Exploring Industrial Perception and Attitudes Toward Solar Energy: The Case of Albania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Climate Change and Global Warming

2.2. Solar Energy

3. Methodology

4. Empirical Findings

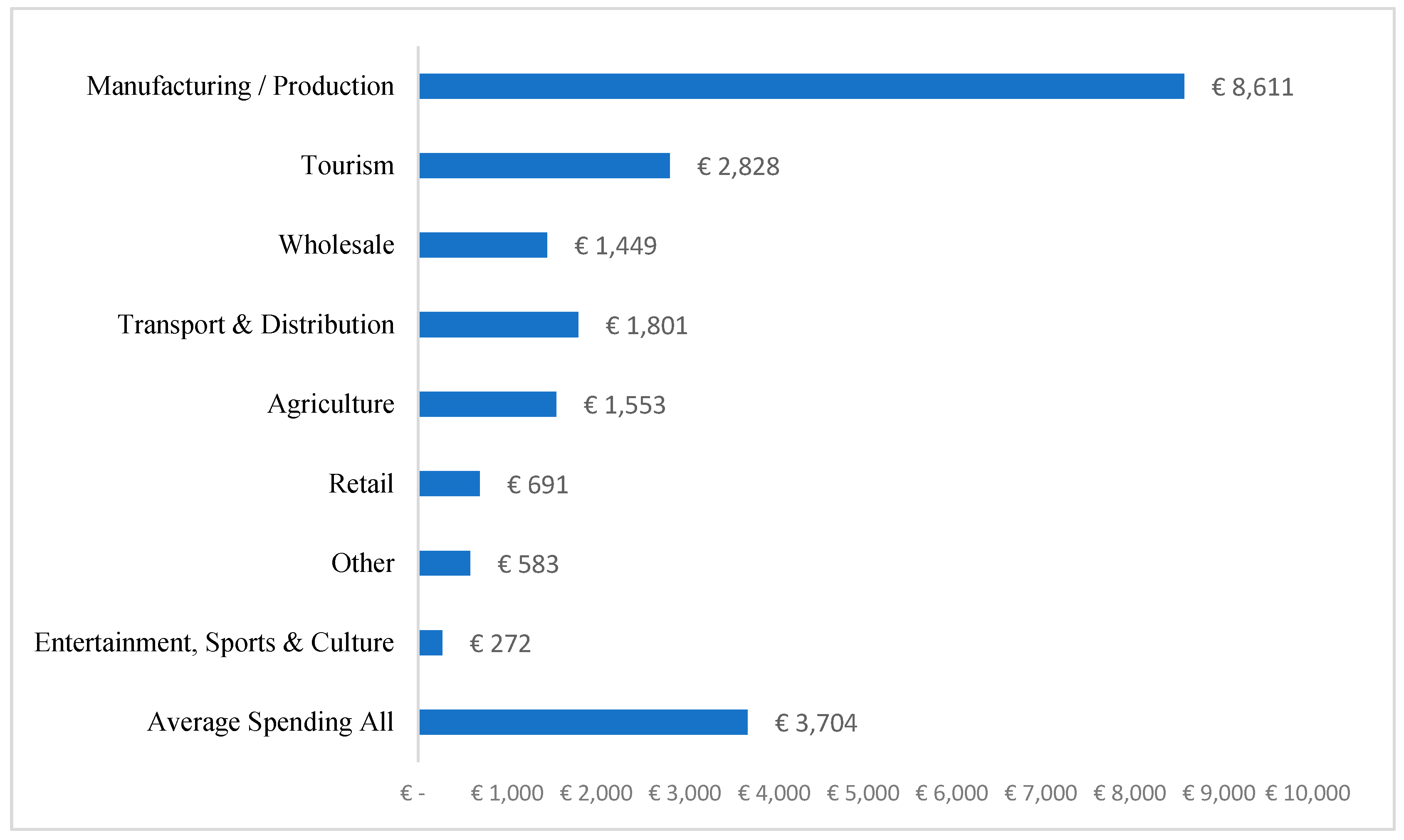

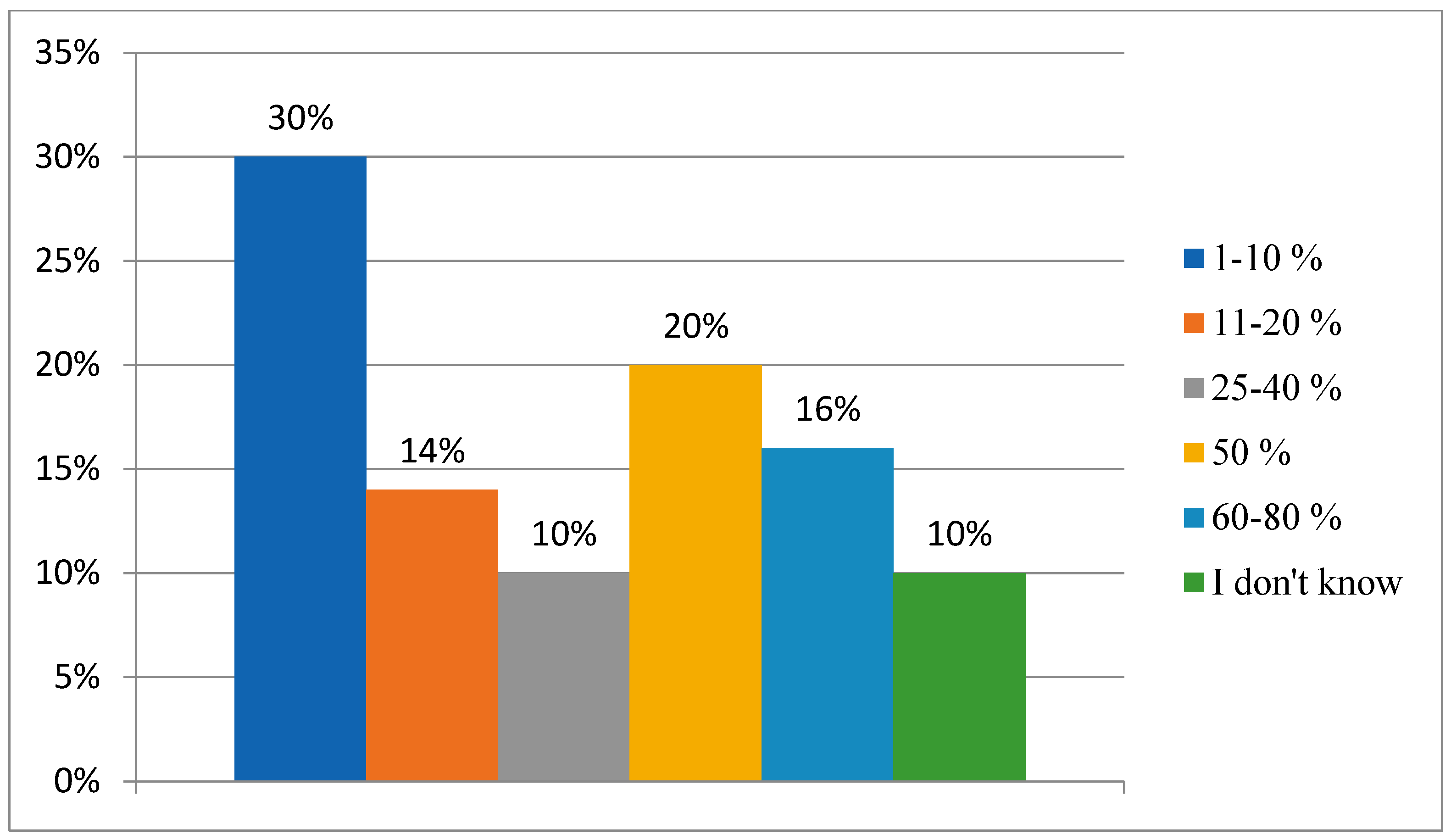

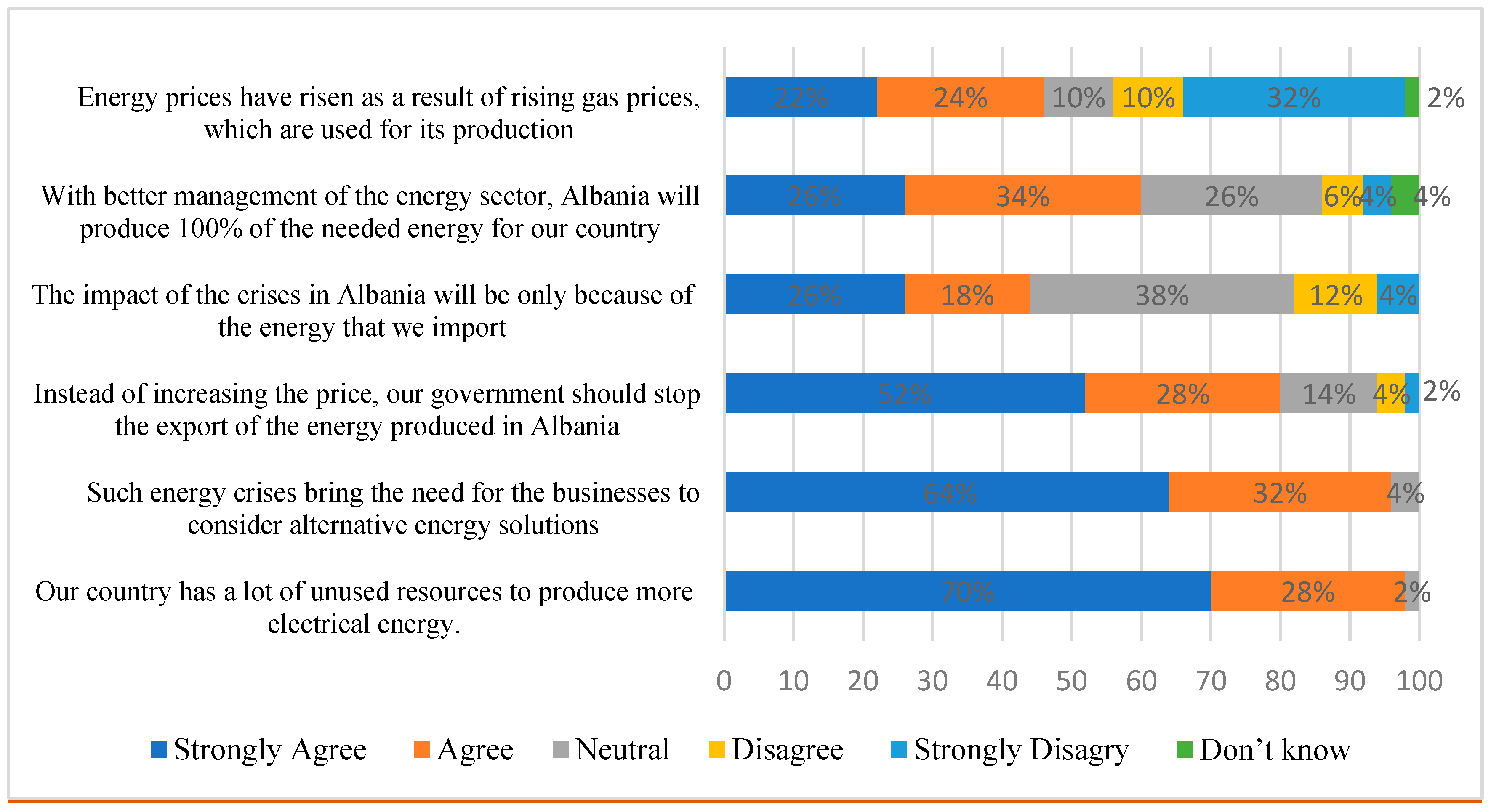

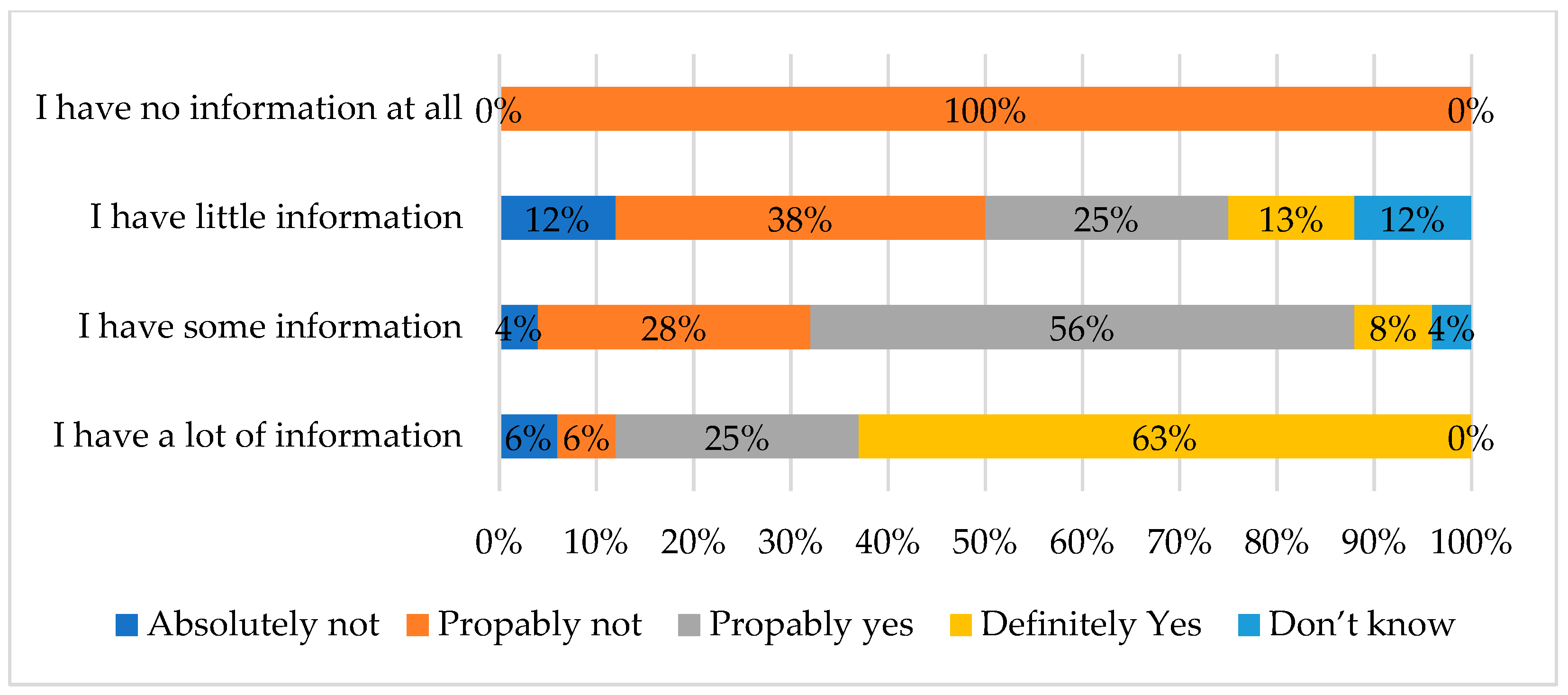

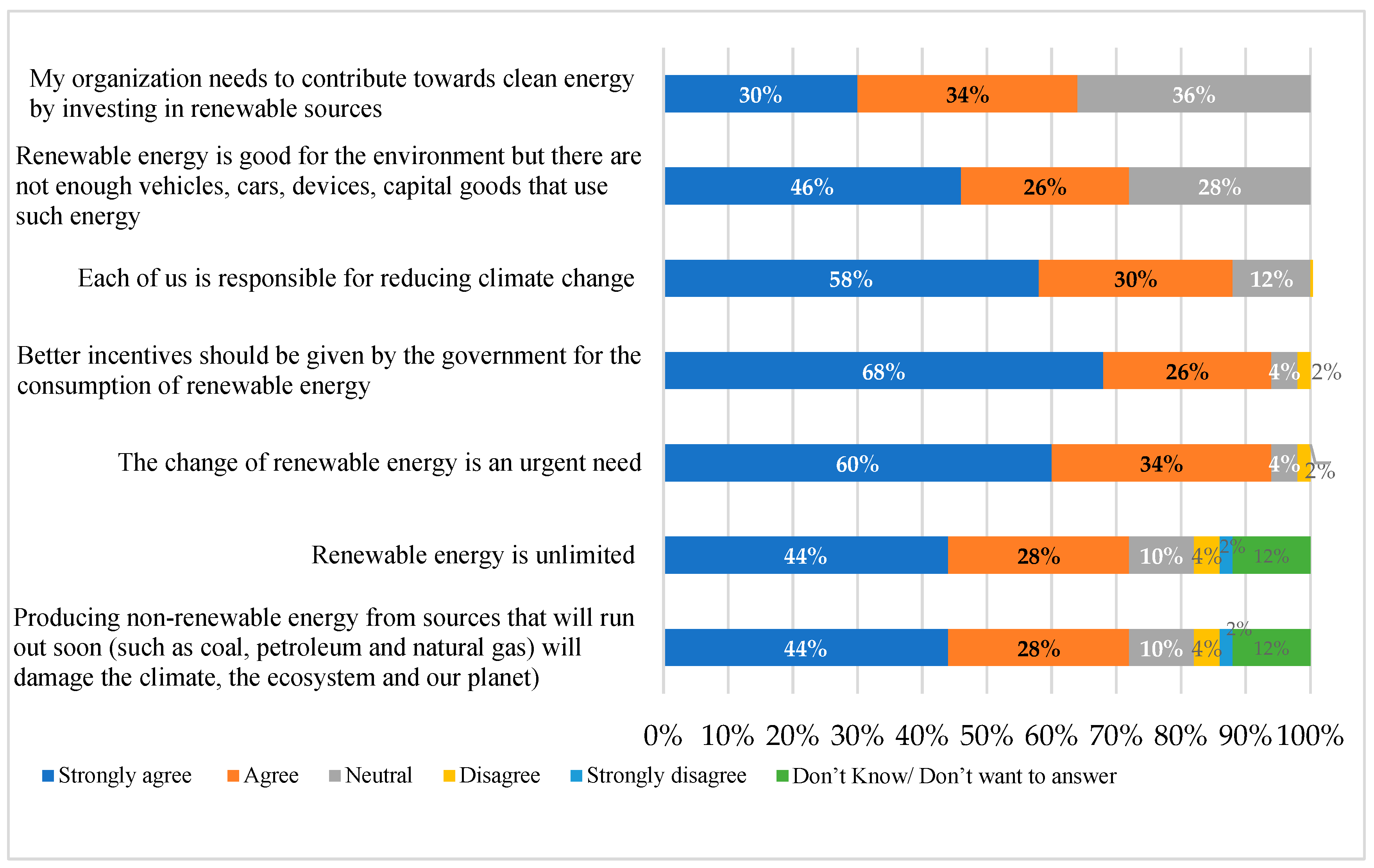

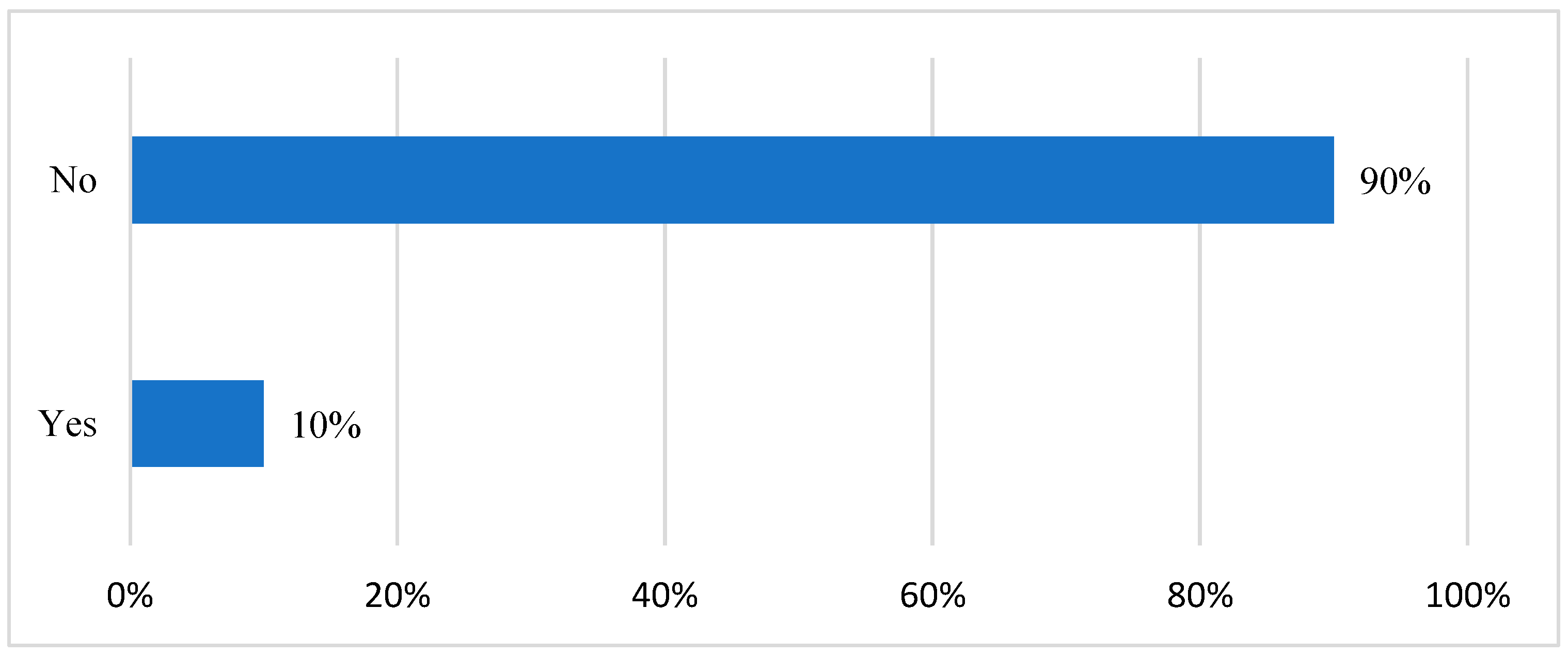

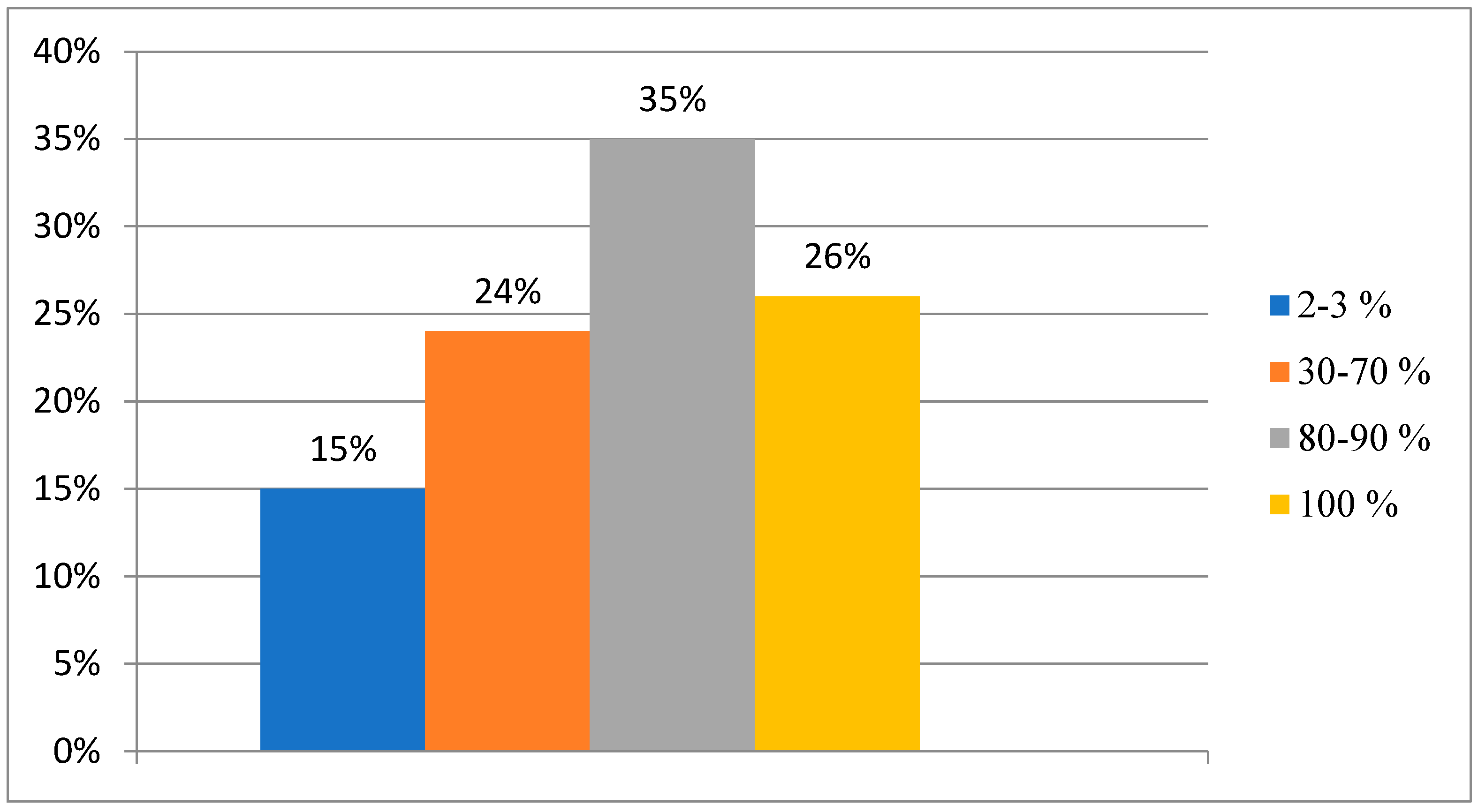

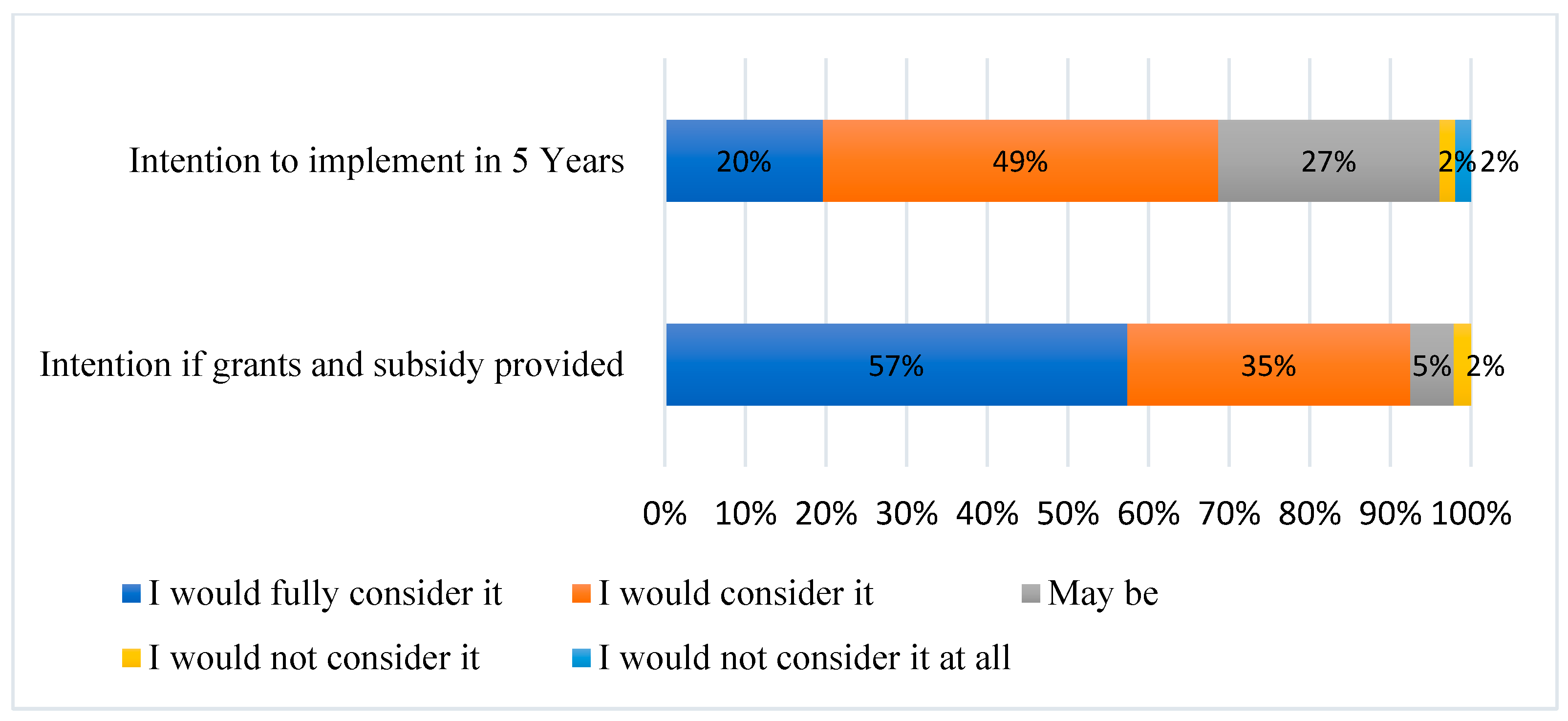

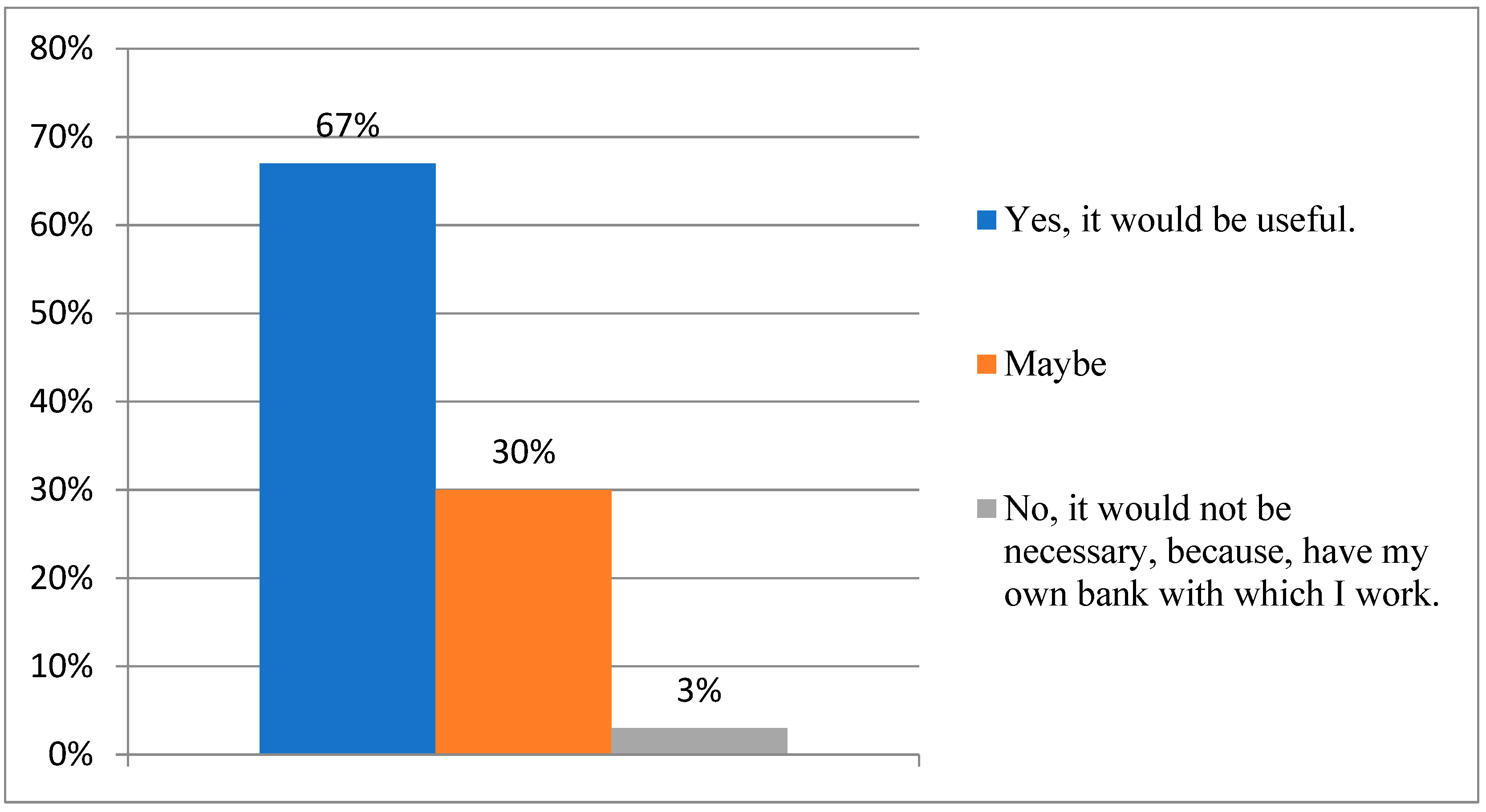

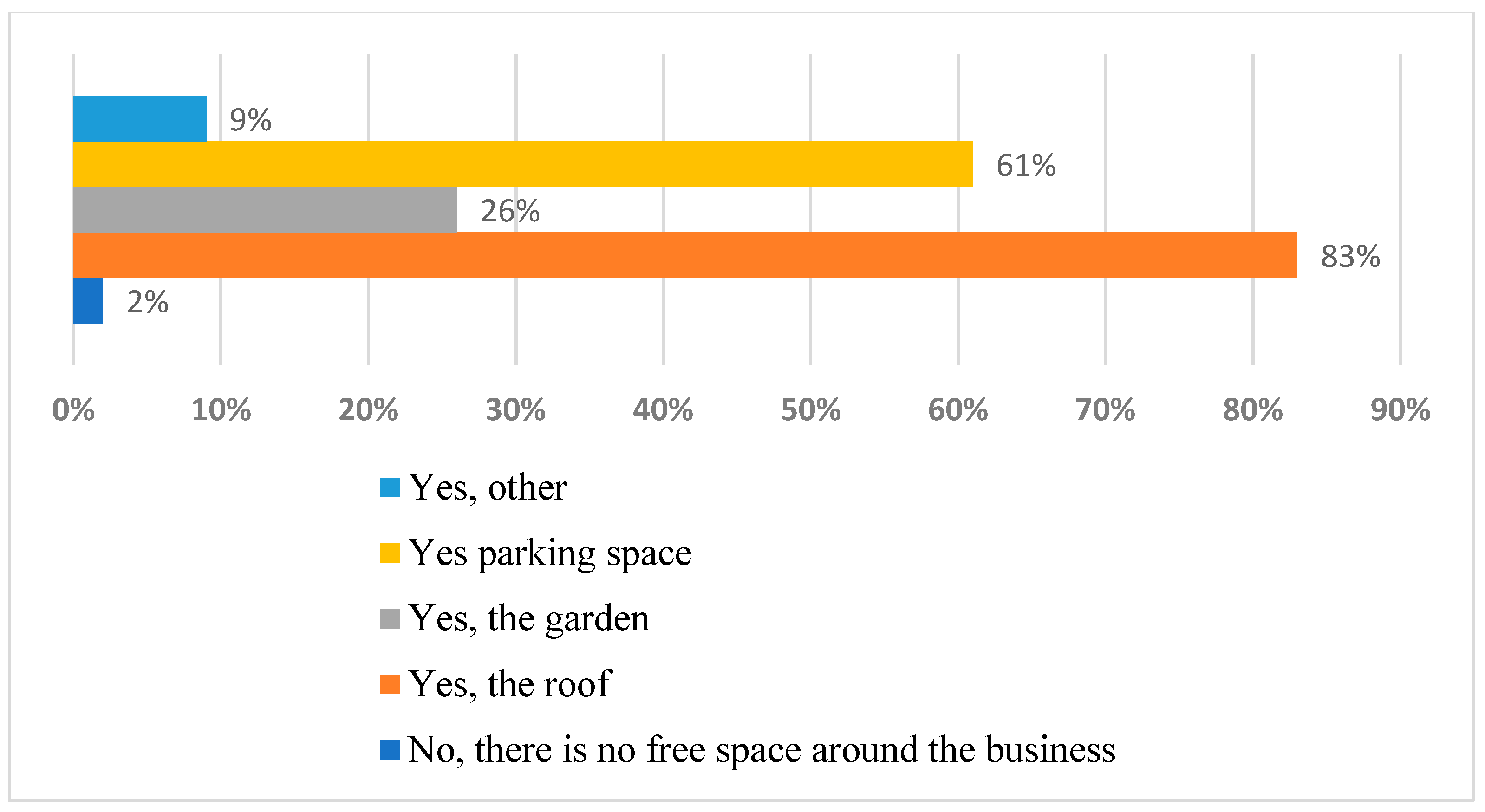

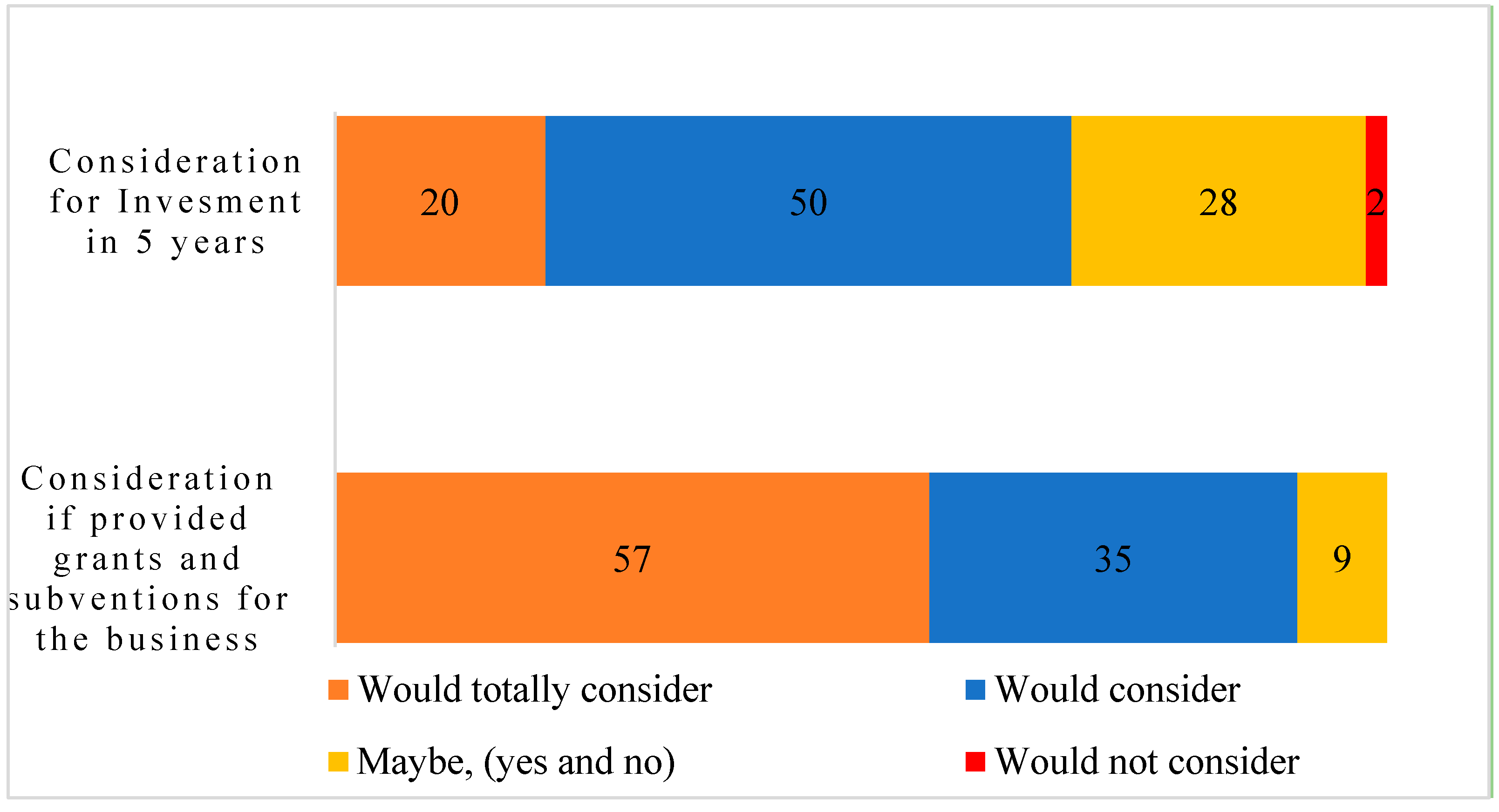

4.1. Industrial Awareness and Investment Intentions of Solar Energy in Albania

4.2. Correlation of Key Research Variables

5. Conclusions

6. Recommendations

7. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2021; IEA: Paris, France, 2021; ISBN 978-92-64-46824-6. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Alvarez–Herranz, A.; Balsalobre–Lorente, D.; Shahbaz, M.; Cantos, J.M. Energy innovation and renewable energy consumption in the correction of air pollution levels. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, R.; Ghofranfarid, M. Rural households’ renewable energy usage intention in Iran: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. Renew. Energy 2018, 122, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al–Daini, A.; Al–Samarraie, R. Industrial awareness of the role and potential of solar energy use in the UK. Renew. Energy 1994, 5, 1416–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beithou, N.; Mansour, M.A.; Abdellatif, N.; Alsaqoor, S.; Tarawneh, S.; Jaber, A.H.; Andruszkiewicz, A.; Alsqour, M.; Borowski, G.; Alahmer, A.; et al. Effect of the Residential Photovoltaic Systems Evolution on Electricity and Thermal Energy Usage in Jordan. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2023, 17, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IRENA. Renewables Readiness Assessment: Albania; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2021; ISBN 978-92-9260-338-0. [Google Scholar]

- Liobikienė, G.; Dagiliūtė, R.; Juknys, R. The determinants of renewable energy usage intentions using theory of planned behaviour approach. Renew. Energy 2021, 170, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abumunshar, M.; Aga, M.; Samour, A. Oil price, energy consumption, and CO2emissions in Turkey. New evidence from a bootstrap ARDL test. Energies 2020, 13, 5588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.; Barreto, A.C.; Souza, F.M.; Souza, A.M. Fossil fuels consumption and carbon dioxide emissions in G7 countries: Empirical evidence from ARDL bounds testing approach. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, F.A.; Aziz, M.M.A.; Saidur, R.; Abu Bakar, W.A.W.; Hainin, M.R.; Putrajaya, R.; Hassan, N.A. Pollution to solution: Capture and sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) and its utilization as a renewable energy source for a sustainable future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Abbas, Q.; Mohsin, M.; Song, G. Trilemma among energy, economic and environmental efficiency: Can dilemma of EEE address simultaneously in era of COP 21? J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 276, 111322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, I.A.; Sun, M.; Gao, C.; Omari–Sasu, A.Y.; Zhu, D.; Ampimah, B.C.; Quarcoo, A. Analysis on the nexus of economic growth, fossil fuel energy consumption, CO2 emissions and oil price in Africa based on a PMG panel ARDL approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 228, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Aslan, A. Exploring the relationship among CO2 emissions, real GDP, energy consumption and tourism in the EU and candidate countries: Evidence from panel models robust to heterogeneity and cross–sectional dependence. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 77, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsin, M.; Kamran, H.W.; Nawaz, M.A.; Hussain, M.S.; Dahri, A.S. Assessing the impact of transition from nonrenewable to renewable energy consumption on economic growth–environmental nexus from developing Asian economies. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 111999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzouk, M.A.; Fischer, L.K.; Salheen, M.A. Factors affecting the social acceptance of agricultural and solar energy systems: The case of new cities in Egypt. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2024, 15, 102741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almulhim, A.I. Understanding public awareness and attitudes toward renewable energy resources in Saudi Arabia. Renew. Energy 2022, 192, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, F.; Kosmidou, K.; Papanastasiou, D. Public awareness of renewable energy sources and Circular Economy in Greece. Renew. Energy 2023, 206, 1086–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluoch, S.; Lal, P.; Susaeta, A.; Wolde, B. Public preferences for renewable energy options: A choice experiment in Kenya. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jeong, D.; Choi, D.; Park, E. Exploring public perceptions of renewable energy: Evidence from a word network model in social network services. Energy Strat. Rev. 2020, 32, 100552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, H. Technical potential of solar energy in buildings across Norway: Capacity and demand. Sol. Energy 2024, 278, 112758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maka, A.O.; Ghalut, T.; Elsaye, E. The pathway towards decarbonisation and net–zero emissions by 2050: The role of solar energy technology. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priharti, W.; Rosmawati, A.F.K.; Wibawa, I.P.D. IoT based photovoltaic monitoring system application. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1367, 012069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IRENA. Solar Energy; International Renewable Energy Agency: Bonn, Germany, 2024; Available online: https://www.irena.org/Energy-Transition/Technology/Solar-energy (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Răboacă, M.S.; Badea, G.; Enache, A.; Filote, C.; Răsoi, G.; Rata, M.; Lavric, A.; Felseghi, R. Concentrating Solar Power Technologies. Energies 2019, 12, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timilsina, G.R.; Kurdgelashvili, L.; Narbel, P.A. Solar energy: Markets, economics and policies. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. The Energy Transition in the Western Balkans: The Status Quo, Major Challenges and How to Overcome Them (No. 76); Policy Notes and Reports; The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw): Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- IRENA. Renewable Capacity Statistics 2023; International Renewable Energy Agency: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2023; Available online: https://www.irena.org/Publications/2023/Mar/Renewable-capacity-statistics-2023 (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Rydehell, H.; Lantz, B.; Mignon, I.; Lindahl, J. The impact of solar PV subsidies on investment over time—The case of Sweden. Energy Econ. 2024, 133, 107552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishore, T.S.; Kumar, P.U.; Ippili, V. Review of global sustainable solar energy policies: Significance and impact. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Poletti, S.; Hazledine, T.; Tao, M.; Sbai, E. Deploying solar photovoltaic through subsidies: An Australian case. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 372, 123293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Burguillo, M. Assessing the impact of renewable energy deployment on local sustainability: Towards a theoretical framework. Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 2008, 12(5), 1325–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022; ISBN 978-92-64-46826–0. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Carter, C.R.; Rogers, D.S. A framework of sustainable supply chain management: Moving toward new theory. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2008, 38, 360–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Painuly, J.P. Barriers to renewable energy penetration; a framework for analysis. Renew. Energy 2001, 24, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Energy and Climate Plan (NECP); Ministry of Infrastructure and Energy of Albania: Tirana, Albania, 2024.

- Sovacool, B.K.; Griffiths, S. The cultural barriers to a low–carbon future: A review of six mobility and energy transitions across 28 countries. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luthra, S.; Kumar, S.; Garg, D.; Haleem, A. Barriers to renewable/sustainable energy technologies adoption: Indian perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 762–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lüthi, S.; Wüstenhagen, R. The price of policy risk—Empirical insights from choice experiments with European photovoltaic project developers. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, 1001–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolhosseini, S.; Heshmati, A. The main support mechanisms to finance renewable energy development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 40, 876–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.M.; Alam, K. Impact of industrialization and non–renewable energy on environmental pollution in Australia: Do renewable energy and financial development play a mitigating role? Renew. Energy 2022, 195, 203–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren21. Renewables 2023 Global Status Report a Comprehensive Annual Overview of The State of Renewable Energy; UN Environment Programme: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Collier, M.J.; Kendal, D.; Bulkeley, H.; Dumitru, A.; Walsh, C.; Noble, K.; van Wyk, E.; Ordóñez, C.; et al. Nature–Based Solutions for Urban Climate Change Adaptation: Linking Science, Policy, and Practice Communities for Evidence–Based Decision–Making. BioScience 2019, 69, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezessy, S.; Bertoldi, P. Financing Energy Efficiency: Forging The Link Between Financing and Project Implementation; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X. Financing energy efficiency Project Bundles for municipalities. In Sourcebook on Project Bundling; UNEP DTU Partnership: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020; pp. 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Rolf, W.; Menichetti, E. Strategic choices for renewable energy investment: Conceptual framework and opportunities for further research. Energy Policy 2012, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sex | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 32 | 64% |

| Female | 18 | 36% |

| Total | 50 | 100% |

| Position in the company | ||

| Owner/Co-owner | 23 | 46% |

| Executive Director | 2 | 4% |

| Director of Finance office | 9 | 18% |

| Project Manager | 6 | 12% |

| Financial services | 4 | 8% |

| Others | 6 | 12% |

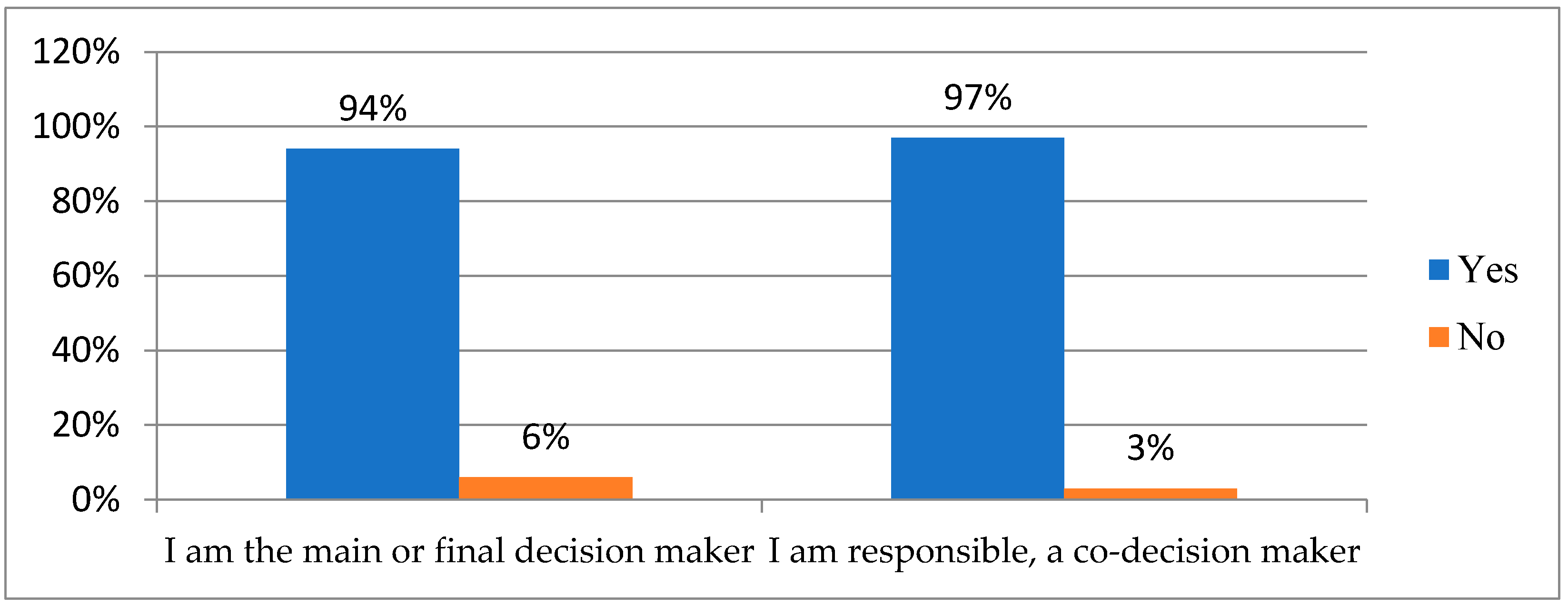

| Decision making for investment | ||

| I am the main, final decision maker | 16 | 32% |

| I am responsible, a co-decision maker | 34 | 68% |

| Size of the Company | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 8–14 million Lek annual turnover | 13 | 26% |

| Over 14 million Lek annual turnover | 37 | 74% |

| Sector the company operates | ||

| Wholesale | 21 | 42% |

| Manufacturing | 20 | 40% |

| Transport/Distribution | 5 | 10% |

| Business Services | 3 | 6% |

| Construction | 1 | 2% |

| Entertainment/Culture/Sports | 1 | 2% |

| Primary source of energy for the company | ||

| Electricity | 48 | 96% |

| Natural gas | – | – |

| Propane | 1 | 2% |

| Oil | – | – |

| Solar | 1 | 2% |

| Wind | – | – |

| Other | – | – |

| Category | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| TV Commercials | 30 | 60.0% |

| Various Programs | 15 | 30.0% |

| Online Ads | 6 | 12.0% |

| Online Information | 30 | 60.0% |

| Direct Marketing | 15 | 30.0% |

| Various Websites | 11 | 22.0% |

| Influencers | 10 | 20.0% |

| Sponsorships | 1 | 2.0% |

| Flyers/Brochures | 10 | 20.0% |

| Informative Meetings | 7 | 14.0% |

| Printed Newspapers/Magazines | 2 | 4.0% |

| Other | 2 | 4.0% |

| Reasons for Investing in Solar Panel Energy |

|

| Reasons for not considering investment in solar panel energy |

|

| Variables | Awareness | Investment Intention | Government Incentives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | 1.00 | 0.507 ** | 0.350 * |

| Investment intention | 0.507 ** | 1.00 | 0.320 * |

| Government Incentives | 0.350 * | 0.320 * | 1.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Çela, A.; Çela, S.; Manta, O. Exploring Industrial Perception and Attitudes Toward Solar Energy: The Case of Albania. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411179

Çela A, Çela S, Manta O. Exploring Industrial Perception and Attitudes Toward Solar Energy: The Case of Albania. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411179

Chicago/Turabian StyleÇela, Arjona, Sonila Çela, and Otilia Manta. 2025. "Exploring Industrial Perception and Attitudes Toward Solar Energy: The Case of Albania" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411179

APA StyleÇela, A., Çela, S., & Manta, O. (2025). Exploring Industrial Perception and Attitudes Toward Solar Energy: The Case of Albania. Sustainability, 17(24), 11179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411179