Bioelectricity Generation from Cucumis sativus Waste Using Microbial Fuel Cells: A Promising Solution for Rural Peru

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Substrate Preparation

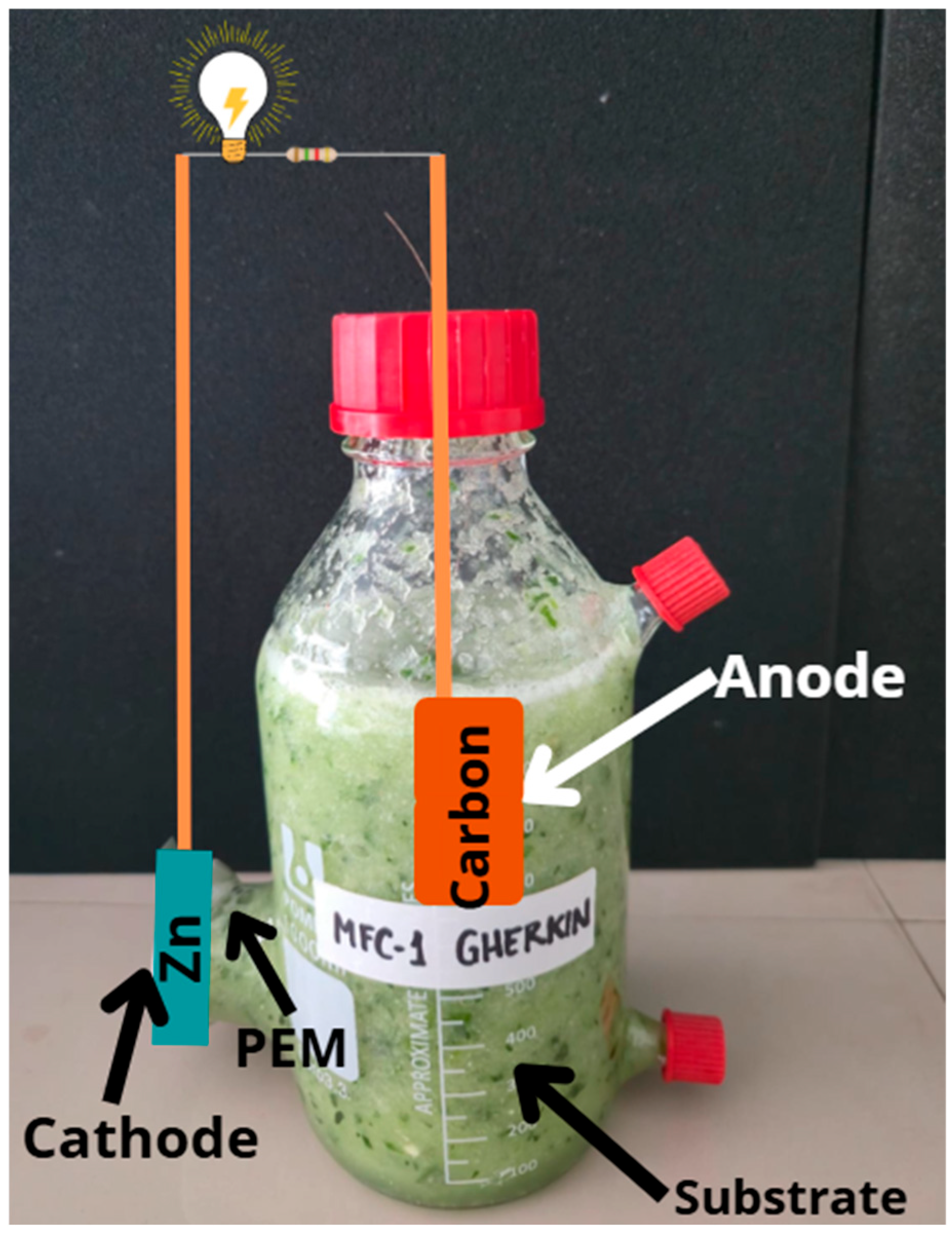

2.2. Experimental Design of the MFCs

2.3. Inoculum Preparation and Acclimation

2.4. Recovery and Cultivation of Anodic Microorganisms

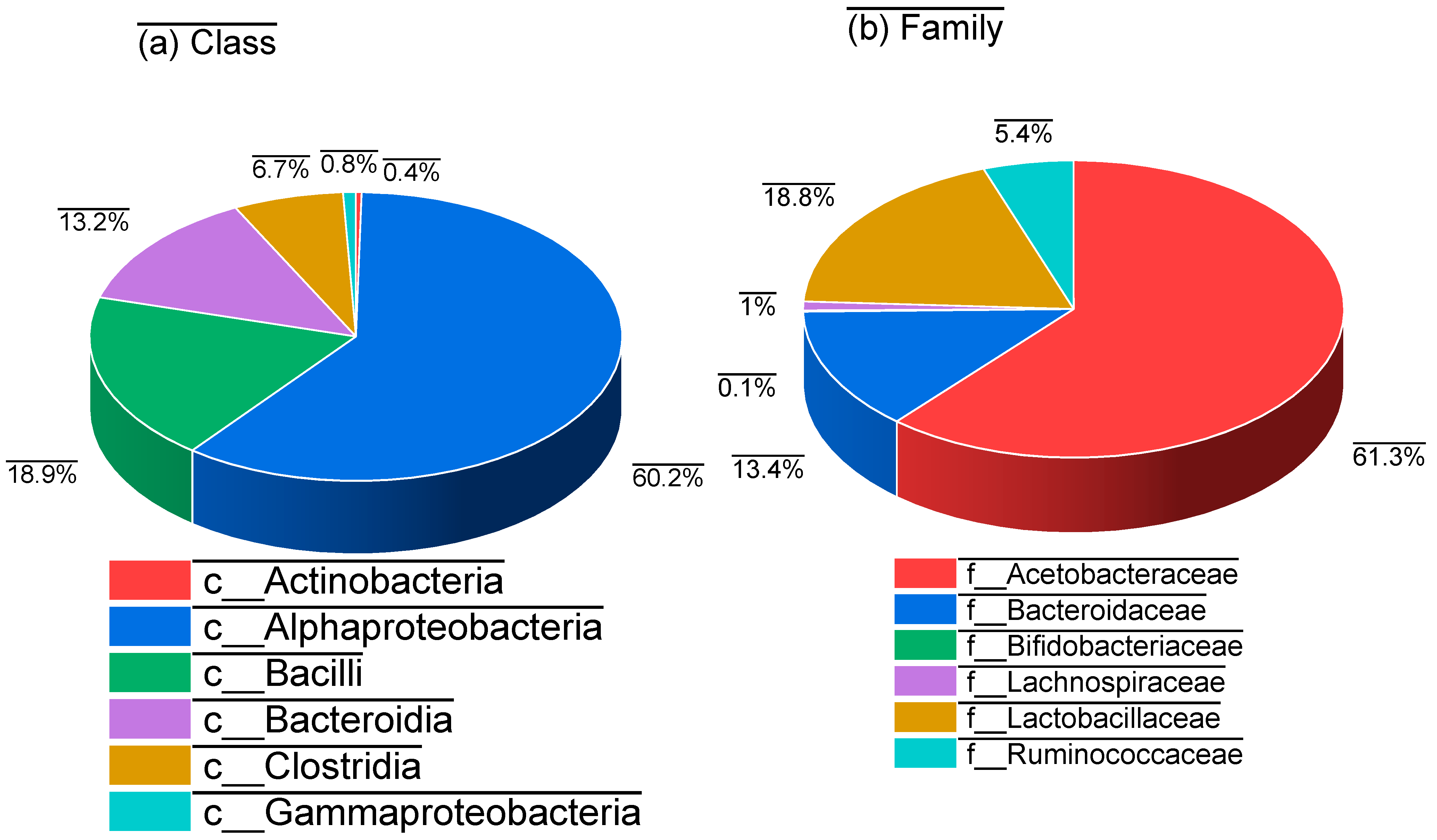

2.5. Metagenomic Analysis of Anodic Biofilms

2.6. Monitoring of Physicochemical and Electrical Parameters

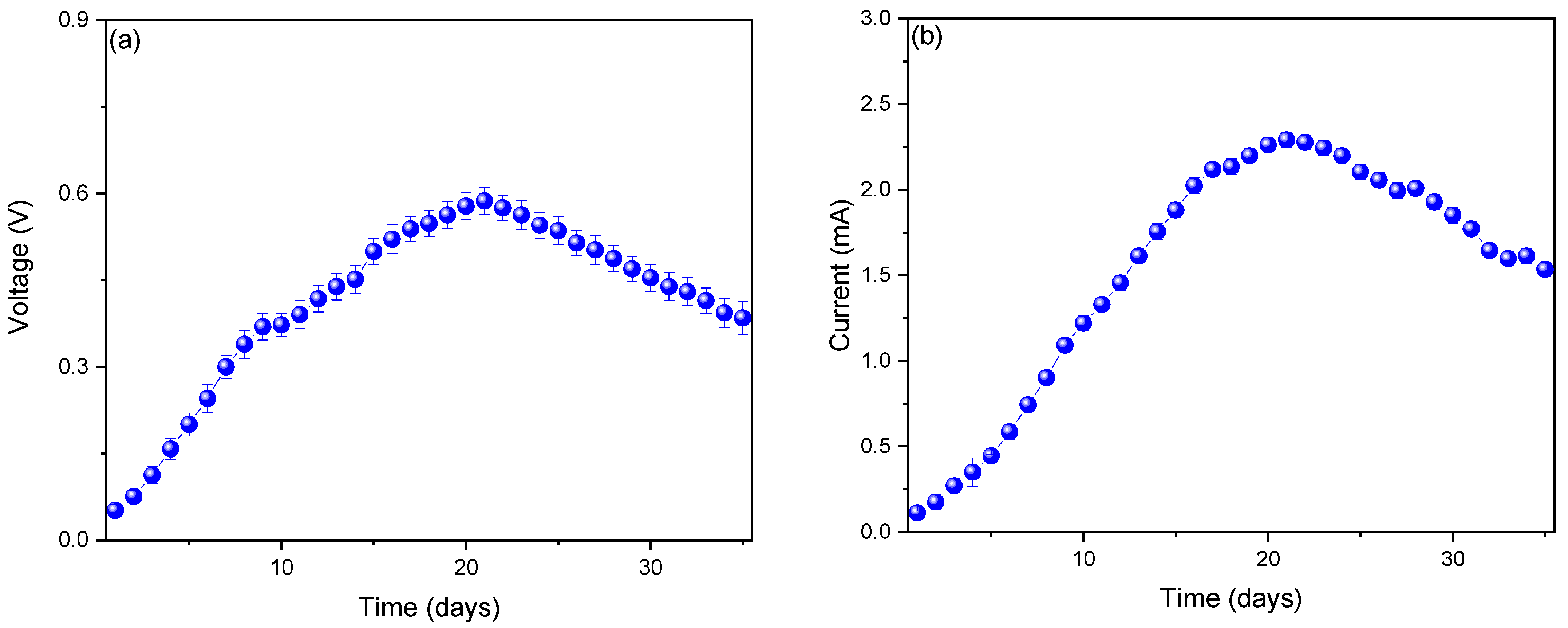

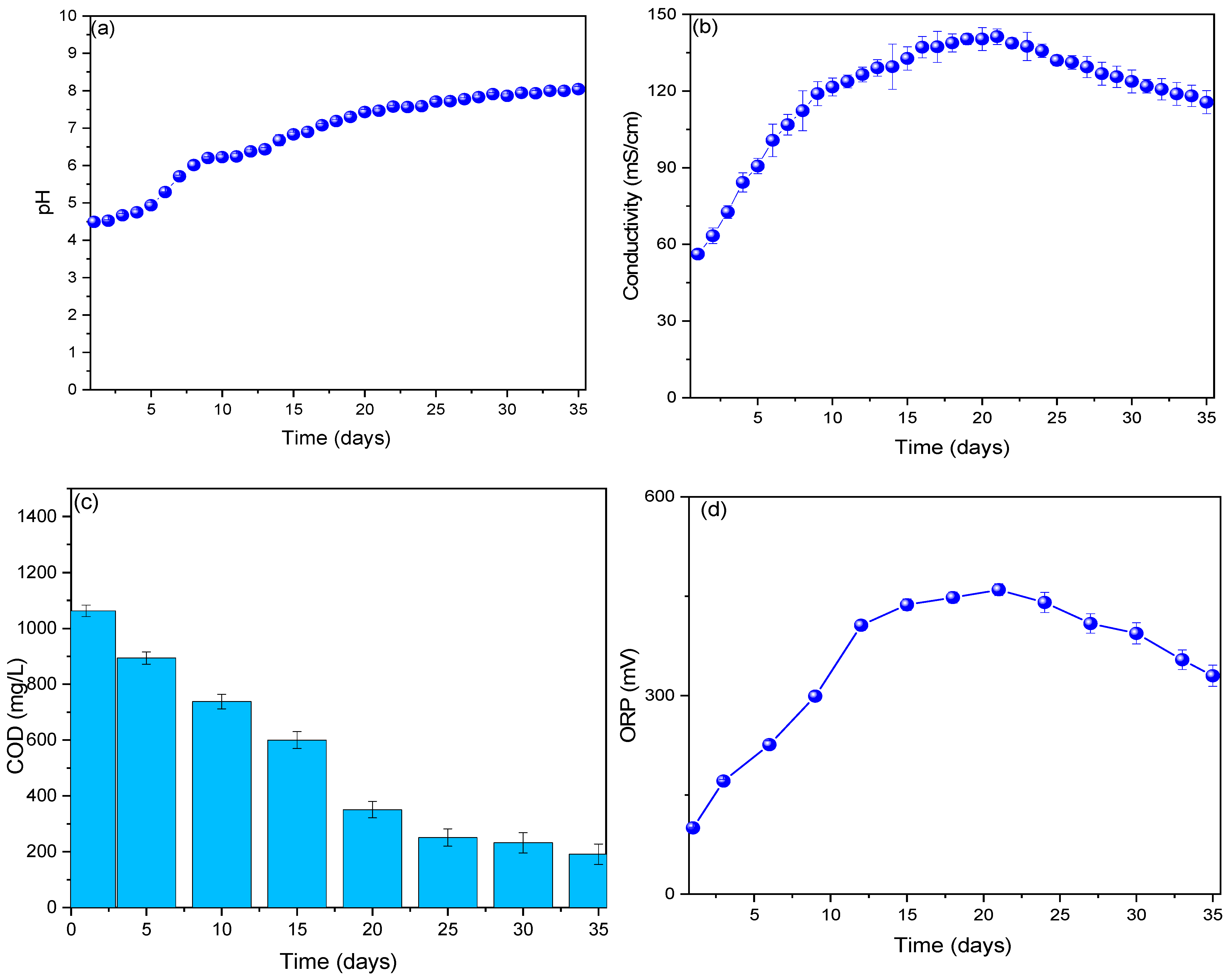

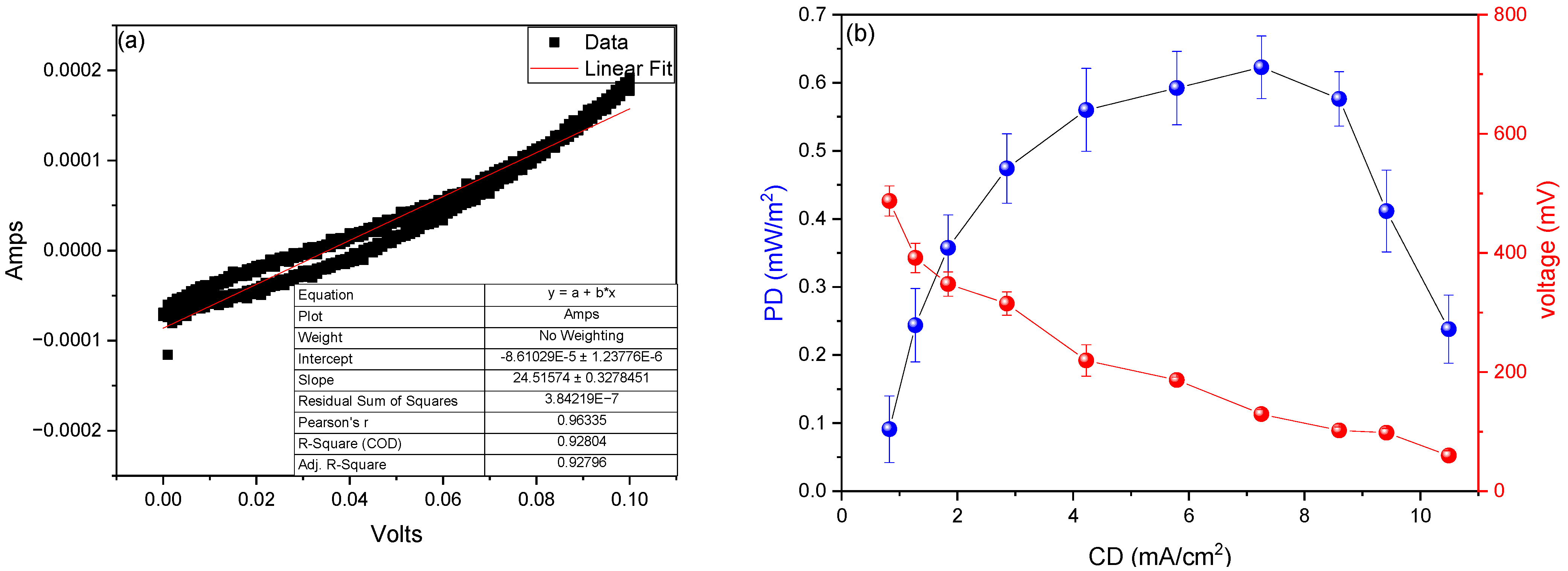

3. Results and Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vega, L.P.; Bautista, K.T.; Campos, H.; Daza, S.; Vargas, G. Biofuel production in Latin America: A review for Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, Chile, Costa Rica and Colombia. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arista-López, D.R. Solid waste research in Scopus (2002–2023): A study based on the Peru scientific production. Iberoam. J. Sci. Meas. Commun. 2025, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, B.V.D.L.; Cordeiro, N.G.; Bocardi, V.B.; Fernandes, G.R.; Pereira, S.C.L.; Claro, R.M.; Duarte, C.K. Food loss and food waste research in Latin America: Scoping review. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2024, 29, e04532023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miramontes-Martínez, L.R.; Rivas-García, P.; Briones-Cristerna, R.A.; Abel-Seabra, J.E.; Padilla-Rivera, A.; Botello-Álvarez, J.E.; Alcalá-Rodríguez, M.M.; Levasseur, A. Potential of electricity generation by organic wastes in Latin America: A techno-economic-environmental analysis. Biomass Convers. Biorefinery 2024, 14, 27113–27124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golowczyc, M.; Gomez-Zavaglia, A. Food Additives Derived from Fruits and Vegetables for Sustainable Animal Production and Their Impact in Latin America: An Alternative to the Use of Antibiotics. Foods 2024, 13, 2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realpe, N.G.; Scalco, A.R.; Brancoli, P. Exploring risk factors of food loss and waste: A comprehensive framework using root cause analysis tools. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2024, 9, 100108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegre-Bravo, A.; Stedman, R.C.; Anderson, C.L. Rethinking the role of indicators for electricity access in Latin America: Towards energy justice. Appl. Energy 2025, 379, 124877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Gómez, J.; Espinoza, V.S. Challenges and Opportunities for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Latin America. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Icaza, D.; Vallejo-Ramirez, D.; Siguencia, M.; Portocarrero, L. Smart Electrical Planning, Roadmaps and Policies in Latin American Countries Through Electric Propulsion Systems: A Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, D.B.; Rathoure, A.K. Environmental Aspects in Electrical Energy Generation: A Comprehensive Review. In Renewable Energy Development: Technology, Material and Sustainability; Kumar, S., Singh, V.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; pp. 351–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, S.M.; Noor, Z.Z.; Mutamim, N.S.A.; Baharuddin, N.H.; Aris, A.; Faizal, A.N.M.; Ibrahim, R.S.; Suhaimin, N.S. A critical review of ceramic microbial fuel cell: Economics, long-term operation, scale-up, performances and challenges. Fuel 2024, 365, 131150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.; Ma, B.; Hua, S.; Ping, R.; Ding, L.; Tian, B.; Zhang, X. Chitosan-based injectable hydrogel with multifunction for wound healing: A critical review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 333, 121952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Li, H.; Guo, S.; Li, C. Metal-based cathode catalysts for electrocatalytic ORR in microbial fuel cells: A review. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024, 35, 109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; An, C.; Jia, H.; Wang, J. Exploring novel approaches to enhance start-up process in microbial fuel cell: A comprehensive review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 63, 105425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidis, T.; Tremouli, A.; Lyberatos, G. Architecture Optimization of a Single-Chamber Air-Cathode MFC by Increasing the Number of Cathode Electrodes. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate-Gaviria, L.; García-Rodríguez, O.; Flota-Bañuelos, M.; Del Rio Jorge-Rivera, F.; Cámara-Chalé, G.; Domínguez-Maldonado, J. Stacked-MFC into a typical septic tank used in public housing. Biofuels 2016, 7, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Condori, M.A.M.; Gutierrez, M.E.V.; Oviedo, R.D.N.; Choix, F.J. Valorization of nutrients from fruit residues for the growth and lipid production of Chlorella sp.: A vision of the circular economy in Peru. J. Appl. Phycol. 2024, 36, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olennikov, D.N.; Kashchenko, N.I. Green waste from cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) cultivation as a source of bioactive flavonoids with hypolipidemic potential. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, T. The Growth of the Fruit and Vegetable Export Industry in Peru; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 1926; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Taguchi, K. A compact, membrane-less, easy-to-use soil microbial fuel cell: Generating electricity from household rice washing wastewater. Biochem. Eng. J. 2022, 179, 108338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daud, N.N.M.; Ahmad, A.; Yaqoob, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.N.M. Application of rotten rice as a substrate for bacterial species to generate energy and the removal of toxic metals from wastewater through microbial fuel cells. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62816–62827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, V.; Dutta, S.; Murugesan, P.; Moses, J.A.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Electricity production using food waste: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 839–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhim, D.; Vitarisma, I.; Sumari, S.; Utomo, Y.; Asrori, M. Optimizing Household Wastes (Rice, Vegetables, and Fruit) as an Environmentally Friendly Electricity Generator. J. Renew. Mater. 2024, 12, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamperidis, T.; Pandis, P.K.; Argirusis, C.; Lyberatos, G.; Tremouli, A. Effect of food waste condensate concentration on the performance of microbial fuel cells with different cathode assemblies. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N.; Amin, Z.; Arshad, S.E. Bioelectricity generation using banana peel as substrate in dual-chamber Pseudomonas aeruginosa based microbial fuel cell. Malays. J. Microbiol. 2023, 19, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, R.; Gundepuri, I.S.; Ghangrekar, M.M. High specific surface area graphene-like biochar for green microbial electrosynthesis of hydrogen peroxide and Bisphenol A oxidation at neutral pH. Environ. Res. 2025, 275, 121374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Lee, H.; Choi, S.; Suh, S.; Im, S.B.; Kim, Y.G.; Ku, B.M.; Ahn, M.-J.; Jeong, B.-S.; Oh, B.H. Computational design of monomeric Fc variants with distinct pH-responsive FcRn-binding profiles. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Han, X.; Shan, Y.; Li, F.; Shi, L. Biofilm biology and engineering of Geobacter and Shewanella spp. for energy applications. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 786416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morales, C.; Solís, S.; Bacame, F.J.; Reyes-Vidal, M.Y.; Manríquez, J.; Bustos, E. Electrical stimulation of Cucumis sativus germination and growth using IrO2-Ta2O5| Ti anodes in Vertisol pelic. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 161, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Duan, C.; Duan, W.; Sun, F.; Cui, H.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X. Role of electrode materials on performance and microbial characteristics in the constructed wetland coupled microbial fuel cell (CW-MFC): A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 301, 126951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Ma, S.; Ma, P.; Cao, R.; Tian, X.; Lu, Y.; Li, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Lu, X. Waste biomass durian shell carbon to derive N-rich porous microbial fuel cell anode for simultaneous dye degradation and electricity generation. Bioresour. Technol. 2025, 436, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Li, J. Exogenous electric field as a biochemical driving factor for extracellular electron transfer: Increasing power output of microbial fuel cell. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 301, 118050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, B.; Soundararajan, N.; Kashyap, S.P.; Jang, J.H.; Wang, C.T.; Katha, A.R.; Katiyar, V. Bioaugmented polyaniline decorated polylactic acid nanofiber electrode by electrospinning technique for real wastewater-fed MFC application. Int. J. Energy Res. 2022, 46, 3588–3601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Sharma, P. Recent advances in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2022, 97, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pişkin, E.D.; Nevimgenç, N. Waste Activated Sludge Oxidation and Azo Dye Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell: Optimization of Process Conditions for High Electricity Generation and Waste Treatability; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Stevic, N.; Korac, J.; Pavlovic, J.; Nikolic, M. Binding of transition metals to monosilicic acid in aqueous and xylem (Cucumis sativus L.) solutions: A low-T electron paramagnetic resonance study. Biometals 2016, 29, 945–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Hao, L.; Cao, J.; Zhou, K.; Fang, F.; Feng, Q.; Luo, J. Mechanism of Fe–C micro-electrolysis substrate to improve the performance of CW-MFC with different factors: Insights of microbes and metabolic function. Chemosphere 2022, 304, 135410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Lu, X.; Xiang, C.; Li, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Gao, L.; Zhang, W. Genome-wide characterization of graft-transmissible mRNA-coding P450 genes of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 250–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almatouq, A.; Babatunde, A.O. Concurrent phosphorus recovery and energy generation in mediator-less dual chamber microbial fuel cells: Mechanisms and influencing factors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kargi, F.; Eker, S. Electricity generation with simultaneous wastewater treatment by a microbial fuel cell (MFC) with Cu and Cu–Au electrodes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. Int. Res. Process Environ. Clean Technol. 2007, 82, 658–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guadarrama-Pérez, O.; Guadarrama-Pérez, V.H.; Guevara-Pérez, A.C.; Guillén-Garcés, R.A.; Treviño-Quintanilla, L.G. Celdas de Combustible Microbianas: Una Evolución Sustentable en la Producción de Bioelectricidad. Alianzas Tend. BUAP 2025, 10, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Conde García, R.G.; Espinoza Coral, M.C. Evaluación de dos Biofiltros Usando Estropajo Común (Luffa cylindrica) y Yanchama (Poulsenia armata) en el Tratamiento de Aguas Residuales; Escuela Superior Politécnica de Chimborazo: Riobamba, Ecuador, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, S.V.; Raghavulu, S.V.; Sarma, P.N. Biochemical evaluation of bioelectricity production process from anaerobic wastewater treatment in a single chambered microbial fuel cell (MFC) employing glass wool membrane. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2008, 23, 1326–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, P.; Abbassi, R.; Garaniya, V.; Lewis, T.; Yadav, A.K. Performance of pilot-scale horizontal subsurface flow constructed wetland coupled with a microbial fuel cell for treating wastewater. J. Water Process Eng. 2020, 33, 100994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segundo, R.F.; Luis, C.C.; Otiniano, N.M.; De La Cruz-Noriega, M.; Gallozzo-Cardenas, M. Utilization of Cheese Whey for Energy Generation in Microbial Fuel Cells: Performance Evaluation and Metagenomic Analysis. Fermentation 2025, 11, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, S.H.; Pérez, C.M.; Panta, J.E.R.; Ayala, C.R.; Ruiz, A.M.; Martínez, P.G. Evaluación de la Eficiencia Hídrica de la Combinación de Tezontle y Composta Ovino en Diferentes Proporciones. In Proceedings of the IX Congreso Nacional y II Congreso Internacional de Riego, Drenaje y Biosistemas, Chapingo, Mexico, 23–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Navya, B.; Babu, S. Comparative metataxonamic analyses of seeds and leaves of traditional varieties and hybrids of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) reveals distinct and core microbiome. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Reza, M.N.; Ahmed, S.; Samsuzzaman; Lee, K.H.; Cho, Y.J.; Noh, D.H.; Chung, S.O. Nutrient stress symptom detection in cucumber seedlings using segmented regression and a mask region-based convolutional neural network model. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Man, Y.; Dai, Y.; Fu, J.; Wei, T.; Tai, Y.; Zhang, X. Curbing per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs): First investigation in a constructed wetland-microbial fuel cell system. Water Res. 2023, 230, 119530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, L.; Zheng, Q.; Zhuang, Q.; Guan, M.; Yin, Z.; Zeng, J.; Chen, H.; Wu, W.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, X. Antibacterial microfibrillated cellulose as stimuli-responsive carriers with enhanced UV stability for sustained release of essential oils and pesticides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 6666–6681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Verástegui, L.L.; Ramírez-Zavaleta, C.Y.; Capilla-Hernández, M.F.; Gregorio-Jorge, J. Viruses infecting trees and herbs that produce edible fleshy fruits with a prominent value in the global market: An evolutionary perspective. Plants 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Komkhum, T.; Sema, T.; Rehman, Z.U.; In-Na, P. Carbon dioxide removal from triethanolamine solution using living microalgae-loofah biocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Parameter | Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Moisture content | 94–96% | [18,19] |

| Total carbohydrates | 3.0–3.8% | [18] |

| Reducing sugars | 1.5–2.2% | [18] |

| Dietary fiber | 0.8–1.2% | [19] |

| Crude protein | 0.6–0.9% | [19] |

| Lipids | 0.1–0.3% | [19] |

| Ash | 0.4–0.6% | [19] |

| Initial COD | 10,600 ± 200 mg/L | This study |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rojas-Flores, S.J.; Liza, R.; Nazario-Naveda, R.; M. Benites, S.; Delfin-Narciso, D.; Gallozzo Cardenas, M. Bioelectricity Generation from Cucumis sativus Waste Using Microbial Fuel Cells: A Promising Solution for Rural Peru. Sustainability 2025, 17, 11007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411007

Rojas-Flores SJ, Liza R, Nazario-Naveda R, M. Benites S, Delfin-Narciso D, Gallozzo Cardenas M. Bioelectricity Generation from Cucumis sativus Waste Using Microbial Fuel Cells: A Promising Solution for Rural Peru. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):11007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411007

Chicago/Turabian StyleRojas-Flores, Segundo Jonathan, Rafael Liza, Renny Nazario-Naveda, Santiago M. Benites, Daniel Delfin-Narciso, and Moisés Gallozzo Cardenas. 2025. "Bioelectricity Generation from Cucumis sativus Waste Using Microbial Fuel Cells: A Promising Solution for Rural Peru" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 11007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411007

APA StyleRojas-Flores, S. J., Liza, R., Nazario-Naveda, R., M. Benites, S., Delfin-Narciso, D., & Gallozzo Cardenas, M. (2025). Bioelectricity Generation from Cucumis sativus Waste Using Microbial Fuel Cells: A Promising Solution for Rural Peru. Sustainability, 17(24), 11007. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172411007