Conservation Agriculture as a Pathway to Climate and Economic Resilience for Farmers in the Republic of Moldova

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Majority orientation towards vegetable crops—viticulture, fruit growing and cereal crops (wheat, corn, barley, sunflower, rapeseed). Vines and orchards are identity crops, with an important role in export.

- Dependence on climatic conditions—frequent droughts and uneven distribution of rainfall significantly influence production; irrigation is limited and underused in many areas.

- Fragmented land structure—after privatization in the 1990s, agricultural lands are dispersed and small, which limits the application of modern technologies. At the same time, in the last 25 years, farmers have invested considerable money in land consolidation (especially their acquisition), which has meant minimizing costs for technology and competitiveness, and this phenomenon has influenced the vulnerability of farms in the short term.

- Relatively low productivity compared to the pedoclimatic potential—chernozem soils are highly fertile, but the technological level, mechanization, and access to modern inputs remain the main problems.

- Major role of agriculture in the economy and employment—agriculture contributes to GDP and employs a significant part of the rural population.

- Agricultural dualism—small subsistence farms (with production intended for self-consumption or local markets) and medium/large commercial farms, oriented towards export, coexist.

- Recent trends—there is an increase in interest in organic farming and conservation-sustainable systems (minimization of soil work, crop rotation, precision agriculture), as well as for integration into value chains.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Framework and Data Sources

- ✓

- Actual yield and cost data reported by 25 representative farms (10 conventional and 15 conservation farms) cultivating wheat, barley, maize, rapeseed, and sunflower;

- ✓

- Market price averages derived from regional trade statistics;

- ✓

- Input costs (fuel, seeds, fertilizers, rent, and mechanized services) obtained from local cooperatives and supplier records.

2.2. Methodological Approach

- Conventional agriculture (CAc)—characterized by deep tillage, residue removal, and intensive mechanical operations;

- Conservation agriculture (CA)—a system applied by a small but growing group of farmers practicing minimal soil disturbance, residue retention, and crop rotation.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of Crop Structure in the Republic of Moldova

3.2. Comparative Performance of Conventional and Conservation Systems

- Minimal Soil Disturbance. Cultivation should be performed through direct seeding or similar methods that minimize mechanical interference with the soil structure. The disturbed area must not exceed 15 cm in width or 25% of the total cropped surface.

- Permanent Organic Soil Cover. Maintaining continuous soil cover through crop residues, cover crops, or other organic materials is essential for protecting the soil from erosion, regulating temperature and moisture, and sustaining biological activity. Technologies that ensure less than 30% soil coverage do not qualify as conservation agriculture.

- Crop and Species Diversification. Crop rotation should involve at least three different species, including cereals, legumes, and oilseeds, to improve soil fertility, reduce pest and disease pressure, and stabilize yields over time.

- Insufficient Applied Research and Implementation. Applied research on conservation agriculture remains limited and insufficiently integrated into national agricultural practices. This gap is particularly concerning given the intensifying effects of climate change and the continuing degradation of soil quality.

- Lack of Comparative Scientific Evidence. There is a notable absence of long-term, evidence-based studies comparing conservation and conventional farming systems, particularly in relation to agrotechnical and soil quality indicators. Current promotion of CA relies predominantly on farmers’ empirical experiences and field observations rather than on rigorous scientific validation.

- Growing Interest among Farmers. Farmers’ interest in CA has increased in response to recurrent droughts (notably during 2022–2025) and the economic pressures generated by high input costs and reduced market prices linked to the war in Ukraine. Farmers practicing no-tillage methods report more stable yields under drought conditions compared to conventional producers.

- Limited Adoption and Farm Scale. Approximately 50–70 farmers—typically those managing over 300 hectares—are currently applying or transitioning to CA practices. Only about half of them fully adhere to the three core CA principles: direct seeding, permanent soil cover through cover crops, and diversified crop rotations (e.g., wheat, maize, sunflower, and legumes).

- Economic Incentives and Carbon Market Participation. Around 50% of successful CA adopters have accessed payments from carbon sequestration schemes, averaging €32/ha. In some cases, these funds, supplemented by national subsidies (MAFI/AIPA), covered the initial investment costs for specialized equipment.

- Widespread Minimum Tillage Practices. Minimum tillage systems are widely practiced, particularly for winter cereals such as wheat and barley, with adoption rates of 70–80%. This has stimulated a local market for minimum tillage equipment supplied by agricultural machinery dealers.

- Economic Motivation and Agronomic Reluctance. The transition to CA is largely economically driven, aimed at increasing farm competitiveness. Interestingly, some large farms have reported dismissing conventional agronomists due to resistance toward conservation practices rooted in traditional university training.

- Informal Knowledge Networks. Social media platforms (Telegram, Viber, and YouTube) serve as the primary channels for technical knowledge exchange on CA, with Ukrainian farmer communities being the most influential sources of information. A Community of Practice supported by FAO has been established in Moldova, though farmer engagement remains modest but increasing.

- Educational and Institutional Gaps. Agricultural education and research institutions continue to emphasize conventional tillage systems. Universities and research centers generally lack the necessary direct seeding equipment to test, demonstrate, and promote CA technologies.

3.3. Cost Structure Analysis

- 1.

- Agrotechnical Considerations in Conservation Agriculture

- Field Leveling: Proper land leveling is essential before introducing CA, especially when using large direct seeders.

- Weed Control: Effective pre-implementation weed management is crucial. Perennial weeds must be eliminated before transitioning to CA. Weed control remains intensive during the first three years, after which pressure decreases as permanent soil cover becomes established. Glyphosate-based herbicides are commonly used before or at sowing time.

- Fertilization: Moldovan farmers generally maintain similar or slightly lower fertilizer inputs under CA compared to conventional systems.

- 2.

- Seasonal Crop Management

- Spring Crops:No-tillage implementation is generally easier in spring (April–May) due to higher soil moisture levels from winter precipitation, facilitating precise seed placement. However, the presence of surface mulch can delay germination and early growth, particularly for maize, sorghum, sunflower, and soybean. This delay results from lower soil temperatures beneath the organic cover, especially pronounced in dark Moldovan chernozems. To mitigate this effect, successful farmers:

- ✓

- Delay sowing until optimal soil temperatures (≥9 °C for maize) are reached;

- ✓

- Choose hybrids with shorter growing cycles to avoid late-season drought stress;

- ✓

- Accept minor delays in physiological maturity and grain drying compared to conventional systems.

- Winter Crops:For winter wheat, barley, rapeseed, and peas, sowing occurs in drier, harder soils (September–October), requiring robust and well-adapted direct seeders—often larger than conventional ones. Nonetheless, winter cereals provide abundant vegetative residues, forming a protective mulch after the first crop cycle, which accelerates the establishment of CA benefits.

- 3.

- Crop Performance Over Time

- Year 1–2:Many successful CA farmers maintain or even increase production levels within the first two years, particularly in dry seasons, while substantially reducing input and operational costs.

- Year 3—Managing Soil Compaction:Soil compaction emerges as a critical challenge during the third year of transition, primarily due to the passage of heavy machinery (e.g., sprayers and combines). The following strategies are essential for prevention and mitigation:

- ✓

- Adherence to direct seeding only, avoiding minimum tillage, which disrupts the mulch layer and resets the biological soil processes;

- ✓

- Use of cover crops (even in drier southern regions), leveraging residual soil moisture to enhance organic matter and biological activity;

- ✓

- Integration of leguminous species and Daikon radish as biological soil conditioners that improve structure, enhance drainage, recycle nutrients, and add up to 20 kg N/ha;

- ✓

- Adoption of technological innovations, such as drones for targeted pesticide applications, and dual tractor wheels to reduce soil pressure and compaction.

- 4.

- Emerging Challenges

- Rodent Infestation: The permanent organic cover fosters favorable habitats for rodents. Local mitigation strategies include enhancing natural predator populations through agroforestry and the strategic placement of bone residues to attract raptors.

- Livestock Interference: Grazing by sheep and goats on residue-covered fields can locally compact soil, hindering the performance of direct seeders and affecting early crop development.

4. Discussion

4.1. Profitability Trends and Barriers to Adoption of Conservation Agriculture in the Republic of Moldova

- Sufficient Down Pressure: Minimum 200 kg per opener (250 kg for double-disk openers) to ensure uniform seeding depth and proper fertilizer incorporation under no-tillage conditions.

- Flexible Seeding Units: Openers mounted on trapezoidal supports with shock absorbers allowing at least 20 cm vertical movement to follow surface irregularities and maintain consistent soil contact.

- Residue-Cutting Capability: Large coulter disks to efficiently slice through crop residues and ensure precise seed placement.

- Single-Disk Coulters: Preferred for minimal soil disturbance and superior residue management compared to double-disk systems.

- Versatility for Multiple Crops: Seed drills are adaptable for small (alfalfa, vetch, rapeseed), medium (wheat, barley), and large seeds (corn, sunflower, soybeans). Adjustments can be made by disabling rows or modifying spacing (e.g., 70 cm for large-seed crops).

- Simultaneous Cover Crop Sowing: The capacity to sow cover crop mixes or intercrop legumes with main crops to enhance soil fertility.

- GPS Precision Guidance: Ensures accurate row alignment, minimizes overlaps, and reduces post-harvest losses.

- 4- to 6-row double-disk drills priced between USD 20,000 and 35,000;

- Adjustable row spacing (40–70 cm) for diverse crops (alfalfa, cereals, maize, sunflower);

- Essential focus on adequate opener weight and vertical flexibility to ensure uniform sowing depth under varying soil conditions.

- Expanding access to affordable no-tillage equipment through cooperative ownership or rental schemes;

- Strengthening extension services and practical farmer training;

- Adapting national subsidy frameworks to reward long-term soil health outcomes;

- Integrating CA competencies into agronomic education and research programs.

4.2. Comparison with International Evidence

- The conservation agriculture system is seen as a strategic one by the Government of the Republic of Moldova and the relevant ministries, but there is a practical lack of instruments, a complex legal framework for facilitation, research and innovation, and adequate promotion for its practical implementation, with the exception of improving the subsidy system in agriculture, which is delayed until 2023.

- Conservation agriculture in the Republic of Moldova is implemented by people who practice agricultural activities without agricultural education (it is a paradox and a reality that is difficult to explain). Agriculture is a rather complex business, and state programs and subsidies must be oriented towards farmers who have at least three years of agricultural education in order to face all the challenges and accommodations to current and future climate changes. Agronomists are much more conservative and reluctant to adopt conservation agriculture because they were trained and applied only conventional agriculture and practically do not want to change the existing “comfort”.

- The agricultural education system is crucial for the correct training of specialists in the field of conservation agriculture. Importantly, the complexity and effectiveness of correct/efficient/practical training (demonstrative with demonstration plots/teaching stations) is necessary to create, because it is missing, and this fact causes all the remaining uncertainties/problems in large-scale culture.

- Direct costs in conservation agriculture (especially diesel consumption of 32–40 L/ha by reducing the number of mechanical operations and soil cultivation) is optimized, reduced, and in the fight against weed management, more total herbicides are used at the beginning.

- The development of conservation agriculture is based on the enthusiasm of the farmer who decided to implement no-tillage, but there is an acute lack of all components that must facilitate and inform beneficiaries: practical/applicative information, lack of state projects and complex research in the field of conservation agriculture, lack of practicing specialists in the field, dispersion and limitation of extension and knowledge transfer services.

- Farmers who switched to conservation agriculture in the first years of the transaction do not have lower results (crop yields) than in conventional agriculture, but they are the same and even sometimes higher, which excludes the perception that low results are recorded in the first 5 years of conversion, which was promoted by the academic environment, and recommends the gradual transition to conservation agriculture by farmers (which is not correct).

- Sowing of spring crops in conservation agriculture is a little later; the start of plant development is much slower from the beginning compared to conventional agriculture, but in the period of July–August, development is much more uniform (without stressing the plant), and finally the vegetation is longer, which ensures guaranteed harvests (in conventional agriculture it can be totally compromised). The harvesting process is much later, and this can be a risk in case of autumn rains (but this phenomenon is increasingly rare, and we practically have dry autumns under climate change conditions).

- The lack of efficient and systematic dialog between all actors who could facilitate and promote the development of the conservation agriculture system, and this causes all the incompetence and risks in this sector.

4.3. Institutional and Behavioral Barriers

- Creating a network of practical consultants (ToT) in the field of conservation agriculture to reconcile, promote, and consult on the conservation agriculture system and correctly inform interested farmers [43].

- Creation and development of tools/platforms and thematic events for practical discussion of the conservation agriculture system and intensification of dialog to identify operational development solutions [44].

- Conducting an economic study of practicing conservation agriculture compared to conventional agriculture to properly inform all the positive and negative aspects and facilitate reasoned decisions for undecided farmers or those practicing to adjust their business [45].

- It is necessary to create field schools (practical demonstration plots) for farmers based on model enterprises (perhaps initially three schools, at least in the central, northern, and southern areas), where complex and adjusted training with results/information over time can be organized for a production cycle and for training over time [46].

- Applying conservation agriculture on small areas is more expensive; it is very difficult to procure small-capacity conservation agricultural equipment (especially for 80–100 horsepower tractors that small farmers are equipped with); and the cooperation of small farmers to benefit from mechanized services at optimal costs would be a sustainable solution [47].

- The administration/donors would do well to identify and equip agro-industrial colleges and the Technical University to equip teaching stations with direct seeders (correctly selected and no-tillage), which will apply conservation agriculture, research, and educate/train the final beneficiaries (quite an important aspect) [48]. Creating farmer groups and equipping them with direct seeders will not have the expected effect of replication and education of farmers.

- Improving the legal framework that would facilitate the development of the conservation agriculture system with a clear stipulation of the soil management method, due to which until now sustainable soil cultivation has been neglected by most farmers, although they all benefit from subsidies, and the quality of the soil as a national wealth degrades from year to year as a result of the conventional agricultural system.

- The Ministry of Agriculture and Food Industry and donors interested in the promotion and development of conservation agriculture must join efforts to facilitate the unified and complex development of this way of conservation agricultural development; the implementation of separate projects will not cause the expected effects.

- Improving agricultural education—agronomic education for the field of no-tillage, as it is focused only on theory and less on practical and applied aspects [49]. Explore the possibility of supporting agricultural technical institutes and universities in developing informative materials on how no-till generates benefits, from an agronomic perspective, and study programs for agricultural technical institutes and universities.

- Exploring the opportunity to provide strategic support for the development of a national program to expand conservation agriculture within the framework of the government’s program to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (carbon sequestration) [50].

- Explore the opportunity of offering direct seeding services for farmers interested in setting up an experiment in conservation agriculture (perhaps through agricultural machinery suppliers). Provide small equipment that allows comparative measurements of farm results, which would allow building new arguments and convincing farmers.

5. Conclusions

- Limited availability of direct seeding equipment, which constrains farmers’ ability to experiment with no-tillage systems;

- Insufficient capacity to maintain permanent organic soil cover, crucial for preventing soil compaction;

- An inadequate subsidy framework, which does not sufficiently incentivize long-term sustainable practices;

- Institutional rigidity among agronomists and conventional tillage advocates, impeding innovation and knowledge transfer.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Petrea, Ș.-M.; Cristea, D.S.; Turek Rahoveanu, M.M.; Zamfir, C.G.; Turek Rahoveanu, A.; Zugravu, G.A.; Nancu, D. Perspectives of the Moldavian Agricultural Sector by Using a Custom-Developed Analytical Framework. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank; CIAT. Climate-Smart Agriculture in Moldova. CSA Country Profiles for Africa, Asia, Europe and Latin America and the Caribbean Series; The World Bank Group: Washington DC, USA, 2016; Available online: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2019-06/CSA%20Moldova.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- FAO. AGROVOC Country Report—Republic of Moldova, 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/agrovoc/agrovoc-country-report-republic-moldova-0 (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Gheorghiță, M.; Gheorghiță, M.; Stratila, A.; Gumeniuc, I. Transformation of Moldova’s Agricultural Sector: New Challenges and Investment Opportunities. In Competitiveness and Sustainable Development; Technical University of Moldova, Faculty of Economic Engineering and Business: Chișinău, Moldova, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerbari, V.; Leah, T.; Ţăranu, M. Soils of Moldova in Different Historical Periods and Possibilities to Restore their Quality Status. Sci. Papers Ser. A Agron. 2015, 58, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Steponavičienė, V.; Rudinskienė, A.; Žiuraitis, G.; Bogužas, V. The Impact of Tillage and Crop Residue Incorporation Systems on Agrophysical Soil Properties. Plants 2023, 12, 3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, E.; Szlatenyi, D.; Csenki, S.; Alrwashdeh, J.; Czako, I.; Láng, V. Farming Practice Variability and Its Implications for Soil Health in Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakpo, S.S.; Aostacioaei, T.G.; Mihu, G.-D.; Molocea, C.-C.; Ghelbere, C.; Ursu, A.; Țopa, D.C. Long-Term Effect of Tillage Practices on Soil Physical Properties and Winter Wheat Yield in North-East Romania. Agriculture 2025, 15, 989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug, D.; Yog, I.; Brozović, B.; Seremešić, S.; Dolijanović, Ž.; Zsembeli, J.; Ujj, A.; Marjanovic, J.; Smutny, V.; Dušková, S.; et al. Conservation Soil Tillage: Bridging Science and Farmer Expectations—An Overview from Southern to Northern Europe. Agriculture 2025, 15, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Reif, A.; Vidican, R.; Stoian, V.; Gärtner, S.M.; Allen, R.B. Impact of Climate on Vegetation Change in a Mountain Grassland—Succession and Fluctuation. Not. Bot. Horti. Agrobot. 2014, 42, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaida, I.; Păcurar, F.; Rotar, I.; Tomos, L.; Stoian, V. Changes in Diversity Due to Long-Term Management in a High Natural Value Grassland. Plants 2021, 10, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadjadi, E.N.; Fernández, R. Challenges and Opportunities of Agriculture Digitalization in Spain. Agronomy 2023, 13, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hou, H.; Liao, Z.; Wang, L. Digital Environment, Digital Literacy, and Farmers’ Entrepreneurial Behavior: A Discussion on Bridging the Digital Divide. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Sun, Y. Practices, Challenges, and Future of Digital Transformation in Smallholder Agriculture: Insights from a Literature Review. Agriculture 2024, 14, 2193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rurac, M.; Zbancă, A.; Baltag, G.; Bacean, I.; Cazmalî, N.; Bostan, M. Conservation Agriculture—Indispensable Solution for Soil Conservation and Adaptation to Climate Change; Brochure, Ed.; Tipografia Prin-Caro: Chișinău, Moldova, 2021; Available online: https://www.ucipifad.md/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/brosura_Agricultura-conservativ%C4%83-%E2%80%93-solu%C8%9Bie-indispensabil%C4%83_2021.pdf (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Statistical Data Bank. National Bureau of Statistics of the Republic of Moldova. Available online: https://statbank.statistica.md (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Bojariu, R.; Nedealcov, M.; Boincean, B.; Bejan, I.; Rurac, M.; Pintea, M.; Caisin, L.; Cerempei, V.; Hurmuzachi, I.; Baltag, G.; et al. Guide to Good Practices in Adapting to Climate Change and Implementing Climate Change Mitigation Measures Climate Change in the Agricultural Sector; “Print-Caro” Printing House: Chișinău, Moldova, 2021; 120p. [Google Scholar]

- Rurac, M.; Zbancă, A.; Baltag, G.; Bacean, I.; Cazmalî, N.; Bostan, M. Practical Guide in the Field of Conservation Agriculture; Guide, “Print-Caro” Printing House: Chișinău, Moldova, 2021; 87p, ISBN 978-9975-56-860-9. Available online: https://repository.utm.md/handle/5014/29031?show=full (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Sadiq, F.K.; Anyebe, O.; Tanko, F.; Abdulkadir, A.; Manono, B.O.; Matsika, T.A.; Abubakar, F.; Bello, S.K. Conservation Agriculture for Sustainable Soil Health Management: A Review of Impacts, Benefits and Future Directions. Soil. Syst. 2025, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbancă, A.; Panuța, S.; Morei, V.; Stratan, A.; Litvin, A.; Fala, I. Budgeting of Activities in the Vegetable Sector of the Republic of Moldova; Guide; UASM: Chișinău, Moldova, 2017; 350p, ISBN 978-9975-64-147-0. [Google Scholar]

- Zbancă, A.; Negritu, G.; Șcerbacov, E. Analysis of the competitiveness of the cereals sector in the context of organizational and legal forms of farm management for the 2023–2024 season. In Proceedings of the “Competitiveness and Sustainable Development” Conference—5, Technical University of Moldova, Chisinau, Moldova, 2–3 November 2023; pp. 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zbancă, A.; Balan, I. Considerations regarding the current state and development prospects of the cereal sector. In Materials of the International Scientific Conference “Universitas Europa: Towards a Knowledge Society Through Europeanization and Globalization”; ULIM: Chișinău, Moldova, 2023; pp. 101–106. ISBN 978-9975-3603-7-1. [Google Scholar]

- Zbancă, A.; Balan, I.; Negritur, G. Management of income and expenditure budgets for agricultural crops in the 2023–2024 agricultural season in the Republic of Moldova. In Fiscal Monitor; FISC.MD: Chișinău, Moldova, 2023; Volume 4, pp. 52–57. ISSN -1857-3991. Available online: https://monitorul.fisc.md/gestiunea-bugetelor-de-venituri-si-cheltuieli-pentru-culturi-agricole-in-sezonul-agricol-2023-2024-in-rm/ (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Favre, R. The Experience of No-till Conservation Agriculture of Successful Farmers in Moldova. In FAO Rapid Assessment Report; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Jităreanu, G.; Ailincăi, C.; Alda, S.; Bogdan, I.; Ciontu, C.; Manea, D.; Penescu, A.; Rurac, M.; Rusu, T.; Țopa, D.; et al. Agrotechnical Treatise; Ion Ionescu Publishing House from Brad: Iași, Romania, 2020; p. 1240. ISBN 978-973-147-353-6. [Google Scholar]

- Martikainen, A.A. Assessing the Resilience of Farming Systems: Insights from the Common Agricultural Policy and Polish Fruit and Vegetable Farming Challenges. Agriculture 2025, 15, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, H.; Xie, F.; Wu, D. Climate Change and Sustainable Agriculture: Assessment of Climate Change Impact on Agricultural Resilience. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cárceles Rodríguez, B.; Durán-Zuazo, V.H.; Soriano Rodríguez, M.; García-Tejero, I.F.; Gálvez Ruiz, B.; Cuadros Tavira, S. Conservation Agriculture as a Sustainable System for Soil Health: A Review. Soil. Syst. 2022, 6, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Futa, B.; Gmitrowicz-Iwan, J.; Skersienė, A.; Šlepetienė, A.; Parašotas, I. Innovative Soil Management Strategies for Sustainable Agriculture. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheţan, F.; Rusu, T.; Cheţan, C.; Urdă, C.; Rezi, R.; Şimon, A.; Bogdan, I. Influence of Soil Tillage Systems on the Yield and Weeds Infestation in the Soybean Crop. Land 2022, 11, 1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth, E.; Magyar, M.; Cseresnyés, I.; Dencső, M.; Laborczi, A.; Szatmári, G.; Koós, S. Climate-Smart Agricultural Practices—Strategies to Conserve and Increase Soil Carbon in Hungary. Land 2025, 14, 1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mupangwa, W.; Yahaya, R.; Tadesse, E.; Ncube, B.; Mutenje, M.; Chipindu, L.; Mhlanga, B.; Kassa, A. Crop Productivity, Nutritional and Economic Benefits of No-Till Systems in Smallholder Farms of Ethiopia. Agronomy 2023, 13, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Yi, C. Effects of Conservation Tillage on Agricultural Green Total Factor Productivity in Black Soil Region: Evidence from Heilongjiang Province, China. Land 2024, 13, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambon, I.; Cecchini, M.; Mosconi, E.M.; Colantoni, A. Revolutionizing Towards Sustainable Agricultural Systems: The Role of Energy. Energies 2019, 12, 3659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boros, A.; Szólik, E.; Desalegn, G.; Tőzsér, D. A Systematic Review of Opportunities and Limitations of Innovative Practices in Sustainable Agriculture. Agronomy 2025, 15, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olarewaju, O.O.; Fawole, O.A.; Baiyegunhi, L.J.S.; Mabhaudhi, T. Integrating Sustainable Agricultural Practices to Enhance Climate Resilience and Food Security in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multidisciplinary Perspective. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Țopa, D.-C.; Căpşună, S.; Calistru, A.-E.; Ailincăi, C. Sustainable Practices for Enhancing Soil Health and Crop Quality in Modern Agriculture: A Review. Agriculture 2025, 15, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, B.; Kienzle, J. Sustainable Agricultural Mechanization for Smallholders: What Is It and How Can We Implement It? Agriculture 2017, 7, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belay, S.A.; Assefa, T.T.; Yimam, A.Y.; Prasad, P.V.V.; Reyes, M.R. The Cradles of Adoption: Perspectives from Conservation Agriculture in Ethiopia. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisés, C.; Arrobas, M.; Tsitos, D.; Pinho, D.; Rezende, R.F.; Rodrigues, M.Â. Regenerative Agriculture: Insights and Challenges in Farmer Adoption. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerempei, V.; Țiței, V.; Vlăduț, V.; Moiceanu, G. A Comparative Study on the Characteristics of Seeds and Phytomass of New High-Potential Fodder and Energy Crops. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varyvoda, Y.; Thomson, A.; Bruno, J. Factors Influencing the Adoption of Sustainable Agricultural Practices in the US: A Social Science Literature Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landers, J.N.; de Freitas, P.L.; de Oliveira, M.C.; da Silva Neto, S.P.; Ralisch, R.; Kueneman, E.A. Next Steps for Conservation Agriculture. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petraki, D.; Gazoulis, I.; Kokkini, M.; Danaskos, M.; Kanatas, P.; Rekkas, A.; Travlos, I. Digital Tools and Decision Support Systems in Agroecology: Benefits, Challenges, and Practical Implementations. Agronomy 2025, 15, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Panja, A.; Panda, M.; Dutta, S.; Dutta, S.; Kumar, R.; Kumar, D.; Yadav, M.R.; Minkina, T.; Kalinitchenko, V.P.; et al. How Did Research on Conservation Agriculture Evolve over the Years? A Bibliometric Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mgendi, G.; Mao, S.; Qiao, F. Is a Training Program Sufficient to Improve the Smallholder Farmers’ Productivity in Africa? Empirical Evidence from a Chinese Agricultural Technology Demonstration Center in Tanzania. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, B.; Kienzle, J. Mechanization of Conservation Agriculture for Smallholders: Issues and Options for Sustainable Intensification. Environments 2015, 2, 139–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Li, C.; Ding, H.; Li, C.; Tang, Q.; Liu, M.; Hou, J. The Development of No-Tillage Seeding Technology for Conservation Tillage—A Review. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Qi, J.; Kan, Z. Sustainable Management and Tillage Practice in Agriculture. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Vázquez, J.; Carbonell-Bojollo, R.M.; Veroz-González, Ó.; Maraschi da Silva Piletti, L.M.; Márquez-García, F.; Cabeza-Ramírez, L.J.; González-Sánchez, E.J. Global Trends in Conservation Agriculture and Climate Change Research: A Bibliometric Analysis. Agronomy 2025, 15, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specification | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant Households (Farmer | Individual Households | Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant Households (farmers) | Individual Households | Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant Households (Farmers) | Individual Households | Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant Households (Farmers) | Individual Households | Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant (Farm) Households | Individual Households | |

| Surfaces—total, thousand ha | 1537.6 | 827.2 | 418.1 | 292.3 | 1557.5 | 846.7 | 418.2 | 292.6 | 1580.5 | 864.4 | 427.9 | 288.2 | 1596 | 879.6 | 422.6 | 293.8 | 1569.1 | 889.1 | 387.1 | 292.8 |

| Cereal and legume crops | 957.1 | 480.2 | 269.1 | 207.8 | 971.1 | 495.8 | 262 | 213.3 | 953 | 481 | 262.7 | 209.3 | 969.7 | 496.5 | 260.6 | 212.6 | 946.1 | 507.2 | 225.7 | 213.2 |

| Wheat | 311.4 | 229.2 | 80.2 | 2 | 341.7 | 257 | 82.8 | 1.9 | 332.0 | 250.5 | 80.6 | 0.9 | 377.0 | 284.6 | 91.1 | 1.3 | 369.2 | 284.5 | 83.2 | 1.5 |

| Barley | 54.3 | 39.4 | 13 | 1.9 | 65.5 | 48 | 15.7 | 1.8 | 54.8 | 41.3 | 12.4 | 1.1 | 60.2 | 46.2 | 12.8 | 1.2 | 64.6 | 47.9 | 14.9 | 1.8 |

| Corn kernels | 546.4 | 192 | 168.2 | 186.2 | 522.3 | 174.1 | 155.9 | 192.3 | 526 | 174.9 | 161.8 | 189.3 | 489.1 | 149.2 | 148.3 | 191.6 | 463 | 150.8 | 120.3 | 191.9 |

| Legumes, grains | 32 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 17.4 | 31.1 | 8.1 | 6.2 | 16.8 | 32.6 | 8 | 6.8 | 17.8 | 36 | 10.5 | 7.1 | 18.4 | 38.4 | 15.9 | 5.2 | 17.3 |

| Sorghum grains | 10.1 | 9.5 | 0.6 | - | 6.3 | 5.8 | 0.5 | - | 5.3 | 4.9 | 0.4 | - | 4.7 | 3.9 | 0.8 | - | 6.5 | 5.6 | 0.9 | - |

| Technical crops | 462.1 | 328.8 | 121.6 | 11.7 | 474.5 | 336.0 | 129.3 | 9.2 | 521.4 | 368.3 | 144.0 | 9.1 | 521.8 | 368.1 | 143.1 | 10.6 | 518 | 364.4 | 141.5 | 12.1 |

| Sugar beet | 13.5 | 11.8 | 1.4 | 0.3 | 15.9 | 14.3 | 1.4 | 0.2 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 1.0 | - | 10.7 | 9.9 | 0.8 | - | 14.8 | 13.6 | 0.7 | 0.5 |

| Sunflower | 387.3 | 271.4 | 104.8 | 11.1 | 392.1 | 271.2 | 112.1 | 8.8 | 440.2 | 304.2 | 127.0 | 9.0 | 391.9 | 262.4 | 119 | 10.5 | 420 | 285.9 | 123.9 | 10.2 |

| Soybean | 29 | 16.6 | 12.3 | 0.1 | 22.8 | 11.7 | 11 | 0.1 | 25.3 | 14.2 | 11.1 | - | 25 | 14 | 11 | - | 26.9 | 16.2 | 9.8 | 0.9 |

| Rape | 24.4 | 22 | 2.4 | - | 33.8 | 29.8 | 4 | - | 34.5 | 30.6 | 3.9 | - | 82.8 | 71.5 | 11.3 | - | 43.2 | 37.6 | 5.6 | - |

| Oilseed crops | 5.2 | 5.1 | 0.1 | - | 5.2 | 4.8 | 0.4 | - | 4.8 | 4.7 | 0.1 | - | 5.3 | 5.2 | 0.1 | - | 5.5 | 5.3 | 0.2 | - |

| Potatoes, vegetables and pumpkins | 69.4 | 4.6 | 8.8 | 56 | 67.1 | 4.8 | 8.3 | 54 | 69 | 3.6 | 8.5 | 56.9 | 70.1 | 4.2 | 8.6 | 57.3 | 69.5 | 4.1 | 10.4 | 55 |

| Potatoes | 22.9 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 20.4 | 22.3 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 19.8 | 22.9 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 20.9 | 22.9 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 21.1 | 22.5 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 20.5 |

| Vegetables in the open field | 39.7 | 3.1 | 4.2 | 32.4 | 38 | 3.2 | 3.8 | 31 | 38.2 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 31.8 | 39.3 | 3 | 4.2 | 32.1 | 38.3 | 2.6 | 5.6 | 30.1 |

| Gourd crops | 6.1 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 6.2 | 0.3 | 3 | 2.9 | 7 | 0.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 3.0 | 3.2 | 7.2 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 |

| Forage plants | 48.9 | 13.5 | 18.6 | 16.8 | 44.8 | 10.1 | 18.5 | 16.2 | 37.1 | 11.4 | 12.8 | 12.9 | 34.3 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 13.3 | 35.6 | 13.4 | 9.6 | 12.6 |

| Specification | Period 2020–2024 (Thousand ha) | Structure of Cultivated Areas (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Households of All Categories | Agricultural Enterprises | Peasant Households (Farmers) | Individual Households | ||

| Surfaces—total | 1568.1 | 861.4 | 414.8 | 291.9 | 100 |

| Cereal and legume crops | 959.4 | 492.1 | 256 | 211.2 | 61.2 |

| Wheat | 346.3 | 261.2 | 83.6 | 1.5 | 22.1 |

| Barley | 59.9 | 44.6 | 13.8 | 1.6 | 3.8 |

| Corn kernels | 509.4 | 168.2 | 150.9 | 190.3 | 32.5 |

| Legumes, grains | 34 | 10.2 | 6.3 | 17.5 | 2.2 |

| Sorghum grains | 6.6 | 5.9 | 0.6 | - | 0.4 |

| Technical crops | 499.6 | 353.1 | 135.9 | 10.5 | 31.9 |

| Sugar beet | 13.3 | 12.1 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.8 |

| Sunflower | 406.3 | 279 | 117.4 | 9.9 | 25.9 |

| Soybean | 25.8 | 14.5 | 11 | 0.2 | 1.6 |

| Rape | 43.7 | 38.3 | 5.4 | - | 2.8 |

| Oilseed crops | 5.2 | 5 | 0.2 | - | 0.3 |

| Potatoes, vegetables and pumpkins | 69 | 4.3 | 8.9 | 55.8 | 4.4 |

| Potatoes | 22.7 | 0.9 | 1.2 | 20.5 | 1.4 |

| Vegetables in the open field | 38.7 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 31.5 | 2.5 |

| Gourd crops | 6.6 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 0.4 |

| Forage plants | 40.1 | 11.8 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 2.6 |

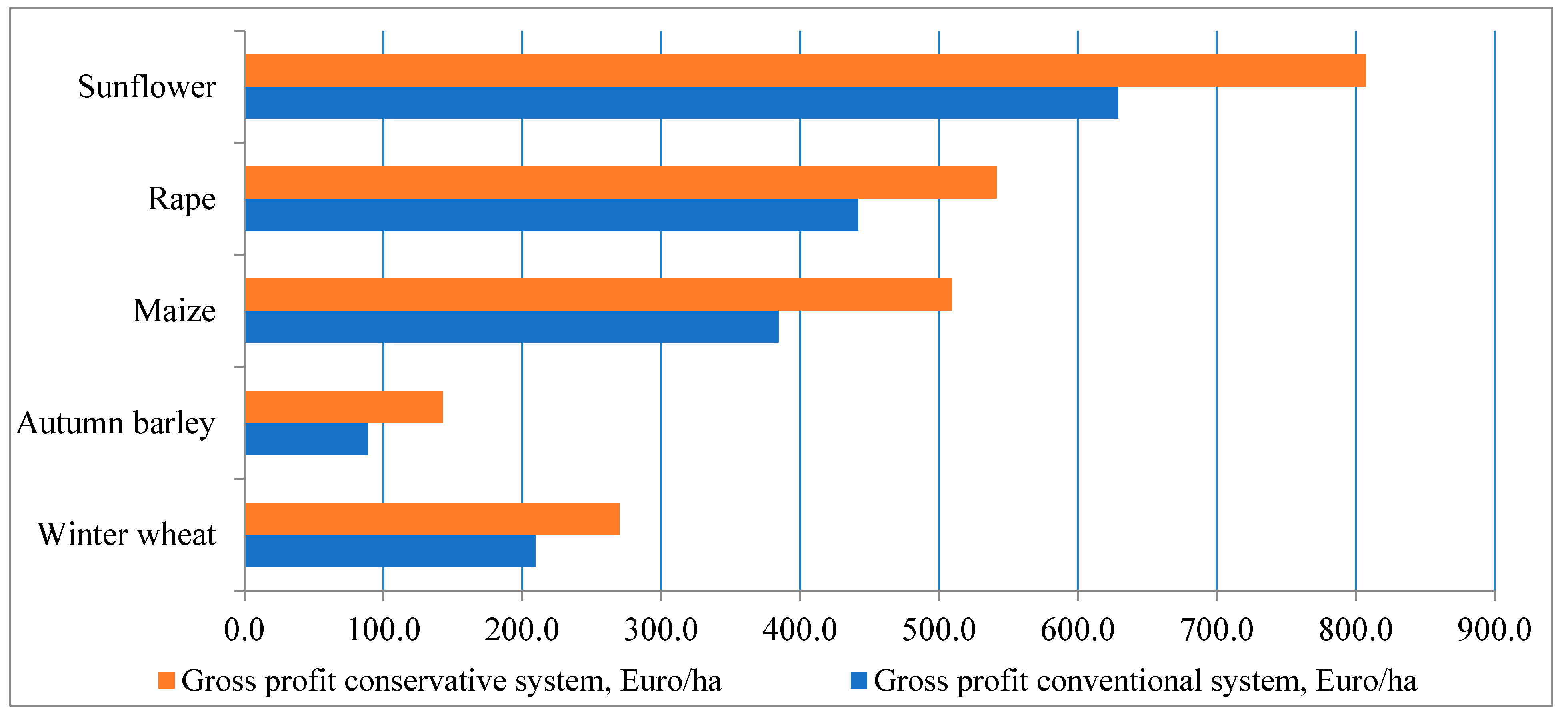

| No. | Crop Specification | Yield Per Hectare, t/ha | Sales Revenue, Euro/ha | Cost of Sales, | Profit, Euro/ha | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Euro/ha | |||||||||

| Means of Production | Mechanized Services | Manual Operations | Other Costs (Rent Payment) | Unforeseen Expenses | ||||||

| Analysis of income and expenditure budgets of conventional farming system | ||||||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 5.6 | 989.9 | 780.4 | 417.5 | 157.9 | 10.7 | 157.1 | 37.2 | 209.5 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 6.2 | 876.8 | 787.9 | 411.9 | 171.5 | 9.9 | 157.1 | 37.5 | 88.9 |

| 3 | Maize | 6.5 | 1050.5 | 666 | 257.2 | 208.7 | 11.3 | 157.1 | 31.7 | 384.5 |

| 4 | Rape | 3.5 | 1502.5 | 1060.6 | 645 | 198.1 | 9.9 | 157.1 | 50.5 | 441.9 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 3.2 | 1325.3 | 696.1 | 291.3 | 208.3 | 6.2 | 157.1 | 33.1 | 629.2 |

| Analysis of income and expenditure budgets conservation agriculture system | ||||||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 6 | 1060.6 | 791 | 464.4 | 120.3 | 11.2 | 157.1 | 37.6 | 270 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 6.5 | 919.2 | 776 | 449.4 | 122.7 | 10.2 | 157.1 | 37.0 | 142.8 |

| 3 | Maize | 7 | 1131.3 | 622 | 306.6 | 116.8 | 11.9 | 157.1 | 29.6 | 509.4 |

| 4 | Rape | 3.7 | 1588.4 | 1047 | 687.3 | 142.3 | 10.3 | 157.1 | 49.9 | 541.5 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 3.5 | 1449.5 | 642 | 328.8 | 119.2 | 6.6 | 157.1 | 30.6 | 807.3 |

| Comparison of revenue and expenditure budgets for the conventional system compared to the conservation one | ||||||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | −0.4 | −70.71 | −10.19 | −46.94 | 37.64 | −0.4 | - | −0.49 | −60.52 |

| 2 | Winter barley | −0.3 | −42.42 | 11.49 | −37.5 | 48.75 | −0.3 | - | 0.55 | −53.92 |

| 3 | Maize | −0.5 | −80.81 | 44.04 | −49.41 | 91.92 | −0.57 | - | 2.1 | −124.85 |

| 4 | Rape | −0.2 | −85.86 | 13.76 | −42.28 | 55.79 | −0.4 | - | 0.66 | −99.62 |

| 5 | Sunflower | −0.4 | −70.71 | −10.19 | −46.94 | 37.64 | −0.4 | - | −0.49 | −60.52 |

| No. | Crop Specification | Yield Per Hectare, t/ha | Economic Profitability, % | Economic Calculations for 1 kg of Production, Euro/t | Annual Cash Flow Available, Euro/ha | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average Selling Price, Euro/t | Unit Cost, Euro/t | Gross Margin (Commercial Markup), Euro/t | |||||

| Analysis of income and expenditure budgets of conventional farming system | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 5.6 | 26.8 | 176.8 | 139.4 | 37.4 | 209.5 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 6.2 | 11.3 | 141.4 | 127.1 | 14.3 | 78.5 |

| 3 | Maize | 6.5 | 57.7 | 161.6 | 102.5 | 59.2 | 384.5 |

| 4 | Rape | 3.5 | 41.7 | 429.3 | 303 | 126.3 | 441.9 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 3.2 | 90.4 | 414.1 | 217.5 | 196.6 | 642.4 |

| Analysis of income and expenditure budgets conservation agriculture system | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 6 | 34.2 | 176.8 | 131.8 | 45 | 270 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 6.5 | 18.4 | 141.4 | 119.4 | 22 | 142.8 |

| 3 | Maize | 7 | 81.9 | 161.6 | 88.8 | 72.8 | 509.4 |

| 4 | Rape | 3.7 | 51.7 | 429.3 | 282.9 | 146.4 | 541.5 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 3.5 | 125.7 | 414.1 | 183.5 | 230.6 | 820.5 |

| Comparison of revenue and expenditure budgets for the conventional system compared to the conservation one | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | −0.4 | −7.3 | - | 7.59 | −7.59 | −60.52 |

| 2 | Winter barley | −0.3 | −7.1 | - | 7.63 | −7.63 | −64.28 |

| 3 | Maize | −0.5 | −24.2 | - | 13.61 | −13.61 | −124.85 |

| 4 | Rape | −0.2 | −10.1 | - | 20.1 | −20.1 | −99.62 |

| 5 | Sunflower | −0.3 | −35.3 | - | 34.03 | −34.03 | −178.08 |

| No. | Plum Variety Specification and Cultivation Technology | Cost of Sales Structure, % | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Means of Production | Mechanized Services | Manual Operations | Other Costs (Including Rent Payment) | Unforeseen Expenses | ||

| Structure of sales costs, conventional system | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 100 | 53.5 | 20.2 | 1.4 | 20.1 | 4.8 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 100 | 52.3 | 21.8 | 1.3 | 19.9 | 4.8 |

| 3 | Maize | 100 | 38.6 | 31.3 | 1.7 | 23.6 | 4.8 |

| 4 | Rape | 100 | 60.8 | 18.7 | 0.9 | 14.8 | 4.8 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 100 | 41.9 | 29.9 | 0.9 | 22.6 | 4.8 |

| Cost of sales structure, conservation system | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | 100 | 58.7 | 15.2 | 1.4 | 19.9 | 4.8 |

| 2 | Winter barley | 100 | 57.9 | 15.8 | 1.3 | 20.2 | 4.8 |

| 3 | Maize | 100 | 49.3 | 18.8 | 1.9 | 25.3 | 4.8 |

| 4 | Rape | 100 | 65.7 | 13.6 | 1.0 | 15.0 | 4.8 |

| 5 | Sunflower | 100 | 51.2 | 18.6 | 1.0 | 24.5 | 4.8 |

| Comparison of deviations for the conventional system compared to the conservation system | |||||||

| 1 | Winter wheat | - | 5.2 | −5 | - | −0.3 | - |

| 2 | Winter barley | - | 5.6 | −6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | - |

| 3 | Maize | - | 10.7 | −12.6 | 0.2 | 1.7 | - |

| 4 | Rape | - | 4.8 | −5.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | - |

| 5 | Sunflower | - | 9.3 | −11.4 | 0.1 | 1.9 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zbancă, A.; Rusu, T.; Panuța, S.; Negritu, G. Conservation Agriculture as a Pathway to Climate and Economic Resilience for Farmers in the Republic of Moldova. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410916

Zbancă A, Rusu T, Panuța S, Negritu G. Conservation Agriculture as a Pathway to Climate and Economic Resilience for Farmers in the Republic of Moldova. Sustainability. 2025; 17(24):10916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410916

Chicago/Turabian StyleZbancă, Andrei, Teodor Rusu, Sergiu Panuța, and Ghenadie Negritu. 2025. "Conservation Agriculture as a Pathway to Climate and Economic Resilience for Farmers in the Republic of Moldova" Sustainability 17, no. 24: 10916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410916

APA StyleZbancă, A., Rusu, T., Panuța, S., & Negritu, G. (2025). Conservation Agriculture as a Pathway to Climate and Economic Resilience for Farmers in the Republic of Moldova. Sustainability, 17(24), 10916. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172410916