A Web-Based Learning Model for Smart Campuses: A Case in Landscape Architecture Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Material

2.3. Methodology

2.3.1. Study Design

- The development and implementation of the digital system

- The functioning of the system and user evaluations

2.3.2. Data Analysis

3. Results

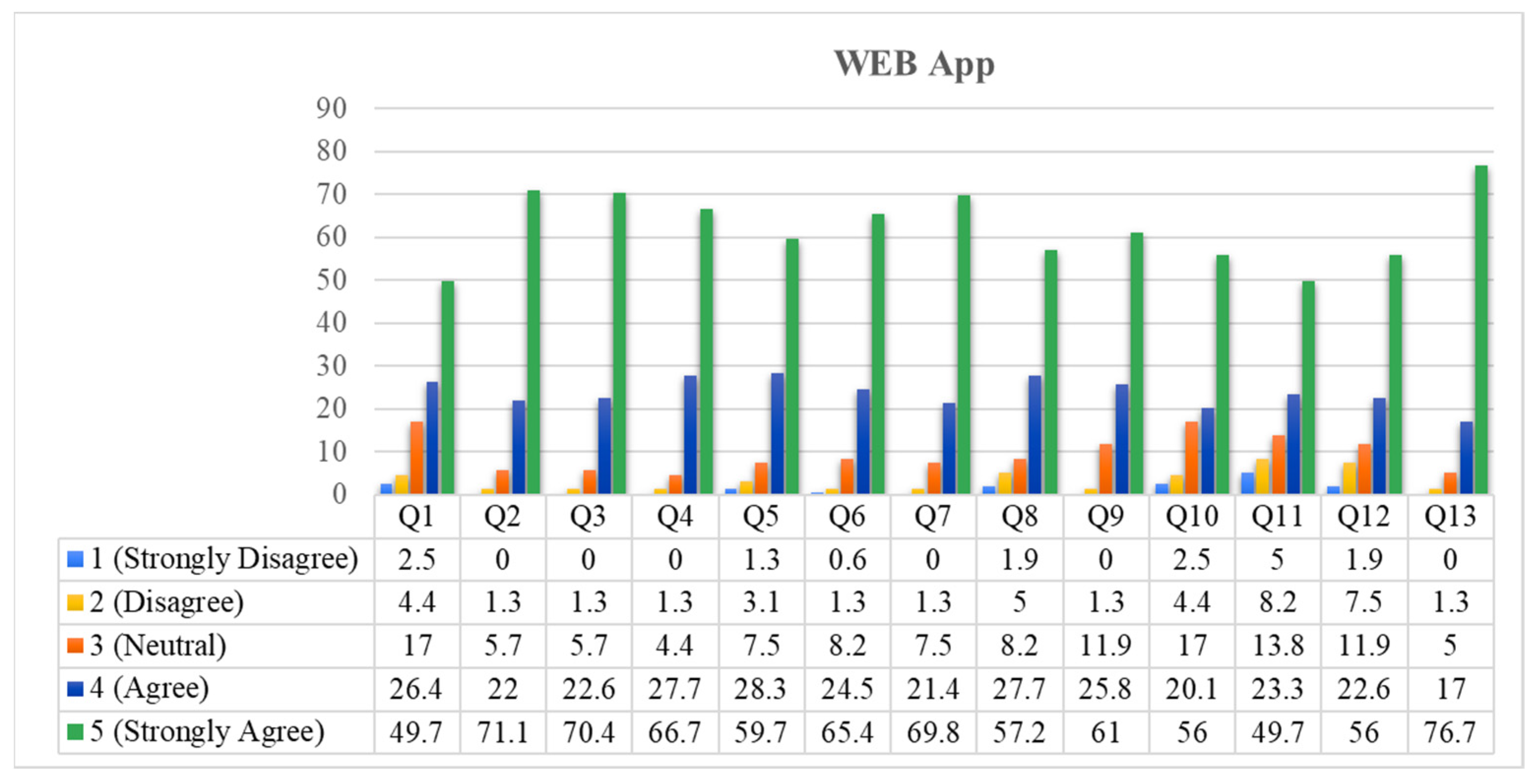

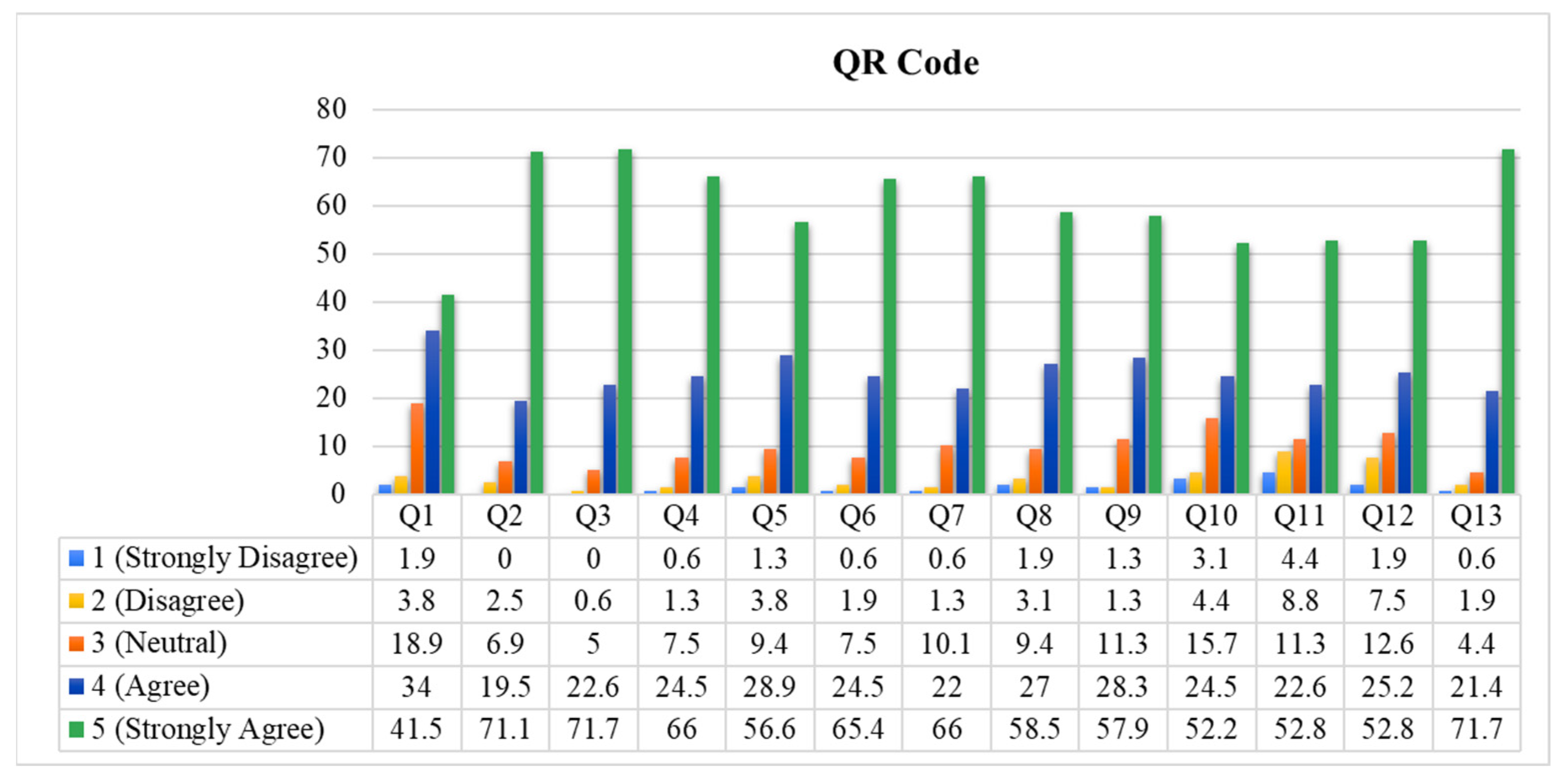

3.1. Analysis and Evaluation of Questions Related to the Web-Based and QR Code Applications

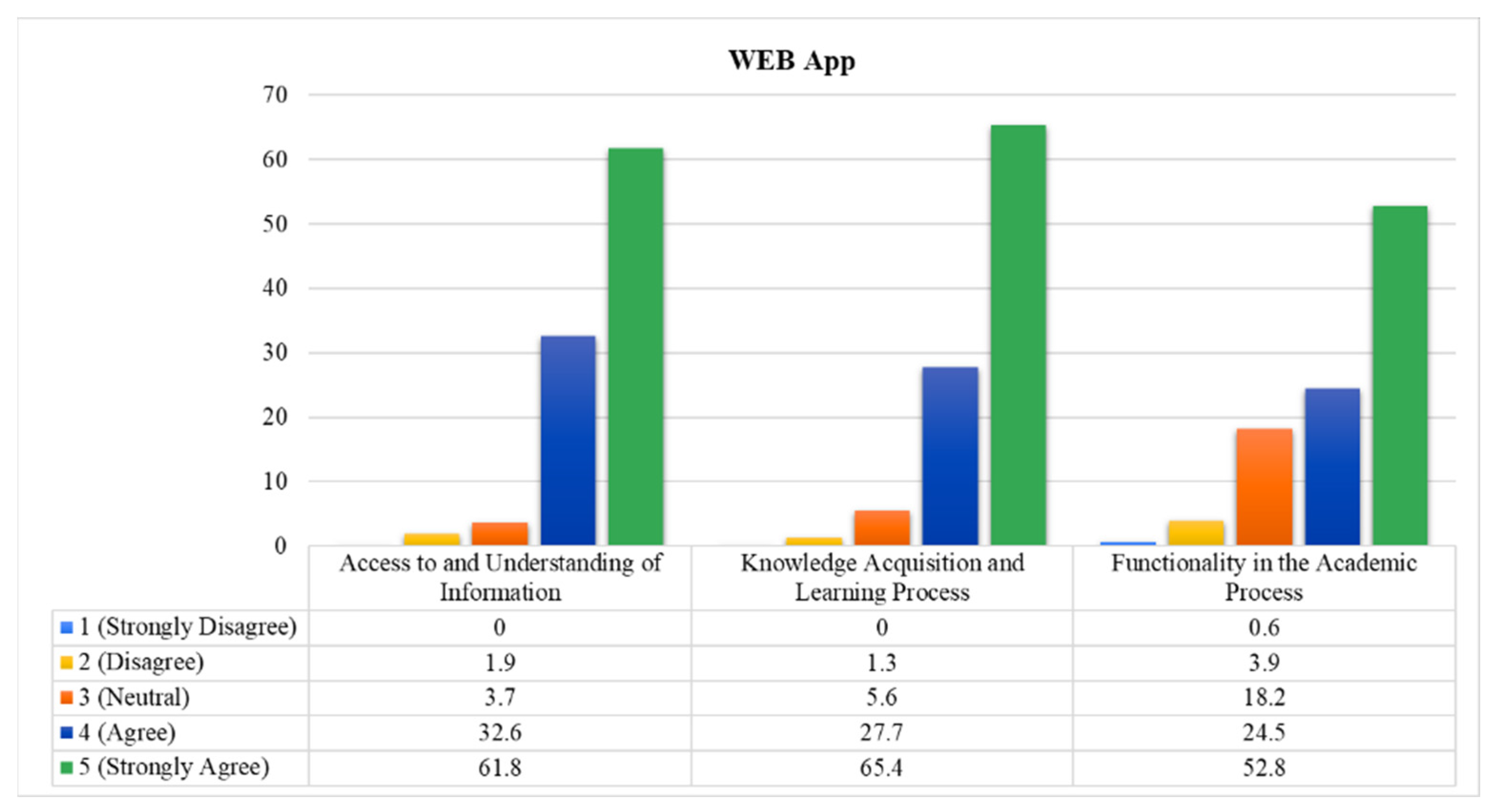

3.2. Analysis of Question Groups Related to Web-Based and QR Code Applications

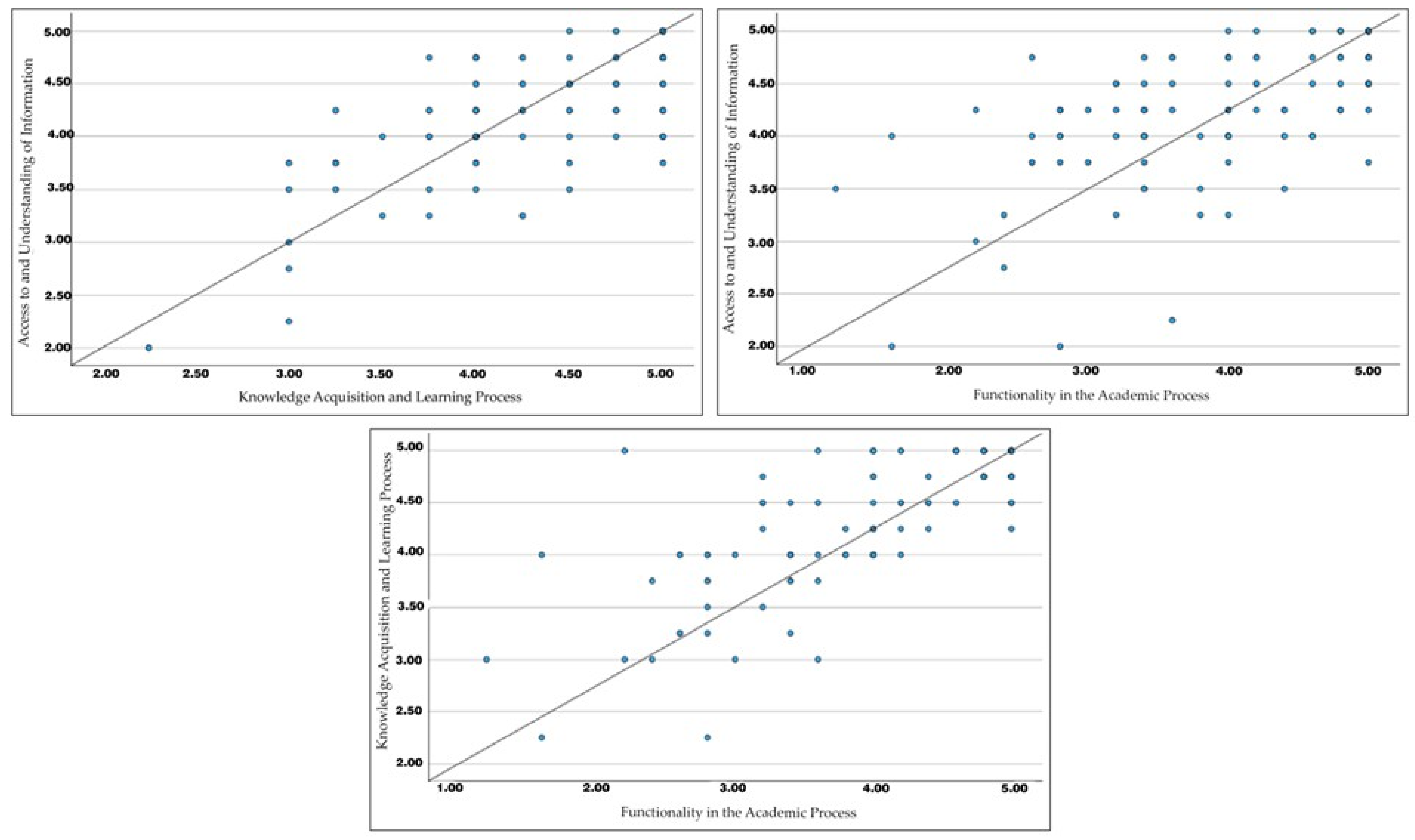

3.2.1. Web-Based Applications

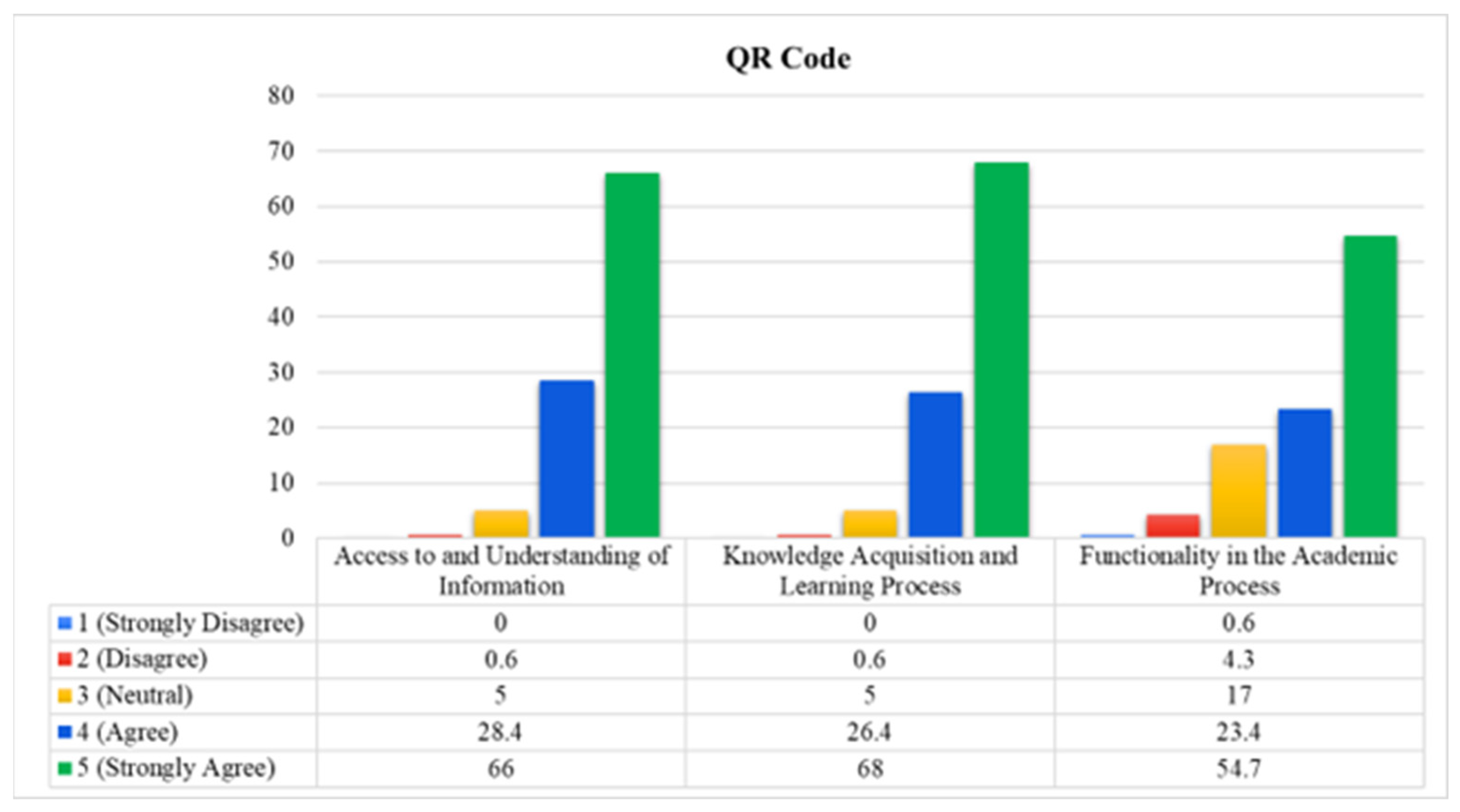

3.2.2. QR Code Application

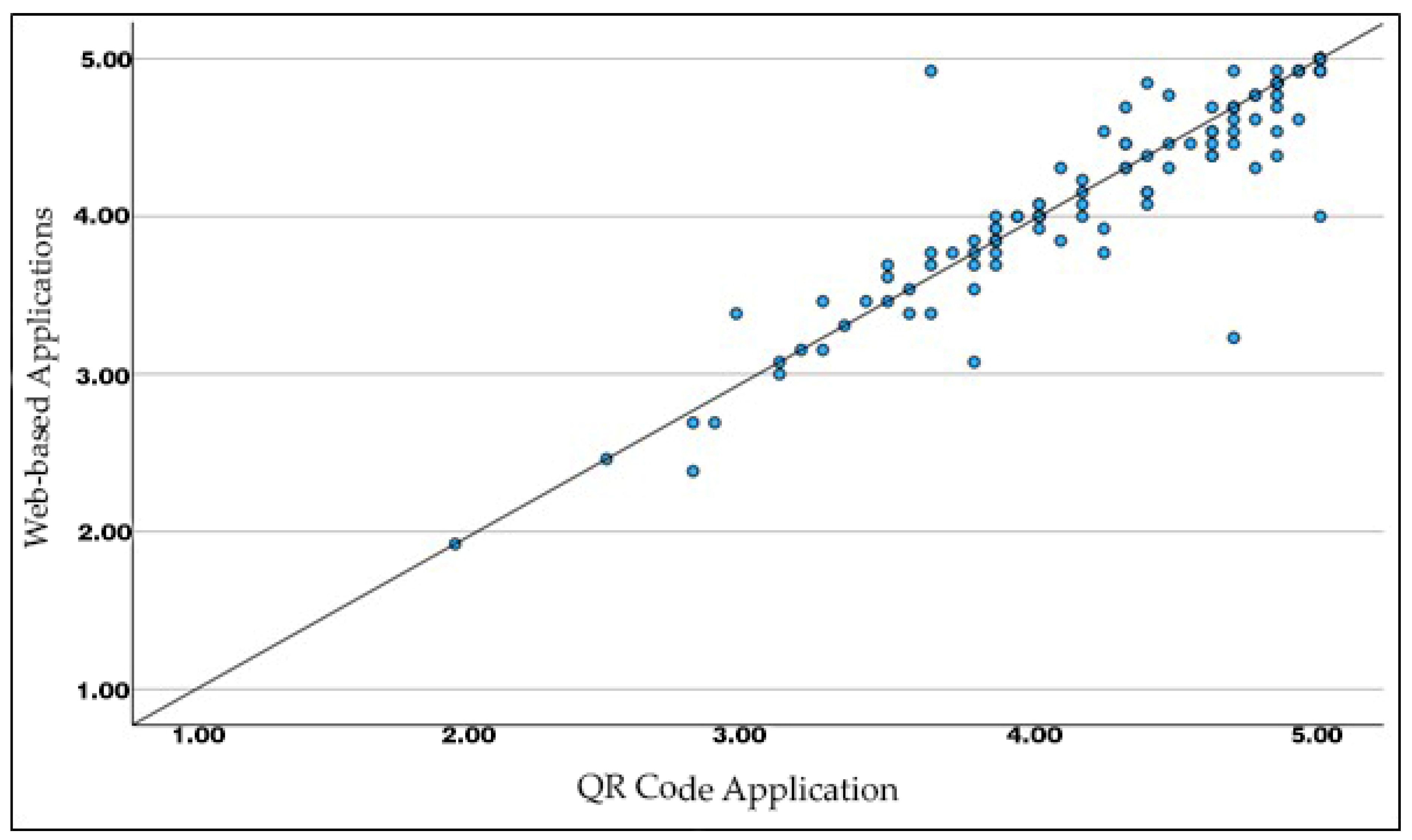

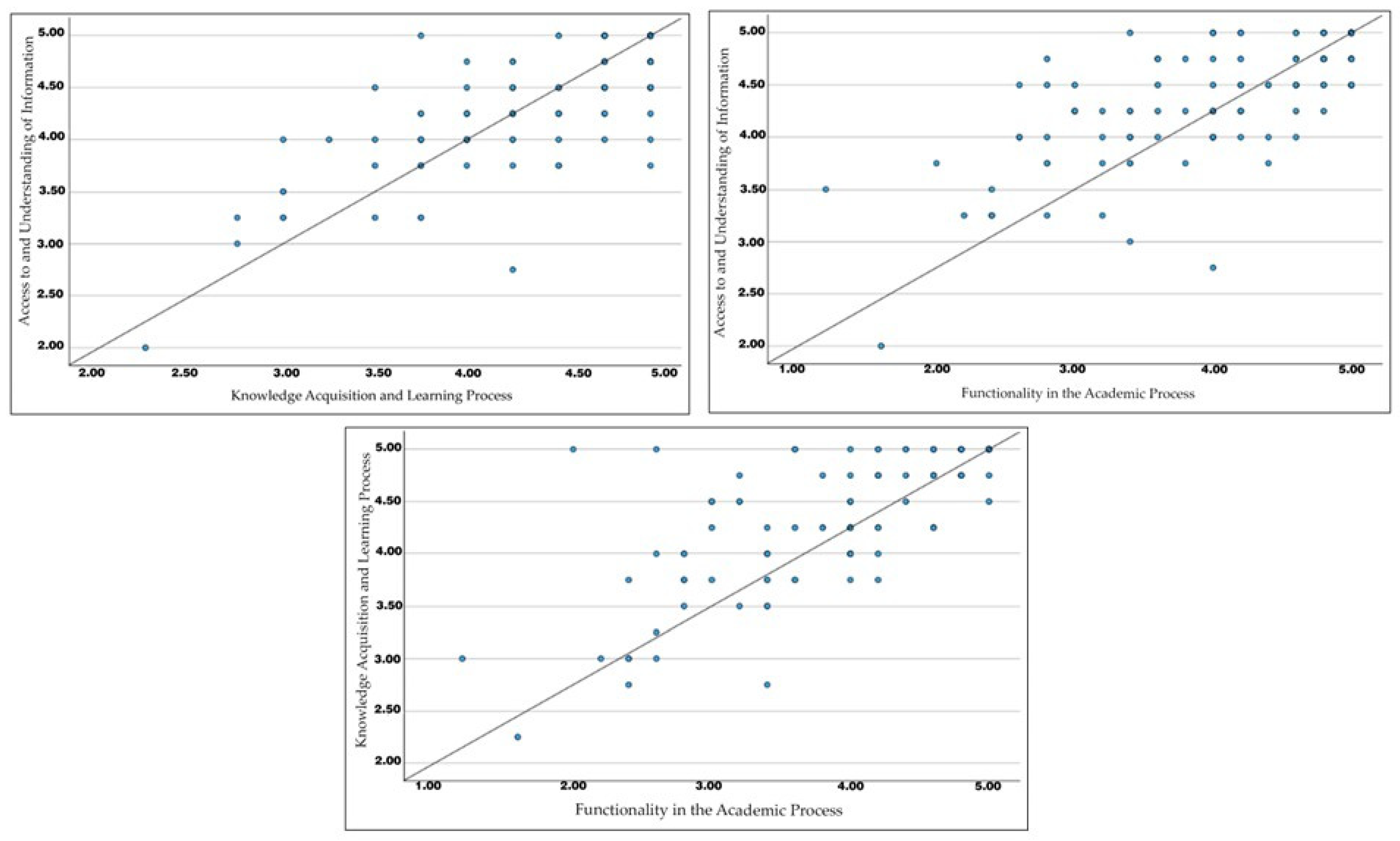

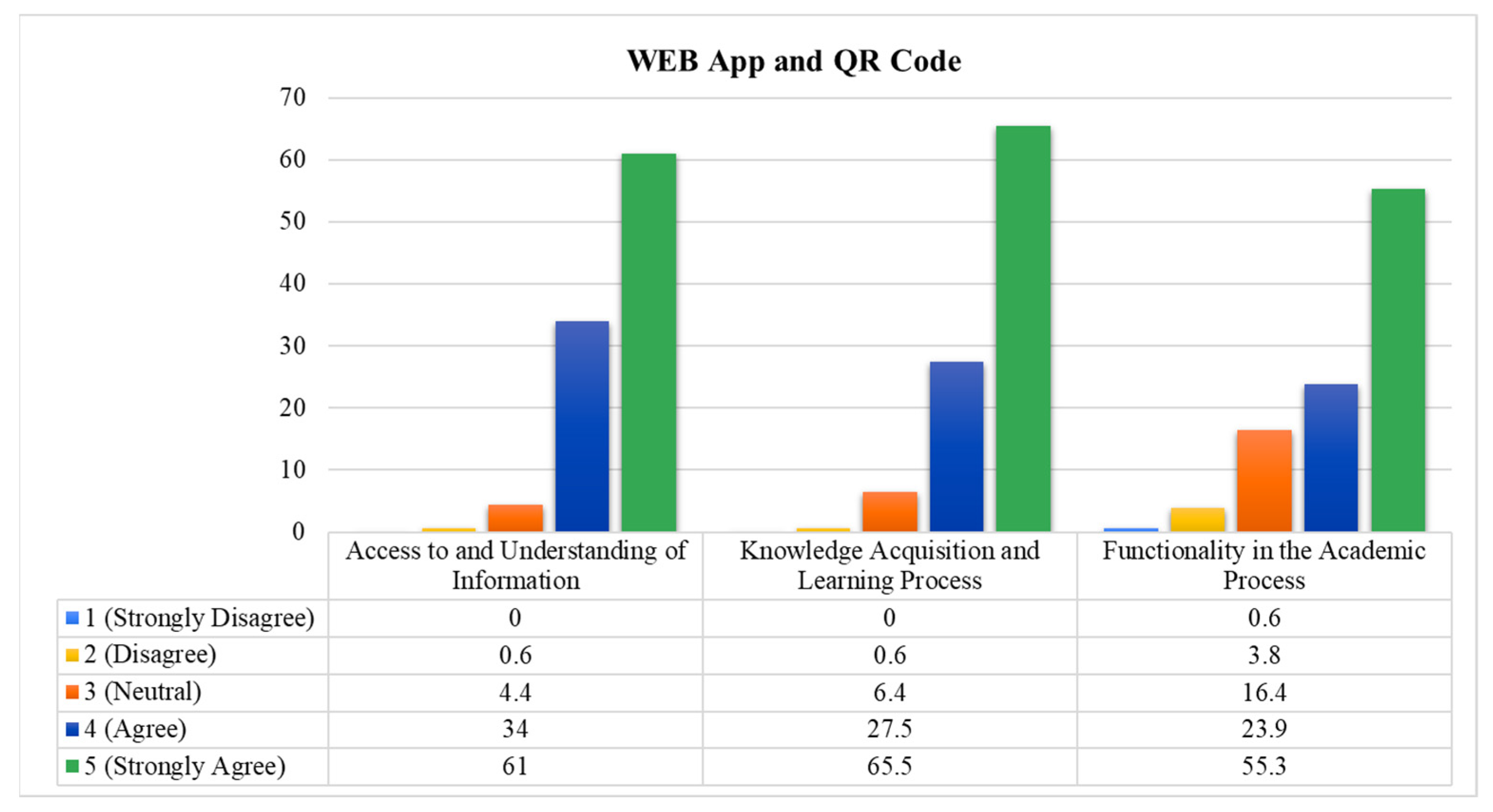

3.2.3. Integrated Evaluation of the Web-Based and QR Code Applications

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BUU | Bursa Uludag University |

| GIS | Geographic Information Systems |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| QR | Quick Response |

| SPSS | Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

References

- Min-Allah, N.; Alrashed, S. Smart campus—A sketch. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 59, 102231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berawi, M.A. Fostering smart city development to enhance quality of life. Int. J. Technol. 2022, 13, 454–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singgih, I.K.; Prabowo, A.R.; Soegiharto, S.; Singgih, M.L.; Dharma, F.P. Smart campus applications: A literature review on transportation research and big data. Int. J. Technol. 2025, 16, 796–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Looi, C.K.; Seow, P.; Chia, G.; Wong, L.H.; Chen, W.; So, H.J.; Soloway, E.; Norris, C. Deconstructing and reconstructing: Transforming primary science learning via a mobilized curriculum. Comput. Educ. 2010, 55, 1504–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rikala, J.; Kankaanranta, M. Blending classroom teaching and learning with qr codes. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Mobile Learning, Madrid, Spain, 28 February–2 March 2014; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karia, C.T.; Hughes, A.; Carr, S. Uses of quick response codes in healthcare education: A scoping review. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, J.A.; Rosa-Napal, F.C.; Romero-Tabeayo, I.; López-Calvo, S.; Fuentes-Abeledo, E.-J. Digital tools and personal learning environments: An analysis in higher education. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trang, T.T.T. How can learners study at their own pace and improve their autonomy? Int. J. Innov. Appl. Stud. 2021, 33, 618–624. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, T.H.; Bramner, N.; Sakata, N. Self-directed learning and student-centred learning: A conceptual comparison. Pedagog. Cult. Soc. 2023, 33, 847–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Correia, A.P.; Kim, Y.M. Determining mobile learning acceptanceoutside the classroom: An integrated acceptance model. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2025, 73, 2839–2859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, J.N.; O’Brien, M.P.; Costin, Y. Investigating student engagement with intentional content: An exploratory study of instructional videos. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2021, 19, 100505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Pooly, E.; Casteleijn, D.; Franzsen, D. Personalized adaptive learning in higher education: A scoping review of key characteristics and impact on academic performance and engagement. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kankaanranta, M.; Rikala, J. The use of quick response codes in the classroom. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 2012, 35, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Kashifi, T.M.; Jamal, A.; Kashefi, M.S.; Almoshaogeh, M.; Rahman, S.M. Predicting the travel mode choice with interpretable machine learning techniques: A comparative study. Travel Behav. Soc. 2022, 29, 279–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherheș, V.; Stoian, C.E.; Fărcașiu, M.A.; Stanici, M. E-learning vs. face-to-face learning: Analyzing students’ preferences and behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, F.; Dennen, V.P.; Bonk, C.J. Systematic reviews of research on online learning: An introductory look and review. Online Learn. 2023, 27, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, A.; Chen, X. Online education and its effective practice: A research review. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Res. 2016, 15, 157–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golden, R.E.; Klap, R.; Carney, D.V.; Yano, E.M.; Hamilton, A.B.; Taylor, S.L.; Kligler, B.; Whitehead, A.M.; Saechao, F.; Zaiko, Y.; et al. WH-PBRN-CIH Writing Group. Promoting Learning Health System Feedback Loops: Experience with a VA Practice-Based Research Network Card Study. Healthcare 2021, 8, 100484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandars, J. Cost Effectiveness in Medical Education; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, K.H.; Tsai, C.C. A case study of immersive virtual field trips in an elementary classroom: Students’ learning experience and teacher–student interaction behaviors. Comput. Educ. 2019, 140, 103600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibáñez, M.B.; Delgado-Kloos, C. Augmented reality for STEM learning: A systematic review. Comput. Educ. 2018, 123, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardestani, M.S.F.; Adibi, S.; Golshan, A.; Sadeghian, P. Factors influencing the effectiveness of e-learning in healthcare: A fuzzy anp study. Healthcare 2023, 11, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Coşkunserçe, O. Use of a mobile plant identification application and the out-of-school learning method in biodiversity education. Ecol. Evol. 2024, 14, e10957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balas, B.; Momsen, J.L. Attention “blinks” differently for plants and animals. CBE—Life Sci. Educ. 2014, 13, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polin, K.; Yiğitcanlar, T.; Limb, M.; Washington, T. The Making of Smart Campus: A Review and Conceptual Framework. Buildings 2023, 13, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naveed, Q.N.; Choudhary, H.; Ahmad, N.; Alqahtani, J.; Qahmash, A.I. Mobile Learning in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, J.I. Messy ecosystems, orderly frames. Landsc. J. 1995, 14, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francini, A.; Romano, D.; Toscano, S.; Ferrante, A. The contribution of ornamental plants to urban ecosystem services. Earth 2022, 3, 1258–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, G.; Alvarez, E.E. Landscape Design: Aesthetic Characteristics of Plants; UF/IFAS Extension; Environmental Horticulture Department: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2025; Available online: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Tukiran, J.M. Explore plants with QR code features in campus areas. Natl. Creat. Des. Dig. 2022, 7, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wandersee, J.H.; Schussler, E.E. Preventing Plant Blindness. Am. Biol. Teach. 1999, 61, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J. Construction and Reform Practice of Landscape Plant Course Group in Landscape Architecture under the Background of Emerging Engineering Education. In Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Language, Innovative Education and Cultural Communication (CLEC 2024), Wuhan, China, 26–28 April 2024; Khan, I.A., Yu, Z., Cüneyt Birkök, M., Yazid, A., Bakar, A., Eds.; The Atlantis Press: Paris, France, 2024; p. 533. [Google Scholar]

- Uno, G.E. Botanical literacy: What and how should students learn about plants? Am. J. Bot. 2009, 96, 1753–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pratiwi, M.; Asyhari, A.; Komikesari, H. QR Code system for plant identification at Raden Intan Lampung State Islamic University. E3S Web Conf. 2024, 482, 05009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettit, L.; Pye, M.; Wang, X.; Quinnell, R. Designing a bespoke App to address Botanical literacy in the undergraduate science curriculum and beyond. In Proceedings of the ASCILITE 2014 Conference, Rhetoric and Reality: Critical Perspectives on Educational Technology, Dunedin, New Zealand, 23–26 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- de Fatima Rocha Prestes, R.; Cordeiro, P.H.F.; Periotto, F.; Barón, D. Qr code technology in a sensory garden as a study tool. Ornam. Hortic. 2020, 26, 220–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilous, L.; Samoilenko, V.; Shyshchenko, P.; Havrylenko, O. GIS in landscape architecture and design. Eur. Assoc. Geosci. Eng. Geoinformatics 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrough, P.A.; McDonnells, R.A. Principles of Geographical Information Systems; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kodmany, K. GIS in the Urban Landscape: Reconfiguring Neighborhood Planning and Design Processes. J. Landsc. Res. 2000, 25, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.V.; Patil, P.P.; Toradmal, A.B. Application of quick response (QR) code for digitalization of plant taxonomy. J. Inf. Comput. Sci. 2020, 10, 1287–1293. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, K.; Agrawal, M.; Mahla, A.; Nagar, K.; Sehrawat, A.R. Interactive digital botanical keys: A scalable QR code-based platform for plant identification and experiential taxonomy pedagogy in academic campus ecosystems. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 11, 2975–2980. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 2nd ed.; SAGE Publishing: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gökçek, T. Karma yöntem araştırması. In Eğitimde Bilimsel Araştırma Yöntemleri Içinde; Metin, M., Ed.; Pegem A Yayıncılık: Ankara, Turkey, 2014; pp. 375–407. [Google Scholar]

- Katıtaş, S. A holistic overview of the mixed method research. Int. Soc. Sci. Stud. J. 2019, 5, 6250–6260. [Google Scholar]

- Landscapeplants. Available online: https://peyzajbitkileri.uludag.edu.tr/ (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Özdemir, M. Qualitative data analysis: A study on methodology problem in social sciences. Eskişehir Osman. Univ. J. Soc. Sci. 2010, 11, 323–343. [Google Scholar]

- Kıral, B. Document analysis as a qualitative data analysis method. J. Soc. Sci. Instute 2020, 15, 170–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cheon, J.; Lee, S.; Crooks, S.M.; Song, J. An investigation of mobile learning readiness in higher education based on the theory of planned behavior. Comput. Educ. 2012, 59, 1054–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmaz, F.; Pekgör, A. About Likert type scale development applications. Ulus. Eğitim Derg. 2023, 3, 506–519. [Google Scholar]

- Vural, H. Tarım Ve Gida Ekonomisi Istatistiği; Uludağ University Faculty of Agriculture: Bursa, Turkey, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kartal, S.K.; Dirlik, E.M. Historical development of the concept of validity and the most preferred technique of reliability: Cronbach alpha coefficient. Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal Univ. J. Fac. Educ. (BAIBUEFD) 2016, 16, 1865–1879. [Google Scholar]

- Terzi, Y. Anket, Güvenilirlik—Geçerlilik Analizi; Lecture Notes; Ondokuz Mayis University, Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Department of Statistics: Samsun, Turkey, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Öztürk, E.E. Korelasyon Analizi(r) Nedir? 2020. Available online: https://www.veribilimiokulu.com/korelasyon-analizir-nedir (accessed on 31 October 2025).

- Lai, H.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Wen-Shiane, L.; Fan, Y.L.; Wu, Y.T. The implementation of mobile learning in outdoor education: Application of QR codes. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 44, E57–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagajyothi, R.; Murugalakshmikumari, R.; Jyothimani, V.G. Identification of trees using QR code in college campus. Int. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. Sci. 2023, 7, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, S.; Bedage, S.; Salunkhe, M.; Mhetre, S.A.; Mohite, S.; Sutar, S. Digitalizing green: QR code-based plant accessing system for awareness and conservation. Int. Res. J. Adv. Eng. Manag. 2025, 6, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Student Feedback Form on the Mobile Application and QR Code Experience in Woody Landscape Plant Learning |

|---|---|

| Q1 | I frequently use the mobile application to access information on woody landscape plants. |

| Q2 | I find mobile applications that provide access to information on woody landscape plants valuable. |

| Q3 | Mobile applications have been useful in accessing practical information about woody landscape plants. |

| Q4 | Mobile applications have increased my awareness and knowledge of woody landscape plant species. |

| Q5 | Mobile applications were effectively used in my courses related to plant materials. |

| Q6 | Mobile applications have helped me learn the ecological requirements (e.g., light, soil, moisture) of woody landscape plants. |

| Q7 | Mobile applications have helped me learn the general characteristics (e.g., origin, height, crown diameter) of woody landscape plants. |

| Q8 | Mobile applications were effectively used in my planting design courses. |

| Q9 | Mobile applications have been useful in understanding the design uses of woody landscape plants (e.g., in coastal areas, gardens, as solitary elements). |

| Q10 | Mobile applications were effectively used in my project-based courses. |

| Q11 | Mobile applications were effectively used in my planning courses. |

| Q12 | Mobile applications supported the development of original compositions in my project-based courses. |

| Q13 | Mobile applications have contributed significantly to my professional development. |

| Parameters | Related Questions |

|---|---|

| Access to and Understanding of Information | Q1, Q2, Q4, Q13 |

| Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | Q3, Q6, Q7, Q9 |

| Functionality in the Academic Process | Q5, Q8, Q10, Q11, Q12 |

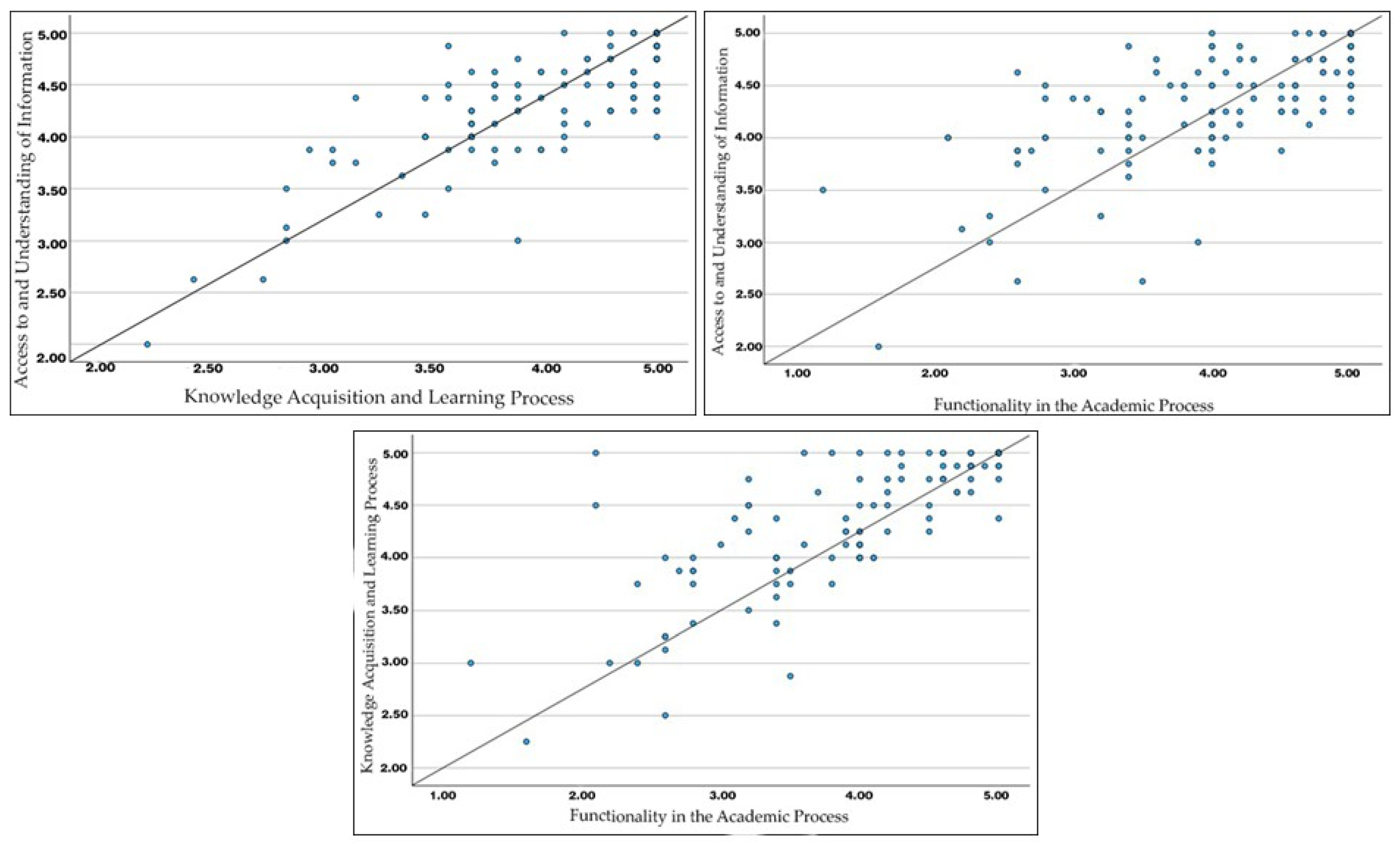

| Parameters | Access to and Understanding of Information | Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | Functionality in the Academic Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to and Understanding of Information | 1 | ||

| Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | 0.805 ** | 1 | |

| Functionality in the Academic Process | 0.705 ** | 0.822 ** | 1 |

| Parameters | Access to and Understanding of Information | Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | Functionality in the Academic Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to and Understanding of Information | 1 | ||

| Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | 0.814 ** | 1 | |

| Functionality in the Academic Process | 0.776 ** | 0.812 ** | 1 |

| Parameters | Access to and Understanding of Information | Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | Functionality in the Academic Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to and Understanding of Information | 1 | ||

| Knowledge Acquisition and Learning Process | 0.839 ** | 1 | |

| Functionality in the Academic Process | 0.766 ** | 0.829 ** | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Altun, G.; Zencirkıran, M. A Web-Based Learning Model for Smart Campuses: A Case in Landscape Architecture Education. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411203

Altun G, Zencirkıran M. A Web-Based Learning Model for Smart Campuses: A Case in Landscape Architecture Education. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411203

Chicago/Turabian StyleAltun, Gamze, and Murat Zencirkıran. 2025. "A Web-Based Learning Model for Smart Campuses: A Case in Landscape Architecture Education" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411203

APA StyleAltun, G., & Zencirkıran, M. (2025). A Web-Based Learning Model for Smart Campuses: A Case in Landscape Architecture Education. Sustainability, 17(24), 11203. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411203