1. Introduction

Universities around the world are changing significantly as they respond to new technology, growing expectations for sustainability, and increased global competition. In this setting, the smart campus has become an important model for the future of higher education. The idea comes from the broader smart city movement [

1] and goes beyond simply using digital tools. It involves rethinking how teaching, management, and services are delivered through intelligent, connected, and data-driven systems. Technologies such as the Internet of Things (IoT), artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and big data analytics now help create flexible learning environments, improve operational efficiency, and support long-term sustainability for institutions [

2,

3,

4].

As a result, digital transformation is now a top priority for modern universities. Fast technological change, stronger competition, and shifting stakeholder expectations are leading institutions to rethink how they work, collaborate, and make decisions. Advanced digital platforms, from cloud systems to analytics dashboards, help universities govern more effectively, improve service integration, and create new ways to engage with students, staff, and communities. However, technology alone does not ensure successful change. Research shows that organizational readiness—such as committed leadership, a supportive culture, and ongoing staff development—is key to the success of digital projects [

5,

6,

7]. External factors like government policy, competition, and stakeholder needs also affect how quickly and in what direction universities change [

8].

The Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, introduced by Tornatzky and Fleischer [

9], offers a comprehensive lens for understanding how these interacting factors shape innovation adoption. Although widely applied in digital transformation research, empirical validation within Southeast Asian higher education remains limited, despite the region’s rapid investment in digital modernization [

5]. This gap underscores the need for a theoretically grounded examination of how technological capability, organizational conditions, and environmental support collectively influence smart campus development.

In response to this identified need, the present study develops and empirically tests a causal model of Smart Campus success within Thai higher education, grounded in the TOE framework. The model evaluates how three categories of readiness—technological, organizational, and environmental—are associated with four sustainability-oriented performance domains:

economic (efficiency, innovation, resource use).

social (learning quality, inclusivity, community engagement).

environmental (green practices, energy management, sustainability).

governance (transparency, cybersecurity, evidence-based decision making).

Collectively, these domains provide a comprehensive perspective on the determinants of Smart Campus success, aligning with global sustainable development objectives.

Accordingly, this study seeks to address the following research questions:

1. What theoretically derived causal factors are statistically associated with Smart Campus success across the four sustainability domains?

2. How does an integrated causal model combining TOE constructs and sustainability outcomes advance theoretical understanding and practical application of Smart Campus development?

3. Which structural relationships, as theoretically proposed, are empirically supported in the Smart Campus context?

This study employed a quantitative methodology utilizing structural equation modeling (SEM), drawing on data from 96 administrators across 126 Thai higher education institutions. The findings indicate that technological, organizational, and environmental factors all contribute to institutional change, with organizational readiness emerging as the most influential determinant. By affirming the applicability of the TOE framework in higher education, this research provides both theoretical insights and practical recommendations for policymakers and university leaders seeking to enhance digital transformation and competitiveness in Thailand and Southeast Asia.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Model

A quantitative research design, based on the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, was employed to investigate the associations between technological, organizational, and environmental factors and Smart Campus success in Thailand. The study utilized a deductive approach to test theoretically derived hypotheses. Data were collected through a structured questionnaire and analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to validate the proposed causal relationships.

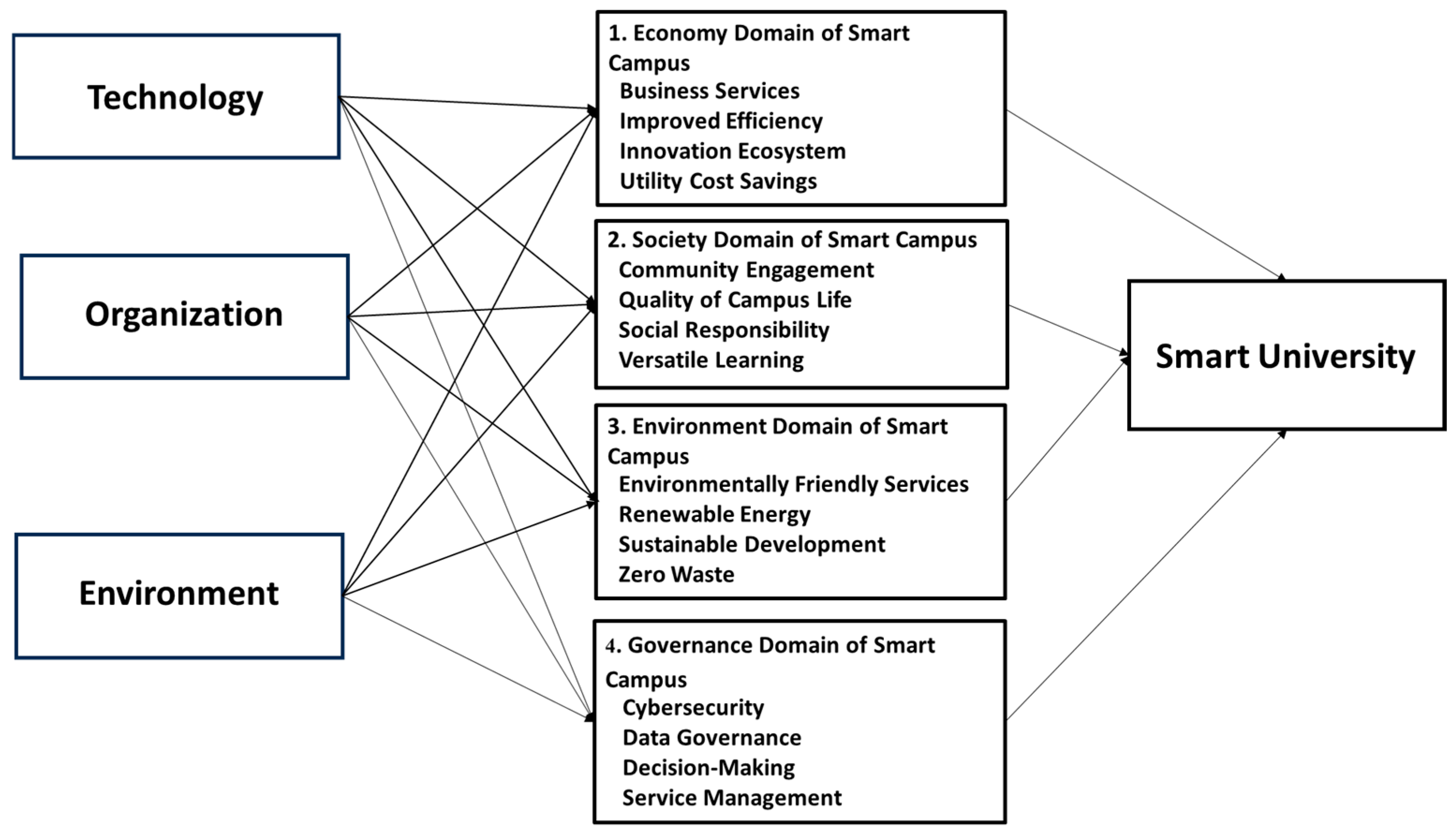

The conceptual model (

Figure 1) comprises three independent latent constructs: Technology (TECH), Organization (ORG), and Environment (ENV), which represent the three TOE dimensions. These constructs are hypothesized to influence Smart Campus success (smart_U) through four sustainability-oriented performance domains.

Economic domain: efficiency improvement, innovation ecosystem, business services, and cost reduction;

Social domain: community engagement, quality of campus life, social responsibility, and flexible learning;

Environmental domain: eco-friendly services, renewable energy, sustainable development initiatives, and zero-waste operations;

Governance domain: cybersecurity, data governance, evidence-based decision-making, and smart service management.

The model proposes that each TOE dimension exerts direct positive effects on the four Smart Campus domains, which in turn contribute to overall Smart Campus success. This structure results in sixteen hypotheses (H1 to H16) that capture the directional relationships among the latent constructs.

Technology Perspective (TECH)

H1: The technology perspective positively influences the economic domain of Smart Campus development.

H2: The technology perspective positively influences the social domain of Smart Campus development.

H3: The technology perspective positively influences the environmental domain of Smart Campus development.

H4: The technology perspective positively influences the governance domain of Smart Campus development.

Organization Perspective (ORG)

H5: The organization perspective positively influences the economic domain of Smart Campus development.

H6: The organization perspective positively influences the social domain of Smart Campus development.

H7: The organization perspective positively influences the environmental domain of Smart Campus development.

H8: The organization perspective positively influences the governance domain of Smart Campus development.

Environment Perspective (ENV)

H9: The environment perspective positively influences the economic domain of Smart Campus development.

H10: The environment perspective positively influences the social domain of Smart Campus development.

H11: The environment perspective positively influences the environmental domain of Smart Campus development.

H12: The environment perspective positively influences the governance domain of Smart Campus development.

Smart Campus Outcome Domains (smart_U)

H13: The economic domain positively contributes to overall Smart Campus success.

H14: The social domain positively contributes to overall Smart Campus success.

H15: The environmental domain positively contributes to overall Smart Campus success.

H16: The governance domain positively contributes to overall Smart Campus success.

This causal structure offers a comprehensive framework for analyzing the interaction between internal capabilities and external environmental conditions in supporting Smart Campus transformation. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was employed to empirically test the magnitude and direction of the hypothesized relationships among latent constructs.

3.2. Population and Sample

The study population consisted of senior administrators from 126 higher education institutions (HEIs) in Thailand, comprising 57 public universities, 26 autonomous universities, and 43 private universities. Given that the target respondents were high-level executives, who are relatively few and often difficult to access, the study obtained 96 valid responses. According to Hair [

27], an appropriate sample size for Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) typically ranges from 10 to 20 times the number of free parameters. Further methodological guidance indicates that SEM can be reliably conducted with samples between 50 and 100 when models are theory-driven, structurally constrained, and exhibit strong factor loadings [

28,

29].

To further justify sample adequacy, the structural complexity of the final second-order TOE–Smart University model was evaluated. The model required estimation of 42 free parameters, including factor loadings, error terms, latent variances, covariances, and structural paths. With a sample size of N = 96, the parameter-to-sample ratio was 1:2.29, which is within acceptable limits for theory-based SEM, especially when supported by robust model identification and strong measurement properties.

A post hoc RMSEA-based power analysis, following MacCallum et al. [

30], was conducted using α = 0.05, df = 96, H

0: RMSEA = 0.05, and H

1: RMSEA = 0.08. The resulting statistical power of 0.84 exceeded the commonly accepted threshold of 0.80, indicating that the sample size is sufficient for detecting meaningful model misfit. Collectively, these diagnostics confirm that the sample of 96 respondents is statistically adequate and methodologically appropriate for estimating the proposed causal model.

A purposive sampling strategy was implemented to ensure inclusion of only administrators with institutional decision-making authority as key informants. In Thai HEIs, this authority is typically held by the President (Rector), Vice Presidents, and Assistant Presidents. Consequently, one questionnaire was sent to each institution and addressed directly to the President or a designated senior administrator authorized to respond on behalf of the institution. This approach ensured that each returned questionnaire reflected an official institutional position rather than an individual opinion.

A total of 126 administrators, one per HEI, were invited to participate. Of these, 96 completed the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 76.19%. As each institution contributed only one response from an authorized executive, the dataset represents leadership-level perspectives across Thailand’s higher education system. To minimize potential self-selection bias common in online surveys, invitations were sent individually to named senior executives rather than through open distribution channels, ensuring that each response reflected an authenticated institutional viewpoint.

3.3. Research Instrument

A structured questionnaire was designed utilizing the Technology-Organization-Environment (TOE) framework and validated constructs from previous studies. The instrument comprised four distinct sections:

Respondent and institutional background information;

Independent variables reflecting technological, organizational, and environmental dimensions;

The dependent variable, Smart Campus success, assessed across four domains: economic, social, environmental, and governance; and

Open-ended questions soliciting additional comments or recommendations.

All closed-ended items utilized a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Mean scores were interpreted according to standard guidelines: 4.21–5.00 (very high), 3.41–4.20 (high), 2.61–3.40 (moderate), 1.81–2.60 (low), and 1.00–1.80 (very low).

To ensure clarity and consistency, each item was formulated as an evaluative statement requiring respondents to indicate their perceived level of implementation, presence, or effectiveness of specific practices within their institution. The initial instrument included 86 items. Following expert review, seven items with Index of Item–Objective Congruence (IOC) scores below 0.50 were eliminated, resulting in a refined set of items aligned with the TOE constructs and Smart Campus performance domains.

Content validity was evaluated by three expert raters specializing in higher education administration, digital transformation, and research methodology. Items with IOC scores of 0.50 or higher were retained for further testing. Although this threshold is more permissive than the commonly used cutoff of 0.67, it was applied during the preliminary screening stage. All retained items subsequently underwent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), which demonstrated strong factor loadings and satisfactory construct validity. This two-stage validation process ensured that the final measurement items met acceptable standards of conceptual clarity and empirical rigor.

Due to institutional confidentiality requirements and the use of context-specific indicators designed for internal assessment within Thai higher education institutions, the full questionnaire cannot be reproduced verbatim in this manuscript. However, all constructs, sub-dimensions, and indicator descriptions are presented in the accompanying tables and methodological explanations, providing sufficient detail for evaluating the instrument’s conceptual alignment, wording precision, and content validity.

3.4. Validity and Reliability

Content validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by five experts specializing in higher education administration, digital transformation, and research methodology. Each item was assessed using the Index of Item–Objective Congruence (IOC), and items with scores of 0.50 or higher were retained for further refinement. This threshold was deemed suitable for initial screening, as subsequent psychometric evaluation was planned through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) during the main analysis phase.

Before the main data collection, a pilot study was conducted with 30 university administrators excluded from the primary sample. The pilot test aimed to assess item clarity, response consistency, and overall instrument usability. Feedback obtained from the pilot led to minor revisions in wording and formatting to improve respondent comprehension.

Reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. All constructs exhibited reliability coefficients exceeding 0.70, indicating acceptable internal consistency. According to established guidelines, coefficients above 0.90 are considered excellent, those above 0.80 are regarded as good, and values above 0.70 are acceptable for research instruments. The results confirmed that all scales demonstrated stable and coherent measurement properties appropriate for SEM-based analysis.

3.5. Data Collection and Analysis

An online questionnaire was administered via Google Forms to collect data. The survey link was distributed individually to senior administrators through institutional email, LINE, and Facebook to maximize accessibility and encourage participation. Prior to completing the questionnaire, respondents were informed of the study’s purpose, confidentiality protections, and voluntary participation. Data collection was conducted from January to July 2025, and all returned questionnaires were screened for completeness before analysis.

Procedural remedies were implemented to reduce potential common method bias (CMB). Anonymity was assured, questionnaire sections were separated to minimize response pattern contamination, and items were phrased neutrally to avoid leading responses. These procedures, which are commonly recommended in behavioral research, mitigate systematic bias arising from single-source data collection.

Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation, were computed using SPSS version 29.0 to summarize respondent characteristics. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were conducted in Mplus version 8.3 to evaluate the measurement model and to test the theoretically derived structural relationships among the TOE constructs and Smart Campus performance domains.

Several diagnostic checks were conducted to address concerns regarding estimation stability and model robustness. Maximum Likelihood (ML) estimation converged normally without warnings, and no inadmissible solutions were observed. All standardized factor loadings were positive and below 1.0, and no negative error variances (Heywood cases) were detected. Examination of standardized residuals revealed no patterns indicative of misfit, and modification indices did not suggest omitted paths that would meaningfully improve the model. Collectively, these diagnostics indicate that the model was not overfitted and that parameter estimates were stable despite the modest sample size.

Model fit was evaluated using widely accepted indices, including χ2/df, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SRMR. All criteria met recommended thresholds, demonstrating satisfactory global model fit and supporting the adequacy of the specified structural model. Due to the cross-sectional nature of the data, the estimated coefficients are interpreted as statistical associations consistent with the theoretical framework rather than as evidence of temporal causation.

Statistical assessments of common method bias were conducted to complement procedural remedies. Harman’s single-factor test indicated that the first unrotated factor accounted for 28.4% of the total variance, which is well below the 50% criterion, suggesting that no dominant factor inflated the results. A full collinearity assessment following Kock [

31] showed that all variance inflation factor (VIF) values ranged between 1.78 and 3.12, remaining below the conservative threshold of 3.3. These findings confirm that common method variance is unlikely to have substantially affected the structural relationships in the model.

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics were computed to examine the response patterns of the 96 senior administrators and to assess the suitability of the data for subsequent confirmatory and structural analyses. The questionnaire items were grouped into three TOE dimensions—Technology, Organization, and Environment—and four Smart Campus performance domains: economic, social, environmental, and governance.

Across all measurement items, mean scores ranged from 3.89 to 4.51, indicating generally high levels of agreement and suggesting that respondents perceived substantial progress in Smart Campus development within their institutions. Standard deviations ranged from 0.66 to 1.05, reflecting adequate variability without evidence of extreme dispersion.

Assessment of univariate normality indicated that skewness and kurtosis for all items fell within the acceptable ±2 range, suggesting that the data did not exhibit significant deviations from normality. These descriptive characteristics confirm that the dataset is well-suited for Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), meeting commonly accepted preliminary assumptions for multivariate analysis.

4.2. Reliability Analysis

A reliability analysis was conducted to evaluate the internal consistency of the measurement scales for the TOE dimensions and the Smart Campus performance domains. Cronbach’s alpha assessed the degree of interrelation among items within each construct. According to the guidelines established by Hair et al. [

27], reliability coefficients above 0.70 are considered acceptable, whereas values above 0.90 indicate excellent reliability.

Table 1 presents Cronbach’s alpha values for the constructs, which ranged from 0.888 to 0.969. The overall reliability coefficient for the full scale was 0.992. These findings indicate a high level of internal consistency across all constructs, confirming that the measurement instrument is psychometrically robust and appropriate for subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modeling (SEM).

4.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was examined to determine whether the three constructs within the TOE framework—Technology, Organization, and Environment—represent empirically distinct concepts. Because these constructs exhibited relatively high correlations, a rigorous assessment was necessary to ensure that each construct measured a unique domain rather than overlapping latent factors.

4.3.1. Larcker Criterion

The Fornell–Larcker criterion states that the square root of the average variance extracted (√AVE) of each construct should exceed its correlations with other constructs.

Table 2 presents the Fornell–Larcker matrix, with √AVE values on the diagonal and latent correlations in the off-diagonal cells.

Although correlations between Technology–Organization (0.903) and Organization–Environment (0.916) are relatively high, each construct’s √AVE remains higher than the corresponding correlation values. This indicates that the constructs retain acceptable discriminant validity under the Fornell–Larcker criterion.

4.3.2. AVE Versus Squared Correlation Comparison

To further evaluate discriminant validity, AVE values were compared with squared inter-construct correlations (r2). Discriminant validity is supported when AVE exceeds r2.

Although two construct pairs (Tech–Org and Org–Env) show r

2 values slightly higher than their AVEs, the Fornell–Larcker test still supports discriminant validity due to the higher √AVE values shown in

Table 3. This pattern is typical in higher-order models where closely related organizational constructs exhibit inherently strong correlations.

4.3.3. Note on HTMT

The Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio could not be computed because the measurement model employs aggregated (parceled) indicators for the three TOE constructs. Parceling eliminates item-level covariance information, which is required to compute HTMT values. Consistent with recommended practice for higher-order SEM models using composite indicators, discriminant validity was therefore assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion and AVE-versus-r2 comparisons.

Overall, the Fornell–Larcker matrix and AVE–r2 comparisons provide evidence that the constructs maintain acceptable discriminant validity. Despite high inter-construct correlations, the diagnostic results indicate that Technology, Organization, and Environment remain empirically distinguishable and conceptually meaningful within the TOE measurement model.

4.4. Testing and Presentation of Analysis Results

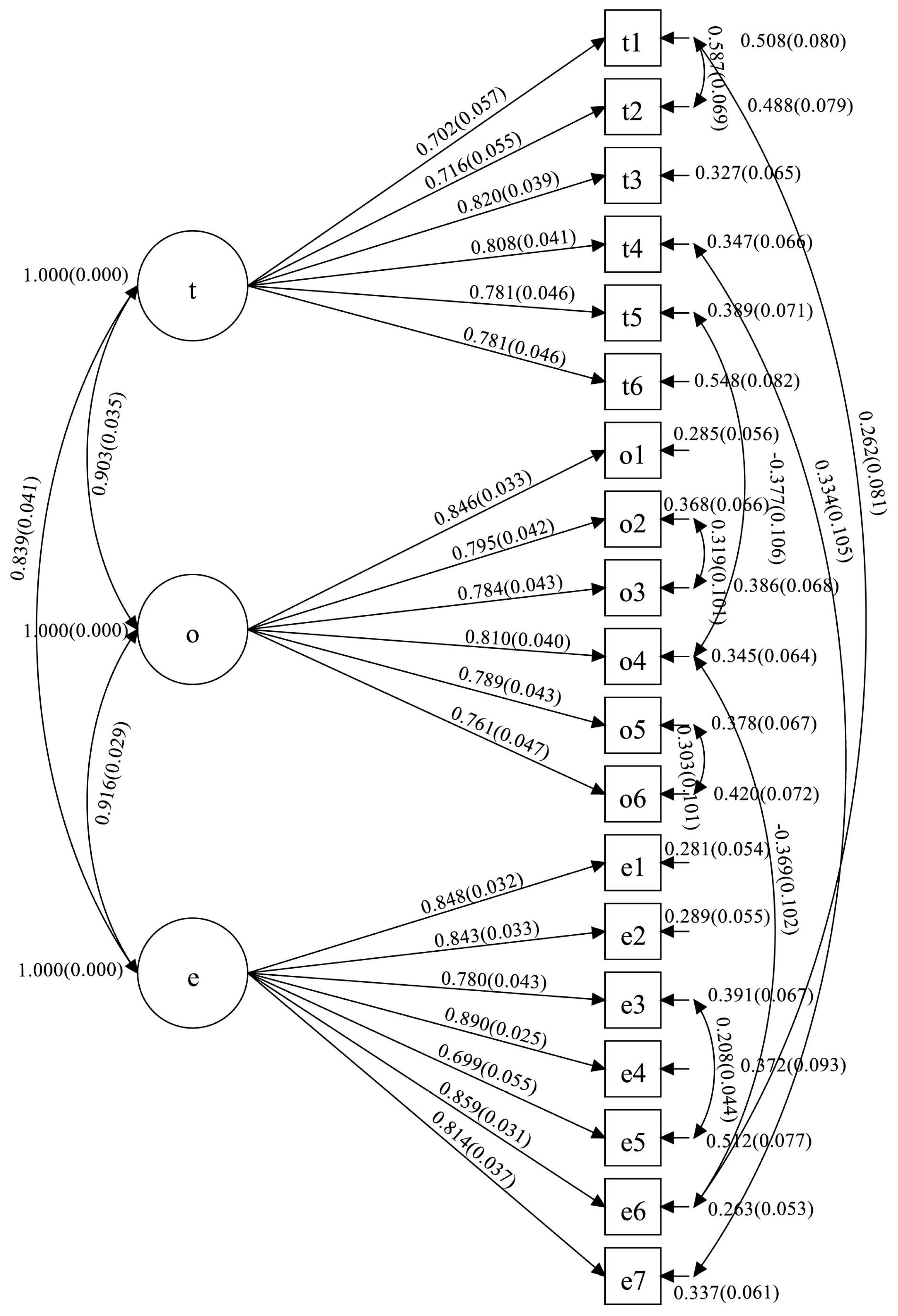

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed to assess the measurement validity of the three latent constructs: Technology, Organization, and Environment, as defined within the TOE framework. The CFA aimed to determine whether the observed indicators accurately represented their respective theoretical constructs. Measurement validity was evaluated using standardized factor loadings (β), squared multiple correlations (R2), average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha.

The results, presented in

Table 4, indicate that all standardized factor loadings were statistically significant (β = 0.672 to 0.890,

p < 0.001), demonstrating that each item contributed substantially to its respective construct. Composite reliability values ranged from 0.89 to 0.95, exceeding the recommended threshold of 0.70. AVE values ranged from 0.60 to 0.69, surpassing the minimum criterion of 0.50 as suggested by Hair et al. [

27]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients further confirmed strong internal consistency across all constructs.

Taken together, these findings confirm that the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory convergent validity and reliability. The results support the theoretical proposition that the three TOE dimensions—Technology, Organization, and Environment—are effectively represented by their observed indicators, thereby establishing a robust foundation for subsequent structural analysis.

Figure 2 displays the measurement model for the three latent constructs: Technology, Organization, and Environment, as defined within the TOE framework. Each construct was assessed using multiple observed indicators (Technology: T1–T6, Organization: O1–O6, Environment: E1–E7). All indicators showed positive and statistically significant factor loadings (β = 0.672–0.890,

p < 0.001), indicating that the items effectively represented their respective constructs.

The correlations among the three TOE dimensions were strong and positive: Technology–Organization = 0.903, Technology–Environment = 0.839, and Organization–Environment = 0.916. These results suggest substantial interdependence among the constructs and reinforce the theoretical coherence of the TOE framework in the context of Smart Campus research.

Overall, these findings confirm that the measurement model demonstrates satisfactory validity and reliability, establishing a robust foundation for subsequent structural analysis.

4.5. Confirmatory Factor Analysis and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM)

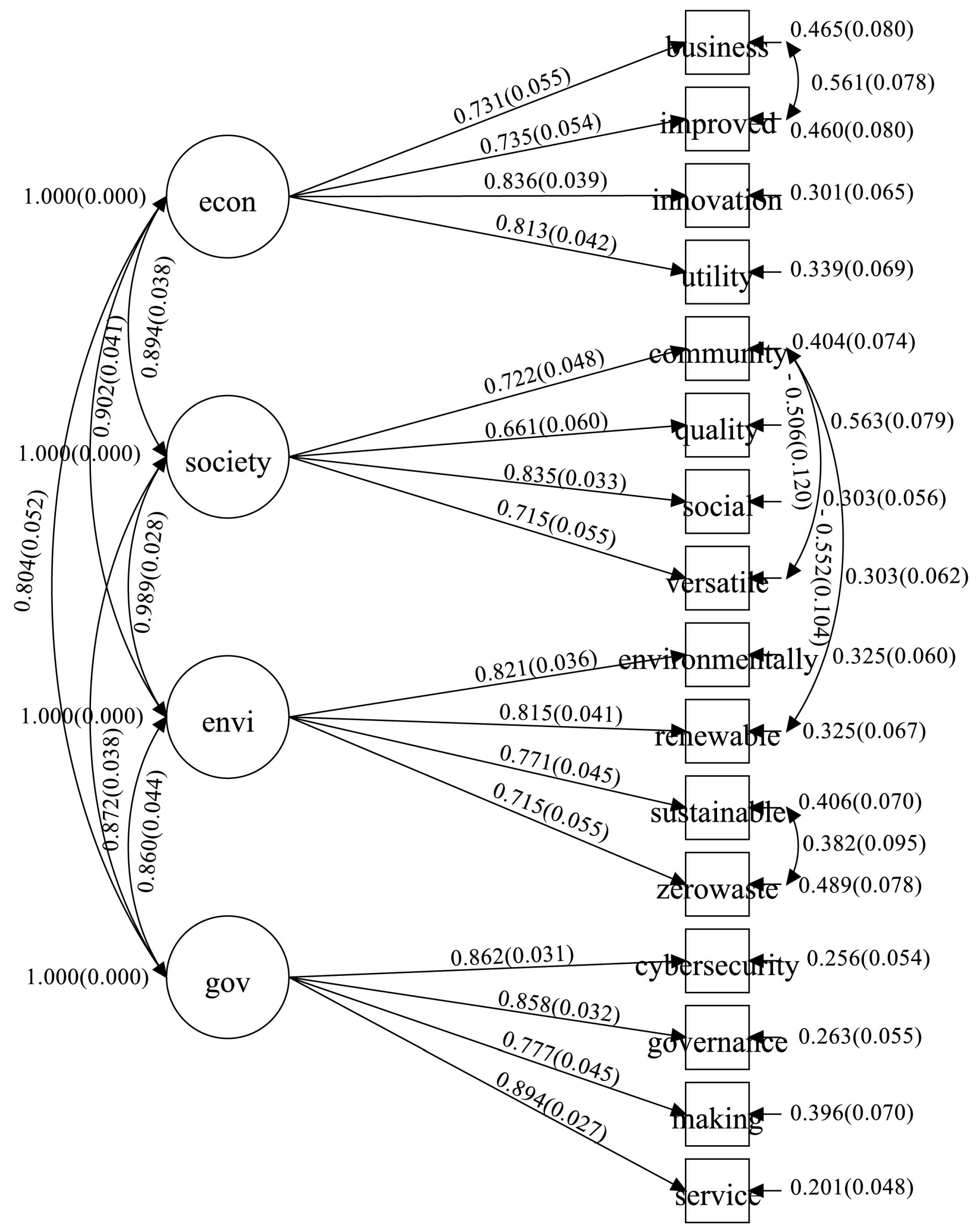

After validating the TOE measurement model, a second-order Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) were performed to evaluate the proposed Smart Campus success model. The structural model assessed the joint contributions of the Economic, Social, Environmental, and Governance performance domains to overall Smart Campus performance, as well as the influence of the three TOE dimensions on these domains.

Model quality and adequacy were assessed using several measurement indicators, such as standardized factor loadings (β), squared multiple correlations (R2), average variance extracted (AVE), composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha. These indices confirmed convergent validity, internal consistency, and the robustness of both the measurement and structural components of the model.

The CFA results indicated that all indicators loaded significantly onto their respective latent constructs, and all reliability and validity criteria met recommended thresholds. These findings offered strong empirical support for advancing to the full structural analysis, in which the hypothesized causal relationships among the TOE dimensions and Smart Campus domains were formally tested.

Table 5 reports the results of the confirmatory factor analysis for the four Smart Campus performance domains. All standardized factor loadings surpassed the recommended threshold of 0.60 and were statistically significant at

p < 0.001, demonstrating strong associations between observed indicators and their respective latent constructs. Composite reliability (CR) values ranged from 0.88 to 0.93, and average variance extracted (AVE) values ranged from 0.60 to 0.72. These results satisfy established criteria for internal consistency and convergent validity as recommended by [

20].

Collectively, these findings confirm that the four latent constructs—Economy, Society, Environment, and Governance—were measured with reliability and validity. This establishes a robust empirical basis for subsequent structural modeling and hypothesis testing.

Table 6 presents the global fit indices for the structural model, which collectively demonstrate an excellent fit to the data. The χ

2/df ratio was 1.16, and the chi-square statistic was not significant (

p = 0.0532), indicating no substantial discrepancy between the hypothesized model and the observed covariance matrix. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI = 0.998) and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI = 0.980) were both exceptionally high, confirming that the specified model closely reproduced the observed data. The standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR = 0.017) indicated minimal residual variance, and the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA = 0.059) was within the acceptable range for structural equation modeling applications. Collectively, these results provide robust empirical support for the proposed TOE–Smart Campus framework.

While the RMSEA value (0.059) is moderately higher compared to the near-perfect CFI and TLI values, this outcome aligns with the RMSEA’s established sensitivity to small sample sizes and low degrees of freedom. RMSEA values tend to increase slightly when the sample size is less than 200 or when χ2 values are close to zero, whereas incremental fit indices such as CFI and TLI remain more stable under these conditions. In the present study, the high CFI and TLI values indicate strong factor loadings and a coherent model structure, and the RMSEA value remains well within the recommended threshold of ≤ 0.08. Therefore, this divergence is attributable to sample-size characteristics rather than model misspecification.

Interpretation of model fit was not based solely on the χ2 statistic, given its sensitivity to sample size. Standardized residuals and modification indices were reviewed to identify potential areas of misfit. No theoretically meaningful model adjustments were warranted, and no post hoc re-specifications were performed. The final model corresponds directly to the original theoretical specification, and the diagnostic results collectively confirm that the model is well-specified and adequately represents the empirical data.

Figure 3 presents the structural relationships among the three exogenous TOE dimensions: Technology, Organization, and Environment, and the four endogenous Smart Campus performance domains: Economy, Society, Environment, and Governance. All standardized path coefficients were positive and statistically significant at

p < 0.05, indicating that each TOE dimension had a meaningful and theoretically consistent effect on the corresponding outcome domains. These findings demonstrate that the hypothesized causal structure is both stable and empirically supported.

The structural findings are consistent with earlier measurement tests. As shown in

Table 4, the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results established strong reliability and convergent validity for all latent constructs. The model fit indices reported in

Table 5 (χ

2/df = 1.16, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.017) also indicate excellent overall model fit.

Collectively, these results confirm that the TOE-based structural model is theoretically coherent and empirically robust, effectively explaining the multidimensional nature of Smart Campus success.

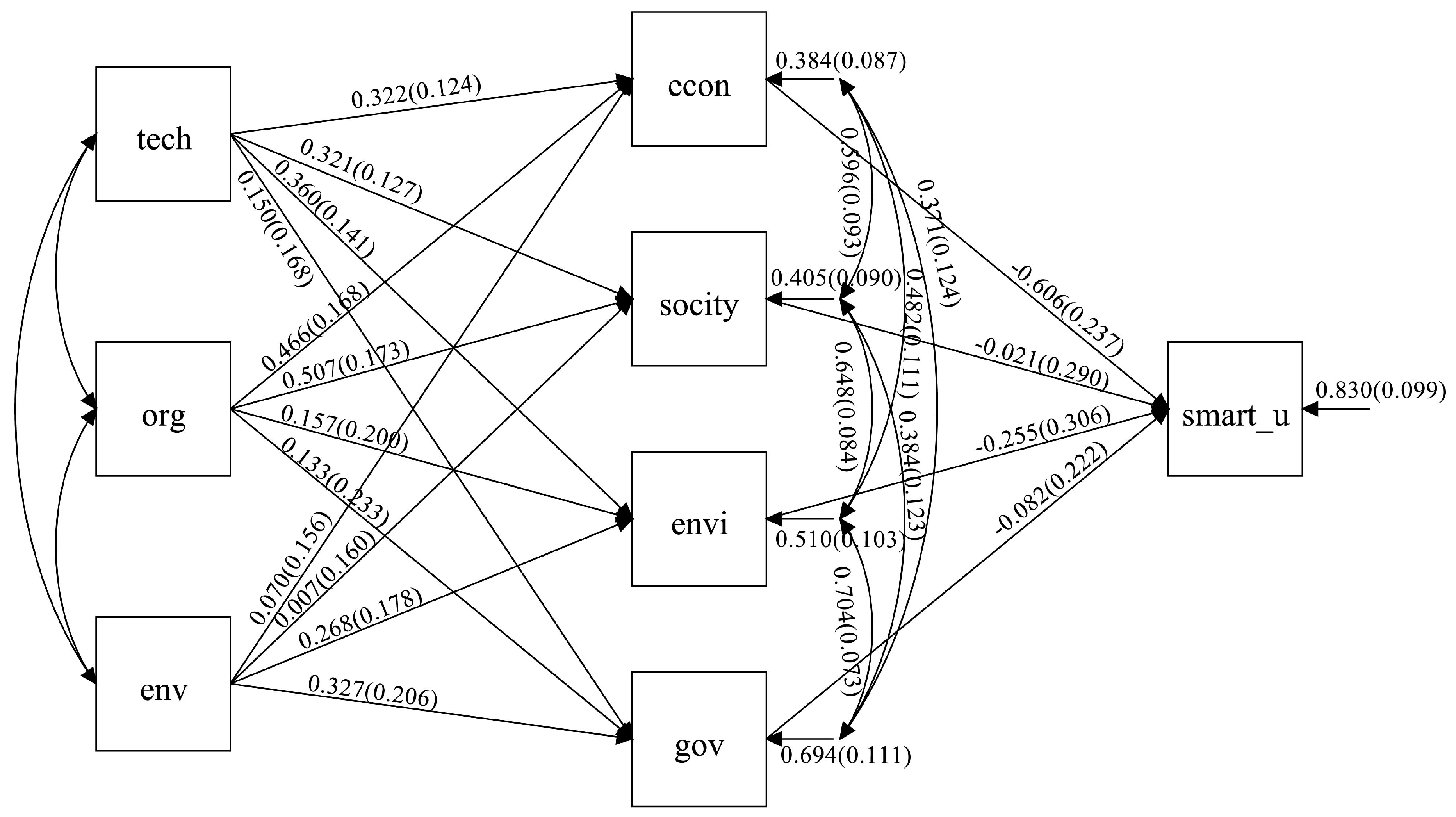

4.6. Hypothesis Testing and Path Analysis

Following confirmation that both the measurement and structural models exhibited satisfactory validity and fit, the hypotheses derived from the TOE framework were formally tested. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to estimate standardized path coefficients (β), standard errors (SE), critical ratios (C.R.), and p-values for all sixteen hypotheses (H1–H16). These estimates facilitated the identification of statistically significant relationships among the TOE dimensions and Smart Campus performance domains.

The results, summarized in

Table 7 and illustrated in

Figure 4, reveal structural relationships that collectively explain Smart Campus success. The significant pathways indicate that technological readiness, organizational capability, and environmental support each contribute to the economic, social, environmental, and governance outcomes of Smart Campus development. Collectively, these findings offer robust empirical support for the theoretical model and underscore the interconnectedness of the factors influencing Smart Campus performance.

Table 5 summarizes the hypothesis testing results. All sixteen structural paths (H

1–H

16) reached statistical significance at

p < 0.05, demonstrating that the relationships among the constructs align with the theoretical expectations of the TOE framework. The three exogenous factors, Technology, Organization, and Environment, each exhibited positive effects on the four Smart Campus performance domains, thereby supporting H

1–H

12.

Within the TOE dimensions, the strongest effects occurred between Organization and the Social domain (β = 0.326), as well as between Environment and the Governance domain (β = 0.342). These results underscore the importance of organizational readiness, including leadership commitment and institutional culture, and emphasize the influence of external environmental support, such as policy conditions and stakeholder expectations, in shaping Smart Campus development.

The four performance domains also had significant positive effects on overall Smart Campus success (H13–H16). The Economic domain contributed most substantially (β = 0.416), followed by the Social (β = 0.382), Environmental (β = 0.287), and Governance (β = 0.245) domains. These results indicate that enhancements in efficiency, innovation capacity, and resource management are closely associated with Smart Campus performance, while social engagement and environmental sustainability remain important contributors.

In summary, the results confirm that technological capability, organizational readiness, and environmental support collectively drive Smart Campus success in Thailand, providing robust empirical support for the TOE-based conceptual model.

Figure 4 presents the complete structural equation modeling (SEM) results, which illustrate the primary causal pathways linking the three Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) predictors—Technology, Organization, and Environment—to the four Smart Campus performance domains: Economy, Society, Environment, and Governance. All standardized path coefficients were positive and statistically significant at

p < 0.05, indicating that the structural relationships were stable and consistent with the theoretical expectations of the model.

As summarized in

Table 6 and depicted in

Figure 4, all sixteen hypotheses (H

1–H

16) received empirical support. These findings reinforce the robustness of the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework as an explanatory model for Smart Campus success. Among the three predictors, the organizational and environmental dimensions exerted the strongest effects, highlighting the significance of leadership commitment, institutional readiness, and supportive policy environments in facilitating digital transformation.

Collectively, these findings indicate that Smart Campus development is influenced not only by technological capability but also by institutional capacity for change management and by external conditions that support innovation.

5. Discussion

5.1. Overview of Key Findings

The findings indicate that the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework offers a robust and empirically validated explanation for Smart Campus success in the context of Thai higher education. All sixteen hypotheses (H1–H16) received statistical support, confirming that technological readiness, organizational capability, and environmental conditions collectively influence the four key performance domains: economic, social, environmental, and governance, which are integral to Smart Campus development.

Within the TOE dimensions, the organizational factor exerted the most substantial influence, particularly on the social domain (β = 0.326). This result emphasizes the significance of leadership commitment, institutional culture, and collective engagement in facilitating digital transformation. The environmental factor had the strongest effect on governance (β = 0.342), underscoring the impact of external pressures, national policy, and stakeholder expectations in promoting transparent and accountable digital management practices.

At the outcome level, the economic domain contributed most significantly to overall Smart Campus success (β = 0.416), indicating that efficiency gains, innovation capacity, and effective resource management are central to institutional advancement. The significant effects observed in the social, environmental, and governance domains further demonstrate that Smart Campus development is inherently multidimensional, integrating operational performance with social responsibility and sustainable practices.

The model demonstrated excellent overall fit (χ2/df = 1.16, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.017), confirming both theoretical coherence and empirical adequacy. Overall, these findings establish the TOE-based framework as a valid and practical approach for understanding the evolution and success of Smart Campus initiatives in higher education settings.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study adds to the growing body of research that applies the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework to digital transformation in higher education. The findings support previous research [

32,

33], demonstrating that technological capability, organizational readiness, and environmental pressures collectively influence institutional progress. The pronounced effect of organizational factors aligns with earlier studies that highlight the importance of leadership commitment, institutional culture, and structural support in fostering innovation and organizational change [

34,

35]. The positive influence of environmental conditions is consistent with research by [

36], which shows that regulatory frameworks and policy initiatives improve institutional responsiveness. Similarly, the notable impact of the economic domain supports the arguments of [

5,

37] that efficiency, innovation, and strategic resource management are essential for successful Smart Campus initiatives. Overall, these results reinforce the TOE framework by demonstrating the interaction between internal capacities and external conditions in driving digital transformation in higher education.

In addition to confirming established theoretical relationships, this study advances Smart Campus scholarship in several key ways. It offers one of the few empirical investigations in the Thai and broader ASEAN context that integrates the TOE framework with a second-order Smart University Success construct, which includes four sustainability-oriented performance dimensions: economic, social, environmental, and governance. Previous studies in the region have primarily examined technology readiness, isolated adoption factors, or single performance domains. This research expands the theoretical landscape by modeling TOE antecedents and multi-domain institutional performance within a unified structural framework.

The research also contributes conceptually by defining Smart University Success as a higher-order latent construct. This approach advances Smart Campus theory beyond the first-order or single-factor measurement models commonly used in previous empirical studies and enables a more comprehensive understanding of performance outcomes relevant to digital transformation.

Additionally, the study is strengthened by its use of institution-level data collected from senior administrators, offering a governance-level perspective that is seldom addressed in ASEAN Smart Campus research, which typically relies on student or faculty samples. This perspective enhances theoretical understanding of the influence of leadership decision-making and institutional capacity on Smart Campus development.

The study also enhances methodological rigor in TOE-based Smart Campus modeling by providing explicit sample adequacy justification through free-parameter calculations and RMSEA-based power analysis, as well as detailed reporting of estimation diagnostics. These methodological contributions clarify the reliability and validity of TOE applications in higher education and establish a more transparent foundation for future theoretical development.

Collectively, these contributions strengthen and extend the theoretical utility of the TOE framework for explaining multi-dimensional Smart Campus performance, particularly within higher education systems in developing countries experiencing rapid digital transformation.

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings offer actionable insights for policymakers and university leaders aiming to advance Smart Campus development in Thailand and other developing countries. The recommendations are directly informed by the structural equation modeling (SEM) results and reflect the relative strengths of the technology-organization-environment (TOE) dimensions and Smart Campus performance domains.

As organizational readiness was identified as the strongest predictor among the TOE factors, strategic efforts should focus on enhancing leadership capacity, internal coordination, and staff competencies. Organizational readiness can be cultivated through investment in digital skills development, leadership that prioritizes innovation, and participatory decision-making at all institutional levels. Collaboration with peer institutions, industry partners, and government agencies can further strengthen an ecosystem that supports digital transformation, sustainability, and effective governance.

The results also show that the economic domain exerted the greatest influence on overall Smart Campus success. This underscores the need for careful financial planning, evidence-based resource allocation, and investment strategies that link digital technologies—such as IoT systems, big data infrastructures, and cloud platforms—to clearly defined institutional priorities. Digital investments should not be evaluated solely on short-term efficiency gains but also on their contributions to long-term institutional resilience, research capacity, and sociMore broadly, the findings demonstrate that Smart Campus development requires a balanced approach integrating economic, social, environmental, and governance considerations. Universities that align digital transformation initiatives with sustainability objectives, inclusive community engagement, and transparent management practices are more likely to achieve meaningful and lasting benefits. The study underscores that Smart Campus success depends not only on technological innovation but also on the organizational capability and strategic vision necessary to translate digital tools into improved institutional performance.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable empirical insights, several limitations must be considered. First, the data were collected exclusively from Thai higher education institutions, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings to other national systems or policy environments. Another limitation involves the potential for common method bias, as data collection relied on a single self-report instrument completed by senior administrators. Although procedural remedies such as anonymity assurances, neutral wording, and separated questionnaire sections were implemented, the possibility of common method variance remains. Future research should utilize multi-source or multi-level data and expand the analysis to regional or cross-country contexts, particularly within ASEAN.

The use of a cross-sectional design in this study limits the ability to observe digital transformation processes over time. Employing longitudinal, mixed-method, or case-based approaches could yield deeper insights into the evolution of Smart Campus adoption across various institutional types. Although the TOE framework demonstrated strong performance, incorporating additional theories such as the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) or the Resource-Based View (RBV) may offer a more comprehensive theoretical perspective.

Another methodological consideration concerns the exceptionally high overall Cronbach’s alpha (0.992). While high internal consistency is anticipated in multidimensional instruments, such values may suggest item redundancy or limited uniqueness. Diagnostic checks indicated that item deletion did not reduce alpha or substantially increase average variance extracted (AVE) or composite reliability, and AVE values (0.60–0.69) confirmed adequate discrimination relative to error variance. Nonetheless, future research could refine or shorten item sets and apply exploratory techniques to optimize scale structure.

A further limitation pertains to the structural model. All hypothesized paths (H1–H16) were significant, which, although theoretically consistent, requires cautious interpretation since complex social-science models seldom yield uniformly significant coefficients. Future research should conduct additional robustness checks, including mediation analysis, common-latent-factor assessments, reverse-causality tests, or comparisons with alternative model specifications.

Finally, although the study employs causal terminology grounded in theory, the cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inference. The estimated structural relationships should therefore be interpreted as correlational patterns consistent with the theoretical model. Longitudinal or experimental designs are necessary to establish temporal precedence and confirm causal directions.

6. Conclusions

A causal model was developed and empirically tested to explain the factors influencing Smart Campus success in Thailand, utilizing the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework as the theoretical foundation. Based on responses from 96 senior university administrators, the results indicate that technological capability, organizational readiness, and environmental support collectively enhance four core performance domains: economic, social, environmental, and governance, which together define Smart Campus success.

All sixteen hypotheses (H1–H16) were supported, and the structural model demonstrated strong fit (χ2/df = 1.16, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.980, RMSEA = 0.059, SRMR = 0.017). Among the TOE dimensions, organizational readiness exerted the greatest influence, highlighting the importance of leadership, institutional culture, and preparedness in facilitating digital transformation. Environmental factors, including government policy and stakeholder expectations, contributed to sustainable governance and effective resource management, while technological capability remained critical for innovation, efficiency, and system integration.

Among the four domains, the economic factor contributed most significantly to Smart Campus success (β = 0.416), emphasizing the importance of efficiency improvements, innovation ecosystems, and strategic resource allocation for long-term competitiveness and sustainability. These findings extend the TOE framework by demonstrating that Smart Campus development requires a balance between internal readiness and external support, resulting in multidimensional performance outcomes.

The results provide actionable guidance for policymakers and university leaders. Effective Smart Campus strategies should integrate technological investment, organizational development, and external collaboration. These approaches can produce sustainable, data-driven systems that improve learning, governance, and institutional capacity.

In conclusion, this research presents a validated conceptual model and offers both theoretical and practical insights for advancing Smart Campus transformation in Thailand and other higher-education systems pursuing sustainable digital evolution.