2.1. Cluster Agglomeration and Dynamic Competitive Advantage

Cluster agglomeration refers to the externalities generated by the spatial proximity of enterprises and related industrial activities concentrated within the same region. These benefits include knowledge spillovers, specialized division of labor, complete supply chains, and market expansion [

20]. Porter (1990) highlighted that industrial clusters enhance firms’ productivity, innovation capabilities, and competitive advantage, thereby forming the foundation for regional competitive advantage [

21]. Similarly, Krugman (1991), from the perspective of new economic geography, explained that firms naturally cluster due to economies of scale, reduced transportation costs, and market potential, underscoring the crucial role of cluster in economic development and industrial growth [

22].

Dynamic competitive advantage emphasizes a firm’s ability to sustain market leadership in rapidly changing environments through the continuous adaptation of strategies, technologies, and resource configurations [

23]. From the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities [

24,

25], a firm’s dynamic competitive advantage arises from its ability to continuously sense opportunities, seize them, and reconfigure resources in uncertain environments. Clustering provides favorable conditions for the development of this capability. The dense knowledge networks and social connections within clusters enable enterprises to achieve resource integration and capability reallocation more readily through learning, sharing, and interaction [

26]. The accumulation of resources and institutional legitimacy allows clustered enterprises to expand resource utilization and reconstruct capabilities [

27]. However, cluster agglomeration also reveals that overly entrenched relationships or homogenized knowledge can constrain firms’ capacity for innovation and resource reorganization [

28]. Collaboration with heterogeneous research institutions and the restructuring of knowledge help enterprises overcome these constraints and foster innovative dynamism [

29].

Clustering theory posits that firms entering industrial clusters benefit from greater spillover knowledge, specialized labor, and resources from surrounding institutions through frequent transactions and informal interactions, enhancing innovation and performance [

30]. The dynamic capability perspective emphasizes that enterprises must continuously and rapidly sense environmental changes while integrating and reorganizing internal and external resources to maintain dynamic competitive advantage in highly volatile environments [

31,

32]. Existing research further indicates that intense competition and close collaboration within clusters facilitate organizational learning and dynamic capabilities, thereby transforming cluster resources into sustainable competitive advantages [

33]. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Cluster agglomeration exerts a positive influence on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

To further investigate how cluster agglomeration shape the formation of dynamic competitive advantage, scholars have conceptualized the cluster agglomeration as a multidimensional construct comprising collaborative opportunities, specialized labor, and technology sharing [

34,

35]. These dimensions not only represent the specific pathways through which enterprises acquire resources and interact within clusters but also reveal the diverse support mechanisms by which clustering facilitates the evolution of enterprise capabilities.

First, collaborative opportunities provide firms with access to a broad range of valuable external resources. Through inter-firm partnerships and network connections, companies can obtain scarce, inimitable resources that substantially strengthen their competitiveness [

36]. Collaboration fosters trust, knowledge transfer, and mutual learning among partners, thereby enhancing firms’ resource integration and adaptive capabilities [

37]. Drawing from the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities [

24,

25], collaborative opportunities improve firms’ sensing capabilities, making them more adept at identifying market opportunities. They also enhance firms’ seizing capabilities through better resource coordination and increase flexibility in resource restructuring via collaborative learning. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1a. Collaborative opportunities exert a positive influence on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

Specialized labor provides firms with highly skilled expertise and knowledge, thereby fostering innovation and research and development activities within clusters, and supports the overall competitiveness of firms by optimizing resource allocation and increasing labor productivity [

38,

39]. Within clusters, specialized professionals foster collaboration and knowledge diffusion among enterprises, thereby enhancing their market competitiveness [

40]. From the perspective of the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities [

24,

25], specialized labor serves as a critical human resource foundation for firms’ sensing and reconfiguring capabilities. Highly skilled employees can detect technological shifts earlier, absorb external knowledge effectively, and rapidly reconfigure internal processes to sustain enduring competitive advantages. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1b. Specialized labor exerts a positive influence on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

Technology sharing plays a crucial role in accelerating knowledge transfer and enabling firms to rapidly absorb external technologies, thereby enhancing their competitive advantage [

41]. Through technology sharing, enterprises can integrate external technologies into their internal research and development processes, thereby reducing research and development costs and shortening product time-to-market [

42,

43]. Drawing on the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities [

24,

25], technology sharing enhances firms’ ability to sense emerging technologies, improves their capacity to seize opportunities through collaborative innovation, and supports sustained competitive advantage via resource restructuring. Continuous knowledge exchange and co-learning enable firms to consistently renew their capabilities and strengthen their dynamic competitive advantages. Based on these insights, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1c. Technology sharing exerts a positive influence on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

2.2. Boundary Spanning and Dynamic Competitive Advantage

Boundary spanning refers to the process through which enterprises transcend cognitive, geographical, and technological boundaries. By acquiring external heterogeneous knowledge and reconfiguring internal organizational knowledge, firms can identify new business opportunities, enter new markets, pursue new collaborations, and address the practical challenge of limited internal knowledge resources [

44]. Boundary spanning behavior enables enterprises to access external technologies, markets, and resources by breaking traditional organizational boundaries [

45]. Research indicates that boundary spanning not only facilitates external knowledge acquisition but also enhances competitive advantage through interactions across organizations and cross-industry interactions [

46,

47]. From the perspective of the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities, boundary spanning enhances an organization’s capacity to develop and renew dynamic competitive advantage in uncertain environments by stimulating three key processes: opportunity sensing, value capture, and resource reconfiguration [

24,

25]. As a result, boundary spanning equips firms with the capability to maintain competitiveness and achieve long-term competitive advantage [

23].

Although previous studies have shown that boundary spanning promotes competitive advantage through dynamic capability mechanisms [

48,

49], existing research has paid limited attention to how firms transform externally acquired knowledge into dynamic competitive advantages through knowledge renewal within clusters. Based on this gap, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2. Boundary spanning exerts a positive influence on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

2.3. Cluster Agglomeration, Knowledge Renewal, and Dynamic Competitive Advantage

Industrial clustering creates an environment marked by frequent interactions and knowledge exchange, enabling firms to acquire, diffuse, and recombine knowledge more efficiently [

35]. Within clusters, firms can access technological advancements, market intelligence, and management expertise through frequent formal and informal channels. This continuous flow facilitates the updating and adaptation of existing organizational knowledge, enhancing firms’ responsiveness [

50]. By drawing on absorptive capacity theory, enterprises can use their existing knowledge base to recognize and assimilate external knowledge and transform it into internal capabilities [

51,

52], thereby creating the conditions necessary for continuous knowledge renewal. Existing studies indicate that clusters also foster a dual mechanism of competition and cooperation: while competition encourages differentiation, cooperation provides cross-organizational knowledge sources. This interplay enables knowledge to be applied across different technological pathways, thereby promoting knowledge renewal [

53,

54].

Knowledge renewal involves the socialization, externalization, and reintegration of existing knowledge, enabling firms to create new knowledge systems through organizational capture, integration, and linkage [

13]. In dynamic environments, firms that successfully acquire knowledge across geographic and organizational boundaries and integrate it into internal processes can respond swiftly to market opportunities and reorganize resources, thereby enhancing sustained competitive performance [

55]. Based on the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities, enterprises identify external knowledge opportunities through sensing mechanisms and internalize them by leveraging their absorptive capacity. They embed newly acquired knowledge into processes and products through integration and transformation, and further optimize resource allocation through restructuring and redeployment to achieve strategic adjustment [

24,

25]. This micro-level mechanism clarifies how knowledge renewal translates into dynamic capabilities at the operational level, enabling firms to sustain competitive advantage in rapidly changing environments.

Although existing research has examined the role of cluster agglomeration in facilitating knowledge flows and innovation, limited attention has been paid to the underlying mechanisms through which knowledge renewal within clusters shapes dynamic competitive advantage. In the context of industrial clusters, a key question arises: how do enterprises integrate external knowledge with internal experience through knowledge renewal in order to optimize resource allocation and strategic processes, thereby forming sustained dynamic competitive advantages in rapidly changing environments? Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3. Knowledge renewal mediates the relationship between cluster agglomeration and firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

2.4. Boundary Spanning, Knowledge Renewal, and Dynamic Competitive Advantage

In studies of firms within clusters, boundary spanning is widely recognized as a critical mechanism for facilitating knowledge renewal. Enterprises acquire heterogeneous knowledge and resources through search activities that cross organizational or technological boundaries, thereby facilitating knowledge integration and re-creation [

14,

56]. Drawing on absorptive capacity theory, organizations can identify and internalize external knowledge by leveraging their existing knowledge base, which in turn enhances their ability to integrate new knowledge [

51,

52]. Prior research indicates that a firm’s dynamic capabilities consist of three core components: sensing opportunities, integrating resources, and rapidly reconfiguring organizational capabilities [

31]. Knowledge renewal serves as a crucial mechanism that transforms externally acquired knowledge, obtained through boundary spanning activities, into deployable organizational resources [

57]. Effective boundary spanning enhances the acquisition of external knowledge while also improving the efficiency of internal knowledge transfer through structured communication and sharing mechanisms. By reducing uncertainty and strengthening trust among collaborating organizations, it provides a strong foundation for the continuous advancement of knowledge renewal capabilities [

58,

59].

In dynamic competitive environment, firms must continuously optimize and reconstruct existing knowledge to maintain a competitive edge. Knowledge renewal serves as a key driver of technological and product iteration while also acting as a central mechanism enabling firms to respond effectively to rapidly changing markets [

41]. Based on the microfoundations of dynamic capabilities, knowledge renewal entails perceiving external opportunities and new knowledge, integrating and transforming that knowledge for application in organizational processes and product innovation, and restructuring or redeploying resources to optimize resource allocation in support of strategic adjustments [

24,

25]. Through this process, enterprises can not only improve their ability to rapidly adapt to environmental changes but also strengthen organizational learning and decision-making efficiency, thereby cultivating dynamic competitive advantage [

23].

Although existing studies have examined the role of boundary spanning in knowledge acquisition and innovation outcomes, limited attention has been paid to how firms effectively transform knowledge obtained through boundary spanning into dynamic competitive advantages via knowledge renewal. This is particularly evident in the context of clusters, where the specific mechanisms at work have yet to be fully clarified. For cluster-based enterprises, boundary spanning activities provide access to diverse external knowledge resources. However, how such resources are converted into sustained competitive advantages that enable firms to navigate rapidly changing market environments remains an open question. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4. Knowledge renewal mediates the relationship between boundary spanning and firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

2.5. The Moderating Effect of Coopetition Relationship

In a fiercely competitive and rapidly changing environment, firms cannot sustain competitive advantage solely through knowledge sharing. Cluster agglomeration creates the foundational conditions for developing dynamic competitive advantage by facilitating knowledge flow, resource integration, and experience sharing among enterprises [

60]. At the same time, firms often maintain both cooperative and competitive relationships simultaneously. This dual interaction pattern is referred to as coopetition relationship [

16]. Existing research indicates that coopetition relationships can moderate the impact of the innovation context on firm performance and innovation outcomes [

61,

62]. Specifically, a healthy coopetition relationship can encourage firms within a cluster to be more willing to share information and resources, while simultaneously driving efficiency gains through competitive pressures [

63]. This interplay enhances both the depth and quality of knowledge sharing, strengthens organizational learning, and improves adaptability, thereby reinforcing dynamic competitive advantage [

64,

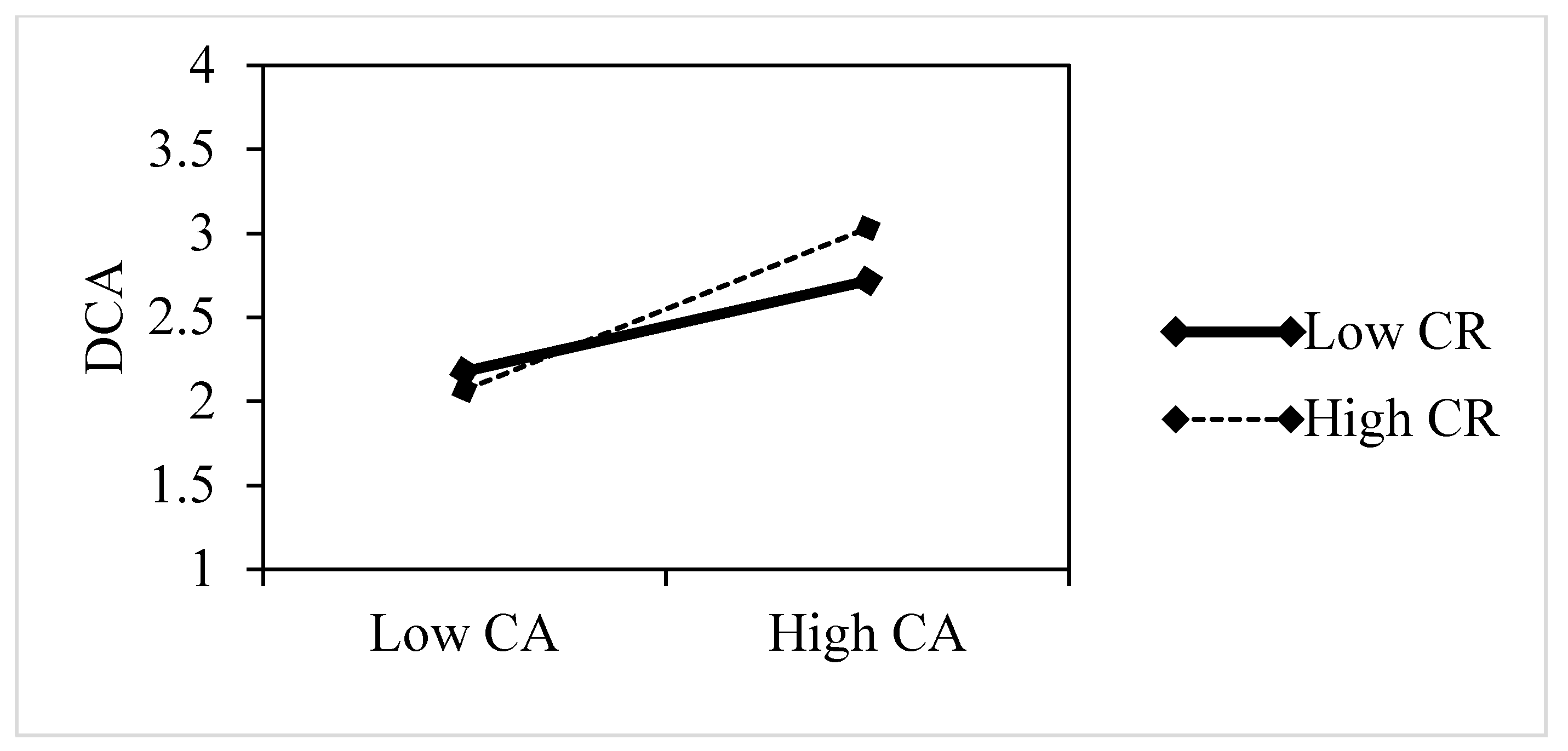

65]. However, the existing literature remains limited, as it predominantly examines Western developed markets or specific industries and pays insufficient attention to how differences in firms’ absorptive capacity and the balance between cooperation and competition shape performance outcomes. This study addresses this gap by investigating how, within Chinese industrial clusters, coopetition relationship positively moderates the effect of cluster agglomeration on dynamic competitive advantage when cooperation and competition are appropriately balanced and when firms’ absorptive capacity is aligned with external knowledge flows. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Coopetition relationship positively moderates the impact of the cluster agglomeration on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

In this study, although cluster agglomeration, boundary spanning, and coopetition relationships all involve knowledge linkages among enterprises, they differ in their focal concerns. Cluster agglomeration highlights the advantages derived from knowledge sharing and resource integration within geographically concentrated environments [

34]. Boundary spanning emphasizes an organization’s capacity to proactively acquire heterogeneous external knowledge [

11]. Meanwhile, coopetition relationships underscore the conditional effects of knowledge flow and innovation dynamics under the simultaneous presence of cooperation and competition [

66].

In today’s complex and dynamic business environment, firms enhance their dynamic competitive advantage by acquiring external knowledge, technologies, and resources across organizational boundaries [

48]. In moderately competitive environments, cooperative interactions are often strengthened, enhancing the positive effects of boundary spanning [

67]. Under such conditions, firms can more effectively acquire external resources through resource sharing and technological integration, improving market adaptability and reinforcing competitive advantages [

68]. Under conditions of balanced cooperation and competition, and when firms’ absorptive capacities are well-aligned, a moderate level of coopetition relationship can stimulate innovation incentives and learning motivation while sustaining knowledge flow and resource integration through collaborative mechanisms. This, in turn, strengthens the efficiency with which boundary spanning activities are transformed into dynamic competitive advantages [

69]. Although prior studies have shown that coopetition relationships play a moderating role in innovation contexts [

62,

70], most have concentrated on innovation outputs or firm performance. Far fewer have examined how coopetition relationship facilitates boundary spanning learning and resource integration, key components of boundary spanning activities, and even fewer have explored how these processes contribute to the formation of dynamic competitive advantages within clusters. This study addresses these gaps by investigating how coopetition relationship in Chinese industrial clusters positively moderates the effect of boundary spanning on dynamic competitive advantage. Based on this, the following hypotheses is proposed:

H6. Coopetition relationship positively moderates the effect of boundary spanning on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

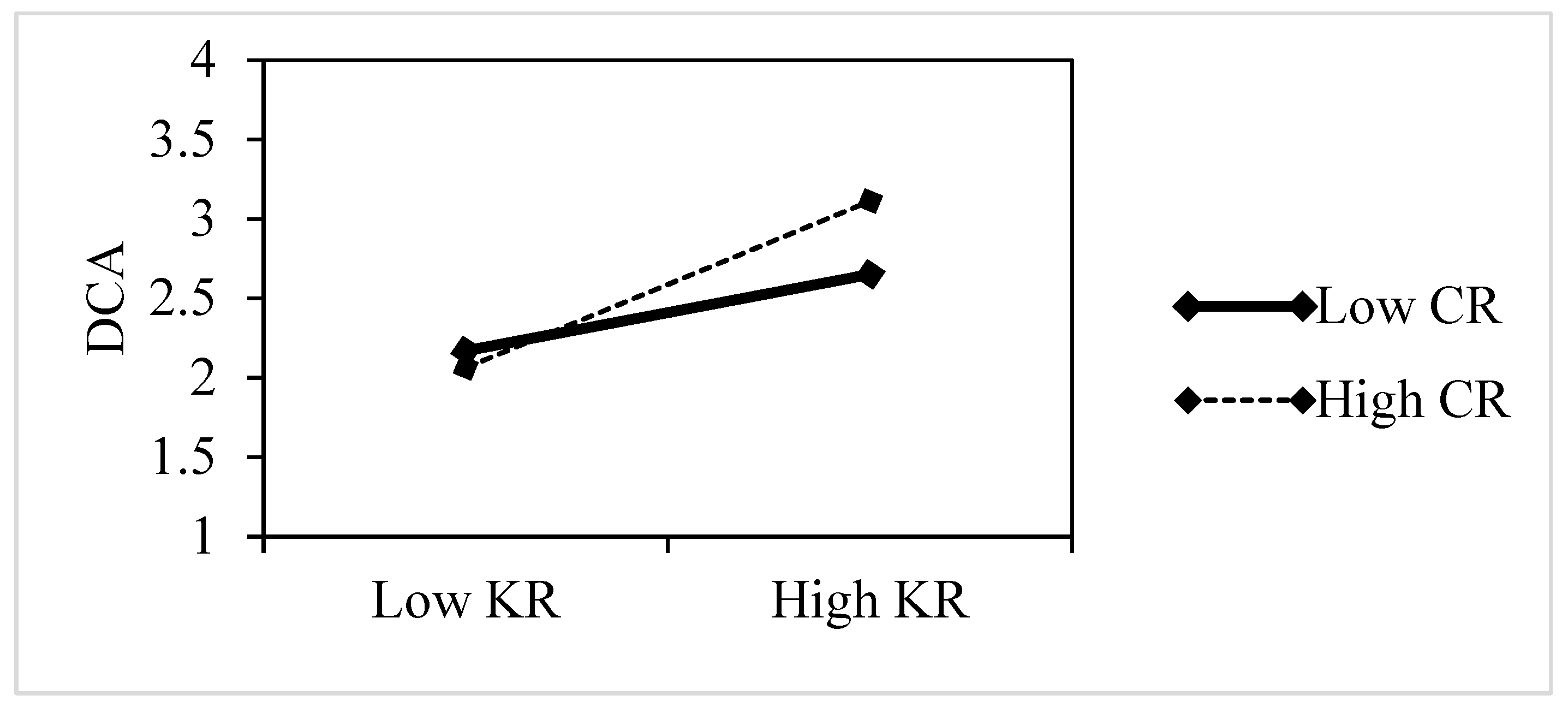

Existing research has found that knowledge renewal enables organizations to acquire, integrate, and apply new knowledge, driving the updating and restructuring of existing knowledge bases. This process enhances market adaptability, overcomes technological bottlenecks, and generates new sources of competitive advantage [

71]. Coopetition relationship strengthens the depth and breadth of collaboration, allowing firms to efficiently leverage external knowledge while protecting their core competencies. This, in turn facilitates knowledge renewal and integration, further strengthening dynamic competitive advantage [

72]. The coopetition relationship between firms significantly shapes the effectiveness of knowledge renewal. When cooperation and competition are held in moderate balance, firms are better positioned to share resources, integrate external knowledge, and enhance the efficiency with which knowledge renewal is transformed into dynamic competitive advantage [

73]. In contrast, when opportunistic behaviors, knowledge leakage risks, or insufficient absorptive capacity arise, heightened competition may weaken the outcomes of knowledge renewal. Therefore, this study investigates how coopetition relationship positively moderates the effect of knowledge renewal on dynamic competitive advantage within Chinese cluster contexts, specifically under conditions where cooperation and competition are balanced and firms’ absorptive capacities are well-matched. This research fills a gap in the existing literature, which has paid limited attention to the operational mechanisms underlying knowledge renewal processes. Based on this reasoning, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H7. Coopetition relationship positively moderates the effect of knowledge renewal on firms’ dynamic competitive advantage within clusters.

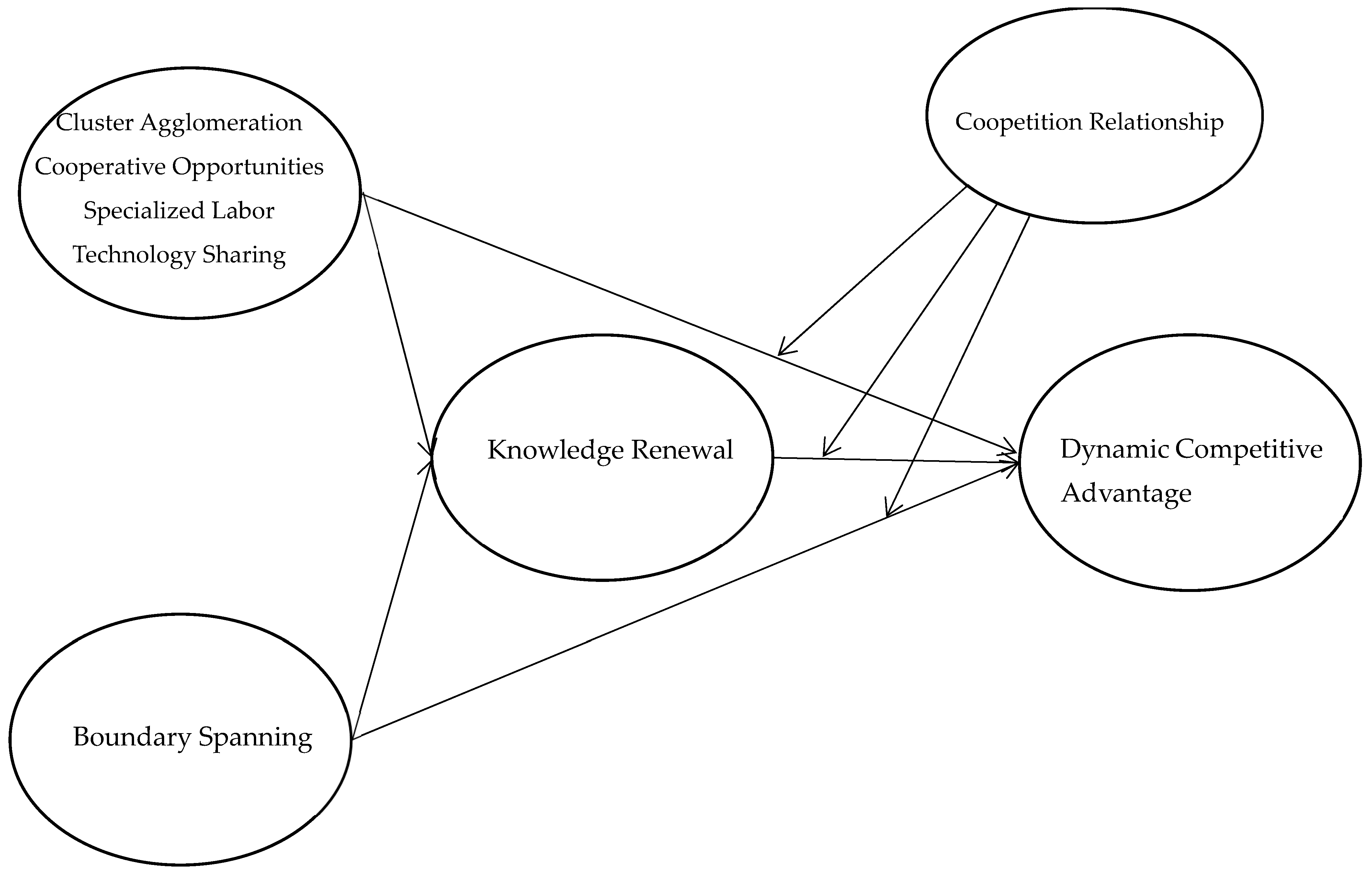

The primary focus of this study is the relationship among cluster agglomeration, boundary spanning, and the dynamic competitive advantage of firms within clusters. Based on the discussion above, the research framework of this study is presented in

Figure 1.