1. Introduction

In 2011, the European Union Commission agreed upon the much-needed change in transport policies and compiled a document called the White Paper on Transport. Essentially, it defines the future vision of the European Union mobility system by clearly identifying the desired goals, strategies, and means to achieve them. One primary goal is shifting from car-centered mobility development towards a sustainable and diverse mobility system by planning and encouraging public transport and other sustainable modes of transportation [

1]. In line with this strategic policy aimed at improving quality of life, many European cities are increasingly shifting from car-centered mobility to more integrated mobility systems. Oslo, Madrid, Helsinki, and Hamburg have recently announced their plans to become partly private car-free cities. Meanwhile, cities like Brussels, Copenhagen, Dublin, Milan, and Paris have implemented measures to reduce motorized traffic, such as car-free days, restricted parking spaces, improved public transport, cycling, and pedestrian infrastructures [

2,

3,

4].

Vilnius, the capital of Lithuania, is among the European cities pursuing such transition. In 2018, the city presented its 2030 Sustainable Mobility Plan, which sets out six strategic goals for advancing sustainable mobility systems. The plan analyses the current situation, clearly defines the city policies, and outlines an action plan for 2020 [

5]. A key component of this vision is micromobility, which focuses on the management and integration of non-motorized vehicles, such as bicycles or e-scooters [

6]. Since micromobility users are more vulnerable than cars or public transport passengers, it is crucial to ensure their safety by strategically planning infrastructure implementation into the existing mobility system [

7,

8,

9]. In this research, the planning and modelling of the micromobility engineering subsystem is considered for Central Vilnius.

The rapid growth of micromobility in cities around the world has created challenges for urban transportation systems, including the lack of adequate or outdated infrastructure, increasing numbers of accidents, inconsistent planning practices, and limited data-driven safety assessment. Additionally, with improvements in console and small non-motorized vehicle design, the growth of shared micromobility services has played a key role in this expansion, allowing users to access low-cost and eco-friendly transportation when needed and thus reducing their reliance on private car ownership [

10]. The extent of the growth of shared micromobility services in Lithuania can be seen through the use of shared e-scooters by Bolt, where users completed approximately 1.9 million kilometers using shared e-scooters in 2020. By 2022, travel distances across Bolt’s shared micromobility services had increased to approximately 7.4 million kilometers, representing an overall increase of around four times over three years [

11]. Including privately owned and other sharing platforms combined with these numbers, it is clear that micromobility has significantly increased within Lithuania.

However, the increased use of these vehicles has also affected the safety of roads. The percentage of crashes involving micromobility users increased from approximately 8.7% in 2018 to approximately 14% of all traffic accidents recorded in 2021. The increase is primarily responsible for this dramatic increase in accidents, which has grown substantially since 2018 [

12]. This escalation can be linked both to local driving habits and to infrastructure not yet adapted to the needs of micromobility users. Accident locations highlight this issue: 39% of collisions involving cyclists and 34% involving e-scooter riders occurred at intersections. These numbers underline the need to prioritize safety-oriented improvements in intersection design and other critical infrastructure elements [

12]. This statistic indicates that the current infrastructure needs to be improved, especially at the intersections.

The aforementioned Sustainable Mobility Plan defines clear goals and means to achieve the required change. By 2030, Vilnius aims to increase the number of trips using non-motorized transport to 15% of the total number of trips within the city. Improvement and development of the micromobility and pedestrian infrastructure is also a key objective [

5]. Additionally, the city stresses the importance of macro- and micro-level modelling in any proposed planning suggestions. The models should include the impact on private vehicles, public transport, micromobility traffic, and changes in environmental/noise pollution.

The analytical section of the Vilnius Sustainable Mobility Plan contains a chapter regarding non-motorized transport surveys from the years 2014 and 2016. The most frequently reported issues among users were traffic safety, lack of traffic organization on sidewalks, poor road quality, and insufficient bicycle path network. Additionally, the participants mentioned traffic and noise pollution, absence of driving culture, and discomfort due to the city’s geographical characteristics (steep hills, etc.). Furthermore, the aspects most likely to improve micromobility quality and encourage citizens to choose it over other types of transportation include developing a coherent cycling network, improving pavement quality, removing road obstacles, and enhancing overall safety.

Given the outlined context, it is evident that achieving Vilnius’ strategic goals for micromobility requires a substantial improvement in traffic safety, supported by evidence-based and context-sensitive planning interventions. Therefore, to effectively and systematically improve the safety of micromobility users, it is crucial to identify problematic points of infrastructure inside the network.

As of 2024, Vilnius—the capital and largest city of Lithuania—had a population of approximately 607 thousand residents and encompassed an area of about 401 square kilometers [

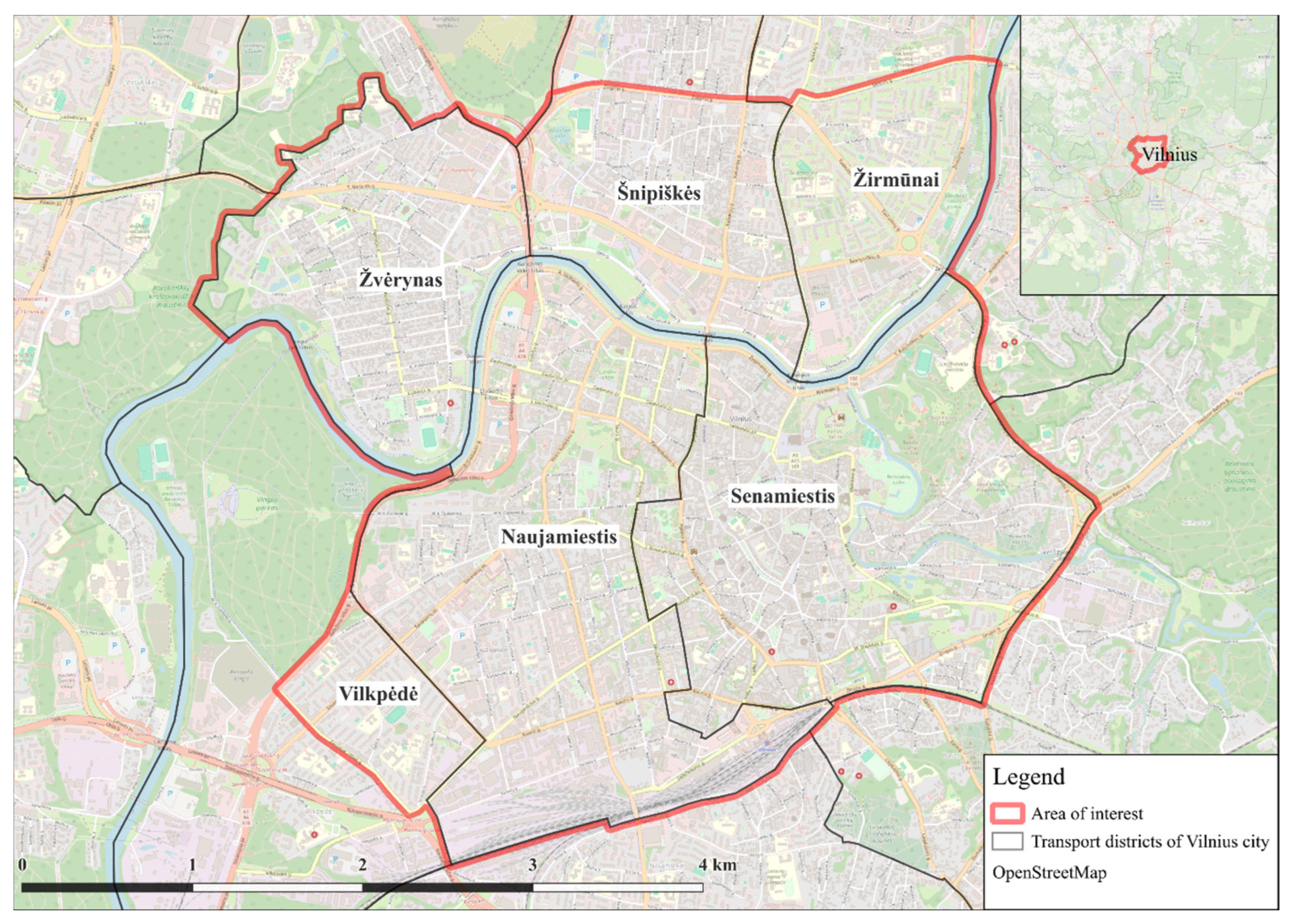

13]. To ensure consistency and account for time constraints, the case study was limited to the central part of Vilnius, which is referred to as the Vilnius case study (see

Figure 1 below).

The study area covers six administrative districts within the city of Vilnius: Žvėrynas, Naujamiestis, Senamiestis, the southern segments of Šnipiškės and Žirmūnai, as well as a minor section of Vilkpėdė. Notably, the Senamiestis district, which constitutes the historic center of Vilnius, is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site. The remaining selected districts, except Vilkpėdė, are considered a buffer zone of the historic city center [

14]. The UNESCO World Heritage designation of the Senamiestis district imposes specific restrictions on the design and planning of micromobility infrastructure, such as road pavement types like cobblestones. In essence, the UNESCO status necessitates a context-sensitive approach that balances mobility innovation and safety with cultural heritage preservation.

2. Literature Review

Micromobility’s rapid expansion in cities has not only altered travel behavior but also raised serious safety concerns. Bicycles, e-scooters, and e-bikes are lightweight and their riders are much more exposed than car drivers. Micromobility users drive everywhere, mixed in with traffic, weaving skillfully through sidewalks and narrow cycling lanes, each with their own unique movement patterns within the city. That requires a proactive approach that prioritizes prevention, drawing on multiple different sources.

This chapter presents a short and structured overview of recent research on micromobility safety, accident analysis methodologies, and the methodological contributions of the present study. It is organized into three main sections: (

Section 2.1) Micromobility Safety Issues, (

Section 2.2) Micromobility Accident Analysis Methodologies, and (

Section 2.3) Problem and Research Objectives.

2.1. Micromobility Safety Issues

Micromobility devices differ significantly from conventional motor vehicles in terms of mass, speed, and operational behavior, making them more vulnerable to roadside hazards and infrastructural inconsistencies [

15]. Recent studies identified intersections and shared pedestrian-cyclist zones as common places of micromobility-related crashes [

16,

17]. Naturally, some studies emphasize that most micromobility crashes occur within mixed-traffic conditions, particularly where road infrastructure fails to separate vulnerable users from motorized traffic streams. Lack of good visibility, proper infrastructure, and predictability in users contributes to unsafe conditions on the road. Research indicates that much of the cycling infrastructure is not designed to accommodate the variety of emerging micromobility vehicles. There are challenges related to surface quality, sensitivity to vibrations, awkward layouts, and the design of intersections [

8,

18,

19,

20]. Shared micromobility systems give rise to other issues, such as incorrect parking, unpredictable movement patterns, and low active usage of helmets [

21,

22]. These issues highlight the need for integrated approaches that combine infrastructure design, behavioral analysis, and data-driven evaluation.

2.2. Micromobility Accident Analysis Methodologies

Usually, researchers analyzing traffic safety often rely on crash records. They map out hazardous areas using various methods such as Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) or empirical Bayes techniques [

23,

24,

25]. While these tools are helpful for identifying general risk zones, they frequently overlook the smaller, more perilous spots—especially within intersections. Additionally, they do not consider the volume of traffic or capture near-miss incidents, which are crucial when dealing with low numbers of micromobility crashes.

To address these shortcomings, the field has increasingly adopted surrogate safety measures such as Time-to-Collision (TTC) and Post-Encroachment Time (PET). By utilizing video and drone footage, these metrics can identify conflicts in real time, revealing risky situations even in areas with few recorded crashes [

26,

27]. Furthermore, machine learning techniques—like Random Forests and Convolutional Neural Networks—have become adept at pinpointing factors that elevate crash risk and predicting the severity of injuries [

17,

20]. As previously indicated, the infrastructure also plays a vital role in the severity of injuries.

Currently, researchers are starting to merge various methods. Hybrid, data-driven approaches merge spatial hotspot detection with Floating Car Data (FCD), machine learning accident risk scores, and microsimulation tools like PTV Vissim with SSAM. This combination allows them to simulate the effect of planned changes on safety before any construction begins. While these tools certainly enhance analysis and provide planners with better insights, they are not flawless—issues like sampling bias in FCD, calibration challenges for surrogate measures, and gaps in crash reporting still limit our understanding [

28,

29,

30].

Consequently, recent studies advocate for a more integrated approach: combining hard crash data with conflict measures to create a more comprehensive picture of micromobility safety.

2.3. Problem and Research Objectives

Based on the problem context and literature review, the following problem statement emerges: The current traffic accident situation and surveys indicate the need to improve the safety of the micromobility infrastructure network. The research object concentrates on the practical micromobility engineering subsystem of Central Vilnius.

Research aim—to develop a methodological framework for identifying and analyzing safety issues at problematic intersections for micromobility users by combining macro-level analysis to identify high-risk locations across the urban network, and micro-level analysis to examine specific intersections.

Research objectives:

Develop a methodological framework and apply it to identify problematic intersections of the micromobility infrastructure.

Identify, analyze, and model a selected problematic intersection in terms of traffic safety and current infrastructural situation to propose planning suggestions that would improve the safety of micromobility users and overall level of service.

3. Materials and Methods

This chapter outlines the proposed methodological approach of this study.

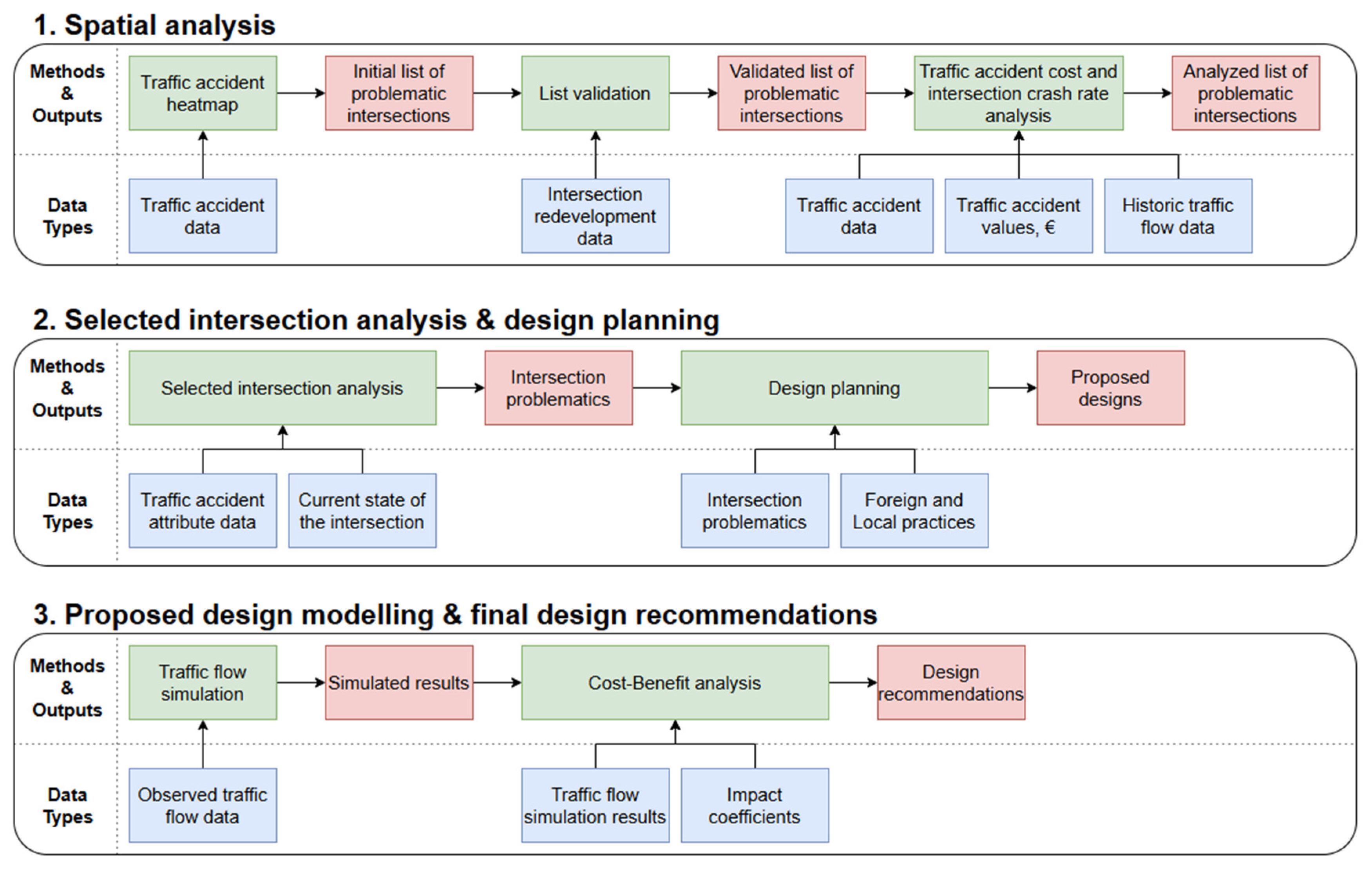

Figure 2 below illustrates the general approach, where round-edged squares indicate the main methodological phases, green squares—methods used, red squares—method outputs, and blue squares—the data required for each method.

The proposed methodology consists of three main phases: (1) Spatial analysis, (2) Selected intersection analysis and design planning, and (3) Proposed design modelling and final design recommendations.

Each phase is described more elaborately in the following subchapters:

Section 3.2.—Spatial analysis,

Section 3.3.—Selected intersection analysis and design planning, and

Section 3.4.—Proposed design modelling and final design recommendations.

3.1. Data

Three types of conceptual data are distinguished in the proposed methodology: (1) traffic accident data, (2) traffic flow data, and (3) Floating Car Data (FCD).

Publicly available traffic accident data is used to identify the most problematic intersections regarding traffic safety in the selected area of interest. The Lithuanian Government and Police began publishing this data in 2022. It is currently available for the period from 2013 to 2023 and can be accessed via the Data.Gov.Lt website [

31]. The traffic accident data contains all traffic accidents reported by the police with the location and other descriptive accident attributes.

Based on traffic accident statistics involving micromobility users in Lithuania [

12,

32], it is recommended to use at least four years of recent data for national-scale black spot analysis. The statistics also indicate an increase in traffic accidents involving micromobility users from roughly 8.7% to 14% during the period from 2018 to 2021. Additionally, the main e-scooter sharing platform in Lithuania began operating in Vilnius in the second half of 2019. Therefore, this study uses six years of traffic accident data (2018–2023), including 2018 as a reference year to capture conditions prior to the introduction of e-scooter sharing in Vilnius.

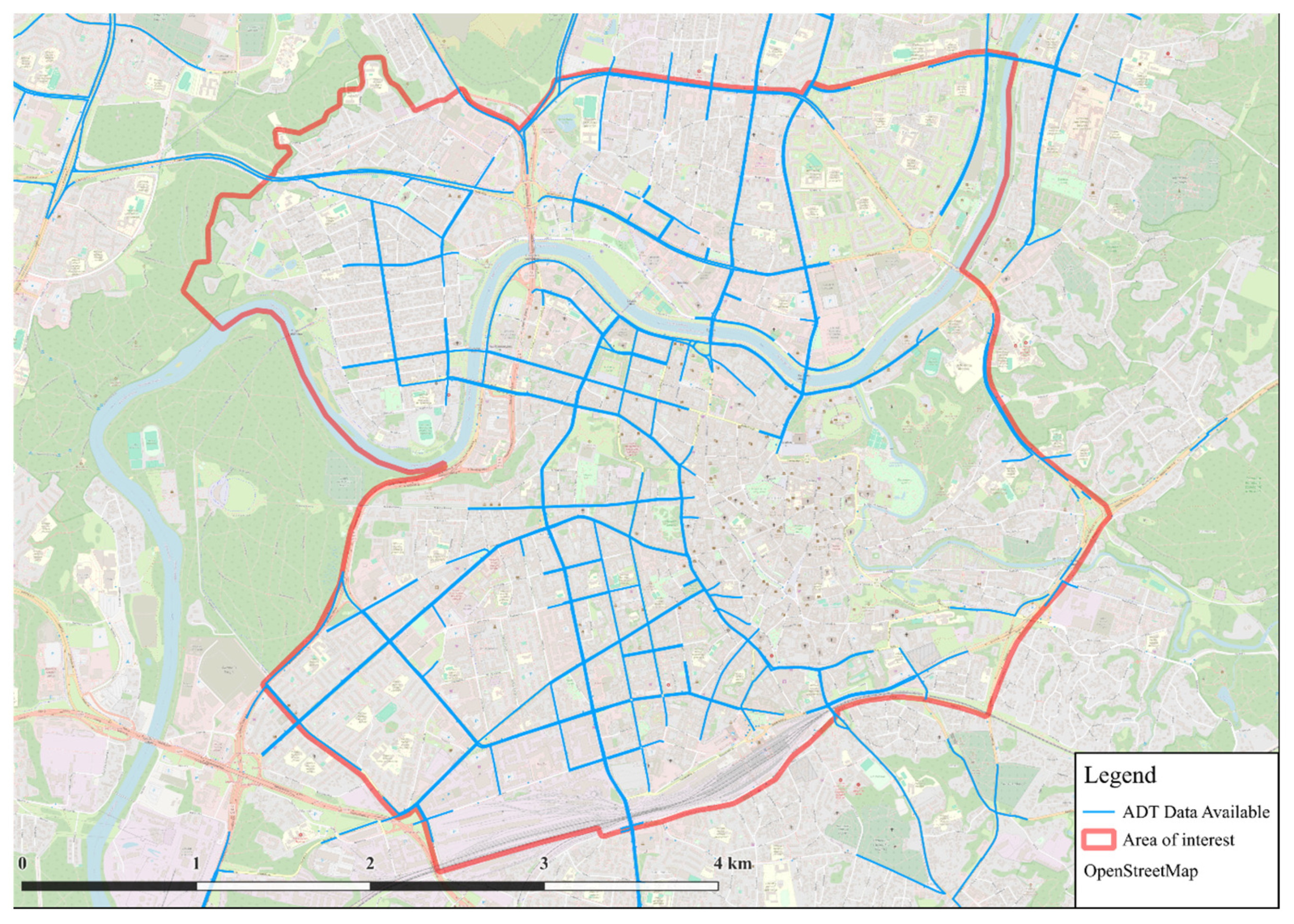

The traffic flow data for Vilnius are collected by the Vilnius traffic management and organization company JUDU, located in Vilnius, Lithuania (hereafter referred to as JUDU). The data are gathered via several types of traffic sensors at controlled intersections and are used for various traffic flow analysis, organization, and optimization tasks in Vilnius city [

33,

34]. Since the data are recorded directly at intersections, they are assumed to represent the most accurate traffic flow measurements available in Vilnius at the time of this research. However,

Figure 3 below demonstrates that the traffic flow data are only available for a portion of the road network inside the area of interest, excluding most streets without traffic lights or those with lower traffic volumes/road category. Therefore, to overcome the data gap, an alternative traffic flow data source, Floating Car Data (FCD), was chosen. In addition, based on the seasonality of Vilnius city, which indicates that the lowest traffic flows are recorded in January and August, while the highest traffic flows are observed in May and September, it was decided to use the average daily traffic of May for the calculation of intersection crash rates [

5].

Floating Car Data are spatiotemporal traffic flow data containing anonymized information about user trips, such as speed, origin, or destination. Typically, such data are sourced from various GPS-equipped vehicles and devices. However, due to the nature of this data, reliability issues may arise, and calibration against ground truth data is necessary [

35].

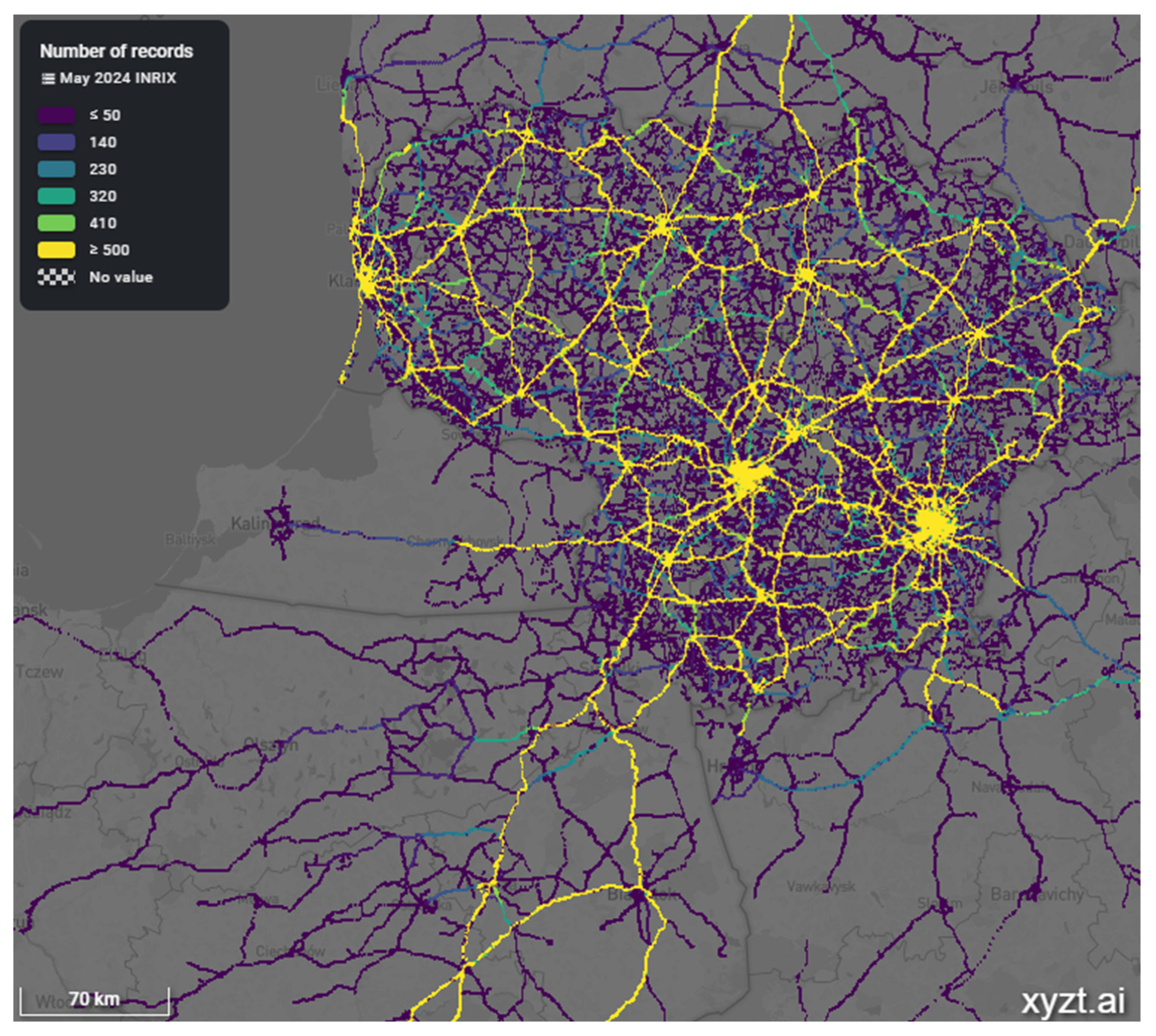

For this research, floating car data from INRIX [

36], one of the leading providers of data and insights about people’s movements around the world, is used. The available data were recorded in May 2024. They contain all observed trips that had contact with any part of Lithuanian territory.

Figure 4 below visualizes the trips observed by INRIX in May 2024 using the XYZT.ai visual analytics platform. Roughly 2.2 million trips had been recorded by INRIX that either went through, out of, into or started and ended inside Lithuania’s territory. The average travel time of one trip at the national level was around 1 h and 35 min, and the average observed speed was 72.6 km/h.

For the current analysis of the selected area of interest, around 177.9 thousand trips were detected in May 2024. The average trip travel time was 42 min and 16 s, and the average speed was 38.6 km/h.

Figure 5 below illustrates the trips observed throughout the selected area of interest, with the red line being the area of interest. Additionally, it is noticeable that FCD recorded by INRIX covers all road sections, unlike the JUDU traffic flow data.

3.2. Spatial Analysis

At this step, the focus is on pinpointing intersections that pose safety issues. This is performed by evaluating how often crashes occur, what types of incidents are recorded, and the corresponding crash rate for each intersection.

The obtained traffic accident data are available in JSON format, which includes only records classified as accidents with bicycles, effectively capturing all micromobility-related accidents. The filtered data are converted to a CSV file and imported into QGIS Desktop 3.34.3 software for further spatial analysis. Using embedded geographic coordinates for each traffic accident (latitude and longitude) under the EPSG:3346—LKS94 / Lithuania TM projection, the data are mapped as point layers. These are merged and spatially filtered using QGIS’s Merge and Intersect functions to isolate accidents that occur within the selected area, resulting in a final dataset ready for further examination. To continue the spatial analysis, the prepared traffic accident point layer is used to generate a traffic accident density, or heatmap. It allows for the identification of areas with a higher concentration of traffic accidents compared to other parts of the study area. To produce the heatmap, the study employed the Styled Heatmap (Kernel Density Estimation) feature from the QGIS Density Analysis Plugin [

37,

38]. This feature streamlines the standard QGIS kernel density estimation procedure, making heatmap generation more straightforward. In the function settings, the cell size was set to 50 × 50 m. This value is based on measurements between stop lines of opposing directions at randomly selected intersections using satellite imagery. This choice also aligns with Lithuanian guidelines, which recommend analyzing intersections within a range of 30 to 100 m, making 50 m a reasonable and compliant value [

39]. Additionally, the Uniform Kernel shape is used to generate a heatmap, which treats all points within the area equally. The following Equation (1) represents the Kernel Density Estimation using a Uniform Kernel Shape [

40,

41].

where

—estimated density at location (x, y); n—number of points; h—radius of influence; (x

i, y

i)—coordinates of the

i-th data point.

In the produced heatmap, the study area is divided into equally sized squares. Areas with a light color correspond to lower crash counts, whereas darker cells signal a higher density of incidents, making it easier to pinpoint intersections that might be problematic. The obtained heatmap of traffic accident density is then analyzed. For this research, an intersection was classified as problematic if it recorded three or more traffic accidents within the 6 year period. The identified intersections were then listed and ranked in descending order based on accident frequency.

Having performed the abovementioned steps, an initial list of problematic intersections is obtained. This list is then validated by considering recent developments of each intersection during the same period used for the traffic accident statistics. This validation is carried out through a review of relevant literature and online sources documenting recent developments of each intersection. If any developments are found, records of accidents occurring prior to the changes are excluded from the analysis. The intersection is then re-ranked based on the remaining number of traffic accidents or removed entirely if fewer than three traffic accidents remained. Once all intersections are reviewed, the validation step is considered complete.

The derived and validated list of problematic intersections is further analyzed based on traffic accident types. Three types of traffic accidents can be identified: (1) technical accidents, involving no reported injuries; (2) non-fatal injury accidents, involving injuries but no fatalities; and (3) fatal accidents, involving fatalities. Each type of traffic accident is assigned a monetary value, multiplied by the total number of observed traffic accidents of that type to determine the total traffic accident costs. The economic values are based on Lithuanian Legislation Act No. VE-23, referring to the Road Investment Guide [

42]. This Act identifies monetary values for each type of traffic accident (see

Table 1 below). Additionally, a coefficient of 1.54 was applied to adjust euro-denominated values from 2015 to 2024, based on Lithuania’s cumulative inflation rate over that period. For the remainder of this research, all monetary values were converted to reflect 2024 price levels.

Based on the number of different types of traffic accidents and their associated monetary costs, each intersection is ranked according to its total traffic accident costs. The intersection with the highest cost is assigned rank 1. This ranking highlights the most problematic intersections in terms of accident severity and monetary impact.

The final step of the spatial analysis phase is determining crash rates for each of the selected intersections. The Intersection Crash Rate (ICR) represents the ratio between the number of reported traffic accidents at an intersection and the number of vehicles passing through it during the same period. This metric allows fair comparison between intersections of different traffic volumes. For example, an intersection with higher traffic volume may experience more crashes, but exhibit a lower crash rate compared to a low-volume intersection. The following Formula (2) is used to determine the intersection crash rate [

43,

44].

where ICR is an intersection crash rate, N—number of recorded traffic accidents during the selected period, ADT—average daily traffic entering the intersection, n—number of years of the chosen data period.

The number of recorded traffic accidents—N—is derived from the earlier steps of spatial analysis. Meanwhile, the average daily traffic entering the intersection—ADT—is obtained from both JUDU and INRIX FCD datasets.

As noted earlier, to obtain as accurate average daily traffic data as possible from INRIX floating car data, the FCD must be scaled based on a derived scaling factor. To determine this factor, 10 randomly selected intersections within the study area, each with available average daily traffic flow data from JUDU, were analyzed. Intersections previously identified as problematic were excluded from this selection. For these 10 intersections, the FCD were processed using the XYZT.ai platform to extract the number of recorded trips during May 2024. The total trip count was then divided by 31 (the number of days in May) to calculate average daily traffic. Next, a scaling factor for FCD was determined using the LINEST function in Excel to determine the average daily traffic observed by JUDU and INRIX. This function calculates the statistics for a line based on the least squares method and returns the best-fit line for the selected data [

45].

Afterwards, the derived scaling factor was validated. For validation purposes, 10 new intersections with traffic flow values observed by JUDU were chosen, but this time, if possible, including intersections from the obtained list of problematic intersections. Again, the average daily traffic was determined from FCD for each selected intersection. The derived scaling factor was then applied to the average daily traffic of FCD to estimate average daily traffic flows. Next, the estimated ADT of FCD was validated with the observed ADT of JUDU using three metrics: Sample Standard Deviation, Mean Absolute Error, and R-squared.

The Sample Standard Deviation is calculated for the difference between observed and estimated ADT values and reflects the variability of these values around their mean. A lower spread indicates a more accurate estimation.

The Mean Absolute Error refers to the average magnitude of errors between estimated and observed values, not considering whether the difference between values is positive or negative. A lower absolute error indicates higher estimation accuracy.

The R-squared, or coefficient of determination, indicates how well a regression model explains the variance in the observed values. Values closer to 1 indicate more accurate estimations.

Finally, the determined and validated scaling factor is used together with the observed average daily traffic of floating car data, number of traffic accidents and Equation (2) to determine the traffic accident rates for each of the selected problematic intersections. The calculated intersection crash rates are then used to rank the intersections, with the highest crash rate assigned rank 1. This ranking identifies the most accident-prone intersection among those classified as problematic.

The spatial analysis is complete when a list of problematic intersections is derived and analyzed based on the traffic accident number, type, and intersection crash rate.

3.3. Selected Intersection Analysis and Design Planning

Phase 2 of the research methodology focuses on developing design suggestions to improve micromobility safety at the selected section. It begins with an analysis of the chosen intersection to determine its problematic aspects. These identified issues then inform the design and planning suggestions used in the final phase of the research.

To obtain a better understanding and identify the key issues of the selected intersection, it is analyzed in terms of its current urban and infrastructural context, recorded traffic accidents, and traffic flow data. The urban and infrastructural context is analyzed by visually examining the intersection, its characteristics, traffic organization, safety features already installed and the surrounding urban context [

46,

47,

48]. Based on the analysis, possible points of conflict at the intersection are identified.

To obtain a deeper understanding of the intersection’s issues, the traffic accident analysis is divided into two phases: analysis of traffic accidents involving micromobility users and traffic accidents involving pedestrians, cars, and motorcycles. The traffic accident data contain the main circumstances of the accidents. Among various traffic accident attributes—such as maximum allowed speed, intersection type, weather conditions, time of day—two key attributes can be distinguished: scheme 1 and scheme 2. The two schemes provide an abstract representing how the accident occurred. For example, scheme 1 may indicate that a car is turning right, while scheme 2 may indicate that a collision occurred during a left turn. Based on the available attribute description, it is possible to understand the potential causes of the accidents.

Next, traffic flow evaluation is conducted at the selected intersection. The analysis is performed by capturing 20 min aerial video footage using a drone. The selected weekday was one of Tuesday, Wednesday, or Thursday (depending on the availability at the time of the research) and did not fall on a public or school holiday. Additionally, the analysis was conducted during the evening peak hour, at 17:00, based on typical traffic patterns in Vilnius [

5,

34,

49]. The observed traffic flows are analyzed to identify any problems at the intersection during peak hours and to better understand traffic behavior.

Finally, the obtained insights about the current urban and infrastructural context, traffic accidents, observed traffic flow dynamics, and international and local practices of safe micromobility intersection designs are combined to propose planning suggestions improving micromobility safety. It is important to note that the proposed planning suggestions are not technical design solutions—they do not address aspects such as turn radius, the height of raised intersections, or similar elements.

3.4. Proposed Design Modelling and Final Design Recommendations

The final phase of the research focuses on selecting and proposing the most fitting design recommendation to improve micromobility safety. This objective is achieved by combining a cost–benefit analysis of the traffic flow modelling results with an objective justification of the proposed safety measures, since not all design suggestions can be evaluated through traffic flow modelling.

PTV Vissim is the selected software for traffic modelling. This software was developed by PTV Group Germany and is considered the state-of-the-art software for traffic flow modelling. It is used to simulate and reproduce traffic patterns of all road users on a microscopic scale with the help of science-based simulations and scenario management [

50,

51].

Using the PTV software, the current state of the intersection, together with proposed design suggestions, is modelled. Each scenario is simulated for 1 h of real-time traffic with peak traffic flows to understand the performance of the intersection when it is most occupied. Additionally, a warm-up time of 15 min is set to best represent real-world conditions. Any other intersection-specific modelling parameters and assumptions will be outlined in more detail once the intersection of interest is selected.

As mentioned in the problem context, Vilnius city stresses the importance of macro- and micro-level modelling in any proposed planning recommendations. The models should include private vehicles, public transport (if applicable), micromobility and pedestrian traffic, and changes in environmental/noise pollution. Therefore, the following criteria in

Table 2, together with corresponding monetary values, are employed to analyze the resulting traffic flow simulation metrics in a cost–benefit analysis. The total cost of the modelled alternative for one hour is calculated based on the modelled values and corresponding costs.

Impact coefficients are applied to evaluate the proposed alternatives and estimate potential benefits and remaining traffic accident costs. Impact coefficients are selected based on appropriate measure types from Trava LT 5.2 Measures and Models, retrieved from internal documentation provided by the Lithuanian Road Administration [

52]. For example, a coefficient of 0.56 is provided for developing pedestrian/bicycle paths separated from the main road. This coefficient shows that by implementing this measure, the impact of traffic accidents is reduced by 0.46 (benefit) while the costs are reduced to 56%. These coefficients are applied to the average yearly traffic accident costs, determined by dividing the calculated total traffic accident costs derived in the Spatial Analysis phase by 6 (total years of data used).

Finally, to further evaluate the possible long-term impact for each alternative, a cost–benefit analysis is conducted for a period of 20 years considering a 5% monetary discount rate [

42]. This analysis is performed for both the current intersection condition and all proposed alternatives.

The analysis includes yearly traffic accident costs and traffic flow simulation costs. The hourly traffic flow simulation costs are converted to annual costs under the simplifying assumption that these costs remain constant throughout the year. Annual traffic accident costs are then adjusted according to the relevant measures described in Trava LT 5.2 Measures and Models, and the benefits considered in this analysis are the resulting cost reduction in yearly traffic accident costs. It is important to note that the intersection (re)development costs are not evaluated.

4. Results

In this chapter, the main results of the methodological application to the Vilnius case study are presented. Similar to the methodology, this chapter is divided into 3 subchapters: (1) Spatial analysis, (2) Selected intersection analysis and design planning, and (3) Proposed design modelling and final design recommendations.

The spatial analysis subchapter—

Section 4.1.—starts with a generated heatmap for the Vilnius case study, which is used to identify problematic intersections. The list of such intersections is then validated and analyzed based on traffic accident count, types, and intersection crash rate.

The subsequent subchapter—

Section 4.2.—analyses one selected intersection in terms of urban and infrastructural context, micromobility, pedestrian, vehicle and motorcycle traffic accidents, and traffic flows to identify the main problems at the intersection. The identified issues are then combined with local and international micromobility practices to develop design recommendations aimed at improving micromobility safety.

In the final subchapter—

Section 4.3.—, the proposed design suggestions are modelled applying PTV Vissim software, and the resulting values are assessed through a cost–benefit analysis to identify the most suitable solution.

4.1. Spatial Analysis

4.1.1. Identification of Problematic Intersections

Following the steps outlined in the methodology, a traffic accident density map was generated (

Figure 6). The map highlighted problematic intersections within the study area, enabling a quicker analysis of the selected intersections and reducing the need to examine each intersection individually.

The selective analysis of the generated heatmap identified eight intersections with three or more recorded traffic accidents during the selected data period. The highest number of traffic accidents was 4, observed at each of the top 3 intersections. The remaining five contained three accidents per intersection. Selected intersections and the accompanying number of accidents can be found in

Table 3, and their respective locations in Vilnius can be found in

Figure 7, where labels represent the intersection number in the table.

Continuing the spatial analysis, validation of traffic accidents was performed. Each intersection was analyzed to identify any recent developments occurring during the same period as the traffic accident data.

The only intersection redeveloped during the analysis period was intersection 7, between Minties and Apkasų streets. The redevelopment was completed at the end of 2020 [

53]. Nevertheless, the crashes documented at this intersection all took place after the redesign—two in the latter half of 2021 and one in 2023. This confirms that the incidents occurred outside the redevelopment period, making them appropriate for inclusion in the spatial analysis.

Since no other intersections were redeveloped during the data period and the redeveloped one did not conflict with recorded traffic accidents, the list of problematic intersections is considered valid and remains as provided in

Table 3.

4.1.2. Traffic Accident Costs

To better understand which of the selected intersections was more problematic, each intersection was analyzed based on traffic accident types and their corresponding monetary values.

Table 4 below represents the corresponding number of different types of accidents for each intersection, the total traffic accident costs, and the corresponding ranking. Additionally,

Figure 8 visualizes the intersections based on total traffic accident costs, where labels indicate the number of intersections.

The traffic accident cost analysis revealed that based on the number of accident types and their associated monetary costs, intersection number 1 (between Gedimino Avenue, A. Jakšto and A. Stulginskio Streets) was the most problematic. A total of four traffic accidents were recorded at that intersection, all of which involved non-fatal injuries, resulting in an estimated total cost of €333,878.16. Meanwhile, the least problematic intersection was number 6, between Pieninės and Saltošnikių Streets, where a total of 3 traffic accidents were recorded—2 technical and 1 non-fatal injury traffic accident, resulting in a total cost of €88,767.14.

4.1.3. Intersection Crash Rate Analysis

In the final step of spatial analysis, the intersection crash rates were determined. This metric further evaluated an intersection’s safety by establishing how often crashes occurred relative to the traffic flow through that intersection. A higher crash rate indicated a more traffic accident-prone intersection.

As mentioned in the methodology, two data types are required to compute the intersection crash rate—the number of traffic accidents and average daily traffic (ADT) at an intersection over the selected data period. The number of traffic accidents was already known from the previous steps of spatial analysis. Meanwhile, the traffic counts observed by JUDU were only available for 3 of the 8 selected intersections: 1, 7 and 8 [

34]. Therefore, to overcome the missing traffic flow data gap, the INRIX floating car data (FCD) was used together with the publicly available JUDU data from May 2024.

Firstly, the scaling factor for floating car data was determined. To determine this factor for INRIX trip data, 10 random intersections with traffic flow values recorded by JUDU were selected (see

Figure 9 below). For each of the 10 selected intersections, the average daily traffic from both data sources—JUDU and INRIX—were determined. Then, the difference between the two data types was calculated and used in the linear regression function in Excel [

45] to determine the scaling factor. The observed values used for the calculation can be seen in

Table 5, where an average difference between FCD and JUDU-observed ADTs is 1.42%, and the resulting scaling factor of 72.33 is determined.

As in the previous step, 10 intersections within the study area with FCD and JUDU traffic count data were selected to validate the scaling factor. Three of these 10 intersections (1, 7, and 8 from

Table 4) were selected from the problematic intersections identified in

Section 4.1.2.

For each intersection, the observed FCD values were scaled using the previously determined scaling factor of 72.33. The scaled values were then compared using the May ADT recorded by JUDU for a specific intersection. The resulting validation values can be found in

Table 6, where the average difference between scaled and observed values is −4.8%.

To further assess the validity of the scaling factor, three metrics were calculated for the intersections selected for validation (

Table 7): Sample Standard Deviation, Mean Absolute Error and R-squared. These metrics were determined using the observed and scaled traffic flow values. Sample Standard Deviation indicated that the average deviation from the mean was 2920.55 or 14.58%. The Mean Absolute Error was 2391.16 traffic flow values or 12.24%. Meanwhile, the R-squared metric suggested that 87% of the scaled values represented the traffic flows recorded by JUDU. The determined scaling factor with a high R-squared value is reasonable for future analysis. Sample Standard Deviation and Mean Absolute Error values were less than 15%, suggesting consistent and relatively accurate scaled traffic flows [

54].

Finally, the recorded traffic accidents, the INRIX data of May 2024, and the calculated scaling factor were used to estimate crash rates at each of the selected problematic intersections using Equation (2).

Table 8 below shows the final calculated intersection crash rates with corresponding ranks, where rank 1 has the highest intersection crash rate and rank 8—the lowest.

The table below shows that intersection no. 2 had the highest estimated intersection crash rate of 0.151, while the lowest crash rate was calculated for intersection no. 8—0.044. On average, the estimated crash rate was 0.110 for all 8 of the selected problematic intersections.

To summarize, the spatial analysis revealed 8 problematic intersections. Three of them recorded 4 traffic accidents each, while the remaining five recorded three accidents each. Further analysis of the eight problematic intersections showed that in terms of traffic accident costs, the most problematic intersection was number 1, between Gedimino Avenue, A. Jakšto and A. Stulginskio Streets, with the corresponding total cost of €333,878.2. Meanwhile, the intersection crash rate analysis showed that the most accident-prone intersection was number 2, between Gedimino Avenue, Vilniaus, and Jogailos Streets, with a crash rate of 0.151.

4.2. Selected Intersection Analysis and Design Planning

After careful consideration, intersection No. 6 (Pieninės St.–Saltoniškių St.) was selected for a more detailed analysis due to its high crash rate and many conflict spots between cars, pedestrians, and micromobility users. Even with safety measures, such as raised intersections, refuge islands, and dedicated bicycle paths, this area still exhibited issues related to user behavior and accident patterns. Additionally, its complex geometry and mixed traffic flows make it an ideal candidate for testing the proposed methodological framework, ensuring that the analysis addresses both quantitative risk and practical design challenges. The selected intersection’s specifics were analyzed to understand current problematics better and propose design suggestions aimed at improving micromobility safety.

The following subchapters include the urban and infrastructural context of the intersection, as well as an analysis of recorded traffic accidents and observed traffic flow.

4.2.1. Urban and Infrastructural Context

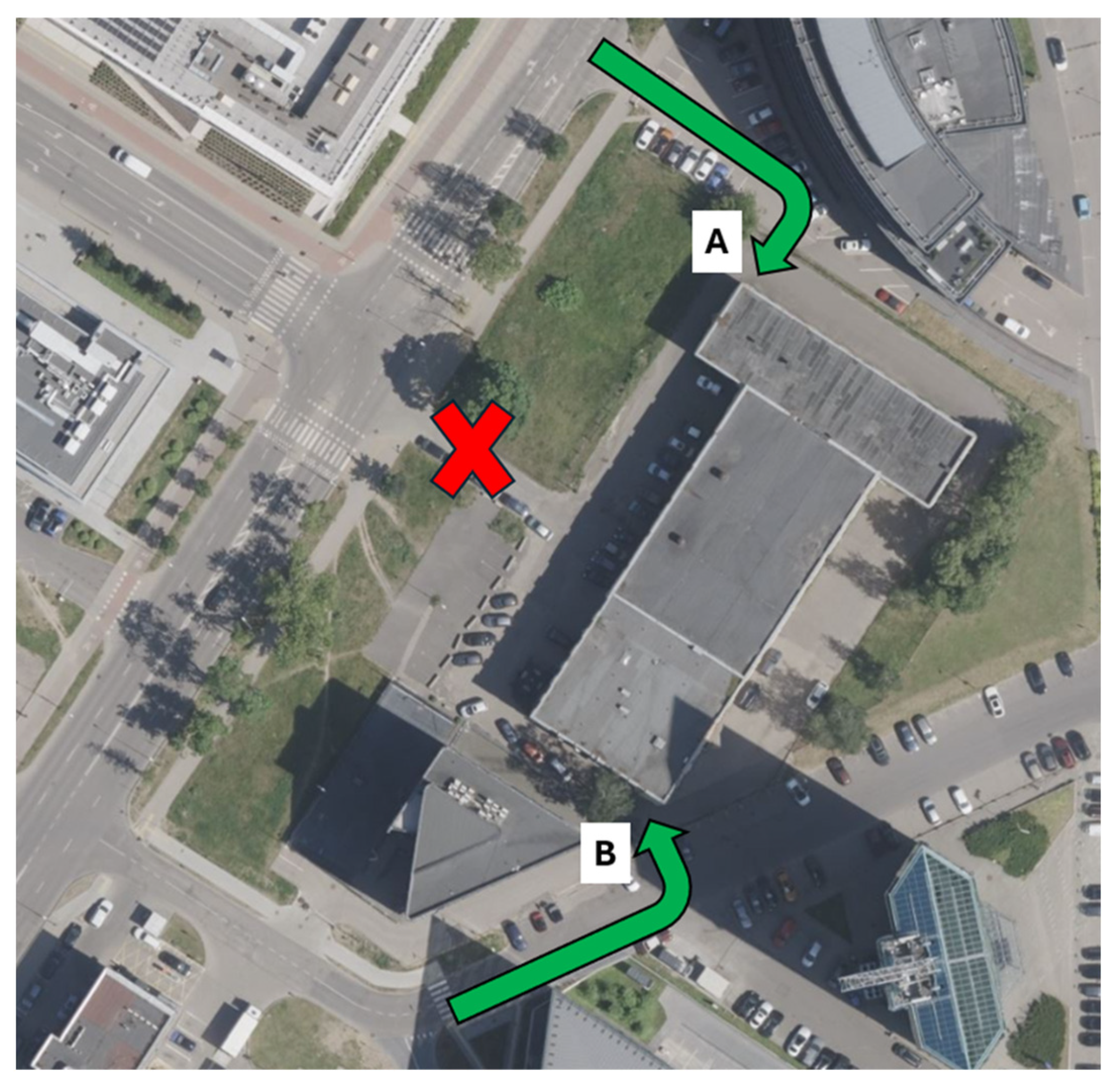

The selected intersection is in the Žirmūnai district, northwest of the study area. It is set in a mixed-use urban environment of leisure, office, and other institutional buildings. It also serves as a bypass road between two important Vilnius arteries—Ukmergės Street (A2 highway) and T. Narbuto Street (see

Figure 10 below).

It is a four-way unregulated intersection between Saltoniškių and Pieninės streets and a driveway (See

Figure 11 below).

The driveway connects to a parking lot for around 50 vehicles. Meanwhile, Pieninės Street connects as a side road to Saltoniškių Street with two designated right turn lanes, one designated left turn lane, and one lane into Pieninės Street. Coming from Ukmergės Street, Saltoniškių Street connects into the intersection with two lanes—one designated straight lane and one straight/right turn lane towards Pieninės Street. There is only one lane towards Ukmergės Street.

Furthermore, the remaining section of Saltoniškių Street toward T. Narbuto Street has a 2 + 2 lane configuration. Approaching the intersection of interest, one lane is designated for a left turn and one straight/right turn to the driveway. On all sides of the intersection, there is a pedestrian walkway. On the left side of Saltoniškių and the right side of Pieninės streets, there is a two-way dedicated bicycle path, separated from the overall context of the intersection with a red color.

It is a raised intersection with a directional lighting system and three pedestrian/cyclist crossings (two on Saltošnikių Street and one on Pieninės Street). Currently, the intersection road markings are visible at around 90%, but the clear signs for all intersection users compensate for the missing 10% of road markings. The different driving directions on Saltoniškių Street are separated by a safety island covering both pedestrians and cyclist crosswalks.

Overall, the selected intersection has a lot of safety measures, such as a raised intersection principle to reduce the speed of vehicles, safety islands separating driving direction at crosswalks, directional lighting, etc. Nevertheless, this being an unregulated intersection results in many points of conflict between all three types of road users—pedestrians, micromobility users, and vehicles. Therefore, to improve the safety of the intersection, conflicts between different road users should be minimized or eliminated, especially the ones involving traffic accidents discussed in the following subchapter.

4.2.2. Traffic Accident Analysis

This subchapter is divided into two main parts: (1) traffic accidents involving micromobility users; and (2) all other traffic accidents recorded during the data period. All recorded traffic accidents were analyzed based on the attributes provided in the data to identify possible problems at the intersection.

Traffic Accidents Involving Micromobility Users

The spatial analysis revealed that three traffic accidents involving micromobility users were recorded during the 6 year data period (see

Figure 12 below). Two traffic accidents were of the technical type, and one resulted in non-fatal injury. Based on the locations of the data points and their associated attributes, all three accidents can be identified as having occurred on the crosswalk/bicycle crossing between Pieninės and Saltoniškių streets. This is likely due to the fact that the main micromobility traffic flows through that crossing, where the two-way bicycle path on that side of Saltoniškių Street intersects with the two-way bicycle path on the right side of Pieninės Street.

At the intersection, two traffic accidents were recorded around the evening peak hour and one in midday. One traffic accident was recorded in September of 2019 around 18 o’clock, another traffic accident was recorded in July of 2020 around 14 o’clock, and the third traffic accident was recorded in April of 2023 around 16 o’clock.

All three traffic accidents happened during the day and in dry weather conditions. As no accidents were recorded during the night or in wet weather conditions, it can be assumed that the intersection is indeed well-lit and has a good geometry that does not affect user safety during wet weather conditions.

More detailed analysis of traffic accidents showed that one traffic accident occurred between a micromobility user and a pedestrian at the crosswalk. This traffic accident indicates the need to separate pedestrians and micromobility users in a better manner.

Furthermore, the remaining two accidents occurred between a micromobility user and a vehicle. One traffic accident, which resulted in an injury, occurred when a vehicle turned right, and the other when a vehicle was turning left (or making a U-turn). Both vehicles involved in the accidents were turning from Pieninės Street. These two traffic accidents indicate a significant need to eliminate the conflict between vehicles and micromobility users at the bicycle crossing located on Pieninės Street.

Traffic Accidents Involving Pedestrians, Cars, and Motorcycles

To identify other traffic accidents recorded at the intersection, the same traffic accident datasets were used, this time filtered to include all accidents except those involving micromobility users. During 6 years, four accidents were recorded at the intersection: 1 involved a pedestrian and three occurred between two vehicles.

The accident involving a pedestrian was recorded in mid-December of 2021. It happened during the evening rush hour, around 17:30, at one of the two crosswalks on Saltoniškių Street. At the time of the accident, it was already dark outside, which could indicate poor visibility for pedestrians and drivers. However, the police report indicated that the intersection lights were working. In the infrastructural context, it was noted that the intersection was well-lit with directional lighting. Therefore, it can be assumed that poor visibility was not the main factor contributing to this traffic accident. In addition, the intersection pavement was wet, but there was no rain at the time of the accident. Considering the infrastructural context—specifically the raised intersection—it can be assumed that speed and wet pavement conditions did not have significant impact on the accident. Finally, Scheme-1 and Scheme-2 attributes in the Police dataset [

31] indicated that the accident occurred when a vehicle turned right and the pedestrian was already on the crosswalk. Since it was unclear how far into the street the pedestrian had already entered, it was feasible that the accident occurred right after the first step. There are only two possible right turns intersecting crosswalks at Saltoniškių Street: towards Pieninės Street and into the driveway. Regarding the right turn towards Pieninės Street, no potential obstacles are blocking the view for vehicles. However, for right-turn movements into the driveway, a tree located approximately 10 m before the midpoint of the crosswalk may partially obstruct drivers’ visibility. Nonetheless, this traffic accident stresses the necessity to minimize or potentially eliminate the point of conflict between vehicles turning right and pedestrians/micromobility users using the crosswalk.

The remaining three accidents between two vehicles happened in 2019 (2) and 2023 (1). All three accidents occurred after the evening rush hour, indicating that the intersection was not particularly busy at that time. No precipitation was recorded at the time of all three traffic accidents, but the pavement conditions varied, including snowy, wet, and dry surfaces. Again, considering that the intersection is raised, it is unlikely that the pavement conditions had influenced the outcomes for any of the three traffic accidents. The same applies for lighting—the intersection is well-lit, and the lights were on when the two traffic accidents occurred in the dark.

Two of the three mentioned vehicle accidents took place when both vehicles were turning right. Considering the geometry of the intersection, the most plausible explanation for the two accidents is that they occurred during right-turn movements from Pieninės Street to Saltoniškių Street, resulting in a sideswipe. This type of crash can have various causes, such as drivers failing to stay within designated turn lanes, misjudging spacing, having unclear road markings, or inadequate lane width. Consequently, these two accidents provide limited insight into the overall safety of the intersection.

The final traffic accident occurred when a vehicle was turning left (or making a U-turn) from Saltoniškių Street toward Pieninės Street or the driveway, and the other vehicle was driving straight. This traffic accident indicates a need to minimize or eliminate conflict between straight-driving vehicles and those executing left-turn movements.

4.2.3. Traffic Flow Analysis

As outlined in the methodology, the traffic flow analysis for Vilnius was conducted on 1 April 2025, at 17:00. A 20 min segment of the evening rush hour was captured from an aerial perspective using a drone.

During the 20 min traffic flow observation, 391 lightweight vehicles and motorcycles, 214 pedestrians, and 39 micromobility users were observed. Assuming the traffic flow remained constant over the remainder of the hour, the estimated rush-hour traffic intensity at the selected intersection was 1173 lightweight vehicles and motorcycles, 642 pedestrians, and 117 micromobility users.

The highest traffic flow intensity for vehicles and motorcycles was observed on Pieninės Street—164 in total. Of these, 128 lightweight vehicles and motorcycles turned right toward T. Narbuto Street. For both pedestrians and micromobility users, the highest traffic flow was observed on the right side of Pieninės Street—91 and 14, respectively. Of these, 69 pedestrians went towards T. Narbuto Street, and 9 micromobility users travelled toward Ukmergės street via the dedicated bicycle path.

Regarding the observed traffic flow and organization at the intersection during the analyzed rush hour, it could be described as highly unstructured. First, congestion formed at the beginning of the observation period and persisted throughout due to the traffic light at T. Narbuto Street. This queueing caused drivers to disregard priority rules, often resulting in stopped vehicles blocking the intersection and occupying all three crosswalks and bicycle crossings (see

Figure 13 below).

Such behavior reduces the safety of all vulnerable road users. For example, when a vehicle stops on a bicycle crossing, a cyclist or e-scooter user is forced to enter the pedestrian crossing, increasing the chance of collision between a micromobility user and a pedestrian. Additionally, vehicles stopped in the intersection block the view of other users, thus increasing the risk of a traffic accident due to poor visibility.

Furthermore, it was observed that some e-scooter users, due to the situation at the intersection, chose to dismount and cross the road as pedestrians instead of micromobility users. This behavior indicated that micromobility users felt unsafe using the cycling crossings and chose a slower-moving option to better react to the fast-changing situation at the intersection.

In general, considering the intersection context discussed above, it can be stated that despite the already implemented safety measures, the intersection between Pieninės and Saltoniškių streets still contains several conflict points. Traffic accidents involving micromobility users, pedestrians, and vehicles further demonstrate the need to reduce or eliminate these conflicts as much as possible. Additionally, the traffic flow analysis confirms the need to improve this intersection in order to enhance safety for all users. The following subchapter, based on the context provided, proposes design suggestions informed by local and international micromobility safety practices to improve the safety of the intersection.

4.2.4. Design Suggestions

Considering the identified intersection problems and safe micromobility design practices [

46,

47,

48], two design suggestions were proposed. Each recommendation, along with its pros and cons, is discussed in this subchapter.

First, in terms of general safety, it is proposed that the driveway at the intersection be removed. The main rationale for this recommendation is that the driveway introduces unnecessary conflict points between vehicles, micromobility users, and pedestrians. It is suggested that the entrance to the parking lot be relocated to one of the two intersections located upstream or downstream of Saltoniškių Street (see

Figure 14). Option A already includes a connection between the two parking lots, which is currently closed by the gate. Option B is more complex due to the slope at the rear of the building. However, with appropriate engineering solutions, this area could be made into a driveway that connects to the existing path along the side of the building. This design suggestion removes the identified conflict points and is incorporated into both proposed intersection design alternatives.

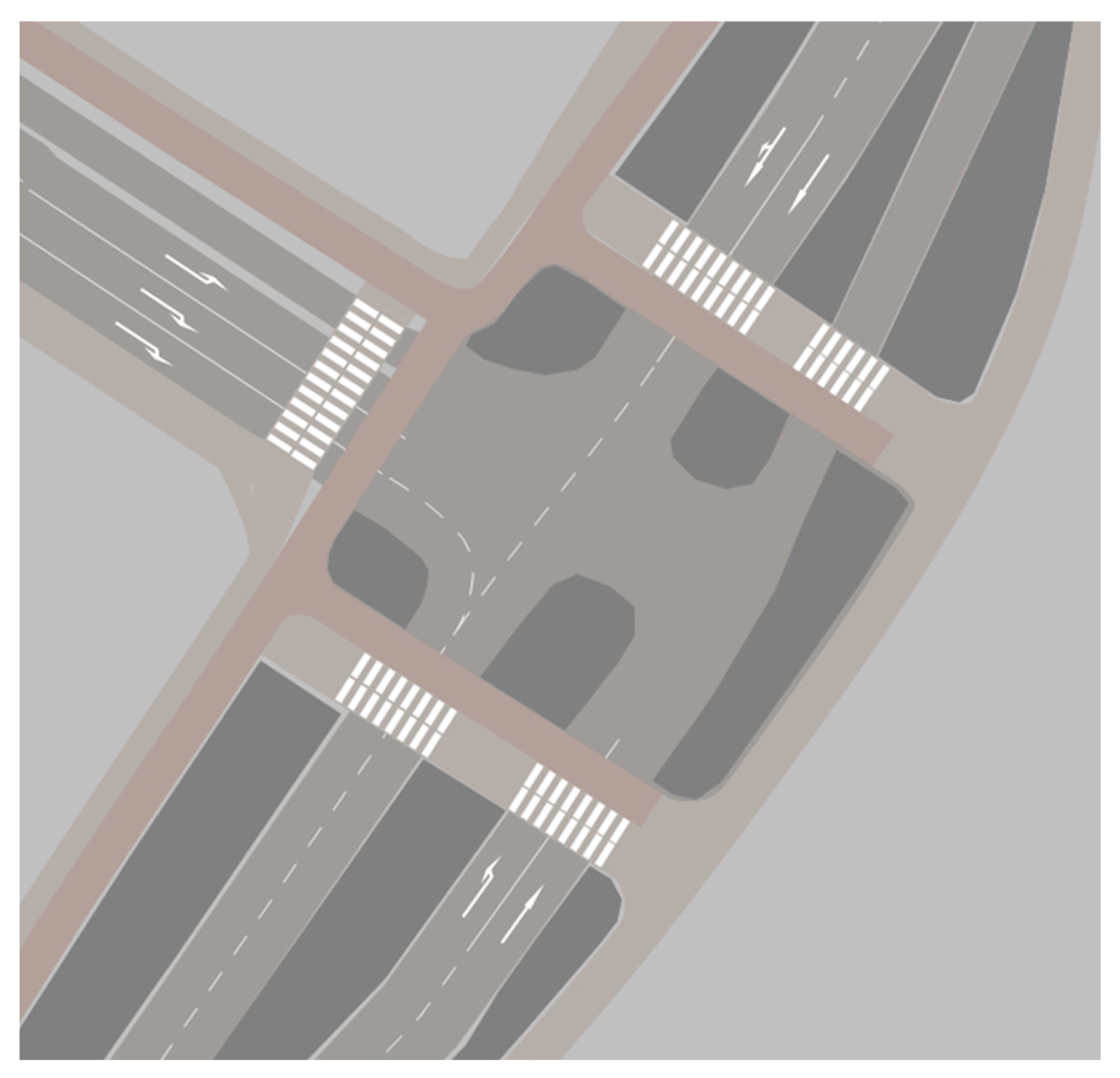

The first proposed alternative, which is a modification of an existing unsignalized intersection, can be seen in

Figure 15. In this alternative, Saltoniškių Street is curved toward the closed driveway while maintaining it as a raised intersection. This realignment creates additional space for vehicles to stop between the intersection and the bicycle crossing at Pieninės Street when entering from Pieninės Street and exiting Saltoniškių Street toward Pieninės Street. This modification addresses a problem observed during the traffic flow analysis, where high traffic volumes and lack of space forced vehicles to stop on the bicycle crossing at Pieninės Street, creating unsafe conditions for micromobility users. Additionally, the realignment provides wider areas at the road curves, improving visibility for both drivers and cyclists.

Furthermore, the two traffic directions at Saltoniškių Street are separated more widely, thus creating bigger refuge islands for both pedestrians and cyclists. Larger refuge islands provide more visibility for all intersection users and additional time for pedestrians and cyclists to shift their focus from one traffic direction to another when crossing the street. Moreover, the wider traffic direction separation creates space in the middle of the intersection where vehicles could safely stop and evaluate oncoming traffic before completing their turn. It enhances safety for vehicle drivers, especially during rush hour when traffic congestion is observed.

Despite the pros of this design, the main drawback of this intersection is that it relies heavily on driver behavior. As discussed, the proposed design creates additional stopping spaces for vehicles entering and exiting the intersection. However, it is still possible that vehicle drivers will disobey traffic laws and stop on the pedestrian or cyclist crossings, thus creating unsafe conditions for vulnerable road users.

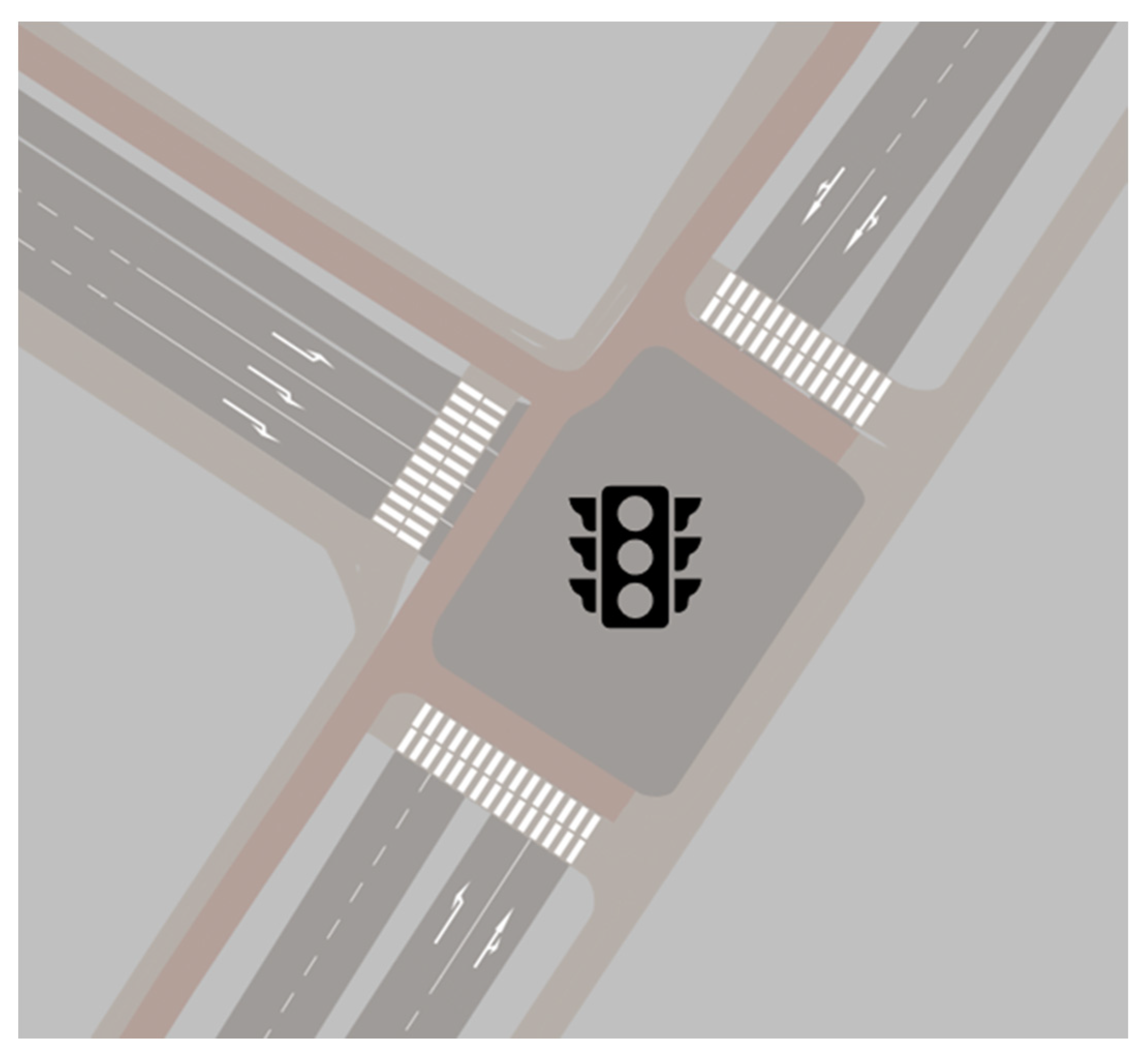

The second proposed alternative is a signalized intersection, shown in

Figure 16. Apart from the removed driveway, the main geometry of the intersection remains unchanged, but a traffic light is introduced to regulate traffic flows.

By introducing traffic lights, traffic flows can be regulated more strictly, allowing for safe green light phases for both pedestrians and cyclists.

However, if protected traffic light phases for vulnerable road users are not designed properly, they may cause delays at an intersection. Additional infrastructure elements, such as cyclist detectors or pedestrian-activated green light buttons, may help improve traffic flow [

55,

56]. Nevertheless, current traffic flow models typically assume fixed traffic signal phasing, limiting the representation of such adaptive measures.

4.3. Proposed Design Modelling and Final Design Recommendations

The final phase of the methodological application is to model the proposed design alternatives and evaluate them using a cost–benefit analysis. As noted earlier, PTV Vissim software is used to model traffic flows at the selected intersection. This modelling enables an assessment of the potential impact on traffic flows at the intersection. The following subchapters describe the traffic flow modelling process and the model evaluation, followed by a discussion of the most suitable design alternative for the selected intersection.

4.3.1. Intersection Traffic Flow Modelling

The observed traffic flows were calculated in intervals of 5 min and used to simulate and evaluate the performance of the intersection in terms of traffic flow over 1 h. Traffic data was collected over a 20 min period using an aerial drone. For the purpose of traffic flow modeling, it was assumed that conditions remained constant during the remainder of the hour. Accordingly, the observed 5 min traffic intervals were cyclically repeated to simulate the full one-hour period.

It was noticed that during the evening rush hour, traffic flow issues were caused by an intersection downstream of Saltoniškių Street at T. Narbuto Street. However, replicating the exact traffic situation would require additional analysis and modelling of the two intersections. Therefore, as a simplification, a basic traffic light was simulated at the intersection of Saltoniškių and T. Narbuto streets.

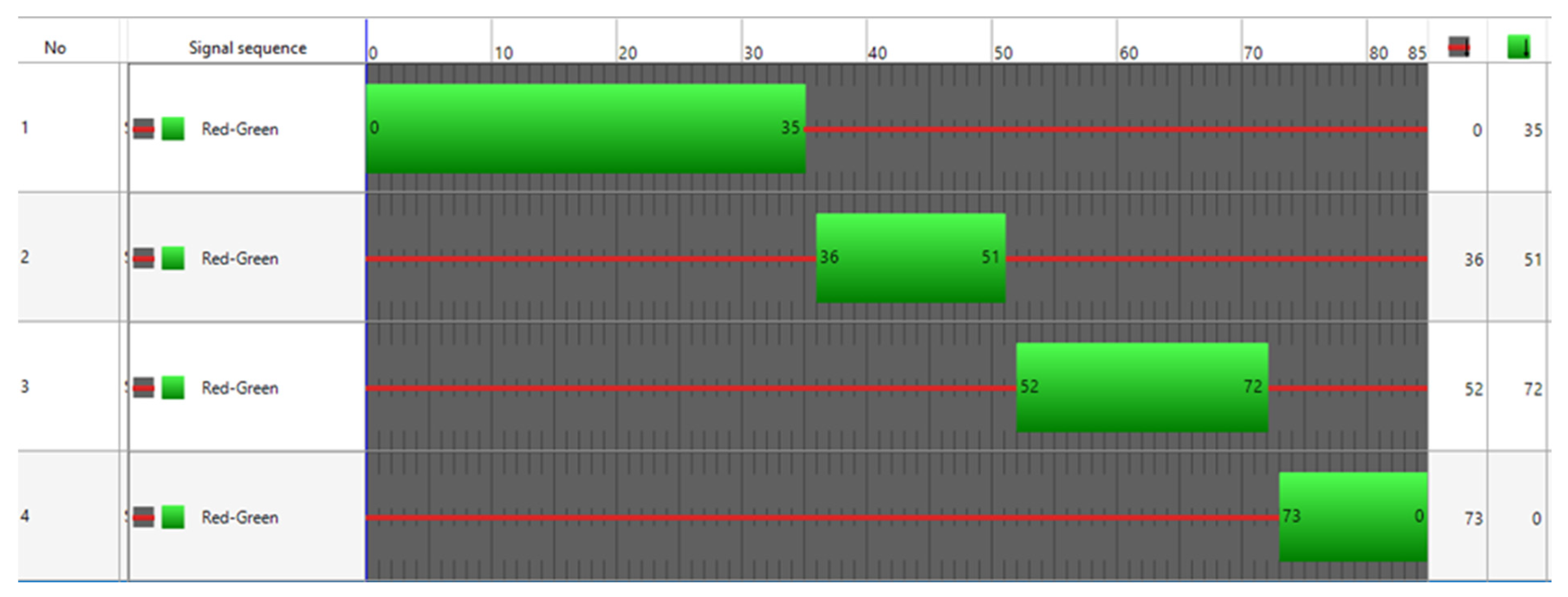

For the modelling of Alternative II, the traffic light was configured so that vehicles and vulnerable road users were completely separated to ensure maximum safety. The final traffic light configuration is provided in

Figure 17 below. The traffic light sequence consisted of a Red-Green phase with a total cycle time of 85 s. Signal sequence No. 1 was used for vehicles at Saltoniškių Street, No. 2 for pedestrians and cyclists crossing Saltoniškių Street at both crossings at the same time, No. 3 for vehicles at Pieninės Street, and No. 4 for pedestrians and cyclists crossing Pieninės Street. Additionally, 1 s of red light for all users was added to enhance safety.

4.3.2. Evaluation and Discussion of Proposed Design Alternatives

The vehicle delay was calculated for each scenario and converted into hourly traffic delay costs. The modelling results show that the current intersection configuration produces an average vehicle delay of 66.56 s, while Alternative I reduces it to 55.31 s. Alternative II, which introduces signalization, results in the highest delay of 127.55 s. These delay values were monetized as part of the external cost assessment, resulting in traffic delay costs of €9.61 for the current situation, €7.98 for Alternative I, and €18.41 for Alternative II (

Table 9). These figures were then incorporated into the 20-year cost–benefit analysis alongside environmental costs (CO

2 and NO

x) and accident reduction benefits. This integration ensures that design alternatives are evaluated not only for safety improvements, but also for their impact on traffic efficiency and environmental performance. It is evident that Alternative II has the highest total hourly costs, whereas Alternative I has the lowest. Therefore, in terms of hourly traffic flow costs, Alternative I is the most favorable solution.

A cost–benefit analysis is used to further evaluate the proposed alternatives. The benefits for each alternative are calculated based on impact coefficients from Trava LT 5.2 Measures and Models [

52] that indicate the possible impact on traffic accidents. For Alternative I, coefficient 409, corresponding to improved visibility, was applied, indicating a 5% reduction in traffic accidents involving micromobility users. For Alternative II, coefficient 109, corresponding to traffic light installation for vulnerable road users, was selected, indicating a 25% reduction in such accidents. These coefficients for the reduction in traffic accidents were then applied to the average annual traffic accident costs for micromobility users at the selected intersection, which were calculated at €14,794 per year.

The total annual traffic costs consist of travel time delay and environmental impact costs observed by traffic flow simulation, as well as the remaining costs of annual traffic accidents after applying the impact coefficients. As mentioned in

Section 3.4, the cost–benefit analysis was calculated with a 5% yearly discount factor for 20 years.

Table 10 shows the summary of cost–benefit analysis for 20 years.

The resulting total costs indicate that, compared with the current situation, Alternative I reduces intersection costs by 41%, whereas Alternative II increases total annual intersection costs by 78%. In terms of benefits, Alternative II yields 5 times greater benefits than Alternative I. Although the net benefits for all scenarios are negative, Alternative I has the smallest net loss. Finally, Alternative II has the highest benefit-to-cost ratio at 0.018.

Based on both the hourly costs of traffic flow and the cost–benefit analysis, Alternative I exhibits the lowest hourly costs and the highest net benefit values. In contrast, Alternative II has the highest hourly costs but the greatest total benefits and the most favorable benefit-to-cost ratio. Moreover, statistics indicate that signalized intersections, represented by Alternative II, tend to experience fewer traffic accidents [

57]. Therefore, considering the overall context of this study, which focuses on micromobility safety, Alternative II is chosen as the most suitable design suggestion to improve micromobility safety at the selected intersection.

It is also important to note that improving micromobility safety extends beyond infrastructure design. As emphasized by the International Transport Forum, it is also vital to improve micromobility safety in terms of vehicle design and user behavior to effectively integrate this mode of transportation into the existing mobility systems and societies [

15,

58].

5. Discussion

This study demonstrates how a structured methodology can be used to identify and analyze high-risk locations for micromobility users. By integrating macro-level spatial analysis to detect high-risk intersections across the urban network with micro-level assessments—including traffic flow modeling and cost–benefit evaluation—this research offers a comprehensive approach to enhancing micromobility safety in urban environments.

A key finding is the discrepancy between the locations ranked by accident costs and those ranked by crash rates. For example, intersection No. 1 (Gedimino av.—A. Jakšto str.—A. Stulginskio str.) recorded the highest total accident costs due to the number of non-fatal injury cases. In contrast, intersection No. 2 (Gedimino Ave.—Vilniaus St.—Jogailos St.) exhibited the highest crash rate, indicating that more crashes occurred there due to traffic intensity. This highlights the importance of using multiple metrics when assessing intersection safety, as relying solely on crash counts or severity may overlook high-risk locations with less traffic.

This suggests that infrastructure alone may not be sufficient for safety, and that user behavior and traffic organization play a critical role.

The proposed design alternatives for the unsignalized intersection included the installation of traffic lights, which were analyzed using traffic flow simulation and cost–benefit analysis. Alternative I, which involved geometric modifications without adding traffic lights, resulted in the lowest hourly traffic costs and the smallest net loss. In contrast, Alternative II, which incorporated signalization, produced the greatest reduction in accident risk and the most favorable benefit-to-cost ratio, despite its higher traffic flow costs.

FCD were employed to estimate traffic volumes where traditional traffic counts was impossible. The validation process indicated acceptable accuracy, with an R2 value of 0.87 and the mean absolute error of less than 15%. However, reliance on FCD introduces some limitations related to data granularity and calibration, which should be addressed in future research.

From a policy perspective, this study demonstrates how local governments can apply data-driven and context-specific planning methods to improve urban design and safety. The proposed methodology is adaptable to other urban areas and provides a scalable approach for enhancing micromobility safety. Furthermore, the findings support the strategic goals outlined in the Vilnius Sustainable Mobility Plan, particularly the aim to integrate micromobility into the urban transport system more effectively.

Future research should examine the long-term effects of the introduced design modifications. It should also explore the use of real-time data, study how users interact at intersections, and expand the cost analysis to include construction and maintenance, offering a more complete picture of the economic impact.

6. Conclusions and Contributions

To conclude, this research developed and proposed a methodological framework consisting of 3 main parts: (1) Spatial analysis, (2) Selected intersection analysis and design planning, and (3) Proposed design modelling and final design recommendations. Overall, it presents a data-driven approach for identifying and analyzing problematic intersections in terms of micromobility traffic safety.

The proposed methodology was applied to a selected area of interest located in Central Vilnius, Lithuania. It helped to identify 8 problematic intersections within the selected data range and criteria.

Next, the identified intersections were analyzed. The most problematic intersection in terms of traffic accident costs was the intersection between Gedimino Avenue, A. Jakšto and A. Stulginskio Streets, with total accident costs of €333,878.2. Meanwhile, in terms of intersection crash rate, the most high-risk intersection was between Gedinimo Avenue, Vilniaus and Jogailos Streets, with an intersection crash rate value of 0.151.

Finally, the selected intersection between Saltoniškių and Pieninės Streets was analyzed to identify current issues and propose design suggestions that would enhance traffic safety for micromobility users. This analysis resulted in two design proposals: a curved unsignalized intersection (Alternative I) and a signalized intersection (Alternative II). Based on traffic flow modelling and cost–benefit analysis, Alternative II was proposed as a final design recommendation aimed at improving micromobility safety.

This study contributes to the field by integrating macro-level spatial analysis with micro-level intersection modelling within an end-to-end framework. The proposed methodology combines KDE-based hotspot detection and intersection crash rate calculations with calibrated FCD exposure data. The selected intersection in Vilnius is analyzed using drone-based traffic observation and conflict metrics. Design alternatives are proposed and modelled using PTV Vissim to evaluate their impact on traffic flow and safety.

Unlike previous studies that remain theoretical or simulation-based, this research includes direct implementation and validation of infrastructure improvements on-site. This practical application enhances the relevance and transferability of the methodology to other urban contexts.

This study introduces a practical, mixed-method framework that integrates macro-level GIS-based hotspot detection with micro-level intersection modelling, calibrated floating car data (FCD) exposure, and drone-based conflict observation. The approach is further strengthened by simulation-based design evaluation and on-site validation, moving beyond prior international research that typically relies on crash-based or purely simulated analyses. While the methodology is transferable, its successful application depends on the availability and quality of certain inputs. The essential datasets include crash records with location details, traffic exposure estimates (e.g., FCD or traditional counts), and intersection geometry. If some inputs are missing, the framework can adapt by using alternative exposure proxies (such as modelled flows or aggregated counts) and simplified crash metrics. This flexibility supports scalability across cities with different data structures and levels of detail.

7. Limitations and Future Research

Although the main research objective was successfully achieved through the identification, analysis, and design recommendations for the selected area of Vilnius City, the study has several limitations, which should be acknowledged and discussed to provide context for interpreting the results and guiding future research.

While certain limitations are straightforward, such as the grid size of the heatmap, the span of the traffic accident data, or the overall country- and city-specific traffic trends that require case-by-case derivation, several limitations should be addressed in greater detail.

- -

Scaling of Floating Car Data (FCD). While for the Vilnius case study, the R-squared value was 0.87, indicating that 87% of the scaled FCD values represent the actual observed traffic flows from JUDU sensor data, the scaling factor could be further calibrated by enhancing the current linear approach. Future work could begin with an uncertainty analysis of the JUDU sensor data to identify possible deviations between sensor measurements and actual field-observed flows. Furthermore, the scaling factor might be made conditional on variables such as road type, intersection type, surrounding land use, and other relevant metrics. This calibration could be achieved by identifying the uncertainty of INRIX FCD compared with field-validated traffic flows across selected road sections and locations.

- -

Intersection Crash Rate (ICR) only considers traffic accident and traffic flow data. This simplification raises certain limitations for this research. To better understand and evaluate the resulting crash rates, additional statistical testing, such as correlation with intersection geometries, traffic control types or land use, could be incorporated in future research. The additional statistical testing would expand the identification of problematic intersections, helping to identify the potentially problematic intersections that are not identified with the proposed methodology.

- -

Traffic accident statistics. This dataset is one of the fundamental components of the proposed methodology, ensuring that it should be of the highest quality to achieve accurate results. Despite Lithuanian traffic accident data being well-documented, containing detailed information on accidents, and spanning more than a decade, it should be validated in future research to confirm data integrity and identify potential biases. Additionally, the dataset excludes accidents that were not reported to the police, meaning that a clearer representation of the case study area could be obtained if supplementary data were collected and integrated into the heatmap generation process. For instance, intersection geometry or type could be included as additional variables to improve the identification of high-risk intersections. Finally, the research could be further extended to other countries, applying locally sourced data and comparing the results across different urban contexts.

- -

Sensitivity and validation limitations. A formal sensitivity analysis was not conducted because the primary goal of this study was to develop a general methodological framework rather than optimize specific parameters. However, this represents an important limitation. Future research should incorporate sensitivity testing and cross-validation of results to ensure robustness and transferability of the methodology across different urban environments.