1. Introduction

Ocean waves represent a vast, largely untapped source of renewable energy. Recent estimates suggest the global wave energy resource is on the order of 29,500 TWh per year [

1], underscoring its potential to contribute significantly to future clean energy mixes. However, capitalising on this resource has proven challenging due to limitations in conventional wave energy converter (WEC) designs. Conventional wave energy converters (WECs) often utilise single-degree-of-freedom (SDOF) linear oscillators in conjunction with linear generators to convert mechanical motion into electricity [

2,

3]. While such systems are mechanically simpler, they typically suffer from narrow operational bandwidths, limiting their efficiency in the variable and irregular wave conditions found in real marine environments [

4]. Rotary generator-based WECs also introduce mechanical complexities through gearboxes and hydraulics, which further reduce reliability and increase maintenance requirements. Other WECs use rotary generators coupled through gearboxes or hydraulic power take-off mechanisms to convert slow wave-induced motion into high-speed rotation. Such arrangements introduce complex moving parts, increasing the risk of mechanical failure and higher maintenance requirements (e.g., due to gearbox wear or hydraulic fluid leakage), thereby reducing their overall reliability [

4].

These inherent constraints on bandwidth and reliability have hindered the widespread adoption of wave energy technology. To address these challenges, researchers have explored WEC architectures based on nonlinear oscillators and magnetic spring mechanisms. Unlike linear resonators, nonlinear oscillators (including bistable and multi-stable systems) can respond over a broader range of frequencies and amplitudes, thereby harvesting energy more effectively from random or irregular wave inputs. In particular, magnetic spring or magnetic levitation elements provide contactless, tuneable restoring forces that alleviate friction and mechanical wear while enabling adjustable stiffness characteristics [

4]. This magnetic restoring force behaves like a nonlinear spring, whose effective spring constant changes with displacement, thereby helping to widen the device’s frequency response. A recent study optimised magnet configurations in a low-frequency (<0.3 Hz) electromagnetic wave harvester and demonstrated that the number of levitating and base magnets has a strong influence on induced EMF and harvested power [

5]. However, the design remains limited to a single-degree-of-freedom oscillation, so performance gains are mainly achieved through flux variation rather than broadband resonance from multiple oscillation modes. Another promising strategy is to implement multi-degree-of-freedom (MDOF) oscillatory systems [

6]. By introducing multiple coupled degrees of freedom (e.g., two-DOF or three-DOF oscillators) concepts, a WEC can exhibit several resonant modes and thus capture wave energy across a broader frequency spectrum [

7,

8]. Indeed, recent studies indicate that a multi-DOF oscillator-based generator may absorb more wave energy than traditional single-DOF devices under real sea conditions [

9,

10,

11]. Combining nonlinear dynamics with multiple resonant modes provides a pathway to overcome the narrow-bandwidth issue of SDOF linear converters and enhance energy conversion efficiency in variable sea states.

In this work, we present a novel three-degree-of-freedom (3DOF) wave energy converter that leverages both the restoring forces of magnetic springs and multi-mode oscillation to enhance broadband energy capture. The proposed device consists of three levitated permanent magnets acting as oscillating masses, stacked along a vertical axis and magnetically suspended between fixed magnets. This configuration creates three contactless magnetic spring–mass subsystems: each floating magnet experiences a repulsive restoring force from its neighbouring fixed magnets and is coupled to its independent coil for electromagnetic power generation. The magnets are arranged with alternating polarity to minimise magnetic field interference and cogging effects, ensuring that each oscillating magnet–coil unit operates with minimal coupling to the others. By virtue of its three oscillation modes (one per degree of freedom), the 3DOF harvester can resonate at multiple frequencies, allowing it to absorb wave energy over a wider range of wave periods than comparable SDOF or 2DOF designs.

This magnetic levitation-based 3DOF approach is an innovative extension of earlier two-degree-of-freedom WEC concepts, providing an additional resonant mode without introducing mechanical complexity or contact friction. It thereby offers the potential for higher power output and greater adaptability to varying wave spectra. The scope of this paper encompasses the design, modelling, and experimental evaluation of the 3DOF magnetic spring-based WEC. A nonlinear analytical model of the device is developed using a state-space formulation, capturing the coupled electromechanical dynamics of the three oscillators. The model is used to predict key performance characteristics, including magnetic flux distributions, natural frequencies, mode shapes, and expected power output under various magnet positioning configurations. To validate the theoretical predictions, a laboratory-scale prototype of the 3DOF PTO system is constructed and tested under controlled wave-like excitations. The experimental results confirm the presence of three distinct resonant peaks and a significantly wider operational bandwidth compared to equivalent SDOF and 2DOF systems. Comparative analyses with single- and two-degree-of-freedom benchmarks highlight the performance gains of the 3DOF design, demonstrating improved energy conversion efficiency and power levels across a range of frequencies.

2. The Architecture of the 3DOF Oscillator-Based PTO System

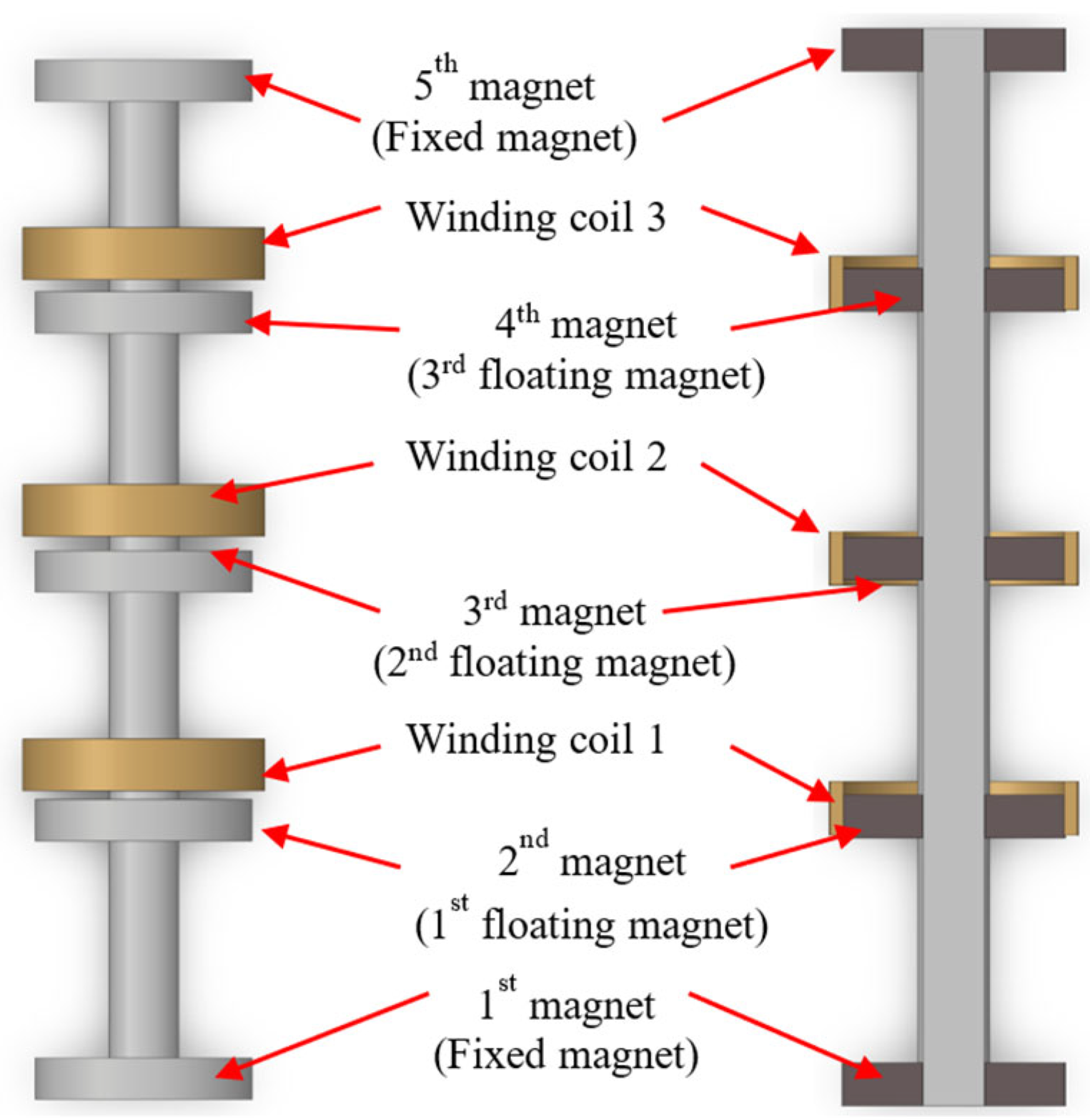

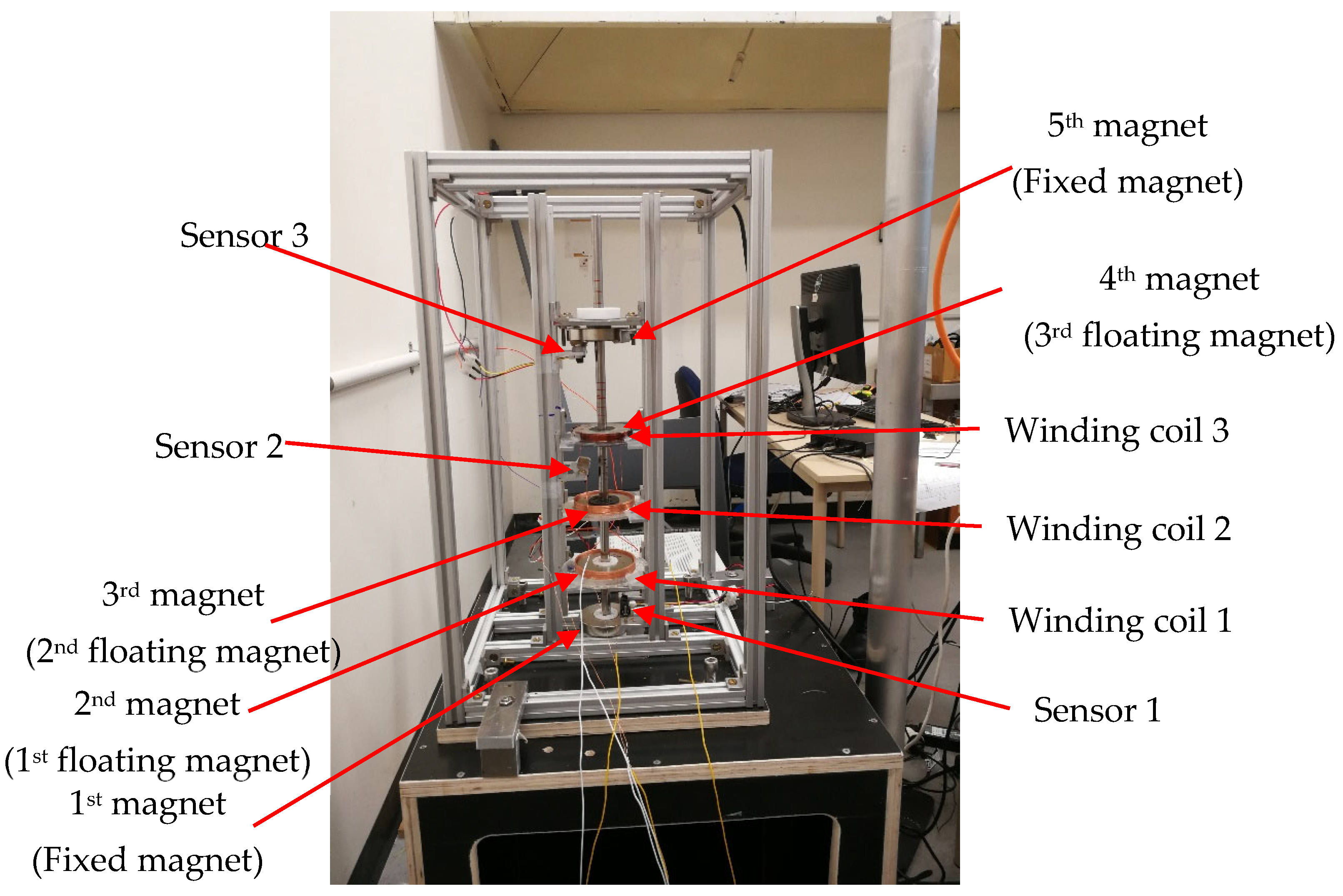

The basic architecture of the energy harvester consists of five-ring permanent magnets (axially magnetised), a circular shaft and winding coils. The 3DOF energy harvester is designed so that the magnetic restoring forces and induced voltage of every function should not affect or influence the magnetic field of each magnet, particularly when the floating magnets are in motion. Due to the movement of all floating magnets inside the winding coil, the cogging force is usually created. Minimising the generated harmful cogging force from the movement of magnets and coils is essential. Different nonmagnetic materials have been used to avoid magnetic field interference. The polarity of the magnets is arranged so that the levitating magnet experiences a repulsive force because of the fixed magnets. A few multilayer coils are attached around the outer surface of the two floating magnets. The magnetic poles are oriented (NS-SN-NS-SN-NS) to repel each other. The height and width of the test rig are 550 mm and 300 mm, respectively. Moreover, the height and diameter of the shaft are 550 mm and 12 mm, respectively. For the test rig design, as presented in

Figure 1, the equilibrium height of the 3DOF oscillator is 372 mm. For the equilibrium position, the separation distance between the first and second magnet is 59 mm, and the distance between the second and third magnet is 65 mm. Moreover, the distance between the third and 4th magnet is 79 mm, and the separation distance between the 4th and 5th is 104 mm. Three winding coils have been added to the test rig, and both winding coils have been connected to the data acquisition system to capture the induced voltages. A floating magnet connected the servo motor using a fishing line.

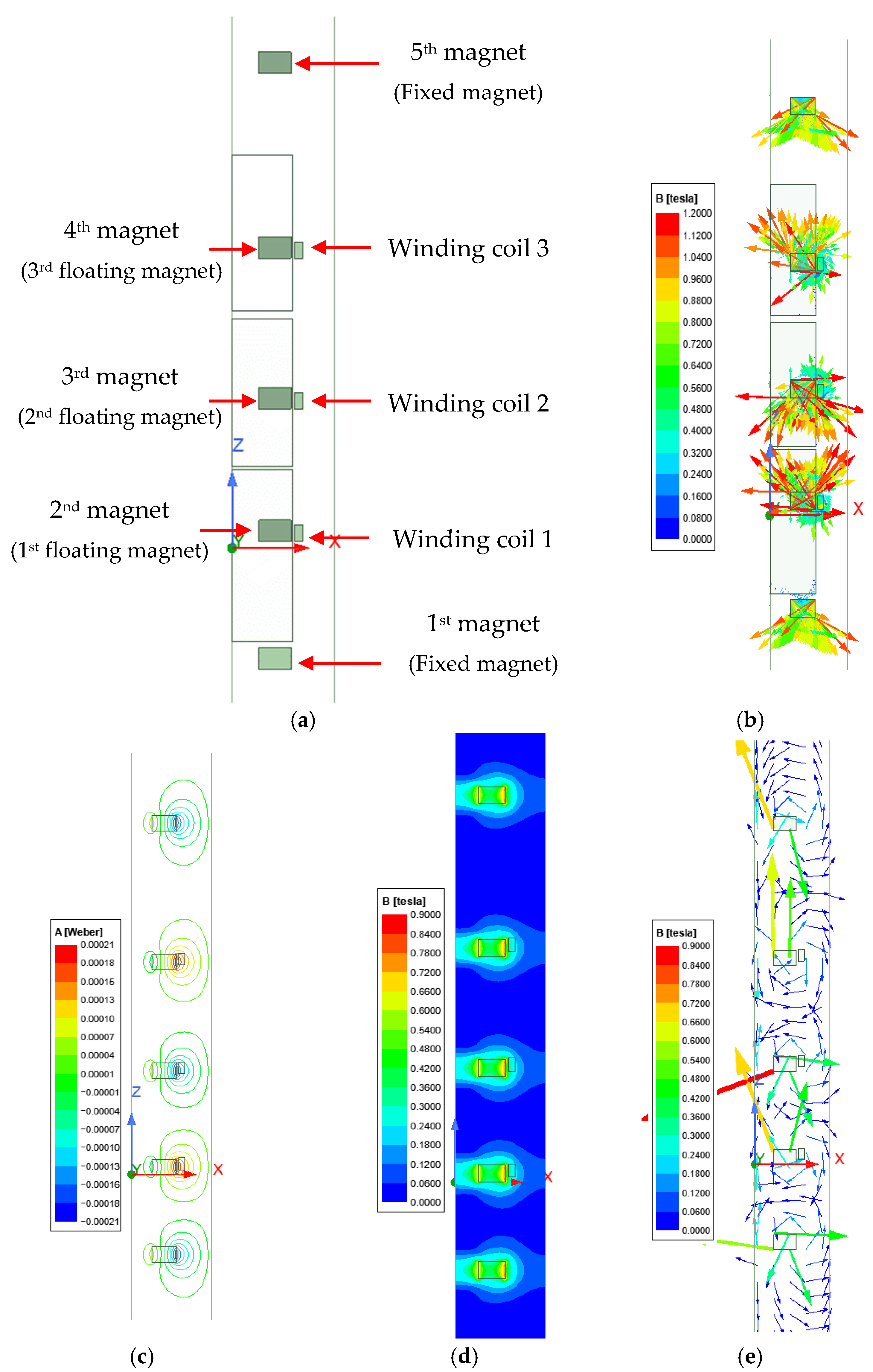

The proposed 3DOF generator model has been analysed as a 2D axisymmetric model in ANSYS MAXWELL (version 2020R2), as shown in

Figure 2a. Three winding coils (100 turns each) have been placed on the outer surfaces of each floating magnet. The simulation was run using constant velocity for all three floating magnets during the transient solution. The magnetisation direction of all magnets, flux line, flux linkage, magnetic flux density and induced voltages have been investigated.

Figure 2b shows the magnetisation direction of all five magnets, and

Figure 2c presents the flux line of all five magnets. The arrows in

Figure 2b represent the magnetisation directions of all permanent magnets. The maximum flux lines can be seen on the outer surfaces of each magnet and within the coil area, as shown in

Figure 2c. The magnetic flux (Mag_B) and magnetic flux (B_Vector) of the 3DOF electromagnetic generator have been shown in

Figure 2d,e. A constant velocity was used to move all floating magnets to analyse the magnetic flux densities. As shown in

Figure 2d, the colour represents the magnetic flux density of the generator system. The higher flux density is visible around the permanent magnet area, characterised by colour variations. According to

Figure 2e, the magnetic flux lines originated from the north pole and travelled to the south pole, and they travelled through the inside coil of the magnet. Copper coils generate an induced voltage when they are cut by magnetic flux. Magnetic flux densities of the generator also changed over time, along with the positions of the floating magnets.

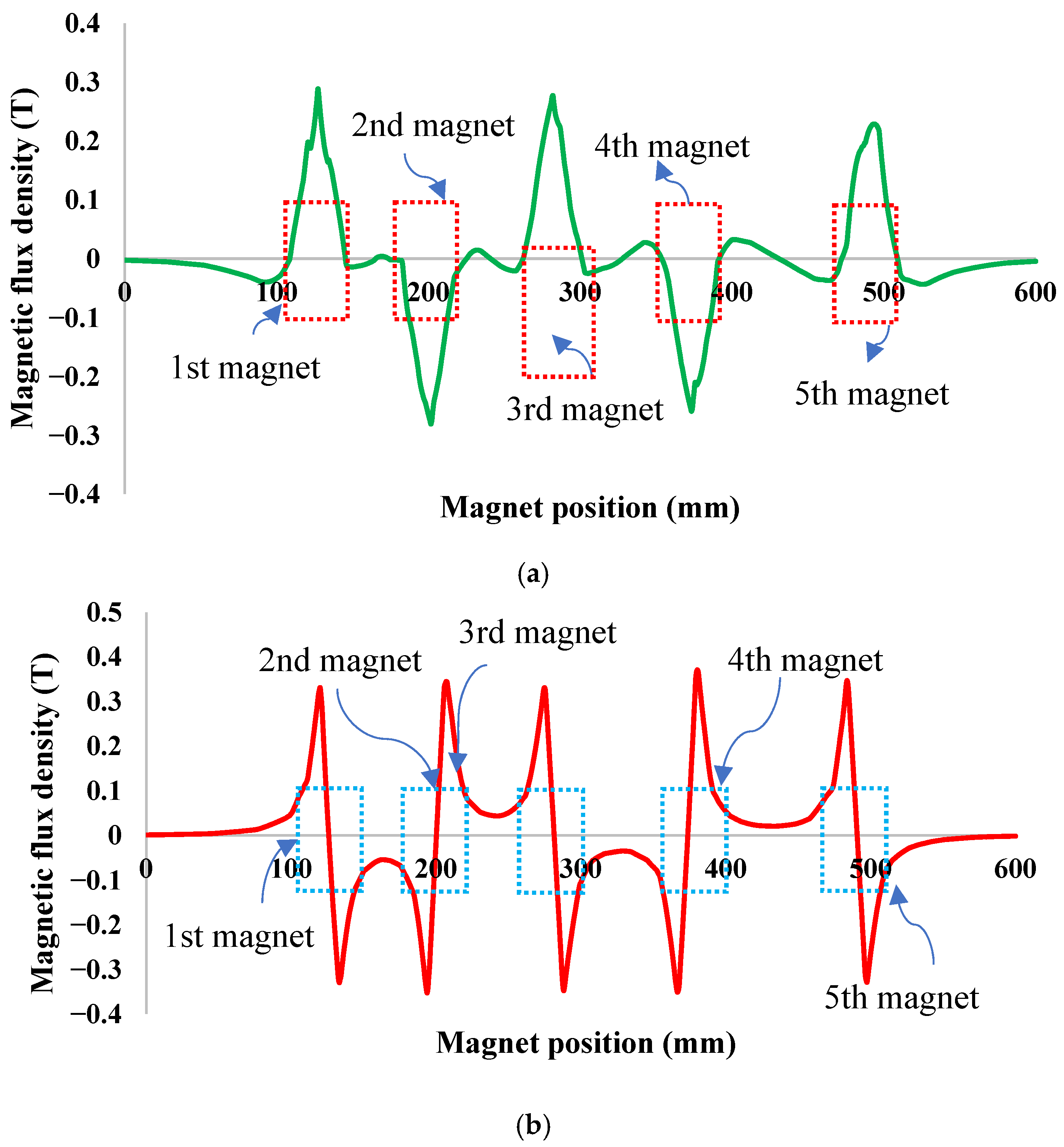

Analysis of the magnetic flux density distribution in

Figure 3 provides insight into the performance advantage of the third floating magnet. The static radial and axial flux maps in

Figure 3a,b show that the magnetic field around the first and second magnets is highly distorted and undergoes polarity reversal. In contrast, the third magnet is exposed to a smoother and more symmetric field. Furthermore, the transient flux–density evolution in

Figure 3c confirms that the magnetic polarity in the third region remains stable throughout the oscillation, unlike the other regions where abrupt fluctuations occur. This stability produces a greater and more consistent change in flux linkage during motion, directly leading to higher RMS voltage in the third coil and ultimately improved power output.

3. Dynamics of the 3DOF Oscillator-Based PTO System

The matrix form of the state-space model of the 3DOF oscillator-based PTO system can be expressed as

where

A is the system matrix,

B is the input matrix and

C is the output matrix. The remaining matrix is

D, which is typically zero because the input directly does not usually affect the output. If the coils are connected in parallel to an external load or resistance

Re1,

Re2 and

Re3, then the parallel-connected winding coils have the internal resistances

R1,

R2 and

R3 and inductances

L1,

L2 and

L3. The state-space model of the system can be written in matrix form using the developed equation of motion [

12,

13]. The masses of the second (first floating magnet), third (second floating magnet) and fourth (third floating magnet) magnets are

M2,

M3 and

M4, respectively. The relative displacement of the first floating magnet is

y2 and the relative velocity and acceleration of the first floating magnet are

and

, respectively. The relative displacement, velocity and acceleration of the second floating magnet are

y3,

and

, respectively. Moreover, the relative displacement, velocity and acceleration of the third floating magnet are

y4,

and

, respectively. The magnetic flux density of the second magnet (first floating magnet) is

B1(y) and the total length of the first winding coil is

l1. The magnetic flux density of the third magnet (second floating magnet) is

B2(y) and the total length of the second winding coil is

l2. Similarly, the magnetic flux density of the fourth magnet (third floating magnet) is

B3(y) and the total length of the third winding coil is

l3. The electromagnetic coupling coefficients are

a1(

),

a2(

) and

a3(

). The linear stiffnesses of the system are

k1,

k2,

k3 and

k4. The damping constants of the system are

,

,

and

. The nonlinear coefficients are

α1,

α2,

α3 and

α4. In addition, the other nonlinear stiffnesses of the system are

,

,

and

.

The variables in Equations (1) and (3) can be stated as

The following variables can be considered as

Here, and V1 are grouped nonlinear stiffness and coupling terms: P1 is the effective stiffness of the first magnet, Q1 and R1 describe the bidirectional coupling between the first and second magnets, J1 is the effective stiffness of the second magnet, E1 and U1 describe the coupling between the second and third magnets and V1 is the effective stiffness of the third magnet.

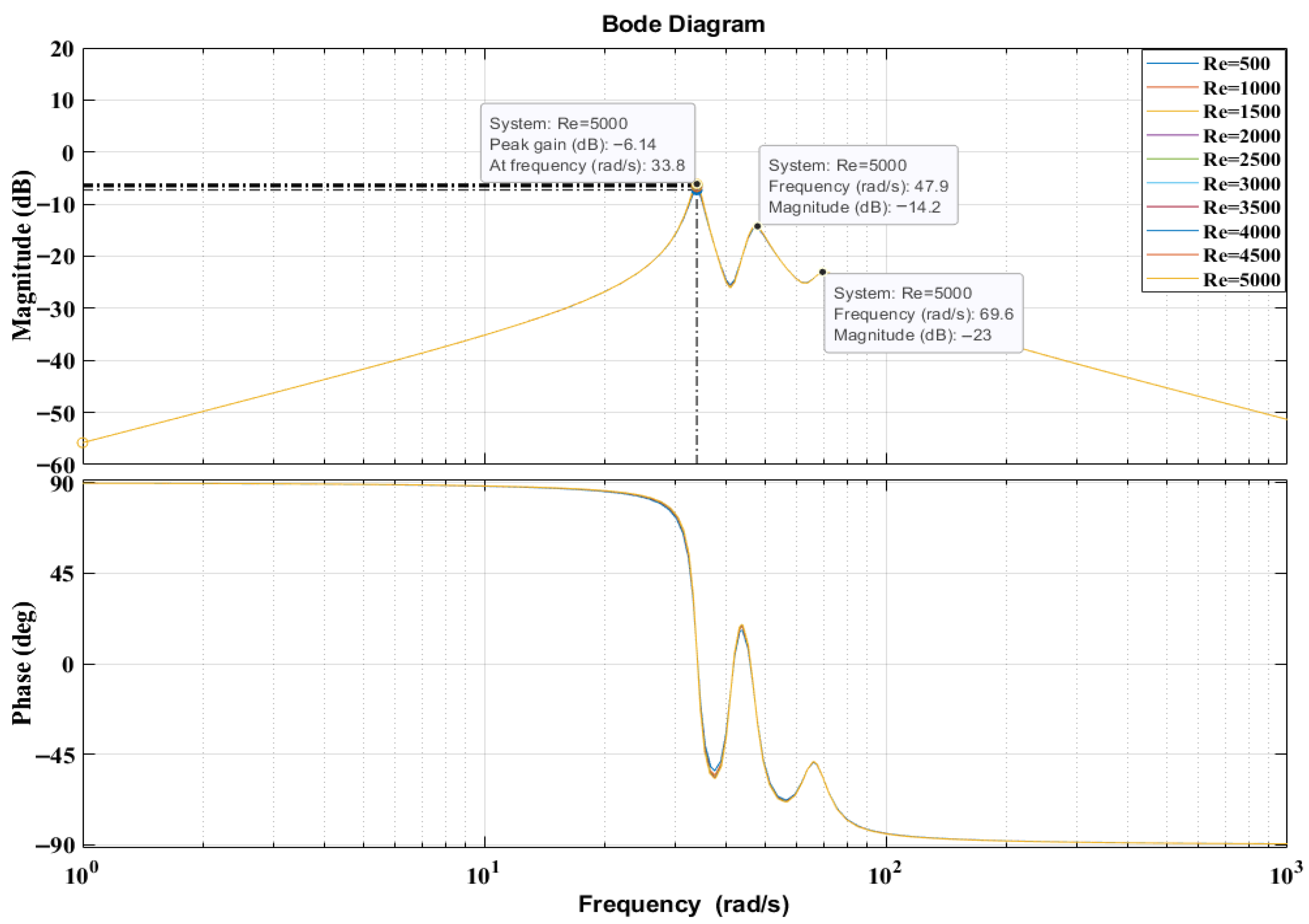

After establishing the dynamic equations, eigenvalue analysis is used to determine the natural frequencies and modal characteristics of the 3DOF magnetic spring system. This step is essential for identifying the expected resonance locations and validating whether the model can support multi-mode broadband energy extraction before running time–domain simulations. The eigenvalues and frequency response of the 3DOF generator system have been analysed using the state-space model as presented in Equations (1) and (2). The three eigenvalues correspond to the three resonant modes of the PTO system, which later appear in the frequency–response curves (as shown in

Figure 4), confirming the analytical model’s physical validity. The coefficients of the generator system are determined by measuring the magnetic restoring forces. Three winding coils, each consisting of 100 turns, have been used. The diameter of each copper coil was 31 mm. Coil 1 (first winding coil) was placed outside of the first floating magnet, coil 2 (second winding coil) was placed outside of the second floating magnet, and coil 3 (third winding coil) was placed outside of the third floating magnet. The inside diameter and height of each winding coil were 75 mm and 10 mm, respectively. The total length of each winding coil was 23.5 m, and the inner resistance of each coil was 5.48 ohm. The average magnetic flux density was 0.35 T. Due to electromechanical coupling, the 3DOF generator system comprises both electrical and mechanical components. Three winding coils have been added outside the three floating magnets, and therefore, the system has three resonance frequencies in the electrical part. Due to the presence of three floating magnets, the system exhibits three mechanical resonance frequencies. The changing position of the floating magnets changed the resonance frequencies of the generator system. The electrical part’s resonance frequencies depend on the total length of the winding coil and the magnetic flux density of the magnets. With increasing the magnetic flux density, the resonance frequencies of the electrical part reduced, but the resonance frequencies of the mechanical part were approximately the same. The resonance frequency of the electrical component is reduced by increasing the total length of the winding coil.

Table 1 shows all required parameters used to analyse the dynamics of the 3DOF generator system.

However, the resonance frequency of the mechanical part remained unchanged with the variation in the length of the winding coils. The natural frequencies of the electrical parts were 953.36 rad/s, 948.57 rad/s and 949.4 rad/s when all three floating magnets were in equilibrium positions, as shown in

Table 2. The natural frequencies for the mechanical parts were 69.24 rad/s, 47.77 rad/s and 34.58 rad/s. The natural frequencies of the mechanical part were nearly similar with or without electrical-mechanical coupling.

The eigenvalues of the mechanical parts were −25.16 ± 64.51i, −21.32 ± 42.76i and −20.35 ± 27.96i. The eigenvalues of the electrical parts were −953.35 + 0.0i, −948.58 + 0.0i and −949.40 + 0.0i.

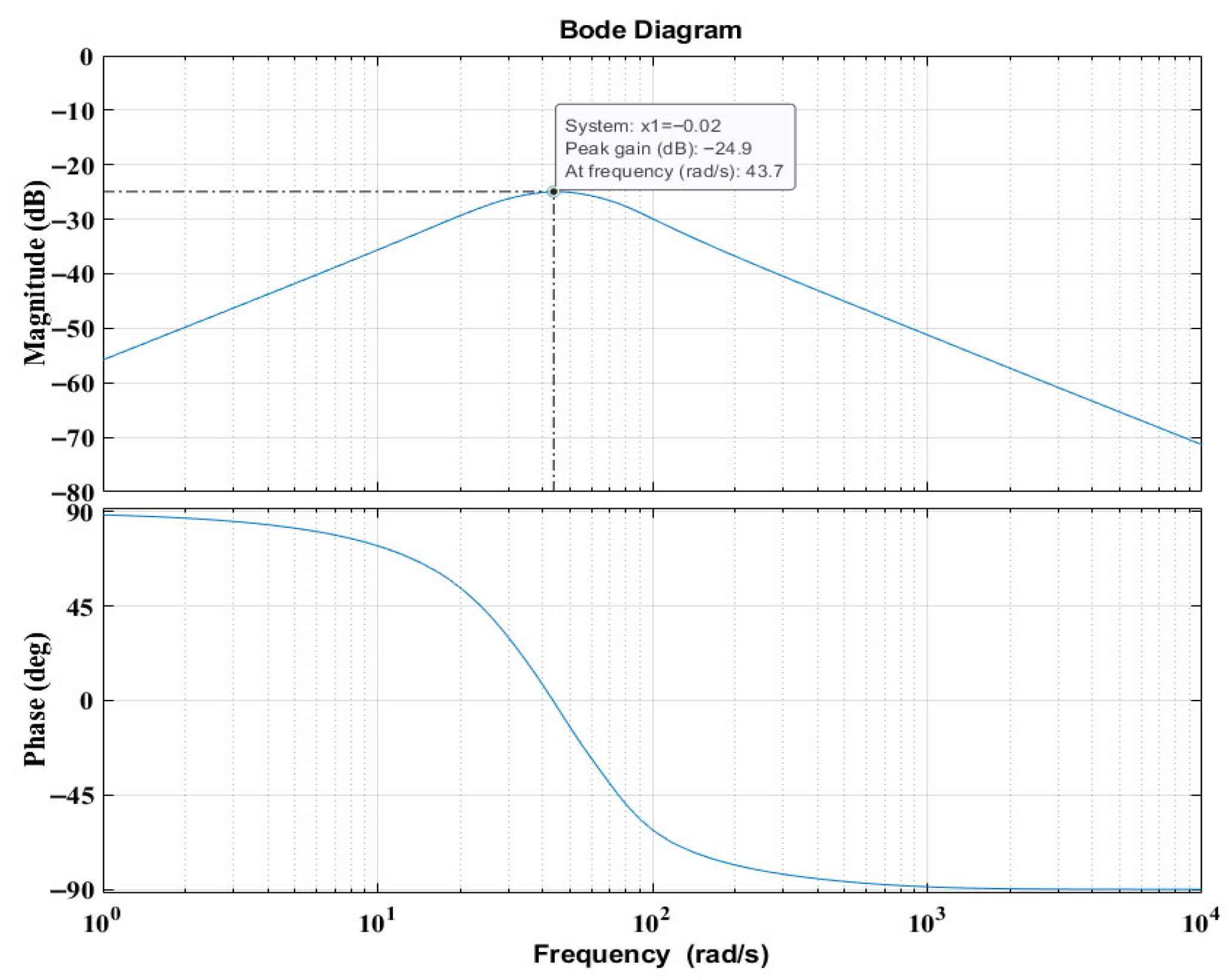

Figure 5 presents the Bode diagram of the 3DOF generator system evaluated at its equilibrium position. The frequency response was obtained by linearising the nonlinear electromechanical model around the static operating point and analysing the transfer function between the applied external excitation force and the floating magnet’s displacement. The magnitude plot does not exhibit a sharp resonance peak because the electromagnetic coupling introduces distributed damping and stiffness effects that broaden the response and suppress high-amplitude oscillation. Nevertheless, the system’s resonance behaviour is clearly visible: the maximum gain occurs at approximately 43.7 rad/s, confirming the dominant natural frequency of the coupled 3DOF configuration. The corresponding phase plot shows the expected transition from +90° at low frequencies to −90° at high frequencies, further validating the model’s dynamic consistency.

Table 2 presents the measured eigenvalues and natural frequencies of the electrical part for various positions of the floating magnets. Moreover, the estimated eigenvalues and natural frequencies of the mechanical part for different positions of the floating magnets have been presented in

Table 3.

From

Table 2, it can be seen that there was no significant change in the eigenvalues or natural frequencies of the electrical par when the floating magnets changed their positions. However, the eigenvalues and natural frequencies of the mechanical part changed with the change in the position of the floating magnet, as seen in

Table 3. The 3DOF generator system displayed higher mechanical frequency responses when all floating magnets moved toward the bottom magnet.

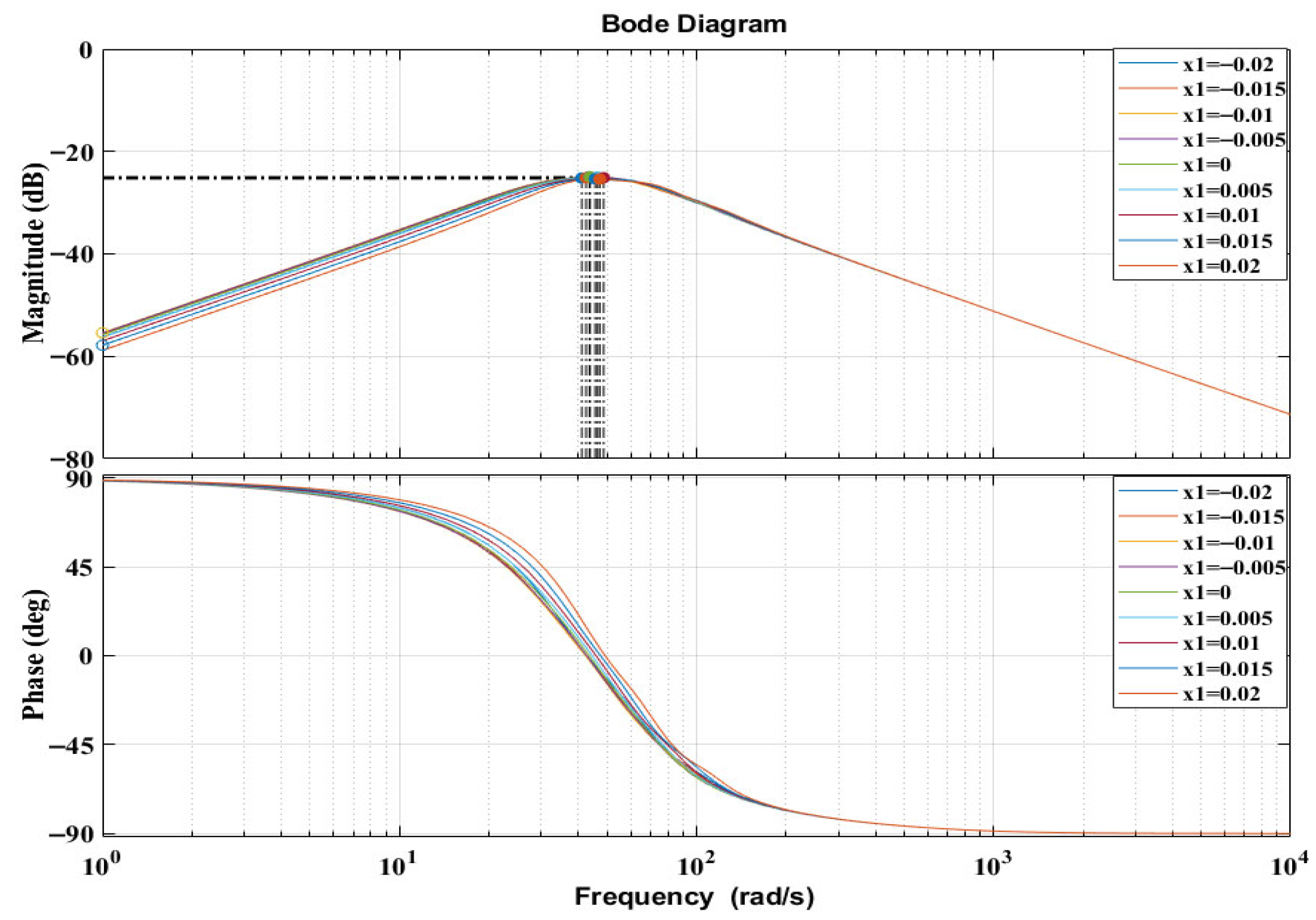

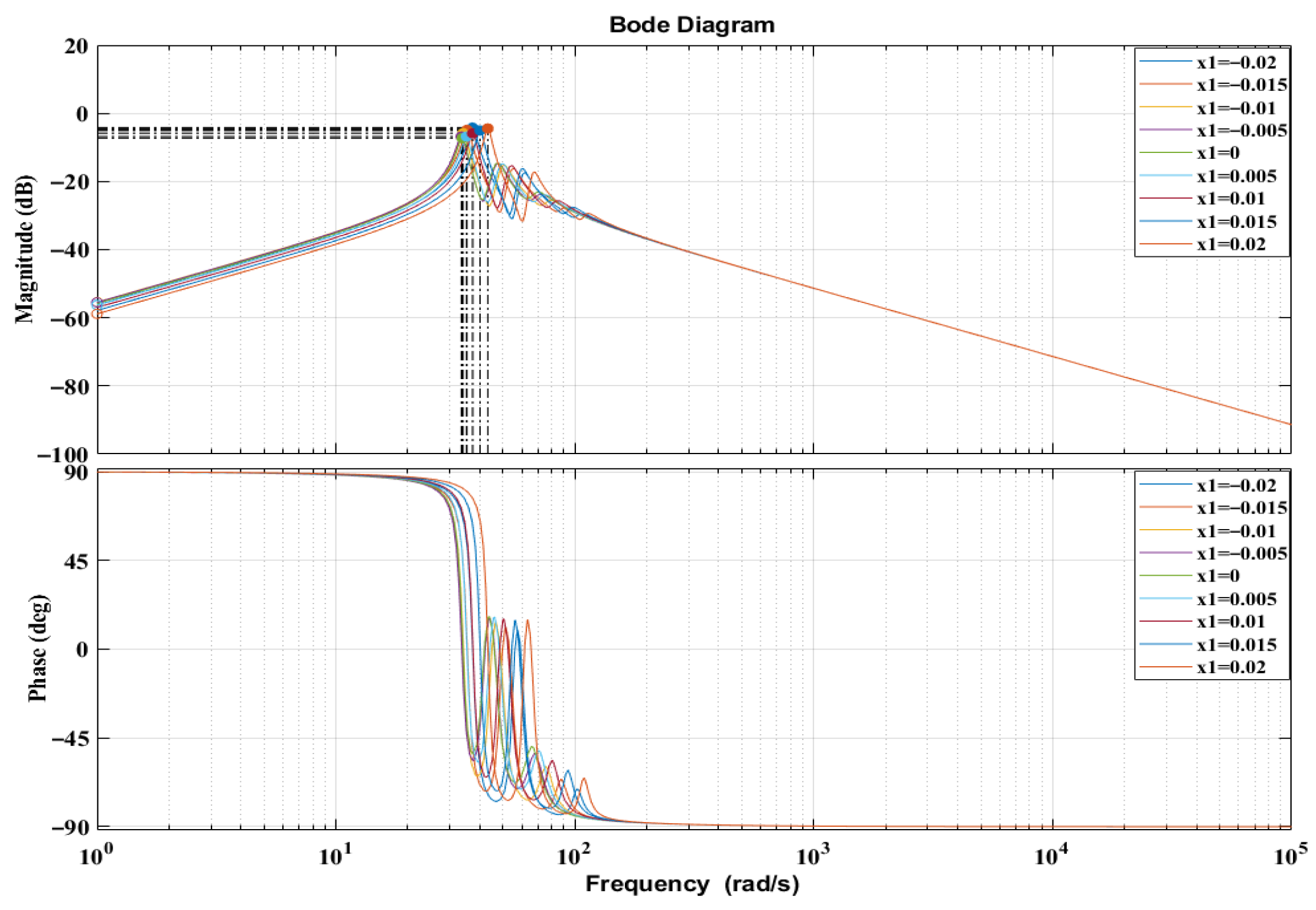

Figure 6 shows the frequency responses of the 3DOF generator system for different positions of the floating magnets.

To further investigate how the magnetic spring configuration influences the dynamics, the positions of all three floating magnets were varied systematically. The resulting frequency responses are presented in

Figure 6. As the magnets’ axial positions were altered, the resonance characteristics shifted, indicating that the system’s stiffness and modal coupling are highly dependent on the spatial magnetic configuration. Although the peak amplitudes do not manifest clearly because the system is electrically unloaded, the natural frequencies migrate with magnet position, confirming the strong sensitivity of modal behaviour to the magnetic restoring forces.

Figure 4 examines the generator under realistic operating conditions by connecting external electrical loads in parallel with the winding coils. With the electrical load applied, three distinct resonance peaks emerge at 33.8 rad/s, 47.9 rad/s and 69.6 rad/s—corresponding closely to the three natural frequencies obtained via eigenvalue analysis (34.58, 47.77 and 69.24 rad/s). Compared to

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, the resonances become far more pronounced when a load is present because the load reduces electromagnetic damping, allowing resonance modes to appear more clearly. This experimentally relevant behaviour confirms that the 3DOF system supports multi-mode energy harvesting, unlike classical 1DOF and 2DOF PTO architectures.

Finally,

Figure 7 explores the combined effect of magnet position and electrical load on frequency response. For all magnet positions, three resonances remain visible, demonstrating that multi-mode dynamics are preserved across configurations. However, each resonance peak shifts with the location of the floating magnets, further verifying that the system stiffness and modal coupling are tuneable through geometry. Compared with the unloaded responses (

Figure 6), the electrically loaded system yields higher resonance peaks and clearer modal separation, indicating improved dynamic observability and stronger power-conversion potential.

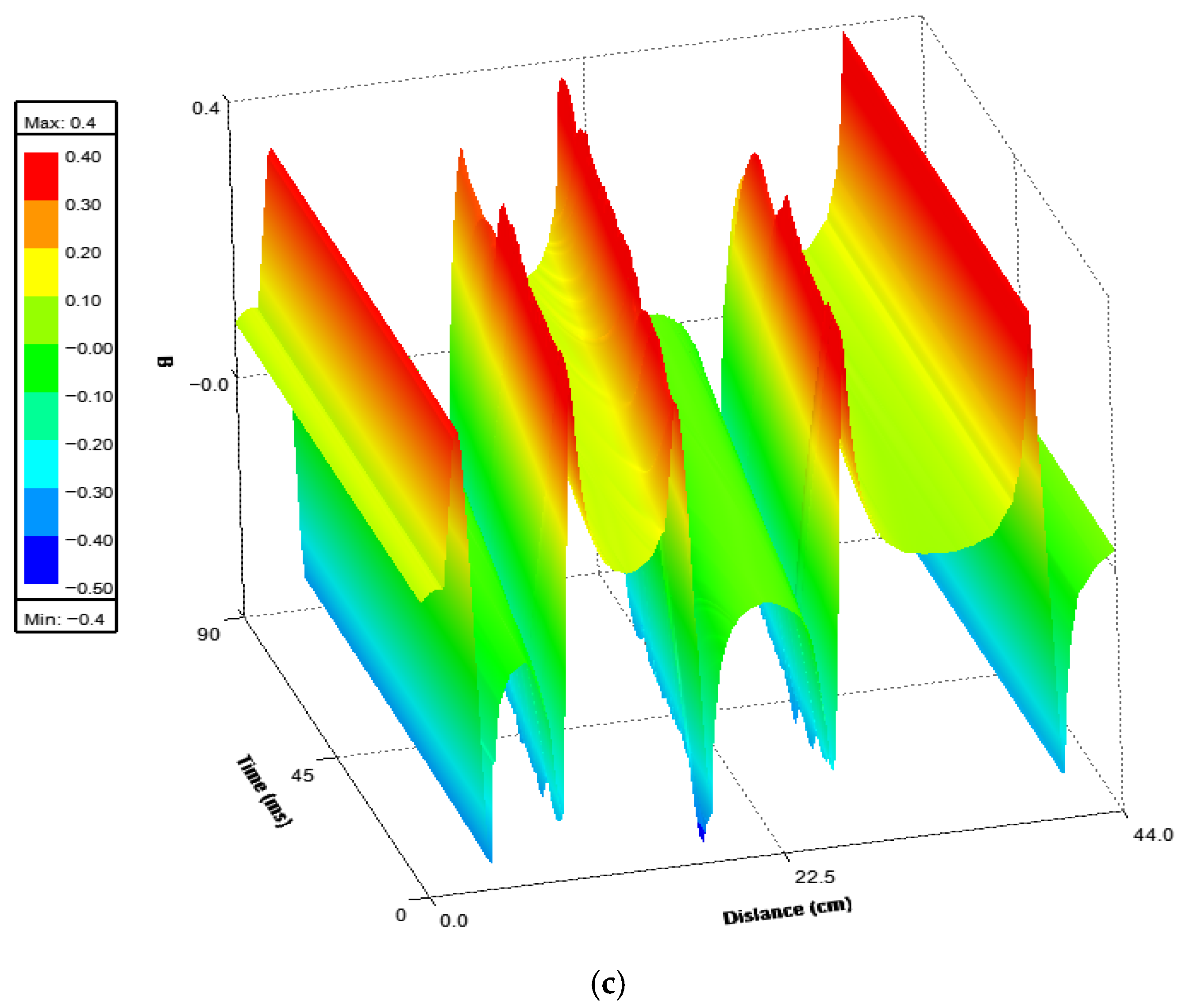

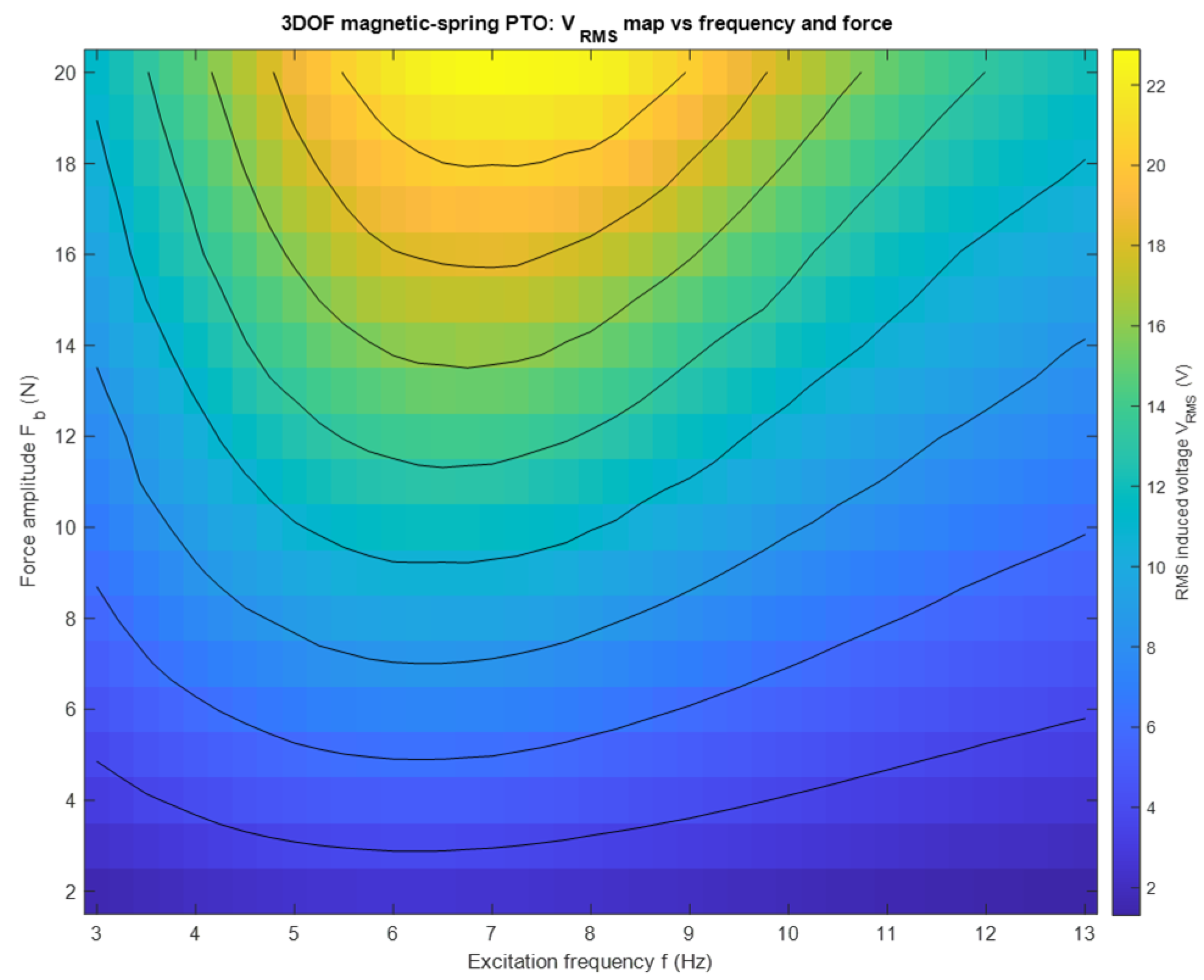

Figure 8 presents a performance map of the 3-DOF magnetic spring PTO, showing the RMS induced voltage as a function of excitation frequency (x-axis) and force amplitude (y-axis). Warmer colours represent higher voltage output, while cooler colours indicate lower output; contour lines show isolines of constant RMS voltage. The map highlights that maximum output occurs around 6–8 Hz and at higher force amplitudes (≈18–20 N), confirming broadband resonance behaviour and strong voltage amplification with increased excitation. This demonstrates that the 3-DOF configuration efficiently harvests energy across a wide range of operating conditions rather than only at a single narrow resonance peak.

4. Experimental Analysis of the 3DOF Oscillator-Based PTO System

The experimental work on the proposed 3DOF oscillator-based PTO system was carried out by connecting fishing lines with different floating magnets and applying various harmonic forces. Three winding coils (100 turns each) were added to the test rig to generate the induced voltages from the movement of the floating magnets. The first winding coil was placed outside the first floating magnet, and the second winding coil was placed outside the second floating magnet. Similarly, the third winding coil was placed outside the third floating magnet, as shown in

Figure 9. Each winding coil was connected to the data acquisition system to measure the induced voltages generated. The induced voltage was generated in the winding coils 1 and 2 due to the movement of the first and second floating magnets, respectively. Similarly, the induced voltage was generated inside winding coil 3 due to the excitation of the third floating magnet. At first, the experimental work was performed by connecting the servo motor using the fishing line with the first floating magnet (the fishing line went through the plastic bush of the second and third floating magnets).

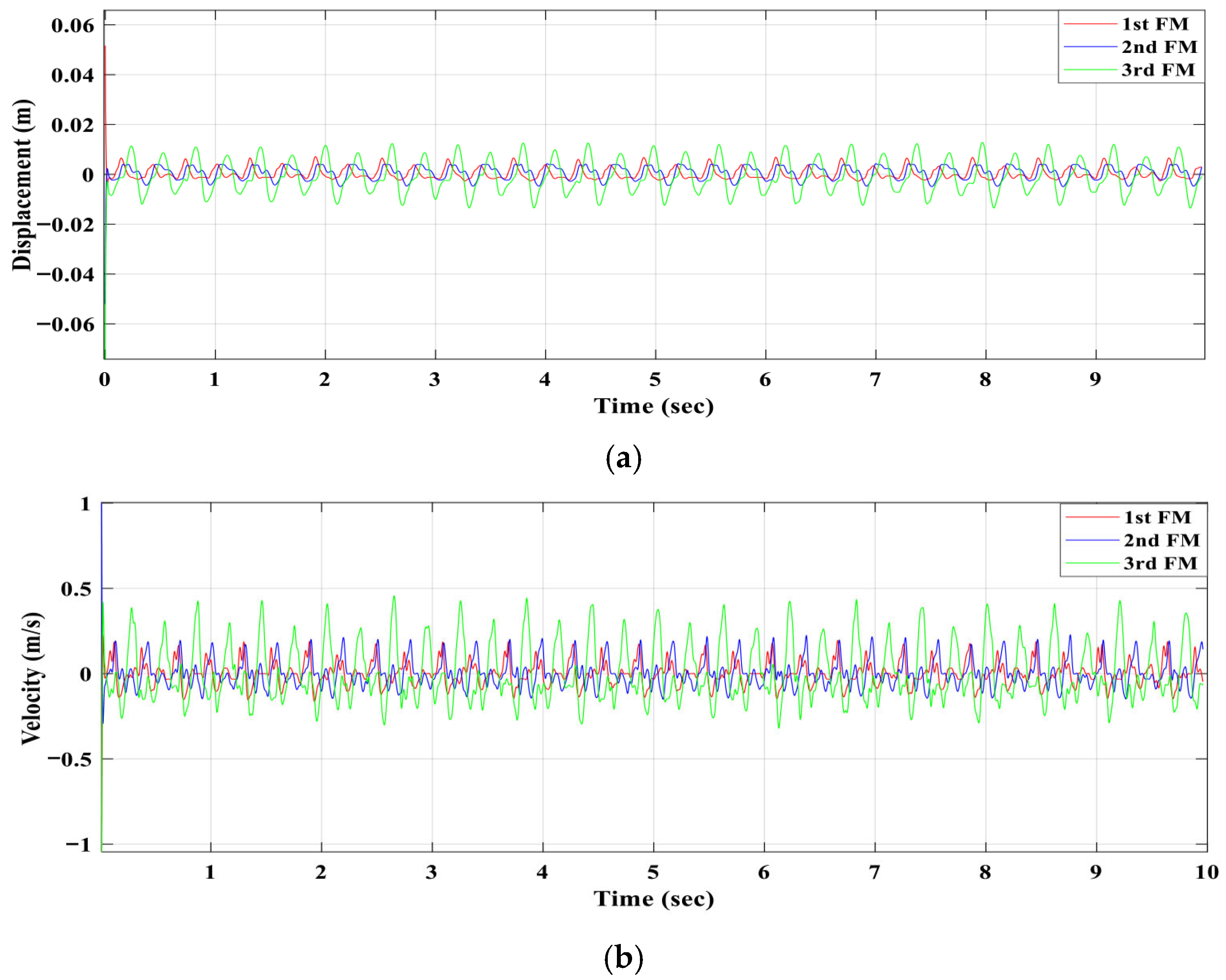

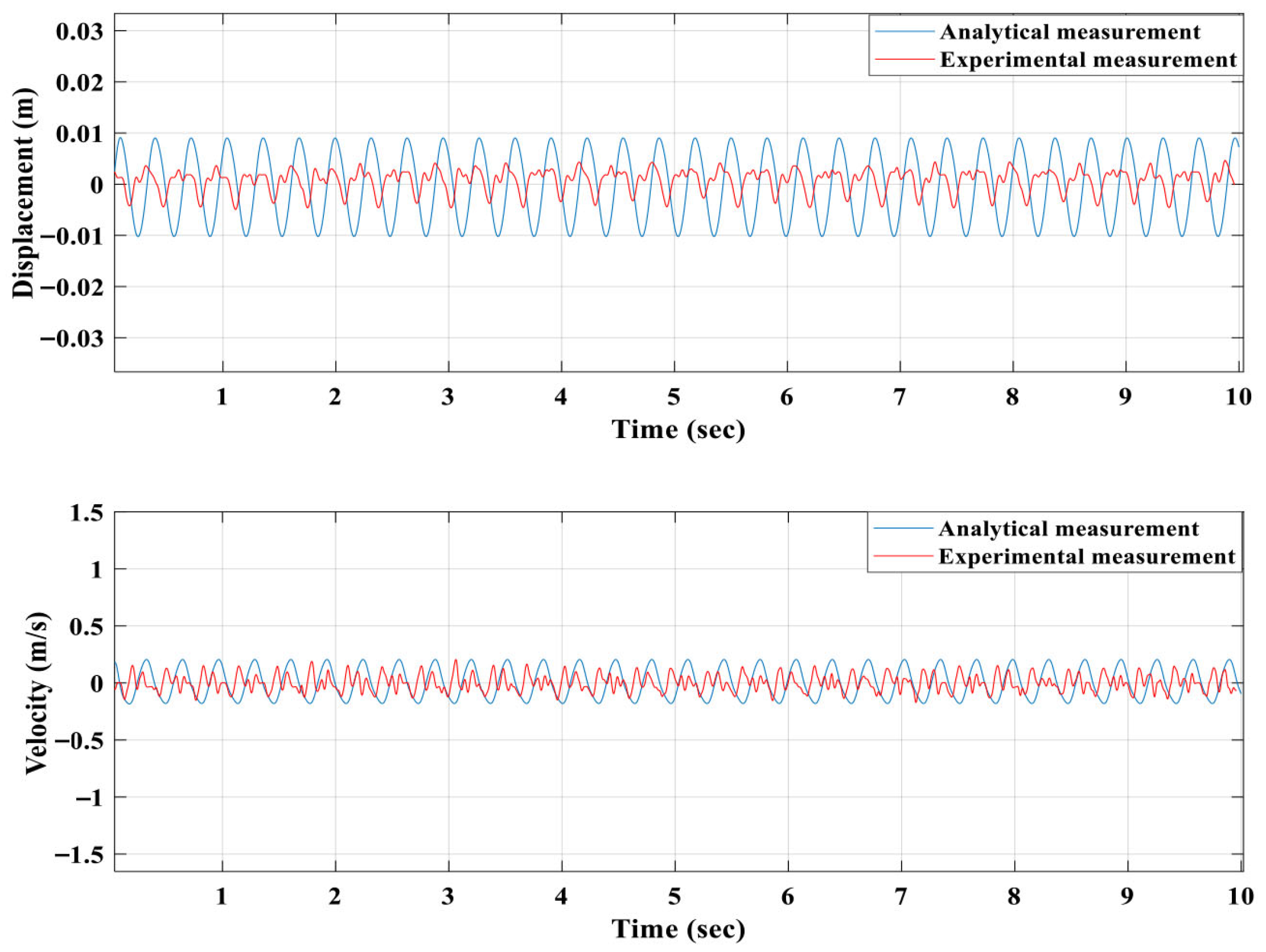

Figure 9 presents the displacements and velocities of the first, second and third floating magnets.

The practical constraints of the test rig defined the experimental excitation conditions. Accordingly, the experiment was carried out first, and the same input parameters were used in the analytical model to maintain consistency. The estimated amplitude of the applied harmonic force was 5N, and the frequency of the applied harmonic force was 3.35 Hz. Although this excitation frequency is higher than the real ocean wave frequencies, it corresponds to a dynamically scaled analogue in which the mass–stiffness–damping ratios remain similar. This ensured that the laboratory tests effectively excited the dominant natural frequencies of the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO while preserving comparability with simulation results.

From

Figure 10, although the fishing line was connected with the first floating magnet, the third floating magnet achieved a maximum displacement and velocity compared to the first and second floating magnets.

Figure 10a shows that all three magnets oscillate around their equilibrium positions, but with different amplitudes. The third magnet (green) exhibits the largest amplitude, indicating stronger dynamic coupling and energy transfer in its stage. The first magnet (red) has the smallest amplitude, as it is most directly constrained by the magnetic restoring force and base excitation. The second magnet (blue) behaves as an intermediate stage, influenced by both the upper and lower magnets. Due to the applied harmonic force, the first floating magnet moved toward the second floating magnet on average 6 mm, but moved toward the bottom by 1 mm. On the other hand, the second floating magnet moved toward the third floating magnet by an average of 4 mm and toward the first by 4 mm. However, the third floating magnet moved toward the top, and the second floating magnet had an average excitation range of 10 mm. The velocity plot (

Figure 10b) mirrors this trend: the third magnet also achieves the highest peak velocity, confirming that it undergoes the greatest motion energy exchange.

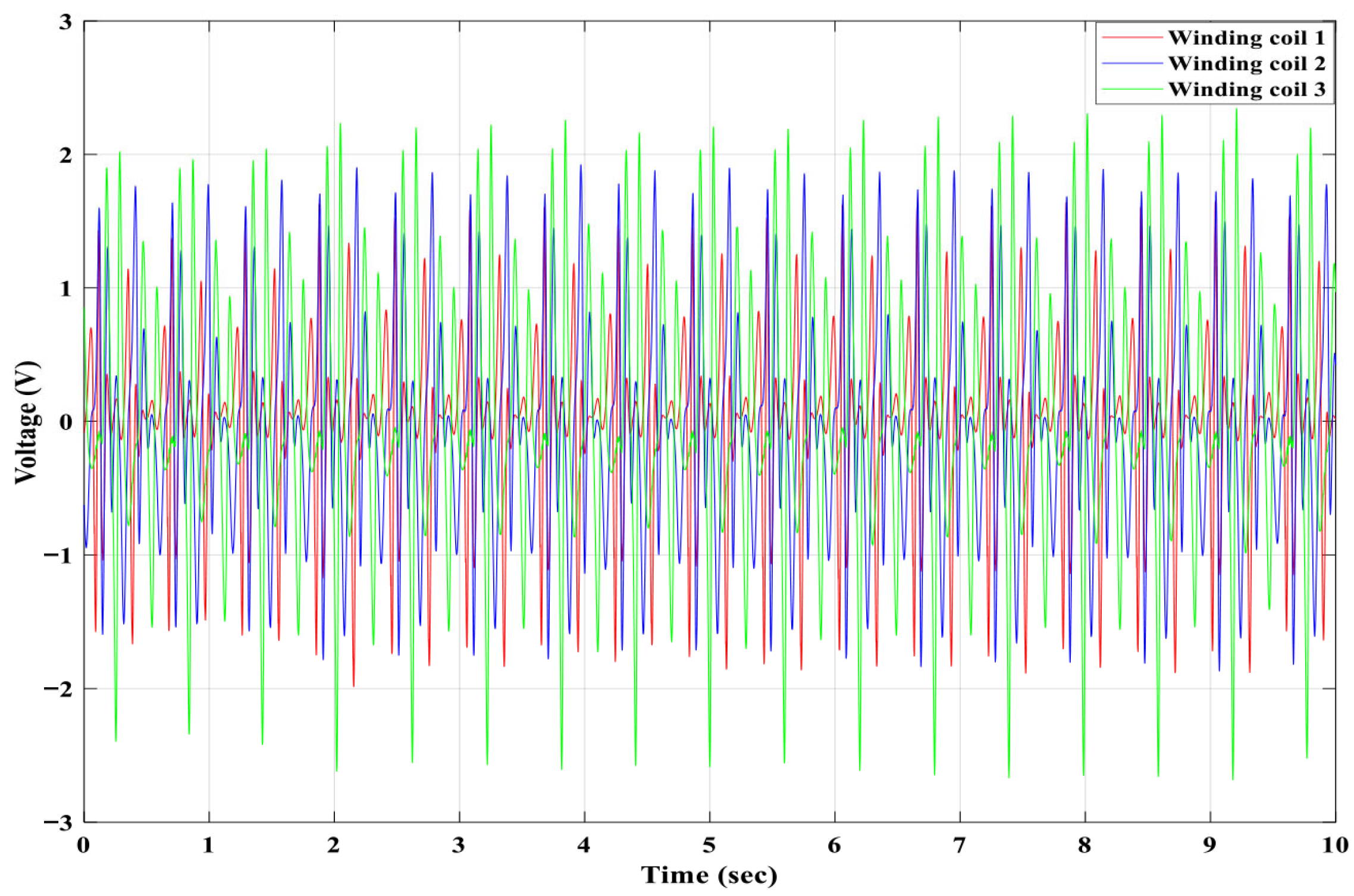

Figure 10 displays the measured induced voltages of winding coils 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 11 presents the time–domain-induced electromotive force (EMF) signals generated by the three winding coils corresponding to the motion of the first, second, and third floating magnets. Each coil exhibits a nearly sinusoidal but phase-shifted voltage pattern resulting from the relative motion between the floating magnets and the coils within the magnetic spring field. The third coil produces the highest peak and RMS voltage, consistent with the larger velocity amplitude of the third floating magnet, as observed in

Figure 10. The second coil generates intermediate EMF levels, while the first coil shows the lowest amplitude, reflecting the progressive energy transfer through the 3DOF magnetic spring structure. Minor phase differences between coils confirm the coupled multi-mode oscillation of the system, where each magnet contributes to a distinct resonance mode. This distributed induction process smooths the overall power output and reduces voltage fluctuation compared with a conventional single-DOF PTO. Quantitatively, the RMS voltage of coil 3 is approximately 30% greater than coil 1, confirming that the enhanced magnetic flux uniformity and higher oscillation velocity of the third stage yield improved energy conversion efficiency. These results validate the effectiveness of the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO’s multi-mode energy harvesting mechanism.

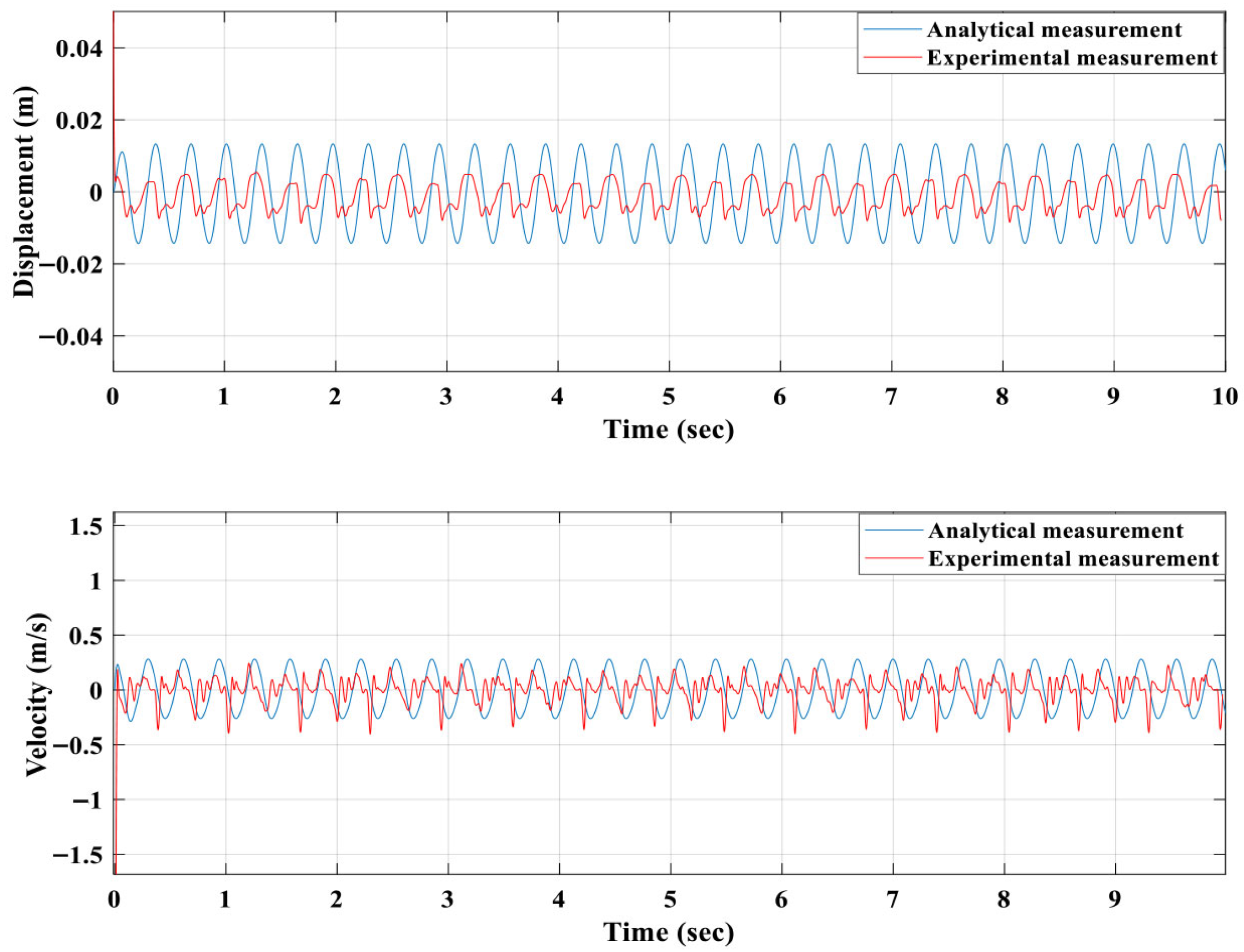

Secondly, the experimental work was performed by connecting the second floating magnet with the servo motor’s pulley using the fishing line (the fishing line went through the plastic bush of the third floating magnet, and the first floating magnet was free). The estimated amplitude of the applied harmonic force was 6.5 N, and the frequency of the applied harmonic force was 3.13 Hz.

Figure 10 displays the displacements and velocities of the first, second and third floating magnets.

Figure 12 illustrates the experimentally measured displacement and velocity responses of the three floating magnets under a 6.5 N, 3.13 Hz harmonic excitation applied to the second magnet via the servo-motor pulley. The first magnet was left free, while the third magnet responded through magnetic coupling. The results show that the third magnet exhibited the highest displacement and velocity amplitudes, followed by the second and then the first magnet. This trend confirms the progressive energy transfer through the coupled magnetic spring structure, with the third magnet experiencing the greatest dynamic amplification due to the cumulative magnetic stiffness effect. Small phase shifts between the three responses indicate multi-mode resonance behaviour rather than purely synchronous motion. Quantitatively, the RMS displacement and velocity of the third magnet are about 30% and 25% higher, respectively, than those of the second magnet. These results validate the analytical 3DOF model predictions and demonstrate that the coupled magnetic spring arrangement effectively enhances oscillation amplitude and energy conversion potential across multiple degrees of freedom.

Figure 13 shows the measured induced voltages of three winding coils. The induced voltages from the three winding coils directly reflect the mechanical behaviour of the floating magnets shown in

Figure 12. Since the induced EMF in each coil is proportional to the rate of change in magnetic flux, and the flux variation depends on the displacement and velocity of the corresponding magnet, the electromagnetic response follows the same trend as the mechanical response. Specifically, the third floating magnet exhibited the largest displacement and velocity amplitudes, followed by the second, then the first. Consequently, the induced voltage in coil 3 is expected to be the highest, with coil 2 producing intermediate voltage and coil 1 the lowest. This correlation between the magnet dynamics and electrical output confirms that the multi-mode oscillation of the 3DOF magnetic-spring PTO effectively converts the distributed mechanical energy of the system into electrical energy across multiple coils.

Figure 14 illustrates the experimentally measured displacement (

Figure 14a) and velocity (

Figure 14b) responses of the three floating magnets when the third floating magnet was directly excited using a fishing line connected to the servo-motor pulley. The first and second floating magnets were left free so that their motion was driven purely by magnetic coupling. The applied harmonic excitation had an estimated amplitude of 7 N and frequency of 3.98 Hz.

From

Figure 14, it can be observed that the third floating magnet (green curve) exhibited the highest displacement and velocity amplitudes, followed by the second and then the first magnet. This behaviour confirms that when the excitation is applied at the bottom stage, the energy transfer through the magnetic spring interactions accumulates toward the third magnet, resulting in the strongest dynamic response. The first magnet, located furthest from the point of excitation, demonstrated the smallest motion amplitude due to successive energy dissipation through the coupled system. Small phase differences among the curves further confirm the presence of multi-mode vibration rather than synchronous motion.

The corresponding induced voltage waveforms are shown in

Figure 15. Consistent with the displacement and velocity results in

Figure 14, winding coil 3 generated the highest induced voltage, while coils 2 and 1 produced intermediate and lower voltages, respectively. This trend reflects the proportional relationship between induced EMF and the velocity of the floating magnets: the magnet with the highest oscillation velocity produces the greatest rate of change in magnetic flux and therefore the highest voltage.

These results demonstrate that regardless of whether the excitation is applied to the first, second, or third floating magnet (as shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15), the third floating magnet consistently exhibits the greatest motion amplitude and produces the highest induced voltage. This outcome confirms that the design of the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO naturally amplifies energy toward the lower end of the generator column, improving conversion efficiency and validating the multi-mode resonance mechanism of the system.

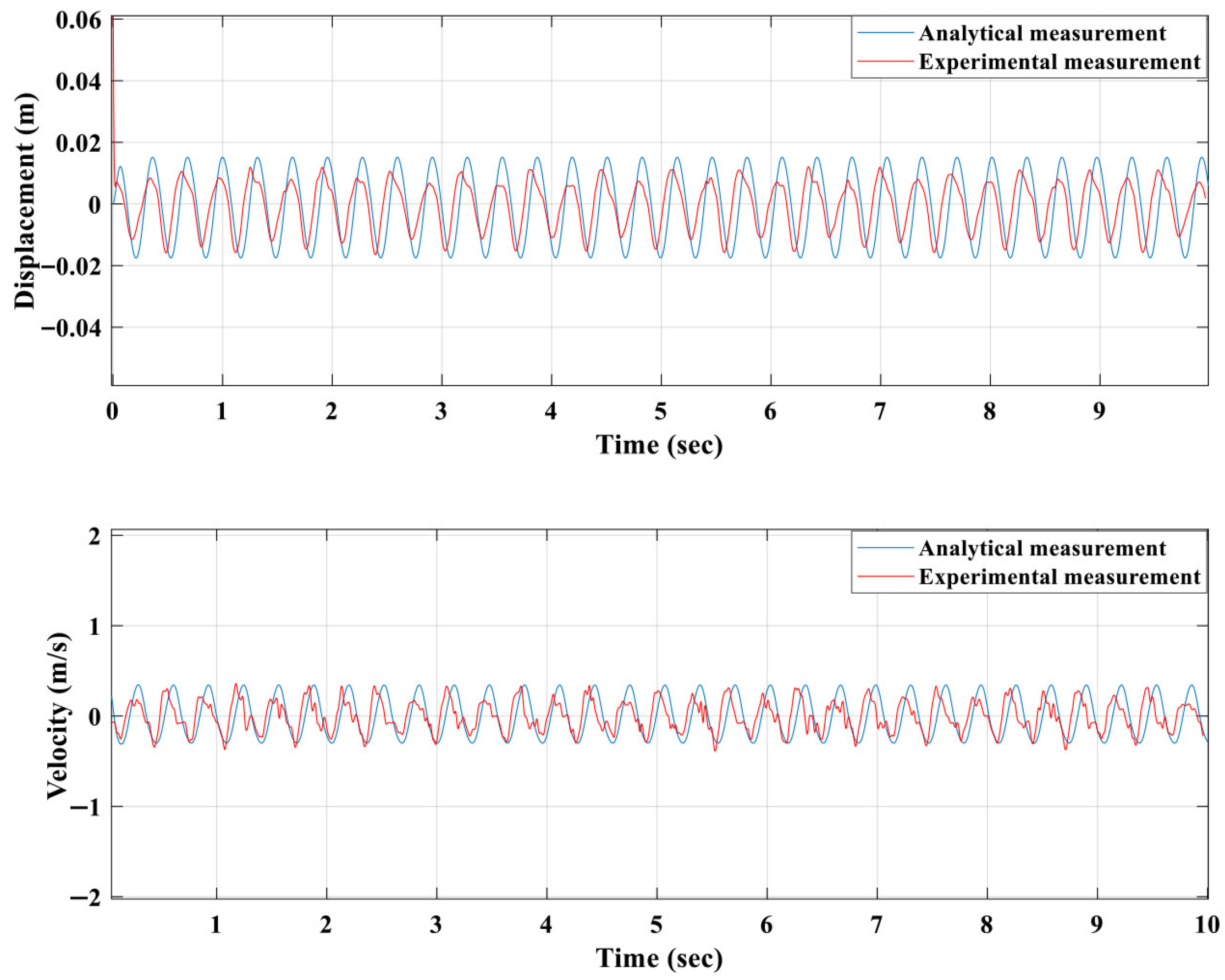

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 compare the analytical and experimental displacement and velocity of the first, second and third floating magnets under identical excitation (6.5 N, 3.136 Hz). Across all three floating magnets, the analytical and experimental curves show the same frequency, phase and motion pattern, confirming the validity of the proposed dynamic model. Small differences in peak amplitudes arise mainly from unmodelled friction and sensor noise in the experiment, whereas the analytical model assumes idealised damping. The third floating magnet exhibits the largest displacement and velocity in both simulation and experiment, demonstrating its dominant contribution to the multi-mode resonance mechanism and justifying its higher induced voltage observed in later figures.

The comparative analysis between the analytical and experimental results in

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18 highlights both the model’s predictive capability and its limitations. For the first floating magnet (

Figure 16), the analytical model overestimates displacement amplitude by approximately 20–25% compared with the experimental data, primarily due to neglected effects such as mechanical friction, imperfect magnetic alignment and damping nonlinearity in the physical prototype. Nevertheless, the phase trend and velocity waveform remain consistent, confirming that the stiffness and damping representation captures the overall dynamic response. In contrast, the second magnet (

Figure 17) shows improved correlation, though minor amplitude discrepancies persist because of coupling between adjacent magnets and magnetic hysteresis. The third floating magnet (

Figure 18) exhibits the best agreement between analytical and experimental curves, indicating that magnetic coupling uniformity and levitation symmetry are strongest in this configuration.

These results collectively confirm that the analytical state-space model reproduces the essential multi-mode behaviour of the 3DOF PTO but slightly overpredicts response magnitude at low damping. The model will be refined in future work by including experimentally identified damping coefficients and nonlinear magnetic saturation effects.

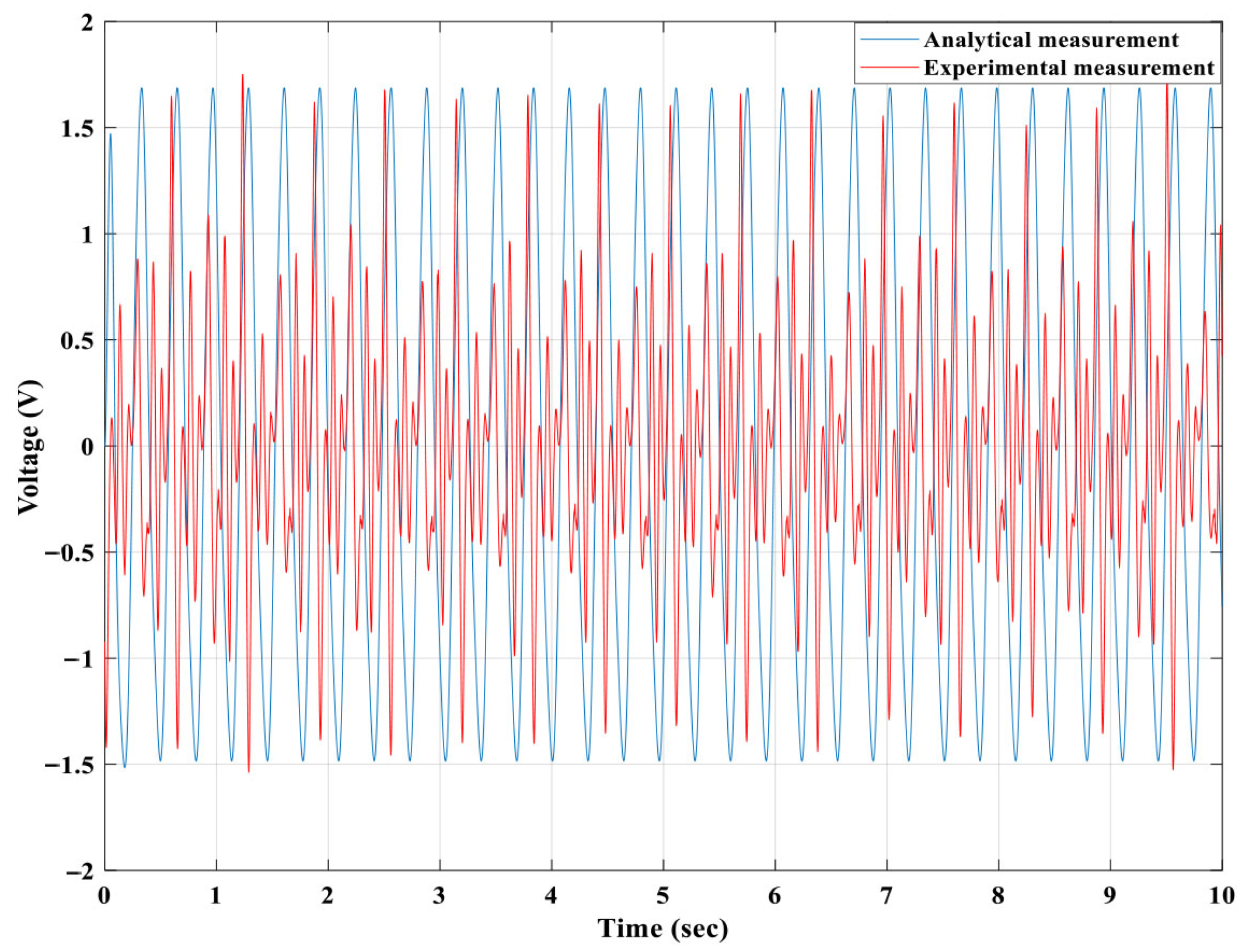

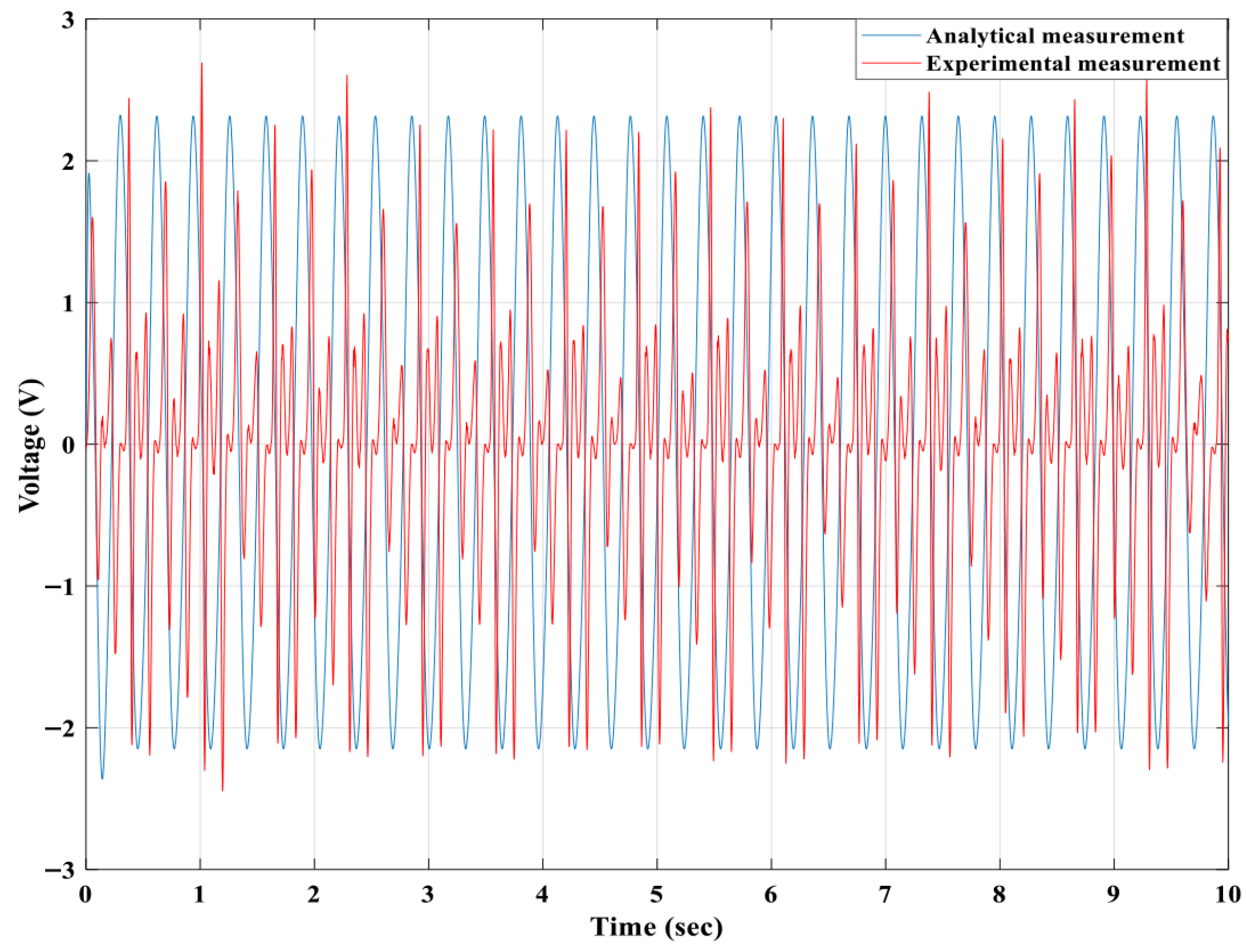

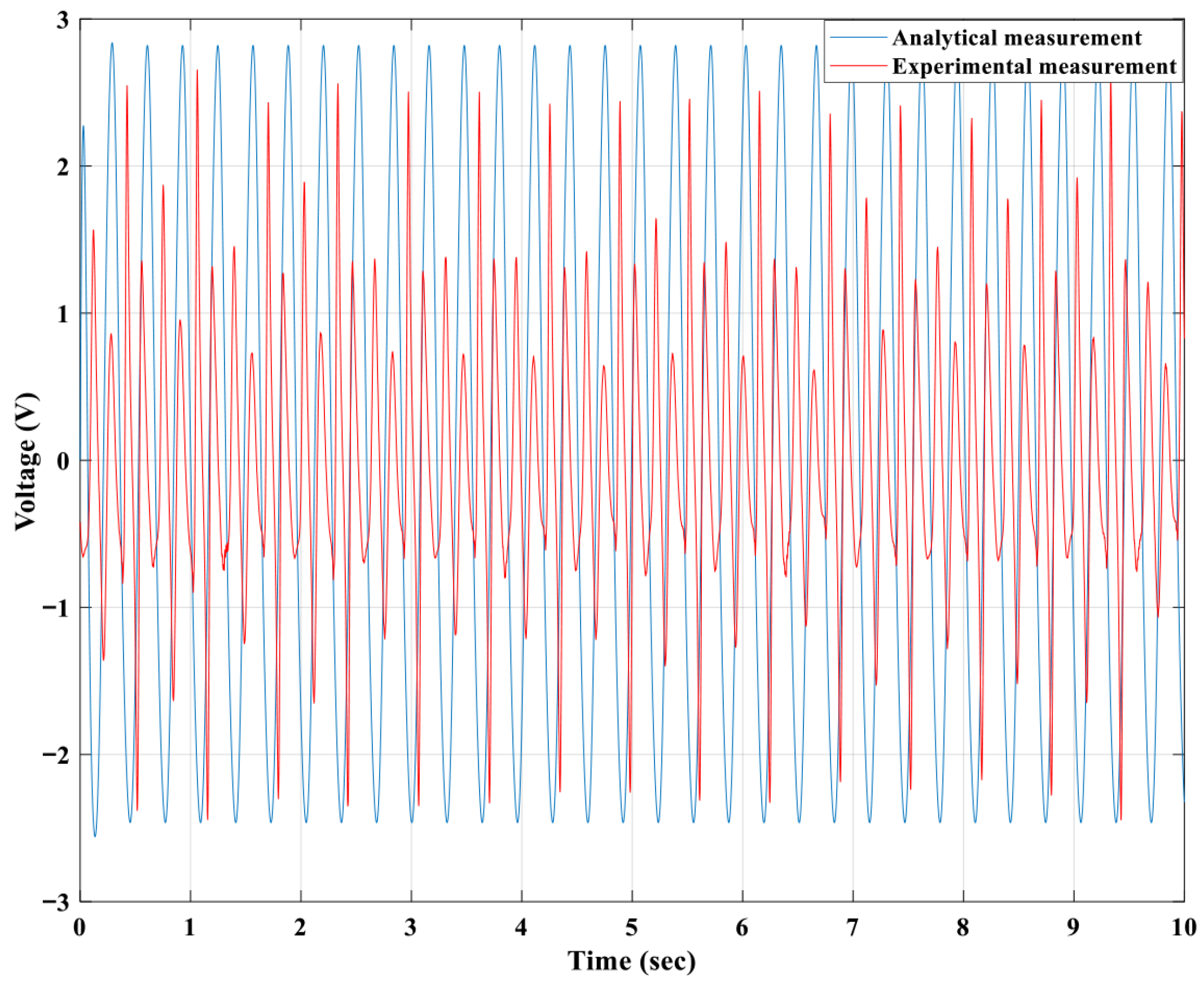

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21 present the generated induced voltages in winding coils 1, 2 and 3, respectively.

The measured induced voltages in winding coils 1, 2 and 3 for the experimental measurement were similar to those obtained analytically, as presented in

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. The winding coil 3 generated a higher induced voltage than the winding coils 2 and 1.

To quantitatively compare the analytical and experimental results, RMSE and mean relative error values were computed for the displacement, velocity and induced voltage of the third floating magnet.

Table 4 summarises the results. The model exhibits a small amplitude overprediction (≈6–13%) yet accurately captures the waveform shape and phase behaviour. The discrepancies are predominantly due to the simplified electromagnetic damping formulation, which assumes linear damping with constant coil resistance and neglects nonlinear effects such as eddy-current losses, magnetic hysteresis and mechanical friction-induced damping. Despite these simplifications, the analytical model effectively reproduces the dynamic characteristics of the 3DOF PTO.

The added error quantification in

Table 4 confirms that the analytical model captures the dynamic behaviour of the 3-DOF magnetic spring PTO with high fidelity. Displacement and velocity errors remain below 10%, while the voltage error, which is most pronounced at the third coil, is primarily due to nonlinear electromagnetic damping and velocity-dependent flux linkage, both of which are simplified in the model. Overall, the low error values validate the suitability of the model for performance prediction and control design.

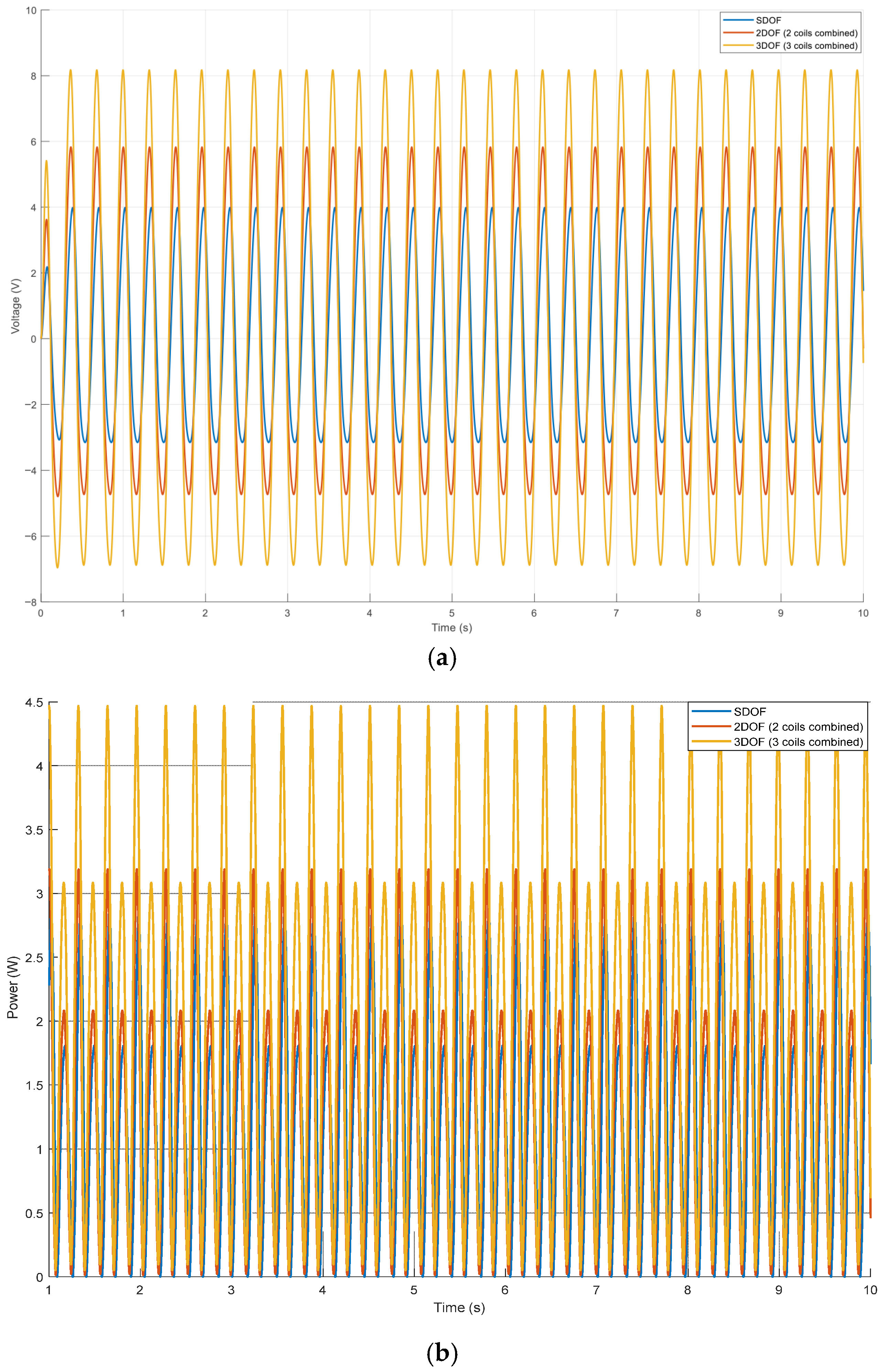

To quantify the benefit of the proposed 3DOF magnetic spring PTO relative to traditional designs, an equivalent SDOF baseline was constructed by constraining the upper two magnets in the validated 3DOF model. The total moving mass, effective linear stiffness and electromagnetic parameters (coil resistance, length and flux density) were preserved, and the same harmonic excitation (6.5 N amplitude and 3.13 Hz excitation) and load resistance were applied. Using this common framework, the RMS output voltage and average electrical power were computed for the SDOF, 2DOF and 3DOF configurations.

Figure 22 shows the comparison of induced voltage generated by SDOF, 2DOF and 3DOF magnetic-spring PTO systems under identical excitation (6.5 N amplitude, 3.13 Hz excitation).

Figure 22 compares the induced voltage generated by the SDOF, 2DOF and 3DOF magnetic spring PTO configurations under the same excitation conditions (6.5 N amplitude, 3.13 Hz excitation). As shown, all three configurations exhibit periodic voltage responses; however, their amplitudes and waveform characteristics differ noticeably as the degrees of freedom and magnetic coupling increase. The SDOF system produces the lowest voltage amplitude because only a single magnet contributes to the coil’s flux variation. The 2DOF configuration shows a higher voltage response, owing to two levitating magnets oscillating in coupled motion, which increases the rate of magnetic flux change. The 3DOF system exhibits the highest voltage amplitude and the most pronounced peaks due to the combined effects of three resonant modes, stronger inter-magnet coupling and greater electromechanical energy transfer. Thus, the 3DOF configuration not only increases peak voltage but also delivers substantially more usable electrical energy over time, which is reflected in its higher RMS output.

Table 5 compares the proposed 3DOF magnetic spring PTO with existing SDOF and 2DOF systems reported in the literature. SDOF devices operate with only one resonance and therefore exhibit narrow-band energy extraction and high mechanical wear. 2DOF systems improve performance through coupled oscillators, enabling two resonant modes and a wider operating bandwidth, but their voltage output remains limited, and their tuning capability is still restricted. Existing 3DOF architectures further expand bandwidth by using three coupled oscillators; however, they rely solely on repulsive levitation and do not provide stiffness tuning or friction-free operation. In contrast, the present 3DOF magnetic spring PTO combines levitation with an axial magnetic spring mechanism, producing three closely spaced resonances over a broad frequency range and significantly higher voltage output under the same excitation. This confirms that the proposed design offers a measurable breakthrough in broadband, high-efficiency PTO performance compared with prior systems.

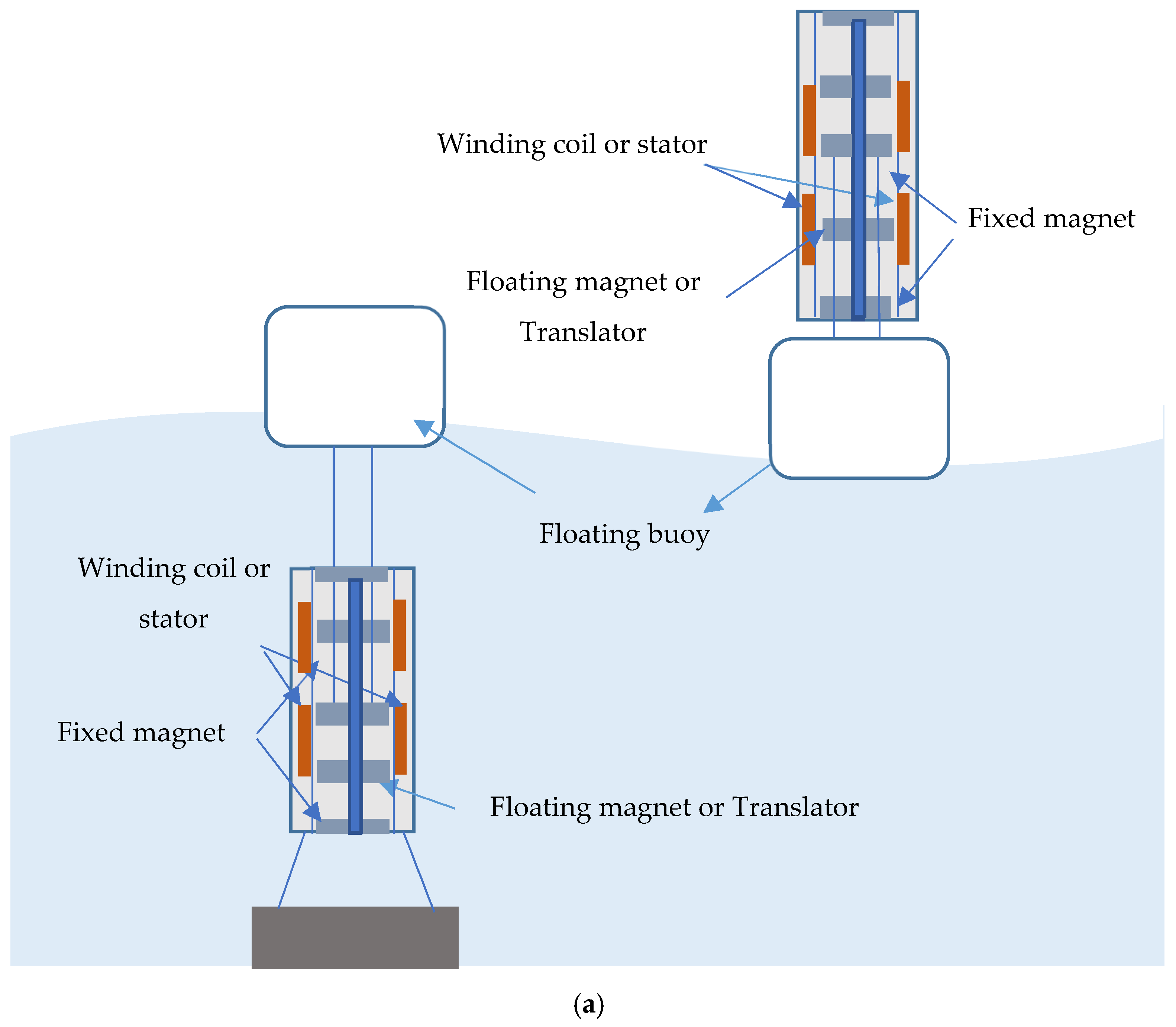

5. Application of the 3DOF Oscillator-Based PTO System in the Ocean Energy Field to Harness Ocean Wave Energy

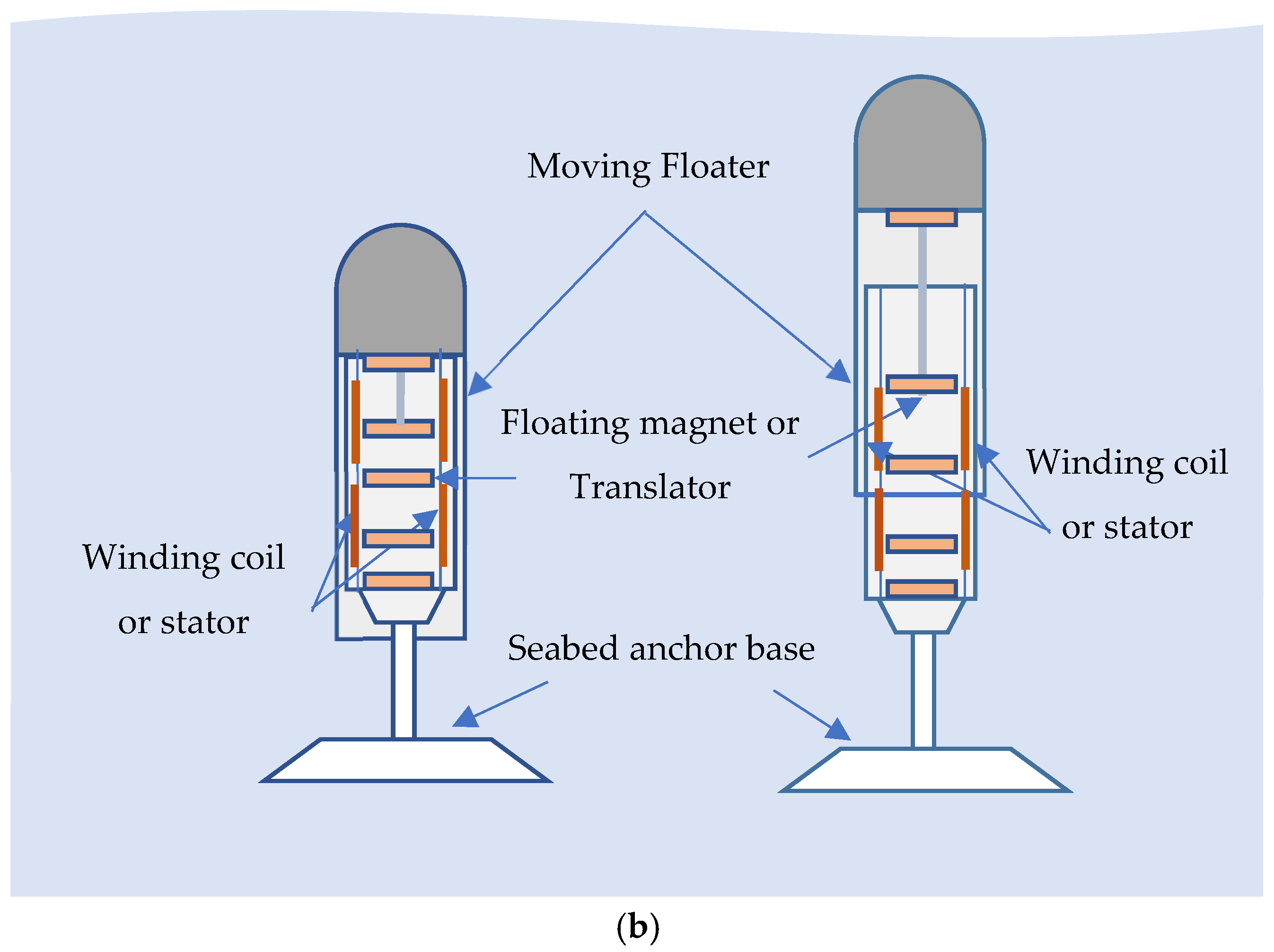

This section discusses how the PTO could be integrated into practical ocean wave energy converters (WECs). Point-absorber WECs consist of a buoy on the water’s surface attached to a mooring or reaction body. As waves pass, the buoy heaves up and down (and in some designs surges back and forth). A PTO located between the buoy and the mooring converts this relative motion into electricity.

Figure 23 and

Figure 24 present conceptual layouts demonstrating how the proposed 3DOF magnetic spring PTO could be integrated into surface-floating and submerged wave energy converters. These diagrams illustrate the energy conversion architecture and are not drawn to scale with the laboratory prototype shown in

Figure 9. In the context of the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO, the buoy can be designed to house a compact generator column containing the three levitated magnets and their coils (

Figure 23a). The vertical motion of the buoy relative to the mooring imparts oscillations to the floating magnets; the resulting relative movement between each magnet and its coil induces voltages in three frequency bands. Because the 3DOF PTO exhibits distinct resonance modes, it can absorb energy across a wide range of wave periods without active tuning, making it well-suited for irregular sea states. Moreover, the magnetic levitation mechanism reduces friction and eliminates mechanical wear, improving reliability for long-term deployment in corrosive marine environments.

To maximise energy capture, the buoy geometry and mooring system should be tuned such that one or more of the PTO’s natural frequencies align with the dominant wave frequencies at the deployment site. Hydrodynamic modelling of the buoy’s response amplitude operator (RAO) can identify optimal dimensions and ballast. Unlike traditional PTOs that employ hydraulic cylinders or linear generators with a single spring constant, the magnetic spring PTO allows in situ adjustment of the restoring force by modifying the magnet spacing or polarity. This capability enables fine-tuning of the system after deployment to adapt to seasonal changes in wave spectra or to detune the system during extreme storm events for survivability.

Another promising configuration is a fully submerged heaving WEC where a submerged float moves relative to a rigid frame anchored to the seabed (

Figure 23b). In such systems, the PTO is protected from direct wave impact and can operate in a more stable environment. The 3DOF PTO can be mounted vertically inside the frame, with the suspended magnets connected via a tether to the submerged float. Vertical heave motion of the float excites the magnets, while the stationary frame supports the coils. This arrangement isolates the generator from biofouling and wave slamming, and the magnetic levitation reduces maintenance requirements. Because the PTO is decoupled from atmospheric pressure variations, it can also be integrated into oscillating water column devices as an alternative to linear generators. When the air column drives a piston or float, the 3DOF PTO converts the motion into electricity through multiple resonant modes.

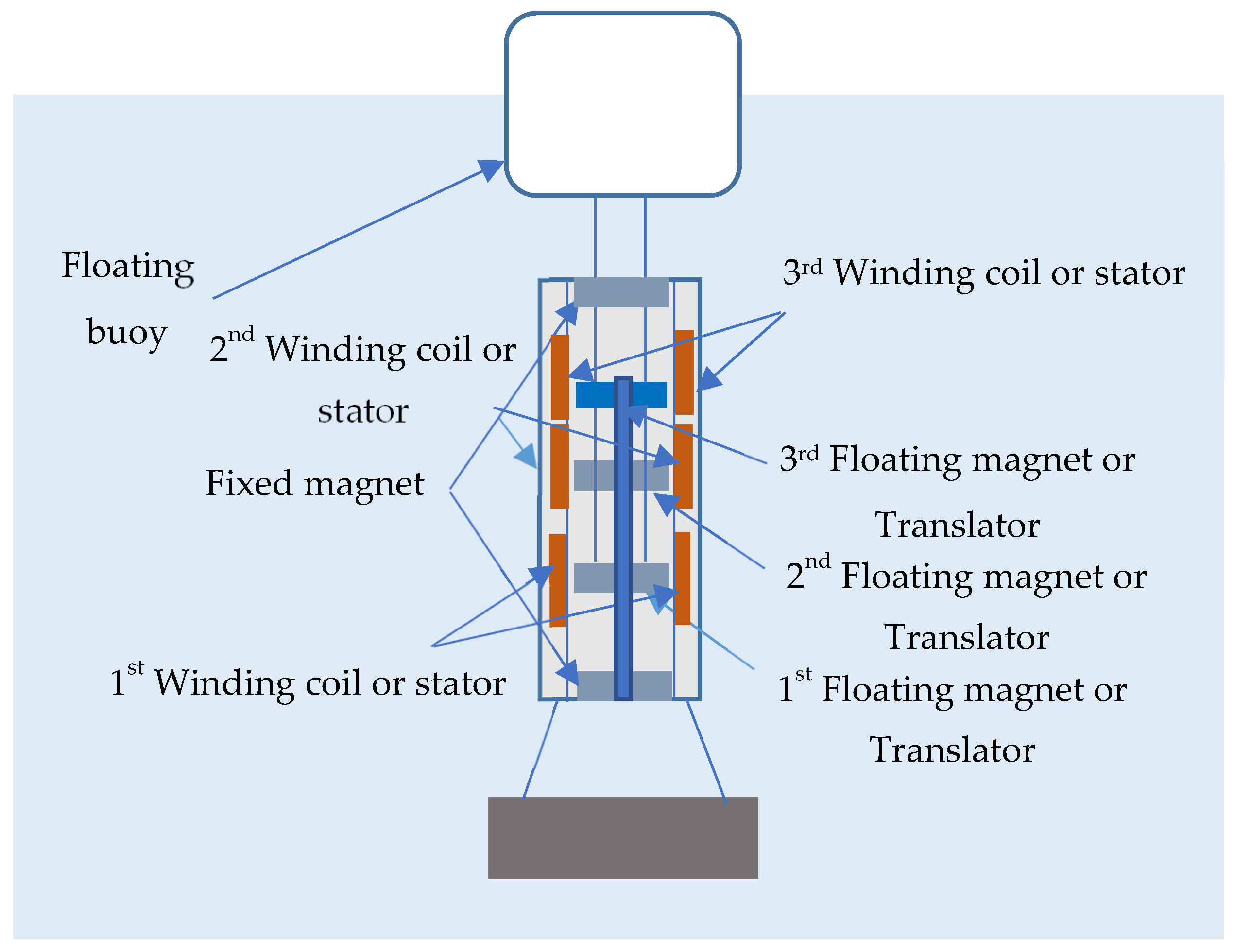

Figure 24 presents the floating buoy-based WEC where the floating buoy is connected with the 3DOF PTO system.

5.1. Multi-Mode Energy Capture and Control Strategies

The key benefit of a multi-degree-of-freedom PTO is its ability to extract energy over a broad frequency range. However, to realise this benefit at sea, appropriate control strategies are required. Passive control involves tuning the natural frequencies of the magnets and the buoy’s mass–spring–damper parameters so that at least one resonant mode matches the dominant wave frequency. Active control strategies could use algorithms similar to those used in state-of-the-art WECs, such as phase control or latching, to temporarily hold the oscillating magnets or buoy in place and release them at optimal phases to maximise power output. Because the 3DOF PTO produces multiple voltages at different frequencies, power electronics may need to combine or rectify these outputs. The multiple coils can be connected in series or parallel depending on the load requirements, or each coil can feed a separate rectifier to harvest energy from its respective mode.

5.2. Potential Applications and Scalability

The modular design of the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO lends itself to a variety of wave energy applications. Individual units can be integrated into small buoys to power autonomous sensors, navigation lights, or communication devices in offshore installations. Arrays of larger buoys equipped with these PTOs could deliver utility-scale electricity when connected through subsea cables to an onshore grid or an offshore platform. The broadband response makes the technology attractive for regions with highly variable wave climates, where conventional narrowband WECs underperform. Furthermore, because magnetic springs provide tuneable restoring forces without mechanical contact, the same PTO technology could be adapted for hybrid energy harvesters that combine electromagnetic, piezoelectric, or triboelectric mechanisms, extending its use beyond ocean waves to include ship motion harvesting or vibration energy in offshore structures.

5.3. Challenges and Future Work

While the 3DOF PTO shows significant potential, several challenges must be addressed for ocean deployment. Hydrodynamic–mechanical coupling between the buoy and the PTO needs to be characterised to avoid unwanted interactions (e.g., slamming forces or parametric excitation). The magnetic springs must be protected from corrosion and biofouling, and the levitation gaps must remain free of debris. Appropriate marine-grade materials and coatings will therefore be essential. Additionally, deployment strategies and mooring designs must account for extreme storm loads; detuning or locking mechanisms may be necessary to protect the PTO during severe sea states. Future work should include coupled simulations of buoy dynamics with the 3DOF PTO, tank tests of integrated prototypes and ultimately open-sea trials. These studies will help quantify the energy yield and economic viability of multi-degree-of-freedom PTOs, refining their design for commercial wave energy applications.

6. Applications of Sustainability Concepts to the 3DOF Magnetic Spring PTO

Applying these sustainability concepts to the 3DOF magnetic-spring PTO system involves the following steps.

6.1. Defining Sustainability Objectives

Wave energy systems must be designed for long-term performance across the triple bottom line. Life cycle assessment (LCA) studies show that the most significant environmental burdens of conventional point absorbers come from steel fabrication and sea vessel operations; carbon footprints range from ~35 g CO

2-eq/kWh for the Pelamis P1 device to ~57–79 g CO

2-eq/kWh for Oyster devices [

14]. Therefore, a magnetically levitated PTO, which eliminates mechanical wear and uses less steel, should target greenhouse gas emissions well below these benchmarks. Sustainable objectives include the following:

Environmental: Minimise greenhouse gas emissions, material use and impacts on marine ecosystems. Material choice and design must be optimised because LCAs indicate that proper material selection and improved energy harvesting designs can reduce impacts [

14].

Economic: Ensure cost competitiveness by reducing operating and maintenance costs relative to diesel generation and hydraulic PTOs, recognising that wave energy is an emerging technology that still seeks a commercial balance between cost and efficiency [

15].

Social: Maximise local employment, energy security and equity. Studies emphasise that wave energy projects must engage with coastal communities early; without community-centric design, projects face “terminal pushback” [

15].

6.2. Quantifying Impacts via Life Cycle Assessment

LCAs provide cradle-to-grave estimates for wave energy converters. For example, Pelamis P1 and Oyster devices show carbon payback periods of 18–24 months [

14], while smaller buoy–rope–drum devices have higher carbon intensities (~89 g CO

2/kWh) but shorter payback periods [

14]. These studies highlight areas of concern, such as steel production and vessel operations. A 3DOF magnetic spring PTO could improve sustainability by:

Reducing friction and wear: The magnetic levitation eliminates mechanical contact, extending service life and lowering maintenance demands compared to hydraulic PTOs.

Material efficiency: Although the design relies on high-performance permanent magnets, which carry supply chain risks, modular architecture can minimise the quantity of magnets per unit of power.

Supply chain considerations: Rare-earth magnets (NdFeB) are classified as critical minerals; their supply has been disrupted by pandemic recovery, geopolitical conflicts and shipping delays [

16]. International efforts seek to diversify mining, reopen mines with strict environmental standards and promote recycling [

16]. For sustainability, developers should explore alternative magnetic materials, incorporate designs that facilitate magnet recovery and participate in recycling programmes.

Electromagnetic fields: Magnetically levitated systems create multiple magnetic fields. A 2024/2025 OES-Environmental summary notes that natural electric and magnetic fields provide important cues to electro-receptive species like salmon, crabs and rays; additional EMFs from subsea cables can mask these cues [

17]. However, evidence indicates that EMFs from small-scale marine renewable energy projects are unlikely to harm sensitive species [

17]. Monitoring should nonetheless track the behaviour of electromagnetically sensitive marine species, and burying or shielding cables can further reduce exposure.

6.3. Environmental Impact and Life Cycle Perspective

A preliminary life cycle assessment (LCA) was carried out to evaluate the environmental implications of the proposed three-degree-of-freedom (3DOF) magnetic spring power-take-off (PTO) system in comparison with conventional hydraulic PTOs. The goal of this assessment is to estimate the cradle-to-gate carbon intensity per unit of electricity produced. The functional unit is defined as 1 kWh of electricity delivered by the PTO. The system boundary includes raw material extraction, manufacturing and assembly of one laboratory-scale prototype; installation, operation and end-of-life stages are discussed qualitatively.

Inventory and Data Sources: Material composition was derived from the prototype’s CAD model and measured masses: stainless steel frame and shaft ≈6.5 kg, NdFeB permanent magnets ≈1.6 kg, copper coils ≈1.05 kg, polymer bushings ≈0.4 kg and sensors and wiring ≈0.5 kg, giving a total assembled mass of approximately 10 kg. Embodied energy and emission factors were obtained from the Ecoinvent v3.9 database, assuming the Australian electricity mix (0.67 kg CO2 kWh−1). Fabrication energy for small-scale electromechanical devices was modelled using standard machining and winding coefficients.

Impact Assessment: The cradle-to-gate carbon footprint of the laboratory prototype is estimated at ≈89 kg CO

2-eq per unit, dominated by stainless steel fabrication (≈44%) and NdFeB magnet production (≈45%). Scaling to a corrosion-protected, marinised full-scale device, including thicker structural members, sealed housings and anchoring hardware, would raise embodied emissions to ≈10–15 t CO

2-eq per unit. Assuming a rated power output of 350 W, 40% capacity factor and 25-year service life (~30 MWh lifetime generation), the resulting cradle-to-gate carbon intensity is ≈40–80 g CO

2-eq kWh

−1, and the energy payback time (EPBT) is ≈3.2 years. These values compare favourably with the reported 57–79 g CO

2-eq kWh

−1 for hydraulic PTOs and ≈35 g CO

2-eq kWh

−1 for the Pelamis P1 device, as shown in

Table 6 [

14].

Interpretation and Future Work: The analysis demonstrates that the elimination of sliding components and reduced steel mass substantially lowers embodied emissions while maintaining competitive energy payback performance. Nevertheless, rare-earth magnet production remains a critical sustainability challenge due to its energy intensity and supply-chain vulnerability [

16]. Incorporating recyclable magnet assemblies, alternative magnetic alloys and modular disassembly could reduce life cycle impacts by a further 10–20%. Future work will include a full ISO 14040/44-compliant cradle-to-grave LCA, integrating transport, mooring, operation and decommissioning stages [

18,

19]. A Monte Carlo uncertainty analysis will be applied once the marinised prototype is deployed, allowing quantification of variability in embodied energy, emissions and material recovery potential. These developments will strengthen the environmental credibility of the 3DOF PTO for large-scale ocean energy applications.

6.4. Evaluating Socio-Economic Benefits and Trade-Offs

Wave energy resources are vast—assessments suggest up to 2.64 trillion kWh of potential in U.S. waters [

15]—but realising this potential requires balancing technology, economy and society. Community-centric projects in the U.S. (e.g., Beaver Island and Nags Head) illustrate that stakeholder engagement is essential; local priorities (backup power, desalination, economic development) vary and must inform design [

15]. For the 3DOF PTO, the socio-economic evaluation should include:

Benefit–cost analysis: Quantify job creation, avoided diesel use, reduced greenhouse gas emissions and resilience benefits (e.g., backup power during storms). Wave energy devices can offer aesthetic advantages over offshore wind turbines because they are situated near the water surface.

Stakeholder engagement: Early, transparent engagement with coastal communities, Indigenous groups and fisheries to ensure equitable benefit sharing and site selection. Research emphasises that community-centric design is vital; without it, projects may face strong opposition.

Design optimisation: Adopt modular construction and standardised components to facilitate selective replacement and upgrade. Modular design reduces downtime and enables adaptation of PTO stiffness and damping to varying sea states, improving energy capture and economic return.

6.5. Monitoring and Reporting

Operational sustainability requires real-time monitoring of environmental and performance indicators. Carbon footprint calculators and energy efficiency benchmarking tools should track emissions relative to the kWh delivered. Sustainability dashboards can integrate data on power output, maintenance events, emissions, socio-economic metrics and progress toward UN Sustainable Development Goals. For environmental monitoring, guidelines recommend baseline surveys and ongoing measurements of noise, EMFs and benthic impacts; EMF guidance from OES-Environmental notes that small-scale MRE EMFs pose low risk (thetys.pnnl.gov), but monitoring ensures early detection of unexpected effects.

6.6. Adhering to Policy and Governance Frameworks

Successful deployment requires alignment with environmental regulations and marine spatial planning frameworks. Developers should collaborate with regulators to integrate sustainability assessments into the permitting process and ensure transparent monitoring results. International collaborations, such as those between the U.S., Australia, the EU and Japan, aim to strengthen critical mineral supply chains [

16]. Projects should utilise adaptive management, where operational parameters (e.g., magnetic spring stiffness and control algorithms) can be adjusted in real-time based on environmental monitoring and performance feedback. Compliance with evolving standards for material recycling, safe EMF levels and marine habitat protection will help the 3DOF magnetic spring PTO transition from a laboratory prototype to a responsible ocean energy solution.