Non-Linear Dynamics: ESG Investment and Financial Performance Heterogeneity in the Tourism Industry

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background of ESG—A Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Overview of ESG Companies in Tourism of Taiwan

2.2. Literature Review and Hypothesis

3. Data Collection and Methodology

3.1. Data

3.2. Methodology

4. Empirical Results

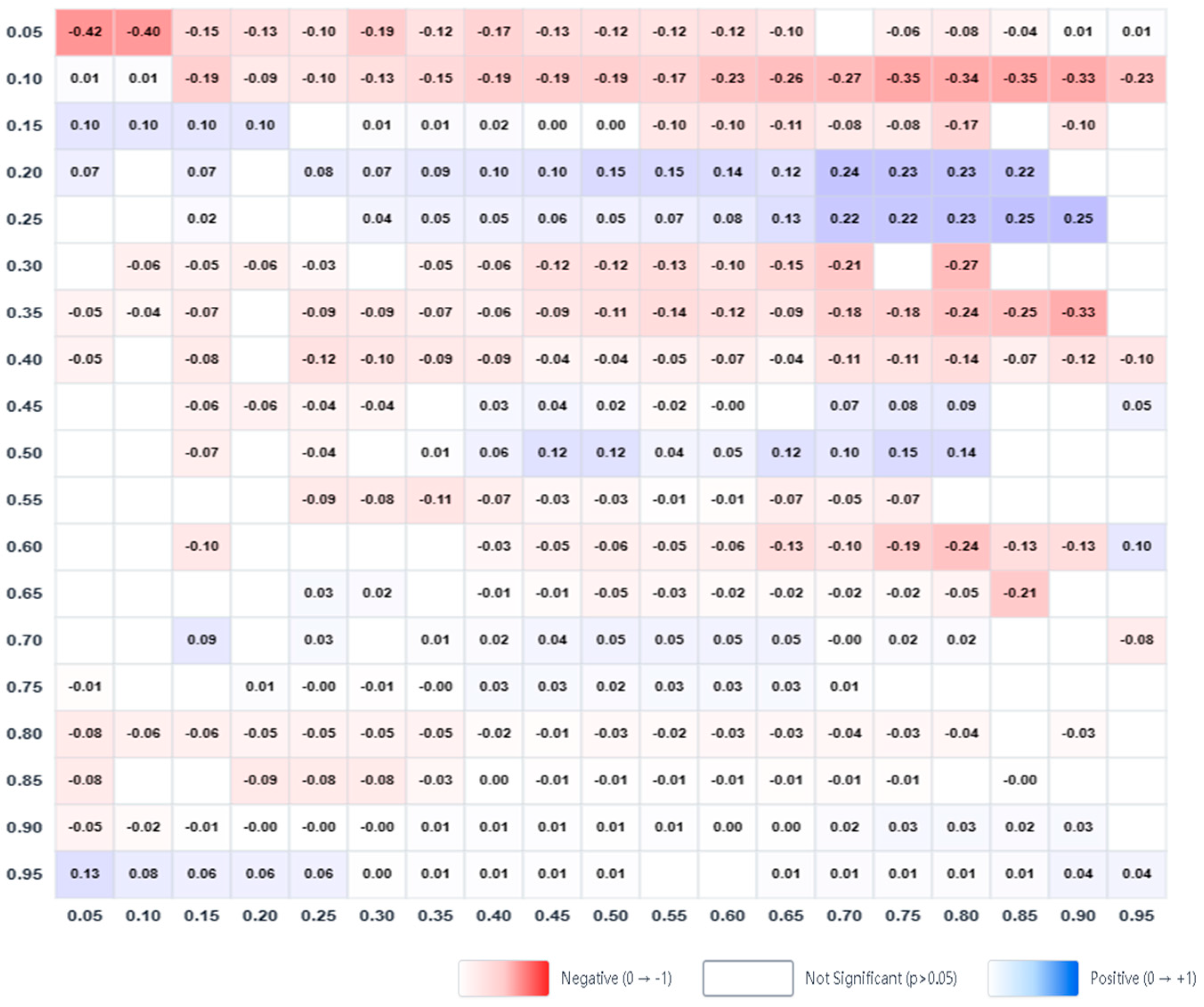

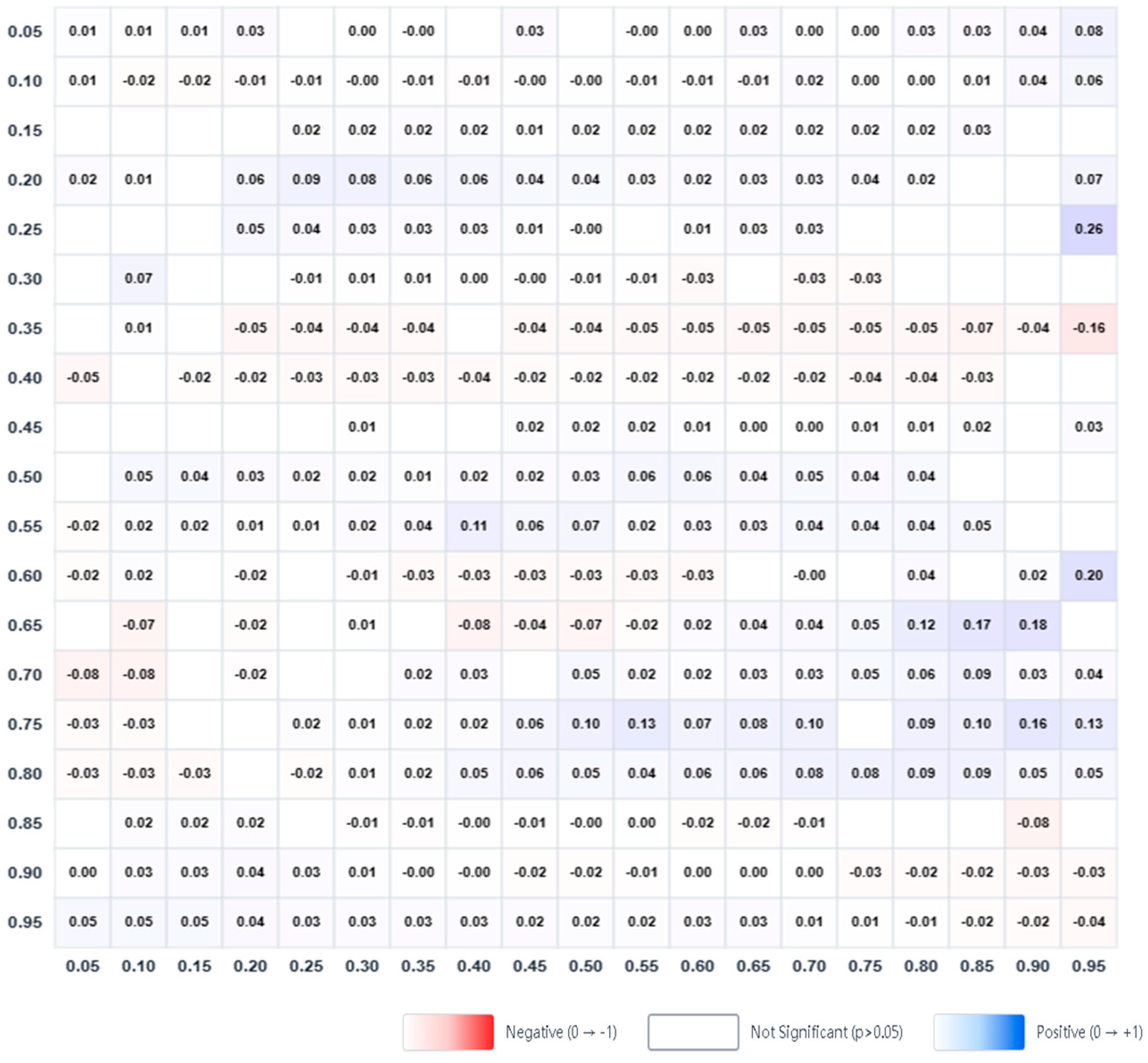

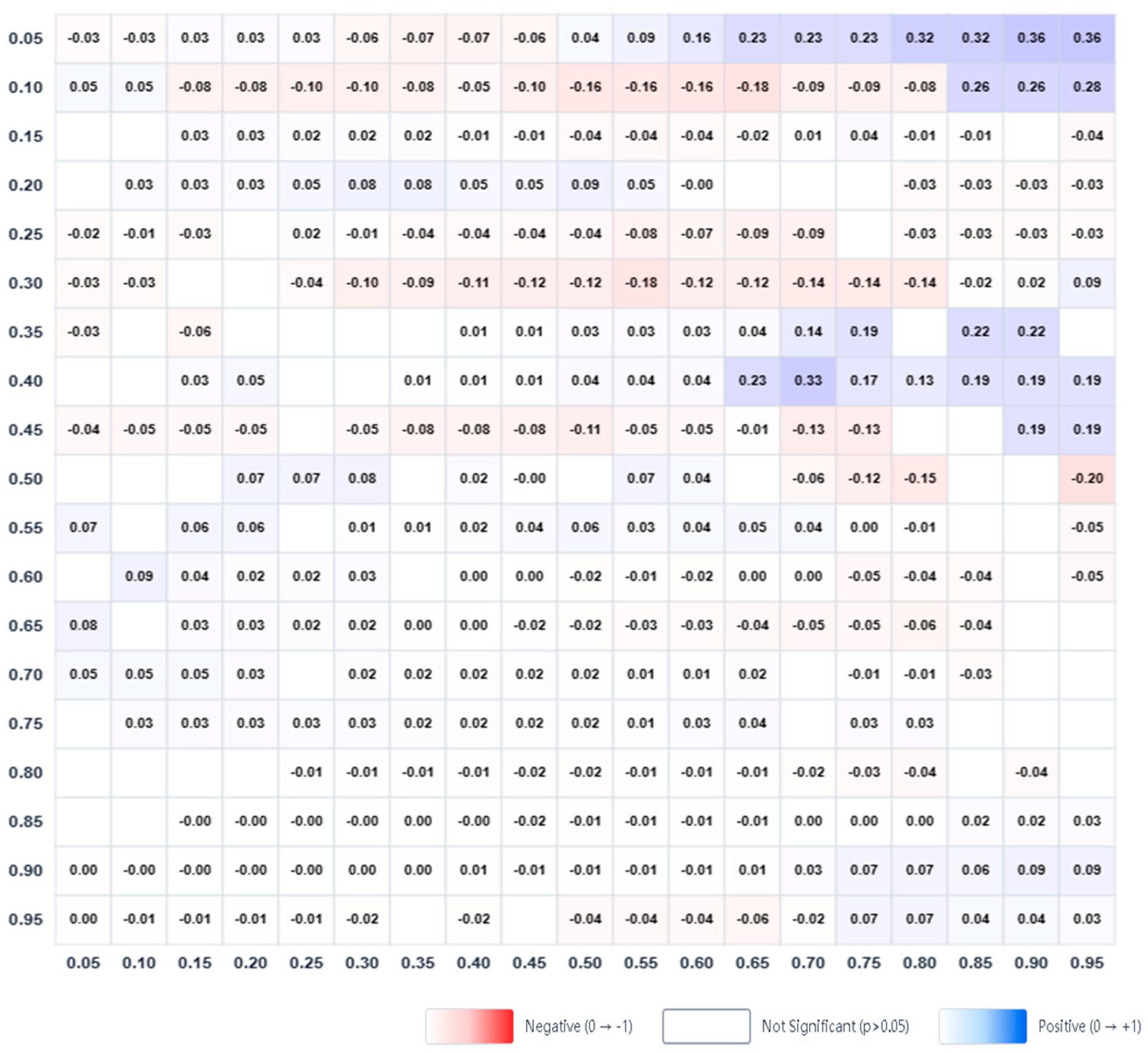

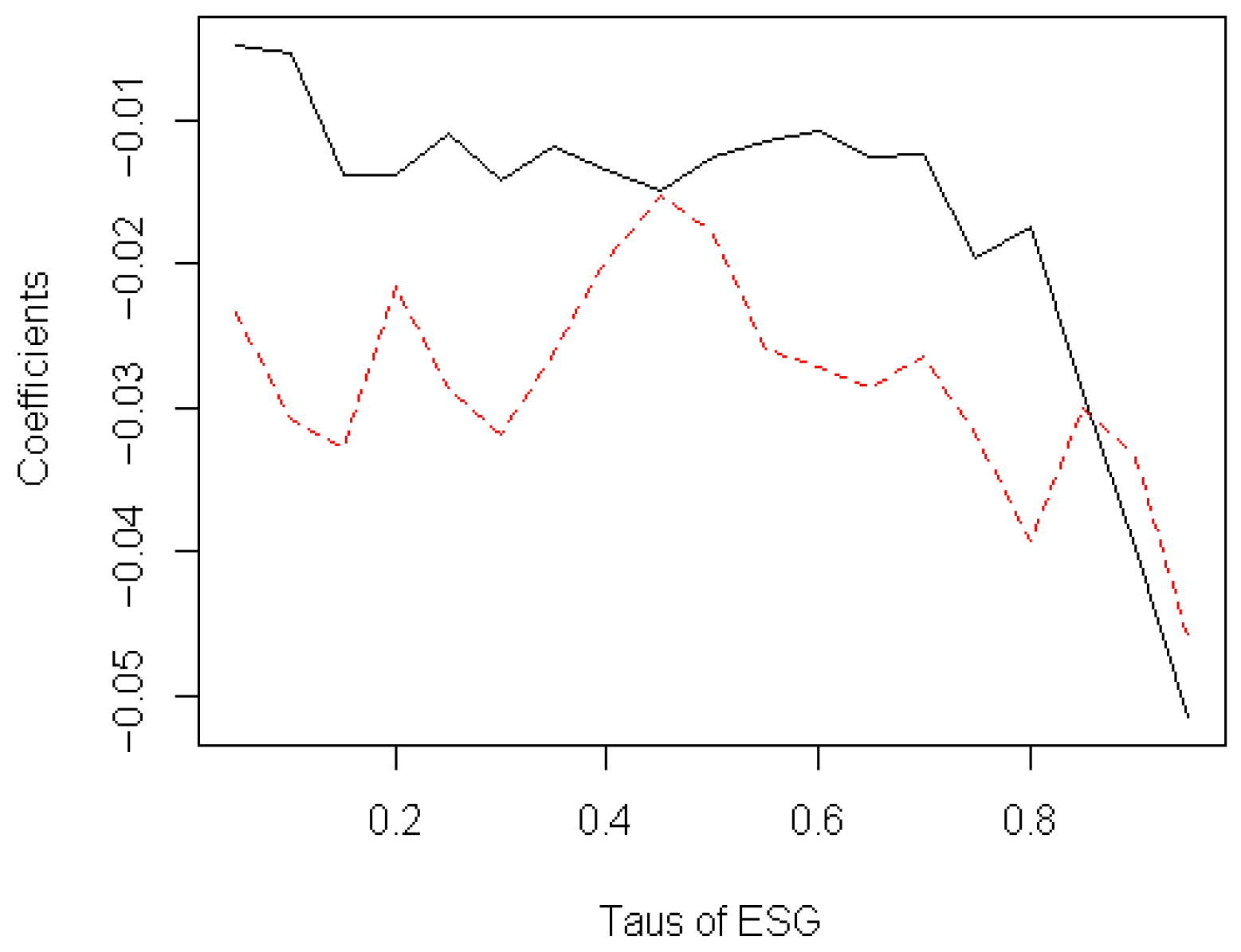

4.1. The Tourism-Related Food Service Sector

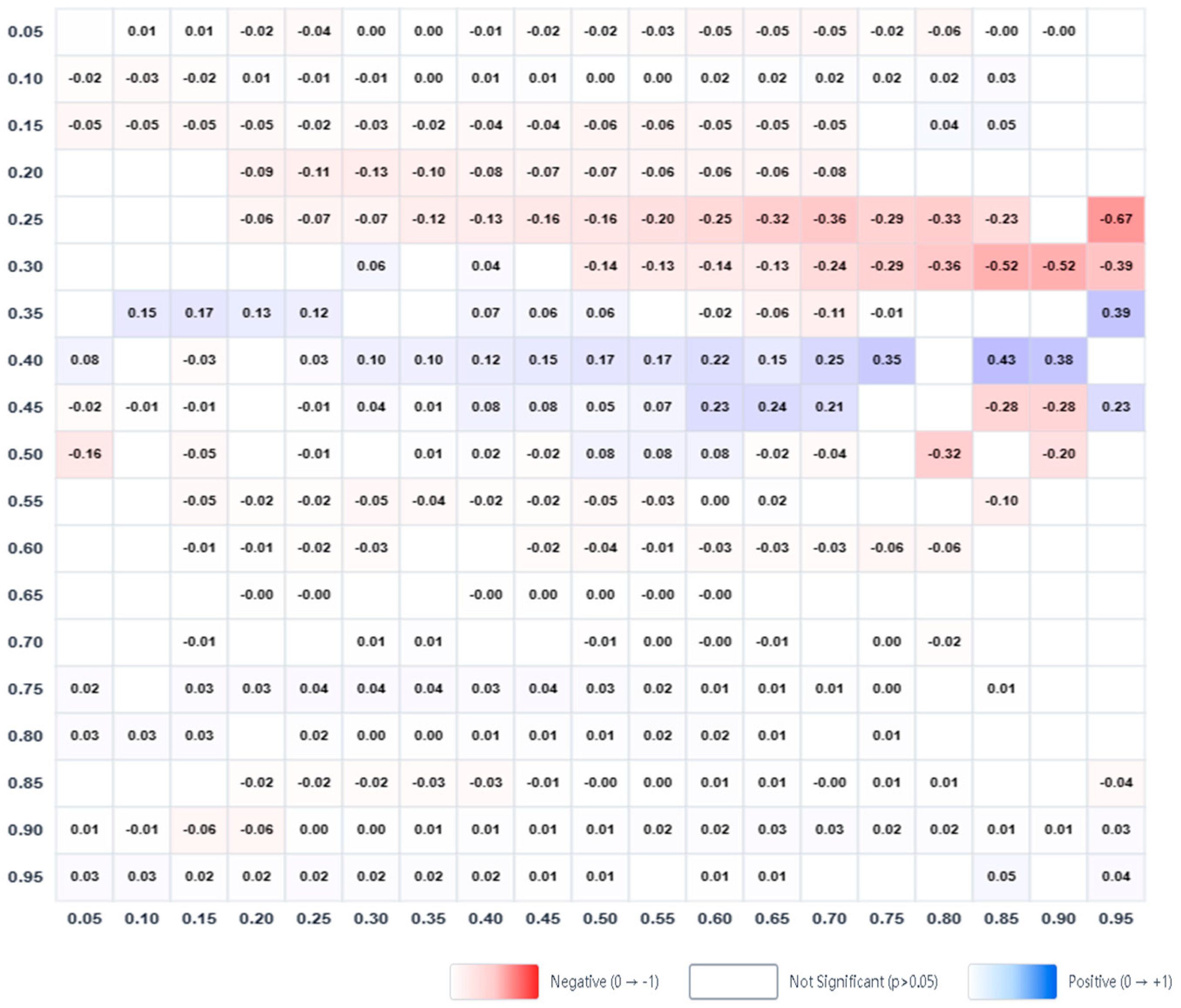

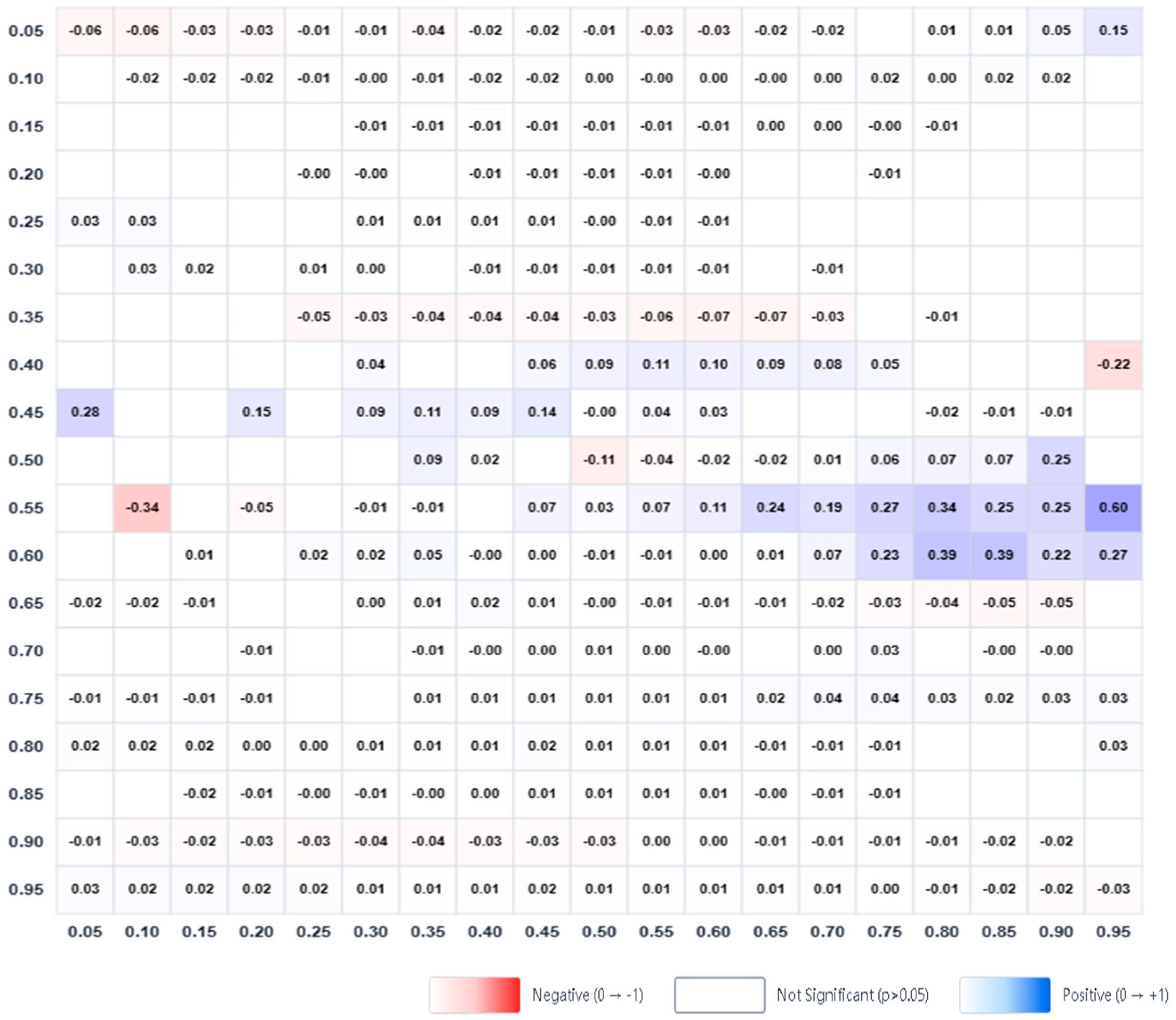

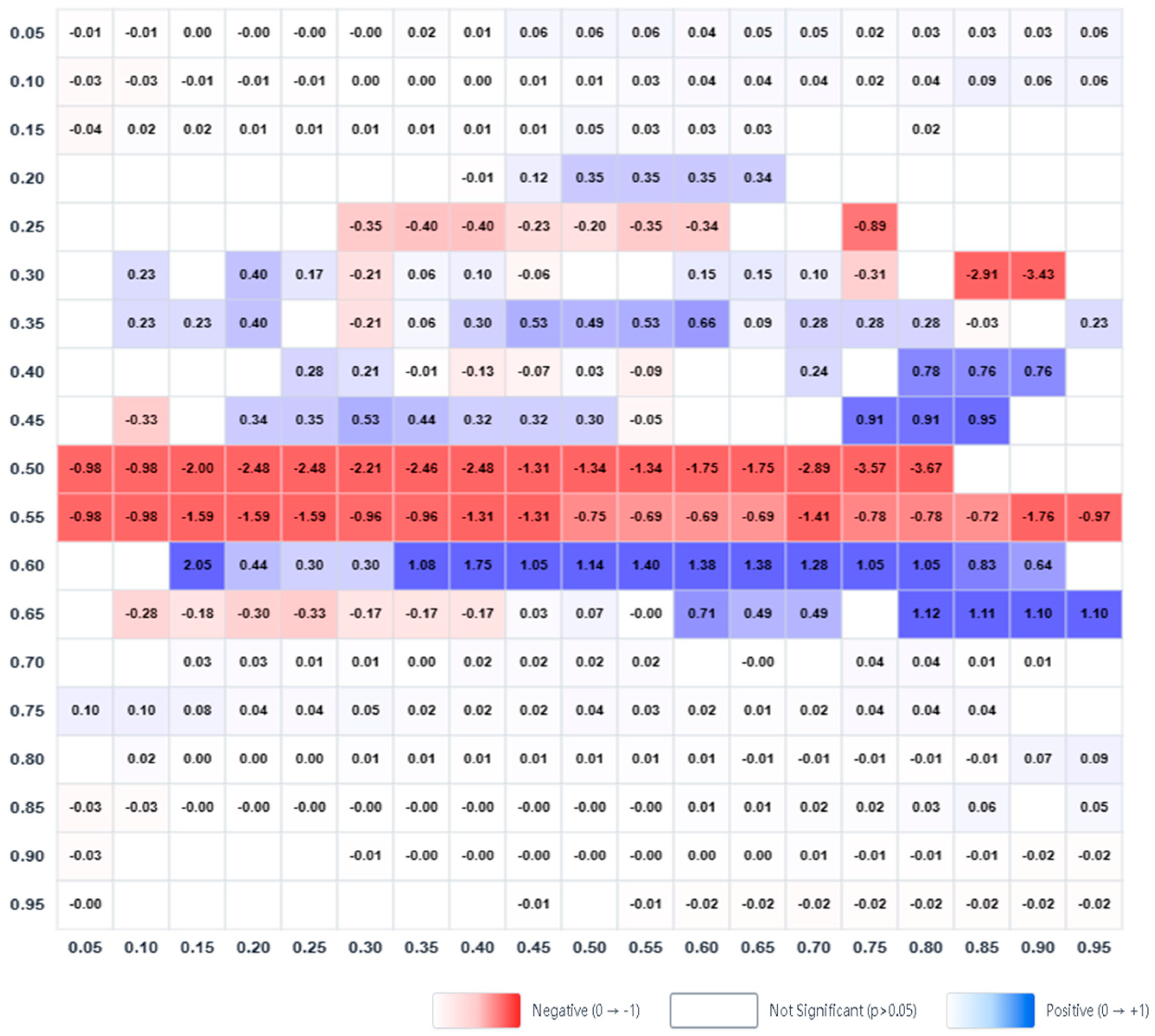

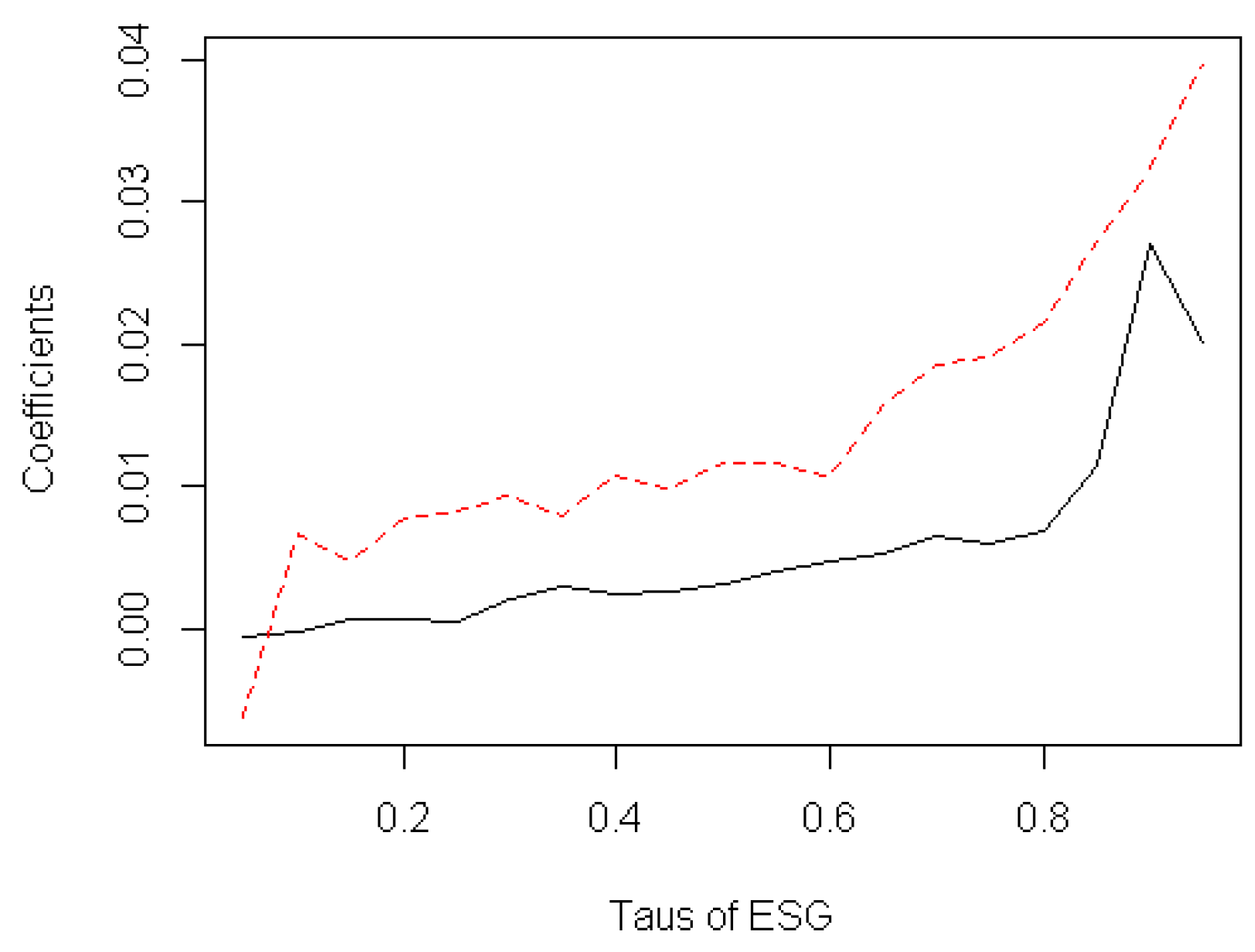

4.2. The Tourism-Related Hotel Service Sector

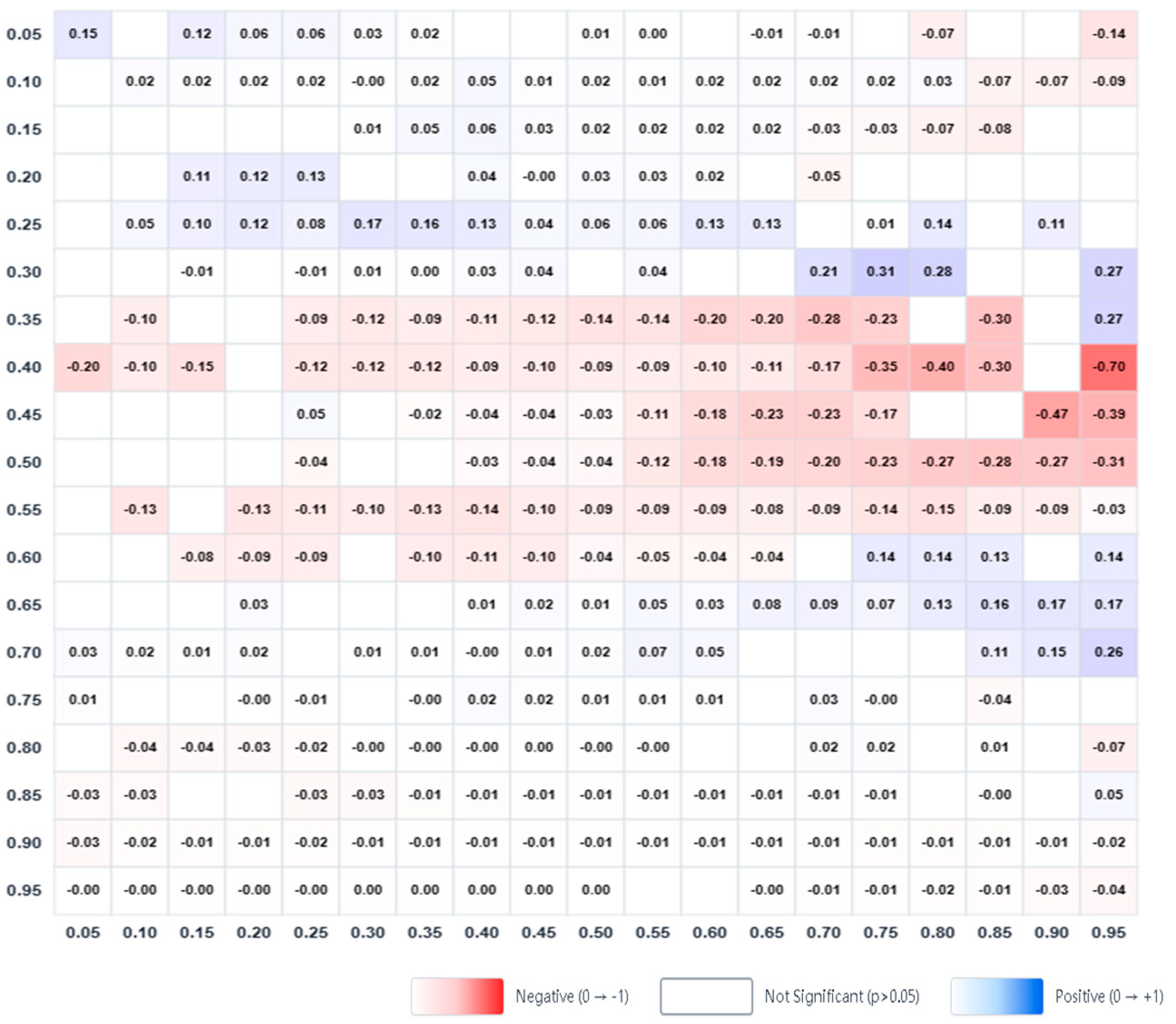

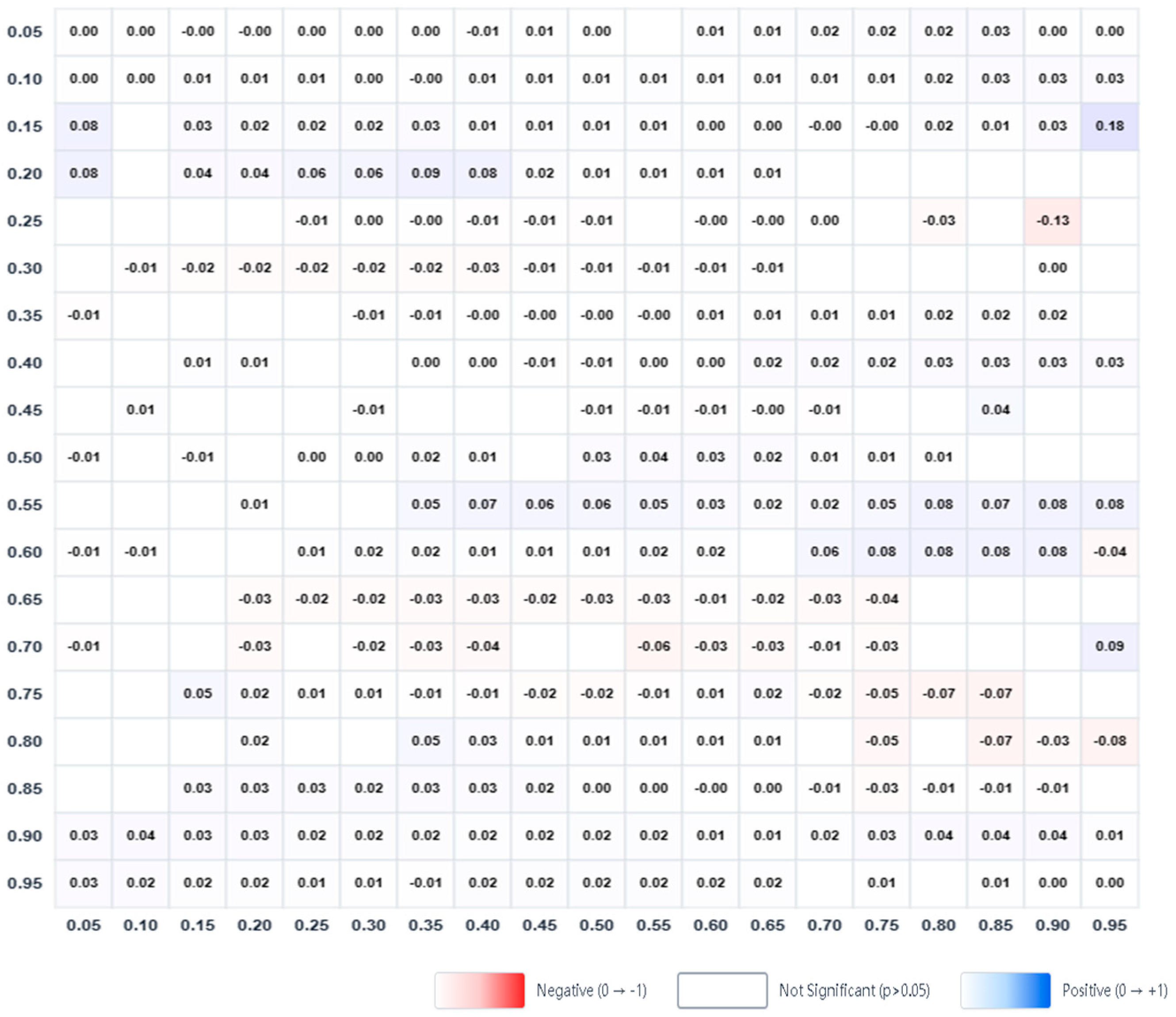

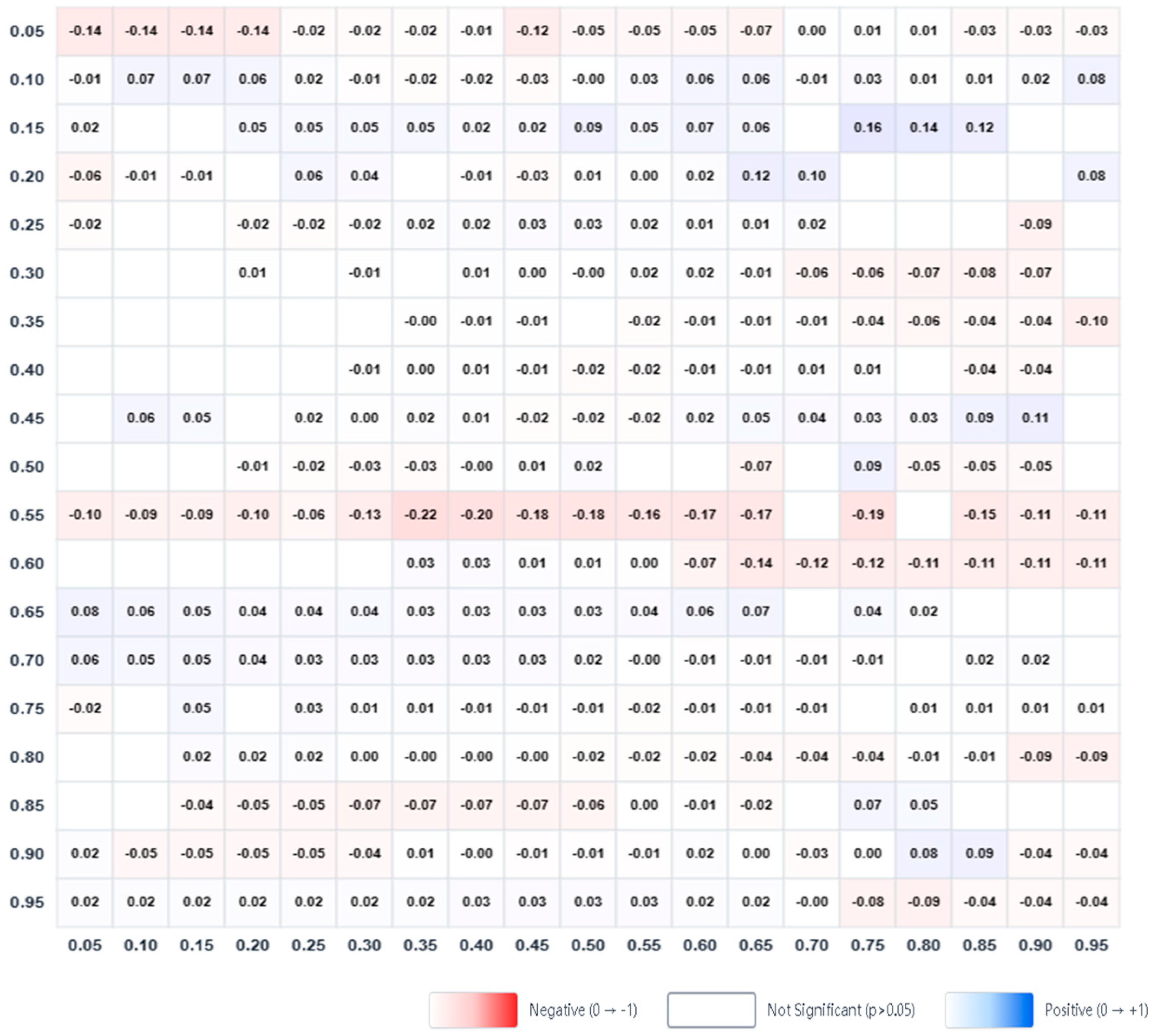

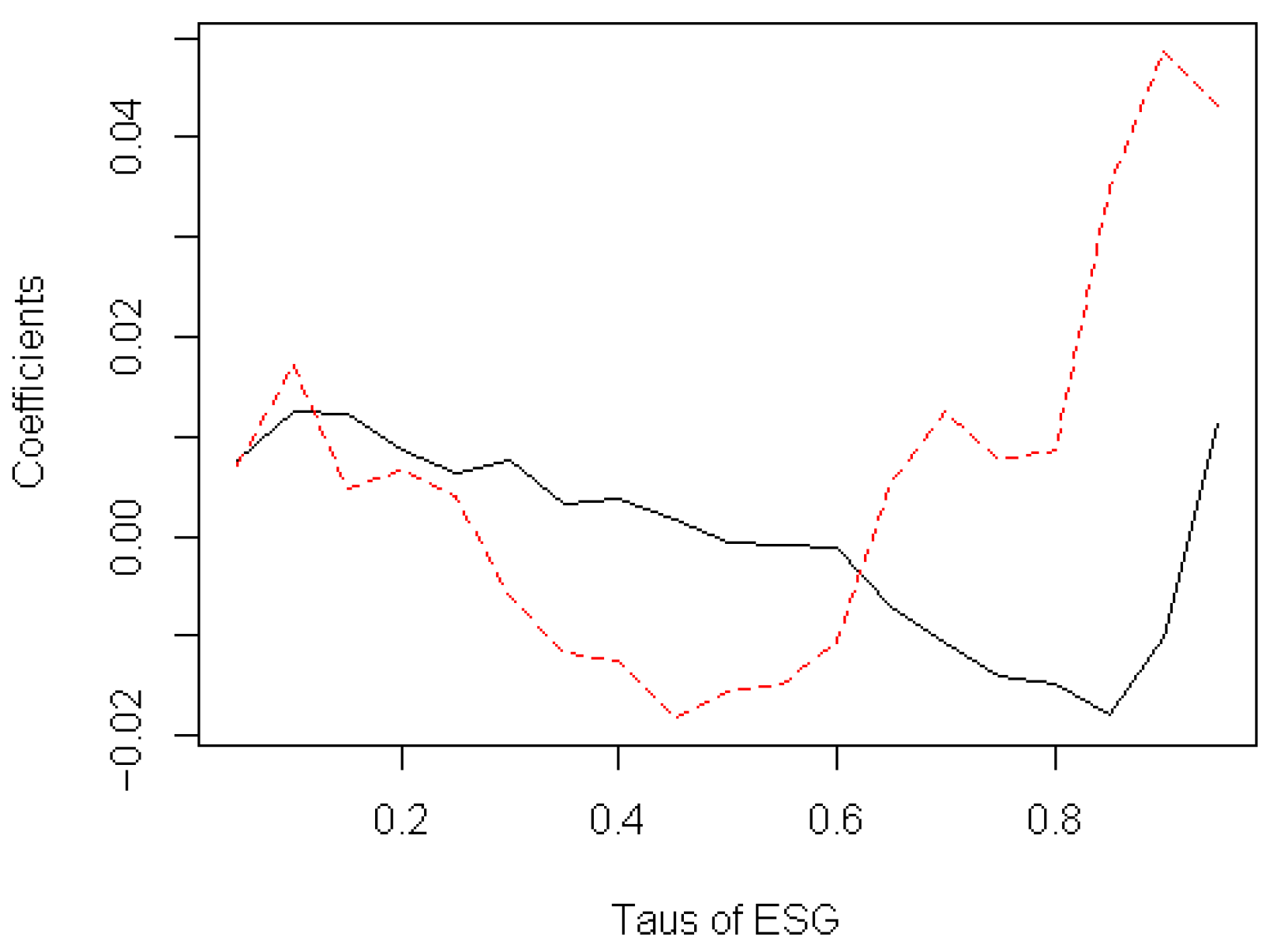

4.3. The Tourism-Related Service Sector

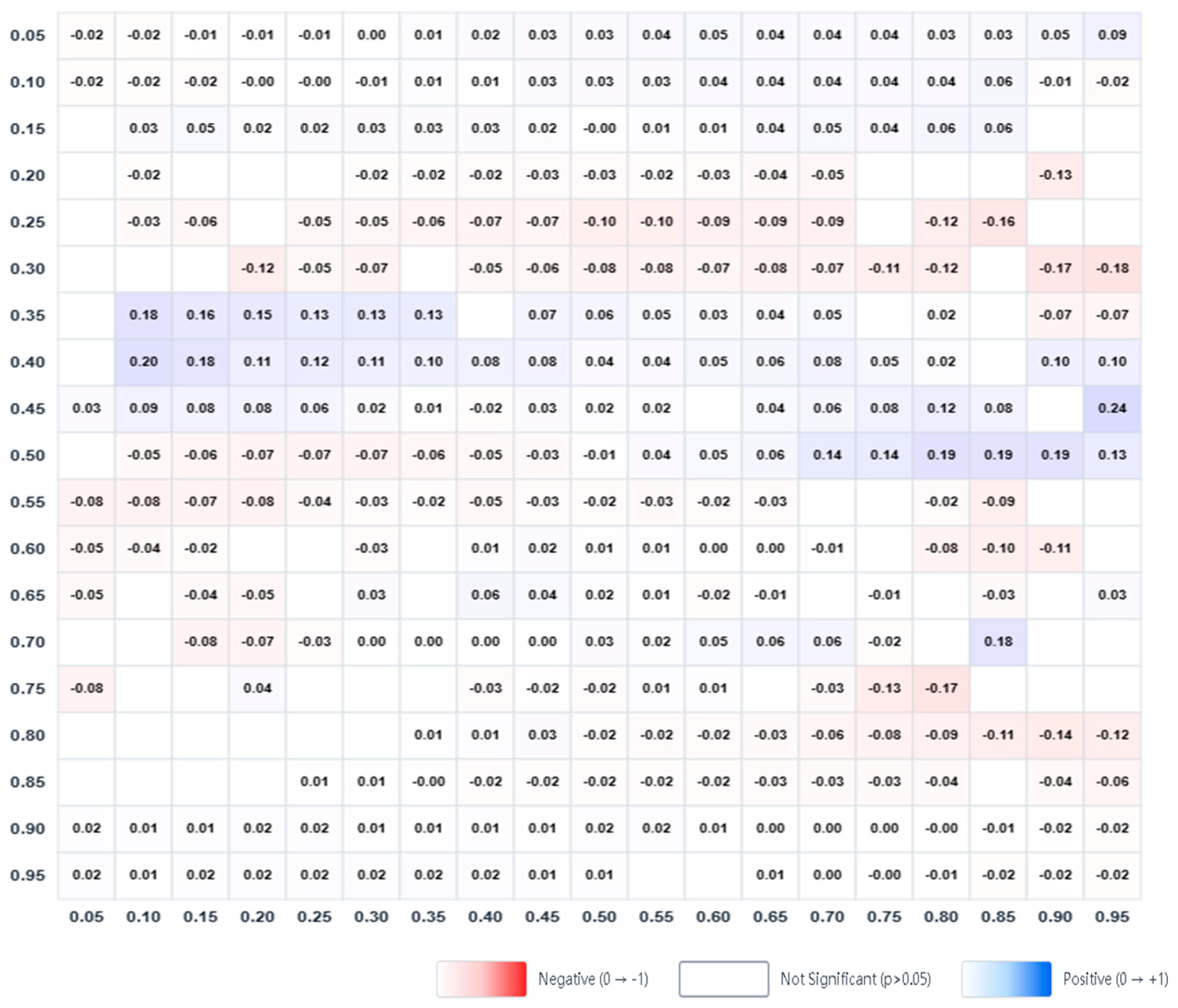

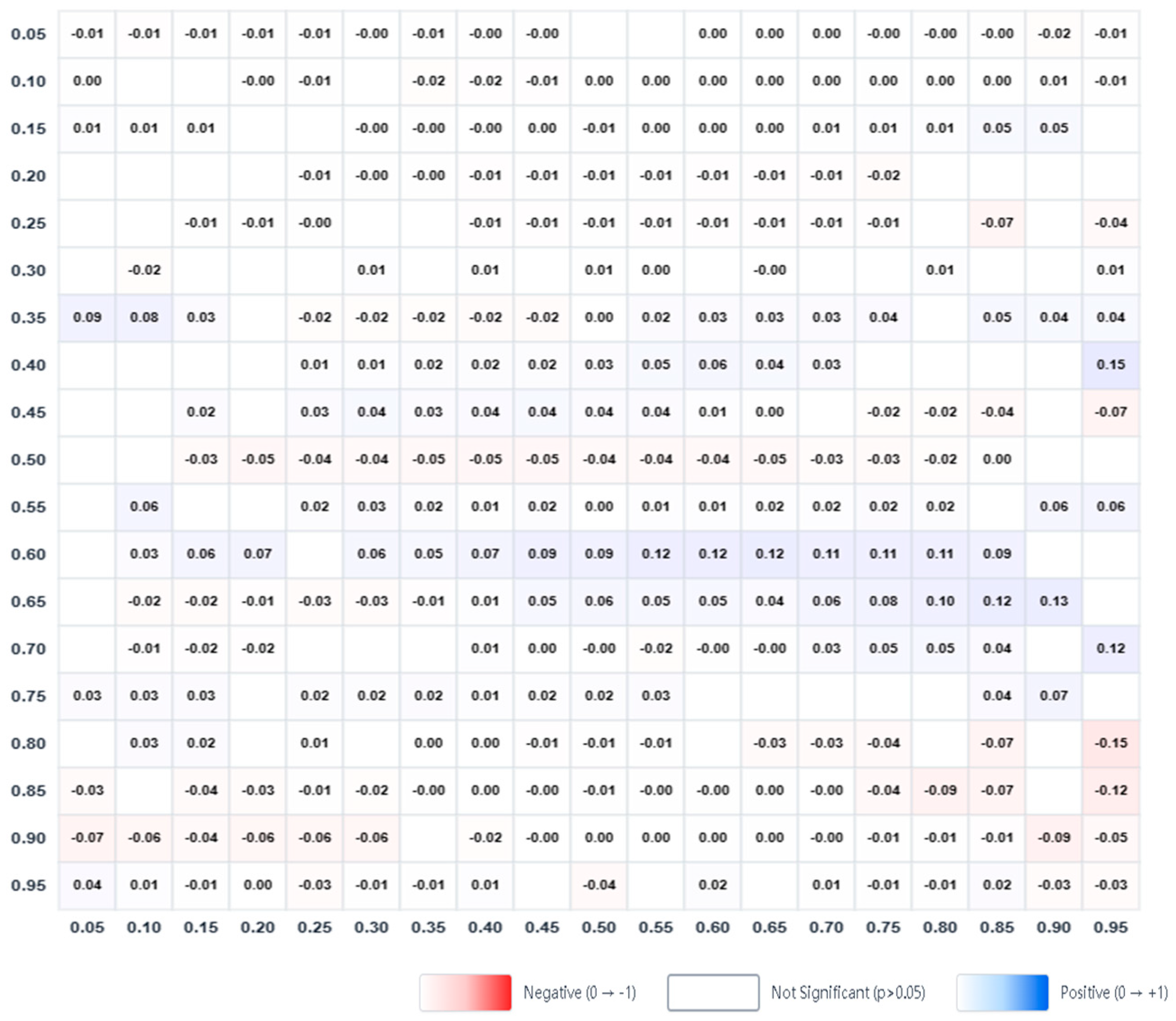

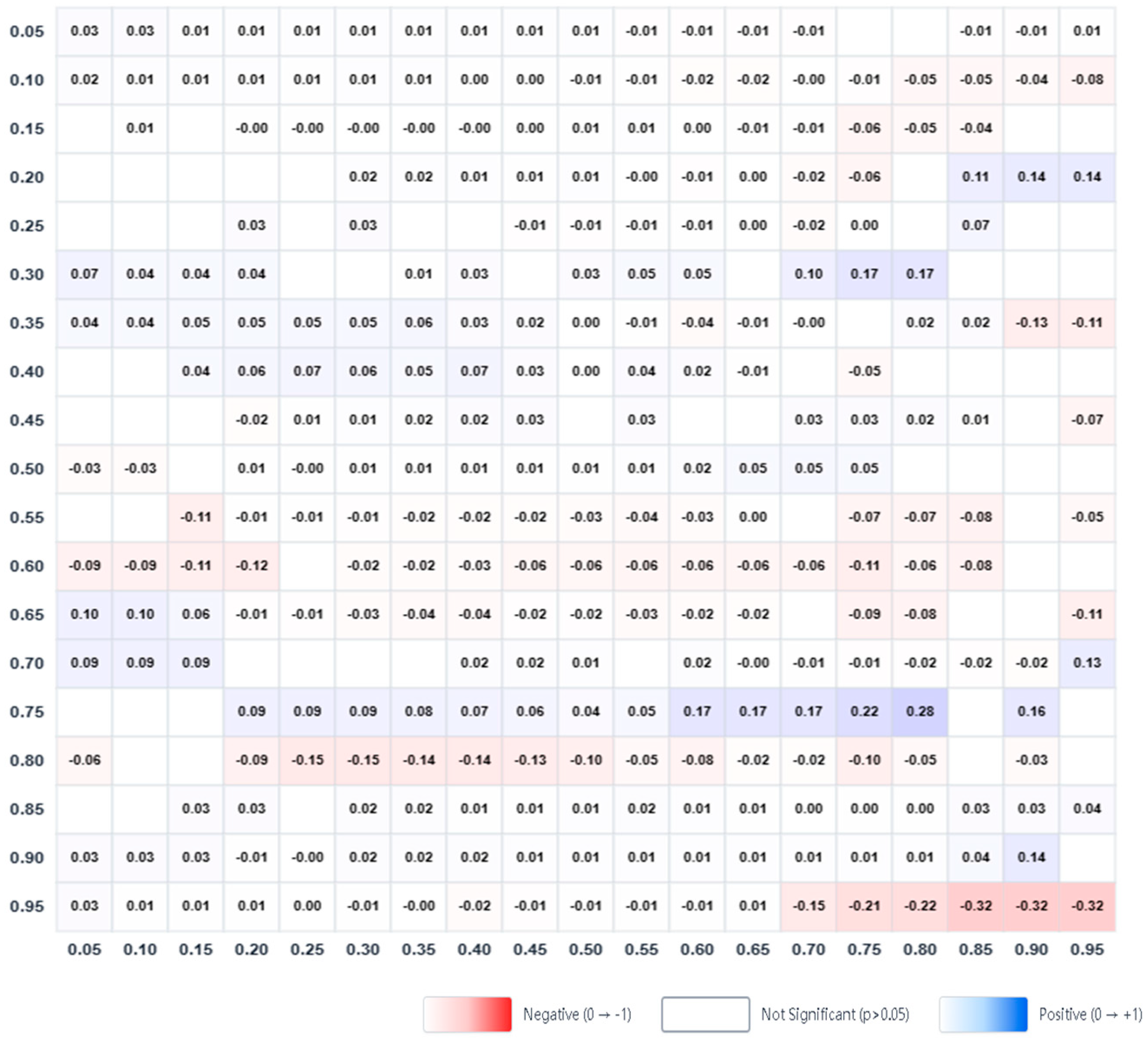

4.4. Comparing QQ and Traditional Quantile Regression

5. Conclusions, Discussion, and Limitations

5.1. Conclusions

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Global Sustainable Investment Alliance. Global Sustainable Investment Review 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.gsi-alliance.org/members-resources/gsir2022/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Soni, M.; Dawar, S.; Soni, A. Probing consumer awareness & barriers towards consumer social responsibility: A novel sustainable development approach. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Plan. 2021, 16, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenzen, M.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Faturay, F.; Ting, Y.-P.; Geschke, A.; Malik, A. The carbon footprint of global tourism. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 522–528. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Ji, J.; Wu, M. Tourism Carbon Emissions: A Systematic Review of Research Based on Bibliometric Methods. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2023, 26, 2266861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, K.-J. ESG for the hospitality and tourism research: Essential demanded research area for all. Tour. Manag. 2024, 105, 104954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legendre, T.S.; Ding, A.; Back, K.-J. A bibliometric analysis of the hospitality and tourism environmental, social, and governance (ESG) literature. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2024, 58, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Y.; Lee, S. Effects of different dimensions of corporate social responsibility on corporate financial performance in tourism-related industries. Tour. Manag. 2011, 32, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.H.; Lee, S.; Huh, C. Impacts of positive and negative corporate social responsibility activities on company performance in the hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2010, 29, 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kholijah, S. Analysis of Economic and Environmental Benefits of Green Business Practices in the Hospitality and Tourism Sector. Involv. Int. J. Bus. 2024, 1, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M. A Study of the Relationship Between ESG Performance and Firm Valuation. Adv. Econ. Manag. Political Sci. 2024, 74, 259–267. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, I.; Alcaraz, J.M.; Susaeta, L.; Suarez, E.; Pin, J. Managing sustainability for competitive advantage: Evidence from the hospitality industry. SSRN Electron. J. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314557628_Managing_Sustainability_for_Competitive_Advantage_Evidence_from_the_Hospitality_Industry (accessed on 22 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Da Hyun, S.H.; Song, H.J.; Lee, S.; Kang, K.H. The moderating role of national economic development on the relationship between ESG and firm performance in the global hospitality industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 120, 103788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E.; Aguilera-Caracuel, J. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. J. Bus. Ethics 2021, 168, 315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Semenova, N.; Hassel, L.G. Financial outcomes of environmental risk and opportunity for US companies. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. ESG Performance, Heterogeneous Creditors, and Bond Financing Costs: Firm-Level Evidence. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 66, 105527. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.-H. Developing ESG evaluation guidelines for the tourism sector: With a focus on the hotel industry. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, Y. Corporate social responsibility and shareholder value of restaurant firms. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 40, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Seo, K.; Sharma, A. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the airline industry: The moderating role of oil prices. Tour. Manag. 2013, 38, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodoulidis, B.; Diaz, D.; Crotto, F.; Rancati, E. Exploring corporate social responsibility and financial performance through stakeholder theory in the tourism industries. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youn, H.; Hua, N.; Lee, S. Does size matter? Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the restaurant industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2015, 51, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attia, E.F.; Tobar, R.; Fouad, H.F.; Ezz Eldeen, H.H.; Chafai, A.; Khémiri, W. The Nonlinear Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Hospitality and Tourism Corporate Financial Performance: Does Governance Matter? Sustainability 2023, 15, 15931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khoury, R.; Nasrallah, N.; Alareeni, B. ESG and financial performance of banks in the MENAT region: Concavity–convexity patterns. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2023, 13, 406–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nollet, J.; Filis, G.; Mitrokostas, E. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: A non-linear and disaggregated approach. Econ. Model. 2016, 52, 400–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Lakkanawanit, P.; Suttipun, M.; Huang, S.-Z. ESG Performance and Enterprise Value in Chinese Tourism Companies: The Chained Mediating Roles of Media Attention and Green Innovation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, P.; Mishra, S.; Bouri, E. Does asset-based uncertainty drive asymmetric return connectedness across regional ESG markets? Glob. Financ. J. 2024, 61, 100972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Habib, A.M.; Mourad, N. The Influence of Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Practices on US Firms’ Performance: Evidence from the Coronavirus Crisis. J. Knowl. Econ. 2024, 15, 2549–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D.L.; Carter, S.M. An examination of differences between organizational legitimacy and organizational reputation. J. Manag. Stud. 2005, 42, 329–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fombrun, C.; Shanley, M. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Acad. Manag. J. 1990, 33, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Investig. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alareeni, B.A.; Hamdan, A. ESG impact on performance of US S&P 500-listed firms. Corp. Gov. 2020, 20, 1409–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouadi, A.; Marsat, S. Do ESG Controversies Matter for Firm Value? Evidence from International Data. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 151, 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogi, M.; Lagasio, V. Environmental, social, and governance and company profitability: Are financial intermediaries different? Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 576–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, G.; Lee, L.-E.; Melas, D.; Nagy, Z.; Nishikawa, L. Foundations of ESG Investing: How ESG Affects Equity Valuation, Risk, and Performance. JPM 2019, 45, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.; Li, S.; Wu, H.; Song, X. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The roles of government intervention and market competition. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Env. 2020, 27, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, A.; Adeleye, B.N.; Adusei, M. Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Evidence from U.S tech firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 292, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, M.A.; Kirkerud, S.; Theresa, K.; Ahsan, T. The impact of sustainability (environmental, social, and governance) disclosure and board diversity on firm value: The moderating role of industry sensitivity. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 1199–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. J. Glob. Responsib. 2017, 8, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Exploring the Multi-Dimensional Effects of ESG on Corporate Valuation: Insights into Investor Expectations, Risk Mitigation, and Long-Term Value Creation. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2024, 103, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsalam, O.; Chantziaras, A.; Grougiou, V.; Leventis, S.; Tsileponis, N. Sustainability Performance and Corporate Risk: Evidence From the Tourism Industry. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahmid, T.; Hoque, M.N.; Said, J.; Saona, P.; Azad, M.D.A.K. Does ESG initiatives yield greater firm value and performance? New evidence from European firms. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2144098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.; Lee, J.H.; Byun, R. Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdi, Y.; Li, X.; Càmara-Turull, X. Exploring the impact of sustainability (ESG) disclosure on firm value and financial performance (FP) in airline industry: The moderating role of size and age. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 5052–5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Tseng, C.-J. Relationship between ESG strategies and financial performance of hotel industry in China: An empirical study. Nurture 2023, 17, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, J.-W.; Chung, S. The Effects of Corporate Social Responsibility on Corporate Reputation: The Case of Incheon International Airport. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsali, C.; Skordoulis, M.; Papagrigoriou, A.; Kalantonis, P. ESG Scores as Indicators of Green Business Strategies and Their Impact on Financial Performance in Tourism Services: Evidence from Worldwide Listed Firms. Adm. Sci. 2025, 15, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiuzzaman, S.; Ibrahim, S.A.; Kawi, F. Environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure and firm performance: Does national culture matter? Meditari Account. Res. 2023, 31, 1239–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, S.; Cohen, M.A. Does the market value environmental performance? Rev. Econ. Stat. 2001, 83, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herremans, I.M.; Akathaporn, P.; McInnes, M. An investigation of corporate social responsibility reputation and economic performance. Account. Organ. Soc. 1993, 18, 587–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Zhu, Y.; Li, R.; Liu, Z.Y.R. ESG Greenwashing and Retail Investor Criticisms. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 79, 103034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarafat, H.; Liebhardt, S.; Eratalay, M.H. Do ESG ratings reduce the asymmetry behavior in volatility? J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Qin, Z. Asymmetric volatility spillovers among new energy, ESG, green bond and carbon markets. Energy 2024, 292, 130504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.; Zhou, H. Oil prices, US stock return, and the dependence between their quantiles. J. Bank. Financ. 2015, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Corporate Value | Total Number | Number of Disclosed | Disclosure Ratio |

| Over 100 billion | 73 | 70 | 96% |

| Over 10 billion to 100 billion | 392 | 274 | 70% |

| Over 5 billion to 10 billion | 274 | 111 | 41% |

| Over 1 billion to 5 billion | 724 | 132 | 18% |

| Less than 1 billion | 231 | 19 | 8% |

| Variable | Sector | Mean | Std Dev | Min | Median | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESG | Food | 47.36 | 7.80 | 28.72 | 47.04 | 64.71 |

| Hotel | 54.67 | 8.74 | 37.92 | 54.66 | 81.60 | |

| Service | 53.29 | 8.09 | 32.91 | 52.68 | 70.28 | |

| E (Environmental) | Food | 47.14 | 9.22 | 25.01 | 45.41 | 76.48 |

| Hotel | 52.96 | 11.74 | 32.09 | 51.66 | 90.42 | |

| Service | 52.45 | 7.66 | 29.87 | 51.51 | 89.28 | |

| S (Social) | Food | 43.68 | 9.55 | 26.02 | 42.63 | 75.41 |

| Hotel | 53.46 | 11.70 | 31.64 | 52.89 | 82.53 | |

| Service | 53.55 | 10.60 | 32.45 | 53.98 | 72.39 | |

| G (Governance) | Food | 52.60 | 11.04 | 24.47 | 53.06 | 79.55 |

| Hotel | 58.03 | 11.75 | 28.55 | 57.20 | 81.07 | |

| Service | 53.92 | 11.06 | 27.49 | 54.55 | 77.07 | |

| ROA (%) | Food | 9.35 | 11.40 | −34.96 | 11.43 | 38.68 |

| Hotel | 5.53 | 5.73 | −24.51 | 5.22 | 19.75 | |

| Service | 3.88 | 9.09 | −28.79 | 3.01 | 22.59 | |

| Tobin’s Q | Food | 1.58 | 0.94 | 0.39 | 1.28 | 4.95 |

| Hotel | 1.31 | 0.84 | 0.18 | 1.00 | 3.94 | |

| Service | 1.34 | 1.07 | 0.33 | 1.11 | 8.49 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, C.-M.; Wu, T.-P. Non-Linear Dynamics: ESG Investment and Financial Performance Heterogeneity in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411010

Wang C-M, Wu T-P. Non-Linear Dynamics: ESG Investment and Financial Performance Heterogeneity in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411010

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Chien-Ming, and Tsung-Pao Wu. 2025. "Non-Linear Dynamics: ESG Investment and Financial Performance Heterogeneity in the Tourism Industry" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411010

APA StyleWang, C.-M., & Wu, T.-P. (2025). Non-Linear Dynamics: ESG Investment and Financial Performance Heterogeneity in the Tourism Industry. Sustainability, 17(24), 11010. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411010

_Li.png)