Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Activities: Insights from Institutional Isomorphism Perspective

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Context and Topic Conceptualization

2.1. Education for Sustainable Development

2.2. How Institutional Isomorphism Shapes Organisations

3. Methods

3.1. Research Process

3.2. Data Collecting and Research Sample

4. Results

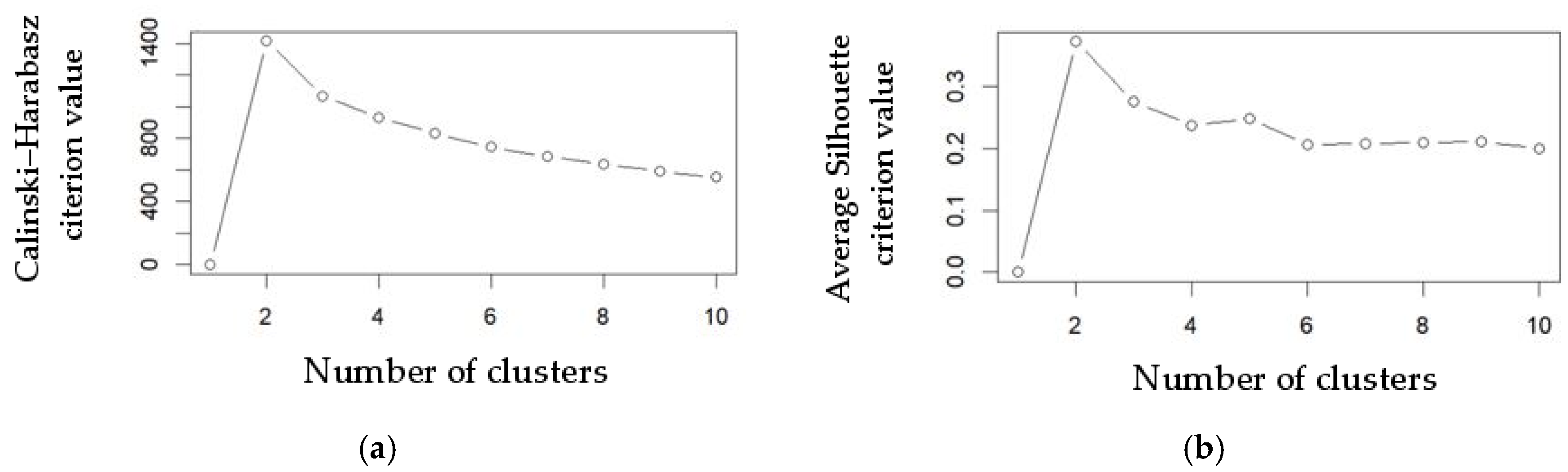

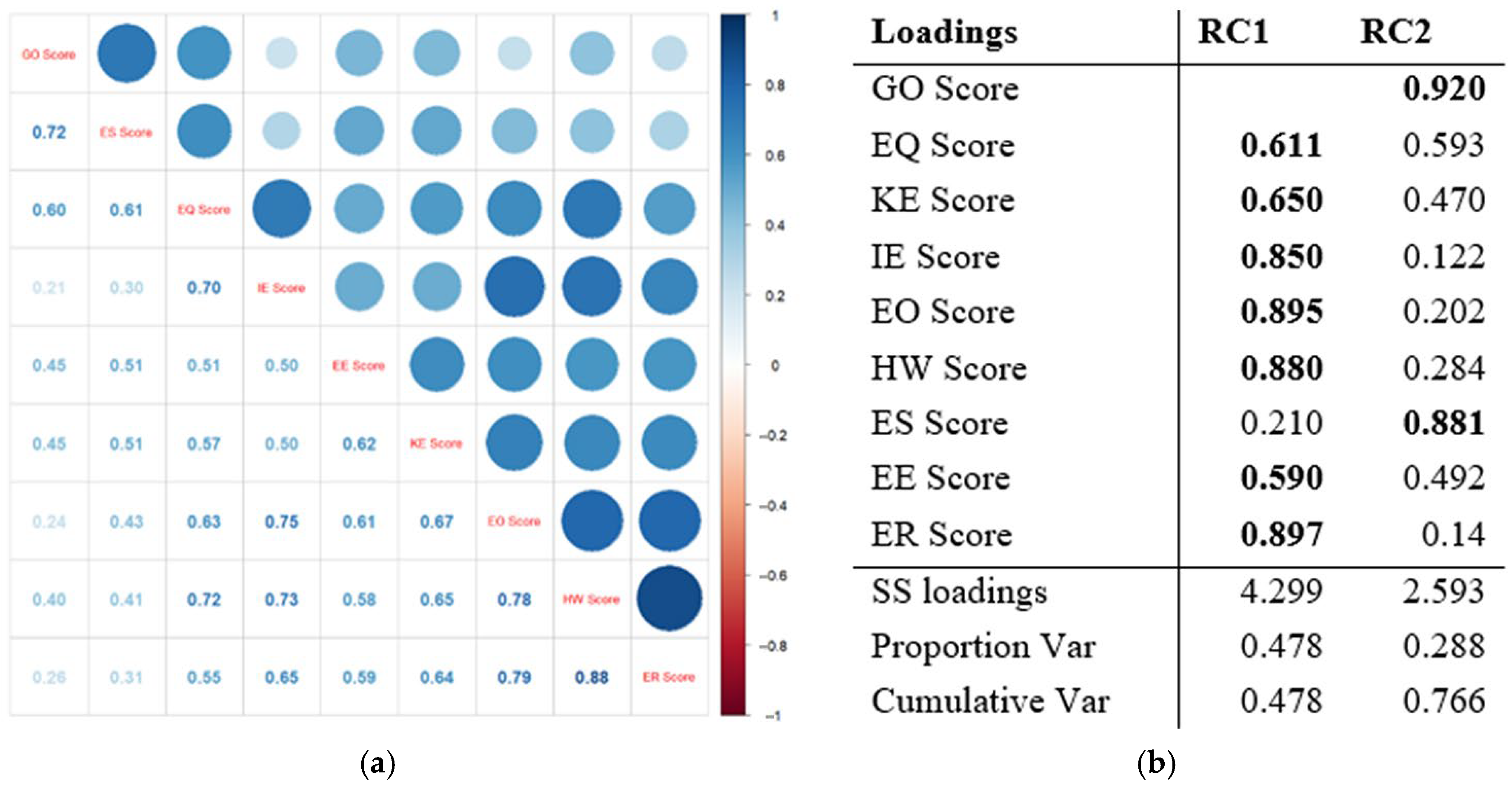

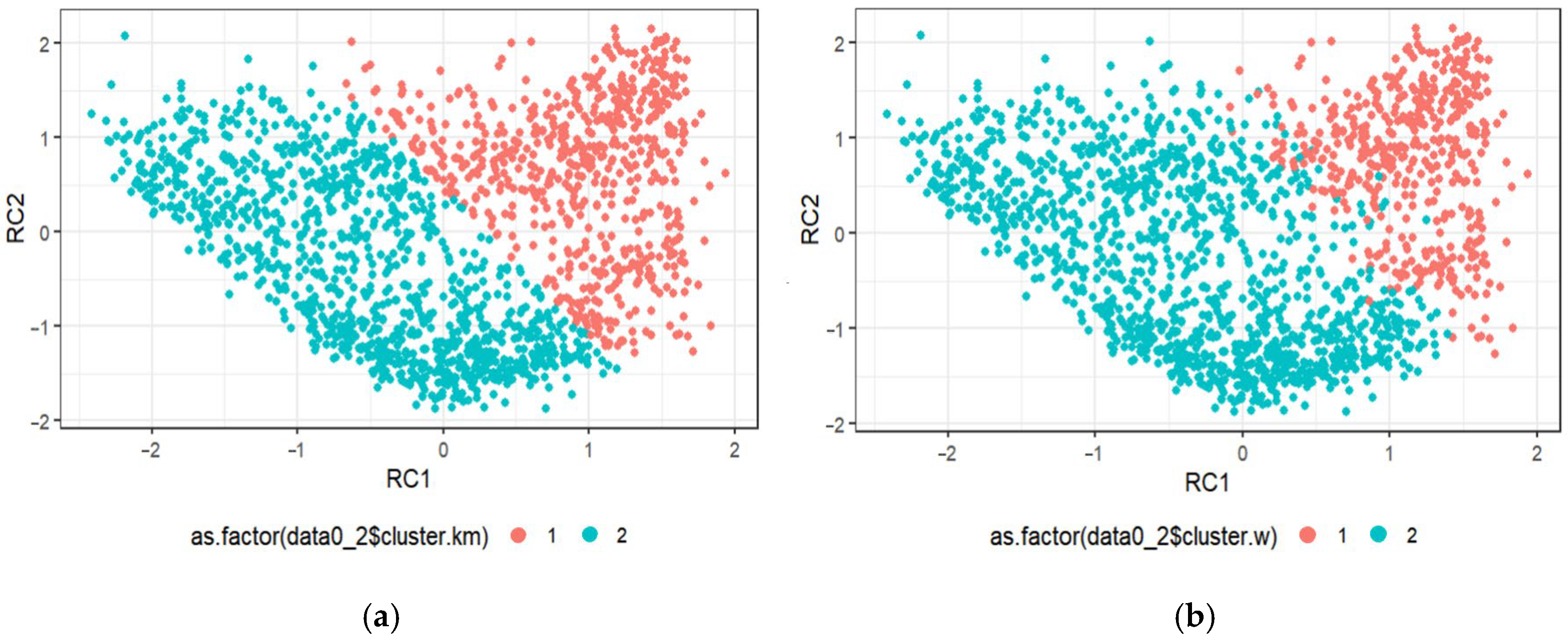

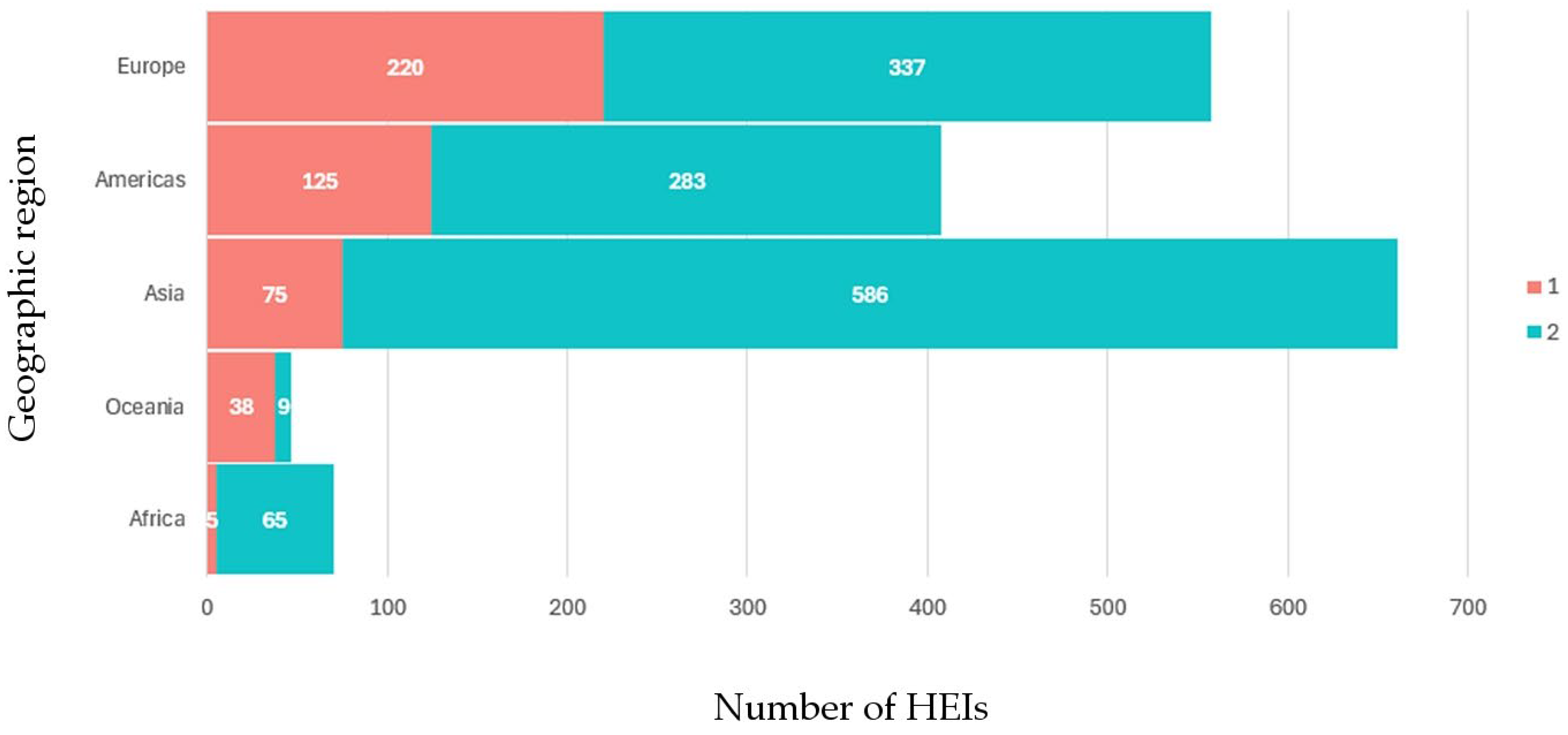

4.1. Stratified Structure of HEIs Ordered by Engagement in Sustainable Development

4.2. Actions Taken by Higher Education Institutions to Include Sustainable Development in Education

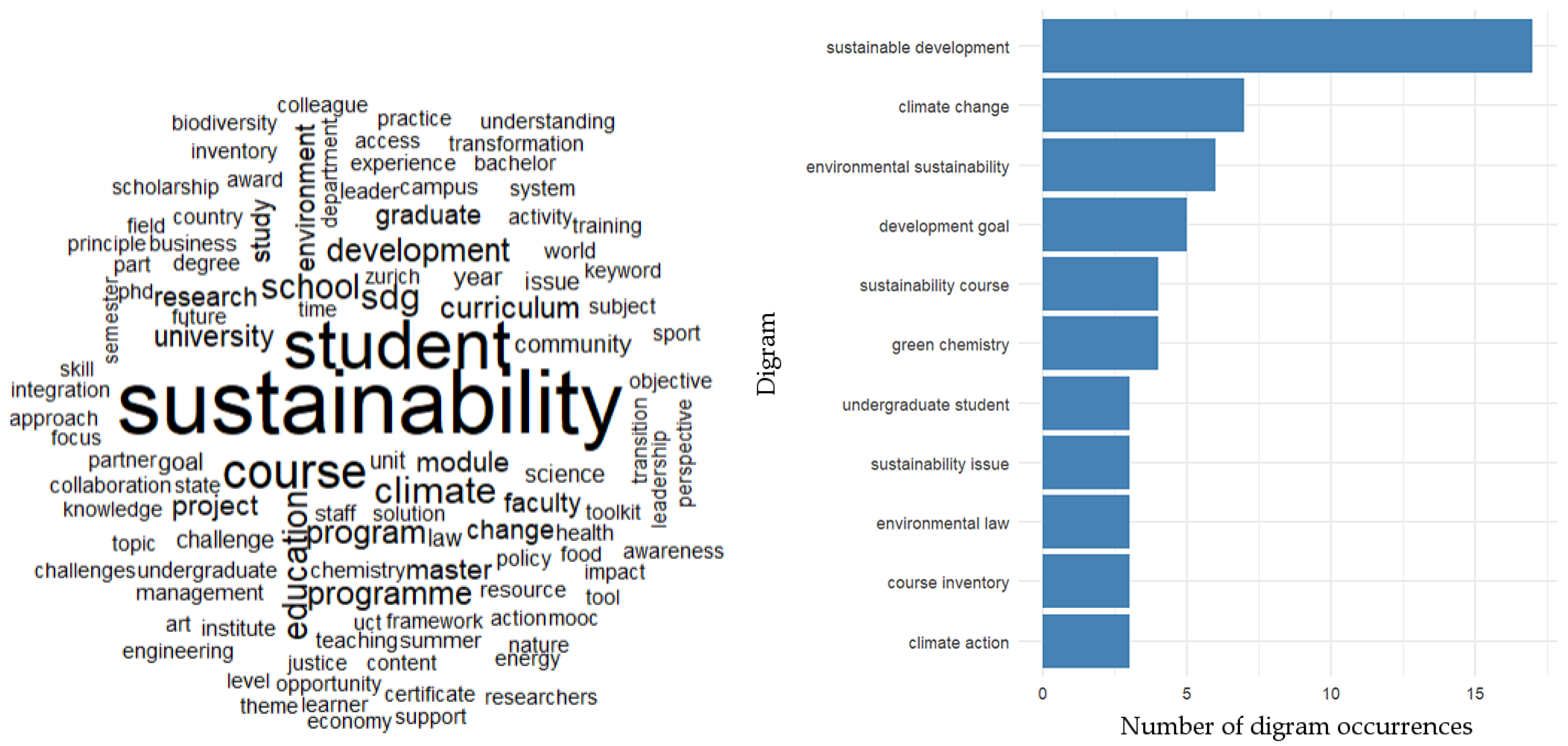

4.2.1. Academic Curricula and Courses

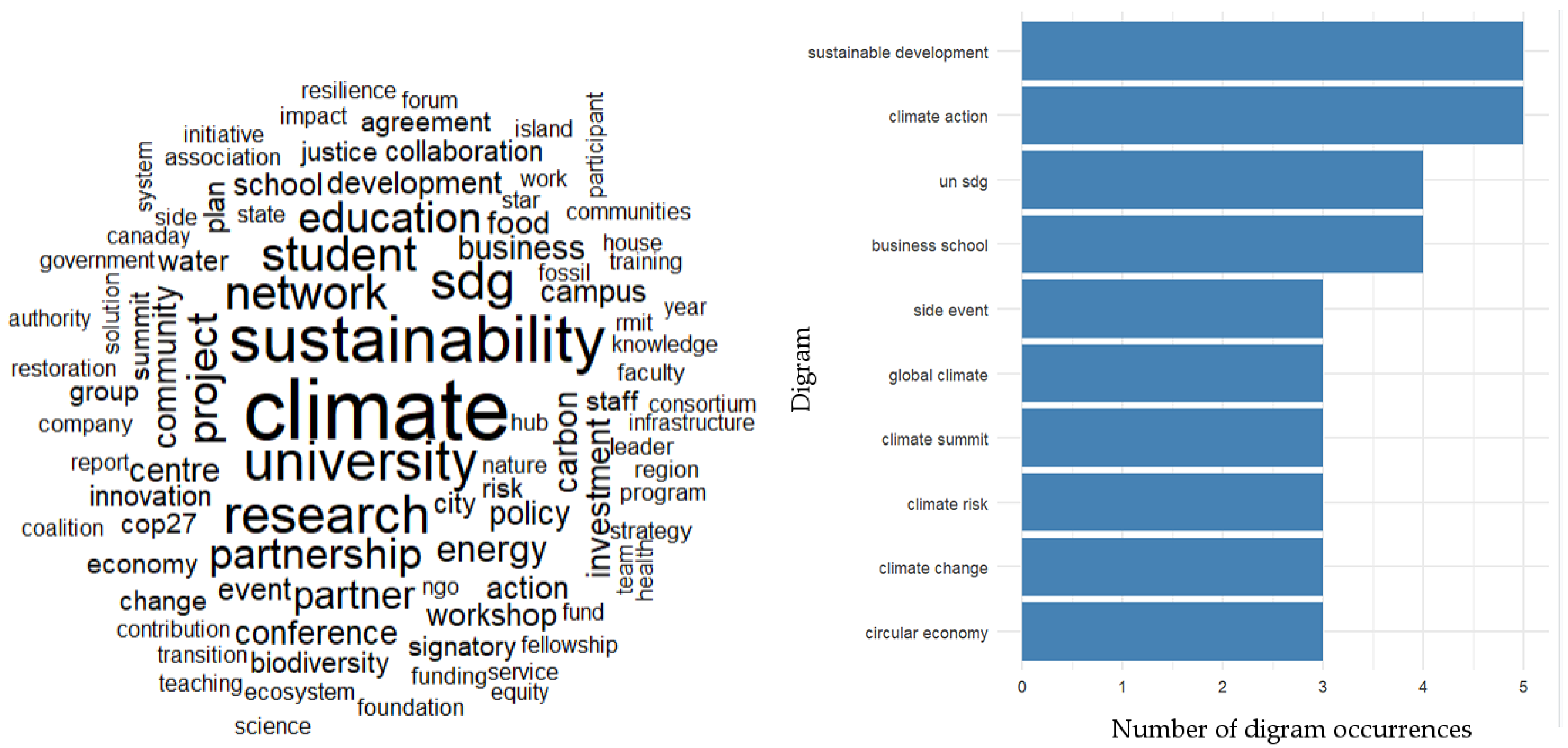

4.2.2. External Collaboration and Partnerships

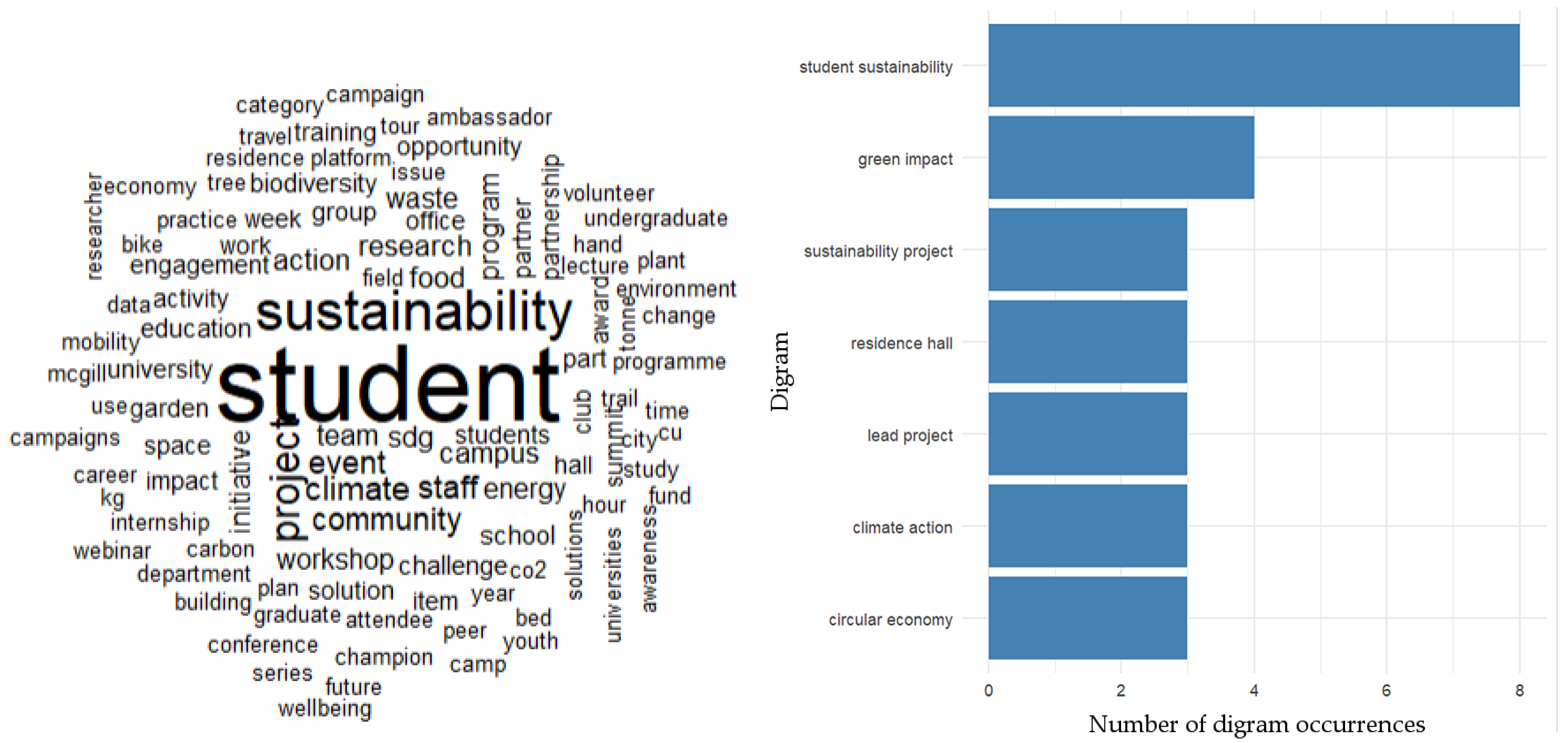

4.2.3. Practical Experience and Student Engagement

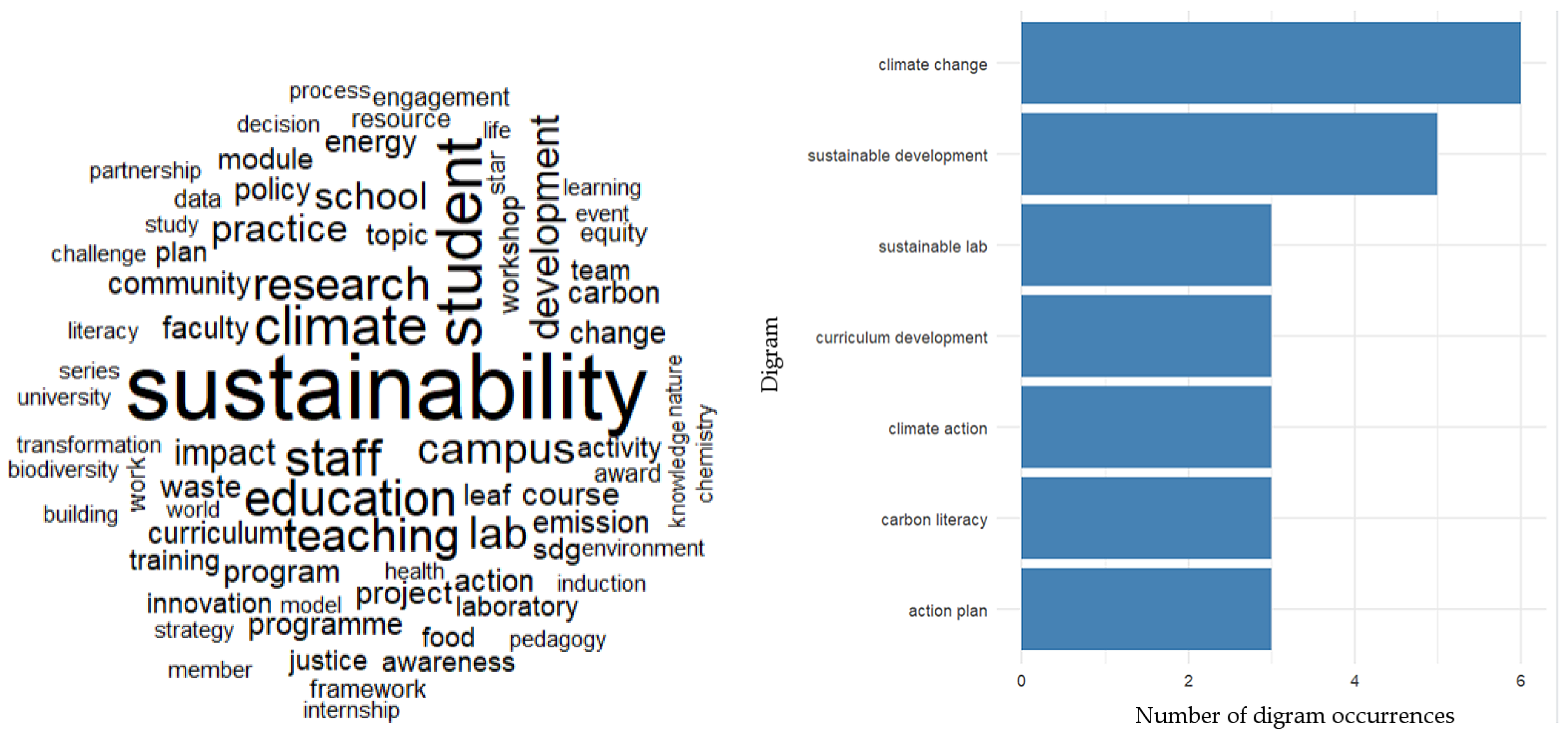

4.2.4. Teaching Methods Supporting Sustainability

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Practical Implications

6.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mo, F.; Wang, D.D. Emerging ESG Reporting of Higher Education Institutions in China. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leal, S.; Azeiteiro, U.M.; Aleixo, A.M. Sustainable Development in Portuguese Higher Education Institutions from the Faculty Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 434, 139863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Carrillo, J.C.; Cadarso, M.A.; Tobarra, M.A. Embracing Higher Education Leadership in Sustainability: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 298, 126675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehn, P.H.; Uitto, J.I. Universities and the Sustainable Development Future: Evaluating Higher-Education Contributions to the 2030 Agenda, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; ISBN 978-1-315-44996-8. [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, J.C.; Graham, A.C. Toward an Empirical Research Agenda for Sustainability in Higher Education: Exploring the Transition Management Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2010, 18, 611–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhulst, E.; Lambrechts, W. Fostering the Incorporation of Sustainable Development in Higher Education. Lessons Learned from a Change Management Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R. The State of Sustainability Reporting in Universities. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2011, 12, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holdsworth, S.; Sandri, O. Investigating Undergraduate Student Learning Experiences Using the Good Practice Learning and Teaching for Sustainability Education (GPLTSE) Framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 311, 127532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1983, 48, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilbury, D. Education for Sustainable Development: An Expert Review of Processes and Learning; UNESCO: Landais, France, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sterling, S. Transformative Learning and Sustainability: Sketching the Conceptual Ground. Learn. Teach. High. Educ. 2010, 5, 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Vargas, V.R.; Salvia, A.L.; Brandli, L.L.; Pallant, E.; Klavins, M.; Ray, S.; Moggi, S.; Maruna, M.; Conticelli, E.; et al. The Role of Higher Education Institutions in Sustainability Initiatives at the Local Level. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1004–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano, R.; Lukman, R.; Lozano, F.J.; Huisingh, D.; Lambrechts, W. Declarations for Sustainability in Higher Education: Becoming Better Leaders, through Addressing the University System. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 48, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M. Implementing Sustainability in Higher Education: Learning in an Age of Transformation; Routledge: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Akinsemolu, A.A.; Onyeaka, H. The Role of Green Education in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals: A Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 210, 115239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardoin, N.M.; Bowers, A.W.; Gaillard, E. Environmental Education Outcomes for Conservation: A Systematic Review. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 241, 108224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manteaw, B.O.; Enu, K.B. Mindscapes and Landscapes: Framing Planetary Health Education and Pedagogy for Sustainable Development in Africa. Glob. Transit. 2025, 7, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Midgley, G.F.; Archer, E.R.M.; Arneth, A.; Barnes, D.K.A.; Chan, L.; Hashimoto, S.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Insarov, G.; Leadley, P.; et al. Actions to Halt Biodiversity Loss Generally Benefit the Climate. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 2846–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Suárez, V.; Acosta-Castellanos, P.M.; Castro Ortegon, Y.A.; Queiruga-Dios, A. Current State of Environmental Education and Education for Sustainable Development in Primary and Secondary (K-12) Schools in Boyacá, Colombia. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzkowitz, H.; Webster, A.; Gebhardt, C.; Terra, B.R.C. The Future of the University and the University of the Future: Evolution of Ivory Tower to Entrepreneurial Paradigm. Res. Policy 2000, 29, 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, L.; Kuppens, T.; Mulà, I.; Staniskiene, E.; Zimmermann, A.B. Do European Quality Assurance Frameworks Support Integration of Transformative Learning for Sustainable Development in Higher Education? Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 148–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milley, P.; Szijarto, B. Understanding Social Innovation Leadership in Universities: Empirical Insights from a Group Concept Mapping Study. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2022, 25, 365–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, H.T.M.; Bui, T.; Pham, B.T. The Role of Higher Education in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals: An Evaluation of Motivation and Capacity of Vietnamese Institutions. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 2024, 22, 101088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiel, C.; Leal Filho, W.; Do Paço, A.; Brandli, L. Evaluating the Engagement of Universities in Capacity Building for Sustainable Development in Local Communities. Eval. Program Plann. 2016, 54, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, K.; Molderez, I.; Van Liedekerke, L. Sustainability Reporting in Higher Education: A Comprehensive Review of the Recent Literature and Paths for Further Research. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 106, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Dinis, M.A.P.; Sivapalan, S.; Begum, H.; Ng, T.F.; Al-Amin, A.Q.; Alam, G.M.; Sharifi, A.; Salvia, A.L.; Kalsoom, Q.; et al. Sustainability Practices at Higher Education Institutions in Asia. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2022, 23, 1250–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M.; Rieckmann, M. Academic Staff Development as a Catalyst for Curriculum Change towards Education for Sustainable Development: An Output Perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 26, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijen, F.; Ansari, S. Overcoming Inaction through Collective Institutional Entrepreneurship: Insights from Regime Theory. Organ. Stud. 2007, 28, 1079–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbano, V.M.; Arena, M.; Azzone, G.; Mayeres, M. Sustainable Development in Higher Education: An In-Depth Analysis of Times Higher Education Impact Rankings. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 501, 145302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortese, A. The Critical Role of Higher Education in Creating a Sustainable Future. Plan. High. Educ. 2003, 31, 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Podgórska, M.; Zdonek, I. Interdisciplinary Collaboration in Higher Education towards Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 32, 2085–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiam, S.; Aziz, F.; Kushitor, S.B.; Amaka-Otchere, A.B.K.; Onyima, B.N.; Odume, O.N. Analyzing the Contributions of Transdisciplinary Research to the Global Sustainability Agenda in African Cities. Sustain. Sci. 2021, 16, 1923–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P.J.; Powell, W.W. The Iron Cage Revisited Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. In Advances in Strategic Management; Emerald (MCB UP): Bingley, UK, 2000; Volume 17, pp. 143–166. ISBN 978-0-7623-0661-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S. Foreign Direct Investments: Examining the Roles of Democracy, Corruption and Judicial Systems across Countries. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. 2019, 21, 2–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Fuller, D.B.; Zheng, L. Institutional Isomorphism and Chinese Private Corporate Philanthropy: State Coercion, Corruption, and Other Institutional Effects. Asian Bus. Manag. 2018, 17, 83–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troisi, R. Illegal Land Use by Italian Firms: An Empirical Analysis through the Lens of Isomorphism. Land Use Policy 2022, 121, 106321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aizawa, A. Institutional Isomorphism in Japanese Firms’ Compliance Activities. Ann. Bus. Adm. Sci. 2018, 17, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K.; Wong, C.W.Y.; Cheng, T.C.E. Institutional Isomorphism and the Adoption of Information Technology for Supply Chain Management. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoako, G.K.; Adam, A.M.; Arthur, C.L.; Tackie, G. Institutional Isomorphism, Environmental Management Accounting and Environmental Accountability: A Review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 11201–11216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob Nsiah-Sarfo, D.; Ofori, D.; Agyapong, D. Sustainable Procurement Implementation among Public Sector Organisations in Ghana: The Role of Institutional Isomorphism and Sustainable Leadership. Clean. Logist. Supply Chain 2023, 8, 100118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungkung, R.; Sorakon, K.; Sitthikitpanya, S.; Gheewala, S.H. Analysis of Green Product Procurement and Ecolabels towards Sustainable Consumption and Production in Thailand. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 28, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutheewasinnon, P.; Hoque, Z.; Nyamori, R.O. Development of a Performance Management System in the Thailand Public Sector: Isomorphism and the Role and Strategies of Institutional Entrepreneurs. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2016, 40, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, T.; Roofe, C.; Cook, L.D. Teachers’ Perspectives on Sustainable Development: The Implications for Education for Sustainable Development. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1343–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stensaker, B.; Lee, J.J.; Rhoades, G.; Ghosh, S.; Castiello-Gutiérrez, S.; Vance, H.; Çalıkoğlu, A.; Kramer, V.; Liu, S.; Marei, M.S.; et al. Stratified University Strategies: The Shaping of Institutional Legitimacy in a Global Perspective. J. High. Educ. 2019, 90, 539–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudambi, R.; Peng, M.W.; Weng, D.H. Research Rankings of Asia Pacific Business Schools: Global versus Local Knowledge Strategies. Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2008, 25, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montenegro De Lima, C.R.; Coelho Soares, T.; Andrade De Lima, M.; Oliveira Veras, M.; Andrade Guerra, J.B.S.O.D.A. Sustainability Funding in Higher Education: A Literature-Based Review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Filippo, D.; Casani, F.; Sanz-Casado, E. University Excellence Initiatives in Spain, a Possible Strategy for Optimising Resources and Improving Local Performance. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2016, 113, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, C.-H. How Foreign Knowledge Spillovers by Returnee Managers Occur at Domestic Firms: An Institutional Theory Perspective. Int. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 625–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.; Belkhouja, M.; Wei, Y.; Lee, S. Born to Be Similar? Global Isomorphism and the Emergence of Latecomer Business Schools. Int. Bus. Rev. 2021, 30, 101863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyfried, M.; Ansmann, M.; Pohlenz, P. Institutional Isomorphism, Entrepreneurship and Effectiveness: The Adoption and Implementation of Quality Management in Teaching and Learning in Germany. Tert. Educ. Manag. 2019, 25, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R.E.; Boxenbaum, E. Exploring European-Ness in Organization Research. Organ. Stud. 2010, 31, 737–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zdonek, I.; Zdonek, D.; Król, K.; Halva, J. Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Activities: Insights from Institutional Isomorphism Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411034

Zdonek I, Zdonek D, Król K, Halva J. Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Activities: Insights from Institutional Isomorphism Perspective. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411034

Chicago/Turabian StyleZdonek, Iwona, Dariusz Zdonek, Karol Król, and Josef Halva. 2025. "Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Activities: Insights from Institutional Isomorphism Perspective" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411034

APA StyleZdonek, I., Zdonek, D., Król, K., & Halva, J. (2025). Sustainability-Oriented Higher Education Activities: Insights from Institutional Isomorphism Perspective. Sustainability, 17(24), 11034. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411034