A Comparative Analysis of the Regional Integrated Rice–Crayfish Systems Based on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Huoqiu County and Chongming District in China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

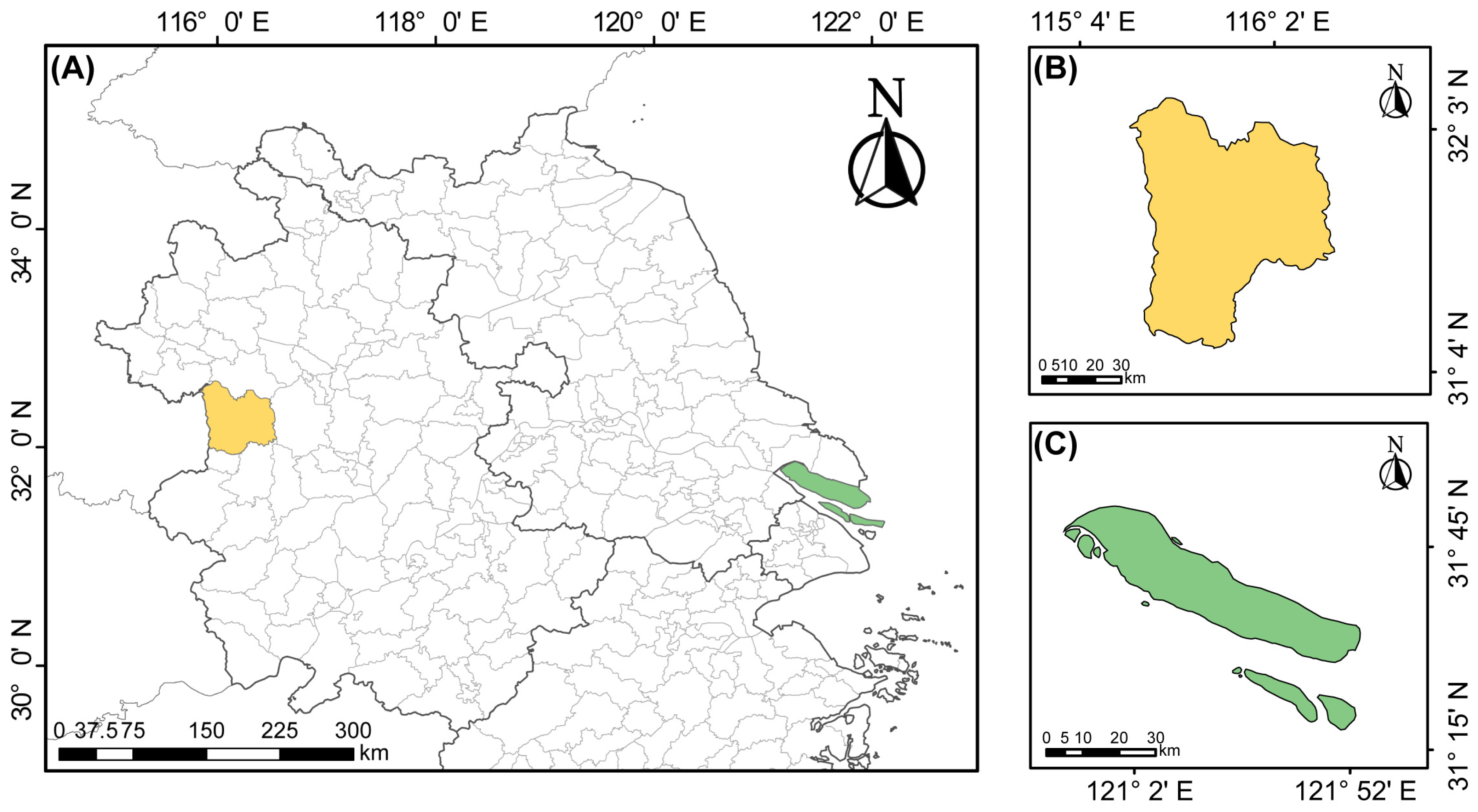

2.1. Study Areas and Descriptions

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Primary Data Collection and Survey Research

2.2.2. Secondary Data Collection

2.3. ESVs Evaluation Framework

2.4. SWOT-AHP Model

3. Results

3.1. Provisioning Service

3.2. Regulation and Maintenance Service

3.2.1. Carbon Sequestration and Oxygen Release Value

3.2.2. Greenhouse Gas Emissions Value

3.2.3. Temperature Regulation Value

3.2.4. Water Storage and Flood Control Value

3.2.5. Pest Control Value

3.2.6. Air Purification Value

3.2.7. Biodiversity Maintenance Value

3.2.8. Soil Nutrient Retention Value

3.3. Cultural Service

3.3.1. Tourism Development Value

3.3.2. Social Security Value

3.3.3. Brand Development for Rice–Crayfish Products Value

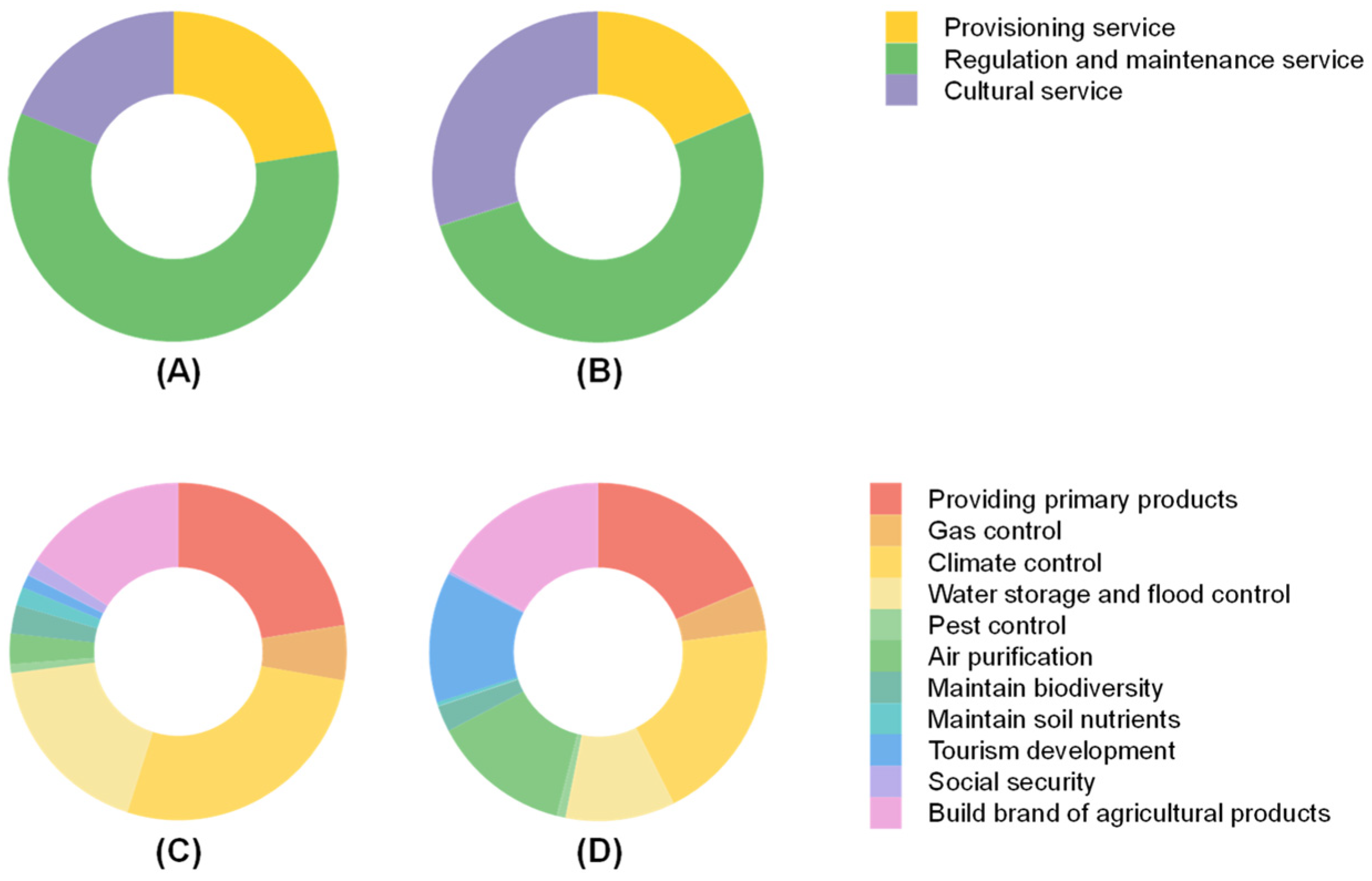

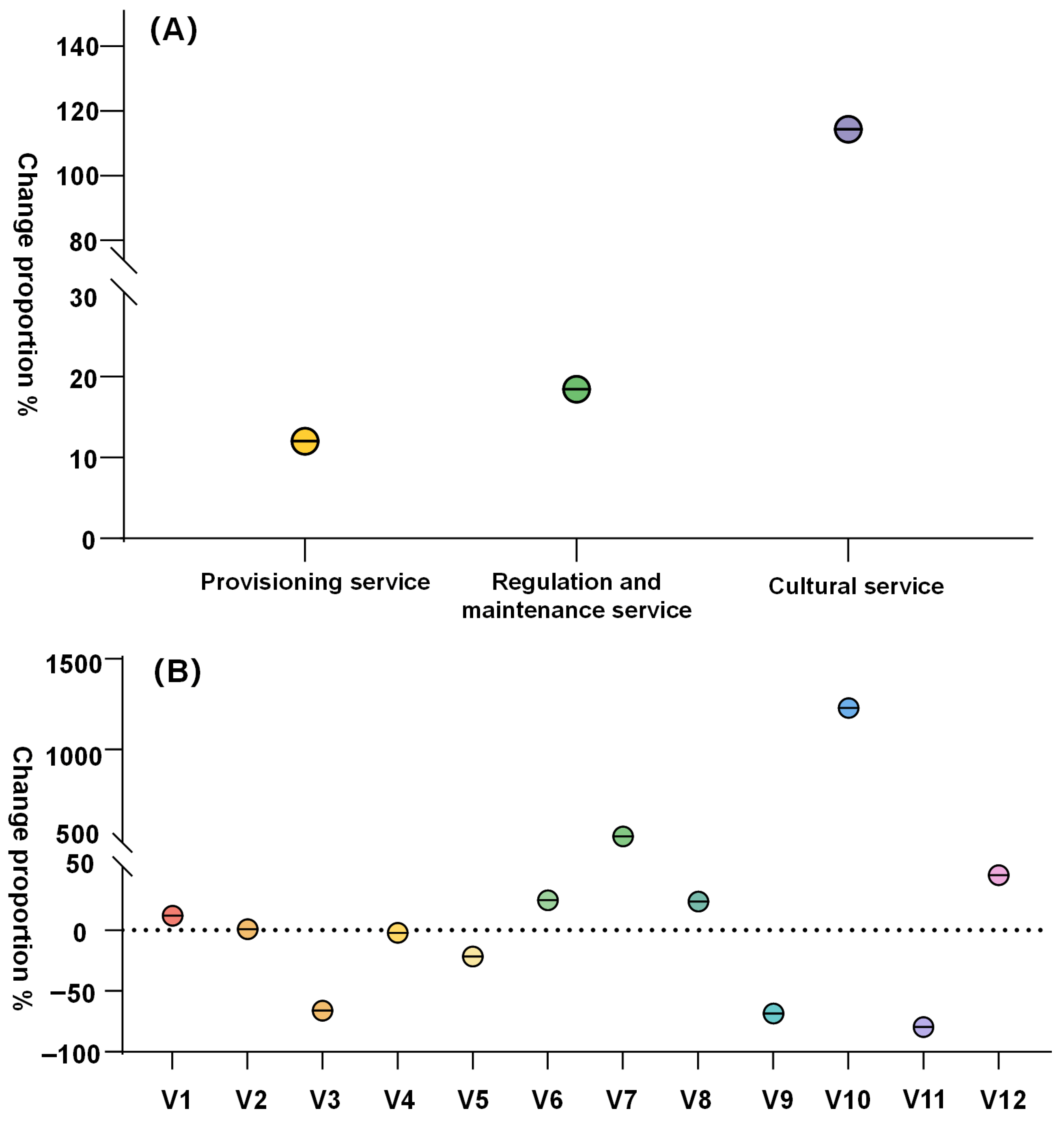

3.4. Comparison of Rice–Crayfish ESVs Between HQ and CM

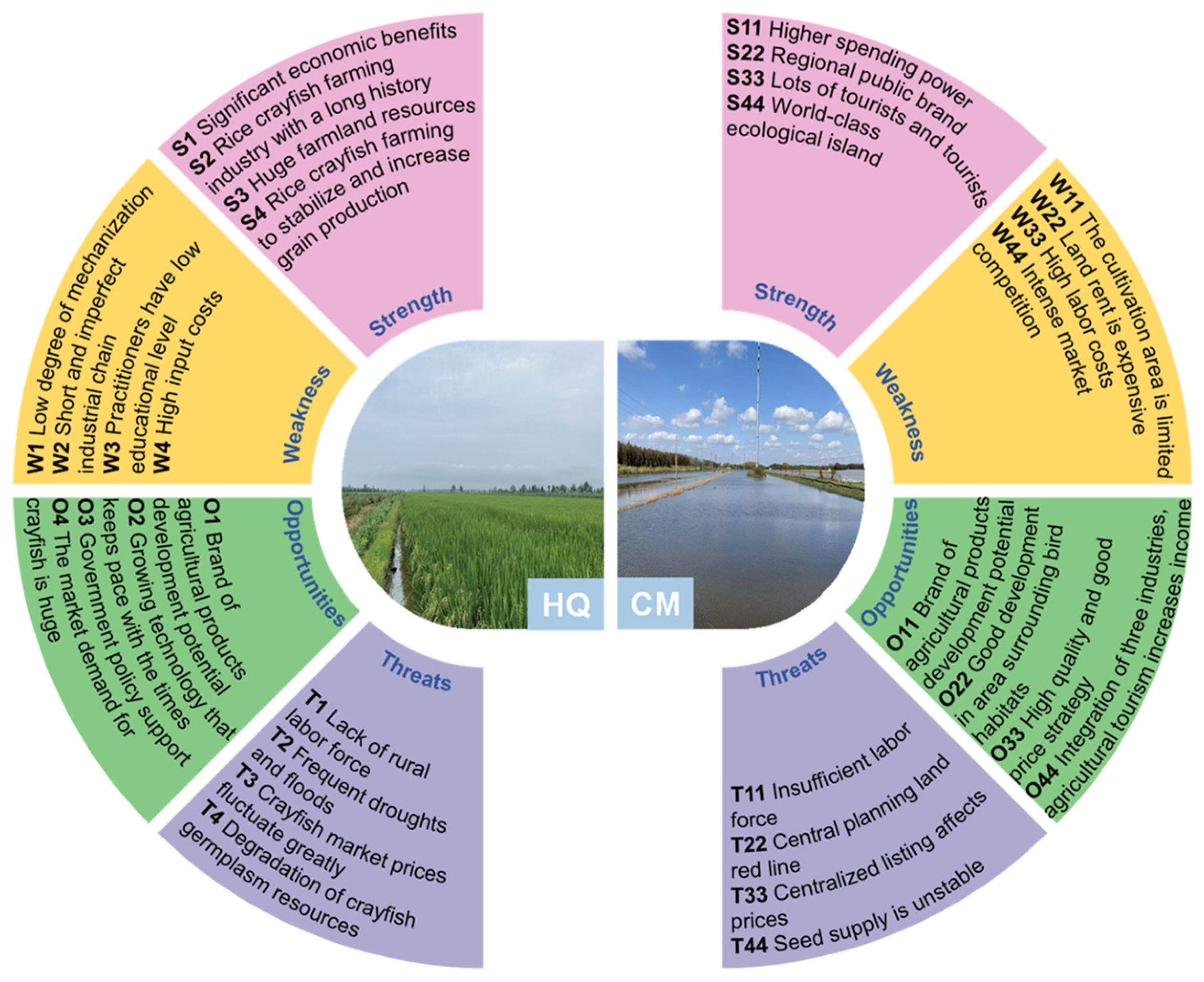

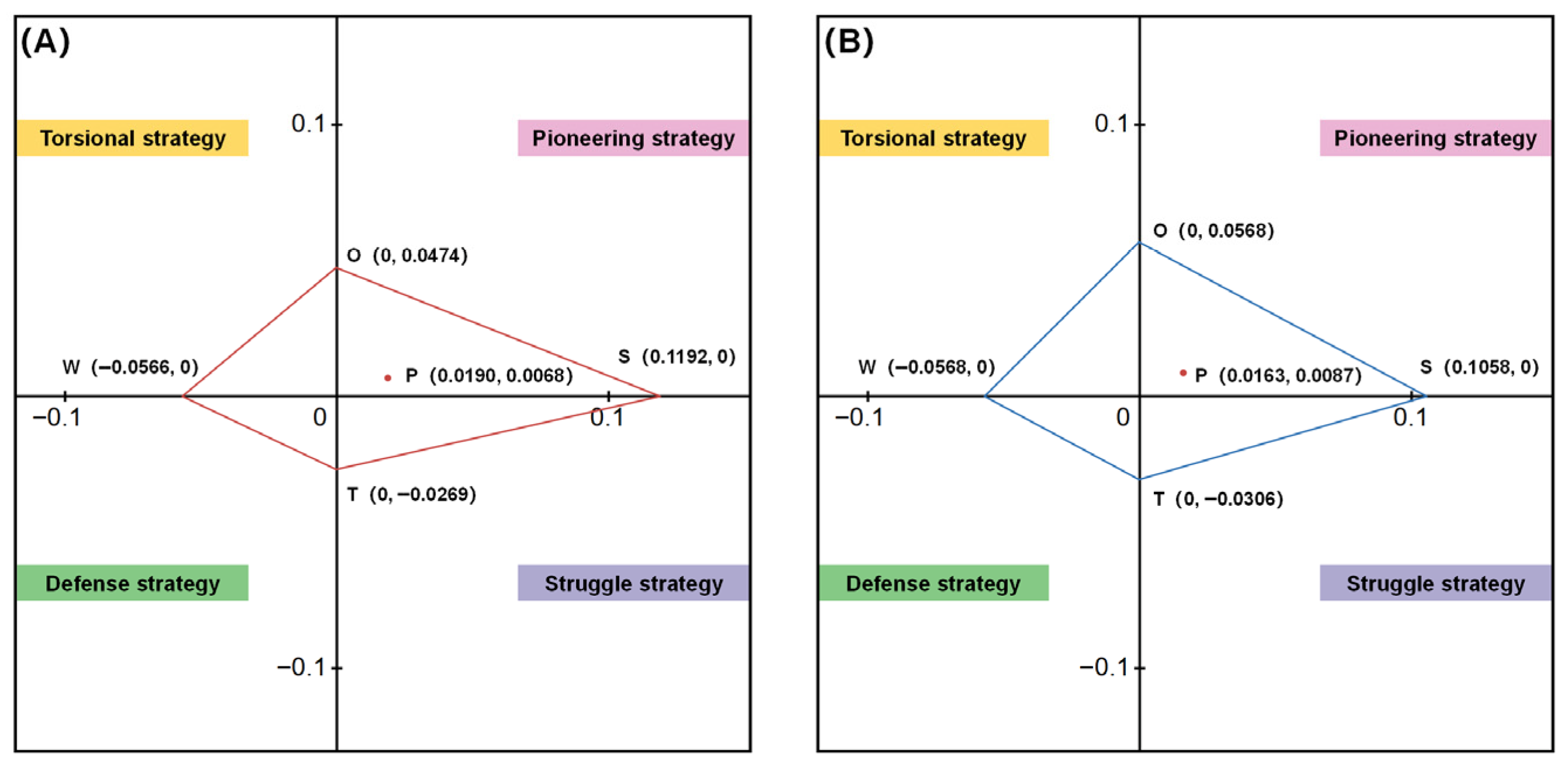

3.5. SWOT-AHP Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Regional Variations in the ESVs Type in HQ and CM

4.2. The Differences in ESVs Function Between HQ and CM

4.3. SWOT-AHP Analysis of HQ and CM

4.4. Sustainable Development Suggestions for Rice–Crayfish Farming in HQ and CM

- (1)

- Enhance Land Use Efficiency: Leverage extensive farmland by optimizing rice–crayfish rotation systems, and integrate high-value crops such as lotus root and water bamboo. This strategy directly enhances provisioning service value (from 77,762.06 CNY/ha) by diversifying agricultural outputs and increasing economic returns. Moreover, by promoting integrated crop management, it can reduce reliance on external pesticides and fertilizers, thereby improving the pest control service (valued at 3021.45 CNY/ha) and mitigating potential water pollution.

- (2)

- Strengthen Branding for Enhanced Market Value: Despite the national geographical indication for “Huoqiu Crayfish”, associated rice products lack recognition. Developing distinctive rice brands through strategic marketing is crucial. This can significantly increase the market price of rice, directly elevating the brand of agricultural products service (valued at 54,893.16 CNY/ha) and strengthening the social security function (valued at 5632.35 CNY/ha) by improving local farmer incomes.

- (3)

- Improve Market Infrastructure to Maximize Product Value: Establish centralized trading markets and cold chain logistics to enhance crayfish preservation and transport. Promote deep processing (e.g., crayfish tails and seasonings) to increase product value. These improvements not only boost the economic dimension of provisioning service but also support rural employment, further reinforcing the social security function, which already occupies a secondary position (22%) in HQ.

- (1)

- Integrate Ecotourism with Ecological Safeguards: Capitalize on the proximity to Dongtan Wetland Park by linking rice–crayfish systems with bird habitat conservation and tourism. This approach aims to further elevate the tourism development value already identified in CM (58,363.64 CNY/ha). However, this expansion must be carefully managed to avoid negative impacts. It is crucial to implement visitor capacity limits, establish designated ecological buffer zones, and use tourism revenue to fund habitat restoration. These cautionary measures will prevent disturbance to bird populations and protect the regulation service, such as biodiversity maintenance (valued at 11,667.77 CNY/ha).

- (2)

- Develop Premium Brands Based on Eco-Certification: Adhere strictly to “no chemical fertilizers or pesticides” standards to create premium, eco-certified rice and crayfish brands. This strategy directly leverages CM’s strength in environmental quality, justifying a higher market price that enhances brand of agricultural products value (79,674.40 CNY/ha).

- (3)

- Optimize Policy Support for Eco-Compensation: Policies should be designed to directly reward farmers for management practices that enhance specific ESVs, such as subsidies for maintaining deeper water levels to support the habitat of waterfowl to enhance the biodiversity value (11,667.77 CNY/ha). This turns policy support from a general incentive into a direct eco-compensation mechanism, better balancing ecological and economic benefits.

4.5. Mechanisms Linking ASS to Industrial Service Optimization

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESVs | Ecosystem service values |

| CICES | Common international classification of ecosystem services |

| ES | Ecosystem services |

| ESV | Ecosystem service valuation |

| HQ | Huoqiu County |

| CM | Chongming District |

| IAA | Integrated agriculture–aquaculture |

| AHP | Analytic Hierarchy Process |

| LCA | Life cycle assessment |

| ASS | Agricultural socialized services |

| GHG | Greenhouse gas |

| CR | Consistency ratio |

| GWP | Global warming potential |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| AR6 | Sixth Assessment Report |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| HF | Hydrogen fluoride |

| CVM | Contingent valuation method |

References

- Kiptala, J.K.; Mul, M.; Mohamed, Y.; Bastiaanssen, W.G.M.; Van Der Zaag, P. Mapping Ecological Production and Benefits from Water Consumed in Agricultural and Natural Landscapes: A Case Study of the Pangani Basin. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getzner, M.; Islam, M.S. Ecosystem Services of Mangrove Forests: Results of a Meta-Analysis of Economic Values. IJERPH 2020, 17, 5830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X. Spatial-Temporal Variation of the Ecosystem Services Value (ESV) in the Yellow River Delta Wetland and Its Response to Land Use/Land Cover Changes (Lu/Lc). J. Freshw. Ecol. 2024, 39, 2419371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Thenen, M.; Frederiksen, P.; Hansen, H.S.; Schiele, K.S. A Structured Indicator Pool to Operationalize Expert-Based Ecosystem Service Assessments for Marine Spatial Planning. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 187, 105071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zepp, H.; Falke, M.; Günther, F.; Gruenhagen, L.; Inostroza, L.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Q.; Dong, N. China’s Ecosystem Services Planning: Will Shanghai Lead the Way? A Case Study from the Baoshan District (Shanghai). Erdkunde 2021, 75, 271–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdain, D.; Vivithkeyoonvong, S. Valuation of Ecosystem Services Provided by Irrigated Rice Agriculture in Thailand: A Choice Experiment Considering Attribute Nonattendance. Agric. Econ. 2017, 48, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natuhara, Y. Ecosystem Services by Paddy Fields as Substitutes of Natural Wetlands in Japan. Ecol. Eng. 2013, 56, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Huang, G. Effects of combined application of Chinese Milk Vetch (Astragalus sinicus L.) and nitrogen fertilizer on ecological service function of paddy field. J. Nat. Resour. 2018, 33, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.D. Rice Intensive Cropping and Balanced Cropping in the Mekong Delta, Vietnam—Economic and Ecological Considerations. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 132, 205–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangopadhyay, S.; Banerjee, R.; Batabyal, S.; Das, N.; Mondal, A.; Pal, S.C.; Mandal, S. Carbon Sequestration and Greenhouse Gas Emissions for Different Rice Cultivation Practices. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 34, 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Mo, M.; Xie, Y.; Liao, Q. Impacts of Different Tourism Models on Rural Ecosystem Service Value in Ziquejie Terraces. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Méndez, N.; Alcaraz, C.; Catala-Forner, M. Ecological Restoration of Field Margins Enhances Biodiversity and Multiple Ecosystem Services in Rice Agroecosystems. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2025, 382, 109484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Hu, H.; Hu, J.; Yang, Z.; Lv, Q.; Wang, Y.; Yan, B.; Ren, X.; Hu, S. Ecosystem Services and Cost-Effective Benefits from the Reclamation of Saline Sodic Land under Different Paddy Field Systems. Ecosyst. Serv. 2024, 70, 101682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Styles, D.; Cao, Y.; Ye, X. The Sustainability of Rice-Crayfish Coculture Systems: A Mini Review of Evidence from Jianghan Plain in China. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 3843–3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, N.; Liu, C.; Chen, Q.; Zhu, L. Life Cycle Environmental Impact Assessment of Rice-Crayfish Integrated System: A Case Study. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, P.; Wang, H.; Sun, G.; Xu, Q.; Dou, Z.; Dong, E.; Wu, W.; Dai, Q. Integrated Emergy and Economic Evaluation of the Dominant Organic Rice Production Systems in Jiangsu Province, China. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1107880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Dai, L.; Gao, P.; Dou, Z. The Environmental, Nutritional, and Economic Benefits of Rice-Aquaculture Animal Coculture in China. Energy 2022, 249, 123723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Li, C.; Tan, W.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Hu, Q.; Cao, C. Rice-Crayfish Co-Culture Reduces Ammonia Volatilization and Increases Rice Nitrogen Uptake in Central China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 330, 107869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Du, L.; Xiao, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, P.; Sun, G.; Ye, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, H. Rice-Crayfish Farming Increases Soil Organic Carbon. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2022, 329, 107857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Liu, T.; Guo, H.; Dou, Z.; Gao, H.; Zhang, H. Conversion from Rice–Wheat Rotation to Rice–Crayfish Coculture Increases Net Ecosystem Service Values in Hung-Tse Lake Area, East China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 319, 128883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, W.; Fuller, A.; Xu, S.; Min, Q.; Wu, M. Socio-Ecological Adaptation of Agricultural Heritage Systems in Modern China: Three Cases in Qingtian County, Zhejiang Province. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Zhao, G.; Liang, L.; Chen, B. Achieving Higher Eco-Efficiency for Three Staple Food Crops with Ecosystem Services Based on Regional Heterogeneity in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 948, 174942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull, J.W.; Jobstvogt, N.; Böhnke-Henrichs, A.; Mascarenhas, A.; Sitas, N.; Baulcomb, C.; Lambini, C.K.; Rawlins, M.; Baral, H.; Zähringer, J.; et al. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats: A SWOT Analysis of the Ecosystem Services Framework. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunting, S.W.; Kundu, N.; Ahmed, N. Evaluating the Contribution of Diversified Shrimp-Rice Agroecosystems in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India to Social-Ecological Resilience. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyana, R.; Amalia, R.; Salsabilah, D.S.; Uka, A.S.; Rilisa, C.; Gunawan, W. Strategy for Increasing Lowland Rice Productivity in West Java Province with the SWOT-AHP Model Approach. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 457, 012058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahowski, R.T.; Li, X.; Davidson, C.L.; Wei, N.; Dooley, J.J.; Gentile, R.H. A Preliminary Cost Curve Assessment of Carbon Dioxide Capture and Storage Potential in China. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 2849–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Xie, Q.; Ye, P. Research on the law of greenhouse gas emissions from rice fields under the rice-shrimp planting and breeding model. Hubei Agric. Sci. 2023, 62, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, M.; Peng, C.; Si, G.; Zhou, J.; Xie, Y.; Yuan, J. Effect of rice-crayfish co-culture on greenhouse gases emission in straw-puddled paddy fields. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2017, 25, 1591–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, S.; Zhang, F.; Feng, Y.; Duan, C.; Tong, Y. Characteristics of Evapotranspiration and Its Influencing Factors in Rice-wheat Rotation in the Jianghuai River Basin. Water Sav. Irrig. 2020, 8, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X.; Sun, G.; Ren, Z. The values of vegetation purified air and its measure in Xin’an city. Arid. Land. Resour. Environ. 2002, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, C. The value of ecosystem services in China. Resour. Sci. 2015, 37, 1740–1746. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, K.; Tian, J.; Xie, J. Ecosystem Services Analysis for Sustainable Agriculture Expansion: Rice-Fish Co-Culture System Breaking through the Hu Line. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 133, 108385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikstra, J.S.; Nicholls, Z.R.J.; Smith, C.J.; Lewis, J.; Lamboll, R.D.; Byers, E.; Sandstad, M.; Meinshausen, M.; Gidden, M.J.; Rogelj, J.; et al. The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report WGIII Climate Assessment of Mitigation Pathways: From Emissions to Global Temperatures. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2022, 15, 9075–9109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krochta, M.; Chang, H. Reviewing Controls of Wetland Water Temperature Change across Scales and Typologies. Prog. Phys. Geogr. Earth Environ. 2025, 49, 144–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Zhang, S. Ecosystem Service Decline in Response to Wetland Loss in the Sanjiang Plain, Northeast China. Ecol. Eng. 2019, 130, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.-J.; Zhao, L.-F.; Zhang, T.-J.; Dai, R.-X.; Tang, J.-J.; Hu, L.-L.; Chen, X. Coculturing Rice with Aquatic Animals Promotes Ecological Intensification of Paddy Ecosystem. J. Plant Ecol. 2023, 16, rtad014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Xie, G. Comprehensive valuation of the ecosystem services of rice paddies in Shanghai. Resour. Sci. 2009, 31, 38–47. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yu, X.; Jiang, L.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Hou, X. How Important Are the Wetlands in the Middle-Lower Yangtze River Region: An Ecosystem Service Valuation Approach. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 10, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Tang, R.; Xie, J.; Tian, J.; Shi, R.; Zhang, K. Valuation of Ecosystem Services of Rice–Fish Coculture Systems in Ruyuan County, China. Ecosyst. Serv. 2020, 41, 101054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhang, X.; Shen, W.; Yao, H.; Meng, X.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, G.; Zamanien, K. A Meta-Analysis of Ecological Functions and Economic Benefits of Co-Culture Models in Paddy Fields. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2023, 341, 108195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelis, A.K.; Walton, W.C.; Webster, D.W.; Shaffer, L.J. The Role of Ecosystem Services in the Decision to Grow Oysters: A Maryland Case Study. Aquaculture 2020, 529, 735633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Wang, X.; Yan, L.; Yi, J.; Xia, T.; Zeng, Z.; Yu, G.; Chai, M. Mapping Rice-Crayfish Co-Culture (RCC) Fields with Sentinel-1 and -2 Time Series in China’s Primary Crayfish Production Region Jianghan Plain. Sci. Remote Sens. 2024, 10, 100151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.; Dai, W.; Shang, Z.; Guo, R. Review of research progress on the influence and mechanism of field straw residue incorporation on soil organic matter and nitrogen availability. Chin. J. Eco-Agric. 2013, 21, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Gao, M.; Li, Z. Impacts of Straw Return Methods on Crop Yield, Soil Organic Matter, and Salinity in Saline-Alkali Land in North China. Field Crops Res. 2025, 322, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, S.; Yao, B.; Peng, Y.; Gao, C.; Qin, T.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, C.; Quan, W. Effects of Straw Return and Straw Biochar on Soil Properties and Crop Growth: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 986763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Gu, X.; Wang, Y.; Gao, H.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Sun, S. Impact of Straw Return on Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Maize Fields in China: Meta-Analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1493357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Wei, C.; Song, L. Application of five- element connection number method- improved entropy method in water quality evaluation. South—North. Water Transf. Water Sci. Technol. 2015, 13, 268–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Xia, G. Study on characteristics and causation of waterlog disaster of waterlogging depressions along mid-reach of Huaihe Rive. Water Resour. Hydropower Eng. 2012, 43, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grima, N.; Jutras-Perreault, M.-C.; Gobakken, T.; Ole Ørka, H.; Vacik, H. Systematic Review for a Set of Indicators Supporting the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 147, 109978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Li, Z.; Shao, L.; Zhao, X.; Chu, J.; Yu, F. Impact of Different Modes of Comprehensive Rice Field Planting and Aquaculture Systems in Paddy Fields on Rice Yield, Quality, and Economic Benefits. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2025, 34, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Peng, X.; Guo, H.; Che, Y.; Dou, Z.; Xing, Z.; Hou, J.; Styles, D.; Gao, H.; Zhang, H. Rice-Crayfish Coculture Delivers More Nutrition at a Lower Environmental Cost. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 29, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minot, N. Contract Farming in Developing Countries: Patterns, Impact, and Policy Implications; Cornel University: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon, T.; Echeverria, R.; Berdegué, J.; Minten, B.; Liverpool-Tasie, S.; Tschirley, D.; Zilberman, D. Rapid Transformation of Food Systems in Developing Regions: Highlighting the Role of Agricultural Research & Innovations. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaux, A.; Torero, M.; Donovan, J.; Horton, D. Agricultural Innovation and Inclusive Value-Chain Development: A Review. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 8, 99–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Chi, Z.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Peng, L. Boosting Agricultural Green Development: Does Socialized Service Matter? PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0306055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, T. Can Agricultural Socialized Services Promote the Reduction in Chemical Fertilizer? Analysis Based on the Moderating Effect of Farm Size. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Formula | Parameter Specification |

|---|---|

| V1 = Yr × Pr + Yf × Pf | V1 represents the value of primary product provision (CNY/ha); Yr and Yf denote the yields of rice and crayfish, respectively, which are 8509.97 (N = 200, sigma = 2168) and 1240.64 kg/ha (N = 200, sigma = 450) in HQ, and 8595.24 (N = 15, sigma = 1343) and 1446.38 kg/ha (N = 15, sigma = 428) in CM; and Pr and Pf are the market prices of rice and crayfish, respectively: 2.14 (N = 200, sigma = 0.21) and 24.00 CNY/kg (N = 200, sigma = 5.23) in HQ, and 2.88 (N = 15, sigma = 0.14) and 40.42 (N = 15, sigma = 19) CNY/kg in CM. |

| V2 = V21 + V22 V21 = (Y × (1 − w))/f × α × Nc × PCO2 V22 = (Y × (1 − w))/f × β × PO2 | V2 refers to the value of carbon sequestration and oxygen release (CNY/ha), where V21 and V22 denote the values of carbon sequestration and oxygen release, respectively. Y is the rice yield (kg/ha); w is the moisture content of rice (13.5%); f is the economic conversion coefficient for rice crops (0.50); α is the amount of CO2 absorbed per gram of rice dry matter (1.63 g); Nc is the carbon content of CO2; β is the amount of O2 produced per gram of rice dry matter (1.9 g); PCO2 is the cost of afforestation (CNY/t C); and PO2 is the cost of industrial oxygen production (CNY/t O2). |

| V3 = RC × PCO2 RC = 12/44 × (29.8 × ECH4 + 273 × EN2O + ECO2) | V3 denotes the value of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (CNY/ha); PCO2 is the afforestation cost (CNY/t C); RC is the CO2-equivalent value converted from CH4 and N2O using global warming potential (kg/ha); ECH4 is the CH4 emission (850.84 and 117.65 kg/ha); EN2O is the N2O emission (0.58 and 0.87 kg/ha); and ECO2 is the CO2 emission (6927.10 kg/ha). |

| V4 = SZF × d × μ × PM | V4 represents the value of temperature regulation (CNY/ha); SZF is the average daily evaporation per hectare (3.22 mm/d/ha); d is the number of days per year with temperatures above 30 °C (50 and 49 days); μ is the equivalent amount of coal (t) required to evaporate 50 mm of water; and PM is the price of standard coal (CNY/t). |

| V5 = (H × (1 − μ) × S + μ × S × (H + h)) × PSK | V5 refers to the value of water storage and flood control (CNY/ha); H is the average height of bunds (0.79 and 0.69 m); μ is the proportion of trenching area in integrated rice–crayfish farming (7.88% and 0.00%); S is the unit area (ha); h is the trench depth (1.14 m); and PSK is the unit cost of reservoir projects (CNY/m3). |

| V6 = β × CP | V6 denotes the value of pest control (CNY/ha); β is the reduction in pesticide and fertilizer use (kg/ha) compared to monoculture; and CP is the average local pesticide price (CNY/kg). |

| V7 = PSO2× QSO2+ PNOX × QNOX + PHF × QHF + PS × QS | V7 represents the value of air purification (CNY/ha); PSO2, PNOX, PHF, and PS are the unit costs for removing SO2, NOx, HF, and particulate matter in forestry (CNY/t); and QSO2, QNOX, QHF, and QS are the average annual fluxes absorbed by rice paddies (t/year). |

| V8 = α × Erf | V8 denotes the value of biodiversity maintenance (CNY/ha); α is the value equivalence factor for the rice field ecosystem (0.21); and Erf is the weighted average income from local cash crops (CNY/ha). |

| V9 = PSOC × (ISOC − OSOC) ISOC = Nr × 5 × Cr + Ns × Cs OSOC = RCO2 × 0.27 + RCH4 × 0.75 | V9 refers to the value of soil nutrient retention (CNY/ha); PSOC is the market price of organic fertilizer (CNY/kg C); ISOC and OSOC represent the input and output of soil organic carbon (kg C/ha), respectively; Nr is the root biomass of rice (1312.97 and 1326.12 kg/ha); Cr is the carbon content in rice roots (39.21%); Ns is the rice straw biomass (9190.77 and 9282.86 kg/ha); Cs is the carbon content in straw (33.21%); and RCO2 and RCH4 are the CO2 and CH4 emissions, respectively (kg/ha). |

| V10 = (Nd/Nz) × Rz/Sd | V10 is the value of tourism development (CNY/ha); Nd is the number of visitors to the Lotus Festival in HQ or Dongtan Wetland Park in CM (5.00 and 18.80 × 104 person-times); Nz is the annual total number of tourists in each region (335.00 and 1899.00 × 104 person–times); Rz is the total tourism revenue (15.70 and 50.70 billion CNY/year); Sd is the area of Chengxi Lake or Dongtan Wetland Park (5333.33 and 860 ha). |

| V11 = (N × M × R)/Sd | V11 represents the value of social security (CNY/ha/year); N is the number of rural minimum subsistence allowance recipients (49,821 and 12,280 people); M is the minimum living allowance standard (659.00 and 1330.00 CNY/year); R is the consumption ratio between rural and urban residents (0.67 and 0.83); and Sd is the total area of integrated rice–crayfish farming in each region (ha). |

| V12 = Pr1 × w × Yr1 + Pf1 × Yf1 | V12 is the value of brand development for rice–crayfish products (CNY/ha); Pr1 is the price premium for rice (4.00 and 7.50 CNY/kg); w is the average milling yield of rice (66.50%); Yr1 is the rice yield (kg/ha); Pf1 is the price premium for crayfish (26.00 and 23.58 CNY/kg); and Yf1 is the crayfish yield (kg/ha). |

| Section | Ecosystem Services of the Rice–Crayfish System | Assessment of Indicators | To Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning (Biotic) | 1. Rice and crayfish harvested provide food and nutrition | providing primary products | V1 |

| Regulation and Maintenance (Biotic) | 2. Increase in fauna diversity and microorganisms | maintain biodiversity | V8 |

| 3. Reducing pesticides and herbicides | pest control | V6 | |

| 4. Reducing land abandonment | × | ||

| 5. Improving soil salinization | × | ||

| 6. Saving water source | × | ||

| 7. Recharging groundwater | water storage and flood control | V5 | |

| 8. Energy losses and expenditure for irrigation | × | ||

| 9. Crop transpiration and farmland evaporation | climate control | V4 | |

| 10. Enhancing humidification and rain | × | ||

| 11. Carbon dioxide fixation from photosynthesis | carbon fixation and oxygen release | V2 | |

| 12. Oxygen release from rice photosynthesis | |||

| 13. Rice absorbs SO2, HF, NOx, and dust | air purification | V7 | |

| 14. Greenhouse gas emissions | greenhouse gas emissions | V3 | |

| 15. Nutrition cycle and organic accumulation | maintain soil nutrients | V9 | |

| Cultural (Biotic and Abiotic) | 16. Securing the rural poor | social security | V11 |

| 17. Cultural value and heritage | × | ||

| 18. Artistic inspiration: theater, painting, and sculpture | × | ||

| 19. Willingness to preserve for future generations | × | ||

| 20. Development of tourism | tourism development | V10 | |

| 21. Experiential use of plants, animals, and land | × | ||

| 22. Education opportunities | × | ||

| 23. Research subject | × | ||

| 24. Build brand of agricultural products | build brand of agricultural products | V12 |

| Type of Service | HQ (CNY/ha/Year) | CM (CNY/ha/Year) |

|---|---|---|

| Provisioning service | 77,762.06 | 87,116.69 |

| Regulation and maintenance service | 203,432.36 | 241,028.92 |

| Cultural service | 64,919.17 | 139,189.28 |

| Total value | 346,113.59 | 467,334.89 |

| Type of Service | Function of Service | HQ (CNY/ha/Year) | CM (CNY/ha/Year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provisioning service | providing primary products | 77,762.06 | 87,116.69 |

| Regulation and maintenance service | carbon fixation and oxygen release | 20,805.06 | 21,013.52 |

| greenhouse gas emissions | −2524.68 | −858.11 | |

| climate control | 93,894.57 | 92,016.68 | |

| water storage and flood control | 62,556.06 | 49,059.00 | |

| pest control | 3021.45 | 3765.00 | |

| air purification | 10,059.44 | 62,413.03 | |

| maintain biodiversity | 9443.14 | 11,667.77 | |

| maintain soil nutrients | 6177.32 | 1952.03 | |

| Cultural service | tourism development | 4393.66 | 58,363.64 |

| social security | 5632.35 | 1151.24 | |

| build brand of agricultural products | 54,893.16 | 79,674.40 | |

| Total value | 346,113.59 | 467,334.89 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lou, B.; Qian, C.; Cai, X.; Cheng, Z.; Xi, Y.; Pan, Q.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Li, J. A Comparative Analysis of the Regional Integrated Rice–Crayfish Systems Based on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Huoqiu County and Chongming District in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411047

Lou B, Qian C, Cai X, Cheng Z, Xi Y, Pan Q, Li J, Zhang Z, Li J. A Comparative Analysis of the Regional Integrated Rice–Crayfish Systems Based on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Huoqiu County and Chongming District in China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411047

Chicago/Turabian StyleLou, Bingbing, Chen Qian, Xiangzhi Cai, Zeyi Cheng, Yewen Xi, Qiqi Pan, Jinghao Li, Zhaofang Zhang, and Jiayao Li. 2025. "A Comparative Analysis of the Regional Integrated Rice–Crayfish Systems Based on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Huoqiu County and Chongming District in China" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411047

APA StyleLou, B., Qian, C., Cai, X., Cheng, Z., Xi, Y., Pan, Q., Li, J., Zhang, Z., & Li, J. (2025). A Comparative Analysis of the Regional Integrated Rice–Crayfish Systems Based on Ecosystem Service Value: A Case Study of Huoqiu County and Chongming District in China. Sustainability, 17(24), 11047. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411047