Abstract

The rapid growth of urban populations and the disorderly expansion of city sizes present severe challenges to China’s urban environment. This paper explores the value of urban agriculture (UA) in China for promoting sustainable urban development through a framework spanning national, city, and case study levels. At the national level, it details the crises facing Chinese cities and the historical development of UA. At the city level, it outlines the development and current status of UA in three cities. At the case study level, it introduces the fundamental contexts of three cases and analyses their commonalities and distinctive features through an examination of their ecological, managerial, social, and productive contributions. Concurrently, this study designs a comprehensive UA evaluation system to quantify research data. The assessment framework encompasses four dimensions of UA, comprising twelve indicators. Employing a hierarchical literature analysis combined with qualitative-quantitative methodologies, the research aims to explore the value of China’s urban agricultural advantages from multiple perspectives. Through comparative analysis of case data, this paper further clarifies the significance of developing UA for China’s sustainable urban development.

1. Introduction

Rapid urban development has precipitated a series of urban challenges. Given the aesthetic, ecological, and productive functions of agricultural landscapes, they have progressively attracted attention from scholars across various disciplines. As early as 1935, Japanese scholar Aoka Shiro introduced the academic concept of urban agriculture (UA) in his work Agricultural Economic Geography [1]. UA combines agricultural and landscape functions while simultaneously generating social value, thereby emerging as one of the most effective means to address urban crises. China is a developing nation situated in East Asia. Its vast territory ranks as the world’s third-largest in land area. Encompassing tropical, temperate, and frigid zones, it exhibits diverse climatic patterns. This expansive geography yields rich landscapes including lakes, mountains, deserts, glaciers, and plains. However, arable and forested land constitute a smaller proportion than mountainous terrain, with deserts occupying 12% of the land area. Since initiating reform and opening-up in 1978, China’s economy has expanded rapidly, establishing itself as the world’s second-largest economy. In 2021, China’s population stood at 1.41 billion, representing approximately 18% of the global population [2]. Concurrently, China’s urbanisation has advanced rapidly, with the urbanisation rate reaching 60% [3]. From just 199 cities in the 1950s, the number grew to 672 by 2021 [4], making China one of the world’s fastest urbanising nations. This urbanisation has driven increasing migration to cities. The proportion of the population residing in urban areas has risen from 16.2% in 1960 to 61.4% in 2020 [3]. Due to the rapid expansion of urbanisation and the absence of effective scientific management, a series of issues—including loss of arable land, food shortages, food safety concerns, and environmental pollution—have become commonplace in Chinese cities. Regarding arable land, data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China (2018) indicates that over the past four decades, per capita arable land in China has decreased from 103.3 m2 to 64.7 m2 [4]. Between 1990 and 2018, the total area of farmland declined from 124.4 million hectares to 119.4 million hectares [3]. This trend highlights the significant crisis posed by China’s urban development to arable land resources. Regarding food, China relies heavily on imports for the majority of its provisions. In 2020, China imported 41.8 million tonnes of grain, making it the world’s largest importer of cereals [2]. From 2000 to 2020, the proportion of imported food within China’s total merchandise imports increased from 4.0% to 5.8% [3]. Furthermore, urban food supplies remain insecure. For instance, in 2024, China’s agricultural sector reported 12 food safety incidents affecting multiple cities, involving common foods such as vegetables and fruit consumed daily by citizens [5]. These figures concretely illustrate the Chinese food system’s dependence on external markets and its inherent security risks, further highlighting its vulnerability. Regarding water resources, according to 2024 Chinese government statistics, per capita water availability in China stands at merely 35% of the global average [6]. Concurrently, increased impervious surfaces have disrupted urban water cycles and hindered groundwater recharge, resulting in nearly two-thirds of Chinese cities currently experiencing water shortages [7]. Regarding municipal waste, the Ministry of Housing and Urban–Rural Development noted in 2018 that two-thirds of China’s over 600 large and medium-sized cities were burdened by urban waste management challenges. Furthermore, one-quarter of these cities lacked suitable waste disposal sites [8]. From 2011 to 2019, China’s urban domestic waste generation exhibited a linear growth trend. In 2013, large and medium-sized Chinese cities produced 161 million tonnes of domestic waste, rising to 235 million tonnes by 2019—representing an annual growth rate of 6.51% [9,10,11]. The frequent occurrence of urban environmental issues in China reflects a severe imbalance within its ecological cycle system. The aforementioned specific data clearly indicates that the sustainable development of most Chinese cities faces significant challenges. As a vital component of urban green infrastructure, urban agricultural landscapes can mitigate these issues to a certain extent. They enhance urban ecosystems, boost biodiversity, integrate urban green spaces, and further promote sustainable urban development. In terms of environmental enhancement, UA converts waste into organic fertilisers, alleviating municipal waste burdens. For instance, the 2020 Paris Railway Farm project collected 20 tonnes of organic waste for composting, achieving circular waste utilisation [12]. Concurrently, by reducing food transport distances, UA lowers greenhouse gas emissions during food distribution. According to Barrs (1997), UA can reduce carbon emissions by 22% [13]. Furthermore, it regulates local microclimates and lowers rainwater runoff temperatures, mitigating the urban heat island effect. For instance, Holmes (2020) documented that Thammasat University’s terraced rooftop farm in Thailand recovers 11,718 cubic metres of rainwater annually [14]. Regarding food security, UA both alleviates urban food crises and enhances food safety. The rooftop garden at Chicago’s Gary Comer Youth Centre produces sufficient vegetables daily to meet the nutritional needs of 175 children [15]. Concerning arable land, UA utilises idle urban spaces, improving land utilisation rates and economic efficiency. For instance, Walsh et al. (2022) indicate that urban green spaces in the UK yield 20–22 tonnes of fruit and vegetables annually [16]. Thus, UA represents an effective approach to addressing urban ecological and social crises. Scholars have conducted research and practical work on China’s urban agricultural landscapes. However, most existing academic literature on urban agricultural landscapes remains confined to exploring singular values, such as production value. This study employs a hierarchical research methodology across national, city, and case levels to analyse diverse geographical contexts. Concurrently, it establishes a Chinese UA case evaluation system, conducting a comprehensive and systematic investigation into sustainable urban agricultural landscapes in China.

2. Materials and Methods

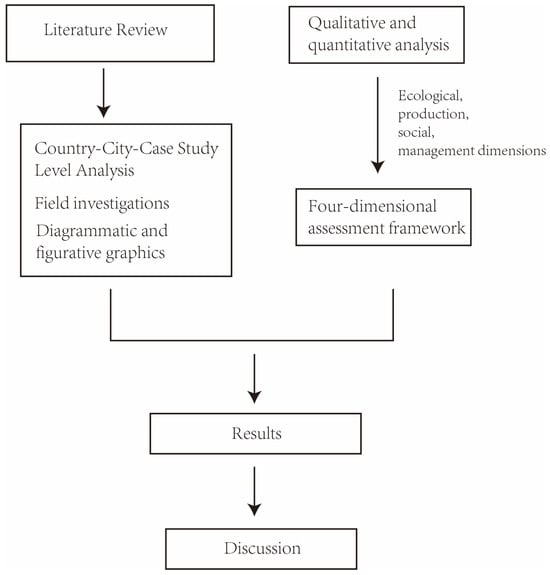

This study employs a combined approach of literature review and qualitative-quantitative analysis, exploring China’s urban agricultural landscapes through specific case studies. The two research methods are interrelated. The literature review method identifies the crises currently facing Chinese cities, the history of UA in China, and potential opportunities. It also details the background of the study areas and case studies, including the history and current status of UA in each region and the landscape spatial design of each case. Quantitative analysis examines the crises in China’s UA from ecological, productive, managerial, and social perspectives. Data quantification is used to evaluate the performance of the study samples across these dimensions, further exploring the current strengths and challenges of China’s UA. Figure 1 presents the research flowchart.

Figure 1.

The research flowchart.

2.1. Literature Review

Literature analysis serves as the foundational methodology for establishing the background, context, and developmental trajectory of this study’s UA framework. To ensure scientific rigour and logical coherence, this paper employs a progressive three-tiered structure: national, city, and case study levels. These correspond, respectively, to literature reviews on China’s UA, exploration of UA initiatives across various cities, and analysis of specific UA case studies. The literature analysis aims to clearly articulate the study’s conceptual framework, directional positioning, and content composition.

At the national level, this study utilises objective data from scientific reports published by authoritative bodies such as the United Nations. It analyses the shortcomings in China’s current urban development from the perspectives of environmental issues, urban expansion, and food supply, thereby lending greater persuasiveness to urban-related topics. Regarding the historical development and current state of China’s UA, this study employs a combined approach using the Web of Science Core Collection database and the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) database from China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI). The selection of these two databases is based on the following reasons: (1) The Web of Science database offers extensive coverage, with its Core Collection demonstrating greater scientific rigour through peer-reviewed publications. (2) CNKI is a widely used academic database in China, with its CSSCI database representing the most authoritative collection of scholarly literature in the country. Existing literature reveals the practical challenges confronting China’s current developmental phase and their relevance to research. It further elucidates the historical trajectory and present state of China’s UA. At the urban level, this study selected Shanghai, Shenzhen and Shenyang as case cities. Literature on UA in each city was systematically collated using Google Scholar and official documents. This paper outlines their demographic and climatic conditions, focusing on analysing the developmental trajectory of agricultural zoning within these regions, assessing current status, and examining relevant policies, planning frameworks and practical initiatives. At the case study level, the research selected the most representative UA projects from each city as research samples: Shanghai’s The Knowledge and Innovation Community Garden, Shenzhen’s Value Farm, and Shenyang’s Rice Field Landscape. This study’s case analysis draws upon extensive online resources, including official documents, academic papers, and interview transcripts, to extract research-worthy information for in-depth examination. It outlines each case’s context, environmental factors, design philosophy, and methodology. At the same time, field visits to selected sites were conducted to fully comprehend their landscape spaces, plant characteristics, and site conditions, thereby supplementing the limitations of secondary sources regarding granular details. Furthermore, visual diagrams were created using official charts and on-site photographs to enhance case comprehension through concrete representation.

Through analysis of the existing literature, current research on urban agriculture in China still exhibits three key shortcomings. First, most studies lack cross-city comparisons. They predominantly discuss the development experiences of individual cities without fostering discussions across different urban types. This limitation prevents current research from adequately explaining the variations and characteristics of urban agriculture across cities. For instance, Song & Yang studied the interaction between urban agriculture and carbon effects in Guangzhou, China, proposing corresponding policy recommendations [17]. However, this research remains confined to Guangzhou. Second, existing literature fails to establish a systematic, multi-level research framework spanning macro, meso, and micro scales. Studies typically address only one or two analytical levels. This limitation results in fragmented logic and discontinuous analysis. For instance, Zhu et al. proposes management strategies to advance China’s urban agriculture based on its strengths and limitations [18]. Yet this research analyses only the macro-level scale of China, without specific discussion of Chinese cities or case studies. This diminishes the study’s depth and persuasiveness. Third, while existing literature describes the three projects, analysis often remains confined to introducing project contexts and design philosophies, or exploring single dimensions. A small portion of studies examines isolated aspects like design strategies, yet they lack multidimensional case evaluations and comprehensive cross-case comparisons—particularly systematic analysis of projects’ productive and ecological contributions. Literature on Shanghai’s Creative Agriculture Park primarily focuses on spatial design and social relations [19,20]. These studies lack analysis of the project’s sustainable value and multidimensional assessment. Value Farm’s exploration emphasizes spatial functionality and cultivation advantages [21,22]. These texts fail to conduct in-depth comparative analysis across multiple dimensions. Research on the Rice Field Landscape concentrates on describing project design and functions [23,24]. These studies do not employ scientific methods for comprehensive exploration.

This study addresses existing research gaps and enhances innovation in the field. Its innovations manifest in four key aspects. First, it conducts a comparative analysis of Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Shenyang—cities differing in climate, typology, and economy. This clearly articulates the variations and strengths of urban agriculture across these cities while establishing a systematic framework for cross-city comparisons. Second, this study examines China’s urban agriculture across three scales: national, city, and case study. It enhances contextual connections within China’s urban agriculture discourse, deepening understanding of the field. By linking case experiences to broader systemic frameworks, it strengthens the persuasiveness of research findings. Furthermore, through comprehensive discussions of ecological, production, management, and social dimensions across cases, this study aims to address existing research gaps characterized by incompleteness and superficiality. Furthermore, based on a systematic analysis of projects, this study designs an urban agriculture evaluation framework. It seeks to clarify the differences and commonalities among projects, enabling a scientific comparison of China’s urban agriculture initiatives across multiple dimensions.

Through a literature review, this paper not only outlines existing research directions but also demonstrates connections between studies. It provides a comprehensive understanding of China’s urban agriculture development. This research aims to offer an empirical foundation and further broaden research perspectives. Simultaneously, by conducting an in-depth comparative analysis of three cities and their representative cases, this paper contributes to the theoretical and practical framework for the rapid development of China’s urban agriculture system.

2.2. Qualitative Quantitative Analysis

Qualitative quantification refers to the process of converting information from literature reviews, originally presented in textual descriptions, into accessible data formats. Simply put, it involves the transformation of non-numerical data into numerical values. This enhances the analysability and comparability of research. Concurrently, quantified information can be rendered in chart and graph formats, lending visual clarity to the study. This study systematically reviews and synthesises multiple scholars’ UA assessment frameworks and methodologies to construct its case evaluation system. Li & Zhou examined contributions across production, economic, social, and ecological service dimensions using multiple cities as samples [25]. Peng et al. selected ten measurable indicators across ecological, economic, and social aspects to explore UA in Beijing’s diverse districts [26]. John & Artmann proposed a comprehensive assessment model measuring UA sustainability across environmental, social, and economic dimensions [27]. Teitel-Payne et al. designed evaluation indicators emphasising UA’s importance for health, society, economy, and ecology [28]. Gullino et al. examined multifunctional UA management values using the representative case study of Chiari, Italy [29].

This paper synthesises the methodologies of the aforementioned scholars to develop a case assessment framework for UA, enabling the quantification of sample data. The framework examines UA cases across four dimensions: management, social, ecological, and production. Three indicators were selected for each dimension, resulting in a total of twelve UA indicators. Indicator selection synthesises key metrics from John & Artmann, Li & Zhou, Peng et al., Gullino et al., Gianluca et al., Giacchè et al. and others, renaming them. The management dimension comprises three indicators: administrators, maintenance, and generation pathways [29,30]. These indicators effectively measure project governance models, operational methodologies, and resource allocation, thereby influencing the rationality of UA management. Regarding production, the discussion encompasses production types, yield, and production cycles [25,26,28]. These metrics clarify UA’s direct contributions to food supply, production efficiency, and production continuity. At the ecological dimension, analysis focuses on urban sustainability, organic agriculture, and species diversity [25,26,27]. These indicators assess UA’s role within ecosystems and reflect its positive environmental impacts. In the social dimension, exploration centres on organisational activities, educational value, and social conflict mitigation indicators [26,27,31]. These indicators elucidate the value of projects in fostering community cohesion and social equity, embodying the social functions and cultural significance of UA. Concurrently, this study employs a Likert scale to establish precise scoring criteria. This methodology is widely applied in quantitative surveys and effectively addresses complex issues [32]. Each indicator is measured on a 0–4 scale, where 0 denotes “absent” or “lowest level” and 4 represents “highest level”. This approach fully reflects the degree of variation across projects in different dimensions while avoiding information loss from simplistic binary scoring, thereby enhancing the reproducibility and scientific rigour of the evaluation system [33]. Table 1 presents the indicators, descriptions, and measurement standards for each dimension.

Table 1.

The indicators, descriptions, and measurement standards for each dimension.

2.3. Methodology for Indicator Measurement

To ensure scientific rigour and validity, this study employs the Entropy Weight Method to determine the weightings of twelve indicators. As an objective weighting approach, the Entropy Weight Method has found extensive application across various quantitative evaluation systems [25,34]. The weights established by this method are derived solely from the sample data itself, thereby circumventing potential data bias arising from subjective weighting [35,36]. Concurrently, the entropy method effectively expresses the informational entropy value of indicators, particularly in the comprehensive evaluation of multidimensional metrics [37,38]. For instance, Cerreta employed the Entropy Weight Method to assess the multifunctional landscape of the National Park of Cilento, Vallo di Diano and Alburni [39]. The calculation formula is as follows:

In Formula (1):

- denotes the number of evaluation subjects;

- denotes the evaluation subject;

- denotes the evaluation indicator;

- denotes the raw value of the -th evaluation subject for the -th indicator;denotes the proportion of the -th subject for the -th indicator.

In Formula (2):

- ;

- denotes the information entropy of the -th indicator.

In Formula (3):

- ;

- denotes the weight of the -th indicator.

In Formula (4):

- denotes the score of the -th evaluation subject.

2.4. The Historical Background of UA in China and Its Significance in Urban Landscape Research

Ancient China placed great emphasis on agricultural production. Influenced by traditional Chinese culture’s prioritisation of agriculture over commerce, the ancient Chinese economy was predominantly agrarian. In ancient China there were three types of gardens, Yuan (a garden with entertainment function), You (a garden with poultry and animals), Pu (a garden with production) (Figure 2). Chinese UA originated from classical Chinese gardens, possessing a long history. The earliest Chinese gardens appeared during the Western Zhou Dynasty (1046–771 BCE). Gardens with recreational, religious, and productive functions were found within imperial estates. These gardens primarily served religious and productive purposes. Subsequently, during the Qin and Han dynasties (220 BCE–221 CE), gardens were predominantly productive with limited recreational elements [40]. By the Tang dynasty (618–907), imperial gardens incorporated specialised plantations such as vineyards, pear orchards, and watermelon fields [41]. These gardens yielded vegetables, fruits, fish, and poultry [41]. During the Ming and Qing periods (1368–1912), imperial gardens cultivated rice and lotuses [42]. Moreover, many aristocrats constructed private gardens for cultivating crops and raising poultry [43,44].

Figure 2.

Three types of gardens in ancient China.

In the 1950s–1960s, the Chinese government advocated some plans to deal with the problem of food shortages, because China was extremely poor. In 1955, the government introduced the policy “1956–1967 National Agricultural Development Outline”, and the policy stated that people should grow crops with economic benefits like fruit trees, mulberry and tea tree on all available land [45]. In 1958, the First National Urban Landscaping Conference proposed the activity “Garden with Productive”. And after that, Chairman Mao Zedong proposed the plan “Land Landscaping” (the ground is full of the garden) and on this basis, “Making China a socialist country with one-third farmland, one-third forest and one-third pasture” [46]. Due to the support of the government, UA activities were rapidly developed and spread around cities. For example, a total of 677 fruit trees of 13 kinds and more than 80 kinds of medicinal plants were planted in Zhongshan park in Beijing and fish and shrimp were bred in the lake of the park [47]. These policies had the contexts of times and politics. But owing to the lack of technology and management, the activities had a certain blindness.

At the end of the 20th century, due to the rapid growth of the Chinese economy, the government paid more attention to urban construction, gradually ignoring the development of UA. Nevertheless, in the beginning of the 21st century, in China, the agricultural gardens emerged in the design and construction of residential areas because of raising awareness about the safety of food. During this period, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) is also emerging gradually [48]. In Liuzhou, the CSA project appeared and it is known as the prototype of Chinese CSA [49]. Universities, design companies, and social organizations also set up UA through collaborative approaches. In Kunming, the Kunming agriculture department, the Kunming science and technology association, and other departments launched an activity “one-meter vegetable garden” and set up a display farm about 118.8㎡ to promote the concept and planting techniques of “one-meter vegetable garden” [50]. In addition, universities have the advantage of self-research and use their advantage to build valuable UA; for instance, Hunan Agricultural University’s ‘Children’s Farm’ project [51]. Concurrently, mounting urban challenges have heightened governmental and public awareness of UA, spurring increased UA activities. For instance, authorities encourage residents to cultivate crops within cities. Nevertheless, most UA initiatives remain informal, with urban agricultural practices lacking detailed guidance and explicit policies. While no comprehensive national UA development policy exists, a handful of local governments have enacted UA measures. For example, in Hong Kong, the local government introduced the policy “Planning for Recreational and Community Farming in Hong Kong”. It allows non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to utilise the urban land to develop UA, but the produced food must meet the food safety standards [52]. Furthermore, due to the absence of proper, standardised management approaches, some agricultural activities have proven detrimental to the natural environment, such as damaging public green spaces and causing landslides.

In summary, the development of UA in China has charted a clear trajectory from meeting subsistence needs to contemporary community engagement and sustainable design. For this study, the historical review provides both theoretical and practical foundations. It not only elucidates the historical context of China’s urban agricultural evolution but also serves as the historical source for the study’s four analytical dimensions. It demonstrates the significance of production tools, technical management, ecological strategies, and social interactions within Chinese urban agricultural practices. Furthermore, it provides longitudinal support for the analysis of ‘state, city, and case’. This section constitutes the starting point of the study’s research logic, furnishing the theoretical basis for subsequent city and case analyses. Consequently, this chapter forms a crucial component of the research, fostering the paper’s coherence and integrity. This ensures the study possesses cultural depth, rigour, and scientific validity.

2.5. Study Areas

To comprehensively explore the state of UA in China, this study selected three cities—Shenyang, Shanghai, and Shenzhen—whose geographical locations, economic development models, and climatic characteristics are entirely distinct. Concurrently, they represent the urban agricultural conditions of China’s three major regions and economic belts: Northern, Eastern, and Southern. Shenyang, situated in Northern China, is a traditional industrial base. Shenzhen, located in Southern China, is characterised by an innovation-driven economy. Shanghai, positioned in Eastern China, possesses a highly developed service-oriented economy. This study delineates the environmental and urban contexts of these three regions, encompassing climate, economic development models, urban area size, population, and population density. Figure 3 illustrates the geographical positioning of the study areas within China. Table 2 details the geographical location (inland/coastal), climate, development status (developed/developing), dominant economic sector, precipitation, urban area size, population, population density, and urban positioning for each city. The following section outlines the cities hosting the case studies and their fundamental profiles, including regional UA development, project area, construction period, design objectives, and landscape expression forms to enhance understanding of the projects. This study analyses exemplary UA cases selected from Shenyang, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, respectively. Case selection adheres to four criteria. Firstly, the chosen cases must be actual, completed, and operational UA practices. They must clearly demonstrate the authentic conditions of internal agricultural production. Secondly, priority is given to projects demonstrating representativeness, exemplary value, and distinctiveness within their respective cities. Thirdly, the selected cases must be supported by diverse, comprehensive, and scientifically sound literature sources. Finally, the cases must encompass the ecological, productive, managerial, and social dimensions of UA to underpin this study’s integrated evaluation framework.

Figure 3.

The geographical locations of the study areas within China.

Table 2.

The geographical positioning, climate, development status, dominant economic type, annual precipitation, urban area, population, population density, and urban positioning of the three cities.

2.6. Case Analysis

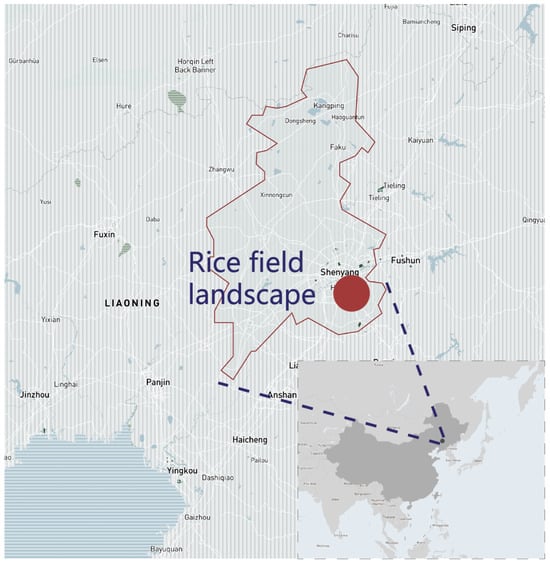

2.6.1. The Rice Field Landscape

Shenyang, historically known as China’s granary, also serves as a heavy industrial base and automotive manufacturing hub. Consequently, its urban environmental pollution is more severe than in other Chinese cities. The cold climate poses challenges for the survival of diverse flora, fauna, and insects. By 2006, Shenyang had established 137 urban agricultural parks, yet significant disparities existed in the resource allocation and development of UA across different districts. The Shenyang government in 2014 promulgated “Shenyang urban modern agriculture development planning outline” [53]. The policy mainly focused on the construction of large urban agricultural parks and development of the urban tourism agriculture, to provide enough and sustainable food for dwellers [53]. But there is no clear policy for other types of urban agricultural development.

The Rice Field Landscape is situated within Shenyang Jianzhu University in Shenyang. Designed in 2002, the project occupies a total area of 21 hectares [54]. Figure 4 illustrates the geographical location of the case study. The design employs modernist forms and composition while fully embodying traditional Chinese UA. The project comprises five rectangular paddy fields of similar dimensions [23]. Pathways divide each field into multiple smaller plots of identical shape, reflecting China’s land policy of “households owning their own plots” [55]. Simultaneously, diagonal pathways were incorporated to facilitate swift access while disrupting the regular layout, thereby injecting vitality into the site. Square platforms, encircled by grey stone benches, are positioned at the centre of each rice field group to provide functional spaces for work and rest. In ancient China, most people combined learning with farming [23]. This concept integrates traditional culture into contemporary life, imbuing the design with historical significance. As Turenscape (2018) explains, rice possesses extended landscape value due to its 200-day growth cycle [23]. Its changing colours throughout development stages also present diverse agricultural vistas. The project received an Honourable Mention from the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA) in 2005 [55]. A 2008 survey report indicated that 177 out of 197 respondents favoured the paddy field landscape, with 90% acknowledging its value. Furthermore, 75% of users expressed willingness to participate in cultivation and perceived the tranquil atmosphere of the paddies as conducive to relaxation [55].

Figure 4.

The geographical location of the Rice Field Landscape. The red dot indicates the project’s location.

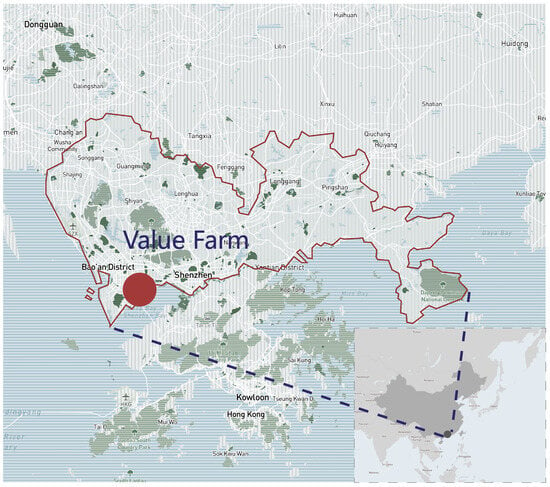

2.6.2. Value Farm

Shenzhen’s urban layout lacks a clearly defined city centre, meaning development across each district proceeds at a similar rapid pace. By 1980, having been designated a Special Economic Zone, Shenzhen had transformed from a fishing village into China’s third-largest economic city, attracting tens of thousands of workers to settle there. Shenzhen’s UA manifests in diverse forms. Its urban farming initiatives draw upon and integrate established domestic and international urban management and development methodologies, exemplified by the “pastoral complex at Dapeng zone”, vertical farm “Sky farm” and community farm “Sky farm”. The predominant form of UA in Shenzhen is tourism-oriented agricultural ventures. For example, the ‘Gitang Landscape’ is an eco-agricultural tourism project utilising coastal fish ponds [56]. Concurrently, as China’s high-tech hub, Shenzhen’s technologically advanced UA is increasingly becoming dominant. Furthermore, Shenzhen hosts socially impactful urban agricultural events such as the Lychee Trade Festival [57]. Regarding marketing, Shenzhen possesses a developed agricultural produce market network, having become China’s largest agricultural distribution centre and corporate trade base [57]. However, the Shenzhen government has not formulated explicit UA policies.

The Value Farm is situated in Shenzhen’s Shekou District. The project was developed on the reclaimed site of a former factory known as the Guangdong Glass Factory [58]. Covering 2100 m2, it was designed and established by Ole Bouman [58]. As a key exhibition piece for the Hong Kong-Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism Architecture 2013, it integrates urban vacant spaces and architecture, original industrial sites, and urban greening to create a regenerative landscape for the post-industrial era [58]. Figure 5 illustrates the geographical location of the case study. The project’s design philosophy draws inspiration from rooftop agriculture in densely populated cities and the transformation of original structures within historic urban centres [59]. At the same time, the basic form of the rooftop in the central Graham stress wet market which is 170 years old in Hong Kong made up the space of the project [59]. The initiative aims to rediscover nature within the urban fabric by integrating natural elements with Hong Kong’s historical context [59]. The project comprises three sections: cultivation zones, experiential areas, and exhibition spaces. These include rectangular planting beds of varying heights, a projection room, and a nursery. Brick walls, platforms, and open pavilions were designed within the existing stairwell area to enrich the site’s landscape [58]. Furthermore, irrigation ponds were installed alongside an irrigation system to enhance water resource utilisation.

Figure 5.

The geographical location of the Value Farm. The red dot indicates the project’s location.

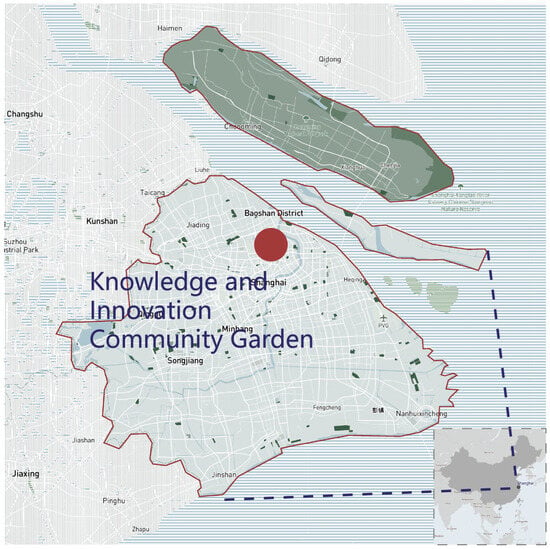

2.6.3. The Knowledge and Innovation Community Garden (KICG)

Shanghai’s urbanisation rate has reached 90%, establishing it as China’s economic hub [60]. Constrained by limited land resources, UA predominantly features typical and traditional small-scale practices [60,61]. Shanghai hosts China’s largest number of community gardens, reaching 74 in 2020—accounting for 17.83% of the nation’s total [9]. The municipal government prioritises UA, implementing numerous related policies and providing financial support. In 2005, the Shanghai government introduced the “Policy Option on Promoting Urban Agritourism in Shanghai” to regulate its development route [62]. In Shanghai government promulgated the “Ninth Five-Year plan for National Economy and Social Development of Shanghai and Outline of 2010 Longtime Goals” UA policy, which aims to develop multifunctional UA in Shanghai. It aims to enhance farmland irrigation facilities and provide subsidies to farmers [62]. Furthermore, Shanghai’s UA exhibits a trend towards multifunctional development, primarily focusing on cultivation while integrating social and ecological functions [62]. However, due to social marginalisation and low consumer trust, most farms operate on the brink of survival [63].

The Knowledge and Innovation Community Garden (KICG) is an urban agricultural community garden situated within the Knowledge and Innovation Community. Utilising interstitial urban spaces, it was established in 2016 and occupies an area of 2200 m2. In 2015, the Shanghai government promulgated the Implementation Measures for Urban Renewal in Shanghai. The area housing the Innovation Farm was designated for development within a key ecological axis. During the design phase, recognising the community’s lack of public and nature education spaces, the farm was assigned a public agricultural education function to enhance the community’s spatial capabilities. It stands as Shanghai’s first urban agricultural garden situated within an open block. Simultaneously, it serves as a demonstrative, educational, and social micro-urban agricultural garden. Figure 6 illustrates the geographical location of the case study. The KICG presents a narrow triangular layout. Centred within the farm is a communal activity pavilion, flanked by multifunctional cultivation zones including a facilities service area, public activity zone, permaculture area, community planting section, and one-metre vegetable plots. A winding path traverses all areas of the garden. The facilities service zone comprises a multi-purpose building, anaerobic kitchen waste composting bins, ecological flower beds, and rainwater collection tanks. The multi-purpose building, occupying approximately 100 m2, serves as the primary spatial hub designed to accommodate community public engagement activities. The public activity zone encompasses a 290-square-metre communal garden featuring an activity plaza and children’s play area. The permaculture area, spanning approximately 150 m2, primarily showcases sustainable cultivation design models. The public activity area covers 1531 m2, serving as the garden’s landscape focal point and aiming to enhance local plant genetic diversity. The one-metre vegetable plots comprise 40 wooden beds, each measuring one square metre. Functioning as allotments, it provides residents with practical opportunities for urban crop cultivation.

Figure 6.

The geographical location of the Knowledge and Innovation Community Garden. The red dot indicates the project’s location.

Among the three cities, Shenyang exhibits the most traditional development of its urban agricultural landscape. Supported by policy, it has achieved breakthroughs and optimisations in traditional UA. Leveraging its technological advantages, Shenzhen has experienced relatively rapid development in its urban agricultural landscape, accomplishing an innovative reconstruction from scratch. Shanghai demonstrates the most rapid advancement in UA, achieving an upgrade from existence to refinement. This progress benefits from Shanghai’s extensive market environment, abundant research resources, comprehensive policies, and ample funding.

3. Results

Table 3 presents the scores for each case study in each indicator. Table 4 presents the scores for each case study in production, ecology, management, and social dimensions. The KICG achieved the highest overall score (0.861112). This project also secured top marks across all three dimensions of UA: ecological, social and management. The scores for the Rice Field Landscape and the Value Farm were relatively close at 0.333069 and 0.120131, respectively. The Rice Field Landscape attained its highest score in the dimension of urban agricultural production. Below follows a detailed examination of the Rice Field Landscape, the Value Farm, and the KICG across the four dimensions of UA.

Table 3.

The scores for each case study in each indicator.

Table 4.

The scores for each case study in production, ecology, management, and social dimensions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Production Contribution

Production constitutes the prerequisite and foundation of UA projects. It influences site management models and aesthetic expression. This study analyses project production types, yields, and production cycles to comprehensively explore each case’s focus, characteristics, and distinctions within the production dimension.

The Rice Field Landscape cultivates rice exclusively. Their cultivation cycle spans three seasons. Moreover, as rice yields exceed those of other grain crops, it effectively alleviates urban food security concerns. According to Turenscape (2021), annual rice harvests yield approximately EUR 7000 worth of grain [24]. Quantitative analysis indicates that the Rice Field Landscape scores significantly higher than the other two case studies on the production dimension. This discrepancy aligns with qualitative analyses of yield and cultivation cycles. It demonstrates that explicit quantification models can intuitively reflect project differences at the production level. Simultaneously, it underscores the significance of yield metrics within the production dimension. The Value Farm and the KICG achieved comparable scores, both securing high ratings for production type and production cycle indicators. This stems from their cultivation of diverse edible plants and year-round production. The Value Farm primarily cultivates common crops, with winter wheat and flaxseed being the most extensively grown [59]. Root crops and common vegetables maturing across different seasons are selected to maximise land utilisation, such as carrots, cabbage, cauliflower, and Chinese kale [59]. Concurrently, colourful, uncooked edible greens like red oak leaf, green oak leaf, red rola, chicory, and endive are cultivated to promote the ‘farm-to-table’ concept of healthy eating [59]. Compared to the Value Farm, the KICG primarily cultivates diverse crops that foster interaction with people and animals, aligning with the garden concept. Both adopt crop rotation systems to maximise land use and achieve year-round production. The Value Farm uses plants’ varying maturation periods to create contrasting and complementary landscapes. The KICG aims to present continuous agricultural landscapes while maintaining soil fertility. However, their yield scores are relatively low. Due to their compact planting spaces and emphasis on urban agricultural recreation and demonstration functions, neither has a yield valuation. For instance, the KICG incorporates spiral gardens, keyhole gardens, strawberry towers, and banana circles to showcase diverse permaculture techniques.

Comparing the three models reveals that production requirements are closely tied to their design philosophies and planting areas. Yet whether projects prioritise food production or recreational education, they all consider the aesthetic qualities of edible plants while enhancing urban productive functions. This finding is corroborated by quantitative assessments, where the production dimension exhibits the smallest standard deviation. This indicates that while differences exist in edible crop yields, the projects generally converge in this aspect.

4.2. Ecological Contribution

Ecological enhancement constitutes a vital aspect of urban sustainability. This study evaluates each case’s ecological distinctiveness and commonality through three indicators: organic farming practices, sustainable methodologies, and species diversity.

The Rice Field Landscape and the KICG achieved high scores in the ecological dimension. This stems from their outstanding performance in promoting organic agricultural production and enhancing species diversity. The Value Farm received the lowest score due to its failure to clearly define organic cultivation practices. This demonstrates the quantitative model’s ability to accurately identify differences between projects in the ecological dimension. All projects scored on biodiversity and urban sustainability metrics, with the Rice Field Landscape and the KICG achieving higher marks. The Rice Field Landscape enhances micro-ecological cycles by reserving two sets of paddy fields for insects and animals, thereby improving habitats and providing food sources [24]. The KICG elevates regional biodiversity through the selection of edible plants. The project introduced over 50 native plant species and cultivated nectar-producing and host plants to furnish insects with sustenance and shelter. Regarding urban sustainability, the Rice Field Landscape used its cultivation environment and crop characteristics to achieve water resource recovery and circulation. Annually, the project can store 7200 cubic metres of water while utilising impurities as nutrients to purify rainwater [24]. Furthermore, the project regulates urban water usage. When rainwater is insufficient, the urban water supply system irrigates these fields. Excess rainfall exceeding 700 mm is discharged via the city’s drainage system [24]. The Value Farm approaches urban sustainability from the perspective of garden design and construction. The project utilises existing trees, pipes, scaffolding and decking, old broken walls, vintage circular wooden stools, and the original car park to create a new UA landscape [21,22,58]. This approach not only protects the local environment and preserves natural resources but also breathes new life into them. The KICG integrates approaches from both cases. It features designed ponds and rainwater collection tanks for water recycling, while repurposed shipping containers serve as structures and recycled materials form furniture. Organic agriculture is primarily evident in edible plant cultivation. As the Value Farm does not explicitly detail its planting process, it receives a lower score. Both the Rice Field Landscape and the KICG avoid pesticides and chemical fertilisers, utilising readily available organic waste for composting. The Rice Field Landscape utilises rice straw as compost material. Given its proximity to multiple cafés, the KICG produces compost by collecting coffee grounds, fallen leaves, and kitchen waste.

While the ecological advantages of edible plants are not fully realised due to the surrounding urban environment, all three initiatives contribute to urban ecological sustainability to varying degrees. Quantitative analysis further confirms that within the ecological dimension scoring, each indicator exhibits a significant correlation with the overall ecological score. Moreover, comparative analysis among the three models provides clearer evidence of UA’s contribution to sustainable urban development.

4.3. Management Systems

A sound and well-structured management system facilitates the orderly development of UA projects. This paper examines the management models and strengths of each case study from the perspectives of administrators, maintenance, and revenue generation.

Each project differs in its initiation, governing body, and maintenance requirements. The Rice Field Landscape was established and is managed by a non-profit educational institution, requiring no specialised upkeep. The Value Farm, part of the Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism Architecture, was initiated and managed by the government [21]. This project primarily functions as an exhibition space without dedicated maintenance personnel. The management system for the KICG is relatively complex. It is a government-initiated public space that achieves co-management by enterprises, social organisations, and residents, forming a regional co-governance model. Maintenance is jointly undertaken by enterprises, residents, and NGOs. Specifically, the Shanghai Clover Nature School handles the daily management of the KICG. Concurrently, the e Co-construction Society, a local non-profit organisation comprising part-time or full-time volunteers and residents, has been cultivated and developed. The Shui On Land, a property enterprise, assists in operations and annually provides Clover Nature School with CNY 500,000 in management funds to ensure the stable development of this public space. Furthermore, nearby residents voluntarily assist in managing the farm. In quantitative assessment results, the KICG achieved the highest overall score in the management dimension. This validates the strengths identified in qualitative analysis: multi-stakeholder collaboration and systematic maintenance and management.

Through quantitative model analysis, the management system’s score indirectly reflects the project’s managerial complexity. Clear and detailed division of management responsibilities better facilitates the project’s sustained accessibility and enhances public acceptance. Managers may select appropriate management approaches based on design principles, project objectives, and environmental factors.

4.4. Social Contribution

Addressing social issues presents a significant challenge for urban projects. This study analyses three indicators—organising activities, educational value, and alleviating social tensions—to identify strengths and weaknesses across cases in the social dimension.

Quantitative analysis indicates that the KICG achieved the highest score on the social level. This reflects its capacity to enhance the quality of life for disadvantaged groups. The KICG provides employment opportunities and organises weekend farm produce sales to increase income for agricultural producers and vulnerable communities. Regarding educational impact, both the Rice Field Landscape and the KICG scored relatively highly. The Rice Field Landscape hosts interactive activities enabling students to gain agricultural knowledge about planting and cultivating rice. Many students, originating from urban areas, have never engaged in farm work. Even without prior experience of cultivating crops, the Rice Field Landscape allows them to rediscover and reconnect with nature. Concurrently, the site is freely accessible for public visits. The KICG primarily offers participatory educational activities and courses for young people. For instance, its farming experience zone runs activities recording and observing rice growth to enhance understanding of crop development. The KICG also provides garden tours where staff explain the garden’s philosophy and the functions of each area. Due to its lack of educational activities, the Value Farm scored lowest on the social dimension. This demonstrates how quantitative models can validate the sensitivity and validity of social dimension metrics across projects. Furthermore, all three explicitly conduct social activities to foster resident interaction and enhance community cohesion. The Value Farm and the KICG achieve higher scores due to their diverse and abundant activities. Specifically, the KICG has become a venue for daily recreational pursuits. It regularly organises academic seminars, community garden festivals, and neighbourhood concerts to promote awareness of UA. The Rice Field Landscape management team hosts annual rice planting and harvest festivals in May and October [64]. The Value Farm facilitates cross-sectoral engagement through UA activities such as seed sowing and tasting events. Concurrently, the project offers ecological and regenerative solutions for post-industrial urban renewal. It integrates the city, people, and nature, mitigating conflicts between architecture and the natural environment while addressing urban food challenges.

Analysis of social contributions demonstrates that UA projects play a positive role in addressing societal issues. These initiatives provide residents with accessible recreational spaces while revitalising sites. Concurrently, they enhance community interaction, fostering social cohesion and harmony.

Qualitative and quantitative analysis across four dimensions indicates that the quantitative assessment model validates the reliability of qualitative findings, improves comparability between case studies, and visualises research outcomes. Firstly, quantitative assessment extends qualitative research by validating the conclusions drawn from qualitative analysis. Secondly, specific scores for each indicator reflect differences among projects in production, ecology, management, and social aspects. Furthermore, quantified metrics provide intuitive evidence for analysing the overall performance of UA projects.

5. Conclusions

This paper examines the crises confronting contemporary Chinese cities, the historical trajectory of UA in China, the development of UA in three representative cities, and three exemplary UA case studies. Following further analysis, the research examines the uniqueness and commonalities of each case study, using the distinctive conditions of specific urban environments as the starting point for discussion. Simultaneously, a quantitative evaluation system is employed to compare the cases, deepening understanding of the various dimensions of UA. By progressing from a macro-level overview of Chinese UA to detailed case analysis, this research clarifies the significance of Chinese UA and explores its value.

China’s longstanding urban agricultural practices constitute the foremost advantage for developing UA in Chinese cities. This tradition fosters active participation among residents. The study also identifies that urban agricultural initiatives in China predominantly originate from top-down policies, particularly government-led projects. Constraints to UA in China manifest in the absence of macro-level policies specifically addressing it, which hinders the scaling-up of urban agricultural practices and leads to disorderly development.

Furthermore, this study deepens understanding of the specific development and current status of UA across Chinese cities. All three cities emphasise the importance of actively developing urban tourism agriculture. By outlining the development directions of UA in these three cities, it demonstrates that the dominant types of UA in China are closely linked to each city’s unique strengths and geographical location. Shenyang emphasises the development of large-scale, traditional UA centred on grain crops. Its UA aims to meet local food reserves and achieve mass production. Shenzhen’s UA prioritises leveraging technological strengths to develop high-tech and innovative urban farming. Community gardens constitute Shanghai’s predominant UA model, directly linked to its high population density and scarcity of land resources.

By comparing exemplary urban agricultural practices in China, this paper demonstrates the value of Chinese UA in terms of production, management, and its social and ecological dimensions. Regarding production, Chinese UA case studies have innovated both the range of edible crops selected for urban cultivation and the methods employed. Not only does it enable the production of diverse crop varieties, but it also emulates rural agricultural cultivation methods, attempting the mass production of single-type agricultural crops. For instance, the success of the rice field landscape project demonstrates that urban areas can support single-crop cultivation, fostering broader recognition of UA’s diversity. These distinctive, multifaceted production models enhance urban planting spaces while offering fresh perspectives on urban farming approaches. Regarding management, China’s UA practices are undertaking bold experiments. Case studies demonstrate the viability of developing low-maintenance edible plants in urban settings, offering reference points for unattended urban agricultural models. Concurrently, China’s urban agricultural practices are being widely promoted through local and regional institutions and governments. These initiatives also validate the core guiding value of China’s top-down policies in fostering UA. Furthermore, diverse management approaches by different administrators reflect the varied governance styles within China’s urban agricultural practices. Ecologically, this study confirms that China’s urban agricultural practices can ameliorate urban ecological issues. Due to numerous factors, each case study emphasises different aspects of urban ecology. However, analysis clearly demonstrates that all cases play a positive role in enhancing urban sustainability and increasing biodiversity. Socially, the primary purpose of China’s UA practices is to provide residents with spaces for personal relaxation, learning, and recreation, with cost reduction being secondary. Simultaneously, this study demonstrates that China’s UA practices hold value in improving the social environment, alleviating social tensions, and fulfilling social responsibilities. Although the social value generated by each case differs, all enrich the lives of urban residents and promote the integration of cities, residents, and agriculture through diverse activities and formats such as garden tours, training programmes, and employment provision.

This paper provides researchers with comprehensive, multi-dimensional guidance on UA in China through a detailed exploration of the scale sequence encompassing national, city and case levels. However, the study retains certain limitations. Firstly, the breadth and applicability of the findings are somewhat constrained. The discussion is confined to selected Chinese cities and representative case studies, failing to encompass all regions of China. Consequently, it cannot fully reflect the diversity and distinctive characteristics of UA across the entire country. Secondly, the number and recency of referenced literature remain limited due to restricted access to certain sources and the inability to include all available databases. Furthermore, the study did not incorporate all relevant research outputs, resulting in an incomplete evaluation framework and indicator system. This has, to some extent, impacted the depth of the research. Future research will enhance the evaluation framework by diversifying literature and data acquisition methods and refining research methodologies. Furthermore, expanding the scope and number of case studies will improve the scientific rigour and depth of the investigation.

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, methodology, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X. and L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu, J.S. Urban Agriculture in China: An Empirical Study in Cosmopolitan Shanghai; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2002; ISBN 780167491X. [Google Scholar]

- Knoema. World Data Atlas. Available online: https://knoema.com/atlas/China (accessed on 15 May 2022).

- The World Bank. Urban Population. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL (accessed on 20 July 2022).

- National Bureau of Statistic. Urbanisation Levels Continue to Rise as Cities Advance Steadily Forward—Seventeenth in a Series of Reports on Economic and Social Development Achievements Marking the 70th Anniversary of the Founding of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://www.stats.gov.cn/sj/zxfb/202302/t20230203_1900425.html (accessed on 6 September 2019).

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs. Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs Releases 2024 Typical Cases of Agricultural Product Quality and Safety Supervision and Enforcement. Available online: https://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/zwdt/202501/t20250122_6469444.htm (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Addressing Water Scarcity: Water Conservation Is the Fundamental Solution. Available online: https://www.gov.cn/xinwen/jdzc/202403/content_6942239.htm (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- China Economic Network. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development: Plans to Select 50 More Cities Over the Next Three Years to Prioritize the Promotion of Reclaimed Water Utilization. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/cysc//stwm/sy/yw/202403/29/t20240329_38952663.shtml (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- China News Network. Two-Thirds of China’s 600-Plus Large and Medium-Sized Cities Are Besieged by Garbage. Available online: https://www.chinanews.com.cn/sh/2018/02-13/8447995.shtml (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Environmental Quality. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/ (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. 2014 Annual Report on Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control in Large and Medium-Sized Cities Nationwide. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/hjzl/sthjzk/gtfwwrfz/201912/P020191220697793463589.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. 2020 Annual Report on Solid Waste Pollution Prevention and Control in Large and Medium-Sized Cities Nationwide. Available online: https://www.mee.gov.cn/ywgz/gtfwyhxpgl/gtfw/202012/P020201228557295103367.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Junquera, R. Architecture, Ambiance et Agriculture Urbaine. Relations Historiques et Contemporaines Entre l’Habitat et l’Agriculture en Ville. Ph.D Thesis, Lyon National School of Architecture, Lyon, France, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Barrs, R. Sustainable Urban Food Production in the City of Vancouver: An Analytical and Strategy Framework for Planners and Decision-Makers. City Farmer Urban Agriculture Notes. Available online: http://www.cityfarmer.org/barrsUAvanc.html (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Holmes, D. Thammasat University–The Largest Urban Rooftop Farm in Asia. World Landscape Architecture. Available online: https://worldlandscapearchitect.com/thammasat-university-the-largest-urban-rooftop-farm-in-asia/?v=7efdfc94655a (accessed on 13 May 2024).

- The American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). Gary Comer Youth Center Roof Garden. Available online: https://climate.asla.org/GaryComerYouthCenterRoofGarden.html (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Walsh, L.E.; Mead, B.R.; Hardman, C.A.; Evans, D.; Liu, L.; Falagan, N.; Kourmpetli, S.; Davies, J. Potential of urban green spaces for supporting horticultural production: A national scale analysis. Environ. Res. Lett. 2022, 17, 014052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Yang, R. The Interaction and Its Evolution of the Urban Agricultural Multifunctionality and Carbon Effects in Guangzhou, China. Land 2022, 11, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Chan, F.K.S.; Li, G.; Xu, M.X.; Feng, M.L.; Zhu, Y.G. Implementing urban agriculture as nature-based solutions in China: Challenges and global lessons. Soil Environ. Health 2024, 2, 100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.L.; Yin, K.L.; Sun, Z.; Yu, H.; Mao, J.Y. Co-governed Landscapes: An Experiment Integrating Public Space Renewal and Social Governance in Shanghai Community Gardens. Archit. J. China 2022, 3, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.Y.; Sun, T.Y.; Liu, Y.L. Research on the Mechanism for Creating Inclusive Public Spaces Based on Co-governance Hubs: A Case Study of Shanghai Chuangzhi Farm. J. Guangxi Norm. Univ. 2023, 59, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temp. Value Factory, Shenzhen, China. Available online: https://tempinternational.com/en/stedenbouw/value-factory/ (accessed on 6 October 2025).

- Aroonwa. City Farm Shenzhen. Available online: https://thaicityfarm.com/2018/12/24/city-farm-shenzhen/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Turenscape. Rice Landscape. Available online: http://www.landscape.cn/landscape/action/ShowInfo.php?classid=3&id=9277 (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Turenscape. The Fragrance of Rice Fills the Campus. Cultivating Rice Is like Nurturing Students. Available online: https://www.turenscape.com/news/detail/2101.html (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Li, M.T.; Zhou, Z.X. Research on Multifunctional Development Models for Urban Agriculture Based on a Multidimensional Evaluation Model. Chin. J. Ecol. Agric. 2016, 24, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Liu, Z.C.; Liu, Y.X.; Hu, X.X.; Wang, A. Multifunctionality assessment of urban agriculture in Beijing City, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 537, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- John, H.; Artmann, M. Introducing an integrative evaluation framework for assessing the sustainability of different types of urban agriculture. Int. J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2024, 16, 35–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teitel-Payne, R.; Kuhns, J.; Nasr, J. Indicators for Urban Agriculture in Toronto: A Scoping Analysis. 2016. Available online: http://torontourbangrowers.org/img/upload/indicators.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gullino, P.; Battisti, L.; Larcher, F. Linking Multifunctionality and Sustainability for Valuing Peri-Urban Farming: A Case Study in the Turin Metropolitan Area (Italy). Sustainability 2018, 10, 1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fiore, G.; Specht, K.; Zanasi, C. Assessing motivations and perceptions of stakeholders in urban agriculture: A review and analytical framework. International J. Urban Sustain. Dev. 2021, 13, 351–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacchè, G.; Consalès, J.-N.; Grard, B.J.-P.; Daniel, A.-C.; Chenu, C. Toward an Evaluation of Cultural Ecosystem Services Delivered by Urban Micro-Farms. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, A.; Kale, S.; Chandel, S.; Pal, D.K. Likert scale: Explored and explained. Br. J. Appl. Sci. Technol. 2015, 7, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.; Yang, S.-W. Likert-Type Scale. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Sun, C.; Wang, M. Optimization Strategies for Waterfront Plant Landscapes in Traditional Villages: A Scenic Beauty Estimation–Entropy Weighting Method Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Huang, F.; Deng, X.; Jiang, W. A New Total Uncertainty Measure from A Perspective of Maximum Entropy Requirement. Entropy 2021, 23, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. The Construction of the Landscape- and Village-Integrated Green Governance System Based on the Entropy Method: A Study from China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.B.; Zhang, Y.; Yuan, K.G.; Zhao, H.L. Analysis on characteristics and comprehensive evaluation of county’s development level in the Xiangjiang River basin. Econ. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1088–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, D.Y.; Shen, J.H.; Lu, Y.Q. Spatial coupling between transportation superiority and economy in central plain economic zone. Econ. Geogr. 2012, 32, 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- Cerreta, M.; Poli, G. Landscape Services Assessment: A Hybrid Multi-Criteria Spatial Decision Support System (MC-SDSS). Sustainability 2017, 9, 1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röling, W.; van Timmeren, A. Introducing Urban Agriculture Related Concepts in the Built Environment: The park of the 21st century. In Proceedings of the 2005 World Sustainable Building Conference, Tokyo, Japan, 27–29 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.Q. A History of Traditional Chinese Gardens; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 1999; ISBN 9787302080794. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J. History of Chinese and Foreign Garden Design; Huazhong University of Science and Technology Press: Wuhan, China, 2009; ISBN 9787560950280. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C.A. Research on Agro-Integrated Community in Urban Area. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.S. Productive Landscape Used in the Design of Urban Green Space. Ph.D. Thesis, Donghua University, Shanghai, China, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party. 1956–1967 National Agricultural Development Outline. People’s Daily. 1957. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/shuju/1956/gwyb195605.pdf (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- Chen, J.Y. From Greening to Landscaping. People’s Daily, 18 November 1958. Available online: https://cn.govopendata.com/renminribao/1958/11/18/8/#209659 (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Beijing Zhongshan Park Management Office Gardening Class. Combining Gardens with Production is promising. Archit. J. 1974, 6, 30–33+55–56. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=dzw7IdLhHkHoccnaqy1JTpwPN_drnDCNOjmD64RufJHjezPrYhdracHA0mkZD7jmS1H4b8PbWjLM2vIyaQ_4CudVsI5Qlh474_xH7pXrdqRDe1cv5riHWm7ttwiZrWYvWrLVLS20ESGEuP5A3JhlfT7zsrAZ6uzZOp1BwEgnz3t50tpPn26DaA==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Ding, X.Y. The Research of Chinese Community Garden. Ph.D. Thesis, Tianjin University, Tianjin, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Liu, Y.; Huang, G. Current Status and Development Strategy for Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA) in China. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xihua Park’s “One-Meter Vegetable Garden” Gains Popularity Among Residents Home Gardening Expected to Gain Wider Adoption. Available online: https://www.kunming.cn/news/c/2018-04-03/5037804.shtml (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Peng, S.N.; Zhou, C.; Zhou, Y.X. Building and Analyzing Participant Social Networks in Child-Friendly Community Development: A Case Study of the “Children’s Farm” Initiative at Yucai No. 3 Primary School in Changsha, Hunan Province. Landsc. Archit. J. 2020, 8, 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- Planning Department-The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Planning for Recreational and Community Farming in Hong Kong. Planning Department. 2016. Available online: https://www.pland.gov.hk/file/planning_studies/comp_s/hk2030plus/TC/document/Planning%20for%20Recreational%20and%20Community%20Farming%20in%20Hong%20Kong_Chi.pdf (accessed on 14 March 2024).

- Shenyang Government. Shenyang Urban Modern Agriculture Development Planning Outline 2013–2017. Shenyang Daily. Available online: https://www.shenyang.gov.cn/zwgk/zcwj/zfwj/szfbgtwj1/202112/t20211201_1698925.html (accessed on 16 May 2024).

- Yu, K.J.; Han, Y.; Han, X.Y. Let the sound of reading dissolved in the fragrance of rice—Campus landscape design of Shenyang Architectural University. Chin. Landsc. Archit. 2005, 5, 12–16.75. Available online: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms2/article/abstract?v=RPbSoBw3VsGo2rFmfZ3BQoLvP8QGa5zLldtbpFnA3N1rpkUSN8LPWFgWJQ-f9xr4EFcbpbWNmvOtGB2TzMojuEQy_irgu-KMwTDWplGpzGR9hUhUhmhwGhQZCUPXVmXMoQ1cnpHZt2xdppjQgIfjQzQEi1crCwNnUpZ6ptHLgZ9m-Kqp85BVIg==&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 29 November 2025).

- Turenscape. Shenyang Architectural University Campus-Rice Landscape. Available online: https://www.turenscape.com/project/detail/324.html (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Shenzhen Sea Garden. Available online: https://www.szwaterlands.com/szhstyly/hsty/parkProfile.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Chen, C. The Strategy Research of Developing Urban Agriculture in Shenzhen. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, T. Value Farm. ArchDaily. Available online: https://www.archdaily.com/477405/value-farm-thomas-chung (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Chun, T. Value Farm. Divisare. Available online: https://divisare.com/projects/296157-thomas-chung-value-farm (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Hosseinifarhangi, M.; Turvani, M.E.; van der Valk, A.; Carsjens, G.J. Technology-driven transition in urban food production practices: A case study of Shanghai. Sustainability 2019, 11, 6070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozak, A.E. Envisioning a Self-Sustaining City: The Practice and Paradigm of Urban Farming in Shanghai. Master’s Thesis, University of Colorado at Denver, Denver, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, C.X. Research on the Sustainable Development of Urban Agriculture in Shanghai. Ph.D. Thesis, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, D.; Liu, P.; Ravenscroft, N. The new urban agricultural geography of Shanghai. Geoforum 2018, 90, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenyang Architectural University. Shenyang Jianzhu University Campus Cultural Landscape: Rice Fields. Available online: https://ln.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202105/23/WS60aa32c2a3101e7ce97511a9.html (accessed on 21 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).