1. Introduction

Accurate voltage regulation in AC microgrids is essential for ensuring power quality, reliability, and system stability, especially under dynamic operating conditions and uncertain disturbance [

1]. The growing integration of distributed energy resources has positioned microgrids as key building blocks of modern sustainable energy systems. Their ability to operate in both grid-connected and islanded modes improves resilience, power quality, and flexibility in energy management [

2]. However, the proliferation of renewable sources such as solar and wind introduces significant operational challenges due to intermittency and the nonlinear behavior of power electronic converters. Among these challenges, voltage regulation in AC microgrids remains a critical problem, as it directly affects system stability, load sharing, and power quality under dynamic conditions [

3]. Ensuring stable voltage profiles in the presence of varying loads, transmission line faults, and parameter uncertainties demands control strategies capable of adapting to rapidly changing system dynamics [

4].

Traditional voltage control methods, including droop-based techniques, hierarchical control, and centralized model predictive control (MPC), have demonstrated satisfactory performance under nominal conditions [

4]. Nevertheless, these approaches often rely on precise analytical models of the inverter and network dynamics, which are difficult to obtain in practice and prone to degradation as system parameters evolve [

5,

6]. Furthermore, purely model-based MPC formulations can become computationally intensive and less effective in the presence of modeling errors or unmodeled nonlinearities. As microgrids increasingly operate in uncertain and data-rich environments, there is a growing interest in data-driven control and learning-based modeling techniques that can capture complex dynamics directly from measurements while maintaining interpretability and stability guarantees.

Recently, the Koopman operator framework has emerged as a powerful data-driven approach for representing nonlinear dynamical systems in a lifted linear space, allowing the use of a linear control strategy for systems with nonlinear behaviors [

7,

8,

9,

10]. It also enables the identification of the dynamics of nonlinear systems and to design linear predictors for analysis and control [

11,

12,

13]. The Extended Dynamic Mode Decomposition (EDMD) algorithm provides a practical numerical method to approximate the Koopman operator from measured data with explicit error bounds [

14,

15,

16,

17]. However, most Koopman-based identification and control methods are implemented offline, assuming stationary dynamics and fixed model parameters and using data obtained from detailed simulations or experimental environments [

18]. In practice, this can be infeasible, since system parameters often change during operation, rendering the system time-varying. In [

19], four algorithms are proposed to update the Koopman matrix online using system measurements: batch, windowed, minibatch, and online. The main objective is to update the state matrix while keeping the input and output matrices fixed, thereby reducing the computational cost per cycle. These algorithms were originally proposed for use with Dynamic Mode Decomposition (DMD) for simplicity, but depending on the chosen dictionary of functions, they can also be applied to EDMD. In each case, the state matrix is updated using the most recent pair of measurements, while the input and output matrices remain constant [

20]. In least-squares-based techniques, the characteristics of the collected data may lead to an ill-posed problem or to overfitting. One common form of regularization addresses this by adding a penalty term to the objective function, favoring solutions with smaller norms. Following this approach, the online algorithm for updating the state matrix is enhanced by incorporating a regularization term. Once the linear state-space representation of the system is obtained, it can be used to design an MPC [

11]. The resulting optimization problem features a convex cost function and linear constraints. To ensure convergence and stability of the algorithm, several conditions must be satisfied, such as the existence of the inverse of the data matrix when computing the Koopman operator via EDMD.

In Microgrid (MG) applications, where disturbances can abruptly alter system conditions, an online Koopman learning mechanism is essential to maintain accuracy and adaptivity. Particularly in islanded MGs, inverters interact by sharing power while maintaining voltage and frequency regulation [

5]. The interconnected nature of MGs makes it difficult to construct accurate system models, especially in the presence of transmission line changes, system faults, load variations, and parameter modifications. Consequently, online algorithms are well-suited for secondary and supervisory control, as they allow certain system parameters to be updated in real-time. Recently, several works have applied the Koopman operator and its data-driven framework to control design in the context of power systems and microgrids [

3,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. A large-signal linear model of an MG based on the Koopman operator is presented in [

22], where the selection of observables and control inputs is considered for voltage regulation using a linear quadratic integrator. Unlike the analytically derived Koopman-based large-signal model, the proposed approach is fully data-driven and updated in real time. An alternative approach is proposed in [

23,

26], where online data-driven secondary controllers based on an observer Kalman filter for voltage regulation in MGs are introduced, but with the same computational limitations as traditional DMD. Finally, secondary voltage control for MGs [

3] and for active distribution networks [

28], using a static Koopman-based approach, is presented.

In this paper, we propose an online data-driven voltage control scheme for AC microgrids that combines Koopman operator learning with MPC. The proposed framework transforms the nonlinear voltage regulation problem into a linear optimization problem by employing an EDMD-based linear predictor that captures the microgrid’s nonlinear inverter dynamics. The Koopman state matrix is updated in real-time using the most recent pair of measurements, ensuring the controller continuously adapts to system variations. To mitigate potential ill-conditioning during online updates, a regularization term is incorporated into the learning process, guaranteeing numerical stability. The updated Koopman model is then embedded into an MPC structure to compute the optimal control inputs that minimize voltage deviations and maintain system performance under load disturbances.

The main contribution of this paper lies in the development of an online data-driven voltage control framework for AC microgrids that combines Koopman operator theory with MPC to address nonlinear dynamics and operational uncertainties. Compared with traditional online DMD [

19], the proposed online regularized EDMD features three improvements. First, while online DMD relies on linear state measurements, our method uses a richer set of nonlinear observables, enabling more accurate representation of inverter and microgrid dynamics under large-signal and weak-grid conditions. Second, the inclusion of a regularization term in the recursive update mitigates numerical drift, noise amplification, and ill-conditioning issues that commonly degrade online DMD during persistent adaptation. Third, the proposed scheme maintains stable model updates even when excitation is low or operating points evolve slowly, whereas online DMD typically suffers from loss of prediction fidelity in these scenarios. As a result, the online regularized EDMD provides more reliable real-time prediction and control compatibility for inverter-dominated microgrids than traditional online DMD.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 describes the general features of microgrids and the associated control approaches.

Section 3 presents the online algorithm for determining the Koopman operator and its main features.

Section 4 details the design of the online Koopman controller along with the conditions for convergence and stability.

Section 5 discusses simulation scenarios under several cases. Finally,

Section 6 provides the conclusions.

2. Microgrid Voltage Control

The MG is defined as a cyber-physical system within a specific area that integrates generators, storage systems, and loads. Its proper operation requires a hierarchical control framework. The lower levels are associated with voltage and current regulation, synchronization with the utility grid, and the provision of virtual inertia. The first layer is typically implemented through droop control, which enables the parallel connection of sources while ensuring proper power-sharing. The second layer maintains voltage and frequency at their reference values [

29].

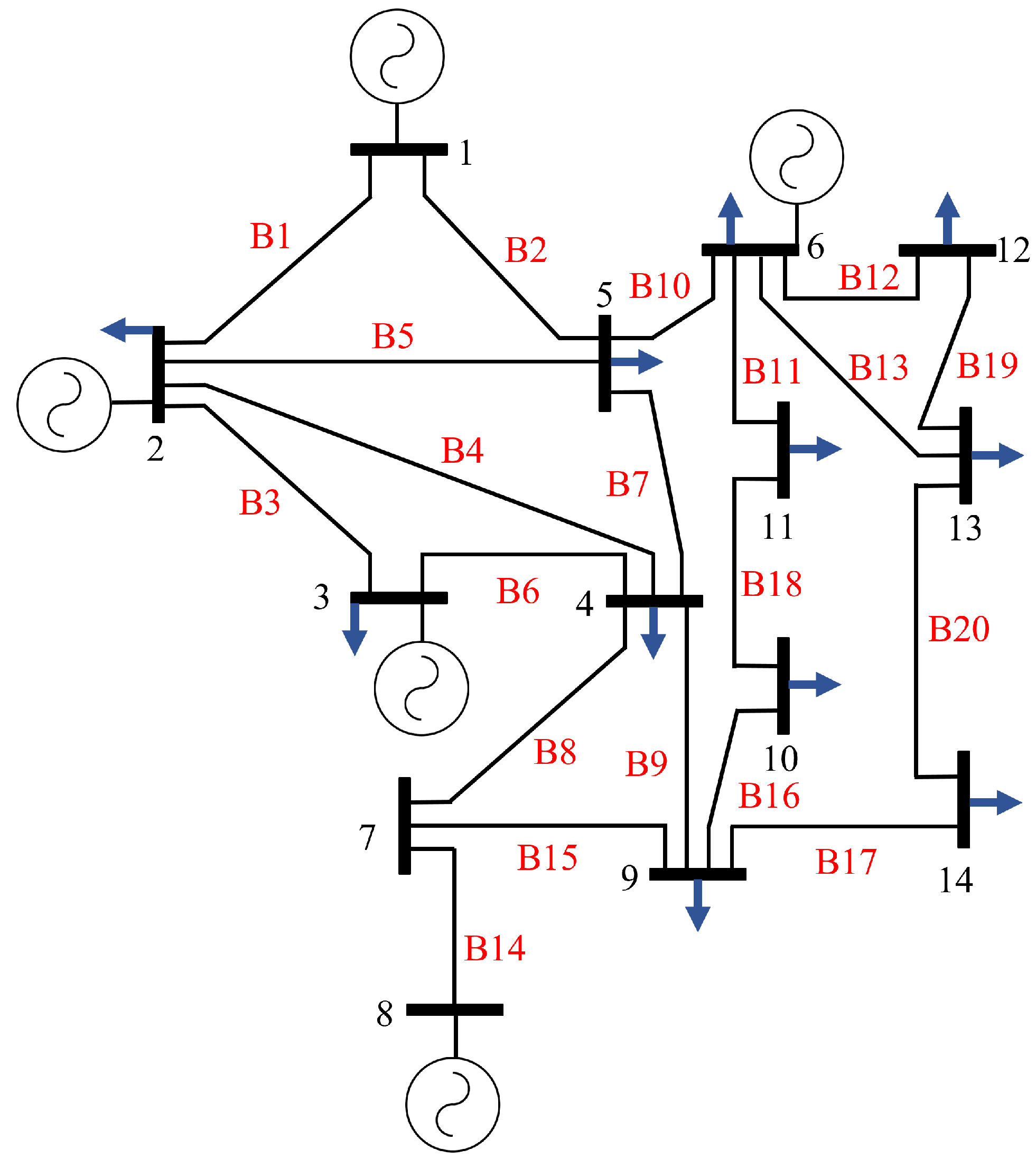

The general scheme of the AC MG is shown in

Figure 1. The blocks represent the hierarchical framework for primary, voltage, and current control, and also include the LC output filter. The power flow among inverters is governed by a set of nonlinear equations involving the phase differences between inverter voltages, the voltage magnitudes, and the transmission line impedances. The general expressions for active and reactive power are given by

where

denotes the self-admittance,

is the voltage magnitude, and

is the set of neighboring nodes of the

bus. Similarly,

is the voltage magnitude of the

node,

and

are the conductance and susceptance of the line connecting nodes

i and

k, respectively, and

is the phase angle difference between them.

The instantaneous power in (

1) and (

2) can be simplified by assuming a predominantly inductive transmission line, where

and

. These conditions can be achieved by introducing a feedback loop with a virtual impedance that emulates the effect of an inductance,

where

is proportional to the magnitude of the current measured at the inverter output. Although this behavior can be approximated by placing a large physical inductor at the inverter terminals, the use of virtual impedance allows emulating significantly larger inductance values without increasing the hardware size. Under the additional assumption of

, which guarantees a synchronized motion state, i.e., coordinated evolution of generator phase angles and frequencies [

30]. Under synchronized motion, all inverter-based distributed generators converge to a common steady-state synchronization frequency, and their electrical angles exhibit a uniform phase shift consistent with coherent network operation. This condition reflects the fundamental requirement that all sources supplying an islanded microgrid operate in synchronism to sustain voltage, maintain frequency, and preserve active and reactive power balance. Therefore, establishing synchronized motion is a prerequisite for ensuring feasible power exchange among units and guaranteeing stable power balance within the islanded microgrid.

Based on the previous assumptions, the power equations are simplified as follows

Then, the instantaneous reactive power becomes directly related to the voltage magnitude. One of the main advantages of this approach is the elimination of phase-angle dependence, thereby avoiding the inherent difficulty of measuring this variable.

By adopting the decoupling of active and reactive power implied by the lossless condition in the transmission lines, the reactive power in the network is controlled by adjusting the voltage set point of each inverter. The voltage droop equation is of the form

where

is the reference voltage,

is the droop coefficient for reactive power,

is the secondary control input, and

is the average reactive power.

The average reactive power is obtained by filtering the instantaneous reactive power from (

4).

The previous expression can be expressed as a differential equation as follows:

Equation (

8) is presented in discrete-time as follows

where

is the sampling time, and

is the secondary control input. Finally, replacing the reactive power (

4) we obtain

Therefore, the voltage at the node depends on the product of the voltage measured at that node and the voltages of its neighboring nodes, the square of the voltage at that node, and the susceptance between nodes. The voltage is governed by a nonlinear equation, which implies a non-convex optimization problem leading to several well-known limitations that hinder both analysis and real-time implementation. On the ond hand, nonconvexity introduces multiple local minima, meaning that optimization algorithms can converge to suboptimal solutions depending on the initial conditions. On the other hand, nonconvex optimization problems are generally computationally intractable for real-time control, as they require iterative nonlinear solvers that may not converge within practical time limits. In microgrid control, where decision horizons are small and control loops operate at millisecond scales, such computational delays can compromise system stability.

To overcome these challenges, this paper reformulates the nonlinear voltage regulation problem into a linear predictive control problem using the Koopman operator framework. By lifting the nonlinear microgrid dynamics into a higher-dimensional but linear space via online EDMD, the proposed approach preserves essential nonlinear behavior while enabling convex optimization in the lifted coordinates. This transformation eliminates the dependence on local linearization around equilibrium points, ensures a globally linear prediction model, and allows the use of efficient programming solvers within an MPC framework. Consequently, the controller achieves real-time performance, theoretical tractability, and robustness to modeling uncertainties, thereby addressing the main limitations of nonconvex formulations in microgrid voltage control. In the next section, the main theoretical foundations of the proposed online EDMD for MPC of microgrids is introduced.

3. Online Extended Dynamic Mode Decomposition

Dynamic Mode Decomposition has become a powerful technique for analyzing nonlinear systems. It is based on Arnoldi’s algorithm and is closely related to the Koopman operator. DMD provides a finite-dimensional approximation of the Koopman operator in matrix form. The most common DMD algorithm relies on Singular Value Decomposition (SVD), which also enables dimensionality reduction by retaining only the most significant singular values [

31]. Consider a dynamical discrete-time system of the form

where

is a nonlinear mapping, with

. A set of

M measurements from the system is collected and organized as

The exact DMD algorithm determines the system matrix by directly applying the pseudo-inverse of the data matrix

where † denotes the Moore–Penrose pseudo-inverse of

X. This problem can be formulated as the following minimization problem

where

denotes the Frobenius norm. DMD uses direct measurements from the system. This approach can be extended by employing a dictionary of basis functions, which may be nonlinear, known as EDMD. The dictionary of

functions is defined as

where each

spans the function space

, with

[

32]. Then, the set of measurements is evaluated using the following vector-valued function

where

. The following two matrices are defined as

and the approximate Koopman matrix

A is given by

where

G,

H, and

A. This data-driven approach can be employed to obtain a finite-dimensional Koopman approximation, where the nonlinear system is approximated by a linear one. The same method can be extended to include input terms, leading to the following representation

where the input vector is defined as

After establishing the data-driven formulation of DMD and EDMD, the next subsection presents their extension to an online framework that enables recursive real-time updates of the Koopman matrix.

3.1. Online EDMD Algorithm

As mentioned in the previous section, the voltage regulation problem in AC microgrids is inherently nonlinear due to the complex dynamics of power electronic inverters, the coupling between distributed generation units, and the nonlinear characteristics of loads and transmission lines. These limitations collectively restrict the scalability and robustness of conventional nonlinear voltage controllers. A key contribution of this paper is the introduction of an online EDMD algorithm that continuously updates the Koopman operator as new data become available. First, recall that the Koopman matrix is determined using DMD or EDMD by solving . This relation can be rearranged to establish the following assumption.

Assumption 1. is full rank with invertible.

The inverse matrix can be written as

The set of measurements is arranged using the last pair of samples from the system. At time

k, the measurements are given by

and the vector containing the last pair of arriving measurements is written as

then matrix

is updated as

at time

. Combining (

12) and (

20), the state matrix is written as

where

, and

are given by

where

are full rank, which guarantees the existence of the inverse of

. As the new measurements

and

arrive,

and

are set by adding an extra column as follows

Matrices

,

can be found as

Finally, the DMD matrix is given by

The previous update requires computing two matrix inverses, which is computationally demanding with complexity

. This inverse can be simplified by applying the Sherman–Morrison formula. The final expression for the matrix

is given by

with

Updating the matrix

requires

to be well-defined. The construction of the vector

requires a sufficient number of samples so that the inverse exists. The initial matrix

can be set as a random matrix, while

, where

is a large positive scalar [

19]. This online DMD algorithm can be extended to EDMD by replacing the direct measurements with those obtained from the dictionary of functions [

19].

3.2. Ridge (Tikhonov) Regularization Method

To avoid overfitting and to reduce the computational complexity, we introduce a regularization procedure for the online EDMD as follows. From data points

with perturbation norm bounded, the deterministic perturbation is defined as

where

is the uncertainty set. The uncertainty set can be defined as

where

is a restriction value for the 2-norm of

. The presence of uncertainty enlarges the residual term, whereas the approximation of the Koopman operator seeks to minimize it. Consider matrices

G and

H introduced in (

16). Hence, the problem can be cast as the following min–max optimization problem

where

,

A∈

, and

is the new perturbation term assumed to belong to

and perturbing the entries of matrix

G.

The above problem is usually non-convex and depends on the choice of dictionary functions. By selecting functions such as Gaussian, radial, and linear functions, the min–max optimization problem becomes convex. The equivalence between the robust optimization problem (

33) and the ridge regularization can be established, which implies that the following two optimization problems are equivalent

Solving the optimization problem to determine the state matrix using the EDMD algorithm requires computing an inverse matrix. However, the characteristics of the collected data may lead to ill-conditioned systems. To obtain a more reliable solution, it is necessary to use regularization methods, such as ridge regression (

34). Regularization favors solution matrices with smaller norms. As the parameter

c increases, the variance decreases, but the bias increases. Conversely, as

c decreases, the variance grows while the bias decreases. Thus, there is a trade-off between these two factors depending on the selection of

c [

33,

34]. In this way, we obtain the following optimization problem

whose solution is given by

with

Similarly, the next step is given by

Following the structure used in [

19], the updated matrix is given by

with

The regularization process can be applied to the identification of controlled models. For an input vector

, the state and input matrices can then be obtained by solving the following optimization problem

The previous problem can be extended to the lifted space using a set of basis functions. The state and input matrices in the lifted space,

and

, can be calculated with regularization by solving the following problem

In the next section, we present the proposed online EDMD applied to the voltage control problem of microgrids.

4. Online EDMD for Voltage Control of Microgrids

The algorithm presented in the previous section is applied to voltage regulation in a microgrid, following the model described in

Section 2. First, we define the dictionary of functions used to approximate the Koopman operator via EDMD. From this set of functions, we start by including the direct voltage measurements, their squared values, and the products of voltages between nodes

i and

j.

This dictionary of functions corresponds to a regulation problem in which the voltage measurements are required to reach the reference value. Alternative dictionaries allow the formulation of a tracking problem by including the error

in each function as follows

The nonlinear system described in (

9) is represented in the lifted space through the Koopman approximation matrices

,

, and

. For secondary control, the signal

is designed to correct voltage deviations while minimizing the control effort. MPC is a general framework for control and optimization that approaches the optimal solution by making decisions at each control step. MPC predicts future system behavior over a finite horizon based on a process model. In this case, the Koopman approximation provides a linear predictor for forecasting the future states of the nonlinear system. Based on this framework, the following MPC problem is formulated

It is worth noting that the proposed control law (

38) operates in a decentralized fashion, since each inverter relies exclusively on local information. Specifically, each inverter has access only to the voltage of the inverter with which it is physically interconnected. The convergence of the control algorithm (

38) depends on the structure of the cost function and the constraints imposed by the linear representation of the voltage. Some approaches for solving the optimization problem in distributed systems have been presented in [

3].

The optimization problem (

38) is implemented online using the updated state matrix from (

29) as

The online EDMD voltage control of MGs is characterized as follows. MGs are initialized with

,

, and

, which are obtained from preceding data.

is set as a scaled matrix

, with

. The update of the matrix is triggered by system perturbations or executed at every update period

, throughout this process,

B and

C are kept constant. To ensure reliable computation of the EDMD matrices, the data signals are filtered and saturated to remove values that might otherwise distort the estimation. The main steps os the online EDMD for voltage control of MGs is summarized in

Figure 2. The following assumptions are introduced to guarantee the conditions for the convergence of the algorithm (

Figure 2).

Assumption 2. The observables are assumed to be Lipschitz continuous.

Within the set of observables defined in (

37), the functions

and

are globally Lipschitz with constant

. Their squares,

and

, as well as the product

, are locally Lipschitz.

Assumption 3. Matrices defining the initial system dynamics, , , and , are provided.

Assumption 4. The pairs and are controllable and observable, respectively.

In Assumption 4, the controllability and observability conditions can be verified explicitly by assessing the controllability and observability properties of , , and .

Assumption 5. Each agent has access to real-time local measurements, which are used to update the system matrices. The state and input data, X and U, are drawn from a normal probability distribution.

Assumption 6. During each update, the matrices preserve their full-rank property. Moreover, the data used for updates are free of high-frequency components that might compromise the accuracy of the matrix computation.

We have introduced the main concepts and conditions for the online EDMD algorithm for voltage control of microgrids. In the following theorem, we present the main convergence result.

Theorem 1. The linear predictive-based controller in the lifted space with matrices , , and from (39), with the predictor updated through P at instants and satisfying Assumptions (3)–(6), guarantees asymptotic stability of the origin of the closed-loop lifted system. In particular, if the weighting matrices satisfy and , then the state and control sequences generated by the controller satisfy Proof. At each time instant

k, the control input

is obtained by solving the MPC optimization problem (

39), which minimizes the quadratic stage cost

subject to the lifted linear predictor

Let

be the optimal value function of the MPC problem given by

in other words,

at time

k. Since

and

, the stage cost

is positive definite with respect to the state and nonnegative with respect to the input. Therefore, there exist class-

functions

and

such that

which implies that

is positive definite and radially unbounded.

Using the standard shifting argument from MPC theory, the optimal value function satisfies the discrete-time Lyapunov inequality

Hence,

is a non-increasing sequence bounded from below by zero, and therefore it converges as

. Furthermore,

which implies

Since , the condition implies . Finally, the update through P preserves the stabilizing and observable properties of the closed-loop system, ensuring that the Lyapunov decrease property holds for all times. Consequently, the origin of the closed-loop lifted system is asymptotically stable, and both the state and control input converge to zero as . □

We have presented the main results for the online EDMD voltage control algorithm. This adaptive learning mechanism provides several distinct advantages such as real-time adaptability, reduced model dependency, improved numerical stability since a regularization term is introduced to prevent ill-posedness during online updates, ensuring smooth adaptation and bounded estimation errors, and enhanced control performance; by updating the predictive model online, the MPC layer can react promptly to new operating conditions, guaranteeing stable voltage regulation even under rapid transients. In the next section, we validate the proposed method by simulation in a 14-node IEEE model.

5. Simulation Results

In this section, we present the simulation results using an IEEE 14-node testbed MG shown in

Figure 3. This particular example of a small microgrid with five distributed generators is well aligned with the scale and operational requirements commonly found in Latin American rural electrification initiatives, where dispersed agricultural communities, indigenous settlements, and remote villages often lack reliable grid access or experience frequent service interruptions. In these environments, energy supply is typically built around a mix of renewable resources, such as solar photovoltaics and small wind units, complemented by battery storage and occasionally diesel backup, resulting in a generation mix that naturally reflects a five-unit configuration. At this scale, coordinated control becomes essential to maintain voltage and frequency stability under fluctuating loads, seasonal resource variability, and limited technical supervision. Furthermore, such a configuration captures the realities of infrastructure constraints in the region, including limited transmission capacity, decentralized usage patterns, and progressive expansion as communities grow, reflecting the operational and socio-technical conditions characteristic of rural electrification projects across Latin America. The entire system is implemented in Simulink®, while the optimization is carried out through YALMIP using the solver Gurobi. The parameters of the MG are provided in

Table 1. The transmission line parameters are the same used in the benchmark presented in [

3], and the load at each MG node is defined as 1 kW.

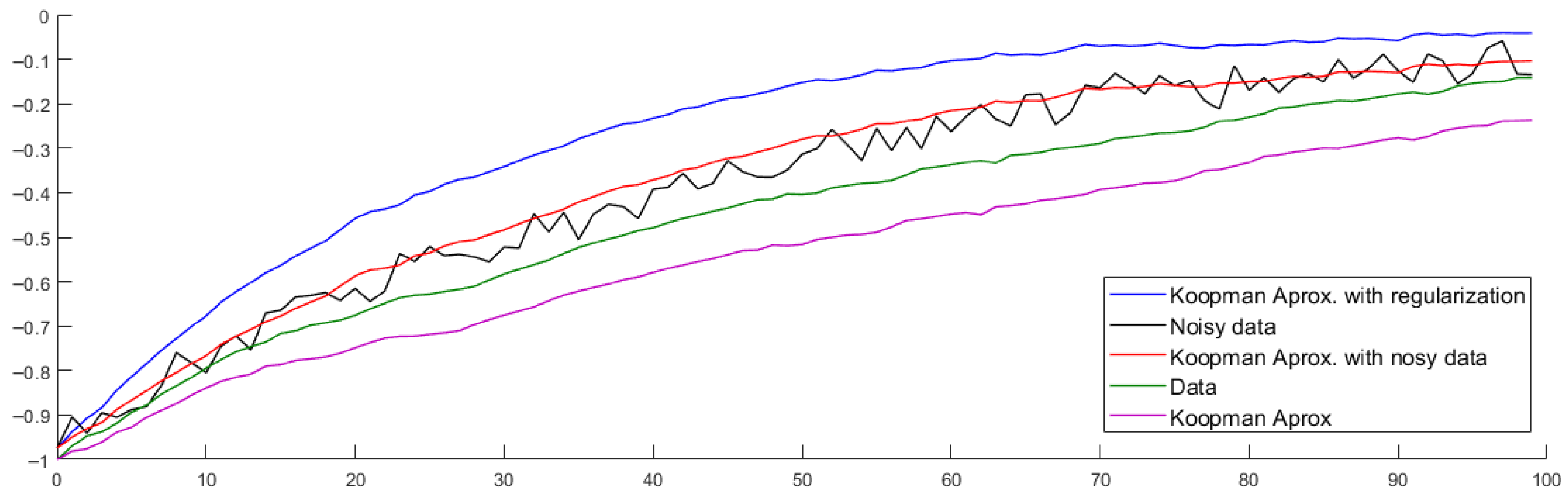

First, to illustrate a comparison between the different presented Koopman-based learning methods approximating the noisy data, the system output evolution over a period of 100 s is shown in

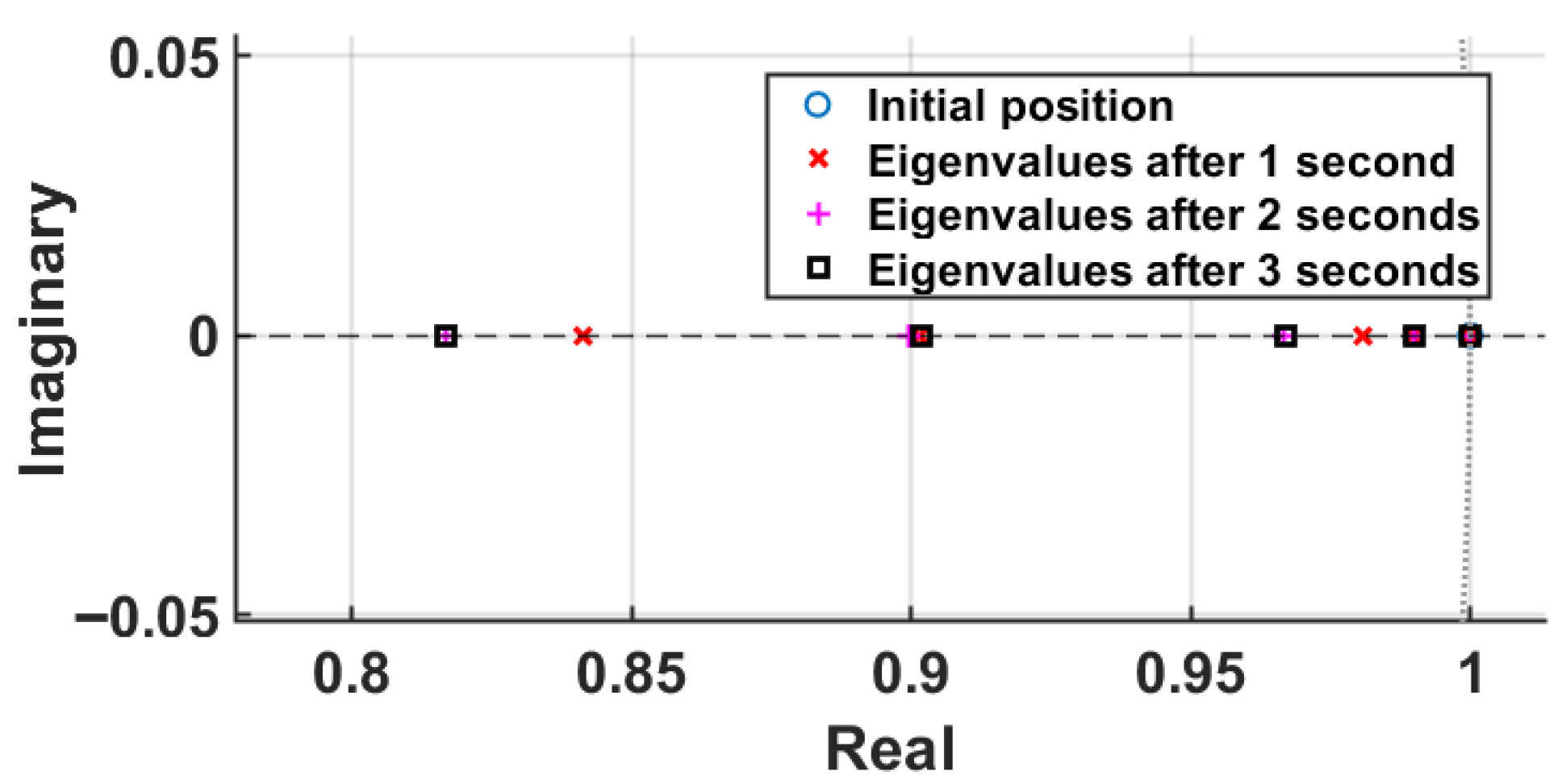

Figure 4. The original dataset is shown in green, while the same dataset with added noise appears in black. The corresponding approximations are presented as follows: the Koopman approximation in violet, the Koopman approximation with noisy data in red, and finally, the Koopman approximation with regularization is shown in blue. For the single-inverter model, the evolution of the eigenvalues is shown in

Figure 5. During the initial iterations, the eigenvalues deviate significantly from those computed with the standard EDMD. However, after a few iterations, they converge to similar values. Starting from an identity state matrix, the eigenvalues shift from left to right along the real axis.

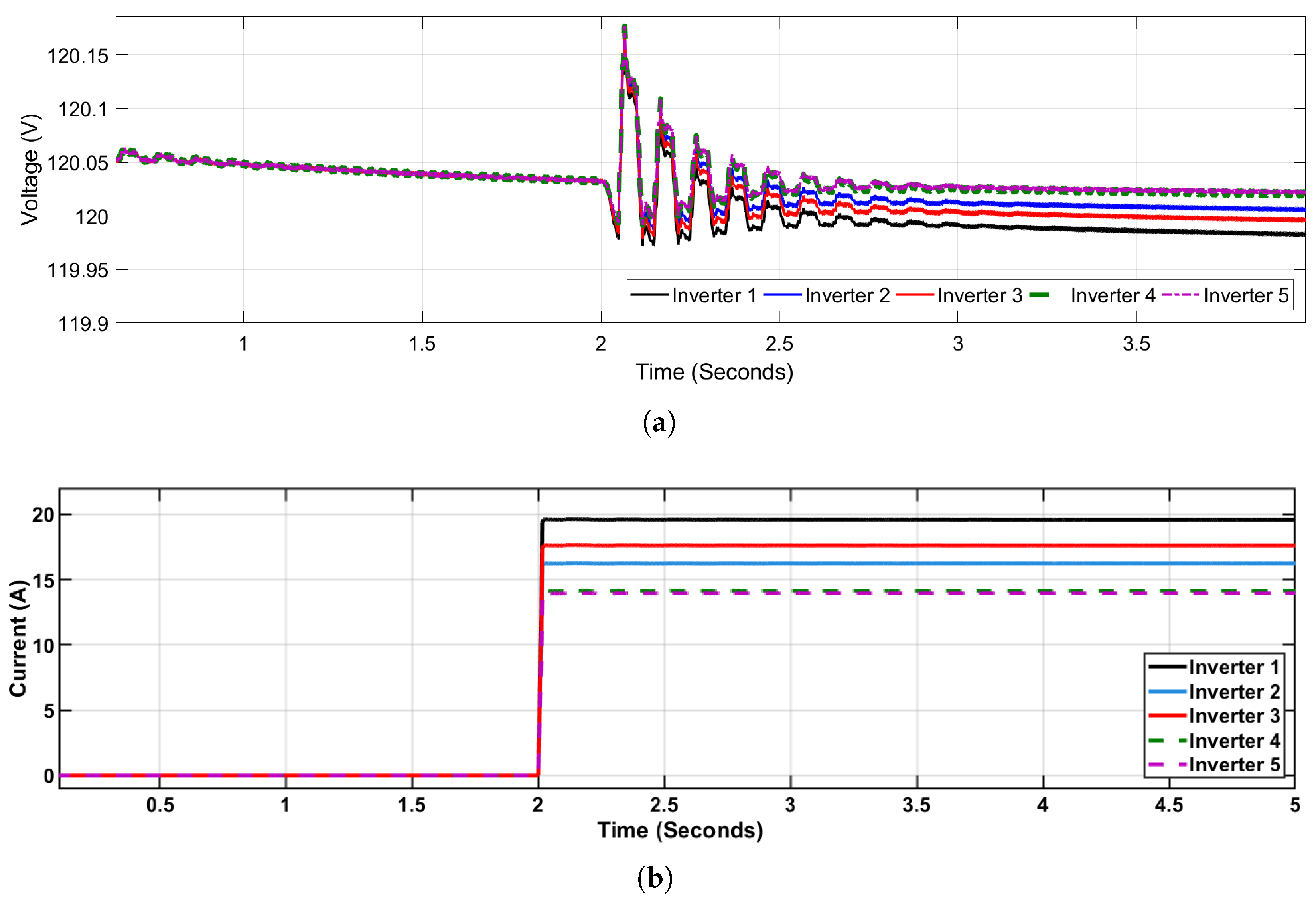

5.1. Load Changing Simulations

The MPC parameters are summarized in

Table 2. The MG begins operation with no loads connected at the initial instant. At

s, five loads of 2 kVar are connected to nodes 3, 5, 6, 9, and 14. Each inverter is initialized with a stored set of measurements large enough to ensure that the matrix

is invertible. In particular, each inverter retains 1000 samples of

and

values, while the initial state matrix is set to

. Matrices

and

are maintained unchanged, as obtained from a preceding iteration.

Figure 6a illustrates the output voltage of each inverter. Following the load change at

s, voltage oscillations occur at all inverter outputs. Then, voltages stabilize within one second and remain close to the reference value, with deviations below

V. The current at each inverter is shown in

Figure 6b, where inverter 1 supplies the larger quantity. It is observed that the current response has a stable steady state and a small overshoot with a rapid response. Similarly, the reactive power of each inverter is depicted in

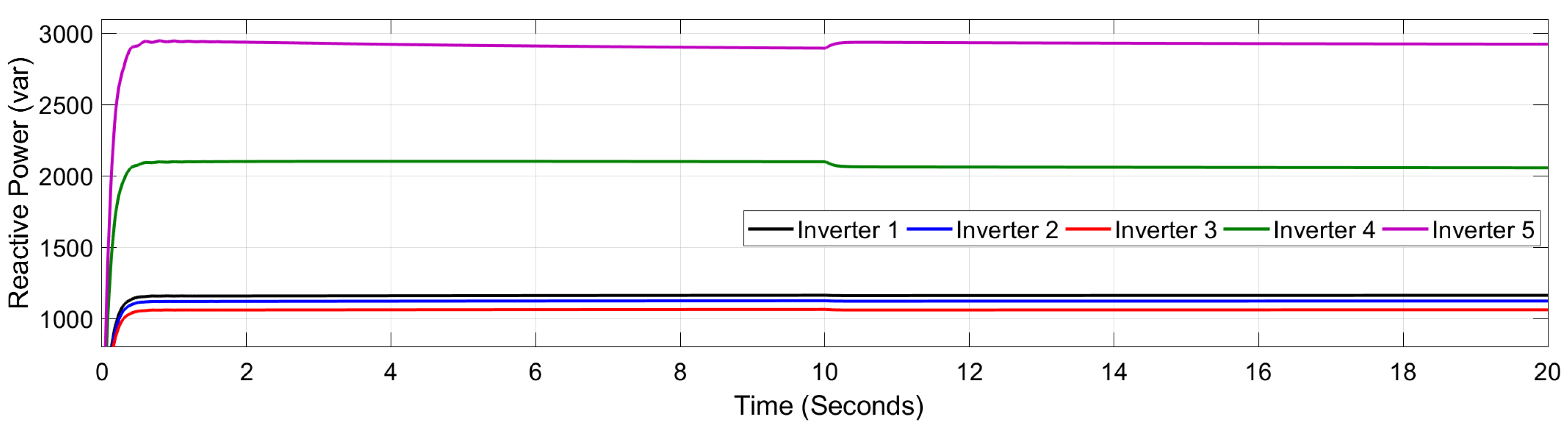

Figure 7, where inverters 4 and 5 exhibit similar values.

The load-changing simulations demonstrate the capability of the proposed online EDMD-based predictive controller to maintain voltage stability under dynamic operating conditions. When step variations in the load were introduced, the controller rapidly adjusted the inverter control inputs to compensate for the resulting voltage deviations. The voltage magnitude recovered to its nominal reference value within a short transient period, showing minimal overshoot and fast settling time. This behavior confirms the effectiveness of the Koopman-based linear predictor in capturing the nonlinear dynamics associated with load perturbations.

Compared with conventional model-based MPC or static linearized controllers, the proposed method exhibited superior adaptability. This improvement arises from the online update of the Koopman matrix, which continuously refines the lifted-state model based on recent input–output data. As the system experienced load changes, the online learning mechanism adjusted the internal model to reflect the updated operating point, resulting in more accurate predictions and smoother control actions. Furthermore, the inclusion of the regularization term in the EDMD update prevented numerical instability during abrupt load variations, ensuring consistent performance across all scenarios.

5.2. Transmission Line Failure Simulations

For transmission line simulation, the MG begins with 2kvar loads connected to the nodes 3, 5, 6, 9, and 14. Then, at

s, transmission line B18 is opened, and nodes 10 and 11 are disconnected. The transmission line failure simulations are conducted to evaluate the fault-tolerant capability and dynamic resilience of the proposed online EDMD-based Koopman–MPC controller. When a line outage occurred at

s, the microgrid experienced a sudden change in network topology and power flow distribution, resulting in transient voltage imbalances across the inverter buses, as shown in

Figure 8. Despite the abrupt disturbance, the controller promptly adapted its predictive model and restored the voltage profiles to their nominal values with minimal overshoot and oscillation.

Similarly, reactive power transient response at each inverter is shown in

Figure 9, where a small variation of the steady state is observed at

s. The simulation results show that the online learning feature of the EDMD algorithm played a crucial role in this performance. Immediately after the fault, the Koopman operator is updated using the latest measurement data, effectively capturing the new post-fault system dynamics. This real-time model adaptation allowed the MPC layer to recompute optimal control inputs that compensated for the altered coupling between distributed generators. As a result, the system maintained stable operation without requiring manual reconfiguration or prior fault information (see

Figure 9). The proposed online Koopman–MPC approach exhibited faster recovery times and improved voltage regulation accuracy under fault conditions (see

Figure 8). Moreover, the inclusion of the regularization term in the online EDMD update ensured numerical stability, preventing abrupt parameter shifts or ill-conditioned estimates during the transient. The smooth evolution of the Koopman model enabled consistent and stable control action even under severe network disturbances.

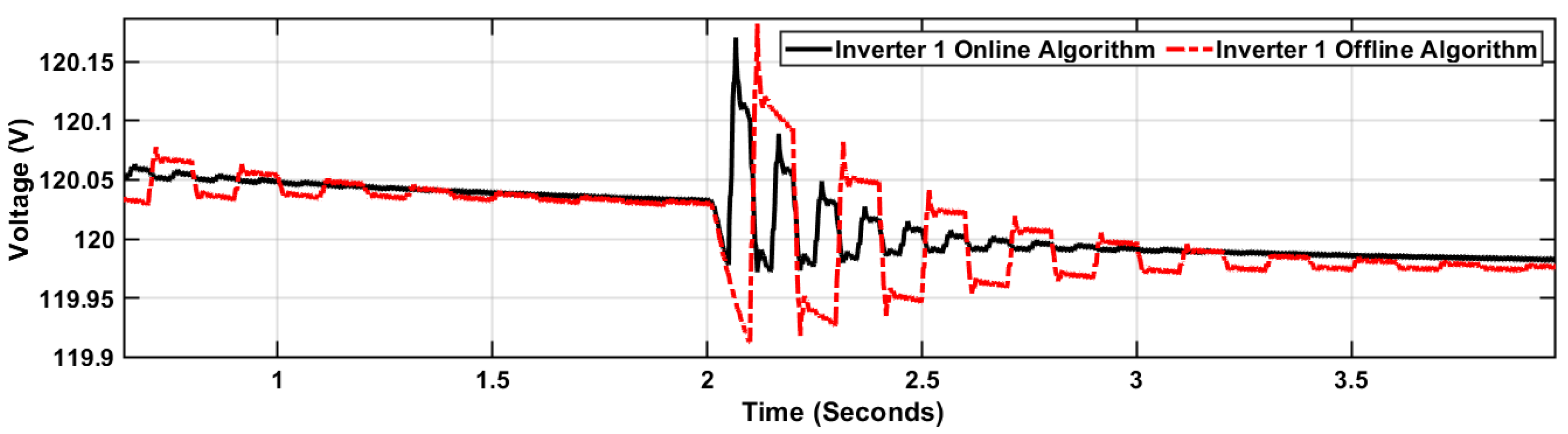

5.3. Comparison Between EDMD Algorithm and the Online EDMD Algorithm

In this subsection, a comparison is presented between a similar online EDMD-based algorithm that does not dynamically update the Koopman matrix and its offline counterpart. As in the previous load-changing scenario, the focus is placed on inverter one; the load is connected at

s. The output voltage of inverter one is shown in

Figure 10. It is clear that the voltage stabilization response is better for the online algorithm both at the system start at

s and when the load is connected at

s. The online algorithm reaches its steady-state value in less than one second, whereas the offline algorithm takes more than two seconds.