The Spillover Effect of National Auditing on the ESG Performance of Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of China’s NAO Auditing SOEs

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses Development

2.1. National Auditing and the ESG Performance of Supply Chains

2.2. The Mechanism Between National Auditing and the ESG Performance of Supply Chains

2.3. The Heterogeneity Between National Auditing and ESG Performance of Supply Chains

2.3.1. The Heterogeneity of Cooperation Stability Among Supply Chain Enterprises

2.3.2. The Heterogeneity of Concentration Among Supply Chains

2.3.3. The Heterogeneity of Supply Chain Enterprises Across Different Industries

3. Research Design

3.1. Data Sources and Processing

3.2. Variable Descriptions

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Explanatory Variable

3.2.3. Control Variables

3.3. Empirical Model

4. Empirical Results and Analysis

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Analysis of the Results of the Baseline Regression Results

4.3. Robustness Test

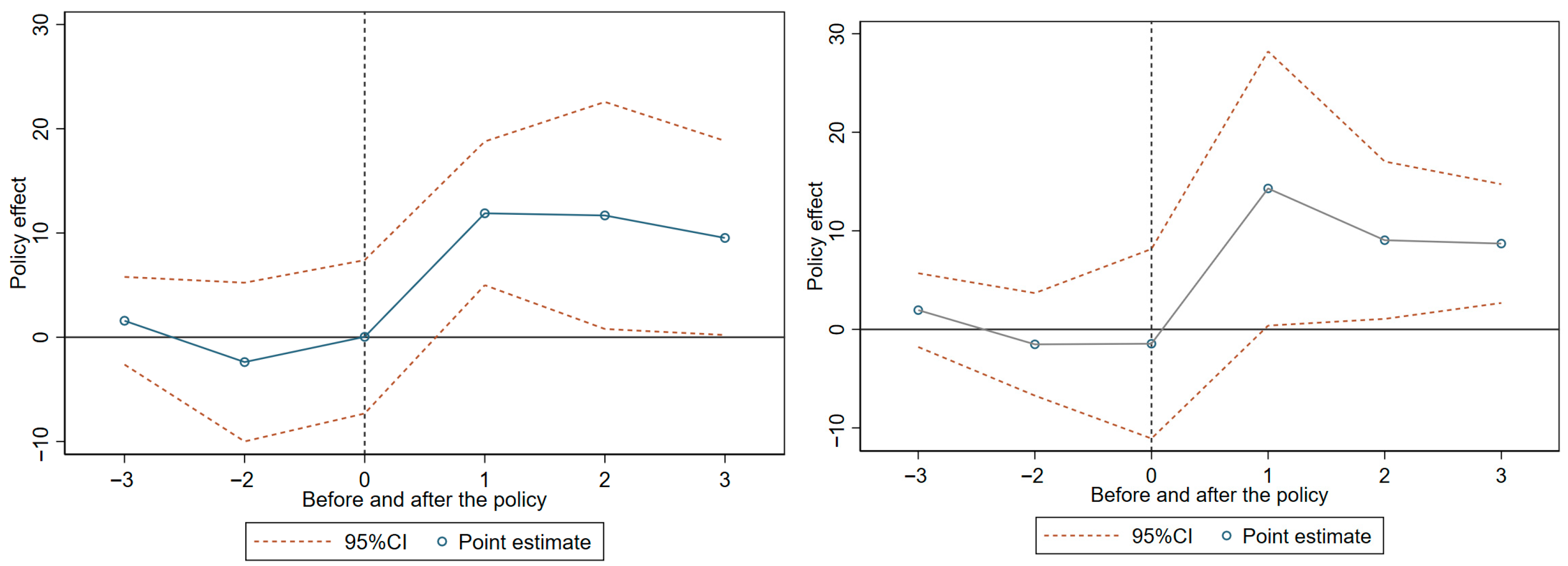

4.3.1. Parallel Trend Test

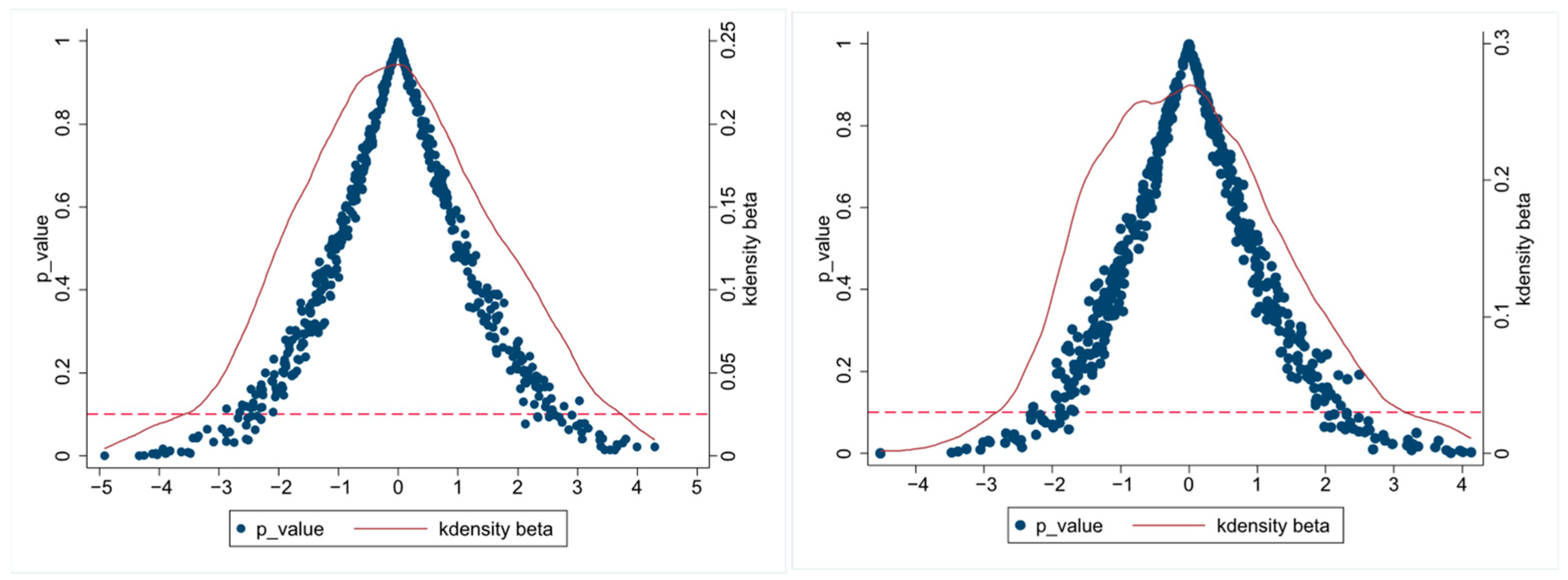

4.3.2. Placebo Test

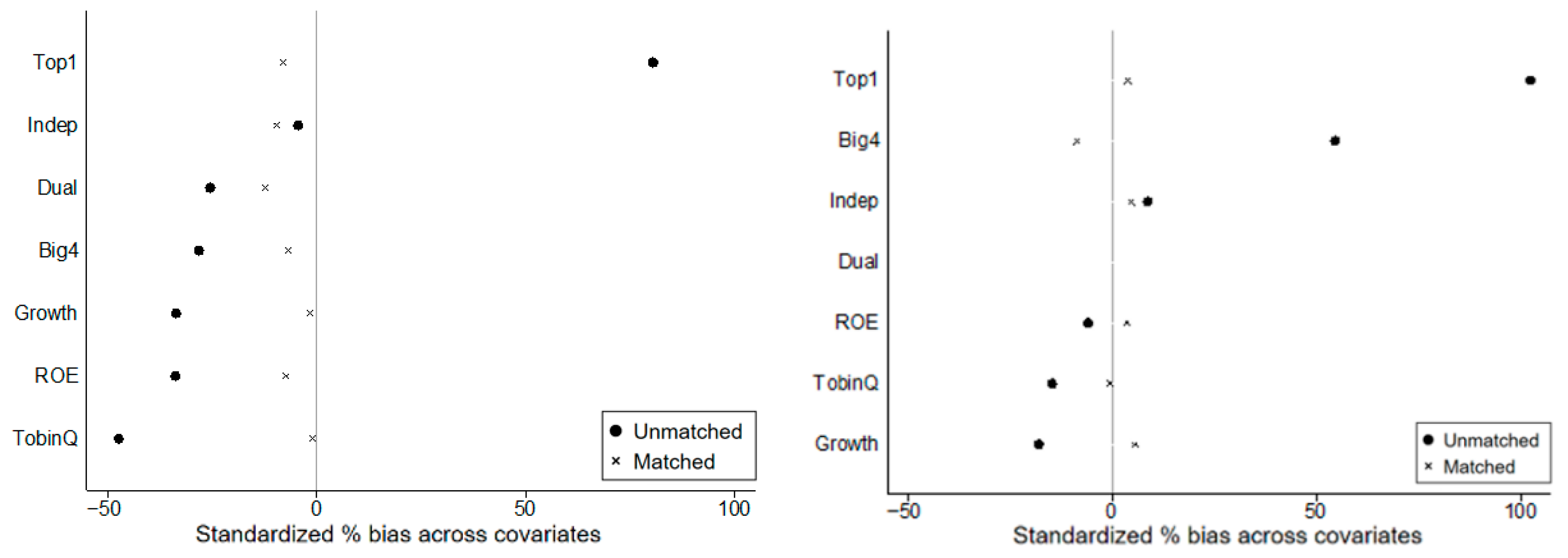

4.3.3. PSM-DID Test

4.3.4. Changing the Measurement Method of the Explanatory Variable

4.3.5. GMM Regression

4.3.6. Heckman Two-Step Method

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. The Heterogeneity Test of Cooperation Stability

- Step 1: Extract the list of the top 5 suppliers/clients disclosed annually by each audited SOE from the “Supplier-Client Relationship” module of the CSMAR database.

- Step 2: For each supplier/client matched with the audited SOE, count how many times it appears in the top 5 list over three consecutive years.

- Step 3: Calculate the 3-year average appearance frequency.

4.4.2. The Heterogeneity Test of Concentration

4.4.3. The Heterogeneity Test on Supply Chains Across Different Industries

4.5. Further Discussion: Mechanism Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Composite Metric | Environmental Investment | Social Donation | Corporate Governance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Metric | 1 | 0.542 *** (0.000) | 0.609 *** (0.000) | 0.255 *** (0.002) |

| Environmental Investment | 0.513 *** (0.000) | 1 | 0.373 *** (0.000) | 0.208 ** (0.013) |

| Social Donation | 0.682 *** (0.000) | 0.163 ** (0.038) | 1 | 0.184 ** (0.027) |

| Corporate Governance | 0.502 *** (0.000) | 0.937 *** (0.000) | 0.144 *** (0.067) | 1 |

| Variable | S_ESG | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Composite Metric | Huazheng | Bloomberg | |

| AuditPost | 0.068 * (0.037) | 0.335 * (0.194) | 5.088 *** (1.502) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 1262 | 1262 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.650 | 0.312 | 0.730 |

| Variable | C_ESG | ||

| CompositeMetric | Huazheng | Bloomberg | |

| AuditPost | 0.035 * (0.020) | 0.313 * (0.183) | 2.700 * (1.500) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1395 | 1395 | 1395 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.345 | 0.091 | 0.665 |

References

- Edmans, A. The end of ESG. Financ. Manag. 2023, 52, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Jiang, F.; Pan, J.; Cai, Q. Financial innovation, government auditing and corporate high-quality development: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Zhang, Y. National auditing informatization and green innovation in state-owned enterprises: A quasi-natural experiment based on the establishment of specialized institutions for audit informatization. Audit Res. 2024, 4, 30–42. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, W.; Gao, Y. National auditing and regional innovation input: An analysis based on provincial panel data. J. Audit Econ. 2024, 39, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Kane, A.D.; Soar, J.; Armstrong, R.A.; Kursumovic, E.; Davies, M.T.; Oglesby, F.C. Patient characteristics, anaesthetic workload and techniques in the UK: An analysis from the 7th National Audit Project (NAP7) activity survey. Anaesthesia 2023, 78, 701–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Thoughts of conducting departure auditing on natural resources assets of leading cadres. Audit Res. 2014, 5, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.; Fang, J.; Qin, X. Can government auditing promote innovation in state-owned enterprises? J. Audit Econ. 2018, 33, 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez Melendez, E.I.; Bergey, P.; Smith, B. Blockchain technology for supply chain provenance: Increasing supply chain efficiency and consumer trust. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2024, 29, 706–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, X.; Shi, G.; Yu, Z. ESG performance and enterprise value in China: A novel approach via a regulated intermediary model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, A.; Taglialatela, J.; Testa, F.; Iraldo, F. Determinants of environmental social and governance (ESG) performance: A systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 456, 142213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clemens, B.W.; Douglas, T.J. Understanding strategic responses to institutional pressures. J. Bus. Res. 2005, 58, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Lockhart, J.; Bathurat, R. The institutional analysis of CSR: Learnings from an emerging country. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2021, 46, 100–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baratta, A.; Cimino, A.; Longo, F.; Solina, V.; Verteramo, S. The impact of ESG practices in industry with a focus on carbon emissions: Insights and future perspectives. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henisz, W.; Koller, T.; Nuttall, R. Five ways that ESG creates value. McKinsey Q. 2019, 4, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, F.M.; Kurrahman, T.; Chiu, A.S.; Fan, S.K.S.; Lim, M.K.; Tseng, M.L. Optimization techniques for green supply chain practice challenges: A systematic hybrid approach. Eng. Optim. 2025, 57, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, S.; Choukolaei, H.A. A systematic review of green supply chain network design literature focusing on carbon policy. Decis. Anal. J. 2023, 6, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Wang, P. Research on institutional pressure and group behavior of green technology diffusion in enterprises. Chin. Soft Sci. 2024, 5, 197–209. [Google Scholar]

- Khababa, N.; Jalingo, M.U. Impact of green finance, green investment, green technology on SMEs sustainability: Role of corporate social responsibility and corporate governance. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Stud. 2023, 15, 438–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG investing: How ESG affects equity valuation, risk, and performance. J. Portf. Manag. 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, X. Does customer stock price crash risk have a contagious effect on suppliers? J. Financ. Econ. 2018, 44, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, R.; Bryde, D.J.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Graham, G.; Foropon, C.; Papadopoulos, T. Dynamic digital capabilities and supply chain resilience: The role of government effectiveness. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2023, 258, 108790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, R.K.; Garg, D.; Agarwal, A. Understanding of supply chain: A literature review. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2011, 3, 2059–2072. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, Y.; Ma, D.; Sun, L. Customer concentration and corporate risk-taking. J. Financ. Stab. 2021, 54, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M.; Searcy, C.; Castka, P. ESG and Industry 5.0: The role of technologies in enhancing ESG disclosure. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2023, 195, 122806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, W.; Liu, K.; Tao, Y.; Ye, Y. Digital finance and corporate ESG. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 51, 103426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farida, I.; Setiawan, D. Business strategies and competitive advantage: The role of performance and innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ma, C. Spillover effects of descriptive innovation information disclosure by peer companies: Based on machine learning and text analysis. Sci. Technol. Prog. Policy 2024, 41, 22–32. [Google Scholar]

- Pfotenhauer, S.M.; Wentland, A.; Ruge, L. Understanding regional innovation cultures: Narratives, directionality, and conservative innovation in Bavaria. Res. Policy 2023, 523, 104704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y. Green credit policy, financing structure and enterprise ESG responsibility fulfillment: A quasi-natural experiment based on the Green Credit Guidelines. Rev. Investig. Stud. 2024, 43, 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Fu, C. Can government auditing improve enterprise social responsibility performance? Empirical evidence from the audit of central enterprises by the national audit office. J. Audit Econ. 2020, 35, 12–21. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Li, G. Dispersion or concentration: Client concentration and enterprise performance. Manag. Rev. 2023, 35, 294–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, D. Supply chain management integration and implementation: A literature review. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2005, 10, 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Explained variables | S_ESG | The entropy weight method integrates Huazheng and Bloomberg ESG data to construct a composite indicator |

| C_ESG | ||

| Explanatory variable | AuditPost | If the enterprise is audited, audited and following years are set to 1; otherwise, set to 0 |

| Control variables | ROE | Net assets/average balance of shareholder’s equity |

| Growth | Current annual revenue/previous year revenue-1 | |

| Indep | Number of independent directors/number of directors | |

| Dual | If the chairman and general manager is the same person, set it to 1; otherwise, set it to 0 | |

| Top1 | Largest shareholder’s shares/total shares | |

| Big4 | If the enterprise is audited by the Big 4 accounting firms, set it to 1; otherwise, set it to 0 | |

| TobinQ | (Circulation market value + non-circulation market value × BVPS + book value of liability)/total assets | |

| Province | Set to 1 for a specific province, otherwise 0 | |

| Industry | Set to 1 for a specific industry, otherwise 0 | |

| Year | Set to 1 for current year, otherwise 0 |

| Variable | Sample Size | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S_ESG | 1262 | 0.443 | 0.165 | 0.029 | 0.936 |

| S_AuditPost | 1262 | 0.070 | 0.254 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| S_ROE | 1262 | 0.083 | 0.131 | −0.962 | 0.414 |

| S_Growth | 1262 | 0.181 | 0.341 | −0.542 | 3.224 |

| S_Indep | 1262 | 37.378 | 5.243 | 27.270 | 57.140 |

| S_Dual | 1262 | 0.254 | 0.456 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| S_Top1 | 1262 | 0.048 | 0.163 | 0.084 | 0.758 |

| S_Big4 | 1262 | 0.149 | 0.356 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| S_TobinQ | 1262 | 1.759 | 1.181 | 0.789 | 9.817 |

| C_ESG | 1395 | 0.456 | 0.164 | 0.106 | 0.957 |

| C_AuditPost | 1395 | 0.033 | 0.179 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| C_ROE | 1395 | 0.098 | 0.113 | −0.724 | 0.420 |

| C_Growth | 1395 | 0.172 | 0.307 | −0.613 | 3.073 |

| C_Indep | 1395 | 37.835 | 5.819 | 27.270 | 60.000 |

| C_Dual | 1395 | 0.210 | 0.407 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| C_Top1 | 1395 | 0.381 | 0.164 | 0.081 | 0.758 |

| C_Big4 | 1395 | 0.236 | 0.425 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| C_TobinQ | 1395 | 1.634 | 0.947 | 0.789 | 8.732 |

| Variable | (1) S_ESG | (2) C_ESG |

|---|---|---|

| AuditPost | 0.068 * (0.037) | 0.035 * (0.020) |

| ROE | 0.067 (0.084) | 0.172 *** (0.049) |

| Growth | −0.073 ** (0.031) | 0.027 (0.019) |

| Indep | 0.003 (0.002) | 0.002 * (0.001) |

| Dual | 0.049 * (0.030) | −0.018 (0.014) |

| Top1 | −0.003 (0.098) | 0.002 *** (0.000) |

| Big4 | 0.042 (0.044) | 0.159 *** (0.013) |

| TobinQ | 0.002 (0.012) | −0.009 * (0.005) |

| _cons | −1.619 *** (0.362) | 0.273 *** (0.033) |

| Province FE | Yes | Yes |

| Industry FE | Yes | Yes |

| Year FE | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 1395 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.650 | 0.345 |

| Variable | (1) S_ESG | (2) C_ESG |

|---|---|---|

| AuditPost | 0.062 * (0.037) | 0.051 * (0.030) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| N | 951 | 1037 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.444 | 0.210 |

| Variable | S_ESG | C_ESG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Audit 3 | 0.072 * (0.044) | 0.064 * (0.037) | ||

| Audit 6 | 0.095 *** (0.049) | 0.081 ** (0.033) | ||

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 1262 | 1395 | 1395 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.635 | 0.639 | 0.475 | 0.401 |

| Variable | (1) S_ESG | (2) C_ESG |

|---|---|---|

| AuditPost | 0.025 *** (0.002) | 0.151 ** (0.075) |

| L. ESG | 0.014 *** (0.002) | 0.738 *** (0.037) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 1395 |

| AR (1) | 0.075 | 0.000 |

| AR (2) | 0.146 | 0.893 |

| Hansen Test | 0.996 | 0.472 |

| Variable | (1) S_ESG | (2) C_ESG |

|---|---|---|

| AuditPost | 0.135 *** (0.047) | 0.239 *** (0.021) |

| IMR | −2.755 *** (0.304) | −1.131 * (0.581) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1224 | 1339 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.301 | 0.582 |

| Variable | S_ESG | C_ESG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Short-Term Cooperation | Medium-Long-Term Cooperation | Short-Term Cooperation | Medium-Long-Term Cooperation | |

| AuditPost | 0.075 (0.071) | 0.271 * (0.142) | 0.001 (0.038) | 0.105 * (0.052) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 380 | 429 | 589 | 559 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.654 | 0.785 | 0.567 | 0.532 |

| Variables | S_ESG | C_ESG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| High-Reliable Group | Low-Reliable Group | High-Reliable Group | Low-Reliable Group | |

| AuditPost | 0.057 * (0.029) | 0.050 (0.060) | 0.301 * (0.160) | 0.027 (0.133) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 488 | 440 | 511 | 620 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.608 | 0.519 | 0.672 | 0.569 |

| Variables | S_ESG | C_ESG | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| Same Industry | Different Industry | Same Industry | Different Industry | |

| AuditPost | 0.242 * (0.112) | 0.028 (0.034) | 0.255 * (0.128) | 0.006 (0.027) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 451 | 586 | 542 | 656 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.721 | 0.431 | 0.516 | 0.567 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (1) | (2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Sample | Greater MP | Less MP | Full Sample | Greater MP | Less MP | |

| MP | S_ESG | S_ESG | MP | C_ESG | C_ESG | |

| ESG | −0.171 * (0.061) | 0.169 (0.222) | 0.287 * (0.165) | −0.130 * (0.071) | 0.189 (0.147) | 0.200 ** (0.094) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 630 | 629 | 1395 | 696 | 688 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.700 | 0.109 | 0.446 | 0.265 | 0.482 | 0.484 |

| Variable | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Samples | Greater CP | Less CP | Full Samples | Greater CP | Less CP | |

| CP | S_ESG | S_ESG | CP | C_ESG | C_ESG | |

| ESG | 0.032 * (0.016) | 0.019 (0.153) | 0.862 * (0.429) | 0.024 * (0.014) | 0.043 (0.134) | 0.230 * (0.103) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 631 | 631 | 1395 | 680 | 645 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.335 | 0.546 | 0.228 | 0.575 | 0.436 | 0.656 |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Samples | Greater NP | Less NP | Full Samples | Greater NP | Less NP | |

| NP | S_ESG | S_ESG | NP | C_ESG | C_ESG | |

| ESG | 0.045 ** (0.026) | 0.113 (0.190) | 0.392 ** (0.189) | 0.032 * (0.019) | 0.061 (0.094) | 0.259 ** (0.126) |

| Controls | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| N | 1262 | 619 | 630 | 1395 | 695 | 643 |

| Adj_R2 | 0.674 | 0.316 | 0.366 | 0.824 | 0.749 | 0.685 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Shangguan, X. The Spillover Effect of National Auditing on the ESG Performance of Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of China’s NAO Auditing SOEs. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411190

Wu H, Zhao X, Li Y, Shangguan X. The Spillover Effect of National Auditing on the ESG Performance of Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of China’s NAO Auditing SOEs. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411190

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Hui, Xiaoyu Zhao, Yixuan Li, and Xuming Shangguan. 2025. "The Spillover Effect of National Auditing on the ESG Performance of Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of China’s NAO Auditing SOEs" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411190

APA StyleWu, H., Zhao, X., Li, Y., & Shangguan, X. (2025). The Spillover Effect of National Auditing on the ESG Performance of Supply Chains: Empirical Evidence from the Quasi-Natural Experiment of China’s NAO Auditing SOEs. Sustainability, 17(24), 11190. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411190