1. Introduction

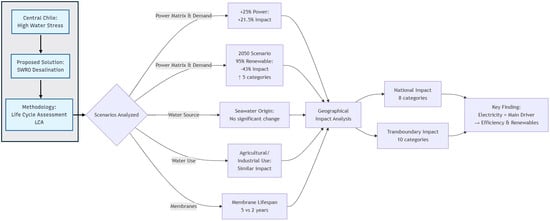

The depletion of water resources is advancing rapidly, and Chile is no exception, experiencing high water stress in its central and northern regions [

1]. Reverse osmosis (RO) desalination technologies, commonly referred to as SWRO when using seawater, are emerging as a solution due to the availability of seawater and the associated water scarcity in the northern and north-central areas of the country.

Globally, reverse osmosis (RO) is the predominant seawater desalination technology, accounting for ~65% of installed capacity, while thermal processes such as MSF and MED together represent about 28% [

2,

3]. In Chile, the dominance of RO is even more pronounced: all 22 desalination plants currently in operation with capacities greater than 20 L/s use RO technology, totaling ~8200 L/s. If the projects under construction and in the approval pipeline are completed, national capacity is expected to increase to nearly 25,000 L/s by 2028, and all of them are based on RO [

4]. The water crisis in Chile is concentrated in the northern desert but increasingly affecting the country’s central region, where most of the population and agricultural production are located. This area combines a high water demand with climate variability, leading to recurrent droughts and long-term water stress [

5,

6]. In this context, SWRO desalination emerges as an alternative, complementing limited surface and groundwater water sources. Unlike northern Chile, where desalination supplies mining operations, in central Chile this technology is promoted for domestic water use, agriculture, and multisectoral uses, thereby increasing the complexity of its environmental and social implications.

Although life cycle impacts of desalination technologies have been extensively assessed, most studies focus on environmental impacts associated with power consumption in Europe, the Middle East, and Asia [

7]. However, these studies do not adequately represent Chile’s specific energy mix, geographic conditions, or regulatory frameworks: Chile’s central region is characterized by a growing integration of non-conventional renewable energies, a strong dependence on hydropower, and the expansion of transmission systems connecting with northern mining demand. These unique features could significantly modify the environmental footprint of desalination compared to international benchmarks.

Applying a life cycle assessment (LCA) to SWRO desalination in central Chile is therefore essential, as it provides context-specific evidence, capturing the combined effect of power demand, chemical use, and membrane replacement under local operational conditions.

While several studies have evaluated desalination from a technical, environmental, and socio-political perspective in northern Chile, where desalination has historically supplied the mining sector, there is a lack of equivalent assessments for central Chile, where desalination is now expanding for domestic, agricultural, and multisectoral uses.

This study provides a decision-making tool for stakeholders to design desalination projects that are both technically viable and environmentally sustainable. By quantifying both national and transboundary impacts, LCA helps anticipate potential trade-offs, such as shifting water scarcity problems to increased greenhouse gas emissions or cross-border supply chain pressures.

To address this gap, OpenLCA and the EcoInvent database are used to conduct an LCA on the operation of SWRO plants in central Chile. The assessment inventory includes power demand, membranes (SWRO, ultrafiltration), and chemicals (pretreatment, cleaning, mineralization, and potabilization). Eight different scenarios are analyzed to identify the operational conditions under which impacts are minimized. Additionally, the impact mechanisms and their geographical origin are analyzed, indicating whether they occur within the country or beyond Chile’s borders. By locally applying this methodology, the study aims to provide decision-making environmental and geographical factors to promote sustainable desalination practices.

3. Results

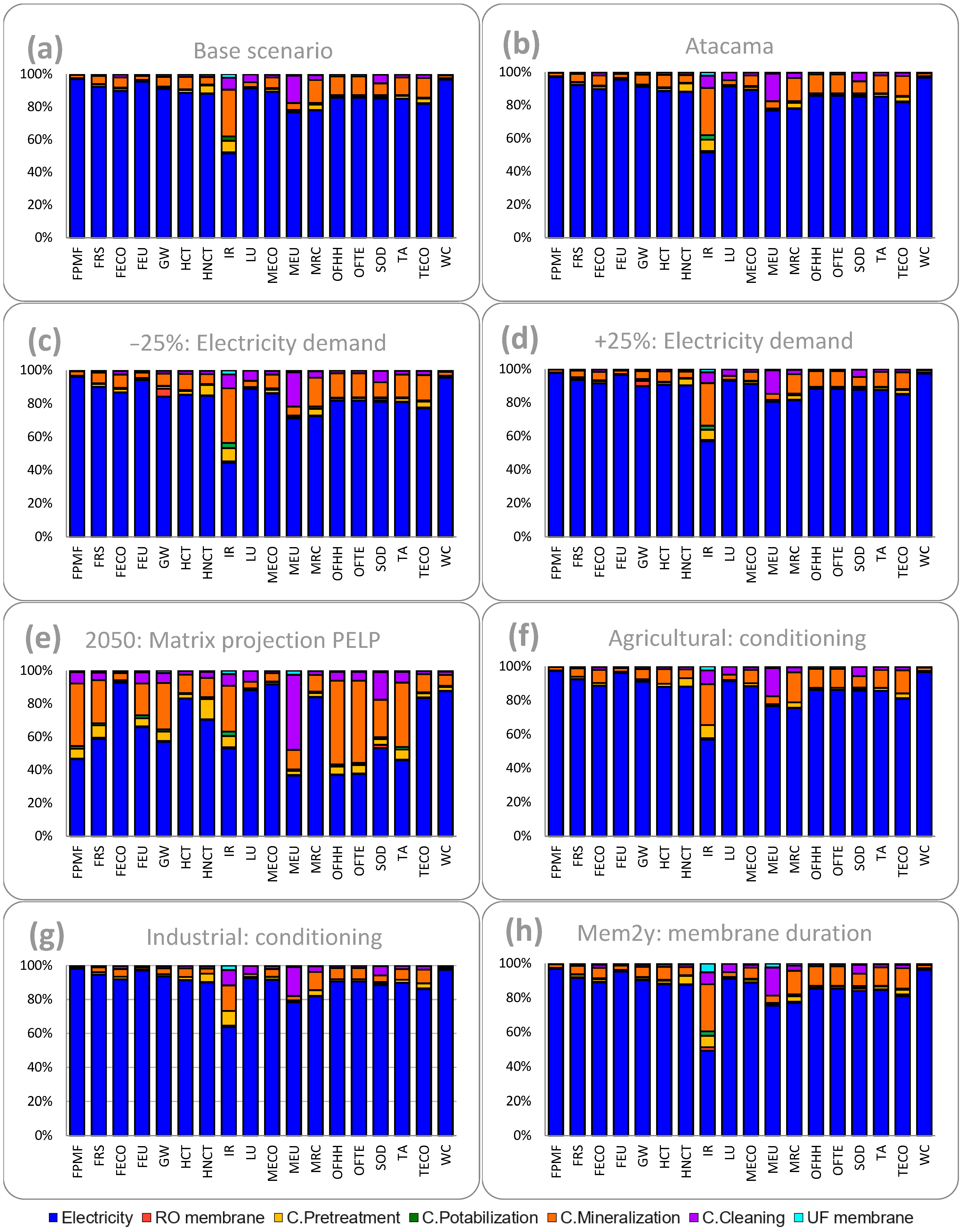

The calculated indicators and the breakdown of environmental impacts by process for each indicator are presented in

Table 8 and

Figure 1, respectively. To align with the sensitivity analysis framework of this study and to provide a clear narrative of the consequences of each operational change, the results are organized by scenario. This structure directly facilitates the subsequent discussion of how specific parameter variations influence the overall environmental profile.

Although the chemical dosages differ between the Base and Atacama scenarios (

Table 4 and

Table 5), this variation did not produce a significant change in the calculated environmental impacts, as evidenced by their identical results across all 18 indicators (

Table 8 and

Table 9).

For the +25% scenario, indicators are higher for 15 out of 18 scenarios (

Table 8) while in the 2050 scenario, most scenarios show greatest decreases compared to the Base scenario (13 out of 18). The largest percentage variations are found in power demand.

There are minimal changes in the Agricultural and Industrial scenarios when compared to the Base scenario (

Table 9).

By averaging and categorizing the inventory inputs across indicators, it is found that 86.00% corresponds to electricity, 0.59% to materials, and 13.41% to chemicals (

Figure 1a). The impact of the end-of-life (EOL) stage for both ultrafiltration (UF) and reverse osmosis (RO) membranes (landfill disposal) was found to be insignificant and does not contribute measurably to the “UF membrane” and “RO membrane” processes in

Figure 1. To compare the variation in each scenario with respect to the Base scenario, a weighted average of all indicators was used. Key aspects of the calculated indicators for each scenario are presented below.

For all the Base scenario indicators (

Figure 1a), electricity is the category with the greatest relevance in terms of impacts, reaching over 90%. The impacts associated with the electricity generation matrix primarily originate from energy generated through coal, natural gas, and, to a lesser extent, wind and photovoltaic sources. The reverse osmosis membrane model used is the SW30XLE-440i. While the EcoInvent database for this model includes emissions of 1,1,2-trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane (CFC-113), a substance harmful to the ozone layer [

20,

21], this emission was removed from our assessment. This is because the desalination plants in Central Chile are modern, and the use of CFC-113 is prohibited under the Montreal Protocol.

The 18 indicators maintain their value when compared to the Base scenario (

Table 9). It can be concluded that, for this study, changing the source of seawater from the Valparaíso region to the Atacama region does not result in significant differences in the categories of pretreatment and cleaning chemicals, which were the categories expected to be affected by changes in seawater properties.

Seventeen out of the eighteen indicators decrease, ranging from −24.2% (WC and FPMF) to −12.9% (IR,

Table 9). The average decrease is −21.5%.

Seventeen out of the eighteen indicators increase, ranging from 12.9% (IR) to 24.2% (FPMF). The average increase is 21.5%

The projection of the National Electric System to 2050 indicates a decrease in the values of 13 out of 18 indicators, with FPMF showing the largest decrease (−94.4%), and an increase in 5 out of 18 indicators, with FECO showing the largest increase at 38.2%. Given that this model alters the entire composition of the electricity generation matrix, the increases and decreases in the indicators depend on the technologies used and their corresponding participation percentages. There is a clear shift in the distribution of impacts (

Figure 1e), with a reduction in power demand compared to the Base scenario (

Figure 1a), particularly in the indicators FPMF, FRS, FEU, OFHH, and OFTE, which are the five indicators with the greatest reduction in impacts. This electricity generation matrix has high percentages of solar energy and wind energy, at 36% and 33%, respectively. Although renewable energy sources are considered to have fewer impacts, in this case, the impacts are greater for the indicators FECO, IR, MECO, MRC, and TECO. This is due to the materials used in the construction of solar panels and wind turbines, particularly concerning the end-of-life management of these materials. Despite the increases and decreases, this scenario is characterized by reductions in magnitude.

In this scenario, the indicators FECO, HCT, HNCT, MECO, MRC, and TECO increase, while FPMF, FRS, FEU, GW, IR, OFHH, OFTE, and TA decrease, ranging from a reduction of −9.4% to an increase of 3.1% for IR and MRC, respectively. This increase is attributed to the fact that mineralization for this conditioning requires a higher dosage of calcium carbonate, which affects the MRC indicator. It can be observed that the variation in the composition of impacts across the 18 indicators is slight, as mentioned at the beginning of

Section 3 (

Figure 1f). The average variation is −0.4%.

For this condition, all indicators decrease between −0.9% and −19.1%, with WC and IR being the respective extremes. It is noteworthy that the changes in conditioning are primarily the result of alterations in the chemicals used for mineralization. As mentioned in

Section 3, the variations in conditioning scenarios are slight (

Figure 1g). The average variation is −4.0%.

In this final scenario, the membrane lifespan is reduced from 5 years to 2 years, thereby increasing the replacement rate. As expected, all indicators either increase or remain unchanged, with values ranging from 0.0% to 4.5% with FMPF and IR being the respective extremes (

Table 9). The average variation is 0.9%.

4. Discussion

The sensitivity analysis performed confirms that power demand is the most influential factor on environmental impacts (

Figure 2), as previously shown [

13,

22]. Methods to mitigate such impacts [

23], such as energy recovery systems, can achieve values of 2–3 kWh/m

3 [

24]. To illustrate their effects on environmental impacts, a 25% reduction in power consumption (3.5 kWh/m

3) led to an average decrease in indicators of −21.5%. The indicators FPMF, WC, and FEU experienced a reduction of over −23% (

Table 9). This highlights the importance of enhancing the efficiency of SWRO plants and integrating energy recovery systems into existing or future installations.

A substantial reduction in 13 out of 18 indicators was observed under the projected 2050 electricity generation matrix, foreseeing a dominant contribution from renewable sources (36% solar and 33% wind,

Figure 1e). Yet, contrary to the expectation of uniformly lower impacts, five indicators (FECO, IR, MECO, MRC, and TECO) exhibit increases. These results highlight an important trade-off; while the substitution of fossil fuels reduces greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution, large-scale renewable infrastructures introduce pressures associated with the extraction and processing of minerals as well as with the management of end-of-life components (e.g., photovoltaic panels and wind turbine blades). This outcome is particularly relevant in the Chilean context where decarbonization strategies are strongly based on solar and wind but where recycling systems and circular economy policies for renewable technologies remain incipient. The evidence presented here underscores that the benefits of a cleaner energy mix cannot be considered in isolation from the upstream and downstream impacts of renewable technologies. Since the impacts of power consumption are high compared to the contribution of chemicals and materials, the composition of the generation matrix is a key factor. This also means that studies in this area are often closely tied to a specific region or country [

11,

22]

If the energy source is high in coal (Base scenario), higher values of the FPMF indicator due to the particulate matter generated by thermal power plants are expected. Conversely, as observed in the 2050 scenario, high percentages of solar and wind energy increase some indicators (FECO, MECO, MRC, IR, and TECO). Variable geographic and climate conditions across the country imply that the available non-conventional renewable energies (NCRE) are consequently not uniform. This becomes significant when SWRO projects aim to self-supply their power, as the impacts depend on the site-specific power source. Given the plans to increase non-conventional renewable energy sources in Chile -by 2024, 41% came from these sources [

25] the energy matrix is becoming cleaner year by year. This suggests that indicators such as GW, FPMF, FEU, and FRS will decrease, as observed in the 2050 scenario. Based on the research findings, a strategy for reducing environmental impacts is to opt for mixed or transitional energy matrices over those solely dependent on fossil fuels, and to minimize consumption during operation through strategies such as energy recovery.

The energy demand of reverse osmosis desalination is strongly determined by the TDS content of feedwater, making pretreatment a critical factor for both efficiency and sustainability [

26,

27]. Effective pretreatment reduces fouling and scaling, lowering pressure requirements, energy consumption, and chemical use, while extending membrane lifespan. In contexts such as Chile, where seawater composition varies regionally, this step becomes essential to meet water quality standards and minimize life cycle impacts dominated by electricity use. Although advanced pretreatment technologies can improve performance, they also involve trade-offs in cost and embodied energy, underscoring the need for case-specific assessments. By reducing Base energy demand, optimized pretreatment not only enhances operational performance but also facilitates the integration of desalination with renewable energy sources.

The production and use of chemicals at each stage (pretreatment, cleaning, mineralization, and potabilization) represent the second most significant impact factor, particularly the chemicals used in mineralization. This underscores the importance of accurately dosing the chemicals used. Overuse of chemicals not only has economic consequences but also environmental ones. The indicators with the highest percentages related to chemical use in the Base scenario (

Figure 1a) are IR, MRC, MEU, TA, and TECO. When evaluating the Base and Atacama scenarios, no significant differences in impacts are evident. For the Agricultural and Industrial conditioning scenarios, there are no significant changes compared to the Base scenario. For the Industrial scenario, the average reduction is −4.0%, while for the Agricultural scenario, the average reduction is −0.4%. These differences from the Base scenario are related to the conditioning applied to the water based on its intended use. A relationship has been found between mineral water consumption and serum levels [

28]. Additionally, it has been shown that drinking water can significantly contribute to the daily intake of essential minerals, such as Ca, Mg, and Zn [

29].

In the Agricultural scenario, some indicators increase while others decrease. This is attributed to an increase in calcium carbonate and a decrease in magnesium sulfate compared to the Base scenario, driven by the specific requirements for this application [

8]. For both scenarios (agricultural and industrial), the IR indicator exhibits the greatest variation, decreasing by −9.4% for agricultural conditioning and −19.1% for the industrial scenario. This is because the IR indicator has a higher percentage contribution from mineralization chemicals (

Figure 1a,g,h), and thus, changes in these chemicals are reflected in the indicator’s value. It is important to note that Chilean regulations do not specify a minimum hardness value, although there is a maximum magnesium concentration limit of 125.0 mg/L [

18].

Regarding the membranes used, when compared to electricity and chemicals, they exhibit lower environmental impacts. The membrane used in this study is the model SW30XLE-440i SWRO membrane. According to the EcoInvent database it has CFC113 emissions, which is harmful to the ozone layer, but they were not considered because the Montreal protocol mandates the phase-out of ozone depleting substances. Concerning the membrane replacement scenario, mem2y, two scenarios are evaluated: a 20% annual replacement (total replacement every 5 years) and a 50% annual replacement (total replacement every 2 years). Although less dominant than electricity-related burdens, these increases highlight the cumulative significance of material flows when membrane lifespans are shortened. Consequently, strategies aimed at extending service life through improved pretreatment, as well as initiatives for reuse, refurbishment, or recycling of spent UF and RO membranes, emerge as critical levers for impact reduction. It is important to note that while this study models landfill disposal, evaluating other end-of-life alternatives is critical for a complete understanding within the LCA framework. Beyond their technical benefits, such approaches align with circular economy principles, enhancing resource efficiency and mitigating supply chain dependencies linked to polymeric materials. The Integration of membrane end-of-life management into LCA frameworks was essential, not only to capture the full spectrum of impacts but also to guide innovation toward low-impact alternatives that complement energy efficiency efforts in desalination systems.

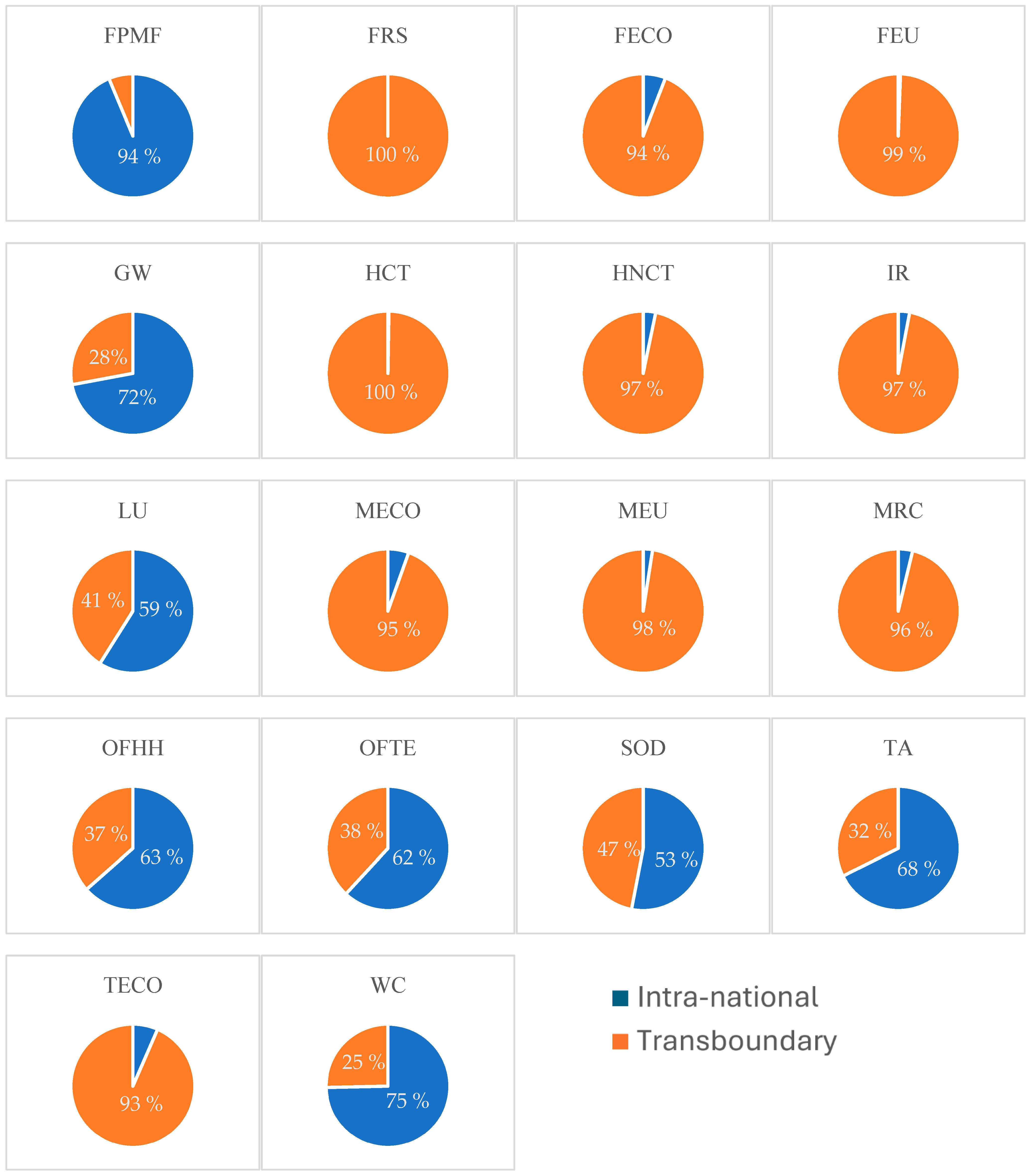

The geographical classification of impacts as national or transboundary was methodologically established by tracing the origin of key inputs within the life cycle inventory. The fossil fuels (e.g., coal, natural gas) used for power generation in the SEN are imported, with only their conversion into electricity occurring within Chile. Similarly, the technologies for NCRE generation and the reverse osmosis and ultrafiltration membranes are entirely imported, while the chemicals are predominantly sourced from international markets. By accounting for these import dependencies and utilizing the location-specific data available in the OpenLCA and Ecoinvent framework, we were able to systematically attribute the environmental impacts to either national or transboundary categories. This geographical differentiation made it possible to observe that for eight indicators (FPMF, GW, OFHH, OFTE, TA, SOD, LU and WC), the environmental impacts are generated within the national territory (

Figure 2), while the rest are generated beyond the borders. Regarding the primary mechanisms (major contribution to environmental impacts), for the indicators FPMF, GW, OFHH, OFTE, SOD and TA, the predominant mechanism is power generation through coal, which directly arises from production. FPMF and GW are two of the most recognized indicators by Chilean consumers and are also more regulated [

30]. The LU indicator is attributed to land use for obtaining raw materials used as biomass. This impact can decrease depending on the assumptions made, as biomass generation often utilizes by-products. The WC indicator is linked to electricity generation in reservoir-based hydroelectric plants, particularly due to water loss caused by evaporation. For the indicators FRS, FECO, FEU, HNCT, MECO, MEU, and MRC, the impact mechanisms are found in the stages of extraction, preparation, and waste from coal mining, primarily mining waste. For HCT, these relate to materials used in the construction of natural gas plants; for IR, they correspond to the production of inputs for magnesium sulfate. For TECO, the primary mechanism is coke, which is produced during the manufacture of construction materials for plants, primarily those fueled by natural gas. Indicators and the locations of their impacts are not well known, with greater emphasis placed on global warming indicators [

31].

Although this study focuses on the environmental performance of SWRO systems, it is important to recognize that the long-term feasibility of desalination in Chile is not determined solely by technical or environmental indicators. Social acceptance and regulatory conditions have increasingly shaped project development, particularly in regions where desalinated water is intended for public supply or agriculture. In Chile, several desalination initiatives have encountered community resistance linked to marine ecosystem impacts, privatization of water access, brine discharge, and concerns that desalination may reinforce an extractive development model rather than promote integrated water governance. Recent case studies in northern Chile highlight that even technically efficient desalination plants may face delays or legal disputes if they fail to engage local stakeholders or align with evolving regulatory frameworks on coastal concessions, water rights, and environmental licensing [

32,

33,

34]. Therefore, future LCAs should incorporate not only environmental metrics but also socio-institutional factors, as the success of desalination increasingly depends on its legitimacy within territorial and policy contexts.

Based on the scenario analysis, several operational strategies emerge as relevant for reducing the environmental footprint of SWRO in Chile. Since energy consumption accounts for more than 75% of the impacts in most categories, priority should be given to high-efficiency pumping systems, energy recovery devices and optimized pressure management. The strong reductions observed under the 2050 renewable-energy scenario also indicate that hybrid configurations that combine grid electricity with on-site photovoltaic or wind generation can significantly lower impacts. Optimizing pretreatment and cleaning regimes can reduce both chemical demand and membrane replacement frequency, which aligns with current circular-economy initiatives in the sector. In addition, the results highlight the importance of economies of scale, since larger plants achieve lower specific energy use (kWh m3) and reduced material intensity per unit of water produced. Multipurpose desalination plants, capable of supplying industrial, agricultural and municipal users simultaneously, also improve resource efficiency by stabilizing demand profiles and increasing infrastructure utilization. Finally, extending membrane lifespan or enabling reuse pathways is relevant, given that accelerated replacement significantly increases environmental burdens. Overall, the findings show that environmental performance depends not only on technological choice but also on operational strategies involving energy integration, plant scale, end-use configuration and material circularity.

It is essential to note that having a life cycle assessment inventory with local and up-to-date data is crucial, not only for accurately identifying where each impact is generated, but also for more accurately representing environmental impacts within a national context. It was noted that the process of generating energy with coal has negative ecological impacts both domestically and internationally, and at various stages (extractive and productive). This may change as Chile undergoes an energy transition process, where national plans aim to retire and convert coal plants [

35], in addition to increasing the percentage of renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar (see 2050 scenario,

Figure 1e).

Limitations of This Work

While this study provides a valuable assessment of the environmental impacts of desalination in central Chile, it is important to acknowledge its limitations for the correct interpretation of the results and to guide future research.

Choice of membrane model. The membrane used in both the WAVE modeling and the LCA corresponds to the SW30XLE-440i model, available in the EcoInvent database. While this is a representative model, the reverse osmosis membrane industry constantly evolves towards products with higher energy efficiency and flow. Therefore, the impacts associated with the membrane could vary with other models, and the results may not fully reflect future market practices.

Geographical specificity of coal impacts. The life cycle impacts of coal-fired power generation, a main contributor in many indicators, are derived from generic inventory data from EcoInvent. These may not fully capture the particularities of the Chilean supply chain and its fluctuations (since the origin of the coal varies frequently) or the impacts of coal mining in the regions of origin. This limitation affects the accuracy of the geographical traceability of transboundary impacts, although it does not invalidate the overall classification of impacts by their origin (national or transboundary).

Exclusion of local operational impacts from brine discharge. The local impacts of brine discharge, such as the formation of saline plumes and the effects of chemical additives (antiscalants, antioxidants) on coastal ecosystems, are not captured by this assessment. These impacts are site-specific and species-specific and are currently subject to study and discussion in Chile.

Uncertainty associated with cleaning and chemical dosages. The quantities of chemicals used in pretreatment, membrane cleaning, and water conditioning can vary significantly in real operation due to the specific operational strategies of each plant. This variability introduces a degree of uncertainty in the environmental contribution attributed to chemicals.

Recovery rate assumption. A fixed recovery rate of 45% was assumed, a standard value, but one that can vary across different facilities. For example, smaller plants may operate with lower rates and therefore present higher environmental impacts.

5. Conclusions

The ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint (H) modeling allowed for the geographical classification of impacts, identifying eight as national and ten as transboundary. The mechanisms with the greatest contribution in both categories originate from coal (i.e., energy production, extractive, or manufacturing processes), highlighting the importance of reducing the percentage of fossil energy sources and increasing that of renewable energies.

Results indicate that power generation for operating SWRO plants contributes to all impact categories evaluated for all scenarios, except for the 2050 scenario, aligning with previous studies [

7,

13,

24].

For scenarios where there was variation in power demand or the matrix (Atacama, Agricultural, Industrial, Mem 2y), there are minimal differences in the results (

Figure 1b,f–h). The Mem 2y scenario shows an increase in all indicators. It is thus recommended to have plans for reusing or refurbishing membranes, given their replacement rate, to extend their useful life.

For the conditioning Agricultural and Industrial scenarios, indicators decreased compared to the Base scenario primarily due to the removal of magnesium sulfate from the mineralization chemicals.

Significant differences are found when changes are made to the generation matrix and to the demand value. By reducing or increasing the power demand by 25%, there is an average impact reduction of −21.5% or an increase of 21.5%, respectively, making the variable the most sensitive in the study. Taking the GW indicator from the Base scenario as an example (

Figure 1a), when power demand is increased by 25%, impacts rise by 22.7% (

Figure 1d). This demonstrates the relevance of power demand in the GW indicator. Reducing the amount of chemicals used by 25% or decreasing the membrane replacement rate by 25% results in minor reductions in impacts. When comparing scenarios, the greatest reduction occurs in the 2050 generation matrix projection (

Figure 1e), which is highly based on renewable energy sources (36% solar and 33% wind). However, five indicators have increased (FECO, IR, MECO, MRC, and TECO) due to the end-of-life of photovoltaic panels and wind turbines, exemplifying the usefulness of this methodology in conducting a traceability exercise of these impacts. The average variation for this scenario is 36.94% (

Table 2). This highlights the advantage of having a matrix inclined towards non-conventional renewable energies, aligning with Chile’s strategic plans [

25].

The operational power demand is a primary source of environmental impacts, and therefore, it is crucial to plan strategies (i.e., recovery technologies and renewable energy generation wind or solar alternatives) that are essential for their mitigation. Future studies should integrate economic indicators such as Levelized Cost of Water (LCOW) and cost–benefit analysis to provide a more comprehensive assessment of mitigation strategy viability.