Is the Mediterranean Diet Affordable in Türkiye? A Household-Level Cost Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

- ○

- High consumption of plant-based foods: abundant intake of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and seeds, providing fibre, antioxidants, and phytochemicals.

- ○

- Olive oil as the main source of added fat: a key symbol of the diet, providing monounsaturated fatty acids and bioactive phenolic compounds.

- ○

- o Moderate consumption of animal products: including fish and seafood several times per week, moderate amounts of dairy (preferably fermented forms such as yoghurt and cheese), and limited red and processed meats.

- ○

- Preference for seasonal, local, and minimally processed foods, respecting traditional culinary methods and sustainability principles.

- ○

- Moderate wine consumption (in adults, during meals, and within cultural norms), though not essential for health benefits.

- ○

- Social and cultural dimensions: meals are shared, reflecting hospitality, community ties, and intergenerational knowledge transfer, all of which contribute to overall well-being [4].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reference Household Definition

2.2. Determining the Representative Region

2.3. Development of the Mediterranean Diet Food Basket

2.4. Assessment of Nutritional Adequacy

2.5. Price Data Collection

2.6. Basket Cost Estimation

2.7. Affordability Scenarios and Sensitivity Analysis

For the studied household (two adults, one 16-year-old adolescent, and one child under 14 years),

S = 1 + (0.5 + 0.5 + 0.3) = 2.3

3. Results

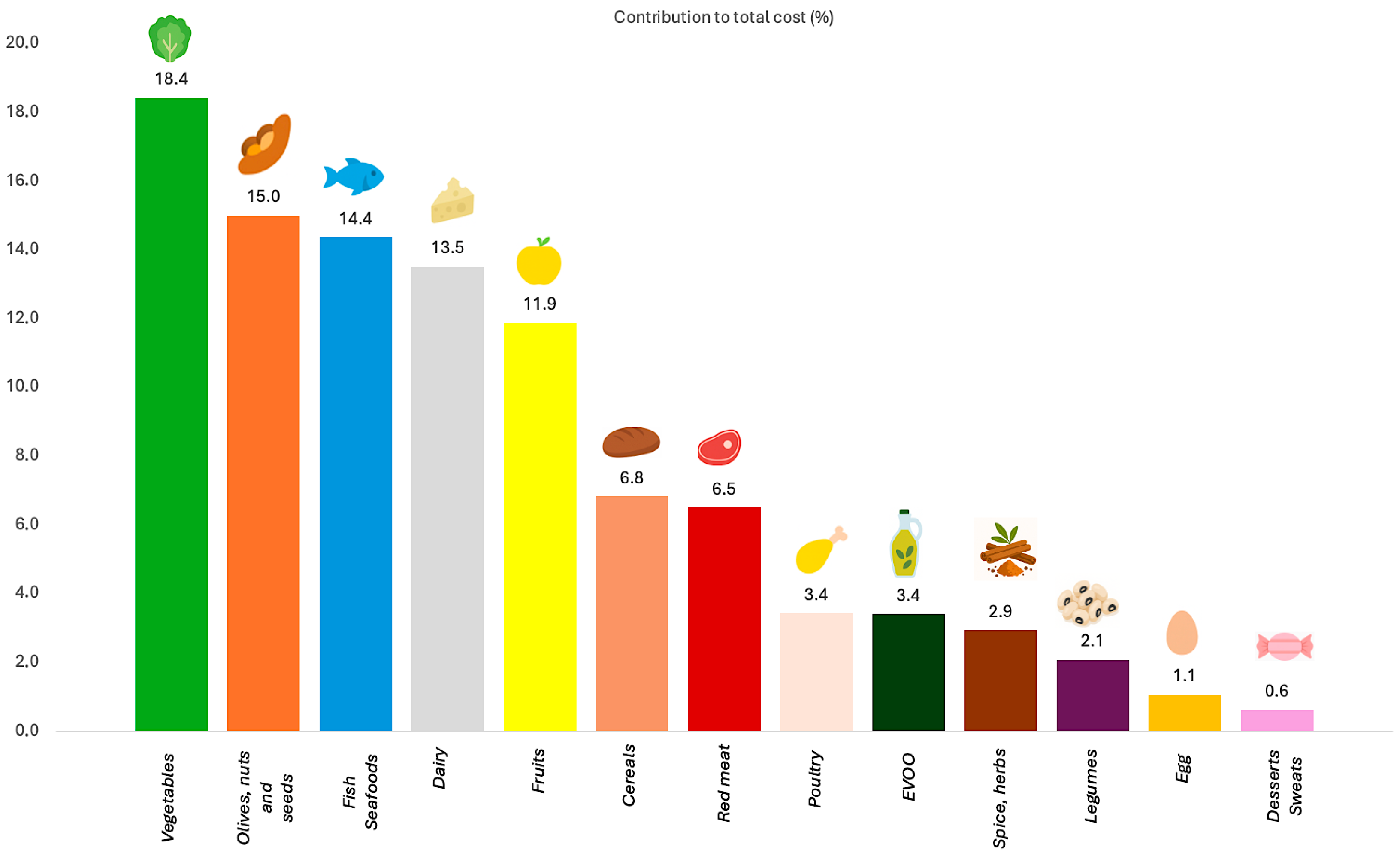

3.1. Estimated Cost of the Mediterranean Diet Food Basket and Price Distribution of Food Groups

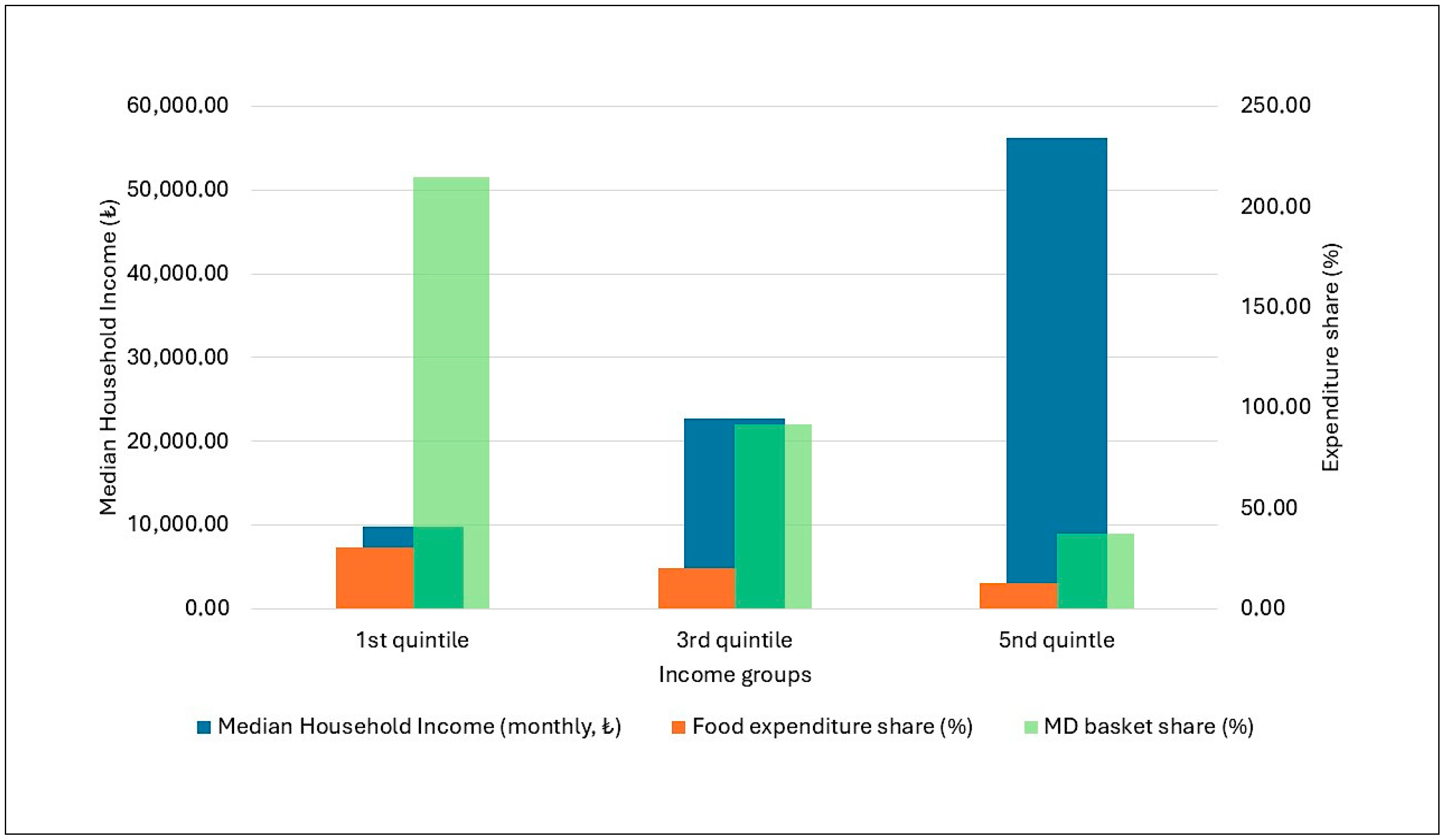

3.2. Affordability of the Mediterranean Diet Food Basket

4. Discussion

4.1. Portion Adaptation and Cost Implications

4.2. Cross-Country Comparison of Findings

4.3. Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Food | Unit | M1 | M2 | M3 | Open-Air Market | Halk Ekmek | Average Cost | Quantity/Day | Daily Cost | Monthly Cost | Group Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Black Pepper | tl/kg | 600 | 600 | 600 | 600 | 10 | 6.00 | 182.40 | 614.2 | ||

| Cinnamon | tl/kg | 276.5 | 276.67 | 887.78 | 480.317 | 10 | 4.80 | 146.02 | |||

| Cumin | tl/kg | 300 | 366.67 | 366.67 | 344.447 | 10 | 3.44 | 104.71 | |||

| Mint | tl/kg | 288 | 350 | 350 | 329.333 | 10 | 3.29 | 100.12 | |||

| Thyme | tl/kg | 266 | 266.66 | 266.67 | 266.443 | 10 | 2.66 | 81.00 | |||

| Apple | tl/kg | 29.5 | 42.5 | 44.95 | 20 | 34.237 | 487.5 | 16.69 | 507.40 | 2484.2 | |

| Quince | tl/kg | 44.5 | 49.5 | 49.95 | 50 | 48.487 | 151.25 | 7.33 | 222.95 | ||

| Kiwi | tl/kg | 72.5 | 89 | 84.95 | 40 | 71.612 | 232.5 | 16.65 | 506.16 | ||

| Tangerine | tl/kg | 34 | 32 | 39.95 | 25 | 32.737 | 325 | 10.64 | 323.45 | ||

| Orange | tl/kg | 34.75 | 29.5 | 49.95 | 30 | 36.05 | 260 | 9.37 | 284.94 | ||

| Pomegranate | tl/kg | 89.95 | 89.95 | 50 | 46.65 | 227.5 | 10.61 | 322.63 | |||

| Banana | tl/kg | 67 | 69.5 | 69.95 | 50 | 64.113 | 162.5 | 10.42 | 316.72 | ||

| Scallions | tl/kg | 39 | 139.8 | 150 | 109.6 | 150 | 16.44 | 499.78 | 3854.7 | ||

| Spinach | tl/kg | 141.42 | 39.95 | 25 | 68.79 | 180 | 12.38 | 376.42 | |||

| Lettuce | tl/kg | 79.8 | 69.87 | 50 | 66.557 | 147 | 9.78 | 297.43 | |||

| Cabbage | tl/kg | 29.5 | 19.95 | 20 | 23.15 | 180 | 4.17 | 126.68 | |||

| Leek | tl/kg | 95 | 48.95 | 30 | 57.983 | 180 | 10.44 | 317.28 | |||

| Parsley | tl/kg | 99.8 | 66.3 | 50 | 72.033 | 90 | 6.48 | 197.08 | |||

| Carrot | tl/kg | 29.5 | 42.14 | 55.95 | 20 | 36.897 | 330 | 12.18 | 370.16 | ||

| Red radish | tl/kg | 38.5 | 35.95 | 30 | 34.817 | 180 | 6.27 | 190.52 | |||

| Red cabbage | tl/kg | 59.9 | 19.95 | 40 | 39.95 | 290 | 11.59 | 352.20 | |||

| Mushrooms | tl/kg | 122.5 | 148.33 | 174.8 | 50 | 123.907 | 180 | 22.30 | 678.02 | ||

| Onion | tl/kg | 18.75 | 18.75 | 23.95 | 17 | 19.612 | 473.333 | 9.28 | 282.21 | ||

| Garlic | tl/kg | 199 | 223.75 | 249.95 | 250 | 230.675 | 18 | 4.15 | 126.23 | ||

| Potato | tl/kg | 11.75 | 10.75 | 10.75 | 15 | 12.062 | 111 | 1.34 | 40.70 | ||

| Olive oil | tl/L | 174.5 | 174.5 | 289.95 | 212.983 | 0.11 | 23.43 | 712.22 | 712.2 | ||

| Whole grain bread | tl/kg | 82.5 | 82.14 | 122.11 | 50 | 84.187 | 400 | 33.68 | 1023.72 | 1428.5 | |

| Whole pasta | tl/kg | 25.5 | 27.5 | 74.37 | 42.457 | 55 | 2.34 | 70.99 | |||

| Brown rice | tl/kg | 35 | 35 | 25.75 | 31.917 | 55 | 1.76 | 53.36 | |||

| Couscous | tl/kg | 48.5 | 48.5 | 49.9 | 48.967 | 55 | 2.69 | 81.87 | |||

| Bulgur | tl/kg | 23 | 23 | 22.78 | 22.927 | 140 | 3.21 | 97.58 | |||

| Oats | tl/kg | 71.4 | 78.94 | 109.5 | 86.613 | 38.333 | 3.32 | 100.93 | |||

| Almonds | tl/kg | 563 | 563.33 | 563.33 | 563.22 | 30 | 16.90 | 513.66 | 3139.3 | ||

| Walnuts | tl/kg | 563 | 563.33 | 777.5 | 634.61 | 30 | 19.04 | 578.76 | |||

| Hazelnuts | tl/kg | 563 | 463.33 | 463.33 | 496.55 | 30 | 14.90 | 452.86 | |||

| Pistachios | tl/kg | 663 | 663.33 | 663.33 | 663.22 | 30 | 19.90 | 604.86 | |||

| Peanuts | tl/kg | 139 | 167.6 | 186.5 | 164.367 | 35 | 5.75 | 174.89 | |||

| Sunflower seeds | tl/kg | 93.75 | 90 | 99.5 | 94.4167 | 80 | 7.55 | 229.62 | |||

| Black olives | tl/kg | 94.75 | 102.5 | 175 | 124.083 | 155 | 19.23 | 584.68 | |||

| Cow’s milk (semi-skimmed) | tl/L | 31 | 31 | 31.25 | 31.083 | 200 | 6.22 | 188.99 | 2828.3 | ||

| Yoghurt (semi-skimmed) | tl/L | 31.8 | 36 | 37.5 | 35.1 | 550 | 19.31 | 586.87 | |||

| Cheese (white) | tl/kg | 176.5 | 162.5 | 239 | 192.667 | 195 | 37.57 | 1142.13 | |||

| Cheese (curd) | tl/kg | 87 | 87 | 47.9 | 73.967 | 150 | 11.10 | 337.29 | |||

| Kefir | tl/L | 43.5 | 43.5 | 59.5 | 48.833 | 200 | 9.77 | 296.91 | |||

| Ayran | tl/L | 22.5 | 27.67 | 27.67 | 25.947 | 350 | 9.08 | 276.07 | |||

| Chicken | tl/kg | 65 | 92.5 | 99 | 85.5 | 165 | 14.11 | 428.87 | 716.9 | ||

| Turkey | tl/kg | 379 | 379 | 379 | 379 | 25 | 9.48 | 288.04 | |||

| Fish | tl/kg | 170 | 138 | 199.95 | 169.317 | 543 | 91.94 | 2794.94 | 3007.7 | ||

| Tuna | tl/kg | 279 | 279.69 | 281.09 | 279.927 | 25 | 7.00 | 212.74 | |||

| Red meat | tl/kg | 320 | 487.5 | 497.5 | 435 | 102.857 | 44.74 | 1360.18 | 1360.2 | ||

| Chicken eggs | tl/adet | 5.75 | 99.13 | 4.83 | 36.57 | 200.286 | 7.32 | 222.66 | 222.7 | ||

| Lentils | tl/kg | 40 | 40 | 39.8 | 39.933 | 36 | 1.44 | 43.70 | 433.8 | ||

| Chickpeas | tl/kg | 51 | 51.75 | 51.75 | 51.5 | 67 | 3.45 | 104.90 | |||

| Dried beans | tl/kg | 59.75 | 65 | 59.75 | 61.5 | 62 | 3.81 | 115.92 | |||

| Kidney beans | tl/kg | 80 | 81.25 | 151.9 | 104.383 | 36 | 3.76 | 114.24 | |||

| Black-eyed peas | tl/kg | 74.2 | 65 | 36 | 58.4 | 31 | 1.81 | 55.04 | |||

| Turkish delight | tl/kg | 180.55 | 180.55 | 319.9 | 227 | 6 | 1.36 | 41.40 | 127.6 | ||

| Halva | tl/kg | 90 | 109 | 109 | 102.667 | 5.3 | 0.54 | 16.54 | |||

| Molasses | tl/kg | 98.8 | 83 | 84.38 | 88.7277 | 21.446 | 1.90 | 57.85 | |||

| Granulated sugar | tl/kg | 33 | 34.9 | 34.9 | 34.267 | 11.3 | 0.39 | 11.77 |

| Nutrients | Girl | Requirement | Adequacy | Adolescent Boy | Requirement | Adequacy | Man | Requirement | Adequacy | Woman | Requirement | Adequacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 1394.70 | 1398 | 100% | 2982.20 | 2755 | 108% | 2678.60 | 2758 | 97% | 1894.90 | 1977 | 96% |

| Protein (%) | 31 | 5–20 | 248% | 24 | 10–20 | 192% | 23 | 10–20 | 184% | 23 | 14–20 | 184% |

| Fat (%) | 32 | 20–35 | 116% | 29 | 20–35 | 105% | 31 | 20–35 | 113% | 33.00 | 20–35 | 120% |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 38 | 45–60 | 72% | 46 | 45–60 | 88% | 46 | 45–60 | 88% | 43.00 | 45–60 | 82% |

| Dietary fibre (g) | 29 | 14 | 207% | 74.70 | 21 | 356% | 69.60 | 25 | 278% | 48.80 | 25 | 195% |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 1164.10 | 300 | 388% | 3452.10 | 750 | 460% | 3353.80 | 750 | 447% | 2017.50 | 750 | 269% |

| Vitamin B1/ Thiamin (mg) | 1.40 | 0.40 | 350% | 2.80 | 0.40 | 700% | 2.70 | 0.40 | 675% | 2.00 | 0.40 | 500% |

| Vitamin B2/ Riboflavin (mg) | 2.40 | 0.70 | 343% | 4.00 | 1.60 | 250% | 3.40 | 1.60 | 213% | 2.30 | 1.60 | 144% |

| Vitamin B6/ Pyridoxine (mg) | 2.10 | 0.70 | 300% | 4.30 | 1.70 | 253% | 3.90 | 1.70 | 229% | 2.70 | 1.60 | 169% |

| Folate, total (µg) | 422.20 | 140 | 302% | 945 | 330 | 286% | 805.50 | 330 | 244% | 581.90 | 330 | 176% |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 154.40 | 30 | 515% | 386.20 | 100 | 386% | 385.60 | 110 | 351% | 264.50 | 95 | 278% |

| Sodium (mg) | 1756.60 | 1300 | 135% | 4228.10 | 2000 | 211% | 2559.50 | 2000 | 128% | 1940.80 | 2000 | 97% |

| Potassium (mg) | 3662.30 | 1100 | 333% | 7728.10 | 3500 | 221% | 7126.10 | 3500 | 204% | 4843.90 | 3500 | 138% |

| Calcium (mg) | 1163.50 | 800 | 145% | 2083.10 | 1150 | 181% | 1527.80 | 1000 | 153% | 1094.40 | 1000 | 109% |

| Iron (mg) | 16.40 | 7.00 | 234% | 37.90 | 11 | 345% | 35.20 | 11.00 | 320% | 23.60 | 11–16 | 175% |

| Zinc (mg) | 10.20 | 5.50 | 185% | 21.30 | 14.20 | 150% | 17.90 | 9.4–16.3 | 139% | 13.10 | 9.4–16.3 | 102% |

References

- Willett, W.C.; Sacks, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Drescher, G.; Ferro-Luzzi, A.; Helsing, E.; Trichopoulos, D. Mediterranean Diet Pyramid: A Cultural Model for Healthy Eating. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995, 61, 1402S–1406S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M.; Willett, W.C. The Mediterranean Diet and Health: A Comprehensive Overview. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Centre for Advanced Mediterranean Agronomic Studies; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Mediterranean Food Consumption Patterns: Diet, Environment, Society, Economy and Health; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO Chair for the Mediterranean Diet. Resources on Nutrition. Available online: https://mediterraneandietunesco.org/resources/nutrition/ (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- Mattavelli, E.; Olmastroni, E.; Casula, M.; Grigore, L.; Pellegatta, F.; Baragetti, A.; Magni, P.; Catapano, A.L. Adherence to Mediterranean Diet: A Population-Based Longitudinal Cohort Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serra-Majem, L.; Tomaino, L.; Dernini, S.; Berry, E.M.; Lairon, D.; Ngo de la Cruz, J.; Trichopoulou, A. Updating the Mediterranean Diet Pyramid towards Sustainability: Focus on Environmental Concerns. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obeid, C.A.; Gubbels, J.S.; Jaalouk, D.; Kremers, S.P.; Oenema, A. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet among Adults in Mediterranean Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Eur. J. Nutr. 2022, 61, 3327–3344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptou, E.; Tsiami, A.; Negro, G.; Ghuriani, V.; Baweja, P.; Smaoui, S.; Varzakas, T. Gen Z’s Willingness to Adopt Plant-Based Diets: Evidence from Greece, India, and the UK. Foods 2024, 13, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Escobar, C.; Díez, J.; Martínez-García, A.; Bilal, U.; O’Flaherty, M.; Franco, M. Food Availability and Affordability in a Mediterranean Urban Context. Public Health Nutr. 2023, 26, 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaccio, M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; De Gaetano, G.; Iacoviello, L. Challenges to the Mediterranean Diet during Economic Crisis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2016, 26, 1057–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turrell, G.; Kavanagh, A.M. Socio-Economic Pathways to Diet: Modelling Socio-Economic Position and Food Purchasing Behaviour. Public Health Nutr. 2006, 9, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cade, J.; Upmeier, H.; Calvert, C.; Greenwood, D. Costs of a Healthy Diet: UK Women’s Cohort Study. Public Health Nutr. 1999, 2, 505–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.; Whelan, J.; Love, P. Assessing Costs of Healthy vs. Unhealthy Diets: Systematic Review. Curr. Nutr. Rep. 2022, 11, 600–617. [Google Scholar]

- Hoenink, J.C.; Garrott, K.; Jones, N.R.; Conklin, A.I.; Monsivais, P.; Adams, J. Price Disparities between Healthy and Less Healthy Foods in the UK. Appetite 2024, 197, 107290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Headey, D.; Hirvonen, K.; Alderman, H. Estimating Cost and Affordability of Healthy Diets. Food Policy 2024, 126, 102654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, C.N.; Martínez-González, M.A.; Sánchez-Villegas, A.; Alonso, A.; Pimenta, A.M.; Bes-Rastrollo, M. Costs of Mediterranean and western dietary patterns in a Spanish cohort and their relationship with prospective weight change. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 2009, 63, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, H.; Marrugat, J.; Covas, M.I. High Monetary Costs of Dietary Patterns Associated with Lower BMI. Int. J. Obes. 2006, 30, 1574–1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Alemu, R.; Block, S.A.; Headey, D.; Masters, W.A. Cost and Affordability of Nutritious Diets. Food Policy 2021, 99, 101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balagamwala, M.; Kuri, S.; Mejia, J.G.J.; de Pee, S. The Affordability Gap for Nutritious Diets. Glob. Food Secur. 2024, 41, 100757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurostat. Household Expenditure on Food and Non-Alcoholic Beverages. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230201-1 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- TURKSTAT. Household Consumption Expenditures 2023. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Household-Consumption-Expenditures-2023-53801&dil=2 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT. 2024. Available online: https://faostat.fao.org (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- International Olive Council (IOC). World Market of Olive Oil and Table Olives: Data from December 2024. Available online: https://www.internationaloliveoil.org/world-market-of-olive-oil-and-table-olives-data-from-december-2024/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- TURKSTAT. Consumer Price Index September 2025. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Consumer-Price-Index-September-2025-54184&dil=2 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Consumer Prices: OECD Statistical Release. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/data/insights/statistical-releases/2025/11/consumer-prices-oecd-11-2025.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas—Türkiye Data. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/idf-diabetes-atlas-2025/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- WHO Regional Office for Europe. European Regional Obesity Report 2022; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/publications/i/item/9789289057738 (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Yeşildemir, Ö.; Güldaş, M.; Boqué, N.; Calderón-Pérez, L.; Degli Innocenti, P.; Scazzina, F.; Nehme, N.; Abbass, F.A.; de la Feld, M.; Salvio, G.; et al. Adherence to the mediterranean diet among families from four countries in the mediterranean basin. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TÜRK-İŞ Confederation. Hunger and Poverty Line Report, July 2025. Available online: https://www.turkis.org.tr (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Goulding, T.; Lindberg, R.; Russell, C.G. Affordability of Healthy/Sustainable Diets: Australian Case. Nutr. J. 2020, 19, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storms, B.; Goedemé, T.; Van den Bosch, K.; Penne, T.; Schuerman, N.; Stockman, S. Reference Budgets in Europe. Eur. Comm. Rep. 2014, 10, 400190. [Google Scholar]

- TURKSTAT. Income Distribution Statistics 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Income-Distribution-Statistics-2024-53712&dil=2#:~:text=The%20mean%20annual%20household%20disposable,to%20previous%20year%20in%20T%C3%BCrkiye.&text=In%20T%C3%BCrkiye%2C%20the%20mean%20annual,to%20187%20thousand%20728%20TL (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Casas, R.; Ruiz-León, A.M.; Argente, J.; Alasalvar, C.; Bajoub, A.; Bertomeu, I.; Caroli, M.; Castro-Barquero, S.; Crispi, F.; Delarue, J.; et al. A New Mediterranean Lifestyle Pyramid for Children and Youth: A Critical Lifestyle Tool for Preventing Obesity and Associated Cardiometabolic Diseases in a Sustainable Context. Adv. Nutr. 2025, 16, 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TUBER. Türkiye Beslenme Rehberi 2022; Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2022. Available online: https://hsgm.saglik.gov.tr/tr/web-uygulamalarimiz/357.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health. Turkey Nutrition and Health Survey 2017; Republic of Turkey Ministry of Health: Ankara, Türkiye, 2019.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Human Energy Requirements; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Independent Industrialists and Businessmen’s Association (MÜSİAD). Food Retail Sector Report. 2023. Available online: https://dernek.musiad.org.tr/en/new/gida-perakendeciligi-sektor-arastirma-raporu-yayimlandi (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). FAOSTAT: Cost and Affordability of a Healthy Diet (CoAHD) Database; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023; Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/CAHD (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- OECD. Framework for Statistics on Income, Consumption and Wealth; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- TURKSTAT. Poverty and Living Conditions Statistics 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Poverty-and-Living-Conditions-Statistics-2024-53714&dil=2#:~:text=According%20to%20the%202024%20result,individuals%20aged%2065%20and%20over (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- World Bank. Food Prices for Nutrition DataHub. 2024. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/food-prices-for-nutrition (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- TURKSTAT. Statistics on Family, 2024. Available online: https://data.tuik.gov.tr/Bulten/Index?p=Statistics-on-Family-2024-53898&dil=2#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20ABPRS%20results,17%20age%20group%20was%2042.8%25 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Pekcan, A.G. Dietary Intake Pattern in Turkey. In Voluntary Guidelines for Mediterranean Diet; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2018; p. 49. [Google Scholar]

- Yılmaz, H.; Öztürk, Ş.N.; Dağ, M.M. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Consumers Buying Unpacked Dairy. MKU. Tar. Bil. Derg. 2022, 27, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engindeniz, S.; Taşkin, T.; Gbadamonsi, A.A.; Ahmed, A.S.; Cisse, A.S.; Seioudy, A.; Kandemir, Ç.; Koşum, N. Preferences for Milk and Milk Products. JOTAF 2021, 18, 470–481. [Google Scholar]

- Zazpe, I.; Sanchez-Tainta, A.; Estruch, R.; Lamuela-Raventos, R.M.; Schröder, H.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Salas-Salvado, J.; Corella, D.; Fiol, M.; Gomez-Gracia, E.; et al. A large randomized individual and group intervention conducted by registered dietitians increased adherence to Mediterranean-type diets: The PREDIMED study. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1134–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisciani, S.; Marconi, S.; Le Donne, C.; Camilli, E.; Aguzzi, A.; Gabrielli, P.; Gambelli, L.; Kunert, K.; Marais, D.; Vorster, B.J.; et al. Legumes and common beans in sustainable diets: Nutritional quality, environmental benefits, spread and use in food preparations. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1385232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullins, A.P.; Arjmandi, B.H. Health Benefits of Plant-Based Nutrition. Nutrients 2021, 13, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sezgin, A.C.; Onur, M. Traditional Turkish cuisine prepared with legumes. J. Gastron. Hosp. Travel 2022, 5, 170–181. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, K.; Goddyn, H.; Olsen, S.B.; Bredie, W.L. Identifying behavioral and attitudinal barriers and drivers to promote consumption of pulses: A quantitative survey across five European countries. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104455. [Google Scholar]

- Amoah, I.; Ascione, A.; Muthanna, F.M.; Feraco, A.; Camajani, E.; Gorini, S.; Armani, A.; Caprio, M.; Lombardo, M. Sustainable strategies for increasing legume consumption: Culinary and educational approaches. Foods 2023, 12, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayın, K.; Arslan, D. Antioxidant Properties of Red Pepper Paste. Int. J. Nutr. Food Eng. 2015, 9, 834–837. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S.; Connole, E.S.; Hill, A.M.; Buckley, J.D.; Coates, A.M. Eggs and Cardiovascular Disease. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2023, 25, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Micek, A.; Brzostek, T.; Toledo, E.; Iacoviello, L.; Astrup, A.; Franco, O.H.; Galvano, F.; Martinez-Gonzalez, M.A.; Grosso, G. Egg consumption and cardiovascular risk: A dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2021, 60, 1833–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO eLENA. Reducing Free Sugars in Children. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/elena/interventions/free-sugars-children-ncds (accessed on 10 April 2024).

- Şimşek, A.; Artık, N.; Baspınar, E. Detection of Raisin Concentrate (Pekmez) Adulteration by Regression Analysis Method. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004, 17, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, T.Y.; Imamura, F.; Monsivais, P.; Brage, S.; Griffin, S.J.; Wareham, N.J.; Forouhi, N.G. Dietary cost associated with adherence to the Mediterranean diet, and its variation by socio-economic factors in the UK Fenland Study. Br. J. Nutr. 2018, 119, 685–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor, R.; Pinilla, N.; Tur, J.A. Economic Cost of Diet and Mediterranean Adherence in Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, R.M.; Lopes, C.M.M.; Rodrigues, S.S.P.; Perelman, J. Excess Cost of Mediterranean Diet in a Mediterranean Country. Br. J. Nutr. 2022, 128, 1393–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubini, A.; Vilaplana-Prieto, C.; Flor-Alemany, M.; Yeguas-Rosa, L.; Hernández-González, M.; Félix-García, F.J.; Félix-Redondo, F.J.; Fernández-Bergés, D. Assessment of the cost of the Mediterranean diet in a low-income region: Adherence and relationship with available incomes. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). Agricultural Policy Monitoring and Evaluation 2025: Making the Most of the Trade and Environment Nexus in Agriculture; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Türkiye; TÜBİTAK.; Ministry of Trade; Central Bank. Market Fiyatı Platformu. Available online: https://marketfiyati.org.tr/ (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Dong, X.; Astill, G. Uniform Prices of Fresh Produce in US Retail Chains. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. Assoc. 2024, 3, 410–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citaristi, I. International Fund for Agricultural Development—IFAD. In The Europa Directory of International Organizations 2022; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 340–343. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO); International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD); United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); World Food Programme (WFP); World Health Organization (WHO). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2023: Urbanization, Agrifood Systems Transformation and Healthy Diets Across the Rural–Urban Continuum; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Casal, L.; Karakaya Ayalp, E.; Öztürk, S.P.; Navas-Gracia, L.M.; Geçer Sargın, F.; Pinedo-Gil, J. The quality turn of food deserts into food oases in European cities: Market opportunities for local producers. Agriculture 2025, 15, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoms-Young, A.; Brown, A.G.M.; Agurs-Collins, T.; Glanz, K. Food insecurity, neighborhood food environment, and health disparities: State of the science, research gaps and opportunities. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 119, 850–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; International Fund for Agricultural Development; United Nations Children’s Fund; World Food Programme; World Health Organization. The Cost and Affordability of a Healthy Diet FAO. 2023. Available online: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/f1ee0c49-04e7-43df-9b83-6820f4f37ca9/content/state-food-security-and-nutrition-2023/cost-affordability-healthy-diet.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

| Food Group | Girl | Boy | Adult Woman | Adult Man |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vegetables (servings/day) | 2 | 6 | 4 | 6 |

| Fruits (servings/day) | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| EVOO 1 (servings/day) | 2 | 7 | 4 | 5 |

| Cereals (servings/day) | 2 | 7 | 4 | 6 |

| Nuts and Olives (servings/day) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Dairy products (servings/day) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Legumes (servings/week) | 3 | 7 | 3.5 | 6 |

| Fish and Seafood (servings/week) | 3 | 5 | 2.5 | 5 |

| White meat/Poultry (servings/week) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Eggs (servings/week) | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Red meat (servings/week) | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Potatoes (servings/week) | 0.5 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Desserts and sweets 2 (servings/week for females; servings/day for males) | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Spices (g/day) | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Scenario | Income Source | Monthly Household Income (TRY/Euro) | MD Basket Cost (TRY/Euro)-Month) | Affordability (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | TR62 equivalent adult (S = 2.3) | 21,331/430.78 | 20,930.2/422.68 | 98 |

| Sensitivity | Türkiye, national median for a nuclear family | 27,918/563.80 | 20,930.2/422.68 | 75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yıldırım, G.; Sarıyer, E.T.; Yılmaz Akyüz, E. Is the Mediterranean Diet Affordable in Türkiye? A Household-Level Cost Analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411254

Yıldırım G, Sarıyer ET, Yılmaz Akyüz E. Is the Mediterranean Diet Affordable in Türkiye? A Household-Level Cost Analysis. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411254

Chicago/Turabian StyleYıldırım, Gonca, Esra Tansu Sarıyer, and Elvan Yılmaz Akyüz. 2025. "Is the Mediterranean Diet Affordable in Türkiye? A Household-Level Cost Analysis" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411254

APA StyleYıldırım, G., Sarıyer, E. T., & Yılmaz Akyüz, E. (2025). Is the Mediterranean Diet Affordable in Türkiye? A Household-Level Cost Analysis. Sustainability, 17(24), 11254. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411254