The Network–Place Effect of Urban Greenways on Residents’ Pro-Nature Behaviors: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Study Distribution and Quality Assessment

3.1.1. Distribution of Study

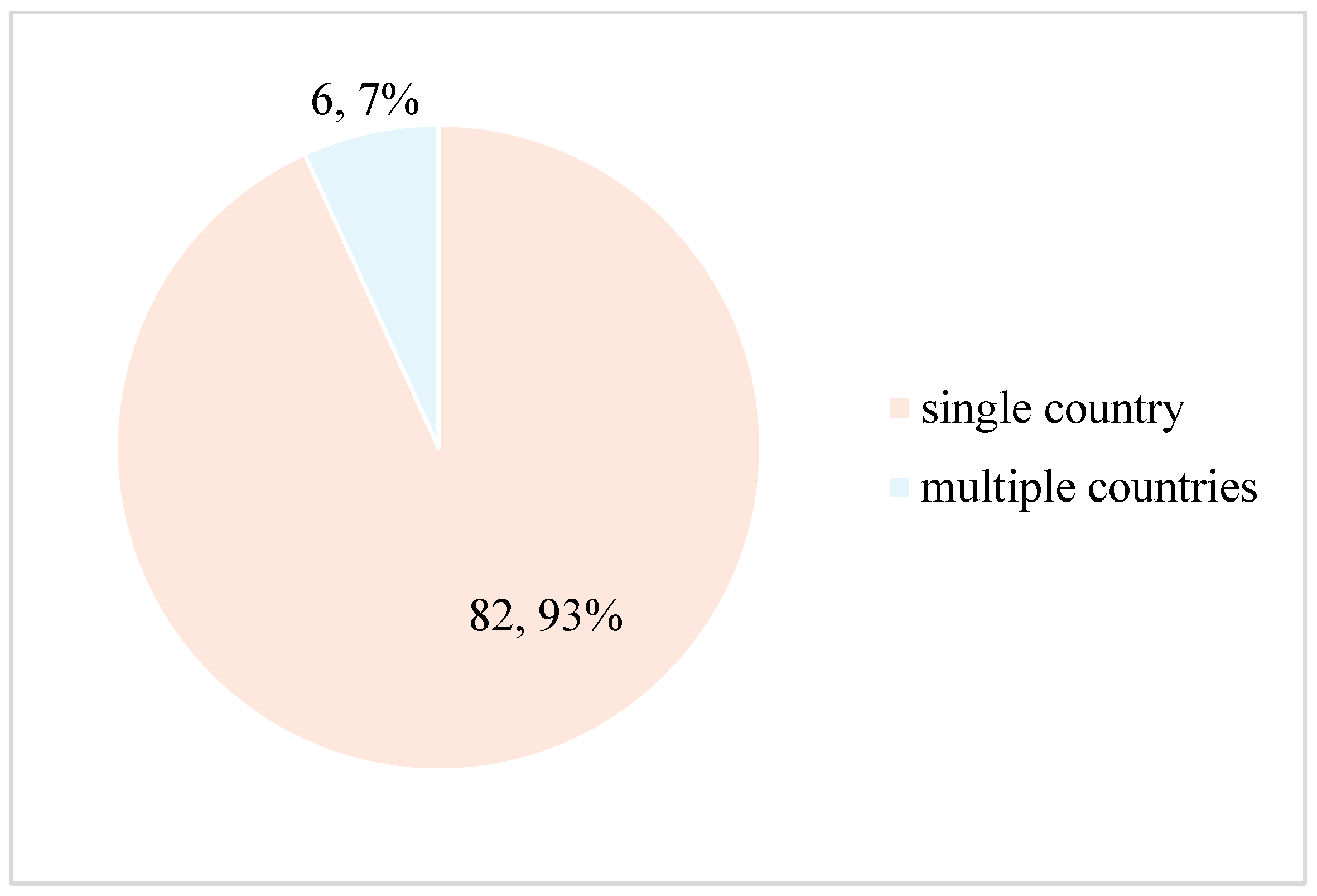

3.1.2. Quality Assessment

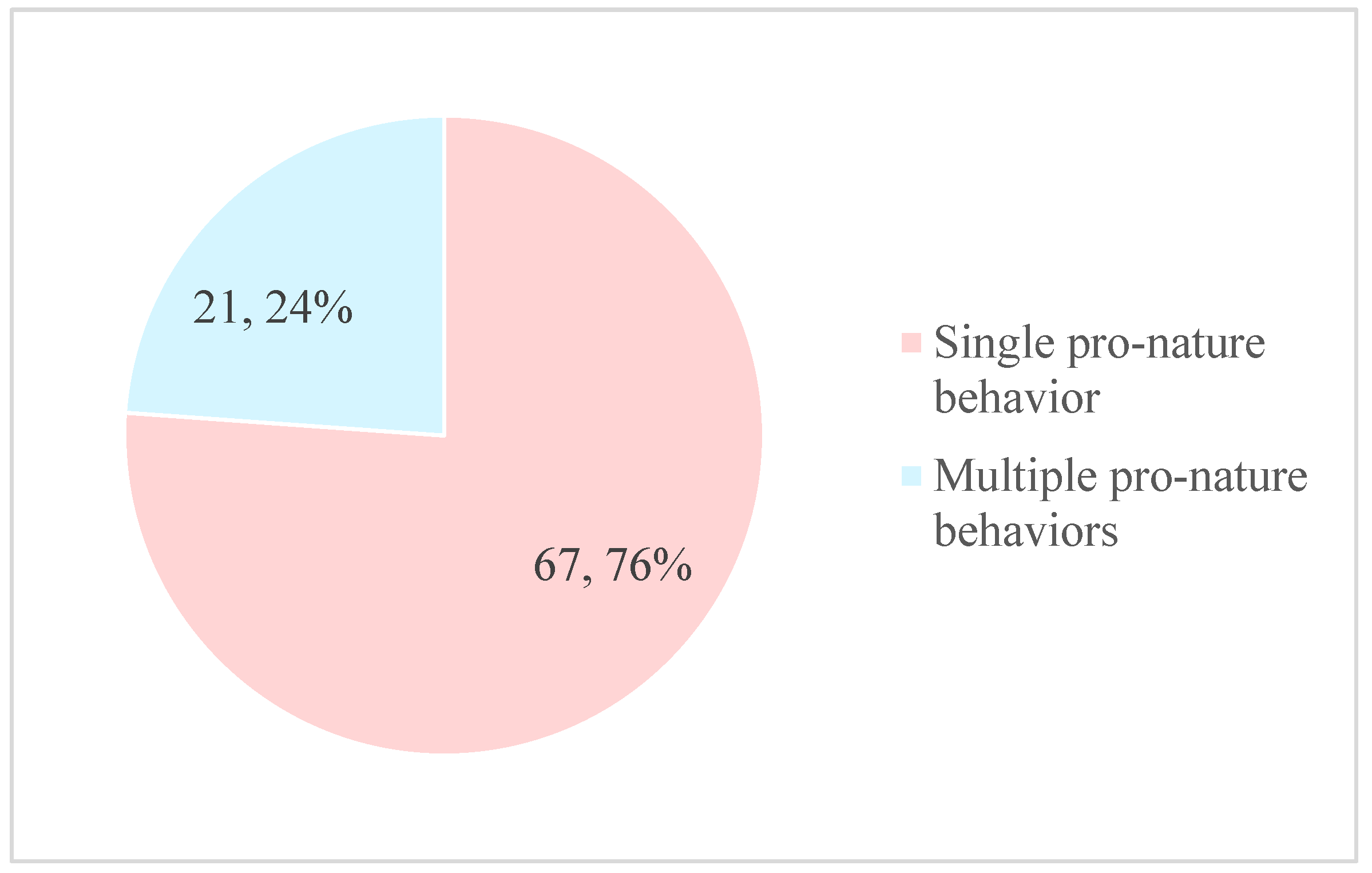

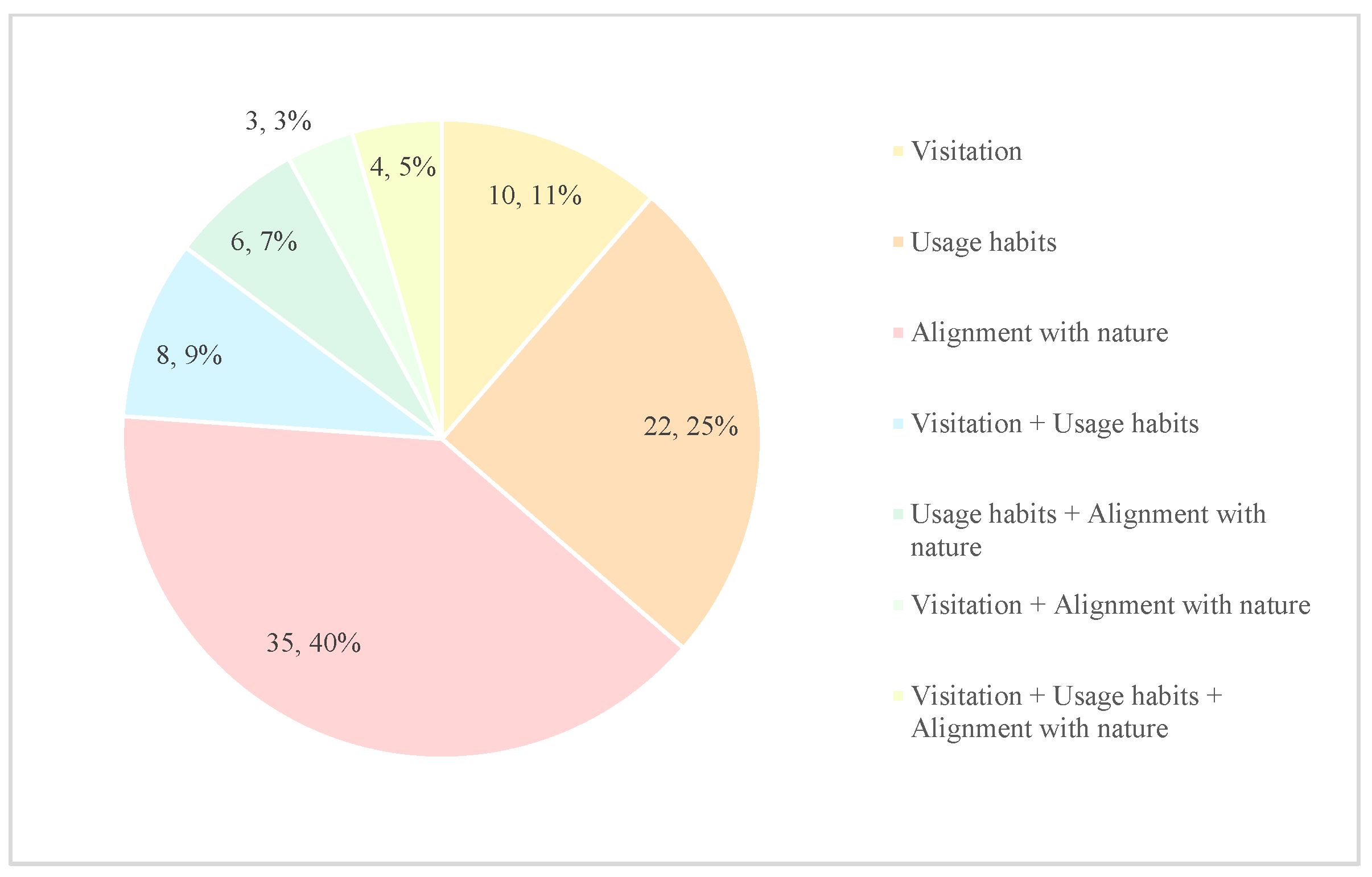

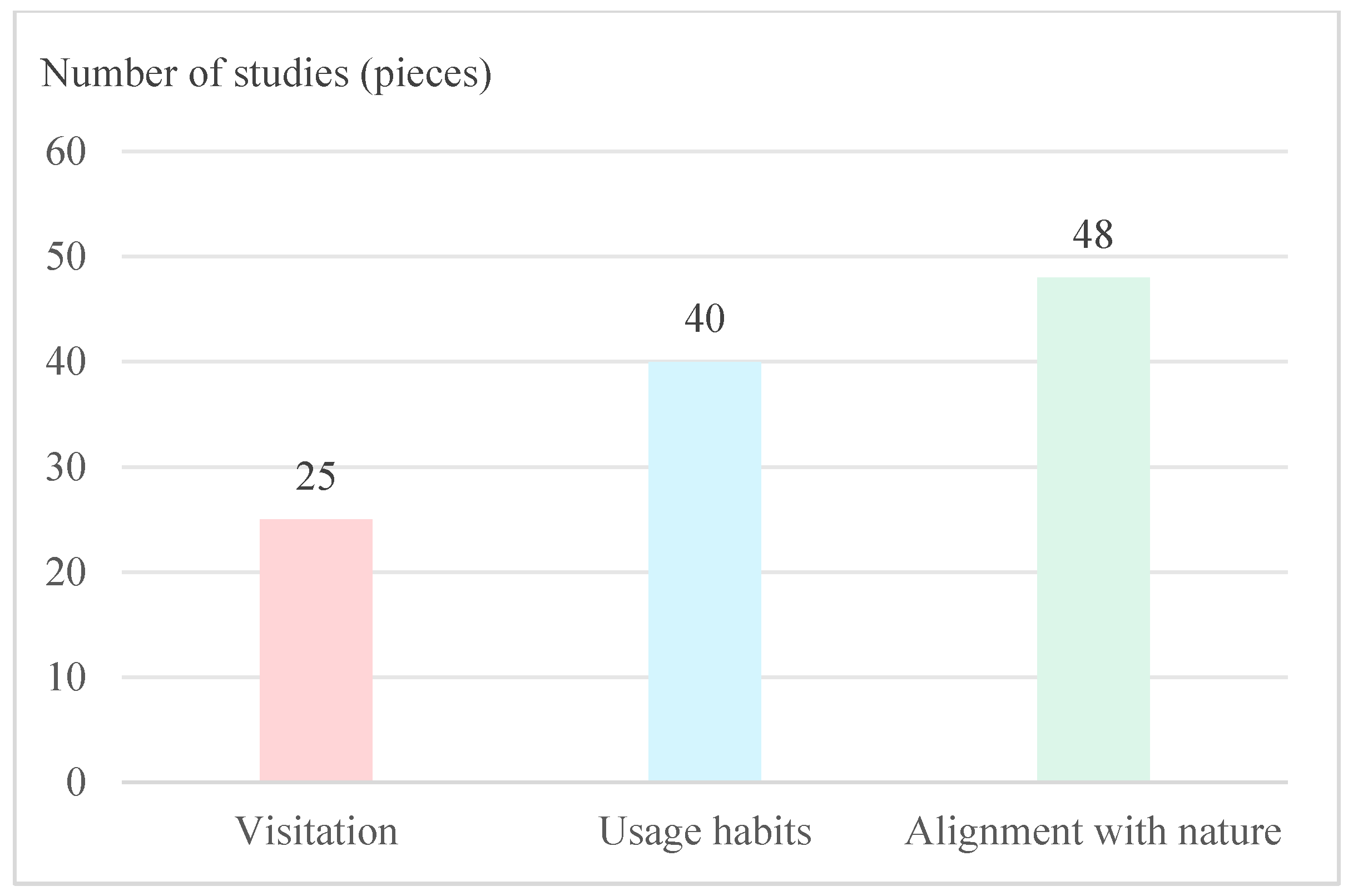

3.2. Characteristics of Greenway-Related Pro-Nature Behaviors

3.3. Associations Between Pro-Nature Behaviors and Greenway Environments

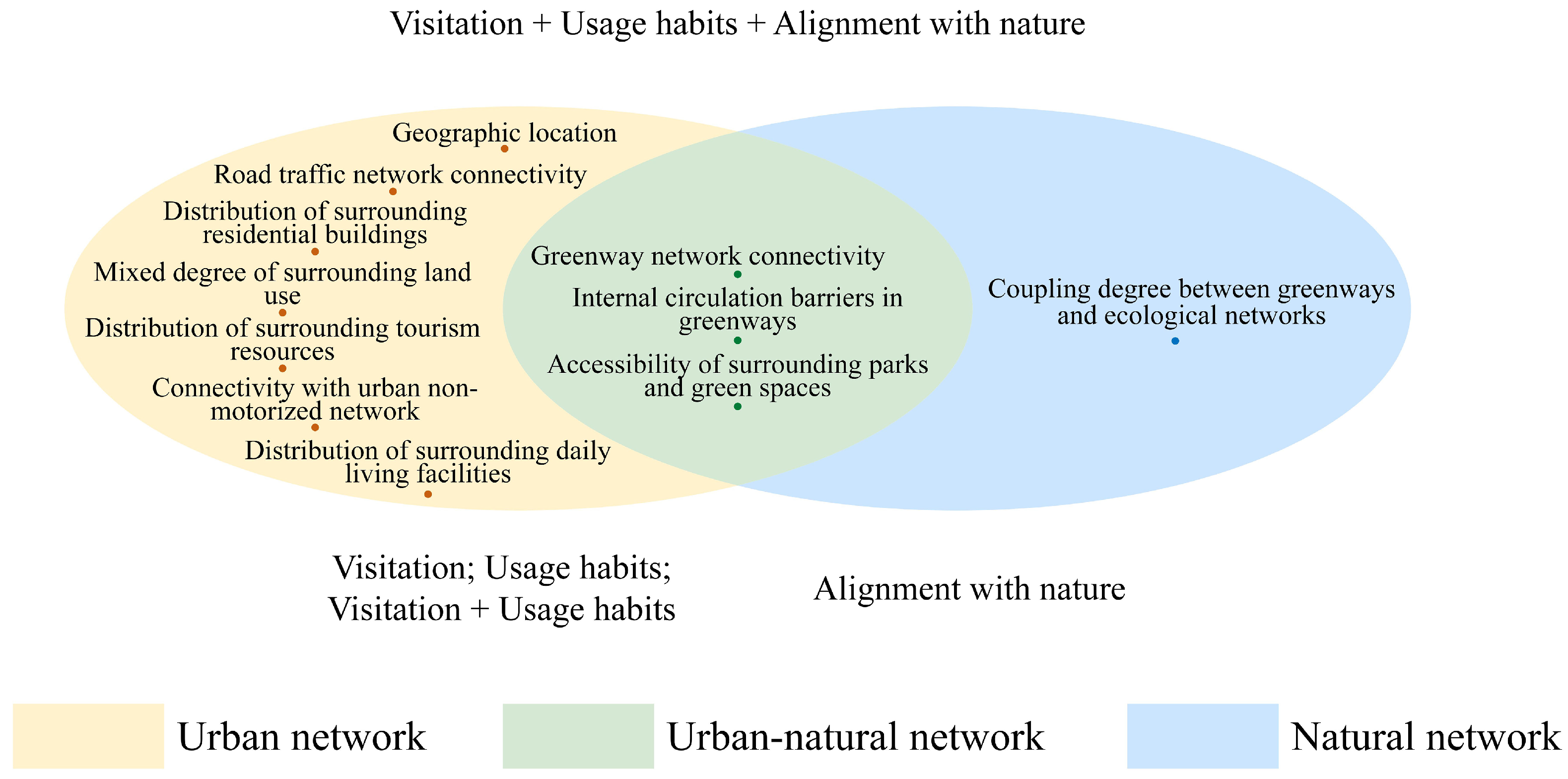

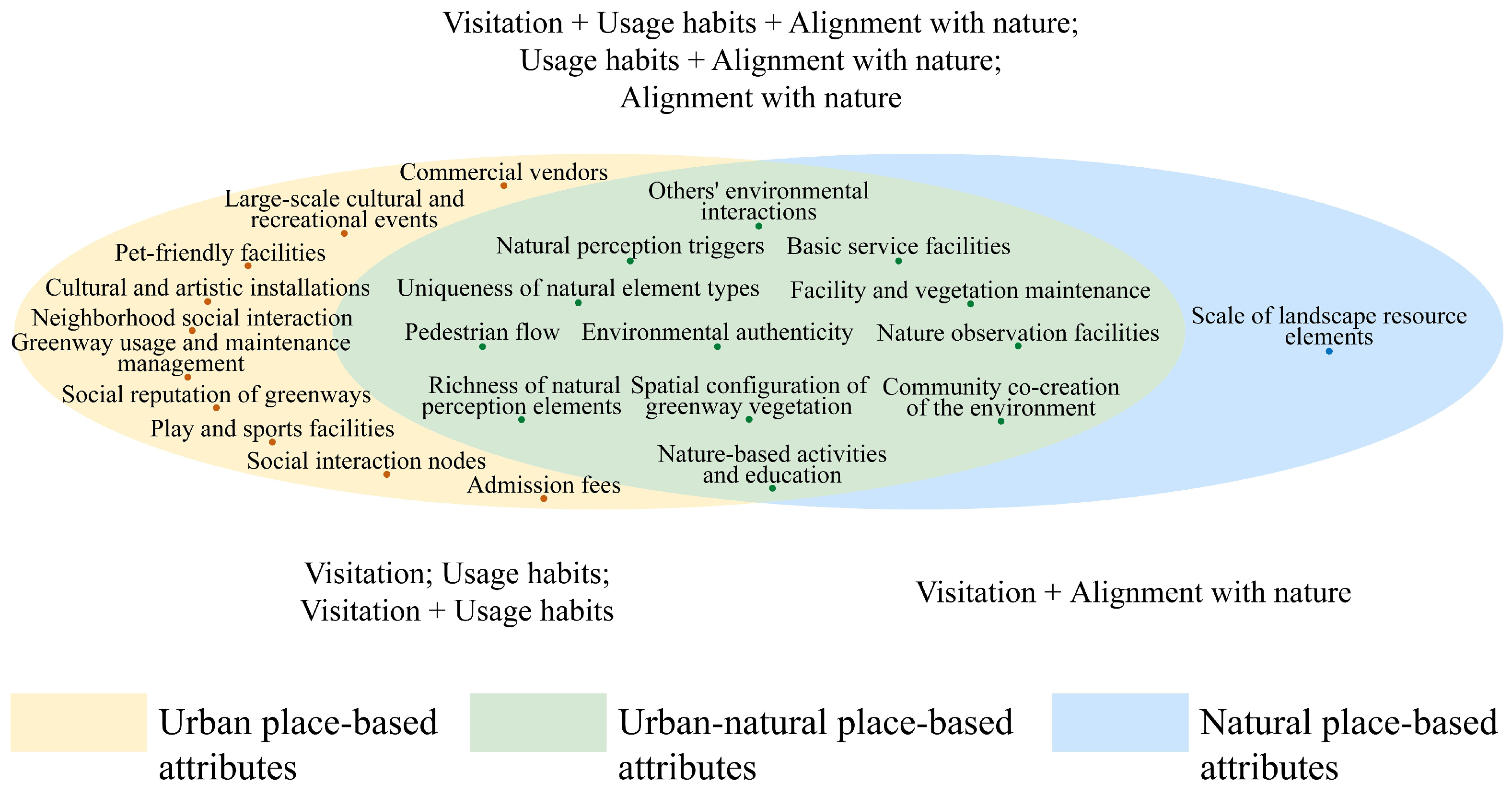

3.3.1. Associations Between Visitation and Greenway Environments

3.3.2. Associations Between Usage Habits and Greenway Environments

| Greenway Attributes | Associated Elements | Built Environment Characteristics | Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network attributes | The internal network structure of greenways themselves | Greenway network internal connectivity | Greenway node density; Greenway continuity. | [19,70,79,88,90] |

| Greenway internal movement barriers | Path length; Slope. | [70,76] | ||

| Connectivity between greenways and road networks | Greenways located in urban areas | Greenways located in urban areas. | [19,33] | |

| Greenway road network connectivity | Intersection count; Motor vehicle parking facilities; Physical barriers; Accessibility to transit; Distance to urban arterial roads. | [12,19,21,24,33,36,51,52,65,69,70,72,77,80,87,88,91,92] | ||

| Connectivity between greenways and pedestrian/cycling networks | Connectivity between greenways and slow-traffic networks | Number of access points; Bicycle lane connections; Pedestrian-friendly surroundings; 15 min slow-traffic coverage; Greenway connection-node ratio; Proportion of direct walking paths between greenways and residential areas; Walkability indices. | [24,43,52,73,77,88] | |

| Linkages between greenways and urban facilities | Distribution of residential buildings around greenways | Residential connectivity; Residential proximity; Residential area density; Community openness; Greenway coverage length near residential areas. | [12,16,18,19,21,23,24,33,36,52,65,68,70,73,74,76,77,86,87,93,94] | |

| Surrounding land-use diversity | Land-use mix degree. | [24,43] | ||

| Accessibility to nearby parks and green spaces | Accessibility to nearby parks and green spaces. | [92,93] | ||

| Distribution of daily life facilities around greenways | Connectivity to daily activity destinations; Building density. | [12,21,23,43,80,88] | ||

| Place-based attributes | Landscape resources | Uniqueness of landscape elements | Water bodies; Dense vegetation. | [16,19,86,87,97] |

| Greenway social reputation | Greenway recognition; Social media recommendations. | [12,18,36,73,95] | ||

| Natural perception elements | Natural perceptual trigger elements | Wildlife; Seasonal natural landscapes; Dynamic scenery; Water bodies and riparian scenery; Wetlands; Woodlands; Aromatic plants; Fruit trees; Wooden boardwalks; Bird sounds. | [12,19,23,42,52,66,69,73,86,87,88,91,96,97] | |

| Richness of natural perceptual elements | Richness of natural landscapes; Topographic variation; Species diversity; Chromatic diversity; Vegetation diversity. | [12,36,51,52,72,74,90,96,97,99,100] | ||

| Greenway vegetation spatial patterns | Green visibility index; Enclosure; Openness; Canopy closure; Curvilinear forms; Natural visibility; Vegetation coverage; Tree density. | [42,43,51,87,90,92,94,96,99] | ||

| Supporting facilities | Basic service facilities | Trails; Benches; Water stations; Restrooms; Trash bins; Lighting facilities; Surveillance; Signage clarity; Guardrails; Emergency equipment; Management office; Pergolas; Barrier-free facilities. | [12,13,14,19,21,23,24,36,42,43,51,52,65,70,72,73,74,76,77,79,80,86,87,88,90,91,93,96,99,100] | |

| Recreational and sports facilities | Fitness equipment; Sports fields; Children’s playgrounds. | [13,14,21,24,33,51,77,79,86,87,93,96,101] | ||

| Pet amenities | Pet-friendly paths; Pet activity areas. | [14,24,86] | ||

| Social nodes | Rest and social nodes; Barbecue areas; Table and seating. | [12,14,19,21,24,72,77,86,100] | ||

| Natural observation facilities | Environmental education signage. | [12,72,77,86] | ||

| Cultural and Art Installations | Cultural and art installations. | [13,73,74,85,90] | ||

| Residents’ activities within greenways | Neighborhood interactions | Neighborhood-friendly interactions; Community event organization. | [12,42,73,74,88] | |

| Community environmental co-creation | Community environmental co-creation; Spontaneous planting behaviors. | [21,23,53,73,74,88] | ||

| Pedestrian flow | Crowd density. | [19,36,72,90,91,101] | ||

| Others’ environmental behaviors | Disorderly behaviors; Usage conflicts between different users; Environmental vandalism; Motor vehicle interference. | [19,23,42,51,65,72,76,77,90,97,99] | ||

| Operational maintenance | Facility maintenance and vegetation care | Vegetation pruning and care; Facility repair; Water treatment; Facility cleanliness. | [14,19,23,36,42,51,52,69,73,76,77,79,80,86,91,93,97,99,100,102] | |

| Entrance fees | Entrance fees. | [74] | ||

| Greenway usage security and management | Mosquito control; Security patrols; Slow-traffic Policy support; Behavioral management. | [23,52,72,76,80,87,88] |

3.3.3. Associations Between Alignment with Nature and Greenway Environments

| Greenway Attributes | Associated Elements | Built Environment Characteristics | Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network attributes | The internal network structure of greenways themselves | Greenway network internal connectivity | Greenway continuity. | [53,107] |

| Greenway internal movement barriers | Terrain complexity; Path length. | [66,103] | ||

| Linkages between greenways and urban facilities | Accessibility to nearby parks and green spaces | Accessibility of park green spaces. | [15,36,67] | |

| Linkages between greenways and ecological networks | Connectivity between greenways and ecological networks | Centrality within ecological networks; Coupling with ecological corridors; Proximity to linear corridors; Connectivity with various natural patches. | [13,32,55,88,104,111] | |

| Place-based attributes | Landscape resources | Uniqueness of landscape elements | Types of unique landscape elements. | [22,34,54,104,105,109,110] |

| Scale of landscape elements | Scale of natural resource elements underlying greenways. | [13,55,88] | ||

| Natural perception elements | Natural perceptual trigger elements | Wildlife; Water bodies; Flowering plants; Vegetation; Majestic ancient trees; Distinctive landforms; Fruits; Unanticipated natural phenomena; Topographic variation; Dynamic scenery; Seasonal natural landscapes; Sequential landscape vistas; Interactive landscapes; Natural light and shadow, and subtle natural details; Hazardous natural elements. | [12,41,46,53,66,67,82,89,96,97,105,106,112] | |

| Richness of natural perceptual elements | Vegetation diversity; Plant layers; Chromatic diversity; Biodiversity; Landscape element diversity. | [36,41,53,66,67,74,96,106,109,112,113] | ||

| Greenway vegetation spatial patterns | Visual openness; Arboreal height; Dense vegetation; Landscape fragmentation indices; Greenway tortuosity; Sky openness; Three-dimensional green volume; Canopy density; Vegetation coverage rate; Green visibility index; Blue visibility index. | [31,36,41,46,53,66,67,74,89,96,99,106,107,108,109,112] | ||

| Environmental authenticity | Low artificial interference; High naturalness; Pristine natural features; Freedom from urban noise; Biomimetic design; Landscape ecological adaptation; Authenticity-focused design. | [19,41,53,66,96,105,106,107,109] | ||

| Supporting facilities | Basic service facilities | Trails; Signage clarity; Trash bins; Rain shelter facilities; Guardrails; Surveillance; Barrier-free facilities; Benches; Lighting facilities; Restrooms. | [41,46,53,54,72,81,89,102,103,105,106] | |

| Natural observation facilities | Ecological facilities; Nature education signs. | [12,72] | ||

| Residents’ activities within greenways | Pedestrian flow | Crowd density. | [53,66,105,107,114] | |

| Community environmental co-creation | Community environmental co-creation. | [22] | ||

| Nature-based activities and nature education | Nature-based activities; Nature education. | [44,53,81,110] | ||

| Others’ environmental behaviors | Others’ environmental behaviors. | [45,97,105] | ||

| Operational maintenance | Facility maintenance and vegetation care | Clear water quality; Vegetation pruning and care; Facility repair. | [44,46,67,97,102,103,105] |

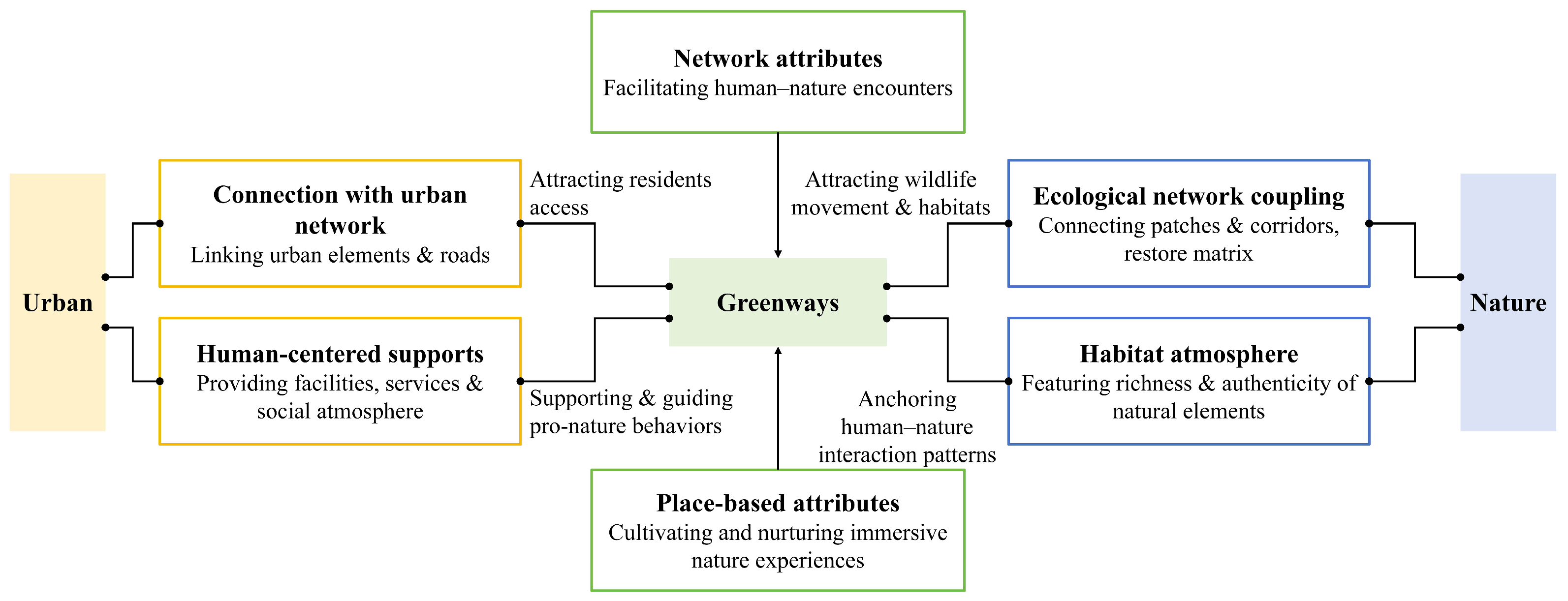

4. Discussion

4.1. Activation Effect of Urban-Greenway–Ecological Network Coupling

4.2. Anchoring and Enrichment Effect of Composite Place-Based Attributes

4.3. Nurturing Effect Through Sustained Human–Nature Interaction

5. Limitations and Future Recommendations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CCAT | Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| VGI | Volunteered Geographic Information |

| PCN | Park Connector Network |

References

- Kellert, S.R.; Wilson, E.O. The Biophilia Hypothesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-1-59726-906-3. [Google Scholar]

- Wyles, K.J.; White, M.P.; Hattam, C.; Pahl, S.; King, H.; Austen, M. Are Some Natural Environments More Psychologically Beneficial Than Others? The Importance of Type and Quality on Connectedness to Nature and Psychological Restoration. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 111–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Williams, A.; Knight, A. Developing a Biophilic Behavioural Change Design Framework—A Scoping Study. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 94, 128278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, R.A.; Irvine, K.N.; Devine-Wright, P.; Warren, P.H.; Gaston, K.J. Psychological Benefits of Greenspace Increase with Biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 2007, 3, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.; White, M.P.; Hunt, A.; Richardson, M.; Pahl, S.; Burt, J. Nature Contact, Nature Connectedness and Associations with Health, Wellbeing and pro-Environmental Behaviours. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 68, 101389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grinde, B.; Patil, G.G. Biophilia: Does Visual Contact with Nature Impact on Health and Well-Being? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2009, 6, 2332–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbiero, G.; Berto, R. Biophilia as Evolutionary Adaptation: An Onto- and Phylogenetic Framework for Biophilic Design. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 700709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, S.N.; Reis, M.V.D.; Nascimento, Â.M.P.D. Pandemic, Social Isolation and the Importance of People-Plant Interaction. Ornam. Hortic. 2020, 26, 399–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. Greenways as a Planning Strategy. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 131–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabos, J. Introduction and Overview—The Greenway Movement, Uses and Potentials of Greenways. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searns, R. The Evolution of Greenways as an Adaptive Urban Landscape Form. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beery, T.H.; Raymond, C.M.; Kyttä, M.; Olafsson, A.S.; Plieninger, T.; Sandberg, M.; Stenseke, M.; Tengö, M.; Jönsson, K.I. Fostering Incidental Experiences of Nature through Green Infrastructure Planning. Ambio 2017, 46, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Almeida, J.; Nunes, R.; Dias, T. People Prefer Greener Corridors: Evidence from Linking the Patterns of Tree and Shrub Diversity and Users’ Preferences in Lisbon’s Green Corridors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.; Simpson, G. Visitor Satisfaction with a Public Green Infrastructure and Urban Nature Space in Perth, Western Australia. Land 2018, 7, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Siu, K.W.M.; Gong, X.Y.; Gao, Y.; Lu, D. Where Do Networks Really Work? The Effects of the Shenzhen Greenway Network on Supporting Physical Activities. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 152, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Liang, J.; Chen, Q. Greenway Interventions Effectively Enhance Physical Activity Levels—A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1268502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P. Perception and Use of a Metropolitan Greenway System for Recreation. Landsc. Urban Plan. 1995, 33, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Browning, M.H.E.M.; Kee, F.; Hunter, R.F. How Do Awareness, Perceptions, and Expectations of an Urban Greenway Influence Residents’ Visits and Recreational Physical Activity? Evidence From the Connswater Community Greenway, Belfast, Northern Ireland. Leis. Sci. 2024, 46, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; De Meulder, B. User, Public, and Professional Perceptions of the Greenways in the Pearl River Delta, China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 7211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.; Adlakha, D.; Cardwell, C.; Cupples, M.; Donnelly, M.; Ellis, G.; Gough, A.; Hutchinson, G.; Kearney, T.; Longo, A.; et al. Investigating the Physical Activity, Health, Wellbeing, Social and Environmental Effects of a New Urban Greenway: A Natural Experiment (the PARC Study). Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Qi, J.; Xiao, S.; Wende, W.; Xin, Y. A Reflection on the Implementation of a Waterfront Greenway from a Social-Ecological Perspective: A Case Study of Huangyan-Taizhou in China. Land 2024, 13, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K.; Svendsen, E.; Johnson, M.; Landau, L. Activating Urban Environments as Social Infrastructure through Civic Stewardship. Urban Geogr. 2022, 43, 713–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, W.; Lin, G. The Use of Community Greenways: A Case Study on a Linear Greenway Space in High Dense Residential Areas, Guangzhou. Land 2019, 8, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawawi, A.A.; Porter, N.; Ives, C.D. Influences on Greenways Usage for Active Transportation: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Song, C.; Jiang, S.; Luo, H.; Zhang, P.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Li, K.; Li, N.; Guo, B.; et al. Effects of Urban Greenway Environmental Types and Landscape Characteristics on Physical and Mental Health Restoration. Forests 2024, 15, 679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Wang, X.; He, L.; Gu, Q.; Wei, X.; Xu, M.; Sullivan, W.C. Effects of Virtual Exposure to Urban Greenways on Mental Health. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1256897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kals, E.; Schumacher, D.; Montada, L. Emotional Affinity toward Nature as a Motivational Basis to Protect Nature. Environ. Behav. 1999, 31, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, F.S.; Frantz, C.M. The Connectedness to Nature Scale: A Measure of Individuals’ Feeling in Community with Nature. J. Environ. Psychol. 2004, 24, 503–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Empathizing with Nature: The Effects of Perspective Taking on Concern for Environmental Issues. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 391–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, P.W. Inclusion with Nature: The Psychology Of Human-Nature Relations. In Psychology of Sustainable Development; Schmuck, P., Schultz, W.P., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 61–78. ISBN 978-1-4615-0995-0. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Fagerholm, N.; Skov-Petersen, H.; Beery, T.; Wagner, A.; Olafsson, A. Shortcuts in Urban Green Spaces: An Analysis of Incidental Nature Experiences Associated with Active Mobility Trips. Urban For. Urban Green. 2023, 82, 127873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, S.L.; Westley, M.; Lovell, R.; Wheeler, B.W. Everyday Green Space and Experienced Well-Being: Thesignificance of Wildlife Encounters. Landsc. Res. 2018, 43, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, X.; Li, J.; Meng, L.; Wang, Z.; Yang, L. Difference of Usage Behavior between Urban Greenway and Suburban Greenway: A Case Study in Beijing, China. Land 2022, 11, 1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, I. Role of Restorative Natural Environments in Predicting Hikers’ pro-Environmental Behavior in a Nature Trail Context. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2024, 41, 596–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Popa, A.; Sun, H.; Guo, W.; Meng, F. Tourists’ Intention of Undertaking Environmentally Responsible Behavior in National Forest Trails: A Comparative Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theeba Paneerchelvam, P.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Maulan, S.; Shukor, S.F.A. The Use and Associated Constraints of Urban Greenway from a Socioecological Perspective: A Systematic Review. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 47, 126508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, C.E. Greenways for America; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0-8018-5140-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster, P.H.; Westphal, L.M. The Human Dimensions of Urban Greenways: Planning for Recreation and Related Experiences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2004, 68, 147–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka, R.H.; Kaplan, R. People Needs in the Urban Landscape: Analysis of Landscape And Urban Planning Contributions. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2008, 84, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, C.S.; Lee, B.K.; Turner, S. A Tale of Three Greenway Trails: User Perceptions Related to Quality of Life. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2000, 49, 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zheng, H.; Luo, S.; Liu, Q.; Yan, Z.; Huang, Q. Factors Influencing Users’ Perceived Restoration While Using Treetop Trails: The Case of the Fu and Jinjishan Forest Trails, Fuzhou, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audate, P.; Da, S.; Diallo, T. Understanding the Barriers and Facilitators of Urban Greenway Use among Older and Disadvantaged Adults: A Mixed-Methods Study in Quebec City. Health Place 2024, 89, 103340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.; Bai, Y.; Wang, R.; Yang, T.; Song, X.; Bai, B. Exploring Associations between the Built Environment and Cycling Behaviour around Urban Greenways from a Human-Scale Perspective. Land 2023, 12, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Smith, J.W.; Leung, Y.-F.; Seekamp, E.; Moore, R.L. Determinants of Responsible Hiking Behavior: Results from a Stated Choice Experiment. Environ. Manag. 2015, 56, 765–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.; Lee, J.K. Can Recreation Specialization Negatively Impact Pro-Environmental Behavior in Hiking Activity? A Self-Interest Motivational View. Leis. Sci. 2024, 46, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Stewart, W.; Chan, E. Place-Making upon Return Home: Influence of Greenway Experiences. Leis. Sci. 2023, 45, 46–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanniris, C.; Gavrilakis, C.; Hoover, M.L. Direct Experience of Nature as a Predictor of Environmentally Responsible Behaviors. Forests 2023, 14, 2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balletto, G.; Milesi, A.; Ladu, M.; Borruso, G. A Dashboard for Supporting Slow Tourism in Green Infrastructures. A Methodological Proposal in Sardinia (Italy). Sustainability 2020, 12, 3579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermida, M.A.; Neira, M.; Cabrera-Jara, N.; Osorio, P. Resilience in Latin American Cities: Behaviour vs. Space Quality in the Riverbanks of the Tomebamba River. Procedia Eng. 2017, 198, 467–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marušić, B.G.; Mihevc, N.; Dremel, M. Patterns of Using Places for Recreation and Relaxation in Peri-Urban Areas: The Case of Lake Podpeč, Slovenia. Urbani Izziv 2019, 30, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, E.; Deng, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, L.; Xiong, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Du, J.; Li, X.; Li, X. Exploring Restrictions to Use of Community Greenways for Physical Activity through Structural Equation Modeling. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1169728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Shi, Q.; Zhang, Y. Evaluation of the Health Promotion Capabilities of Greenway Trails: A Case Study in Hangzhou, China. Land 2022, 11, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Abidin, N.A.Z.; Mohamad, D. Exploring the Opportunities for Biophilic Design Application in Urban Pedestrian Environments in China under the Context of Climate Change: A Perspective of Affective Experience. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Urban Design and Planning, Urban Futures: Advancing Sustainable Urban Planning and Design, Semarang, Indonesia, 15 May 2024; Handayani, Dewi, S.P., Kurniati, R., Kurniawati, W., Wungo, G.L., Sariffudin, Ghozali, A., Rani, W.N.M.W.M., Amat, R.C., Wahab, M.H., et al., Eds.; Institute of Physics: London, UK, 2024; Volume 1394. [Google Scholar]

- McEwan, K.; Xenias, D.; Hodgkinson, S.; Hawkins, J.; Clark, S.; Xing, Y.; Ellis, C.; Cripps, R.; Brown, J.; Titherington, I. Greener Streets and Behaviours, and Green-Eyed Neighbours: A Controlled Study Evaluating the Impact of a Sustainable Urban Drainage Scheme in Wales on Sustainability. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2022, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Gan, H.; Qian, X.; Leng, J.; Wang, Y.; Wu, P. Riverside Greenway in Urban Environment: Residents’ Perception and Use of Greenways along the Huangpu River in Shanghai, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havránková, L.; Štych, P.; Ondr, P.; Moravcová, J.; Sláma, J. Assessment of the Connectivity and Comfort of Urban Rivers, a Case Study of the Czech Republic. Land 2023, 12, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareba, A.D.; Krzeminska, A.E.; Dzikowska, A. Urban Green Network—Synthesis of Environmental, Social and Economic Linkages in Urban Landscape. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; Yilmaz, I., Marschalko, M., Drusa, M., Antova, G., Eds.; Institute of Physics Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 362. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.; Reith, A. Using Nature-Based Solutions to Support Urban Regeneration: A Conceptual Study. Pollack Period. 2022, 17, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, M.; Sheppard, L. A Review of Critical Appraisal Tools Show They Lack Rigor: Alternative Tool Structure Is Proposed. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011, 64, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, M.; Sheppard, L. A General Critical Appraisal Tool: An Evaluation of Construct Validity. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2011, 48, 1505–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowe, M.; Sheppard, L.; Campbell, A. Reliability Analysis for a Proposed Critical Appraisal Tool Demonstrated Value for Diverse Research Designs. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012, 65, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CASP Checklists—Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Hong, Q.N.; Gonzalez-Reyes, A.; Pluye, P. Improving the Usefulness of a Tool for Appraising the Quality of Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Studies, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). Eval. Clin. Pract. 2018, 24, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Gu, W.; Liu, T.; Yuan, L.; Zeng, M. Increasing the Use of Urban Greenways in Developing Countries: A Case Study on Wutong Greenway in Shenzhen, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobster, P.H.; Kruger, L.E.; Schultz, C.L.; Henderson, J.R. Key Characteristics of Forest Therapy Trails: A Guided, Integrative Approach. Forests 2023, 14, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Maruthaveeran, S.; Yusof, M.J.M.; Dai, C. Exploring Factors Influencing Recreational Experiences of Urban River Corridors Based on Social Media Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, M.; MacKinnon, R.; Zari, M.; Glensor, K.; Park, T. Urgent Biophilia: Green Space Visits in Wellington, New Zealand, during the COVID-19 Lockdowns. Land 2022, 11, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolch, J.R.; Tatalovich, Z.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Byrne, J.; Jerrett, M.; Chou, C.-P.; Weaver, S.; Wang, L.; Fulton, W.; Reynolds, K. Proximity and Perceived Safety as Determinants of Urban Trail Use: Findings from a Three-City Study. Environ. Plan. A 2010, 42, 57–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Ding, L.; Kou, H.; Tan, S.; Long, H. Effects and Environmental Features of Mountainous Urban Greenways (MUGs) on Physical Activity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, R.; Lu, H.; Fernandez, J.; Wang, T. Why Do We Love the High Line? A Case Study of Understanding Long-Term User Experiences of Urban Greenways. Comput. Urban Sci. 2023, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Y.; Qiao, X.-J. Behavioral Conflicts in Urban Greenway Recreation: A Case Study of the “Three Rivers and One Mountain” Greenway in Xi’an, China. Land 2024, 13, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, M.A.; Hunter, R.F.; McAneney, H.; Cupples, M.E.; Donnelly, M.; Ellis, G.; Hutchinson, G.; Prior, L.; Stevenson, M.; Kee, F. Physical Activity and the Rejuvenation of Connswater (PARC Study): Protocol for a Natural Experiment Investigating the Impact of Urban Regeneration on Public Health. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.-Y.; Chuang, C. Preferences of Tourists for the Service Quality of Taichung Calligraphy Greenway in Taiwan. Forests 2018, 9, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.; Qiu, N.; Zhang, T. What Causes the Spatiotemporal Disparities in Greenway Use Intensity? Evidence from the Central Urban Area of Beijing, China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 957641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Monasterio, M.; Alonso-Monasterio, P.; Vinals, M.J. Natusers’ Motivations and Attitudes in Urban Green Corridors: Challenges and Opportunities. Case Study of the Parc Fluvial Del Túria (Spain). Boletín De La Asoc. De Geógrafos Españoles 2015, 68, 369–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, C. Users’ Recreation Choices and Setting Preferences for Trails in Urban Forests in Nanjing, China. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 73, 127602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durán Vian, F.; Pons Izquierdo, J.J.; Serrano Martínez, M. River-City Recreational Interaction: A Classification of Urban Riverfront Parks and Walks. Urban For. Urban Green. 2021, 59, 127042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzoulas, K.; James, P. Peoples’ Use of, and Concerns about, Green Space Networks: A Case Study of Birchwood, Warrington New Town, UK. Urban For. Urban Green. 2010, 9, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, S.J.; Larson, L.R.; Shafer, C.S.; Hallo, J.C.; Fernandez, M. Greenway Use and Preferences in Diverse Urban Communities: Implications for Trail Design and Management. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2018, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Zhang, Q.; Guo, W.; Lin, K. Hikers’ pro-Environmental Behavior in National Park: Integrating Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. Front. For. Glob. Change 2022, 5, 1068960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, L.; Zhu, Y.; Xu, X.; Yang, J.; Zheng, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, H.; Zhu, L. The Influence of Visitors’ Recreation Experience and Environmental Attitude on Environmentally Responsible Behavior: A Case Study of an Urban Forest Park, China. Forests 2022, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senes, G.; Rovelli, R.; Bertoni, D.; Arata, L.; Fumagalli, N.; Toccolini, A. Factors Influencing Greenways Use: Definition of a Method for Estimation in the Italian Context. J. Transp. Geogr. 2017, 65, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstenberg, T.; Baumeister, C.F.; Schraml, U.; Plieninger, T. Hot Routes in Urban Forests: The Impact of Multiple Landscape Features on Recreational Use Intensity. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 203, 103888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rembeza, M. Integrating Art into Places in Transition—Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston as a Case Study. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 052070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naserisafavi, N.; Coyne, T.; Zurita, M.; Zhang, K.; Prodanovic, V. Community Values on Governing Urban Water Nature-Based Solutions in Sydney, Australia. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 322, 116063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, L.; Ferreira, C.S.S.; Pereira, P. Environmental and Socioeconomic Factors Influencing the Use of Urban Green Spaces in Coimbra (Portugal). Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 792, 148293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adlakha, D.; Tully, M.A.; Mansour, P. Assessing the Impact of a New Urban Greenway Using Mobile, Wearable Technology-Elicited Walk- and Bike-Along Interviews. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Chen, Y.; Guan, L. Which Factors Affect the Visual Preference and User Experience: A Case Study of the Mulan River Greenway in Putian City, China. Forests 2024, 15, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Xu, N.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J.; Zheng, Y. Optimizing Perceived Jogging Supportiveness for Enhanced Sustainable Greenway Design Based on Computer Vision: Implications of the Nonlinear Influence of Perceptual and Physical Characteristics. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansen, C.; Reynolds, K.D.; Wolch, J.; Byrne, J.; Chou, C.-P.; Boyle, S.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Lienemann, B.A.; Weaver, S.; Jerrett, M. The Association of Trail Features With Self-Report Trail Use by Neighborhood Residents. J. Phys. Act. Health 2020, 17, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yu, L.; Chen, X.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Gong, P. Identifying Potential Urban Greenways by Considering Green Space Exposure Levels and Maximizing Recreational Flows: A Case Study in Beijing’s Built-Up Areas. Land 2024, 13, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benton, J.S.; Cotterill, S.; Anderson, J.; Macintyre, V.G.; Gittins, M.; Dennis, M.; French, D.P. A Natural Experimental Study of Improvements along an Urban Canal: Impact on Canal Usage, Physical Activity and Other Wellbeing Behaviours. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhang, H.; Dong, X.; Shen, J. The Impact of Street Greenery on Active Travel: A Narrative Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1337804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Hall, C.M. Application of EMGB to Study Impacts of Public Green Space on Active Transport Behavior: Evidence from South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, M.; Jin, Y. Landscape Aesthetic Value of Waterfront Green Space Based on Space–Psychology–Behavior Dimension: A Case Study along Qiantang River (Hangzhou Section). Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mottaghi, M.; Kärrholm, M.; Sternudd, C. Blue-Green Solutions and Everyday Ethicalities: Affordances and Matters of Concern in Augustenborg, Malmö. Urban Plan. 2020, 5, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.R.; Bell, T.L.; Pfautsch, S. A Review of Residents’ Perceptions of Urban Street Trees: Addressing Ambivalence to Promote Climate Resilience. Land 2025, 14, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, M.; Xu, Y.; Tao, J. “Interface-Element-Perception” Model to Evaluation of Urban Sidewalk Visual Landscape in the Core Area of Beijing. Front. Archit. Res. 2024, 13, 960–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahyani; Hamzah, B.; Syarif, E. Greenway Model as a Support of Makassar Smart City. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 473, 012121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Liu, L.; Wu, H.; Peng, Z.; Sun, Z. Change of Residents’ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Urban Green Space Pre- and Post- COVID-19 Pandemic. Land 2022, 11, 1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diep, L.; Parikh, P.; Duarte, B.P.D.S.; Bourget, A.F.; Dodman, D.; Martins, J.R.S. “It Won’t Work Here”: Lessons for Just Nature-Based Stream Restoration in the Context of Urban Informality. Environ. Sci. Policy 2022, 136, 542–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantartzis, A.; Lemonakis, P.; Malesios, C.; Daoutis, C.; Galatsidas, S.; Arabatzis, G. Attitudes and Views of Citizens Regarding the Contribution of the Trail Paths in Protection and Promotion of Natural Environment. Land 2022, 11, 1585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansor, M.; Said, I.; Mohamad, I. Experiential Contacts with Green Infrastructure’s Diversity and Well-Being of Urban Community. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 49, 257–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorwart, C.E.; Moore, R.L.; Leung, Y.-F. Visitors’ Perceptions of a Trail Environment and Effects on Experiences: A Model for Nature-Based Recreation Experiences. Leis. Sci. 2009, 32, 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Sun, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cheng, C. Evaluation and Optimization of Restorative Environmental Perception of Treetop Trails: The Case of the Mountains-to-Sea Trail, Xiamen, China. Land 2023, 12, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Li, J.; Lin, X.; Yu, Y. Greenway Cyclists’ Visual Perception and Landscape Imagery Assessment. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 541469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarrete-Hernandez, P.; Laffan, K. The Impact of Small-Scale Green Infrastructure on the Affective Wellbeing Associated with Urban Sites. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Zhou, F.; Lin, J.; Yang, Q.; Lyu, M. A Study on Landscape Feature and Emotional Perception Evaluation of Waterfront Greenway. Environ. Res. Commun. 2024, 6, 095023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.H.; Lee, T.H. How Do Recreation Experiences Affect Visitors’ Environmentally Responsible Behavior? Evidence from Recreationists Visiting Ancient Trails in Taiwan. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 705–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancillotto, L.; Mosconi, F.; Labadessa, R. A Matter of Connection: The Importance of Habitat Networks for Endangered Butterflies in Anthropogenic Landscapes. Urban Ecosyst. 2024, 27, 1623–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundher, R.; Abu Bakar, S.; Maulan, S.; Gao, H.; Mohd Yusof, M.J.; Aziz, A.; Al-Sharaa, A. Identifying Suitable Variables for Visual Aesthetic Quality Assessment of Permanent Forest Reserves in the Klang Valley Urban Area, Malaysia. Urban Sci. 2023, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, L.; Li, C. Attraction and Retention Green Place Images of Taipei City. Forests 2024, 15, 710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honey-Rosés, J.; Zapata, O. Green Spaces with Fewer People Improve Self-Reported Affective Experience and Mood. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Sha, J.; Scott, N. Restoration of Visitors through Nature-Based Tourism: A Systematic Review, Conceptual Framework, and Future Research Directions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosa, C.D.; Collado, S. Experiences in Nature and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Setting the Ground for Future Research. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Database | Search Query |

|---|---|

| Web of Science | (“urban*” OR “cit*”) AND ((“behavio*” OR “activit*” OR “use pattern*” OR “usage pattern*” OR “user* behavio*”) OR (“biophilia” OR ((“nature” OR “environment*”) AND (“connectedness” OR “connection” OR “affinity” OR “emotion*” OR “love” OR “care” OR “empathy” OR “inclusion” OR “motiv*” OR “responsible behavior”))) OR (“immersive perception*” OR “engaging perception*” OR “acceptance behavior*” OR “natural acceptance”)) AND (“greenway*” OR “linear park*” OR “linear green space*” OR “park connector*” OR “green corridor*” OR “green infrastructure*”)(Topic) |

| Scopus | TITLE-ABS-KEY(“urban*” OR “cit*”) AND ((“behavio*” OR “activit*” OR “use pattern*” OR “usage pattern*” OR “user* behavio*”) OR (“biophilia” OR ((“nature” OR “environment*”) AND (“connectedness” OR “connection” OR “affinity” OR “emotion*” OR “love” OR “care” OR “empathy” OR “inclusion” OR “motiv*” OR “responsible behavior”))) OR (“immersive perception*” OR “engaging perception*” OR “acceptance behavior*” OR “natural acceptance”)) AND (“greenway*” OR “linear park*” OR “linear green space*” OR “park connector*” OR “green corridor*” OR “green infrastructure*”) |

| Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Research content |

|

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Study design |

|

|

| Literature type |

|

|

| CCAT Domain | Core Evaluation Focus |

|---|---|

| Preliminaries | Title includes study aims and design; abstract contains balanced, key information; text provides sufficient detail for reproducibility and presents clear writing, tables, diagrams, or figures. |

| Introduction | Summarizes current knowledge and clarifies the specific problem addressed; states at least one primary objective, hypothesis, or aim; secondary questions (if applicable) are aligned with the primary objective. |

| Design | Specifies the chosen research design and its rationale, ensuring suitability for the research question; details interventions/treatments/exposures (including validity and reliability) and clearly defines outcomes/outputs/predictors/measures (with validity and reliability); identifies potential bias and confounding variables; and ensures appropriate sequence generation, group allocation, and equivalent treatment of participants. |

| Sampling | Describes the sampling method and its rationale, ensuring suitability for the study; specifies sample size, calculation method, and rationale; defines target/actual/sample populations, explicit inclusion/exclusion criteria, and transparent recruitment procedures. |

| Data collection | Details the chosen data collection method and its rationale, ensuring suitability; includes clear protocols (dates, locations, personnel, materials); implements methods to enhance measurement quality (e.g., pilot studies, calibration); and manages non-participation, withdrawal, or lost data. |

| Ethical matters | Ensures informed consent and equity for participants; protects privacy, confidentiality, or anonymity; provides ethical approval statements; discloses funding sources and conflicts of interest; addresses researcher subjectivities and potential impacts on outcomes. |

| Results | Uses appropriate statistical/non-statistical methods to analyze/integrate/interpret primary and additional outcomes; reports participant flow, baseline characteristics, raw data analysis, and response rates; summarizes results with precision and effect size; considers benefits/harms, unexpected results, and outlying data. |

| Discussion | Interprets results in the context of current evidence and study objectives; draws inferences consistent with data strength; explores alternative explanations for results and accounts for bias/confounding; discusses the study’s practical usefulness and generalizability; highlights strengths, limitations, and suggestions for future research. |

| Pro-Nature Behavior Types | Classification Criteria | Representative Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Visitation | Primary greenway users exhibit visitation frequencies of fewer than once per month. | [15,48,49,50] |

| Usage habits | Primary greenway users demonstrate usage frequencies ranging from daily to at least once per month. | [51,52] |

| Alignment with nature | Greenway content emphasizes user–nature interaction behaviors or nature perception experiences; The study focuses on analyzing the mechanisms through which greenways influence pro-environmental behaviors among residents, or how nature experiences along greenways shape residents’ environmentally responsible behaviors. | [41,53,54] |

| Mixed-type | The study focuses on the mechanisms of multiple pro-nature behaviors promoted by greenways. | [33,36,55] |

| Greenway Network–Place Attributes | Elements |

|---|---|

| Network attributes | The internal network structure of greenways themselves; connectivity between greenways and road networks; connectivity between greenways and pedestrian/cycling networks; linkages between greenways and urban facilities; and linkages between greenways and ecological networks. |

| Place-based attributes | Landscape resources; natural perception elements; supporting facilities; residents’ activities within greenways; and operational maintenance. |

| Greenway Attributes | Associated Elements | Built Environment Characteristics | Indicators | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network attributes | The internal network structure of greenways themselves | Greenway network internal connectivity | Greenway network density; Greenway node connectivity ratio. | [15] |

| Greenway internal movement barriers | Path length; Terrain complexity; Physical barriers. | [36,48,69,77,83,84] | ||

| Connectivity between greenways and road networks | Greenways located in urban areas | Greenways located in suburban areas; Travel distance; Distance to urban areas. | [33,67,77] | |

| Greenway road network connectivity | Intersection count; Road network global integration value; Road network local integration value; 15 min greenway walkability; High-choice segments; Bridge-equipped routes; Road density; Accessibility to transit, metro, and bikeshare stations; Motor vehicle Parking facilities; Bicycle racks and rental services; Distance to urban arterial roads. | [15,19,24,36,43,49,50,55,67,69,74,75,77,83,85] | ||

| Linkages between greenways and urban facilities | Distribution of tourism resources around greenways | Distribution of accommodation and catering facilities. | [48,71] | |

| Scenic spot count. | [48,75,83] | |||

| Distribution of residential buildings around greenways | Residential area density. | [15,75] | ||

| Surrounding land-use diversity | Land-use mix degree. | [15,43] | ||

| Accessibility to nearby parks and green spaces | Park green spaces. | [15,43,75] | ||

| Place-based attributes | Landscape resources | Uniqueness of landscape elements | Water bodies and riparian scenery; Unique viewpoints; Repurposed historic railways; Protected habitats. | [19,33,67,69,71,75,84] |

| Scale of landscape elements | Greenway hierarchy. | [15] | ||

| Greenway social reputation | Social media ratings; User review content; Personal recommendations; Media promotion; Greenway recognition. | [19,24,33,48,71,85] | ||

| Natural perception elements | Natural perceptual trigger elements | Distance to water bodies; Shade. | [19,50,55,75,78] | |

| Greenway vegetation spatial patterns | Greening level; Sense of enclosure; Sky openness; Greenway width; Greenway tortuosity; Relative vegetation abundance; Green space ratio; Tree species. | [13,43,49,55,66,67,71,75,78,84] | ||

| Supporting facilities | Basic service facilities | Trails; Benches; Water stations; Restrooms; Trash bins; Lighting facilities; Surveillance; Signage clarity; Guardrails; Emergency equipment. | [19,24,36,49,55,67,71,74,77,86] | |

| Recreational and sports facilities | Children’s playgrounds; Fitness equipment; Public activity spaces. | [19,49,67,86,87] | ||

| Social nodes | Small open areas; Shaded pavilions; Table and seating. | [55,74,85,86] | ||

| Residents’ activities within greenways | Large-scale cultural and recreational events | Cultural and recreational events. | [12,74,87] | |

| Visitor flow volume | Visitor density. | [19,24,36,50] | ||

| Others’ environmental behaviors | Uncivilized behaviors. | [36,67,72,88] | ||

| Operational maintenance | Facility maintenance and vegetation care | Facility cleanliness; Facility repair; Vegetation pruning and care. | [36,71,74,77,78,89] | |

| Entrance fees | Entrance fees | [74] | ||

| Commercial vendors | Commercial vendors | [67,71] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chai, D.; Liu, K. The Network–Place Effect of Urban Greenways on Residents’ Pro-Nature Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411117

Chai D, Liu K. The Network–Place Effect of Urban Greenways on Residents’ Pro-Nature Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411117

Chicago/Turabian StyleChai, Disheng, and Kun Liu. 2025. "The Network–Place Effect of Urban Greenways on Residents’ Pro-Nature Behaviors: A Systematic Review" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411117

APA StyleChai, D., & Liu, K. (2025). The Network–Place Effect of Urban Greenways on Residents’ Pro-Nature Behaviors: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 17(24), 11117. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411117