Sustainability: Panacea or Local Energy Injustice? A Qualitative Media Review of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Wind-to-Hydrogen Boom

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

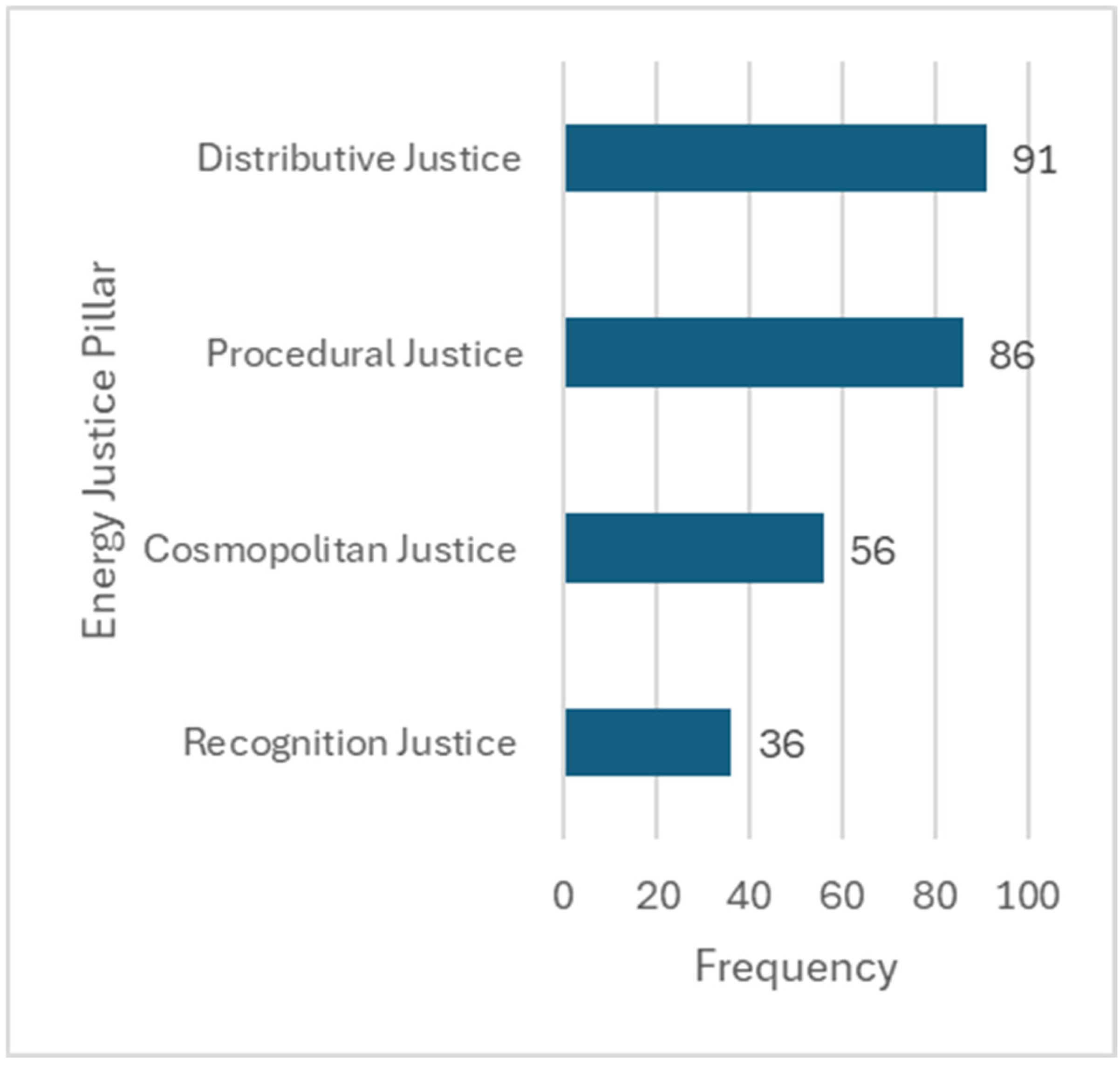

2.1. The Triumvirate Approach of Energy Justice and Implications for Hydrogen Development

2.1.1. Distributive Justice

2.1.2. Procedural Justice

2.1.3. Recognition Justice

2.2. Emerging Tenets of Energy Justice: Limitations of the Framework

2.3. The Role of Media and Energy Transitions

3. Operational Methods

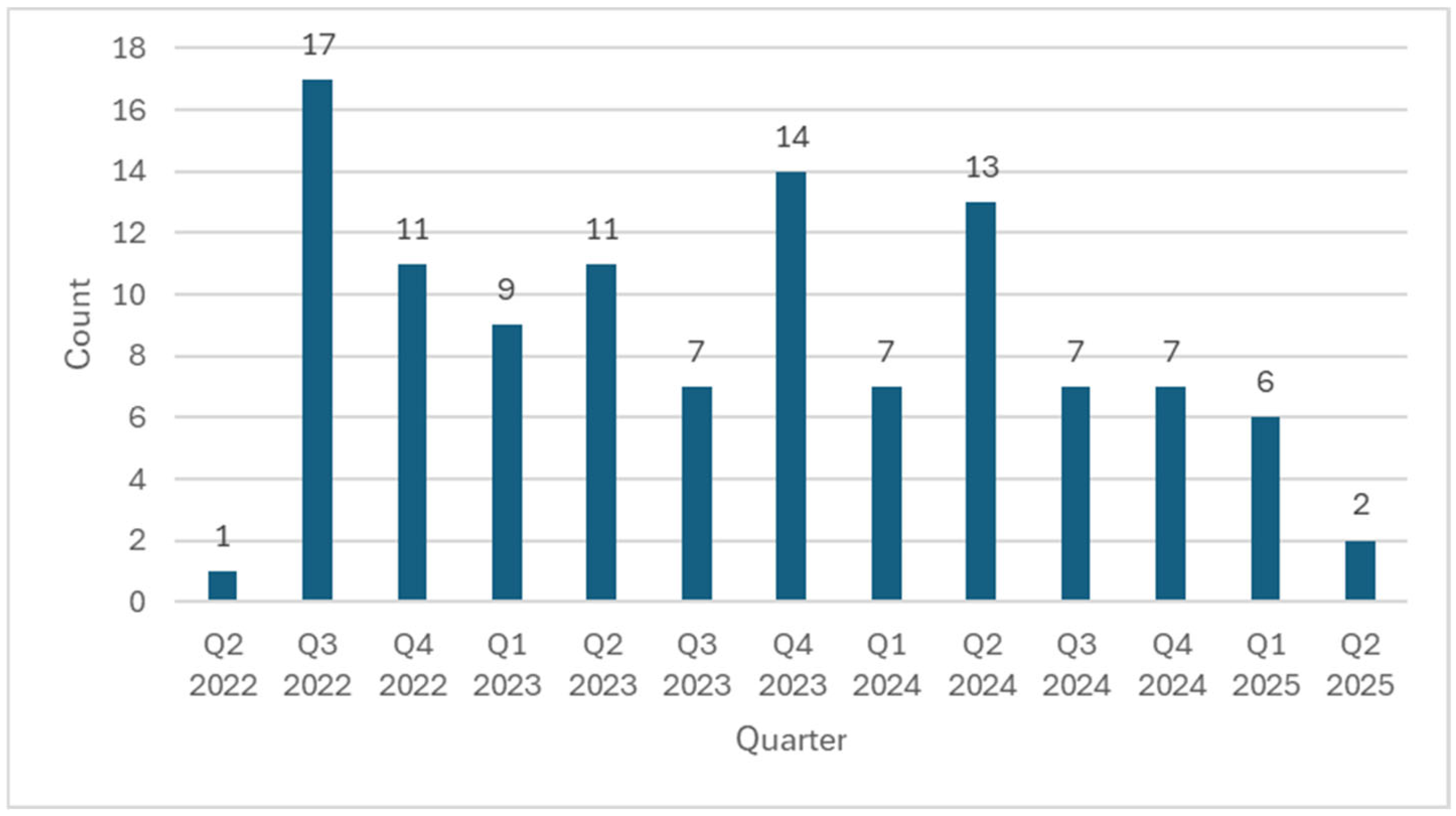

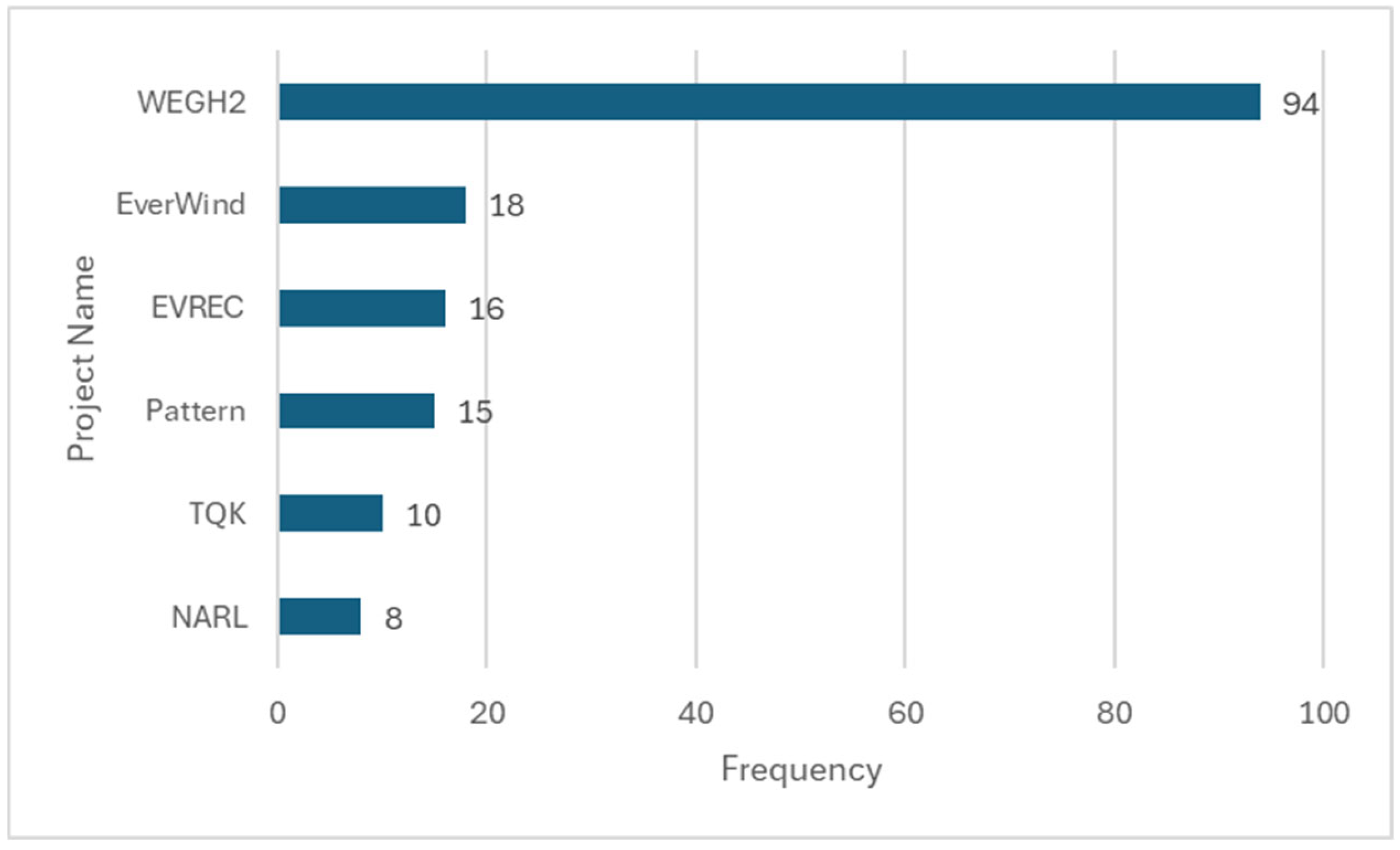

Materials: Media Article Metadata

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Distributive Justice

4.1.1. Distribution of Economic Impacts: Jobs, Capital Investment, Revenue Generation, Public Funding, and Profits

4.1.2. Host Region Bears Ecological and Social Risks

4.1.3. Human Resources: Educational and Demographic Impacts

4.1.4. Distributive Justice: Interpretation and Implications

4.2. Procedural Justice

4.2.1. Environmental Assessment as the Main Consultative Measure

4.2.2. Secondary Consultative Measures and Characteristics of Participation

4.2.3. Contested Developments

4.2.4. Procedural Justice: Interpretation and Implications

4.3. Cosmopolitan Justice

4.3.1. Exports to European Markets

4.3.2. Global Decarbonization and European Energy Security

4.3.3. Cosmopolitan Justice: Interpretation and Implications

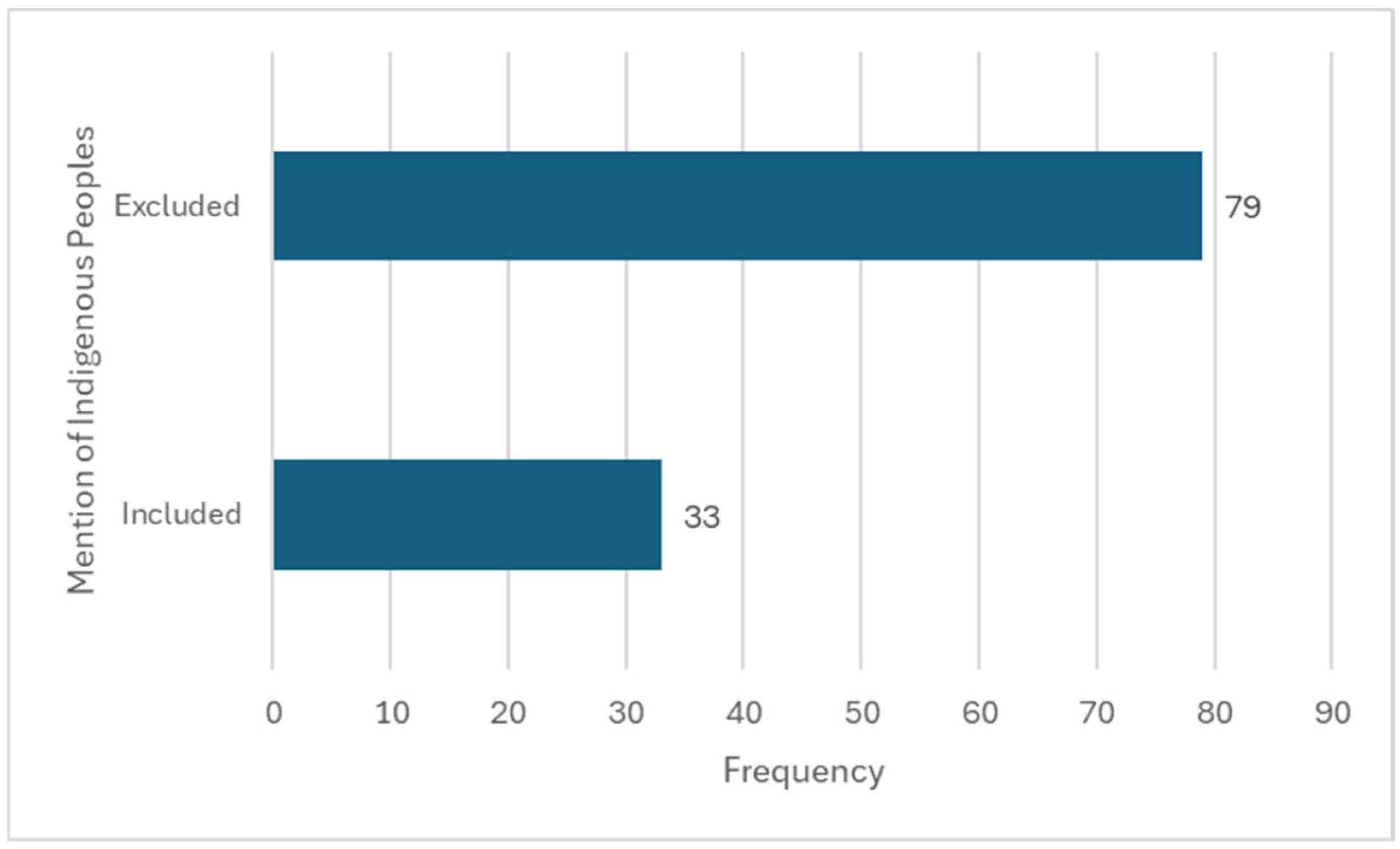

4.4. Recognition Justice

4.4.1. Project Support from Indigenous Leadership: Questioning from Indigenous Membership

4.4.2. Contested Mi’kmaw Lifeway Impacts and Teachings

4.4.3. Misrecognition

4.4.4. Recognition Justice: Interpretation and Implications

4.5. The Importance of Independent Media in Advancing Energy Justice Narratives

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Energy Research & Innovation Initiative. Growler Energy: Final Redacted Version. 2022. Available online: https://energyresearchinnovation.ca/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/E010_Growler-Energy-FINAL-2-Redacted-Version-POST.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Center for Sustainable Systems; University of Michigan. Wind Energy Factsheet; Pub. No. CSS07-09; Center for Sustainable Systems: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2025; Available online: https://css.umich.edu/publications/factsheets/energy/wind-energy-factsheet (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Fisher, K.; Iqbal, M.T.; Fisher, A. Small Scale Renewable Energy Resources Assessment for Newfoundland. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/M-Tariq-Iqbal/publication/347441405_Small_scale_renewable_energy_resources_assessment_for_Newfoundland/links/5fdc0eef45851553a0c6f683/Small-scale-renewable-energy-resources-assessment-for-Newfoundland.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Barrington-Leigh, C.; Ouliaris, M. The renewable energy landscape in Canada: A spatial analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 75, 809–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Renewable Energy Association. By the Numbers; Canadian Renewable Energy Association: Ottawa, ON, Canada. Available online: https://renewablesassociation.ca/by-the-numbers/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Mercer, N.; Sabau, G.; Klinke, A. Wind energy is not an issue for government: Barriers to wind energy development in Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Energy Policy 2017, 108, 673–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBC News. NL Lifts Wind Development Moratorium. 2022. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-wind-moratorium-lifts-1.6409296 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Ministerial Statement—Minister Parsons Announces End of Moratorium on Wind Development. News Release. 5 April 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2022/iet/0405n07/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Update Provided on Wind Development Process. News Release. 26 July 2022. Available online: https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2022/iet/0726n04/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Minister Parsons Launches Hydrogen Development Action Plan for Newfoundland and Labrador. News Release. 14 May 2024. Available online: https://www.gov.nl.ca/releases/2024/iet/0514n01/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Hydrogen Development Action Plan; Department of Industry, Energy and Technology: St. John’s, NL, Canada. Available online: https://www.gov.nl.ca/iet/files/Hydrogen-Development-Action-Plan.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Montevecchi, B. Letter: Oil Companies and the CNLOPB—A Scandalous Relationship. PNI Atlantic. 2017. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/newfoundland-labrador/letter-oil-companies-and-the-cnlopb-a-scandalous-relationship-137380 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Wind Hydrogen Projects; Department of Industry, Energy and Technology: St. John’s, NL, Canada. Available online: https://www.gov.nl.ca/iet/wind-hydrogen-projects/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Meet the Players Behind 8 Companies Pitching Green Hydrogen Projects in N.L. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/hydrogen-companies-energy-nl-1.6859573 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Fish, Food and Allied Workers Union (FFAW). Ongoing Wind Developments. Available online: https://ffaw.ca/inshore/industry-relations/energy-industry-relations/wind/ongoing-wind-developments/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- SaltWire News. Why are Some Community Members Concerned About NL’s Proposed Wind Energy Projects? 2023. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/newfoundland-labrador/why-are-some-community-members-concerned-about-nls-proposed-wind-energy-projects (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- The Independent. ‘No One is Representing Us’: Port au Port Residents Protest Outside EnergyNL Conference. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/news/no-one-is-representing-us-port-au-port-residents-protest-outside-energynl-conference/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Dembi, V. Ensuring Energy Justice in Transition to Green Hydrogen. Electron. J. 2022. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4015169 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Patonia, A. Green hydrogen and its unspoken challenges for energy justice. Appl. Energy 2025, 377, 124674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earthjustice. Reclaiming Hydrogen for a Renewable Future: Distinguishing Oil & Gas Industry Spin from Zero-Emission Solutions. Available online: https://earthjustice.org/feature/green-hydrogen-renewable-zero-emission (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- World Energy Council; Electric Power Research Institute; PwC. National Hydrogen Strategies: Hydrogen on the Horizon—Ready, Almost Set, Go? World Energy Council: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/downloads/Working_Paper_-_National_Hydrogen_Strategies_-_September_2021.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). Geopolitics of the Energy Transformation: The Hydrogen Factor; IRENA: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2022/Jan/IRENA_Geopolitics_Hydrogen_2022.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Lindner, R. Green hydrogen partnerships with the G lobal South. Advancing an energy justice perspective on “tomorrow’s oil”. Sustain. Dev. 2023, 31, 1038–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, K.; McCauley, D.; Heffron, R.; Stephan, H.; Rehner, R. Energy justice: A conceptual review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2016, 11, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D.A.; Heffron, R.J.; Stephan, H.; Jenkins, K. Advancing energy justice: The triumvirate of tenets. Int. Energy Law Rev. 2013, 32, 107–110. [Google Scholar]

- Müller, F.; Tunn, J.; Kalt, T. Hydrogen justice. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 115006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallaire, C.O.; Jekanowski, R.W.; Roberts, J. Left behind: A critical assessment of gender equity in Project Nujio’qonik’s environmental impact statement in the context of Newfoundland’s wind-to-hydrogen industry. Appl. Energy 2025, 394, 125964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Hydrogen Observatory. The European Hydrogen Market Landscape—November 2024; Clean Hydrogen Joint Undertaking: Brussels, Belgium, 2024; Available online: https://observatory.clean-hydrogen.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2024-11/The%20European%20hydrogen%20market%20landscape_November%202024.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Cleveland, C. What Is the Status of Women in the Global Wind Energy Industry? Visualizing Energy. 2023. Available online: https://visualizingenergy.org/what-is-the-status-of-women-in-the-global-wind-energy-industry/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Merten, F.; Krüger, C.; Scholz, A. Assessment of the Advantages and Disadvantages of Hydrogen Imports Compared to Domestic Production; Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment and Energy: Wuppertal, Germany, 2020; Available online: https://wupperinst.org/en/p/wi/p/s/pd/932 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Hydrogen Europe. Hydrogen Production & Water Consumption; Hydrogen Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; Available online: https://hydrogeneurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Hydrogen-production-water-consumption_fin.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Basaria, N. A First Look at Water Demand for Green Hydrogen and Concerns and Opportunities with Desalination. 2024. Available online: https://ptx-hub.org/a-first-look-at-water-demand-for-green-hydrogen-and-concerns-and-opportunities-with-desalination/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Sadat-Razavi, P.; Karakislak, I.; Hildebrand, J. German media discourses and public perceptions on hydrogen imports: An energy justice perspective. Energy Technol. 2025, 13, 2301000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B.K.; Dworkin, M.H. Energy justice: Conceptual insights and practical applications. Appl. Energy 2015, 142, 435–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnstein, S.R. A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1969, 35, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE). Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters; UNECE: Aarhus, Denmark, 1998; Available online: https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/env/pp/documents/cep43e.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Yenneti, K.; Day, R. Procedural (in) justice in the implementation of solar energy: The case of Charanaka solar park, Gujarat, India. Energy Policy 2015, 86, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Uffelen, N. Revisiting recognition in energy justice. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2022, 92, 102764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McHarg, A. Energy justice: Understanding the ‘ethical turn’in energy law and policy. In Energy Justice Energy Law; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer, N.; Martin, D.; Wood, B.; Hudson, A.; Battcock, A.; Atkins, T.; Oxford, K. Is ‘eliminating’ remote diesel-generation just? Inuit energy, power, and resistance in off-grid communities of NunatuKavut. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 118, 103739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio Calzadilla, P.; Mauger, R. The UN’s new sustainable development agenda and renewable energy: The challenge to reach SDG7 while achieving energy justice. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2018, 36, 233–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano-Chamorro, C.; Gurney, G.G.; Cinner, J.E. Advancing procedural justice in conservation. Conserv. Lett. 2022, 15, e12861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caradonna, J.L. Sustainability: A History; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heffron, R.J.; McCauley, D. The concept of energy justice across the disciplines. Energy Policy 2017, 105, 658–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsbøl, A. Energy transition in and by the local media. Nord. Rev. 2013, 34, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyytimäki, J.; Nygrén, N.A.; Pulkka, A.; Rantala, S. Energy transition looming behind the headlines? Newspaper coverage of biogas production in Finland. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2018, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antal, M.; Karhunmaa, K. The German energy transition in the British, Finnish and Hungarian news media. Nat. Energy 2018, 3, 994–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roche, L.; Arendt, R.; Bach, V.; Finkbeiner, M. The social impacts of resource extraction for the clean energy transition: A qualitative news media analysis. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2023, 13, 101213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, C.; Alexander, A.; Doucette, M.B.; Lewis, D.; Neufeld, H.T.; Martin, D.; Masuda, J.; Stefanelli, R.; Castleden, H. Are the pens working for justice? News media coverage of renewable energy involving Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 57, 101230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M.Q. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunawan, J. Ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research. Belitung Nurs. J. 2015, 1, 10–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N.L.’s Wind-Hydrogen Hype is on Fumes, but This Placentia Bay Project Is Forging Ahead. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-hydrogen-placentia-bay-1.7503543 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Stephenville Mayor, Businesses Still Hopeful as World Energy GH2 Revises Plans for Wind Project. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-wind-pivot-1.7446984 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- As N.L. Firm Pivots, Scientists Say Canada’s Green Hydrogen Dreams Are Far-Fetched. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-green-hydrogen-doubts-1.7390486 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Appeals Denied for World Energy GH2’s Plans on Newfoundland’s West Coast. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/appeals-denied-world-energy-1.7258166 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Proposed Wind Project in Western Newfoundland Gets $128M Federal Development Loan. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-federal-loan-1.7128018 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- 4 Companies Advance to Next Stage of N.L.’s Wind Hydrogen Project Development. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-hydrogen-finalists-1.6952322 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘Hype’ Meets Reality as Canada’s Plans to Export Hydrogen to Germany Stall. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-canada-germany-green-hydrogen-export/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Newfoundland’s Smallest Green Hydrogen Project Becomes 1st to Ink Agreement with a Buyer. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/pattern-energy-argentia-renewables-offtake-agreements-1.7225407 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- They’re Embracing the Energy Future in Placentia Bay, and It’s Giving This Conference a Real Spark. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/placentia-conference-energy-1.7327093 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- How Newfoundland is Becoming a Green Hydrogen Hotbed. Available online: https://www.corporateknights.com/energy/newfoundland-green-hydrogen-hotbed/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Even Without Environmental Approval, N.L.’s 1st Wind-to-Hydrogen Project Seems to Be Full Steam Ahead. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-wind-hydrogen-project-traction-1.7129862 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- N.L. ‘All in on Oil and Gas’ for Decades to Come, Premier Tells Energy Conference in St. John’s. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/energy-nl-conference-opening-day-1.7224049 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind-to-Hydrogen Projects Still in Play Across Newfoundland, as List Gets Whittled to 9. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-hydrogen-projects-granted-first-stage-approval-1.6899769 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Federal Government Signs Agreement with Germany to Sell Canadian Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/canada-germany-hydrogen-deal-1.7146700 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- If N.L. Approves Multiple Hydrogen Projects, Will There Be Enough Workers to Build Them? Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/green-hydrogen-labour-demands-trades-nl-1.6868012 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Hydrogen Plant Proponent Requests Equivalent of 20% of Muskrat Falls Electricity. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-gh2-interconnection-electricity-1.6985343 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- In Megaproject-Weary Newfoundland, a Massive Hydrogen Operation Has Some on Edge. Available online: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/investing/commodities/2024/04/10/in-megaproject-weary-newfoundland-a-massive-hydrogen-operation-has-some-on-edge/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Hydrogen Project Gets Provincial Approval but It Comes with Dozens of Conditions. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wegh2-environment-approval-1.7168450 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- With Eyes on an Emerging Wind Hydrogen Industry, N.L. Trade Schools Gear up to Train the Workforce. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/trade-school-wind-hydrogen-1.6976619 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Korean Company Invests US$50 Million in World Energy’s Newfoundland Hydrogen Plan. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/korean-company-buys-into-world-energy-1.6846576 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Environmental Group Disappointed After Wind-Energy Project Gets Go-Ahead from N.L. Government. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wegh2-environmental-assessment-reactions-1.7169198 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Hundreds Rally in Stephenville in Support of Wind-to-Hydrogen Project. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/rally-wind-hydrogen-stephenville-1.7040538 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘Hydrogen Alliance’ Formed as Canada, Germany Sign Agreement on Exports. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/canada-germany-hydrogen-partnership-nl-1.6559787 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Canada, Germany to Sign Hydrogen Deal in N.L. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/canada-germany-hydrogen-1.6551250 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Company Proposing Multibillion-Dollar Wind-to-Ammonia Project for Central Newfoundland. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/evrec-marine-group-wind-hydrogen-ammonia-botwood-grand-falls-central-1.6754995 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Parsons, Furey in the Netherlands to ‘Sell, Sell, Sell’ Newfoundland as Hydrogen Powerhouse. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/andrew-parsons-world-hydrogen-summit-1.6838247 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- N.L. Releases Wind-Hydrogen Fiscal Framework, Says Citizens Will Be ‘Primary Beneficiaries’ of Project. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-hydrogen-project-fiscal-framework-1.6758195 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Wants to Sell Power to Hydro Each Winter—And Claims It Will Have Lots of It. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-selling-power-nl-hydro-green-hydrogen-1.7055046 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Newfoundland’s Dreams of a Wind-Powered Hydrogen Future Are Starting to Take Shape. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-newfoundland-hydrogen-wind-power/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Hydrogen Race: Pattern Energy Pulls Ahead of the Pack, Inks Deal for Private Land in Argentia. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/pattern-energy-port-of-argentia-deal-reached-1.6865547 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘May the Best Bid Win’: Hydro CEO Can See Hydrogen Wind Farms as Part of Future Plans. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-hyrdro-jennifer-williams-green-hydrogen-wind-1.7058830 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Wind Energy Proposal Is Back Before the N.L. Government. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wegh2-imact-statement-1.7102133 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Timeline for Massive N.L. Wind Project ‘Extremely Ambitious,’ Consultant Says. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-energy-timelines-canada-germany-deal-nl-1.6558549 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind Energy Companies Have Their Sights on 1.6 Million Hectares of Crown Land. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-energy-land-map-1.6644654 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind Energy Companies Can Now Bid on Nearly 1.7 Million Hectares of Crown Land in Newfoundland. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-energy-crown-lands-bids-1.6685624 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Western Newfoundland Wind Project Takes Step Forward with Submission of Environmental Impact Statement. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-gh2-wind-farm-environmental-impact-1.6944733 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Tensions High on Port au Port Peninsula over Wind-Hydrogen Megaproject. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/port-au-port-world-energy-concerns-1.6688210 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Proposed Wind Energy Project in Botwood Has Some on-the-Ground Support. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/proposed-wind-energy-project-in-botwood-has-some-on-the-ground-support-1.6765875 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Mi’kmaw Chiefs Look for Mediator Help to Solve Wind Energy Conflict. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/mi-kmaw-chiefs-mediator-wind-energy-conflict-1.6751861 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind Energy Developer Says Port au Port Proposal Is Just the Start. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-turbines-world-energy-gh2-lewis-hills-1.6519394 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Qalipu Sign Deal with Netherlands-Based Wind Energy Training School. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/qalipu-dob-academy-world-energy-gh2-partnership-1.6839607 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- N.L. Energy Minister Intends to Avoid ‘Screwups’ with Wind Energy. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/wind-energy-newfoundland-timelines-screwups-1.6585462 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Protesters in Mainland Block Road to Wind Power Test Site over Water Supply Fears. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/port-au-port-road-blockage-1.6725920 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- How Does a Wind Farm Make Hydrogen? The Simple Science Behind a Big Proposal. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/hydrogen-explainer-1.6569516 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- John Risley Says Delay in Wind-Hydrogen Plan is No Cause for Alarm. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/risley-government-information-gh2-1.7015632 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind-to-Hydrogen Project Pitched for Stephenville Area. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/risley-hydrogen-project-nl-1.6459631 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- With Hydrogen Deal Set for N.L., Questions About Proposed Wind Projects Remain. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-wind-projects-questions-1.6552883 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Codroy Valley Outfitter Says Wind Turbines will Scare off Moose and Destroy His Business. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/art-ryan-world-energy-1.6966848 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Decision Expected on World Energy GH2 Wind Energy Proposal. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/worldenergy-decision-1.7013601 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Why Newfoundland Is Betting Big on Wind and Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-newfoundland-wind-hydrogen-investment/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Proposed Wind Farm on Port au Port Peninsula Worries Some Residents. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/port-au-port-wind-farm-project-1.6510573 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- RCMP Investigating Damaged Equipment at Wind Power Project Job Site. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/rcmp-damaged-equipment-world-energy-gh2-1.6736047 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Not Enough Public Consultation on Proposed Wind-Energy Project, Says Environmental Advocate. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/not-enough-public-consultation-on-proposed-wind-energy-project-says-environmental-advocate-1.6993028 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- The N.L. Government Needs to Make Women Part of the Green Transition. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/women-green-transition-opinion-1.6855562 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Port au Port Wind Project Needs More Details, Environmental Impact Statement, Rules Minister. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/port-au-port-wind-project-environmental-impact-statement-1.6543100 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Canadian Wind-Hydrogen Project Delayed One Year in Race to First European Exports. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-canadian-wind-hydrogen-project-delayed-one-year-in-race-to-first/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘A Lot of Convincing to Do’: Port au Port Residents Feel Blindsided by Proposed Wind Farm. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/turbines-port-au-port-meeting-1.6513484 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Green Canadian Hydrogen Not an Immediate Solution to Germany’s Energy Worries. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/green-canadian-hydrogen-germany-1.6552712 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Furey Defends Luxury Trip to Lodge Owned by a Friend—A Billionaire with a Hydrogen Plan for Newfoundland. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/furey-lodge-trip-1.6622230 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- In the Face of Doubts, Nova Scotia Remains Bullish on Green Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/green-hydrogen-nova-scotia-doubts-1.7433353 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- N.L.’s Hydrogen Companies Want Strict Rules to Avoid Subsidies for ‘Adulterated’ Competitors. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/hydrogen-tax-credit-canada-1.7063767 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind Project Will Drive People out of Port au Port Peninsula, Residents Fear. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/port-au-port-public-response-1.7034831 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Not Just an Oil Expo: Energy N.L. Conference Kicks off with Hubbub Around Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/energy-nl-annual-conference-day-1-hydrogen-oil-1.6858247 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Smellie, S. Newfoundland Wind-to-Hydrogen Company Eyes Data Centre as International Market Lags. CBC News. 2024. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/newfoundland-wind-to-hydrogen-company-eyes-data-centre-as-international-market-lags-1.7387847 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Buys Stephenville Port to Clear the Way for Producing and Shipping Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-gh2-stephenville-port-1.6862116 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Exec Denies Conflict of Interest Involving Furey’s Fishing Trip. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/leet-world-energy-furey-conflict-1.6633185 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- John Risley Doubles down on Sustainable Aviation Fuel with California Plant Expansion. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/john-risley-saf-1.7030340 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Blockades put Entire Green Hydrogen Project at Risk, World Energy GH2 Tells Court. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-world-energy-gh2-court-injunction-protests-1.6744244 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 Offers $10M to Port au Port Communities If Wind Project Goes Ahead. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/world-energy-gh2-funding-for-nl-communities-1.6612349 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Newfoundland and Labrador Picks Four Wind Farm Projects to Power Hydrogen Plants. Available online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-newfoundland-and-labrador-picks-four-wind-farm-projects-to-power-2/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Here’s Where Experts Say the Jobs in the ‘Just Transition’ to Green Energy Will Be Found. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/signal-jobs-just-transition-1.7177590 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- John Risley Downplays Concerns About Flying Stephenville Town Councillors on His Private Jet. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-john-risley-stephenville-delegation-private-jet-1.6671033 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Stephenville Councillors Flew Back from Conference in Germany on John Risley’s Private Jet. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/nl-stephenville-council-hydrogen-risley-private-jet-1.6666653 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Argentia Will Be ‘a First Mover of Hydrogen’ in Global Transition, Says Deputy PM. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/freeland-port-of-argentia-1.6950032 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- No Crown Land, No Problem: Pattern Energy Says Wind Farm Is Full Steam Ahead in Argentia. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/pattern-energy-no-crown-lands-1.6953680 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- New Conflict of Interest Questions from Opposition Around Furey, Wealthy Friends. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/furey-conflict-of-interest-1.6643371 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Canada-Germany Hydrogen Deal Could Be ‘Game Changer,’ Though Skepticism Remains. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/hydrogen-deal-canada-germany-reaction-1.6560538 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Port au Port Wind Project Needs Full Federal Assessment, Not ‘Dinky Toy’ Provincial One, Says Critic. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/hydrogen-environmental-assessement-1.6984841 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- An Oversized Oil Project Has Floated Away from Argentia. So What’s Next for the Port? Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/argentia-port-future-1.7534513 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Stephenville Mayor Sees Potential in World Energy GH2 Making Changes to Its Wind Energy Project. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/newfoundland-labrador/potential-changes-possible-to-world-energy-gh2-project (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Hold on to Your Gigawatts. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/commentary/energy-futures/hold-on-to-your-gigawatts/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Appealing the Mega-Destruction of Wind-to-Hydrogen. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/commentary/appealing-the-mega-destruction-of-wind-to-hydrogen/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- More Federal Funding Needed to Export Canadian Hydrogen to Germany. Available online: https://vocm.com/2025/03/24/more-federal-funding-needed-to-export-canadian-hydrogen-to-germany/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- I Smell Cucumbers. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/commentary/i-smell-cucumbers/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- On Eve of Canada’s Green Energy Pact with Germany, N.L. Wind Farm Project Awaits Approval. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/risley-wind-project-canada-germany-1.6558513 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2 is Blowin’ a Gale: A Look at Green Hydrogen Production on the West Coast of Newfoundland. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/news/investigation/world-energy-gh2-is-blowin-a-gale-a-look-at-green-hydrogen-production-on-the-west-coast-of-newfoundland/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘Standing up for the People who Want to Live in Rural Newfoundland’: Residents Protesting Wind Energy Projects Feel They Are Not Being Heard. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/standing-up-for-the-people-who-want-to-live-in-rural-newfoundland-residents-protesting-wind-energy-projects-feel-they-are-not-being-heard-101005911 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘Exploitation of the Exploits region’: Point Leamington Resident Concerned with Long-Term Impact of Wind Energy Project. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/newfoundland-labrador/nl-residents-concerned-exploits-wind-energy-project (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- LETTER: Is Newfoundland the Next Easter Island? Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/letter-is-newfoundland-the-next-easter-island-100982188 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Protect NL Takes Its Message on Wind Energy Projects Across Province. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/protect-nl-takes-its-message-on-wind-energy-projects-across-province-100988953 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- LETTER: Can’t Understand How a ‘Trojan Horse’ Development and an Immense ‘Land Grab’ Could Be a ‘Green Energy’ Solution. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/letter-cant-understand-how-a-trojan-horse-development-and-an-immense-land-grab-could-be-a-green-energy-solution-100964786 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2’s Massive Newfoundland Wind Energy Project Approved by Environment Minister. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/world-energy-gh2s-massive-newfoundland-wind-energy-project-approved-by-environment-minister-100955248 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Wind Talkers: Why Indigenous Groups Across Newfoundland and Canada are Taking the Leap into Green Energy. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/wind-talkers-why-indigenous-groups-across-newfoundland-and-canada-are-taking-the-leap-into-green-energy-100795224 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Proposed Central Newfoundland Wind-to-Ammonia Project on Former Abitibi Land Could Mean Creation of Hundreds of Full-Time Jobs. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/proposed-central-newfoundland-wind-to-ammonia-project-on-former-abitibi-land-could-mean-creation-of-hundreds-of-full-time-jobs-100827117 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Long May Your Big Wind Farm Draw: How Will the Proposed West Coast Wind Farm Impact the Environment? Available online: https://theindependent.ca/news/investigation/long-may-your-big-wind-farm-draw-how-will-the-proposed-west-coast-wind-farm-impact-the-environment/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- World Energy GH2’s West Coast Wind Project Gets Green Light. Available online: https://vocm.com/2024/04/09/world-energy-gh2-2-risley/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ‘It’s Not Going to Be a Beautiful Place Anymore’: N.L. Wind Project Echoes Muskrat Falls, Says Avalon Chapter of the Council of Canadians. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/its-not-going-to-be-a-beautiful-place-anymore-nl-wind-project-echoes-muskrat-falls-says-avalon-chapter-of-the-council-of-canadians-100950297 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Newfoundland’s Port of Argentia Reaches Deal for Proposed Wind-to-Ammonia Energy Project. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/newfoundlands-port-of-argentia-reaches-deal-for-proposed-wind-to-ammonia-energy-project-100860484 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Braya Eyeing Chance to Use Green Hydrogen at Newfoundland Biofuel Refinery. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/braya-eyeing-chance-to-use-green-hydrogen-at-newfoundland-biofuel-refinery-100832894 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Residents Call for Public Hearings on Controversial Wind-to-Hydrogen Project. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/news/residents-call-for-public-hearings-on-controversial-wind-to-hydrogen-project/ (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Group Opposed to Port au Port Wind Project say N.L. Government Conditions not Stringent Enough. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/group-opposed-to-port-au-port-wind-project-say-nl-government-conditions-not-stringent-enough-100956793 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Protesters Held Back by Police as Canada-EU Summit Kicks off in St. John’s Brewpub. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/canada-eu-summit-kickoff-1.7038415 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- As Details About Everwind’s Burin Peninsula Project Unravel, Misinformation Becoming a Big Issue, Says Marystown Mayor. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/as-details-about-everwinds-burin-peninsula-project-unravel-misinformation-becoming-a-big-issue-says-marystown-mayor-100925044 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Province Announced NARL Moving Forward with Wind Hydrogen Project and Hub for Hydrogen Sector. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/province-announced-narl-moving-forward-with-wind-hydrogen-project-and-hub-for-hydrogen-sector-100981700 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- TREVOR TAYLOR: Harnessing the Wind to Make Hydrogen. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/trevor-taylor-harnessing-the-wind-to-make-hydrogen-100767314 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- ABO’s Wind Project to Produce Energy Equal to Churchill Falls’. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/abos-wind-project-to-produce-energy-equal-to-churchill-falls-100971161 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- N.L. Releases Plan for Hydrogen Sector Development. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/letter-promises-and-fears-tossed-into-the-nl-wind-turbines-100995711 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- LETTER: Promises and Fears Tossed into the N.L. Wind Turbines. Available online: https://www.saltwire.com/atlantic-canada/nl-releases-plan-for-hydrogen-sector-development-100964777 (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 2019, 11, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.K. The pillars of trustworthiness in qualitative research. J. Med. Surg. Public Health 2024, 2, 100051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, N.; Parker, P.; Hudson, A.; Martin, D. Off-grid energy sustainability in Nunatukavut, Labrador: Centering Inuit voices on heat insecurity in diesel-powered communities. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2020, 62, 101382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBC News. Map. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/newsblogs/community/editorsblog/map.pdf (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Broadcast Dialogue. Online/Digital Media News 173. Available online: https://broadcastdialogue.com/online-digital-media-news-173/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- The Independent. About. Available online: https://theindependent.ca/about/ (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Bouma, J.A.; Van Beukering, P.J. (Eds.) Ecosystem Services: From Concept to Practice; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Feldpausch-Parker, D.; Endres, D. Energy democracy. In Routledge Handbook of Energy Democracy; Feldpausch-Parker, D., Endres, D., Peterson, T., Gomez, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2021; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, N.A. Can direct democracy deliver an alternative to extractivism? An essay on popular consultations. Political Geogr. 2022, 98, 102715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, J.; Cunsolo, A.; Morris, R. A half century in the making: Governing commercial fisheries through Indigenous marine co-management and the Torngat Joint Fisheries Board. In Arctic Marine Resource Governance and Development; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo-Nieves, L.; Del Río, P. Contribution of renewable energy sources to the sustainable development of islands: An overview of the literature and a research agenda. Sustainability 2010, 2, 783–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rio, P.; Burguillo, M. An empirical analysis of the impact of renewable energy deployment on local sustainability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1314–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río, P.; Burguillo, M. Assessing the impact of renewable energy deployment on local sustainability: Towards a theoretical framework. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 1325–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brander, L.; van Beukering, P.J.H. Trade-offs and decision-support tools for managing ecosystem services. In Ecosystem Services: From Concept to Practice; Bouma, J.A., van Beukering, P.J.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 132–160. [Google Scholar]

- Ah-Voun, D.; Chyong, C.K.; Li, C. Europe’s energy security: From Russian dependence to renewable reliance. Energy Policy 2024, 184, 113856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, R.T. Indigenous Peoples. Newfoundland & Labrador Heritage Web Site. 1997. Available online: https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/indigenous/indigenous-peoples-introduction.php (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- CBC News Indigenous. Mi’kmaw Qalipu Identity Debate Leaves Those Impacted Looking for Self-Determined Solutions. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/mi-kmaw-qalipu-identity-1.6903592 (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. Enrolment. Qalipu.ca. Available online: https://qalipu.ca/enrolment/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Government of Canada. Backgrounder—Creation of the Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation Band; Government of Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2011. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/news/archive/2011/09/backgrounder-creation-qalipu-mi-kmaq-first-nation-band.html (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- CBC News Interactive. Who Belongs in Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation? Available online: https://newsinteractives.cbc.ca/longform/who-belongs-in-qalipu-mikmaq-first-nation/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Qalipu Mi’kmaq First Nation. Background. Available online: https://qalipu.ca/about/background/ (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Brake, J. Chief to Explore Separation from Controversial Mi’kmaq Band. APTN News. 2018. Available online: https://www.aptnnews.ca/national-news/chief-to-explore-separation-from-controversial-mikmaq-band (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Kennedy, A. Churchill Falls Referendum Will Take Deal out of Political Arena, Wakeham Says. CBC News. 2025. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/churchill-falls-referendum-will-take-deal-out-of-political-arena-wakeham-says-9.6939681 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

| Province: | Installed Wind Capacity (As of End of 2024) |

|---|---|

| Ontario | 5532 MW |

| Quebec | 4072 MW |

| Alberta | 2145 MW |

| Saskatchewan | 818 MW |

| British Columbia | 747 MW |

| Nova Scotia | 620 MW |

| New Brunswick | 397 MW |

| Manitoba | 258 MW |

| Prince Edward Island | 204 MW |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 55 MW |

| ←Strengths-Based Analysis→ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ←Interconnections Amongst Principles→ | ||||

| (1) Distributive Justice: | (2) Procedural Justice: | (3) Recognition Justice: | (4) Cosmopolitan Justice: | (5) Monitor for Emerging Tenets (Restorative, Epistemic, Relational): |

| (A) Egalitarian development | (A) How decision-makers engage the public | (A) Recognition via social arrangements, laws, and status order | (A) Global perspectives | |

| (B) Energy access and affordability | (B) Traits (knowledge mobilization, transparency, institutional representation) | (B) Misrecognition (disrespect, insult, degradation) | (B) Needs of vulnerable peoples beyond host regions | |

| (C) Employment access (gender, ethnicity, etc.) | (C) Sociopolitical context of host region | (C) Cultural and land rights of Indigenous Peoples | ||

| (D) Neocolonialism/extractive industries | (D) Environmental/social impact assessment | (D) Exclusion/Inclusion of Indigenous Peoples | ||

| (E) Ecological risks (water, land-use, etc.) | ||||

| (F) Mechanisms for local benefits | ||||

| Quarter: | Key Events Leading to Media Reports: |

|---|---|

| Q3, 2022 |

|

| Q4, 2022 |

|

| Q2, 2023 |

|

| Q4, 2023 |

|

| Q2, 2024 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mercer, N.M.J. Sustainability: Panacea or Local Energy Injustice? A Qualitative Media Review of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Wind-to-Hydrogen Boom. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411035

Mercer NMJ. Sustainability: Panacea or Local Energy Injustice? A Qualitative Media Review of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Wind-to-Hydrogen Boom. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411035

Chicago/Turabian StyleMercer, Nicholas M. J. 2025. "Sustainability: Panacea or Local Energy Injustice? A Qualitative Media Review of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Wind-to-Hydrogen Boom" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411035

APA StyleMercer, N. M. J. (2025). Sustainability: Panacea or Local Energy Injustice? A Qualitative Media Review of Newfoundland and Labrador’s Wind-to-Hydrogen Boom. Sustainability, 17(24), 11035. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411035