Optimal µ-PMU Placement and Voltage Estimation in Distribution Networks: Evaluation Through Multiple Case Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Two state-of-the-art optimization techniques are utilized to determine the OPP while considering practical constraints. A single µ-PMU outage and ZIBs are considered practical constraints for a comprehensive study.

- ZIBs aid in reducing the required number of µ-PMUs while ensuring observability; hence, strategically placing µ-PMUs by leveraging ZIBs reduces µ-PMUs. Therefore, this condition is explored in this study to decrease the number of µ-PMUs and hence the overall placement cost. When a single µ-PMU fails to operate at a specific bus, it may cause a loss of critical data. Therefore, a case study examining a single µ-PMU failure and its potential impact on cost is also considered.

- After the placement, the WLS algorithm is employed for voltage estimation to ensure that strategically installed µ-PMUs measure the voltage estimation correctly for all case studies.

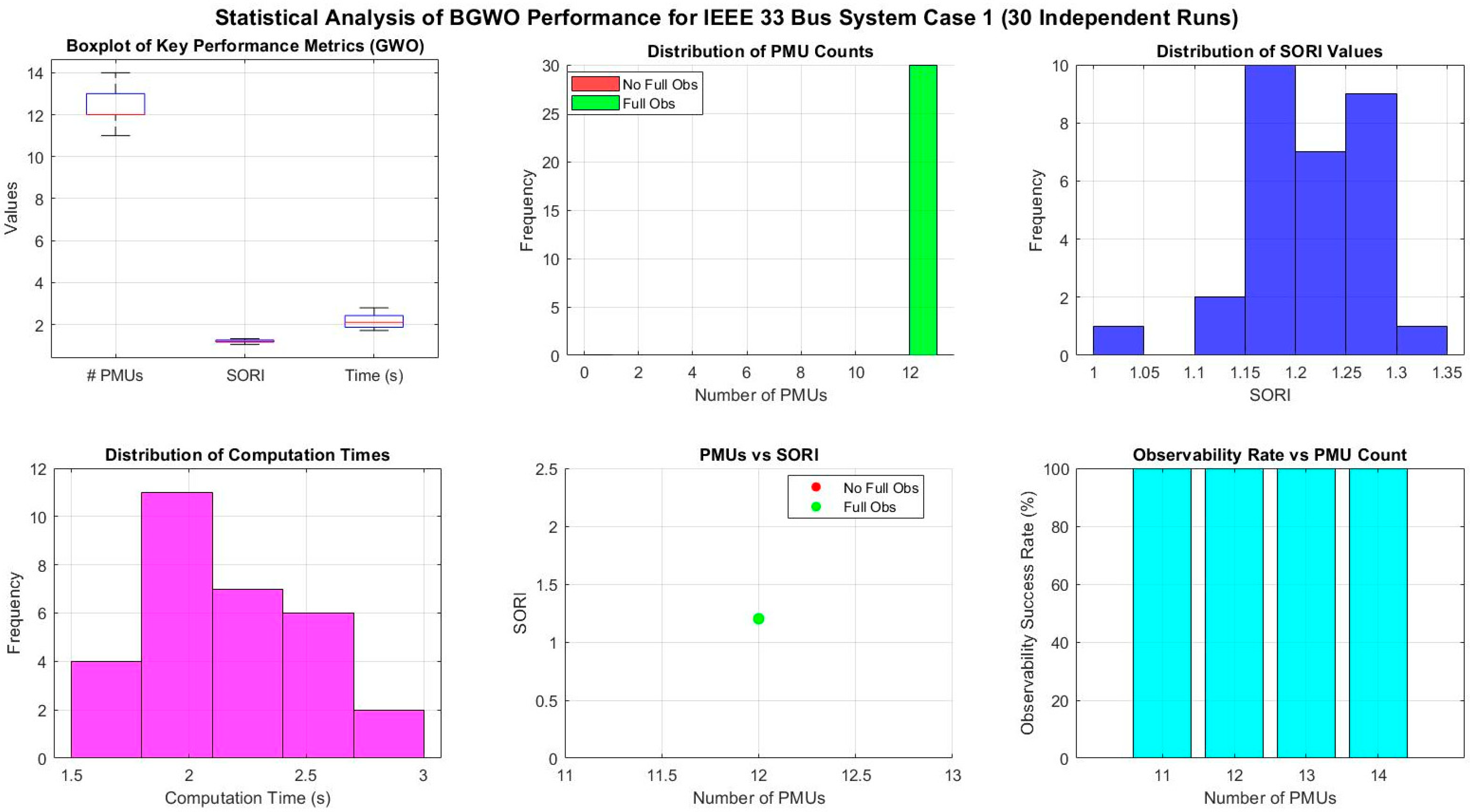

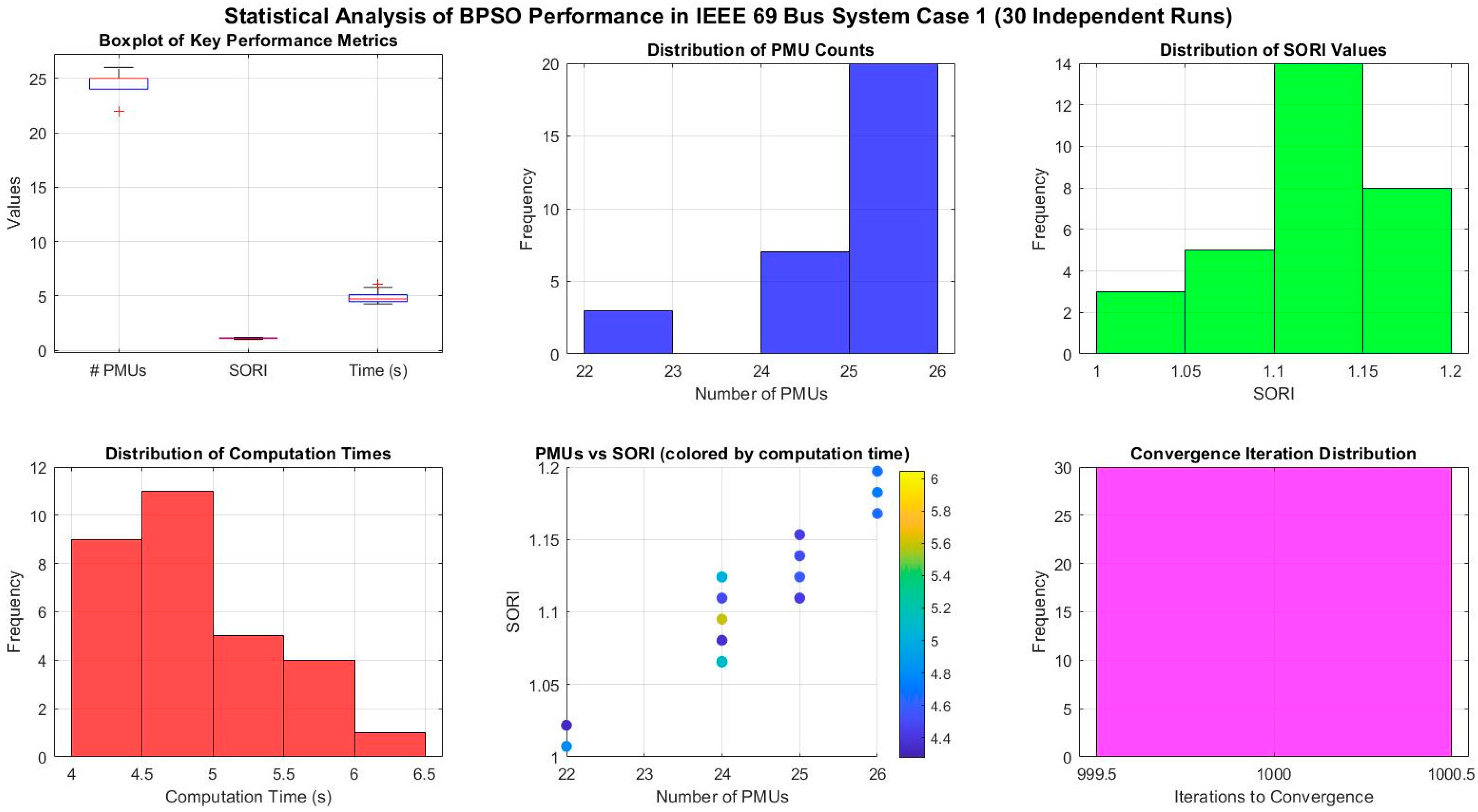

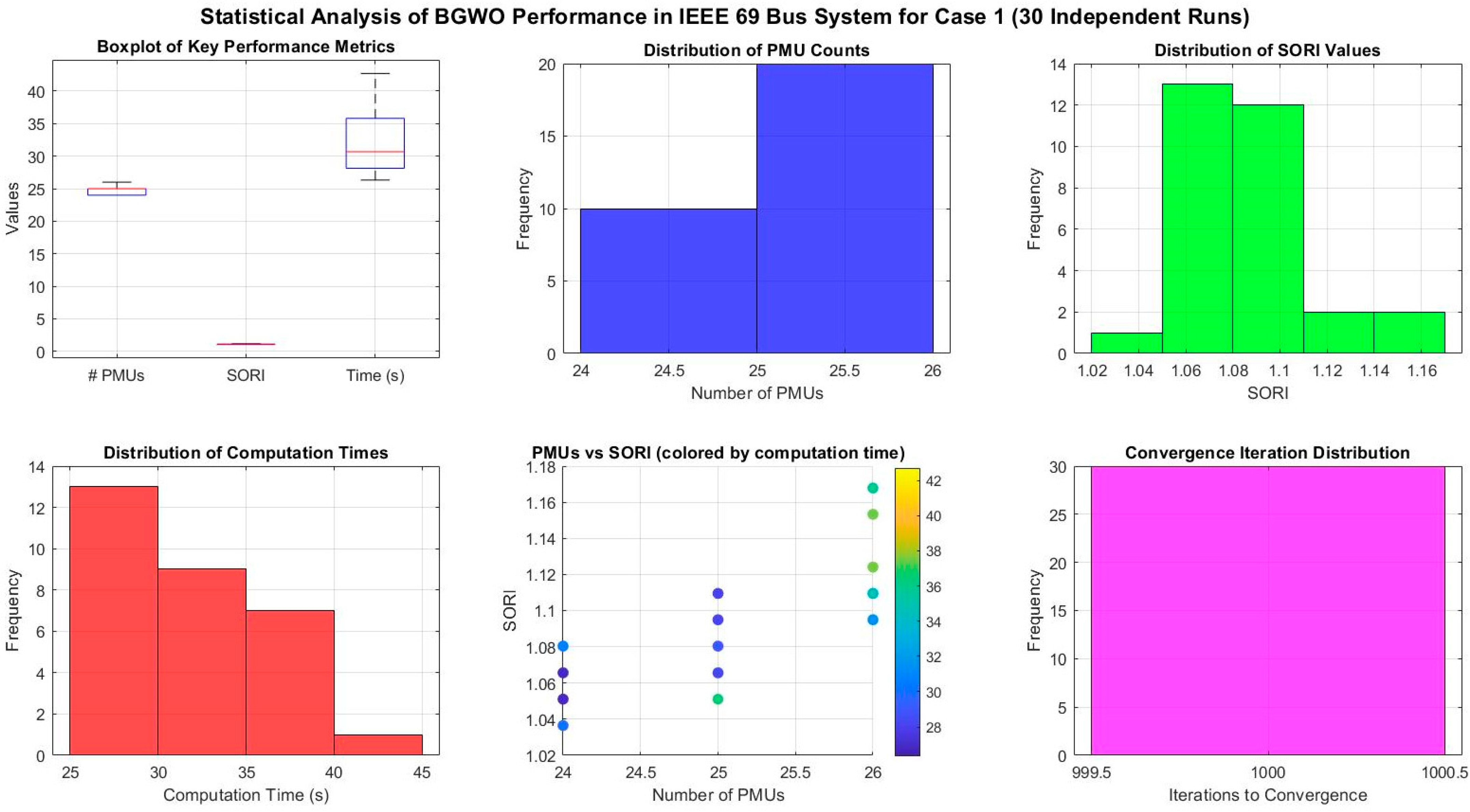

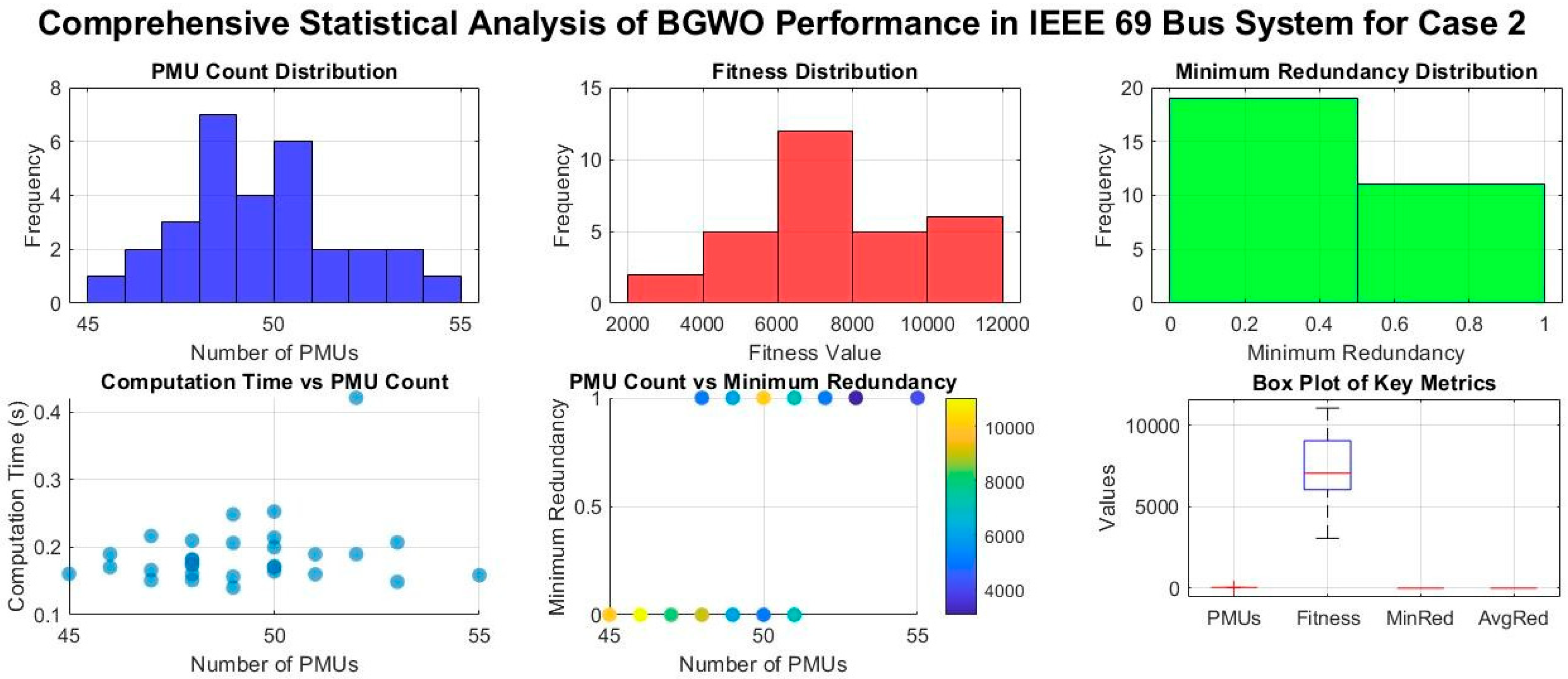

- A detailed statistical analysis is performed to determine the robustness of proposed algorithms, and a pareto front analysis between SORI and number of PMUs is performed to determine the impact of PMU count on system observability.

- Different noise levels are introduced via a change in standard deviations (STDs) to simulate more realistic conditions for the presence of noise in the system to evaluate the impact of noise levels on the state estimation.

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Mathematical Formulation of µPMU Placement

3.1.1. Objective Function

3.1.2. Case Studies

Observability Under Normal Conditions

Observability Considering Zero Injection Buses

Observability During Single µ-PMU Outage

3.2. System Observability Redundancy Index

3.3. Optimization Algorithms

3.3.1. Binary Particle Swarm Optimization

3.3.2. Binary Grey Wolf Optimization

3.4. Fitness Function

3.5. Filtration

3.6. State Estimation Using Forward-Backward Sweep Algorithm and WLS Algorithm

3.7. Procedures for Placement of µ-PMUs

- In the first step, data regarding IEEE bus systems is uploaded from MATPOWER version 8.0 onto the MATLAB program. IEEE 33 and 69 distribution systems are represented in Figure 1.

- In the second step, a connectivity matrix is formed based on the connections between buses in both distribution systems.

- After the formation of the connectivity matrix, initial parameters for both algorithms are initialized, and the fitness function is defined. The main objective of the fitness function is to reduce the number of PMUs while ensuring full observability for all cases. Three case studies are performed for both the 33 and 69 bus systems, i.e., under normal conditions, with Zero Injection buses, and a single PMU outage. ZIBs are identified to leverage them to reduce the PMUs for network observability.

- Simulations are performed, and as the fitness criteria are achieved, the program stops and generates a binary vector consisting of 0’s and 1’s indicating on which buses PMUs are installed. The flowcharts for both PSO and GWO are shown in Figure 2.

- WLS algorithm is employed on selected buses via both algorithms for voltage estimation, and different noise levels are introduced for validating the placement of PMUs.

4. Simulations and Results

4.1. Case 1: OµPP Under Normal Conditions

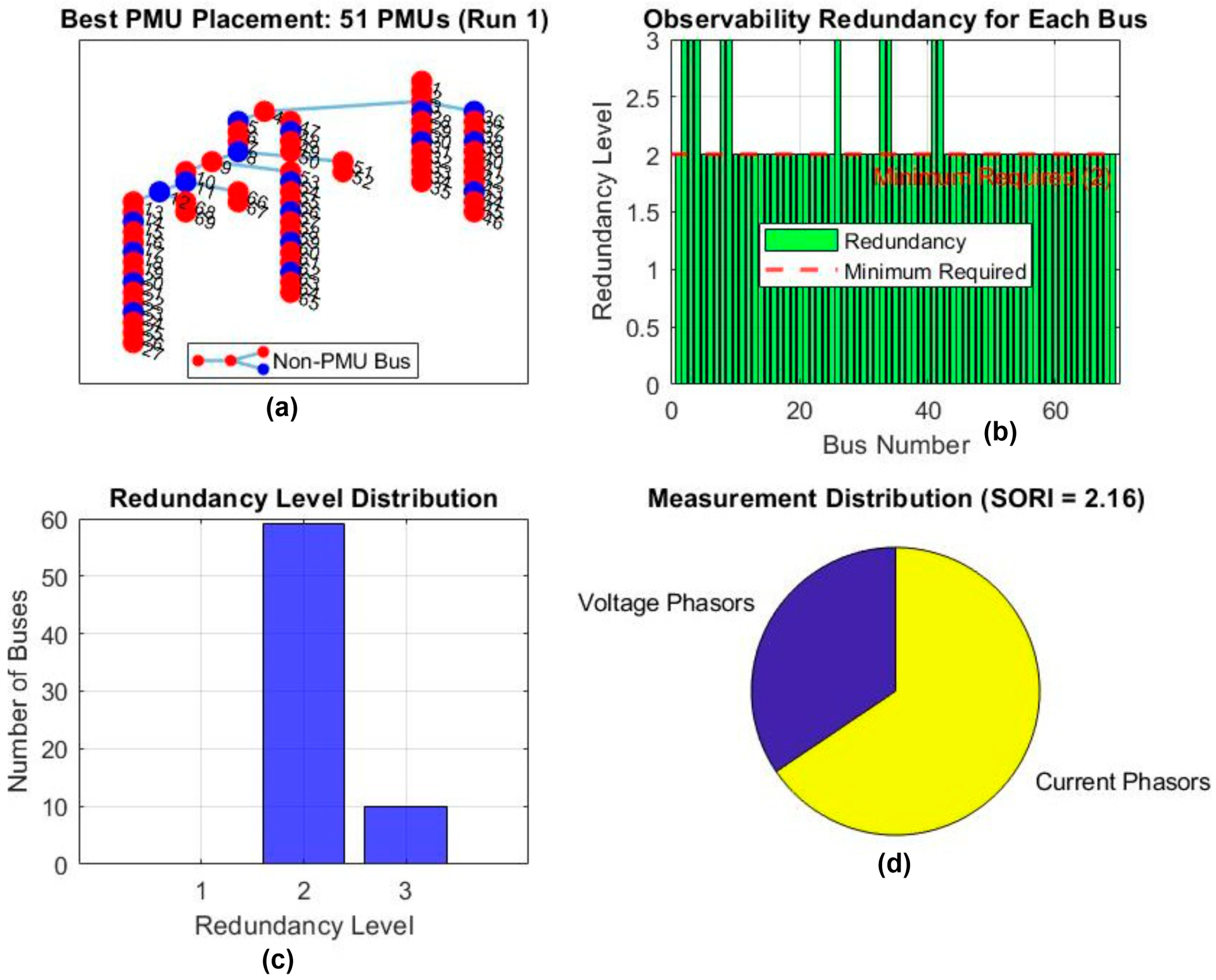

4.2. Case 2: OµPP with a Single µPMU Outage

4.3. Case 3: OPP Considering ZIBs

4.4. Comparison of BPSO and BGWO

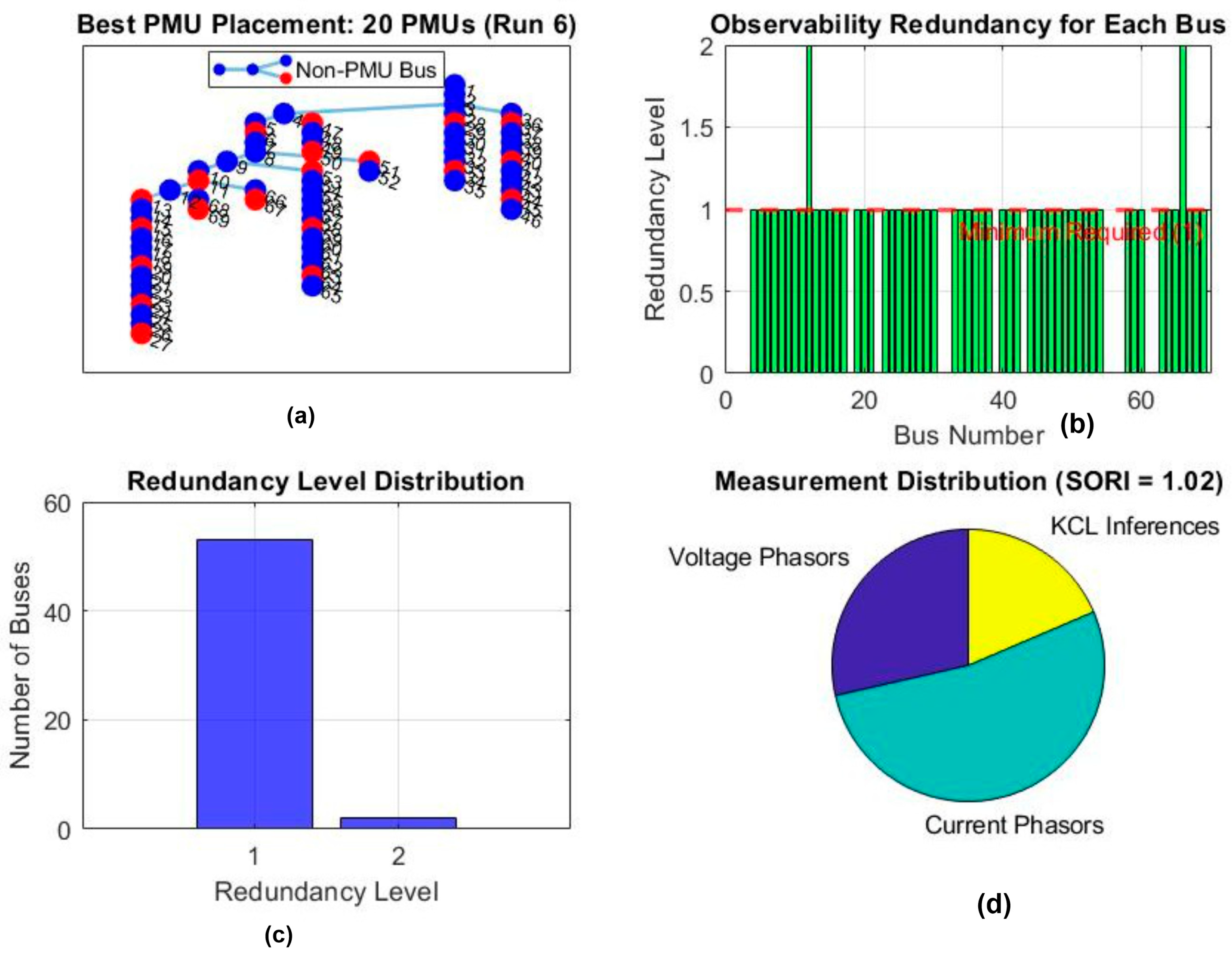

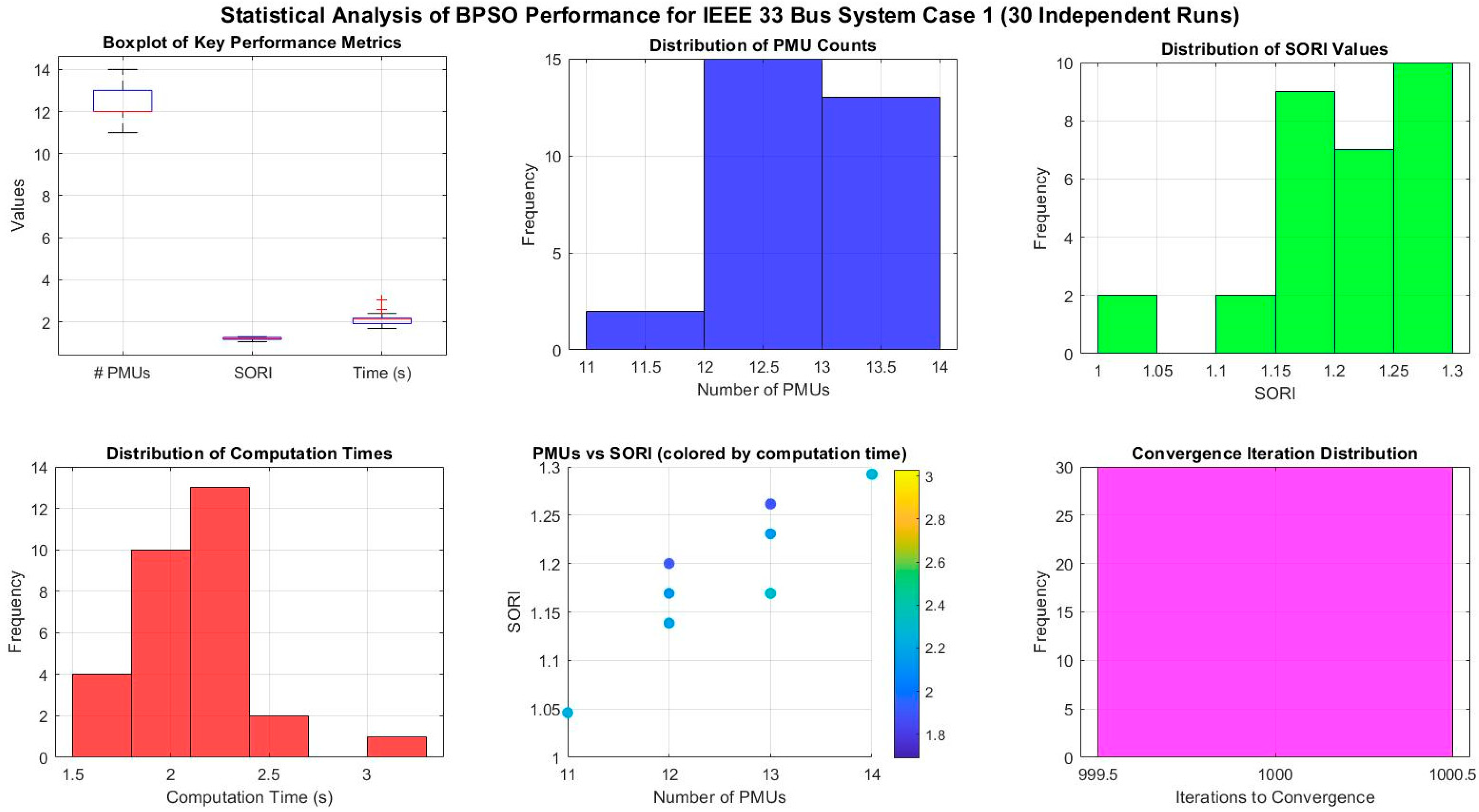

4.4.1. Statistical Analysis with IEEE 33 Bus System

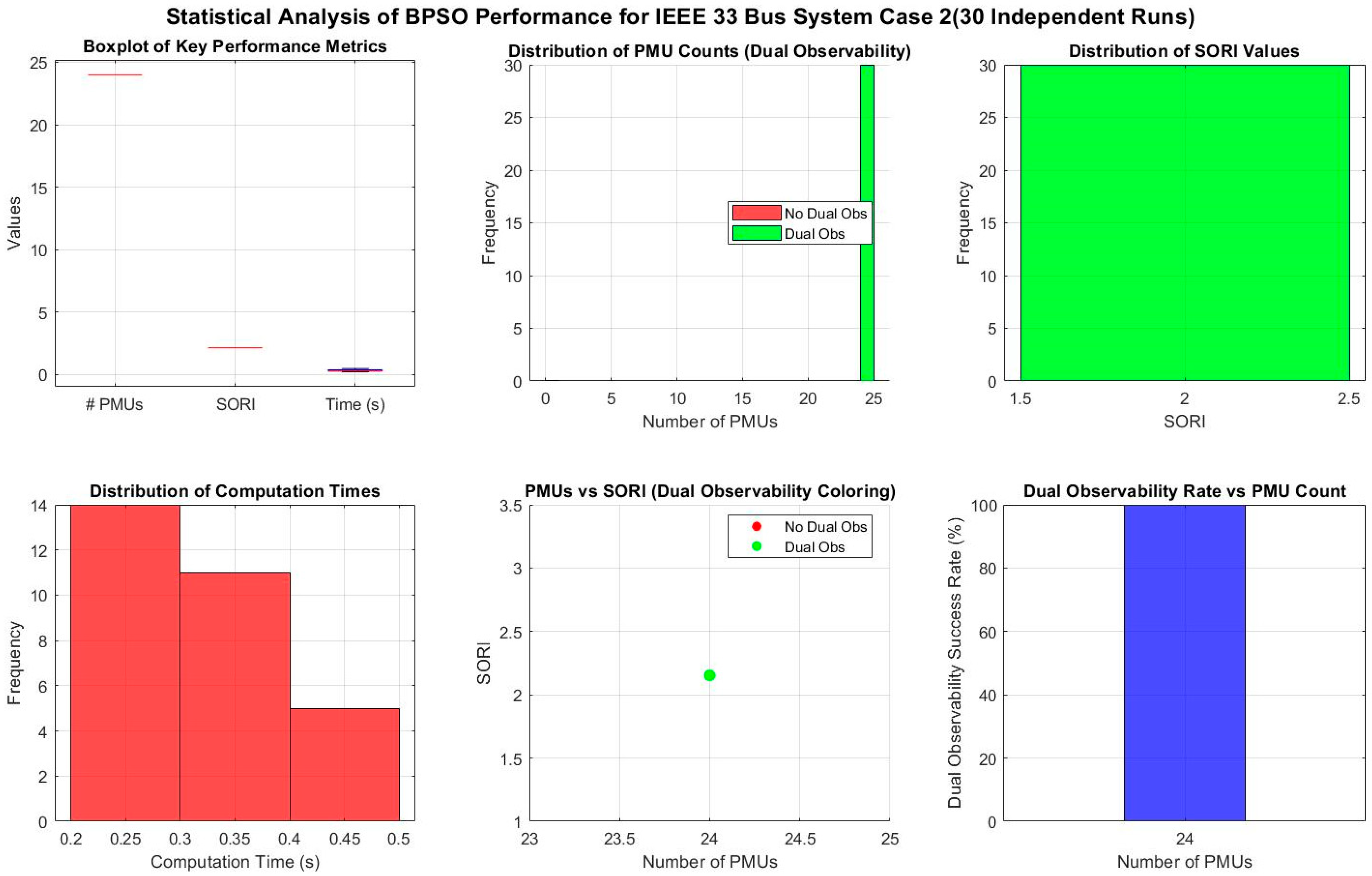

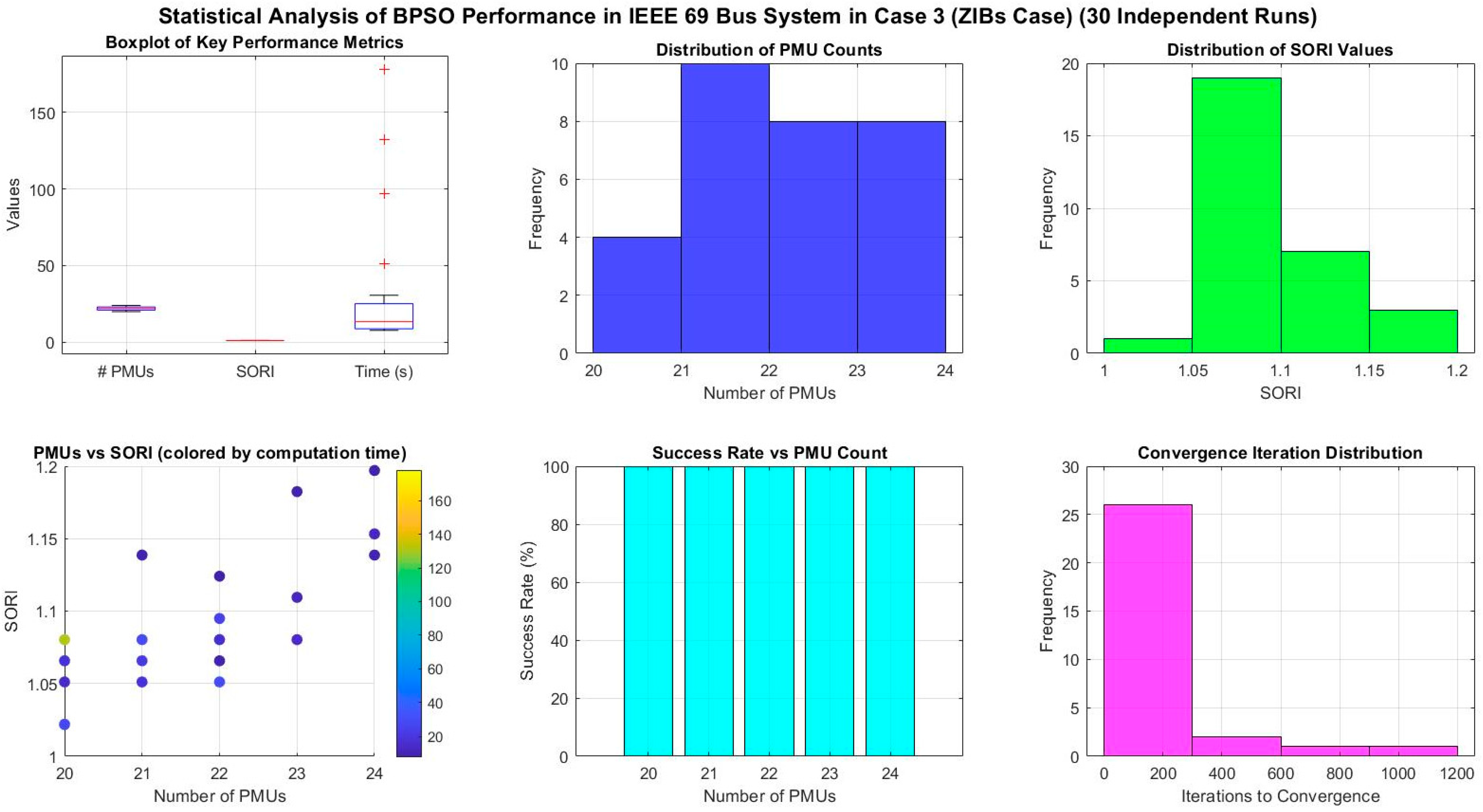

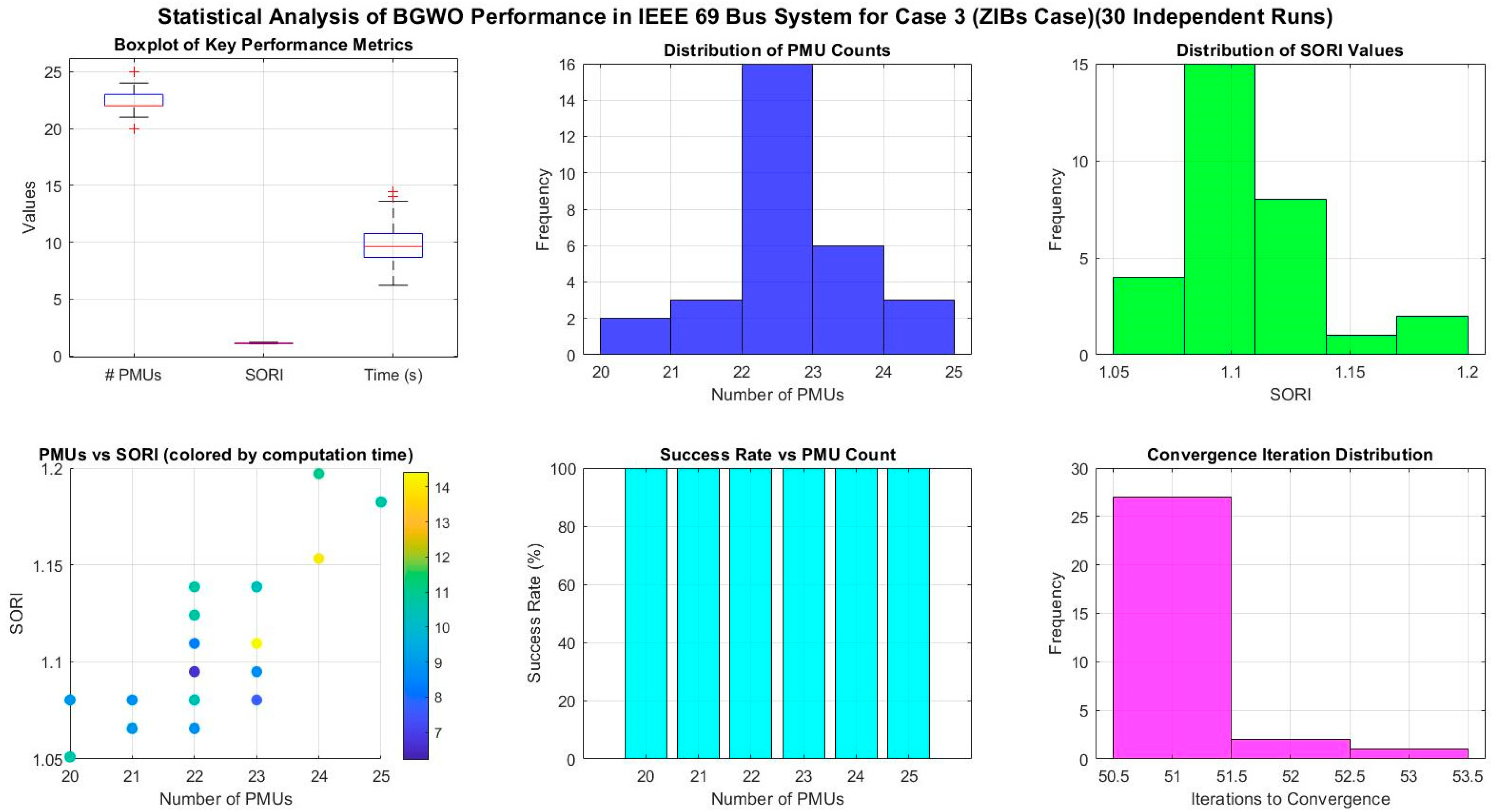

4.4.2. Statistical Analysis with IEEE 69 Bus System

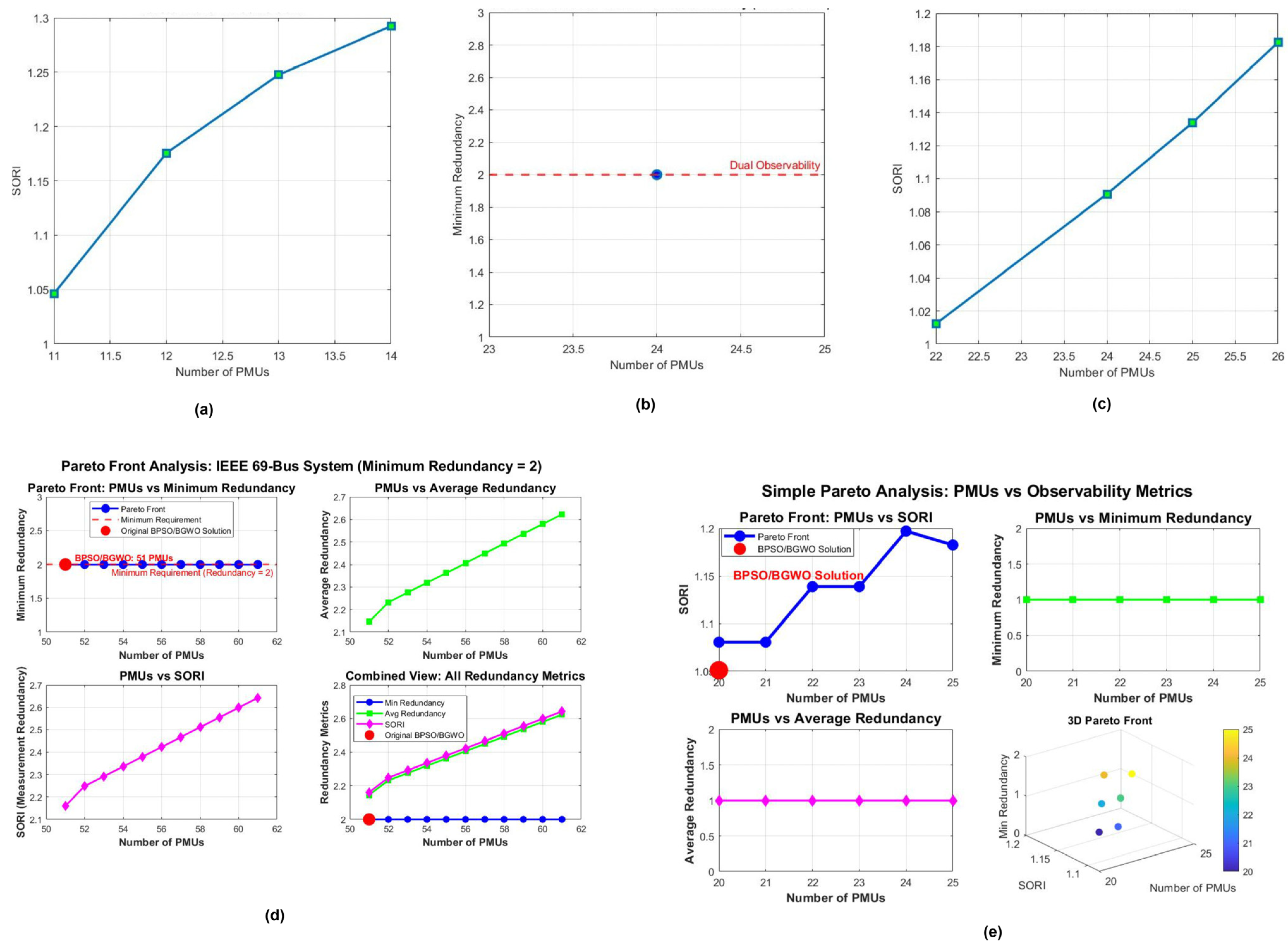

5. Trade-Off Analysis

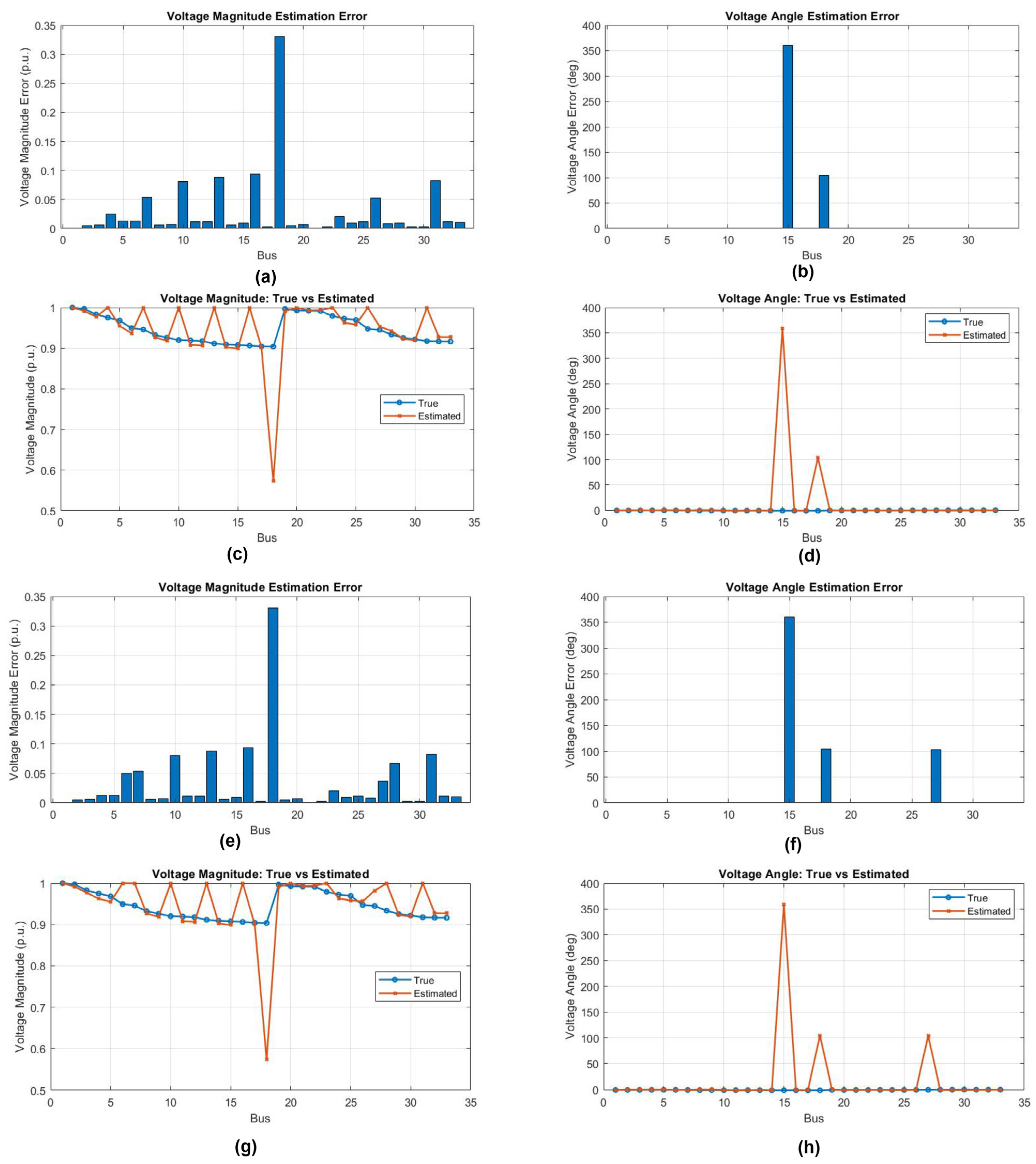

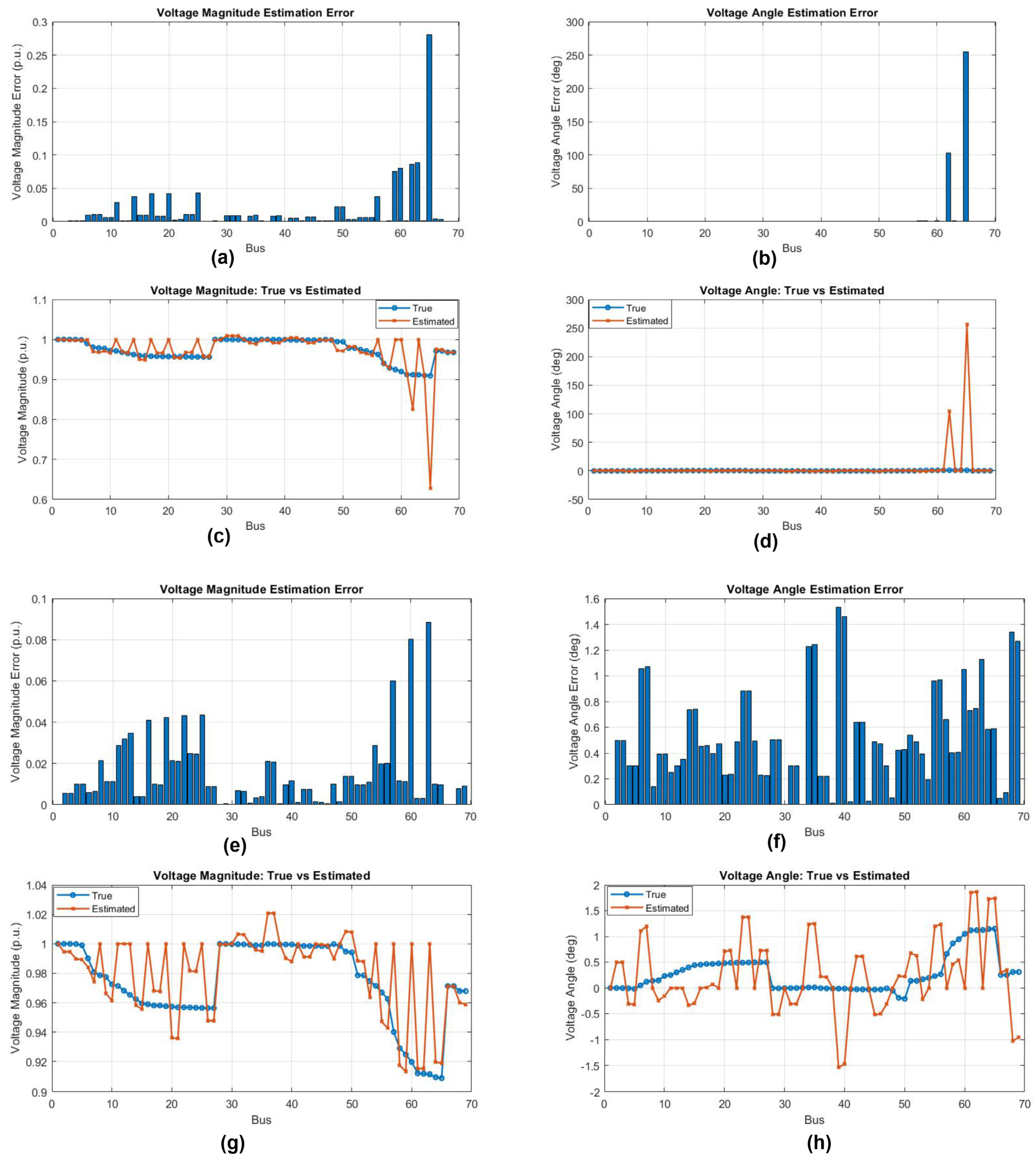

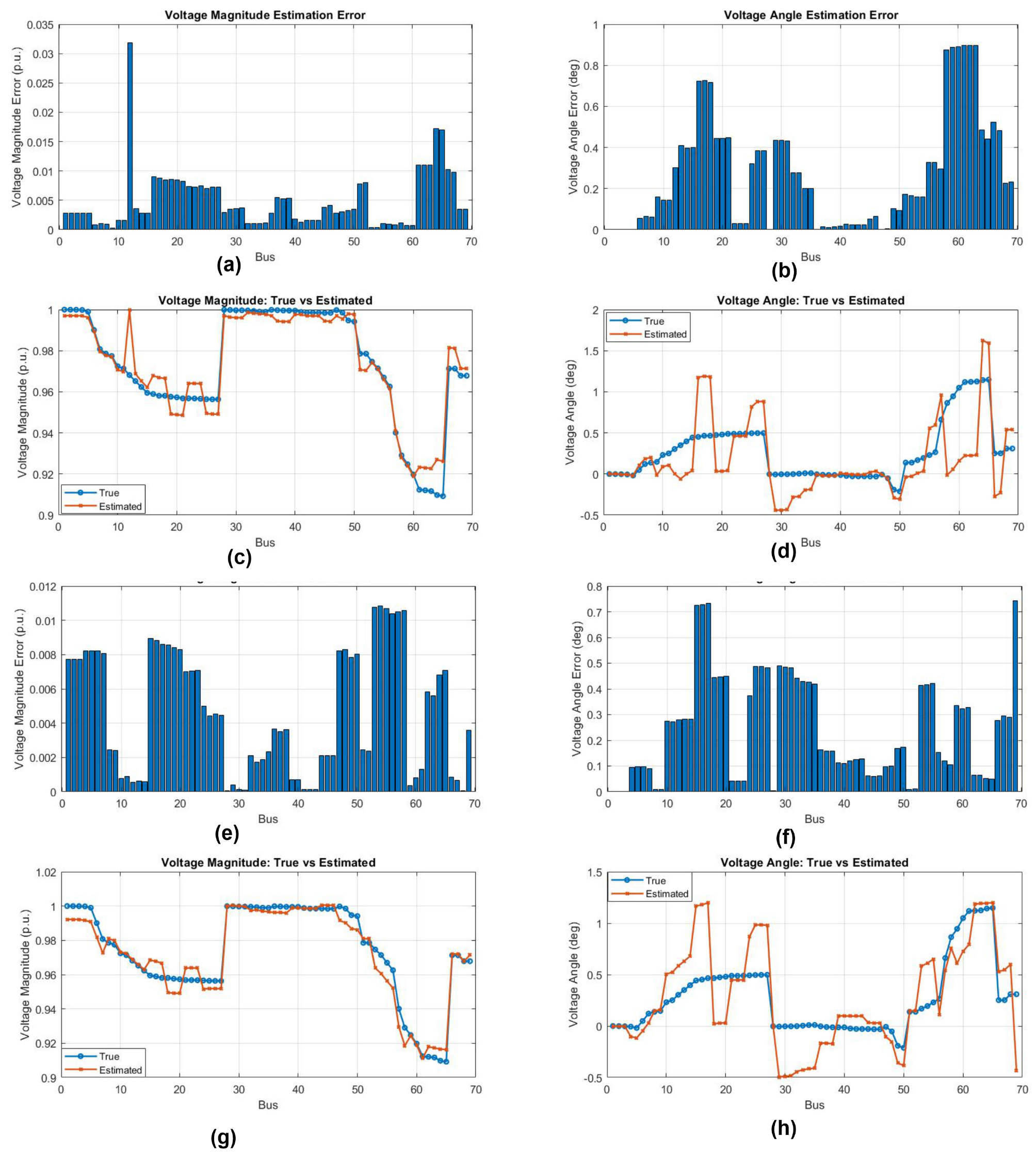

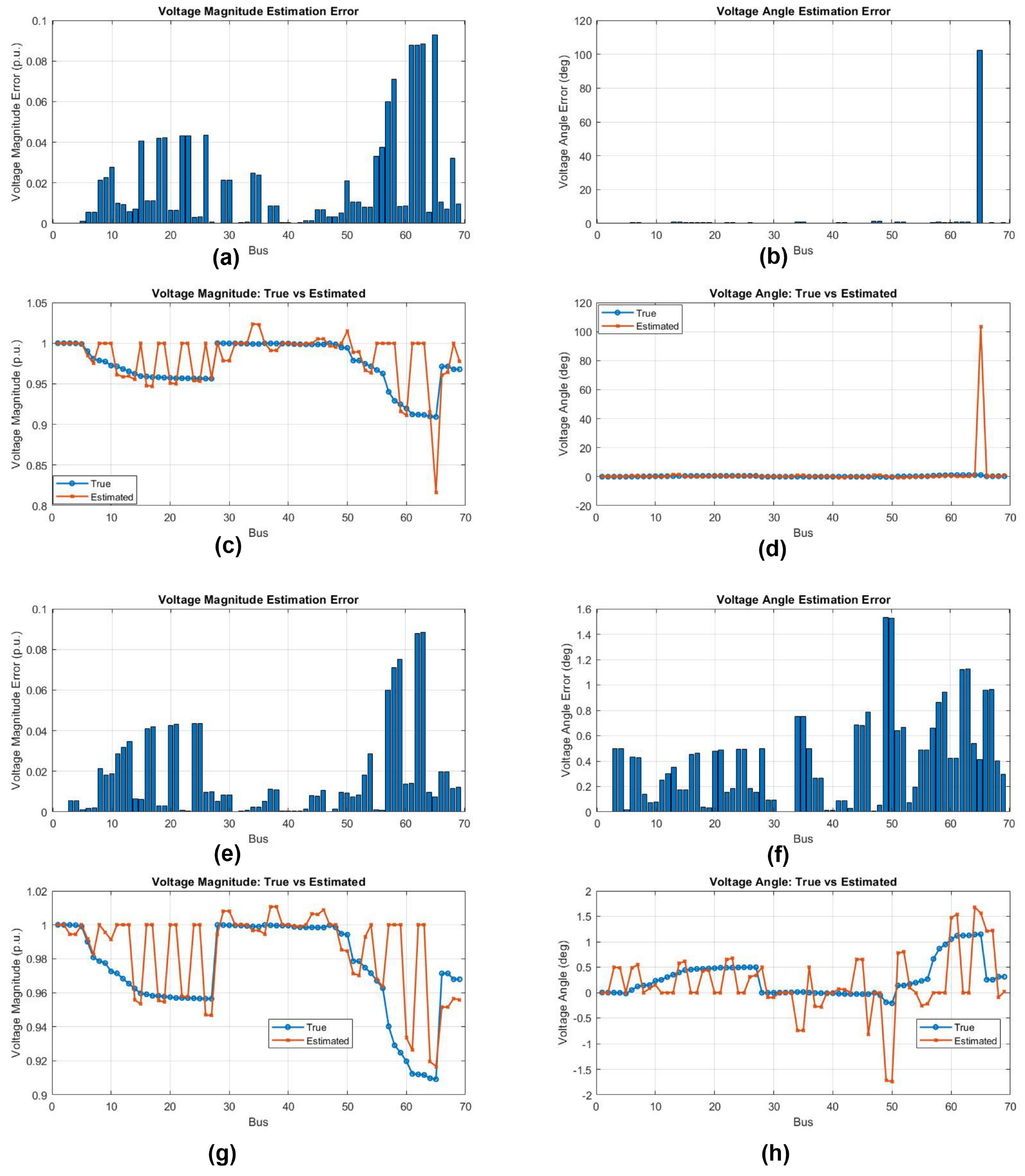

6. Voltage Estimation Using WLS and Forward-Backward Sweep Algorithms

Impact of Variation in Noise Levels on Voltage Estimation

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PMU | Phasor Measuring Unit |

| OPP | Optimal PMU/micro-PMU Placement |

| BPSO | Binary Particle Swarm Optimization |

| BGWO | Binary Grey Wolf Optimization |

| µ-PMU | Micro-PMUs |

| DNs | Distribution Networks |

| SCADA | Supervisory control and data acquisition |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| ZIBs | Zero Injection Buses |

| WLS | Weighted Least Squares |

| STDs | Standard Deviations |

| KCL | Kirchoff’s current Law |

| SORI | System Observability Redundancy Index |

Appendix A

References

- Azmi, K.H.M.; Radzi, N.A.M.; Azhar, N.A.; Samidi, F.S.; Zulkifli, I.T.; Zainal, A.M. Active Electric Distribution Network: Applications, Challenges, and Opportunities. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 134655–134689. [Google Scholar]

- Dixit, A.; Chowdhury, A.; Saini, P. A review on optimal placement of phasor measurement unit (PMU). In System Assurances; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 513–530. ISBN 9780323902403. [Google Scholar]

- Agudo, M.P.; Franco, J.F.; Tenesaca-Caldas, M.; Zambrano-Asanza, S.; Leite, J.B. Optimal placement of uPMUs to improve the reliability of distribution systems through genetic algorithm and variable neighborhood search. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 236, 110910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, R.; De, A. A Novel Bus-Ranking-Algorithm-Based Heuristic Optimization Scheme for PMU Placement. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 9921–9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, N.; Rihan, M.; Hameed, S. PMU-data assisted state estimation of distribution network with integrated renewables: A comprehensive review. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2025, 14, 2456–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, N.; Moghaddas-Tafreshi, S.M. An ILP model for stochastic placement of μPMUs with limited voltage and current channels in a reconfigurable distribution network. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2023, 148, 108951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, T.K.; Acharjee, P. Multiple Solutions of Optimal PMU Placement Using Exponential Binary PSO Algorithm for Smart Grid Applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 2550–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.S.; Kishor, N.; Singh, A.K. PMUs data based detection of oscillatory events and identification of their associated variable: Estimation of information measures approach. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2024, 39, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Wang, C.; Li, P.; Liu, Z.; Yu, L.; Wu, J. Optimal placement of phasor measurement unit in distribution networks considering the changes in topology. Appl. Energy 2019, 250, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, T.; Li, Y.; Mao, W. Two-stage optimal PMU placement for distribution systems. Meas. Control 2024, 58, 820–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Kim, H. PMU Optimal Placement Algorithm Using Topological Observability Analysis. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 2909–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, A.A.; Adail, A.S.; Wadoud, A.A. Optimal phasor measurement units placement for full observability of power system using improved particle swarm optimisation. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2017, 11, 1794–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopov, A.S. A Clustering-Based Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Solving a Multisectoral Agent-Based Model. Stud. Inform. Control 2024, 33, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopov, A.S.; Beklaryan, A.L.; Zhukova, A.A. Optimization of Characteristics for a Stochastic Agent-Based Model of Goods Exchange with the Use of Parallel Hybrid Genetic Algorithm. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2023, 23, 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotopoulou, M.; Petridis, S.; Karachalios, I.; Rakopoulos, D. A Review on Distribution System State Estimation Algorithms. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S. Artificial Intelligence Applications in Electric Distribution Systems: Post-Pandemic Progress and Prospect. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, T.; Moger, T. A critical review of methods for optimal placement of phasor measurement units. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2021, 31, e12698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bairwa, S.K.; Singh, S.P. PMU Placement Optimization Techniques for Complete Power System Observability. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. 2021, 26, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Netto, M.; Krishnan, V.; Zhang, Y.; Mili, L. Measurement placement in electric power transmission and distribution grids: Review of concepts, methods, and research needs. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 805–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswal, C.; Sahu, B.K.; Mishra, M.; Rout, P.K. Real-Time Grid Monitoring and Protection: A Comprehensive Survey on the Advantages of Phasor Measurement Units. Energies 2023, 16, 4054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, A.; Abdellatif, E.; Mousa, A.; Pong, P.W.T. Sensor Technologies for Transmission and Distribution Systems: A Review of the Latest Developments. Energies 2022, 15, 7339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijaychandra, J.; Prasad, B.R.V.; Darapureddi, V.K.; Rao, B.V.; Knypiński, Ł. A Review of Distribution System State Estimation Methods and Their Applications in Power Systems. Electronics 2023, 12, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meriem, M.; Omar, S.; Bouchra, C.; Abdelaziz, B.; Faissal, E.M.; Nazha, C. Study of State Estimation Using Weighted Least Squares Method. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2016, 3, 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Paramo, G.; Bretas, A.; Meyn, S. Research Trends and Applications of PMUs. Energies 2022, 15, 5329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, P.; Devaraj, D.; Isaac, J. Optimal Placement of PMU with Complete Observability using Genetic Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 Third International Conference on Intelligent Techniques in Control, Optimization and Signal Processing (INCOS), Tamil Nadu, India, 14–16 March 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, V.; Thakur, S.S.; Mishra, B. Optimal placement of PMUs using Greedy Algorithm and state estimation. In Proceedings of the 1st IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Intelligent Control and Energy Systems, ICPEICES 2016, Delhi, India, 4–6 July 2016; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 3–7. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Kong, X.; Yuan, X. Optimal PMU Placement for the Distribution System Based on Genetic-Tabu Search Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Chengdu, China, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 980–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouid, A.A.; Mounir Rezaoui, M.; Kouzou, A.; Mohammedi, R.D. Optimal PMUs Placement Using Hybrid PSO-GSA Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Power Electronics and their Applications (ICPEA), Elazig, Turkey, 25–27 September 2019; Volume 1, pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Roy, B.K.S. Cost-Effective Operation Risk-Driven µPMU Placement in Active Distribution Network Considering Channel Cost and Node Reliability. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 6541–6575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Roy, B.K.S. Optimal μPMU Placement in Radial Distribution Networks Using Novel Zero Injection Bus Modelling. SN Comput. Sci. 2023, 4, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, A.; Fotuhi-firuzabad, M.; Fattaheian-dehkordi, S.; Lehtonen, M. A PMU Placement Framework in an Active Distribution Network Based on Voltage Profile Estimation Accuracy. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE PES GTD International Conference and Exposition (GTD), Istanbul, Turkey, 22–25 May 2023; pp. 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, I.; Marcia, R.; Petra, N. Optimal PMU Placement for State Estimation with Grid Parameter Uncertainty. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES Grid Edge Technologies Conference & Exposition (Grid Edge), San Diego, CA, USA, 21–23 January 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Gu, W.; Zhou, S.; Liu, P. Optimal Micro-PMU Placement for Improving State Estimation Accuracy via Mixed-integer Semidefinite Programming. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2023, 11, 468–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; de Callafon, R.A. Optimal PMU Placement for Voltage Estimation in Partially Known Power Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 62nd IEEE Conference on Decision and Control (CDC), Singapore, 13–15 December 2023; pp. 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Fang, C.; Zheng, S.; Zhao, J. Optimal PMU Placement in Distribution Networks for Improving State Estimation Accuracy and Fault Observability. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Nanjing, China, 23–25 December 2021; pp. 1413–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangi, S.; Gaonkar, D.N. Voltage Estimation of Active Distribution Network Using PMU Technology. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 100436–100446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ma, J. A mixed-integer linear programming approach for robust state estimation. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2014, 2, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, N.; Rihan, M.; Hameed, S. Placement of Micro-PMUs and Voltage Estimation in Radial Distribution Networks with Zero Injection constraints. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Bengaluru, India, 10–13 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Run | Number of Placed µ-PMUs | Voltage Phasor Measurements | Current Phasor Measurements | Total Measurements (m) | Total State Variables (n) | SORI (m/n) | Computation Time (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | ||

| 1 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 52 | 54 | 76 | 78 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.200 | 1.55 | 2.11 |

| 2 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 28 | 54 | 56 | 80 | 84 | 65 | 1.231 | 1.292 | 1.82 | 2.47 |

| 3 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 54 | 52 | 78 | 76 | 65 | 1.200 | 1.169 | 1.51 | 2.13 |

| 4 | 13 | 12 | 26 | 24 | 54 | 50 | 80 | 74 | 65 | 1.231 | 1.138 | 1.44 | 2.15 |

| 5 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 52 | 52 | 76 | 76 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.169 | 1.44 | 2.10 |

| 6 | 13 | 12 | 26 | 24 | 56 | 52 | 82 | 76 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.169 | 1.53 | 2.05 |

| 7 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 52 | 54 | 76 | 78 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.200 | 1.66 | 2.23 |

| 8 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 54 | 56 | 78 | 82 | 65 | 1.200 | 1.262 | 1.47 | 2.19 |

| 9 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 24 | 50 | 50 | 76 | 74 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.231 | 1.52 | 2.40 |

| 10 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 26 | 56 | 56 | 82 | 82 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.262 | 1.55 | 2.49 |

| 11 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 24 | 54 | 50 | 78 | 74 | 65 | 1.200 | 1.231 | 1.92 | 2.28 |

| 12 | 12 | 11 | 24 | 22 | 50 | 46 | 74 | 68 | 65 | 1.138 | 1.046 | 2.03 | 2.00 |

| 13 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 24 | 56 | 54 | 82 | 78 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.200 | 1.73 | 2.16 |

| 14 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 52 | 50 | 76 | 74 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.138 | 1.71 | 2.06 |

| 15 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 54 | 52 | 78 | 76 | 65 | 1.200 | 1.169 | 1.77 | 2.00 |

| 16 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 28 | 56 | 56 | 82 | 84 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.292 | 2.02 | 2.13 |

| 17 | 11 | 12 | 22 | 24 | 46 | 52 | 68 | 76 | 65 | 1.046 | 1.169 | 2.46 | 2.18 |

| 18 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 54 | 56 | 78 | 82 | 65 | 1.200 | 1.262 | 1.76 | 2.17 |

| 19 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 50 | 52 | 74 | 76 | 65 | 1.138 | 1.169 | 1.80 | 2.02 |

| 20 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 24 | 56 | 50 | 82 | 74 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.231 | 2.00 | 2.07 |

| 21 | 12 | 12 | 24 | 24 | 52 | 52 | 76 | 76 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.169 | 1.74 | 2.00 |

| 22 | 14 | 12 | 28 | 24 | 56 | 54 | 84 | 78 | 65 | 1.292 | 1.200 | 2.14 | 2.04 |

| 23 | 13 | 13 | 26 | 28 | 56 | 58 | 82 | 86 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.323 | 1.75 | 2.19 |

| 24 | 14 | 14 | 28 | 24 | 56 | 52 | 84 | 76 | 65 | 1.292 | 1.169 | 1.87 | 2.05 |

| 25 | 11 | 12 | 22 | 24 | 46 | 52 | 68 | 76 | 65 | 1.046 | 1.169 | 1.74 | 2.05 |

| 26 | 13 | 12 | 26 | 24 | 56 | 52 | 82 | 76 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.169 | 1.78 | 2.09 |

| 27 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 52 | 56 | 76 | 82 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.262 | 2.00 | 2.14 |

| 82 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 52 | 56 | 76 | 82 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.262 | 1.71 | 2.03 |

| 29 | 12 | 13 | 24 | 26 | 52 | 56 | 76 | 82 | 65 | 1.169 | 1.262 | 1.72 | 2.10 |

| 30 | 13 | 12 | 26 | 24 | 56 | 52 | 82 | 76 | 65 | 1.262 | 1.169 | 1.76 | 2.09 |

| Run | Number of Placed µ-PMUs | Voltage Phasor Measurements | Current Phasor Measurements | Total Measurements (m) | Total State Variables (n) | SORI (m/n) | Computation Time (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | ||

| 1 | 24 | 25 | 48 | 50 | 106 | 94 | 154 | 144 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.051 | 5.02 | 51.32 |

| 2 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 104 | 96 | 154 | 146 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.066 | 4.34 | 52.28 |

| 3 | 25 | 26 | 50 | 52 | 104 | 102 | 154 | 154 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.124 | 4.34 | 51.05 |

| 4 | 26 | 26 | 52 | 52 | 110 | 106 | 162 | 158 | 137 | 1.182 | 1.1533 | 7.10 | 58.62 |

| 5 | 22 | 24 | 44 | 48 | 94 | 100 | 138 | 148 | 137 | 1.007 | 1.080 | 5.89 | 41.66 |

| 6 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 106 | 102 | 156 | 152 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.109 | 5.80 | 45.79 |

| 7 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 108 | 98 | 158 | 148 | 137 | 1.153 | 1.0803 | 6.21 | 42.71 |

| 8 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 104 | 98 | 152 | 146 | 137 | 1.109 | 1.066 | 5.61 | 36.15 |

| 9 | 22 | 24 | 44 | 48 | 94 | 94 | 138 | 142 | 137 | 1.007 | 1.036 | 5.85 | 42.55 |

| 10 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 100 | 96 | 148 | 144 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.051 | 5.86 | 42.81 |

| 11 | 24 | 26 | 48 | 52 | 102 | 98 | 150 | 150 | 137 | 1.095 | 1.095 | 5.89 | 52.33 |

| 12 | 24 | 26 | 48 | 52 | 100 | 108 | 148 | 160 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.168 | 5.61 | 49.62 |

| 13 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 158 | 150 | 137 | 1.153 | 1.095 | 5.90 | 51.82 |

| 14 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 98 | 96 | 146 | 144 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.051 | 6.91 | 47.00 |

| 15 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 106 | 100 | 156 | 150 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.095 | 6.14 | 49.69 |

| 16 | 26 | 26 | 52 | 52 | 110 | 100 | 162 | 152 | 137 | 1.182 | 1.109 | 5.88 | 58.25 |

| 17 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 106 | 102 | 156 | 152 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.109 | 6.45 | 52.66 |

| 18 | 26 | 25 | 52 | 50 | 108 | 98 | 160 | 148 | 137 | 1.168 | 1.080 | 5.66 | 46.50 |

| 19 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 106 | 100 | 156 | 150 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.095 | 6.01 | 47.79 |

| 20 | 25 | 26 | 50 | 52 | 106 | 102 | 156 | 154 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.124 | 6.02 | 48.59 |

| 21 | 25 | 24 | 50 | 48 | 104 | 96 | 154 | 144 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.051 | 6.06 | 41.29 |

| 22 | 25 | 24 | 50 | 48 | 104 | 98 | 154 | 146 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.0657 | 5.55 | 43.10 |

| 23 | 25 | 26 | 50 | 52 | 108 | 98 | 158 | 150 | 137 | 1.153 | 1.095 | 5.89 | 53.95 |

| 24 | 25 | 25 | 50 | 50 | 104 | 102 | 154 | 152 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.109 | 5.57 | 48.49 |

| 25 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 100 | 96 | 148 | 144 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.051 | 5.55 | 43.14 |

| 26 | 26 | 25 | 52 | 50 | 112 | 96 | 164 | 146 | 137 | 1.197 | 1.066 | 5.27 | 45.81 |

| 27 | 25 | 24 | 50 | 48 | 104 | 96 | 154 | 144 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.051 | 4.30 | 41.54 |

| 28 | 25 | 24 | 50 | 48 | 102 | 96 | 152 | 144 | 137 | 1.109 | 1.051 | 4.42 | 46.04 |

| 29 | 22 | 25 | 44 | 50 | 96 | 96 | 140 | 146 | 137 | 1.022 | 1.066 | 4.77 | 55.98 |

| 30 | 26 | 25 | 52 | 50 | 110 | 96 | 162 | 146 | 137 | 1.182 | 1.066 | 4.57 | 49.71 |

| Run | Number of Placed µ-PMUs | Voltage Phasor Measurements | Current Phasor Measurements | Total Measurements (m) | Total State Variables (n) | SORI (m/n) | Computation Time (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | ||

| 1 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.28 | 0.33 |

| 2 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.34 | 0.46 |

| 3 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.34 | 0.57 |

| 4 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.26 | 0.49 |

| 5 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| 6 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.25 | 0.50 |

| 7 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.25 | 0.62 |

| 8 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.26 | 0.41 |

| 9 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.26 | 0.45 |

| 10 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.23 | 0.66 |

| 11 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.24 | 0.51 |

| 12 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.22 | 0.56 |

| 13 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.21 | 0.49 |

| 14 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.21 | 0.44 |

| 15 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.47 |

| 16 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.49 |

| 17 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.58 |

| 18 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.51 |

| 19 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.62 |

| 20 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.21 | 0.54 |

| 21 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.53 |

| 22 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.64 |

| 23 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.54 |

| 24 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.50 |

| 25 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.49 |

| 26 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.47 |

| 27 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.45 |

| 28 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.66 |

| 29 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.19 | 0.55 |

| 30 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 92 | 92 | 140 | 140 | 65 | 2.154 | 2.154 | 0.20 | 0.42 |

| Run | Number of Placed µ-PMUs | Voltage Phasor Measurements | Current Phasor Measurements | Total Measurements (m) | Total State Variables (n) | SORI (m/n) | Computation Time (s) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | ||

| 1 | 51 | 51 | 102 | 102 | 194 | 200 | 296 | 302 | 137 | 2.161 | 2.219 | 6.19 | 0.17 |

| 2 | 54 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 208 | 200 | 316 | 300 | 137 | 2.307 | 2.200 | 7.67 | 0.17 |

| 3 | 55 | 49 | 110 | 98 | 210 | 190 | 320 | 288 | 137 | 2.336 | 2.1022 | 12.95 | 0.17 |

| 4 | 53 | 47 | 106 | 94 | 204 | 186 | 310 | 280 | 137 | 2.2628 | 2.0438 | 14.70 | 0.17 |

| 5 | 53 | 48 | 106 | 96 | 202 | 186 | 308 | 282 | 137 | 2.248 | 2.0584 | 9.47 | 0.16 |

| 6 | 54 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 208 | 192 | 316 | 292 | 137 | 2.307 | 2.1314 | 10.84 | 0.18 |

| 7 | 54 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 206 | 194 | 314 | 294 | 137 | 2.292 | 2.146 | 12.59 | 0.17 |

| 8 | 55 | 46 | 110 | 92 | 212 | 178 | 322 | 270 | 137 | 2.350 | 1.9708 | 6.36 | 0.17 |

| 9 | 53 | 55 | 106 | 110 | 204 | 212 | 310 | 322 | 137 | 2.263 | 2.3504 | 4.54 | 0.17 |

| 10 | 53 | 48 | 106 | 96 | 202 | 188 | 308 | 284 | 137 | 2.248 | 2.073 | 8.61 | 0.17 |

| 11 | 55 | 48 | 110 | 96 | 208 | 190 | 318 | 286 | 137 | 2.321 | 2.0876 | 5.63 | 0.17 |

| 12 | 55 | 48 | 110 | 96 | 208 | 192 | 318 | 288 | 137 | 2.307 | 2.1022 | 7.59 | 0.17 |

| 13 | 54 | 46 | 108 | 92 | 202 | 182 | 310 | 274 | 137 | 2.2628 | 2 | 16.41 | 0.17 |

| 14 | 52 | 48 | 104 | 96 | 198 | 192 | 302 | 288 | 137 | 2.2044 | 2.1022 | 14.25 | 0.17 |

| 15 | 54 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 206 | 192 | 314 | 292 | 137 | 2.292 | 2.1314 | 12.46 | 0.16 |

| 16 | 53 | 49 | 106 | 98 | 204 | 196 | 310 | 294 | 137 | 2.263 | 2.146 | 10.39 | 0.16 |

| 17 | 53 | 50 | 106 | 100 | 202 | 202 | 308 | 302 | 137 | 2.248 | 2.2044 | 10.34 | 0.18 |

| 18 | 55 | 53 | 110 | 106 | 212 | 202 | 322 | 308 | 137 | 2.350 | 2.2482 | 13.94 | 0.18 |

| 19 | 53 | 49 | 106 | 98 | 200 | 190 | 306 | 288 | 137 | 2.234 | 2.1022 | 12.34 | 0.19 |

| 20 | 54 | 50 | 108 | 100 | 210 | 190 | 318 | 290 | 137 | 2.321 | 2.1168 | 20.92 | 0.19 |

| 21 | 53 | 53 | 106 | 106 | 200 | 208 | 306 | 314 | 137 | 2.2336 | 2.292 | 14.70 | 0.19 |

| 22 | 54 | 49 | 108 | 98 | 208 | 194 | 316 | 292 | 137 | 2.307 | 2.1314 | 13.22 | 0.17 |

| 23 | 53 | 47 | 106 | 94 | 204 | 190 | 310 | 284 | 137 | 2.263 | 2.073 | 13.67 | 0.19 |

| 24 | 54 | 51 | 108 | 102 | 208 | 200 | 316 | 302 | 137 | 2.307 | 2.2044 | 15.07 | 0.23 |

| 25 | 56 | 48 | 112 | 96 | 220 | 194 | 332 | 290 | 137 | 2.423 | 2.1168 | 22.66 | 0.24 |

| 26 | 53 | 52 | 106 | 104 | 202 | 202 | 308 | 306 | 137 | 2.248 | 2.2336 | 15.59 | 0.24 |

| 27 | 54 | 51 | 108 | 102 | 206 | 202 | 314 | 304 | 137 | 2.292 | 2.219 | 20.88 | 0.49 |

| 28 | 53 | 47 | 106 | 94 | 202 | 190 | 308 | 284 | 137 | 2.248 | 2.073 | 15.64 | 0.33 |

| 29 | 56 | 48 | 112 | 96 | 220 | 188 | 332 | 284 | 137 | 2.423 | 2.073 | 20.83 | 0.26 |

| 30 | 54 | 45 | 108 | 90 | 204 | 176 | 312 | 266 | 137 | 2.277 | 1.9416 | 18.82 | 0.25 |

| Run | Number of Placed µ-PMUs | Voltage Phasor Measurements | Current Phasor Measurements | KCL Inference Measurements | Total Measurements (m) | Total State Variables (n) | SORI (m/n) | Computation Time (s) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | BPSO | BGWO | ||

| 1 | 24 | 22 | 48 | 44 | 86 | 90 | 24 | 18 | 158 | 152 | 137 | 1.153 | 1.109 | 13.35 | 7.78 |

| 2 | 21 | 23 | 42 | 46 | 92 | 88 | 22 | 14 | 156 | 148 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.080 | 10.43 | 6.90 |

| 3 | 23 | 23 | 46 | 46 | 80 | 94 | 22 | 16 | 148 | 156 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.139 | 16.93 | 8.04 |

| 4 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 82 | 88 | 22 | 18 | 148 | 150 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.095 | 7.79 | 5.59 |

| 5 | 21 | 22 | 42 | 44 | 78 | 90 | 26 | 20 | 146 | 154 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.124 | 141.08 | 6.75 |

| 6 | 20 | 22 | 40 | 44 | 74 | 88 | 26 | 16 | 140 | 148 | 137 | 1.022 | 1.080 | 24.47 | 7.95 |

| 7 | 21 | 22 | 42 | 44 | 84 | 90 | 18 | 18 | 144 | 152 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.109 | 6.58 | 6.54 |

| 8 | 21 | 21 | 42 | 42 | 80 | 86 | 22 | 20 | 144 | 1.080 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.080 | 20.03 | 8.04 |

| 9 | 24 | 24 | 48 | 48 | 98 | 94 | 18 | 16 | 164 | 158 | 137 | 1.197 | 1.153 | 6.50 | 8.21 |

| 10 | 24 | 23 | 48 | 46 | 88 | 90 | 20 | 16 | 156 | 152 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.109 | 6.60 | 7.28 |

| 11 | 22 | 21 | 44 | 42 | 84 | 86 | 18 | 18 | 146 | 146 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.066 | 81.37 | 5.75 |

| 12 | 22 | 23 | 44 | 46 | 84 | 92 | 20 | 12 | 148 | 150 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.095 | 13.61 | 5.73 |

| 13 | 20 | 22 | 40 | 44 | 80 | 92 | 28 | 18 | 148 | 154 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.124 | 114.96 | 5.64 |

| 14 | 21 | 22 | 42 | 44 | 88 | 90 | 18 | 18 | 148 | 152 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.109 | 48.53 | 6.65 |

| 15 | 21 | 23 | 42 | 46 | 86 | 94 | 16 | 16 | 144 | 156 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.139 | 8.42 | 7.26 |

| 16 | 20 | 24 | 40 | 48 | 78 | 94 | 28 | 22 | 146 | 164 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.197 | 15.98 | 7.76 |

| 17 | 20 | 22 | 40 | 44 | 82 | 90 | 22 | 22 | 144 | 156 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.139 | 13.15 | 7.65 |

| 18 | 21 | 22 | 42 | 44 | 76 | 88 | 28 | 22 | 146 | 154 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.124 | 12.28 | 7.01 |

| 19 | 23 | 20 | 46 | 40 | 94 | 84 | 22 | 20 | 162 | 144 | 137 | 1.182 | 1.051 | 8.22 | 7.27 |

| 20 | 21 | 21 | 42 | 42 | 80 | 88 | 24 | 18 | 146 | 148 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.080 | 20.35 | 5.62 |

| 21 | 23 | 23 | 46 | 46 | 84 | 94 | 22 | 12 | 152 | 152 | 137 | 1.109 | 1.109 | 8.92 | 7.05 |

| 22 | 23 | 25 | 46 | 50 | 86 | 98 | 20 | 14 | 152 | 162 | 137 | 1.109 | 1.182 | 11.35 | 6.86 |

| 23 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 82 | 88 | 24 | 16 | 150 | 148 | 137 | 1.095 | 1.080 | 22.06 | 6.38 |

| 24 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 82 | 86 | 20 | 16 | 146 | 146 | 137 | 1.066 | 1.066 | 8.44 | 7.26 |

| 25 | 21 | 22 | 42 | 44 | 84 | 86 | 22 | 16 | 148 | 146 | 137 | 1.080 | 1.066 | 26.44 | 6.59 |

| 26 | 21 | 20 | 42 | 40 | 76 | 84 | 26 | 24 | 144 | 148 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.080 | 18.09 | 6.07 |

| 27 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 92 | 92 | 18 | 20 | 154 | 156 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.139 | 8.92 | 5.83 |

| 28 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 90 | 84 | 20 | 20 | 154 | 148 | 137 | 1.124 | 1.080 | 7.48 | 7.39 |

| 29 | 22 | 22 | 44 | 44 | 82 | 88 | 18 | 20 | 144 | 152 | 137 | 1.051 | 1.109 | 28.76 | 5.68 |

| 30 | 24 | 22 | 48 | 44 | 94 | 86 | 14 | 26 | 156 | 156 | 137 | 1.139 | 1.139 | 8.41 | 7.81 |

| IEEE Test Systems | Case Studies | Nµ-PMUs with BPSO | Nµ-PMUs with BGWO | [38] MILP | [9] ILP | [29] ILP | [6] ILP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 33 | Case 1 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | NR | NR |

| 69 | Case 1 | 24 | 24 | 24 | NR | 24 | 24 |

| 33 | Case 2 | 24 | 24 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 69 | Case 2 | 51 | 51 | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| 69 | Case 3 | 20 | 20 | 16 | NR | NR | NR |

| NR means | Not Reported | None of the above presented articles included any detailed Redundancy analysis. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ali, A.; Abdul Wahab, N.I.; Othman, M.L.; Farade, R.A.; Samkari, H.S.; Allehyani, M.F. Optimal µ-PMU Placement and Voltage Estimation in Distribution Networks: Evaluation Through Multiple Case Studies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411036

Ali A, Abdul Wahab NI, Othman ML, Farade RA, Samkari HS, Allehyani MF. Optimal µ-PMU Placement and Voltage Estimation in Distribution Networks: Evaluation Through Multiple Case Studies. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411036

Chicago/Turabian StyleAli, Asjad, Noor Izzri Abdul Wahab, Mohammad Lutfi Othman, Rizwan A. Farade, Husam S. Samkari, and Mohammed F. Allehyani. 2025. "Optimal µ-PMU Placement and Voltage Estimation in Distribution Networks: Evaluation Through Multiple Case Studies" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411036

APA StyleAli, A., Abdul Wahab, N. I., Othman, M. L., Farade, R. A., Samkari, H. S., & Allehyani, M. F. (2025). Optimal µ-PMU Placement and Voltage Estimation in Distribution Networks: Evaluation Through Multiple Case Studies. Sustainability, 17(24), 11036. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411036