Assessing Urban Flood Risk and Identifying Critical Zones in Xiamen Island Based on Supply–Demand Matching

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

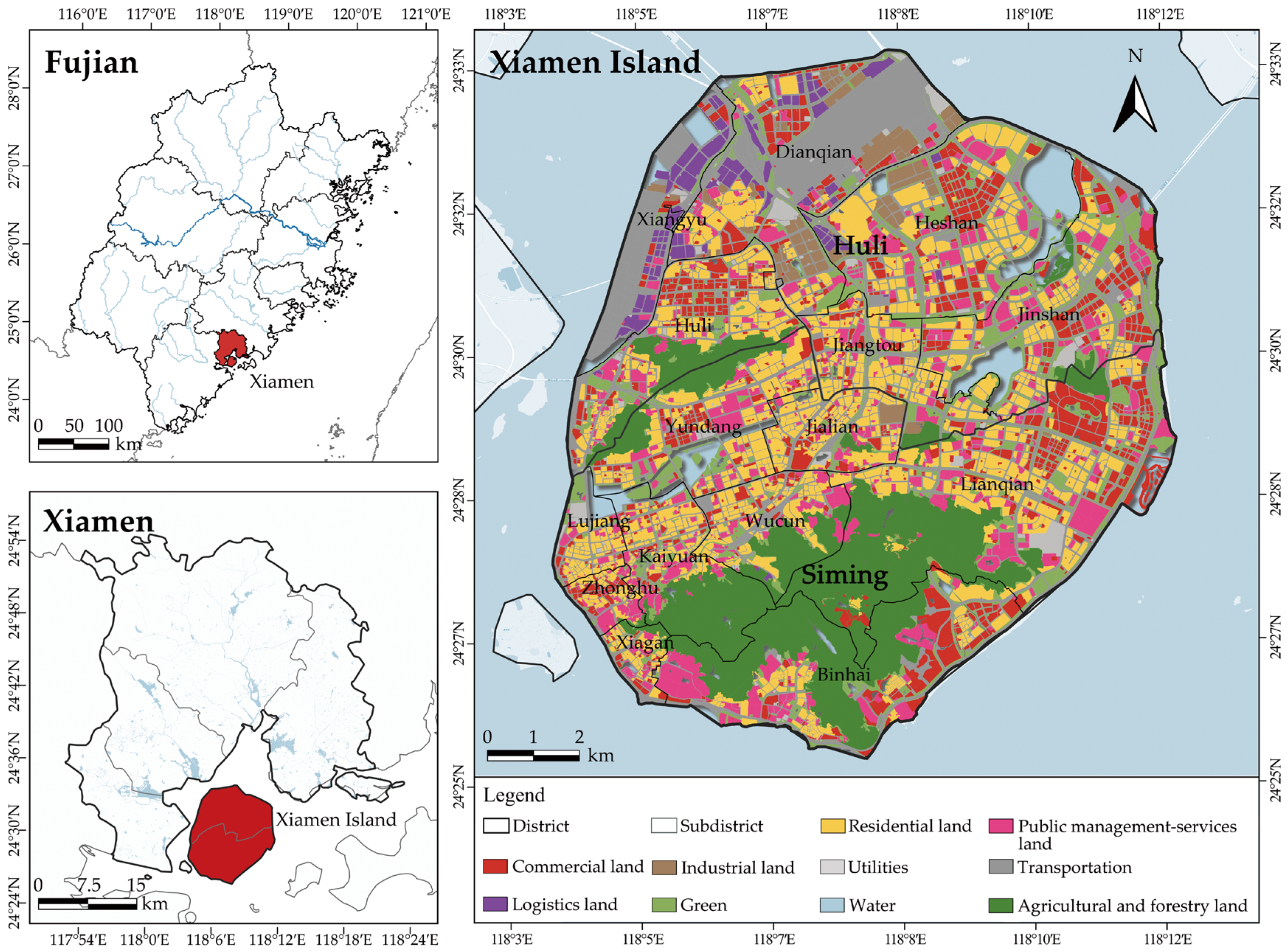

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Data Sources

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Research Framework

2.3.2. Selection and Calculation of FRS Supply Indicators

- (1)

- Water retention. The Water Yield module, based on the Budyko water-balance principle, computes precipitation retention and infiltration, along with soil–water storage, to determine the study area’s Water Yield. The module’s governing equation is as follows:where Yxj represents the Water Yield supplied by LULC type j on parcel x; AETxj is the actual evapotranspiration of the parcel, x; and Px denotes the precipitation on parcel x.

- (2)

- Soil retention. The Sediment Delivery Ratio module, based on the Universal Soil Loss Equation (USLE), calculates the potential soil erosion and the actual soil erosion for each grid cell; the difference between these represents soil retention. The module equation is as follows:where R is rainfall erosivity, K is soil erodibility, L is the slope-length factor, S is the slope-steepness factor, C is the cover-management factor, and P is the support-practice factor.

- (3)

- Nutrient retention. The Nutrient Delivery Ratio module is based on the mechanism by which vegetation and soils in ecosystems reduce or remove nitrogen and phosphorus pollutants in river runoff through storage or transformation. The lower the surface export of TN and TP, the stronger the water-purification capacity and the lower the pollution risk posed by floods. The module equation is as follows:where ALVx is the adjusted loading value of grid cell x, HSSx is the hydrologic sensitivity score of grid cell x, and polx is the export coefficient of grid cell x.

2.3.3. Selection and Calculation of FRS Demand Indicators

- (1)

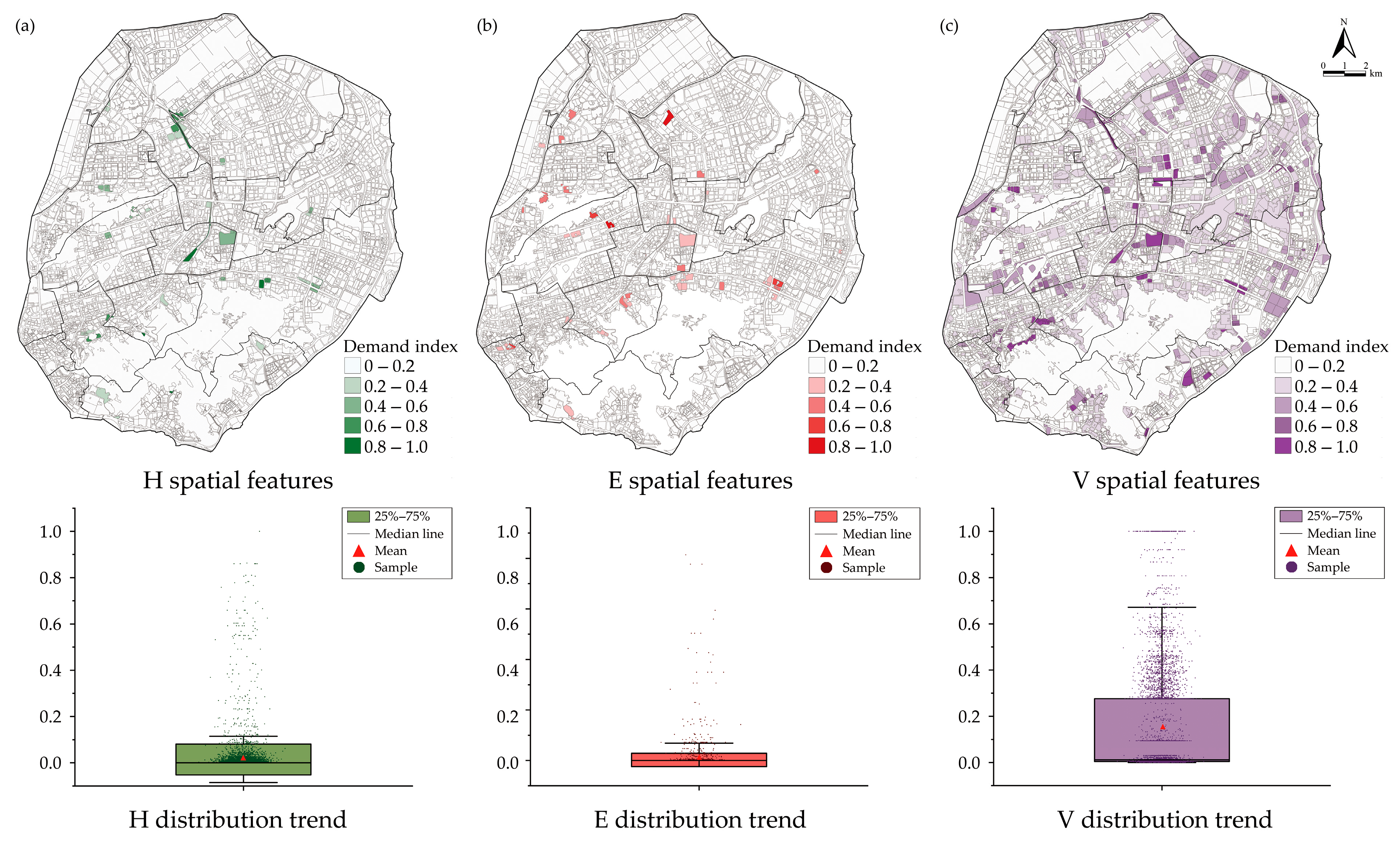

- Hazard. The flood physical characteristics in this study were obtained using the InfoWorks ICM model under a 50-year return-period rainfall scenario (in Supplement Section S1). This study selects maximum inundation depth [44] and inundation duration [45] and defines the hazard index as follows:where H is the hazard index, Dmax is the maximum inundation depth (m) experienced by each parcel unit, and Tinu is the inundation duration (h).

- (2)

- Exposure. This study selects population, medical facilities, government agencies, and social organizations as the elements at risk and counts the number of such elements within each parcel [46]. According to the GB 51222—2017 Technical Code for Urban Waterlogging Prevention [47], a ponding depth exceeding 0.15 m is considered urban waterlogging. Based on inundation depth, five classes are defined: 0–0.15 m, 0.15–0.30 m, 0.30–0.45 m, 0.45–0.60 m, and >0.60 m [48]. Depth-weighting is used to capture the differential impacts across inundation classes, with weights assigned from low to high as 0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1. The calculation formula is as follows [49]:where E is the exposure index; Pi is the number of affected people of category i within the parcel; Fj is the number of affected facilities of category j within the parcel (medical facilities, government agencies, and social organizations); Wi and Wj are the weights corresponding to the inundation-depth class, and n and m are the numbers of population and facility categories, respectively.

- (3)

- Vulnerability. Vulnerability is assessed along two dimensions—structural damage to buildings and indoor property and economic losses [50]—using widely applied water depth–damage ratio curves [51], locally calibrated and adjusted to the study area. The calculation formula [52] is as follows:where Vs. is the structural damage ratio of buildings, Vi is the indoor property damage ratio of buildings, and x is the depth of waterlogging. The product of structural vulnerability and indoor property vulnerability constitutes the vulnerability index V. For different land-use types, the indoor property damage ratio is determined by substituting the corresponding inundation depth (in Supplement Section S2).

2.3.4. Supply-Demand Calculation

- (1)

- Supply calculation

- (2)

- Demand calculation

2.3.5. FRS Supply–Demand Matching

2.3.6. Coupling-Coordination Degree Evaluation

2.3.7. Spatial Priority Method for Planning Intervention

3. Results

3.1. Results of Supply and Demand Indicators

3.1.1. Results of Supply Indicators

3.1.2. Results of Demand Indicators

3.1.3. Spatial Distribution and Clustering Characteristics of Supply–Demand

3.2. Results of Supply–Demand Matching and Coupling–Coordination

3.2.1. Results of Supply–Demand Matching

3.2.2. Supply–Demand Coupling–Coordination Degree

3.3. Spatial Prioritization of Planning Interventions

4. Discussion

4.1. Advantages of the Research Method

4.2. FRS Supply-Demand Risk Assessment and Policy Recommendations

4.3. Limitations and Prospects

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FRS | Flood regulation services |

| LULC | Land use and land cover |

| WR | Water retention |

| SR | Soil retention |

| NR | Nutrient retention |

| H–E–V | Hazard–exposure–vulnerability |

| PRI | Priority Index |

| CCDM | Coupling–coordination degree model |

References

- Liang, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, G.; Xie, Z. Evaluation Framework ACR-UFDR for Urban Form Disaster Resilience under Rainstorm and Flood Scenarios: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 107, 105424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Meteorological Organization (WMO). WMO Atlas of Mortality and Economic Losses from Weather, Climate and Water Extremes (1970–2019); World Meteorological Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021; ISBN 978-92-63-11267-5. [Google Scholar]

- Willner, S.N.; Otto, C.; Levermann, A. Global Economic Response to River Floods. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 594–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, J.; Krebs, P. Investigating Flood Exposure-Induced Socioeconomic Risk and Mitigation Strategy under Climate Change and Urbanization at a City Scale. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 387, 135929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhu, L.; Xie, Z.; Lian, J.; Yuan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Bai, S.; Xu, T.; Zhou, H.; Xu, F. Resilience Evolution of Urban Sub-Districts to Flooding: An Analytical Framework Considering Internal Disaster Dynamics. Urban Clim. 2025, 63, 102572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Fang, L.; Chen, J.; Ding, T. A Novel Framework for Urban Flood Resilience Assessment at the Urban Agglomeration Scale. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 108, 104519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, W.V.; Mooney, H.A.; Cropper, A.; Capistrano, D.; Carpenter, S.R.; Chopra, K.; Dasgupta, P.; Dietz, T.; Duraiappah, A.K.; Hassan, R. Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.; He, C.; Huang, Q.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, K.; Lutz, A.; Merz, B. Growing Imbalance between Supply and Demand for Flood Regulation Service in the Asian Water Tower and Its Downstream Region. Earth’s Future 2025, 13, e2025EF006338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Pacetti, T.; Brandimarte, L.; Santolini, R.; Caporali, E. A Methodology for Assessing Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Flood Regulating Services. Ecol. Indic. 2021, 129, 107963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; He, C.; Huang, Q.; Li, L. Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Flood Regulation Service under the Joint Impacts of Climate Change and Urbanization: A Case Study in the Baiyangdian Lake Basin, China. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 158, 111318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorilla, R.S.; Kalogirou, S.; Poirazidis, K.; Kefalas, G. Identifying Spatial Mismatches between the Supply and Demand of Ecosystem Services to Achieve a Sustainable Management Regime in the Ionian Islands (Western Greece). Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Tian, J.; Zeng, J.; Pilla, F. Assessing the Spatial Pattern of Supply–Demand Mismatches in Ecosystem Flood Regulation Service: A Case Study in Xiamen. Appl. Geogr. 2023, 160, 103113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, J.; Zheng, H.; Hou, Y.; Fu, Q.; Chen, C.; Yuan, L.; Lv, B.; Liu, S.; Huang, Y.; et al. Quantifying Realized Ecosystem Services from the Supply-Flow-Demand Perspective and Understanding the Management Implications: A Case Study of the Chengdu Prefecture, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 181, 114337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürck, J.; Poortinga, A.; Verburg, P.H. Mapping Ecosystem Services: The Supply and Demand of Flood Regulation Services in Europe. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 38, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Zeng, S.; Zeng, J.; Jiang, F. Assessment of Supply and Demand of Regional Flood Regulation Ecosystem Services and Zoning Management in Response to Flood Disasters: A Case Study of Fujian Delta. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czúcz, B.; Sonderegger, G.; Condé, S. Ecosystem Service Fact Sheet on Flood Regulation. ETC/BD Report to the EEA. 2018. Available online: https://www.eionet.europa.eu/etcs/etc-bd/products/etc-bd-reports/etc-bd-report-12-2018-fact-sheets-on-ecosystem-condition (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Liu, W.; Feng, Q.; Zhang, X.; Engel, B.A. Evaluating Supply and Demand Relationship of Urban Flood Regulation Service and Identifying Priority Areas for Green Infrastructure Implementation in Urban Functional Zones. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 126, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Yan, Y.; Zeng, S. Intelligent Identification and Management of Flood Risk Areas in High-Density Blocks from the Perspective of Flood Regulation Supply and Demand Matching. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Tao, J.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Shi, S.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, H. SWAT-Based Analysis of Flood Regulation Service Dynamics in the Pearl River Basin (2006–2018): Mechanisms from Hydrological Modelling to Flood Events. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 532, 146958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadaverugu, A.; Rao, C.N.; Viswanadh, G.K. Quantification of Flood Mitigation Services by Urban Green Spaces Using InVEST Model: A Case Study of Hyderabad City, India. Model. Earth Syst. Environ. 2021, 7, 589–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Du, S.; Huang, Q.; Yin, J.; Zhang, M.; Wen, J.; Gao, J. Mapping the City-Scale Supply and Demand of Ecosystem Flood Regulation Services—A Case Study in Shanghai. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 106, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vári, Á.; Kozma, Z.; Pataki, B.; Jolánkai, Z.; Kardos, M.; Decsi, B.; Pinke, Z.; Jolánkai, G.; Pásztor, L.; Condé, S.; et al. Disentangling the Ecosystem Service “Flood Regulation”: Mechanisms and Relevant Ecosystem Condition Characteristics. Ambio 2022, 51, 1855–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhao, C.; Yang, L.; Huang, D.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, P. Spatial and Temporal Evolution Analysis of Ecological Security Pattern in Hubei Province Based on Ecosystem Service Supply and Demand Analysis. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 162, 112051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.S.; Kašanin-Grubin, M.; Kapović Solomun, M.; Sushkova, S.; Minkina, T.; Zhao, W.; Kalantari, Z. Wetlands as Nature-Based Solutions for Water Management in Different Environments. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 33, 100476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines-Young, R.; Potschin, M. The Links between Biodiversity, Ecosystem Services and Human Well-Being. Ecosyst. Ecol. A New Synth. 2010, 1, 110–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Luo, Y.; Zheng, L.; Yan, Y. Novel Framework for Identifying Priority Areas in Ecological Restoration: Integrating Ecosystem Service Flows. Ecol. Front. 2025, 45, 1258–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Situ, Z.; Zhong, Q.; Zhang, J.; Teng, S.; Zhao, Z.; Ge, X.; Zhou, Q. Attention-Based Deep Learning Framework for Urban Flood Damage and Risk Assessment with Improved Flood Prediction and Land Use Segmentation. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2024, 116, 105165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Xu, X.; Yang, W.; Li, Y.; Yao, S. Supply-Demand Risk Assessment of Urban Flood Resilience from the Perspective of the Ecosystem Services: A Case Study in Nanjing, China. Ecol. Indic. 2025, 173, 113397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Dong, X.; Xie, M.; Wang, Y.; Tong, D.E. Zoning for Urban Space Governance Based on the Disaster Vulnerability and Supply-Demand Match of Ecosystem Services. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 6012–6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, E.; Rahman, A.; Rainis, R.; Seri, N.; Fuzi, N. The Impacts of Land Use Changes in Urban Hydrology, Runoff and Flooding: A Review. Curr. Urban Stud. 2023, 11, 120–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecemiş Kılıç, S.; Efe Güney, M.; Ayhan Selçuk, İ.; Alğın Demir, K.; Gür, G. An Example of Vulnerability Analysis According to Disasters: Neighborhoods in the Southern Region of Izmir. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Sheng, M.; Yang, D.; Tang, L. Evaluating Flood Regulation Ecosystem Services under Climate, Vegetation and Reservoir Influences. Ecol. Indic. 2019, 107, 105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolen, B.; Van Gelder, P.H.A.J.M. Risk-Based Decision-Making for Evacuation in Case of Imminent Threat of Flooding. Water 2018, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.-S.; Wu, K.-J.; Ho, H.-C. Assessment of Subsystem Interactions and Coupling Coordination in Flood Resilience Evaluation: Comparative Analysis and Policy Recommendations. Urban Clim. 2025, 64, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, F.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.; Qin, K. Coupling Coordination Degree Spatial Analysis and Driving Factor between Socio-Economic and Eco-Environment in Northern China. Ecol. Indic. 2022, 135, 108555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.J.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y.B. Exploring the Relationship between Urbanization and the Eco-Environment—A Case Study of Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei Region. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, E.; Zhang, H. Examining the Coupling Relationship between Urbanization and Natural Disasters: A Case Study of the Pearl River Delta, China. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2021, 55, 102057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xue, Y.; Liang, J.; Tan, S. Research on the Coupling and Coordination of Urbanization and Flood Disasters Based on an Improved Coupling Coordination Model: A Case Study from the Pearl River Delta in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-R. Urban Rainstorm Flood Risk Assessment Integrating Machine Learning and Remote Sensing: A Case Study of Xiamen City. In Chinese Society for Urban Studies, Proceedings of the 2024 China Urban Planning Annual Conference (02: Urban Safety and Disaster Prevention Planning), Hangzhou, China, 5–8 July 2024; Hefei Municipal People’s Government, Beautiful China, Co-Construction, Co-Governance and Sharing, Ed.; Jiangsu Urban Planning and Design Institute Co., Ltd.: Zhenjiang, China, 2024; pp. 12–26, (In Chinese). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Statistics. Xiamen Special Economic Zone Yearbook. Available online: https://tjj.xm.gov.cn/ (accessed on 25 November 2025). (In Chinese)

- Xiamen Municipal People’s Government. Xiamen Drainage (Rainwater) and Waterlogging Prevention Special Plan (2020–2035); Xiamen Municipal People’s Government: Xiamen, China, 2020. (In Chinese)

- Huang, W.; Hashimoto, S.; Yoshida, T.; Saito, O.; Taki, K. A Nature-Based Approach to Mitigate Flood Risk and Improve Ecosystem Services in Shiga, Japan. Ecosyst. Serv. 2021, 50, 101309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.; Hou, H.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, P.; Hu, T. Future Urban Waterlogging Simulation Based on LULC Forecast Model: A Case Study in Haining City, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 87, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Baldassarre, G.; Kreibich, H.; Vorogushyn, S.; Castellarin, A.; Sieg, T.; Schröter, K. A New Framework for Flood Damage Assessment Considering the within-Event Time Evolution of Hazard, Exposure, and Vulnerability. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maranzoni, A.; D’Oria, M.; Rizzo, C. Quantitative Flood Hazard Assessment Methods: A Review. J. Flood Risk Manag. 2023, 16, e12855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 51222-2017; Technical Code for Urban Waterlogging Prevention. China Planning Press: Beijing, China, 2017. (In Chinese)

- Zhou, J.; Shen, J.; Zang, K.; Shi, X.; Du, Y.; Šilhák, P. Spatio-Temporal Visualization Method for Urban Waterlogging Warning Based on Dynamic Grading. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Xu, S.; Shi, C.; Sun, A.; Zhao, Q. Risk Assessment of Rainstorm Waterlogging for Residential Buildings in the Central Urban Area of Shanghai Based on Scenario Simulation. J. Nat. Disasters 2011, 20, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Ding, Y. Spatial Coupling Analysis of Urban Waterlogging Depth and Value Based on Land Use: Case Study of Beijing. Water 2025, 17, 529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emergency Management Australia. Disaster Loss Assessment Guidelines; Paragon Printer Australasia Pty Ltd.: Sydney, Australia, 2002; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Xin, R.H.; Zeng, J.; Li, K.; Wang, Q.W.; Ding, S.Y. Identify Key Areas and Priority Levels of Urban Waterlogging Regulation Service Supply and Demand. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 500–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Huang, G.; Chen, Z. Evaluation of Urban Flood Adaptability Based on the InVEST Model and GIS: A Case Study of New York City, USA. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 11063–11082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, L.; Xu, K.; Pan, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Shen, R. Urban Flood Risk Assessment Characterizing the Relationship among Hazard, Exposure, and Vulnerability. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 86463–86477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Li, J.; Ma, Q. Integrating Green Infrastructure, Ecosystem Services and Nature-Based Solutions for Urban Sustainability: A Comprehensive Literature Review. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2023, 98, 104843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, B.; Xia, J.; Wang, X. Comprehensive Flood Risk Assessment in Highly Developed Urban Areas. J. Hydrol. 2025, 648, 132391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.-C.; Chang, Y.-T.; Chang, Y.-S. A Multi-Factor Flood Resilience Index for Guiding Disaster Mitigation in Densely Populated Region. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2025, 120, 105387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larondelle, N.; Lauf, S. Balancing Demand and Supply of Multiple Urban Ecosystem Services on Different Spatial Scales. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 22, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, A.S.; Wang, G.; Fu, G. Exploring the Relationship between Urban Flood Risk and Resilience at a High-Resolution Grid Cell Scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 893, 164852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.; Lu, Y.; Sun, N. Street Community-Level Urban Flood Risk Assessment Based on Numerical Simulation. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Q.; Yu, T.; Engel, B.A. Analyzing the Impacts of Topographic Factors and Land Cover Characteristics on Waterlogging Events in Urban Functional Zones. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 904, 166669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, S.; Wang, H.; Hu, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hu, S. Mixed-Use Urban Land Parcels Identification Using Multi-Source Data: A Case Study of Guangzhou, China. J. Urban Technol. 2024, 28, 1743–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Lin, Z.; VanLooy, J.; Kennedy, A. Strategic Land Acquisition for Efficient and Equitable Flood Risk Reduction in the United States. Clim. Risk Manag. 2023, 42, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Mohammad Yusoff, W.F.; Mohamed, M.F.; Jiao, S.; Dai, Y. Flood Economic Vulnerability and Risk Assessment at the Urban Mesoscale Based on Land Use: A Case Study in Changsha, China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 351, 119798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.K.; Peng, Z.W.; Wang, Y.C. Mapping of Flood Regulation Service Demand and Identifying of Priority Settings of Ecological Spaces in Rapidly Urbanized Area Based on Ecosystem Service Spatial Flow. Landsc. Archit. 2022, 38, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhai, T.L.; Lin, Y.F.; Long, X.S.; He, T. Spatial Imbalance and Changes in Supply and Demand of Ecosystem Services in China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertilsson, L.; Wiklund, K.; De Moura Tebaldi, I.; Rezende, O.M.; Veról, A.P.; Miguez, M.G. Urban Flood Resilience: A Multi-Criteria Index to Integrate Flood Resilience into Urban Planning. J. Hydrol. 2019, 573, 970–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Hallema, D.; Asbjornsen, H. Ecohydrological Processes and Ecosystem Services in the Anthropocene: A Review. Ecol. Process. 2017, 6, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zou, L.; Xia, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, F.; Zuo, L. A Multi-Dimensional Framework for Improving Flood Risk Assessment: Application in the Han River Basin, China. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2023, 47, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Li, J.; Zhou, K.; Feng, P.; Dong, L. The Effects of Surface Pollution on Urban River Water Quality under Rainfall Events in Wuqing District, Tianjin, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 293, 126136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, H.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J. Urban Flooding Simulation and Flood Risk Assessment Based on the InfoWorks ICM Model: A Case Study of the Urban Inland Rivers in Zhengzhou, China. Water Sci. Technol. 2024, 90, 1338–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chai, Z.; Guo, X.; Shi, B. A Lattice Boltzmann Model for the Viscous Shallow Water Equations with Source Terms. J. Hydrol. 2021, 598, 126428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DB3502/Z 047-2018; Standard of Rainstorm Intensity Formula and Design Rainstorm Profile. Xiamen Municipal Standardization Guiding Technical Document. Xiamen Municipal Bureau of Quality and Technical Supervision: Xiamen, China, 2018. (In Chinese)

- Liu, J.; Shao, W.; Xiang, C.; Mei, C.; Li, Z. Uncertainties of urban flood modeling: Influence of parameters for different underlying surfaces. Environ. Res. 2020, 182, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Data Type | Data Name | Category | Resolution | Unit | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land use and land cover | LULC | Vector | / | m | Xiamen municipal bureau of natural resources and planning (https://zygh.xm.gov.cn/). |

| Natural environment | DEM | Grid | 12.5 m | m | Geospatial aata cloud platform (https://www.gscloud.cn/). |

| Slope | Grid | 12.5 m | ° | DEM-based extraction. | |

| Precipitation/evapotranspiration | Grid | 30 m | mm | CMADS dataset (https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/en/, accessed on 1 November 2025). | |

| Soil | Grid | 30 m | / | World soil database (https://www.fao.org/home/en, accessed on 1 November 2025). | |

| Root restriction layer depth | Grid | 30 m | m | ||

| Plant available water content | Grid | 30 m | % | ||

| Socioeconomics | GDP | Grid | 30 m | Yuan/km2 | Xiamen statistical yearbook (2020) (https://tjj.xm.gov.cn/); AMAP POI open data. |

| Population density | Grid | 30 m | Per | ||

| /km2 | |||||

| POI | Vector | / | / | ||

| Building | Vector | / | Piece | ||

| Hydrology and hydraulics | Drainage pipe network | Vector | / | m | Xiamen municipal bureau of agriculture and rural affairs; Xiamen city drainage (Rainwater) flood control master plan (2020–2035) (https://sn.xm.gov.cn/) [41]. |

| Hydrological parameters | Float | / | / | ||

| Historical flood area | Vector | / | Piece | ||

| Contour line | Vector | / | Piece |

| Subdistrict Name | Low Supply- Low Demand | Low Supply- Low Demand | High Supply- Low Demand | High Supply- High Demand | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area (km2) | P (%) | Area (km2) | P (%) | Area (km2) | P (%) | Area (km2) | P (%) | |

| Binhai | 4.094 | 2.86 | 9.093 | 6.35 | 1.584 | 1.11 | 1.022 | 0.71 |

| Heshan | 8.388 | 5.85 | 2.365 | 1.65 | 0.714 | 0.50 | 4.888 | 3.41 |

| Zhonghua | 0.348 | 0.24 | 0.748 | 0.52 | 0.414 | 0.29 | 0.015 | 0.01 |

| Dianqian | 11.686 | 8.16 | 2.820 | 1.97 | 0.898 | 0.63 | 2.114 | 1.48 |

| Lianqian | 5.994 | 4.18 | 13.929 | 9.72 | 3.063 | 2.14 | 2.231 | 1.56 |

| Jinshan | 3.699 | 2.58 | 4.299 | 3.00 | 5.299 | 3.70 | 0.819 | 0.57 |

| Huli | 2.679 | 1.87 | 4.858 | 3.39 | 1.791 | 1.25 | 0.051 | 0.04 |

| Jiangtou | 4.052 | 2.83 | 0.327 | 0.23 | 0.385 | 0.27 | 1.400 | 0.98 |

| Jialian | 3.441 | 2.40 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 1.135 | 0.79 |

| Kaiyuan | 2.350 | 1.64 | 3.591 | 2.51 | 0.541 | 0.38 | 0.529 | 0.37 |

| Yundang | 3.895 | 2.72 | 3.607 | 2.52 | 0.951 | 0.66 | 1.043 | 0.73 |

| Xiangyu | 1.277 | 0.89 | 4.526 | 3.16 | 0.325 | 0.23 | 0.007 | 0.00 |

| Xiagang | 0.425 | 0.30 | 0.895 | 0.62 | 0.285 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 0.00 |

| Wucun | 2.563 | 1.79 | 1.715 | 1.20 | 0.016 | 0.01 | 1.628 | 1.14 |

| Lujiang | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.000 | 0.00 | 0.021 | 0.01 |

| Total | 56.114 | 39.17 | 53.090 | 37.06 | 17.011 | 11.87 | 17.054 | 11.90 |

| Classification of Coupling Types | Classification of Coupling–Coordination Degree | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coupling Degree C* Value | Coupling Type | Coupling–Coordination Degree D* Value | Coupling–Coordination Type |

| C* ∈ [0, 0.55] | Low coupling | D* ∈ [0, 0.20] | Seriously discoordination |

| C* ∈ (0.55, 0.77] | Medium-low coupling | D* ∈ (0.20, 0.40] | Slightly discoordination |

| C* ∈ (0.77, 0.85] | Medium coupling | D* ∈ (0.40, 0.60] | Basically coordinated |

| C* ∈ (0.85, 0.90] | Medium-high coupling | D* ∈ (0.60, 0.80] | Well-coordinated |

| C* ∈ (0.90, 1.00] | High coupling | D* ∈ (0.80, 1.00] | Highly coordinated |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cheng, L.; Li, G.; Liu, G.; Zheng, Z. Assessing Urban Flood Risk and Identifying Critical Zones in Xiamen Island Based on Supply–Demand Matching. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410927

Cheng L, Li G, Liu G, Zheng Z. Assessing Urban Flood Risk and Identifying Critical Zones in Xiamen Island Based on Supply–Demand Matching. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410927

Chicago/Turabian StyleCheng, Lin, Guotao Li, Gong Liu, and Zhi Zheng. 2025. "Assessing Urban Flood Risk and Identifying Critical Zones in Xiamen Island Based on Supply–Demand Matching" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410927

APA StyleCheng, L., Li, G., Liu, G., & Zheng, Z. (2025). Assessing Urban Flood Risk and Identifying Critical Zones in Xiamen Island Based on Supply–Demand Matching. Sustainability, 17(24), 10927. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410927