Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Dynamic Flexible Job Shops: A Review

Abstract

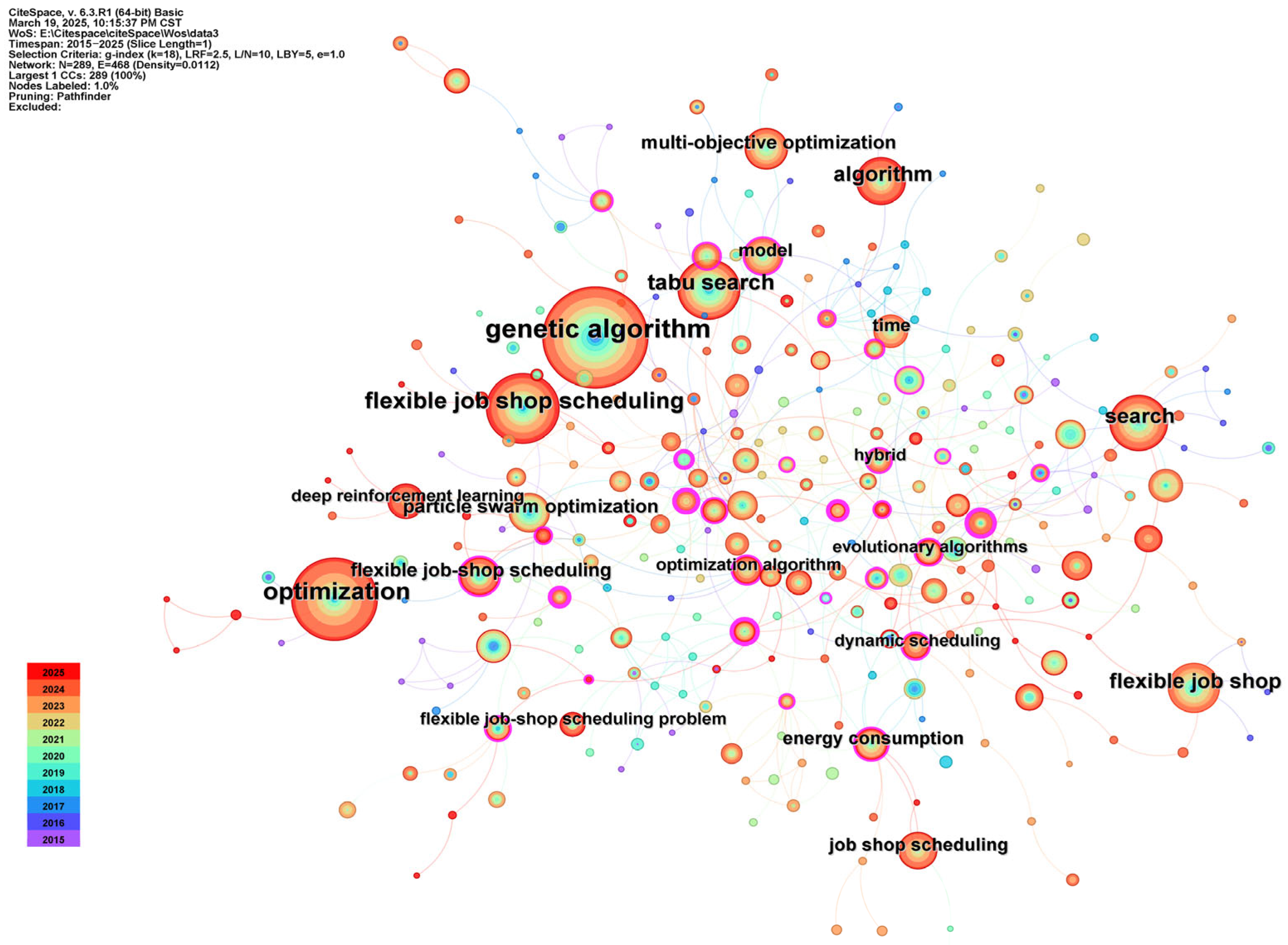

1. Introduction

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

- Stage 1:

- Initial Screening (Title and Abstract)

- Focus on scheduling problems within a flexible job shop environment.

- Explicitly consider energy consumption (or related terms such as energy-saving and carbon emission) as one of the optimization objectives.

- Focused on other production systems.

- Did not set energy consumption as an objective.

- Were review articles, retracted publications, or not journal articles.

- Stage 2:

- Full-Text Assessment

2.2. Analysis of Literature

3. Problem Description

3.1. Workshop Scheduling Model

3.2. Scheduling Goal

3.2.1. Maximum Completion Time

3.2.2. Energy Consumption

- (1)

- Ready Energy consumption (REc): This refers to the energy consumed during equipment startup before processing, shutdown after processing completion, and tool changes. It can be expressed as:where , , and denote the power consumption during machine start-up, shutdown, and tool change, respectively; , , and represent the time durations for startup, shutdown, and tool change, respectively. denotes the number of machine start-up/shut-down events, and is a binary variable indicating whether a tool change is required, where if a tool change is needed, and otherwise.

- (2)

- Processing Energy Consumption (PEc): This refers to the energy consumed during the actual processing of jobs. It can be expressed as:where and denote the power consumption rate and processing time during machine processing, respectively.

- (3)

- Transmission Energy consumption (TEc): It refers to the energy consumption incurred when transferring jobs between two adjacent processing machines. Assuming that the first machine does not generate any transportation energy consumption, it can be expressed as:where and denote the power consumption rate and the time required for transporting the job, respectively. is a binary variable indicating whether the job requires transportation: if transportation is needed, and otherwise.

- (4)

- Idle Energy consumption (IEc): It refers to the energy consumption incurred when machines are idle and waiting to process jobs. It can be expressed as:where and denote the power consumption rate and time duration when the machine is idle, respectively.

- (5)

- Common Energy consumption (CEc): It refers to the energy consumption generated by the workshop environment, primarily including lighting, ventilation, air conditioning, and other auxiliary equipment. As this type of energy consumption remains relatively stable, it can be expressed as:where denotes the total power consumption rate of the workshop’s auxiliary systems, and represents the total processing time.

3.2.3. Total Equipment Load

3.2.4. Production Costs

3.2.5. Customer Satisfaction

3.2.6. Other Scheduling Goals

3.3. Dynamic Event

3.3.1. Job-Related Dynamic Events

- Random Job Arrivals: In practice, jobs do not always arrive according to a fixed schedule. Instead, new orders may arrive unpredictably, requiring real-time schedule adjustments [87]. Failure to respond promptly can result in increased lead times and decreased system responsiveness.

- Uncertain Processing Times: Variability in processing times may arise due to heterogeneity in jobs, operator performance, or subtle environmental changes [73]. This uncertainty can lead to inaccurate schedule execution and degraded machine utilization.

- Due Date Modifications: Due dates may change due to evolving customer requirements or upstream supply chain disruptions [74]. Early or delayed deadlines necessitate rescheduling to minimize tardiness and ensure service level agreements.

- Rush Orders (Emergency Insertions): High-priority jobs that must be inserted into the schedule at short notice can severely disrupt the current plan [75]. Handling such events requires real-time rescheduling methods that can balance urgency with minimal disturbance to existing jobs.

- Order Cancellations: The sudden cancellation of orders results in wasted scheduling effort and can create idle times in machines and labor resources [88]. An adaptive system should be able to reallocate the released capacity efficiently.

3.3.2. Machine-Related Dynamic Events

- Machine Breakdowns: Unexpected machine failures necessitate immediate rescheduling and may lead to bottlenecks or complete stoppages in production lines [85]. Robust scheduling approaches often include redundancy, machine reallocation, or predictive maintenance scheduling.

- Preventive Maintenance: While scheduled in advance, preventive maintenance windows can interfere with planned schedules, especially if not properly synchronized [99]. Effective integration into the scheduling model helps to avoid unnecessary production delays.

- Tool Wear or Breakage: Tool-related issues, such as wear or unexpected damage, can result in lower machining accuracy or process interruptions [100]. Integration of tool condition monitoring with scheduling systems is a promising direction to enhance reliability.

3.3.3. Process-Related Dynamic Events

- Process Delays: Operations may take longer than planned due to technical bottlenecks, human factors, or incomplete work instructions. Delays in early operations can propagate, leading to significant schedule deviations [76].

- Quality Issues: Rework or scrap due to quality defects not only consumes extra processing time but also disrupts the downstream schedule [89]. Incorporating feedback from quality inspection systems can enhance schedule robustness.

- Abnormal Production Setup: Setup processes may deviate from standard times due to incorrect parameter settings, lack of proper tooling, or operator errors. Accurate setup modeling and operator training are vital to reduce such occurrences [90].

3.3.4. Other Dynamic Events

3.4. Category of Dynamic Scheduling

3.4.1. Completely Reactive Scheduling

3.4.2. Predictive–Reactive Scheduling

3.4.3. Robust Scheduling

4. Algorithms for Solving the EDFJSP

4.1. Exact Method and Heuristic Algorithm

4.2. Metaheuristic Algorithm

4.2.1. GA

4.2.2. EA

4.2.3. PSO

4.2.4. ABC

4.2.5. AIA

4.2.6. Other Metaheuristics

4.3. AI Methods

4.3.1. Expert Systems

4.3.2. RL

4.3.3. NNs

4.3.4. MASs

5. Discussion

5.1. Evolution and Challenges of Algorithmic Paradigms

5.2. Evolution and Challenges of Energy-Saving Strategies

5.3. Future Prospects

- (1)

- Advancing from data-driven to physics-informed intelligent decision-making. Future algorithms should evolve from opaque models toward transparent, physics-aware decision systems that deeply incorporate domain knowledge and mechanistic principles. This entails building a hybrid intelligence paradigm that integrates physical constraints, empirical models, and data-driven learning. A particularly interesting technological avenue is the enhanced integration of neural networks and multi-agent systems [150,151]. Processes including equipment energy consumption, mechanical wear, and operator fatigue can be integrated into the loss function of neural networks [152]. For instance, while determining whether to deactivate a briefly inactive device, a solely data-driven reinforcement learning agent may execute this action only based on the observation that “shutdown” has historically led to reduced energy use. An intelligent agent’s decisions will account for the degradation of essential component lifespan due to device cycling, as well as the effect of current on the power grid during the restart phase [153]. Consequently, by optimizing energy consumption, the scheduling system will inherently evaluate and penalize “suboptimal” decisions that may conserve energy in the short term but compromise equipment health or stability in the long term, thus producing more physically viable and economically sound scheduling solutions.

- (2)

- System level energy management. Section 5.2 indicates that contemporary research predominantly implements energy-saving strategies, such as on/off control and speed regulation, in isolation for individual devices, neglecting their cascading effects on the overall production system. Future studies must develop a more complete multi-scale energy model that systematically integrates energy usage with the energy ecology of the entire workshop. This encompasses environmental energy consumption, transportation energy consumption, processing energy consumption, idle energy consumption, and machine on/off energy consumption [154]. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a more sophisticated nonlinear cost model. For equipment start–stop operations, it is essential to move away from the simplistic “switch” paradigm and implement a full cost function that incorporates preheating duration, instantaneous power effects at starting, and equipment wear associated with start–stop cycles. This will encourage the scheduling mechanism to achieve a more realistic equilibrium between “idle energy consumption” and “total cost of start-stop operations.”

- (3)

- Transitioning from benchmark-driven evaluation to empirical validation in real industrial settings. The efficacy of most contemporary algorithms has been substantiated solely in highly simplified simulation environments, rendering them susceptible to the complexities and uncertainties of the real world [155]. To effectively transition from theoretical research to practical applications, future investigations must prioritize empirical proof. The essence is constructing high-fidelity digital twins as virtual simulation environments for algorithms [156]. This digital twin transcends a mere 3D visualization model; it must function as a dynamic system powered by a multi-physics simulation engine and calibrated in real-time using actual production line sensor data. It can precisely emulate physical phenomena, including heat effects, tool degradation, and equipment deterioration during milling and can replicate numerous stochastic disturbances encountered in reality, such as machine malfunctions, job insertion, and worker fatigue impacts. Evaluating algorithms in a meticulously tested high-fidelity twin environment will yield reliability that significantly surpasses that of simulations derived from abstract mathematical models. Ultimately, research will effectively contribute to the green, low-carbon, and sustainable advancement of the manufacturing sector, transitioning from theoretical invention to practical implementation.

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| JSP | Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| DJSP | Dynamic Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| FJSP | Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| EFJSP | Energy-efficient Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| EDFJSP | Energy-efficient Dynamic Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem |

| EC | Evolutionary Computation |

| SI | Swarm Intelligence |

| REc | Ready Energy consumption |

| PEc | Processing Energy consumption |

| TEc | Transmission Energy consumption |

| IEc | Idle Energy consumption |

| CEc | Common Energy consumption |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| DT | Digital Twin |

| GP | Genetic Programing |

| GEP | Gene Expression Programming |

| CP | Constraint Programming |

| DRs | Dispatching Rules |

| GA | Genetic Algorithm |

| SA | Simulated Annealing |

| EA | Evolutionary Algorithm |

| NSGA-II | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II |

| NSGA-III | Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm III |

| MA | Memetic Algorithm |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| AOA | Arithmetic Optimization Algorithm |

| ABC | Artificial Bee Colony |

| AIA | Artificial Immune Algorithm |

| EMA | Electromagnetism-like Mechanism Algorithm |

| FLA | Frog-Leaping Algorithm |

| GWO | Gray Wolf Optimization |

| BWSA | Black Widow Spider Algorithm |

| KBEA | Knowledge-guided Bi-population Evolutionary Algorithm |

| KBOA | Knowledge-based Bi-hierarchical Optimization Algorithm |

| MOEA/D | Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithm with Decomposition |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| NN | Neural Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GRL | Graph Reinforcement Learning |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| MAS | Multi-Agent System |

References

- Lei, K.; Guo, P.; Zhao, W.; Wang, Y.; Qian, L.; Meng, X.; Tang, L. A multi-action deep reinforcement learning framework for flexible Job-shop scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 205, 117796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gong, W.; Lu, C.; Wang, L. A learning-based memetic algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job-shop scheduling with type-2 fuzzy processing time. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brucker, P.; Schlie, R. Job-shop scheduling with multi-purpose machines. Computing 1990, 45, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.S.; Meeran, S. Deterministic job-shop scheduling: Past, present and future. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1999, 113, 390–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Cao, M.; Zhang, F.; Liu, J.; Li, X. Effects of corporate social responsibility on customer satisfaction and organizational attractiveness: A signaling perspective. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2020, 29, 20–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Yang, B.; Li, S.; Wang, S. A self-learning genetic algorithm based on reinforcement learning for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Gao, L.; Shi, Y. An effective genetic algorithm for the flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 3563–3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Sun, L.; Gen, M. A hybrid genetic and variable neighborhood descent algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling problems. Comput. Oper. Res. 2008, 35, 2892–2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira, R.H.; Gnanavelbabu, A.; Vaidyanathan, T. An effective backtracking search algorithm for multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling considering new job arrivals and energy consumption. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouzon, G.; Yildirim, M.B.; Twomey, J. Operational methods for minimization of energy consumption of manufacturing equipment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 4247–4271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Xia, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhou, J.; Chen, M.; Li, K. Energy-Efficient Shop Scheduling Using Space-Cooperation Multi-Objective Optimization. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Comput. 2024, 10, 601–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y. An improved multi-objective evolutionary algorithm for the low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling with automated guided vehicles. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 175, 113048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Li, J. Solving multi-objective energy-efficient flexible job shop problems by a dual-level NSGA-II algorithm. Memetic Comput. 2025, 17, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, J.; Gao, K. A genetic programming based cooperative evolutionary algorithm for flexible job shop with crane transportation and setup times. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 169, 112614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, C.; Wu, R.; Tang, H. Multi-objective fuzzy green scheduling optimization method of special vehicle body-in-white prototype shop considering equipment preventive maintenance. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 462, 142660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Luo, W.; Zhang, W. Fuzzy flexible job shop dynamic scheduling considering machine remaining processing capacity. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2024, 239, 09544054241289976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.J.; Ham, A. Energy-aware flexible job shop scheduling under time-of-use pricing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 248, 108507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, A.; Park, M.J.; Kim, K.M. Energy-Aware Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Using Mixed Integer Programming and Constraint Programming. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 8035806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Chae, M.J.; Yang, Y.; Park, I.B.; Lee, J.; Park, J. Fast scheduling of semiconductor manufacturing facilities using case-based reasoning. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manuf. 2015, 29, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Chen, M.; Zhang, Z.; Tang, D. An adaptive real-time scheduling method for flexible job shop scheduling problem with combined processing constraint. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125113–125121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymourifar, A.; Ozturk, G.; Ozturk, Z.K.; Bahadir, O. Extracting new dispatching rules for multi-objective dynamic flexible job shop scheduling with limited buffer spaces. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 12, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mei, Y.; Nguyen, S.; Zhang, M. Survey on genetic programming and machine learning techniques for heuristic design in job shop scheduling. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2023, 28, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Gala, F.J.; Sierra, M.R.; Mencía, C.; Varela, R. Genetic programming with local search to evolve priority rules for scheduling jobs on a machine with time-varying capacity. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 66, 100944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, H. Learning-driven memetic algorithm for solving integrated distributed production and transportation scheduling problem. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2025, 96, 101945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, H.; Hasani, A. An energy-efficient multi-objective optimization for flexible job-shop scheduling problem. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2017, 104, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Sun, Y. A green scheduling algorithm for flexible job shop with energy-saving measures. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3249–3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, C.; Xu, G.; Chen, Y.; Gao, Z. An energy-saving distributed flexible job shop scheduling with machine breakdowns. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 167, 112276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouiri, M.; Bekrar, A.; Trentesaux, D. An energy-efficient scheduling and rescheduling method for production and logistics systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 3263–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, H.; Liu, J. Scheduling optimization of a wheel hub production line based on flexible scheduling. Int. J. Ind. Eng. 2020, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zou, J.; Wang, W. Digital twin-oriented collaborative optimization of fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling under multiple uncertainties. Sādhanā 2023, 48, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Hu, Y.; Luo, W.; Wang, L.; Wu, R. A multi-objective scheduling method for distributed and flexible job shop based on hybrid genetic algorithm and tabu search considering operation outsourcing and carbon emission. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 157, 107318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. Dynamic energy-efficient scheduling of multi-variety and small batch flexible job-shop: A case study for the aerospace industry. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 178, 109111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, Z.; Tang, Q. Matheuristic and learning-oriented multi-objective artificial bee colony algorithm for energy-aware flexible assembly job shop scheduling problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 133, 108634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J. Hybrid Multi-Objective Artificial Bee Colony for Flexible Assembly Job Shop with Learning Effect. Mathematics 2025, 13, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zheng, Y.; Ahmad, R. An energy-efficient multi-objective scheduling for flexible job-shop-type remanufacturing system. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 66, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.; Tan, C.; Wu, Y.; Yang, B.; Long, X. Research on low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem based on improved Grey Wolf Algorithm. J. Supercomput. 2024, 80, 12123–12153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, G. Energy-Saving Distributed Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Optimization with Dual Resource Constraints Based on Integrated Q-Learning Multi-Objective GreyWolf Optimizer. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 140, 1459–1483. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, N.; Gong, G.; Lu, D.; Huang, D.; Peng, N.; Qi, H. An effective reformative memetic algorithm for distributed flexible job-shop scheduling problem with order cancellation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Li, R.; Gu, Y. A decomposition-based memetic algorithm to solve the biobjective green flexible job shop scheduling problem with interval type-2 fuzzy processing time. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 183, 109513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gu, W.; Yuan, M.; Tang, Y. Real-time data-driven dynamic scheduling for flexible job shop with insufficient transportation resources using hybrid deep Q network. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2022, 74, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Mei, Y.; Nguyen, S.; Zhang, M. Evolving scheduling heuristics via genetic programming with feature selection in dynamic flexible job-shop scheduling. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 51, 1797–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Mei, Y.; Nguyen, S.; Tan, K.C.; Zhang, M. Task relatedness-based multitask genetic programming for dynamic flexible job shop scheduling. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2022, 27, 1705–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Hu, X.; Li, Y.; Liang, M.; Wang, K.; Wang, L.; Tang, H.; Guo, S. A Q-learning-based improved multi-objective genetic algorithm for solving distributed heterogeneous assembly flexible job shop scheduling problems with transfers. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 79, 398–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azam, A.; Ahmed, A.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Knowledge structure and research progress in wind power generation (WPG) from 2005 to 2020 using CiteSpace based scientometric analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 295, 126496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, S.; Tan, L.; Tan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Z.; Hou, C.; Xu, Y.; Liu, S.; Wang, G. Frontier and hot topics in electrochemiluminescence sensing technology based on CiteSpace bibliometric analysis. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 201, 113932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liao, X.; Chen, G.; Hou, Y. Dynamic intelligent scheduling in low-carbon heterogeneous distributed flexible job shops with job insertions and transfers. Sensors 2024, 24, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Y.; Lei, Y.; Cao, H.; Peng, J.; Jia, Y. Energy-aware dynamic rescheduling of flexible manufacturing system using edge-cloud collaborative decision-making method. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2025, 38, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdamar, L.; Birbil, Ş.İ. A hierarchical planning system for energy intensive production environments. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1999, 58, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, R. A New Energy-Aware Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Method Using Modified Biogeography-Based Optimization. Math. Probl. Eng. 2017, 2017, 7249876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Lu, S.; Wang, Q.; Deng, F. A review of flexible job shop scheduling problems considering transportation vehicles. Front. Inf. Technol. Electron. Eng. 2025, 26, 332–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Cao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Z.; Han, Y.; Pan, Q. A review on swarm intelligence and evolutionary algorithms for solving flexible job shop scheduling problems. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2019, 6, 904–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, F.; Zhang, J.; Mei, S.; Song, H. Critical review on the objective function of flexible job shop scheduling. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 8147581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, M.K.; Butt, S.I.; Kousar, R.; Ahmad, R.; Agha, M.H.; Zhang, F.; Faping, Z.; Anjum, N.; Asgher, U. Recent research trends in genetic algorithm based flexible job shop scheduling problems. Math. Probl. Eng. 2018, 2018, 9270802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Shi, H.; Han, C.; Meng, F. Research on production scheduling optimization of flexible job shop production with buffer capacity limitation based on the improved gene expression programming algorithm. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. 2023, 24, 2317–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauzère-Pérès, S.; Ding, J.; Shen, L.; Tamssaouet, K. The flexible job shop scheduling problem: A review. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 314, 409–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Ma, Y.; Chen, L.; Huang, B.; Huang, Y.; Guan, L. A review on intelligent scheduling and optimization for flexible job shop. Int. J. Control Autom. Syst. 2023, 21, 3127–3150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, I.A.; Khan, A.A. A research survey: Review of flexible job shop scheduling techniques. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2016, 23, 551–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renna, P.; Materi, S. A literature review of energy efficiency and sustainability in manufacturing systems. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Huang, Y.; Sadollah, A.; Wang, L. A review of energy-efficient scheduling in intelligent production systems. Complex Intell. Syst. 2020, 6, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, G.G. A review of green shop scheduling problem. Inf. Sci. 2022, 589, 478–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bänsch, K.; Busse, J.; Meisel, F.; Rieck, J.; Scholz, S.; Volling, T.; Wichmann, M.G. Energy-aware decision support models in production environments: A systematic literature review. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 159, 107456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qasim, M.; Wong, K.Y.; Saufi, M.S.R.M. Production planning approaches: A review from green perspective. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 90024–90049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Destouet, C.; Tlahig, H.; Bettayeb, B.; Mazari, B. Flexible job shop scheduling problem under Industry 5.0: A survey on human reintegration, environmental consideration and resilience improvement. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 67, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Lei, D.; Wang, L. A bi-population evolutionary algorithm with feedback for energy-efficient fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2021, 52, 5295–5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ji, Z. Multi-objective optimization scheduling for manufacturing process based on virtual workflow models. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 122, 108786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, Y.; Wang, T. A multi-objective optimization method for flexible job shop scheduling considering cutting-tool degradation with energy-saving measures. Mathematics 2023, 11, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Yi, Q. Influence factors and operational strategies for energy efficiency improvement of CNC machining. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 161, 220–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.L.; Zha, J.; Feng, Z.Y.; Liu, S.F.; Wu, S.S.; Zhu, Z.Y. Flexible job shop rescheduling scheme selection using improved TOPSIS. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2024, 23, 507–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; Li, R.; Liu, S.Q.; Tang, B.; Li, S.; Masoud, M. An improved sparrow search algorithm for solving the energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling problem. Machines 2022, 10, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, Y. Rescheduling optimisation of sustainable multi-objective fuzzy flexible job shop under uncertain environment. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 62, 8904–8920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Li, C.; Tang, Y.; Kou, Y. Toward energy-efficient rescheduling decision mechanisms for flexible job shop with dynamic events and alternative process plans. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2021, 19, 3259–3275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, C.; Chang, F. An adaptive ensemble deep forest based dynamic scheduling strategy for low carbon flexible job shop under recessive disturbance. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Gong, W.; Wang, L.; Lu, C.; Jiang, S. Two-stage knowledge-driven evolutionary algorithm for distributed green flexible job shop scheduling with type-2 fuzzy processing time. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2022, 74, 101139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Gao, K.; Duan, P. Two-level balancing multi-objective algorithm for trapezoidal type-2 fuzzy flexible job shop problems. Inf. Sci. 2024, 678, 121011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Wu, L.; Jia, S.; Peng, T. Dynamic integrated scheduling of production equipment and automated guided vehicles in a flexible job shop based on deep reinforcement learning. Processes 2024, 12, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García Gómez, P.; Vela, C.R.; Gonzalez-Rodriguez, I. Neighbourhood search for energy minimisation in flexible job shops under fuzziness. Nat. Comput. 2023, 22, 685–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Li, J.K.; Gao, K.Z.; Xu, Y. A double-Q network collaborative multi-objective optimization algorithm for precast scheduling with curing constraints. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 89, 101619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Liu, Y. Infinitely repeated game based real-time scheduling for low-carbon flexible job shop considering multi-time periods. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Abdolrazzagh-Nezhad, M. Fuzzy job-shop scheduling problems: A review. Inf. Sci. 2014, 278, 380–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, R.; Sun, X. Bi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem considering energy consumption under stochastic processing times. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Y.; Gao, K.; Xiao, X.; Duan, P. Bi-population balancing multi-objective algorithm for fuzzy flexible job shop with energy and transportation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 21, 4686–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Gong, W.; Lu, C. An enhanced memetic algorithm with hierarchical heuristic neighborhood search for type-2 green fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 130, 107762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Liu, Z.M.; Li, C.; Zheng, Z.X. Improved artificial immune system algorithm for type-2 fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 29, 3234–3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, K.; Bhutta, M.U.; Butt, S.I.; Jaffery, S.H.I.; Khan, M.; Khan, A.Z.; Faraz, Z. A Pareto-optimality based black widow spider algorithm for energy efficient flexible job shop scheduling problem considering new job insertion. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 164, 111937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Gong, W.; Lu, C. Knowledge-driven two-stage memetic algorithm for energy-efficient flexible job shop scheduling with machine breakdowns. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 235, 121149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naimi, R.; Nouiri, M.; Cardin, O. A Q-learning rescheduling approach to the flexible job shop problem combining energy and productivity objectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, E.; Onuet, S. Energy-efficient scheduling for a flexible job shop problem considering rework processes and new job arrival. Int. J. Ind. Eng. Comput. 2024, 15, 871–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Wu, B.; Wang, H.; Tong, H.; Yan, F. A Q-Learning based NSGA-II for dynamic flexible job shop scheduling with limited transportation resources. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 90, 101658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Gong, G.; Peng, N.; Zhang, L.; Huang, D.; Luo, Q.; Li, X. Dynamic distributed flexible job-shop scheduling problem considering operation inspection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 224, 119840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhou, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, D. DQL-assisted competitive evolutionary algorithm for energy-aware robust flexible job shop scheduling under unexpected disruptions. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 91, 101750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, C.; Wang, W. Evolutionary game based real-time scheduling for energy-efficient distributed and flexible job shop. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Qin, C.; Zhang, W.; Xu, Z.; Xu, G.; Gao, Z. Energy-saving scheduling for flexible job shop problem with AGV transportation considering emergencies. Systems 2023, 11, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Lin, Y.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, D.; Li, X.; Yang, D. A two-stage individual feedback NSGA-III for dynamic many-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 1673–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, J. Energy-efficient scheduling for a flexible job shop with machine breakdowns considering machine idle time arrangement and machine speed level selection. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 161, 107677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, J.; Wang, J. Robust scheduling for flexible machining job shop subject to machine breakdowns and new job arrivals considering system reusability and task recurrence. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 203, 117489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.L.; Zhang, B.B.; Li, Y. A multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling model based on fuzzy theory and immune genetic algorithm. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2020, 19, 123–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.L.; Li, J.Q.; Xu, Y. Q-learning based multi-objective immune algorithm for fuzzy flexible job shop scheduling problem considering dynamic disruptions. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 83, 101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Qin, S.; Wang, S.; Zhang, J.; Ding, G. An energy-saving real-time scheduling method based on bi-level multi-agent architecture with bargaining game for flexible job shops. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 269, 126527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sheng, B.; Lu, Q.; Yin, X.; Zhao, F.; Lu, X.; Luo, R.; Fu, G. A Novel Multi-Objective Optimization Algorithm for the Integrated Scheduling of Flexible Job Shops Considering Preventive Maintenance Activities and Transportation Processes. Soft Comput. 2021, 25, 2863–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, M.; Zhang, W.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, K. A multi-objective genetic algorithm based on two-stage reinforcement learning for green flexible shop scheduling problem considering machine speed. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 258, 125189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, S.H.; Trabelsi, W.; Sauvey, C. Multi-Objective Production Rescheduling: A Systematic Literature Review. Mathematics 2024, 12, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham, M.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.H. Real-time scheduling of multi-stage flexible job shop floor. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2011, 49, 3715–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, A.; Khan, S.A.; But, W.H.; Javaid, A.; Shehryar, T. An IoT-enabled real-time dynamic scheduler for flexible job shop scheduling (FJSS) in an industry 4.0-based manufacturing execution system (MES 4.0). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 49653–49666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, M.; Ding, H.; Ling, S.; Huang, G.Q. Graduation-inspired synchronization for industry 4.0 planning, scheduling, and execution. J. Manuf. Syst. 2022, 64, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, M.; Zolfagharinia, H.; Taghipour, S. Real-time production scheduling in the Industry-4.0 context: Addressing uncertainties in job arrivals and machine breakdowns. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 123, 105031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, T.; Zhang, L.; Wu, X. An energy-efficient scheduling approach for flexible job shop problem in an internet of manufacturing things environment. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 62695–62704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Li, M.; Zhong, R.Y.; Huang, G.Q. Multistage self-adaptive decision-making mechanism for prefabricated building modules with IoT-enabled graduation manufacturing system. Autom. Constr. 2023, 148, 104755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tao, Z.; Wang, L.; Du, B.; Guo, J.; Pang, S. Digital twin-based job shop anomaly detection and dynamic scheduling. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.Y.; Park, J. Smart production scheduling with time-dependent and machine-dependent electricity cost by considering distributed energy resources and energy storage. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 3922–3939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Ren, S.; Wang, C.; Ma, S. Edge computing-based real-time scheduling for digital twin flexible job shop with variable time window. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2023, 79, 102435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfund, M.E.; Fowler, J.W. Extending the boundaries between scheduling and dispatching: Hedging and rescheduling techniques. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3294–3307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, M.; Taghipour, S.; Zolfagharinia, H. Real-time integrated production-scheduling and maintenance-planning in a flexible job shop with machine deterioration and condition-based maintenance. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 423–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Xing, L.N.; Chen, Y.W. Robust scheduling for multi-objective flexible job-shop problems with random machine breakdowns. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2013, 141, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Wang, W.; Tian, J. Flexible job shop scheduling with stochastic machine breakdowns by an improved tuna swarm optimization algorithm. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 180–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, S.; Thiruvady, D.; Zhang, M.; Tan, K.C. A genetic programming approach for evolving variable selectors in constraint programming. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2021, 25, 492–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Tang, Q.; Wu, Z.; Wang, F. Mathematical modeling and evolutionary generation of rule sets for energy-efficient flexible job shops. Energy 2017, 138, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhong, J.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, G. A study on PGEP to evolve heuristic rules for FJSSP considering the total cost of energy consumption and weighted tardiness. Comput. Appl. Math. 2019, 38, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Liao, W.; Zhang, L. Hybrid energy-efficient scheduling measures for flexible job-shop problem with variable machining speeds. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 197, 116785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, S.; Wang, S.; Li, A.; Cai, W.; Liu, Y.; Hao, J.; Hu, L. The green flexible job-shop scheduling problem considering cost, carbon emissions, and customer satisfaction under time-of-use electricity pricing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2443. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, L.; Zou, Z.; Liang, X. Solving multi-objective energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling problem by hybrid search genetic algorithm. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 200, 110829. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, S.; Tang, H.; Li, X.; Lei, D.; Wang, X.V. An improved memetic algorithm for multi-objective resource-constrained flexible job shop inverse scheduling problem: An application for machining workshop. J. Manuf. Syst. 2024, 74, 264–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Yang, D.; Zhou, B.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Hu, K. Adaptive population nsga-iii with dual control strategy for flexible job shop scheduling problem with the consideration of energy consumption and weight. Machines 2021, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Yin, S.; Ren, G.; Liu, W. Study on flexible job shop scheduling problem considering energy saving. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2024, 46, 5493–5520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, F.; Zhao, H.; Liu, S.Q.; He, Y.; Tang, B. Enhanced NSGA-II for multi-objective energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling. Sustain. Comput. Inform. Syst. 2023, 39, 100901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaboga, D. An Idea Based on Honey Bee Swarm for Numerical Optimization; Technical Report-tr06; Erciyes University, Engineering Faculty, Computer Engineering Department: Kayseri, Turkey, 2005; pp. 1–10. Available online: https://abc.erciyes.edu.tr/pub/tr06_2005.pdf (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Gu, X. Application research for multiobjective low-carbon flexible job-shop scheduling problem based on hybrid artificial bee colony algorithm. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 135899–135914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Tian, Z.; Liu, W.; Suo, Y.; Chen, K.; Xu, X.; Li, Z. Energy-efficient scheduling of flexible job shops with complex processes: A case study for the aerospace industry complex components in China. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2022, 27, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmeyr, S.A.; Forrest, S. Architecture for an artificial immune system. Evol. Comput. 2000, 8, 443–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Zuo, Y.; Xiang, F.; Tao, F. An improved electromagnetism-like mechanism algorithm for energy-aware many-objective flexible job shop scheduling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 119, 4265–4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, B.; Gao, K.; Ren, Y.; Sang, H. MILP modeling and optimization of multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem with controllable processing times. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 82, 101374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Lu, C.; Zhou, J.; Yin, L.; Wang, K. A knowledge-guided bi-population evolutionary algorithm for energy-efficient scheduling of distributed flexible job shop problem. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 128, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Yu, Y.; Li, R. Distributed energy-efficient flexible manufacturing with assembly and transportation: A knowledge-based bi-hierarchical optimization approach. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 7463–7479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Jiang, X.; Tian, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, W. Knowledge-based lot-splitting optimization method for flexible job shops considering energy consumption. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 21, 4864–4875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Liu, W.; Yang, J. An enhanced multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with reinforcement learning for energy-efficient scheduling in the flexible job shop. Processes 2024, 12, 1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Liu, L.; Zhu, H. A Q-learning-based biology migration algorithm for energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling with speed adjustable machines and transporters. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 90, 101655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Duan, P. A reinforcement learning approach for flexible job shop scheduling problem with crane transportation and setup times. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 35, 5695–5709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Shen, L.; Han, S. Low-Carbon Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rui, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Ling, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, C.; Sun, M. Graph reinforcement learning for flexible job shop scheduling under industrial demand response: A production and energy nexus perspective. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 193, 110325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, N. Multiagent and bargaining-game-based real-time scheduling for internet of things-enabled flexible job shop. IEEE Internet Things J. 2018, 6, 2518–2531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wong, T.N. Flexible job-shop scheduling/rescheduling in dynamic environment: A hybrid MAS/ACO approach. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 3173–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Jing, Y.; Gu, C.; He, S.; Chen, J. End-to-end multi-target flexible job shop scheduling with deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 12, 4420–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Tong, X.; Cai, M.; Shi, Y.; Lan, X. Energy-saving scheduling strategy for variable-speed flexible job-shop problem considering operation-dependent energy consumption. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 256, 124952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Han, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Multi-population coevolutionary algorithm for a green multi-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem with automated guided vehicles and variable processing speed constraints. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2024, 91, 101774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; He, M.; Wu, J.; Chen, H.; Cao, Y. An improved MOEA/D for low-carbon many-objective flexible job shop scheduling problem. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 188, 109926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Wang, W.; Zhu, N.; Xu, T. An inverse reinforcement learning algorithm with population evolution mechanism for the multi-objective flexible job-shop scheduling problem under time-of-use electricity tariffs. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 170, 112764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, K.; Liu, L.; Wu, S. A reinforcement learning based memetic algorithm for energy-efficient distributed two-stage flexible job shop scheduling problem. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Li, J.Q.; Chen, X.L.; Duan, P.Y.; Pan, Q.K. Knowledge-based reinforcement learning and estimation of distribution algorithm for flexible job shop scheduling problem. IEEE Trans. Emerg. Top. Comput. Intell. 2022, 7, 1036–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, J. Towards sustainable production: An adaptive intelligent optimization genetic algorithm for solid wood panel manufacturing. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Du, Y.; Zhuang, C.; Wang, L.; Yu, Y. An iterative greedy algorithm for solving a multiobjective distributed assembly flexible job shop scheduling problem with fuzzy processing time. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 2302–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Shao, W.; Shao, Z.; Pi, D. Graph-based reinforced multi-objective optimization for distributed heterogeneous flexible job shop scheduling problem under nonidentical time-of-use electricity tariffs. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 290, 128428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Fang, M.H.; Qian, B.; Hu, R.; Chen, W. A Hierarchical Collaborative Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning Framework for Distributed Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problems Considering Energy Efficiency and Dynamic Disruption in IIoTs. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 186, 113992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, X.W.; Qian, B.; Jin, H.P.; Hu, R.; Yang, J.B. Multi-Agent Cooperative Multi-Network Group Framework for Energy-Efficient Distributed Fuzzy Flexible Job Shop Scheduling Problem. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 181, 113474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, J. An enhanced memetic algorithm for energy-efficient and low-carbon flexible job shop scheduling problem considering machine restart. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 457–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chai, Z. Energy-saving distributed flexible job-shop scheduling with fuzzy processing time in IIoT: A novel evolutionary multitasking algorithm. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2025, 45, 100829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Zhang, C.; Meng, L.; Zhang, B.; Gao, K.; Sang, H. Deep reinforcement learning for solving efficient and energy-saving flexible job shop scheduling problem with multi-AGV. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 181, 107087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q.; Fu, G.U.; Li, L.; Guo, J. A framework of cloud-edge collaborated digital twin for flexible job shop scheduling with conflict-free routing. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 2024, 86, 102672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key Words | Year | Strength | Begin | End | 2000–2025 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic algorithm | 2002 | 5.16 | 2002 | 2015 | ▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Tabu search | 2003 | 9.37 | 2007 | 2013 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Local search | 2007 | 6.12 | 2010 | 2017 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Flexible job shop scheduling | 2005 | 5.13 | 2010 | 2011 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Power consumption | 2017 | 5.1 | 2017 | 2019 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Consumption | 2017 | 5.23 | 2019 | 2022 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃▂▂▂ |

| Bee colony algorithm | 2016 | 4.81 | 2019 | 2020 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂▂▂ |

| Total weight tardiness | 2019 | 4.75 | 2019 | 2021 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▂▂▂▂ |

| Multi-objective optimization | 2018 | 7.43 | 2021 | 2022 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▂▂▂ |

| Reinforcement learning | 2022 | 6.68 | 2022 | 2025 | ▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▂▃▃▃▃ |

| Source Title | Publications |

|---|---|

| EXPERT SYSTEMS WITH APPLICATIONS | 5 |

| SWARM AND EVOLUTIONARY COMPUTATION | 5 |

| COMPUTERS AND INDUSTRIAL ENGINEERING | 4 |

| APPLIED SOFT COMPUTING | 3 |

| IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON AUTOMATION SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING | 3 |

| JOURNAL OF CLEANER PRODUCTION | 3 |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SIMULATION MODELLING | 2 |

| ROBOTICS AND COMPUTER INTEGRATED MANUFACTURING | 2 |

| INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF PRODUCTION RESEARCH | 2 |

| Symbolic | Symbolic Meaning |

|---|---|

| Total number of jobs | |

| Total number of machines | |

| Index of machine | |

| Number of available machines for the hth operation of job j | |

| Index of job | |

| Total number of operations for job j | |

| Index of process | |

| The hth operation of the job j | |

| Processing of the hth operation of job j on machine i | |

| Processing time of the hth operation of job j on machine i | |

| Start time of the hth operation of job j | |

| Completion time of the hth operation of the jth job | |

| A sufficiently large positive number | |

| If operation is assigned to machine i, then it is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| If precedes processing, then it is 1; otherwise, it is 0 | |

| Delivery date for job j |

| Dynamic Type | Number | References |

|---|---|---|

| Job-related | 19 | [2,9,32,38,39,64,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84] |

| Machine-related | 3 | [27,85,86] |

| Multiple | 21 | [16,28,39,40,46,47,65,68,71,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Article | Shop Floor Category | Dynamic Disruptions | Objectives | Approach (Algorithm) | Energy-Saving Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nguyen et al., 2021 [115] | JSP | None | Makespan, maximum tardiness, total weighted tardiness | CP + GP | None |

| Zhang et al., 2017 [116] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption | Efficient GEP | Machine power on/off |

| Zhang et al., 2019 [117] | FJSP | None | Total cost of energy consumption Total weighted tardiness | Parallel GEP | None |

| Wei et al., 2022 [118] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | NSGA-II | Adjust the machine speed and machine power on/off |

| Jia et al., 2024 [119] | FJSP | None | Cost, carbon emissions, and customer satisfaction | Improved GA | Time-of-use electricity pricing |

| Hao et al., 2025 [120] | FJSP | None | Total machine load and makespan | Hybrid search GA | Reduce machine load |

| Wei et al., 2024 [121] | FJSP | Machine malfunctions and worker shortage | Makespan, worker cost, energy consumption, and deviation index | Improved MA | None |

| Wu et al., 2021 [122] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | Adaptive NSGA-III | None |

| Luan et al., 2023 [124] | FJSP | None | Makespan, total delay time, and total energy consumption | Enhanced NSGA-II | None |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [92] | FJSP | Machine breakdown and rush order insertion | Makespan, energy consumption, and machine workload deviation. | Improved NSGA-II | None |

| Feng et al., 2024 [93] | FJSP | Machine fault and rush order insertion | Makespan, delay time, total equipment load, and energy consumption | Two-stage individual feedback NSGA-III | None |

| Duan and Wang., 2021 [94] | FJSP | Machine breakdown | Total energy consumption and makespan | NSGA-II | Scheduling machine idle time and adjust the machine speed |

| Nouiri et al., 2020 [28] | FJSP | Machine breakdowns, new job arrivals, and fuzzy processing time | Total energy consumption and makespan | PSO | None |

| Duan and Wang., 2022 [95] | FJSP | Machine breakdowns and new job arrivals | Total energy consumption and makespan | PSO + AOA | None |

| Gu, 2021 [126] | FJSP | None | Makespan, total workload of machines, and total carbon emissions | Hybrid ABC | None |

| Jiang et al., 2022 [127] | FJSP | None | Energy consumption, makespan, and processing cost | Improved crossover ABC | None |

| Tian et al., 2023 [32] | FJSP | Rush order insertion | Energy consumption, makespan, and processing cost | Bi-population differential ABC | None |

| Hu et al., 2024 [33] | FJSP | None | Flow time and Energy consumption | Matheuristic and Learning-oriented ABC | None |

| Shi et al., 2020 [96] | FJSP | Machine breakdown and fuzzy delivery time | Energy consumption, makespan, and consumer dissatisfaction | Immune GA | None |

| Li et al., 2020 [83] | FJSP | Fuzzy processing time | Total energy consumption and makespan | Improved AIA | None |

| Chen et al., 2023 [97] | FJSP | Fuzzy processing time, new job arrival and machine breakdown | Tota energy consumption, makespan, and average agreement index | Q-learning + AIA | Adjust the machine speed |

| Qu et al., 2022 [129] | FJSP | None | Tota energy consumption, makespan, processing cost, and carbon emissions | Improved EMA | None |

| Meng et al., 2023 [130] | FJSP | Fuzzy processing time | Total energy consumption and makespan | Hybrid shuffled FLA | Adjust the machine speed, machine power on/off and machine delayed startup |

| Zhang et al., 2023 [35] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | Improved GWO | None |

| Akram et al., 2024 [84] | FJSP | New job insertion | Total energy consumption, makespan, and schedule instability | BWSA | None |

| Luo et al.,2024 [85] | FJSP | Machine breakdown | Total energy consumption and makespan | Knowledge-driven two-stage MA | Machine power on/fff and machine delayed startup |

| Yu et al., 2024 [131] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | KBEA | Adjust the machine speed |

| Pan et al., 2024 [132] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | KBOA | None |

| Tian et al., 2023 [133] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | Knowledge-based method | None |

| Li et al., 2023 [2] | FJSP | Fuzzy processing time | Total energy consumption and makespan | Learning-based reference vector MA | Rebuild the machine selection vector |

| Zhuang et al., [100] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption, makespan, and tool wear | GA based on two-stage RL | Machine speed and delay machine startup |

| Shi et al., 2024 [134] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | MOEA/D + RL | None |

| Jiang et al., 2024 [135] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption | Q-learning + BMA | Adjust the speed of the machine and transport vehicle |

| Naimi et al., 2021 [86] | FJSP | Machine breakdown | Total energy consumption and makespan | Q-learning rescheduling approach + GA | None |

| Tang et al., 2024 [137] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | DRL + GNN | None |

| Rui et al., 2024 [138] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption, makespan, total energy cost, and peak demand | GRL | None |

| Wang et al., 2024 [141] | FJSP | None | Total energy consumption and makespan | PPO + GNN | None |

| Hu et al., 2025 [98] | FJSP | Machine breakdowns and new job arrivals | Makespan, idle rate, and Total energy consumption | Bi-level multi-agent architecture with bargaining game | None |

| Category | Advantages | Disadvantages | Applicability Scenarios |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exact method | A globally optimal solution can be found and the quality of the solution is theoretically guaranteed. | High computational complexity (NP-hard), difficult to handle large-scale problems; solution time grows exponentially with problem size. | Suitable for scheduling scenarios with a small scale and stable environment. |

| Heuristic | Relatively simple; transparent decision-making process and easy for researchers to understand the reasons for ranking; high robustness. | The optimal solution cannot be guaranteed and is prone to falling into local optimality; the quality of the solution depends on the rule design. | Suitable for scheduling scenarios where a widely applicable scheduling rule needs to be found in different workshops, with diverse orders and inconsistent disturbance factors. |

| Metaheuristic | Strong global search capability, able to jump out of local optima; adaptable to complex constraints. | Limited generalization ability; easy to achieve multiple objectives; trapped in local optima; lack of adaptive parameter adjustment and predictive scheduling capability. | Suitable for scheduling scenarios under multi-objective constraints at medium to large scales. |

| AI methods | Capable of dealing with dynamic and uncertain environments; learning and adaptive; can be used for forecasting and assisted decision-making. | The learning process may require large amounts of data and computational resources; some methods (e.g., neural networks) lack interpretability; and model building and training are complex. | Suitable for medium-to-large-scale intelligent scheduling scenarios that require real-time response to high-frequency disturbances. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sitahong, A.; Wang, G.; Yuan, Y.; Wubuli, A.; Mo, P.; Chen, Y. Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Dynamic Flexible Job Shops: A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411009

Sitahong A, Wang G, Yuan Y, Wubuli A, Mo P, Chen Y. Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Dynamic Flexible Job Shops: A Review. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411009

Chicago/Turabian StyleSitahong, Adilanmu, Gang Wang, Yiping Yuan, Areziguli Wubuli, Peiyin Mo, and Yulong Chen. 2025. "Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Dynamic Flexible Job Shops: A Review" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411009

APA StyleSitahong, A., Wang, G., Yuan, Y., Wubuli, A., Mo, P., & Chen, Y. (2025). Energy-Efficient Scheduling in Dynamic Flexible Job Shops: A Review. Sustainability, 17(24), 11009. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411009