.; Levy, O.; Lewis, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Stoyanov, V. RoBERTa: A robustly optimized BERT pretraining approach. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.S.I.; Nazarova, A.; Jamjoom, M.M.; Ignatov, D.I. Multilingual hope speech detection: A robust framework using transfer learning of fine-tuning RoBERTa model. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2023, 35, 101736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areshey, A.; Mathkour, H. Exploring transformer models for sentiment classification: A comparison of BERT, RoBERTa, ALBERT, DistilBERT, and XLNet. Expert Syst. 2024, 41, e13701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, J.; Green, R.C. Cost aware LSTM model for predicting hard disk drive failures based on extremely imbalanced SMART sensors data. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.; Wookey, S. The real-world-weight cross-entropy loss function: Modeling the costs of mislabeling. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4806–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhou, M.; Zhang, D.; Huang, H.; Zhang, F. Quantification of water inflow in rock tunnel faces via convolutional neural network approach. Autom. Constr. 2021, 123, 103526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Hong, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhao, M.; Wang, D. Intelligent prediction method for underbreak extent in underground tunnelling. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2024, 176, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demetgul, M.; Zheng, Q.; Tansel, I.N.; Fleischer, J. Monitoring the misalignment of machine tools with autoencoders after they are trained with transfer learning data. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 128, 3357–3373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Curtò, J.; de Zarzà, I.; Roig, G.; Calafate, C.T. Signature and log-signature for the study of empirical distributions generated with GANs. Electronics 2023, 12, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asre, S.; Anwar, A. Synthetic energy data generation using time variant generative adversarial network. Electronics 2022, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Indicator | Unit | Min–Max | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inputs | WH | m | 11–141 | 77.26 | 29.06 |

| RQD | % | 9–92 | 37.36 | 17.00 | |

| WYP | m3·h−1·m−1 | 0.1–11.7 | 4.11 | 1.98 | |

| RSO | ° | 10–88 | 37.73 | 11.44 | |

| AT | m | 0–36 | 13.81 | 7.16 | |

| UG | — | 3–5 | 4.37 | 0.57 | |

| Output | WMIHC | — | 1–4 | 2.05 | 0.66 |

| Name | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | AdamW |

| Learning rate | 1 × 10−5 |

| β1 | 0.9 |

| β2 | 0.999 |

| Weight decay | 0.01 |

| Dropout | 0.1 |

| Warm-up steps | 500 |

| Max sequence length | 128 |

| Epoch | 64 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Model | ACC/% | F1W/% | F1M/% | REC/% | HRMC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class III | Class IV | |||||

| SVM | 77.57 | 72.90 | 61.47 | 73.48 | 89.29 | 0.32 |

| RF | 97.04 | 96.91 | 95.10 | 99.57 | 100.00 | 0.11 |

| DT | 95.56 | 95.53 | 93.48 | 96.09 | 98.87 | 0.21 |

| LR | 69.32 | 66.39 | 57.91 | 66.09 | 80.08 | 0.45 |

| LGBM | 97.29 | 97.19 | 95.52 | 99.13 | 100.00 | 0.14 |

| GBT | 95.26 | 94.98 | 92.12 | 98.04 | 100.00 | 0.15 |

| XGB | 97.10 | 97.00 | 95.28 | 98.70 | 99.81 | 0.18 |

| KNN | 97.04 | 96.87 | 95.02 | 99.78 | 100.00 | 0.08 |

| AutoInt | 73.26 | 73.05 | 70.94 | 90.00 | 51.88 | 0.63 |

| Proposed | 99.26 | 99.25 | 98.87 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Model | ACC/% | F1M/% | PRE/% | REC/% | HRMC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | ||||

| Original RoBERTa | 99.08 | 98.69 | 99.78 | 96.17 | 99.13 | 99.81 | 0.15 |

| Optimized RoBERTa | 99.26 | 98.87 | 99.33 | 99.42 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 0.00 |

| Model | ACC/% | F1W/% | REC/% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class III | Class IV | |||

| SVM | −4.1 | −7.45 | +1.48 | +89.29 |

| RF | +10.04 | +10.24 | +22.3 | +50 |

| DT | +13.89 | +13.36 | +27.91 | +48.87 |

| LR | −10.68 | −13.02 | +0.18 | +30.08 |

| LGB | +10.96 | +11.09 | +21.86 | 0 |

| GBT | +8.26 | +8.2 | +20.77 | 0 |

| XGB | +10.77 | +10.83 | +28.25 | +1.55 |

| KNN | +10.71 | +10.7 | +22.51 | +72 |

| AutoInt | −2.74 | +5.08 | +90 | +51.88 |

| Proposed | +22.26 | +22.33 | +38.64 | +81 |

| Weight Vector (I, II, III, IV) | ACC | REC-III and REC-IV | F1W |

|---|---|---|---|

| [1, 1, 1, 1] | 96.75% | 96.2%, 96.8% | 96.74% |

| [1, 1, 2, 2] | 98.05% | 98.5%, 98.1% | 98.04% |

| [1, 1, 3, 3] (Proposed) | 99.26% | 100%, 100% | 99.25% |

| [1, 1, 5, 5] | 99.18% | 100%, 100% | 99.17% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yao, X.; Huang, M.; Shi, F.; Yu, L. Intelligent and Sustainable Classification of Tunnel Water and Mud Inrush Hazards with Zero Misjudgment of Major Hazards: Integrating Large-Scale Models and Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411286

Yao X, Huang M, Shi F, Yu L. Intelligent and Sustainable Classification of Tunnel Water and Mud Inrush Hazards with Zero Misjudgment of Major Hazards: Integrating Large-Scale Models and Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411286

Chicago/Turabian StyleYao, Xiayi, Mingli Huang, Fashun Shi, and Liucheng Yu. 2025. "Intelligent and Sustainable Classification of Tunnel Water and Mud Inrush Hazards with Zero Misjudgment of Major Hazards: Integrating Large-Scale Models and Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411286

APA StyleYao, X., Huang, M., Shi, F., & Yu, L. (2025). Intelligent and Sustainable Classification of Tunnel Water and Mud Inrush Hazards with Zero Misjudgment of Major Hazards: Integrating Large-Scale Models and Multi-Strategy Data Enhancement. Sustainability, 17(24), 11286. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411286