1. Introduction

A remote operator (RO) is responsible for the safety of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASSs) in the context of sustainable maritime transportation without a crew on board by monitoring the ship from a remote location and intervening when necessary [

1]. Currently, on a conventional ship with a crew on board, the ship’s navigator directly handles the vessel, visually observes the surrounding environment [

2], and quickly performs navigational actions, including steering. Conversely, an RO relies on limited information and sensors in remote locations [

2,

3,

4], and there is a risk that ROs may underestimate or inadequately response to the environment effects that they cannot sense [

5].

MASSs encounter environmental challenges, including wind, waves, and tidal currents, which must be considered for safe autonomous navigation and can significantly affect maneuvering performance [

6,

7]. External forces significantly impact the ship’s turning ability [

8]. In particular, tidal currents have the potential to cause the ship to move by laterally swaying the stern or bow, affecting the ship’s speed, position, or course [

9,

10,

11]. An RO is required to respond to this motion by steering the ship in the desired direction [

12], taking into account that tidal currents can alter the ship’s ability to turn [

13].

The Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) is currently working on regulations for MASSs to ensure their safe operation. The roadmap outlines that the development of the mandatory MASS Code will begin in 2028, based on the non-mandatory code, with SOLAS amendments for its adoption. The MASS Code is anticipated to be adopted in July 2030, taking effect on 1 January 2032 [

14]. According to recent IMO trends, even if a MASS is fully unmanned, humans will remain responsible for ship safety [

15]. Responsibility for the safety of the MASS is assumed by an RO who monitors the MASS from a remote operation center and intervenes in emergency situations. As a result, discussions are ongoing regarding the basic competencies required for an RO to ensure safe MASS operations under limited conditions [

16]. One basic competence of an RO is the ability to accurately understand and respond to the effects of tidal currents on ship maneuvering [

17].

It should be emphasized that the objective of this study is not to construct or validate a full maneuvering model for a MASS itself. The present study should be interpreted as a simulator-based proxy investigation that establishes a foundational competence evaluation framework under controlled tidal current conditions, rather than as a direct validation of operational MASS environments. Therefore, the proposed approach is intentionally limited to a simulator-based proxy setting (without validation in operational MASS environments), but it is adopted to provide a controlled and repeatable methodological foundation for quantitatively evaluating remote operator steering competence under tidal current effects. Specifically, this study focuses on proposing and examining a feature-based competence evaluation framework for human remote operators who supervise MASSs. The framework is implemented in a simulator-based environment that reproduces MASS-scale ship handling characteristics under tidal current effects, so that RO steering behavior can be analyzed under controlled and repeatable conditions.

Previous studies have primarily focused on analyzing the effects of environmental factors, such as tidal currents, on the physical movement of ships. Li and Zhang [

18] explained the differences in a ship’s maneuvering caused by the combined effects of wind, waves, and currents. Jing et al. [

19] analyzed ship maneuverability under severe weather conditions and highlighted the importance of the rudder damping function in ship steering. Wang et al. [

20] examined the impact of various environmental factors on a ship’s maneuvering through simulations. Kornacki et al. [

21] analyzed the effects of currents on a ship’s rotation and acceleration and assessed the differences in turning maneuvers under varying current conditions.

However, prior studies mainly focus on the changes in the physical movement of the ship due to tidal currents and have limitations in analyzing how operators responds to environmental factors and the impact on their ship steering competence. For example, Hjelmervik et al. [

22] compared the effects of homogeneous and heterogeneous currents on RO training but lacked a detailed analysis of the operator’s steering strategies and response methods. Lee and Jeong [

23] analyzed the impact of strong cross currents on ship speed and maneuverability, but this research did not provide in-depth insights into the operator’s actual response methods or steering strategies. As a result, there is a lack of research on the practical response strategies and steering methods of operators during ship handling, leading to an inadequate understanding of effective response methods in real-world steering situations.

Although these studies have enhanced our understanding of ship hydrodynamics under current influence, they provide limited insight into how human operators perceive, decide, and respond to tidal current effects during steering. Therefore, this study shifts the focus from ship motion modeling to the quantitative evaluation of operator steering competence. To address the limitation, this study focuses on quantitatively analyzing the effect of tidal currents on the operator’s ship steering competence. The simulation-based navigation experiment was designed to achieve a more detailed understanding of how tidal currents affect ship steering, and priority features affecting an RO’s steering competence were identified through the experiments. The experiment systematically analyzed the changes in ship steering competence in the presence and absence of tidal currents, and the identified features were prioritized through priority analysis.

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to identify the steering features through which tidal currents affect maneuverability and to determine which tidal current response features should be prioritized when training ship remote operators in a simulator-based environment as a foundational step toward future MASS remote operation training. In this study, the tidal current environment was modeled directly within the Kongsberg K-Sim simulator using its environmental setting module, which allows users to reproduce realistic hydrodynamic conditions for controlled experimentation and competence evaluation. The findings are expected to contribute to the development of a training and evaluation model of ROs’ ability to respond effectively to tidal currents in real-world operational situations, supporting sustainable MASS remote operation and training practices.

2. Methods

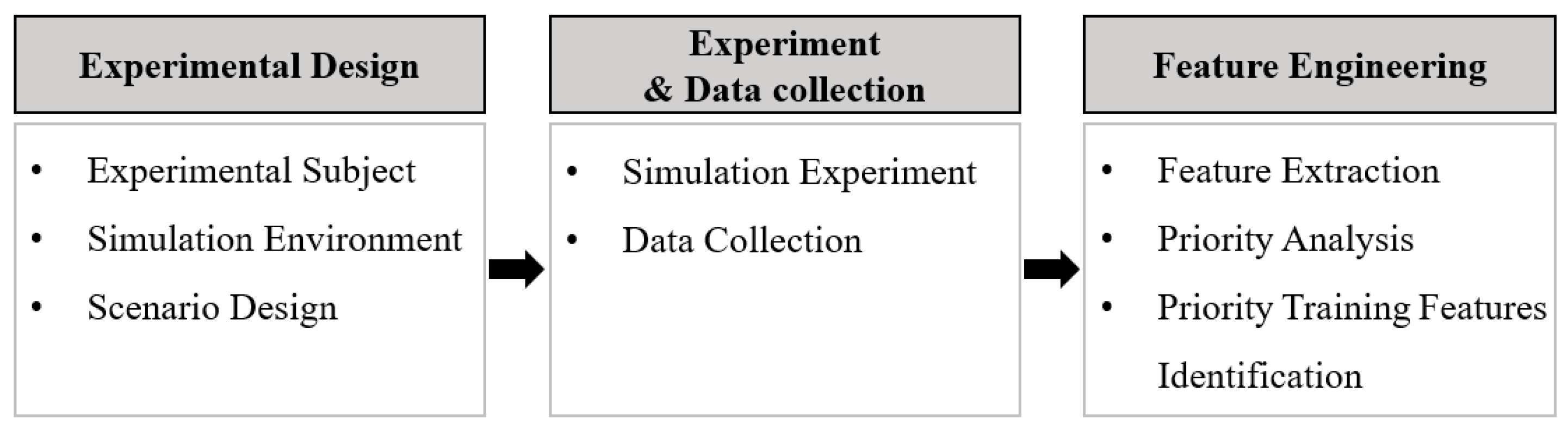

Figure 1 depicts the workflow of the proposed method. The proposed method is introduced in three sections, with eight sub-processes added and each process explained.

2.1. Experimental Design

A total of 20 third-year students from Mokpo National Maritime University who are currently training as cadets on the university’s training ship participated in the experiment. The cadets had completed identical navigation and simulator courses at Mokpo National Maritime University, forming a homogeneous group. This controlled participant selection ensured that performance differences observed in the experiment were mainly attributable to tidal current conditions rather than variations in individual experience. Recruitment was conducted through an open call for volunteers and the experiment was carried out in strict adherence to ethical standards. The experiment was conducted using the ship handling simulator (SHS) installed on the training ship Segero at Mokpo National Maritime University, as shown in

Figure 2.

Table 1 provides details of the simulator model and manufacturer.

The Kongsberg K-Sim Navigation system used in this study is a full-mission ship handling simulator that is routinely employed in the regular ship handling education and training program at Mokpo National Maritime University. Although the detailed hydrodynamic coefficients of the simulated vessel are proprietary, the simulator has been calibrated and verified for realistic maneuvering responses in large merchant vessels and is considered sufficiently accurate for comparative analyses of steering performance under different environmental conditions.

The simulation-based navigation experiment followed a sequence of orientation, demonstration of navigation equipment, and participant simulation experiments. The orientation provided an overview of the experiment, including details about the simulation ship maneuvering and steering performance, as well as important safety considerations. The simulated navigation was conducted in two scenarios per participant, each taking about 10–15 min.

The model ship was set to be most similar to the Korean Autonomous Surface Ship Project’s demonstration ship, an 1800 TEU container ship [

24], with dimensions of 165 m in length, 27.1 m in width, and a draft of 8.44 m.

Figure 3 illustrates the model ship used for the simulation.

This simulator configuration was selected to realistically represent MASS-scale ship handling behavior under tidal current effects. Accordingly, the simulator experiment serves as a proxy environment for evaluating remote operator competence in MASS operation. In this sense, the present experiments should be interpreted as a simulator-based proxy study for RO competence in MASS-like conditions, rather than as an attempt to validate a specific full-scale MASS maneuvering model.

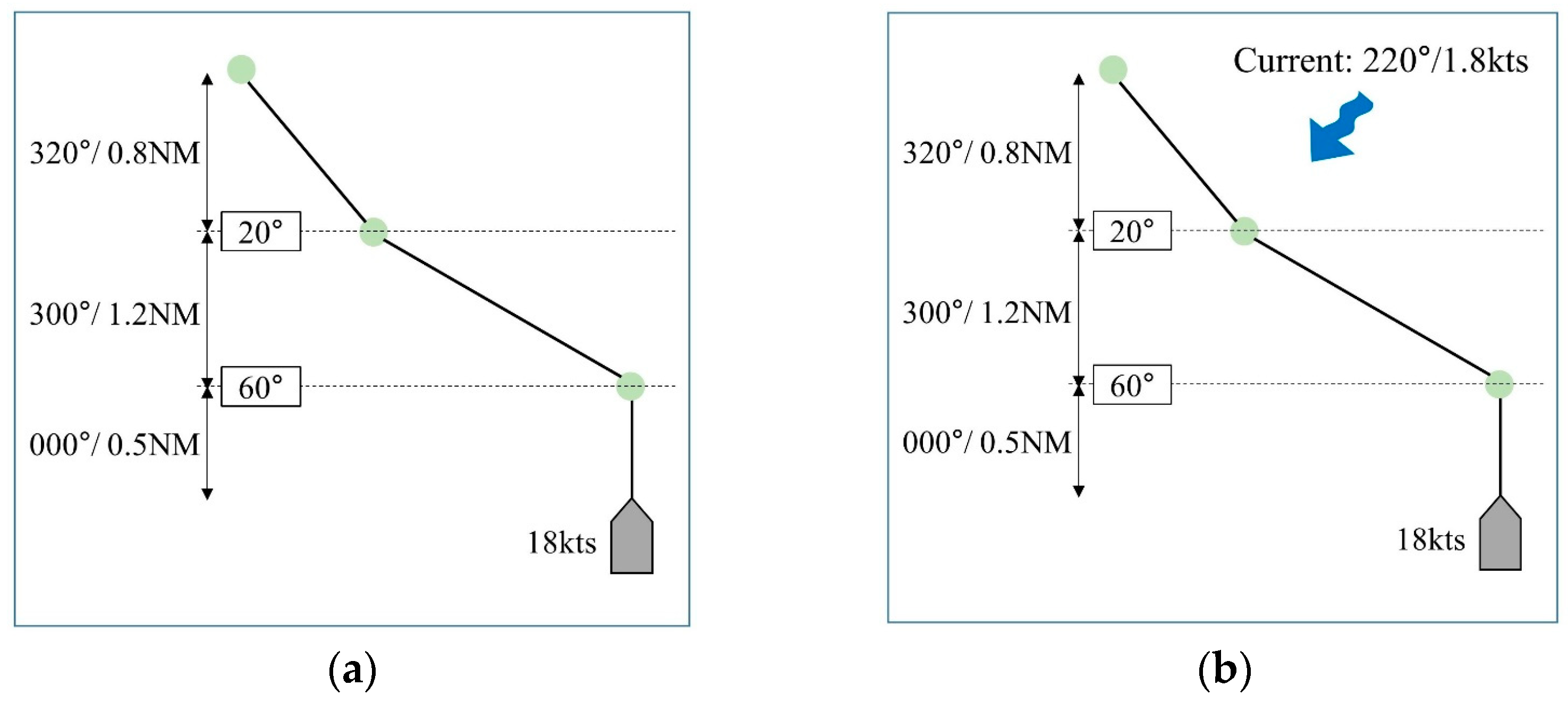

In the experiment, the ship’s speed was 18 knots in an obstacle-free marine environment, and control of the ship was allowed only by the steering wheel. The planned route was charted using the electronic chart display and information system, and participants were required to navigate by hand steering following this planned route, as shown in

Figure 4.

The simulation scenarios were designed with a total distance of 2.5 nautical miles, including three straight segments and two altering points, as shown in

Figure 5. The distance to the first altering point was 0.5 nautical miles, to the second altering point it was 1.2 nautical miles, and from second point to the end of the planned route it was 0.8 nautical miles. The altering angles were set based on the difficulty level of the simulation scenarios [

25], with high-difficulty alterations (60 degrees) and low-difficulty alterations (20 degrees).

Two simulated navigations were carried out for each participant on the same planned route, with and without current in the environmental settings. The condition without tidal currents involved the absence of all external forces, while the condition with tidal currents allowed the model ship to be affected by currents set to a direction of 220° at 1.8 knots, corresponding to an effective 40° angle relative to the ship’s heading, which causes the largest turning moment [

11], and was set to a force sufficient to affect the ship.

In this initial study, this single tidal current condition (220° at 1.8 knots) was intentionally used so that all participants maintained strict experimental control and to ensure a clearly observable yaw moment for analyzing the relative effect of tidal currents on steering performance.

2.2. Experiment and Data Collection

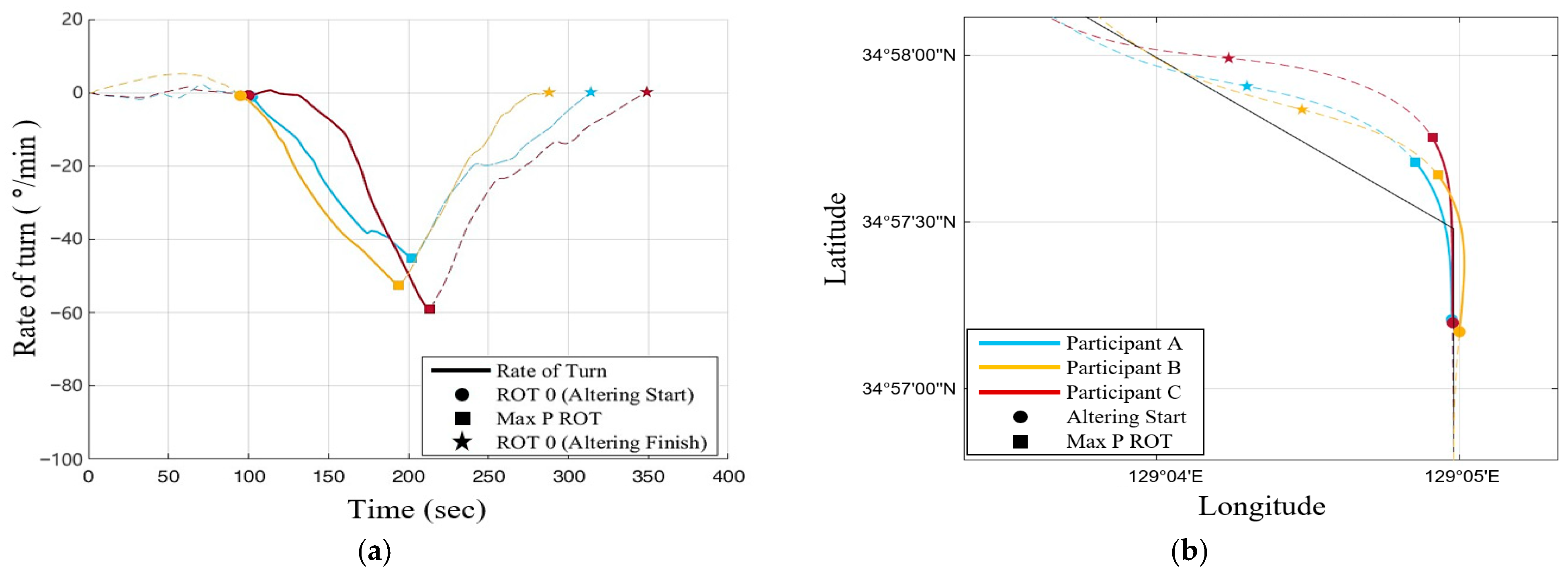

Each participant conducted two simulated navigations, with each experiment taking 10–15 min. The scenarios were divided into two conditions, without and with tidal currents, and the ship’s steering performance was evaluated in every situation. The data collected during the experiment included time, longitude, latitude, rudder usage, heading, ship speed, and Rate Of Turn (ROT), and were recorded every second in the SHS.

The data were collected from the simulator to extract steering characteristics for responding to tidal currents. The tidal currents response and steering features summarized in

Table 2 were selected based on navigation experience and the experimental procedures. The steering features were analyzed to identify critical aspects of ship steering in response to tidal currents.

Each feature was extracted from the time series of rudder angle, heading, and ROT as follows. ART (Altering to ROT zero time) is defined as the time interval between the moment when the rudder order for the scheduled course alteration is first applied and the moment when ROT returns to zero after the turn is completed. MRT (Maximum port ROT) is defined as the maximum port-side ROT observed during the turning maneuver following the alteration. OSA (Overshoot angle) is defined as the absolute difference between the final stabilized heading after the turn and the planned target heading. RAM (Rudder angle at maximum port ROT) is defined as the rudder angle at the time when the port ROT reaches its maximum value. These definitions ensure that each feature corresponds to a specific aspect of turning acceleration or deceleration under tidal current effects.

2.3. Priority Analysis of Tidal Currents Response and Steering Features

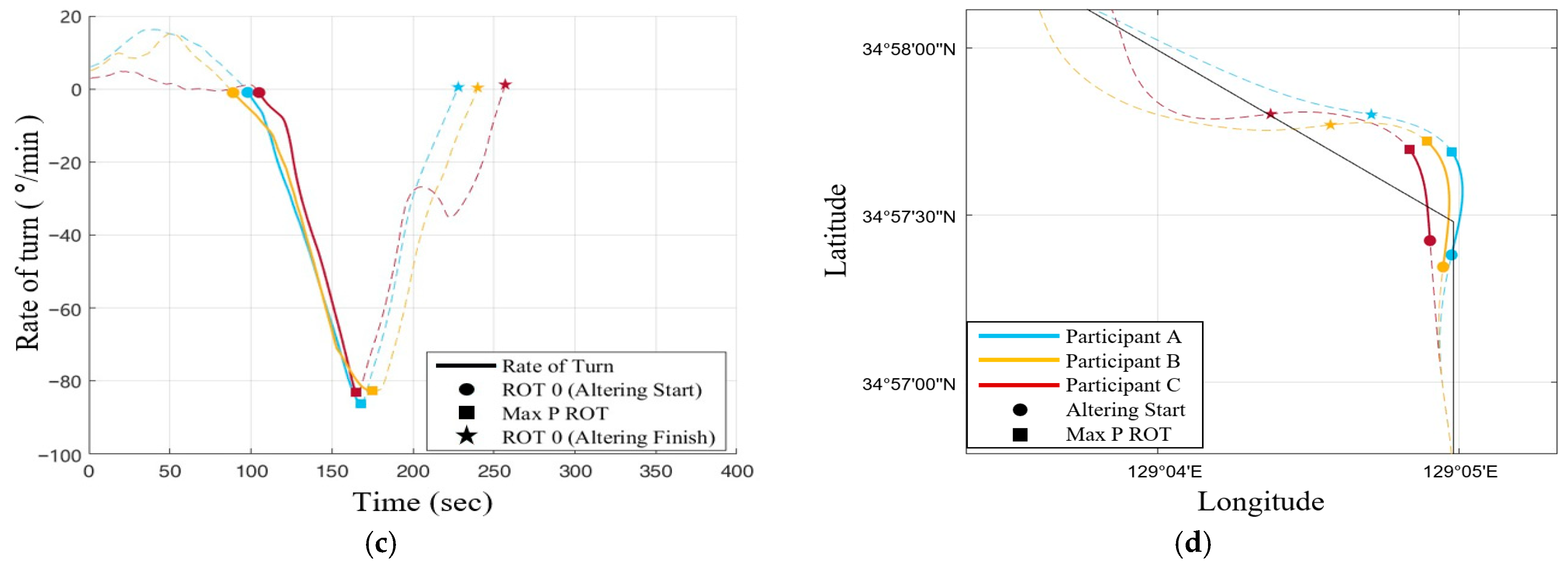

The features were evaluated using three algorithms to identify the priority steering competence feature that an RO is required to possess for responding to tidal currents.

Random Forest is a machine learning algorithm used to evaluate the importance of variables in regression and classification. Random Forest is based on an ensemble of decision trees and enhances prediction performance through the aggregation of decision trees. In Random Forest, the importance of variables is evaluated using two main indicators: Mean Decrease in Impurity and Mean Decrease in Accuracy [

26]. Logistic Regression is used in binary classification due to its minimal assumptions about data distribution and its high classification accuracy.

Logistic Regression indicates the importance of each feature in classification decisions based on the weights of the features. Larger absolute values of weights suggest higher importance of the respective features. Logistic Regression is easy to interpret, computationally efficient, and particularly advantageous for linearly separable data [

27].

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) are used to classify data by learning an optimal hyperplane based on the features of the observed data and to separate different classes. SVMs are applied in various data science scenarios due to their high accuracy and reproducibility, demonstrating excellent performance in classification tasks and preventing overfitting [

28].

All machine learning models were implemented in MATLAB R2024a using the Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox. Before applying the algorithms, all steering feature variables (ART, MRT, OSA, RAM) were standardized using Z-score normalization (mean = 0, standard deviation = 1), and outlier values were filtered prior to normalization. The resulting feature matrix X contains the four standardized steering features for each of the 40 trials (20 participants × 2 current conditions), and the binary target label y indicates whether a given trial was performed without tidal currents (y = 0) or with tidal currents (y = 1).

To avoid overfitting and to obtain stable estimates of feature importance, we employed k-fold cross-validation with stratification by current condition. In each fold, the dataset was randomly partitioned into k − 1 training folds and one validation fold, and the feature importance values were averaged over all folds. For each algorithm, the principal hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees and maximum depth for Random Forest, regularization type and strength for Logistic Regression, and kernel type and kernel parameters for SVM) were selected using a small-scale grid search within the ranges recommended in the literature and provided by MATLAB’s default settings.

4. Discussion

4.1. Experiment and Data Analysis

An RO is required to recognize and respond to the effects of tidal currents on ship control in environments with constrained situational awareness when remotely controlling large ships, including prospective MASSs or other remotely operated vessels. In order to respond effectively to tidal current effects, ROs need to develop the competence to steer and maneuver the ship effectively.

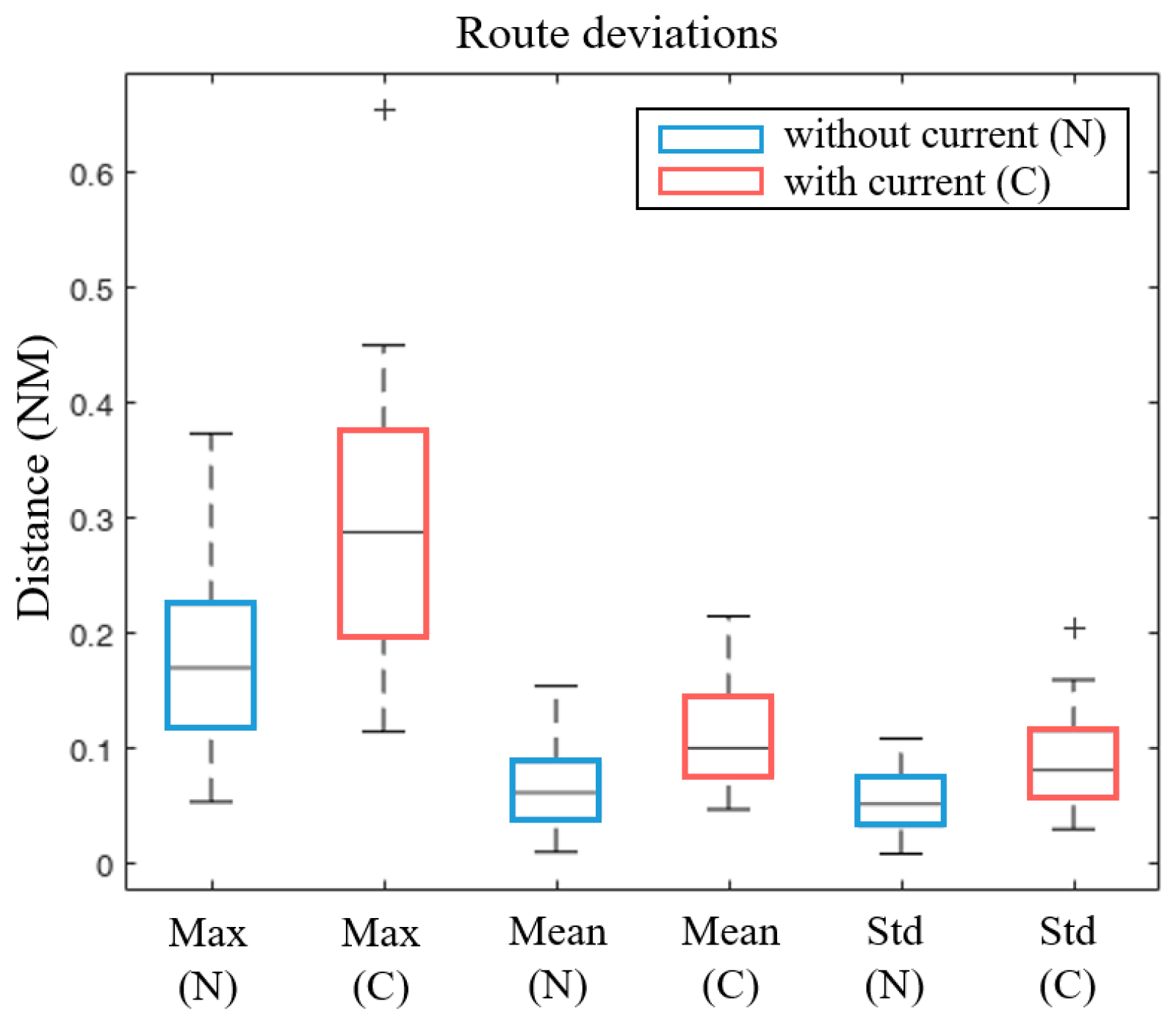

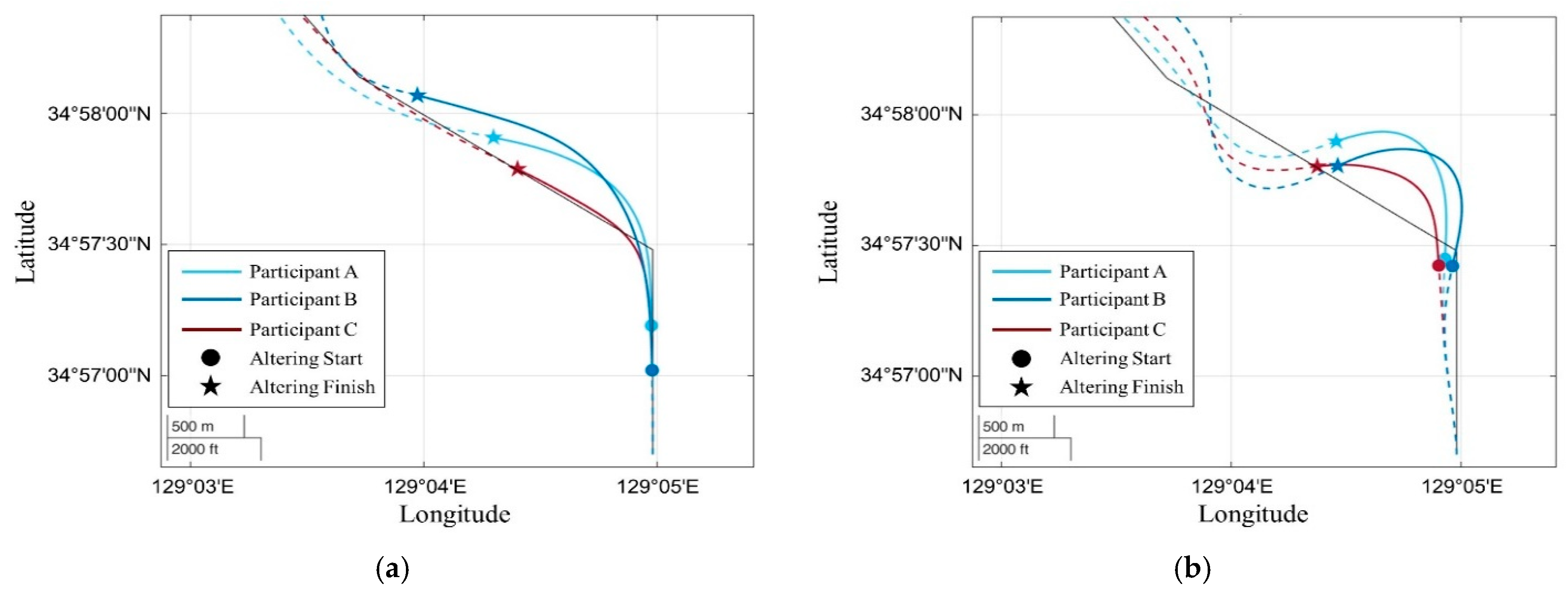

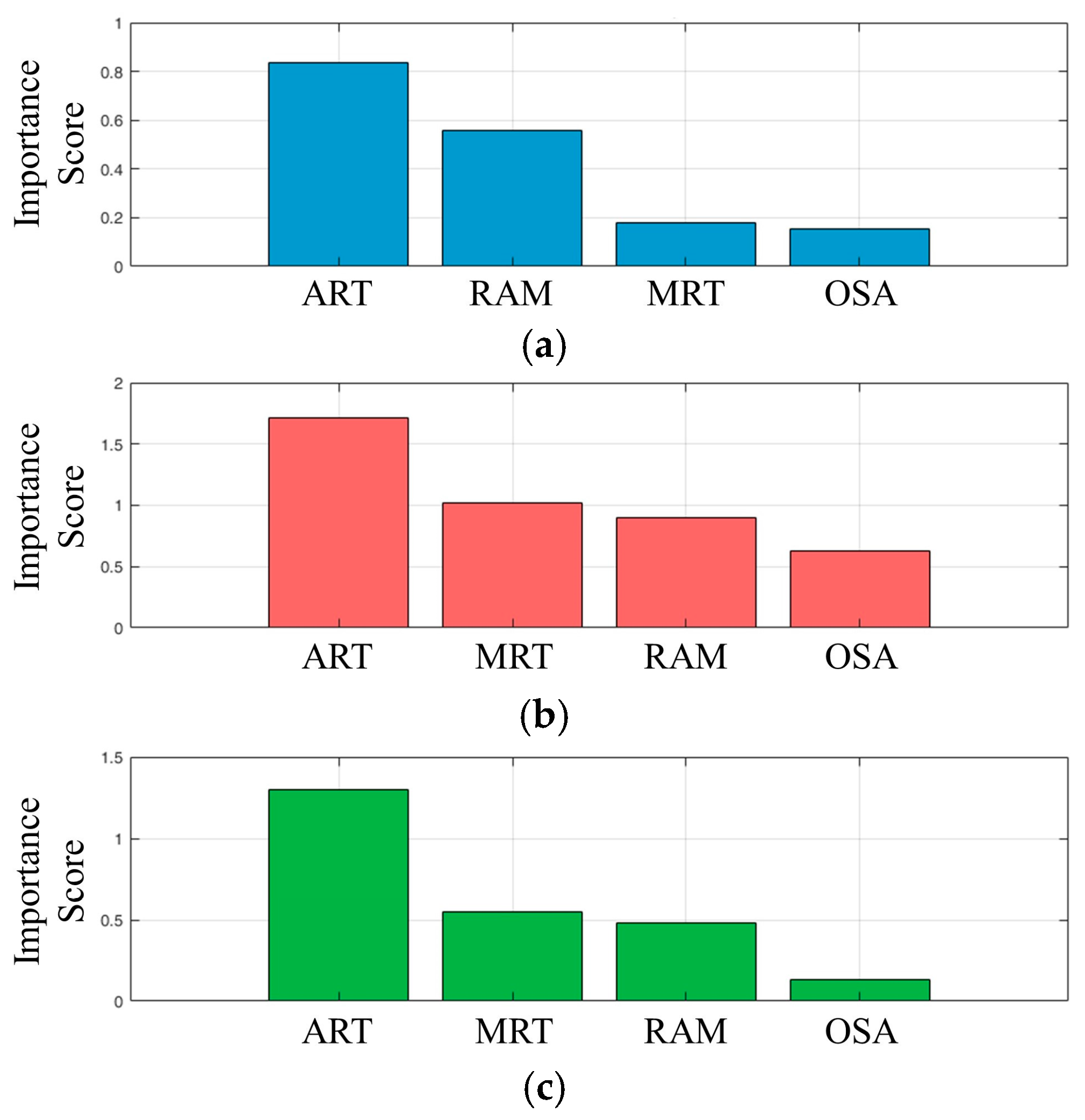

Figure 6 depicts the ship track results of participants under different conditions with and without currents. When tidal currents were absent, the trajectories were closely centered around the planned route, with minimal deviation. In contrast, when currents were present, the track width increased significantly, showing S-shaped trajectories. Participants found maneuvering the ship more challenging when experiencing the unexpected effects of currents. Notably, participants who demonstrated difficulty in responding effectively to the tidal current, particularly during the initial alteration segment, showed significant divergences from the intended route, resulting in pronounced S-shaped trajectories. The experimental results underscore the necessity of accurately perceiving the ship’s steering performance and the direction and intensity of the tidal current to effectively respond to tidal currents. Despite the inherent limitations of a simulator-based proxy setting (e.g., the absence of operational MASS constraints and broader current scenarios), a key strength of the proposed approach lies in its ability to isolate and consistently compare operator steering responses to tidal current effects under identical and repeatable conditions.

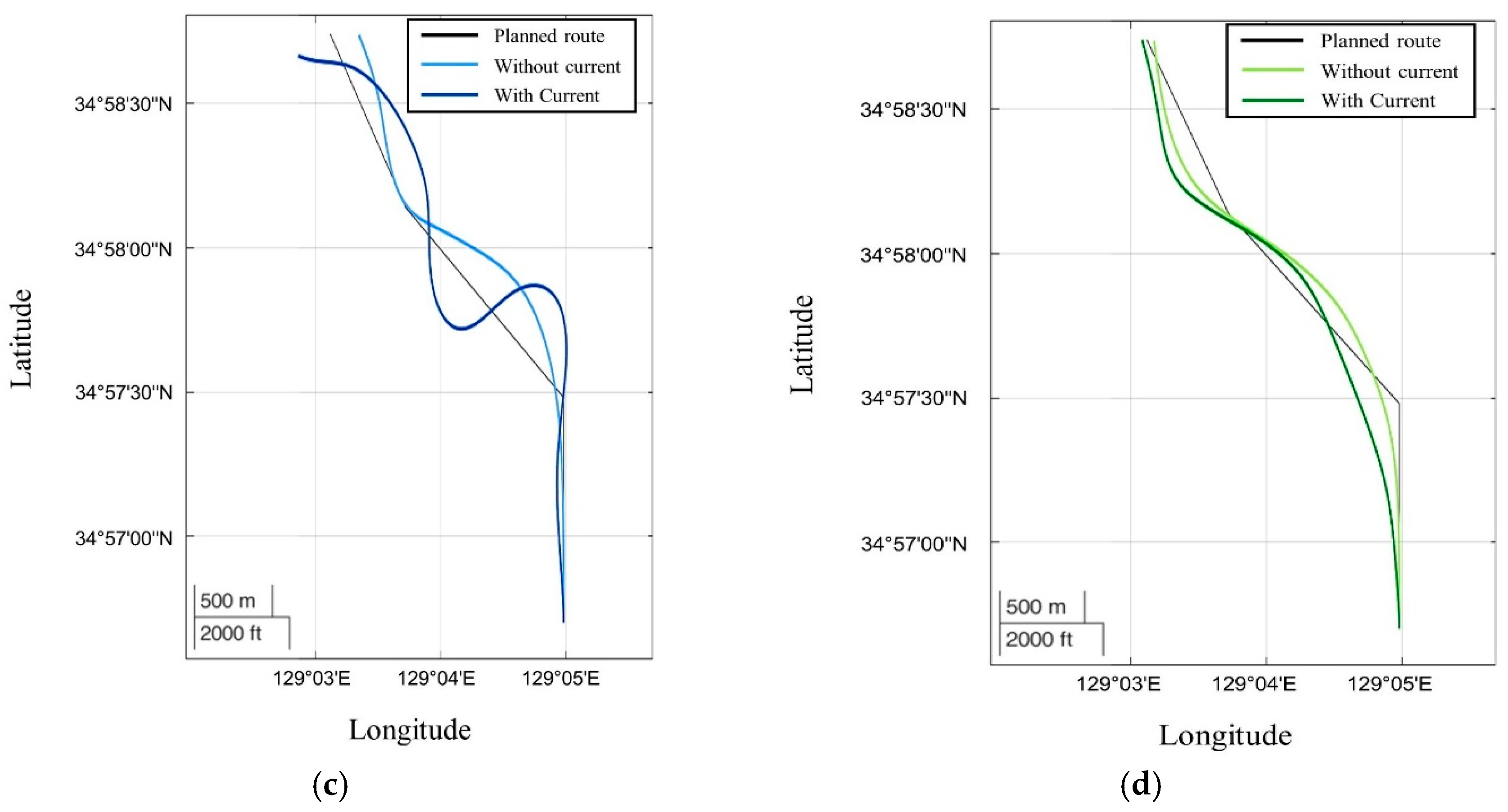

The overall response evaluation results and trajectories for two cadets are presented in

Figure 14.

Figure 14a presents a spider plot of cadet A with four features positioned near the center, indicating an inadequate response to the presence of tidal currents. The evaluation results show a lack of steering competence in responding to tidal currents, as shown in

Figure 14c. In contrast,

Figure 14b presents a spider plot of cadet B that is drawn further away from the center for both the presence and absence of external forces, indicating good response competence. Additionally, the trajectory shows an effective response to the current, as shown in

Figure 14d.

The spider plots in

Figure 14a,b illustrate how each feature differentiates steering competence in the presence and absence of tidal currents. In the spider plots, ART and MRT in the acceleration domain, which face each other, evaluate responses to tidal currents during turning, while OSA and RAM in deceleration evaluate rudder adjustments for decelerating turns. Features positioned closer to the center indicate a lower ability to steer effectively in response to tidal currents.

The analysis of features related to responding to tidal currents provides insights into ship steering competence and the necessary response measures. The analysis of features in two domains yields a more precise evaluation of steering competence, which allows fir the development of appropriate strategies for training cadets to respond to tidal currents.

4.2. Discussion on Priority Analysis of Tidal Currents Response Steering Features

In order for ROs to effectively respond to the effects of tidal currents, it is important to identify which steering features should be prioritized in training. For this purpose, feature priority analysis was performed using Random Forest, Logistic Regression and SVMs. The priority analysis showed that the Random Forest model gave the highest priority to ART and RAM. The highest priority means that regression coefficients contribute the most to the model’s predictive performance. In Logistic Regression, the regression coefficients for ART and MRT were the largest, indicating that these features have a strong effect on the dependent variable. The SVM also showed that the features of ART and MRT had the largest coefficients, indicating that these features had a strong effect on the decision boundary. The highest ranked ART and the second ranked MRT value after turning were identified as the most prioritized features for competence evaluation.

Table 3 shows the priority training features for steering competencies in response to tidal currents, including ranking.

ART is the time it takes for the ship to commence a turn and for ROT to return to zero, completing the turn. This feature is used to evaluate the ship’s average control of its ROT during the turn, even in the presence of tidal currents that accelerate the ship’s turn. A relatively short ART, both with and without tidal currents, indicates that the ship has completed the turn while maintaining control of the heading to prevent the ROT from becoming excessive.

MRT is the maximum value of the ROT reached by the ship after the commencement of a turn. When turning performance is affected by tidal currents, especially environmental features such as tidal currents, MRT demonstrates how rapidly the ship’s heading is turning. ART and MRT represent crucial criteria for evaluating the extent to which an RO is effectively controlling the ship’s heading in the presence of tidal currents.

ART and MRT are the most significant features in explaining the differences in ship steering competencies under conditions with and without the effect of tidal currents. ART and MRT provide a comprehensive benchmark for assessing turning control competencies when responding to tidal currents and are expected to be priority features in training ROs to recognize the effect of tidal currents and enhance their steering competence.

Previous studies on operator competence have mainly emphasized qualitative assessment features such as decision-making ability, situational awareness, and cognitive workload using simulator-based observation or questionnaire data. Likewise, existing studies on tidal current effect modeling have primarily focused on numerical or hydrodynamic simulations rather than evaluating the operator’s behavioral response. In contrast, the present study introduces a quantitative feature-based framework that analyzes measurable steering features (ART, MRT, OSA, RAM) under controlled tidal current conditions. This approach complements conventional competence assessment and modeling methods by directly linking operator steering behavior with environmental force effects, providing a novel quantitative perspective that can inform the development of future frameworks for evaluating remote operator competence in MASS-like scenarios.

5. Conclusions

ROs of MASSs may encounter challenges in maneuvering due to tidal currents. Therefore, an RO is required to accurately understand and respond to the effects of tidal currents within constrained situational awareness environments. However, research has primarily focused on hull movement rather than maneuvering due to tidal currents. This study aimed to identify the priority features affecting ship steering under tidal current conditions and to determine which tidal current response features should be prioritized when training ship remote operators in a simulator-based environment, serving as a foundational step toward future MASS remote operation training.

To identify response steering features, simulation experiments were conducted to compare the ship’s steering performance under various scenarios with and without currents and to quantitatively analyze the effect of currents on ship control. As a result, the effect of tidal currents on the ship’s turning acceleration and turning deceleration performance was identified, and three algorithms were applied to identify the two most important features.

In conclusion, this research proposes ART and MRT as the priority features used to train ROs’ to respond to tidal currents. The findings offer a simulator-based foundational framework that may contribute to the development of RO training and competence evaluation models, with potential applicability to future MASS remote operation training after further validation in real-world environments.

Comparable simulator-based studies evaluating operator competence under tidal current conditions are currently scarce. This limitation highlights the novelty of the present work and suggests the need for future research involving various vessel types and current scenarios. In addition, the present work is based on a traditional full-mission ship handling simulator that approximates the maneuvering characteristics of a large container vessel relevant to MASS-scale applications. While this provides a technically realistic and controllable proxy environment for analyzing RO steering competence, full-scale validation using actual MASS platforms and shore control centers will be necessary in future research to generalize the findings.

Future studies will extend the present framework by incorporating modeling approaches and simulator-based training programs to evaluate and enhance remote operator competence under various tidal current scenarios. Additionally, the identified steering features, ART and MRT, can be utilized as measurable indicators within simulator-based RO training programs to assess and improve operators’ response competence under tidal current effects. Furthermore, future experiments will also integrate propulsion control and participants with diverse training backgrounds to verify the generalizability of the proposed framework.